Abstract

Recently, the environmental impact of halocarbons has become increasingly concerning, particularly due to the growing influence of non-regulated halocarbons on stratospheric ozone depletion and their adverse health effects in the troposphere. Previous model studies have highlighted the importance of halocarbon emissions from the YRD. However, only several reports have discussed the long-term pollution characteristics and health risks of halocarbons in the YRD based on observational data. The continuous observation of halocarbons was conducted in the central part of the YRD (Shanxi site) from 2018 to 2023. The result showed that rise in halocarbon levels was primarily driven by alkyl halides, including dichloromethane (1.194 ppb to 1.831 ppb), chloromethane (0.205 ppb to 1.121 ppb), 1,2-dichloroethane (0.399 ppb to 0.772 ppb), and chloroform (0.082 ppb to 0.300 ppb). The PMF and CBPF analysis revealed that pharmaceutical manufacturing (37.0% to 60.2%), chemical raw material manufacturing (8.0% to 19.9%), solvent use in machinery manufacturing (12.4% to 24.7%), solvent use in electronic industry, and background sources were the main sources of halocarbons at the Shanxi site. Among them, the contributions of chemical raw material manufacturing, as well as of solvent use in machinery manufacturing and electronic industry, are increasing. These aspects are all dominated by local emissions. Furthermore, the carcinogenic risks of chloroform and 1,2-dichloroethane, which rank first in this regard, are increasing. Also, attention should be paid to solvent use in the electronic industry and the background. The probabilities of these activities coming with health risks that exceed the acceptable levels are 94.8% and 94.9%. This study enriches the regional observation data in the YRD region, offering valuable insights into halocarbon pollution control measures for policy development.

1. Introduction

Halocarbons are important components of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). They are widely used in industrial manufacturing as blowing agents, refrigerants, solvents, and fire suppressants. However, due to their ozone-depleting potential in the stratosphere and contribution to the greenhouse effect, they are regulated under the Montreal Protocol and its amendments [1]. As of 2022, some regulated halocarbons (i.e., CFC-11 [2], carbon tetrachloride [3] and Halon-1211 [4] and others) have shown a declining trend.

In contrast, the global emissions of some non-regulated halocarbons, such as dichloromethane and chloroform, are increasing. Studies suggest that global emissions of dichloromethane rose from 637 Gg/year in 2006 to 1171 Gg/year in 2017 [5], with reported emissions reaching 1038 Gg/year in 2019 [6]. The emission of chloroform increased steadily until 2017 (2017: 345 Gg/year) and remained stable (2019: 339 Gg/year) [3]. Although these are historically considered to have a minor impact on stratospheric ozone due to their relatively short atmospheric lifetimes (<6 months), recent aircraft observations over tropical regions have revealed significantly elevated concentrations of non-regulated halocarbons in the tropopause [7] and the lower stratosphere [8]. Moreover, modeling studies indicated the presence of stratospheric chlorine [9] and bromine [10]. These findings highlight the growing contribution of non-regulated halocarbons to stratospheric chlorine loading, which adds further uncertainty in predicting the recovery timing of the ozone layer. In addition, non-regulated halocarbons are regarded as hazardous air pollutants that exert significant adverse health effects [11,12,13] and are prohibited or restricted in accordance with relevant regulations [14,15].

Emissions of non-regulated halocarbons from Asia, particularly eastern China, have been the primary drivers of global emission trends [6,16,17,18,19]. Claxton et al. [19] reported that Asia’s share of global dichloromethane emissions increased from 68% to 89% between 2006 and 2017, while An et al. [6] identified the North China Plain and the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) as the main contributors. Fang et al. [16] focused on chloroform emissions from eastern China between 2007 and 2015, and An et al. [17] used domestic observational data to estimate nationwide chloroform emissions from 2010 to 2020. Both studies found that the trends and magnitudes of China’s emissions during their respective study periods closely matched global changes.

However, observations in eastern China have primarily been concentrated in the North China Plain region [18,20,21,22] and the Pearl River Delta [23,24,25]. In contrast, research on near-surface halocarbon concentrations in the YRD remains limited. Previous studies in the YRD region have mostly focused on regulated substances [26,27] and the short-term variation [28,29,30]. Jiang et al. [31] previously investigated temporal trends in halocarbon concentrations in the region, identifying a continuing increase. However, these studies have not addressed the long-term source evolution patterns of halocarbon emissions. Moreover, most health risk assessments are deterministic [32,33,34], in which each exposure parameter input into the model is represented by a single value. This approach may either overestimate or underestimate the actual risk [35].

In this study, halocarbons in the central YRD region (Shanxi site) were investigated using an online VOC monitoring system. Continuous observations were conducted from 2018 to 2023 to characterize the pollution features of halocarbons. Based on these data, major anthropogenic sources were identified using the positive matrix factorization (PMF) model, and their potential emission regions were further determined through the conditional bivariate probability function (CBPF) method. Following the exposure assessment and uncertainty analysis recommended by the U.S. EPA, the health risks associated with halocarbon species and their sources in this region were evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Monitoring Methods

As shown in Figure 1, the monitoring site selected for this study (30°49′29″ N, 120°52′6″ E) was the Shanxi site (No. 330400102), which is part of the Zhejiang Atmospheric Composite Pollution Auto-Monitoring Net. The Shanxi site is surrounded by major industrial urban clusters of the YRD, such as Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Suzhou. Within a 3 km radius of the monitoring site, the area to the east consists of a mixed zone of industrial parks and residential areas, where the industrial parks mainly focus on traditional machinery manufacturing, electronic information products, chemical raw materials, and medical products. Extensive farmland and woodland are scattered to the north and south of the site, while approximately 5 km to the northwest lies another industrial park encompassing electronic manufacturing, machinery manufacturing, and plastic production.

Figure 1.

Location of Shanxi site (a). Photo of sampling site (b). Specific industries surrounding the monitoring site (c).

An online monitoring instrument (TH-PKU 300B GC-MS/FID (Wuhan Tianhong Environmental Protection Industry Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) [36]) with a time resolution of 1 h was employed in this study to observe the concentration of halocarbon. This equipment measures ambient halocarbons through four main stages: preparation, sampling and pre-concentration, GC analysis, and system heating back-flush. Ambient air samples first pass through a cold trap that removes impurities such as O3, H2O, and CO2. Subsequently, the sample is introduced into a low-temperature (−150 °C) enrichment trap. After pre-concentration, halocarbons are heated to the gaseous phase and analyzed by a chromatographic column coupled with a mass spectrometer. More details of this equipment can be found in Wang et al. [37]. The method detection limits (MDLs) for halocarbons were calculated following the EPA TO-15 guideline [38] and are summarized in Table S1. This continuous observation was conducted between 1 January 2018, and 31 December 2023. During the study period, the numbers of data points we obtained from each year were 6863, 7618, 7268, 7625, 7091, and 7168, respectively, with an overall data validity rate of 86.5%. Furthermore, we utilized the Lufft WS500-UMB [39] (Hach Water Quality Analytical Instrument (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) intelligent meteorological sensor to monitor various meteorological parameters. The meteorological parameters are presented in Table S2.

2.2. Positive Matrix Factorization Model

The PMF 5.0 model [40] was used to analyze the major sources and relative contributions at the Shanxi site. For a detailed description of the model, please refer to previous studies [41]. A brief introduction to the fundamental principle of the PMF model is provided below:

In Equation (1), xij represents the concentration of the jth VOC species measured in the ith sample; gik denotes the contribution of the kth factor to the ith sample; fkj is the abundance of the jth species in the kth factor; eij represents the residual for the jth species in the ith sample; and p is the number of sources. To reduce the rotational ambiguity of factors, the PMF model applies non-negativity constraints to parameters, minimizing the objective function Q, as shown in Equation (2):

where uth is the uncertainty of the jth halocarbon species in the ith sample. The uncertainties were calculated with Equation (3):

EF stands for error factor, which depends on the precision of the monitoring instruments. Based on the species selection criteria reported in previous studies [13], 20 halocarbon species were input into the model. Additionally, acetone and 1,3-butadiene were introduced as typical tracers. Acetone is a representative compound in industrial production [42] and 1,3-butadiene is commonly used as an indicator of synthetic manufacturing sectors such as rubber and plastics [43].

