Abstract

Background: This study aims to examine the barriers hindering the implementation of sustainable procurement in Indonesian small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and to identify their hierarchical relationships. Methods: A mixed-method approach was adopted, employing Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) to map the causal structure of barriers and Fuzzy MICMAC analysis to classify them according to their influence and dependence. Data were collected through expert evaluations and secondary sources, providing both empirical depth and contextual validity. Results: The results reveal that financial constraints, particularly funding limitations, are the most critical and independent barrier driving the entire system of obstacles. The analysis further shows that systemic linkage barriers, such as minimal government incentives, limited availability of eco-friendly raw materials, and high import dependency, create a self-reinforcing cycle that amplifies cost challenges for SMEs. Dependent barriers, including regulatory inadequacies and weak supplier collaboration, are identified as outcomes of these structural constraints, while autonomous barriers like limited consumer awareness remain less influential but still significant. Conclusions: These findings demonstrate that sustainable procurement barriers are not isolated but interconnected, with financial viability acting as the foundational challenge. The study contributes to the literature by providing a relational perspective on sustainable procurement barriers, offering managerial insights for policy.

1. Introduction

Sustainable procurement has become a vital component of responsible business practices, yet its implementation remains particularly challenging for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These enterprises play a crucial role in economic development and job creation, especially in developing countries, but often lack the financial, technical, and human resources necessary to adopt sustainable practices effectively [1]. Unlike larger firms, SMEs frequently operate with limited access to sustainability-related knowledge and face difficulties integrating environmental and social considerations into procurement decisions. Moreover, they are often excluded from policy frameworks or incentives that promote green procurement, leading to a gap between sustainability goals and actual practices [2]. External pressures from stakeholders or customers may also be minimal, reducing the urgency to adopt such initiatives. As a result, many SMEs remain locked in traditional procurement models that prioritize short-term cost over long-term environmental and social value, thereby limiting their contribution to sustainable development. Given the growing global emphasis on responsible sourcing, identifying and addressing the critical challenges faced by SMEs is essential and urgent for accelerating the transition toward more inclusive and sustainable supply chains [3]. This study focuses specifically on Indonesian food manufacturing SMEs, representing an important emerging economy context where sustainable procurement faces unique institutional and market challenges

Previous research has explored various barriers hindering the adoption of sustainable procurement in SMEs, often highlighting internal limitations such as lack of leadership commitment, insufficient employee engagement, and inadequate supplier collaboration [4]. External challenges, including regulatory uncertainty, market pressure, and limited access to sustainable suppliers, have also been emphasized as key inhibitors [5]. While these studies shed light on both internal and external challenges faced by SMEs, many still present these barriers in isolation, lacking a comprehensive view of how they interrelate within a broader systemic framework. To address this gap, researchers have increasingly turned to structural modeling techniques that can reveal hierarchical relationships among complex variables. Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM), for example, is a proven technique for developing contextual relationships among barriers and understanding their relative driving power and dependence [6]. However, traditional ISM alone may fall short in capturing the ambiguity and subjectivity involved in expert judgment [7]. To overcome this, Peng et al. [7] suggested that the integration of Fuzzy MICMAC analysis enhances the robustness of ISM by quantifying the uncertainty in relationships and providing a more nuanced classification of barriers based on their influence and dependence. This study adopts the combined ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC approach to not only identify but also structurally analyze the interrelationships among critical barriers to sustainable procurement in SMEs, thereby offering deeper insights for practitioners and policymakers to formulate more targeted and effective interventions.

Despite growing interest in sustainable procurement, limited research has systematically examined the structural relationships among its implementation barriers in SMEs, particularly through the integration of advanced decision-support methodologies. Most existing studies either rely on qualitative assessments or use statistical approaches that fail to capture the dynamic interdependencies among barriers [8]. While ISM has been effectively applied in various sustainability contexts to reveal hierarchical structures among influencing factors [9], its application in the domain of SME-focused sustainable procurement remains scarce. Furthermore, few studies combine ISM with fuzzy logic-based methods such as Fuzzy MICMAC to address the inherent uncertainty and subjectivity of expert-based evaluations, especially within the SME sector, where formal data is often limited and experiential knowledge is critical [10]. This lack of methodological integration limits the ability to develop robust, actionable strategies tailored to SMEs’ unique characteristics. Additionally, most procurement-related studies tend to generalize findings without distinguishing between large enterprises and SMEs, thereby overlooking the distinct structural and operational constraints faced by the latter [11]. In response to these gaps, this study aims to identify and structurally analyze the key barriers to implementing sustainable procurement in SMEs by integrating Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) with Fuzzy MICMAC analysis. Through this approach, the study seeks to provide a clearer understanding of the influence–dependence relationships among barriers, offering strategic insights for more effective and context-specific interventions in the SME sustainability landscape.

The rest of this paper is structured into four sections to guide the reader through the research process and findings. The next section presents a comprehensive literature review on sustainable procurement in SMEs and elaborates on previous studies related to barrier identification and structural analysis methods. This is followed by the methodology section, which details the integration of Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) and Fuzzy MICMAC used to analyze the interrelationships among the identified barriers. Section 4 discusses the findings, highlighting the hierarchical structure and influence–dependence classification of the barriers, along with implications for SMEs and policymakers. Finally, the paper concludes with key insights and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Procurement in SMEs

Sustainable procurement refers to the acquisition of goods and services in a way that considers economic value and environmental protection, and social responsibility across the supply chain [12]. It embodies the principles of sustainability by encouraging organizations to minimize negative ecological impacts, promote ethical labor practices, and stimulate innovation through green technologies. According to Islam et al. [13], sustainable procurement serves as a powerful lever for influencing market demand toward more sustainable products and practices. For businesses, it offers long-term benefits such as improved risk management, enhanced corporate reputation, and greater supply chain resilience [14]. As global sustainability concerns continue to escalate, there is increasing pressure on organizations, regardless of size, to align procurement practices with sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 12 on responsible consumption and production. Sustainable procurement thus plays a central role in promoting sustainable development, within large corporations and across smaller firms that form the backbone of many economies [13].

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which constitute over 90% of businesses worldwide and significantly contribute to employment and GDP, are essential actors in the sustainable procurement landscape [15]. However, SMEs face distinctive barriers when attempting to implement sustainable procurement compared to larger enterprises. These include limited financial resources, a lack of internal sustainability expertise, minimal access to green suppliers, and weaker bargaining power within supply chains [16]. Moreover, sustainable procurement practices often require long-term planning and investment, which can be challenging for SMEs operating with short-term survival goals [2]. Unlike large firms that may have dedicated sustainability teams or departments, decision-making in SMEs is typically centralized, with sustainability considerations often taking a backseat to cost efficiency and operational demands [17]. Additionally, regulatory and market-driven sustainability incentives are often designed with larger organizations in mind, thereby excluding SMEs from accessing support schemes that could facilitate their transition [18]. These structural and institutional challenges underscore the need for targeted strategies that account for SMEs’ specific capacities and constraints, ensuring that they are not left behind in the global shift toward more sustainable procurement practices.

2.2. Key Barriers to Sustainable Procurement Implementation

The implementation of sustainable procurement in SMEs is hindered by a variety of internal and external barriers, which often interact in complex ways to limit progress. Internally, one of the most frequently cited barriers is financial constraint; SMEs often operate on limited budgets and face challenges in allocating funds toward environmentally friendly materials, technologies, or supplier certification [14]. Unlike large firms, SMEs may lack the economies of scale needed to justify investments in sustainable alternatives. Additionally, many SMEs suffer from a lack of expertise and awareness regarding sustainability issues. This includes a limited understanding of life-cycle impacts, green standards, and sustainable supplier evaluation [19]. Managerial attitudes also play a role; SME leaders may perceive sustainable procurement as irrelevant to their business goals or too complex to implement [20]. Internally, the absence of formalized procurement systems and sustainability frameworks further exacerbates the problem, making it difficult to institutionalize or monitor progress [21].

Externally, SMEs face systemic and structural barriers that reinforce internal limitations. Regulatory ambiguity, inconsistent enforcement, and the lack of tailored policies often result in minimal compliance motivation or guidance for SMEs [22]. While national and international sustainability regulations exist, they are frequently designed with larger organizations in mind, overlooking the capabilities and needs of smaller firms. Moreover, SMEs typically have limited power in the supply chain and are often dependent on larger buyers or suppliers, which restricts their ability to influence sustainable practices upstream or downstream [23]. Another external barrier is the lack of market incentives and customer demand for sustainable products, particularly in regions where environmental awareness is still emerging [24]. Based on thematic classifications in the literature, these barriers are often grouped into five major categories: financial and resource-based, organizational and cultural, informational and technical, regulatory and institutional, and market-related [21]. Empirical studies in various developing countries, including Indonesia and India, have confirmed the persistence of these challenges, indicating that without a systemic approach to identifying and addressing these barriers, SMEs will continue to face significant obstacles in adopting sustainable procurement practices [25].

2.3. Existing Approaches for Barrier Analysis

Barrier analysis in sustainable procurement research has been approached using a variety of qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative techniques such as interviews, case studies, and focus group discussions offer deep, context-specific insights by capturing the perspectives and experiences of key stakeholders [26]. These methods are particularly valuable during the early stages of investigation, where in-depth understanding is prioritized over generalizability. In contrast, quantitative approaches, including surveys, regression analysis, and both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, are widely used to validate hypothesized relationships among barriers and identify statistically significant patterns [27]. These methods are often supported by statistical tools like SPSS or structural equation modeling (SEM), allowing researchers to analyze large datasets and explore direct and indirect relationships among variables. While each of these methods contributes meaningfully to understanding sustainable procurement challenges, they often fall short in fully capturing the complex interrelationships and feedback mechanisms that exist among multiple, interacting barriers within organizational systems and supply chains.

