Prioritization Model for the Location of Temporary Points of Distribution for Disaster Response

Abstract

1. Introduction

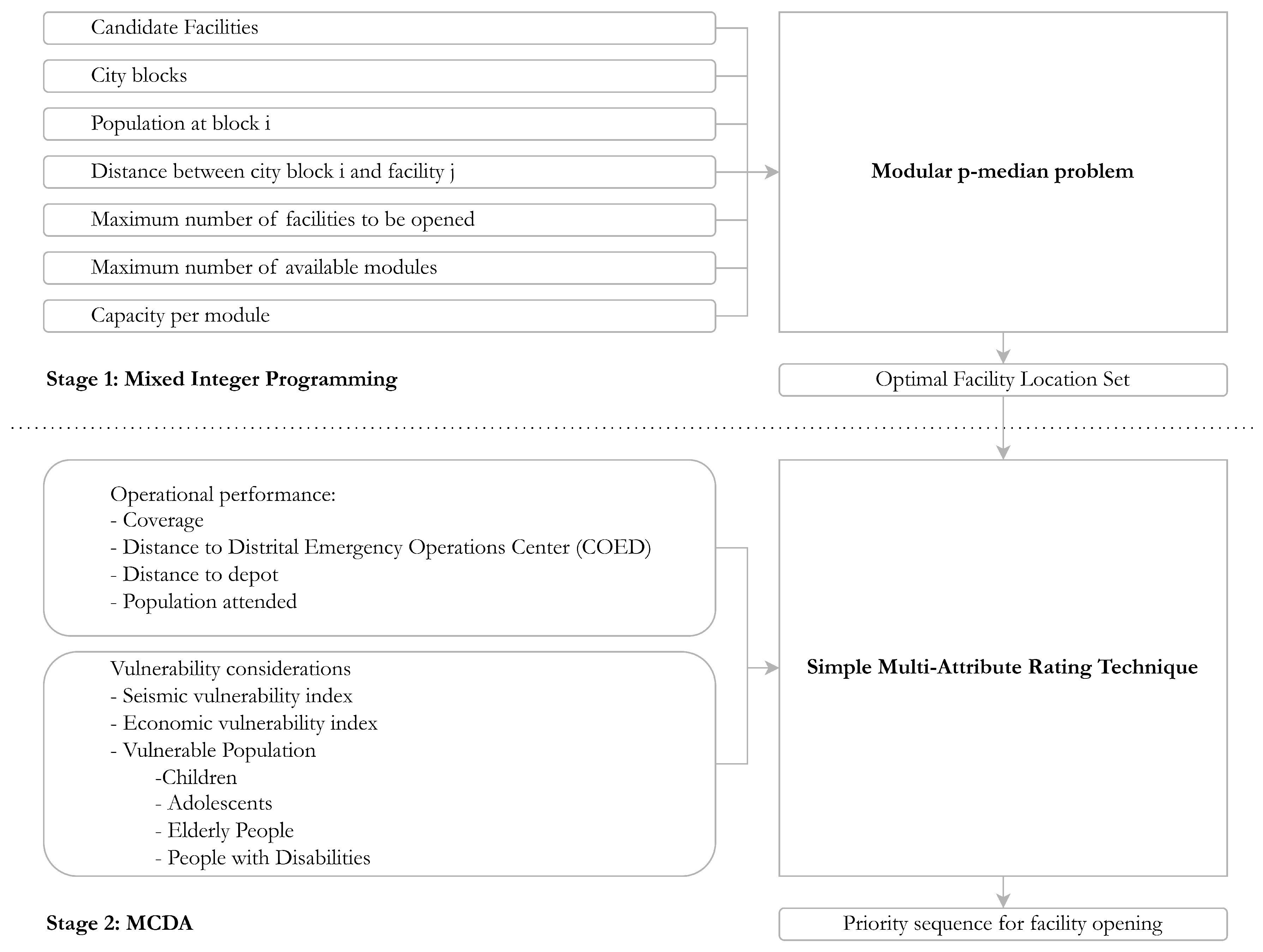

- Development of a compact mixed-integer model that minimizes the total demand-weighted distance while respecting the modular capacity constraints that limit the demand served per facility.

