Abstract

The coexistence of plastics and metal-based materials in aquatic systems introduces complex interfacial processes that influence pollutant speciation and mobility. This study investigates the role of polystyrene (PS) in promoting UV-induced dissolution of ZnO and Cu2O in aqueous media, revealing a plastic-mediated pathway for metal ion mobilization. Post-use expanded PS fragments were co-dispersed with the oxides and irradiated at 254 nm for 24 h. Ion concentrations were quantified by ICP-MS, while PS morphology and chemistry were characterized by SEM, EDX, FTIR, Raman, and DSC. The presence of PS markedly enhanced metal release, bringing Zn2+ from 29.9 to 50.6 ppm and Cu2+ from 1.1 to 26.5 ppm under irradiation, compared to minimal dissolution in the dark. Spectroscopic analyses indicated negligible polymer degradation, suggesting that enhanced dissolution arises from interfacial photooxidation and associated redox/pH microgradients at the polymer–oxide boundary. These findings demonstrate that PS may serve as a catalytic interface that accelerates UV-driven dissolution of otherwise poorly soluble metal oxides. This mechanism expands current understanding of plastic–pollutant interactions and has implications for predicting metal bioavailability and designing strategies to mitigate pollutant release in sunlit marine and coastal environments.

1. Introduction

The widespread contamination of marine environments by both plastic [1] debris and metals [2], as such or as ions or oxides, presents an emerging and complex environmental threat [3]. Plastic pollution, particularly from persistent polymers such as polystyrene (PS), has reached alarming levels: it is estimated a figure of 4.8 million to 12.7 million tons of plastic enter the oceans each year [4], with PS being one of the most common due to its widespread use in packaging and disposable products [5,6].

PS exists both as macroplastic debris and as microplastic fragments (<5 mm) in the marine environment, resulting from physical, chemical, and biological degradation processes [7,8]. These small particles can float at the sea surface, sink to the seafloor, or remain suspended in the water column, exposing a wide range of marine organisms to potential ingestion and surface-mediated chemical interactions [9]. PS has been identified as a significant contributor to marine plastic pollution, due to its high environmental persistence, buoyancy, and tendency to fragment into microplastics [10]. In response, the European Union adopted Directive (EU) 2019/904 on single-use plastics (commonly referred to as the SUP Directive), which became effective in July 2021 [11]. This legislation specifically bans the placing on the market of certain PS-based food and beverage containers, recognizing their prevalence in marine litter and the risks they pose to marine ecosystems, a concern not yet addressed with comparable regulatory action in many other regions globally.

Simultaneously, metals and metal-based compounds, including metal oxides such as ZnO, CuO, and Cu2O, enter marine systems through various anthropogenic sources [12]. For example, Cu2O is used in antifouling paints applied to ship hulls and underwater structures [13]; also, CuO counters biofouling and is used for membranes in water treatment [14]. ZnO is commonly found in sunscreens and cosmetics, and also in antifouling paints [15,16]. The widespread use of antifouling paints containing metal-based biocides raises increasing environmental concerns due to their potential release of Cu+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions into marine ecosystems [17]. Although these oxides are typically considered nontoxic due to their very low solubility in seawater [18,19], environmental variables such as pH or salinity changes, organic matter interactions, and especially solar radiation can alter their chemical behavior, leading to the release of free metal ions, such as Zn2+ [20,21], Cu+ and Cu2+ that are toxic species [22]. Such species are highly bioavailable, and their accumulation can cause severe ecotoxicological effects [23,24], including enzyme inhibition, oxidative stress, and disruption of membrane functions in marine organisms [25]. Copper and zinc ions are reported to be toxic to a wide range of non-target organisms, including algae, zooplankton, and invertebrates, even at low concentrations [26,27]. Given their ecotoxicological impact, regulatory bodies and various national environmental agencies are actively promoting the development and gradual transition toward copper-free antifouling technologies [28], encouraging formulations based on less harmful compounds or non-biocidal approaches (e.g., foul-release coatings) [29]. A copper ion release rate from 3.6 to 10 mg/cm2/day is typically considered necessary to ensure the efficacy of marine coatings against the attachment of common fouling organisms [30]. Instead, the amount of zinc ion released from the antifouling paints ranged approximately from 5 to 11 mg/cm2/day, but, although ZnO is primarily used in antifouling paints to regulate coating erosion, provide UV protection, and act as a pigment, the regulatory frameworks treat it differently than copper-based biocides [31]. In the US, the prescriptive focus remains primarily on copper-based paints: the Environmental Protection Agency sets national limits on copper release from coatings (9.5 mg/cm2/day) [32]; there are no specific federal restrictions targeting zinc oxide content or release rates in marine coatings because it is included as a co-formulant. Unlike the US, the European Union has not set such quantitative thresholds; instead, it requires that leaching rates of the active biocide (copper) remain ‘the minimum necessary’ to ensure efficacy, as assessed through data provided by manufacturers and evaluated within the product authorization process [33]. Instead, ZnO is not classified as an active biocidal substance under Biocidal Products Regulation (BPR) [33], but it is regarded as a ‘Substance of Concern’, due to its potential environmental release and toxic effects (e.g., accumulation of Zn2+ in water or sediments). Consequently, the antifouling products containing ZnO must undergo environmental risk assessments, even if there is no explicit ban on ZnO in the European Union. The International Maritime Organization promotes the transition to more sustainable antifouling strategies, at a global level [28,29].

