Abstract

Hemp (Cannabis sativa) seed oil is recognized as a valuable oil due to its beneficial fatty acid profile, which includes a favorable balance of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids, making it highly desirable for edible and bioproduct applications. Crude hempseed oil contains high concentrations of chlorophyll, carotenoids, and other amphiphilic compounds that can negatively affect its appearance, stability, and downstream processing. Therefore, bleaching is a crucial step in removing these pigments after the degumming and neutralization processes. To optimize the bleaching process, a Box–Behnken response surface methodology was employed, focusing on three factors: time (15, 30, 45 min), temperature (100, 120, 140 °C), and bleaching earth concentration (2.5, 5, and 7.5% w/w). The key response variables were β-carotene, chlorophyll content, and antioxidant activity. For chlorophyll removal, bleaching earth concentration accounted for 83.82% and 81.84% of the variation in the solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oils, respectively. For β-carotene, the bleaching earth concentration accounted for over 93% of the variation in both types of oil. The optimal bleaching earth concentrations were determined to be 4.87% and 5.36% for the solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oils, respectively, to achieve the target chlorophyll level of ≤150 ppb. Mechanically extracted oil had lower antioxidant activity after bleaching compared to solvent-extracted oil. The addition of bleaching earth, up to 5%, removed polar antioxidants, further lowering the oil’s antioxidant capacity. These findings suggest that optimizing bleaching conditions can significantly affect both pigment removal and the antioxidant profile of the final product.

1. Introduction

Growing concerns over climate change, pollution, and unsafe consumer products have driven a boom in renewable alternatives. In recent decades, efforts to produce fuel, chemical, and bioproducts from renewable sources have increased significantly [1]. Vegetable oils are commonly used to produce bioproducts such as fuel, cosmetics, and composite materials [2]. These oils, typically derived from fruits or seeds, consist mainly of triglycerides. Common sources of these oils include palm, soybeans, sunflower, canola, and corn [3]. However, these crops are usually grown on highly productive lands reserved for food production. Expanding the use of vegetable oils requires alternatives that will not compete with food-grade oils and can thrive on marginal- or low-productivity land.

Hempseed oil, extracted from industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.), offers great potential. Hemp is a hardy plant which is resistant to drought, heat, cold, and flooding [4]. It grows well in poor soil, outcompetes most other plants, and requires no herbicide. Hempseed contains about 30% oil by weight [5], with yields as high as 0.95 t ha−1 [6]. The high yield makes hempseed oil a potential emerging vegetable oil for food and other applications. Its highly unsaturated composition makes it an ideal feedstock for biofuels and bioresins. Despite its promise, hempseed oil faces unique challenges associated with its processing. The bitter taste limits market acceptance as a food grade oil. Additionally, high chlorophyll concentration, while not a concern in medicinal and cosmetic applications, poses a problem for biofuels and bioproducts due to chlorophyll’s role as a photo-oxidizer and catalyst poison [7]. Hempseed oil also contains small amounts of trace metals which can cause catalyst poisoning in downstream processes. It is important to remove these impurities by bleaching the hempseed oil before its use in different applications. In addition to chlorophyll and metals, other major impurities like free fatty acid and phospholipids are primarily removed during the degumming and neutralization process. This process was used in a previous study which showed that impurity levels significantly varied depending on the extraction method used [8]. The study showed that there was a higher concentration of phospholipids in the solvent-extracted oil than in the mechanically extracted oil; meanwhile, there was a higher concentration of pigments in the mechanically extracted oil than in the solvent-extracted oil. Both chlorophyll and phospholipids are polar compounds which adhere to bleaching earth; hence, there is a need to further compare the bleaching process. These extraction types are usually achieved through the use of a screw press (mechanical) and/or a solvent extractor.

In addition to chlorophyll, there are other pigments and antioxidants that are naturally present in hempseed oil. These include carotenoids, tocopherols, sterols, and phenols. These compounds provide the oil with a natural defense against free radical chain oxidation [7]. Preserving these compounds is not always possible, especially if the oil goes through a high-heat treatment such as deodorizing. However, it is well established that over-processing during oil bleaching can remove these compounds and lower the quality of the final oil [7]. The bleaching process involves exposing the oil to an adsorbent called bleaching clay. Bleaching clay comes in many varieties that vary in pore size, pH, grain size, and area per unit mass. These factors indicate the availability of the adsorbent binding sites to adhere to polar compounds in the oil. To avoid over-bleaching an oil, it is critical to optimize each oil, since the minor components of each oil vary widely.

Hempseed oil is a novel oil in terms of large-scale commercial applications. Hence, few studies exist on hempseed oil refining, bleaching, and deodorizing methods because of hemp’s long prohibition in the western world. Studies that do exist focus on niche processes that are not industrially applicable or lack comprehensive optimization. One study compared the fatty acid profile and free fatty acid concentration of hempseed oil after bleaching with various adsorbents [9]. Another study used ultrasound-assisted bleaching to monitor peroxide and chlorophyll concentration [10]; meanwhile, another evaluated antioxidant degradation post-bleaching [11]. No study has fully optimized the bleaching process for both mechanically extracted and solvent-extracted hempseed oil. Additionally, silica gels can be used in conjunction with bleaching clays to trap contaminants and refining [7]. Silica gels function similarly to bleaching earth by absorbing unwanted compounds, but they offer the additional benefit of selectively removing polar contaminants, such as trace metals, peroxides, and phospholipids, which may not be fully eliminated by bleaching earth alone. However, the use of silica gel, particularly at low concentration, may not sufficiently reduce pigment levels [12]. Little work has been performed in examining the effect of silica gels on the antioxidant activity of vegetable oils during bleaching.

