Abstract

Coastal flooding can result from multiple interacting drivers and can be a complex, challenging topic for learners to grasp. Interactive learning with apps offers new opportunities for improving comprehension and engagement. We present the Floodport app, an educational interactive tool that puts students in the role of coastal risk analysts exploring how natural hazards threaten port safety. Users have to adjust key parameters, including high tides, storm surges, terrestrial rainfall contribution, sea-level rise, and engineered features such as dock height. These forces, individually or jointly, result in water-level rises that may flood the app’s port. The app supports exploration of mitigation designs for the port. Developed in Excel and Python 3.11.4 and deployed as an R/Shiny application, Floodport was used as a classroom game by 153 students with no prior knowledge on coastal flooding concepts. Pre–post survey statistical analysis showed significant learning gains and positively correlation with willingness to engage further. Floodport was found to be a useful tool for basic introduction to flooding concepts. The results indicate strong pedagogical promise and potential for using the app beyond the classroom, in contexts such as stakeholder engagement and training.

1. Introduction

Coastal flooding arises from multiple interacting drivers, such as high tides, storm surges, heavy rainfall and runoff, and long-term sea-level rise, threatening ecosystems and economies [1,2]. Altogether, these determine whether and how coastal and port areas become inundated. Each driver operates on different temporal and spatial scales: tides follow regular cycles, storm surges occur during extreme weather events, rainfall can rapidly add water within the port basin, and sea-level rise shifts the long-term baseline [3,4].

For learners, this multiplicity of causes makes the subject difficult: it is cognitively challenging to hold these different mechanisms in mind simultaneously, to recognize how background conditions (for example, an existing engineering structure) change the consequences of a short-term event, and to judge how engineered interventions can alter exposure [5]. Students often conceptualize hazards in isolation, thinking about a single cause at a time, so understanding scenarios involving multiple factors together and their implications for infrastructure requires pedagogical approaches that support integrated mental models [6,7].

This challenge is increasingly important because ongoing climatic changes affect several of the drivers that govern coastal flood risk [8,9]. Observed and projected increases in mean sea level raise the baseline against which all other water-level fluctuations occur [10]; shifts in precipitation extremes alter the potential for intense runoff into port areas [11,12,13], while regional changes in storm behaviour can alter the frequency and intensity of surge events [9]. As a result, ports designed to perform under historical conditions face growing uncertainty and, without adaptation, a greater risk of overtopping and damage [14,15]. Teaching students how to think about these coupled hazards is therefore not only academically useful, but also relevant to real-world planning and risk management [14,16].

Interactive technologies, simulations, visual tools and game-like applications offer a practical pedagogical response to this teaching challenge. Such tools make system behaviour visible, allow learners to experiment with parameter values, and provide immediate feedback: when a student adjusts a parameter or a game scenario, the consequent change in the result is presented instantly [17]. This cycle of manipulation and observation supports active learning by helping students test hypotheses, explore “what-if” paths, and build intuition about how multiple drivers combine to produce flood outcomes [18,19].

Previous research on the topic underlines that the successful role of such approaches lies in their unconventional and entertaining nature engages learners in flood-related issues [18,20]. The review by Flood et al. [17] finds that such interactive approaches have a big potential to influence behaviour and catalyze learning by adaptation. They explain that an interactive learning process generates high levels of inter- and intra- level trust between instructors (or researchers) and learners (or stakeholders), in agreement with other studies [21,22]. Educational research suggests that hands-on, inquiry-based experiences increase engagement, motivation, and conceptual understanding and interactive apps are particularly well suited to bridging disciplinary boundaries between physical drivers and engineering responses [6,23]. While there are several game applications for floods focusing on terrestrial events [24,25], there are fewer applications for coastal flooding. These mostly refer to stakeholder participation processes rather than teaching, while there are also a few recent examples of serious games [26,27,28]. For instance, Becu et al. [29] applied such a game for social learning after a flood event on the Oléron Island, France. The only app that follows an interactive game approach to coastal flooding and is mostly designed for teaching, to our knowledge, is “Inundation” [30]; however, it only includes sea-level rise as a driver of flooding. Moreover, to our knowledge, there is so far no quantitative evaluation of the contribution of such apps in the learning/comprehension process. Thus, we aim to fill these gaps by setting a dual objective:

First, to support integrated learning and comprehension in coastal flooding under multiple drivers. Therefore, we developed Floodport, an interactive educational application that places students in the role of coastal risk analysts for a simplified port system. Floodport models key drivers (high tides, storm surges, rainfall contribution, gradual sea-level rise) and engineered parameters such as dock height and renders the resulting water levels and inundation in an easy-to-explore interface. Implemented with the core computation in Excel and Python and deployed as a free R/Shiny web application, Floodport is explicitly a preliminary pedagogical representation of a complex problem: it is simplified to facilitate rapid exploration, basic sensitivity testing, and classroom discussion, setting a basis for continuous engagement.

Second, our objective is also to determine whether (and how much) an interactive, scenario-based approach can provide students with a preliminary, yet substantive, understanding of how multiple flood drivers interact and how simple engineering choices affect port resilience. So, we quantified the learning gains of Floodport through a student questionnaire survey.

The remainder of the paper describes the Floodport model and user interface, the classroom deployment and survey, and the statistical analysis of the learning outcomes and discusses the pedagogical implications, limitations, and future developments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Floodport Model/App

The Floodport app, as an educational resource, aims to capture the main drivers that can cause a port to flood. The most common ones are tides (natural tidal cycles that elevate water levels), storm surges (sudden sea-level rises during extreme storms), heavy rainfall (added flooding from heavy rainfall directly running off into the port), and sea-level rise (gradual changes due to climate change over a long period of time), as well as their combinations [31,32]. So, we considered a “complete” description of this flooding problem for a port, simplified for undergraduate students, allowing all these parameters to be combined at a certain moment in year t, as Equation (1) shows below [33].

where the effective water level n(t) (the coastal flood in m) can be the sum of the following:

- (1)

- An astronomical tide ( in m).

- (2)

- A storm surge (( in m).

- (3)

- A heavy rainfall event (P (in mm), running off locally into the port. This rainfall is translated into the number of metres of water elevation rise through a conversion factor b (m of water/mm of rainfall), playing the role of a runoff coefficient.

- (4)

- Sea-level rise (in m per year). This process is assumed to happen gradually with a pace c (m/year) over the years (t).

The use of this simple, additive model is a way to explicitly include the four mechanisms most directly responsible for port flooding in most practical contexts: tides, storm surges, direct rainfall/runoff into the basin, and long-term sea-level rise. In this context, it is easier to explore combined scenarios. We chose to have the terms summed, so that the model naturally represents combinations (e.g., a surge arriving at high tide with concurrent heavy rainfall plus an elevated baseline from sea-level rise), which is precisely the pedagogical point: students can see multiple different effects directly.

For an initial assessment of whether a given dock elevation will be overtopped and by how much, these four contributions capture the dominant signal most instructors wish students to explore (including the authors). The use of this model, which purposely keeps the mathematics easy, allows students to focus on the natural/real-world interpretation of the problem, so they can quickly grasp the idea of “adding” effects to understand the total water level. This is a common educational practice for novices, as it gives them time to comprehend stage-by-stage a complex process, ideally by measurable outcomes [34,35]. Furthermore, the aim here was also to bridge conceptual and quantitative thinking, with students practicing conceptually accessible unit reasoning and flood thresholds.

2.2. Classroom Application

The app was presented at three different classrooms (two at the Cyprus University of Technology and one at the Athens University of Economics and Business), with a total sample of 153 Greek students. Thus, we targeted a sufficiently large (representative) group that had no or limited previous experience and knowledge of coastal/port flooding. The presentations took place in May 2025 and October 2025.