In recent years, plastic–metal interactions have emerged as a key area of concern [34]. Microplastics can act as carriers for pollutants [35], adsorbing metals [36] and other toxic substances on their surfaces. However, beyond simple adsorption, plastics may also facilitate the transformation of insoluble metal oxides into their soluble and toxic ionic forms [34]. UV radiation can trigger photochemical reactions that modify plastic surfaces, adding new oxygenated functional groups able to interact with metal oxides [37]. To our knowledge, there is only one experimental work reporting the dissolution of ZnO nanoparticles, as Zn2+, in buffered solution or in freshwater, in the presence of PS and sunlight irradiation [5]. Nonetheless, it is crucial for chemical and environmental engineering to comprehend these interactions because they could influence the design and degradation behavior of coatings, pigments, and functional materials in real-world conditions.

Transition metals, as ions, oxides, or nanoparticles, and their interaction with the aqueous environment, have been the focus of our work for many years [38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. The present study investigates the UV-driven PS-enhanced dissolution of ZnO and Cu2O into zinc and copper ions, even in the absence of significant degradation of PS. This research aims to demonstrate the potential occurrence of indirect ecotoxicity in marine systems, an aspect scarcely investigated to date, and to understand the plastic-mediated photochemical processes relevant to environmental engineering, particularly in assessing metal ion mobility and in developing strategies to mitigate pollutant release in marine systems.

2. Materials and Methods

Post-use foamed PS was a gift from a local logistics company; it exhibits high porosity and a broad pore-size distribution, and its typical molecular weight is in the range of 160,000–260,000 g·mol−1 [45]; all reagents were purchased from Merck and used as received. PS was ground to powder in a ceramic mortar. 20 mg of ZnO powder or Cu2O powder were added to 10 mL of distilled water with or without PS (20 mg), and irradiated with UV light (λ = 254 nm) for 24 h in open-air quartz-tubes of 15 mL of volume under stirring (1200 rpm). No changes were observed in the aqueous solution or in the suspension. Control samples were kept in the dark. At the end, water samples were filtered by filter paper, and the solid was washed with water. The aqueous samples were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to quantify the concentration of zinc and copper as Zn2+ and Cu2+ ions.

PS was also characterized by SEM, Raman, FTIR, and DSC to assess potential degradation or surface modifications.

A photochemical multiray apparatus (Helios Italquartz; Milano, Italy) was used for photoirradiation of the mixtures; the apparatus is equipped with 10 low-pressure Hg lamps (nominal electrical power consumption: 15 W per lamp, total consumed power 150 W), emitting mainly at 254 nm. Transparent quartz vials (15 mL, placed at around 10 cm of distance from lamps) were used for irradiation of the suspensions.

Thermal analyses were performed using a TA Instruments thermal analyzer (Discovery DSC2500, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE 19720, USA). Samples were heated from 25 °C to 400 °C. DSC experiments were performed by cooling the sample from 400 °C to 25 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min. The entire procedure was repeated to ensure reproducibility. The thermal behavior of PS and PS-metal oxides was evaluated by determining the main transition temperature (Tm) and the transition enthalpy (ΔHm) expressed as J/g of PS in the sample.

The morphological and microstructural analyses of samples before and after the UV treatment were performed using a Phenom XL Desktop Scanning Electron Microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), equipped with an integrated Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) detector. Prior to SEM analysis, PS samples were dried in a laboratory oven at 40 °C to remove residual moisture without inducing thermal deformation or morphological rearrangements. No solvents were used during drying, minimizing the risk of surface collapse or solvent-induced artefacts. After drying, the samples were mounted on aluminum SEM stubs using conductive carbon adhesive tape. To further limit charging effects under the electron beam, a thin carbon coating was deposited by sputtering under vacuum. Carbon sputtering was selected in preference to metal coatings to preserve surface features and avoid masking fine morphological details. Images were carried out at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV under 0.1 Pa. Image acquisition and analysis were performed using the Phenom ProSuite software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) provided with the instrument. Elemental analysis and mapping were obtained using the EDX detector integrated into the Phenom XL system, operated through the ProSuite and Element Identification (EID) software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Infrared spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu IRAffinity-1S FTIR spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Italia S.r.l., Milan, Italy) equipped with a sealed, desiccated interferometer, a DLATGS detector, and a single-reflection diamond ATR crystal (QATR-10, Shimadzu Italia S.r.l., Milan, Italy). Measurements were performed in the 4000–400 cm−1 spectral range by averaging 45 interferograms at a resolution of 4 cm−1, with Happ–Genzel apodization. The ATR crystal was carefully cleaned before each acquisition, and a new background spectrum was collected for every sample. All measurements were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Spectral acquisition and data processing were carried out using LabSolution IR software (version 2.27, Shimadzu Italia S.r.l., Milan, Italy). Origin 2024 was used for the visualization.