Considering the aforementioned characteristics of hempseed oil, this study aims to optimize the bleaching conditions for mechanically extracted and solvent-extracted hempseed oil, with two subobjectives: (1) using response surface methodology to optimize bleaching earth based on chlorophyll, β-carotene concentration, and antioxidant capacity; and (2) examining the effects of using R92 and R40F silica gel as additives in combination with bleaching earth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The whole hempseeds and hempseed oil were obtained from Healthy Oilseeds, LLC (Carrington, ND, USA). Hexane, methanol, and ethanol were purchased from VWR (Radnor, PA, USA). Sodium hydroxide was purchased from EMD Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA). Citric acid powder was obtained from Chempure Chemicals (Westland, MI, USA). Activated bleaching earth (Select FF) and silica gel (R90 and R40F) were obtained from Oil Dri (Chicago, IL, USA) and Sorbsil (Joliet, IL, USA), respectively. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Mechanical and Solvent Extraction of Hempseed Oil

Hempseed was mechanically pressed at Healthy Oilseeds LLC in Carrington, ND, using a double KOMET screw expeller (IBG Monforts Oekotec GmbH & Co., Mönchengladbach, Germany) with nitrogen cooling to produce crude hempseed oil. The cold-pressed crude hempseed oil was received without any conditioning before undergoing chemical refining (degumming and neutralization). As healthy oilseed lacks solvent extraction capabilities, the solvent extraction of hempseed oil was conducted in our lab using the same feedstock from Healthy Oilseed LLC.

Before extraction, whole hempseeds (at 9.1% moisture content, wet weight basis) were flaked using a Roskamp Model K 5 hp roller mill and then passed through a roller gap of approximately 0.5 mm to increase the contact between the oil bodies and the solvent. Approximately 600 g of seed was placed in a 110 mm × 300 mm porous thimble, which was then positioned in a Soxhlet extraction chamber. Approximately 8 L of hexane was added to a 12 L round-bottom flask, and the Soxhlet apparatus was heated on a Glas-col aluminum heating mantle controlled by a voltage regulator set at 95% (equivalent to 360 °C). Each thimble underwent extraction for approximately 8 h. After extraction, excess hexane was removed by heating the Soxhlet (flask) between 80 and 100 °C. Trace hexane was eliminated using an IKA RV8 rotary evaporator with a water-cooled condenser by heating the oil to 70 °C in a 250 mL round-bottom flask under a 55 kPa vacuum at 85 rpm for 1 h.

2.3. Degumming and Neutralization

The oil was refined (degummed and neutralized) in 1.2 kg batches. The crude oil was heated to 65 °C and homogenized with 0.3% (w/w) concentrated citric acid 50% (w/w) using an Ultra-Turrax high-shear homogenizer at 10,000 rpm for 30 s. It was then neutralized with NaOH at a ratio of 5.5 mL NaOH g−1 of citric acid. After neutralization, the oil was cooled to 50 °C, and 2% (m/m) distilled water was added to further promote flocculation and washing, before being mixed for 15 min at 10,000 rpm. The oil was centrifuged at 4200 rpm using a Jouan CR 412 (Radnor, PA, USA), then decanted into amber glass bottles with 15% (w/w, of oil) magnesium sulfate for overnight drying. Finally, the oil was vacuum-filtered through a Whatman #4 filter in a Büchner funnel and stored at 3 °C until analysis.

2.4. Bleaching of Degummed Hempseed Oil

The degummed hempseed oil was bleached using a rotary evaporator (IKA, RV8, Wilmington, NC, USA) with an oil bath heated to 100–140 °C, using vegetable oil as the bath-heating medium. The oil was preheated in a 500 mL boiling flask at 35 rpm for 5 min before a premeasured amount of bleaching earth was added. A vacuum of 20 inHg was applied, and the oil was heated for the designated time according to the design of experiment (DOE), as shown in Table 1. After bleaching, the oil was filtered through Whatman #4 filter paper and stored at 3 °C in amber glass bottles.

Table 1.

Bleaching conditions for both solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oil according to the Box–Behnken experimental design output from JMP Pro 17.

This paper also explored the treatment of hempseed oil using a combination of silica gel and bleaching earth. The hempseed was bleached at 120 °C for 15 min with a constant treatment of 5% bleaching earth. A silica gel additive was simultaneously added to the oil with the bleaching earth at three concentrations (0.050, 0.125, 0.200%) to remove additional contaminants from the oil. Two types of silica gel were utilized: one variety was enhanced with citric acid (R92) and the other variety contained only silica gel (R40F).

2.5. Experimental Design

The factors and levels for the experimental design are presented in Table 1. This DOE was executed for both mechanically extracted and solvent-extracted hempseed oil. Key response variables, such as chlorophyll concentration, β-carotene concentration, antioxidant activity, and the red yellow blue and neutral (RYBN) color profile, were measured to assess and compare the quality characteristics of the bleached oil samples. In this study, 15 runs were performed for each extraction group, totaling 30 runs. High, medium, and low levels were selected for three factors: temperature (140, 120, 100 °C), time (45, 30, 15 min), and bleaching earth mass [7.5, 5, 2.5% (w/w)].

The experimental design, shown in Table 2, compared two key factors: silica gel amount and type, and extraction method. The experiment was performed at 120 °C for 15 min.

Table 2.

Experimental design showing the bleaching experiment with each additive silica gel treatment.

