1. Introduction

Forest canopy structure strongly regulates rainfall partitioning and influences infiltration, evapotranspiration, and surface runoff. Understanding these processes is essential for managing water resources and ecosystem resilience in semi-dry forests [

1,

2]. Silvicultural practices, particularly selective thinning, have long been implemented to improve soil water availability in semi-arid forest ecosystems [

3,

4,

5]. However, the intensity of vegetation removal strongly influences hydrological responses. Higher thinning intensities tend to reduce canopy interception [

6,

7,

8], lower evapotranspiration rates [

9,

10], and ultimately increase the amount of water reaching the soil surface [

11].

The impacts of thinning on runoff dynamics encompassing spatial and temporal variability across multiple scales and the factors driving these patterns, have been extensively investigated [

3,

5,

11]. Harvest intensity and catchment size have consistently been identified as key determinants of hydrological responses [

12,

13,

14]. For instance, several studies have reported greater runoff and water yield in ponderosa pine stands subjected to high-intensity thinning compared with denser stands [

3,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, hydrological responses observed at the (Micro-catchment) scale do not necessarily mirror those observed at the broader catchment level [

17]. For instance, Dung et al. (2012) observed an increase in streamflow following a 50% thinning treatment at the catchment scale [

4], even though no significant increase in surface runoff was detected within the constituent MC. These findings suggest that subsurface runoff at the catchment scale may depend on the continuity or discontinuity of hydrological processes occurring within smaller catchments [

2,

4,

18,

19]. Overall, hydrological processes vary substantially across the upper, middle, and lower sections of a catchment, primarily due to differences in vegetation structure, soil properties, and local climatic conditions [

20,

21]. Consequently, runoff responses rarely exhibit a uniform trend, underscoring the importance of assessing hydrological behavior across multiple spatial scales, particularly in semi-arid regions [

22,

23].

Semi-dry forests account for approximately 6% of the global forest cover and are considered among the most fragile ecosystems worldwide [

24,

25]. In Mexico, these forests extend over approximately 22 million hectares, typically forming oak–pine associations at elevations ranging from 1400 to 2600 m a.s.l. [

26,

27,

28]. Beyond their ecological importance, semi-dry forests provide essential ecosystem services that support forestry, agriculture, grazing, and diversified livelihood strategies within local communities [

24]. Critically, these areas also play a key role in water provision, supplying irrigation districts that sustain high-yield commercial agriculture and fulfilling domestic and industrial water demands in downstream urban centers [

29].

Hydrological research commonly employs a wide range of methodological approaches, including time series analysis, probabilistic modeling of key variables such as precipitation and runoff, nonlinear modeling techniques, multivariate statistical analyses, and remote sensing applications, all of which are fundamental for a comprehensive understanding of hydrological processes [

30,

31]. To rigorously evaluate the effects of silvicultural treatments such as thinning, the Before–After–Control–Impact (BACI) framework is widely recognized as a robust experimental design for environmental impact assessment. This approach relies on comparisons between treatment and control sites both before and after intervention, enabling the differentiation of treatment-induced effects from natural spatial and temporal variability [

32,

33].

Runoff generation in forested catchments is governed by multiple interacting factors, including topography, soil properties, vegetation structure, rainfall characteristics, and management history [

11,

34]. These variables interact nonlinearly across spatial and temporal scales, producing diverse hydrological responses even under similar rainfall conditions [

4,

34]. However, isolating the effects of specific drivers such as canopy structure requires experimental designs implemented under relatively homogeneous physiographic and climatic settings, where the influence of confounding variables is minimized and process-level interpretations can be made with greater confidence.

Despite the substantial body of research evaluating the hydrological effects of forest thinning, important gaps remain, particularly regarding event-scale runoff responses under controlled environmental conditions. Most studies have assessed thinning effects across catchments that differ in topography, soils, or vegetation structure, making it difficult to isolate the role of canopy cover alone in regulating surface runoff [

4,

17,

18,

19]. Even in semi-arid regions—where threshold-type hydrological behavior is common—empirical evidence based on event-scale observations remains limited [

11,

22,

23,

34]. In northern Mexico, previous research has examined soil moisture and infiltration dynamics in semi-dry forests [

34,

35], yet no study has experimentally quantified how standardized reductions in canopy cover influence event-based runoff generation under otherwise homogeneous physiographic conditions. Although isolating hydrological drivers in field environments is inherently challenging, addressing this gap remains essential for improving process-level interpretations of rainfall–runoff responses and for informing silvicultural practices aimed at optimizing water yield in semi-dry forests.

Empirical hydrological data from dry forests in northern Mexico remain scarce, particularly at the event scale, where logistical and technical constraints often limit long-term monitoring. Addressing this gap is particularly important for understanding how rainfall variability and forest management practices interact to influence runoff generation and water yield in these ecosystems. Beyond quantifying runoff variations, this study seeks to elucidate the hydrological mechanisms—particularly those inferred from canopy interception patterns, rainfall intensity, and antecedent moisture conditions—that control runoff generation in semi-dry forest ecosystems. Building upon previous research conducted in the same watershed [

34,

35], which characterized soil moisture and infiltration dynamics under natural forest conditions, the present study expands this ecohydrological framework by directly quantifying event-based runoff responses following canopy thinning.

Using a Before–After–Control–Impact (BACI) design and event-based hydrological monitoring, this study provides a process-oriented framework to evaluate how canopy thinning modifies runoff generation under natural rainfall variability.

Building upon this context, the present study investigates the effects of varying canopy thinning intensities on event-based runoff generation in semi-dry forest ecosystems, while empirically exploring the hydrological mechanisms linked to rainfall characteristics and canopy structure. The outcomes are expected to contribute to a process-oriented understanding of forest–water interactions and to guide adaptive management strategies aimed at improving water yield and hydrological resilience in the dry forest catchments of northern Mexico, where event-scale observations are still limited.

2. Materials and Methods

This study evaluated how reductions in forest canopy cover influence event-based surface runoff in semiarid MC. Hydrological monitoring was conducted during 2018, under closed canopy cover conditions, and during 2019, after applying thinning treatments that reduced canopy cover to approximately 20% and 60%. These contrasting conditions provided the basis for a BACI experimental design to identify runoff responses to canopy-cover modification.