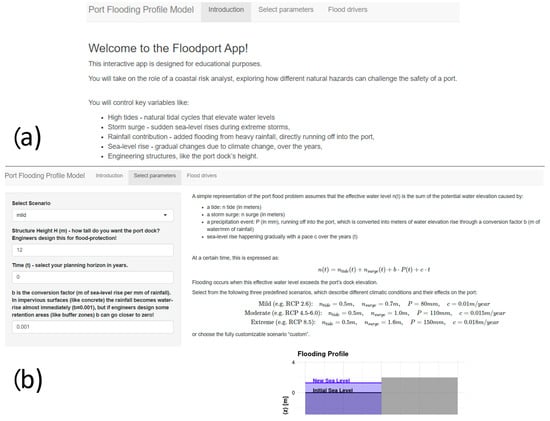

The presentations started with a brief theoretical explanation of the terms (i.e., what each driver is), followed by an explanation of each parameter (more model-thinking), the rationale for their representation within the model, and the communication of any simplifications to students as we proceeded. In particular, the app’s first tab gives the context, explaining the role of the user as a coastal risk analyst and the phenomena they will play with (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) The first tab of the Floodport app (just a part of it, from the beginner-level version), introducing the concepts. (b) the second tab of the Floodport app (just a part of it), allowing the user to select the parameters and showing the results.

Then, in the second tab (Figure 1b), we proceed by explaining the key parameters:

- The astronomical tide ( was presented as a known time-series (observed) or just as a simple phase (e.g., low tide, mean sea level, high tide). This is an acceptable approach, as tides are deterministic on short timescales and are easy to explain. So, this can teach students that the timing of a surge relative to the tide matters [36,37].

- The storm surge () is treated as a single surge height value for the event (students set surge amplitude). We explained that there are advanced models where surges vary in time and space and are predicted with hydrodynamic assessments, but, for the purpose of this demonstration, we are using a single surge height to isolate the storm effect and show how a transient event can tip a system from safe to flooded [38,39].

- The rainfall contribution (b·P) represents direct rainfall over the port location (not necessarily the whole catchment that might run off into an outlet—port). We explain that real runoff depends on catchment area, infiltration, drainage capacity, and storage, but here, the use of a single value (b) to represent these gives students a usable lever without requiring hydrology modelling (which they have not been taught). Also, we explain that a common educational approximation is b ≈ 0.001 m/mm (1 mm rainfall ≈ 1 mm water column for the concrete of the port dock), but b may be much smaller in well drained systems or larger in confined basins [40,41].

- The sea-level rise contribution is treated as a simple linear trend representing accumulated sea-level rise since the baseline year. We explain that in reality this can be more complex, reflecting non-linear climatic processes (mentioning IPCC scenarios and potential uncertainties). For our purpose, a linear rate (c m/yr) is intuitive and sufficient to show how a raising baseline increases susceptibility over decades [42,43].

Regarding the model’s scope and simplifications: We were clear to the students that this is a “beginner-level” intentional conceptual simplification of the problem, to serve pedagogical objectives: to make the main drivers of coastal flooding (tides, storm surges, rainfall-derived runoff, and long-term sea-level rise) immediately accessible to students and non-specialist users. In doing so we omit processes like wind-wave set-up and run-up, overtopping mechanics, detailed bathymetric/topographic variability, infiltration and drainage network behaviour, and some forms of non-linear surge–tide interaction. We were also upfront, explaining that these omissions are not a statement of scientific irrelevance (rather they reflect a deliberate choice to trade physical completeness for clarity and tractability in an introductory learning setting) and that in later modules we will talk about how to estimate these more rigorously, presenting models that replace these single parameters with process-based sub-models (runoff models, surge hydrodynamics, tide harmonics, wave models). For now, the goal is to focus on building intuition about how these broad drivers contribute to flooding.

The model was developed in a MS Excel spreadsheet with three different scenarios of flooding and the interactive app was built as an R (version 4.4.3) ShinyApp [44].

A sensitivity exercise was carried out, following the discussion of the role of the different parameters on the result (this is presented in the third tab of the app).

2.3. Scenario Analysis

After defining the problem of a potential port flood to the users, the Floodport app offers a set of flooding scenarios. These include some pre-defined ones (reflecting different degrees of severity) and a fully customizable case. For educational facilitation, we used the example of climate change for the pre-defined scenarios. We used a narrative analogous to the concept of Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs). In particular, the mild scenario was meant to resemble RCP2.6, the moderate RCP4.5-6.0 and the extreme RCP8.5, just to give an indication of the conceptual connection of the RCP with the increased severity of the cases. So, the user can either select or develop their own scenario, according to Table 1. The pre-defined scenarios can also be used just as templates, allowing the user to modify all parameters.

Table 1.

Scenario configuration of the Floodport app [33,44].

The indicative numbers used for the three pre-defined scenarios were chosen from their respective typical values from the relevant literature concerning tides (Table 1, Figure 1b) [36,37]; storm surges [38,39]; the potential contribution of runoff [40,41]; climate-induced sea-level rise [42,43]; and combinations of the former [45,46,47]. Again, the scenario labels used (termed “mild”, “moderate”, and “extreme”) are intended only as pedagogical analogues that help students and stakeholders develop intuition about lower-, medium- and higher-impact scenarios. They are illustrative only: we map the labels loosely to broad classes of global emission pathways (commonly discussed in the literature, e.g., low/medium/high emission scenarios such as RCP2.6, RCP4.5–6.0, and RCP8.5) solely to convey relative differences in expected sea-level rise pace and extreme forcing (we do not perform local climate downscaling, stochastic extreme-event attribution, or site-specific hydrodynamic modelling to translate RCPs into precise local surge or precipitation values, as the app is not a process-based analytical tool). To avoid misuse, they can serve also as templates, while the “custom” scenario allows the user to experiment with any parameter value. We also include sensitivity tests across broad parameter ranges so readers can assess robustness to different plausible local conditions.

As the user choses or develops a scenario, the “flooding profile” and the “flooding over time” plots change interactively. In this process, the students take on the role of a coastal risk analyst, adjusting the key flooding parameters, as well as the height, H, of the engineering structure (the port dock) (Figure 1b). In-app explanatory comments are included for each parameter, so users develop a sense of the magnitudes and sensitivities involved.

2.4. Evaluation Through Statistical Analysis

Before Floodport was presented to the students, they completed a short set of questions that mainly aimed to depict their previous experience and understanding of the problem and its key parameters (pre-app, part a). This was supposed to serve as a measure of comparison with their understanding after using the app (post-app). For that purpose, at the end of the presentation, they completed a follow-up set of questions (post-app, part b), aiming to depict their post-app understanding of the problem, key parameters, and most helpful parts. The full questionnaire used is provided in Appendix A.

For the evaluation of the app’s performance, we estimated the basic descriptive statistics separately for the pre-app and post-app samples (independent and anonymous), including the mean (average rating) on a 1–5 Likert scale, the median, the middle response, and the standard deviation of the responses. This design was chosen to preserve respondent anonymity and encourage candid feedback in a large introductory cohort.

Next, we explored whether the post-app scores are reliably larger than the respective pre-app ones. Because the two samples are independent (responses are anonymous, so there is no pre-to-post comparison for the same student) and variances may differ, we used both a parametric test robust to unequal variances (Welch’s t-test) and a nonparametric rank test (Mann–Whitney U) as a robustness check [48,49]. Welch’s t-test tests the null hypothesis that the two samples’ means are equal against the alternative hypothesis that the two samples’ means are not equal. It then calculates the t-statistic (Equation (2)) and the degrees of freedom (Welch–Satterthwaite equation, Equation (3)) resulting in a fractional value that accounts for the unequal variances [50,51,52].

where n is the sample size (153 for both pre-app and post-app) and x denotes the sample’s mean.