2.6. Oil Analysis

2.6.1. Peroxide Value and Volatile Compound Mass

Peroxide values were measured photometrically using a CDRFoodLab Jr. (Florence, Italy) with oil and fats peroxide value kits, valid within 1–50 mEq kg−1 and precise to 0.1 mEq kg−1 [13]. Volatile content was determined gravimetrically using an oven-drying method, where 0.5 g of hempseed oil was heated to 75 °C for 5 h to evaporate residual hexane or moisture, followed by a final mass measurement.

2.6.2. RYBN Chlorophyll and β-Carotene

The color of bleached and refined oil was analyzed using a Lovibond Model Fx spectrophotometer, following the AOCS RYBN Chlorophyll and β-Carotene scale (AOCS method Cc 13e-92). Oil samples were analyzed in 10 mm plastic cuvettes at 25 °C, with duplicate measurements taken to determine standard deviation. To assess bleaching efficacy, the percentage removal of chlorophyll and β-carotene was calculated using Equation (1). Adsorbent capacity (Equation (2)) is a reliable metric at lower bleaching earth concentrations, where the pigment–bleaching earth ratios exhibit near-linear trends [14].

2.6.3. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity of bleached and chemically refined oil was assessed using a UV spectrophotometer and a 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) optical assay [15]. This assay simulates free radical oxidation, where the DPPH radical reacts with antioxidants, causing a color change from deep purple to light yellow. Approximately 1 mL of 99% methanol was added to 0.05 g of oil in a microcentrifuge tube, vortexed for 30 s, and the polar fraction was transferred to methanol. A measure of 0.125 mL of the extract was then added to a microplate along with 0.125 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH solution, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a Tecan Infinite 200 Pro UV Visible Spectrometer (Männedorf, Switzerland) for 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min.

The percentage of inhibition was calculated after the reaction had reached steady state. The percentage inhibition was measured as a function between two sets of blanks. The first blank was a 1:1 mix of 99% methanol and 95% ethanol without DPPH (AO) and the second blank was a 1:1 mix of 99% methanol and the DPPH solution (AB). These blanks were compared to the sample extracts with DPPH solution added (AS). Using Equation (3), the percentage of inhibition of DPPH was calculated as a function of the change in DPPH. The percentage of inhibition was then compared to the crude samples to calculate the change in inhibition using Equation (4).

2.6.4. Oxidative Stability Index (OSI)

OSI was determined in triplicate or duplicate, depending on sample availability, using a Rancimat 743 (Metrohm, Ltd., Riverview, FL, USA) according to AOCS Official Method Cd 12b-92. Each crude, refined, and bleached hempseed oil sample (5.0 ± 0.1 g) was evaluated at 100 °C. Results are reported as the mean oxidation time (h) ± standard deviation.

2.6.5. Element Analysis

Oil samples were diluted gravimetrically 1:10 in PremiSolv (SCP Science, Baie D’Urfe, QC, Canada) and analyzed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) (Perkin-Elmer 7000DV, Shelton, CT, USA). Samples were analyzed for calcium, magnesium, and iron according to American Oil Chemists Society (AOCS) official method Ca 17-01. Five-point calibration curves were created from external 1000 ppm standards (Conostan, SCP Science). An independent verification sample was prepared and tested before and after all samples. All determinations were performed in triplicate. The concentration was calculated using peak area with seven peaks per point. Analyses were performed at 1450 Watts with a radial view. Nebulizer flow was high (5.0 L min−1) for the phosphorus analysis and normal (1.0 L min−1) for the other elements. Phosphorus concentration was determined following the AOCS Official method Ca 20-99.

2.6.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 17 (Cary, NC, USA) with a significance level of 0.05. The JMP RSM design interface was utilized to create the Box–Behnken design, generate the analysis of variance (ANOVA) tables, and develop response surface models to evaluate the effects of the bleaching parameters based on the factors and levels in Table 1 and Table 2.

3. Results

3.1. Hempseed Oil Quality Parameters

When evaluating the degree of bleaching in hempseed oil, the quality metric depends on the intended use. The color profile and pigment concentrations of the refined and bleached hempseed oil are compared to commercially refined canola oil, as shown in Table 3. These values represent the average across the different bleaching parameters. While there is noticeable difference in the color profile of the two hempseed oils, both were bleached (without deodorization) to the pigment and color levels comparable to those of common refined bleached and deodorized oils, like canola oil.

Table 3.

Color and pigments of the hempseed oil (refined and bleached) and a common refined bleached and deodorized vegetable oil. Hempseed oil was bleached at 100 °C for 15 min with 5% bleaching earth. Matching superscript letters indicate no significant difference according to a pairwise test of significance using Tukey’s method at a 95% confidence interval.

Chlorophyll, a photo-oxidizer and catalyst poison, can affect the oil quality and reduce chemical conversion yields. The initial chlorophyll concentration of the crude or refined oil was dependent on the extraction method, and intra-process conditions can cause variation in the final chlorophyll concentration. During the mechanical press extraction, the chlorophyll-rich hull of the hempseed is exposed to high pressure and temperature, which can result in better extraction of the chlorophyll when compared to gentler solvent extraction [8,16]. The typical residual chlorophyll concentration in commonly bleached oils is ≤150 ppb [17]. The solvent-extracted hempseed oil initially contained 11,391 ppb of chlorophyll, requiring 98.7% reduction to reach the target level. Chlorophyll removal varied from 94.6% to 99.7% in these samples. Mechanically extracted hempseed oil had an initial chlorophyll concentration of 17,487 ppb, requiring a 99.2% reduction to reach the same target level. While achieving chlorophyll levels below 150 ppb is desirable, excessive bleaching can negatively affect oil stability, reduce antioxidant concentration, and increase the absorbent cost [7,17]. Therefore, it was important to balance chlorophyll removal with the preservation of beneficial compounds, ensuring longer shelf life.

