Abstract

Having high porosity and biocompatibility, carbon-based materials are promising candidates for tissue engineering applications, particularly as substitutes for biological tissues. This study investigates the growth and viability of osteoblasts on four different activated carbon (AC) materials and correlates biological responses with their physicochemical and morphological properties. Two materials derived from non-renewable sources—AC1, a laboratory-synthesized carbon derived from anthracite, and AC3, a commercial activated carbon (Norit GCN 830) derived from coal—and two commercial activated carbons derived from renewable sources—peat, AC2 (Norit PK1-3), and wood, AC4 (ROX 0.8)—are studied. Results showed that AC1 exhibited the highest porosity (3072 m2/g), with higher phenolic and oxygen-containing surface groups but lower cell viability. In contrast, AC2, AC3, and AC4 displayed lower porosity compared to AC1 (755, 1040, and 1083 m2/g, respectively) and fewer surface phenolic groups but sustained osteoblast proliferation. Notably, AC4 demonstrated superior performance, characterized by regions of fibrous surface, pores in the meso- and microscale range (<50 nm), and enhanced cell viability and proliferation. AC2 also showed favorable results, ranking second for cell growth support. These findings suggest that biomass-derived ACs, particularly AC4 and AC2, provide favorable environments for osteoblast viability and proliferation. AC costs were estimated at 15 to 38 times lower than those for hydroxyapatite and bioceramics, which are widely used for bone cell growth. Thus, ACs made from renewable sources are promising candidates for tissue engineering applications, offering sustainable and effective alternatives for biomedical use.

1. Introduction

Activated carbons (ACs) are highly porous, versatile, and low-cost materials that are widely used for applications such as pollutant removal, drug delivery, and catalysis due to their large surface area, tunable porosity, and chemical stability [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In medicine, ACs have been extensively researched for treating poisoning, managing drug overdoses, and addressing intestinal disorders, thanks to their high adsorption capacity and nontoxicity [7,8,9]. Nevertheless, their potential for biomedical applications beyond adsorption-based treatments remains largely unexplored. However, with their porosity and ability to interact with external compounds, ACs are promising candidates for novel applications in tissue engineering, including bone regeneration [10].

Bone defects resulting from trauma, pathological conditions, or degenerative disorders frequently necessitate therapeutic interventions, including bone grafting, biocompatible prosthetic implants, or biomaterial-based approaches designed to promote and enhance natural bone regeneration [11]. These injuries have significant socioeconomic impacts due to the large number of surgeries required, incurring substantial expenses for both treatment and recovery [12,13]. Bone repair is a complex biological process that mimics aspects of skeletal development. It involves critical contributions from extracellular matrix (ECM) components, osteoprogenitor cells, and various growth factors [14,15]. Biomaterials used in bone tissue engineering must promote angiogenesis, osteoblast differentiation, bone matrix synthesis, structural integrity support, and the functions of newly formed bone tissue [16,17]. To enhance this process, a range of biomaterials, including hydroxyapatite, biodegradable polymers, ceramics, and bioglass, have been developed [18,19,20,21] to stimulate angiogenesis, support osteoblast adhesion, and promote bone matrix deposition [17]. ACs could potentially serve as effective materials for bone induction and repair owing to their unique structural and physicochemical properties, including high porosity, large surface area, and chemical stability.

Several carbon nanomaterials, such as carbon nanotubes, nanomaterials and dots, graphene oxide, fullerenes, nanodiamonds, and their derivatives, have been applied as scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, as reported in the open literature [22,23,24,25]. These materials may enhance bone tissue regeneration through several complementary mechanisms. Their surface chemistry and electrical conductivity improve osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation by promoting intercellular signaling at the material interface [22,23,26]. Additionally, porous and mechanically resilient architectures facilitate extracellular matrix deposition and provide structural guidance for new bone formation [27] and stimulate angiogenesis because of their ability to support cell growth, enhance nutrient transport, and promote tissue regeneration [28].

Carbon-based materials have been shown to have strong potential in promoting cellular proliferation and supporting subsequent tissue repair and regeneration, especially due to their high specific surface area, tunable surface chemistry, and capacity to adsorb and deliver biomolecules [22,23,29]. Nevertheless, several challenges remain, especially for nanocarbons, including (i) potential cytotoxicity associated with residual metal catalysts [30], such as iron, nickel, and cobalt, particularly in CNT-based materials, (ii) the higher cost compared to sustainable carbons [31], and (iii) uncertainties about long-term biodegradation and in vivo safety [29].

A key limitation in the current literature is the lack of studies evaluating the potential of granular activated carbon for bone regeneration, particularly its impact on cell viability and proliferation. So far, the only work involving particulate activated carbon in this context is our previous study, which focused on in vivo tests, showing the mechanical performance of the regenerated bone [10], highlighting the need for comprehensive research into the biological responses related to activated carbon–based biomaterials. Therefore, the use of new alternatives, like sustainable carbon materials for bone cell growth, requires comprehensive preclinical evaluations, both in vitro [32,33] and in vivo [10], to assess critical parameters such as biocompatibility through viability and proliferation tests [32,33], antibacterial activity by culturing Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [34], and stability through the physicochemical properties of tested biomaterials [22,29]. These parameters can be associated with the mechanical properties of the reconstructed bone. In vitro studies are particularly fundamental for determining the cytotoxicity and compatibility of materials with specific cell cultures. Therefore, osteoblasts, which are key players in bone formation and maintenance, are essential models for assessing interactions between biomaterials and bone cells. These cells synthesize the extracellular matrix and then differentiate into osteocytes, the mature cells that sustain bone tissue [35].

Thus, this work explores an emerging research subject by evaluating the potential of sustainable, low-cost biomaterials for bone regeneration while contributing to the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): (i) SDG 3 by promoting alternative technologies designed to optimize bone regeneration and, consequently, increase clinical success rates; and (ii) SDG 9 through the application of innovative activated carbons in biomedical engineering. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the use of particulate activated carbons as biomaterials for bone cell growth. It presents the initial tests conducted to evaluate the potential of AC as a biomaterial for bone regeneration, as a follow-up to a previous study [10]. The investigated materials are AC1 and AC3, derived from non-renewable sources, and AC2 and AC4, derived from renewable materials. All AC were characterized with several methods, and their physicochemical and morphological properties were correlated to determine suitability for bone tissue engineering applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Activated Carbon Materials

Four AC materials were selected based on their distinct physicochemical properties, as described in Section 3. Two were derived from non-renewable sources (AC1 and AC3) and two from renewable sources (AC2 and AC4). AC1 was synthesized in the laboratory via KOH activation of Chinese anthracite at 750 °C followed by acid and water washing to reach neutral pH [36]. AC3 is a commercial activated carbon (Norit GCN 830) derived from selected grades of coal, typically bituminous or sub-bituminous. AC2 (Norit PK 1−3) and AC4 (Norit ROX 0.8) are commercial activated carbons made from peat, an organic material formed by the partial decomposition of plant matter, and wood charcoal, respectively. AC2 and AC4 were commercially steam-activated and then washed in a multi-step process to ensure high purity. All ACs were manually ground, and their particle size distribution (PSD) was determined using a sieve series ranging from 180 to 45 µm. Following fractionation, all material passed through the 180 µm mesh, while no particles were retained below 45 µm, confirming a final particle size range of 45–180 µm. Prior to cell culture analysis, all materials were autoclave-sterilized to ensure aseptic conditions. Samples were sterilized under standard steam autoclave conditions at 121 °C for 15 min (1.1 atm) [37].

