Abstract

Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) have arisen as a potential alternative to lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) as a result of the abundant availability of sodium resources at low production costs, making them in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for affordable and clean energy (Goal 7). The current review intends to comprehensively analyse the various modification techniques deployed to improve the performance of cathode materials for SIBs, including element doping, surface coating, and morphological control. These techniques have demonstrated prominent improvements in electrochemical properties, such as specific capacity, cycling stability, and overall efficiency. The findings indicate that element doping can optimise electronic and ionic conductivity, while surface coatings can enhance stability in addition to mitigating side reactions throughout cycling. Furthermore, morphological control is an intricate technique to facilitate efficient ion diffusion and boost the use of active materials. Statistically, the Cr-doped NaV1−xCrxPO4F achieves a reversible capacity of 83.3 mAh/g with a charge–discharge performance of 90.3%. The sodium iron–nickel hexacyanoferrate presents a discharge capacity of 106 mAh/g and a Coulombic efficiency of 97%, with 96% capacity retention over 100 cycles. Furthermore, the zero-strain cathode Na4Fe7(PO4)6 maintains about 100% capacity retention after 1000 cycles, with only a 0.24% change in unit-cell volume throughout sodiation/desodiation. Notwithstanding these merits, this review ascertains the importance of ongoing research to resolve the associated challenges and unlock the full potential of SIB technology, paving the way for sustainable and efficient energy storage solutions that would aid the conversion into greener energy systems.

1. Introduction

SIBs appeared as a capable alternative to LIBs as a result of the plentiful accessibility of sodium resources and their lower cost. The SIBs can attain inspiring specific energies of about 600 Wh/kg while working between 2.7 and 3.2 V of potential and 180–220 mAh/g of specific capacity [1]. Interestingly, this enables the introduction of SIB as a primitive energy storage technology, which is mainly in line with the concept of sustainability. This is because SIBs can offer a practical solution to the limitations of LIBs, including the scarcity and the passive impacts of lithium extraction [2,3]. Accordingly, the SIB continues to attract the attention of experts who invented several cathode materials, including the transition metal oxides, polyanionic compounds, and Prussian blue analogues. These novel materials are characterised by a high electrochemical performance and stability. However, the creation of effective cathode materials that can efficiently hold sodium ions is essential to the realisation of SIB technology. Through structural and compositional changes, cathode materials such as phosphates, vanadium oxides, and Prussian blue analogues (PBAs) present promising ways to improve electrochemical performance [4,5].

Structural changes are one of the main methods that are widely used to improve SIB cathode performance. Vanadium-based materials, for example, have layered structures that readily intercalate sodium ions. Researchers have significantly improved sodium storage capacity and material stability by optimising the inter-layer spacing through synthesis techniques like hydrothermal treatments or controlled precipitation [5]. Structures with fewer defects and vacancies have been shown to perform better electrochemically, which lessens structural collapses during the sodium insertion and extraction procedures [4].

The electrochemical properties of cathode materials are significantly influenced by their morphology. By reducing the diffusion path for sodium ions, nanosizing techniques have demonstrated encouraging results in enhancing ionic and electronic conductivity. For example, rate capabilities can be greatly improved by PBAs synthesised into nanosized forms. Huang et al. [6] showed that materials with high capacity and cycling stability can be produced by reducing particle size while maintaining a favourable morphology. Better contact with electrolytes is made possible by such design enhancements, which speed up ion transport during charge and discharge cycles.

An efficient way to improve the electrical conductivity and general performance of SIB cathodes is to hybridise cathode materials with conductive matrices like carbon or graphene. Interfaces that develop between the active material and the conducting matrix improve ion transfer rates and lessen the effects of structural changes that occur during cycling. Chen et al. [7] demonstrated that by incorporating carbon layers that enhance electronic transport and lower resistance, composites such as Na3V2(PO4)3@C can achieve exceptional cycling stability and specific capacities. Better mechanical support is also made possible by this method, which is essential during the volume changes brought on by sodium insertion.

Another enhancement approach that has presented great prospective for upgrading the electrochemical properties of cathode materials is doping. Researchers have enhanced structural stability and altered the redox potentials by adding different transition metals. For example, doping vanadium-based materials with ions like magnesium or chromium improves cycling performance and rate capability by stabilising the crystal structure against phase changes during sodium extraction [5]. Besides rising capacity, this technique assures that the cathode’s structural integrity is maintained over several cycling cycles. In this aspect, the environmental and economic parameters should be considered for SIB technology to be sustainable. The development of inexpensive, readily available materials, such as vanadium oxides and sodium-based PBAs, delivers methods to reduce the environmental effects of energy storage technologies. The resource restrictions and geopolitical unrest related to lithium extraction can be reduced by converting to sodium-ion technology [8]. Weighing the advantages of these materials against their manufacturing processes, lifecycle impacts, and long-term viability for widespread applications becomes crucial as modification strategies continue to improve the performance of SIBs.

The latest developments and future prospects of SIB cathode materials were critically revised by several researchers in the open literature. For the purpose of better perceiving the characteristics of different iron-based cathode materials and enhancing their electrochemical performance, Wang et al. [9] conducted a thorough investigation. The synthetic features, functional mechanisms, and validation/optimisation of iron-based cathode materials for SIBs, including the polyanionic and oxide compounds, Na-free cathode materials, and Prussian blue compounds, were methodically summarised. The suggested methods for resolving a number of technological obstacles stand in the way of the actual implementation of iron-based cathode materials in SIBs.

To produce high-energy/high-power density SIBs, Li et al. [10] provided a comprehensive assessment of the engineering methodologies and design concepts of polyanion cathodes. Specifically, a number of scientists explained how to develop polyanion cathode materials for improved specific capacity and voltage to increase the energy density. The synthesis of electrode processing, architectural design, and morphological control to upgrade the power density for SIBs was also inspected.

Jun Xiao et al. [11] conducted a review research and concentrated on different techniques to enhance the electrochemical performance of SIBs, in addition to providing a detailed outline of topical enhancements in emerging cathode materials. Layered metal oxides, polyanionic compounds, Prussian blue analogues, and organic materials are among the cathode materials that were methodically analysed as part of the procedure. In order to enhance performance metrics like capacity retention, cycling stability, and rate capability, the review critically assessed structural engineering, elemental doping, and composite formation. Important discoveries showed that there are still obstacles in the way of enhancing the stability and conductivity of cathode materials, despite considerable advancements. In particular, the researchers highlighted how polymer composites and mixed metal oxides can improve electrochemical kinetics and reduce structural degradation, offering insights into potential future paths for SIB research and development.