Contents of aqueous Zn and Cu ions were determined on filtered samples, acidified with ultrapure concentrated HNO3, by the ICP-MS technique using an iCAP-TQe (Thermo Fisher Scientific) instrument equipped with iSC-65 Autosampler. Trace elements were quantified using QTegra software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and applying an external calibration approach, employing TraceCERT reference material (Periodic Table mix 1 for ICP, Sigma-Aldrich Production GmbH, Buchs, Switzerland) prepared and certified in compliance with ISO/IEC 17025 [46] and ISO 17034 [47]. In addition, a note quantity of Rh 2% HNO3 solution was added to each sample to control possible drifts resulting from the solution matrix effect.

Analytical precision was assessed by performing triplicate measurements. The measurement uncertainty for all trace species remained within 10%. As part of the quality assurance and quality control protocol, procedural blanks and control samples were processed alongside the samples, one blank and control sample for every four samples of the same category, and analyzed under identical conditions. All blank values were below the instrumental detection limits and the values of control samples were coherent with the certificated ones.

3. Results and Discussion

Foamed PS accounts for, at least, 23% of global litter in aquatic environments and, in Italy, even 50% of the litter is foamed PS [48,49]. The dissolution behavior of ZnO and Cu2O in distilled water under UV (λ = 254 nm) irradiation was evaluated in the presence and in the absence of PS fragments, obtained from post-use foamed PS, grinded in a mortar. The tests were performed in distilled water to minimize the impact and the interaction of real and complete marine water on the oxides’ behavior. So, we studied their activities only related to PS.

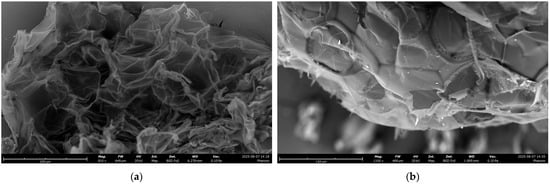

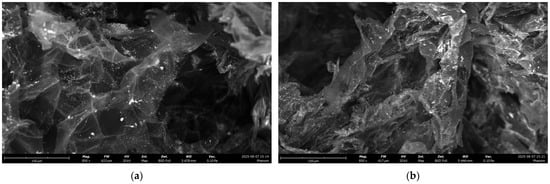

SEM images of PS fragments, before and after 24 h of UV light irradiation, showed only very low morphological degradation and no severe surface changes (Figure 1). The fragments were mainly >200 μm in size and had lateral dimensions that varied from tens to hundreds of micrometers, rather than discrete spherical or regular particles. In terms of morphology, pristine PS fragments (Figure 1a) showed a sheet-like, lamellar structure characterized by extensive wrinkling, folding, and crumpling. The sheets were not flat but densely bunched, forming a complex three-dimensional topography with pronounced ridges, folds, and crevices. Bright or semi-transparent edges indicated regions where the polymer thickness was extremely low, consistent with foamed PS. After UV irradiation (Figure 1b), no significant fragmentation or erosion was observed; the PS sheets appeared more compact with some small flakes and less translucent, suggesting a partial compression and densification of the lamellar structure. EDX analysis of PS fragments exhibited the presence of only C and O elements (Figures S1 and S2) from the PS polymer structure.

Figure 1.

SEM images of PS: (a) before the irradiation; (b) after UV irradiation (24 h).

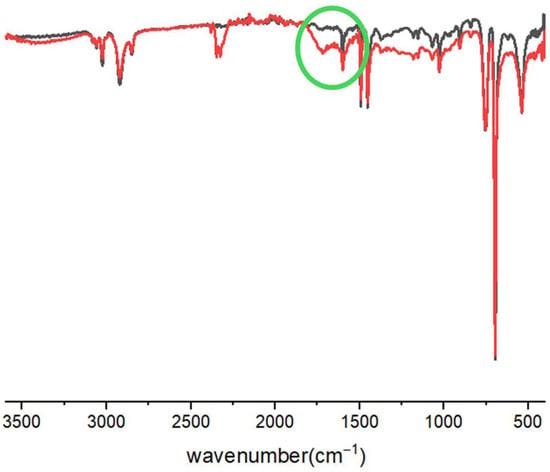

In the IR spectra of PS, a signal around 1700 cm−1 appeared after irradiation, due to the presence of carbonyl groups, produced by the photooxidation process (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

IR spectra of PS: (black) before the irradiation; (red) after UV irradiation (24 h).

This result indicates that UV light irradiation (Figure S3) promotes the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups on the PS surface, in line with the reported mechanisms involving photooxidation. In literature, the formation of carbonyl chain ends of PS under outdoor conditions is well-known [37]. In fact, the PS photooxidation involves a free radical mechanism with steps of initiation from organic radicals and/or oxygenated species (e.g., ROOH or OH), followed by the formation of ketone groups and then by the polymer chain breaking [50]. The enhanced surface oxidation may create additional active sites or species (e.g., radicals or protons) capable of interacting with metal oxides, thereby facilitating ion release [51].