3.2. Chlorophyll and β-Carotene Removal Model Development

Due to the significant differences in quality parameters between the solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted hempseed oils, optimization was conducted separately for each extraction type using a Box–Behnken experimental design. Box–Behnken designs are efficient tools for response surface methodology, requiring fewer runs than other methods like central composite design [18]. Table 4 shows the analysis of variance used to test the significance (p-value < 0.05) of the factors and interactions. Since the adsorption mechanism in vegetable oil bleaching is identical in both extraction methods, it was assumed that the models would have overlapping significant variables. The assumption helps to identify significant terms for a theoretical overall model for the removal of each pigment.

Table 4.

Backward-reduced ANOVA of chlorophyll and β-carotene removal of bleached hempseed oil. Temperature, X1; time, X2; bleaching earth amount, X3.

Firstly, the ANOVA in Table 4 shows chlorophyll removal during bleaching with each factor: temperature in °C (X1), time in minutes (X2), bleaching earth as a percentage of oil mass (X3), and significant interaction and quadratic terms. The largest source of variation in chlorophyll removal was bleaching earth (X3), accounting for 70.48% and 64.43% in solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oil, respectively. Additionally, the quadratic term () accounted for an additional 13.34% and 17.41% of variation for solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oils, respectively. Together, bleaching earth alone contributed to 83.82% and 81.84% of the variation in chlorophyll removal for solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted hempseed oil, respectively. The remaining factors accounted for an additional 12.01% or 11.11% of chlorophyll removal. While time (X2) was not strongly associated with changes in chlorophyll concentration, this may be due to the limited range of the levels chosen. Consequently, the shortest time of 15 min was deemed optimal to prevent excessive oxidation. The terms for bleaching earth (X3 and ), temperature (X1), and the interaction between temperature and bleaching earth (X1X3) were significant and retained in the model.

Combining the significant sources of variation from both ANOVAs in Table 4 produced two reduced models, as shown in Equations (5) (solvent extracted) and (6) (mechanically extracted). These equations predict the residual chlorophyll concentration in hempseed oil after bleaching based on conditions outlined in the methodology. Significant terms were retained in both models.

The model for solvent-extracted oil was highly significant with an R2 and adjusted R2 of 0.95 and 0.92, respectively. Meanwhile, the mechanical extraction model had values of 0.92 and 0.88, respectively. These coefficients of determination suggest the models account for 95% and 92% of the variation in chlorophyll concentration for solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oil, respectively. The remainder of the variation could be from other factors that cannot be explained by the model, as well as inherent variability in the measurements of the pigment concentrations. The average standard deviation of chlorophyll measurements was ±32 ppb across duplicates. This corresponds to a standard deviation of ±0.28% for the solvent-extracted oil and ±0.18% for the mechanically extracted oil.

Table 4 also shows the ANOVAs of β-carotene removal during bleaching. It is important to note that β-carotene removal is not always desirable, as this compound is a dietary antioxidant linked to various health benefits [19]. β-carotene does not act as an antioxidant in lipids, though it may paradoxically act as a prooxidant at high temperatures [20,21]. In the β-carotene removal ANOVAs, the largest source of variation was also shown to be the amount of bleaching earth (), accounting for 89.51% and 84.38% in solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oils, respectively. The quadratic term () accounted for 3.51% and 9.51% of variation, respectively. Together, the variability in the bleaching earth explained 93.02% and 93.89% of the variation in β-carotene removal. Although time and temperature were not strongly associated with β-carotene concentration differences, they are significant factors if the levels were wider than those used in this study. Significant bleaching earth terms (X3 and ) and the interaction between temperature and bleaching earth (X1 X3) were retained in the model. Since the interaction between temperature and bleaching earth was significant, even though the main temperature effect was not significant, the main temperature term (X1) was included in the model. Combining the significant sources of variation from both ANOVAs produces two reduced models, as shown in Equations (7) (solvent extracted) and (8) (mechanically extracted).

The solvent extraction model was found to be highly significant, with R2 and adjusted R2 values of 0.96 and 0.94, respectively. Similarly, the mechanical extraction model showed R2 and adjusted R2 values of 0.95 and 0.94, respectively. These coefficients of determination suggest that the factors in the statistical model explain 96% and 95% of the variation in β-carotene concentration for solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted hemp oils, respectively. There was inherent variability in pigment concentrations measurements, reflected by an average standard deviation of ±321 ppb of β-carotene across all samples. This corresponds to a standard deviation of ±0.63% for the solvent-extracted oil and ±0.53% for the mechanically extracted oil in terms of β-carotene removal.

3.3. Total Pigment Removal

Since bleaching involves complex adsorption kinetics, it is important to view the process as interactions between the binding sites and the two key adsorbates: chlorophyll and β-carotene. Chlorophyll levels should be reduced to ≤150 ppm, while β-carotene can either be retained or removed depending on the final product’s requirements. The mass of bleaching earth was the largest source of variation in the process, making it the primary variable to adjust when optimizing the model. When comparing the ideal conditions for bleaching earth across the two extraction methods, an interesting trend becomes clear, as shown in Table 5. Mechanically extracted oil exhibited a higher adsorption capacity for both chlorophyll and β-carotene compared to solvent-extracted oil. This is attributed to higher initial pigment concentration in mechanically extracted hempseed, which increases the final equilibrium adsorption capacity [22]. Additionally, the higher concentration of polar molecules such as phospholipids in the solvent-extracted oil would have competed with the pigments for the available adsorption sites [8].

Table 5.

