Abstract

This study aims to estimate the organic load of oily wastewater by using Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) measurements, addressing the analytical challenges posed by the hydrophobic, nonpolar, and often emulsified nature of Fats, oil and grease (FOG). This study established a reproducible and practical methodology for measuring COD in wastewater containing FOG at a laboratory scale, utilizing the nonionic surfactant T80 as a solubilizing and emulsifying agent. Precise gravimetric methods were employed to measure the mass of T80 (indirectly from volume (100–1400 µL/L)) added, and its correlation with COD was established. A strong linear relationship (R2 = 0.993–0.998) between T80 concentration and COD confirmed its stability and suitability as a calibration standard. Experiments with sunflower (1–4 mL/L) and rapeseed oils (1–3 mL/L) showed that COD increased linearly with oil concentration and stabilized after prolonged mixing (96–120 h), indicating complete emulsification and micellar equilibrium. Even under T80 overdose conditions, COD retained linearity (R2 > 0.99), though absolute values were elevated due to excess surfactant oxidation. Temperature variation (5 and 20 °C) and mild heating of coconut fat (30–32 °C) showed no significant effect on COD reproducibility, indicating that mixing time and surfactant dosage are the dominant factors influencing measurement accuracy. Overall, the study establishes T80 as a reliable surfactant for solubilizing oily matrices, providing a consistent and repeatable approach for COD assessment of wastewater containing FOG. The proposed method offers a practical basis and a step towards environmental monitoring and process control in decentralized and industrial wastewater treatment systems.

1. Introduction

Fats, oils, and grease (FOG) are common constituents found in both municipal and industrial wastewaters. In urban systems, FOG infiltrates the sewage network from domestic kitchens, restaurants, and cafeterias. In industrial contexts, effluents from food processing, dairy, meat, and oil refining industries often contain high concentrations of lipidic substances, such as cooking oils, animal fats, and grease from machinery [1]. These lipidic compounds pose significant challenges because they tend to segregate, solidify, and adhere to pipe walls, leading to the formation of deposits or “fatbergs” in sewage systems. Such accumulations disrupt downstream biological treatment processes by forming floating crusts, obstructing inlets, and reducing mass transfer efficiency [2,3].

Flotation, particularly dissolved air flotation (DAF), is one of the most widely used methods for removing FOG from wastewater because hydrophobic FOG particles readily attach to microbubbles and rise to the surface for skimming. While highly effective for separating free and dispersed FOG, DAF has notable limitations: it struggles with stable emulsions unless chemical coagulants are added, requires careful control of pH and dosing, and produces substantial float sludge that must be further processed [4,5]. For this reason, DAF is typically paired with grease interceptors or traps in engineered wastewater systems to retain floating oil layers and solids before primary treatment. The FOG collected from these units is commonly transported to municipal sludge digesters for co-digestion or converted into biogas and other energy products, an approach generally more economical than aerobic oxidation [6]. However, despite these management strategies, quantifying the actual organic load contributed by FOG remains challenging. Because fats and oils are hydrophobic, nonpolar, and prone to forming emulsions or separate phases, they cannot be measured directly with a standard probe or sensor. As a result, wastewater practitioners rely on indirect methods, most notably COD, which reflects the oxygen required to chemically oxidize the organic constituents in a sample, including oily fractions [7]. COD is typically determined after digestion with strong oxidants, since direct gravimetric or spectroscopic measurement of diverse lipid species in complex wastewater matrices is cumbersome and often inaccurate. Thus, DAF and grease separators form essential components of FOG control, but their operational limitations and the analytical challenges associated with FOG quantification highlight the need for integrated treatment and monitoring approaches.

