Composition, Sources, and Health Risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Commonly Consumed Fish and Crayfish from Caohai Lake, Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

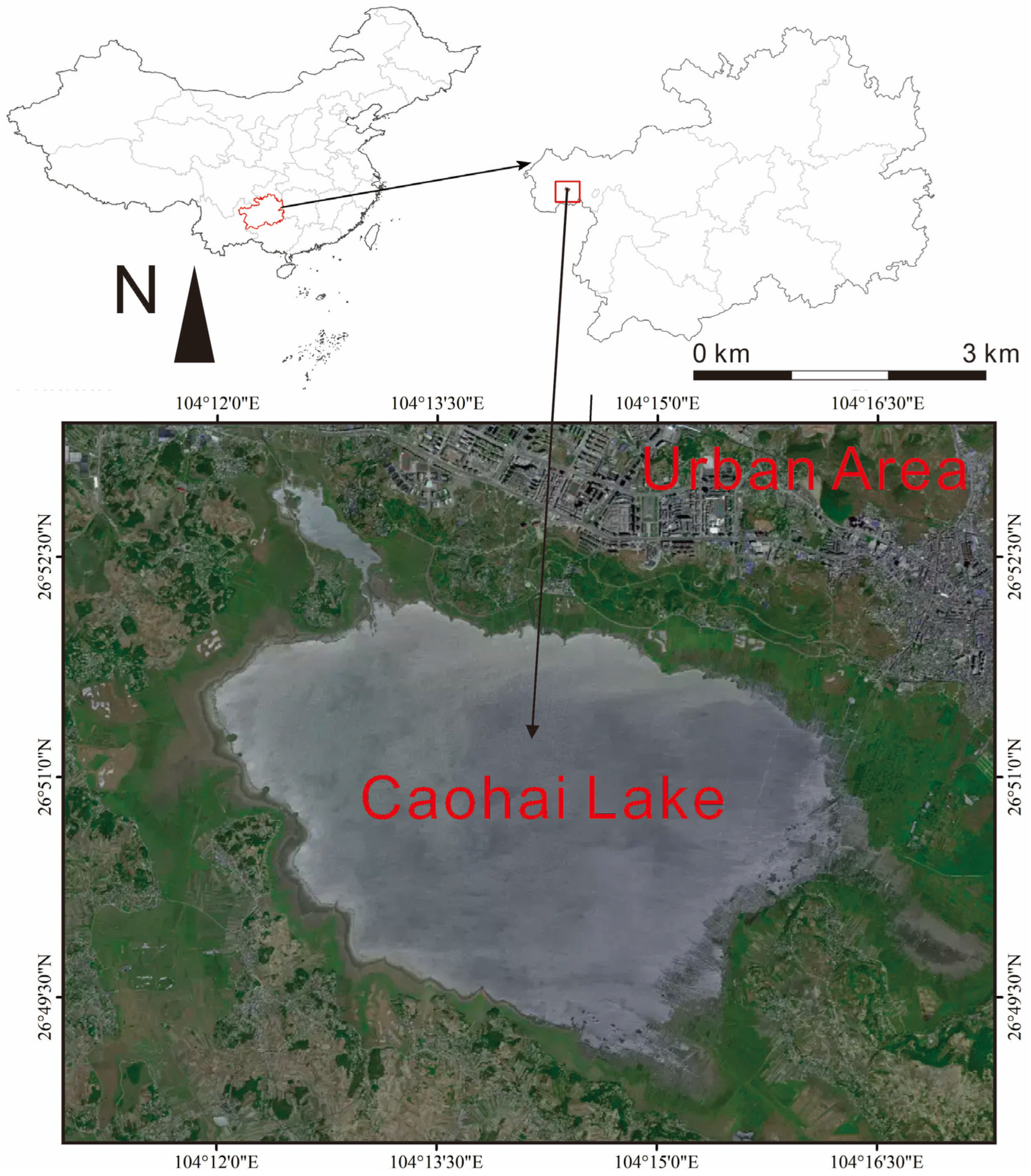

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. The Collection, Preparation and Analysis of the Samples