2.3. Conditional Bivariate Probability Function

By using a conditional bivariate polar plot model, the spatial distribution of pollutants can be visualized. Previous studies [44,45] have combined PMF source apportionment results with this approach to illustrate the location information of different emission sources. It can be defined as follows:

In Equation (4), represents the number of samples within the wind direction sector at a given wind speed that exceed a certain threshold , while denotes the total number of samples within that wind speed and wind direction sector. In this study, the threshold is set at the 95th percentile of each source’s contribution, and the direction corresponding to the high-value points is used to determine the direction of each pollution source [46,47]. A detailed introduction to CBPF can be found in Carslaw et al. [48].

2.4. Health Risk Assessment

To assess the health risks posed by halocarbons in the atmospheric environment, this study first employed the point evaluation method recommended by the U.S. EPA [49]. The carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks resulting from inhalation exposure can be calculated using the following formulas:

Equations (5) and (6) are used to assess carcinogenic risk, where R represents the cancer risk, IUR is the inhalation unit risk (m3/μg), and EC is the exposure concentration (μg/m3). CA refers to the concentration of the pollutant in air (μg/m3), ET is the exposure time (hours/day), EF is the exposure frequency (days/year), ED is the exposure duration over a lifetime (years), and AT is the average time (hours). Equations (7) and (8) are employed to evaluate non-carcinogenic risk by calculating the dimensionless hazard quotient (HQ). RfC denotes the reference concentration (μg/m3), which represents the inhalation exposure level at or below which no appreciable health effects are expected to occur over a lifetime. The RfC values and the IUR values for each halocarbon are listed in Table S3.

This study also employed the Monte Carlo simulation method to quantify the probabilistic distribution of health risks associated with individual compounds and source categories [50]. The simulations were conducted using Crystal Ball 11.1 software, with the number of iterations set to 10,000. The probability distributions of parameters used in the model are presented in Tables S4 and S5, in which the exposure time, exposure duration, and average time refer to the standards outlined in the Chinese Exposure Factors Handbook [51].

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Halocarbon Concentrations

This study conducted continuous observations at the Shanxi site from 2018 to 2023, including 16 alkyl halides, 7 alkenyl halides, and 5 aryl halides. The 6-year surface observation campaign at the Shanxi site shows the distinctive yearly change, with a range from 3.013 ppb to 4.774 ppb (Figure S1). An overall increasing trend in concentrations was observed except for the period between 2020 and 2022. During this time, the outbreak of COVID-19 in China and the governmental control measures significantly impacted regional production activities, causing a sharp decline in emissions from some halocarbons sources [52]. Notably, the concentration of aryl halides increased from 0.223 ppb in 2019 to 0.240 ppb in 2020, with their percentage contribution rising by 1.8% (Figure S1). This indicates that certain sources of halocarbon emissions remained unaffected by restrictions.

To clarify the influence of human activities on halocarbon concentration, the monthly variation was analyzed. As shown in Figure S2, halocarbon concentrations generally decreased in February, which could be related to the official Chinese Spring Festival holiday period, during which surrounding industrial activities typically slow down. Between 2018 and 2022, the concentration dropped from January to February and ranged from 0.092 ppb to 1.889 ppb. This pattern was particularly pronounced in 2020, when the total concentration dropped to 0.583 ppb. This can be attributed to the policy of extending the Spring Festival holiday [53] and a tiered return-to-work policy implemented by local enterprises [54]. Concentrations of halocarbons began to rise from March to May. A subsequent decrease was observed during June, July, and August, with levels being affected by the enhancement of photochemical reactions and the increase in boundary layer heights during the summer. This seasonal pattern was evident from 2018 to 2021. However, the downward trend was less apparent in 2022 and 2023. According to reports from the National Climate Center, temperatures in parts of the YRD during June 2022 and 2023 were 2–4 °C higher than the historical average [55]. As the evaporation rates and emission strengths [56] of VOCs are temperature-dependent, it is speculated that the frequent extreme heat events in 2022 and 2023 contributed to the elevated concentrations during this period. Halocarbon concentrations began to rise again after September, reaching relatively high levels in December each year. From 2019 to 2023, December concentrations ranged from 2.959 ppb to 6.65 ppb. This was associated with suppressed boundary layer and poor dispersion conditions during the winter season. These results further support previous findings that VOC concentrations in the YRD tend to be higher in winter than that in summer [57,58].

The concentrations and average contributions of 28 halocarbons are displayed in Table S6. Given that some halocarbons present greater threats to public health than others, 13 priority halocarbons were selected based on the Urban Air Toxics List [15]. To emphasize the features of Shanxi site, comparative analysis was conducted with simultaneous observations from other YRD regions.

As shown in Table 1, dichloromethane and chloromethane were the most abundant halocarbons in the study area. Both exhibited an overall increasing trend, with a concentration decrease observed in 2020. Their concentration ranges were 1.194–1.831 ppb and 0.201–1.121 ppb, respectively. Dichloromethane is predominantly influenced by anthropogenic sources, including industrial solvent usage [29], foam manufacturing, and emissions from HFC production [6,7]. Although chloromethane is globally considered to originate primarily from natural sources [3] and is recognized as a tracer for biomass burning [59], studies have shown that the increasing trends in eastern China are strongly affected by anthropogenic activities [60]. These sources include the production of methyl chloride, solvent use in plastic and rubber industries, HCFC/HFC manufacturing, and coal combustion in industrial processes [61,62,63]. In this study, chloromethane levels were comparable to those observed at the Shangdianzi site (0.810 ppb) [22] and in the industrial area of Handan (1.290 ppb) [64], but significantly higher than those in the clean air mass at the Shangdianzi site (0.534 ppb) [22]. This suggests that the continued increase in chloromethane levels in this study may be led by intensified industrial usage. Additionally, dichloromethane and chloromethane concentrations at the two Zhejiang sites (Hangzhou and Shanxi) were higher than those in Nanjing, likely due to differences in dominant industrial sectors between two regions.

Table 1.

Comparison of halocarbons between Shanxi site and other studies in YRD region in 2018–2023 (Unit: ppb).

The concentration of 1,2-dichloroethane exhibited a fluctuating increase over the study period, rising from 0.632 ppb to 0.772 ppb, whereas 1,2-dichloropropane showed a declining trend, decreasing from 0.217 ppb to 0.121 ppb. Compared with Nanjing, concentrations of both compounds were relatively lower in the Zhejiang sites. These substances are commonly used as solvents in industrial processes such as machinery manufacturing [65,66]. The concentrations of tetrachloroethylene and vinyl chloride remained relatively stable, ranging from 0.037 to 0.041 ppb and 0.020 to 0.058 ppb, respectively, with no significant differences observed across the YRD region. Tetrachloroethylene and vinyl chloride are representative compounds used in the dry-cleaning industry [67] and plastic manufacturing sectors [68], respectively.

In contrast, the levels of chloroform, trichloroethylene, and 1,1-dichloroethane at the Shanxi site have shown continuous upward trends. The concentration ranges for chloroform and 1,1-dichloroethane were 0.082 ppb–0.300 ppb and 0.005 ppb–0.417 ppb, respectively, representing approximately 10-fold and 2-fold increases in 2020–2023 compared to 2018–2019. Similarly, the concentration of trichloroethylene increased from 0.032 ppb to 0.070 ppb. Trichloroethylene is commonly used as a cleaning agent in dry cleaning and electronics manufacturing [66,69,70,71], while 1,1-dichloroethane is a good solvent used as dry-cleaning agent for electronic components [72] and fabric manufacturing [73]. The increases in these substances are related to the electronic manufacturing nearby Shanxi site, which is a key emerging industry in Jiashan County [74].

Additionally, the presence of some substances is relatively low and virtually unchanged during the studying period, such as 1,2-dibromoethane, trans-1,3-dichloropropene, and cis-1,3-dichloropropene. Their concentrations in Nanjing are considerably higher than those at the Hangzhou and Shanxi sites in Zhejiang. The mixture of 1,3-dichloropropene is widely used in agriculture as a pre-plant–soil fumigant [75] and 1,2-dibromoethane was once used as a pesticide ingredient but has been banned under relevant Chinese regulations [76]. These substances can pose great health risk, emphasizing the importance of potential transport from other regions of the YRD region.

3.2. Emission Source Profiles and Potential Sources Regions of Halocarbons

3.2.1. Emission Source Profiles at Shanxi Site

The PMF model has identified the major emission sources of halocarbons at the Shanxi site from 2018 to 2023, including solvent use in machinery manufacturing, the manufacturing of chemical raw materials, pharmaceutical manufacturing, background, and solvent use in electronic industry. The identification process for each factor is descripted in Text S1 and the yearly source profiles are shown in Figure S3. The validation of 5-factor solutions can be found in Text S2, Text S3, Tables S7 and S8. Figure 2 presents the percentage contributions of the five source factors to halocarbon concentrations at the Shanxi site. Pharmaceutical manufacturing (37.0–60.2%) and the production of chemical raw materials (12.4–24.7%) were the dominant sources. Solvent use in the electronic industry and machinery manufacturing was the secondary contributor, with contributions ranging between 10.3 and 13.7% and between 8.0 and 19.9%, respectively.