Existing qualitative and quantitative methods have played important roles in analyzing barriers to sustainable procurement, but they often fall short when applied to the complex realities faced by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Traditional approaches such as surveys, regression analysis, and exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis typically treat barriers as isolated or linearly correlated variables [28]. While these methods are effective for identifying statistical relationships or grouping similar challenges, they rarely uncover the deeper, systemic interdependencies among barriers. This is a critical limitation in the context of sustainable procurement within SMEs, where barriers like limited financial capacity, lack of environmental awareness, inadequate supply chain integration, and weak policy incentives are often interrelated and mutually reinforcing. For example, a lack of government support may exacerbate financial constraints, which in turn hinders SMEs’ ability to invest in sustainability training or green technologies [29].

Given these dynamics, conventional tools cannot fully capture the nonlinear, hierarchical, and feedback-driven nature of such barriers. This has led to growing interest in system-based modeling approaches that provide deeper structural insights. Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) allows researchers to map multilevel relationships, distinguishing foundational driver barriers from outcome-based dependent ones. The addition of fuzzy logic through Fuzzy MICMAC further strengthens the analysis by incorporating uncertainty and imprecision in expert judgments, common when working with diverse SME actors who operate in fragmented and resource-constrained environments [30]. Therefore, in the case of sustainable procurement in SMEs, especially in emerging economies like Indonesia, these integrated techniques are essential. They not only provide a clearer understanding of the structural nature of barriers but also offer actionable insights for prioritizing policy and managerial interventions where resources are limited and interdependencies are high.

2.4. Interpretive Structural Modeling and Fuzzy MICMAC in Sustainability Research

Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) is a well-established decision-support methodology used to identify and analyze relationships among complex variables, particularly in scenarios involving multiple independent barriers or drivers. Introduced by Warfield [31], ISM facilitates the development of a hierarchical structure by incorporating expert knowledge to determine contextual relationships among factors. Through a step-by-step process that includes identifying variables, establishing pairwise relationships, and constructing a structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM), ISM enables researchers to visualize which elements serve as foundational drivers and which are dependent outcomes [32]. In the context of sustainability and supply chain research, ISM has been effectively employed to examine barriers to green practices [32], drivers of circular economy adoption [33], and risk factors in sustainable logistics [34]. Its strength lies in converting qualitative expert opinions into a structured model that reveals the underlying logic of complex systems, offering decision-makers clarity in strategy formulation.

However, one limitation of ISM is its binary treatment of relationships (i.e., the presence or absence of influence), which may oversimplify the nuanced and subjective nature of expert judgments. To overcome this, researchers increasingly integrate ISM with Fuzzy MICMAC (Matrix Impact Cross-Reference Multiplication Applied to a Classification), which incorporates fuzzy logic to quantify the degree of influence among variables rather than relying on rigid yes/no responses [7]. Fuzzy MICMAC enhances ISM by capturing the uncertainty, vagueness, and variability inherent in expert assessments, making the analysis more robust and realistic, especially in socio-technical domains like sustainability. This integrated approach has been successfully applied in a range of sustainability-focused studies, including the identification of barriers to waste management [10], evaluation of sustainable supplier selection criteria [30], and prioritization of challenges in circular economy adoption in emerging markets [35]. By classifying variables based on their driving power and dependence, Fuzzy MICMAC enables a more nuanced understanding of how certain barriers act as root causes while others are consequences. As such, the integration of ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC offers a comprehensive and flexible framework for analyzing complex problems in sustainability, particularly in the SME context, where expert knowledge plays a pivotal role in the absence of extensive quantitative data [36].

2.5. Research Gap and Methodological Integration in This Study

While the importance of sustainable procurement has been widely acknowledged, particularly in the context of large enterprises, there remains a significant gap in the literature when it comes to its implementation within small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Existing studies have often focused on identifying general sustainability barriers in SMEs [25,37] or addressing specific environmental challenges in broader supply chains [16], yet few have examined the complex structural interrelationships among barriers that are unique to SME procurement contexts. Furthermore, most previous research relies on either qualitative insights or quantitative statistical models that tend to treat barriers as independent or loosely correlated variables [27]. As a result, the systemic nature of these challenges, where one barrier may reinforce or trigger another, remains underexplored. Although several studies have applied ISM or Fuzzy MICMAC in sustainability and operations research [7,30], their application to the specific case of sustainable procurement in SMEs is both limited and fragmented. In particular, the integrated use of ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC to examine the hierarchical structure and influence-dependence relationships among barriers in this domain remains largely absent.

This study seeks to address that methodological and contextual gap by integrating Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) with Fuzzy MICMAC analysis to explore the key barriers to sustainable procurement in SMEs. Unlike previous approaches that either list barriers or analyze them in isolation, the integrated ISM–Fuzzy MICMAC method allows for a deeper understanding of how these barriers interact, cluster, and influence one another. This is especially relevant for SMEs, which often operate in resource-constrained environments where decision-making is influenced by multiple, interrelated constraints such as budget limitations, supplier availability, and managerial awareness [38]. By mapping these relationships in a structured and data-informed way, this study provides a more comprehensive view of the sustainable procurement landscape in SMEs and offers practical insights for decision-makers aiming to prioritize interventions. The methodological integration also enhances reliability by addressing the uncertainty and subjectivity inherent in expert judgments, an important feature in SME research where formal data may be lacking. Therefore, this study not only contributes to the academic literature by filling a methodological void but also serves as a decision-support tool for practitioners and policymakers striving to promote sustainability in smaller enterprises.

Table 1 highlights key gaps in existing research on sustainable procurement in SMEs, particularly within the food sector. Prior studies have largely focused on general sustainability issues [25] or treated barriers as isolated factors using qualitative or statistical methods [27], lacking a systems perspective. While some research applied ISM or Fuzzy MICMAC separately [38], their integration remains rare, especially in SME procurement contexts. Even structural modeling efforts in Indonesian manufacturing [34] did not fully integrate fuzzy logic to address judgment uncertainty. Therefore, this study addresses a critical gap by applying the integrated ISM–Fuzzy MICMAC approach to explore interrelated barriers in green procurement specific to the food SME sector.

Table 1.

Research gaps and justification for ISM–Fuzzy MICMAC integration.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Approach

This study adopts an exploratory research design to investigate and structurally model the key barriers to sustainable procurement in SMEs. Given the complex and interdependent nature of these barriers, a mixed qualitative-quantitative approach is appropriate to capture both the depth of expert insight and the structure of relationships among variables [39]. The integration of Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) and Fuzzy MICMAC provides a robust decision-support framework capable of uncovering hidden hierarchies, causal relationships, and systemic interactions among multiple [38]. This methodological choice aligns with the objective of this study, to go beyond identifying individual barriers and instead map their interdependencies in the context of SME sustainable procurement.