Chu et al. [12] provided a thorough overview of the developments in high-efficacy cobalt-free cathode materials for improved SIBs, analysed the struggles between structural/electrochemical stability and essential inadequacies of cobalt-free cathode materials, and went into great detail about the methods for creating stable cobalt-free cathode materials by using non-cobalt transition-metal elements and appropriate crystal structures. Their goals were to shed light on the critical factors (such as particle cracks, phase transformation, lattice distortion, crystal defects, morphology, transition-metal migration/dissolution, lattice oxygen oxidation, and the associated impacts of composite structures) which could affect the stability of cobalt-free cathode materials, offer recommendations for further investigation, and increase attention in creating high-efficiency cobalt-free cathode materials.

To improve the initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) and rate performance of both anode and cathode materials in SIBs, Nkongolo Tshamala Aristote et al. [13] reviewed and summarised several approaches. In order to reduce the irreversible consumption of sodium ions during charge/discharge cycles, the review critically assessed developments in material engineering, such as structural alterations, heteroatom doping, and surface coatings. Important results showed that ICE and battery performance are greatly enhanced by using heteroatoms, controlling defects, and optimising carbonisation processes. Notably, certain techniques—like using hard carbon that has been heated to a high temperature and adding dopants of phosphorus and nitrogen—were shown to improve the electrochemical performance, suggesting promising avenues for SIB commercialisation.

The advanced characterisation methods mentioned in polyanion-type cathode materials of SIBs were the major emphasis of Guo et al. [14]. These techniques mostly include those relating to structure, morphology, composition, and in situ/operando methods throughout charge/discharge operations. The progression of different characterisation methods deployed in polyanion-type materials was defined, along with a complete debate of each technique’s detection processes, extent of application, information accessible, and restrictions.

He et al. [15] focused on conversion metal oxides, polyanionic compounds, and Prussian blue analogues to deliver a comprehensive outline of the current developments and challenges linked to cathode materials for SIBs. The researchers deliberated various synthesis and amendment methodologies that can enhance electrochemical performance, utilising a methodical technique to categorise and analyse the performance features of these materials. Significant detections indicated that even though transition metal oxides have considerable specific capabilities, they often exhibit structural instability throughout cycling, while polyanionic compounds have strong stability and a greater energy density, but have concerns with electronic conductivity. Prussian blue compounds ascertain pronounced promise due to their open framework structure, which permits the reversible insertion of sodium ions. Nevertheless, there are still problems with managing water crystallisation and transition metal ion dissolution, which can jeopardise cycling stability.

Referring to the above-mentioned review investigations, it can be said that the commonality of these review papers was not particularly evaluated concrete challenges like stability concerns of SIB cathode materials, in addition to not profoundly covering the contribution of partial substitution and co-doping techniques with elements such as chromium and nickel, and associated structural engineering approaches in upgrading performance metrics. Furthermore, no considerable information was offered for controlled morphological modifications that can alleviate volume changes throughout cycling. Undeniably, the significance of analysing and augmenting the competence of cathode materials for SIBs cannot be overstated. Modifications through superior methodologies, such as element doping, surface coating, and morphological control, indicate an energetic contribution in upgrading the electrochemical properties and overall performance of these materials. For instance, element doping can optimise the electronic and ionic conductivity. Also, the surface coatings can improve the stability and lessen side reactions throughout charge and discharge cycles. An improved ion diffusion can be guaranteed via careful morphological control in addition to enhancing the effective use of the active material. Subsequently, an inclusive examination is conducted in the current review to illuminate and scrutinise the influence of adjustment approaches, including the element doping, surface coating, morphological control, and electrode design on high-efficacy cathode materials for SIBs.

This review is unique due to its methodical examination of three imperative modification strategies that are explicitly associated with improving SIB performance: element doping, surface coating, and morphological control. It comprehensively inspects relevant research that displays how doping with elements such as nickel and chromium can improve ionic and electronic conductivity, critically rising capacity and efficacy. This review signifies the merits of co-doping and partial substitution approaches, which enhance cycling stability and capacity. Remarkably, it signposts how structured morphological adjustments can decrease volume variations throughout cycling, therefore extending operational life. Furthermore, it uses electrolyte additives to resolve manganese dissolution, which aids in preserving stability and capacity. Although admitting the sustained request for research into the long-term effects of doping, surface coating durability, and integrated modification techniques, this review highlights inspiring statistical results, such as the extraordinary reversible capacity and Coulombic competence detected in specific doped materials. This detailed analysis not only makes the rewards of various adjustment techniques clear, but it also opens the door for forthcoming investigation that may advance SIB performance and commercialisation even more. Also, this review judgmentally evaluates the challenges faced by cathode materials and integrates refined characterisation practices for a nuanced perception of performance improvements, making an opportune and indispensable contribution to the search for well-organised and sustainable energy storage solutions in SIB technology. Expectedly, this review would pave the way for future enhancements in SIB technology, in addition to aiding in the enhancement of sustainable and effective energy storage systems.

2. State of the Art: Advanced Strategies for Improved Performance of SIBs

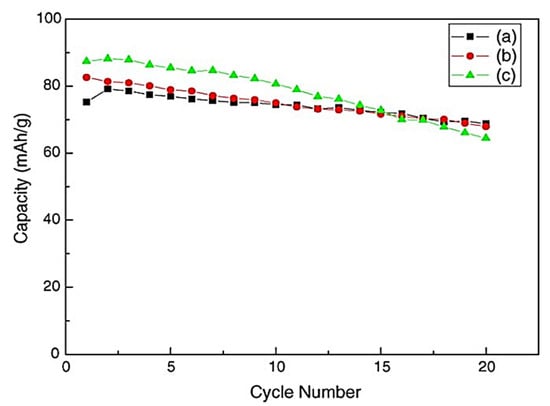

Zhuo et al. [16] prepared cathode/anode materials to create an SIB. To be used as a cathode material in SIBs, Cr-doped NaV1−xCrxPO4F (x = 0, 0.04, 0.08) was created via a high-temperature solid-state process. Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), the cathode materials’ morphologies and structures were described. Crystal structure, cycle performances and charge–discharge curves were used to examine how Cr doping affected the cathode materials’ performance. According to the findings, the as-prepared Cr-doped materials outperform the undoped ones in terms of cycle stability, have an initial reversible capacity of 83.3 mAh/g, and have a first charge–discharge efficacy of almost 90.3%. Furthermore, it was noted that the material’s reversible capacity retention remains at 91.4% in the 20th cycles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Capacity against cycle numbers for Na/NaV1−xCrxPO4F cells using 10 m/g of density and 3.0–4.5 V of voltage range: (a) NaV0.92Cr0.08PO4F; (b) NaV0.96Cr0.04PO4F; (c) NaVPO4F. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [16]. 2025, Mudhar A. Al-Obaidi.