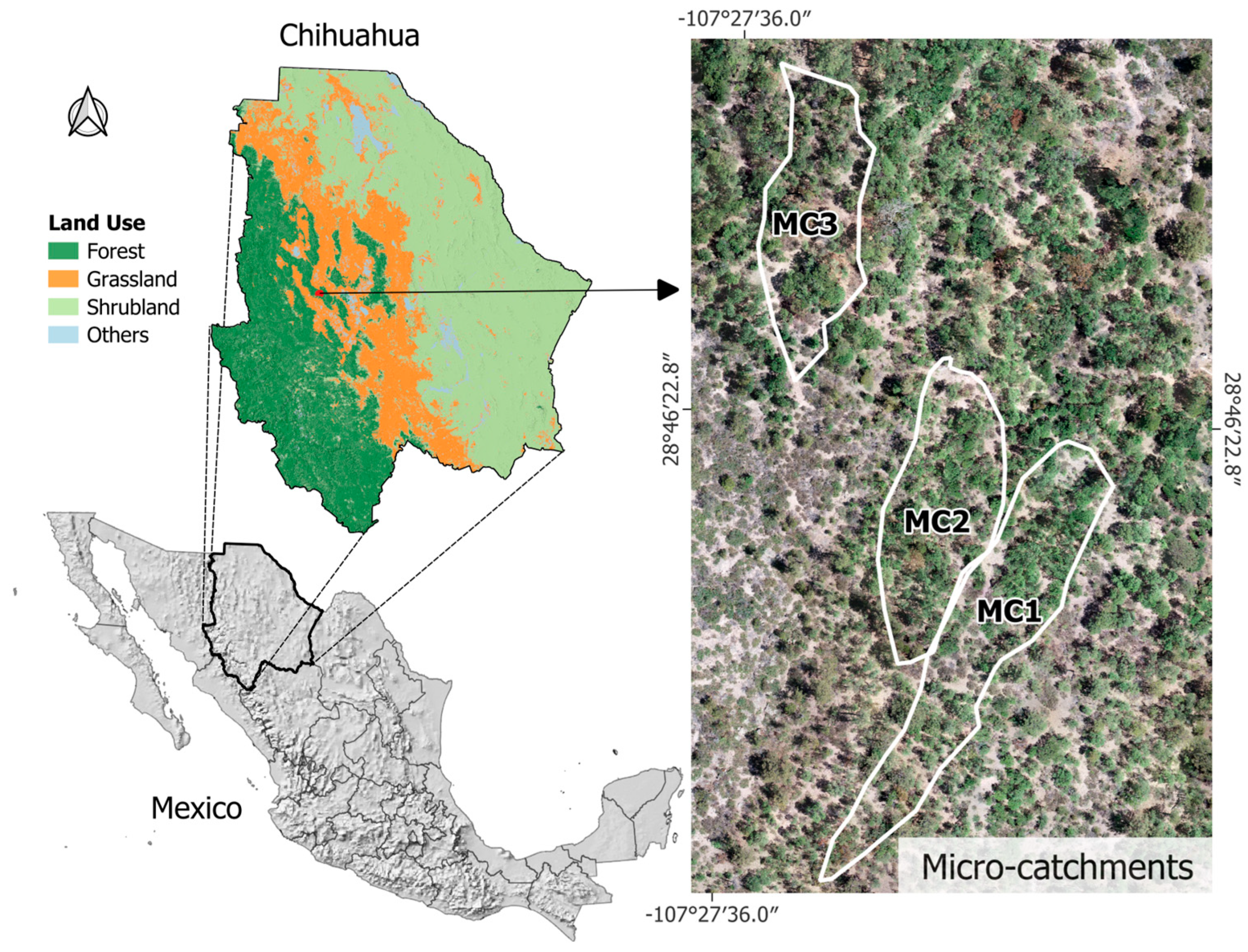

The study was conducted in an oak–pine forest at the Teseachi Ranch, a property of the Autonomous University of Chihuahua, located in the Sierra Madre Occidental of northwestern Chihuahua, Mexico (

Figure 1). The regional climate is classified as semi-dry (BS1kw) according to the Köppen system, with a mean annual temperature of 14.8 °C and an average annual precipitation of 494 mm, approximately 80% of which occurs between June and October [

36].

The overstory is dominated by mixed oak–pine stands, primarily

Quercus hypoleucoides A. Camus,

Quercus grisea Liebmann, and

Pinus engelmannii Carrière, typically occurring between 1400 and 2600 m a.s.l. in the Sierra Madre Occidental [

27,

28,

36,

37]. In the study area, stands are approximately 70 years old and have been protected from logging, grazing, and other major disturbances since 1990, being used exclusively for research and educational purposes.

Soils are classified as Haplic Phaeozems developed from igneous parent material, with loam–clay textures and moderate depth [

38]. These soils, together with the semi-dry climate, support a forest mosaic that is representative of the oak–pine ecosystems of northern Mexico and provide suitable conditions for evaluating the hydrological effects of forest thinning on surface runoff (

Figure 1).

2.1. Characterization of the MC

In 2018, three MC with areas of 0.27, 0.20, and 0.19 ha were selected and designated as MC1, MC2, and MC3, respectively (

Figure 1). All were located within the same oak–pine stand and exhibited high pre-treatment canopy cover (>90%). The selection criteria focused on identifying MC with comparable physiographic, edaphic, and structural characteristics to ensure that canopy cover would be the primary contrasting factor among treatments.

Although runoff generation is influenced by interacting drivers including climate, topography, soil properties, vegetation structure, and management history; the experimental setup was intentionally designed to minimize variability in these factors across the three units. The MC were therefore selected within a restricted physiographic zone of the watershed, characterized by similar slope gradients, aspect, elevation, soil type, and forest composition. Previous studies conducted in the same MC provided a detailed hydrological and edaphic baseline [

34,

35], confirming the homogeneity of environmental conditions prior to treatment implementation.

This controlled selection of MC forms the foundation of the BACI approach used in this study, as it reduces the confounding influence of spatial heterogeneity and strengthens the interpretation of canopy-cover effects on event-scale runoff generation.