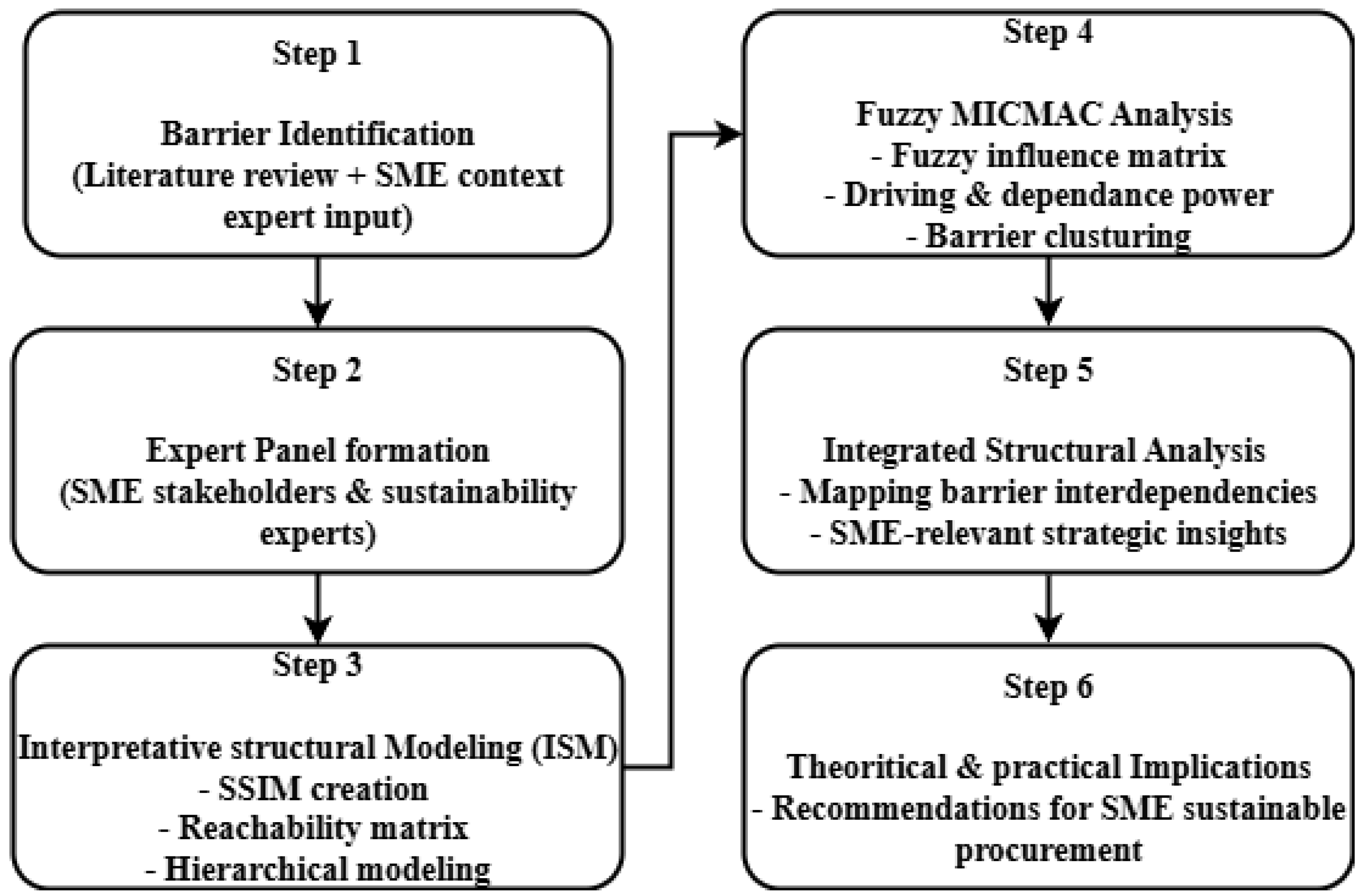

Figure 1 shows that the research process begins with Step 1: Barrier Identification, which involves a comprehensive review of existing literature combined with contextual insights gathered from sustainability and procurement experts familiar with SMEs. This hybrid approach ensures that the identified barriers reflect both theoretical foundations and practical relevance to SMEs [9]. Sustainable procurement in SMEs often involves unique challenges such as limited budgets, knowledge gaps, and weak supply chain power, barriers that are often underrepresented in generic frameworks [40]. Thus, expert consultation helps refine and validate a context-specific list of barriers. In Step 2: Expert Panel Formation, qualified participants are selected based on their professional experience in SME operations, procurement, or sustainability. Experts typically include SME managers, policymakers, and academic researchers, whose insights are crucial to evaluating the interrelationships among barriers. This panel provides the input required for the structural modelling in the subsequent stages.

Figure 1.

Research design for sustainable procurement in SMEs: Integration of ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC.

In Step 3: Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM), experts assess pairwise relationships between the identified barriers, which are then used to construct a Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM). The matrix is transformed into a reachability matrix, and transitivity rules are applied to reveal the hierarchical structure of barriers [41]. This step allows researchers to determine which barriers are foundational (i.e., driver barriers) and which are consequences (i.e., dependent barriers), helping SMEs prioritize interventions. Step 4: Fuzzy MICMAC Analysis is integrated to overcome the binary limitations of ISM by incorporating fuzzy logic, which allows experts to express varying degrees of influence between barriers [38]. This enhances the robustness of the analysis and accounts for uncertainty and subjectivity in human judgment. Step 5: Integrated Structural Analysis combines the outputs of ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC, enabling a systemic understanding of how sustainable procurement barriers interact. This integration results in a detailed barrier map that highlights key leverage points within the SME context. Finally, Step 6: Policy and Practice Implications interprets the analytical results to formulate actionable strategies. These may include capacity-building programs, policy incentives, or supply chain collaborations tailored to the constraints and opportunities faced by SMEs in adopting sustainable procurement practices [42]. This structured and integrated methodology ensures both academic rigor and practical relevance.

3.2. Identification of Barriers

The identification of barriers is a critical initial step to ensure the relevance and completeness of the analysis in sustainable procurement practices among Indonesian SMEs. This study began with a rigorous literature review of peer-reviewed journals, policy reports, and sustainability assessment frameworks to extract frequently cited and theoretically grounded barriers [43]. Particular attention was given to research conducted in developing economies and Asian contexts where SME-specific sustainability challenges are prevalent. This stage allowed the research team to construct a preliminary list of barriers, including financial limitations, lack of green awareness, poor supplier collaboration, and inadequate regulatory support. To contextualize these findings for the Indonesian SME environment, the study conducted informal interviews with six practitioners involved in SME procurement and sustainability management. These interactions helped identify context-specific barriers, such as inconsistent enforcement of environmental regulations, weak buyer pressure, and a lack of localized green procurement policies. The triangulation of secondary sources with practitioner insights ensures both academic validity and contextual relevance [44]. Ultimately, a refined list of twelve key barriers was finalized for use in the ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC phases. These barriers were carefully validated to reflect the operational realities of SMEs in Indonesia, where informality, resource constraints, and limited market incentives often hinder sustainable transitions.

3.3. Expert Selection and Data Collection

The credibility of the ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC methodologies is contingent upon the quality and relevance of the expert panel. A panel of eight experts was deemed appropriate for this study, as the focus of ISM is on leveraging deep, expert knowledge rather than achieving statistical generalization through a large sample size. This approach is consistent with established methodological precedents in ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC research, where panels typically range from 5 to 15 members to maintain manageability while ensuring diverse and informed perspectives [7,38]. The expert selection followed a purposive sampling strategy to ensure the panel represented the key stakeholder groups involved in or affecting sustainable procurement in Indonesian SMEs. The selection criteria were rigorously defined: each expert was required to have (a) a minimum of five years of hands-on professional experience directly relevant to SME operations, procurement logistics, or sustainability management; and (b) a demonstrated understanding of the challenges within the Indonesian context, particularly in the food manufacturing sector. Experts were identified and recruited through professional networks, industry associations, and academic institutions to cover a balanced mix of perspectives from policy, practice, and research.

The final panel composition, detailed in Table 2, was designed to integrally capture the viewpoints of policymakers (who shape the regulatory environment), implementers (SMEs who face operational realities), researchers (who provide theoretical and analytical insight), and sustainability consultants (who offer cross-sectoral advisory experience). This diversity was crucial for capturing a holistic and validated view of the interrelationships between barriers.

Table 2.

Profile of the Expert Panel.

Given the expert-driven nature of ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC methodologies, the credibility of the output heavily depends on the competence and diversity of the expert panel. The expert selection followed a purposive sampling strategy to deliberately constitute a panel representing the key stakeholder ecosystem of sustainable procurement in Indonesian SMEs. The selection criteria required participants to possess a minimum of five years of experience in SME procurement, environmental management, or sustainability-related policymaking. To ensure a balanced perspective, a total of eight experts were selected from the following sectors, providing a cross-section of relevant stakeholders: three from academia (specifically, faculty from business and industrial engineering departments of state and private universities in Indonesia), two from government regulatory bodies (relevant national and local agencies overseeing trade and industry), two owners/managers from private sector food manufacturing SMEs in the Indonesian province cluster, and one sustainability consultant from a local firm. This composition was designed to integrally capture the perspectives of policymakers, implementers (SMEs), researchers, and advisors. Data collection took place in two rounds. The first round involved structured interviews in which experts provided input on the contextual relationships among the twelve identified barriers. In the second round, experts completed a follow-up online questionnaire to validate fuzzy influence scores and provide clarification where inconsistencies were observed. Ethical research procedures were strictly followed, including informed consent, anonymity, and transparency of purpose [45]. This hybrid approach enhanced the richness and reliability of the expert data, which formed the basis for ISM modelling and fuzzy classification.

3.4. Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) Procedure

The ISM methodology was employed to model the complex interrelationships among the twelve barriers identified in the prior stage. ISM provides a structured framework to convert expert judgments into a multilevel structural model [46]. The process began with the development of a Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM), in which experts were asked to define the direction and nature of the contextual influence between each pair of barriers using standard symbolic notation (V, A, X, O). These symbolic relationships were then converted into binary values (0 or 1) to form the initial reachability matrix. Transitivity rules were applied to derive the final reachability matrix, capturing both direct and indirect influences among variables [47]. The reachability matrix underwent level partitioning to categorize barriers into hierarchical levels, indicating whether a barrier was foundational or dependent. Barriers positioned at higher levels were typically outcomes of lower-level driver barriers. This step-by-step modelling process culminated in the creation of a directed graph (digraph) that visually represents the structural hierarchy and dependencies among the barriers. For SMEs in Indonesia, where decision-making is constrained by limited resources and regulatory ambiguity, this visualization helps highlight leverage points, barriers that, if addressed, could alleviate multiple dependent challenges. The ISM results thus serve as an essential foundation for subsequent Fuzzy MICMAC analysis.

3.5. Fuzzy MICMAC Analysis

Following the development of the ISM model, Fuzzy MICMAC analysis was conducted to quantify the strength of influence among the barriers and classify them into strategic categories. The Fuzzy MICMAC approach enhances traditional MICMAC by incorporating fuzzy logic to handle the uncertainty and ambiguity in expert judgments [10]. Experts assigned influence values on a five-point fuzzy scale ranging from 0 (no influence) to 1 (very high influence). The calibration of fuzzy sets required translating linguistic expert judgments into numerical values. A non-linear fuzzy scale was adopted for this purpose: 0.0 (no influence), 0.1 (very low influence), 0.3 (low influence), 0.5 (moderate influence), 0.7 (high influence), 0.9 (very high influence), and 1.0 (absolute influence). This specific scale was chosen as it is well-established in fuzzy-based supply chain and sustainability research for providing experts with higher sensitivity to differentiate between varying levels of influence, which is critical for capturing nuanced judgments in complex, expert-driven systems [10]. The calibration procedure was direct: during the second round of data collection, experts were provided with this scale and its definitions and were asked to assign the corresponding numerical value for the influence between each pair of barriers directly into the Fuzzy Direct Influence Matrix (FDIM). This direct assignment method was selected for its transparency and simplicity, reducing potential cognitive burden on the experts while ensuring a consistent translation of qualitative assessments into fuzzy membership scores [7].