Figure 2.

The concentrations (a) and contributions (b) of halocarbon sources derived from PMF during the period of 2018–2023.

From 2018 to 2023, the contribution of pharmaceutical manufacturing showed a continuous increase, with its contribution to ambient halocarbon levels reaching 60.2% in 2020. The significant rise in 2020 was largely driven by the policies adopted during COVID-19 pandemic, aiming to improve the local pharmaceutical industries [77]. Additionally, the large-scale use of disinfectants reported in China after the outbreak [78,79] may have contributed to increased levels of chlorinated disinfection by-products [80,81], ultimately leading to the rise in by-products observed in relation to the pharmaceutical manufacturing source.

The contributions of chemical raw material manufacturing and machinery manufacturing both increased, except for the year 2020. In 2020, they decreased by 4% and 5% compared to 2019; this was correlated with the decline in production [81]. In addition, some studies reported a decrease in VOC emissions from the automobile manufacturing and maintenance industry in China from 2019 to 2020 [82], which is generally consistent with the decline observed in this study.

From 2018 to 2023, the concentration of solvents used in the electronics industry increased from 0.67 ppb to 1.16 ppb, while its contribution rate remained approximately 14.0%. This rise is in agreement with the rapid growth of Zhejiang’s electronics information industry in 2020, driven by IC manufacturing in Shanxi county [83]. The value-added output of Zhejiang’s above-scale electronic information manufacturing industry increased by 16.8% that year [84].

The contribution of background sources fluctuated within the range of 6.8% to 9.0%. Although the levels of representative substances in background sources, such as CFC-11 and carbon tetrachloride, continuously declined, the contributions of dichloromethane and 1,2-dichloroethane in this source increased. This could be due to the enhanced fugitive emissions at the studying site [85] or the influence of halocarbon emission sources not considered in this study, such as coal combustion [64], biomass burning [29], or the steel manufacturing industry [86].

3.2.2. Potential Sources Regions of Halocarbons at Shanxi Site

The CBPF analysis shows that the emissions from solvent use in machinery manufacturing, chemical raw materials, and solvent use in the electronic industry are predominantly local (Figure 3). The pharmaceutical manufacturing source is mainly associated with local and southeastward emissions, corresponding to the potential geographic location of medical production enterprises which are depicted in Figure 1. Representative substances of the background source are regulated compounds, such as CFC-11, CFC-113, and carbon tetrachloride. High values are detected for this source in the east, with speeds exceeding 5 m/s. Jiaxing city is located on the border of Zhejiang province, adjacent to a metropolitan area with a developed industrial base. The transportation of regulated halocarbons from these areas causes the elevation of background concentrations at the Shanxi site. Solvent use in the electronic industry was observed in all directions throughout the study period, reflecting its importance as a key emerging industry in Shanxi County.

Figure 3.

CBPF for the sources of halocarbons at the Shanxi site during the period of 2018–2023.

3.3. Health Risk Assessment at Shanxi Site

3.3.1. The Health Risk of Species

This study assessed the non-carcinogenic health risks of 19 halocarbons. As shown in Figure S4, the hazard index (HI) for non-carcinogenic risk ranged from 4.89 × 10−2 to 9.32 × 10−2, with all species remaining below the threshold set by the U.S. EPA. According to Figure S5, 1,2-dichloropropane and trichloroethylene were the compounds with the highest non-carcinogenic risk levels ranging, from 1.80 × 10−2 to 4.20 × 10−2 and from 1.18 × 10−2 to 4.56 × 10−2, respectively.

To better understand the impact of halocarbons on non-carcinogenic health risks in the YRD, the results from this study were compared with findings from other regions (Figure 4). The Shanxi site also displayed lower health risks in contrast with other regions. However, within the YRD (i.e., Hangzhou and Shanxi), 1,2-dichloropropane and trichloroethylene showed relatively higher non-carcinogenic risks and should be prioritized for future control. Also, the levels of chloroform and chloromethane at the Shanxi site showed a yearly increasing trend. These two halocarbons are widely used as solvents and chemical intermediates in industrial production [17,87].

Figure 4.

Comparison of the non-carcinogenic risk of selected halocarbons between the Shanxi site and other cities. The red line denotes the threshold of 1 and the HQ value exceeding 1 indicates a potential safety concern.

The data from Beijing [13], Zhengzhou [88], Hangzhou [89], and Hong Kong, China [90] are cited in this work. The red line represents a value of 1.

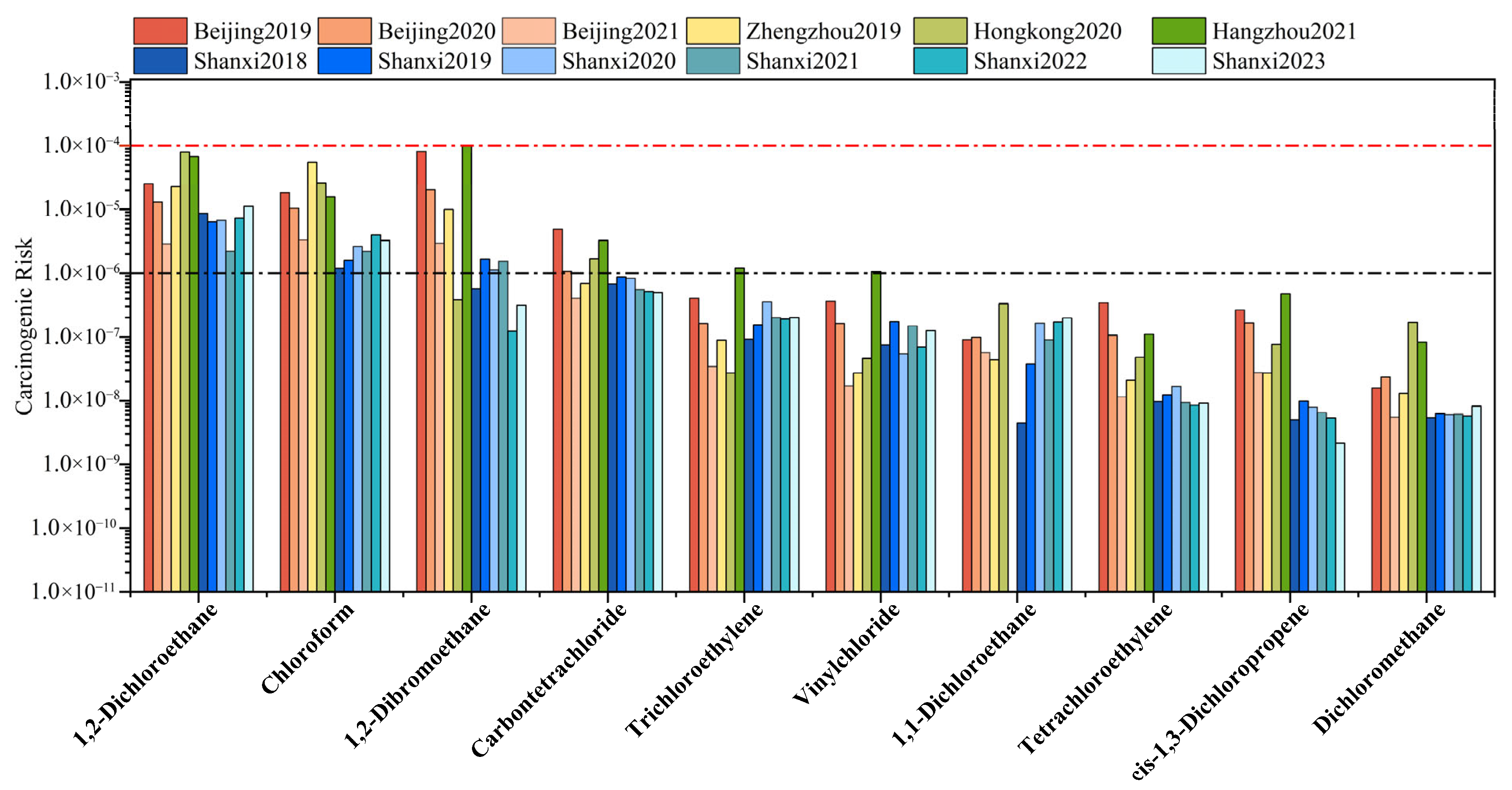

Although the non-carcinogenic risks associated with halocarbons were comparatively minimal at the Shanxi site, local carcinogenic risks remained a significant concern. As shown in Figure S6, none of the species exceeded the tolerable risk level (1.0 × 10−4), though several substances surpassed the acceptable risk threshold (1.0 × 10−6). Among these, chloroform and 1,2-dichloroethane displayed carcinogenic risks persistently exceeding acceptable levels, with risk ranges of 1.20 × 10−6–4.03 × 10−6 and 6.41 × 10−6–1.13 × 10−5, respectively. 1,2-dibromoethane and carbon tetrachloride only exceeded acceptable levels in specific years. Despite declining concentration trends, the atmospheric lifetime of carbon tetrachloride is longer than the lifetimes of chloroform and 1,2-dichloroethane, which can prolong the exposure time compared to non-regulated halocarbons.