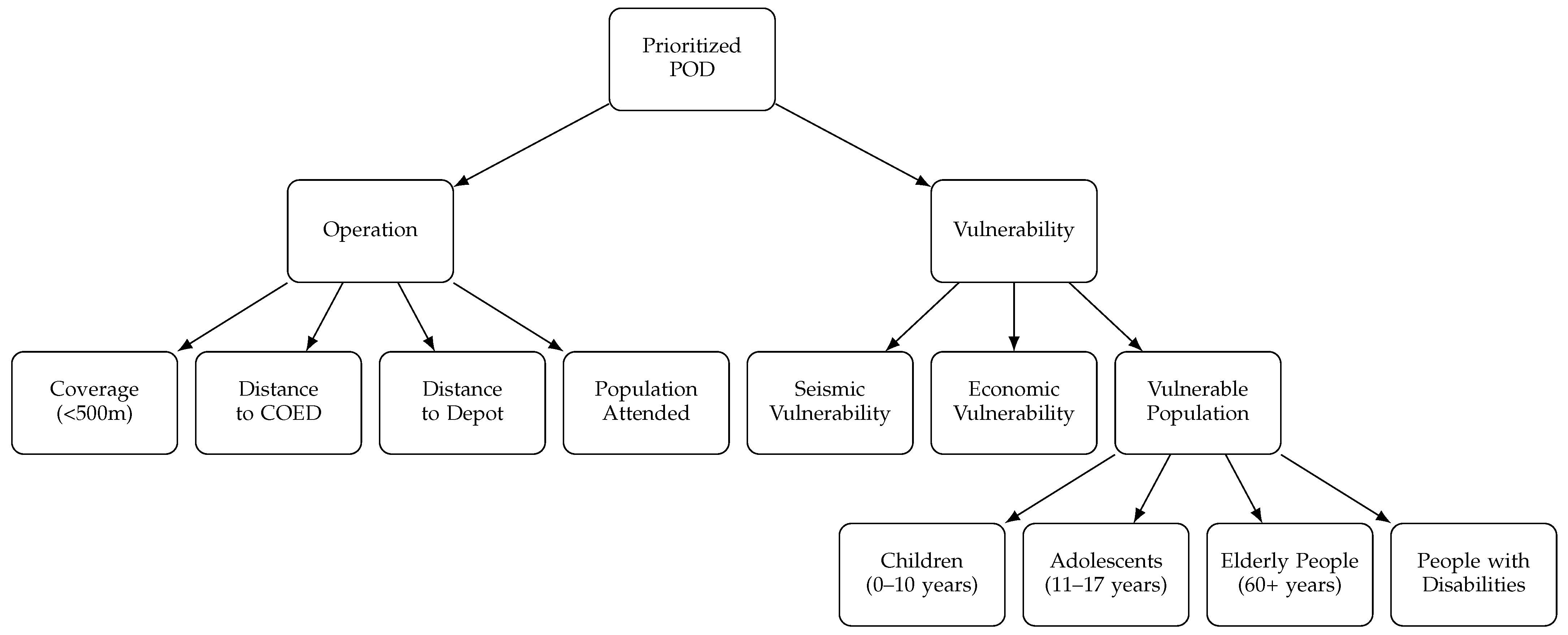

- Integration of a two-stage decision-making process: the first stage optimizes the network design with the mathematical model, while the second stage applies the SMART method to complement the model results. This multi-criteria approach enables the inclusion of additional attributes that would otherwise make the mathematical formulation excessively complex.

