Abstract

Background: This study examines how Green Knowledge Integration Capability (GKIC) influences supplier performance within sustainable supply chains by balancing exploration (acquiring new knowledge) and exploitation (refining existing knowledge) strategies. Methods: Based on Social Exchange Theory, Relationship Motivation Theory, and Absorptive Capacity Theory, a conceptual model was developed and tested using cross-sectional survey data collected from 398 managers representing 240 multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in Pakistan. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was employed to analyse the relationships among exploration and exploitation focus, Green Management Innovation (GMI), GKIC, Green Absorptive Capacity (GAC), and supplier performance. Results: The findings indicate that exploration and exploitation strategies significantly enhance supplier performance, with GKIC acting as a mediating mechanism linking strategic focus and innovation to performance outcomes. Moreover, GAC strengthens the impact of the exploration and exploitation focus on performance but exhibits limited moderating effects for GMI and GKIC pathways. Conclusions: The results highlight GKIC’s critical role in translating strategic and innovation initiatives into supplier performance gains. This study contributes to the sustainable supply chain literature and provides actionable insights for managers and policymakers to enhance sustainability outcomes through knowledge integration and absorptive capacity development.

1. Introduction

The suppliers and buyers invest in their continued relationships, sharing knowledge to ensure effective governance mechanisms, cost reduction [1], and improvement in product performance [2]. The relationships between buyers/sellers are considered a competitive advantage for companies [3,4]. The concept of EE strategy has drawn substantial interest from scholars to evaluate the impact of GMI, strategic alliance, IO collaboration, GKIC, and SP. The EE are two distinct approaches to organisational learning, and recent literature has increasingly emphasised the importance of firms achieving a balance between them. The balance between EE is embedded in ambidextrous organisations. The prior literature concludes that there is little direct evidence to show a significant and positive association between ambidexterity and SP [5]. Meanwhile, combined or collaborative learning is directly linked to the organisation’s exploitation alliance [6]. However, these studies have not examined how prior exploitation alliances might later evolve into exploration alliances with the same partners, or how exploration alliances could transition into exploitation alliances.

Longitudinal evaluations deepen our understanding of partnership portfolios while balancing EE activities. Moreover, similar to the dynamics observed in commercial inter-firm alliances [7,8], firms are likely to leverage their alliance and partnership portfolios to (a) navigate the tensions between EE sustainable products, technologies, and processes; (b) address the competing demands of the triple bottom line of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic dimensions); and (c) reconcile the challenges of balancing short-term and long-term priorities. However, limited literature has been documented so far in the context of SP [9,10]. Some studies emphasise that while a single alliance within a day offers a focused space for learning, portfolios are more likely to provide a broader platform for addressing the tensions. Prior studies highlight GMI as a central driver of sustainable advantage due to its role in enhancing efficiency, quality, and productivity [11,12,13]. Strengthened environmental relationships further enhance competitiveness [14]. Good relationships with the natural environment are considered a vital component for greater competitiveness [14]. The prior literature has discussed the link between the natural environment and management practices.

Management practices can be seen in total environmental quality management, the implementation of environmental management systems, and energy management strategies [15,16]. These management practices facilitate firms in integrating environmental concerns embedded in business strategies, significantly improving the firm’s performance [15]. The unique context ensures the successful implementation of GMI in the firm. When firms prioritise internal efficiency in their efforts to go green, their innovative performance tends to improve [17]. We introduce GKIC, which refers to how an organisation can blend generic knowledge as well as environmental knowledge to shape novel environmental insights [18,19]. Its role as a mediating factor in the relationship between inter-organisational collaboration and suppliers’ performance was examined. In fact, ACT asserts that a company’s ability to identify, acquire, assimilate, and exploit new knowledge is essential to the absorbing of external knowledge. In effect, it has considerable effects on learning results. Grown on the foundation of environmental concerns, GAC, improved in research contexts, portraying a company’s capability to identify, acquire, internalise, and apply environmental knowledge in a dynamic environment, refers to processes of external knowledge absorption and learning outcomes [20,21]. It is also the fact that defines assimilation and processing of GKM, leading to improved GKIC. We, therefore, investigate the moderating role of GAC between inter-organisational learning and GKIC.

Organisational learning theory also holds that firms shall leverage their environments to reach a deeper understanding and form strategies on how to respond through learning [22,23]. In other words, corporations can pursue GKM by learning from other external corporations. In dynamic technological and market environments, innovation is mandatory to ensure competitiveness [24], and thus, the absorptive capacity of firms becomes the most critical determinant of learning success [25]. Based on this premise, firms must develop a rational inter-organisational learning plan. The present study considered multinational corporations listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX hereafter) as the population for the current study. The present study considered lower-, middle-, and upper-level managers as respondents, as these positions hold the information about the multinational corporations’ policies and practices. The findings of the present study can facilitate the managers, board of directors (BOD hereafter), investors, policymakers, and regulatory authorities in understanding the significant role of EE focus and Green Management Innovation in predicting the SP.

1.1. Theoretical Significance

The present study combines the “SET” and RMT to evaluate the association between EE focus, GMI, and SP. In addition, the present study introduced the mediating role of GKIC between EE focus, GMI, and SP. Furthermore, the present study evaluates the moderating role of GAC between the EE focus, GMI, GKIC, and SP, also including another theory that addresses the rational behaviour of human actors, the Social Exchange Theory [26]. Apart from the clear economic advantages of sharing and exchanging information, SET sheds light on the motivations of human actors. Human and social behaviour and economic endeavours can be explained using the SET, as SET can illuminate on receiving of conditional or positive responses from associated persons [27]. In the social contexts, exchange mechanisms are evaluated using SET. This theory emphasises that the interaction processes between parties are central to social exchange, where the behaviour of one participant affects and prompts responses from the other.

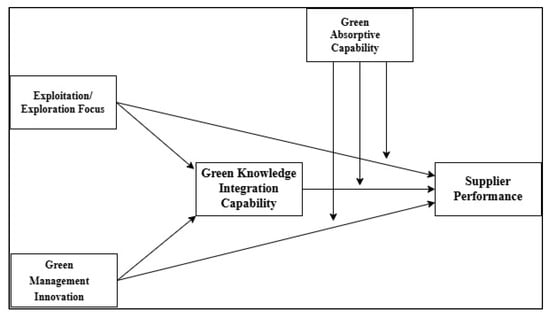

The RMT is rooted in multiple domains, including services marketing, business marketing, database marketing, various marketing channels, and direct marketing [28]. Studies in the domain of RMT intend to outline the association among the consumers and companies from the association with the other consumers and companies, which intend to explain how and why organisations or customers build strong relationships with each other [28]. The underlying foundation of RMT is (1) network-based (inter-organisational) and (2) market-based (consumer-focused). The RMT and SET were combined to investigate how EE focuses on GMI and SP. Given this context, the following is a summary of the suggested theoretical model, shown in Figure 1. EE focus and GMI influence SP through GKIC, defined as “the process of enhancing future behaviour in a relationship” [29].

1.2. Practical Significance

The MNCs significantly contribute to the total exports, economic growth, and employment generation. The present study intent to outline the implications for the managers, BOD, stakeholders, investors, policymakers, government of Pakistan, and regulatory authorities to understand the significance of EE focus, GMI, and GKIC towards SP with the moderating role of GAC. Sustainable performance of suppliers leads to competitive advantage [30]. As the MNCs operate in a highly competitive environment, hence the prior literature affirms that it is vital to evaluate the potential factors that influence SP. The prior literature intents to evaluate the potential resources and capabilities that organisations need to develop by the MNCs to survive in highly competitive environments to attain an SP. Furthermore, the prior literature indicates that GMI is significantly associated with the SP, particularly in the adoption of a new organisational system and structure, which improves the management and production processes to mitigate the negative environmental concerns [31].