2.2. Baseline Conditions of the Study

Topographic, climatic, and soil variables listed in

Table 1 were obtained following the standardized field and analytical procedures described by Rascón-Ramos et al. (2021, 2022) [

34,

35]. Elevation, slope, and aspect for each MC were derived from a 10 m resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) provided by INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, Mexico) and subsequently verified in the field using a Garmin eTrex 20× GPS unit (Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA) and a Suunto PM-5/360 PC clinometer (Suunto Oy Co. Ltd., Vantaa, Finland) to ensure topographic accuracy. Precipitation was continuously recorded using two tipping-bucket rain gauges (RainWise Inc., Bar Harbor, ME, USA) equipped with HOBO event loggers. Rainfall data were processed using the Rainfall Intensity Summarization Tool (RIST v3.94) to derive event-scale metrics, including total rainfall, event duration, and maximum 30-min rainfall intensity. These variables were used to characterize rainfall forcing during both baseline and post-treatment periods.

Soil moisture was monitored at a depth of 20 cm in both under-canopy and inter-canopy positions using calibrated WaterScout SM100 sensors connected to WatchDog Series 1000 data-loggers (Spectrum Technologies, Inc., Aurora, IL, USA), which recorded volumetric water content at 30-min intervals. Additionally, soil physical properties—including bulk density, porosity, and infiltration rate—were measured at representative locations within each MC to verify that edaphic conditions were comparable among treatments [

35]. Meanwhile, vegetation structure, including tree density, basal area, and canopy cover, was assessed through a complete tree inventory in which diameter at breast height, total height, and crown diameter were measured for all individual trees. These measurements were subsequently used to geometrically derive basal area and canopy cover estimates [

34,

35].

The baseline assessment confirmed that the three MC exhibited homogeneous physiographic, soil, and vegetation characteristics, including similar slopes, soil texture (loam–clay Haplic Phaeozems), and pre-thinning canopy cover (90–110%). One-way ANOVA (

p > 0.05) revealed no significant differences for any baseline variable (

Table 1). This environmental homogeneity supports the internal validity of the BACI design by ensuring that canopy-cover reduction was the primary contrasting factor influencing event-scale runoff responses.

Surface roughness was quantified using the chain method and expressed as a dimensionless index, calculated as the ratio between the original chain length and its horizontal projection on the soil surface [

35].

2.3. Thinning Application

Thinning treatments were implemented at the beginning of the 2019 rainy season to generate three contrasting canopy-cover conditions while maintaining the environmental homogeneity previously established during the 2018 baseline year. MC1 remained unthinned (0% reduction), whereas canopy cover was reduced by 80% in MC2 and by 40% in MC3 (

Table 2). Tree density therefore decreased proportionally to the intended canopy reduction, while the spatial layout of the remaining trees was preserved to avoid altering stand structure beyond the prescribed treatment intensity.

All thinning operations were carried out manually using chainsaws, and felled trees were extracted with animal traction to prevent soil compaction or mechanical disturbance. Post-treatment evaluations showed no significant changes in soil bulk density or infiltration rate (

p > 0.05) [

35], confirming that the thinning procedure did not modify key soil physical properties.

2.4. Experimental Structure Design

The experiment followed a Before–After–Control–Impact (BACI) design to evaluate the hydrological effects of canopy-cover reduction under field conditions. In this framework, each MC functions as an independent hydrological unit with continuous pre- and post-treatment observations. The BACI approach enhances internal validity by using pre-treatment conditions as the reference state, thereby allowing treatment effects to be distinguished from natural temporal variability such as interannual differences in rainfall patterns. This design is widely applied in paired and multi-catchment hydrological studies where full spatial replication is logistically unfeasible [

4,

11,

12].

The BACI framework was selected because it allows distinguishing treatment effects from natural interannual variability even when spatial replication is limited. By using each MC as its own temporal control and comparing the relative changes between treated and untreated units, the design isolates canopy-cover effects while minimizing the influence of spatial heterogeneity.

Although only one MC was assigned to each thinning level (0%, 80%, and 40%), spatial comparability was maximized by selecting hydrologically independent units located on adjacent, parallel slopes with similar topography, soil characteristics, vegetation structure, and management history. This controlled spatial configuration ensured that pre-treatment environmental conditions were effectively equivalent across units, allowing canopy-cover reduction to act as the primary factor expected to influence differences in post-treatment runoff responses.

Temporal replication was achieved through event-based monitoring over two consecutive rainy seasons (2018–2019). Each rainfall–runoff event constitutes an independent observation in the BACI framework, allowing the analysis to capture the frequency, magnitude, and variability of hydrological responses to thinning. This event-scale temporal replication increases statistical power despite limited spatial replication and aligns with standard applications of BACI designs in forest hydrology.

2.5. Rainfall Monitoring

Two tipping-bucket rain gauges (203 mm diameter, RainWise Inc., Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were installed in the study area to measure rainfall. Both gauges were mounted at 1 m above ground level in open areas without canopy obstruction. The first gauge was placed 30 m north of MC 1 and 2, and the second was installed to the south, between MC2 and MC3. Each gauge had a resolution of 0.25 mm per record and was equipped with a HOBO event logger, which was periodically downloaded using HOBOWare Pro software (Onset Computer Corporation, 2018, Lincoln, NE, USA) Rainfall data were analyzed using RIST (Rainfall Intensity Summarization Tool) version 3.94 [

39]. Rainfall events were separated by intervals of at least 6 h with less than 1.27 mm of precipitation. For each rainfall event, the following variables were determined: start and end time, total precipitation, duration, and maximum 30-min rainfall intensity.

In this study, individual rainfall events were defined as periods of continuous precipitation separated by at least 6 h with less than 1.27 mm of rainfall. This criterion corresponds to the standard storm definition used in hydrological and erosion modeling, particularly within the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation [

40], and is implemented as the default event-separation threshold in the USDA-ARS Rainfall Intensity Summarization Tool [

39]. Similar thresholds have been widely applied in ecohydrological studies in semi-arid environments [

11,

41]. In the semi-dry oak–pine forests of northern Mexico, this definition is hydrologically consistent with previous findings: soils exhibit very high infiltration rates (≈146 mm h

−1); small rainfall events (<10 mm) do not appreciably modify soil moisture [

34,

35], and runoff generation is limited to relatively large, high-intensity storms (rainfall depth > 20–30 mm or I

30 > 25–30 mm h

−1 [

34]. Furthermore, soil moisture typically returns to near pre-event values within about 24 h due to rapid drying typical of semi-arid forest soils [

35]. Under these hydrological conditions, rainfall amounts <1.27 mm accumulated over 6 h are functionally negligible and do not reset antecedent moisture conditions. The 6 h, 1.27 mm storm-separation threshold therefore avoids artificially splitting single convective storms while ensuring statistical independence among distinct rainfall events.