Then, the t-statistic is compared to the t-distribution with the calculated degrees of freedom to find the p-value. If the p-value is less than the significance level (e.g., 0.05), we reject the null hypothesis, concluding that there is a statistically significant difference between the means (indicating that Floodport significantly improved the students’ understanding after using it). As a distribution-free robustness check, we compute the Mann–Whitney U test, which tests whether the post-app scores tend to be larger than the pre-app ones, assuming they come from independent samples that do not follow a specific distribution [50,53]. We also report standardized effect sizes through the Cohen’s d and Hedges’ g metrics, to quantify the difference between the mean scores of the pre- and post-app understanding [54]. These were all estimated through the Python (version 3.11.4) package scipy.stats [55].

2.5. Building More Advanced Modelling Representations

After presenting and evaluating the initial model version (beginner-level), we offer a roadmap for more advanced and realistic representations of this complex problem through a second version of the app. This “intermediate level” version incorporates the most important omitted processes of the initial model: wave set-up/run-up/overtopping, simple tide–surge nonlinearity, and basic drainage/runoff behaviour, plus a slightly more realistic bathymetric cross-section for inundation extent.

Here, we replace the single additive Equation (1) with an extended expression (Equation (4)):

where

- λ is a simple tide–surge interaction coefficient, to account for non-linear interactions among these phenomena. In shallow water the surge magnitude can depend on the tide due to quadratic bottom friction, where analyses have shown the dominant nonlinear tide–surge interaction scales with the product of surge and tide [56,57]. We thus include the term λ·tide·surge with λ ≪ 1, with typical λ values being, e.g., ~0.05–0.2, which would be calibrated from observations (according to [58,59,60]).

- is a wave/run-up term (accounting for set-up and run-up/overtopping contribution).

We group all wave-driven effects into one term ω (in metres). This aggregated wave term adds the extra water elevation from breaking waves and overtopping using standard empirical formulas. In practice, ω is often taken as the wave run-up elevation (peak water level at the shoreline), as, for example, Stockdon et al. [61] give the 2%-exceedance run-up level R2 which includes both set-up and swash, while many agencies (e.g., FEMA) use such formulas. In compact form, one can write that the wave set-up (nᵤ) can be expressed as the mean time–elevation increase at shore due to breaking waves, commonly expressed as:

where is the significant offshore wave height, the deep-water wavelength , with g = 9.81 m/s2, T is the peak wave period, and the factor β represents the mean foreshore slope. Empirical studies suggest C ≈ 0.2–0.4, so that roughly ≈ 0.2 Hs at many coastal areas.

The wave run-up (R), as the height of swash above the set-up, is parametrized according to the widely used formula by Stockdon et al. [61] (Equation (6)) as the 2%-exceedance run-up, combining set-up and swash components for steep slopes:

If there is a barrier of freeboard , waves may overtop it. Overtopping is usually treated as a discharge, q (m3/s per m). Design manuals [62,63] give an empirical expression (Equation (7)), depending on (or an equivalent term) and a friction factor , for example the following:

In our lumped model we do not compute discharge, but one could convert q to an equivalent water level increment if desired. For simplicity we incorporate overtopping effects qualitatively within the single term ω (for example, by choosing ω ≥ Rc when waves are high). We explicitly avoid full hydrodynamic simulation; instead, we use these well-known parameterizations of set-up/run-up and overtopping. Through the term β, bathymetry/slope parameters (local depths) appear in the wave formulas by this average or representative slope rather than full profiles. Incorporating full bathymetry would require additional data or modelling (e.g., SWASH simulations), which is beyond this version [64].

So, the term is a fraction (damping factor, δ) of the final , to reflect local dissipation or geometry (Equation (8)) [62,63,65,66]:

The new version is now included as an additional tab in the app, named “intermediate level”, with its key components described in Table 2. The key characteristics of each version (including a future build) are described in Table 3.

Table 2.

Summary of the main characteristics of the Floodport app’s “intermediate-level” version.

Table 3.

Summary of the main characteristics of the Floodport app’s model versions.

3. Results

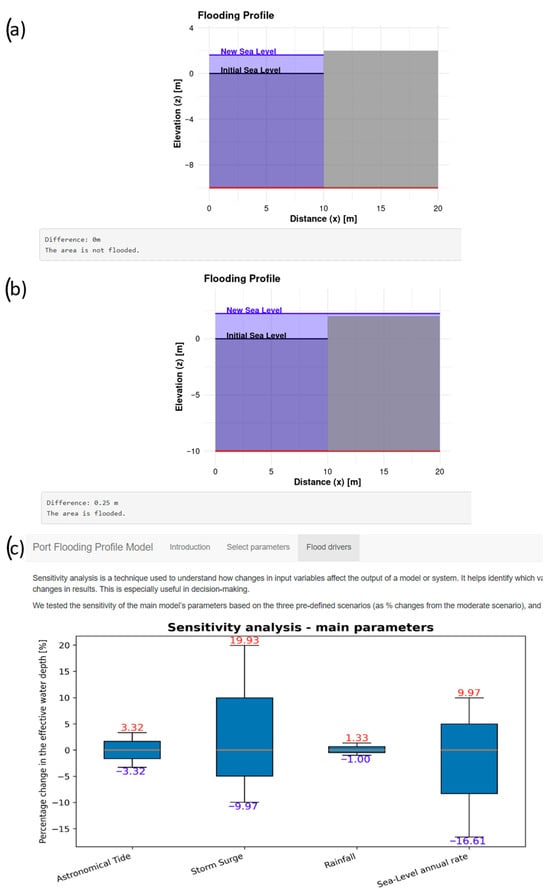

As the students interact with the app, change scenarios, and customize parameters, the water level changes immediately after any parameter modification, whereas, if there is a flood, the caption message indicates by how many meters (Figure 2a,b). The overall reaction of the students was positive and they seemed keen on experimenting with the app. Usually they tended to try and flood the port too much, to visualize a quite extreme destruction scenario. But after a few trials, they usually experimented with more mild and realistic scenarios. The progression of the explanation/interpretation of each outcome led naturally to the discussion around the main influencing factors and the concept of sensitivity. In the last tab of the app (Figure 2c), there is a default run showing the sensitivity of each customizable factor as estimated among the pre-defined scenarios (deterministic differences of the mild and extreme scenarios to the moderate one). The students had already “validated” this outcome in their experimentation with the model’s parameters, making their comprehension of the concept and the real-world mechanisms easier.

Figure 2.

A set of results from the Floodport app (beginner-level version): (a) flooding profile and differences in the moderate scenario (b) and the extreme scenario and (c) the tab with the “main flood drivers”, with the sensitivity visual.