Moreover, the literature affirms that the organisational capability in combining environmental and general knowledge can facilitate the management of the competitive position based on new environmental knowledge [18,19]. Furthermore, the earlier GAC theory and literature claims that firms can acquire, identify, assimilate, and use new knowledge to facilitate the firms in competing in a highly competitive environment [21,32,33]. The empirical estimation of the present study facilitates the managers, BODs, investors, policymakers, and regulatory authorities in understanding the role of factors in SP of MNCs in Pakistan. This study outlines the possible implications for managers in understanding the role of individual latent constructs towards SP. Furthermore, using the PLS-SEM as the empirical estimation intents to facilitate the managers in understanding the prediction power of latent constructs in the proposed model of the present study.

2. Review of the Literature

The emerging literature emphasises that achieving an ambidextrous balance between exploitation (refining existing knowledge) and exploration (seeking new solutions) is critical for sustainability, yet the relationship with supplier performance remains inconsistent and underexplored [5,34]. While some studies find that ambidexterity enhances performance through dynamic capability [8], others highlight trade-offs and challenges that limit direct performance gains [35]. Moreover, supplier performance in multinational supply chains, especially in emerging economies, is influenced by relational governance, knowledge sharing, and institutional conditions. Although prior research recognises the importance of Green Management Innovation (GMI) for improving environmental outcomes [20], evidence linking GMI to supplier performance is mixed and likely conditional on knowledge integration mechanisms. The limited literature has specifically analysed how GKIC transmits EE focus and GMI into supplier performance outcomes in 2023–2025 contexts, despite growing calls to integrate sustainability, knowledge-based capabilities, and performance models. These gaps justify examining (a) the direct link between EE focus and SP, (b) the mediating role of GKIC, and (c) the conditional role of GAC in enhancing supplier performance within sustainable supply chains.

2.1. Exploitation/Exploration Focus and Supplier Performance

In the literature, the emerging themes commonly seen in theoretical and empirical investigations are EE focus with GKIC. The vital and emerging themes show how much work has been carried out on this topic [34]. Exploitation was previously associated with extraction, such as further refining and expanding the assets lying within an organisation’s control, in terms of generating expected positive returns that are reliable and predictable [35]. However, more studies have also unearthed uncertainty returns [35]. Thus, EE focus should not have to be viewed separately [36]. The existing research also discusses the limited studies that tend to address the contending alternatives of exploring new unknowns or exploiting current abilities [36] concerning the difficulty in balancing between these two. Larsson et al. (1998) [37] discussed the trade-offs between the two. However, unlike previous studies discussing balancing EE focus, this study is based mainly on how focusing on one rather than the other turns out to be a strategic choice for a number of reasons, the first of which is that EE are inherently trade-offs [35] and, therefore, it may bring some point in the evolution of the firm in which it must decide to orient itself more toward EE.

The exploitation focus refers to the way problems are being solved through current means and resources, which is seen as quite passive and dependent. Exploration focus, on the other hand, pertains to a firm’s inclination to inquire about solutions through new means and resources, thus being a more proactive and creative approach. To trust their partners and adopt a more strategic approach to their motives. Such will often be supplied with very great experience from safe channels through which external knowledge and resources are supplied, with great experience from secure channels to their buyers. This symbolises a process of cautiousness, avoiding risk, and maintaining stability.

The key capability here is absorptive learning capability (ALC hereafter), which is crucial for the reliable absorption of existing knowledge [35]. ALC becomes a more substantial antecedent of innovations in organisations whose strategic inclination is exploitation compared to those who focus on exploration. Moreover, exploitation strategies encourage suppliers to adopt more secure, reliable, and less adventurous solutions compared to those sought after for more challenging and innovative ones. Thus, firms may build their ALC for the effective absorption of externally linked knowledge or resources that are perceived as stable or safe, thereby minimising their dependence on joint learning capability (JLC hereafter), which may lead to expert incompetence [38].

To summarise, exploitation-focused firms, which focus more on reliable and existing methods for problem-solving, are inclined to strongly align them with the joint applications of learning capacity. Absorptive learning capability refers to the profound relationship impacts on innovation-specific relationships when a supplier opts for exploitation rather than exploration. In contrast, if a firm becomes increasingly innovative in a proactive and adventurous manner with problem solutions, as with exploratory firms, joint learning capacities such as JLC will have a larger incremental ontogenetic relationship with innovation. Accordingly, this draws us to our hypothesis.

H1:

Exploitation/Exploration focus is significantly related to supplier performance.

2.2. Green Management Innovation and Supplier Performance

The GMI shows itself strongly by first inducing encouragement, determined by promoting sustainability by enhancing operational excellence and giving value in cost advantage. This goes with GMI as a process that involves green strategies like eco-design, green procurement, and sustainable product development, which significantly minimise environmental impacts while at the same time improving supplier performance and legal and market compliance. In a world adopting GMI in response to growing demands for sustainability, GMI is one way of achieving optimal as well as the most sustainable environmental performance for organisations. GMI comprises management practices on resource-efficient production, waste reduction, and the use of sustainable technologies [20]. This paper will thus discuss GMI’s significance because organisations are determined to face environmental challenges while still being competitive.

This situation enables suppliers to adopt industry benchmarks and green certifications, enhancing their competitiveness and value through knowledge integration. On the other hand, proactive suppliers also implement green business processes in close alignment with their strategies for achieving environmental leadership or improved sustainability across their entire supply chain network. Increasingly, as the global world turns towards GMI in answering higher demands for sustainability, GMI for an organisation promises the most optimal and sustainable environmental performance. To make matters worse, organisations have implemented additional operational changes and expect their suppliers to adopt green values, as supplier performance is another key driver for GMI programmes [39].

In a supply chain, GMI introduces innovative green products, promotes optimal utilisation of resources, and facilitates compliance with environmental legislation [40]. Moreover, with proper green knowledge integration, GMI improves supplier performance while reducing environmental impacts and further develops a competitive marketing position. Through green knowledge integration capabilities, the link between GMI and supplier performance is established. GMI is a type of innovation management for organisations that develop and implement new green methods of management. With increased focus on sustainability, it has rapidly gained momentum among organisations within their value chains in applying new GMI. This participatory process integrates sustainability issues and participatory cooperation, as well as innovation, in crucial decision-making for the environment. Research in the last decade has sustained the narrative of how GMI improves supplier performance. GMI reinforces sustainability by encouraging both collaboration and innovation in supply chains [41]. GMI also stands as a vital pillar linking organisational capabilities to SP or outcomes. Hence, the present study proposed the following hypothesis.

H2:

Green Management Innovation is significantly related to supplier performance.

2.3. Green Knowledge Integration Capability as Mediator

Organisational learning is critical for any organisation, and exploitation along with exploration goes hand in hand with developing significant GKIC. Exploitation is making use of best practices and improvement of existing approaches, and exploration is the quest for new knowledge and experimenting with new approaches. Having a good balance for exploitation and exploration is necessary for the growth of GKIC. While exploitation produces immediate and visible payoffs through improving environmental initiatives currently implemented, exploration leads to future advancements through testing new sustainable solutions. Luo et al. (2022) [42] explained that striking a balance between these two aspects is highly critical, as overemphasis on one will reverse and negatively affect performance.

The role of GKIC is further supported by the Knowledge-Based View (KBV), which argues that knowledge is the most strategically valuable resource for competitive advantage, particularly when firms can integrate and apply knowledge across organisational boundaries [17,18,19,42]. In a sustainability context, integrating environmental knowledge enables firms to co-create value with suppliers by reducing uncertainty and information asymmetry. Moreover, Absorptive Capacity Theory (ACT) clarifies that external green knowledge contributes to performance only when firms possess the capability to assimilate, transform, and apply it to operational decision-making [33]. GKIC therefore represents a capability bundle through which firms convert shared sustainability knowledge into superior supplier outcomes, ensuring alignment of green practices, enhanced compliance, and improved performance within supply chains [39]. This theoretical integration positions GKIC as a central mechanism that translates both innovation efforts and ambidextrous strategies into supplier performance gains in emerging-market supply chains.