2.2. Physicochemical Properties of ACs

The morphology of the ACs was examined at different magnifications with an FEI-Inspect F50 scanning electron microscope (SEM) with no special preparation. Briefly, the powdered ACs were affixed to conductive carbon tape and examined by SEM without prior metallization. Micro- and mesoporosity (pores smaller than 50 nm) were assessed with gas adsorption measurements after outgassing around 200 mg of each AC for 48 h under vacuum at 250 °C using an ASAP 2020 automatic adsorption apparatus (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). Nitrogen adsorption–desorption at 77 K and carbon dioxide adsorption at 0 °C were conducted to determine specific surface area, SBET (m2/g), and micropore volume, VDR (cm3/g), using BET and Dubinin calculation. Mesopore volumes, Vmeso (cm3/g), were derived from the Gurvich volume, V0.97 (the volume of liquid nitrogen adsorbed at P/P0 = 0.97), using the equation Vmeso = V0.97 − VDR (cm3/g). Pore size distribution was determined using SAIEUS with non-local density functional theory (NLDFT) models.

Mercury porosimetry was used to evaluate pores exceeding 50 nm using an AutoPore IV 9500 porosimeter (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). The samples were carefully introduced into a penetrometer, which was subsequently evacuated under controlled vacuum conditions to eliminate residual gases and moisture before the mercury intrusion. Measurements were conducted in two stages: at low pressure (0.001–0.24 MPa) and high pressure (0.24–414 MPa). Pores exceeding 3.6 nm were analyzed using Washburn’s equation:

where D (nm) is the pore diameter, P (MPa) is the applied isostatic pressure, γ (485 mJm−2) is the surface tension of mercury, and θ (140°) is the mercury contact angle.

The chemical surface properties of the ACs were examined using Boehm titration [38]. Thus, the surface functional groups were quantified via selective acid-base titration to detect the presence of oxygenated functional groups and assess their influence on adsorption properties.

2.3. Osteoblast Culture in Carbon Material

The mouse calvarial osteoblast cell line MC3T3-E1 (ATCC CRL-2593), typically used in osteogenic studies [39], was employed in this work. The cells were thawed and cultured in a Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) cell culture medium under standard conditions. Once the cell monolayer approached confluence, the culture medium was removed and the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). To detach the osteoblasts, a 0.25% trypsin solution was applied for 3 min at 37 °C. The detached cells, along with the medium used to rinse the culture flask, were collected in a Falcon tube and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min at 20 °C. Cell viability was assessed using trypan blue (0.4%) staining, and only cultures with viability exceeding 95% were used for subsequent experiments.

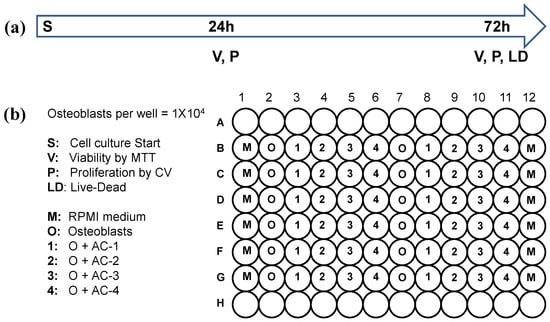

The viable cells were diluted in RPMI culture medium and distributed into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. The plates were incubated for 24 h under standard culture conditions, with wells assigned to specific experimental groups. Following incubation, the AC materials were introduced into the culture medium. The experimental groups comprised: M, a control group with 200 μL of RPMI culture medium only; OTB, an osteoblast-only control with 200 μL of RPMI medium and 1 × 104 osteoblast cells; and 20 μg of each activated carbon (AC1–AC4) with 200 μL of RPMI medium containing 1 × 104 osteoblast cells. A total of seven plates were prepared: three for viability analysis using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay at 24, 48, and 72 h; three for proliferation analysis using the crystal violet (CV) assay at the same time points (24, 48, and 72 h); and one for live/dead cell analysis at 72 h, as shown in Figure 1a,b.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol for osteoblast culture on activated carbon materials: (a) Time course, including the initial osteoblast culture and evaluated cell proliferation (P) and viability (V) by MTT or live/dead assay; and (b) Distribution of the experimental groups in cell culture plates.

The viability of the cells in each well was assessed using the MTT assay. After 24, 48, and 72 h of culture, the medium in each well was removed and the cells were washed with PBS to eliminate non-adherent and dead cells. Subsequently, 100 µL of MTT solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well. The plates were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 3 h to allow formazan crystals to form. Following incubation, 100 µL of isopropanol was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 620 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Epoch—Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA, 2019). Optical density (OD) values, corresponding to cell viability, were recorded from eight wells per group and expressed as mean standard deviation (SD).

Cell proliferation was evaluated using crystal violet (CV) staining. Osteoblasts cultured on the different activated carbon materials for 24, 48, and 72 h were analyzed. At each time point, the culture medium was removed and the wells were washed twice with 100 µL of PBS to eliminate non-adherent cells. After washing, 50 µL of CV was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. After incubation, the excess dye was thoroughly removed by washing the plates under flowing water. The stained cells were then solubilized by adding 100 µL of methanol to each well. Finally, absorbance was measured at 540 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Epoch—Biotek, 2019).

The viability of cells that adhered to the AC material was assessed using a LIVE/DEAD® Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Molecular Probes, Waltham, MA, USA). After the designated incubation periods, cells were washed with PBS and treated with a staining solution containing calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1), following manufacturer’s instructions. This assay enables differentiating between live and dead cells via dual fluorescence staining. Calcein AM emits a green signal in viable cells due to intracellular esterase activity, while EthD-1 produces a red fluorescence in non-viable cells due to plasma membrane damage. Fluorescence imaging was performed using a ZOE Fluorescent Cell Imager (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) microscope to capture images of osteoblasts in each experimental group. Two fluorescence filters were used to acquire separate green (live) and red (dead) images, which were merged to create composite images. Green and red/yellow fluorescence intensities were quantitatively analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 5. The retrieved data were used to generate graphical representations in GraphPad Prism 5.

Data from the cellular analysis, including osteoblast viability, proliferation, and live/dead assays, were expressed as the mean standard deviation (SD). Groups were compared statistically using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 5 (San Diego, CA, USA) at p ≤ 0.05 statistical significance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Activated Carbons

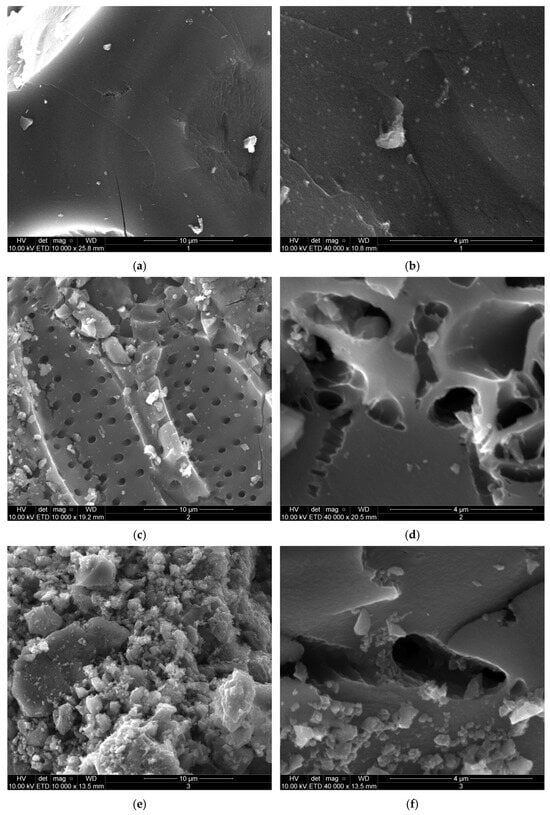

Developing suitable materials for bone substitutes remains a significant challenge in tissue engineering due to the complex biological requirements of bone tissue, including biocompatibility, porosity, and the ability to support essential cellular functions such as matrix formation. In addition, material morphology is a critical determinant for bone regeneration, as it directly influences cell adhesion, cell proliferation, and the overall effectiveness of bone reconstruction. For materials intended as biological substitutes, other essential properties include the presence of pores with optimal dimensions to facilitate cell adhesion and growth, and connectivity based on a three-dimensional structure that enhances cell communication and supports extracellular matrix development [40]. Moreover, carbon-based materials, having extensive surface area and well-developed porosity, have demonstrated the ability to selectively adsorb various substances and are proposed to improve cell adhesion and proliferation [41]. Accordingly, the morphology of the ACs was systematically examined using SEM at different magnifications, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SEM images of activated carbons (ACs): AC1 (a,b), AC2 (c,d), AC3 (e,f), and AC4 (g,h) at 10,000× and 40,000× magnification.