Using an electrochemical technique for Li-rich layered oxides, Jian et al. [17] created Na-rich layered oxides as cathode materials for SIBs. Using 5 mA/g of the current, the materials displayed a high-specific capacity of 234 mAh/g. The material’s energy density (644 Wh/kg) exceeded that of LiFePO4 and LiMn2O4, two common commercial cathodes for LIBs. The Na+ diffusion coefficient, as determined by a kinetic study of Na+ insertion/extraction into/from the Na-rich layered oxide, was around 10−14 cm2/s.

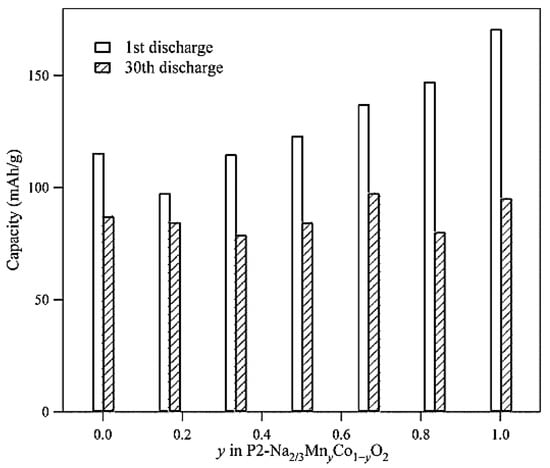

The electrochemical characteristics of P2−Na2/3MnyCo1−yO2 were thoroughly examined by Wang et al. [18]. The traditional solid-state process proved effective in synthesising a number of P2 phases. The P2 compounds in solid solution demonstrated that the transition-metal substitution causes a systematic change in the redox voltage of Co4+/Co3+ and Mn4+/Mn3+. The charge–discharge cycle testing showed that although the cycle stability decreases with growing y, the initial specific capacity rises. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy was used to study the source of the cycle deterioration and showed that the passivating layer at the electrode surface forms most quickly when Co is substituted for Mn. However, after 30 cycles, the cycle stability declines to provide a greater loss of capacity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Capacity against the P2−Na2/3MnyCo1−yO2 using the first and 30th discharge processes. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [18]. 2025, Mudhar A. Al-Obaidi.

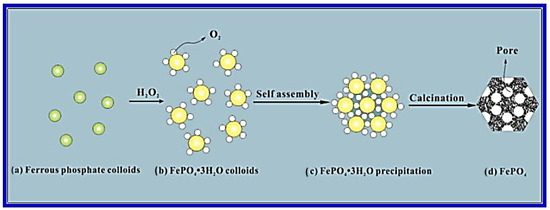

FePO4 nano-spheres were effectively produced by Fang et al. [19] using a straightforward chemically induced precipitation process (Figure 3). The amorphous structure of the nano-spheres is mesoporous. According to electrochemical tests, the FePO4/C electrode has a 44 mAh/g at 1000 mA/g (high-rate capability) for Na-ion storage, consistent cyclability (94% capacity retention ratio over 160 cycles), and 151 mAh/g at 20 mA/g of high initial discharge capacity. The FePO4/C nanocomposite’s unique mesoporous amorphous structure and tight contact with the carbon agenda, which greatly enhanced the electronic and ionic transport and intercalation kinetics of Na ions, are responsible for its exceptional electrochemical performance.

Figure 3.

A representation of the creation method of the mesoporous FePO4 nano-spheres. Adapted with permission from Ref. [19]. 2025, Mudhar A. Al-Obaidi.

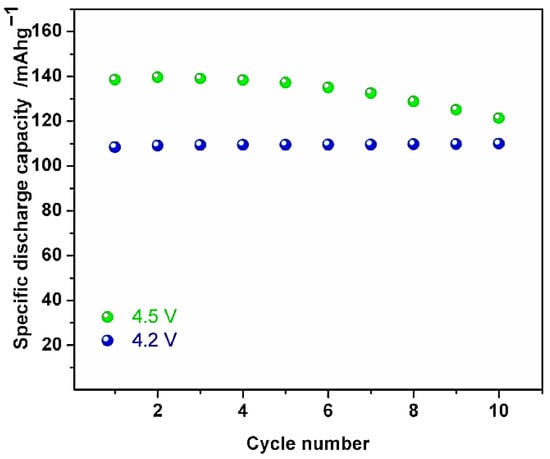

A novel NaxCo2/3Mn2/9Ni1/9O2, sodium-ion intercalation material, was introduced by Doubaji et al. [20]. It was created using a sol–gel process in air and then heated for 12 h at 800 °C. The XRD analysis of its structure exposed that the material crystallised in a P2-type structure (space group P63/mmc). Regarding NaxCo2/3Mn2/9Ni1/9O2’s electrochemical characteristics as a positive electrode, this compound provided 110 mAh/g of the specific capacity when cycled using 4.2 V and 4.5 V of upper cut-off voltages vs. Na+/Na. As seen in Figure 4 and at 4.5 V, the electrodes demonstrate 140 mAh/g of the reversible discharge capacity when the cycle number is between 2.0 and 4.5, as well as strong capacity retention and 99.4% of the Coulombic efficacy.

Figure 4.

Specific discharge capacity against cycle number of Na2/3Co2/3Mn2/9Ni1/9O2 electrodes using 4.2 V and 4.5 V various upper cut-off voltages with 10 cycles of galvanostatic cycling at C/20. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [20]. 2025, Mudhar A. Al-Obaidi.