One possible approach to improve the quantification of FOGs involves their solubilization using organic solvents or synthetic surfactants. For instance, the USEPA Method 1664 employs a gravimetric procedure involving organic solvent extraction. Although effective, this method is labor-intensive, requiring extensive equipment and multiple procedural steps. Furthermore, when comparing results obtained with different solvents, it is necessary to specify the solvent used, as the oil recovery efficiency varies with solvent type. Alternatively, surfactants can be employed to solubilize oily water. Surfactants facilitate the demulsification of water-in-oil (W/O) emulsions by reducing interfacial tension through their amphiphilic nature, allowing the emulsion to break upon continuous agitation [8]. Various surfactants such as Triton X-100, Triton X-114, and Tween 80 have been utilized for this purpose. Considering the objective of measuring COD in oily wastewater, especially in influent streams, the choice of surfactant is critical. Triton-based surfactants can negatively affect sludge microorganisms even at low concentrations [9]. Therefore, polyoxyethylene sorbitan monooleate (Tween 80) presents a more suitable alternative. Tween 80 effectively dissolves and homogenizes FOGs, enabling the accurate measurement of COD in wastewater containing these components [8,10]. As Janiyani et al. investigated the solubilization of high-molecular-weight hydrocarbons from oil sludge using the nonionic surfactant Tween 80, they showed that optimal hydrocarbon release occurs at a 10:1 sludge-to-surfactant ratio and increases with agitation and contact time. pH showed little influence, while higher sludge loads reduced efficiency due to surface-area limitations. The study highlights surfactant-assisted solubilization as a potential pretreatment to enhance biodegradation and recovery of hydrocarbons [10].

Tween 80 is generally considered environmentally benign because it is readily biodegradable under aerobic and anaerobic conditions; its decay follows first-order kinetics in soil with a half-life of about 35 days. However, it can interfere with biological treatment at higher concentrations: micellar partitioning can dilute contaminants and hinder mass transfer to cells or enzymes, direct surfactant toxicity can reduce microbial biomass, and some degraders preferentially consume Tween 80 over target pollutants, all of which suppress biodegradation in certain cases and soils [11].

To our knowledge, only a limited number of studies have focused on the direct COD measurement of oily waters [10,12]. This study addresses this gap by developing an approach and methodology for determining the COD of FOG-containing wastewater using Tween 80 as a synthetic surfactant. Sunflower and rapeseed oils were employed as representative FOGs, and the reproducibility of the method was evaluated over time. Through this approach, we aim to provide a practical and reproducible solution to the long-standing challenge of quantifying the organic load of oily wastewaters.

2. Materials and Methods

All reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and employed without further purification. Coconut fat (250 g, Kokosfett, Antwerpen, Belgium) was obtained from Walter Rau Lebensmittelwerke GmbH, while sunflower oil and rapeseed oil were purchased from local markets. Tween 80 (500 mL) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Hot plates (Janke and Kunkel, Staufen im Breisgau, Germany), thermometer (Almemo, Holzkirchen, Germany), HACH cuvettes (LCK114, LCK014, LCK514, LCK914, (HACH Lange GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany), DR 5000 spectrophotometer (HACH Lange GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany), thermostat (HACH HT 200S, (HACH Lange GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany), and HACH pipette (1–5 mL, (HACH Lange GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany) were used in the analysis. All solutions were prepared using double-distilled water.