Figure 5 presents the comparative carcinogenic risk levels of selected halocarbons for this study and other areas. Although the YRD is one of major emission areas for halocarbons, carcinogenic risks at the Shanxi site remain lower than those in other Chinese cities, indicating regional heterogeneity in halocarbon emissions in the YRD. In other YRD regions, 1,2-dibromoethane demonstrated the highest carcinogenic risk (1.01 × 10−4), while carbon tetrachloride also exceeded acceptable levels. Consequently, the potential impacts from air mass transport originating in these areas require continuous consideration. At the Shanxi site, the carcinogenic risks of trichloroethylene (9.23 × 10−8–3.55 × 10−7) and vinyl chloride (5.44 × 10−8–1.73 × 10−7) surpassed those in Zhengzhou and Hong Kong. These compounds also exceeded acceptable risk levels in Hangzhou (trichloroethylene: 1.20 × 10−6 and vinyl chloride: 1.05 × 10−6). Given their prevalent use as cleaning agents in dry-cleaning and chemical feedstocks [68,91], these halocarbons warrant particular attention.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the carcinogenic risk of selected halocarbons between Shanxi site and other studies. The data from Beijing [13], Zhengzhou [88], Hangzhou [89] and Hong Kong, China [90] are cited in this work. The red and black dotted lines at 10−6 and 10−4 represent the acceptable and tolerable levels of carcinogenic risk, respectively.

The monthly patterns of 1,2-Dichloroethane and chloroform are consistent with total halocarbon concentrations (Figure S7). Although risks declined from June onward, these species exhibited the widest error bar. The post-September period emerged as the highest-risk interval, with lifetime carcinogenic risks reaching 5.54 × 10−6–9.53 × 10−6 for 1,2-dichloroethane and 2.32 × 10−6–3.98 × 10−6 for chloroform, establishing this timeframe as a critical monitoring priority. 1,2-Dibromoethane and carbon tetrachloride exhibited seasonal exceedances of acceptable risk thresholds, with peak carcinogenic risks observed during the June–July period (1,2-dibromoethane in July: 8.78 × 10−7; carbon tetrachloride in June: 1.16 × 10−6). These elevated risks are related to seasonal temperature variation.

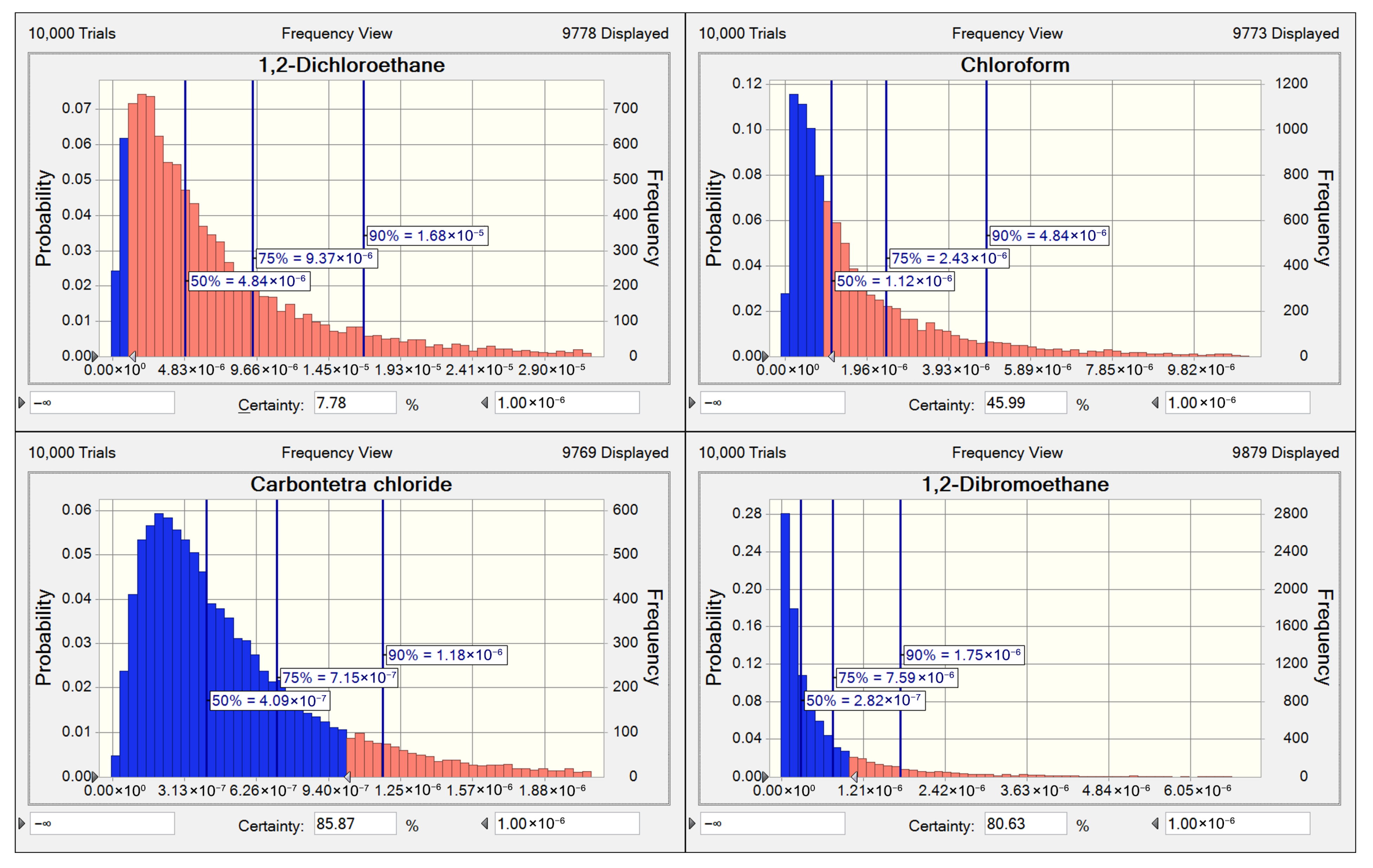

As shown in Figure 6, the 1,2-dichloroethane displayed the highest probability (92.2%) of exceeding the 1 × 10−6 carcinogenic risk threshold among these four compounds, with its 95th percentile risk value standing at 2.33 × 10−5. Chloroform demonstrated a 54.0% probability of surpassing acceptable levels across all years; however, its exceedance probability increased from 69.9% in 2021 to 80.0% in 2023 (Figure S8). It should be of concern at high concentrations. 1,2-dibromoethane and carbon tetrachloride showed lower exceedance probabilities (14.1% and 19.37%). Both compounds demonstrated declining trends in the probability of exceeding the 1 × 10−6 risk threshold during the study period (Figures S9 and S10). Nevertheless, given that carbon tetrachloride is under regulated, investigation into its potential sources remains warranted.

Figure 6.

The distribution of carcinogenic risk of 4 halocarbons during the period of 2018–2023. The red shaded area represents the percentage of carcinogenic risk exceeding 1 × 10−6, while the blue area represents the percentage of risk below this threshold.