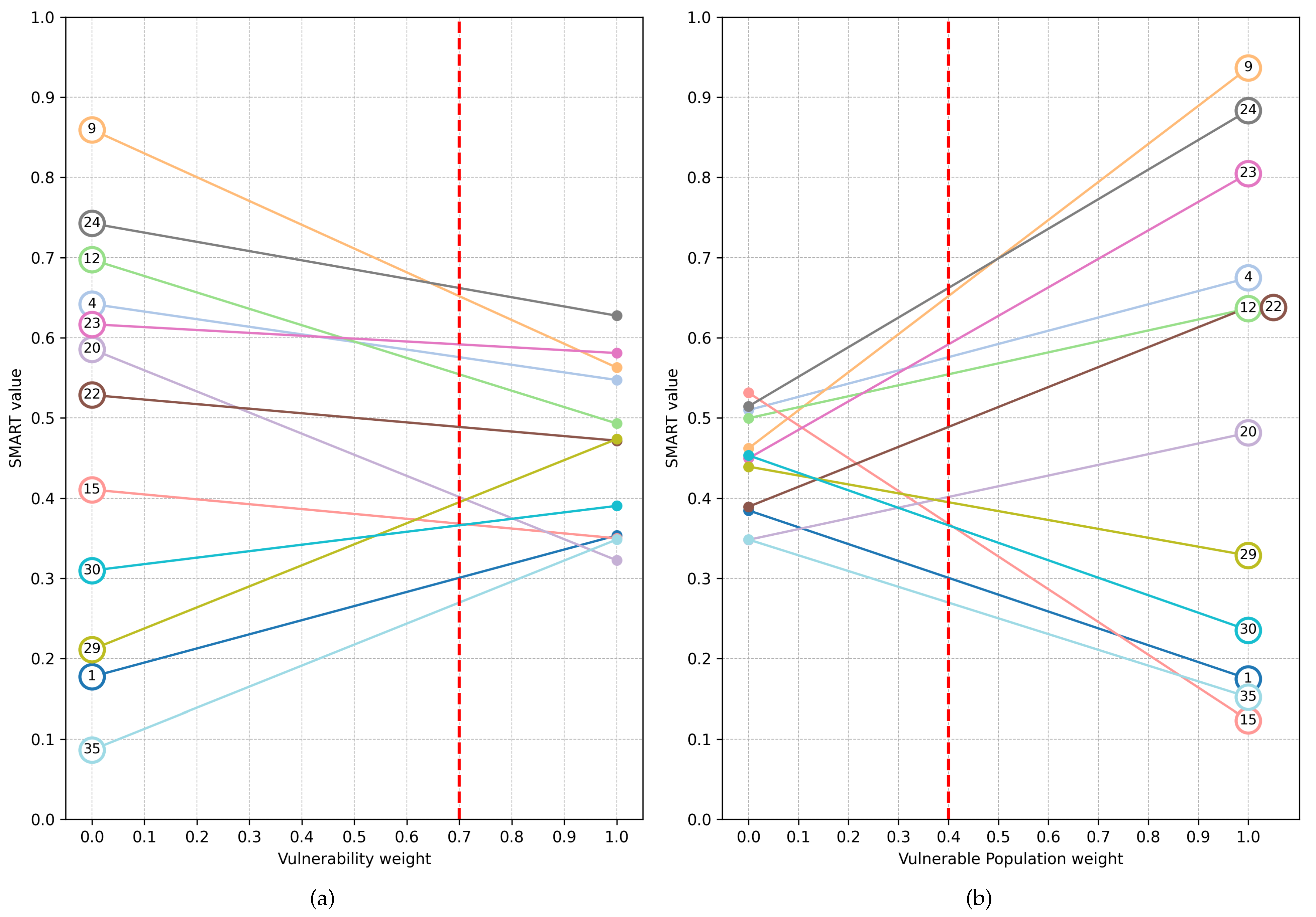

- Sensitivity analysis is a key component of multi criteria approaches, as it allows evaluating how changes in decision-makers’ preferences affect the results. This is particularly important given that decision-makers may change with the arrival of a new government.

- The application of the proposed two-stage framework to a real case study shows that combining modular facility allocation with a multi criteria approach that incorporates decision-maker preferences can enhance operational performance while also accounting for vulnerability considerations.