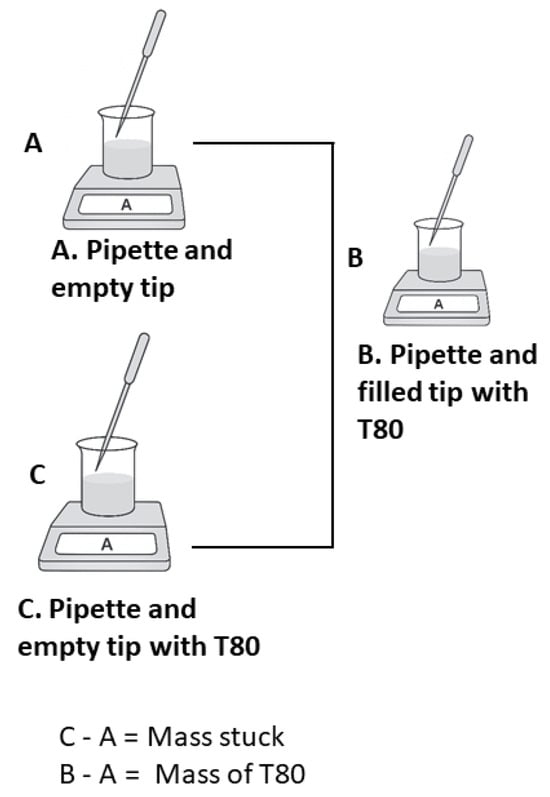

To ensure precision, the volume of Tween 80 (T80) could not be directly measured due to its viscosity. Therefore, the following procedure was adopted: To adjust the pipette on the balance, a small beaker was used. The weight of the empty pipette, including the pipette tip, was first recorded as A. The weight of the filled pipette and tip containing T80 was then measured as B, followed by the weight of the empty pipette and tip after pouring out the T80, recorded as C. The amount of T80 withdrawn was calculated by subtracting A from B, while the mass of T80 adhering to the pipette tip was determined by subtracting A from C (Figure 1). The withdrawn T80 was transferred into the relevant 600 mL beaker, and the empty pipette and tip were reweighed to accurately determine the amount of T80 introduced into the beaker for the corresponding COD measurement. The volume and mass have been calculated vice versa by using the density of the substance from Equation (1).

d = m/V

Figure 1.

Measurement of Tween 80.

A range of T80 volumes (100–700 µL) was measured into different beakers, followed by the addition of ultrapure water to a final volume of 500 mL. The mixtures were stirred for a specified duration at 600 revolutions per minute (rpm) using a magnetic stirrer on hot plates. At predetermined time intervals, designated volumes corresponding to the HACH cuvettes were withdrawn and transferred into the cuvettes. The cuvettes were then placed in a HACH HT 200S thermostat for 15 min. Before and after sampling, the cuvettes were rotated by using Lab Dancer D S40 (VWR, Darmstadt, Germany). After cooling, the COD was measured using a DR 5000 spectrophotometer (HACH). The COD determination method followed is DIN ISO15705: 2003-1 [13].

To measure the COD of oily waters, different amounts of T80 were added as described previously, followed by the addition of known quantities of oils (sunflower or rapeseed). Ultrapure water was then added to bring the total volume to 500 mL, and the same procedure was followed to determine the COD of the oils by subtracting the COD contribution of T80. All measurements were performed in triplicate. Furthermore, to investigate the effect of T80 overdose, the weight of T80 and sunflower oil was not measured, but was added directly.

To measure the COD of coconut fat, the same procedure was followed. Because coconut fat is solid at room temperature and melts at 22–25 °C, the sample was gently heated to 25 °C until fully liquefied. The melted fat was then weighed, and the COD analysis was performed using the same equipment and steps as described for the other samples, including the beaker, pipette, and tip.

3. Results and Discussion

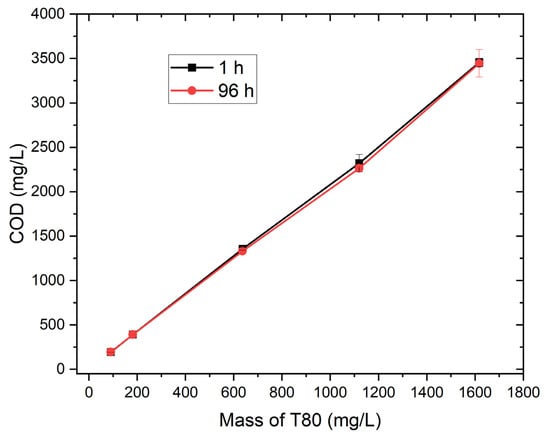

A clear and reproducible linear relationship was observed between the mass of T80 (Table S1) and the measured COD values (Table S2), as shown in Figure 2, with R2 values of 0.993 and 0.998 after 1 h and 96 h of mixing, respectively. This strong correlation demonstrates that COD increases proportionally with the amount of T80 added, indicating that each increment of surfactant consistently contributes to the total oxidizable organic load. The nearly identical slopes confirm the chemical stability of T80 and suggest that complete oxidation occurs regardless of mixing duration. The slight difference in intercepts may reflect minor baseline variation rather than chemical change. Prolonged mixing (96 h) ensures full micellar equilibration and homogenous dispersion of T80 in water, minimizing any aggregation effects observed during the early stage (1 h). These results validate the linear response of COD with T80 concentration, confirming that Tween 80 can be reliably used as a solubilizing and calibration agent for reproducible COD measurement in oily or emulsified water systems.