In addition, production processes and productivity improvements will also lead to better environmental performance [43]. Although existing studies provide an enlightening reference for demonstrating the nexus between environmental innovation and performance, they draw limited insights from the traditional innovation literature [44]. Environmental pressure from a wide range of stakeholders encourages firms to incorporate environmental issues into their innovative agendas. However, the primary driver for innovation remains the formulation of new products or services that can satisfy consumer needs. Such innovation may lead to an increase in supplier performance [45]. Hence, we analyse the contributory effect of innovative capabilities of the firm rather than just environmentally innovative capabilities on environmental performance, since this conventional literature within innovation helps to broaden further understanding of the effect of innovation activities, among others, towards environmental innovation.

GKIC mediates the impact of EE and GMI on SP. It helps to integrate and share green knowledge throughout the supply chain, allowing suppliers to obtain the data necessary to enact and support sustainability strategies effectively. Green exploratory innovations have begun helping organisations discover new ways of addressing environmental challenges. On the other hand, exploitative green innovations rely on knowledge accumulated to carry out sustainable environmental management. Nonetheless, the successful implementation of such innovations faces various barriers, including the EE’s use of knowledge resources and collaboration with suppliers. Such issues result in what scholars call integrative green knowledge in firms, thus enhancing their environmental adaptability and improving SP regarding sustainability and green innovation [46,47]. Based on the above discussion, the present study proposed the following hypotheses:

H3:

Green Knowledge Integration Capability significantly mediates the relationship between inter-organisational collaboration and supplier performance.

H4:

Green Knowledge Integration Capability significantly mediates the relationship between exploitation/exploration focus and supplier performance.

H5:

Green Knowledge Integration Capability significantly mediates the relationship between Green Management Innovation and supplier performance.

2.4. Green Absorptive Capacity as Moderator

A substantial body of the literature explains a firm’s ALC, along with its key features [48,49,50]. For this research, ALC will be defined as an organisation’s capacity to practice absorptive learning in an exchange relationship [51]. Absorptive learning is conceived as a dynamic process in which two firms try to absorb the other company’s knowledge and resources [52]. According to the latest research, GAC plays a moderating role between EE focus, GMI, and SP. GAC is the organisation’s capacity to obtain and utilise external green knowledge for developing sustainable transformation throughout the supply chain. It is, as research shows, a GAC that makes a company better able to forge suppliers’ commitment to environmental standards for their products and processes. For example, GAC promotes green market orientation, facilitating the absorption of external knowledge and enhancing suppliers’ green compliance [53].

This would consequently enhance company–supplier collaboration, leading to overall improved performance within the supply chain. It has been said that GAC, with a strong implication, thus determines the company’s ability to forge suppliers’ commitment to environmental standards for their products and processes. GAC fosters a green market orientation that facilitates the absorption of external knowledge and enhances suppliers’ green compliance [53]. The above discussion highlights that this relationship fosters a more collaborative working environment with suppliers, leading to an improved performance throughout the entire supply chain. GAC benefits environmental performance by facilitating knowledge sharing that enables organisations to better respond to supplier requirements. This potential endows the facilitation of green knowledge integration, which promotes eco-efficiency and encourages more cooperation to improve suppliers’ practices toward sustainability.

Previous studies have shown that there is an interplay between GAC and knowledge integration mechanisms in enhancing operational performance by reducing resource waste and promoting the effective adoption of green technologies across the supply chain [53,54]. Organisational innovation through exploitation/exploration is important for organisational performance [34,52]. Interest among partners can lead to new ideas and innovations through knowledge sharing, information exchange, and resource utilisation. Past research indicates that (inter-)organisational learning, leading to organisational knowledge, acts as a precursor to innovation for different fields like marketing, management, or even economics. A notable example is provided by Cohen and Levinthal (1990) [48] and Kogut and Zander (1992) [18].

The GAC is the hypothetical moderator between the Green Knowledge Integration Capability and the effectiveness of suppliers. Green knowledge integration examines the extent to which environmental knowledge is shared within the supply chain. GAC, however, is about the way that suppliers take up this knowledge and put it to use. The higher the GAC in a company, the better able it will be to acquire and internalise the direction coming from outside, that is, green knowledge, which acts positively on supplier performance outcomes. This finding is supported by studies by Taticchi et al. (2020) [55] and Lee et al. (2024) [56], which demonstrate how GAC breaks down barriers related to top management, technology, and resistance to change, thereby creating the most enabling conditions for knowledge transfer. Thus, it plays a significant mediating role in the impact of green knowledge integration on more effective and successful green practices by suppliers. This mediation role provides further encouragement for developing strong interfirm cooperation and absorptive capacity, thereby achieving superior environmental performance across the supply chain [57].

Additionally, the recent literature suggests that GAC affects the impact of Green Management Innovation on supplier performance. According to the latest research, GAC is responsible for moderating the relationship between Green Knowledge Integration Capability and supplier performance. GAC reflects organisational capability to acquire and utilise external green knowledge to develop sustainable changes in the entire supply chain. Indeed, a stronger GAC enhances a firm’s ability to forge a supplier’s commitment to environmental standards applicable to their products and processes. Examples include when Du and Wang (2022) [53] established that this mechanism prompts organisations to adopt a green market orientation, thereby ending external knowledge absorption and improving green compliance among suppliers. The above illustration states that this constitutes more than other stuff that facilitates improvement in overall supply chain performance. Based on the above discussion the present study proposed the following hypotheses.

H6:

Green Absorptive Capacity significantly moderates the relationship between inter-organisational collaboration and supplier performance.

H7:

Green Absorptive Capacity significantly moderates the relationship between exploitation/exploration focus and supplier performance.

H8:

Green Absorptive Capacity significantly moderates the relationship between Green Management Innovation and supplier performance.

H9:

Green Absorptive Capacity significantly moderates the relationship between Green Knowledge Integration Capability and supplier performance.

Recent studies in green supply chain management emphasise the integration of sustainability with ambidextrous learning and capability development, documenting both performance benefits and boundary conditions in 2020–2023 contexts [42,46]. This emerging work also underscores the centrality of knowledge mechanisms in translating green initiatives into supplier-level outcomes, particularly under institutional constraints. Our study extends this frontier by isolating GKIC as the transmission channel and assessing GAC as a selective boundary condition for performance. While recent ambidexterity research in sustainable operations reports positive links with performance, findings remain mixed when supplier outcomes are considered, pointing to unobserved capability effects and contextual variability [42]. This reinforces the need to test knowledge-based mediators and absorptive moderators in EE–performance relationships.

2.5. Theoratical Foundation

This study integrates three complementary theoretical perspectives to explain how strategic orientations and innovation practices translate into sustainable supplier performance. Social Exchange Theory (SET) offers the relational foundation by emphasising reciprocity, trust, and mutual commitment in buyer–supplier interactions, which underpin knowledge sharing and cooperative governance in sustainable supply chains [58,59]. These mechanisms explain why parties are motivated to exchange and safeguard green knowledge to pursue long-term benefits and reduce opportunism [60,61]. However, while SET clarifies the relational motives for exchange, it does not fully capture how firms purposefully assemble and deploy resources to achieve performance under sustainability constraints. Resource Mobilisation Theory (RMT) adds this strategic lens by explaining how organisations marshal internal and external resources, i.e., financial, technological, and relational, to address sustainability challenges; in our context, RMT clarifies how firms build and deploy Green Knowledge Integration Capability (GKIC) to convert exchanged knowledge into process and performance outcomes [62]. Yet mobilised resources and strong exchange relationships do not automatically produce results unless firms can learn from, assimilate, and apply the knowledge they access.

Absorptive Capacity Theory (ACT) completes the framework by focusing on the routines through which external knowledge is acquired, assimilated, transformed, and applied; its green instantiation, Green Absorptive Capacity (GAC), conditions whether exploration–exploitation strategies and green innovations are effectively converted into supplier performance improvements [63]. Sustainable supply chain management (SSCM hereafter) focuses on knowledge-based exchanges and economic exchanges (e.g., contract, pricing) [64]. While SET highlights trust, its role in GKIC-driven supplier relationships is underexplored [65]. In short, SET explains relational enablers, RMT explains resource orchestration, and ACT/GAC explains learning-based conversion mechanisms; all three are necessary and complementary, particularly in emerging-market contexts where institutional voids heighten dependence on relational governance and knowledge capabilities [66,67].