2. Literature Review

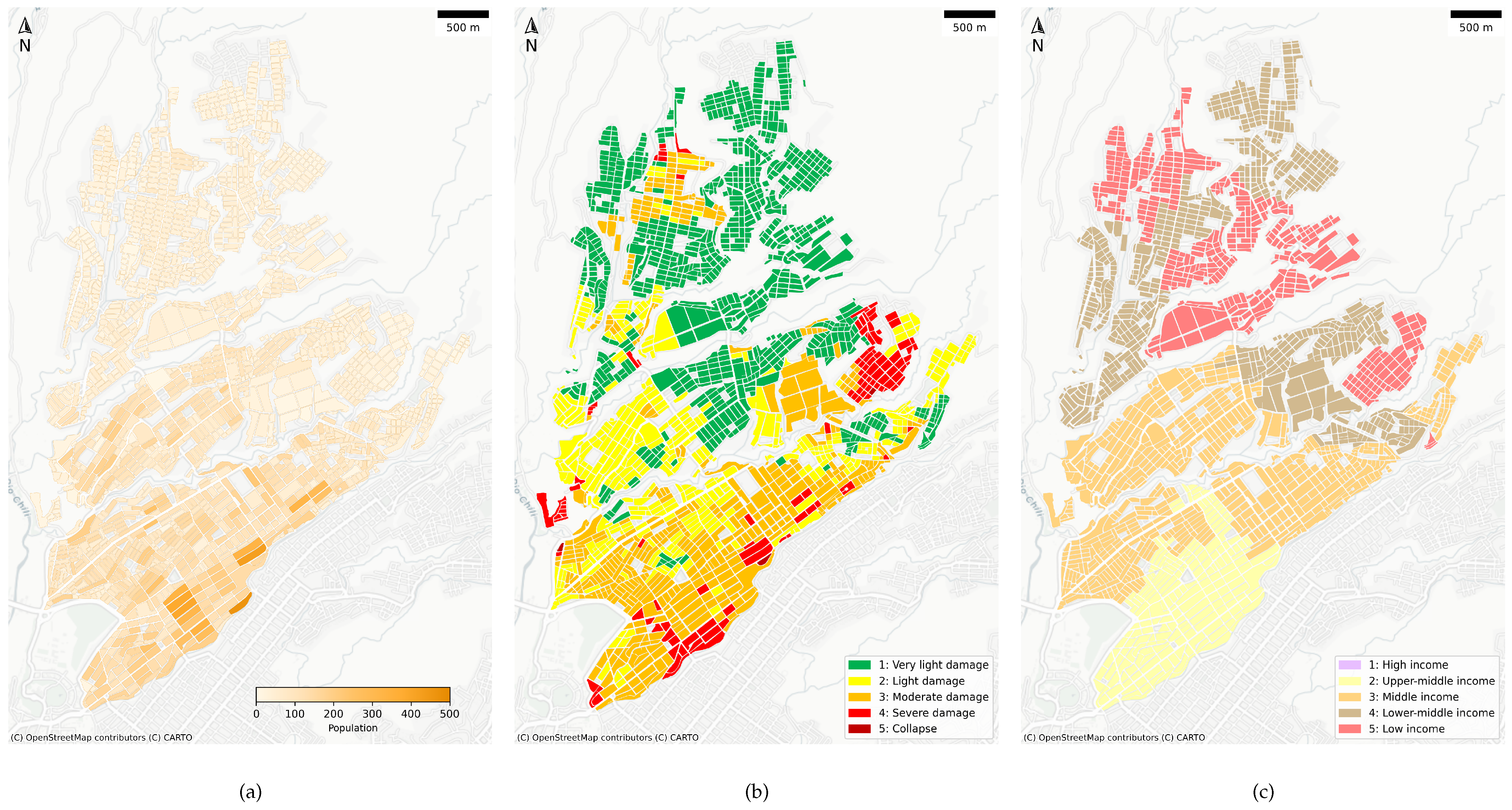

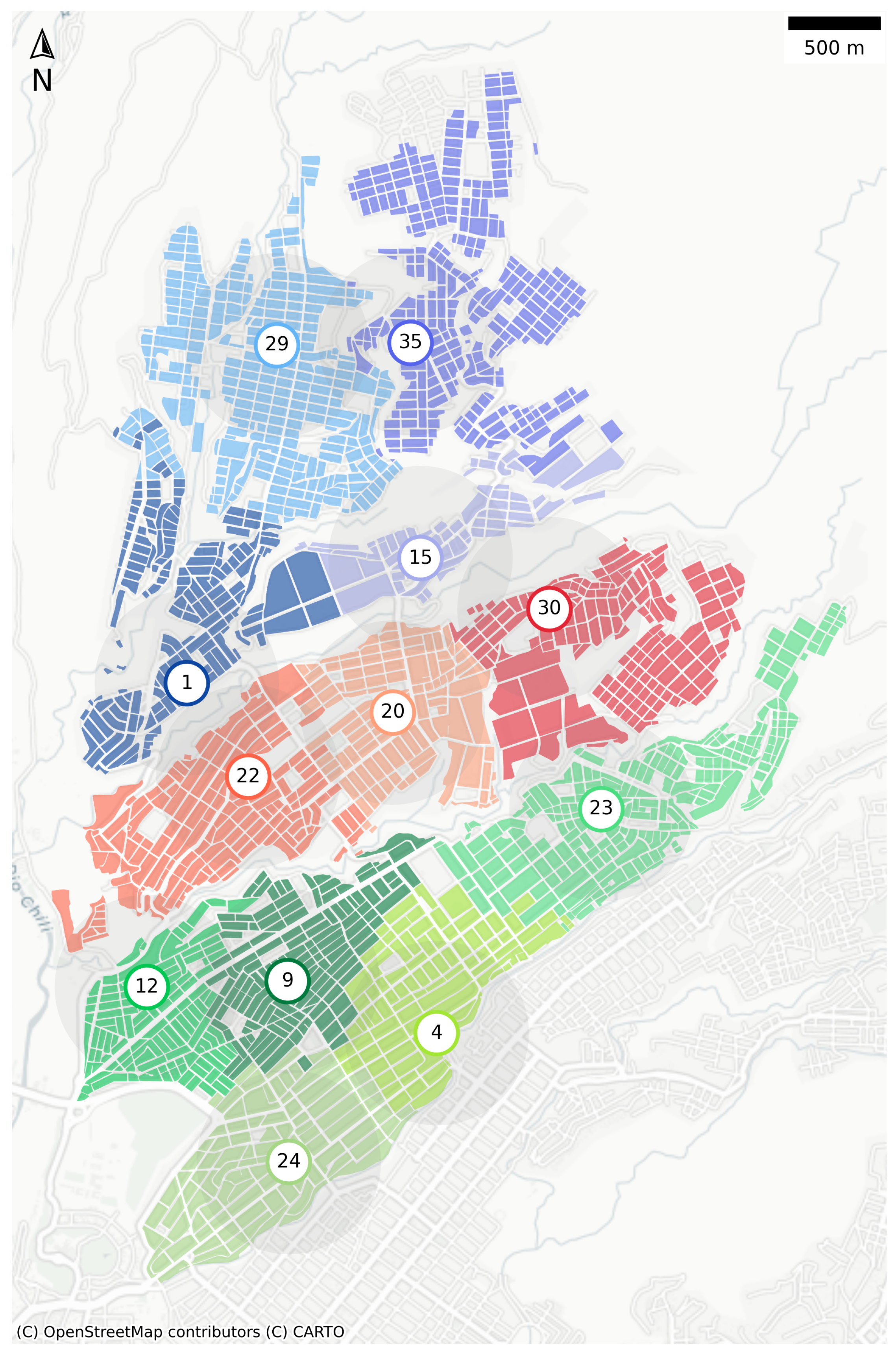

3. Case Study

4. Prioritization Model

4.1. Mathematical Model

4.2. Multi-Criteria Approach

5. Results

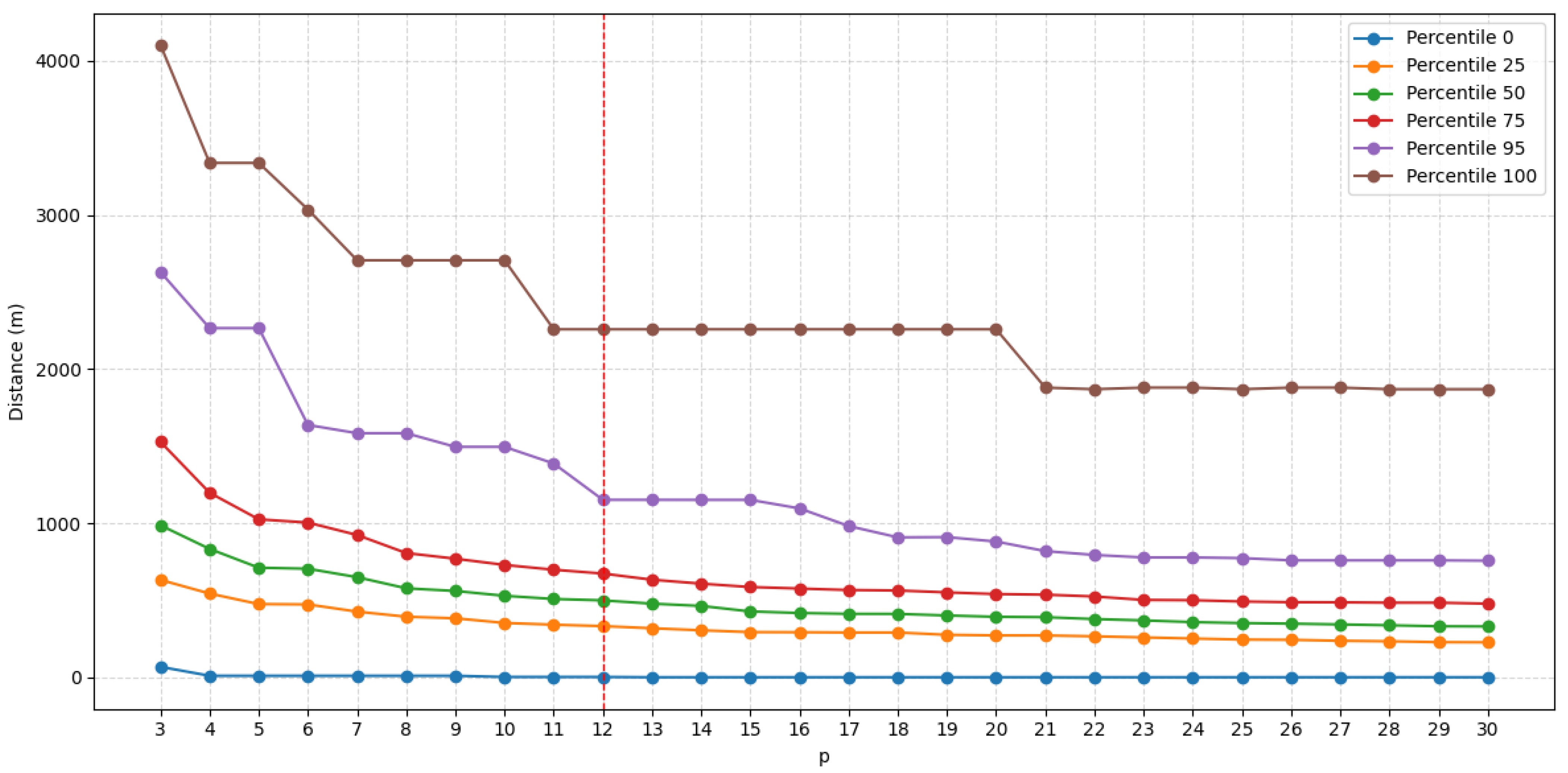

5.1. Mathematical Model

5.2. Multi-Criteria Approach

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shehadeh, K.S.; Tucker, E.L. Stochastic optimization models for location and inventory prepositioning of Disaster Relief Supplies. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 144, 103871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksuz, M.K.; Satoglu, S.I. A two-stage stochastic model for location planning of temporary medical centers for disaster response. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 44, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EM-DAT–Emergency Events Database. Available online: https://public.emdat.be/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Sheu, J.B. Challenges of emergency logistics management. Transp. Res. Part E-Logist. Transp. Rev. 2007, 43, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitoriano, B.; Ortuño, M.T.; Tirado, G.; Montero, J. A multi-criteria optimization model for humanitarian aid distribution. J. Glob. Optim. 2011, 51, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutjahr, W.J.; Fischer, S. Equity and deprivation costs in Humanitarian Logistics. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 270, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotes, N.; Cantillo, V. Including deprivation costs in facility location models for humanitarian relief logistics. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2019, 65, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembro, J.; Kunz, N.; Frennesson, L.; Vega, D. Revisiting the definition of humanitarian logistics. J. Bus. Logist. 2024, 45, e12376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 11: Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable. 2015. Available online: https://globalgoals.org/goals/11-sustainable-cities-and-communities/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Guha-Sapir, D.; Below, R.; Hoyois, P. 2024 EM-DAT Annual Disaster Statistical Review: The Numbers and Trends; Technical report; Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED): Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carnero Quispe, M.F.; Couto, A.S.; de Brito Junior, I.; Cunha, L.R.A.; Siqueira, R.M.; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y. Humanitarian logistics prioritization models: A systematic literature review. Logistics 2024, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, J.; Liberatore, F.; Vitoriano, B. A mathematical pre-disaster model with uncertainty and multiple criteria for facility location and network fortification. Mathematics 2020, 8, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzari, A.; Tarakci, H. A healthcare location-allocation model with an application of telemedicine for an earthquake response phase. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 55, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manopiniwes, W.; Irohara, T. Optimization model for temporary depot problem in flood disaster response. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 1743–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín-Veras, J.; Jaller, M.; Van Wassenhove, L.N.; Pérez, N.; Wachtendorf, T. On the unique features of post-disaster humanitarian logistics. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharmand, H.; Comes, T.; Lauras, M. Bi-objective multi-layer location–allocation model for the immediate aftermath of sudden-onset disasters. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 127, 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnero Quispe, M.F.; Chambilla Mamani, L.D.; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y.; Brito Junior, I.d. Temporary Facility Location Problem in Humanitarian Logistics: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics 2025, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, R.; Nishi, T.; Bagherinejad, J.; Bashiri, M. Multi-period maximal covering location problem with capacitated facilities and modules for natural disaster relief services. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, R.; Shrestha, Y.; Rakhal, B.; Suman, S.; Hulst, J.; Hanaoka, S. Mobile logistics hubs prepositioning for emergency preparedness and response in Nepal. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2020, 10, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. IS-26: Guide to Points of Distribution; FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Loree, N.; Aros-Vera, F. Points of distribution location and inventory management model for Post-Disaster Humanitarian Logistics. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 116, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amideo, A.E.; Scaparra, M.P.; Kotiadis, K. Optimising shelter location and evacuation routing operations: The critical issues. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahtab, Z.; Azeem, A.; Ali, S.M.; Paul, S.K.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M. Multi-objective robust-stochastic optimisation of relief goods distribution under uncertainty: A real-life case study. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2022, 9, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, M.; Mousavi, Z.; Manavizadeh, N. Locating a temporary depot after an earthquake based on robust optimization. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Prod. Res. 2019, 30, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Batta, R.; Rogerson, P.A.; Blatt, A.; Flanigan, M. Location of temporary depots to facilitate relief operations after an earthquake. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2012, 46, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, P.; Khalili-Damghani, K.; Hafezalkotob, A.; Raissi, S. Stochastic optimization model for distribution and evacuation planning (A case study of Tehran earthquake). Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayal, D.; Pradhananga, R.; Pokharel, S.; Mutlu, F. A model for planning locations of temporary distribution facilities for emergency response. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2015, 52, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, P.; Khalili-Damghani, K.; Hafezolkotob, A.; Raissi, S. Uncertain multi-objective multi-commodity multi-period multi-vehicle location-allocation model for earthquake evacuation planning. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 350, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Li, S. Two-Stage Multi-Objective Stochastic Model on Patient Transfer and Relief Distribution in Lockdown Area of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiki, H.; Seyedhosseini, S.M.; Ghezavati, V.R.; Seyedaliakbar, S.M. A location-routing model for assessment of the injured people and relief distribution under uncertainty. Int. J. Eng. Trans. A Basics 2020, 33, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, R.; Hanaoka, S. Fuzzy multi-attribute group decision making to identify the order of establishing temporary logistics hubs during disaster response. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2019, 9, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Tan, J. Location Allocation Collaborative Optimization of Emergency Temporary Distribution Center under Uncertainties. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 6176756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B.; Jabbarzadeh, A.; Ghavamifar, A.; Bell, M. Supply chain design for efficient and effective blood supply in disasters. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloum, M.; nezhad, A.M.A.; Bakhshi, A.; Rabbani, M.; Aghsami, A. An integrated relief pre-positioning, procurement planning, and casualty type’s allocation in a humanitarian supply chain. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2024, 11, 2436193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, J.; Koyuncu, M.; Miç, P. Determining shelter locations in conflict areas by multiobjective modeling: A case study in northern Syria. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 38, 101202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, M. A multi-period ambulance location and allocation problem in the disaster. J. Comb. Optim. 2022, 43, 909–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, J.M.; Pedraza-Martinez, A.J.; Wassenhove, L.N.V. Temporary Hubs for the Global Vehicle Supply Chain in Humanitarian Operations. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2016, 25, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon-Gerbier, E.; Buscher, U. Modular and mobile facility location problems: A systematic review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 173, 108734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, R.; Nishi, T. Hybrid set covering and dynamic modular covering location problem: Application to an emergency humanitarian logistics problem. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksuz, M.K.; Satoglu, S.I. Integrated optimization of facility location, casualty allocation and medical staff planning for post-disaster emergency response. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2023, 14, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami, M.; Izadbakhsh, H.; Khamseh, A.A. Developing an integrated blood supply chain network in disaster conditions considering multi-purpose capabilities. J. Model. Manag. 2024, 19, 1316–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, L.; Yin, Y.; Wang, D.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, T. A two-stage adaptive robust model for designing a reliable blood supply chain network with disruption considerations in disaster situations. Nav. Res. Logist. (NRL) 2025, 72, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geofísico del Perú. El Terremoto de la Región del sur del Perú del 23 de junio de 2001. Available online: https://repositorio.igp.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12816/695 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Centro Peruano-Japones de Investigaciones Sismicas y Mitigacion de Desastres. Estudio de Microzonificación Geotécnica sísmica y Evaluación del Riesgo en Zonas Ubicadas en el Distrito de Alto Selva Alegre-Tomo II: Estudios de Diagnóstico del Riesgo. 2013. Available online: https://sigrid.cenepred.gob.pe/sigridv3/documento/15 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Información, Peru. Estratos de Ingreso per Cápita-Ciudades Principales. 2020. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1744/libro.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Censos Nacionales 2017. Available online: https://censos2017.inei.gob.pe/pubinei/index.asp (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Cavdur, F.; Kose-Kucuk, M.; Sebatli, A. Allocation of temporary disaster response facilities under demand uncertainty: An earthquake case study. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sphere Association. The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response, 4th ed.; Sphere Association: Ginebra, Suiza, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diedrichs, D.R.; Phelps, K.; Isihara, P.A. Quantifying communication effects in disaster response logistics: A multiple network system dynamics model. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2016, 6, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, P.; Wright, G. Decision Analysis for Management Judgment; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. OpenStreetMap. 2025. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 13 February 2025).