The adoption of this specific non-linear fuzzy scale is grounded in established methodological precedents within the domain of fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making [30]. The rationale for selecting a non-linear, exponential-like scale over a linear alternative is twofold. First, it offers enhanced discriminatory power in the lower and mid-range values, allowing experts to make finer distinctions between ‘very low,’ ‘low,’ and ‘moderate’ levels of influence, a region where subjective judgment often exhibits the greatest uncertainty. Second, it more accurately reflects the psychological perception of experts, for whom the difference between ‘high’ and ‘very high’ influence is semantically more significant than the intervals between lower ratings. A linear scale would lack this necessary sensitivity, potentially flattening critical nuances in expert judgment.

These values were then used to build a Fuzzy Direct Influence Matrix (FDIM), which allowed for a more nuanced and realistic modelling of inter-barrier dynamics. Using the FDIM, the study calculated two key metrics for each barrier: driving power (how much influence a barrier exerts on others) and dependence (how much a barrier is influenced by others). Based on these metrics, barriers were grouped into four categories: autonomous, dependent, linkage, and driver. This classification provides actionable insight for policymakers and SME managers. For example, high-driving but low-dependence barriers, typically found in the driver quadrant, are strategic leverage points that should be prioritized [48]. In the Indonesian SME context, this enables targeted interventions to address foundational issues such as a lack of sustainability knowledge or insufficient financial support, which in turn can ease more symptomatic challenges like low supplier engagement or limited green innovation.

3.6. Validation and Reliability Measures

To ensure the methodological rigor and credibility of the ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC findings, several validation measures were implemented. Triangulation was a key strategy, combining three independent data sources: academic literature, expert interviews, and structured judgment matrices. This cross-verification enhances construct validity and reduces the risk of overlooking context-specific barriers [49]. Furthermore, a consistency check was conducted by comparing the ISM digraph with the Fuzzy MICMAC classification to ensure alignment in the identification of driver and dependent variables. Any discrepancies were reviewed in a follow-up session with experts, where clarifications and adjustments were made collaboratively. Reliability was further reinforced through anonymized data collection, clear criteria for expert inclusion, and consistency checks in matrix construction. The use of fuzzy logic also contributes to methodological robustness by accommodating the ambiguity inherent in human judgment [30]. While expert-based models inherently contain subjective elements, this study minimized bias by employing structured protocols, multiple iterations of review, and diversified expert representation. These measures collectively enhance the transparency, trustworthiness, and applicability of the research outcomes for advancing sustainable procurement practices in Indonesian SMEs.

4. Results

4.1. Identification of Key Barriers Through SP Performance Indicators

The identification of barriers to sustainable procurement in Indonesian food SMEs was conducted through a multi-stage, systematic process to ensure comprehensiveness and validity. The process commenced with an extensive literature review of peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings, and reports on sustainable procurement, with a specific focus on SMEs and developing economies. This initial stage generated a comprehensive longlist of 23 potential barriers. To contextualize these findings and ensure their relevance to the Indonesian food manufacturing sector, semi-structured interviews and on-site observations were conducted with a group of SME owners and managers within a traditional industrial cluster. This qualitative phase confirmed the practical relevance of many literature-derived barriers and identified context-specific challenges, such as the critical dependence on imported GMO soybeans.

The consolidated list of barriers was then subjected to a validation and refinement process by our expert panel (described in Section 3.3). Through a structured discussion and ranking exercise, the experts assessed the relevance and prevalence of each barrier. The final selection of 13 key barriers was determined by expert consensus, focusing on those deemed most critical and frequently encountered in the Indonesian SME context. This multi-method approach, triangulating literature, practitioner input, and expert validation, ensures the list is both academically grounded and contextually robust. The final 13 barriers, their operational definitions, and their supporting evidence from both literature and our empirical study are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Key Barriers.

Key barriers were identified by further examining the performance indicators of sustainable procurement (SP) (Table 3), which are categorized into three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental. The initial identification of barriers to implementing sustainable procurement among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) within a traditional food-manufacturing industrial cluster in Indonesia was conducted through in-depth interviews with SME owners, on-site observations of production activities, and an extensive literature review on sustainable procurement practices. From this process, 23 initial barriers were formulated and subsequently validated by experts, consisting of practitioners and academics, resulting in 13 agreed-upon key barriers. These findings were further reinforced using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), which revealed the priority of barriers based on their weighted criteria. The analysis showed that the economic dimension dominates (63.38%), followed by the social (21.05%) and environmental (15.57%) dimensions.

4.2. Construction of the Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM)

The Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM) was developed to identify relationships among the barriers. In this matrix, each pair of barriers was evaluated to determine whether an influence exists, and if so, the direction of influence. Relationships were classified using four symbols: V (one-way influence from element i to j), A (reverse influence from j to i), X (mutual influence between i and j), and O (no relationship). These relationships were established based on expert consensus obtained through structured interviews and questionnaires involving representatives of the local SME association, five SME managers, and two academic experts specializing in sustainable procurement. The SSIM is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM).

Table 4 illustrates the symbolic representation of relationships between barriers. For instance, in row EK1 and column LN13, the symbol X indicates mutual influence. In contrast, EK2–EK4 is denoted by V, meaning EK2 influences EK4 but not vice versa. Similarly, EK1–LN10 shows A, where LN10 influences EK1 but not the reverse, while EK1–LN11 is marked O, indicating no relationship.

4.3. Construction of the Reachability Matrix

The ISM analysis begins by converting the SSIM into an Initial Reachability Matrix (IRM) through binary coding. In this process, V, A, X, and O were converted into binary values according to the defined rules: V = (i, j) = 1 and (j, i) = 0; A = (i, j) = 0 and (j, i) = 1; X = both entries = 1; and O = both entries = 0. The IRM is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Initial Reachability Matrix (IRM).

Table 5.

Initial Reachability Matrix (IRM).

| i/j | EK1 | EK2 | EK3 | EK4 | EK5 | SO6 | SO7 | SO8 | SO9 | LN10 | LN11 | LN12 | LN13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EK1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| EK2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EK3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EK4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EK5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| SO6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| SO7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SO8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| SO9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| LN10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| LN11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| LN12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| LN13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Subsequently, the Final Reachability Matrix (FRM) was obtained (Table 5) after applying the transitivity rule, which ensures logical consistency by updating indirect relationships. For instance, if LN13 → LN10 = 1 and LN10 → EK2 = 1, then LN13 → EK2 must also be updated to 1. Six such transitivity updates were required.

4.4. Level Partitioning

Based on the FRM, level partitioning was performed iteratively using reachability sets (RS), antecedent sets (AS), and their intersections (IS). Variables with RS identical to IS were eliminated at each iteration until the final hierarchical structure was obtained. Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10 present the iterative results, while Table 11 summarizes the final level partitions.

Table 6.

Level Partitions (iteration 1).

Table 6.

Level Partitions (iteration 1).

| Code | RS | AS | IS | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EK1 | 1, 12, 13 | 1, 2, 5, 10, 13 | 1, 13 | |

| EK2 | 1, 2, 4 | 2, 10, 13 | 2 | |

| EK3 | 3 | 3, 10, 13 | 3 | 1 |

| EK4 | 4 | 2, 4, 5, 10, 13 | 4 | 1 |

| EK5 | 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 13 | 5 | 5 | |

| SO6 | 6, 12 | 5, 6 | 6 | |

| SO7 | 7 | 5, 7, 10, 13 | 7 | 1 |

| SO8 | 8, 12 | 8 | 8 | |

| SO9 | 9, 11 | 5, 9, 10, 13 | 9 | |

| LN10 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13 | 10, 13 | 10, 13 | |

| LN11 | 11 | 9, 11 | 11 | 1 |

| LN12 | 12 | 1, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13 | 12 | 1 |

| LN13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13 | 1, 5, 10, 13 | 1, 10, 13 |

In the first stage of constructing level partitions, five variables were eliminated: EK3, EK4, SO7, LN11, and LN12.

Table 7.

Level Partitions (iteration 2).

Table 7.

Level Partitions (iteration 2).

| Code | RS | AS | IS | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EK1 | 1, 13 | 1, 2, 5, 10, 13 | 1, 13 | 2 |

| EK2 | 1, 2 | 2, 10, 13 | 2 | |

| EK5 | 1, 5, 6, 9, 13 | 5 | 5 | |

| SO6 | 6 | 5, 6 | 6 | 2 |

| SO8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| SO9 | 9 | 5, 9, 10, 13 | 9 | 2 |

| LN10 | 1, 2, 9, 10, 13 | 10, 13 | 10, 13 | |

| LN13 | 1, 2, 9, 10, 13 | 1, 5, 10, 13 | 1, 10, 13 |

At the second iteration level of partitions, the variables EK1, SO6, SO8, and SO9 were excluded from the subsequent iteration process.

Table 8.

Level Partitions (iteration 3).

Table 8.

Level Partitions (iteration 3).

| Code | RS | AS | IS | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EK2 | 2 | 2, 10, 13 | 2 | 3 |

| EK5 | 5, 13 | 5 | 5 | |

| LN10 | 2, 10, 13 | 10, 13 | 10, 13 | |

| LN13 | 2, 10, 13 | 5, 10, 13 | 10, 13 |

At the third iteration partition level, the variable EK2 was excluded from the subsequent iteration process.

Table 9.

Level Partitions (iteration 4).

Table 9.

Level Partitions (iteration 4).

| Code | RS | AS | IS | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EK5 | 5, 13 | 5 | 5 | |

| LN10 | 2, 10, 13 | 10, 13 | 10, 13 | 4 |

| LN13 | 2, 10, 13 | 5, 10, 13 | 10, 13 | 4 |

At the fourth iteration level of the partition process, variables LN10 and LN13 were excluded from subsequent iterations.