2.6. Surface Runoff Monitoring

Runoff was measured following the procedure described by Pinson et al. (2004) [

42]. At the natural drainage point of each plot, a small micro-dam was constructed to direct runoff into a PVC pipe leading to a container (

Figure 2a). Three aluminum containers (55 cm in diameter and 112 cm in height) were installed per plot. Each container had a crown with 15 triangular notches that divided overflow water upon filling. The outflow from one notch of the first container was directed into a second container, and from there into a third (

Figure 2b). The runoff volume for each rainfall event was calculated by summing the water volume collected in the containers and the overflow, using the following equation:

where

E = runoff volume produced during a rainfall event in each plot.

VC = water volume collected in containers 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

The runoff collection system operates as a multi-stage flow divider. Runoff generated at the outlet of each micro-catchment is first collected in container 1. Once container 1 is filled, overflow water is evenly divided through 15 triangular notches. Only one of these sub-divisions is directed to container 2, while the remaining fractions are discarded. The same sub-division principle applies between containers 2 and 3. Therefore, the measured volumes in containers 2 and 3 represent 1/15 and 1/225 of the total overflow volume, respectively. Equation (1) reconstructs the total runoff volume by accounting for these successive flow divisions, following the methodology described by Pinson et al. (2004) [

42].

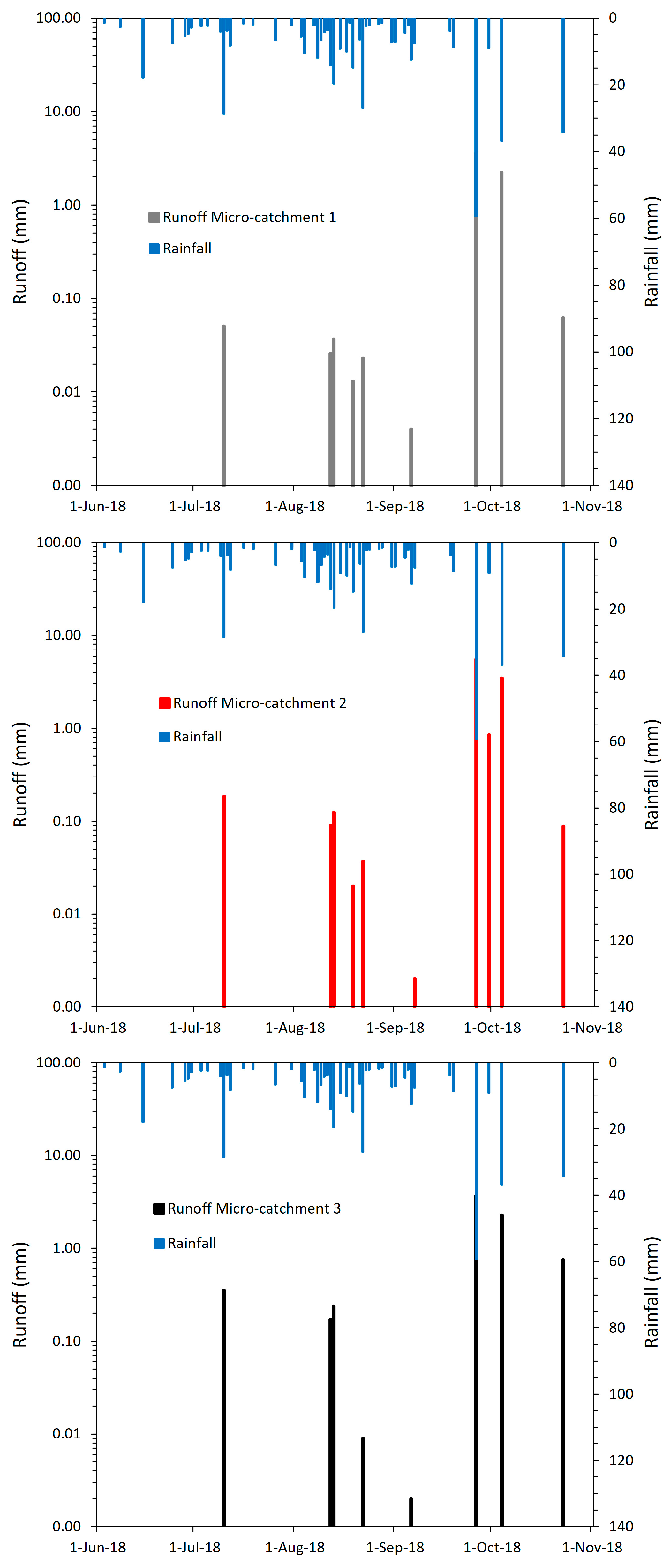

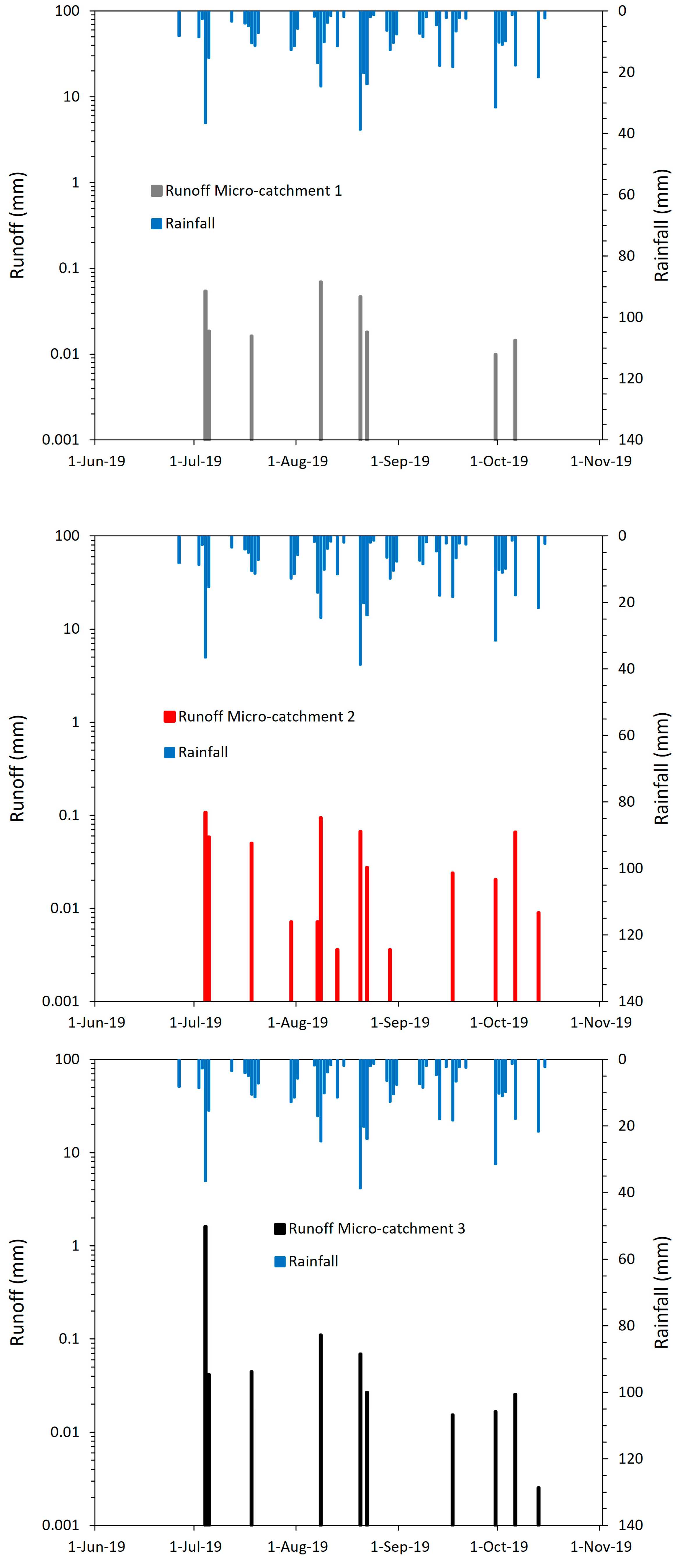

The statistical modeling was conducted using all runoff-producing storm events detected during the 2018–2019 monitoring period. A total of 51 and 49 rainfall events were recorded in 2018 and 2019, respectively, of which only 11 and 14 storms generated measurable runoff across the MC. Although this number of runoff events is limited, such sampling intensity is fully consistent with the threshold-driven hydrology of semi-arid and semi-dry forests. Previous studies in the same watershed have shown that only ~10% of rainfall events exceed the depth and intensity thresholds required to activate runoff [

35], and similarly low frequencies of hydrologically effective storms have been reported in other arid and semi-arid catchments [

41,

43]. Accordingly, event-scale analyses in such environments commonly rely on small sample sizes due to the intrinsic rarity of runoff responses.

A descriptive analysis of rainfall and runoff events was conducted for the 2018 (pre-treatment) and 2019 (post-treatment) rainy seasons. Event-based precipitation and runoff were graphically examined to identify temporal patterns and preliminary contrasts among MC. These data served as inputs for the statistical modeling described in

Section 2.7.

2.7. Statistical Modeling of Precipitation and Runoff