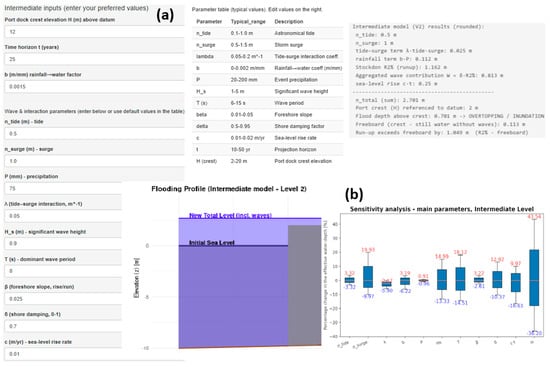

The intermediate-level version of the Floodport app extends the introductory additive formulation by incorporating additional physical processes that are known to play a critical role in coastal flooding, while still preserving transparency and usability for non-specialist users. As mentioned, in addition to tides, storm surges, rainfall, and long-term sea-level rise, this version introduces (i) a non-linear tide–surge interaction term, capturing the empirically observed amplification that can occur when these drivers coincide, and (ii) an aggregated wave contribution that represents wave set-up, run-up, and the potential for overtopping using well-established coastal engineering formulations. A simplified bathymetric representation through a foreshore slope parameter further allows users to visualize how coastal geometry influences inundation extent. Compared to the beginner-level model, which is intentionally minimal to support first exposure to the problem, the intermediate version’s results (Figure 3) demonstrate how additional drivers and interactions can introduce non-linearities and substantially increase water levels and flood impacts even under similar baseline conditions. Although this is a subsequent version that was not used in the classroom and only qualitatively described, the overall layered approach of the app allows learners to progressively build physical intuition, appreciate the limits of simplified models, and understand why more comprehensive formulations are required in engineering design and risk assessment, while still maintaining a level of complexity appropriate for educational and training applications.

Figure 3.

A set of results from the Floodport app (intermediate-level version): (a) flooding profile and differences in a customized scenario (parameter explanation, selection, and result visuals); (b) the tab with the “main flood drivers”, with the sensitivity visual.

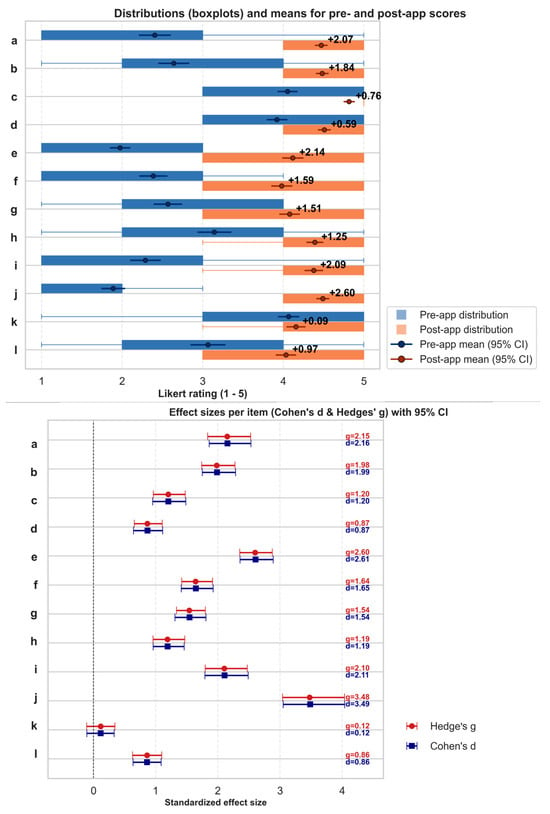

The analysis of the questionnaires on the app’s use was focused on the pre-app versus post-app understanding of certain factors—the “items” questioned (Figure 3). These refer to the following: (a) extreme storms, (b) sea-level rise, (c) climate change, (d) tides, (e) storm surges, (f) coastal floods, (g) port resilience, (h) engineering structures and works, (i) modelling and scenario analysis, (j) sensitivity analysis, (k) interactive apps, and (l) risk management and adaptation strategies (see also the questionnaire in Appendix A, Table A1, questions 1 and 2).

These sets of answers were obtained as scores on a 1–5 Likert scale for each item (a-l), for pre- and post-app attitudes. The Likert scale used the statements 1 = strongly disagree, up to 5 = strongly agree. The results were first summarized with the descriptive statistics mentioned in the previous section: the mean, median, and standard deviation (SD) show how students rated their knowledge/perception and the variability (how much agreement there was across students) before and after interacting with the app (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Upper plot: The mean and standard deviation with the distributions of the answers (n = 153) on a 1–5 Likert scale, rating pre-app (blue) and post-app (orange) understanding, shown as paired bar charts with 95% confidence interval (CI) error bars. Lower plot: The difference (change) in understanding scores per question item, as expressed through Cohen’s d and Hedges’ g.

The results indicate a generally large, consistent increase in self-rated knowledge across most items. For example, most items showed substantial mean increases after use of the app: extreme storms (a) from 2.41 to 4.47 (+2.07), storm surges (e) from 1.97 to 4.12 (+2.14), modelling and scenario analysis (i) from 2.29 to 4.38 (+2.09), and sensitivity analysis (j) from 1.89 to 4.49 (+2.60). Some other topics that were already well understood and which showed smaller gains were climate change (c), which had a relatively high pre-app mean (4.05) and increased to 4.82, and interactive apps (k), which showed minimal change. Overall, the post-app means were mostly around 4.0–4.8, their medians were 4 or 5, and the SDs were smaller than the respective pre-app ones for many items. This indicates that, after using Floodport, most students converged on higher ratings (a greater consensus that they understood the topics).

This finding was further supported by the independent sample comparison results, as all of the factors under consideration (items) showed large, statistically significant increases in the mean post- vs. pre-app self-reported scores. In particular, the Welch p and Mann–Whitney p were extremely small for most items, while the Cohen’s d and Hedges’ g ranged from medium to large values (around 0.8 and higher, up to >2), indicating large educational effects (Figure 3, lower plot). The largest mean gains were observed for sensitivity analysis (item j; mean difference ≈ +2.60; Hedges’ g = 3.48), which makes sense as the whole exercise was based on sensitivity logic, i.e., around a narrative of testing how different parameters affect flooding. Also, large gains were observed for storm surge (item e; +2.14; g = 2.60) and modelling and scenario analysis (item i; +2.09; g = 2.10). Item k (attitude toward interactive apps) showed minimal change. The effect size results from the Mann–Whitney tests were large, indicating strong perceived learning gains (for the detailed results, see Appendix A, Table A2).

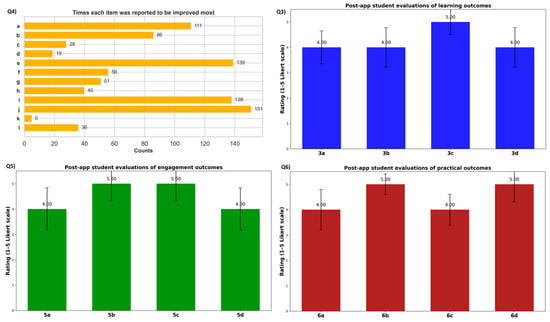

The large knowledge gain per question item is largely reflected in the factors that students stated they understood more post-app (Figure 5, Q4). The items for which students reported/felt the largest gains (“most improved”) were j (sensitivity analysis), e (storm surges), i (modelling/scenario analysis), and a (extreme storms), indicating the dual role of Floodport in explaining both modelling processes and natural phenomena.

Figure 5.

The results from the rest of the questionnaire answers. Q4 (question 4): The frequency that the students reported one or more items (same items a-l as in the previous figure) as majorly improved in terms of comprehension. Q3 (question 3): Likert-scale agreement scores concerning the learning value of the app for flood drivers (3a), interconnections of environmental and engineering factors (3b), analytical and management aspects (3c), and modelling and sensitivity analysis (3d). Q5 (question 5): Likert-scale agreement scores concerning the overall engagement experience (5a), the positive role of real-time visuals in understanding (5b), scenario analysis (5c), and experimentation with the app (5d). Q6 (question 6): Likert-scale agreement scores for the positive role of the app in understanding relevant engineering decisions (6a) and complex challenges (6b) and in motivating them to further study adaptation strategies (6c) and real-world cases (6d).