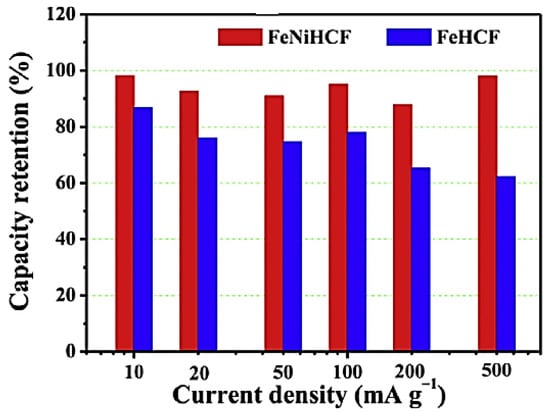

By replacing some of the iron ions with nickel ions, Yu et al. [21] reported FeNiHCF (sodium iron–nickel hexacyanoferrate) with a Prussian blue structure and described it as the cathode material of SIBs. In comparison to the FeHCF (single metal hexacyanoferrate) or NiHCF, the low-spin Fe2+/Fe3+ pair in FeNiHCF is suitably activated for sodium storage, resulting in a greater contribution of capacity at a higher voltage and improved stability on redox energy. High capacity, exceptional cycle stability, higher rate capability, and outstanding Coulombic efficiency are all synergistic benefits of the FeNiHCF cathode. Using 106 mAh/g of the discharge capacity, 97% of Coulombic efficacy, and 96% of exceptional capacity retention over 100 cycles, significant improvements in electrochemical performance were attained. FeNiHCF has higher cycle stability at all measured current densities, particularly at the 500 mA/g (maximum current density), as seen in Figure 5, which displays the capacity retention of FeNiHCF and FeHCF at various current densities throughout prolonged cycling.

Figure 5.

Capacity retention against current density of FeNiHCF and FeHCF. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [21]. 2025, Mudhar A. Al-Obaidi.

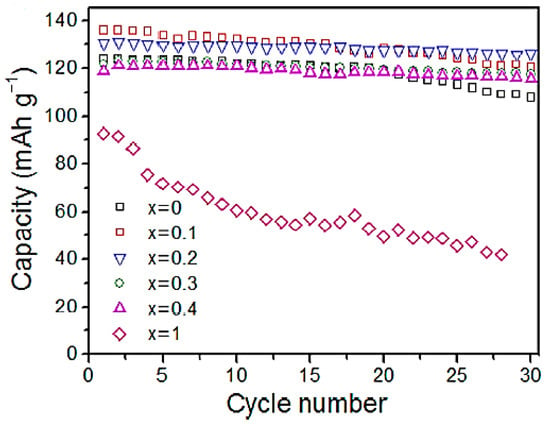

Using various samples of O3-phase NaFex(Ni0.5Mn0.5)1−xO2 (x = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 1) with various Fe concentrations was achieved by Yuan et al. [22] and examined as high-capacity cathodic hosts of Na-ion batteries. The electrochemical performance and structural stability of the O3-phase lattice can be significantly enhanced by partially substituting Fe for Ni and Mn. A Na-Fe0.2Mn0.4Ni0.4O2 cathode with an optimised Fe concentration of x = 0.2 can provide 86 mAh/g of high-rate capacity at 10 °C in a 2.0−4.0 V voltage range, a 95% of reversible capacity was attained over 30 cycles, and 131 mAh/g of the initial reversible capacity. Because of its reduced interslab distance of 5.13 Å compared to the P3 phase (5.72 Å), the as-generated OP2 phase by Fe replacement improved the cycle stability in the high-voltage charge by suppressing the co-insertion of the solvent molecules, the electrolyte anions, or both. Figure 6 shows that the capacity of virgin NaNi0.5Mn0.5O2 has dropped from 124 mAh/g to 108 mAh/g throughout 30 cycles, indicating an 87% capacity retention.

Figure 6.

Capacity against cycle number of NaFex(Ni0.5Mn0.5)1−xO2 samples using 12 Ma/g (0.05 C) of the current rate. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [22]. 2025, Mudhar A. Al-Obaidi.

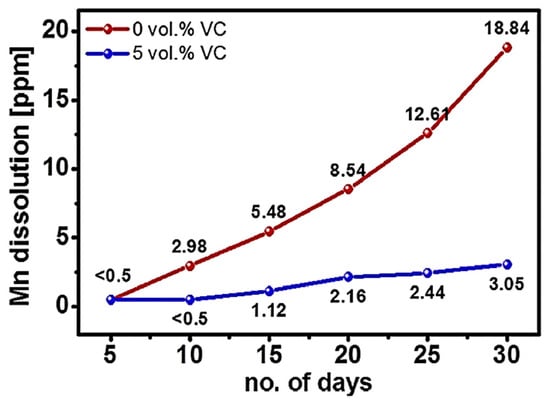

By increasing the d-spacing of the Na-ion diffusion layer, Li et al. [23] suggested a unique approach to designing high-rate efficiency cathode materials for SIBs. Significantly, the extension technique of the interplanar spacing for Na0.67Mn0.8Ni0.1Mg0.1O2 caused by co-doping Mg and Ni and the associated high-rate capacity, was outlined. The increase in the interplanar spacing of the Na-ion diffusion layer may be partly attributed to the researchers’ discovery that co-doping of Mg and Ni causes the TMO6 octahedrons to shrink and the TM–O (TM ¼ transition metal) link lengths to decrease. Co-doped Ni and Mg Na0.67Mn0.8Ni0.1Mg0.1O2 has a greater Na-ion diffusion constant than Na0.67Mn0.8Ni0.2O2 and can supply about 160, 145, 133, and 124 mA h/g at 24, 48, 120, and 240 mA/g, respectively. Specifically, MMN provided reversible capacities of 110, 66, and 37 mA h/g at 480 (2C), 1200 (5C), and 1920 (8C) mA/g of the high-current densities. Additionally, co-doping Mg and Ni simultaneously improved the cycle stability, indicating that Mg and Ni co-doping also improves the stability of the layered structure. Na2MnSiO4, a polyanion-based cathode material for SIBs, was reported by Law et al. [24]. It demonstrated remarkable sodium storage capabilities, including 210 mAh/g of the discharge capacity at 3 V (average voltage) at 0.1 C and exceptional prolonged cycling stability (500 cycles at 1 C). The use of the Mn2+ ⇋ Mn4+ redox pair was also shown by ex situ XPS, and the insertion/extraction of about 1.5 mol of sodium ions per unit of the silicate-based product was described. Additionally, the research systematically examined the impact of an electrolyte addition (of variable composition) on the sodium storage capabilities of Na2MnSiO4. Manganese dissolution was effectively decreased by the electrolyte addition, which creates an ideal defensive passivation coating on the electrode surface. As shown in Figure 7, the dissolution of Mn in the Na2MnSiO4 electrodes is much reduced when there is 5 vol.% VC in the electrolyte as opposed to the electrolyte without VC.

Figure 7.

Estimated manganese dissolution against the operational days during the immersion of Na2MnSiO4 electrodes in particular electrolytes (with 0 vol.% vs. 5 vol.% VC) at 25 °C. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [24]. 2025, Mudhar A. Al-Obaidi.