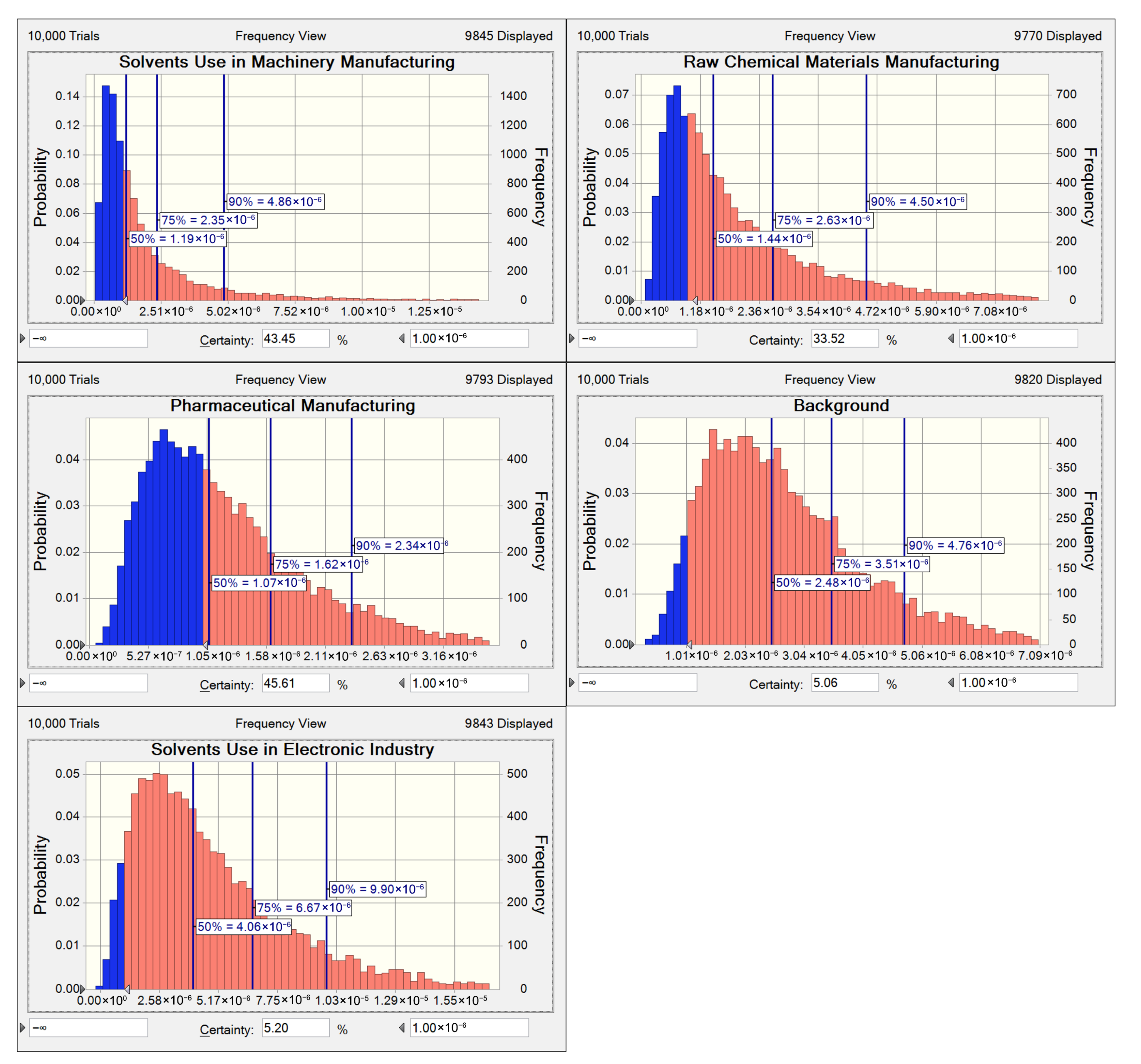

3.3.2. The Health Risk of Sources

Non-carcinogenic risks from all emission sources were under safe thresholds (Figure S11). As shown in Figure 7, carcinogenic risks across sources were prominent conversely. Solvent use in the electronic industry posed the highest carcinogenic risk to humans (9.30 × 10−6–2.07 × 10−5), primarily driven by substantial contributions from chloroform and 1,2-dichloroethane. Previous reports have shown that chloroform and 1,2-dichloroethane are widely used in solvent application and can cause tumors at high dosages in liver and kidneys [92,93]. Background sources ranked second in terms of carcinogenic risk (5.99 × 10−6–1.15 × 10−5). The observed increase in the carcinogenic risk of background sources during 2023 may be attributable to fugitive emissions near the site. Carcinogenic risks from pharmaceutical manufacturing (2.01 × 10−6–8.51 × 10−6) and the manufacturing of raw chemical materials and (1.41 × 10−6–7.05 × 10−6) were comparable. The peak value in pharmaceutical manufacturing in 2023 likely reflects the increased use of chloroform as a feedstock [25,94]. Chemical feedstocks demonstrated a progressive upward carcinogenic risk trend, with comparatively lower levels during 2020–2022 (range: 1.75 × 10−6–2.95 × 10−6), potentially linked to pandemic-induced slowdowns in rubber/plastic-related chemical manufacturing.

Figure 7.

The carcinogenic risk of five halocarbon sources during the period of 2018–2023. The two dashed lines at 10−6 and 10−4 represent the acceptable and tolerable levels of carcinogenic risk.

Background sources and solvent use in electronic industry showed the highest probabilities of exceeding the acceptable risk threshold, reaching 94.9% and 94.8%, respectively (Figure 8). The 95th percentile carcinogenic risk value for solvent use in electronic industry reached 1.26 × 10−5, exceeding other sources by an order of magnitude. The probability of solvent use in the electronic industry exceeding the safety threshold remained within 85.2–97.3% across most years (Figure S12). Background sources demonstrated exceedance probabilities ranging from 12.9% to 90.5% (Figure S13), with increasing trends in both probability and 95th percentile risk values. Therefore, to minimize adverse health outcomes associated with halocarbons exposure, this study recommends implementing controls on emissions from solvent use in the electronic industry. Investigations should be conducted into the impacts of fugitive emission sources and the regional transport of halocarbons across the broader YRD region to inform subsequent risk management strategies.

Figure 8.

The distribution of the carcinogenic risk of five halocarbon sources during the period of 2018–2023. The red shaded area represents the percentage of carcinogenic risk exceeding 1 × 10−6, while the blue area represents the percentage of risk below this threshold.

4. Conclusions

This study conducted the continuous monitoring of 28 halocarbons at the Shanxi site in the central YRD from 2018 to 2023, systematically analyzing their temporal variations and source evolution patterns. The result show that halocarbon concentrations at the Shanxi site showed an overall increasing trend during the period of 2018–2023, with temporarily lower levels in seen 2020–2022 due to pandemic restrictions. Rising trends were primarily driven by elevated contributions from alkyl halides and alkenyl halides, notably dichloromethane, chloromethane, 1,2-dichloroethane, chloroform, and trichloroethylene. Furthermore, the PMF analysis revealed that pharmaceutical manufacturing is the dominant source with relatively stable contributions (37.0–60.2%). In contrast, the manufacturing of raw chemical materials (12.4–24.7%), solvent use in machinery manufacturing (8.0–19.9%) and electronic industry (10.3–13.7%) exhibit increasing contributions, predominantly traced to local emissions. Potential source areas of pharmaceutical manufacturing sources were related to southeastern local emissions, while background sources were primarily attributed to adjacent cities in the YRD region. Health risk assessment indicated that while overall health risks at the Shanxi site were relatively low, significant attention should be drawn to 1,2-dichloropropane, trichloroethylene, 1,2-dichloroethane, and chloroform due to their significant health risk. Additionally, solvent use in electronic industry and background sources are the dominant sources of health risk, with 94.9% and 94.8% probabilities of exceeding the acceptable risk threshold. These findings provide a scientific basis for formulating air quality management strategies, with relevance to the targeted abatement of halocarbon species and sources.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/toxics13121085/s1, Table S1. The Method Detection limit of TH-PKU 300B GC-MS/FID (Unit: ppb). Table S2. Meteorological parameters from 2018 to 2023. Table S3. Rfc and IUR values of halocarbon species in this study. Table S4. The input parameters in Monte Carlo simulation. Table S5. Distribution and parameters of adult outdoor exposure time in urban areas of Zhejiang province. Figure S1. The levels of halocarbons components at Shanxi site in 2018–2023. Figure S2. The month variation in halocarbons at Shanxi site in 2018–2023. Table S6. The characteristics and annual mean contributions of halocarbons at Shanxi site in 2018–2023 (Unit: ppb). Text S1. Source apportionment of halocarbons at Shanxi site. Figure S3. (a) Source profiles of PMF model analysis at Shanxi in 2018–2019. (b) Source profiles of PMF model analysis at Shanxi in 2020–2021. (c) Source profiles of PMF model analysis at Shanxi in 2022–2023. Text S2 Validation of 5-factor solutions for the PMF model. Table S7. The Qtrue/Qrobust and R2 of PMF model in 2018–2023. Text S3. The bootstrap results of six factors from the PMF model. Table S8. BS Test Results of Five Factors of PMF Model. Figure S4. Health index of halocarbons at Shanxi in 2018–2023. Figure S5. The yearly variation in non-carcinogenic risk of 19 halocarbons at Shanxi. Figure S6. The yearly variation in carcinogenic risk of 11 halocarbons at Shanxi. Figure S7 The monthly variation in the carcinogenic risk of 4 halocarbons at the Shanxi site. Figure S8. The yearly variation in carcinogenic risk of chloroform. Figure S9. The yearly variation in carcinogenic risk of carbon tetrachloride. Figure S10. The yearly variation in carcinogenic risk of 1,2-dibromoethane. Figure S11. The non-carcinogenic risk of five halocarbon sources during 2018–2023. Figure S12. The yearly variation in carcinogenic risk of solvent use in electronic industry. Figure S13. The yearly variation in carcinogenic risk of background (References [95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118] are cited in the supplementary materials).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., Y.J. and. A.Z.; methodology, Y.J.; validation, A.Z.; formal analysis, Y.J.; investigation, Q.Z., J.D., L.Z., L.J., D.X. and B.X.; resources, Q.Z., J.D., L.Z., L.J., D.X. and B.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J.; writing—review and editing, A.Z., H.Z. and Y.N.; supervision, X.L.; project administration, B.X. and X.L.; funding acquisition, B.X. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number LZJMZ25D050003; CAE Strategic Research and Consulting Project, China, grant number 2021-JZ-05; Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public-Interest Scientific Institution, China, grant number 2019YSKY-013; National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2024YFC3713704; and National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2022YFC3703505.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| YRD | Yangtze River Delta |