Figure 2.

Tween 80 vs. COD after 1 h and 96 h.

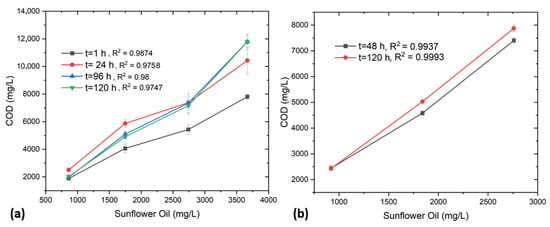

In further experiments, a series of tests were conducted using sunflower oil (0.5–2 mL) with varying amounts of T80 as presented in Table S3, to determine the COD. The COD was measured at regular time intervals of 1, 24, 96, and 120 h using relevant HACH cuvettes, as summarized in Table S4. Figure 3a,b illustrates the variation in COD with increasing sunflower oil concentrations in the presence of T80 under different mixing durations.

Figure 3.

(a) Sunflower oil vs. COD after regular intervals, (b) Overdose of oil and T80 vs. COD.

In Figure 3a, a distinct and reproducible increase in COD is observed with rising sunflower oil concentration across all mixing times as studied by Cisterna-Osorio and Arancibia-Avila [12], exhibiting strong linearity (R2 values ranging from 0.9758 to 0.9874). At the initial stage (1 h), the COD values are comparatively lower, likely due to incomplete solubilization or emulsification of oil droplets within the aqueous phase. As the mixing time extends to 24, 96, and 120 h, the COD values increase and subsequently stabilize, indicating progressive micellar solubilization and uniform dispersion of the oil facilitated by T80. The surfactant’s amphiphilic nature, having a hydrophilic polyoxyethylene head and a hydrophobic oleate tail, reduces interfacial tension, promoting the formation of fine oil-in-water emulsions. Consequently, the oil becomes more accessible to oxidation during COD analysis. Beyond 96 h, the COD trend reaches equilibrium, signifying that micellar stabilization and solubilization are complete, with minimal variation in the measured values. The high degree of linearity confirms that the COD response is directly proportional to the amount of dispersed oil, validating the reliability of T80 in enabling reproducible COD measurements for oily matrices under sufficient mixing conditions [12,14].

Figure 3b presents the COD behavior of sunflower oil under T80 overdose conditions, where the surfactant amount was not pre-measured (Table S5). COD was determined after 48 and 120 h, and in both cases, a nearly perfect linear relationship (R2 = 0.9937 and 0.9993) between COD and oil concentration was observed (Table S6). Although the surplus surfactant ensures immediate and complete emulsification of the oil, it also elevates the baseline COD, as oxidation involves both the oil and the excess surfactant. The slight increase in COD between 48 and 120 h suggests continued redistribution and stabilization of micellar structures over time. The results underline that while the linearity of the COD concentration relationship remains unaffected under overdose conditions, precise quantification of T80 is essential to avoid overestimation of COD. Overall, these findings highlight the dual role of T80 as both an effective emulsifying agent and an additional organic contributor to COD, emphasizing the need for careful control of surfactant concentration in COD determination of oily wastewater [14].