The impact of Ca-replacement in Na sites on the electrochemical and structural characteristics of Na1−xCax/2NFM (x = 0, 0.05, 0.1) was documented by Sun et al. [25]. The generated samples of Na1−xCax/2NFM exhibited a single α-NaFeO2 type phase with a somewhat amplified alkalilayer distance as the Ca concentration rises, according to the XRD patterns. Ca-substituted samples had noticeably better cycling stabilities. The Na0.9Ca 0.05Ni1/3Fe1/3Mn1/3O2 (Na0.9Ca0.05NFM) cathode obtained 116.3 mAh/g of capacity with 92% of the capacity retention rate after 200 cycles at a 1C rate. During cycling, XRD showed a reversible structural evolution via an O3-P3-P3-O3 sequence of the Na0.9Ca0.05NFM cathode. The Na0.9Ca0.05NFM cathode ascertained superior structural recoverability after cycling and a greater voltage range in the pure P3 phase state throughout the charge/discharge process if compared to NaNMF.

Na2/3Ni1/3Mn2/3O2 with a P2 phase was studied by Risthaus et al. [26] as a cathode material for SIBs. In half cells, it provided a 228 mAh/g (high discharge capacity) within a range of 1.5 and 4.5 V, which is quite more than the academic rate of 172 mAh/g. The findings of metal K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy indicated that the Ni2+/Ni4+ redox is responsible for the charge adjustment and that the manganese stays in the 4+ oxidation state throughout sodiation/desodiation. The results showed an incline in the valence state of Ni from bulk to surface for the charged electrode, in addition to a variation in the intensity of the O K-edge peak after charging. These findings powerfully indicated that some of the charge recompense occurs at the oxygen sites. Furthermore, a rapid capacity decline was caused by the carbonate-based electrolyte reacting with the cathode material, as seen by the reduction in Mn ions on the discharged electrode’s surface. An amount of 200 mAh/g of the discharge capacity was preserved by reducing the interfacial interactions using 1 M NaTFSI in Pyr14TFSI (IL of an ionic liquid electrolyte).

Gu et al. [27] showed how to use careful lattice modulation to optimise the Na-storage performance of Na3V2(PO4)2F3 (NVPF) cathode for SIBs. In NVPF, aliovalent substitution of V3+ at Na+ causes the development of Na+-migration channels and the creation of electronic defects, which improve the electronic conductivity and speed up the kinetics of Na+-migration. In the Na+-substituted NVPF (NVPF-Nax), it was indicated that the formation of robust NaO bonds with higher ionicity than V O bonds results in a notable improvement in both structural stability and ionicity. The optimised NVPF-Na0.07 (Na3.14V1.93Na0.07(PO4)2F3) exhibited an exceptional electrochemical performance due to the previously indicated effects of Na+ substitution. Consequently, NVPF-Na0.07 offered 77.5 mAh/g at 20 °C, which is a considerable-rate capability and 0.027% capacity loss per cycle over 1000 cycles at 10 °C of the ultralong cycle life. Se–reduced graphene oxide was used as the anode and NVPF-Na0.07 as the cathode in the construction of sodium-ion complete cells. The whole cells had 96.3 mAh/g at 20 °C (an extraordinary rate capability) and exceptional wide-temperature electrochemical performance from −25 to 25 °C. Additionally, it demonstrated outstanding cycling performance over 300 cycles, retaining over 90% of its capacity at 0.5 °C across a range of temperatures.

Na4Fe7(PO4)6, a zero-strain cathode for SIBs, was introduced by Pu et al. [28]. In addition to maintaining the structural stability of NFP/C, this innovative iron-based polyanionic cathode ascertained a direct path for transporting Na+ ions and electrons and 66.5 mA h/g of the reversible capacity at 5 Ma/g with nearly 100% capacity retention over 1000 cycles under 200 Ma/g. Only 0.24% of the unit-cell volume changed during sodiation or desodiation.

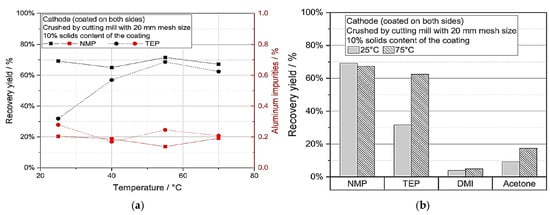

For cathode and anode coating materials, Ahuis et al. [29] proposed a solvent-based direct recycling method that enables the recovered coating materials to be used directly again. Indeed, mechanical stress can enhance the recovery of active materials of coating materials of cathodes from spent electrodes by efficiently releasing their adhesion to the substrate, which allows for their effective reuse in new electrode production. In this regard, mechanical stress obtained a high recovery yield (85% for cathodes and 96% for anodes), which made the recycling process more effective and eco-friendly. To explore the consequence of directly recycled material on the final cell and electrode efficiency, the resultant suspension was used for electrode manufacture. Regarding the electrical conductivities, around 165 mAh/g of the initial discharge capacity for graphite/NMC622 coin cells, and C-rate stability, it was evident that electrodes and cells with up to 10% recycled material work similarly well. Overall, the study showed that recovering electrode trash via direct solvent-based recycling is effective without affecting the functionality of the cells created when new material was introduced to the recycled solution. As shown in Figure 8a, a much larger recovery yield (up to 69%) can be seen after 40 °C. Also, Figure 8b depicts that 2,5-dimethylisosorbide (DMI) and acetone have poor recovery yields under 20%, making them unsuitable for wet mechanical de-coating of the cathode using the chosen construction.

Figure 8.

(a) Recovery yield and aluminium impurities against temperature. (b) Comparison of recovery yield of Triethylphosphate (TEP), 2,5-dimethylisosorbide (DMI), and acetone (various green solvents) for direct cathode scrap recycling. N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) [29].

Sun et al. [30] used bulk-sensitive X-ray absorption spectroscopy in combination with local electron energy loss spectroscopy to reveal the essential basis of voltage decay in Na-based oxygen-redox-active (ORA) cathodes. It was indicated that the voltage degradation during cycling is caused by the steric heterogeneity of Mn redox, which was obtained from the surface generation of O2 vacancies. Additionally, an ORA cathode (Na0.8Li0.24Al0.03Mn0.73O2) with little voltage decline was suggested by the researchers. Due to the robust Al–O bonds reducing the covalency of Mn–O bonds to encourage the electron localisation on oxygen, its O2 redox reversibility was greatly enhanced.