At 10,000× agnification, all analyzed materials exhibit distinct internal porous structures. AC1 appears to have the lowest porosity, as detected by this method, with few macropores visible even at higher magnification (40,000×) (Figure 2a,b), while AC3 displays a rougher surface texture, with irregular particles of diverse sizes. In contrast, AC2 (Figure 2c,d) and AC4 (Figure 2g,h) shows the presence of macropores randomly distributed across the material surface, a characteristic feature of biomass-derived materials [42]. For AC4, this morphology is combined with parallel, striated, and layered features, in some regions, (Figure 2g), mimicking the organized collagen matrix and mineralized layers in bone tissue [43]. In bone tissue, this fibrous structure is attributed to the calcification of collagen fibers during bone formation [44], a process known to enhance the mechanical properties of the final tissue [10]. Thus, developing biomaterials with a morphology that mimics the ECM of natural bone appears to be an important factor for facilitating effective bone regeneration, as they could promote tissue restoration and functionality [45,46,47].

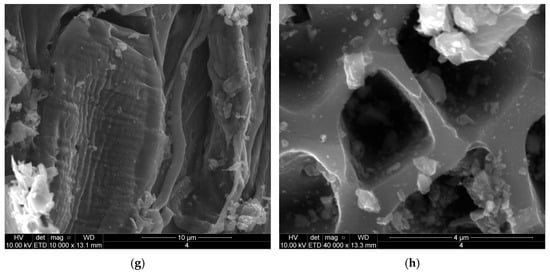

Textural properties also play a vital role in bone healing, as ACs typically have high porosity and large surface area. As in other nanostructured biomaterials, these characteristics enhance the adsorption of adhesive proteins such as laminin and collagen, which mediate cell-surface interactions [47], while the porous structure provides a suitable environment for bone tissue growth by promoting cell adhesion, proliferation, and biomaterial integration [48]. In this study, the four AC materials were characterized using CO2 adsorption (Figure 3a), N2 adsorption (Figure 3b), and mercury porosimetry to evaluate porosity across a broad pore size range (0–50 nm).

Figure 3.

(a) CO2 adsorption isotherms at 0 °C; (b) Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K, full and empty symbols, respectively.

Figure 3a presents the CO2 adsorption isotherms for the studied ACs. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (Figure 3b) correspond to type Ib according to IUPAC classification [49], indicating a wide pore size range including both larger micropores and smaller mesopores. The hysteresis present in AC2 and AC4 is attributed to the presence of mesopores, likely resulting from the progressive widening of micropores and the collapse of previously blocked pores, which is typical for carbon-based biomass [50].

The textural properties obtained from CO2 and N2 adsorption measurements were calculated and are summarized in Table 1. Of the analyzed materials, AC1 shows the highest surface area and micro- and mesopore volumes. Despite its morphology, which suggests the absence of visible pores, its high porosity is attributable to an extensive network of small pores that are undetectable by SEM (Figure 2a,b). This structural characteristic results in an exceptionally high surface area, a typical feature of chemical ACs. The renewable materials (AC2 and AC4) exhibit mesopores and micropores in near fractions, as determined from the N2 adsorption data (Table 1), with AC2 showing the lowest BET surface area among all samples. In contrast, AC3 shows specific surface area (SBET) and micropore volume (VDR) values comparable to those for AC4, yet its mesopore volume is barely negligible.

Table 1.

Porous properties of activated carbons from CO2 and N2 adsorption data: BET surface area (SBET); total (V0.97), micropore (VDR), and mesopore volumes (Vmeso); mesopore and micropore fractions from N2 adsorption data.

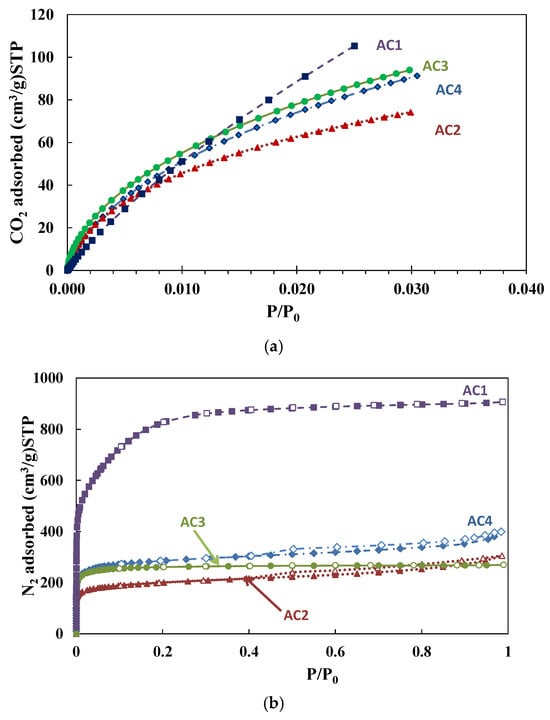

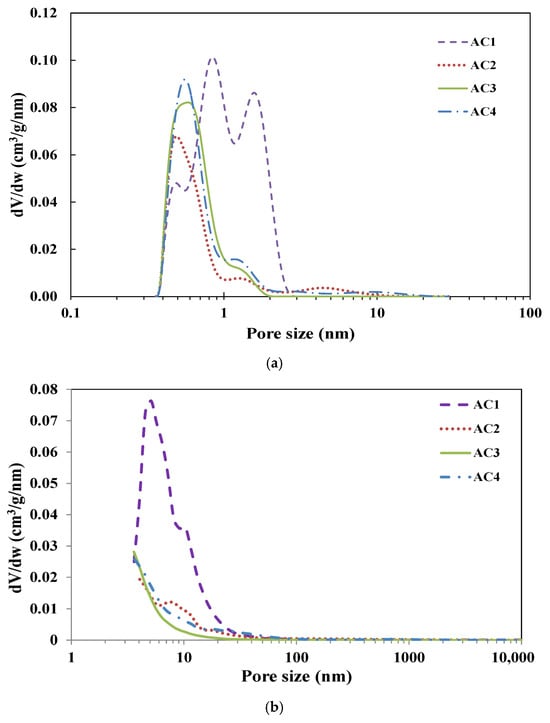

The corresponding pore size distributions (PSD) for N2 and CO2 isotherms, calculated using SAIEUS with NLDFT models, are presented in Figure 4. All samples exhibit a predominantly microporous structure, with most pores below 2 nm, consistent with the isotherm types observed for these materials. The renewable materials AC2 and AC4 display a narrow peak in the pore size distribution ranging from 0.5 to 0.6 nm. In contrast, AC1 exhibits a trimodal distribution with peak pore sizes centered at 0.5, 0.8, and 1.6 nm, while AC3 shows a narrower distribution between 0.5 and 0.7 nm. Additionally, all AC samples demonstrate a considerable presence of mesopores within the 3–30 nm range, as corroborated by the textural parameters summarized in Table 1.