Prior to model selection, the distributions of precipitation (pp) and event-based runoff (E) were evaluated using Shapiro–Wilk tests and graphical diagnostics, which indicated clear deviations from normality. Given their strictly positive, right-skewed nature, precipitation and event runoff values were better characterized by a Weibull distribution. Therefore, all subsequent analyses were conducted using a Weibull model fitted by Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), without assuming normality.

Event-based runoff (E) was modeled using a two-parameter Weibull distribution, suitable for positively skewed hydrological variables characterized by frequent small values and occasional extremes. The Weibull distribution has shape (k) and scale (λ) parameters, with density and expected value:

A log-link was used for the scale parameter to ensure positivity and interpretability. The shape parameter was expressed as k = exp(log k), following standard parametrization.

2.7.1. Response Variables and Derived Metrics

Zero-runoff events were retained in descriptive analyses but excluded from Weibull modeling because the distribution is defined for positive values. Very small positive values (<1 mm) were kept as observed, as they fall within the valid range of the Weibull density.

Response Variables

Two hydrological response variables were considered: (i) event precipitation (pp), used as the forcing variable in the precipitation–runoff relationship, and (ii) surface runoff (R), defined as total event runoff volume (L) normalized by catchment area (L ha−1).

Derived Antecedent Moisture Metric (API)

Antecedent moisture conditions were quantified using the Antecedent Precipitation Index (API), following Dunne and Leopold (1978) [

44]:

with recession constant k = 0.85, where API(t) is the antecedent precipitation index at time t, P(t) is precipitation at time t, and API(t − 1) is the antecedent precipitation index at the previous time step.

The recession constant k = 0.85 is consistent with published values for semi-arid forest soils with moderate infiltration and rapid dry-down rates (Dunne and Leopold, 1978) [

44]. Although the API was not included as a predictor in the statistical models, it was calculated to support the hydrological interpretation of event-scale runoff responses and is referenced in the discussion of results.

2.7.2. BACI Treatment Structure

The BACI design was implemented by defining treatment groups based on canopy-cover conditions. In 2018 (BEFORE), all MC had ~100% canopy cover (BASE). In 2019 (AFTER), canopy was maintained at ~100% in the control and reduced to ~20% and ~60% in the treatment units.

2.7.3. Model Specification

Three alternative models were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation:

Model M1 (full interactions):

Model M0 (common precipitation slope):

For model MYEAR, indicator variables were used to represent year and canopy-cover treatments. The notation I(⋅) denotes an indicator function equal to 1 when the specified condition is met and 0 otherwise. The subscript i denotes the i-th rainfall–runoff event. Here, pp denotes the event-based precipitation depth (mm), ccov denotes canopy cover (%), and y2 represents the year indicator corresponding to post-thinning conditions (2019). The coefficients βpp, βy2, β20, and β60 represent the main effects of precipitation, year (2019), and canopy-cover treatments of 20% and 60%, respectively, relative to the baseline condition (2018, 100% canopy cover).