| CFCs | Chlorofluorocarbons |

| HCFCs | Hydrochlorofluorocarbons |

| HFCs | Hydrofluorocarbons |

| ODSs | Ozone Depleting Substances |

| PMF | Positive Matrix Factorization |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| CBPF | Conditional Bivariate Probability Function |

| EPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| FID | Flame Ionization Detection |

| PLOT | Porous Layer Open Tubular |

| MS | Mass Spectrometric |

References

- World Meteorological Organization. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2014. Pursuant to Article 6 of the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer; Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-9966-076-01-4. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Western, L.M.; Saito, T.; Redington, A.L.; Henne, S.; Fang, X.; Prinn, R.G.; Manning, A.J.; Montzka, S.A.; Fraser, P.J.; et al. A Decline in Emissions of CFC-11 and Related Chemicals from Eastern China. Nature 2021, 590, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WMO. WMO Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022; GAW Report No. 278; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-9914-733-97-6. [Google Scholar]

- Halons Technical Options Committee. Report of the Halons Technical Options Committee; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; Volume 1, ISBN 978-9966-076-48-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hossaini, R.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Montzka, S.A.; Rap, A.; Dhomse, S.; Feng, W. Efficiency of Short-Lived Halogens at Influencing Climate through Depletion of Stratospheric Ozone. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Western, L.M.; Say, D.; Chen, L.; Claxton, T.; Ganesan, A.L.; Hossaini, R.; Krummel, P.B.; Manning, A.J.; Mühle, J.; et al. Rapid Increase in Dichloromethane Emissions from China Inferred through Atmospheric Observations. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oram, D.E.; Ashfold, M.J.; Laube, J.C.; Gooch, L.J.; Humphrey, S.; Sturges, W.T.; Leedham-Elvidge, E.; Forster, G.L.; Harris, N.R.P.; Mead, M.I.; et al. A Growing Threat to the Ozone Layer from Short-Lived Anthropogenic Chlorocarbons. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 11929–11941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laube, J.C.; Engel, A.; Bonisch, H.; Mobius, T.; Worton, D.R.; Sturges, W.T.; Grunow, K.; Schmidt, U. Contribution of Very Short-Lived Organic Substances to Stratospheric Chlorine and Bromine in the Tropics—A Case Study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2008, 8, 7325–7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossaini, R.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Saiz-Lopez, A.; Harrison, J.J.; Von Glasow, R.; Sommariva, R.; Atlas, E.; Navarro, M.; Montzka, S.A.; Feng, W.; et al. Growth in Stratospheric Chlorine from Short-lived Chemicals Not Controlled by the Montreal Protocol. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 4573–4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Atlas, E.; Blake, D.; Dorf, M.; Pfeilsticker, K.; Schauffler, S. Convective Transport of Very Short Lived Bromocarbons to the Stratosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 5781–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Geng, F.; Tie, X.; Yu, Q.; An, J. Characteristics and Source Apportionment of VOCs Measured in Shanghai, China. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 5005–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Li, B.; Fang, X. Indoor Volatile Organic Compounds: Concentration Characteristics and Health Risk Analysis on a University Campus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Guo, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wen, Q.; Wei, Y.; et al. Pollution Characteristics and Source Differences of VOCs before and after COVID-19 in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEE List of Key Controlled Emerging Pollutants (2023 Edition). Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gzk/gz/202212/t20221230_1009192.shtml (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. About Urban Air Toxics. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/haps/about-urban-air-toxics (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Fang, X.; Park, S.; Saito, T.; Tunnicliffe, R.; Ganesan, A.L.; Rigby, M.; Li, S.; Yokouchi, Y.; Fraser, P.J.; Harth, C.M.; et al. Rapid Increase in Ozone-Depleting Chloroform Emissions from China. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Western, L.M.; Hu, J.; Yao, B.; Mühle, J.; Ganesan, A.L.; Prinn, R.G.; Krummel, P.B.; Hossaini, R.; Fang, X.; et al. Anthropogenic Chloroform Emissions from China Drive Changes in Global Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 13925–13936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benish, S.E.; Salawitch, R.J.; Ren, X.; He, H.; Dickerson, R.R. Airborne Observations of CFCs Over Hebei Province, China in Spring 2016. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2021, 126, e2021JD035152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claxton, T.; Hossaini, R.; Wilson, C.; Montzka, S.A.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Wild, O.; Bednarz, E.M.; Carpenter, L.J.; Andrews, S.J.; Hackenberg, S.C.; et al. A Synthesis Inversion to Constrain Global Emissions of Two Very Short Lived Chlorocarbons: Dichloromethane, and Perchloroethylene. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD031818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Xu, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Duan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Pollution Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of Summertime Atmospheric Volatile Halogenated Hydrocarbons in a Typical Urban Area of Beijing, China. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Chen, T.; Dong, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Han, G.; Sun, J.; Wu, L.; Gao, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Characteristics and Sources of Halogenated Hydrocarbons in the Yellow River Delta Region, Northern China. Atmos. Res. 2019, 225, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; An, M.; Yu, H.; Ma, Z.; Xu, L.; O’Doherty, S.; Rigby, M.; Western, L.M.; Ganesan, A.L.; Zhou, L.; et al. In Situ Observations of Halogenated Gases at the Shangdianzi Background Station and Emission Estimates for Northern China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7217–7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; So, K.L.; Simpson, I.J.; Barletta, B.; Meinardi, S.; Blake, D.R. C1–C8 Volatile Organic Compounds in the Atmosphere of Hong Kong: Overview of Atmospheric Processing and Source Apportionment. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 1456–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Dang, J.; Guo, H.; Lyu, X.; Simpson, I.J.; Meinardi, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Blake, D.R. Long-Term Temporal Variations and Source Changes of Halocarbons in the Greater Pearl River Delta Region, China. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 234, 117550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Gu, D.; Li, X.; Leung, K.F.; Sun, H.; Mai, Y.; Chan, W.M.; Liang, Z. Characteristics and Source Origin Analysis of Halogenated Hydrocarbons in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 862, 160504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Wu, J.; An, M.; Xu, W.; Fang, X.; Yao, B.; Li, Y.; Gao, D.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J. The Atmospheric Concentrations and Emissions of Major Halocarbons in China during 2009–2019. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, H.; Yao, B.; Pu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Fang, X.; O’Doherty, S.; Chen, L.; He, J. Estimate of Hydrochlorofluorocarbon Emissions during 2011–2018 in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 307, 119517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ho, S.S.H.; Li, X.; Guo, L.; Feng, R.; Fang, X. Pioneering Observation of Atmospheric Volatile Organic Compounds in Hangzhou in Eastern China and Implications for Upcoming 2022 Asian Games. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Hu, L.; Chen, D.; Hu, X.; Feng, R.; Fang, X. Characteristics and Source Apportionment of Some Halocarbons in Hangzhou, Eastern China during 2021. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 865, 160894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Lin, Y.-C.; Li, L.; Xie, F.; Hu, J.; Mozaffar, A.; Cao, F. Source Apportionments of Atmospheric Volatile Organic Compounds in Nanjing, China during High Ozone Pollution Season. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Zou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zuo, H.; Ding, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Jin, L.; Xu, D.; et al. Long-Term Halocarbon Observations in an Urban Area of the YRD Region, China: Characteristic, Sources Apportionment and Health Risk Assessment. Toxics 2024, 12, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, T.; Huang, C.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Hu, G.; Yang, F.; Zhang, L. Characteristics and Health Risks of Benzene Series and Halocarbons near a Typical Chemical Industrial Park. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B.; Lin, H.; Lu, X.; Chen, W. VOCs Fugitive Emission Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment from Typical Plywood Industry in the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Lu, S.; Shao, M. Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Emissions and Health Risk Assessment in Paint and Coatings Industry in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 115740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Du, K. Health Risk-Oriented Source Apportionment of Hazardous Volatile Organic Compounds in Eight Canadian Cities and Implications for Prioritizing Mitigation Strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 12077–12085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TH-PKU 300B GC-MS/FID. Available online: https://www.thyb.cn/en/index.aspx (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Wang, M.; Zeng, L.; Lu, S.; Shao, M.; Liu, X.; Yu, X.; Chen, W.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, M.; et al. Development and Validation of a Cryogen-Free Automatic Gas Chromatograph System (GC-MS/FID) for Online Measurements of Volatile Organic Compounds. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 9424–9434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US. EPA Compendium Method TO-15. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-11/documents/to-15r.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- WS500-UMB Smart Weather Sensor. Available online: https://www.lufft.com/products/compact-weather-sensors-293/ws500-umb-smart-weather-sensor-1842/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Positive Matrix Factorization Model for Environmental Data Analyses. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/air-research/positive-matrix-factorization-model-environmental-data-analyses (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Paatero, P.; Tapper, U. Analysis of Different Modes of Factor Analysis as Least Squares Fit Problems. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1993, 18, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Man, H.; Qi, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H.; Jing, S.; He, T.; Wang, S.; et al. Measurement and Minutely-Resolved Source Apportionment of Ambient VOCs in a Corridor City during 2019 China International Import Expo Episode. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Risk Evaluation for 1,3-Butadiene. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/risk-evaluation-13-butadiene (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Gu, Y.; Liu, B.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Feng, Y.; Hopke, P.K. Multiply Improved Positive Matrix Factorization for Source Apportionment of Volatile Organic Compounds during the COVID-19 Shutdown in Tianjin, China. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.; Chakraborty, A.; Mandariya, A.K.; Gupta, T. Composition and Source Apportionment of PM1 at Urban Site Kanpur in India Using PMF Coupled with CBPF. Atmos. Res. 2016, 178–179, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Cheng, H.R.; Ling, Z.H.; Louie, P.K.K.; Ayoko, G.A. Which Emission Sources Are Responsible for the Volatile Organic Compounds in the Atmosphere of Pearl River Delta? J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 188, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Ma, T.; Gao, Z.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Xue, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, J. Characteristics and Sources of Volatile Organic Compounds during High Ozone Episodes: A Case Study at a Site in the Eastern Guanzhong Plain, China. Chemosphere 2021, 265, 129072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, D.C.; Ropkins, K. Openair—An R Package for Air Quality Data Analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2012, 27–28, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Integrated Risk Information System. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/iris (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Guiding Principles for Monte Carlo Analysis. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/guiding-principles-monte-carlo-analysis (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of People’s Republic of China. MEE The Chinese Exposure Factors Handbook (Adults); China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2013; ISBN 978-7-5111-1592-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, P.; Li, C.; Wang, G.; Hou, D.; Zhang, X.; et al. Drivers and Impacts of Decreasing Concentrations of Atmospheric Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in Beijing during 2016–2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of the State Council; PRC. China Extends Holidays, Strengthens Control of Coronavirus Epidemic. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/policywatch/202001/27/content_WS5e2ea828c6d019625c60400f.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Ministry of Emergency Management of the People's Republic of China. Available online: https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/gdyj/202002/t20200221_344620.shtml (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- NCC National Climate Center. Available online: http://cmdp.ncc-cma.net/influ/moni_china.php (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Zhang, G.; Mu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Seasonal and Diurnal Variations of Atmospheric Peroxyacetyl Nitrate, Peroxypropionyl Nitrate, and Carbon Tetrachloride in Beijing. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Chen, C.H.; Wang, Q.; Huang, C.; Su, L.Y.; Huang, H.Y.; Lou, S.R.; Zhou, M.; Li, L.; Qiao, L.P.; et al. Chemical Loss of Volatile Organic Compounds and Its Impact on the Source Analysis through a Two-Year Continuous Measurement. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 80, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Bi, J.; Liu, Q.; Ling, Z.; Shen, G.; Chen, F.; Qiao, Y.; Li, C.; Ma, Z. Sources of Volatile Organic Compounds and Policy Implications for Regional Ozone Pollution Control in an Urban Location of Nanjing, East China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 3905–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Yu, X.; Zhou, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Dong, H.; Liao, K.; Chen, Q.; et al. Spatiotemporal Variation, Sources, and Secondary Transformation Potential of Volatile Organic Compounds in Xi’an, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 4939–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Park, M.-K.; Jo, C.O.; Park, S. Emission Estimates of Methyl Chloride from Industrial Sources in China Based on High Frequency Atmospheric Observations. J. Atmos. Chem. 2017, 74, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Hu, X.; Hu, L.; Chen, D.; An, M.; Yang, Y.; Feng, R.; Guo, L.; et al. Emission Factors of Ozone-Depleting Chloromethanes during Production Processes Based on Field Measurements Surrounding a Typical Chloromethane Plant in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Geng, F.-H.; Sang, X.-F.; Chan, C.-Y.; Chan, L.-Y.; Yu, Q. Characteristics and Sources of Non-Methane Hydrocarbons and Halocarbons in Wintertime Urban Atmosphere of Shanghai, China. Env. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 5957–5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxicological Profile for Chloromethane; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological Profiles; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023.