Figure 4.

(a) Pore size distribution calculated by SAIEUS using NLDFT models for all ACs from CO2 and N2 isotherms (a); and calculated from Hg porosimeter using Equation (1) for all ACs (b).

Figure 4b illustrates the pore size distribution of mesopores exceeding 3.6 nm and macropores, as determined by mercury porosimetry. The AC samples exhibit a distinct peak within the 3 to 30 nm range, aligning with the N2 adsorption data. Beyond this range, the remaining pores are distributed over a broad scale ranging from 30 nm to 416 microns. The total mesopore volumes (3.6 < Ø < 50 nm) and macropore volumes (Ø > 50 nm), as calculated from the mercury porosimetry data, are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters obtained from mercury porosimetry data: Mesopore volume, Vmeso Hg, (3.6 < Ø > 50 nm); macropore volume, Vmacro, (Ø > 50 nm); mesopore and macropore fractions.

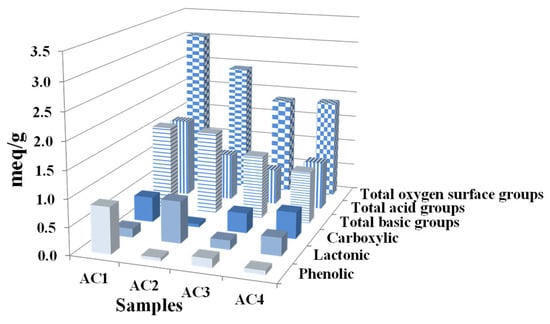

Among the physicochemical properties of biomaterials, surface chemistry is an important factor in bone tissue integration and the formation of biologically active surfaces [51], as it facilitates both cell adhesion and proliferation [52]. Specific chemical moieties directly modulate cellular responses by influencing protein adsorption, ligand presentation, and intracellular signaling pathways, thereby affecting cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [53,54]. In the case of carbon materials, these properties are particularly significant, as they can influence cellular interactions at the injury site due to their high surface area and tunable functionalization potential, which can be engineered to enhance interactions with bone-forming cells (e.g., osteoblasts) and potentially contribute to bone regeneration [55]. Therefore, the surface chemistry was analyzed by Boehm titration.

This technique enables quantifying chemical groups on AC surfaces. Figure 5 illustrates the presence of various groups, including phenolic hydroxyl (–OH), lactonic (–COOR), carboxylic (–COOH), and total acidic and basic groups, with distinct variations among ACs. A comparison between AC1 and AC4 also reveals some similarities in surface chemistry, with similar carboxylic group contents (~0.5 meq/g) and acid/base ratios. However, the total quantities of acidic and basic groups differ between these two biomaterials: AC1 (~1 meq/g) and AC4 (~1.5 meq/g). In contrast, the renewable materials AC2 and AC4 show the highest quantities of lactonic groups (0.77 and 0.33 meq/g, respectively) and the lowest concentrations of phenolic groups (0.06 and 0.08 meq/g, respectively). In bone tissue engineering, functional groups such as phenolic, lactonic, and carboxylic moieties may enhance adhesion and cell proliferation [56]. Indeed, phenolic compounds have been reported to influence osteoblast differentiation, potentially regulating their proliferation in experimental rat models [57,58]. Further studies are needed to elucidate the relationships between these surface chemical properties and cellular behavior.

Figure 5.

Functional groups on the surface of ACs (meq/g) determined by Boehm titration.

3.2. Osteoblast Culture in Activated Carbon Materials

Biocompatibility is a fundamental requirement for materials intended for medical applications [59]. Therefore, these materials must be evaluated for cell proliferation and viability to determine their potential to support tissue regeneration and integrate effectively with the surrounding biological environment. A thorough understanding of the interplay between surface chemistry, porosity, and their influence on cellular behavior is essential for optimizing biomaterials for applications such as bone regeneration, wound healing, and the development of medical implants.

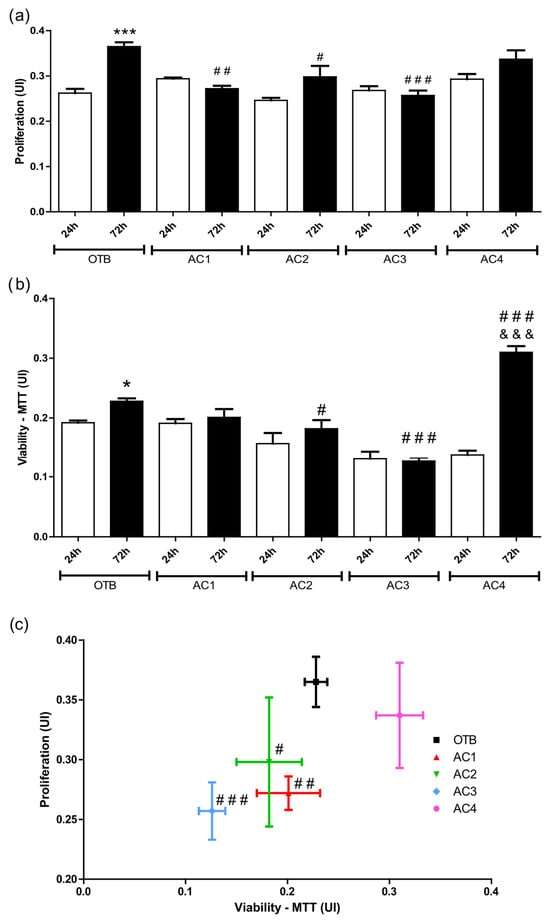

To achieve a comprehensive understanding of cellular proliferation in different culture conditions, multiple comparative analyses were performed. The OTB—72 h group exhibits a statistically significant increase in cell proliferation compared to the OTB—24 h group (p ≤ 0.001), as shown in Figure 6a, highlighting the influence of temporal factors on the regulation of cellular proliferation. In contrast, at 72 h, a significant reduction in cell proliferation is observed in AC1 and AC3 compared to OTB control (72 h). Interestingly, AC4 demonstrates a proliferation rate comparable to that for OTB at 72 h.

Figure 6.

(a) OTB proliferation and (b) OTB viability at 24 and 72 h in different culture mediums; and (c) Relationship between proliferation and cell viability at 72 h. * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001 vs. OTB (24 h). # p < 0.05; ## p < 0.01; ### p < 0.001 vs. OTB (72 h). &&& p < 0.001 vs. AC4 (24 h).

Similarly, osteoblast viability was assessed across the different experimental conditions (Figure 6b). A significant increase in cell viability is observed for the OTB—72 h group (p ≤ 0.05) compared to the OTB—24 h group. In contrast, reduced cell viability is observed in the AC2—72 h (p ≤ 0.05) and AC3—72 h (p ≤ 0.001) groups compared to the OTB—72 h control group. Notably, the AC4—72 h group (p ≤ 0.001) exhibits a significant increase in cell viability compared to both the AC4—24 h and OTB—72 h groups, suggesting its potential to support cellular activity.

Figure 6c illustrates the correlation between cell proliferation and viability at 72 h. Reductions in both cell proliferation and viability are observed in the AC1, AC2, and AC3 experimental groups. Statistically, the AC4 group exhibits proliferation rates comparable to those of the control group (OTB), while demonstrating enhanced cell viability. As previously discussed, viable cells maintain essential functions such as energy production, protein synthesis, and cell division, which are critical for sustaining regular cellular activity [60]. Nutrient availability also plays a key role in preserving cellular functions. Although carbon-based materials are inherently inert, their highly interconnected porous structure may contribute to cell growth. Additionally, the strong adsorption capacity of ACs [1,61], combined with their morphological and textural properties, may facilitate the retention of nutrients from the culture medium within their structure. This mechanism could support osteoblast proliferation and improve overall cell viability.