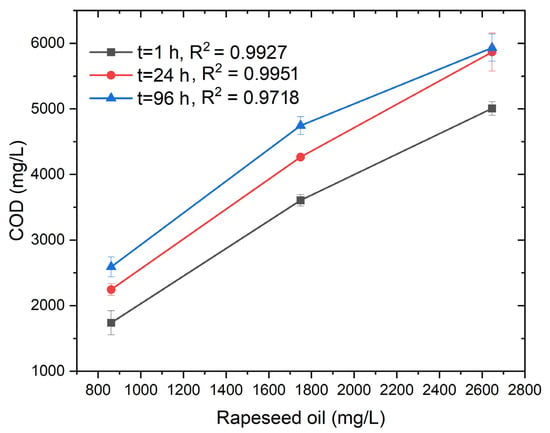

Figure 4 presents the relationship between the COD and the concentration of rapeseed oil (mg L−1) at different mixing durations (1, 24, and 96 h) in the presence of T80. The data exhibit a clear linear trend (R2 = 0.9927 and 0.9951), confirming that COD increases proportionally with rapeseed oil concentration (Tables S7 and S8). This indicates that the organic load introduced by rapeseed oil can be reliably quantified through COD analysis when T80 is used as an emulsifying agent.

Figure 4.

Rapeseed oil vs. COD after regular intervals.

At the initial mixing stage (1 h), the COD values are comparatively lower, likely due to incomplete emulsification and limited interaction between the oil and the aqueous phase. With prolonged mixing (24 h), COD increases as micellar solubilization improves and oil droplets become more uniformly dispersed within the medium. After 96 h, COD values reach their maximum, demonstrating enhanced emulsification and stabilization of oil-in-water systems. As described earlier, T80 facilitates the process through its amphiphilic nature, thereby reducing interfacial tension and promoting micelle formation. This micellar encapsulation enables better accessibility of the organic matter to dichromate oxidants during COD digestion, leading to higher measured values.

The consistently high R2 values (>0.97) across all time intervals confirm the reproducibility and linearity of COD responses with respect to rapeseed oil concentration. The slight increase in COD from 24 h to 96 h suggests that extended mixing enhances micellar stability and complete solubilization. Overall, these findings demonstrate that T80 effectively supports homogeneous dispersion of rapeseed oil, enabling accurate and time-dependent COD quantification of oily wastewater samples.

To further assess the influence of temperature on the COD of oily samples, additional experiments were performed using sunflower oil with the addition of T80 at two different temperatures, i.e., 5 °C and 20 °C. These temperatures have been selected to study the effect of average winter temperatures as well as the summer average temperature. The COD was measured at regular intervals, and the corresponding values are presented in Tables S9 and S10. The results revealed that temperature variation within this range had no significant effect on the measured COD values of sunflower oil emulsions. In contrast to expectations that elevated temperature might enhance solubilization and micellar dynamics, the COD values were found to be inconsistent and poorly reproducible, indicating that temperature does not play a supportive role in improving COD determination for oil-surfactant mixtures. The absence of a clear temperature dependence can be attributed to the limited thermal sensitivity of nonionic surfactants such as T80, whose micellar stability and emulsification efficiency remain largely unchanged over moderate temperature variations. Furthermore, since the COD method involves chemical oxidation under strongly acidic and high-temperature digestion conditions (typically 150 °C during analysis), the pre-incubation temperature during emulsification exerts negligible influence on the final oxidizable load measured.

Similarly, experiments conducted with coconut fat required the use of a comparatively higher dose of Tween 80 owing to its solid nature and low solubility at room temperature (Table S11). To facilitate dispersion, the mixture was gently heated to approximately 30–32 °C until a homogeneous solution was obtained. However, the resulting COD values (Table S12) remained inconsistent and irreproducible, even after controlled heating. This inconsistency likely arises from incomplete dissolution and phase separation of coconut fat, which leads to heterogeneous sample matrices and variable oxidant accessibility during digestion. The results collectively suggest that moderate heating does not improve COD reproducibility or accuracy for oily samples such as sunflower oil or coconut fat. In these systems, the determining factors for COD consistency are the extent of emulsification and micellar stability, rather than the temperature of pre-mixing. Therefore, maintaining uniform surfactant-to-oil ratios and sufficient mixing times is more critical than temperature control for reliable COD measurement in FOG (fats, oils, and grease) analysis.