The recent literature raises key questions: Does GKIC build on pre-existing trust or increase the trust level among collaborative partners? How do GKIC alter traditional power dynamics using SET? Does GKIC reinforce the MNCs’ dominance by reducing the asymmetries through green knowledge sharing? [66]. The SET assumes universal exchange norms, but Pakistani collectivist culture and weak institutions may reshape reciprocity [63]. Is it important to understand how mutual exchange achieved using GKIC? Do informal networks in the supply chain of MNCs influence the green absorption capability in Pakistan? [67].

In Pakistan, MNCs often impose sustainability requirements unilaterally without providing supplier capacity-building [46]. This violates SET’s reciprocity principle, potentially eroding trust. Weak legal enforcement shifts sustainability compliance to relational contracts [47]. Also, suppliers in Pakistani MNCs prioritise long-term and short-term sustainability [63]. Past studies have also examined the immediate incentives (e.g., technology transfers, absorption capacity) that can enhance GKIC adoption [63,66,68].

In emerging economies such as Pakistan, institutional voids, including weak regulatory enforcement, lack of environmental monitoring systems, and inconsistent sustainability standards, create heightened uncertainty in buyer–supplier exchanges [46,63]. In such environments, suppliers often rely more on informal relational governance, increasing the importance of trust and reciprocity as emphasised by SET. Conversely, countries like China and India have made stronger progress in environmental infrastructure and supplier capability-building through coordinated policy interventions, enabling more structured diffusion of green knowledge [42,47]. Thus, in Pakistan, relational mechanisms play a more prominent role in enabling GKIC, and capability-driven pathways (EE-to-GKIC-to-SP) may serve as compensatory mechanisms for institutional weaknesses. This context underscores the theoretical relevance of integrating SET, RMT, and ACT to understand how sustainability outcomes emerge despite institutional deficiencies found in many South Asian supply chains [66,67].

The main constructs used in our model [Figure 1] are defined at first mention and used uniformly thereafter. Exploration–exploitation (EE) focus denotes a firm’s strategic orientation toward simultaneously refining existing knowledge (exploitation) and seeking new knowledge (exploration) to enhance performance [35,36]. Green Management Innovation (GMI) comprises organisational practices such as eco-design, green procurement, and process changes aimed at improving environmental and operational outcomes [20]. Green Knowledge Integration Capability (GKIC) refers to the firm’s ability to acquire, assimilate, and integrate environmental knowledge from internal and external sources to support sustainability strategies and coordination with suppliers [18,19]. Green Absorptive Capacity (GAC) captures the routines through which firms acquire, assimilate, transform, and apply external green knowledge (the ACT micro-processes) to realise performance benefits [48].

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

3. Methodology

Considering the theoretical and empirical research gap proposed in existing literature, the present study intends to offer the mediating role of GKIC and moderating role of GAC between EE focus, GMI, and SP using the SEM technique. The empirical findings of the present study intends to contribute to the domain of supply chain underpinning the SET, as the underpinning objective of the present study is to theoretically contribute to but extend the SET by empirical testing of the mediating role of GKIC between EE focus, GMI, and SP [61]. Furthermore, the present study intends to evaluate the moderating role of GAC between EE focus, GMI, GKIC, and SP. The cross-sectional design was adapted using a short-survey-based research approach, which consisted of 25 questions and required 15 to 20 min to complete. The “invitation to participate” was generated using a QR code and shared using email(s) and social media platforms (LinkedIn) to potential respondents current working with MNCs at lower-, middle-, and senior-level management positions.

The current study considered the foreign and local 242 MNCs operating in Pakistan as the proposed population. The present study considered 240 MNCs as the proposed sample for data collection using a survey questionnaire, with representatives from lower-, middle-, and upper-level managers serving as representatives of MNCs, employing a purposive sampling technique (non-probability sampling). The earlier literature claims an approximately 42.5% response rate in survey-based studies; hence, the present study distributed 903 survey questionnaires to achieve 384 responses from various managerial-level positions [69]. In response to the distribution of the survey questionnaire, approximately 402 responses were received, and 398 responses were used for data analysis, resulting in a response rate of 43.88% for testing.

3.1. Measurement Tools

The survey questionnaire includes the standard demographics: gender, education, age, position, firm size, and experience. All measurement variables were rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). The present study considered the following key variables: exploitation/exploration focus (5 items), Green Management Innovation (using 4 items), Green Absorptive Capacity (4 items), Green Knowledge Integration Capability (using 4 items), and supplier performance (7 items). Table 1 presents the measurement of variables using dimensions, items, minimum and maximum values, Cronbach’s alpha, and composite reliability.

Table 1.

Variables measurement.

Each construct was measured using validated scales adapted from the prior literature. The complete list of items has been provided in Appendix B.

The exploitation–exploration focus (EEF) construct was measured using five items (EFE1–EFE5) drawn from the organisational learning and ambidexterity literature. Items reflecting exploration (EFE1–EFE_3) capture behaviours related to searching for new environmental solutions, experimenting with sustainable practices, and encouraging innovation, consistent with [35,36]. Items reflecting exploitation (EFE4–EFE5) represent the refinement of existing green routines and the use of accumulated environmental knowledge to improve efficiency. These indicators were selected because they reflect the complementary dimensions of ambidexterity that underpin adaptive and efficiency-driven sustainability practices, as supported by prior studies (e.g., [40,47]).

Green Absorptive Capacity (GAC) was operationalised using four items (GAC1–GAC4) adapted from Absorptive Capacity Theory [48] and subsequent sustainability-focused applications. These items capture a firm’s ability to identify, assimilate, transform, and apply external environmental knowledge, capabilities that are essential in emerging-market supply chains facing institutional voids. The selected indicators align with prior empirical work emphasising the role of knowledge assimilation and application in advancing environmental performance (e.g., [49]), They ensure that GAC is represented as a multidimensional learning capability relevant to green supplier development.

Green Knowledge Integration Capability (GKIC) was measured using four indicators (GKIC1–GKIC4) grounded in the knowledge-based view [19] and organisational knowledge integration theory [18]. These items capture the firm’s ability to combine, coordinate, and apply environmental knowledge from internal and supply chain partners. Their selection reflects evidence that collaborative knowledge routines, such as cross-functional learning, partner information sharing, and integrated decision-making, play a major role in translating sustainability initiatives into operational performance [42,56]. Thus, the chosen items represent the essential mechanisms through which green knowledge contributes to supplier outcomes.

Green Management Innovation (GMI) was assessed using four items (GMI1–GMI4) that reflect innovative managerial actions aimed at improving environmental performance through process redesign, technology adoption, resource efficiency, and institutionalising green decision-making. These indicators draw from established eco-innovation and green management literature [20,43] and capture the extent to which firms introduce novel environmental practices. These items were selected as representative of the core dimensions of green managerial innovation that directly influence the adoption of sustainable technologies and practices across supply chains.

Supplier performance (SP) was measured using seven items (SP1–SP7) adapted from operational and environmental performance scales commonly used in green supply chain management research [43]. These items assess compliance with environmental requirements, improvements in eco-efficiency, contribution to waste reduction, reliability in sustainable operations, and overall alignment with buyer sustainability goals. They were selected because they capture the multidimensional nature of supplier performance in sustainability contexts, covering both operational and environmental outcomes that are central to green supplier evaluation frameworks.

3.2. Unit of Analysis and Sampling Approach

The unit of analysis in this study is the supplier performance outcome as perceived by managers of multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in Pakistan, consistent with prior sustainable supply chain research relying on managerial assessments [46,47]. A sampling frame of 240 MNCs was developed using publicly available listings from the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX), chambers of commerce, and leading industrial directories, ensuring inclusion of both foreign and local MNCs relevant to supply chain sustainability. A purposive sampling technique was used to target lower-, mid-, and senior-level managers with direct knowledge of inter-organisational collaboration and performance policies [69].