Of course, these are self-reported results; the students reported very high knowledge gains, reflecting their feelings of strong immediate boosts in perceived knowledge from interacting with the Floodport app. This, combined with their mostly very low pre-app self-ratings (as they actually did not have previous knowledge on the topic) resulted in such high gains.

The rest of the questions asked students to rate their agreement, on a 1–5 Likert scale, with statements relevant to the usefulness of the app in learning terms (Q3—question 3), engagement with the topics explored (Q5—question 5), and the practical implications in engineering, decision-making and management (Q6—question 6). The detailed phrasing of the questions can be found in Appendix A, Table A1, questions 3–6. All of the results were near the upper end of the Likert scale, indicating strong perceived gains.

In terms of Floodport’s role in learning terms (Q3), the highest mean is for the achievement of a more “integrated understanding across analytical, engineering and management aspects” (3c), suggesting an effectively promotion of systems-level synthesis. Engagement indicators (Q5) are uniformly high, with statements on the “real-time visualizations” (5b) and “scenario exploration” (5c) peaking at a perfect mean of 5.00. Practical and application-oriented ratings (Q6) are also strong, with students feeling more familiar with the challenges that engineers face, the factors they need to consider, and how flood management becomes a complex real-world problem. The standard deviations of all of the questions indicate modest variations across respondents: while most students rated each item positively, there remains heterogeneity in the strength of the effect (e.g., some students might have been less engaged).

Overall, these findings imply that the app succeeded not only in building conceptual knowledge, but also in fostering applied competence and readiness to make engineering or management judgments. As mentioned, there might also be high immediate post-app confidence that was reflected in the students’ self-reported high scores; however, this is also a role (and co-benefit) of this app, as it is more of an introductory and motivational tool to further deepen the study of such problems and responses.

4. Discussion

Use of the Floodport app was in general well perceived, with the students finding it an enjoyable experience, which led to an increased motivation for further engagement across all classrooms. Analysis of the questionnaires’ answers showed clear, practically important improvements in self-reported understanding across many topics, helping the sample to grasp interacting hazards and analytical methods (modelling, sensitivity). The pre–post patterns support the pedagogical value of an interactive, scenario-based approach, which seems to be quite useful, especially for complex, system-level concepts that students initially rate low.

Floodport’s standard beginner-level version intentionally omits a few processes that are important in advanced coastal engineering, so, we comment on these here, as “intentional limitations”. For example, wave run-up and breaking, dynamic hydrodynamic propagation across complex bathymetry, seafloor slopes, and long-term seabed evolution. These phenomena require more sophisticated models and data and are outside the scope of an introductory educational tool [67,68]. The simplifications are intentional to allow students to first build core conceptual understanding and to practice scenario thinking before tackling advanced modelling. In class, we explicitly state these limitations and discuss how next-stage models incorporate them. Thus, Floodport’s beginner-level version acts as a scaffold: once students understand how tide, surge, rainfall and sea-level rise combine to change water level, then the instructors can introduce additional physics. Because students already appreciate the baseline and the combination-effects logic, they are prepared to understand how additional terms or nonlinear models modify outcomes (as proved by the survey’s results). At this stage, the developed intermediate-level module of the app considers more factors that can control real flood impacts in ports, such as wave-driven processes (set-up, run-up, overtopping), non-linearity, bathymetric slope, and other engineering interventions.

As shown, the app provides a sensitivity analysis of the main model’s parameters (both for the beginner-level and the intermediate-level versions). The app’s presentation process and its progression, ending with this analysis, helps students to interpret results and think more critically, with the use of built-in questions like “Interpretation? What can engineers do to protect a port from flooding? (Think about how to analyze all parameters used, and which ones can be affected!)”, etc. At some points, the discussion continued further, with questions like “If we wanted to estimate the parameter b, or c, for a real port, what would we do?”, or “what data would we need?” This prompted thinking about data, uncertainty, model development, and model calibration. In any case, Floodport is designed and evaluated as a pedagogical tool for classroom and stakeholder engagement rather than as a new hydrologic forecasting or design methodology. Classical hydrologic approaches are more appropriate for detailed, site-specific flood hazard assessment and design. By contrast, Floodport trades process detail for transparency, interactivity and speed: it brings students and non-specialists rapidly up to speed with a shared mental model of how tides, storm surges, waves, rainfall, and engineering measures combine to produce inundation at ports. The survey’s results reflect the perceived gains, which are important pedagogical outcomes because they predict motivation, further study, and willingness to engage in adaptation planning, but they do not substitute objective measures of conceptual mastery. Future work for the testing apps’ contributions could complement this approach with within-subject paired testing, objective knowledge quizzes, practical exercises, and delayed follow-up to assess knowledge retention and transfer. The consistent, large effect sizes observed across multiple items in the present study, however, provide strong convergent evidence that the Floodport app had an immediate and substantial effect on students’ confidence and perceived understanding in the classroom setting.

We believe that this particular emphasis on the more basic concepts is crucial. In fact, several students expressed (informally) their “relief” about such an approach, as usually they feel that most instructors put the emphasis only (or mainly) on more advanced concepts that are, naturally, closer to their research, and this is hard to follow. Such educational gaps/challenges have also been mentioned in previous studies [69,70,71].

5. Conclusions

The Floodport app serves as a dynamic educational tool designed to bridge the gap between initial or even limited theoretical knowledge and real-world consideration and applications relevant to coastal flood risk management.

The app has been developed in different formats to boost its usability and applicability: The Shinny App is freely available by Nagkoulis et al. [44] (Github link also provided). There is also an Excel version, where the plots are generated in Python, which is available upon request.

The strong, consistent gains we observed in student understanding, engagement, and perceived ability to feel more familiar with model thinking (logic) and insights suggest the app translates complex interactions (storm surge, sea-level rise, rainfall, and infrastructure response) into intuitive, experientially meaningful learning. This success in a classroom setting makes us optimistic about Floodport’s broader use in other environments, too. For example, stakeholder workshops, in the form of living labs, or in general public participation set-ups, that in their initial stages require building a basic understanding of the complex problems they aim to address [72,73]. The same interactive “what-if” controls and immediate visual outputs that helped students grasp sensitivity analysis, multiple drivers, and scenario trade-offs can quickly bring non-specialists and users without previous knowledge on the topic (such as port managers, local planners, community leaders, etc.) to a shared understanding of flood risk [74,75]. Rather than relying on technical reports and summaries, workshop participants can test plausible scenarios and think of possible adaptation options (as follow-up actions). The consideration of such adaptation measures in the Floodport app is included in our ongoing and future research plans. At this point, we should note, again, that Floodport is intended strictly as a training and capacity-building tool, not as a decision-support or engineering design platform. It does not aim to replace detailed hydrodynamic models, uncertainty analysis, or cost–benefit assessments, which are required for operational decision-making and are explicitly beyond the scope of this work. However, it can complement them: by building an initial understanding of the problem through Floodport, other simulation-based or multi-software decision-support tools can be used for planning. In that context, while workshops should pair the app with facilitation and local data calibration, Floodport’s ability to facilitate modelling logics and interpretation makes it a powerful bridge between technical knowledge and practical thinking for diverse audiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and O.N.; methodology, A.A., N.N., P.K., and O.N.; software, A.A. and N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A., N.N., P.K., and O.N.; writing—review and editing, A.A., N.N., P.K., and O.N.; funding acquisition: P.K. and O.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

(a) European Research Council (ERC) under the ERC Synergy Grant Water-Futures grant agreement ID 951424. (b) Project: Modelling coastal flood risks under climate change conditions, for data-scarce areas. Educational app Floodport.