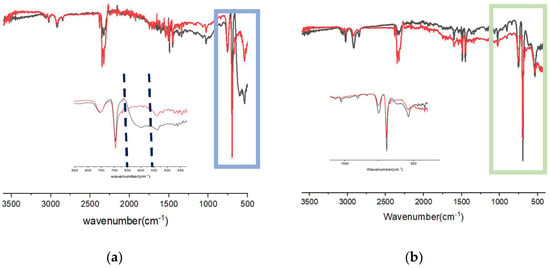

The signal around 1700 cm−1 was observed even when the PS was irradiated in the presence of the metal oxides, more evident with ZnO (Figure 3). The observed mitigation of a low-wavenumber band after UV irradiation (Figure 3, in the range 500–600 cm−1) points to a modification and/or a reduction of the Cu2O and ZnO species [52,53]. No significant –OH stretching was observed in all samples above 3000 cm−1, indicating that, in our conditions, the photooxidation mainly led to carbonyl functionalities rather than to a large accumulation of hydroxyl groups.

Figure 3.

IR spectra of PS stirred in water with Cu2O (a) or ZnO (b): (black) before the irradiation; (red) after UV irradiation (24 h).

Raman spectra did not show remarkable differences among the samples (Figure S4). The absence of new bands suggests that the main polymer backbone was structurally preserved, while the chemical modifications, detected by IR, occurred mostly at the surface or interfacial regions.

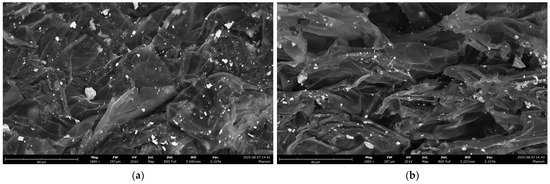

The overall macroscopic morphology of PS in the presence of ZnO and Cu2O remained essentially unchanged (Figure 4 and Figures S5–S8). In all cases, the PS matrix retained its wrinkled and folded sheet-like structure. Metal-containing domains were visible in SEM images due to contrast differences, but they did not correspond to significant changes in the underlying PS morphology. Overall, no major morphological differences were observed, either before or after UV treatment, with the exception of a slight compaction of PS after irradiation.

Figure 4.

SEM images of PS in the presence of Cu2O (a) under dark conditions; (b) after UV irradiation (24 h).

The SEM/EDX analysis of filtrated and washed PS, irradiated or not, in the presence of Cu2O displayed the presence of copper (Figure 4 and Figures S5 and S6): the metal clusters were similar in size, appearance, and aggregation state.

The EDX of PS stirred with ZnO, under dark conditions and after irradiation, showed the presence of zinc species and, in the SEM images, the clusters of metals were well dispersed and less aggregated than copper ones (Figure 5 and Figures S7 and S8).

Figure 5.

SEM images of PS in the presence of ZnO (a) under dark conditions; (b) after UV irradiation (24 h).

Results of metal ions concentrations are listed in Table 1. ICP-MS data show that UV irradiation in aqueous suspension of ZnO alone resulted in a Zn2+ release of 40.2 ppm. When PS was added under identical conditions, the concentration increased to 50.6 ppm, indicating a moderate but measurable enhancement of the dissolution process. In the dark and with PS, Zn2+ release decreased to 29.9 ppm, confirming that light exposure is a key requirement for activating this mechanism. For Cu2O, the effect was more pronounced. UV exposure alone produced only 5.0 ppm of Cu2+, whereas the addition of PS under UV light dramatically increased the concentration to 26.5 ppm. In contrast, under dark conditions, the release was minimal (1.1 ppm), further supporting the role of UV irradiation in driving the dissolution of copper oxide. To assess the statistical robustness of these differences, an unpaired two-sample t-test was performed between the UV-only and UV + PS conditions for both oxides. For ZnO, the increase from 40.2 to 50.6 ppm was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating that the presence of PS modestly enhances Zn2+ release under UV irradiation. For Cu2O, the difference was much more striking, with concentrations rising from 5.0 to 26.5 ppm, a result supported by a highly significant p-value (p ≪ 0.0001).

Table 1.

Ion concentration (as Zn2+ or Cu2+) in ppm (mean and standard deviation, SD) measured by ICP-OES in water solution in the dark or after 24 h of irradiation at λ = 254 nm in the presence or in the absence of PS.

These findings demonstrate that the presence of PS under UV irradiation promotes the dissolution of otherwise poorly soluble metal oxides into their ionic forms. While the effect is moderate for ZnO, it is dramatic for Cu2O, highlighting the strong catalytic-like role that PS can play in facilitating the metal-ion-mobilization under environmentally relevant conditions.