In Equations (5)–(7), runoff represents the event-based surface runoff (mm). Precipitation (pp) corresponds to event-based rainfall depth (mm). The variable “year” is a binary indicator distinguishing pre-thinning (2018, baseline) and post-thinning conditions (2019). Group indicators correspond to categorical variables representing canopy-cover treatments (100%, 60%, and 20%), with the 100% canopy cover used as the reference category. Model parameters β0, β1, …, β7 are regression coefficients estimated by Maximum Likelihood Estimation. The intercept β0 represents the expected runoff (in log scale) under baseline conditions, while the remaining coefficients quantify the relative effects of precipitation, year, and canopy-cover treatments on runoff.

Interpretation of components:

In the generalized Weibull models, BACI structure is incorporated through the group indicators (g2, g3, g4), which represent post-treatment canopy-cover levels relative to the 2018 baseline. Under the log-link, coefficients represent multiplicative effects on mean runoff, enabling interpretation of BACI contrasts as ratios of ratios.

β0 represents baseline runoff (pre-treatment, ~100% canopy cover). β1 represents the effect of precipitation. g2, g3, and g4 denote canopy conditions (~100%, 20%, 60%), with the pre-treatment year as reference. Interaction terms capture differences in precipitation–runoff relationships across canopy levels. The log-link ensures positivity and multiplicative interpretation.

Non-significant coefficients in M1 were interpreted as absence of statistical support for treatment effects. Following standard Generalized Linear Model (GLM) practice, non-significant parameters were retained in the model structure but not used to infer treatment differences.

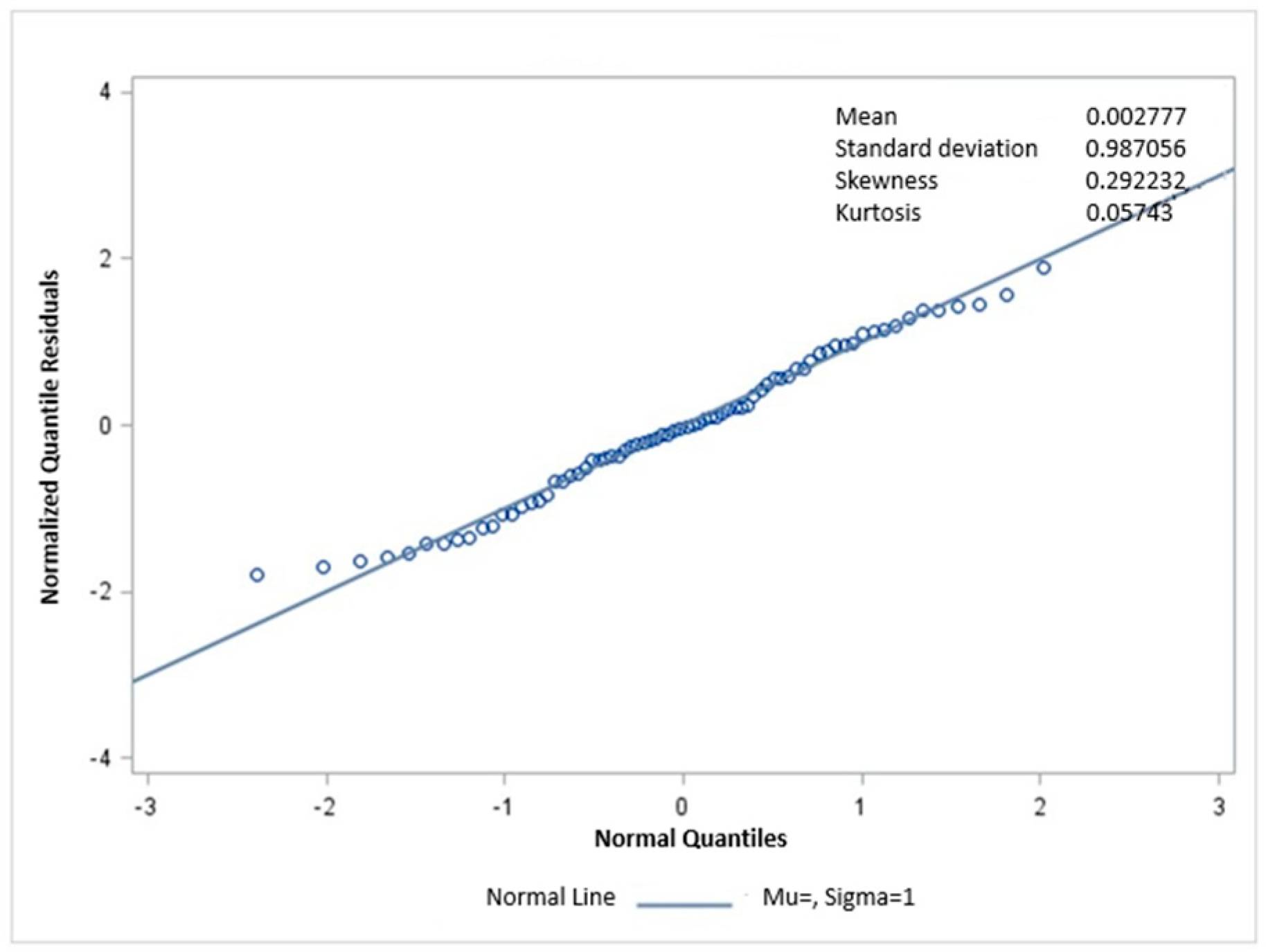

2.7.4. Model Comparison and Diagnostics

Models were compared using log-likelihood, AIC, AICc, and BIC. ΔAICc and Akaike weights quantified relative support. Diagnostics included PIT values, normalized quantile residuals, Q–Q plots, and Shapiro–Wilk tests, confirming adequate calibration of the selected Weibull model.

Model selection was based on information-theoretic criteria, including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), its small-sample correction (AICc), and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). These criteria evaluate the trade-off between goodness of fit and model complexity, allowing identification of the most parsimonious model. Differences in AICc (ΔAICc) were used to compare candidate models, with lower values indicating stronger empirical support.

Model assumptions were evaluated using diagnostic tools, including quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots and the Shapiro–Wilk test. Q–Q plots were used to visually assess whether model residuals followed the assumed theoretical distribution, while the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to formally test residual normality.

Statistical uncertainty associated with the Weibull parameters was explicitly considered, acknowledging that both the shape and scale parameters exhibit sampling variability, particularly for moderate sample sizes typical of event-based runoff. Confidence intervals were obtained for the parameter estimates, and the sensitivity of predicted runoff to such uncertainty was evaluated following approaches recommended for hydrological applications of Weibull-type models (e.g., Koutsoyiannis, 2019 [

45]; Zheng et al. 2023 [

46]).

