Abstract

Astragalus membranaceus is a model of traditional ‘homologous nature of medicine and food’. Its stems and leaves have been proven to have a variety of biological activities. In this study, high-throughput sequencing technology was used to sequence transcriptomics and metabolomics A. membranaceus stems and leaves at different growth stages (flowerless stage, flower bud stage, flowering stage, green fruit stage, mature fruit staged, and withering stage), and a regulation analysis was conducted on its differentially expressed genes and differentially accumulated metabolites. The results showed that five hub genes, PAL, CHI, AMIE, CAD, and PRX, were found to play a central regulatory role in flavonoid biosynthesis. The combined analysis of transcriptomics and metabolomics constructed a flavonoid metabolic regulatory network during the growth and development of A. membranaceus stems and leaves. At the same time, based on the significant antioxidant activity of isoquercitrin, three genes that may be related to isoquercitrin biosynthesis were screened, namely IF7MAT, FG3, and UGT78D2. The results of this study provide insights into the biosynthesis and comprehensive development and utilization of flavonoids in A. membranaceus.

1. Introduction

Astragalus membranaceus is a perennial herb of Leguminosae. Its root (Astragali Radix) is a traditional Chinese bulk medicine with immunomodulatory [1], hypoglycemic [2], anti-inflammatory [3], antioxidant [4], and antiviral activities. It first appeared in China’s earliest pharmaceutical monograph “Shen Nong’s Herbal Classic”, and was listed as the first grade in “three-grade classification” [5]. In addition to secondary metabolites, Astragali Radix is also rich in a variety of trace elements and amino acids, so it is widely used in health food [5], such as instant Astragali Radix [6], biscuits [7], tea drinks [8], condiments [9], yogurt [10], and health wines [11]. Its safety has been verified for a long time, and in 2023, it was officially included in the list of ‘homologous nature of medicine and food’ substances by the relevant departments of the Chinese state. As of early 2024, 1558 Astragali Radix health foods products have been approved [12]. In addition, Astragali Radix have been classified as a legal dietary supplement by the U.S. Dietary Supplements Health and Education Act in 1994 [13]. Given the increasing market demand of Radix Astragali and the lack of wild resources, cultivated products have become the main source of commercial Radix Astragali. As of 2020, the planting area of A. membranaceus in China has exceeded 1.5 million mu [14]. However, the current production enterprise still has the problem of low resource utilization. About 70% of the by-products (such as stems and leaves) have not been used in high value, and nearly 300,000 tons of waste stems and leaves are produced every year. These stem and leaf resources have not been used reasonably and effectively for a long time [15]. In recent years, the potential utilization value of A. membranaceus stems and leaves resources has been gradually explored, such as the development of tea drinks [16], functional foods [17], and other products.

It is worth noting that A. membranaceus stems and leaves are also rich in a variety of bioactive components, especially flavonoids, which have high potential for development and utilization. Flavonoids are a kind of yellow pigment derived from 2-phenylchromone, and their main active structure is a hydroxyl substituent. Flavonoids widely distributed in plants have a variety of biological functions, such as regulating plant growth, protecting plants from UV damage, signal transduction in plant–microbe interactions, and as phytoalexins and active oxygen scavengers. At the same time, flavonoids are also a natural health food additive, which can be used as natural antioxidants [18], sweeteners [19], pigments [20], and food preservatives [21]. Flavonoids have become a hot spot in the development and utilization of natural medicines and health products due to their therapeutic and preventive functions in protecting cardiovascular health, anti-oxidation, inhibiting tumors, and regulating immunity [22]. More than 30 kinds of effective bioactive components of flavonoids exist in A. membranaceus, including flavonoids, isoflavones, and pterostane [23]. Various bioactive components in A. membranaceus have gradually made progress in the fields of beauty and health care. These compounds can improve the immune system, protect against damage due to free radicals, slow down the aging process, prevent oxidation, and fight against bacterial infections [24].

In order to deeply analyze the biosynthesis and regulation mechanism of active ingredients such as flavonoids in A. membranaceus, modern omics techniques such as combined analysis of transcriptomics and metabolomics have become key research methods. The combined analysis of transcriptomics and metabolomics is becoming increasingly and widely used in the biosynthesis of plant flavonoids. Xue et al. used transcriptomic and metabolomic techniques to analyze and clarify that the flower color change of Lonicera japonica Thunb. may be related to the regulation of chlorophyll and carotene [25]. The accumulation of anthocyanin in Asparagus officinalis L. is related to light [26]. Jiang et al. showed that the flesh color of Actinidia arguta (Siebold & Zucc.) Planch. ex Miq. is related to the regulation mechanism of flavonoids [27]. The combined analysis of transcriptomics and metabolomics of Carthamus tinctorius L. at different flowering stages showed that 4CL, DFR, and ANR were up-regulated with the flowering process, while CHI, F3H, and FLS were down-regulated [28].