Overall, the results of this study demonstrate that Tween 80 is highly effective in solubilizing oils and generating reproducible, linear COD responses for both sunflower and rapeseed oils under controlled mixing conditions. The strong correlations (R2 > 0.97) across various time intervals confirm that the emulsification process driven by Tween 80 is sufficient for consistent oxidant accessibility during COD measurement. These findings imply that conventional COD methods, typically challenged by phase separation and incomplete dispersion of hydrophobic substances, can be adapted for oily matrices with the strategic use of nonionic surfactants. This offers a practical pathway for wastewater treatment plants to more accurately quantify FOG-related organic loads, especially at influent points where heterogeneous oily wastewaters are common.

An important advantage of this approach is its simplicity and compatibility with existing COD analytical infrastructure. Tween 80 is inexpensive, widely available, and less toxic than alternatives such as Triton X-series surfactants, making it suitable for routine laboratory use. Moreover, the method avoids complex solvent extraction steps required in gravimetric methods (e.g., USEPA 1664), reducing labor and minimizing solvent waste. The linear response between oil concentration and COD also allows the potential development of calibration curves for real-time estimation of FOG content.

However, the study revealed a few limitations. Excess surfactant (overdose conditions) artificially elevates COD values, highlighting the need for precise dosing and quality control. Inconsistent and non-reproducible results obtained for coconut fat and temperature-dependent trials indicate that the method may not be universally applicable to all FOG types, particularly those with higher melting points or strong tendencies toward phase separation. Additionally, the long mixing times required to achieve equilibrium (up to 96 h) may restrict applicability in time-sensitive operational settings. Despite these constraints, the method presents a valuable contribution to COD analysis for oily wastewaters at the laboratory scale.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a systematic approach to the determination of COD in wastewater containing FOG by employing T80 as a solubilizing and emulsifying agent. A clear and reproducible linear relationship was observed between the concentration of T80 and the corresponding COD values, confirming its suitability as a calibration standard for oily water systems. The experiments conducted with sunflower and rapeseed oils further demonstrated that COD values increased proportionally with oil concentration and reached equilibrium after prolonged mixing, highlighting the importance of adequate emulsification time for achieving homogeneity and measurement reproducibility. Even under T80 overdose conditions, the linearity between COD and oil concentration remained intact, although the absolute COD values were elevated due to the additional organic contribution from excess surfactant, underscoring the need for precise surfactant quantification.

Temperature variation (5–20 °C) showed negligible influence on COD determination, suggesting that the emulsification and micellization efficiency of nonionic surfactants like T80 remains stable under moderate thermal conditions. Similarly, experiments involving coconut fat required mild heating for solubilization, yet the COD values remained inconsistent, indicating that temperature has no significant role in improving the accuracy or reproducibility of COD measurements.