2.3. Quality Assurance and Quality Control

2.4. The Health Risk Assessment of PAHs

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

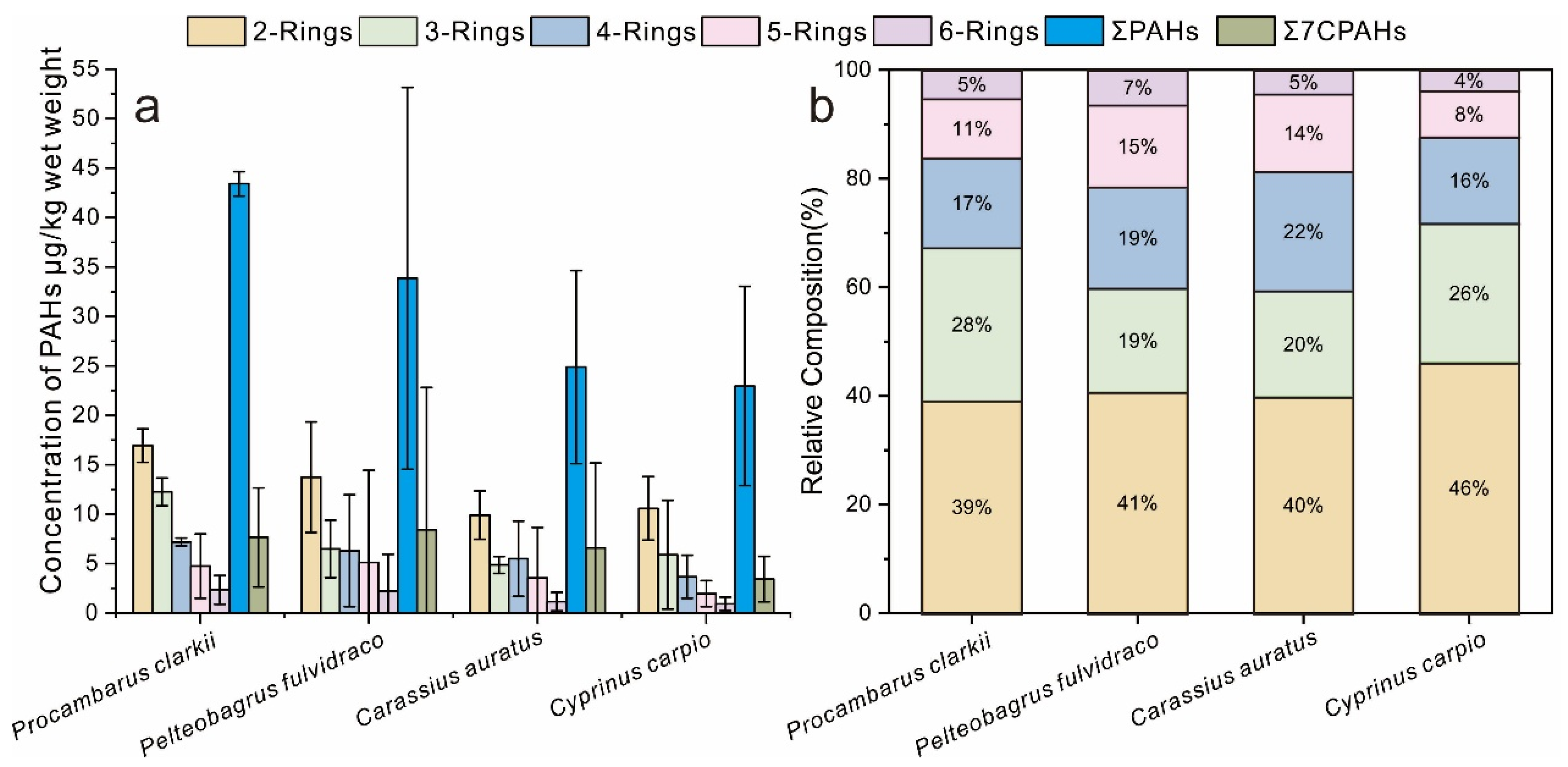

3.1. The Bioaccumulation of PAHs in Dominant Aquatic Products

3.2. PAH Accumulation in Different Aquatic Species

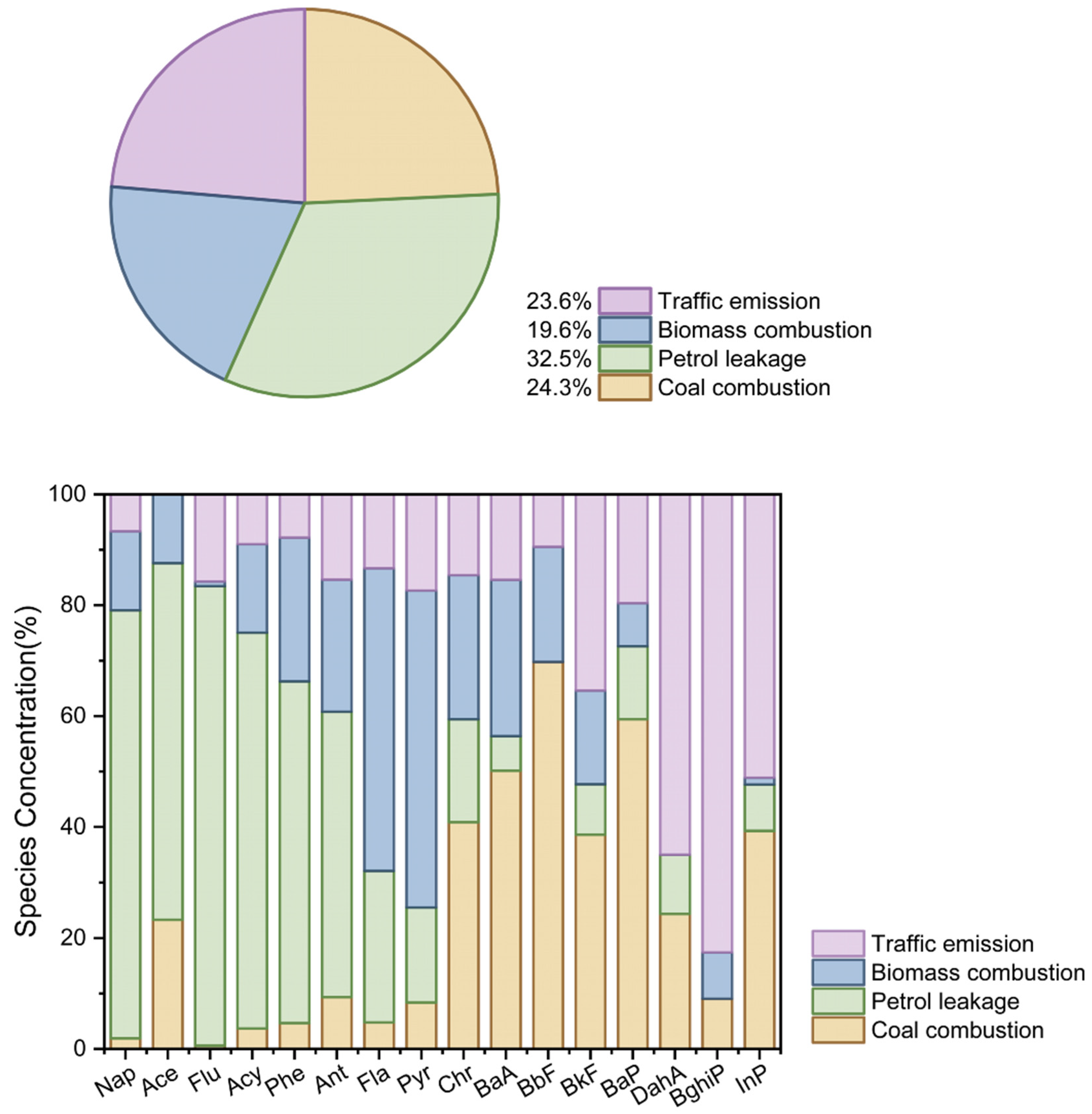

3.3. The Source Identification of PAHs in Aquatic Species of Caohai Lake

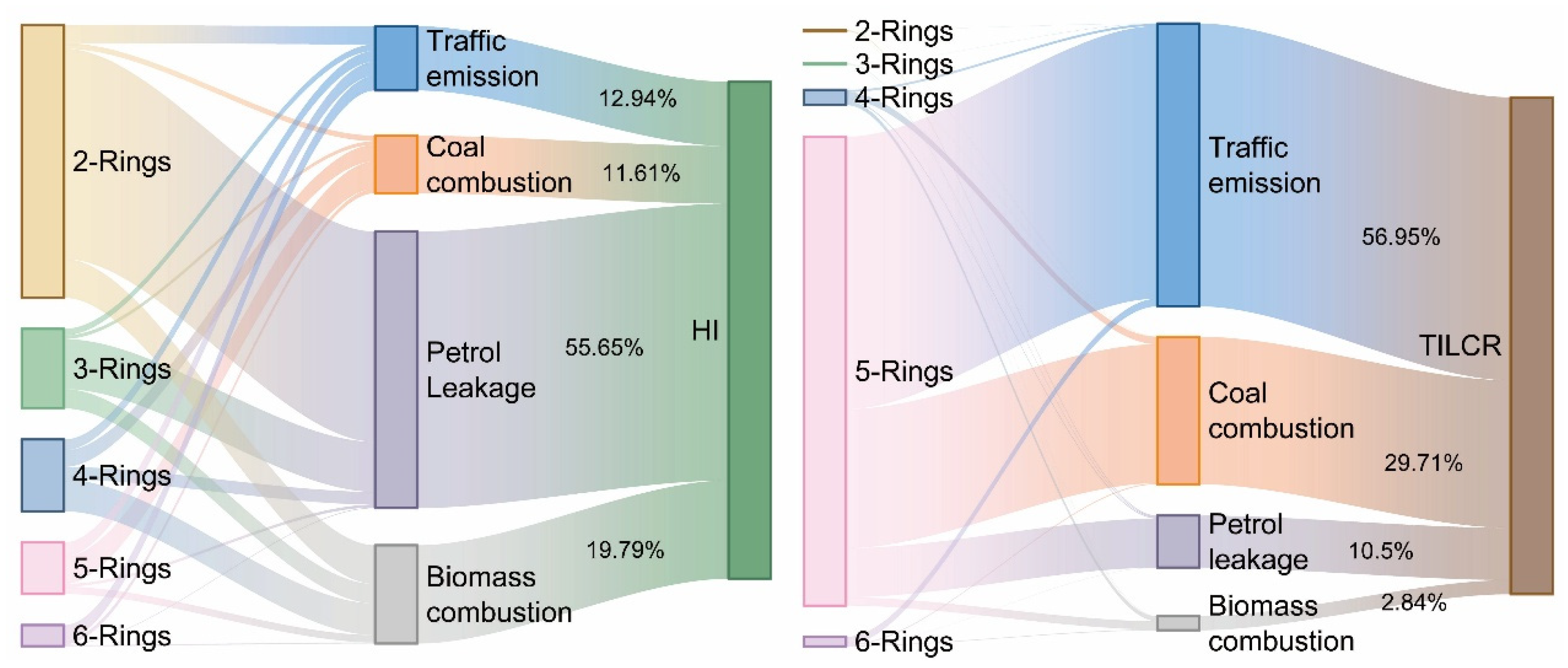

3.4. The Health Risk of PAH Bioaccumulation in Aquatic Species

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EPA, E. Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) 5.0-Fundamentals and User Guide; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Maletić, S.P.; Beljin, J.M.; Rončević, S.D.; Grgić, M.G.; Dalmacija, B.D. State of the art and future challenges for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons is sediments: Sources, fate, bioavailability and remediation techniques. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 365, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bzdusek, P.A.; Christensen, E.R.; Li, A.; Zou, Q. Source apportionment of sediment PAHs in Lake Calumet, Chicago: Application of factor analysis with nonnegative constraints. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Jang, J.-K.; Scheff, P.A. Application of EPA CMB8. 2 model for source apportionment of sediment PAHs in Lake Calumet, Chicago. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 2958–2965. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.B.; Shaikh, S.; Jain, K.R.; Desai, C.; Madamwar, D. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Sources, toxicity, and remediation approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 562813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, X.; Hao, Y.; Cai, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, J. The distribution, sources and health risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in sediments of Liujiang River Basin: A field study in typical karstic river. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjahan, M.; Taslima, K.; Rahman, M.S.; Al-Emran, M.; Alam, S.I.; Faggio, C. Effects of heavy metals on fish physiology—A review. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Wei, X.; Zhao, X.; Hao, Y.; Bao, W. The Bioaccumulation, Fractionation and Health Risk of Rare Earth Elements in Wild Fish of Guangzhou City, China. Animals 2024, 14, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Hao, Y.; Tang, X.; Xie, Z.; Liu, L.; Luo, S.; Huang, Q.; Zou, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, J. Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic and essential elements of the wild fish caught by anglers in Liuzhou as a large industrial city of China. Chemosphere 2020, 243, 125337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Cai, J.; Song, Z.; Liao, X.; Chen, X.; Miao, X. Bioaccumulation, contamination and health risks of trace elements in wild fish in Chongqing City, China: A consumer guidance regarding fish size. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 467. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, H. The Size Screening Could Greatly Degrade the Health Risk of Fish Consuming Associated to Metals Pollution—An Investigation of Angling Fish in Guangzhou, China. Toxics 2023, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Hao, Y.; Liu, H.; Xie, Z.; Miao, D.; He, X. Effects of heavy metals speciations in sediments on their bioaccumulation in wild fish in rivers in Liuzhou—A typical karst catchment in southwest China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 214, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hong, X.; Song, H.; Zhang, T.; Chen, K.; Chu, J. Exploring source-specific ecological risks of PAHs near oil platforms in the Yellow River Estuary, Bohai Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 207, 116870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Song, M.; Wenfang, C.; Chaowei, L.; Qian, B.; Fan, X.; Hailong, S.; Yundi, H.; et al. Relationships between biomass of phytoplankton and submerged macrophytes and physicochemical variables of water in Lake Caohai, China: Implication for mitigation of cyanobacteria blooms by CO2 fertilization. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 129111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, X.; Yang, T.; An, S. Ecological risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in the sediment of a protected karst plateau lake (Caohai) wetland in China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 201, 116199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, T.; Jin, B.; Wang, Q.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhou, J.; et al. A review on occurrence and risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in lakes of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2497–2506. [Google Scholar]