Adsorbent capacity for the pigments measured per gram of adsorbent at 100 °C for 15 min.

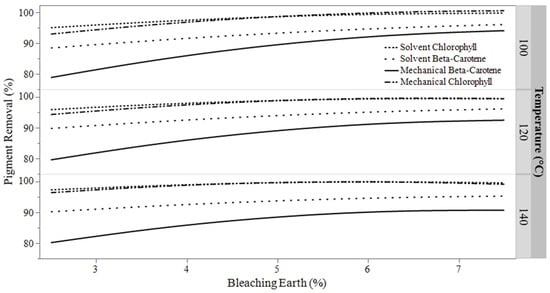

This effect led to greater variation in β-carotene removal compared to chlorophyll, resulting in proportionally larger changes in β-carotene concentration when the amount of bleaching earth is varied. While temperature can also influence pigment levels, its effect is much smaller compared to the impact of varying bleaching earth. This relationship between the factors is illustrated in the pigment removal plot shown in Figure 1. Solvent-extracted oil had initial pigment concentrations of 11,391 ppb chlorophyll and 50,661 ppb β-carotene. Mechanically extracted oil had initial pigment concentrations of 17,487 ppb chlorophyll and 60,642 ppb β-carotene.

Figure 1.

Combined pigment removal of hempseed oil from bleaching conditions and extraction type.

β-carotene removal showed a counterintuitive trend of reduced pigment removal at higher temperatures. To explain this phenomenon, the nature of adsorption must be considered. Adsorbates, such as β-carotene, can be physically removed from an adsorbent when the activation energy threshold is exceeded through added heat, a process known as desorption [23]. The desorption of β-carotene becomes problematic at higher bleaching temperatures, as the increased energy of the adsorption system can lead to greater desorption. This suggests a relationship between bleaching temperature and the binding capacity of the absorbent, which affects the total desorption of the β-carotene. If β-carotene is desorbed from the bleaching earth, then it is possible that other pigments, such as chlorophyll, could replace them in a phenomenon known as competitive adsorption [24]. The response curves in Figure 1 show β-carotene adsorbing less effectively at higher bleaching temperatures in both oils, indicating that desorption may have occurred.

The percentage of chlorophyll removal and concentration of β-carotene were estimated based on the amount of bleaching earth required to achieve the target chlorophyll concentration of 150 ppb. The masses of bleaching earth required to reach a residual chlorophyll concentration of 150 ppb and residual β-carotene concentrations at these different bleaching conditions are summarized in Table 6. Although higher temperatures can influence pigment concentration removal, the lowest temperature of 100 °C and time of 15 min were selected to minimize lipid oxidation, reduce costs, and increase throughput. At these temperatures and durations, the model’s prediction profiler in JMP showed that 4.91% bleaching earth met the chlorophyll removal target (98.7%) for solvent-extracted oil, while 5.33% was needed for mechanically extracted oil (99.2%).

Table 6.

Chlorophyll removal (%) for the bleached hempseed oil.

Low variation in time and temperature factors does not imply their insignificance for pigment removal. This is because temperatures between 100 °C and 140 °C and times between 15 and 45 min were within the optimal ranges for hempseed oils, but values outside these ranges would likely affect chlorophyll concentration. Studies with wider range in these factors have shown significantly decreased pigment concentration [25]. Acid-activated bleaching clays, commonly used as adsorbates for their silicate structure, bind chlorophyll and β-carotene via Van der Waals’ forces and electrochemical adsorption [26]. High temperatures promote deeper migration of pigments into the clay structure, improving bleaching efficiency and reducing the required mass of bleaching earth. However, careful optimization is essential: one must balance costs and resources in continuous bleaching systems, since chlorophyll exhibits the highest affinity for bleaching earth at higher temperatures.

3.4. Antioxidant Activity of Bleached Hempseed Oil

The effectiveness of the hempseed oil bleaching process can also be evaluated by the impact on natural antioxidants under the different bleaching conditions. Instead of measuring individual antioxidative compounds throughout the bleaching process, overall antioxidant activity was measured using 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), which reacts with the antioxidants in the oil. The ANOVA in Table 7 identifies three of the four factors that significantly affect the antioxidant activity of the oil post-bleaching. The extraction method was the most significant factor (p-value < 0.0001), accounting for 82.63% of the variation in antioxidant activity. Temperature (p-value = 0.0002) accounted for 8.82%, and bleaching earth concentration (p-value = 0.0422) accounted for 2.22%. Time was not a significant factor (p-value 0.5739). The adjusted R2 of the model was 93%.

Table 7.

The analysis of variance for the change in antioxidant activity.

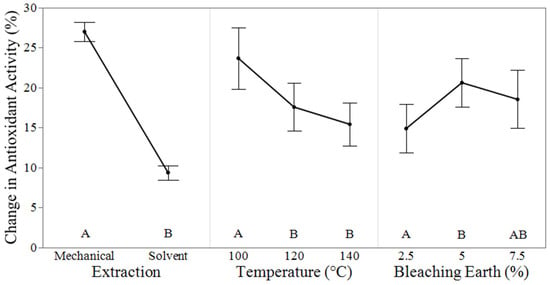

The main effect plots in Figure 2 illustrate the trend of antioxidant activity across different bleaching conditions, with the extraction method playing a key role in determining the final antioxidant activity. The antioxidant activity of the solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted crude oils was similar at 82.5 ± 2.1% and 86.0 ± 1.5%, respectively. However, the antioxidant activity of mechanically extracted oil decreased 2.9 times more during bleaching compared to solvent-extracted hempseed oil. Studies on the impact of extraction methods on antioxidant activity at high temperatures suggest that phenolic antioxidants are more heat-stable than tocopherols [27,28]. Among the tocopherols, γ-tocopherol has been shown to have stronger antioxidative effects at high temperatures than α-tocopherol [29]. The selective extraction of these stable antioxidants into the solvent-extracted oil may explain the difference between the two extraction methods. While pigments such as chlorophyll and β-carotene are not known to have a large effect on the antioxidant activity of oils, chlorophyll may act as a catalyst in the formation of hydroperoxides which can lower the antioxidant activity of the oil [7]. This is especially seen in mechanically extracted oil which had higher concentrations of photo-oxidizing chlorophylls.