3.3. Procedural and Statistical Remedies for Common Method Variance (CMV)

To reduce CMV, anonymity and confidentiality were assured, scale items were randomised, and predictor and criterion constructs were separated in the survey layout [22,23]. Post hoc CMV assessment using Harman’s one-factor test indicated that no single factor explained the majority of variance (first factor = 37.1%), confirming CMV was not a critical concern [24]. In addition to Harman’s one-factor test, a marker variable approach was employed to assess common method variance bias, confirming no inflation of correlations among focal constructs (∆R2 < 0.02), consistent with recommended guidance for PLS-SEM studies [22,23]. Furthermore, reflective measurement assessment confirmed adequate convergent and discriminant validity through AVE > 0.50, CR > 0.70, and HTMT < 0.85 thresholds, ensuring robust measurement properties [69,70].

3.4. Non-Response and Endogeneity Checks

Non-response bias was examined by comparing early vs. late respondents, showing no significant differences in demographic or key construct values (p > 0.10). Additionally, given the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be confirmed, and potential reverse causality is acknowledged as a limitation; longitudinal and multi-respondent studies are recommended to address this issue more robustly [10,33].

3.5. Respondents Demographics

Table 2 presents the results of the demographics and the percentages of sample respondents. The first section displays statistical measures, including the mean, standard deviation, kurtosis, skewness, minimum, and maximum values for each variable. The present study codes the genders as 0 and 1, with a mean value of 0.58, which implies that the male gender is slightly more prevalent than the female gender. Education, age, and position are measured on ordinal scales (ranging from 1 to 3 or 1 to 4), with indicates central tendencies; for instance, age averages close to 2, implying most respondents fall in the middle category.

Table 2.

Demographic and percentage of the sample.

The negative skewness and kurtosis values for gender, education, age, position, and size suggest relatively flat distributions and slightly left skewness; however, experience indicates a positive kurtosis (1.04) and skewness (1.46) which indicates that the graph is rightly skewed which indicates that most respondents are at lower experience level. The second section details the frequencies of position categories. The largest group of respondents is from business or market department managers, which represents 36.92% of the total respondents, followed by domestic/local and foreign/overseas sales, which account for approximately 18.84%. CEOs and presidents constitute the smallest segment (7.79%). The total sample size of 398 indicates the distribution across all departments. These insights help contextualise the respondents’ professional backgrounds, which may influence subsequent analyses.

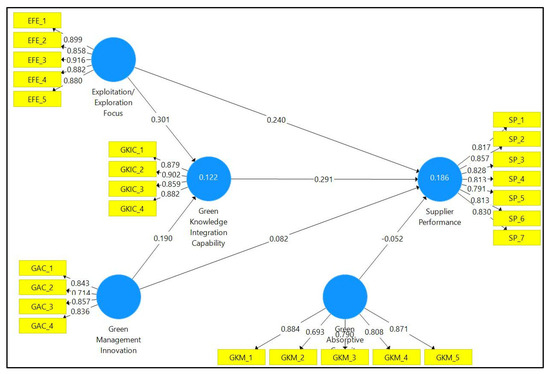

3.6. Respondents Demographics

Table 3 and Figure 2 report on the reliability and validity of constructs considered in the present study. Reliability and validity are assessed based on multiple indicators, including factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). The first variable EE focus construct demonstrates strong reliability and validity, as evidenced by loadings of items greater than 0.85, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.933, a composite reliability of 0.949, and an AVE of 0.788, indicating strong internal consistency and convergent validity, as all indicators meet the threshold values. Similarly, the GAC construct demonstrates good reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.893, CR = 0.906), although one item (GAC_2) has a lower loading (0.693), which may slightly compromise its validity. The GKIC construct indicator performed exceptionally well, as the items loaded above 0.85, and other metrics included Cronbach’s alpha (0.903), composite reliability (0.932), and AVE (0.775). The GMI construct is also reliable (Alpha = 0.834, CR = 0.887), though GMI_2 has a relatively lower loading (0.714). The last construct, SP, exhibits high reliability, as all loadings are above 0.79, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.920, and composite reliability is 0.936, indicating strong internal consistency. The AVE values for all constructs exceed 0.50, supporting convergent validity, while the high CR values confirm consistent measurement.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity.

Figure 2.

Assessment of measurement model.

To ensure model adequacy, collinearity and discriminant validity were assessed prior to structural evaluation. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for all constructs were below 3.0, confirming the absence of multicollinearity concerns, while the HTMT ratios were all below the 0.85 threshold, supporting discriminant validity [70]. The structural model demonstrated satisfactory explanatory power, with R2 = 0.41 for supplier performance, indicating moderate variance explanation. Predictive relevance was further confirmed by Q2 = 0.29, indicating that the model possesses acceptable predictive capability. Mediation and moderation effects were tested using 5000 bootstrap resamples with bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals, in line with recommended PLS-SEM guidelines [69]. Interaction terms interpretability [Appendix A] was created through mean-centring of predictor and moderator variables to reduce multicollinearity and improve. Regarding effect sizes, Cohen’s f2 values indicated medium-to-large contributions for EE focus (0.164) and GKIC (0.291), whereas GMI (0.330) and GAC (0.201) demonstrated small-to-medium effects, highlighting stronger explanatory contributions from strategic ambidexterity and knowledge integration capabilities.

Table 4 reports the discriminant validity using the HTMT technique. The results indicate that all the constructs meet the threshold value of 0.85 as per the strict school of thought [70]. With both discriminant and convergent validity confirmed, the constructs are deemed suitable for hypothesis testing in the structural model.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

4. Results

4.1. Hypothesis Testing

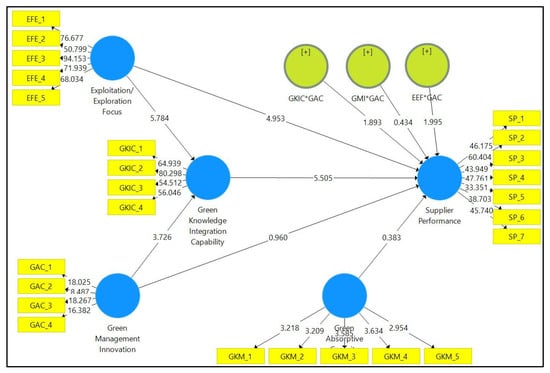

Table 5 reports on the direct relationship among the latent constructs. The results from the path analysis reveal significant and non-significant relationships between the predictors and supplier performance. EE focus indicates a significant and positive association with the supplier performance (β = 0.252, p < 0.001), with a value of f-square of 0.164, which indicates a medium effect. The results infer that balancing between EE significantly improves the supplier’s performance. The empirical findings indicate that GMI has a positive yet insignificant effect on the supplier’s performance (β = 0.095, p = 0.343, t = 0.948). The value of f-square is 0.33, which indicates that large effect size. Moreover, GKIC demonstrates a strong positive influence (β = 0.299, p < 0.001, t = 5.542), suggesting that effective integration of green knowledge significantly boosts supplier outcomes. The value of f-square is 0.291, which indicates that large size effect. The results indicate that GKIC significantly and positively improves the supplier’s performance. Furthermore, GAC indicates an insignificant yet positive association with the supplier’s performance in the case of a direct relationship (β = 0.051, p = 0.710). Despite the direct relationship, the indicated association is not statistically significant, with an f-square value of 0.201, indicating a medium effect size. The findings highlight that while knowledge integration and strategic focus are critical drivers, green management practices and absorptive capacity may require additional mediating or moderating factors to influence performance effectively.

Table 5.

Direct relationship.

Table 6 reports the results of the indirect relationship between EE focus, GMI, and GKIC. The path analysis results indicate that both EE focus and GMI have a statistically significant positive influence on GKIC. The empirical findings indicate that balancing between EE activities more effectively predicts the GKIC (β = 0.301, p < 0.001, t = 5.856). The f-square value is 0.103, which indicates a medium-sized effect. Moreover, GMI also shows a significant but comparatively weaker impact (β = 0.190, p < 0.001, t = 3.787), implying that GMI practices contribute to, but are less decisive than, strategic EE focus in enhancing GKIC. However, the value of f-square is 0.141, indicating a medium-sized effect, which is comparatively higher than the EE focus. These findings underscore the significance of a dual strategic orientation (exploitation and exploration) as a primary driver of GKIC, with GMI serving a supportive yet secondary role. The empirical findings indicate that organisations aiming to improve the GKIC need to prioritise focusing on EE and GMI for optimal results.