- Gaurav, G.K.; Mehmood, T.; Kumar, M.; Cheng, L.; Sathishkumar, K.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, D. Review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) migration from wastewater. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2021, 236, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, X.; Yang, T.; An, S. Increasing trends in heavy metal risks in the Caohai Lake sediments from 2011 to 2022. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X. Distribution and migration characteristics of microplastics in farmland soils, surface water and sediments in Caohai Lake, southwestern plateau of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Z. Spatial and temporal dynamics of fragmentation and an ecosystem health assessment of plateau blue landscapes: A case study of the Caohai wetland. CATENA 2025, 250, 108730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Chen, Z.; Yan, H.; Xu, A.; Li, F. Characterization of organic pollution in the Dianchi Caohai Lake at the transition between the dry and rainy seasons. Water Cycle 2024, 5, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Yu, L.; Yan, L.; Yang, D. Assessment of some trace elements accumulation in Karst lake sediment and Procambarus clarkii, in Guizhou province, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 237, 113536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Ma, L.; Yi, Y.; Lin, T. Assessment of heavy metal pollution and exposure risk for migratory birds—A case study of Caohai wetland in Guizhou Plateau (China). Environ. Pollut. 2021, 275, 116564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. USEPA 1992 Guidelines for Exposure Assessment; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1992.

- Shukla, S.; Khan, R.; Bhattacharya, P.; Devanesan, S.; AlSalhi, M.S. Concentration, source apportionment and potential carcinogenic risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in roadside soils. Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yang, T.; Hao, Y.; Li, J.; Du, B.; Yang, S.; Miao, X. Heavy Metals in the Soil–Coffee System of Pu’er, China, a Major Coffee Producing Region in China: Distribution and Health Risks. Toxics 2025, 13, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Wei, X.; Hao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, X. The sources of bioavailable toxic metals in sediments regulated their aggregated form, environmental responses and health risk-a case study in Liujiang River Basin, China. Water Res. 2025, 278, 123369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Chen, L.; Hao, Y.; An, J.; Xu, T.; Bao, W.; Chen, X.; Liao, X.; Xie, Y. The variations of heavy metals sources varied their aggregated concentration and health risk in sediments of karst rivers—A case study in Liujiang River Basin, Southwest China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 201, 116171. [Google Scholar]