Figure 2.

The main effect plots for the change in antioxidant activity (%) at different bleaching conditions when time was held constant for 10 min where lower change in activity signifies increased antioxidant activity. Different letters indicate a significant difference between levels via Tukey’s test at CI = 95%.

As the bleaching process temperature increases, the antioxidant activity of the bleached oil also increases compared to the refined baseline. This increase results in a lower change in the antioxidant activity, as seen in Figure 2. Hempseed oil contains approximately 70% of polyunsaturated fatty acids, mostly 18:2 (linoleic) and 18:3 (linolenic), and the double bonds act as a starting point for free radical oxidation. Primary and secondary oxidation products in vegetable oil promote additional free radical oxidation, before decomposing into volatile compounds [30,31]. At elevated temperatures, hydroperoxides decompose, reducing the peroxide value and limiting the formation of free radicals. This reduction in peroxides prevents antioxidants from being deactivated by free radicals, resulting in a relative increase in antioxidant activity, and decrease in change in antioxidant activity (%), compared to other bleaching samples. Additionally, the oxidation of tocopherols can produce prooxidants, which may be destroyed at high temperatures [32]. These prooxidative compounds are also adsorbed by bleaching earth at elevated temperatures [33]. For the antioxidants remaining in the oil post-bleaching, studies suggest that the bioavailability of compounds like flavonoids and other antioxidants may increase as temperature rises [34,35]. β-carotene, which remains in the oil during low-temperature bleaching, has been shown to reduce antioxidative activity [20]. These combined effects likely explain the unexpected decrease in the change in antioxidant activity at higher bleaching temperatures. Despite the potential for additional oil oxidation at high temperatures, this data shows that high temperatures may be beneficial for the stability of the hempseed oil.

The reduction in antioxidant activity observed with increasing concentrations of bleaching earth is expected. Many antioxidants are polar compounds that are absorbed by the bleaching earth. As more bleaching earth is added, more adsorption sites are available for these compounds. Beyond the 5% bleaching earth concentration, further additions likely have little effect on antioxidant activity, as most polar antioxidants have already been removed.

Bleaching hempseed oil to remove bioactive antioxidants is dependent on the oil’s intended use. For less oxidized oils, low temperature, short-duration bleaching would likely preserve antioxidants [36]. If the oil is to be used as an edible product, higher temperatures and lower bleaching earth amounts would help maintain antioxidant levels at higher pigment retention. For chemical conversion applications, minimizing impurities is essential, so the optimal bleaching conditions would involve 100 °C for 10 min with 4.87% and 5.36% bleaching earth mass for solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oils, respectively. Table 8 shows that refined mechanically extracted oil has higher concentrations of oxidation products, which may produce free radicals that react with antioxidants, promoting further hydroperoxides formation during bleaching.

Table 8.

Peroxide value and volatile content of the solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted hempseed oils that was bleached at 100 °C for 10 min with 5% bleaching earth.

Highly unsaturated unprocessed oils like hempseed oil oxidize quickly and the peroxide value before bleaching was elevated. This indicates that the quantity of bleaching earth required to remove pigments was not sufficient to fully remove hydroperoxides from the oil.

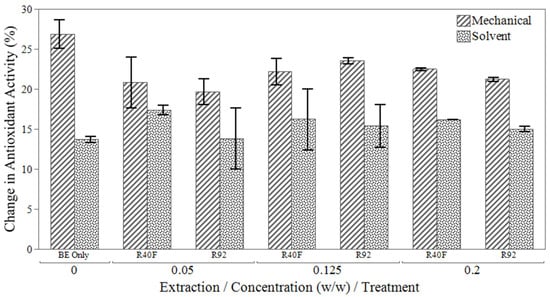

3.5. Effect of Additive Silica Gel on Bleached Earth Quality

The impact of silica gel additives on oil quality during bleaching was evaluated in a separate bleaching experiment. Two silica gels were tested: R40F and R92. The R92 silica gel, enhanced with a citric acid additive, was designed to improve polar compound removal. In all silica gel treated samples, a consistent reduction in antioxidant activity was observed between solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oils in Figure 3. This trend was similar to samples treated only with bleaching earth, likely due to the differing peroxide and antioxidant concentrations in the extraction groups. Figure 3 also shows the R92 treated samples generally exhibited a smaller reduction in antioxidant activity compared to other treatments, except in the 0.125% (w/w) group.

Figure 3.

Change in antioxidant activity after bleaching with a combination of bleaching earth (BE) and different types (R40F and R92) silica gels.