Data Availability Statement

All data and code is available at https://github.com/Alamanos11/Floodport (accessed on 7 January 2026) while the web-app is accessible through this link: https://auebports.shinyapps.io/Floodport/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The questionnaire used for the pre–post app evaluation.

Table A1.

The questionnaire used for the pre–post app evaluation.

| Section A.1: Pre-App Goal: Assess students’ prior knowledge on the topics touched by Floodport. |

| 1. Self-rated prior knowledge (Pre-App): On a scale from 1 (no knowledge) to 5 (excellent knowledge), rate your understanding of the following topics before using the interactive app: a. Extreme storms: Understanding the impacts of extreme weather events on coastal regions………… b. Sea-level rise: Long-term trends driven by climate change and their impact on coastal infrastructures……………… c. Climate change: How global warming is linked to sea-level rise and weather extremes (e.g., sea-rise rate, rainfall contribution factor)……………… d. Tides: Their role in coastal flooding……………….. e. Storm surges: How additional water levels during storms interact with normal tides……………….. f. Coastal floods: How combined hazards affect coastal inundation……………….. g. Port resilience: How engineered structures (e.g., port docks) are evaluated for flood risk……………… h. Engineering structures and works: Design and performance of port infrastructures in flood events…………… i. Modelling and scenario analysis: Using simplified models and computational tools to simulate flood hazards……………… j. Sensitivity analysis: Identifying key parameters that affect flooding…………… k. Interactive apps: Their usefulness in exploring “what-if” scenarios…………. l. Risk management and adaptation strategies: Understanding common mitigation strategies………….. |

| Section A.2: Learning Outcomes [post-app] |

| 2. Self-rated understanding (Post-App): On a scale from 1 (no knowledge) to 5 (excellent knowledge), rate your understanding of the following topics after using the interactive app: a. Extreme storms: Understanding the impacts of extreme weather events on coastal regions………… b. Sea-level rise: Long-term trends driven by climate change and their impact on coastal infrastructures……………… c. Climate change: How global warming is linked to sea-level rise and weather extremes (e.g., sea-rise rate, rainfall contribution factor)……………… d. Tides: Their role in coastal flooding……………….. e. Storm surges: How additional water levels during storms interact with normal tides……………….. f. Coastal floods: How combined hazards affect coastal inundation……………….. g. Port resilience: How engineered structures (e.g., port docks) are evaluated for flood risk……………… h. Engineering structures and works: Design and performance of port infrastructures in flood events…………… i. Modelling and scenario analysis: Using simplified models and computational tools to simulate flood hazards……………… j. Sensitivity analysis: Identifying key parameters that affect flooding…………… k. Interactive apps: Their usefulness in exploring “what-if” scenarios…………. l. Risk management and adaptation strategies: Understanding common mitigation strategies………….. |

| 3. Agreement with integrated understanding: Using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), indicate your level of agreement with each statement: a. “The interactive app helped me understand how extreme storms, sea-level rise, and storm surges combine to produce coastal floods.” b. “I now (after using the app) see interconnections between climate change, natural hazards, and the role of engineering structures such as port docks.” c. “After using the app, I have a more integrated understanding of the analytical, engineering, and management aspects of coastal flood risk.” d. “I understand the role and importance of sensitivity analysis and scenario modelling in evaluating flood hazards.” |

| 4. Topics of greatest improvement: Which topics do you feel you learned the most about through the interactive app? (Select all that apply): a. Extreme storms, b. Sea-level rise, c. Climate change, d. Tides, e. Storm surges, f. Coastal floods, g. Port resilience, h. Engineering structures, i. Modelling & scenario analysis, j. Sensitivity analysis, k. Interactive apps, l. Risk management. |

| Section B: Engagement through interactive learning Goal: Measure the degree to which the interactive app engages students and enhances their understanding of combined hazards. |

| 5. Engagement: Please rate your agreement with the following statements (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree): a. “The app was interactive and engaging.” b. “The real-time visualizations helped me grasp the complex interactions between coastal flooding drivers.” c. “Exploring different scenarios in the app enhanced my understanding of coastal flooding” d. “I felt motivated to experiment with the model to see what-if scenarios.” |

| Section C: Real-world application awareness Goal: Evaluate whether the interactive app helps students relate model outputs to real-world engineering decisions and risk management in coastal flood scenarios. |

| 6. Practical implications Please rate your agreement with the following statements (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree): a. The app improved my perception in relevant applications to engineering decisions, by relating the flood profiles (scenario outputs) to actual port design and flood risk management cases. b. The app improved my perception of the main challenges that port managers face when addressing flood hazards that combine multiple hazards. c. After using the app, I feel more motivated and capable to study and design adaptation strategies that could enhance port resilience. d. Overall, the app improved my ability to connect theoretical flood models to real-world situations and management aspects. |

For each questionnaire item (questions 1 and 2 above) we plot horizontal boxplots of the raw Likert scores (pre and post) showing median and interquartile range (whiskers to 1.5 × IQR). Over each box we overlay the sample mean and an approximate 95% confidence interval. The detailed results of Figure 3 are shown in Table A2 below.

Table A2.

The statistic results of the questionnaire survey.

Table A2.

The statistic results of the questionnaire survey.

| Question’s Item | Mean (Pre ± SD) | Mean (Post ± SD) | Mean Δ (Post − Pre) | 95% CI (Diff) | t (Welch) | p (Welch) | U Statistic | p (Mann–Whitney) | Cohen’s d | Hedges’ g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 2.405 ± 1.259 | 4.471 ± 0.501 | 2.07 | [1.849, 2.281] | 18.86 | <0.001 *** | 21,280.5 | <0.001 | 2.156 | 2.151 |

| b | 2.641 ± 1.212 | 4.484 ± 0.501 | 1.84 | [1.634, 2.052] | 17.38 | <0.001 *** | 21,017 | <0.001 | 1.988 | 1.983 |

| c | 4.052 ± 0.785 | 4.817 ± 0.436 | 0.76 | [0.622, 0.908] | 10.54 | <0.001 *** | 17,979.5 | <0.001 | 1.205 | 1.202 |

| d | 3.922 ± 0.815 | 4.510 ± 0.502 | 0.59 | [0.436, 0.741] | 7.6 | <0.001 *** | 16,366.5 | <0.001 | 0.869 | 0.867 |

| e | 1.974 ± 0.811 | 4.118 ± 0.835 | 2.14 | [1.959, 2.329] | 22.79 | <0.001 *** | 22,329 | <0.001 | 2.606 | 2.599 |

| f | 2.386 ± 1.095 | 3.980 ± 0.823 | 1.59 | [1.377, 1.813] | 14.4 | <0.001 *** | 19,959 | <0.001 | 1.647 | 1.642 |

| g | 2.569 ± 1.117 | 4.078 ± 0.815 | 1.51 | [1.290, 1.730] | 13.51 | <0.001 *** | 19,612.5 | <0.001 | 1.544 | 1.54 |

| h | 3.144 ± 1.325 | 4.392 ± 0.661 | 1.25 | [1.012, 1.484] | 10.43 | <0.001 *** | 18,036.5 | <0.001 | 1.192 | 1.189 |

| i | 2.288 ± 1.201 | 4.379 ± 0.726 | 2.09 | [1.868, 2.315] | 18.43 | <0.001 *** | 21,225.5 | <0.001 | 2.108 | 2.102 |

| j | 1.889 ± 0.929 | 4.490 ± 0.502 | 2.6 | [2.433, 2.769] | 30.48 | <0.001 *** | 22,824 | <0.001 | 3.485 | 3.477 |

| k | 4.065 ± 0.833 | 4.157 ± 0.744 | 0.09 | [−0.086, 0.269] | 1.01 | 0.312 (ns) | 12,273.5 | 0.432 (ns) | 0.116 | 0.116 |

| l | 3.065 ± 1.370 | 4.033 ± 0.798 | 0.97 | [0.715, 1.220] | 7.55 | <0.001 *** | 16,411 | <0.001 | 0.863 | 0.861 |

Note: where * (e.g., p < 0.05), ** (e.g., p < 0.01), and *** (e.g., p < 0.001).