On the basis of the current development model of the A. membranaceus industry, our previous studies have shown that isoquercitrin has remarkable antioxidant activity in A. membranaceus stems and leaves [29]. Therefore, in this study, A. membranaceus stems and leaves at different growth stages were used as materials, and high-throughput sequencing technology was used to perform transcriptome and metabolomic analysis and joint analysis to clarify the flavonoid biosynthesis regulatory network in the stems and leaves of A. membranaceus and screen the key regulatory genes related to isoquercitrin biosynthesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

A. membranaceus stems and leaves were collected from the experimental base (37°25′17′′ N, 112°34′41′′ E) of the College of Life Sciences of Shanxi Agricultural University in Taigu District, Shanxi Province. The two-year plants with the same growth status were collected at six different stages: flowerless stage (FL: plants before flowering), flower bud stage (FB: 50% of the plants entered the budding stage), flowering stage (F: 50% of the plants entered full-bloom stage), green fruit stage (GF: pod formation and initial development), mature fruit stage (MF: pod filling completed), and withering stage (W: leaves began to turn yellow and fall off). The stems and leaves of the whole plant were collected and mixed at six different growth stages. The samples were collected at three biological replicates in each stage, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

2.2. Widely Targeted Metabolomic Analysis and Annotation

About 50 mg of dried sample powder was added to 1200 μL of pre-cooled 70% methanol aqueous solution for metabolite extraction. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 3 min, and the supernatant was obtained for UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. Electrospray ionization source was used for mass spectrometry analysis, the temperature was 550 °C, and the ion spray voltage was 5500 V/−4500 V (positive/negative ion mode). Ion source gas I (GS I), gas II (GS II), and curtain gas (CUR) were 50, 60, and 25 psi, respectively, and the scanning mode was MRM. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed by the statistical function prcomp in R (www.r-project.org). The variable importance in projection (VIP) value was extracted from the orthogonal projections to latent structures–discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) results, and the score map and permutation map were generated with the R package (version 4.5.1) MetaboAnalystR; the model was the best when p < 0.05. Preliminary screening of differential metabolites was based on OPLS-DA results [30]. The identified metabolites were annotated using the KEGG compound database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/compound/, (accessed on 2 November 2025)), and the annotated metabolites were mapped to the KEGG pathway database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/pathway.html, (accessed on 2 November 2025)). The metabolites that were significantly regulated were mapped to certain pathways and then subjected to metabolite set enrichment analysis (MSEA). The significance of these pathways was determined using p-values obtained from a hypergeometric test.

2.3. Transcriptome Sequencing and Annotation

Total RNA was extracted from A. membranaceus stems and leaves by the Trizol method. The Illumina NEBNext® UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit was used to construct a library with RNA ≥ 1 μg. The library underwent a quality inspection, after which the high-throughput sequencing instrument MGIseq2000 was used. The raw reads were filtered by fastp to obtain high-quality clean reads [31]. The clean reads were spliced by Trinity and de-redundant by corset to obtain the unigene sequence [32,33]. The gene expression was quantified by using bowtie2 in RSEM software [34,35] and evaluated based on the Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped (FPKM) value. FPKM is the ratio of mapped fragments of transcript to the multiplication of total count of mapped fragments (Millions) and length of transcript (kb). Total count of mapped fragments (Millions) is the total number of fragments aligned to the transcripts in 106 units; length of transcript (kb) represents the length of the transcript in 103 bases. TransDecoder (https://github.com/TransDecoder/, (accessed on 2 November 2025)) was used to predict the coding sequence (CDS) of the assembled transcripts. DESeq2 was used for screening differentially expressed genes. DIAMOND BLASTX and HMMER software were used to compare the sequences with the KEGG, NR, Swiss-Prot, GO, KOG, Trembl, and Pfam databases to obtain unigene annotation information [36].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) between sample groups were determined by variable importance in projection (VIP > 1), fold change ≥ 2 or fold change ≤ 0.5, and p < 0.05 as screening conditions. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between sample groups with |log2Fold Change| ≥ 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 as screening conditions [37,38]. The key genes related to isoquercitrin were screened with p-value ≤ 0.05 as the threshold.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Transcriptome Sequencing