Table 10.

Level Partitions (iteration 5).

Table 10.

Level Partitions (iteration 5).

| Code | RS | AS | IS | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EK5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

The level partitioning process reached its final stage in the fifth iteration, eliminating variable EK5 as the last element. The overall results of all iterations are presented in Table 11, which represents the Final Level Partitions that clearly map the hierarchical relationships among all analyzed variables.

Table 11.

Final Level Partitions.

Table 11.

Final Level Partitions.

| Code | Dependence | Level |

|---|---|---|

| EK3 | Highly Dependent | 1 |

| EK4 |  | 1 |

| SO7 | 1 | |

| LN11 | 1 | |

| LN12 | 1 | |

| EK1 | 2 | |

| SO6 | 2 | |

| SO8 | 2 | |

| SO9 | 2 | |

| EK2 | 3 | |

| LN10 | 4 | |

| LN13 | 4 | |

| EK5 | Highly Independent | 5 |

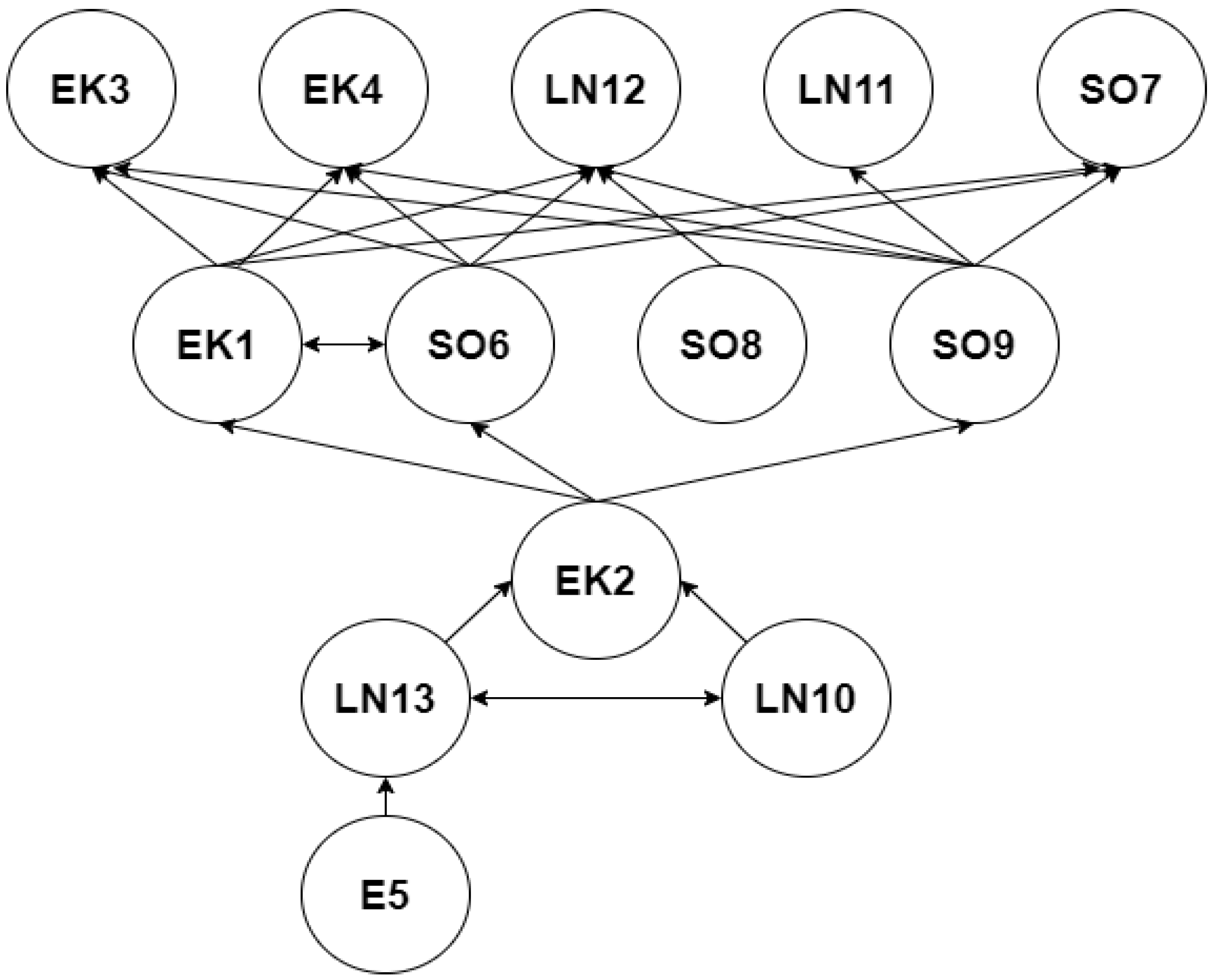

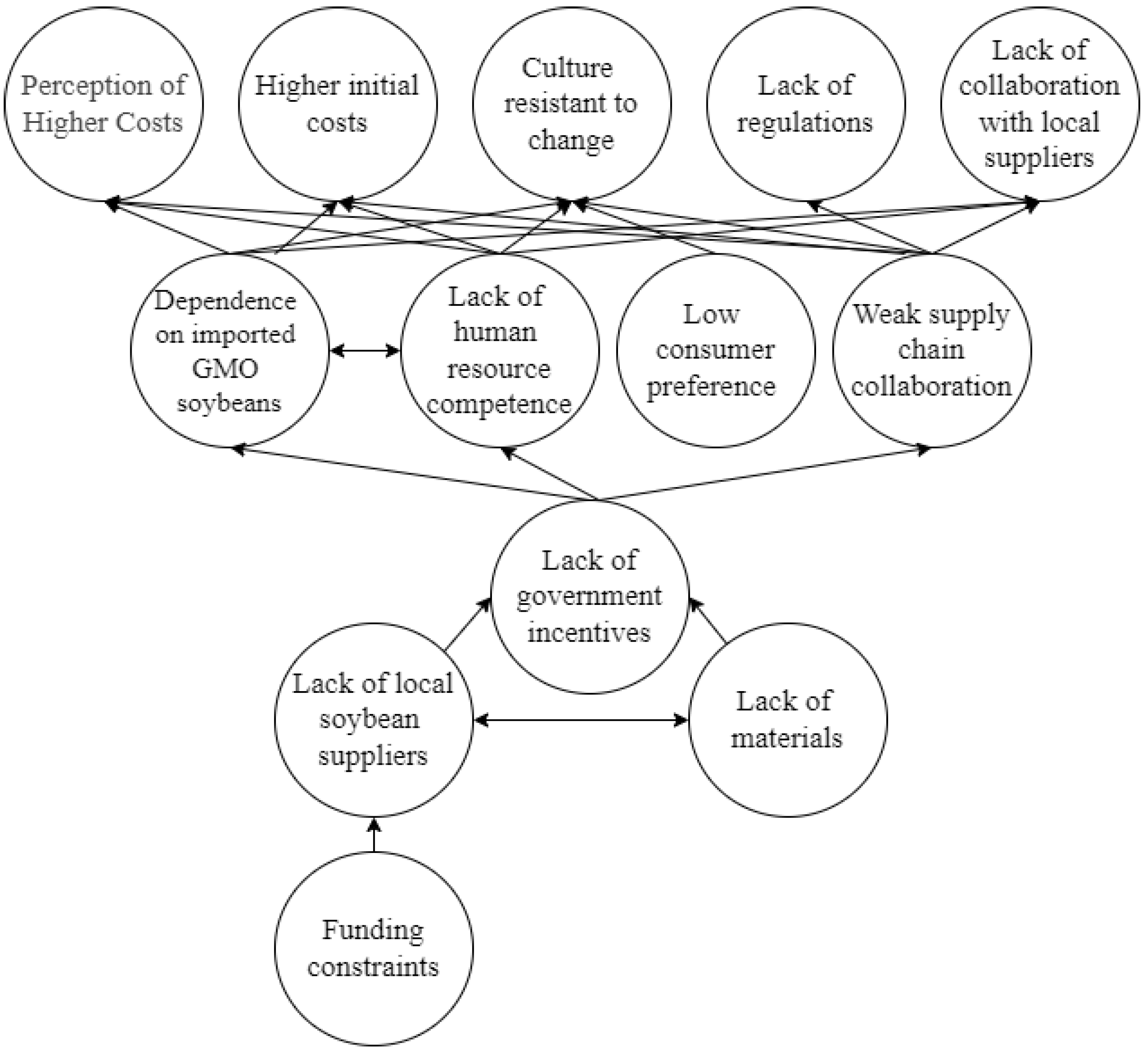

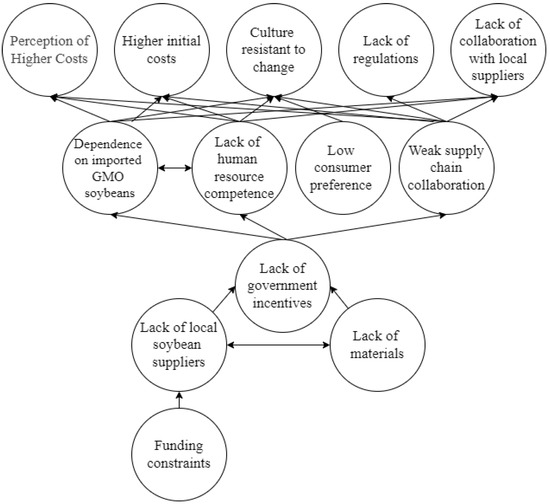

The final hierarchy categorizes barriers into five levels, ranging from Level I (highly dependent. The level partitioning process yielded a definitive seven-level hierarchical structure, visually represented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. This hierarchy is pivotal for understanding the relational dynamics between barriers. At the foundational Level I, E5 (Funding Limitations) was identified as the sole root or independent barrier. This positioning signifies its critical role as a fundamental driver of the system, exerting significant influence on other barriers while being largely unaffected by them. Conversely, occupying the highest level (Level VII) are the most dependent barriers: E3 (Unfamiliarity with Green Logistics), E4 (Resistance to Change), S7 (Lack of Strategic Partnerships), L11 (Inadequate Infrastructure), and L12 (Unsupportive Government Policies). These represent the ultimate outcomes or symptoms within the model, being highly influenced by barriers at lower levels but generating minimal influence themselves. The intermediate levels (II through VI) contain linkage barriers that act as critical transmission channels, propagating the effects of the root cause upward toward the dependent outcomes. This clear structural mapping underscores that effective intervention strategies must prioritize the root barrier, E5, to create meaningful change throughout the entire system

Figure 2.