Two newly marketed cathodes, NaNi1/3Fe1/3Mn1/3O2 (NFM) and Na3V2(PO4)3 (NVP), were used by Yang et al. [31] to assess their stability in atmospheric conditions and look into the reasons for structural deterioration. Because of the thermo-dynamically favourable chemical transformation of NFM, theoretical calculations and practical observations showed that its stability under air exposure is noticeably worse than that of NVP. Additionally, the XRD studies and Raman mapping indicated that the production of alkaline, which speeds up the structural deterioration of NFM. Therefore, by eliminating pollutants and recovering surface-precipitated Na+ into the crystalline host, a straightforward second-sintering technique was suggested to improve the air stability of NFM. With successful prevention of the chemical change in NFM in air, the stabilised crystal structure shown by in situ XRD after the second-sintering treatment also confers enhanced cycling stability. This is 90.7% of a considerable capacity retention after 200 cycles. Table 1 shows a summary of the associated studies of SIBs and modified techniques.

Table 1.

A summary of the associated studies of SIBs and modified techniques.

3. Comparative Analysis of Sodium-Ion Battery Cathode Materials

The electrochemical performance of SIBs depends on cathode materials that exhibit different structural elements and electrochemical properties, and modification approaches. The key evaluation of cathode materials for SIBs examines their fundamental characteristics through an analysis of specific capacity, together with cycling stability and Coulombic efficiency, along with their distinctive advantages and shortcomings. The research aims to present a comprehensive overview of cathode material development in SIBs, together with related challenges, and demonstrate their potential practical usage. Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of sodium-ion battery cathode materials including their advantages and disadvanatges.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of sodium-ion battery cathode materials.

Cathode selection occurs based on which application matters most: energy storage capacity, operational life span, or speed of operation. Research should concentrate on manufacturing scale-up and durability testing under harsh environments and reducing expenses in order to speed up SIB commercialisation.

4. Critical Analysis of Modification Techniques to Upgrade the Efficacy of SIBs

The performance improvement of cathode materials for SIBs is imperative for advancing this technology as a practical alternative to LIBs. The revised studies collected in Table 1 signify different adjustment techniques, including element doping, surface coating, and morphological control. Referring to the obtained results, these techniques played a significant role in enhancing the electrochemical properties and overall efficacy of SIBs. First of all, element doping emerged as an extensively researched technique that optimises both electronic and ionic conductivity within cathode materials. Indeed, it is essential to understand that specific dopants can modify the lattice structure of cathode materials, supporting improved lattice stability and smoothing-enhanced ion transport pathways throughout the implication of element doping. For instance, Zhuo et al. [16] approved that doping with chromium in NaV1−xCrxPO4F can generate an initial reversible capacity of 83.3 mAh/g, together with a considerable charge–discharge efficacy of 90.3%. More specifically, the element doping technique affords additional cationic species that can stabilise the lattice and generate more favourable sites for sodium-ion insertion and extraction. This enables us to minimise distortions during charge–discharge cycles in addition to increasing electronic and ionic conductivity. Accordingly, this would assure the importance of careful selection of dopants to successfully enhance the material’s electrochemical performance. Second, Yu et al. [21] established that substituting iron ions with nickel in sodium iron–nickel hexacyanoferrate (FeNiHCF) enhanced the discharge capacity to 106 mAh/g, with a Coulombic efficacy of roughly 97%. This also indicated that doping not only improves capacity but also stabilises the material during cycling, and therefore contributes to better longevity.

The second modification technique is the surface coatings, which were represented as another effectual approach to upgrade the stability of cathode materials and lessen the side reactions throughout charge and discharge cycles. Undoubtedly, surface coating is a successful procedure to adjust the electrochemical interface, permitting smoother ion diffusion by decreasing the resistance encountered at the electrode–electrolyte interface. In this regard, Law et al. [24] elucidated that using a protective passivation film on Na2MnSiO4 electrodes can meaningfully mitigate manganese dissolution, which is essential to maintain structural integrity during operation. This proves that surface modifications can augment the operational stability of SIBs, permitting better performance longevity. Also, Gu et al. [27] indicated that delicate lattice modulation can lead to enhanced wide-temperature electrochemical performance. This would suggest that the coating technique would influence not just capacity but also the material’s resilience to environmental factors. Although surface coatings and doping can improve the overall performance, it is crucial to comprehend the long-term stability of these changes. Research on degradation mechanisms, such as the impact of humidity, temperature cycles, and mechanical stresses, can shed light on how long modified SIBs will last in practical settings. Furthermore, it is essential to appraise the economic viability of different modification methods, including the doping method. For example, although element doping can greatly increase capacity, the availability and cost of dopants such as nickel or chromium should be evaluated. More widespread use of SIB technology can be facilitated by methods that are both efficient and economical. It is also necessary to consider how using particular dopants or coatings will affect the environment. This would entail the evaluation of the materials’ potential toxicity, recyclability, and lifecycle impact. Sustainable battery technology will depend on creating changes that are both efficient and safe for the environment.

Third, the morphological control is similarly vital to ensure effective ion diffusion and maximise the use of active material. The ion transport pathway can be enhanced by developing structures that assure optimum morphology via the use of affordable techniques such as co-doping and the use of solid-state routes. In turn, greater cycling stability and performance longevity can be ascertained. In this regard, Li et al. [23] ascertained that co-doping with magnesium and nickel could upgrade the cycling stability of layered structures, ascribed to a more favourable ion diffusion layer formed through careful morphological adjustment. This signifies that the physical structure of the cathode material can clearly impact the overall performance by better smoothing the sodium-ion transport. Another example of the morphological control is Doubaji et al. [20], who elaborated that solid-state routes can deliver better capacity retention and cycling performance when integrated into optimal morphological configurations. Accordingly, the above-mentioned results can introduce the fact that modification techniques (element doping, surface coating, and morphological control) are fundamental to upgrading the performance of SIBs. Each technique assists an exclusive purpose to enhance the electrochemical features, enhancing the stability, and facilitating effective ion diffusion, highlighting the significance of a multifaceted method to material improvement. However, it should be noted that the SIB research should continue to further explore the above modification strategies to essentially overcome the existing challenges and comprehend the full potential of SIB technology.

In the context of comparing the modification techniques based on the concepts of scalability, cost, environmental impact, and industrial readiness, it should be noted that the salability and broader application of element doping can be limited due to the scarcity and high cost of specific dopants like chromium and nickel. Also, complicated process techniques are specifically associated with surface coatings that would raise the production cost. However, the morphological control techniques like integrated co-doping and solid-state synthesis can introduce a promising solution to deliver a cost-effective process if compared to other existing manufacturing processes. Interestingly, these techniques include more environmentally benign materials at reduced toxicity and lifecycle impact. In summary, the combination of multifaceted strategies is essential to advance the SIB technology towards balancing the associated cost, scalability, and environmental sustainability factors, in addition to assuring industrial readiness.