It is known that, under sunlight irradiation, the release of Zn2+ from ZnO is promoted by photoinduced charge carriers. In particular, the generation of electron–hole pairs upon light absorption leads to surface oxidation processes mediated by photogenerated holes (h+), which can attack the ZnO lattice and facilitate Zn2+ dissolution. This mechanism is consistent with literature reports indicating that, while Zn2+ release in the dark can be a proton-dependent process, under irradiation the role of h+ is predominant and the photogenerated holes enhance the oxidative dissolution of ZnO [51]. The same mechanism could be involved in the copper ions release through eventual oxidation steps of Cu(I) to Cu(II).

DSC provided additional insight into the structural changes induced by UV irradiation in the samples. The thermograms (Figure S9) display endothermic transitions between 100 °C and 115 °C, corresponding to the softening region of PS. Neat PS exhibited a peak at 110 °C with an enthalpy of 0.71 Jg−1, while UV irradiation increased the transition enthalpy to 1.42 Jg−1, suggesting enhanced molecular rearrangements due to photoinduced chain scission followed by limited cross-linking.

For ZnO, the non-irradiated sample showed an enthalpy of 1.03 Jg−1, which indicates a certain degree of chain ordering around the oxide filler. After irradiation, however, the enthalpy dropped sharply to 0.43 Jg−1, pointing to a pronounced loss of structural coherence in the polymer matrix. This behavior supports the hypothesis that photogenerated h+ and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) produced by ZnO accelerated oxidative degradation of the PS, in agreement with the spectroscopic evidence of carbonyl formation.

The sample with Cu2O exhibited a more moderate response: the enthalpy remained nearly unchanged upon irradiation (from 0.45 to 0.47 Jg−1), suggesting that the two opposite processes, akin photooxidation and cross-linking, may balance each other. The smaller band gap and distinct charge-carrier dynamics of Cu2O, compared to ZnO, likely limited the extent of photoinduced oxidative damage.

Overall, the calorimetric results confirm that UV irradiation altered the polymer chain mobility and thermal transitions, with ZnO promoting a slight degradation of the PS matrix, while Cu2O exerted a milder, self-limiting effect.

The observed photooxidation is therefore attributed to superficial effects rather than polymer degradation [54]. Data suggest that ZnO acts predominantly by facilitating UV-driven degradation (lowering Tg, increasing relaxation enthalpy), which may enhance the release of metal ions under UV, whereas Cu2O introduces more complex chemical interactions that modify the PS matrix more deeply, potentially curbing or altering ions release kinetics due to restricted mobility in the polymer backbone.

These findings align with recent studies indicating that microplastics can act as interfacial catalysts that promote the metal oxide dissolution under irradiation [55,56,57,58,59]. In particular, Tong et al. [51] demonstrated that PS enhances the sunlight-induced dissolution of ZnO via modifications from polymer photooxidation products and the formation of ROS. Under UV light, PS can therefore contribute both as a ROS-generating surface and as an electron shuttle, consistent with the indirect photocatalysis behavior reported for microplastics [51].

These results confirm that plastics are not passive sorbents but active chemical interfaces that modulate the fate of inorganic particles under irradiation. Notably, prior work showed that PS microplastics accelerate the oxidative dissolution of Ag nanoparticles under sunlight, increasing Ag+ release and toxicity in aquatic organisms [57]. In addition to ROS-driven pathways, proton-assisted mechanisms may further enhance dissolution. This dual pathway, oxidative and proton-driven dissolution, has been previously proposed in microplastic–metal systems [51].

4. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that post-consumer PS can significantly enhance the UV-induced dissolution of ZnO and Cu2O, increasing the release of zinc and copper ions despite showing no hard structural or chemical degradation.

Microplastics, such as PS, may thus act as catalytic-like interfaces that promote the transformation of otherwise stable compounds into bioavailable and potentially toxic metal ions. This poses new ecotoxicological risks not only due to physical ingestion of microplastics, but also via their chemical interactions in sunlight-exposed surface waters. This finding reveals a previously under-recognized pathway through which microplastics may influence the biogeochemical cycling and bioavailability of metal-based contaminants.

This synergistic plastic–light effect warrants further investigation, given the co-presence of plastics, sunlight, oxygen, and metal-based pigments and antifouling materials in coastal waters.

From an applied perspective, these insights are intended to draw attention to the long-term behavior and environmental fate of metal-oxide-based coatings and formulations, which may undergo accelerated transformation in the presence of plastics. Further studies should clarify the molecular mechanisms governing these interfacial processes and assess their generality across different plastic types, metal oxides, irradiation conditions, and real seawater matrices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemengineering10010008/s1. Figure S1. (a) SEM image of PS before the irradiation and its EDX spectrum (b); Figure S2. (a) SEM image of PS after the UV irradiation and its EDX spectrum (b); Figure S3. Images of the UV irradiation set-up of our systems; Figure S4. Raman spectra: (black) before the irradiation; (red) after UV irradiation of: PS (a), PS stirred in water with Cu2O (b) PS stirred in water with ZnO (c); Figure S5. (a) SEM image of PS after stirring with Cu2O in water under the dark; its EDX spectrum (b); Figure S6. (a) SEM image of PS after stirring with Cu2O in water under UV irradiation (24 h); its EDX spectrum (b); Figure S7. (a) SEM image of PS after stirring with ZnO in water under the dark; its EDX spectrum (b); Figure S8. (a) SEM image of PS after stirring with ZnO in water under UV irradiation (24 h); its EDX spectrum (b); Figure S9. (a) DSC analysis of PS (blue), irradiated PS (green), irradiated PS in the presence of Cu2O (red), PS in the presence of Cu2O at the dark (brown); (b) DSC analysis of PS (blue), irradiated PS (green), irradiated PS in the presence of ZnO (red), PS in the presence of ZnO at the dark (brown).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C., M.C. and L.T.; methodology, F.C., R.S. and A.F.; investigation, F.C. and A.M.; data curation, F.C., S.D.G., R.S. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T., F.C. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, N.d., M.C., R.S. and L.T.; supervision, N.d. and L.T.; funding acquisition, N.d. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially funded by PRIN 2022 project code 2022R5E2P5 (Master CUP B53C24006210006, Research Unit CUP D53C24003280006).