- MEPC. Exposure Factors Handbook of Chinese Population; Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China, China Environmental Press: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Amarillo, A.C.; Busso, I.T.; Carreras, H. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban environments: Health risk assessment by age groups. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 195, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shu, Y.; Kuang, Z.; Han, Z.; Wu, J.; Huang, X.; Song, X.; Yang, J.; Fan, Z. Bioaccumulation and potential human health risks of PAHs in marine food webs: A trophic transfer perspective. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 485, 136946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajković, I.; Sentić, M.; Miletić, A. Source apportionment and probabilistic health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediment from an urban shallow lake. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 6071–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Y.; Bi, B.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Lu, S. Pollution characteristics and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in fish of typical lakes in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Environ. Chem. 2025, 43, 4082–4092. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Feng, Y.; Hu, T.; Xu, X.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Song, C.; et al. Antibiotics and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in marine food webs of the Yellow River Estuary: Occurrence, trophic transfer, and human health risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 943, 173709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Geng, T.; Peng, S.; Lai, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, H. A systematic toxicologic study of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on aquatic organisms via food-web bioaccumulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recabarren-Villalón, T.; Ronda, A.C.; Oliva, A.L.; Cazorla, A.L.; Marcovecchio, J.E.; Arias, A.H. Seasonal distribution pattern and bioaccumulation of Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in four bioindicator coastal fishes of Argentina. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.M.M.; Saiba, A.I.; Faed, T.A.; Rahman, L.; Bakar, M.A.; Kundu, G.K. Investigation of the accumulation and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and mercury (Hg) in marine fish from the northern Bay of Bengal using a multi-tool approach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2026, 222, 118633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.M.; Carreira, R.S.; Filho, J.S.R.; Rocha, P.P.; Santana, F.M.; Yogui, G.T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in fishery resources affected by the 2019 oil spill in Brazil: Short-term environmental health and seafood safety. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 175, 113334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aborisade, A.B.; Adetutu, A.; Adegbola, P.I. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons distribution in fish tissues and human health risk assessment on consumption of four fish species collected from Lagos Lagoon, Nigeria. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 122740–122754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohiozebau, E.; Tendler, B.; Codling, G.; Kelly, E.; Giesy, J.P.; Jones, P.D. Potential health risks posed by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in muscle tissues of fishes from the Athabasca and Slave Rivers, Canada. Environ. Geochem. Health 2017, 39, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storelli, M.M.; Barone, G.; Perrone, V.G.; Storelli, A. Risk characterization for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and toxic metals associated with fish consumption. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 31, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Yang, M.; Lu, J.; Yin, L.; Shao, L.; Hilton, J.; Bond, D.P.G.; Dai, S. Sedimentary environment controls on critical metals enrichment in late Permian coal measures in western Guizhou, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 186, 106824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Wu, F.-X.; Gu, Y.-G.; Huang, H.-H.; Gong, X.-Y.; Liao, X.-L. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the intertidal sediments of Pearl River Estuary: Characterization, source diagnostics, and ecological risk assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; He, B.; Wu, X.; Simonich, S.L.M.; Liu, H.; Fu, J.; Chen, A.; Liu, H.; Wang, Q. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban stream sediments of Suzhou Industrial Park, an emerging eco-industrial park in China: Occurrence, sources and potential risk. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 214, 112095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, X.; Liang, J.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, H. The Influence of the Reduction in Clay Sediments in the Level of Metals Bioavailability—An Investigation in Liujiang River Basin after Wet Season. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhou, X.; Miao, X. Seasonal Variation Characteristics of Heavy Metal Enrichment in Sediments and Environmental Risk Assessment in the Liujiang River Basin. Geol. China 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Miao, X.; Song, M.; Zhang, H. The Bioaccumulation and Health Risk Assessment of Metals among Two Most Consumed Species of Angling Fish (Cyprinus carpio and Pseudohemiculter dispar) in Liuzhou (China): Winter Should Be Treated as a Suitable Season for Fish Angling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Length (cm) | Weight (g) | Feeding | Living | Num |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelteobagrus fulvidraco | 13~22.8 | 25.8~104.7 | Omnivorous | Demersal | 19 |

| Carassius auratus | 17.5~21.8 | 70.5~168.2 | Omnivorous | Demersal | 23 |

| Cyprinus carpio | 17~26 | 68.5~2080 | Omnivorous | Demersal | 24 |

| Procambarus clarkii | 10–15 | 35–50 | Omnivorous | Demersal | 18 |

| Parameters | Unit | Adult |

|---|---|---|

| Average body weight (BW) | kg | 60 |

| The concentration of PAH i (Ci) | mg/kg | - |

| Exposure duration (ED) | years | (30, 70) |

| Average time of exposure (AT) | day | 365 × ED (Non-carcinogenic) |

| 365 × 70 (Carcinogenic) | ||

| Exposure frequency (EF) | day·year−1 | 365 |

| Carcinogenic slope factor (CSF) | dimensionless | 7.3 (Non-carcinogenic) |

| Intake rate (IR) | g·person−1·day−1 | 49.3 |

| PAHs | Abbreviation | TEF a | RfD b | CSF c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naphthalene | Nap | 0.001 | 0.02 | – |