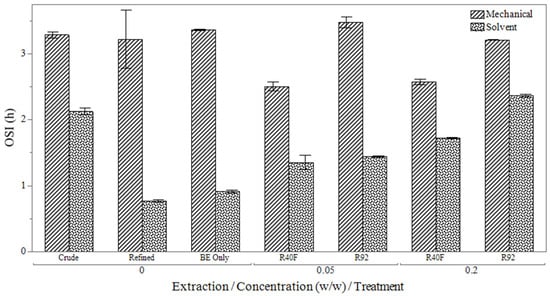

The oxidative stability index (OSI) results, shown in Figure 4, reveal that solvent-extracted oils were less oxidatively stable than the mechanically extracted oil. This finding contrasts with the antioxidant activity trend observed between extraction groups, indicating that the high concentration of oxidation products in solvent-extracted oil likely interfered with the measurement of antioxidant activity. A similar relationship between peroxide value, radical scavenging activity, and oxidative stability was observed in a study by Baydir and Aşçıoğlu [37]. In the solvent-extracted oils, there was a clear trend of increased oxidative stability with higher silica gel concentration, with the R92 silica gel providing superior oxidative stability compared to R40F silica gel. However, in the mechanically extracted group, the addition of silica gel offered little–no benefit in oxidative stability. In some cases, oxidative stability even decreased compared to samples bleached with activated bleaching earth alone (BE only), likely due to the lower presence of trace metal contamination in the mechanically extracted oils, as outlined in Table 9. All targets were undetectable for mechanically extracted oils.

Figure 4.

Oxidative stability index measurements after bleaching with a combination of bleaching earth (BE) and different types (R40F and R92) silica gels.

Table 9.

Trace element analysis for solvent-extracted oils treated with silica gel at 0.2% (w/w) of oil mass.

The results of the silica gel additive experiments indicate that silica gels were not needed for the mechanically extracted oil since the metal levels were undetectable after refining (before bleaching). For the solvent-extracted oil, silica gel treatment was helpful in reducing the high levels of metals still present in the oil, especially phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium. This is likely due to high concentrations of nonhydratable phospholipids extracted with the solvent. Additionally, these nonhydratable phospholipids are difficult to fully remove and will result in an oil with a high phosphorus concentration after refining and bleaching. The R92 silica gel, which contains citric acid, was particularly effective at improving oil quality by further reducing these contaminants compared to the R40F silica gel. However, for mechanically extracted oils, the addition of silica gel often reduced oxidative stability, likely due to the lower contaminant levels present in the initial oil. The most effective concentration for silica gel treatments was found to be 0.2% (w/w) of oil, where it demonstrated the best results for both oil quality and stability.

4. Conclusions

Bleaching is one of the steps in refining vegetable oil, and this study focused on ways to optimize the bleaching process of hempseed oil. Regression models based on a Box–Behnken design of experiment were utilized to optimize bleaching of hempseed oil, focusing on chlorophyll and β-carotene removal. The results showed that bleaching earth was the most influential factor in pigment removal, accounting for over 80% variation for chlorophyll and over 90% for β-carotene. Ideal bleaching conditions in this study were assessed as 100 °C and 15 min, minimizing resource usage. To reach the target chlorophyll concentration of ≤150 ppb, the required amounts of bleaching earth were 4.91% and 5.33% for solvent-extracted and mechanically extracted oil, respectively. β-carotene showed lower affinity for bleaching earth, particularly at higher temperatures of 120 °C and 140 °C, promoting desorption. If maximizing β-carotene or chlorophyll removal is desirable, the study showed that solvent-extracted oil would require less bleaching earth (4.9% compared to 5.3%). In terms of antioxidant activity, mechanically extracted refined oil had lower levels of antioxidant activity compared to solvent-extracted oil. Also, the antioxidant activity increased by 10% as the temperature increased from 100 to 140 °C, likely due to breakdown of prooxidants like hydroperoxides. Addition of up to 5% bleaching earth helped remove polar compounds, which reduced antioxidant activity. However, the addition of 0.2% silica gel, particularly citric-acid-enhanced R92 silica gel, improved the removal of prooxidant trace elements like P, Ca, and Mg to less than 13 ppm. This led to enhanced oxidative stability in solvent-extracted oil, but a limited impact on mechanically extracted oil due to its very low initial contaminant levels.