All statistical analyses and GLM–Weibull model fits were performed in SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) [

47].

4. Discussion

The predominance of extreme rainfall events in controlling surface runoff reflects the threshold behavior typical of semi-arid ecosystems. Similar to findings in Mediterranean and temperate forests [

4,

11,

48], only high-intensity storms exceeded the infiltration capacity and produced measurable runoff, whereas moderate events were mostly absorbed by the upper soil layers. Our previous studies in the same watershed [

34,

35] confirmed that rainfall intensities above approximately 25 mm·h

−1 were necessary to activate surface flow, with antecedent precipitation strongly conditioning the magnitude of the response. Consistent with those findings, the current dataset revealed that during the 2018 hydrological year, an extreme storm event generated a peak runoff nearly five times greater than the average of subsequent years, despite similar annual precipitation totals. This emphasizes that runoff generation in these forests appears to depend not only on cumulative rainfall but also on the occurrence and timing of extreme events relative to antecedent soil moisture. Although this pattern is consistent with previous studies in semi-arid forests [

4,

11,

23], the limited number of runoff-producing events in our dataset, particularly the disproportionate influence of a single extreme storm in 2018 warrants a cautious interpretation of the strength of this relationship. Such threshold-controlled behavior might explain the episodic and spatially concentrated nature of runoff generation, which remains largely independent of annual precipitation amounts. From a management perspective, these findings highlight the importance of considering both rainfall intensity and antecedent soil moisture when designing forest interventions aimed at enhancing water yield in semi-dry ecosystems [

11,

48], as low-intensity events contribute minimally to surface flow.

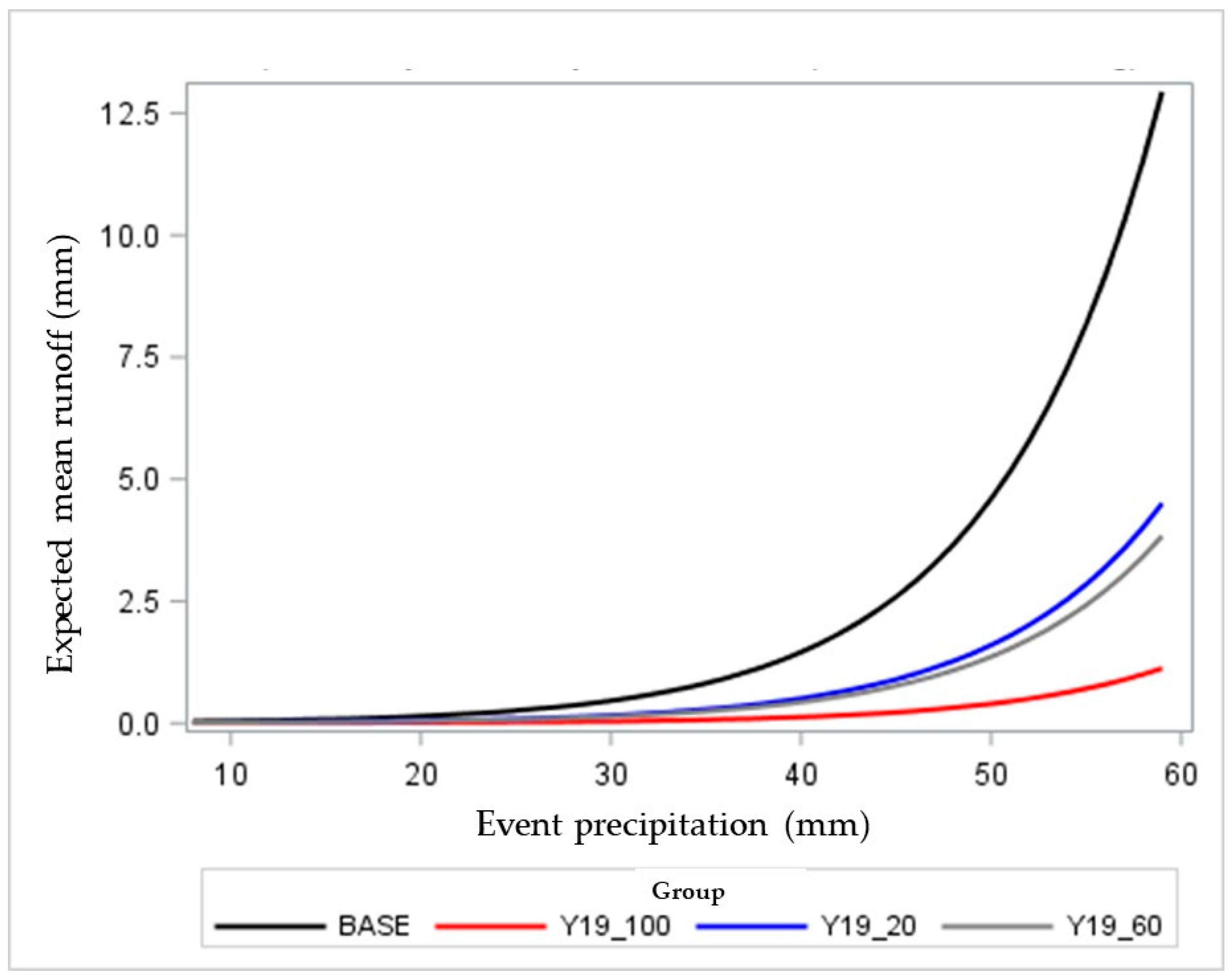

The comparison of alternative Weibull models further supports this interpretation. Interaction models (M1 and MYEAR) did not provide additional explanatory value, indicating that thinning did not fundamentally modify the functional form of the precipitation–runoff relationship. Instead, differences among treatments were adequately represented as shifts in baseline runoff, consistent with a canopy-driven modification of initial conditions rather than a change in rainfall sensitivity.