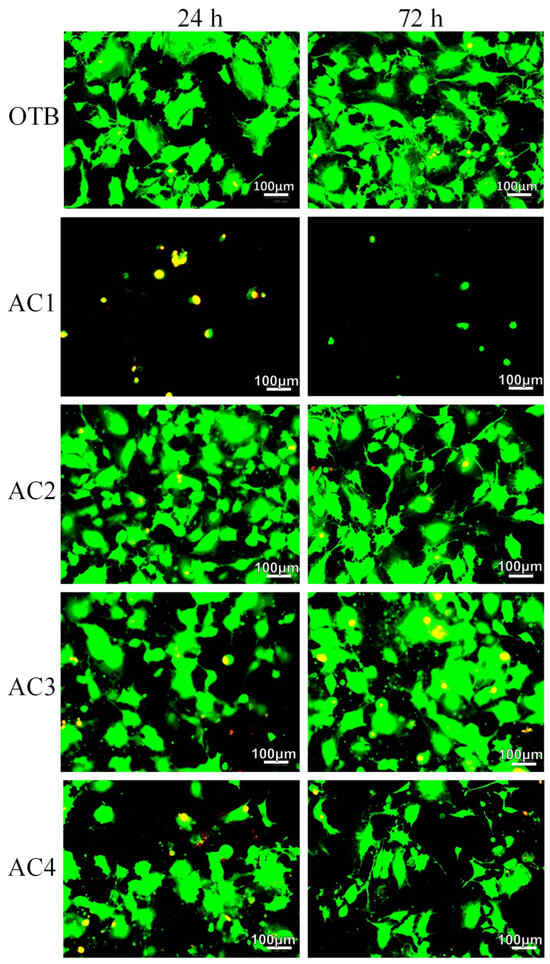

To further investigate cell viability, the viable and non-viable cells that adhered to the carbon material were quantified using live/dead staining under fluorescence microscopy. In this technique, viable cells are stained green and non-viable cells appear yellow/reddish, with the carbon material visible as a black background. Representative images of experimental groups (OTB, AC1, AC2, AC3, and AC4) at 24 and 72 h are presented in Figure 7. Qualitative analysis revealed a marked reduction in both the number of cells and osteoblast viability in the AC1 group at 24 h and 72 h compared to the OTB control. However, no significant differences are observed in the remaining experimental groups compared to OTB control and 24 h measurements within each group. The fluorescence images (Figure 7) reveal osteoblast growth on carbon-based materials, providing significant insights into tissue engineering approaches. The three-dimensional structure of carbon materials, characterized by interconnected pores and high adsorption capacity, may facilitate cell attachment and proliferation [62], which probably facilitated nutrient uptake from the culture medium, thereby promoting a favorable microenvironment for osteoblast proliferation and sustaining cell viability.

Figure 7.

Representative fluorescence microscopy images from the live/dead viability assay. Experimental groups include osteoblasts cultured alone (OTB) and osteoblasts cultured on carbon materials (AC1, AC2, AC3, and AC4) at 24 and 72 h. Images were captured at 400× magnification.

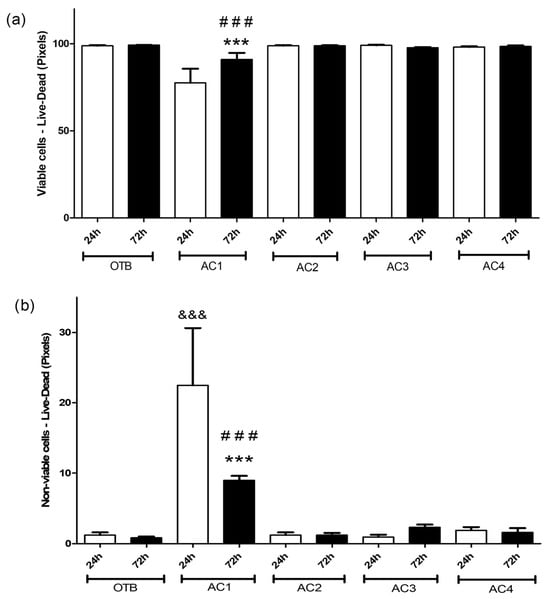

In addition to qualitative analyses, quantitative evaluations were conducted to systematically assess cell viability across different culture conditions. The histological images obtained with live/dead staining are graphically represented in Figure 8a,b, representing viable and non-viable cells, respectively. Figure 8a shows a significant reduction in viable cells in the AC1—72 h group (p ≤ 0.001) only, unlike both the AC1—24 h group and the OTB—72 h control group. In contrast, the remaining experimental groups (AC2, AC3, and AC4) show viable cell counts comparable to the OTB group at both 24 h and 72 h. The quantification of non-viable cells (Figure 8b) supports these findings, demonstrating that only the AC1 group exhibits a significant increase in non-viable cells at both 24 h (p ≤ 0.001) and 72 h (p ≤ 0.001) compared to the OTB control group at corresponding time points. These results are consistent with the qualitative fluorescence images, reinforcing the distinct behavior observed for AC1.

Figure 8.

Cell viability at 24 and 72 h using live/dead staining for (a) viable cells; and (b) nonviable cells. &&& p < 0.001 vs. OTB—24h, *** p < 0.001 vs. AC1—24 h and ### p < 0.001 vs. OTB—72 h.

Studies using carbon nanomaterials (carbon nanotubes, nanomaterials and dots, graphene oxide, fullerenes, nanodiamonds) also showed cell viability and proliferation compared to activated carbons made from biomass [25]. The adsorption of biomolecules on AC at room temperature is defined by thermodynamic parameters, including the spontaneity and character of interactions at the material interface [63]. Typically, adsorption on AC is exothermic and spontaneous under ambient conditions [64], reflecting favorable interactions with proteins, ions, and molecules present in biological environments. For instance, the adsorption of bovine serum albumin (BSA), a model protein commonly used to study cell adhesion, is significantly influenced by temperature and the surface characteristics of AC [65]. As previously discussed, the high degree of microporosity in these materials results in pronounced adsorption of organic compounds [61]. This strong adsorption can sequester essential biomolecules within the porous structure or on the surface functional groups of the carbon, potentially limiting their bioavailability and impacting cellular processes such as adhesion, viability, and proliferation, consequently leading to an inaccurate assessment of cytotoxicity [66,67]. These findings are consistent with the observed behavior of AC1, which exhibited higher cytotoxicity compared to the other tested materials, likely due to its higher surface area (3072 m2/g) and micro-mesopores (1.40 cm3/g) and macropores (4.04 cm3/g) volumes, enhancing the adsorption of key biomolecules necessary for cellular function. Moreover, the adsorption processes on activated carbon suggest reduced molecular freedom, which can hinder the dynamic exchange of biomolecules necessary for effective cell-material interactions [68,69]. Accordingly, these thermodynamic parameters not only affect the physicochemical environment at the AC interface, but they also influence the biochemical signals that are critical for supporting cell growth and function. Therefore, for optimal AC-based biomaterials for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications, these interactions must be properly balanced.

When the cellular responses are correlated with the structural characteristics of the AC materials, several important considerations emerge regarding their potential use as bone substitutes. Interestingly, the renewable carbon materials AC2 and AC4 performed better on both cell proliferation and viability, with AC4 demonstrating the most favorable cellular response. In contrast, AC1 and AC3, the non-renewable sourced ACs, showed lower cell proliferation and viability, indicating that their structural and chemical properties may be less conducive to supporting cellular growth and functionality in bone tissue applications.