Table 6.

Indirect relationship.

Table 7 reports the mediation relationship of GKIC between EE focus, GMI, and SP. The empirical findings indicate that GKIC significantly and positively mediates the relationship between EE focus, GMI, and SP. The results indicate that GKIC significantly and positively mediates the relationship between EE focus and SP at a 1% level of significance (β = 0.090, p < 0.001, t = 3.546). This indicates that a firm’s ability to balance EE enhances SP primarily by improving its capacity to GKIC. Furthermore, the empirical findings suggest that GKIC significantly and positively mediates the relationship between GMI and SP at a 1% level of significance (β = 0.057, p = 0.003, t = 2.962), despite the direct relationship indicating that GMI positively yet insignificantly improves SP. This suggests that while GMI contributes to SP, its impact is partially channelled through improved GKIC. The results affirm that GKIC is considered a possible channel through which EE focuses and GMI improve SP.

Table 7.

Mediating relationship.

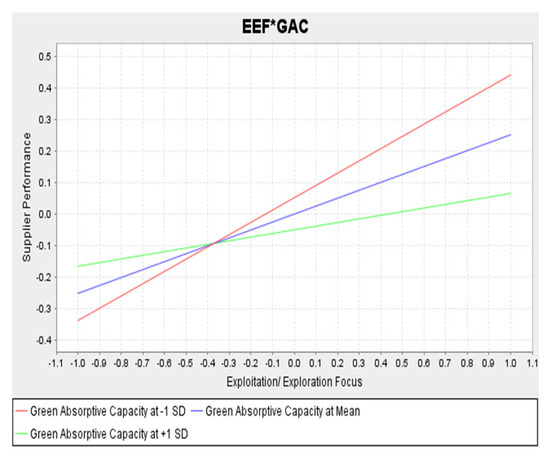

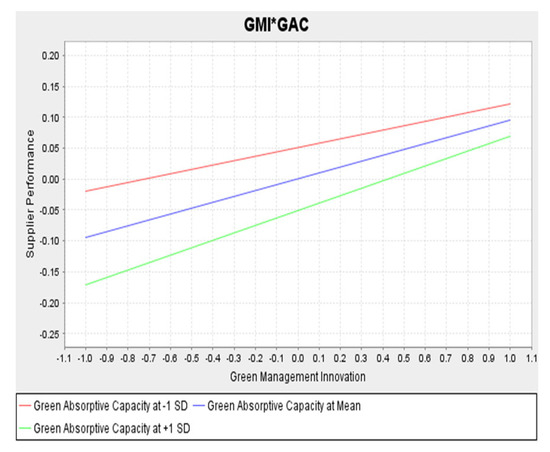

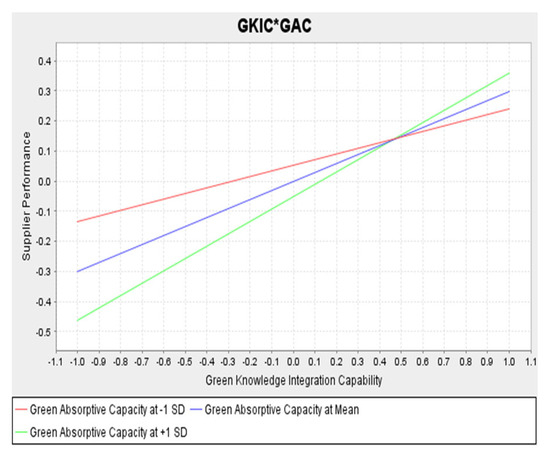

Table 8 and Figure 3 report the results of the moderation analysis. The present study proposed that GAC moderates the relationship between EE focus, GMI, GKIC, and SP. The interaction between EE focus and GAC [Figure A1] has a positive and statistically significant effect on SP (β = 0.137, p = 0.050, t = 1.962), indicating that firms with higher GAC can more effectively leverage their strategic balancing of exploitation and exploration activities to enhance SP. The empirical findings affirm that GAC acts as an enabler in transforming strategic ambidexterity into superior supplier outcomes through improved knowledge assimilation and utilisation. Moreover, the empirical findings indicate that although GAC positively moderates the relationship between GMI and SP [Figure A2] (β = 0.025, p = 0.670), this effect is statistically insignificant, implying that green managerial initiatives alone may not yield performance benefits unless they are supported by strong absorptive routines. Furthermore, the empirical findings show that the moderating effect of GAC on the relationship between GKIC and SP [Figure A3] is positive yet statistically insignificant at conventional thresholds (β = 0.112, p = 0.055), reflecting a marginal trend toward significance. These results collectively suggest that while GAC enhances the translation of strategic ambidexterity into supplier performance, its enabling influence on green innovation and knowledge integration pathways may require higher capability levels or additional contextual enablers to become fully effective and robust.

Table 8.

Moderating relationship.

Figure 3.

Assessment of structural model.

The selective moderation effect of GAC supports the argument that absorptive routines are path-dependent, meaning they evolve primarily from existing knowledge bases [33,48]. As EE focus emphasises refining current practices while exploring new solutions, firms with stronger GAC can more swiftly internalise and exploit environmental knowledge, translating ambidexterity into performance gains [46]. However, GMI and GKIC may not benefit equally from GAC at all stages. Green innovations often require new routines, technologies, and partner alignment before their impact materialises, and thus their value realisation depends on longer-term organisational learning cycles [20]. Likewise, GKIC already captures assimilation and integration mechanisms, making GAC’s additional contribution less distinctive unless firms have achieved higher maturity in knowledge transformation routines [47]. Consequently, the moderating influence of GAC is more apparent where strategic ambidexterity leverages accumulated knowledge stocks, rather than in contexts where innovation or integration requires creating and codifying new environmental practices [42]. These results highlight that GAC enhances performance most effectively when building on existing learning trajectories rather than initiating novel sustainability capabilities.

4.2. Findings and Discussion

The findings offer critical insights into the mechanisms through which EE focus, GMI, and GKIC influence SP, with GAC playing a contingent role. The present study contextualises the findings within the recent literature and, based on the discussion in the next section, outlines the theoretical and practical implications. The significant positive effect of EE focus on SP (β = 0.252, p < 0.001) aligns with ambidexterity theory [8,31], which posits that balancing exploitation (refinement of existing knowledge) and exploration (pursuit of new knowledge) enhances organisational adaptability and performance. The empirical findings extend the existing literature in the domain of supply chain research, which affirms that ambidextrous balance strategies significantly improve the supplier outcome through dynamic capability [5]. GMI’s insignificant direct effect on SP (β = 0.095, p = 0.343) contrasts with studies linking green innovation to performance [31,41]. This discrepancy in empirical findings might reflect the contextual factors in Pakistani MNCs, where institutional voids or insufficient supplier capacity limit the immediate impact [54,63]. Recent work by Du and Wang (2022) [53] suggests that GMI’s benefits often materialise indirectly through knowledge integration, which our mediation analysis supports.

In addition to that the mediation results indicate that GKIC’s pivotal role acts as a “knowledge bridge” between EE focus and SP (β = 0.090, p < 0.001) as well as GMI and SP (β = 0.057, p = 0.003) [67]. This aligns with SET, as GKIC facilitates reciprocal knowledge sharing between MNCs and suppliers, fostering trust and long-term collaboration [62]. The empirical findings indicate that stronger mediation for EE focus, as compared to GMI, suggests that ambidextrous strategies are more effective than standalone innovations in cultivating GKIC, balancing exploitation and exploration [42].