Differences in canopy structure among thinning treatments were key to explaining the observed hydrological responses. According to our results, thinning effectively reduced canopy interception and attenuated surface runoff, suggesting that a decrease in canopy density allows a greater fraction of rainfall to reach the forest floor. This reduction in interception appears to facilitate the generation of runoff during high-magnitude rainfall events, as more water bypasses the canopy and rapidly saturates the upper soil layers. These findings confirm the patterns reported in our previous study [

35], where thinning enhanced soil moisture availability by increasing throughfall and reducing evaporative losses. In the present work, the moderate thinning treatment (approximately 60% canopy cover) exhibited hydrological responses similar to those observed under more intensive thinning, indicating that beyond a certain threshold, additional canopy removal produces limited additional hydrological change. This behavior is consistent with observations of diverse authors [

4,

6,

11,

48], who found that partial canopy reduction optimizes infiltration and runoff regulation by balancing rainfall redistribution and soil protection. Overall, these results suggest that maintaining moderate canopy cover supports a stable hydrological regime while avoiding the potential negative effects of excessive thinning on soil structure and erosion.

The BACI analysis revealed that thinning increased runoff response moderately but not in direct proportion to the reduction in canopy cover, indicating a nonlinear hydrological behavior. Such nonlinearity has been reported in forested catchments where soil-moisture–rainfall relationships follow exponential rather than linear patterns [

4,

35,

48]. The Weibull model applied in this study supports this interpretation, showing that each additional millimeter of rainfall increased expected runoff by approximately 12%. This pattern suggests that beyond certain rainfall thresholds, the catchment’s hydrological response becomes increasingly sensitive to additional rainfall inputs, reflecting a saturation-driven behavior rather than a gradual or proportional increase in runoff. Although infiltration was not directly measured, these results are consistent with threshold-type runoff generation observed in semi-arid and Mediterranean forest ecosystems, where antecedent soil moisture, partial saturation, and surface connectivity govern the transition from infiltration-dominated to runoff-dominated conditions [

4,

11,

49].

Although both thinning treatments showed higher runoff ratios than the closed-canopy control, the effect was statistically robust only for the 60% canopy treatment, while the 20% treatment exhibited a marginal BACI contrast with wide confidence intervals. These patterns reflect both the reduced magnitude of 2019 runoff events and the disproportionate influence of the single 59 mm storm recorded in the baseline year, which amplifies absolute contrasts between years.

Mechanistically, moderate canopy openings create heterogeneity in throughfall distribution, leading to localized saturation zones and intermittent connectivity between surface and subsurface flows. Similar processes were identified by Dung et al. (2012) [

4] in forests under selective thinning. These threshold-driven behaviors reinforce the importance of adaptive forest management strategies that avoid excessive canopy removal, which could destabilize soil-moisture storage and increase erosion risk [

48,

50].

The results showed that moderate canopy thinning (approximately 60% cover) reduced surface runoff by about 20–25% compared with the control plots. The BACI analysis further indicated that each additional millimeter of rainfall increased expected runoff by roughly 12%, supporting a nonlinear hydrological response dominated by high-intensity storms. In particular, an extreme rainfall event in 2018 produced a runoff peak nearly five times greater than the average of subsequent years, underscoring the dominant influence of storm magnitude and antecedent moisture on catchment behavior. These quantitative results have direct implications for water harvesting and watershed management in semi-dry forests, where adaptive thinning can enhance soil-water recharge and improve water yield without compromising ecosystem resilience.

To strengthen interpretative clarity, a distinction is made between patterns that emerge directly from the empirical dataset and hydrological mechanisms inferred from previous research. The reduced magnitude of runoff in 2019, the treatment-specific differences in runoff ratios, and the disproportionate influence of high-magnitude rainfall events arise directly from the event-scale observations and Weibull-based modeling. In contrast, interpretations related to canopy interception, threshold-type activation of surface runoff, and changes in hydrological connectivity are presented as plausible mechanisms supported by prior studies in semi-arid forest environments [

11,

18,

19,

22,

23]. These mechanisms offer process-based explanations that complement, but do not replace, the directly observed event-scale responses documented in this study.

It is important to note that these findings refer specifically to the semi-dry forests studied under the relatively homogeneous conditions of the three experimental MC. However, dry forests across the region are characterized by considerable structural and topographic complexity, suggesting that additional research is required to evaluate the influence of other variables on runoff generation, either independently or through multivariate approaches. By integrating the event-based runoff dynamics with the soil-moisture responses [

34,

35], the present study provides one of the few empirical baselines available for designing forest-management strategies in water-limited environments of northern Mexico. While this study has inherent limitations, it offers robust and process-oriented evidence that advances our understanding of ecohydrological dynamics in semi-dry forests.

The temporal scope limited to two years after canopy thinning and lacking subsequent data for 2020–2025 restricts the assessment of long-term hydrological adjustments and vegetation recovery. Likewise, the small and relatively homogeneous experimental MC constrain the extrapolation of results to more heterogeneous landscapes. Nevertheless, the event-based monitoring design employed here, with runoff measurements collected for each rainfall event at high temporal resolution, provides a level of empirical detail for the semi-arid forest environments. Although variables such as canopy interception, litter dynamics, and root structure were not directly quantified, the consistent hydrological patterns observed across treatments and years demonstrate the internal reliability of the dataset and support the mechanistic interpretations proposed.

Furthermore, the empirical models applied (BACI and Weibull) adequately captured nonlinear responses to rainfall, revealing thresholds and sensitivities consistent with field observations. Collecting such detailed event-scale data under challenging field conditions represents a substantial scientific contribution, offering one baseline references for understanding how rainfall characteristics and forest structure jointly regulate runoff generation in the dry forests of northern Mexico.

5. Conclusions

Runoff generation in semi-arid oak–pine forests appears to be governed primarily by the occurrence and intensity of extreme rainfall events rather than by annual precipitation totals, confirming the episodic and non-linear nature of hydrological responses in these ecosystems.

Canopy reduction modified runoff dynamics, with thinning treatments at 20% and 60% canopy cover maintaining relatively higher proportions of runoff than the 100% canopy control, despite overall reductions in 2019 relative to the 2018 baseline.

The BACI analysis suggested that thinned catchments attenuated runoff less severely than the control, indicating a moderate positive influence of canopy reduction, although the 20% treatment exhibited only marginal statistical significance.

Weibull-based modeling effectively represented the frequency and magnitude of runoff events, revealing an average 12% increase in expected runoff for each additional millimeter of precipitation, consistent with a threshold-type response to rainfall intensity.

The interaction among canopy cover, antecedent moisture, and rainfall magnitude appears to play a decisive role in regulating the hydrological balance of semi-dry forests, underscoring that forest management strategies should consider optimal canopy thresholds to sustain water yield while maintaining long-term ecosystem resilience.