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request due to restrictions. The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

N.d., L.T., F.C. and A.M. express their gratitude to the CAST—Center for Advanced Studies and Technology of University “G. d’Annunzio” for supplying the cryogenic gases. The authors wish to thank V. Summa and P.P. Ragone (CNR-IMAA, Italy) for the ICP-MS facilities included in the STAC-UP project. S.D.G. was attending the PhD programme in “Biomolecular and Pharmaceutical Sciences” at the University of Chieti-Pescara, Cycle XXXVIII with the support of a scholarship co-financed by the Ministerial Decree no. 352 of 9 April 2022, based on the NRRP - funded by the European Union–NextGenerationEU-Mission 4 “Education and Research”, Component 2 “From Research to Business”, Investment 3.3, and by the company Carbotech S.r.l., Via dell’industria, Martinsicuro (TE, Italy).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PS | Polystyrene |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| Tg | Glass transition temperature |

| ICP | Inductively Coupled Plasma |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared |

References

- Thushari, G.G.N.; Senevirathna, J.D.M. Plastic Pollution in the Marine Environment. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tsui, M.T.-K.; Kwong, R.W.M.; Pan, K. Editorial: Metal Contamination, Bioaccumulation, and Toxicity in Coastal Environments under Increasing Anthropogenic Impacts. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 10, 1349435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Heavy Metals, Metalloids and Other Hazardous Elements in Marine Plastic Litter. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 111, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont, N.J.; Aanesen, M.; Austen, M.C.; Börger, T.; Clark, J.R.; Cole, M.; Hooper, T.; Lindeque, P.K.; Pascoe, C.; Wyles, K.J. Global Ecological, Social and Economic Impacts of Marine Plastic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 142, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A. Foamed Polystyrene in the Marine Environment: Sources, Additives, Transport, Behavior, and Impacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 10411–10420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esterhuizen, M.; Lee, S.-A.; Kim, Y.; Järvinen, R.; Kim, Y.J. Ecotoxicological Consequences of Polystyrene Naturally Leached in Pure, Fresh, and Saltwater: Lethal and Nonlethal Toxicological Responses in Daphnia Magna and Artemia Salina. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1338872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, B.G.; Koizumi, K.; Chung, S.-Y.; Kodera, Y.; Kim, J.-O.; Saido, K. Global Styrene Oligomers Monitoring as New Chemical Contamination from Polystyrene Plastic Marine Pollution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 300, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolaosho, T.L.; Rasaq, M.F.; Omotoye, E.V.; Araomo, O.V.; Adekoya, O.S.; Abolaji, O.Y.; Hungbo, J.J. Microplastics in Freshwater and Marine Ecosystems: Occurrence, Characterization, Sources, Distribution Dynamics, Fate, Transport Processes, Potential Mitigation Strategies, and Policy Interventions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoca, M.S.; McInturf, A.G.; Hazen, E.L. Plastic Ingestion by Marine Fish Is Widespread and Increasing. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2188–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, N.; Calarco, A.; Curcuruto, G.; Di Natale, M.; Augello, G.; Carroccio, S.C.; Cerruti, P.; Cervello, M.; Cuttitta, A.; Colombo, P.; et al. Photoaging of Polystyrene-Based Microplastics Amplifies Inflammatory Response in Macrophages. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143131–143139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Council. Directive (Eu) 2019/904 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on the Reduction of the Impact of Certain Plastic Products on the Environment. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, 62, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sharkawy, M.; Alotaibi, M.O.; Li, J.; Du, D.; Mahmoud, E. Heavy Metal Pollution in Coastal Environments: Ecological Implications and Management Strategies: A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Trung, T.; Ba Ngoc, N.; Dinh Tuan, T.; Ngoc Phuoc, H.; Duc Thanh, N.; Van Quyen, T.; Thanh Viet, L.; Manh Hao, N. Preparation of Antifouling Composite Coating for Rubber. Part 1: Manufacturing and Laboratory Testing. Malays. J. Compos. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 16, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniagor, C.O.; Igwegbe, C.A.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Iwuchukwu, F.U.; Eshiemogie, S.; Menkiti, M.C.; Ighalo, J.O. CuO Nanoparticles as Modifiers for Membranes: A Review of Performance for Water Treatment. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-B.; Kim, Y.W.; Lim, S.K.; Roh, T.H.; Bang, D.Y.; Choi, S.M.; Lim, D.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Baek, S.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; et al. Risk Assessment of Zinc Oxide, a Cosmetic Ingredient Used as a UV Filter of Sunscreens. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2017, 20, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yebra, D.M.; Kiil, S.; Weinell, C.E.; Dam-Johansen, K. Dissolution Rate Measurements of Sea Water Soluble Pigments for Antifouling Paints: ZnO. Prog. Org. Coat. 2006, 56, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaie, A.; Afshaar, A.; Mousavi, S.B.; Heidari, M. Investigation of the Release Rate of Biocide and Corrosion Resistance of Vinyl-, Acrylic-, and Epoxy-Based Antifouling Paints on Steel in Marine Infrastructures. Polymers 2023, 15, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénézeth, P.; Palmer, D.A.; Wesolowski, D.J.; Xiao, C. New Measurements of the Solubility of Zinc Oxide from 150 to 350 °C. J. Solut. Chem. 2002, 31, 947–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, J.; Sedmidubský, D.; Jankovský, O. Size and Shape-Dependent Solubility of CuO Nanostructures. Materials 2019, 12, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Qu, R.; Wen, Q.; Liu, N.; Ge, F. Effects of Photoaged Polystyrene Microplastics and Nanoplastics on the Extracellular Aggregation and Intracellular Accumulation of ZnO Nanoparticles to Algae. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.W.Y.; Zhou, G.-J.; Leung, P.T.Y.; Han, J.; Lee, J.-S.; Kwok, K.W.H.; Leung, K.M.Y. Sunscreens Containing Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Can Trigger Oxidative Stress and Toxicity to the Marine Copepod Tigriopus Japonicus. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 154, 111078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JunFeng, L.; Wei, W.; Saisai, Z.; Hua, W.; Huan, X.; Shuangye, S.; Xuying, H.; Bing, W. Effects of Chronic Exposure to Cu2+ and Zn2+ on Growth and Survival of Juvenile Apostichopus Japonicus. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 2014, 26, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglikowska, A.; Szwarc, A.; Bartosik, K.; Gruba, D.; Michalak, A.; Namiotko, L.; Pouch, A.; Zaborska, A.; Namiotko, T. Environmental Concentrations of Metals (Cu and Zn) Differently Affect the Life History Traits of a Model Freshwater Ostracod. Eur. Zool. J. 2024, 91, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Copper Uptake and Subcellular Distribution in Five Marine Phytoplankton Species. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1084266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falfushynska, H.; Lewicka, K.; Rychter, P. Unveiling the Hydrochemical and Ecotoxicological Insights of Copper and Zinc: Impacts, Mechanisms, and Effective Remediation Approaches. Limnol. Rev. 2024, 24, 406–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.; Moore, L.R.; Tetu, S.G. Investigating Zinc Toxicity Responses in Marine Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Microbiology 2021, 167, 001064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamers, A.; Blust, R.; De Coen, W.; Griffin, J.L.; Jones, O.A.H. Copper Toxicity in the Microalga Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii: An Integrated Approach. BioMetals 2013, 26, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ytreberg, E.; Hansson, K.; Hermansson, A.L.; Parsmo, R.; Lagerström, M.; Jalkanen, J.-P.; Hassellöv, I.-M. Metal and PAH Loads from Ships and Boats, Relative Other Sources, in the Baltic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 182, 113904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, S.K.; Darko, G.; Akaranta, O. Chemistry and Application of Emerging Ecofriendly Antifouling Paints: A Review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2020, 17, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerström, M.; Ytreberg, E.; Wiklund, A.-K.E.; Granhag, L. Antifouling Paints Leach Copper in Excess—Study of Metal Release Rates and Efficacy along a Salinity Gradient. Water Res. 2020, 186, 116383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagerström, M.; Ytreberg, E. Quantification of Cu and Zn in Antifouling Paint Films by XRF. Talanta 2021, 223, 121820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA-HQ-OPP-2010-0212 Copper Compounds Interim Registration Review Decision; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, Regulation (EU) No 524/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council. In Fundamental Texts on European Private Law; Hart Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2016; pp. 189–207.