5. Limitations of Enhancement Techniques of SIBs and Possible Directions for Further Research

This section delves into the discussion of the most limitations of the used modification methods of SIBs with suggesting a number of effectual directions for future research. Regarding the doping method, the long-term impacts of different dopants on the electrochemical cycling presentation and structural integrity of SIB cathodes are not fully perceived. Further investigations are required to optimise the interactions between dopants and host materials and associated benefits. Also, future research should focus on exploring synergistic effects when using multiple dopants. Due to the variable performance of the surface coatings and inconsistent stability of these coatings over extended cycling, the prosperity of the coating methods remains a concern. Thus, there is a need to comprehensively study and assess the durability and efficiency of various coating materials in various environmental conditions. There should be an emphasis on exploring materials that can withstand cycling stresses and environmental factors, in addition to assessing the performance of coatings over time. The morphological control technique of cathode materials is predominantly associated with a complexity to enhance the ion diffusion. Thus, further research is required to simplify this technique and facilitate commercial production while maintaining performance. Clear improvement of SIB performance was ascertained by Gu et al. [27] within moderate conditions. However, the performance of SIBs was not explored at extreme temperatures or during rapid cycling. Thus, future investigations should include testing new materials under extreme conditions (high/low temperatures, rapid charge/discharge cycles) to better understand their limitations and to develop more robust materials suitable for diverse applications. In other words, the development of innovative materials that can withstand high performance across a wider range of conditions is imperative. Also, the assessment of the environmental impact of SIB materials and their recycling, in addition to evaluating the economic feasibility of large-scale production, is important [32]. Indeed, resolving these limitations and pursuing the recommendations would advance the application of SIB technology and pave the way towards more efficient, sustainable energy storage solutions.

Referring to the above discussion, future research should emphasise investigating the integrated application of the aforementioned modification techniques. For example, the simultaneous impact of integrated co-doping and surface coating on ion transport and structural stability should be studied. Also, an examination of the effect of integrated morphological adjustment and surface modification techniques is imperative to deliver effectual visions on how to optimise the overall performance across various operating conditions. The development of composite materials that combine multiple modification techniques can inevitably obtain synergistic advantages, improving both the capacity and stability of SIBs. For instance, integrating conductive polymers with doped materials would upgrade the overall electrochemical performance. In the context of the analysis of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), there is still a clear request to develop a specific review paper to discuss the electrochemical behaviour of SIB cathode materials rather than focusing on interpreting the semicircle features solely as charge-transfer resistance. Specifically, the complete understanding of the kinetics of ion transport and charge transfer mechanisms in SIB cathode materials and associated key parameters of solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) resistance and Warburg impedance can be achieved via revising the developed equivalent circuit models, which deconvolves the different influences on the impedance spectrum, exactly concentrating on SEI formation and contact resistance effects. Also, the incorporation of 3D printing and nanotechnology into battery designs may provide new ways to improve performance. For example, building hierarchical structures can enhance surface area and ion transport, possibly outperforming conventional modification methods. The continued investigation of these novel strategies would probably open up new uses for sodium-ion technology in the field of energy storage. Thus, it is fair to expect that researchers can greatly improve the performance of SIBs and make them a competitive alternative to lithium-ion systems by incorporating these modification techniques—structural optimisation, morphological control, composite formation, and doping—into the development of SIB cathodes.

6. Conclusions

The current review intends to assess the consequences of the modification techniques employed to improve the performance of SIBs, especially concentrating on element doping, surface coating, and morphological control. To systematically conduct this review, the most relevant studies were analysed, which elucidated the clear contribution of these techniques to upgrading the electrochemical characteristics of cathode materials. First of all, it was stated that doping with elements such as chromium and nickel can meaningfully improve the electronic and ionic conductivity of SIB materials, which led to enhanced capacity and competence. Second, the specific capacity of cathodes can be increased by utilising partial substitution and co-doping techniques, in addition to enhancing cycling stability. Third, referring to the morphological adjustments, it was indicated that a minimal volume change during cycling can be obtained via controlling the morphology of cathode materials while supporting ultra-long cycle life. More importantly, the issue of manganese dissolution can be successfully addressed by using the electrolyte additives, which can introduce greater operational stability and capacity retention. Fourth, the structural integrity of cathodes can be strengthened via the substitution of various metal ions, which enhance the overall capacity and resilience under various operational conditions. Statistically, the revised studies indicated the possibility of having 83.3 mAh/g of the initial reversible capacity and 90.3% of the charge–discharge efficacy while using the Cr-doped NaV1−xCrxPO4F. Furthermore, a discharge capacity of 106 mAh/g and a Coulombic efficacy of 97% were achieved using the sodium iron–nickel hexacyanoferrate, in addition to retaining 96% capacity over 100 cycles. Also, the Na4Fe7(PO4)6 (zero-strain cathode) preserved a capacity retention of around 100% after 1000 cycles, with a minimal unit-cell volume change of only 0.24%. A careful selection of the dopant type and surface modification technique can afford an enhanced capacity and proper stability at reduced detrimental side reactions and improve operational longevity. Also, the optimum morphological adjustment can assure an effective ion transport. However, there is still a necessity to conduct further investigations in this field to explore the effects of long-term doping, the durability of surface coatings, and the scalability of morphological modifications. Also, the effects of integrated modification techniques of co-doping and surface coating on ion transport and structural stability are an interesting subject to be delved into. On top of this, it should be noted that the electrochemical performance cannot be boosted by the application of the advancement techniques such as element doping, surface coating, and morphological control, and further consideration of the broader implications for scalable energy storage manufacturing and material sustainability is essential. Indeed, these suggestions would further enhance the performance and commercialisation of SIBs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A.-O.; methodology, M.A.A.-O. and F.L.R.; formal analysis, M.A.A.-O., F.L.R. and A.K.A.; investigation, A.K.A., M.M. and A.A.A.; resources, M.M. and A.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.A.-O. and F.L.R.; writing—review and editing, M.A.A.-O.; visualization, F.L.R. and A.K.A.; supervision, M.A.A.-O. and I.M.M.; project administration, M.A.A.-O. and I.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Capacity Retention | Percentage of capacity retained after cycling |

| Coulombic Efficiency | Ratio of discharge capacity to charge capacity (%) |

| d-spacing | Interplanar spacing in crystal structures |

| FeNiHCF | Sodium iron–nickel hexacyanoferrate (Prussian blue analogue cathode) |

| FT-IR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| LIBs | Lithium-ion batteries |