Overall, the results confirm that Tween 80 serves as an effective and reliable agent for dispersing hydrophobic compounds such as fats and oils in aqueous media, thereby facilitating accurate COD measurement. The study establishes a reproducible methodology for assessing the organic load in oily wastewater at laboratory scale, emphasizing that controlled surfactant dosing, sufficient mixing, and stable emulsification are the key factors influencing COD reliability rather than temperature adjustments. This approach provides a framework for future applications in monitoring and characterizing wastewater containing oils at the laboratory scale and a basis for industrial scale.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemengineering9060138/s1. Table S1: Various amounts of Tween 80 for calibration curve calculations; Table S2: COD values for various amounts of Tween 80 after 1 and 96 h; Table S3: Various amounts of T80 and sunflower oil experiment to measure COD in 500 mL; Table S4: Final calculation of COD values after subtracting T80 COD from sunflower oil experiments in one liter; Table S5: Direct measurement of T80 and Sunflower oil to observe effect of overdose; Table S6: COD measurement of T80 with Sunflower oil by overdose; Table S7: Various amounts of T80 and Rapeseed oil experiment to measure COD in 500 mL; Table S8: Final calculation of COD values after subtracting T80 COD from rapeseed oil experiments; Table S9: Investigate the effect of temperature over T80 and sunflower oil with COD at 5 °C; Table S10: Investigate the effect of temperature over T80 and sunflower oil with COD at 20 °C; Table S11: Various amounts of coconut fat and T80 at higher temperature; Table S12: Final calculation of COD values after subtracting T80 COD from coconut experiments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, N.A.; visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks for the support and funding provided for this work by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy as part of the implementation of the DostAS project in the federal program Unternehmen Revier, as well as for the cooperation with the district of Spree-Neiße/Wokrejs Sprjewja-Nysa, the processing partner of the Federal Government, and with Wirtschaftsregion Lausitz GmbH as regional partner.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Husain, I.A.F.; Alkhatib, M.F.; Jami, M.S.; Mirghani, M.E.S.; Zainudin, Z.B.; Hoda, A. Problems, Control, and Treatment of Fat, Oil, and Grease (FOG): A Review. J. Oleo Sci. 2014, 63, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, H.H.; Roddick, F.; Jegatheesan, V.; Gao, L.; Pramanik, B.K. Tackling Fat, Oil, and Grease (FOG) Build-up in Sewers: Insights into Deposit Formation and Sustainable in-Sewer Management Techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fats, Oils, Grease|Engineering|City of Madison, WI. Available online: https://www.cityofmadison.com/engineering/sanitary-sewer/education/fats-oils-grease?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Edzwald, J.K. Dissolved air flotation and me. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2077–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Alegría, J.A.; Muñoz-España, E.; Flórez-Marulanda, J.F. Flotación por aire disuelto: Una revisión desde la perspectiva de los parámetros del sistema y usos en el tratamiento de aguas residuales. TecnoLógicas 2021, 24, e2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fats, Oil, and Grease Best Management Practices Manual Pollution Prevention and Compliance Information for Kitchens, Restaurants, and Other Business Owners and Managers in the City of Port Angeles, Washington. Available online: https://www.cityofpa.us/DocumentCenter/View/337/Fats-Oil--Grease---Best-Management-Practices-Manual-PDF (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Aguilar-Torrejón, J.A.; Balderas-Hernández, P.; Roa-Morales, G.; Barrera-Díaz, C.E.; Rodríguez-Torres, I.; Torres-Blancas, T. Relationship, Importance, and Development of Analytical Techniques: COD, BOD, and, TOC in Water—An Overview through Time. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, D.; Shaw, L.J.; Collins, C.D. Oil Sludge Washing with Surfactants and Co-Solvents: Oil Recovery from Different Types of Oil Sludges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 28, 5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousset, E.; Oturan, M.A.; Van Hullebusch, E.D.; Guibaud, G.; Esposito, G. Soil Washing/Flushing Treatments of Organic Pollutants Enhanced by Cyclodextrins and Integrated Treatments: State of the Art. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 44, 705–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiyani, K.L.; Wate, S.R.; Joshi, S.R. Solubilization of Hydrocarbons from Oil Sludge by Synthetic Surfactants. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1993, 56, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zeng, G.; Huang, D.; Yang, C.; Lai, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y. Tween 80 surfactant-enhanced bioremediation: Toward a solution to the soil contamination by hydrophobic organic compounds. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisterna-Osorio, P.; Arancibia-Avila, P. Comparison of Biodegradation of Fats and Oils by Activated Sludge on Experimental and Real Scales. Water 2019, 11, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN ISO 15705:2003-01; Wasserbeschaffenheit—Bestimmung des Chemischen Sauerstoffbedarfs (ST-CSB)—Küvettentest (ISO_15705:2002). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Riehm, D.A.; Rokke, D.J.; Paul, P.G.; Lee, H.S.; Vizanko, B.S.; McCormick, A.V. Dispersion of Oil into Water Using Lecithin-Tween 80 Blends: The Role of Spontaneous Emulsification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 487, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).