The significant moderation of EE focus × GAC → SP (β = 0.137, p = 0.050) supports GAC [48]. Firms with high GAC better leverage ambidextrous strategies to drive SP, as they can assimilate and apply external green knowledge [33]. The empirical results affirm that GAC significantly mitigates the tensions in sustainable supply chains [10]. However, GAC insignificantly moderates the relationship between GMI (β = 0.025, p = 0.670), GKIC (β = 0.112, p = 0.055), and SP. GMI’s operational nature (e.g., eco-design, waste reduction) may not require extensive knowledge absorption, whereas GAC partially amplifies GKIC’s impact, consistent with Pacheco et al. (2018) [21].

The empirical findings indicate that EE focus and GKIC significantly improve the SP, while the recent literature emphasises ambidexterity in sustainable supply chains [42,46]. The strong mediating effect of GKIC suggests that firms leveraging both existing and new knowledge more effectively integrate green practices, leading to improved supplier outcomes. The findings of the present study are well aligned with recent literature which affirms that knowledge integration is pivotal for competitive sustainability [66,71]. However, the empirical findings of the present study indicate that GMI had no direct impact on SP, contradicting but aligning with the fact that, often, SP depends on contextual factors such as GAC [10].

The moderating role of GAC was significant only for the EE focus–SP link, suggesting that GAC amplifies the benefits of strategic ambidexterity, but not those of standalone GMI or GKIC. The earlier literature claims that GAC efficacy depends on the type of knowledge being absorbed by collaborative partners [33]. The near-significant moderation for GKIC (p = 0.055) hints at a potential threshold effect, where only high GAC levels may unlock GKIC’s full potential [53].

These findings indicate that the performance value of GMI may be conditional, emerging only when firms possess strong knowledge integration routines. Similarly, GAC’s selective influence highlights a contextual boundary condition, where absorptive routines reinforce ambidextrous strategies more effectively than new green practices, especially in emerging markets with heterogeneous supplier capabilities.

The finding that GMI does not directly enhance supplier performance suggests that adopting green innovations alone may not be sufficient to deliver operational improvements without the presence of enabling knowledge capabilities. One explanation relates to implementation gaps, where eco-innovations are introduced but not fully embedded into supplier routines due to limited codification, training, or resource alignment [45]. Additionally, supplier heterogeneity in emerging economies creates variation in technological readiness, meaning GMI outcomes rely heavily on suppliers’ ability to absorb and operationalize green practices [46,47]. Drawing on eco-innovation theory, GMI often prioritises environmental improvements that do not immediately translate into efficiency or performance gains unless complemented by strong learning systems [20,39]. Further, diffusion of innovation theory highlights that innovation benefits unfold gradually as knowledge diffuses across supply chain partners [44]. Therefore, without robust GKIC mechanisms to assimilate, transform, and apply environmental knowledge, GMI may remain symbolic or compliance-driven rather than value-creating. This supports our empirical observation that GKIC transmits the performance value of GMI by enabling suppliers to translate innovation initiatives into tangible process improvements.

5. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

This study examined how EE focus, GMI, and GKIC influence SP in sustainable supply chain mechanisms among the MNCs, with the moderating role of GAC. The empirical findings of the present study reveal that EE focus significantly and positively influences the SP, implying that balancing the refinement of existing knowledge (exploitation) and the pursuit of new knowledge (exploration) enhances supplier outcomes. However, GMI has a positive yet insignificant effect on the SP in the case of a direct relationship. Additionally, GKIC significantly and positively mediates the relationship between EE focus, GMI, and SP. The empirical findings indicate that GKIC plays a critical mediating role, significantly transmitting the effects of EE Focus and GMI to SP. GKIC was found to be pivotal for transforming strategic and innovative efforts into performance gains. Thus, based on the result, GAC should be considered as a moderating factor in the relationship between EE focus, GMI, GKIC, and SP.

The empirical findings indicate that GAC acts as a key moderator, significantly amplifying the relationship between EE Focus and SP. Contradictorily, GAC positively yet insignificantly moderates the relationship between GMI and SP, and only marginally enhances the relationship between GKIC and SP. The present study aims to contribute to the literature by advancing the discourse on sustainable supply chains through the theoretical integration of SET, RMT, and ACT, and empirically validating the mediating role of GKIC. Furthermore, the presence of GKIC as a mediating construct significantly improves the role of GMI towards the SP in the context of MNCs, despite MNCs operating in developing countries like Pakistan, with a weak institutional environment. The results affirm that EE focus and GKIC are key drivers of SP, while the conditional role of GAC facilitates the capacity-building. This indicates that GKIC and balancing EE focus are non-negotiable, but their payoff depends on context-specific enablers, such as absorptive capacity. The empirical findings of the present study are well aligned with the existing literature, SET, and Absorptive Capacity Theory.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The empirical findings provide several theoretical advancements, particularly regarding the roles of EE focus, GMI, and GKIC. First, the significant influence of EE focus on supplier performance reinforces ambidexterity theory by demonstrating that simultaneously balancing exploitation and exploration enhances operational outcomes in sustainable supply chains [5,8]. Second, while GMI alone did not produce significant direct performance outcomes, its positive indirect effect through GKIC clarifies that green innovations require knowledge integration mechanisms to be successfully absorbed by suppliers, which advances the nascent discourse in green innovation theory [20,53]. Third, the strong mediating effect of GKIC extends the Social Exchange Theory (SET) by demonstrating that integrating environmental knowledge facilitates reciprocity, trust, and equitable value creation between buyers and suppliers, thereby reducing power asymmetries and fostering long-term relational stability [58,63,67]. Finally, the selective moderating role of GAC builds on Absorptive Capacity Theory (ACT) by showing that absorptive routines strengthen the benefits of ambidextrous strategies but may not uniformly benefit all green practices unless cognitive readiness and learning structures are well-developed [33,48]. Therefore, this study integrates and extends SET, RMT, and ACT by illustrating how relational, capability-based, and learning-driven mechanisms jointly shape supplier outcomes in emerging economies.

5.2. Practical Implications

The results outline several implications for practitioners operating within multinational supply chains. First, as EE focus directly enhances supplier performance, MNC managers should simultaneously invest in refining current green practices and exploring new sustainability solutions, ensuring a balanced ambidextrous strategy [42,46]. Second, the insignificant direct influence of GMI suggests that green process innovations alone are insufficient; rather, firms must channel and combine them through GKIC to unlock performance value. Therefore, managers should prioritise digital and relational infrastructures that facilitate cross-functional knowledge sharing, collaborative green teams, and supplier development programmes [39,41]. Third, given that GAC strengthens the influence of EE focus on performance, capacity-building initiatives such as joint training, technology transfer, and environmental knowledge-sharing platforms should be implemented to enhance suppliers’ ability to absorb green knowledge [53]. In settings like Pakistan’s MNCs, where institutional weaknesses exist [63], relational and capability-driven initiatives become critical for sustaining SP gains. This highlights policy implications for government bodies to incentivize sustainability investments and governance structures that empower suppliers in emerging markets to meet global sustainability standards.

To translate these results into practice, MNCs can strengthen GKIC by implementing supplier knowledge-sharing platforms, digital green collaboration systems, and joint capacity-building programmes focused on eco-innovation and environmental compliance. Establishing cross-organisational training on eco-design practices and reverse logistics processes can support suppliers in integrating sustainability knowledge into product and material flows. Moreover, collaborative innovation workshops and continuous feedback mechanisms can improve supplier learning cycles and accelerate the applied benefits of green initiatives.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its theoretical and practical contributions, this study includes several limitations that offer valuable directions for further inquiry. First, the cross-sectional survey design limits causal inference; future studies should adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to capture dynamic shifts in exploration–exploitation strategies over time [10,33]. Second, data were collected from a single country and context, MNCs operating in Pakistan, which may restrict the generalizability of findings; future research should extend the analysis to other emerging and developed economies to validate context-specific effects of institutional environments [46,63]. Third, due to reliance on single-respondent, self-reported measures, common method bias risks remain despite statistical remedies; future research should incorporate multi-respondent dyadic data, objective supplier performance metrics (e.g., sustainability rating scores), and secondary data triangulation to enhance validity [24]. Lastly, future work may explore additional boundary conditions such as supplier bargaining power, organisational culture, and digitalisation capabilities that could strengthen or weaken the role of GKIC and GAC in sustainability-driven performance [62,71]. The current study examined the various strategic capabilities; however, information technology-related capabilities were not explored. Thus, future studies should consider how innovation and digital tools can further optimise these relationships [72,73].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and S.M.G.; Methodology, S.K.; Software, S.K. and S.M.G.; Validation, S.K. and S.M.G.; Formal analysis, S.K. and S.M.G.; Investigation, S.K.; Resources, S.K.; Data curation, S.K.; Writing—original draft, S.K.; Writing—review & editing, S.M.G.; Visualization, S.K.; Supervision, S.M.G.; Project administration, S.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Institute of Post Graduate Studies—IPS Research Committee (protocol code IPS/R/02/23/004 and 15 February 2023 of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author according to reasonable requests due to this study being based on primary data collected via a self-administered questionnaire. Participation was entirely voluntary, with informed consent secured from all respondents. No identifying information was collected, ensuring confidentiality. Ethical clearance was obtained from the relevant institutional body.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

Appendix A. Interaction Term GAC Between EE Focus, GMI, GKIC, and SP

Figure A1.