Structural representation of barriers through the ISM-based directed graph.

Figure 3.

ISM Model.

4.5. Development of the ISM Model

The ISM structural model was developed from the FRM and represented as a directed graph (digraph). Each barrier is depicted as a node, with arrows representing direct influences. To simplify the model, transitive links were removed.

Figure 2 presents a directed graph that reveals a complex system where barriers in one dimension actively cause barriers in another. The structure identifies key “driver” barriers, which align perfectly with the “Highly Dependent” Level 1 codes in the accompanying table. Specifically, Perception of Higher Costs and Higher initial costs (EK3 & EK4), both Level 1 barriers, form a potent economic cluster that reinforces each other and suppresses social demand (Low consumer preference). Similarly, the other Level 1 barriers, Lack of collaboration with local suppliers (SO7), Culture resistant to change (LN12), and Lack of regulations (LN11), act as profound root causes within the graph. This hierarchy of influence is visually confirmed in Figure 3, which lists these same issues as the primary, foundational barriers at the top of its structure. Conversely, the graph highlights critical “outcome” barriers, with Lack of local soybean suppliers (LN13) emerging as a central bottleneck. According to the table, LN13 is a Level 4 barrier (Highly Independent), confirming its role as a resultant problem. It is not a standalone issue but the culmination of multiple influences from more dependent barriers, such as Dependence on imported GMO soybeans (EK1, Level 2) and the Level 1 barrier, Weak collaboration with local suppliers (SO7).

This interconnected model, where Level 1 driver barriers cause Level 4 outcome barriers, aligns with and refines prior research. The potency of the Level 1 economic perceptions as primary drivers confirms findings that financial constraints and cost premiums are the most significant and foundational hurdles [51]. Furthermore, the position of the other Level 1 barriers from Figure 3, particularly Culture resistant to change, as a key influencer of Lack of human resource competence, substantiates claims that organizational culture is a more foundational issue than a lack of skills [52]. The convergence of multiple influences on the Level 4 barrier Lack of local soybean suppliers, provides a specific case study of resource dependence theory. It demonstrates that this critical bottleneck, also positioned as a culminating barrier in Figure 3, is the ultimate effect of a network of preceding, more dependent economic and social failures [53]. This synthesis shows that while Figure 2 illustrates the causal “how” of influence, the dependence level table and the hierarchy in Figure 3 categorize the “why,” collectively identifying which barriers are the fundamental levers for systemic intervention.

4.6. Construction of the Fuzzy Direct Reachability Matrix (FDRM)

The FDRM was constructed from the Binary Direct Relationship Matrix (BDRM), derived from the IRM but excluding transitivity rules. Experts then assigned influence levels using fuzzy scales: 0.0 = no influence, 0.1 = very low, 0.3 = low, 0.5 = moderate, 0.7 = high, 0.9 = very high, 1.0 = absolute.

Table 12 presents the Fuzzy Direct Reachability Matrix (FDRM), which refines the Binary Direct Relationship Matrix (BDRM) by incorporating expert judgments on the degree of influence between barriers using fuzzy scales. The results highlight that “funding limitations” (EK5) exert strong influence on several barriers, including EK1 (import dependency, 0.9), SO6 (limited human resources, 0.7), SO9 (weak supply chain collaboration, 0.5), LN12 (cultural resistance, 0.7), and LN13 (limited local non-GMO supply, 0.9), underscoring its role as a primary driver. Similarly, LN10 (availability of eco-friendly raw materials) also shows strong bidirectional relationships, particularly with EK1 (0.9), EK2 (0.7), and LN13 (0.9), suggesting that raw material availability is both a consequence and a reinforcing factor of systemic barriers. In contrast, some variables, such as EK3 (perception of high costs), EK4 (large initial costs), and LN11 (inadequate regulations), demonstrate weak or no direct influence, placing them in more dependent roles. These findings support earlier studies emphasizing that financial constraints and resource scarcity act as dominant structural barriers in sustainable procurement systems [54].

Table 12.

Fuzzy Direct Relationship Matrix.

4.7. Fuzzy MICMAC-Stabilized Matrix

The Fuzzy MICMAC-Stabilized Matrix is obtained through an iterative process by repeatedly multiplying the Fuzzy Direct Relationship Matrix (FDRM) using the fuzzy matrix multiplication rule (max-min composition). The purpose of this iteration is to identify and strengthen the indirect relationships between elements that may be hidden within the direct relations [10]. In each iteration, the values in the matrix are updated by taking the maximum value of the minimum between corresponding rows and columns, reflecting the deeper level of indirect influence between elements. This process continues until the values in the matrix no longer undergo significant changes, or in other words, the structure of the relationships between elements has reached a stable condition. The final resulting matrix from this process is called the Fuzzy MICMAC-Stabilized Matrix (see Table 13) and is used to determine the position of each element based on driving power (the power to influence other elements) and dependence (the level of dependence on other elements) [55]. This process uses the following formula:

where,

Table 13.

Final Fuzzy MICMAC-Stabilized Matrix.

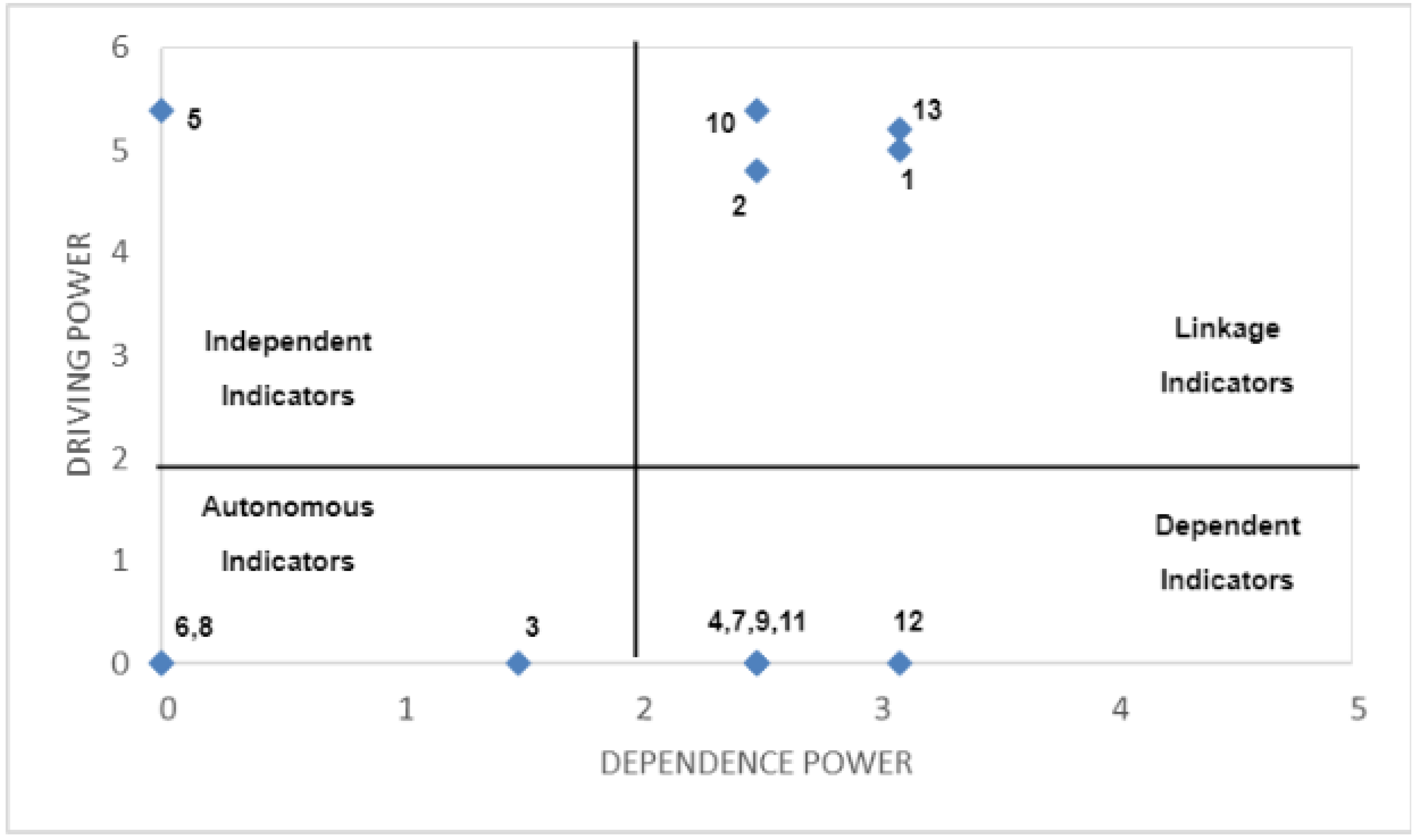

Driving power was obtained from the horizontal summation of transitivity values, while dependence was calculated vertically. These results formed the Driving–Dependence Diagram (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Driving–Dependence Diagram.