References

- Xu, L.; Cui, S.; Wang, X.; Tang, J.; Nitivattananon, V.; Ding, S.; Nguyen Nguyen, M. Dynamic Risk of Coastal Flood and Driving Factors: Integrating Local Sea Level Rise and Spatially Explicit Urban Growth. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 129039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Tang, W.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z. Assessment of the Effects of Natural and Anthropogenic Drivers on Extreme Flood Events in Coastal Regions. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Haigh, I.; Quinn, N.; Neal, J.; Wahl, T.; Wood, M.; Eilander, D.; de Ruiter, M.; Ward, P.; Camus, P. Review Article: A Comprehensive Review of Compound Flooding Literature with a Focus on Coastal and Estuarine Regions. EGUsphere 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanos, A.; Linnane, S. Systems Resilience to Floods: A Categorisation of Approaches. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly, Vienna, Austria, 27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Sánchez, M.; Moñino, A.; Bergillos, R.J.; Magaña, P.; Clavero, M.; Díez-Minguito, M.; Baquerizo, A. Confronting Learning Challenges in the Field of Maritime and Coastal Engineering: Towards an Educational Methodology for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, V.; Richard, A. Exploring the Interconnected Nature of the Sustainable Development Goals: The 2030 SDGs Game as a Pedagogical Tool for Interdisciplinary Education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 25, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morote, Á.-F.; Olcina, J. Preventing through Sustainability Education: Training and the Perception of Floods among School Children. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaras, A.G.; Karambas, T.V. Modelling the Impact of Climate Change on Coastal Flooding: Implications for Coastal Structures Design. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, S.L.; Dzwonkowski, B. The Role of Intensifying Precipitation on Coastal River Flooding and Compound River-Storm Surge Events, Northeast Gulf of Mexico. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, S.; Barnard, P.L.; Fletcher, C.H.; Frazer, N.; Erikson, L.; Storlazzi, C.D. Doubling of Coastal Flooding Frequency within Decades Due to Sea-Level Rise. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, R.; Tavakol-Davani, H.; Graves, C.; Gomez, A.; Fazel Valipour, M. Compound Inundation Impacts of Coastal Climate Change: Sea-Level Rise, Groundwater Rise, and Coastal Precipitation. Water 2020, 12, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanos, A.; Koundouri, P. Science-Supported Policies to Achieve Environmental Sustainability under Crises. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Water Policy, Economics and Management; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 230–233. ISBN 978-1-80220-294-6. [Google Scholar]