* Interaction term GAC between EE focus and SP.

Figure A2.

* Interaction term GAC between GMI and SP.

Figure A3.

* Interaction term GAC between GKIC and SP.

Appendix B. Sources of Measurement Instrument

Appendix B.1. Exploitation–Exploration Focus (EEF)

Adapted from March (1991) [35]; Levinthal & March (1993) [36]; Larsson et al. (1998) [37]; Holmqvist (2003) [38]. (Two reflective sub-constructs: Exploration and Exploitation)

| Code | Measurement Item | Source(s) |

| EEF_EX1 | We frequently experiment with new sustainability ideas. | March (1991) [35]; Levinthal & March (1993) [36] |

| EEF_EX2 | We actively explore novel environmental solutions. | March (1991) [35]; Larsson et al. (1998) [37] |

| EEF_EX3 | We encourage risk-taking to find innovative green practices. | Holmqvist (2003) [38] |

| EEF_IM1 | We systematically improve existing sustainability procedures. | Levinthal & March (1993) [36] |

| EEF_IM2 | We refine operational processes to enhance eco-efficiency. | Holmqvist (2003) [38] |

| EEF_IM3 | We leverage accumulated environmental knowledge for improvements. | Larsson et al. (1998) [37] |

Appendix B.2. Green Management Innovation (GMI)

Adapted from Chen & Yang (2022) [20]; Montabon et al. (2007) [43]

| Code | Measurement Item | Source(s) |

| GMI1 | We implement innovative practices to reduce environmental impacts. | Chen & Yang (2022) [20] |

| GMI2 | We upgrade technologies to improve sustainable operations. | Montabon et al. (2007) [43] |

| GMI3 | We redesign processes to use resources more efficiently. | Chen & Yang (2022) [20] |

| GMI4 | Eco-friendly thinking is embedded in strategic decisions. | Montabon et al. (2007) [43] |

Appendix B.3. Green Knowledge Integration Capability (GKIC)

Adapted from Kogut & Zander (1992) [18]; Grant (1996) [19]

| Code | Measurement Item | Source(s) |

| GKIC1 | We effectively integrate environmental knowledge from multiple departments. | Grant (1996) [19] |

| GKIC2 | We collaborate with partners to share sustainability knowledge. | Kogut & Zander (1992) [18] |

| GKIC3 | We maintain systems supporting cross-functional environmental learning. | Grant (1996) [19] |

| GKIC4 | Integrated sustainability knowledge informs operational decisions. | Kogut & Zander (1992) [18] |

Appendix B.4. Green Absorptive Capacity (GAC)

(Aligned with name used in hypotheses H6–H9). Adapted from Cohen & Levinthal (1990) [48]; Malhotra et al. (2005) [49]; Lichtenthaler (2009) [50]

| Code | Measurement Item | Source(s) |

| GAC1 | We identify valuable external environmental knowledge. | Cohen & Levinthal (1990) [48] |

| GAC2 | We assimilate sustainability information rapidly. | Malhotra et al. (2005) [49] |

| GAC3 | We transform environmental knowledge into operational processes. | Lichtenthaler (2009) [50] |

| GAC4 | We apply absorbed knowledge to improve supplier-related practices. | Cohen & Levinthal (1990) [48] |

Appendix B.5. Supplier Performance (SP)

Adapted from Montabon et al. (2007) [43]; Govindan et al. (2020) [54]

| Code | Measurement Item | Source(s) |

| SP1 | Our suppliers consistently meet environmental requirements. | Montabon et al. (2007) [43] |

| SP2 | Supplier initiatives enhance environmental compliance performance. | Govindan et al. (2020) [54] |

| SP3 | Suppliers improve our resource efficiency and waste reduction outcomes. | Montabon et al. (2007) [43] |

| SP4 | Supplier collaboration enhances our sustainable operational performance. | Govindan et al. (2020) [54] |

| SP5 | Our suppliers support our broader sustainability goals. | Montabon et al. (2007) [43] |

| SP6 | Suppliers contribute positively to our green innovation efforts. | Govindan et al. (2020) [54] |

| SP7 | Supplier performance improves our overall environmental competitiveness. | Montabon et al. (2007) [43] |

References

- Um, K.H.; Oh, J.Y. The Interplay of Governance Mechanisms in Supply Chain Collaboration and Performance in Buyer–Supplier Dyads: Substitutes or Complements. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, A.; Lado, A.A.; Chen, I.J. Inter-organizational communication as a relational competency: Antecedents and performance outcomes in collaborative buyer–supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D.; Rosenkopf, L. Balancing exploration and exploitation in alliance formation. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, Q. Supply chain collaboration: Impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, J.; Kauppila, O.P.; Sepulveda, F.; Gabrielsson, M. Turning strategic network resources into performance: The mediating role of network identity of small- and medium-sized enterprises. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2020, 14, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. Cross-sector alliances for corporate social responsibility: Partner heterogeneity moderates environmental strategy outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D. Alliance portfolios and firm performance: A study of value creation and appropriation in the US software industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1187–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D.; Stettner, U.; Tushman, M.L. Exploration and exploitation within and across organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 109–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhengiz, T. The relationship of organisational value frames with the configuration of alliance portfolios: Cases from electricity utilities in Great Britain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhengiz, T. Organisational Value Frames and Sustainable Alliance Portfolios: Bridging between the Theories. In Proceedings of the Corporate Responsibility Research Conference (CRRC), Tampere, Finland, 11–13 September 2019; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, M.J.; Birkinshaw, J. The sources of management innovation: When firms introduce new management practices. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, R.; Vezzani, A. The economic impact of technological and organizational innovations. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveh, E. The effect of integrated product development on efficiency and innovation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2005, 43, 2789–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Alfaro-Barrantes, P. Pro-environmental behavior in the workplace: A review of empirical studies and directions for future research. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2015, 120, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Hor, W.L. Impacts of energy management practices on energy efficiency and carbon emissions reduction: A survey of Malaysian manufacturing firms. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The future of management: Where is Gary Hamel leading us? Long Range Plan. 2008, 41, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Zander, U. Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organ. Sci. 1992, 3, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, H. Green management innovation and firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 450–468. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, L.M.; Alves, M.F.R.; Liboni, L.B. Green absorptive capacity: A mediation-moderation model of knowledge for innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, C.M.; Lyles, M.A. Organizational learning. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L. Organizational learning research: Past, present and future. Manag. Learn. 2011, 42, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M. Organizational learning: A review of some literatures. Organ. Stud. 1993, 14, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.P. Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, F.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr. Power in Supply Chain Management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.D.; Arnett, D.B.; Madhavaram, S. The explanatory foundations of relationship marketing theory. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2006, 21, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selnes, F.; Sallis, J. Promoting Relationship Learning. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, T.; Fink, C. The Comprehensive Business Case for Sustainability. Harvard Business Review. 21 October 2016. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/10/the-comprehensive-business-case-for-sustainability (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Qi, G.; Chen, Y.; Mao, X.; Hui, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Xue, H. Model inversion attack via dynamic memory learning. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 5614–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]