4.8. Construction of the Driving Power–Dependence Diagram

Based on the driving power and dependence power values calculated in the Final Fuzzy MICMAC-Stabilized Matrix, the barriers can be classified into four main clusters: Autonomous Indicators (Cluster I), Dependent Indicators (Cluster II), Linkage Indicators (Cluster III), and Independent Indicators (Cluster IV).

The Driving–Dependence Diagram categorizes barriers into four clusters based on their driving power and dependence. The interpretation of each cluster is as follows:

Cluster I (Autonomous).

This cluster comprises barriers EK3 (perception of high costs), SO6 (limited human resource competence), and SO8 (low consumer preference), all of which exhibit low driving power and dependence, indicating minimal direct influence on the broader sustainable procurement system. Although these barriers do not play a dominant structural role, they represent underlying behavioral and perceptual challenges that can indirectly slow sustainability adoption among SMEs. The perception of high costs often serves as a psychological and cognitive barrier, deterring small business owners from investing in green initiatives despite potential long-term benefits [29]. Similarly, the limited competence of human resources constrains firms’ ability to implement and manage sustainability programs effectively, aligning with findings by Purgał-Popiela [56], who emphasized that skill and knowledge gaps impede operational sustainability in smaller enterprises. Low consumer preference for sustainable products further reinforces this stagnation, as weak market demand discourages firms from transitioning toward eco-friendly procurement practices [57]. Addressing these autonomous barriers requires strategic interventions focused on awareness campaigns, targeted training programs, and consumer education initiatives to foster a supportive cultural and market environment that can complement broader systemic reforms.

Cluster II (Dependent).

This cluster comprises EK4 (large initial costs), SO7 (weak local supplier collaboration), SO9 (weak supply chain collaboration), LN11 (inadequate regulations), and LN12 (cultural resistance). These barriers are primarily dependent in nature, meaning they arise as consequences of other systemic challenges rather than serving as root causes within the sustainable procurement framework. High initial costs are often linked to SMEs’ limited access to external financing and credit facilities, which constrain their ability to invest in sustainable technologies and raw materials [58]. Similarly, weak collaboration with local suppliers and broader supply chain partners reflects the fragmented and informal structure of SME networks in developing contexts, emphasizing the need to strengthen trust-based relationships and cooperative procurement mechanisms [59]. Furthermore, inadequate regulatory support and cultural resistance act as institutional and behavioral barriers that reinforce this dependency pattern. Studies by Gibral et al. [60] emphasize that without consistent government regulations, awareness programs, and social incentives, firms are less motivated to adopt sustainable practices. Therefore, overcoming these dependent barriers requires a combination of financial facilitation, network-building initiatives, and policy reforms that address both structural and cultural dimensions of sustainable procurement.

Cluster III (Linkage).

This cluster comprises barriers with both high driving power and high dependence, making them unstable and highly interconnected within the sustainable procurement system. It includes EK1 (dependence on imported GMO soybeans, representing 60% of total imports and priced 37% cheaper), EK2 (minimal government incentives), LN10 (availability of eco-friendly raw materials covering less than 30% of domestic demand), and LN13 (limited local non-GMO soybean suppliers). These barriers create a self-reinforcing feedback loop in which minor disruptions can trigger cascading effects throughout the supply chain. For example, the inability of SMEs to transition toward sustainable raw materials is driven not only by the scarcity of eco-friendly inputs but also by the absence of adequate policy and financial incentives to stimulate local production. According to Meliany et al. [61], domestic soybean production reached only 851,286 tons, fulfilling just 29% of national demand compared to an annual import dependency of 2.08 million tons, highlighting the structural imbalance in supply. Such findings align with Göçer et al. [62], who emphasized that sustainability barriers often interact dynamically, amplifying systemic risks rather than acting independently. Similarly, Abbas et al. [63] noted that linkage barriers are inherently volatile due to their dual influence and dependence, requiring integrated interventions across policy, supply chain, and market levels. Therefore, addressing these linkage barriers demands a coordinated multi-stakeholder strategy that simultaneously enhances local raw material availability, introduces targeted government incentives, and strengthens supplier collaboration to stabilize the sustainable procurement ecosystem in SMEs.

Cluster IV (Independent/Driving).

This cluster contains a single barrier, EK5 (funding limitations), which emerges as the root cause with the strongest driving power. The financial gap between sustainable and conventional procurement options is substantial: locally sourced or eco-friendly materials are often significantly more expensive than imported or non-sustainable alternatives, while environmentally responsible packaging options can cost several times more than conventional plastic. Such economic disparities create a heavy burden on SMEs that typically operate with limited capital and cash flow [64]. Without accessible financing mechanisms, such as green credit schemes, fiscal incentives, or collaborative investment programs, SMEs struggle to absorb additional costs or achieve economies of scale necessary for sustainable transformation [65]. Consequently, funding limitations remain the most critical structural barrier to the widespread adoption of sustainable procurement practices, reinforcing previous findings that financial constraints often overshadow environmental and social priorities in SME operations [23].

4.9. Summary of Fuzzy MICMAC Clusters

The Fuzzy MICMAC analysis provides a critical classification of the barriers, moving beyond a simple list to reveal their strategic roles within the system based on driving and dependence power. The 13 barriers are categorized into four distinct clusters, as will be visualized in the subsequent driving-dependence diagram (Figure 4). Cluster I (Autonomous Barriers: EK3, SO6, SO8) encompasses barriers with weak driving and dependence power, indicating their relative isolation from the core system dynamics. These barriers, which include the perception of high costs, limited human resource competence, and low consumer preference, represent persistent background challenges. However, their autonomous nature does not render them insignificant; as noted by Purwandani & Michaud [29], such perceptual and awareness gaps can create a latent resistance that indirectly stifles sustainability initiatives by shaping managerial attitudes and consumer behaviour. Cluster II (Dependent Barriers: EK4, SO7, SO9, LN11, LN12) is characterized by high dependence but low driving power, identifying them as outcomes of the system’s deeper issues. Barriers in this cluster, such as large initial costs, weak supplier collaboration, and inadequate regulations, are often the most visible symptoms but are not root causes. Their dependent nature aligns with findings that these challenges frequently arise from a lack of external support and internal capacity, where SMEs, due to their limited financial and structural resources, become highly susceptible to external pressures and institutional voids [25,66]. The most volatile and interconnected group is Cluster III (Linkage Barriers: EK1, EK2, LN10, LN13), which exhibits both high driving and high dependence. These barriers, including dependence on imported raw materials, minimal government incentives, and limited availability of eco-friendly inputs, form a self-reinforcing feedback loop. This cluster embodies the systemic linkage problems described in prior research, where variables are unstable and a change in one can create cascading effects throughout the entire system, making them critical leverage points for intervention [32,63]. Finally, Cluster IV (Independent/Driver Barriers: EK5) is comprised solely of “funding limitations,” which possesses the highest driving power and the lowest dependence. This positions it as the most critical, independent barrier, the foundational root cause of the system. This finding robustly confirms a central theme in SME sustainability literature: that financial constraints are the paramount, overriding obstacle that dictates the feasibility of all other sustainable procurement efforts, often overshadowing environmental and social considerations in decision-making [3,23]. This cluster-based typology thus provides a strategic map, distinguishing between superficial symptoms, unstable linkage variables, and the fundamental financial driver that must be addressed to enable a transition to sustainable procurement in SMEs.

4.10. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness of the Fuzzy MICMAC classification, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. The objective was to determine if the strategic classification of barriers would remain stable under variations in expert input, thereby testing the reliability of the findings. The analysis involved creating a modified Fuzzy Direct Relationship Matrix (FDRM) by systematically reducing the strength of high influences. All “Very High” influence scores (0.9) were downgraded to “High” (0.7), and all “High” influence scores (0.7) were downgraded to “Moderate” (0.5). This conservative scenario simulated the judgment of a more sceptical panel. The modified matrix was then processed through the identical Fuzzy MICMAC stabilization procedure. The resulting driving and dependence powers for all barriers were calculated and compared to the original results. The analysis confirmed the high robustness of the model, as the cluster membership of every barrier remained entirely unchanged. Most critically, EK5 (Funding Limitations) retained its position as the sole independent barrier in Cluster IV, unequivocally confirming its role as the fundamental driver of the system. The stability of the results under this conservative condition, as detailed in Table 14, strengthens the validity of our findings and the subsequent conclusions drawn for policymakers and managers.

Table 14.

Comparison of Driving and Dependence Power in Original and Sensitivity Analysis.

4.11. Analysis of Key Barriers in the Implementation of Sustainable Procurement in SMEs

The analysis reveals that financial constraints are not merely one barrier among many but the central, driving force inhibiting sustainable procurement in SMEs. This is starkly illustrated by the classification of “funding limitations” (EK5) as the sole independent barrier in Cluster IV, possessing the highest influence over the entire system. The significant cost disparity between local, sustainable raw materials and cheaper imported alternatives, coupled with the prohibitive expense of eco-friendly packaging, creates a fundamental economic disincentive. This finding strongly aligns with prior research, such as Gonçalves et al. [3], who identified cost as the most significant hurdle for SMEs, and Nasyiah et al. [23], who argued that financial constraints often overshadow environmental and social considerations in procurement decisions. The data confirms that without resolving this core financial viability issue, through innovative financing models or cost-mitigation strategies, other efforts to promote sustainable practices are likely to be ineffective, as SMEs simply lack the capital to invest.