These findings suggest that highly porous carbon materials with high concentrations of micropores (<2 nm) may influence nutrient availability in the culture medium due to their strong adsorptive properties that may impact cell proliferation. Notably, materials with greater micropore volumes were associated with lower cell proliferation. Importantly, although AC4 has a surface area and micropore volume comparable to AC3, it contains a higher proportion of meso- and macropores, which may contribute to better nutrient accommodation and improved cell proliferation. This suggests that the balance between meso- and macropores plays a significant role in promoting cellular activity and, consequently, tissue regeneration.

Additionally, from a morphological standpoint, the combined effect of surface roughness and, in the case of AC4, fibrous texture in some regions, likely enhanced cell adhesion and proliferation by providing a favorable microenvironment for osteoblast growth. Moreover, the micrometric porosity of renewable carbon materials (AC2 and AC4), as shown in Figure 2d,h, is crucial for supporting osteoblast accommodation and proliferation, as their dimensions fall within the micrometer scale (20–50 μm) [70]. Therefore, achieving optimal porosity is essential to enhance cell adhesion, whereas excessive porosity may promote nutrient adsorption from the culture medium, thereby hindering cellular growth.

Cell viability on the material surfaces showed similar results across the AC2, AC3, and AC4 groups. In contrast, the AC1 group showed significant decreases in both cell adhesion and viability, as demonstrated by the live/dead assay (Figure 7 and Figure 8). This fact supports the earlier observation that the higher porosity of AC1, with its high adsorption capacity, disrupts the culture medium and impairs cell growth and viability. Cell viability is decisive for maintaining essential cellular functions, including DNA replication, protein synthesis, metabolism, and the capacity to survive and proliferate under suitable conditions [60]. Based on the results of the present study, AC2 and AC4 offer favorable conditions for osteoblast viability and proliferation and are therefore promising candidates for sustainable bone biosubstitutes and viable alternatives for bone tissue engineering applications.

Additionally, a previous study by our research team demonstrated that the use of the same AC materials in in vivo bone repair models did not induce renal or hepatic toxicity [10]. Furthermore, the incorporation of these materials into the repair process resulted in favorable bone organization and improved biomechanical properties, with particularly promising results for the renewable AC4 [10]. These findings highlight the potential of sustainable and renewable materials in bone repair applications, offering eco-friendly options for future biomedical advancements while aligning with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development goals [71]. This approach emphasizes the importance of environmentally conscious innovations to advance biomedical technologies.

Therefore, using ACs as bone substitutes may offer several advantages over conventional bone substitutes, such as hydroxyapatite and bioceramics. The use of precursor materials is a critical factor that impacts the final cost of bone graft substitutes [72], and AC presents a cost-effective and practical substitute, particularly for healthcare applications in resource-limited settings. The cost of precursors is generally influenced by factors such as geographic location, transportation costs, and import/export taxes, which can significantly affect the final price. Furthermore, in publicly funded healthcare systems, government agencies assume a significant portion of the financial responsibilities associated with the treatment of bone defects. This allocation of resources highlights the considerable economic impact on the overall healthcare infrastructure.

Additionally, ACs can be used either alone or in combination with other biomaterials, potentially reducing overall costs while preserving the biological properties of bone [10]. Due to their substantially lower costs compared to conventional precursors, ACs offer a competitive advantage, with prices approximately 15 to 38 times lower than those for hydroxyapatite and bioactive glass powder, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of costs for primary precursors used in bone bio-substitutes (Sigma Aldrich).

Other key advantages of using ACs as bone bio-substitutes include the provision of larger surface areas, tunable porosity, and the potential for surface functionalization. These characteristics can significantly enhance cell-biomaterial interactions and facilitate tissue growth. Moreover, activated carbons may demonstrate superior bio-adsorption properties for therapeutic agents, thereby offering more adaptable and sustainable alternatives for tissue engineering applications, particularly in the field of bone regeneration.

However, further investigations into the use of AC for bone regeneration across various tissue types are needed. Different bones typically exhibit distinct structural and chemical characteristics, necessitating tailored pore distributions and surface chemistries to enhance biological performance [73]. Future studies should explore the mechanisms of cell adhesion, including the use of three-dimensional (3D) cell cultures to assess ECM formation on these materials. Moreover, a detailed investigation of pore size distribution and porosity ratios could enhance the potential of these materials for bone repair applications and as carriers for therapeutic molecules.

4. Conclusions

The proliferation of osteoblast cells appears to be influenced by multiple properties of ACs, including surface chemistry, textural characteristics, and morphological features. Among the tested materials, the biomass-derived activated carbons AC2 and AC4 exhibited the most favorable biological responses. Notably, AC4, followed by AC2, demonstrated advantageous porosity and surface chemistry, with larger pore sizes (micro-, meso- and macropores) and pronounced surface morphology that facilitated cell adhesion. Moreover, AC4 was the only biomaterial to display a morphological region structure that closely mimicked mineralized collagen on bone tissue, which may have further contributed to its superior performance in supporting osteoblast proliferation and viability.

The combined effects of porosity, morphology and surface chemistry in AC4 played a key role in promoting bone regeneration. In contrast, the lower effectiveness in cell proliferation and viability observed in the non-renewable materials AC1 and AC3 may be attributed to their high micropore content. Excessive microporosity increases the material’s adsorptive capacity, leading to nutrient depletion from the culture medium and consequently impaired cell proliferation.