- Yao, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z. Ambient Volatile Organic Compounds in a Heavy Industrial City: Concentration, Ozone Formation Potential, Sources, and Health Risk Assessment. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021, 12, 101053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Yan, Q.; Han, S.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, R. Typical Industrial Sector-Based Volatile Organic Compounds Source Profiles and Ozone Formation Potentials in Zhengzhou, China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ji, Y.; Wu, Z.; Peng, L.; Bao, J.; Peng, Z.; Li, H. Atmospheric Volatile Halogenated Hydrocarbons in Air Pollution Episodes in an Urban Area of Beijing: Characterization, Health Risk Assessment and Sources Apportionment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Bari, M.A.; Xing, Z.; Du, K. Ambient Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in Two Coastal Cities in Western Canada: Spatiotemporal Variation, Source Apportionment, and Health Risk Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossaini, R.; Sherry, D.; Wang, Z.; Chipperfield, M.; Feng, W.; Oram, D.; Adcock, K.; Montzka, S.; Simpson, I.; Mazzeo, A.; et al. On the Atmospheric Budget of Ethylene Dichloride and Its Impact on Stratospheric Chlorine and Ozone (2002–2020). EGUsphere 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. Advances in Clinical Research Due to Occupational Hazards Trichlorethylene. Chin. J. Urban Rural Enterp. Hyg. 2015, 30, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Li, G.; Bai, H.; Liu, X.; Shao, X. Emission Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of Volatile Organic Compounds from Electronics-Manufacturing Industry. China Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 1074–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, K.; Chen, H.; Feng, J. Investigation on Occupational Hazards of 202 Electronic Enterprises in a City in Guangdong Province. Occup. Health Emerg. Rescue 2024, 42, 45–48+62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J. Separation of 1,1-Dichloroethane from High-Boiling Residue in Vinyl Chloride Synthesis. Polyvinyl Chloride 2001, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Guo, X.; Bai, H. Determination of 1,1-Dichloroethlane and 1,2-Dichloroethlane in Textiles by Headspace Gas Chromatography. Phys. Test. Chem. Anal. Part B Chem. Anal. 2015, 51, 1430–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zou, Q.; Jin, L.; Shen, Y.; Shen, J.; Xu, B.; Qu, F.; Zhang, F.; Xu, J.; Pei, X.; et al. Characteristics and Sources of Ambient Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) at a Regional Background Site, YRD Region, China: Significant Influence of Solvent Evaporation during Hot Months. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxicological Review for 1,3-DICHLOROPROPENE (CAS No. 542-75-6). Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/static/pdfs/0224tr.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture of the PRC. Announcement No. 199 of the Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/ncpzxzz/flfg/200709/t20070919_893058.htm (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Economy and Information of Technology Department of Zhejiang. Several Opinions on Promoting the High-Quality Development of the Pharmaceutical Industry in Zhejiang Province. Available online: https://jxt.zj.gov.cn/art/2021/1/7/art_1229123418_4420281.html (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Xue, B.; Guo, X.; Cao, J.; Yang, S.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z. The Occurrence, Ecological Risk, and Control of Disinfection by-Products from Intensified Wastewater Disinfection during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Song, G.; Bi, Y.; Gao, W.; He, A.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, G. Occurrence and Distribution of Disinfection Byproducts in Domestic Wastewater Effluent, Tap Water, and Surface Water during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4103–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xue, L.; Liu, J. Types, Hazards and Pollution Status of Chlorinated Disinfection By-Products in Surface Water. Res. Environ. Sci. 2020, 33, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Fang, C.; Deng, Y.; Xu, Z. Intensified Disinfection Amid COVID-19 Pandemic Poses Potential Risks to Water Quality and Safety. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4084–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Ou, R.; Liu, M.; Lu, Q.; Ye, D. Historical Volatile Organic Compound Emission Performance, Drivers, and Mitigation Potential for Automobile Manufacturing in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiaxing Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Jiaxing Statistical Yearbook. Available online: https://tjj.jiaxing.gov.cn/col/col1512382/index.html#reloaded (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Economy and Information of Technology Department of Zhejiang. Economic Operation Analysis of the Electronic Information Industry of Zhejiang Province in 2020. Available online: https://jxt.zj.gov.cn/art/2021/3/8/art_1657978_58926210.html (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Wu, K.; Duan, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Z.; Tan, Q.; Song, D.; Lu, C.; Deng, Y. Sources Profiles of Anthropogenic Volatile Organic Compounds from Typical Solvent Used in Chengdu, China. J. Environ. Eng. 2020, 146, 05020006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Weng, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; Xu, J.; Zheng, L.; Su, Y.; Wu, D.; Yan, W.; Zhang, J.; et al. Ozone-Depleting Substances Unintendedly Emitted From Iron and Steel Industry: CFCs, HCFCs, Halons and Halogenated Very Short-Lived Substances. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2024JD041035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yao, B.; Fang, X. Anthropogenic Emissions of Ozone-Depleting Substance CH3Cl during 2000–2020 in China. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 310, 119903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, B.; Yuan, M.; Yu, S.; Yin, S.; Zhang, R. Characteristics, Sources and Health Risks Assessment of VOCs in Zhengzhou, China during Haze Pollution Season. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 108, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X. Characteristics, Emission Sources and Health Risk Study of Atmospheric Volatile Halocarbons in Hangzhou. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Y.K.; Chan, W.W.; Gu, D.; Wong, T.W.; Chan, K.J.D.; Yu, J.Z.; Lau, A.K.H. Characterization of Toxic Air Pollutants in Hong Kong, China: Two-Decadal Trends and Health Risk Assessments. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 314, 120129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Chen, T.; Dong, C.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Bi, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, T.; et al. Long-Term Trends and Sources of Atmospheric Halocarbons at Mount Taishan, Northern China. Environ. Sci. 2022, 43, 723–734. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, S.; Arora, S. Chloroform: Risk Assessment, Environmental, and Health Hazard. In Hazardous Chemicals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 439–451. ISBN 978-0-323-95235-4. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; incorporating the first addendum; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-154995-0. [Google Scholar]

- MEE Emission Standard of Air Pollutants for Pharmaceutical Industry. Available online: https://sthjt.zj.gov.cn/art/2022/1/27/art_1201911_58931099.html (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Smith, R.L. Use of Monte Carlo Simulation for Human Exposure Assessment at a Superfund Site. Risk Anal. 1994, 14, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, H. Study on VOCs Emission Inventory and Characteristics of Vehicle Maintenance Industry in Tianjin. Guangzhou Chem. Ind. 2017, 45, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Z.; Lu, S.; Li, Y.; Shao, M.; Qu, H. Emission Characteristics of Volatile Organic Compounds(VOCs) from Typical Solvent Use Factories in Beijing. China Environ. Sci. 2015, 35, 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Guha, N.; Loomis, D.; Grosse, Y.; Lauby-Secretan, B.; Ghissassi, F.E.; Bouvard, V.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Baan, R.; Mattock, H.; Straif, K. Carcinogenicity of Trichloroethylene, Tetrachloroethylene, Some Other Chlorinated Solvents, and Their Metabolites. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 1192–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ding, A.J.; Wang, T.; Simpson, I.J.; Blake, D.R.; Barletta, B.; Meinardi, S.; Rowland, F.S.; Saunders, S.M.; Fu, T.M.; et al. Source Origins, Modeled Profiles, and Apportionments of Halogenated Hydrocarbons in the Greater Pearl River Delta Region, Southern China. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, 2008JD011448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipperfield, M.P.; Hossaini, R.; Montzka, S.A.; Reimann, S.; Sherry, D.; Tegtmeier, S. Renewed and Emerging Concerns over the Production and Emission of Ozone-Depleting Substances. Nat. Rev. Earth Env. 2020, 1, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Sun, X.; Xu, J.; Ye, D. Improved Emissions Inventory and VOCs Speciation for Industrial OFP Estimation in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 1,3-Butadiene, Ethylene Oxide, and Vinyl Halides (Vinyl Flouride, Vinyl Chloride, and Vinyl Bromide); IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France; Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; ISBN 978-92-832-1297-3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Gu, X.; Cai, M.; Zhao, W.; Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, X. Emission Characteristics, Environmental Impacts and Health Risk Assessment of Volatile Organic Compounds from the Typical Chemical Industry in China. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 149, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Jing, D.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Wang, Q. Process-Based VOCs Source Profiles and Contributions to Ozone Formation and Carcinogenic Risk in a Typical Chemical Synthesis Pharmaceutical Industry in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, W.; Chen, J.; An, T. Underestimated Contribution of Fugitive Emission to VOCs in Pharmaceutical Industry Based on Pollution Characteristics, Odorous Activity and Health Risk Assessment. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 126, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Ji, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, G.; Hou, Y.; Fan, L.; Ye, D.; Huang, H. Comparison of Emission Characteristics and Risk Assessment of Volatile Organic Compounds of Typical Pharmaceutical Industries in Central Plains, China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 16, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G. Studies on the Pollution Characteristics of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) from Pharmaceutical Industry. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Science and Technology, Shijiazhuang, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer|Ozone Secretariat. Available online: https://ozone.unep.org/treaties/montreal-protocol/montreal-protocol-substances-deplete-ozone-layer (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Lin, Y.; Gong, D.; Lv, S.; Ding, Y.; Wu, G.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, B. Observations of High Levels of Ozone-Depleting CFC-11 at a Remote Mountain-Top Site in Southern China. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.A.; Midgley, P.M. The Production and Release to the Atmosphere of CFCs 113, 114 and 115. Atmos. Environment. Part A. Gen. Top. 1993, 27, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.J.; Sax, N.I. Sax’s Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-471-47662-7. [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological Profile For 1,1-Dichloroethane; Foreword; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US): Atlanta GA, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591211/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Wu, J.; Fang, X.; Xu, W.; Wan, D.; Shi, Y.; Su, S.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J. Chlorofluorocarbons, Hydrochlorofluorocarbons, and Hydrofluorocarbons in the Atmosphere of Four Chinese Cities. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 75, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Shao, X.; Li, Z.; Nie, L.; Li, G. Sector-Based Volatile Organic Compounds Emission Characteristics from the Electronics Manufacturing Industry in China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021, 12, 101097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, X. Emission Characteristics and Emission Reduction Potential of Volatile Organic Compounds from Typical Industrial Sources in Jiangsu Province. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 2024, 18, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. On Emission Characteristics and Prevention Countermeasures of the Electronics Industry Waste VOCs. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 39, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAC, PRC Limits for Volatile Organic Compounds Content in Cleaning Agents. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=FE1FC015A8AC8E87F74085C3ADE06C3E (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Toxicological Profile for 1,2-Dibromoethane; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US): Atlanta GA, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591108/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).