| Facility | Category | Name | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stadium | Balcones Canchita Chilina | −16.3628 | −71.5267 |

| 2 | Stadium | Cancha Ampliación Villa Ecológica | −16.3496 | −71.5177 |

| 3 | Stadium | Cancha Romero | −16.3884 | −71.5287 |

| 4 | Stadium | Complejo Deportivo Alto Selva Alegre | −16.3792 | −71.5146 |

| 5 | Stadium | Complejo Deportivo Bella Esperanza | −16.3649 | −71.4997 |

| 6 | Stadium | Complejo Deportivo Roosvelt | −16.3821 | −71.5235 |

| 7 | Stadium | Complejo Deportivo Villa Asunción | −16.3623 | −71.5158 |

| 8 | Stadium | Complejo Pampa Chica | −16.3693 | −71.5284 |

| 9 | Stadium | Complejo Ramiro Prialé | −16.3767 | −71.5218 |

| 10 | Stadium | Complejo Rolando Jauregui | −16.3718 | −71.5146 |

| 11 | Stadium | Padre José Schmidpeter | −16.3761 | −71.5171 |

| 12 | Park | Parque Cruce Chilina | −16.3770 | −71.5287 |

| 13 | Park | Parque de la Juventud | −16.3739 | −71.5169 |

| 14 | Park | Parque del Trabajador | −16.3891 | −71.5265 |

| 15 | Park | Parque El Huarangal | −16.3570 | −71.5153 |

| 16 | Park | Parque Francisco Mostajo | −16.3626 | −71.5195 |

| 17 | Park | Parque La Familia | −16.3655 | −71.5192 |

| 18 | Park | Parque Leones del Misti | −16.3708 | −71.5052 |

| 19 | Park | Parque Los Eucaliptos | −16.3758 | −71.5260 |

| 20 | Park | Parque Los Eucaliptos 2 | −16.3642 | −71.5167 |

| 21 | Park | Parque Municipal | −16.3796 | −71.5205 |

| 22 | Park | Parque Temático | −16.3672 | −71.5237 |

| 23 | Park | Parque Tripartito | −16.3687 | −71.5065 |

| 24 | Church | Parroquia Espíritu Santo | −16.3852 | −71.5218 |

| 25 | Park | Plaza Francisco Mostajo | −16.3639 | −71.5219 |

| 26 | Stadium | Polideportivo Juan Velasco Alvarado | −16.3751 | −71.5222 |

| 27 | School | San José Obrero Circa | −16.3771 | −71.5187 |

| 28 | Other | Plaza de Toros Villa Ecológica | −16.3537 | −71.5231 |

| 29 | School | Cuna Más Villa Ecológica | −16.3470 | −71.5223 |

| 30 | Stadium | Cancha El Mirador de Arequipa | −16.3594 | −71.5091 |

| 31 | Stadium | Losa Deportiva–El Gran Chaparral | −16.3654 | −71.5094 |

| 32 | Stadium | Losa Deportiva–Nueva Villa Ecológica Zona C | −16.3398 | −71.5159 |

| 33 | Stadium | Losa Deportiva–Los Enanitos | −16.3449 | −71.5104 |

| 34 | Stadium | Losa Deportiva APSIL | −16.3523 | −71.5073 |

| 35 | Stadium | Losa Deportiva–Nueva Villa Ecológica Zona B | −16.3469 | −71.5158 |

| 36 | Stadium | Losa Deportiva–El Mirador | −16.3605 | −71.5242 |

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| Sets | |

| I | Set of city blocks (demand points). |

| J | Set of candidate facility locations. |

| Parameters | |

| Population at city block i. | |

| Distance between city block i and facility j (km). | |

| p | Maximum number of facilities to be opened. |

| r | Maximum total number of modules available. |

| c | Capacity of a single module. |

| Decision Variables | |

| Binary variable equal to 1 if demand point i is assigned to facility j; 0 otherwise. | |

| Binary variable equal to 1 if facility j is opened; 0 otherwise. | |

| Integer variable representing the number of modules installed at facility j. | |