| Acenaphthene | Acy | 0.001 | 0.06 | – |

| Fluorene | Ace | 0.001 | 0.06 | – |

| Acenaphthylene | Flu | 0.001 | 0.04 | – |

| Phenanthrene | Phe | 0.001 | 0.03 | – |

| Anthracene | Ant | 0.01 | 0.3 | – |

| Fluoranthene | Fla | 0.001 | 0.04 | – |

| Pyrene | Pyr | 0.001 | 0.03 | – |

| Benzo[a]anthracene | BaA | 0.1 | 0.03 | – |

| Chrysene | Chry | 0.01 | 0.03 | – |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | BbF | 0.1 | 0.03 | – |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | BkF | 0.1 | 0.03 | – |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | BaP | 1 | 0.03 | 7.3 |

| Dibenzo[a,h]anthracene | DahA | 5 | 0.03 | – |

| Indeno [123-cd]pyrene | InP | 0.01 | 0.03 | – |

| Benzo[ghi]perylene | BghiP | 0.1 | 0.03 | – |

| Rings | Abb | Range | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Nap | 6.1~21.4 | 11.1 | 3.9 |

| 2 | Ace | 0.1~0.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 3 | Flu | 0.04~0.45 | 0.19 | 0.11 |

| 3 | Acy | 0.4~1.8 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| 3 | Phe | 1.3~10.2 | 4.3 | 2.1 |

| 3 | Ant | 0.2~14.5 | 0.8 | 2.3 |

| 4 | Fla | 0.5~4.7 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

| 4 | Pyr | 0.3~4.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| 4 | BaA | 0.2~5.9 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| 4 | Chr | 0.2~6.7 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| 5 | BbF | 0.2~10.2 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| 5 | BkF | 0.1~6.5 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| 5 | BaP | 0.03~5.3 | 0.37 | 0.91 |

| 5 | DahA | 0.03~6.35 | 0.67 | 1.08 |

| 6 | InP | 0.06~5.33 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| 6 | BghiP | 0.05~5.29 | 0.54 | 0.92 |

| ΣPAHs | 10.3~73.3 | 26.7 | 12.9 | |

| Σ7CPAHsd | 1.3~41.0 | 5.5 | 7.9 |

| Country | Study Area | Year | Matrix | ΣPAHs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Yangtze River Basin | 2021 | Fish and shellfish | 33.91 | [33] |

| China | Yellow River Estuary | 2023 | Fish | 145.9 | [34] |

| China | Pearl River Basin | 2024 | Fish | 42.25 | [35] |

| Argentina | Bahía Blanca estuary | 2015–2016 | Fish and shellfish | 36 | [36] |

| Bangladesh | Bay of Bengal, Chattogram | 2024 | Fish and shellfish | 0.15~67.69 | [37] |

| Brazil | The coast of Pernambuco | 2019 | Finfish and shellfish | 8.71~418 | [38] |

| Nigeria | Makoko Fish Landing Site, Lagos Lagoon, Lagos State | 2020 | Fish | 18,960~45,430 | [39] |

| Canada | Athabasca and Slave Rivers | 2011–2012 | Fish | 4.3~120 | [40] |

| Italy | Adriatic Sea (Mediterranean). | 2011 | Fish | 209.9~227.2 | [41] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hao, Y.; Yang, T.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Miao, X.; Xu, G.; Yang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, H.; Bao, W. Composition, Sources, and Health Risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Commonly Consumed Fish and Crayfish from Caohai Lake, Southwest China. Toxics 2025, 13, 1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121086

Hao Y, Yang T, Wei X, Zhang X, Miao X, Xu G, Yang S, Zhou X, Zhao H, Bao W. Composition, Sources, and Health Risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Commonly Consumed Fish and Crayfish from Caohai Lake, Southwest China. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121086

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Yupei, Tianyao Yang, Xueqin Wei, Xu Zhang, Xiongyi Miao, Gaohai Xu, Sheping Yang, Xiaohua Zhou, Huifang Zhao, and Wei Bao. 2025. "Composition, Sources, and Health Risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Commonly Consumed Fish and Crayfish from Caohai Lake, Southwest China" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121086

APA StyleHao, Y., Yang, T., Wei, X., Zhang, X., Miao, X., Xu, G., Yang, S., Zhou, X., Zhao, H., & Bao, W. (2025). Composition, Sources, and Health Risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Commonly Consumed Fish and Crayfish from Caohai Lake, Southwest China. Toxics, 13(12), 1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121086