| mAh/g | Milliampere-hours per gram (specific capacity) |

| SDGs | Sustainable development goals |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SIBs | Sodium-ion batteries |

| TM | Transition metal |

| V | Volt (electrical potential) |

| VC | Vinylene carbonate (electrolyte additive) |

| Wh/kg | Watt-hours per kilogram (energy density) |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Singh, A.N.; Islam, M.; Meena, A.; Faizan, M.; Han, D.; Bathula, C.; Hajibabaei, A.; Anand, R.; Nam, K.W. Unleashing the potential of sodium-ion batteries: Current state and future directions for sustainable energy storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2304617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayambuka, K.; Mulder, G.; Danilov, D.L.; Notten, P.H. From li-ion batteries toward Na-ion chemistries: Challenges and opportunities. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2001310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidan, M.; Hasan, G.; Al-Obaidi, M. Comparative study between a battery and super-capacitor of an electrical energy storage system for a traditional vehicle. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2022, 35, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wu, C.; Cao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Huang, Y.; Ai, X.; Yang, H. Prussian blue cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries and other ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1702619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W.; Mao, M.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L.; Cui, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, J. Research progress on vanadium-based cathode materials for sodium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 8815–8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Q.; Du, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.J.; Li, L.; Peng, J.; Qiao, Y.; Chou, S.L. Low-cost Prussian blue analogues for sodium-ion batteries and other metal-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 9320–9335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, P.; Xu, K.; Hao, Z.; Tang, G.; Zhu, C.; Ding, Z.; Yin, S.; Li, Z.; Ding, Z.; et al. Achieving long-term cycling stability in Na3V2 (PO4) 3 cathode material through polymorphic carbon network coating. Carbon 2025, 238, 120146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, A.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Staggs, J. Modelling and simulation of thermal runaway phenomenon in lithium-ion batteries. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 19, e3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Swagata, R.; Shi, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Progress in and Application Prospects of Advanced and Cost-effective Iron (Fe)-based Cathode Materials for SIBs. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 1938–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lai, Y.; Ma, J. Engineering of Polyanion Type Cathode Materials for SIBs: Toward Higher Energy/Power Density. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, X.; Tang, K.; Wang, D.; Long, M.; Gao, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, G. Recent progress of emerging cathode materials for SIBs. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 3735–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Guo, S.; Zhou, H. Advanced cobalt-free cathode materials for SIBs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 13189–13235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristote, N.T.; Zou, K.; Di, A.; Deng, W.; Wang, B.; Deng, X.; Hou, H.; Zou, G.; Ji, X. Methods of improving the initial Coulombic efficiency and rate performance of both anode and cathode materials for SIBs. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Z.; Gu, Z.Y.; Du, M.; Zhao, X.X.; Wang, X.T.; Wu, X.L. Emerging characterization techniques for delving polyanion-type cathode materials of sodium-ion batteries. Mater. Today 2023, 66, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J. Review of cathode materials for SIBs. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2024, 74, 100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, H.; Wang, X.; Tang, A.; Liu, Z.; Gamboa, S.; Sebastian, P.J. The preparation of NaV1−xCrxPO4F cathode materials for SIB. J. Power Sources 2006, 160, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhou, H. Designing high-capacity cathode materials for SIBs. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 34, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tamaru, M.; Okubo, M.; Yamada, A. Electrode Properties of P2−Na2/3MnyCo1−yO2 as Cathode Materials for SIBs. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 15545–15551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Qian, J.; Ai, X.; Yang, H.; Cao, Y. Mesoporous Amorphous FePO4 Nanospheres as High-Performance Cathode Material for SIBs. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 3539−3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubaji, S.; Valvo, M.; Saadoune, I.; Dahbi, M.; Edström, K. Synthesis and characterization of a new layered cathode material for SIBs. J. Power Sources 2014, 266, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, Q.; Yan, M.; Jiang, Y. A promising cathode material of sodium iron–nickel hexacyanoferrate for SIBs. J. Power Sources 2015, 275, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.D.; Wang, Y.X.; Cao, Y.L.; Ai, X.P.; Yang, H.X. Improved Electrochemical Performance of Fe-Substituted NaNi0.5Mn0.5O2 Cathode Materials for SIBs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 8585−8591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Gao, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Z.; Liu, X. New insights into designing high-rate performance cathode materials for SIBs by enlarging the slab-spacing of the Na-ion diffusion layer. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Ramar, V.; Balaya, P. Na2MnSiO4 as an attractive high capacity cathode material for SIB. J. Power Sources 2017, 359, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xie, Y.; Liao, X.-Z.; Wang, H.; Tan, G.; Chen, Z.; Ren, Y.; Gim, J.; Tang, W.; He, Y.-S.; et al. Insight into Ca-Substitution Effects on O3-Type NaNi1/3Fe1/3Mn1/3O2 Cathode Materials for SIBs Application. Small 2018, 14, 1704523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risthaus, T.; Zhou, D.; Cao, X.; He, X.; Qiu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Paillard, E.; Schumacher, G.; et al. A high-capacity P2 Na2/3Ni1/3Mn2/3O2 cathode material for SIBs with oxygen activity. J. Power Sources 2018, 395, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.-Y.; Guo, J.-Z.; Zhao, X.-X.; Wang, X.-T.; Xie, D.; Sun, Z.-H.; Zhao, C.-D.; Liang, H.-J.; Li, W.-H.; Wu, X.-L. High-ionicity fluorophosphate lattice via aliovalent substitution as advanced cathode materials in SIBs. InfoMat 2021, 3, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Rong, C.; Tang, S.; Wang, H.; Cao, S.; Ding, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Z. Zero-strain Na4Fe7(PO4)6 as a novel cathode material for sodium–ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 9043–9046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuis, M.; Aluzoun, A.; Keppeler, M.; Melzig, S.; Kwade, A. Direct recycling of lithium-ion battery production scrap—Solvent-based recovery and reuse of anode and cathode coating materials. J. Power Sources 2024, 593, 233995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wu, Z.; Hou, M.; Ni, Y.; Sun, H.; Jiao, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, K.; et al. Unraveling and suppressing the voltage decay of high-capacity cathode materials for SIBs. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J. Unveiling the Origin of Air Stability in Polyanion and Layered-Oxide Cathode Materials for SIBs and Their Practical Application Considerations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2308257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, M.A.; Abdelbasir, S.M.; Hassan, S.S.; Kamel, A.H.; Rayan, D. Mechanochemical activation for lead extraction from spent cathode ray tube. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 23, 1090–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).