Author Contributions

P.C.W.: Investigation, methodology, data collection and data analysis, and writing—original draft preparation. M.S.H.: data collection and writing—review and editing; C.L.C.: data analysis and writing—review and editing; R.E.: methodology, data collection and data analysis, and writing—review and editing; S.L.: data collection and writing—review and editing; B.C.: data analysis and writing—review and editing. E.M.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station and USDA-NIFA Hatch multistate ND014891.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Roger Gussiaas from Healthy Oilseeds, LLC in Carrington, ND, USA, for providing hemp oil and hemp grain used in these experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zimmerman, J.B.; Anastas, P.T.; Erythropel, H.C.; Leitner, W. Designing for a green chemistry future. Science 2020, 367, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaramonti, D.; Buffi, M.; Rizzo, A.M.; Lotti, G.; Prussi, M. Bio-hydrocarbons through catalytic pyrolysis of used cooking oils and fatty acids for sustainable jet and road fuel production. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.K.; Tan, K.T.; Lee, K.T.; Mohamed, A.R. Malaysian palm oil: Surviving the food versus fuel dispute for a sustainable future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandinières, H.; Amaducci, S. Adapting the cultivation of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) to marginal lands: A review. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 14, 1004–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriese, U.; Schumann, E.; Weber, W.E.; Beyer, M.; Brühl, L.; Matthäus. Oil content, tocopherol composition and fatty acid patterns of the seeds of 51 Cannabis sativa L. genotypes. Euphytica 2004, 137, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Sefidkon, F.; Calagari, M.; Mousavi, A.; Fawzi Mahomoodally, M. A comparative study of seed yield and oil composition of four cultivars of Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) grown from three regions in northern Iran. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 152, 112397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M. Practical Guide to Vegetable Oil Processing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, P.C.; Monono, E.; Sarker, N.C.; Clementson, C.L.; Evangelista, R.; Winkler-Moser, J.K. Assessing the Refinement Conditions for Mechanical and Solvent Extracted Hempseed Oil. J. ASABE 2025, 68, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golimowski, W.; Teleszko, M.; Zając, A.; Kmiecik, D.; Grygier, A. Effect of the bleaching process on changes in the fatty acid profile of raw hemp seed oil (Cannabis sativa). Molecules 2023, 28, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aachary, A.A.; Liang, J.; Hydamaka, A.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Thiyam-Holländer, U. A new ultrasound-assisted bleaching technique for impacting chlorophyll content of cold-pressed hempseed oil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 72, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśnica, A.; Teleszko, M.; Marcinkowski, D.; Kmiecik, D.; Grygier, A.; Golimowski, W. Analysis of Changes in the Amount of Phytosterols after the Bleaching Process of Hemp Oils. Molecules 2022, 27, 7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, Y.; Kwak, S.-Y. Functional mesoporous silica with controlled pore size for selective adsorption of free fatty acid and chlorophyll. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 306, 110410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.W.; Park, K.-M.; Park, J.W.; Lee, J.; Choi, S.J.; Chang, P.-S. Rapid and Sensitive Determination of Lipid Oxidation Using the Reagent Kit Based on Spectrophotometry (FOODLABfat System). J. Chem. 2016, 2016, 1468743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhas; Gupta, V.K.; Carrott, P.J.M.; Singh, R.; Chaudhary, M.; Kushwaha, S. Cellulose: A review as natural, modified and activated carbon adsorbent. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 216, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuntiwiwattanapun, N.; Monono, E.; Wiesenborn, D.; Tongcumpou, C. In-situ transesterification process for biodiesel production using spent coffee grounds from the instant coffee industry. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 102, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mińkowski, K.; Bartosiak, M.; Ciemiński, D. Effect of Extraction and Refining of Rapeseed Oil on Profile and Content of Chlorophyll Pigments. Zywnosc 2019, 26, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevin, D.; Domijan, T.; Kraljic, K.; Kljusuric, J.G.; Neðeral, S.; Obranovic, M. Optimization of Bleaching Parameters for Soybean Oil. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 50, 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Monono, E.M.; Bahr, J.A.; Pryor, S.W.; Webster, D.C.; Wiesenborn, D.P. Optimizing Process Parameters of Epoxidized Sucrose Soyate Synthesis for Industrial Scale Production. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, K.; Tak, A.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, P.; Yousuf, B.; Wani, A.A. Chemistry, encapsulation, and health benefits of β-carotene-A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2015, 1, 1018696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A.; Murkovic, M. Pro-Oxidant Effects of β-Carotene During Thermal Oxidation of Edible Oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2013, 90, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartee, S.D.; Kim, H.J.; Min, D.B. Effects of Antioxidants on the Oxidative Stability of Oils Containing Arachidonic, Docosapentaenoic and Docosahexaenoic Acids. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007, 84, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutha; Jeppu, G.; Girish, C.R.; Prabhu, B.; Mayer, K. Multi-component Adsorption Isotherms: Review and Modeling Studies. Environ. Process. 2023, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmer, K.; Engewald, W. Adsorbent materials commonly used in air analysis for adsorptive enrichment and thermal desorption of volatile organic compounds. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 373, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gun’ko, V.M. Competitive adsorption. Theor. Exp. Chem. 2007, 43, 139–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.C.; Tan, C.P.; Nyam, K.L. Optimization of bleaching parameters in refining process of kenaf seed oil with a central composite design model. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 1622–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aishat, A.B.; Olalekan, S.T.; Arinkoola, A.O.; Omolola, J.M. Effect of activation on clays and carbonaceous materials in vegetable oil bleaching: State of art review. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.; Knorr, A. An evaluation of antioxidants for vegetable oils at elevated temperatures. Lubr. Sci. 1996, 8, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Shehzad, Q.; Yu, L.; Tian, A.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Zheng, L.; Xu, L. Comparative study on quality characteristics of Bischofia polycarpa seed oil by different solvents: Lipid composition, phytochemicals, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongracz, G. γ-Tocopherol als natürliches Antioxidans. Fette Seifen Anstrichm. 1984, 86, 455–460. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Hahm, T.S.; Min, D.B. Hydroperoxide as a Prooxidant in the Oxidative Stability of Soybean Oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007, 84, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolovich, M.; Prenzler, P.D.; Patsalides, E.; McDonald, S.; Robards, K. Methods for testing antioxidant activity. Analyst 2002, 127, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, T.M.; Kim, H.J.; Min, D.B. Prooxidant activity of oxidized α-tocopherol in vegetable oils. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, C536–C542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, E.; Min, D.B. Mechanisms and factors for edible oil oxidation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2006, 5, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xia, W.; Shao, P.; Wu, W.; Chen, H.; Fang, X.; Mu, H.; Xiao, J.; Gao, H. Impact of thermal processing on dietary flavonoids. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réblová, Z. The effect of temperature on the antioxidant activity of tocopherols. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2006, 108, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strieder, M.M.; Engelmann, J.I.; Pohndorf, R.S.; Rodrigues, P.A.; Juliano, R.S.; Dotto, G.L.; Pinto, L.A.A. The effect of temperature on rice oil bleaching to reduce oxidation and loss in bioactive compounds. Grasas Y Aceites 2019, 70, e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk Baydir, A.; Aşçıoğlu, Ç. Effects of Antioxidant Capacity and Peroxide Value on Oxidation Stability of Sunflower Oil. Kim. Ve Malzeme 2018, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).