In conclusion, renewable AC is a cost-effective and biocompatible material that shows promise for the development of sustainable bone substitutes. These findings align with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, reinforcing the potential of biomass-derived carbon materials for advanced biomedical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L.M. and G.A.-L.; methodology, D.d.C.P., D.V.S., V.F. and A.C.; validation, G.A.-L., G.F.B.L.e.S. and R.L.M.; formal analysis, A.F.R. and P.A.-M.; investigation, P.A.-M., A.F.R. and J.A.S.J.; data curation, P.A.-M., A.P.L.d.O. and S.R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.-L., D.d.C.P., D.V.S., A.C. and V.F.; writing—review and editing, G.A.-L., R.L.M. and F.L.B.; visualization, S.R.Z. and R.L.M.; supervision, R.L.M.; project administration, R.L.M.; funding acquisition, R.L.M., F.L.B. and G.F.B.L.e.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study employed immortalized mouse calvarial osteoblast cell lines (MC3T3-E1, ATCC CRL-2593), which were kindly donated by Professor Luciene Machado dos Reis from the Medical Research Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo (USP). As established cell lines, their use does not involve live animal experimentation and therefore does not require additional ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Braghiroli, F.L.; Amaral-Labat, G. Chapter 18—Biochar Modification Methods: Property Engineering for Diverse Value-Added Applications. In Biochar Ecotechnology for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment; Kumar, A., Vara Prasad, M.N., Kumari, P., Solanki, M.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 523–559. ISBN 978-0-443-29855-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bratek, W.; Światkowski, A.; Pakuła, M.; Biniak, S.; Bystrzejewski, M.; Szmigielski, R. Characteristics of Activated Carbon Prepared from Waste PET by Carbon Dioxide Activation. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 100, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Khandaker, T.; Anik, M.A.; Hasan, M.K.; Dhar, P.K.; Dutta, S.K.; Latif, M.A.; Hossain, M.S. A Comprehensive Review of Enhanced CO2 Capture Using Activated Carbon Derived from Biomass Feedstock. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 29693–29736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintas Salamba, M.; Melo, R.L.F.; da Silva Aires, F.I.; de Matos Filho, J.R.; Nascimento Dari, D.; Luz Lima, F.L.; Ferreira Alcântara Araújo, S.; da Costa Silva, L.; Fernandes da Silva, L.; Alexandre Chirindza, E.; et al. Porosity of Activated Carbon in Water Remediation: A Bibliometric Review and Overview of Research Perspectives. ACS EST Water 2025, 5, 2070–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumra; Ahmed, S. Comprehensive Review on the Environmental Remediation of Pharmaceuticals in Water by Adsorption. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2025, 44, 1457–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.C.; Jalil, A.A.; Nguyen, L.M.; Nguyen, D.H. A Comprehensive Review on the Adsorption of Dyes onto Activated Carbons Derived from Harmful Invasive Plants. Environ. Res. 2025, 279, 121807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.O. Poisoning. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2006, 7, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, G.R. The Role of Activated Charcoal and Gastric Emptying in Gastrointestinal Decontamination: A State-of-the-Art Review. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2002, 39, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, H.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Birnbaum, A.H. AGA Technical Review on the Evaluation of Food Allergy in Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 1026–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Publio, M.L.; Amaral-Labat, G.A.; Mattos, P.A.; Rodrigues, A.F.; Del Bel, M.L.S.; de Carvalho Pereira, D.; Mello, D.C.; De Souza, V.; Silva, G.F.; Fierro, V.; et al. Activated Carbon as a Bone Substitute: Enhancing Mechanical and Morphological Properties in a Rat Tibia Defect Model. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2025, 37, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindeler, A.; McDonald, M.M.; Bokko, P.; Little, D.G. Bone Remodeling during Fracture Repair: The Cellular Picture. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 19, pp. 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Murta, M.G.M.B.; Martucci, L.G.; Gomes Neto, L.F.; Ruinho, P.B.; de Souza Candido, S.; dos Santos, P.R.S.; da Fonseca Sarmento, J.P.; Santos, S.C.; da Silva, E.L.D.; Pacheco, T.S. Osteomyelitis within the SUS: Analysis of the Epidemiological Profile, Cost of Hospitalization, Average Length of Stay and Mortality in the Last 5 Years. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e6612139291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.; Alexander, Z.; Crawford, H.; Te Ao, B.; Selak, V.; Mutu-Grigg, J.; Lorgelly, P.; Grant, C. Hospitalisation Cost for Paediatric Osteomyelitis and Septic Arthritis in New Zealand. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2025, 61, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Einhorn, T.A. Developmental Aspects of Fracture Healing and the Use of Pharmacological Agents to Alter Healing. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2003, 3, 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjiargyrou, M.; Lombardo, F.; Zhao, S.; Ahrens, W.; Joo, J.; Ahn, H.; Jurman, M.; White, D.W.; Rubin, C.T. Transcriptional Profiling of Bone Regeneration: Insight into the Molecular Complexity of Wound Repair* 210. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 30177–30182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, E.S.; Cardoso, F.T.S.; Medeiros Filho, J.F.; Barreto, M.D.; Teixeira, R.M.; Wanderley, A.L.; Fernandes, K.E. Organic and Inorganic Bone Graft Use in Rabbits’ Radius Surgical Fractures Rapair: An Experimental and Comparative Study. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2005, 13, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.D.; Fernandes, K.R.; Sperandio, E.F.; Pastor, F.A.C.; Nonaka, K.O.; Parizotto, N.A.; Renno, A.C.M. Comparative Study of the Effects of Low-Level Laser and Low-Intensity Ultrasound Associated with Biosilicate® on the Process of Bone Repair in the Rat Tibia. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2012, 47, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Flausse, A.; Henrionnet, C.; Dossot, M.; Dumas, D.; Hupont, S.; Pinzano, A.; Mainard, D.; Galois, L.; Magdalou, J.; Lopez, E. Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Hydrogel Containing Nacre Powder. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101, 3211–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezwan, K.; Chen, Q.Z.; Blaker, J.J.; Boccaccini, A.R. Biodegradable and Bioactive Porous Polymer/Inorganic Composite Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3413–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkel, J.; Woodruff, M.A.; Epari, D.R.; Steck, R.; Glatt, V.; Dickinson, I.C.; Choong, P.F.M.; Schuetz, M.A.; Hutmacher, D.W. Bone Regeneration Based on Tissue Engineering Conceptions—A 21st Century Perspective. Bone Res. 2013, 1, 216–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etinosa, P.O.; Osuchukwu, O.A.; Anisiji, E.O.; Lawal, M.Y.; Mohammed, S.A.; Ibitoye, O.I.; Oni, P.G.; Aderibigbe, V.D.; Aina, T.; Oyebode, D.; et al. In-Depth Review of Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite Biomaterials from Natural Resources and Chemical Regents for Biomedical Applications. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 106010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Maleki, A.; de la Guardia, M.; Bani, M.S.; Chenab, K.K.; Pashazadeh-Panahi, P.; Baradaran, B.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Hamblin, M.R. Carbon Based Nanomaterials for Tissue Engineering of Bone: Building New Bone on Small Black Scaffolds: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 18, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arambula-Maldonado, R.; Mequanint, K. Carbon-Based Electrically Conductive Materials for Bone Repair and Regeneration. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 5186–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhao, T.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Leblanc, R.M. Bone Tissue Engineering via Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. Adv. Heal. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 1901495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindarajan, D.; Saravanan, S.; Sudhakar, S.; Vimalraj, S. Graphene: A Multifaceted Carbon-Based Material for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, J.; Rogachuk, B. Activated Carbon Utilization for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 225–234. ISBN 9780443138409. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami, S.; Baheiraei, N.; Shahrezaee, M. Biomimetic Reduced Graphene Oxide Coated Collagen Scaffold for in Situ Bone Regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukasheva, F.; Adilova, L.; Dyussenbinov, A.; Yernaimanova, B.; Abilev, M.; Akilbekova, D. Optimizing Scaffold Pore Size for Tissue Engineering: Insights across Various Tissue Types. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1444986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Lantada, A.D.; Mager, D.; Korvink, J.G. Carbon-Based Materials for Articular Tissue Engineering: From Innovative Scaffolding Materials toward Engineered Living Carbon. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Cellular Toxicity and Immunological Effects of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, A.F.N.; Munhoz, M.G.C.; Amaral-Labat, G.; Lima, R.G.A.; Medeiros, L.I.; Medeiros, N.C.F.L.; Fonseca, B.C.S.; Braghiroli, F.L.; Lenz e Silva, G.F.B. Why Sustainable Porous Carbon Should Be Further Explored as Radar-Absorbing Material? A Comparative Study with Different Nanostructured Carbons. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 1639–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Cell Growth and Function on Calcium Phosphate Reinforced Chitosan Scaffolds. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004, 15, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobe, K.; Willbold, E.; Morgenthal, I.; Andersen, O.; Studnitzky, T.; Nellesen, J.; Tillmann, W.; Vogt, C.; Vano, K.; Witte, F. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Biodegradable, Open-Porous Scaffolds Made of Sintered Magnesium W4 Short Fibres. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 8611–8623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchacka, E.; Pstrowska, K.; Kułażyński, M.; Beran, E.; Fałtynowicz, H.; Chojnacka, K. Antibacterial Agents Adsorbed on Active Carbon: A New Approach for S. aureus and E. coli Pathogen Elimination. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsenty, G.; Wagner, E.F. Reaching a Genetic and Molecular Understanding of Skeletal Development. Dev. Cell 2002, 2, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fierro, V.; Fernández-Huerta, N.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Celzard, A. Impact of Synthesis Conditions of KOH Activated Carbons on Their Hydrogen Storage Capacities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 14278–14284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Punshon, G.; Darbyshire, A.; Seifalian, A. Effects of Sterilization Treatments on Bulk and Surface Properties of Nanocomposite Biomaterials: Effects of Sterilization on the Properties of Nanocomposite Biomaterials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2013, 101, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, H.P. Surface Oxides on Carbon and Their Analysis: A Critical Assessment. Carbon. N. Y. 2002, 40, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponchiado, P.A.I.; Melo, M.T.; Cominal, J.G.; Martelli Tosi, M.; Ciancaglini, P.; Ramos, A.P.; Maniglia, B.C. Biomembranes Based on Potato Starch Modified by Dry Heating Treatment: One Sustainable Strategy to Amplify the Use of Starch as a Biomaterial. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriou, R.; Tsiridis, E.; Giannoudis, P. V Current Concepts of Molecular Aspects of Bone Healing. Injury 2005, 36, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, M.; Lim, J.; Park, Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Yoon, J.; Choi, J.-W. Carbon-Based Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 7142–7156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Y.X. Activated Carbon from Biomass Sustainable Sources. C J. Carbon Res. 2021, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, M.; Mouloungui, E.; Castillo Dali, G.; Wang, Y.; Saffar, J.-L.; Pavon-Djavid, G.; Divoux, T.; Manneville, S.; Behr, L.; Cardi, D.; et al. Mineralized Collagen Plywood Contributes to Bone Autograft Performance. Nature 2024, 636, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszta, M.J.; Cheng, X.; Jee, S.S.; Kumar, R.; Kim, Y.-Y.; Kaufman, M.J.; Douglas, E.P.; Gower, L.B. Bone Structure and Formation: A New Perspective. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2007, 58, 77–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-M.; Liu, X. Advancing Biomaterials of Human Origin for Tissue Engineering. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 53, 86–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, R.A.; Won, J.-E.; Knowles, J.C.; Kim, H.-W. Naturally and Synthetic Smart Composite Biomaterials for Tissue Regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiara, G.; Letizia, F.; Lorenzo, F.; Edoardo, S.; Diego, S.; Stefano, S.; Barbara, Z. Nanostructured Biomaterials for Tissue Engineered Bone Tissue Reconstruction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 737–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, F.; Ye, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, K.; Wang, D. Bioactive Apatite Incorporated Alginate Microspheres with Sustained Drug-Delivery for Bone Regeneration Application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 62, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, N.C.F.L.; Amaral-Labat, G.; de Medeiros, L.I.; Boss, A.F.N.; Fonseca, B.C.d.S.; Munhoz, M.G.d.C.; Silva, G.F.B.L.e.; Baldan, M.R.; Braghiroli, F.L. Optimizing Activation Temperature of Sustainable Porous Materials Derived from Forestry Residues: Applications in Radar-Absorbing Technologies. J. Renew. Mater. 2025, 13, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L.; Polak, J.M. Third-Generation Biomedical Materials. Science 2002, 295, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Tan, Z.; Ye, X. Recent Trends in the Development of Bone Regenerative Biomaterials. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 665813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.P.; Bobbala, S.; Karabin, N.B.; Frey, M.; Liu, Y.; Navidzadeh, J.O.; Stack, T.; Scott, E.A. Surface Chemistry-Mediated Modulation of Adsorbed Albumin Folding State Specifies Nanocarrier Clearance by Distinct Macrophage Subsets. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, T.D.; Zhang, T.; Dimitrov, E.; Ghosh, A.; da Silva, A.M.H.; Melo, W.C.M.A.; Tsumura, W.G.; Silva, A.D.R.; Sousa, G.F.; Viana, B.C.; et al. Carbon Nanomaterial-Based Hydrogels as Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 6153–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X. The Utilization of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials in Bone Tissue Regeneration and Engineering: Respective Featured Applications and Future Prospects. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2022, 16, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, R.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M. Surface Modifications of Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 7938–7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, O.; De Luna-Bertos, E.; Ramos-Torrecillas, J.; Ruiz, C.; Milia, E.; Lorenzo, M.L.; Jimenez, B.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Rivas, A. Phenolic Compounds in Extra Virgin Olive Oil Stimulate Human Osteoblastic Cell Proliferation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-R.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Park, J.-E.; Yun, H.-M. 7-HYB, a Phenolic Compound Isolated from Myristica Fragrans Houtt Increases Cell Migration, Osteoblast Differentiation, and Mineralization through BMP2 and β-Catenin Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H.M.; Abu Serea, E.S.; Salah-Eldin, R.E.; Al-Hafiry, S.A.; Ali, M.K.; Shalan, A.E.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Recent Progress in Graphene-and Related Carbon-Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Biosensors for Early Disease Detection. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 964–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddart, M.J. Cell Viability Assays: Introduction. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 740, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mojoudi, N.; Mirghaffari, N.; Soleimani, M.; Shariatmadari, H.; Belver, C.; Bedia, J. Phenol Adsorption on High Microporous Activated Carbons Prepared from Oily Sludge: Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Tian, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Shen, Y.; Wang, X.; Luan, J. Carbon Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 990362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadou Kiari, M.N.; Konan, A.T.S.; Sanda Mamane, O.; Ouattara, L.Y.; Ibrahim Grema, M.H.; Siragi Dounounou Boukari, M.; Adamou Ibro, A.; Malam Alma, M.M.; Yao, K.B. Adsorption Kinetics, Thermodynamics, Modeling and Optimization of Bisphenol A on Activated Carbon Based on Hyphaene thebaica Shells. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, L.; Yáñez, O.; Mena-Ulecia, K.; Hidalgo-Rosa, Y.; García-Carmona, X.; Ulloa-Tesser, C. Exploring the Adsorption of Five Emerging Pollutants on Activated Carbon: A Theoretical Approach. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.G.; Veloso, C.M.; da Silva, N.M.; de Sousa, L.F.; Bonomo, R.C.F.; de Souza, A.O.; da Guarda Souza, M.O.; Fontan, R.d.C.I. Preparation of Activated Carbons from Cocoa Shells and Siriguela Seeds Using H3PO4 and ZnCL2 as Activating Agents for BSA and α-Lactalbumin Adsorption. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 126, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L.-M.; Phillips, G.J.; Davies, J.G.; Lloyd, A.W.; Cheek, E.; Tennison, S.R.; Rawlinson, A.P.; Kozynchenko, O.P.; Mikhalovsky, S. V The Cytotoxicity of Highly Porous Medical Carbon Adsorbents. Carbon N. Y. 2009, 47, 1887–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnatskaya, V.; Shlapa, Y.; Lykhova, A.; Brieieva, O.; Prokopenko, I.; Sidorenko, A.; Solopan, S.; Kolesnik, D.; Belous, A.; Nikolaev, V. Structure and Biological Activity of Particles Produced from Highly Activated Carbon Adsorbent. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashhadimoslem, H.; Safarzadeh Khosrowshahi, M.; Jafari, M.; Ghaemi, A.; Maleki, A. Adsorption Equilibrium, Thermodynamic, and Kinetic Study of O2/N2/CO2 on Functionalized Granular Activated Carbon. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 18409–18426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yu, X.; Maimaitiniyazi, R.; Zhang, X.; Qu, Q. Discussion on the Thermodynamic Calculation and Adsorption Spontaneity Re Ofudje et al. (2023). Heliyon 2024, 10, e28188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahtabian, S.; Mirhadi, S.M.; Tavangarian, F. From Rose Petal to Bone Scaffolds: Using Nature to Fabricate Osteon-like Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 21633–21641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Gillman, C.E.; Jayasuriya, A.C. FDA-Approved Bone Grafts and Bone Graft Substitute Devices in Bone Regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 130, 112466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.A.; Caviquioli, G.; Biguetti, C.C.; de Andrade Holgado, L.; Saraiva, P.P.; Rennó, A.C.M.; Kawakami, R.Y. A Novel Bioactive Vitroceramic Presents Similar Biological Responses as Autogenous Bone Grafts. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2012, 23, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).