| Facility | Coverage | Distance COED | Distance Depot | Population | Operational Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27.38% | 3.77 | 3.33 | 3857 | 0.1774 |

| 4 | 47.12% | 1.15 | 0.71 | 9997 | 0.6421 |

| 9 | 63.51% | 0.89 | 0.52 | 12,994 | 0.8595 |

| 12 | 58.04% | 0.81 | 1.28 | 8988 | 0.6973 |

| 15 | 67.68% | 4.05 | 3.61 | 1999 | 0.4107 |

| 20 | 65.76% | 3.12 | 2.68 | 6992 | 0.5857 |

| 22 | 46.44% | 2.86 | 2.59 | 9741 | 0.5286 |

| 23 | 46.26% | 2.43 | 1.99 | 11,994 | 0.6168 |

| 24 | 48.11% | 0.64 | 0.96 | 12,887 | 0.7426 |

| 29 | 36.22% | 5.34 | 4.90 | 6000 | 0.2114 |

| 30 | 46.62% | 4.16 | 3.72 | 4281 | 0.3097 |

| 35 | 31.68% | 5.98 | 5.54 | 4000 | 0.0866 |

| Fac. | Seismic Vuln. | Economic Vuln. | Children | Adolescents | Elderly | Disabilities | Vulnerability Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.36 | 4.05 | 852 | 365 | 392 | 359 | 0.3536 |

| 4 | 2.93 | 2.25 | 1774 | 848 | 1214 | 1060 | 0.5473 |

| 9 | 2.09 | 2.32 | 2419 | 1116 | 1526 | 1404 | 0.5628 |

| 12 | 2.14 | 2.90 | 1690 | 784 | 1015 | 938 | 0.4932 |

| 15 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 376 | 173 | 231 | 208 | 0.3500 |

| 20 | 1.06 | 3.20 | 1316 | 622 | 756 | 732 | 0.3225 |

| 22 | 1.64 | 3.00 | 1730 | 834 | 1253 | 1071 | 0.4717 |

| 23 | 1.65 | 3.24 | 2362 | 1062 | 1321 | 1235 | 0.5809 |

| 24 | 2.98 | 2.00 | 2202 | 1059 | 1857 | 1367 | 0.6275 |

| 29 | 1.12 | 4.63 | 1329 | 579 | 575 | 604 | 0.4737 |

| 30 | 1.29 | 4.34 | 951 | 412 | 371 | 379 | 0.3904 |

| 35 | 1.00 | 4.37 | 776 | 342 | 487 | 419 | 0.3484 |

| Priority | Facility | Op. | Vuln. | SMART |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24: Parroquia Espíritu Santo | 0.7426 | 0.6275 | 0.6620 |

| 2 | 9: Complejo Ramiro Prialé | 0.8595 | 0.5628 | 0.6518 |

| 3 | 23: Parque Tripartito | 0.6168 | 0.5809 | 0.5917 |

| 4 | 4: Complejo Deportivo Alto Selva Alegre | 0.6421 | 0.5473 | 0.5758 |

| 5 | 12: Parque Cruce Chilina | 0.6973 | 0.4932 | 0.5544 |

| 6 | 22: Parque Temático | 0.5286 | 0.4717 | 0.4888 |

| 7 | 20: Parque Los Eucaliptos 2 | 0.5857 | 0.3225 | 0.4015 |

| 8 | 29: Cuna Más Villa Ecológica | 0.2114 | 0.4737 | 0.3950 |

| 9 | 15: Parque El Huarangal | 0.4107 | 0.3500 | 0.3682 |

| 10 | 30: Cancha El Mirador de Arequipa | 0.3097 | 0.3904 | 0.3662 |

| 11 | 1: Balcones Canchita Chilina | 0.1774 | 0.3536 | 0.3008 |

| 12 | 35: Losa Deportiva – Nueva Villa Ecológica Zona B | 0.0866 | 0.3484 | 0.2699 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carnero Quispe, M.F.; Daza Moscoso, M.A.; Cardenas Medina, J.M.; Polanco Aguilar, A.Y.; de Brito Junior, I.; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y. Prioritization Model for the Location of Temporary Points of Distribution for Disaster Response. Logistics 2025, 9, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9040174

Carnero Quispe MF, Daza Moscoso MA, Cardenas Medina JM, Polanco Aguilar AY, de Brito Junior I, Yoshizaki HTY. Prioritization Model for the Location of Temporary Points of Distribution for Disaster Response. Logistics. 2025; 9(4):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9040174

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarnero Quispe, María Fernanda, Miguel Antonio Daza Moscoso, Jose Manuel Cardenas Medina, Ana Ysabel Polanco Aguilar, Irineu de Brito Junior, and Hugo Tsugunobu Yoshida Yoshizaki. 2025. "Prioritization Model for the Location of Temporary Points of Distribution for Disaster Response" Logistics 9, no. 4: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9040174

APA StyleCarnero Quispe, M. F., Daza Moscoso, M. A., Cardenas Medina, J. M., Polanco Aguilar, A. Y., de Brito Junior, I., & Yoshizaki, H. T. Y. (2025). Prioritization Model for the Location of Temporary Points of Distribution for Disaster Response. Logistics, 9(4), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9040174