- Rodrigues, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Santos-Echeandía, J. Interaction of Microplastics with Metal(Oid)s in Aquatic Environments: What Is Done so Far? J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 6, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumwesigye, E.; Nnadozie, C.F.; Akamagwuna, F.C.; Noundou, X.S.; Nyakairu, G.W.; Odume, O.N. Microplastics as Vectors of Chemical Contaminants and Biological Agents in Freshwater Ecosystems: Current Knowledge Status and Future Perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 330, 121829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Shi, L.; Yi, K.; Yu, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Li, J. Microplastics as a Vehicle of Heavy Metals in Aquatic Environments: A Review of Adsorption Factors, Mechanisms, and Biological Effects. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 113995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biber, N.F.A.; Foggo, A.; Thompson, R.C. Characterising the Deterioration of Different Plastics in Air and Seawater. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonucci, L.; Mascitti, A.; Ferretti, A.M.; Coccia, F.; D’Alessandro, N. The Role of Nanoparticle Catalysis in the Nylon Production. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surricchio, G.; Pompilio, L.; Arizzi Novelli, A.; Scamosci, E.; Marinangeli, L.; Tonucci, L.; D’Alessandro, N.; Tangari, A.C. Evaluation of Heavy Metals Background in the Adriatic Sea Sediments of Abruzzo Region, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 684, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Alessandro, N.; Coccia, F.; Vitali, L.A.; Rastelli, G.; Cinosi, A.; Mascitti, A.; Tonucci, L. Cu-ZnO Embedded in a Polydopamine Shell for the Generation of Antibacterial Surgical Face Masks. Molecules 2024, 29, 4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, F.; Mascitti, A.; Rastelli, G.; D’Alessandro, N.; Tonucci, L. Sustainable Photocatalytic Reduction of Maleic Acid: Enhancing CuxO/ZnO Stability with Polydopamine. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, F.; Mascitti, A.; Caporali, S.; Polito, L.; Porcheddu, A.; Di Nicola, C.; Tonucci, L.; d’Alessandro, N. Wool-Supported Pd and Rh Nanoparticles for Selective Hydrogenation of Maleic Acid to Succinic Acid in Batch and Flow Systems. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 36760–36768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, F.; d’Alessandro, N.; Mascitti, A.; Colacino, E.; Tonucci, L. Transition Metal Catalysts for the Glycerol Reduction: Recent Advances. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202301672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, F.; Tonucci, L.; Del Boccio, P.; Caporali, S.; Hollmann, F.; D’Alessandro, N. Stereoselective Double Reduction of 3-Methyl-2-Cyclohexenone by Use of Palladium and Platinum Nanoparticles in Tandem with Alcohol Dehydrogenase. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.S.; Gopinath, S.; Razdan, P.; Delattre, C.; Nirmala, G.S.; Natarajan, R. Thermal Decomposition of Expanded Polystyrene in a Pebble Bed Reactor to Get Higher Liquid Fraction Yield at Low Temperatures. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2140–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 17034:2016; General Requirements for the Competence of Reference Material Producers. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Chan, H.H.S.; Not, C. Variations in the Spatial Distribution of Expanded Polystyrene Marine Debris: Are Asian’s Coastlines More Affected? Environ. Adv. 2023, 11, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piehl, S.; Mitterwallner, V.; Atwood, E.C.; Bochow, M.; Laforsch, C. Abundance and Distribution of Large Microplastics (1–5 Mm) within Beach Sediments at the Po River Delta, Northeast Italy. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, E.; Haddad, R. Photodegradation and Photostabilization of Polymers, Especially Polystyrene: Review. Springerplus 2013, 2, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Song, K.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Ji, J.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Dissolution and Toxicity Enhancement by Polystyrene Microplastics under Sunlight Irradiation. Chemosphere 2022, 299, 134421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepa, R.; Muthuraj, D.; Kumar, E.; Veeraputhiran, V. Microwave Assisted Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Its Antimicrobial Efficiency. J. Nanosci. Technol. 2019, 5, 640–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauldurai, J.; Perumal, A.M.; Jeyaraja, D.; Amal, P.V.R. Facile Synthesis of Spherical Flake-Shaped CuO Nanostructure and Its Characterization towards Solar Cell Application. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, M.D.; Garcia-Sanoguera, D.; Parres, F.; López, J. Recycling of Expanded Polystyrene from Packaging. Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycl. Technol. 2010, 26, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, D. Bottles, Bags, Ropes and Toothbrushes: The Struggle to Track Ocean Plastics. Nature 2016, 536, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Duan, P.; Min, W.; Zhang, W. Polystyrene Microplastics Enhance Oxidative Dissolution but Suppress the Aquatic Acute Toxicity of a Commercial Cadmium Yellow Pigment under Simulated Irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Duan, P.; Tian, X.; Huang, J.; Ji, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, W. Polystyrene Microplastics Sunlight-Induce Oxidative Dissolution, Chemical Transformation and Toxicity Enhancement of Silver Nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 827, 154180–154188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errázuriz León, R.; Araya Salcedo, V.A.; Novoa San Miguel, F.J.; Llanquinao Tardio, C.R.A.; Tobar Briceño, A.A.; Cherubini Fouilloux, S.F.; de Matos Barbosa, M.; Saldías Barros, C.A.; Waldman, W.R.; Espinosa-Bustos, C.; et al. Photoaged Polystyrene Nanoplastics Exposure Results in Reproductive Toxicity Due to Oxidative Damage in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 348, 123816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Li, G.; Ding, S.; Song, W.; Zhang, M.; Jia, R.; Chu, W. Effects of UV-Based Oxidation Processes on the Degradation of Microplastic: Fragmentation, Organic Matter Release, Toxicity and Disinfection Byproduct Formation. Water Res. 2023, 237, 119983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.