Furthermore, the study identifies a critical “linkage” cluster (Cluster III) of interconnected systemic barriers, including high import dependency, lack of government incentives, and scarce sustainable raw materials. These barriers form a vicious cycle that reinforces the financial core problem. For instance, the lack of government incentives (EK2) exacerbates the cost issue, while limited local non-GMO soybean supply (LN13) forces SMEs to rely on the cheaper import market, thereby undermining the business case for sustainable sourcing. This interdependence echoes the work of Narayanan et al. [67], who found that barriers in sustainable supply chains are rarely isolated and often create cascading effects. Similarly, studies in developing economies, like those by Shaikh et al. [50], highlight how weak institutional support and underdeveloped local markets create a uniquely challenging environment for SME sustainable procurement, making a piecemeal approach insufficient. Therefore, tackling these linkage barriers requires a coordinated, multi-stakeholder strategy that simultaneously addresses policy, market structure, and supply chain development to break the cycle.

4.12. Analysis of Key Barriers Using Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM)

The application of the ISM methodology provides a critical hierarchical perspective, revealing that the barriers to sustainable procurement are not a flat list but a structured system with a clear power dynamic. The model’s most significant revelation is the identification of “funding limitations” (EK5) as the sole independent variable in Level IV, positioning it as the most powerful driver or root cause within the system. This structural finding is consistent with the foundational principles of ISM, which posit that factors at the lowest level of the hierarchy have the highest driving power [68]. In practice, this means that the high cost of sustainable raw materials and packaging is not just a standalone issue; it exerts fundamental pressure on the entire system. This corroborates prior ISM studies in supply chain contexts, such as the work of Gonçalves et al. [3], which also identified financial constraints as a key independent barrier in sustainable supply chain management, suggesting its foundational role is a common theme across different industrial contexts.

Delving deeper into the hierarchy, the ISM model elucidates the critical role of the “linkage” barriers in Cluster III (e.g., EK1, EK2, LN10, LN13). These barriers are characterized by high both driving and dependence power, making them unstable and critical leverage points. The model visually demonstrates how a barrier like “minimal government incentives” (EK2) is both influenced by the root funding problem and, in turn, directly influences the “availability of eco-friendly raw materials” (LN10) and reinforces “dependence on imports” (EK1). This interconnectedness creates a self-reinforcing feedback loop that is difficult to break. As noted by Mannan et al. [68], linkage variables in an ISM hierarchy are often the most complex to manage because any action on them can have unpredictable ripple effects. Our findings thus extend the research of Hussain et al. [69], who identified similar governmental and market barriers, by using ISM to map their precise position and dynamic role within the causal web, highlighting that interventions here require a systemic rather than a siloed approach.

4.13. Analysis of Key Barriers Using Fuzzy MICMAC

The Fuzzy MICMAC analysis provides a nuanced understanding of the influence and dependence relationships between barriers, moving beyond the binary linkages of traditional ISM to account for the real-world ambiguity in these connections. The classification of barriers into four distinct quadrants validates and refines the structural model. The most critical finding is the positioning of “funding limitations” (EK5) alone in the independent quadrant (Quadrant IV), confirming it possesses the highest driving power with very low dependence. This means that while EK5 exerts a strong influence on other barriers, it is largely unaffected by changes within the system itself. This finding aligns with the fuzzy-based supply chain studies of Khan and Haleem [70], who emphasized that financial barriers often emerge as autonomous “drivers” in complex systems, requiring targeted external intervention rather than expecting them to be resolved through internal system changes.

Furthermore, the Fuzzy MICMAC plot powerfully identifies the cluster of unstable “linkage” barriers (EK1, EK2, LN10, LN13) in Quadrant I, characterized by high both driving and dependence power. This quadrant is often described as the “volatile zone,” where variables are both key influencers and highly sensitive to changes in other variables [32]. For instance, the high dependence of “limited local non-GMO supply” (LN13) on factors like government incentives (EK2) and the high cost of local materials (driven by EK5) creates a feedback loop of dependency. This fuzzy clustering provides empirical weight to the qualitative insights of prior research, such as that of Abbas et al. [63], who noted that sustainable sourcing challenges are often a result of intertwined external pressures. The Fuzzy MICMAC analysis thus quantifies this volatility, suggesting that policies aimed at these linkage barriers, such as subsidizing local sustainable soybean cultivation, could have a high-leverage, multiplicative effect by simultaneously stabilizing multiple critical nodes in the barrier network.

4.14. Sustainability Procurement as a Managerial Strategy

The findings of this study highlight sustainable procurement not merely as a compliance measure but as a core managerial strategy that directly influences SME competitiveness and long-term viability. By addressing the root barrier of financial constraints and strategically engaging with linkage barriers such as dependence on imports and lack of government incentives, SMEs can create more resilient supply chains. Prior research suggests that integrating sustainability into procurement decisions enhances operational efficiency, reduces risks, and fosters stronger relationships with stakeholders [71]. However, unlike Walker and Preuss [51], who argue that cost is only one among several competing sustainability barriers, our results demonstrate that in emerging economies financial constraints function as the primary structural driver, shaping downstream institutional and operational challenges. This contrasts with studies in developed contexts where institutional support mitigates cost pressures, suggesting that SMEs in Indonesia face a more rigid financial–institutional dependency than previously reported. In resource-constrained environments, procurement managers who align sustainability objectives with cost-reduction and risk-mitigation strategies are more likely to secure buy-in from both top management and supply chain partners.

Moreover, adopting sustainability-oriented procurement practices positions SMEs to leverage institutional support and market opportunities. For example, government incentives, eco-certifications, and consumer demand for environmentally friendly products can provide SMEs with competitive differentiation when managers proactively integrate sustainability into procurement frameworks [72]. This finding is consistent with Nasyiah et al. [23], who emphasize the role of leadership in mobilizing sustainability capabilities; however, our results extend their conclusions by showing that such leadership effectiveness is contingent on resolving financial and institutional barriers first. Similarly, while Shaikh et al. [43] highlight sustainability as a pathway to competitive advantage, the current study adds that competitive gains materialize only when SMEs overcome systemic funding limitations, an insight less emphasized in prior models. Compared with Gonçalves et al. [3], who treat financial and institutional barriers individually, this study demonstrates their interdependence through a hierarchical ISM–MICMAC structure, offering a more integrated understanding of how procurement choices cascade across the system. This strategic orientation not only addresses external pressures but also creates internal value through innovation, enhanced reputation, and improved supplier collaboration. As this study indicates, managerial focus on overcoming funding limitations and fostering systemic interventions across linkage barriers transforms procurement from a transactional activity into a strategic tool for building sustainable advantage.

4.15. Theoretical Contribution and Sustainable Procurement Integration

This study makes a significant theoretical contribution by advancing the understanding of sustainable procurement barriers as a structured and interdependent system, rather than as isolated challenges. Using Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) and Fuzzy MICMAC, the research identifies financial constraints as the root driver with the highest influence, confirming earlier studies that cost remains the most significant hurdle for SMEs [51]. However, it extends prior work by mapping the causal relationships between barriers and showing how systemic issues, such as weak institutional incentives, limited local raw material supply, and high import dependency, operate as linkage variables within a self-reinforcing cycle [73]. This hierarchical approach enriches sustainability theory by demonstrating how certain barriers, while dependent, create cascading effects that amplify the core financial challenge, underscoring the value of systemic analysis in procurement research. From a practical perspective, the findings highlight that integrating sustainability into procurement cannot rely solely on operational adjustments or firm-level initiatives but must be embedded in broader financial, policy, and supply chain frameworks. As emphasized by Nasyiah et al. [23], SMEs in developing economies face intensified constraints due to weak institutional support, and this study reinforces the need for coordinated public–private collaboration to enable cost mitigation, incentivize sustainable sourcing, and strengthen local supply bases. In line with systemic perspectives in sustainable supply chain research [32,74], the results suggest that sustainable procurement integration must balance financial viability, institutional incentives, and resource availability through multi-stakeholder strategies, thereby ensuring that SMEs can overcome structural constraints and achieve long-term sustainability.

This study’s primary theoretical advancement lies in its methodological approach to barrier analysis. While previous studies have effectively used surveys and regression [27,43] to identify which barriers are significant, these methods treat barriers as independent variables, potentially missing the systemic picture. For instance, Shaikh et al. [43] identify cost and institutional pressures as important constraints but analyze them in isolation, without mapping how these constraints interact or cascade through the procurement system. In contrast, our integrated ISM-Fuzzy MICMAC approach reveals the structure of the problem. For example, we show that ‘cultural resistance’ (LN12) is not a standalone issue but a dependent barrier (Cluster II), influenced by more fundamental drivers like funding. This finding differs from earlier studies such as Walker and Preuss [51], which treat cultural and behavioral barriers as relatively autonomous; our results demonstrate that these barriers gain importance only after upstream financial and institutional challenges remain unresolved. Similarly, while Gonçalves et al. [3] highlight several sustainability barriers, they do not investigate their hierarchical relationships, leaving the underlying causal structure unexamined. This hierarchical result challenges studies that might place equal emphasis on all barriers and provides a evidence-based framework for prioritizing interventions, thereby addressing a key gap in the sustainable procurement literature for SMEs identified in Table 1.

4.16. Key Findings and Novel Insights