- Alamanos, A.; Linnane, S. Drought Monitoring, Precipitation Statistics, and Water Balance with Freely Available Remote Sensing Data: Examples, Advances, and Limitations. In Proceedings of the Irish National Hydrology Conference 2021, Athlone, Ireland, 26–27 April 2021; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Karamouz, M.; Taheri, M.; Khalili, P.; Chen, X. Building Infrastructure Resilience in Coastal Flood Risk Management. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punt, E.; Monstadt, J.; Frank, S.; Witte, P. Beyond the Dikes: An Institutional Perspective on Governing Flood Resilience at the Port of Rotterdam. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2023, 25, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanos, A.; Papaioannou, G.; Varlas, G.; Markogianni, V.; Plataniotis, A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Dimitriou, E.; Koundouri, P. Designing Post-Fire Flood Protection Techniques for a Real Event in Central Greece. Prev. Treat. Nat. Disasters 2024, 3, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, S.; Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Blackett, P.; Edwards, P. Adaptive and Interactive Climate Futures: Systematic Review of ‘Serious Games’ for Engagement and Decision-Making. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 063005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, S.A.; Kubíková, M.; Macháč, J. Serious Gaming in Flood Risk Management. WIREs Water 2022, 9, e1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanos, A.; Koundouri, P. Multi-Stakeholder Platforms for Water Management: Connecting Policy and Science. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual International Conference on Sustainable Development (ICSD), Online, 19–20 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, J.A.; Alamanos, A. A Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Water Resources Allocation Considering Stakeholder Input. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 25, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanos, A.; Kolokytha, E.; Mylopoulos, Y. A Science-to-Policy Capacity Development Process for Flood Protection. In Proceedings of the 41st IAHR World Congress, Singapore, 22–27 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Koundouri, P.; Alamanos, A.; Papaioannou, G.; Markogianni, V.; Varlas, G.; Basheer, M.; Nagkoulis, N.; Plataniotis, A.; Wise, R.M.; Xenarios, S.; et al. Post-Fire Flood Hazards: Integrated Modelling, Protection Measures, Economic and Policy Implications; Report; UN SDSN Global Climate Hub: Athens, Greece, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, A.J.; Robinson, B.; O’Rourke, M.; Begg, M.D.; Larson, E.L. Building Interdisciplinary Research Models Through Interactive Education. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2015, 8, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiroglu, E.; Grant, C.A.; Sermet, Y.; Demir, I. Floodcraft: Game-Based Interactive Learning Environment Using Minecraft for Flood Mitigation for K-12 Education. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 130, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiray, B.Z.; Sermet, Y.; Yildirim, E.; Demir, I. FloodGame: An Interactive 3D Serious Game on Flood Mitigation for Disaster Awareness and Education. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 188, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.N.; Castro, M.d.A.R.A.; da Silva, P.G.C.; Giacomoni, M.H.; Mendiondo, E.M. Increasing Flood Awareness through Dam-Break Serious Games. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108, 104543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meera, P.; McLain, M.L.; Bijlani, K.; Jayakrishnan, R.; Rao, B.R. Serious Game on Flood Risk Management. In Emerging Research in Computing, Information, Communication and Applications, Proceedings of the ERCICA: International Conference on Emerging Research in Computing, Information, Communication and Applications, Bangalore, India, 29–30 July 2016; Shetty, N.R., Prasad, N.H., Nalini, N., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, R.; Sewilam, H.; Nacken, H.; Pyka, C. Exploring the Application of a Flood Risk Management Serious Game Platform. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becu, N.; Amalric, M.; Anselme, B.; Beck, E.; Bertin, X.; Delay, E.; Long, N.; Marilleau, N.; Pignon-Mussaud, C.; Rousseaux, F. Participatory Simulation to Foster Social Learning on Coastal Flooding Prevention. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 98, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarino, S.; Musacchio, G.; Eva, E.; Anzidei, M.; De Lucia, M. Inundation: A Gaming App for a Sustainable Approach to Sea Level Rise. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincke, D.; Hinkel, J.; Mengel, M.; Nicholls, R.J. Understanding the Drivers of Coastal Flood Exposure and Risk From 1860 to 2100. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, B.S.; McGregor, S.; Jones, D.A.; Reef, R.; Jakob, D.; Murphy, B.F. The Global Drivers of Chronic Coastal Flood Hazards Under Sea-Level Rise. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2023EF003784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanos, A.; Nagkoulis, N.; Koundouri, P.; Nisiforou, O. Floodport: An Interactive Coastal Flood Risk Training App. In Proceedings of the 6th IAHR Young Professionals Congress; Higher Education and E-learning Session, Online. 3 December 2025. [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre, R.; Onggo, B.S.; Corlu, C.G.; Nogal, M.; Juan, A.A. The Role of Simulation and Serious Games in Teaching Concepts on Circular Economy and Sustainable Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adipat, S.; Laksana, K.; Busayanon, K.; Asawasowan, A.; Adipat, B. Engaging Students in the Learning Process with Game-Based Learning: The Fundamental Concepts. Int. J. Technol. Educ. 2021, 4, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Liu, L.; Hu, H.; Shi, Z.; Ren, D.; Wang, G.; Liang, X.; Sun, X. Tidal Evolution and Predictable Tide-Only Inundation Along the East Coast of the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2023, 128, e2022JC019410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalinghaus, C.; Coco, G.; Higuera, P. Assessing Total Water Level Uncertainties Using Global Sensitivity Analysis. Authorea 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarieh, B.; Ugwu, I.A.; Salman, A.M. Impact of Changes in Sea Surface Temperature Due to Climate Change on Hurricane Wind and Storm Surge Hazards across US Atlantic and Gulf Coast Regions. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Hou, X.; Li, D.; Zheng, X.; Fan, C. Projections of Coastal Flooding under Different RCP Scenarios over the 21st Century: A Case Study of China’s Coastal Zone. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2022, 279, 108155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, Z.A. Runoff Coefficient (C Value) Evaluation and Generation Using Rainfall Simulator: A Case Study in Urban Areas in Penang, Malaysia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, R.; Lyu, L.; Wu, Y.; Bilodeau, J.-P.; Wen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Pei, J. Rainfall Runoff Response Characteristics of Typical Urban Roads Based on Laboratory Tests. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 135, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Church, J.A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Reconciling Global Mean and Regional Sea Level Change in Projections and Observations. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Hanson, S.E.; Lowe, J.A.; Slangen, A.B.A.; Wahl, T.; Hinkel, J.; Long, A.J. Integrating New Sea-Level Scenarios into Coastal Risk and Adaptation Assessments: An Ongoing Process. WIREs Clim. Change 2021, 12, e706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagkoulis, N.; Alamanos, A.; Koundouri, P.; Nisiforou, O. The Floodport App for Interactive Coastal Flooding Training. 2025. Available online: https://auebports.shinyapps.io/Floodport (accessed on 24 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Muis, S.; Verlaan, M.; Winsemius, H.C.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Ward, P.J. A Global Reanalysis of Storm Surges and Extreme Sea Levels. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, A.; Christidis, P.; Demirel, H. Sea-Level Rise in Ports: A Wider Focus on Impacts. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2019, 21, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Church, J.A.; Watson, C.S.; King, M.A.; Monselesan, D.; Legresy, B.; Harig, C. The Increasing Rate of Global Mean Sea-Level Rise during 1993–2014. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonick, L.; Smith, W. Cartoon Guide to Statistics; William Morrow Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-06-273102-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ruxton, G.D. The Unequal Variance T-Test Is an Underused Alternative to Student’s t-Test and the Mann–Whitney U Test. Behav. Ecol. 2006, 17, 688–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.L. The Generalization of `Student’s’ Problem When Several Different Population Variances Are Involved. Biometrika 1947, 34, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.S.; Skrondal, A. The Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-511-78761-4. [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite, F.E. An Approximate Distribution of Estimates of Variance Components. Biom. Bull. 1946, 2, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, W.P.; Johnson, R.B. Dictionary of Statistics & Methodology: A Nontechnical Guide for the Social Sciences; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4129-7109-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, D.W. A Note on Preliminary Tests of Equality of Variances. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2004, 57, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramkowski, G.P.; Schuttelaars, H.M.; de Swart, H.E. The Effect of Geometry and Bottom Friction on Local Bed Forms in a Tidal Embayment. Cont. Shelf Res. 2002, 22, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.B. Frictional Effects on the Tidal Dynamics of a Shallow Estuary (Compound, Surge-Tide, River-Tide Interaction)—ProQuest. Ph.D. Thesis, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J. Interaction of Tide and Surge in a Semi-Infinite Uniform Channel, with Application to Surge Propagation down the East Coast of Britain. Appl. Math. Model. 1978, 2, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). MDL Storm Surge. Available online: https://slosh.nws.noaa.gov/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- NOAA National Weather Service. NOAA ATLAS 14 POINT PRECIPITATION FREQUENCY ESTIMATES. PF Map: Contiguous US. Available online: https://hdsc.nws.noaa.gov/pfds/pfds_map_cont.html?lat=39.9907&lon=-82.8770 (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Stockdon, H.F.; Holman, R.A.; Howd, P.A.; Sallenger, A.H. Empirical Parameterization of Setup, Swash, and Runup. Coast. Eng. 2006, 53, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EurOtop. EurOtop Manual: Wave Overtopping of Sea Defences and Related Structures. A Manual and Online Calculation Tool for Predicting Overtopping, Flood Volumes and Drainage Requirements for a Range of Seawall Types. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/flood-and-coastal-erosion-risk-management-research-reports/eurotop-manual-wave-overtopping-of-sea-defences-and-related-structures (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- EurOtop. EurOtop Manual: Wave Overtopping of Sea Defences and Related Structures. A Manual and Online Calculation Tool for Predicting Overtopping, Flood Volumes and Drainage Requirements for a Range of Seawall Types. 2018. Available online: https://www.overtopping-manual.com/assets/downloads/EurOtop_II_2018_Final_version.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- da Silveira, C.B.L.; Strenzel, G.M.R.; Maida, M.; Araújo, T.C.M.; Ferreira, B.P. Multiresolution Satellite-Derived Bathymetry in Shallow Coral Reefs: Improving Linear Algorithms with Geographical Analysis. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 36, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. Guidance for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping Coastal Wave Runup and Overtopping; FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA. Guidance for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping Coastal Wave Runup and Overtopping; FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, M.; Sofia, G.; Koukoula, M.; Lazin, R.; Nikolopoulos, E.I.; Shen, X.; Anagnostou, E.N. Impact of Compound Flood Event on Coastal Critical Infrastructures Considering Current and Future Climate. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijnse, T.; van Ormondt, M.; Nederhoff, K.; van Dongeren, A. Modeling Compound Flooding in Coastal Systems Using a Computationally Efficient Reduced-Physics Solver: Including Fluvial, Pluvial, Tidal, Wind- and Wave-Driven Processes. Coast. Eng. 2021, 163, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, F.; ten Hagen, I. Do Teachers’ Perceived Teaching Competence and Self-Efficacy Affect Students’ Academic Outcomes? A Closer Look at Student-Reported Classroom Processes and Outcomes. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 56, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.Y.; Theobald, E.J.; Abraham, J.K.; Price, R.M. Reframing Educational Outcomes: Moving beyond Achievement Gaps. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2022, 21, es2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merayo, N.; Ayuso, A. Analysis of Barriers, Supports and Gender Gap in the Choice of STEM Studies in Secondary Education. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2023, 33, 1471–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanos, A.; Koundouri, P.; Papadaki, L.; Pliakou, T.; Toli, E. Water for Tomorrow: A Living Lab on the Creation of the Science-Policy-Stakeholder Interface. Water 2022, 14, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roukounis, C.N.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Climate Change Adaptation Strategies for Coastal Resilience: A Stakeholder Surveys. Water 2024, 16, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijer, E. Designing and Implementing Data Collaboratives: A Governance Perspective. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slinger, J.H.; Cunningham, S.C.; Kothuis, B.L.M. A Co-Design Method for Including Stakeholder Perspectives in Nature-Based Flood Risk Management. Nat. Hazards 2023, 119, 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.