A total of 215.52 Gb clean data were obtained by transcriptome sequencing of 18 samples from six stages of A. membranaceus stems and leaves (Supplement Table S1). The clean data of each sample reached 9 Gb, and the percentage of Q30 bases was greater than 91%. After assembly and clustering, 184,121 unigenes were obtained, and a total of 123,960 unigenes were annotated to at least one database. The number of unigenes annotated in the non-redundant (Nr), Translation of EMBL (TrEMBL), Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), SwissPort, eukaryotic orthologous groups (KOG), and Pfarm databases was 120,216, 120,116, 103,395, 91,722, 84,236, 73,095, and 71,674, accounting for 67.32%, 65.24%, 56.16%, 49.82%, 45.75%, 39.7%, and 38.93%, respectively (Supplement Figure S1a). A total of 103,395 unigenes in 32 GO terms were annotated to the GO database, accounting for 56.16% (Supplement Figure S1b). Among the biological process (BP, 15), the number of unigenes annotated by cellular process (GO: 0009987) and metabolic process (GO: 0008152) was the largest at 67,492 and 57,667, respectively. Only protein-containing complex (GO: 0032991) and cellular anatomical entity (GO: 0110165) were annotated in cellular component (CC, 2), and the number of unigenes was 14,265 and 79,698, respectively. In molecular function (MF, 15), binding (GO: 0005488) and catalytic activity (GO: 0003824) were the most abundant at 62,469 and 54,197, respectively. A total of 73,095 unigenes were annotated to 25 categories in the KOG database, accounting for 39.7%. The top three categories were general function prediction only; posttranslational modification; and protein turnover, chaperones, and signal transduction mechanisms; the number of annotated unigenes in these categories was 20,934, 7205, and 6800, respectively, and the proportions were 27.90%, 9.86%, and 9.30%, respectively (Supplement Figure S1c). The PCA results of gene expression based on FPKM value showed that the contribution rates of PC1 and PC2 were 18.87% and 15.17%, respectively (Supplement Figure S1d). Correlation analysis between samples revealed that the correlation coefficients between the three repeated samples in each group were greater than 0.8, indicating that the repeatability within the group was good and the correlation was strong (Supplement Figure S1e).

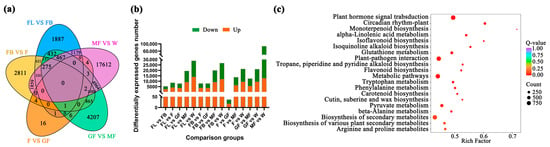

3.2. DEGs Were Identified in Six Stages

With |log2Fold Change| ≥ 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 as the screening conditions, a total of 52,568 DEGs were identified between the sample groups. In the FL vs. FB, FL vs. F, FL vs. GF, FL vs. MF, FL vs. W, FB vs. F, FB vs. GF, FB vs. MF, FB vs. W, F vs. GF, F vs. MF, F vs. W, GF vs. MF, GF vs. W, and MF vs. W comparison groups, the number of up-/down-regulated genes was 2709/2631, 4262/4373, 3888/3995, 9204/10,294, 12,089/14,829, 3943/4060, 3889/4037, 9255/10,749, 12,011/14,733, 18/19, 6365/7368, 9620/11,759, 5648/6819, 9592/11,566, and 12,909/14,864, respectively (Figure 1 and Supplement Table S2). The top 10 KEGG pathways enriched by these DEGs were plant hormone signal transduction, circadian rhythm–plant, monoterpenoid biosynthesis, alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism, isoflavonoid biosynthesis, isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis, glutathione metabolism, plant–pathogen interaction, tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis, and flavonoid biosynthesis (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Number of differential genes between different comparison groups. (a) DEGs between comparison groups; (b) up-/down-regulated DEGs, the green box represents down-regulation, and the orange box represents up-regulation; (c) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs.

3.3. DEGs Analysis of Flavonoid Synthesis in the Stems and Leaves

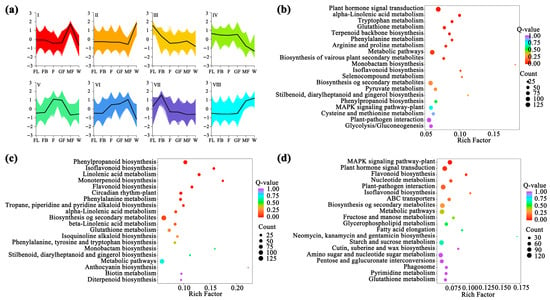

Trend analysis of DEGs in A. membranaceus stems and leaves at six stages revealed eight gene expression patterns, namely Cluster I-VIII (Figure 2a). KEGG functional enrichment analysis was performed on the genes in the eight trends. With Padj ≤ 0.05 as the threshold, the pathway that meets this condition was the pathway that was significantly enriched in the above trend. The results showed that there were three significant enrichment trends (Cluster-IV, Cluster-V, and Cluster-VII) related to flavonoid biosynthesis in different developmental stages of A. membranaceus stems and leaves. Among them, the pathway involved in Cluster-IV was phenylalanine metabolism (Figure 2b); the pathways involved in Cluster-V were phenylalanine biosynthesis, isoflavone biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis, and phenylalanine metabolism (Figure 2c); the pathway involved in Cluster-VII was flavonoid biosynthesis (Figure 2d). There were 36 genes annotated to be involved in flavonoid metabolism in the pathway, which regulated the synthesis of related enzymes in the process of flavonoid metabolism in A. membranaceus stems and leaves (Supplement Table S3).

Figure 2.

Functional enrichment analysis of flavonoid synthesis DEGs. (a) Expression patterns of the eight clusters correspond to the hierarchical cluster result. Eight main clusters are presented as Cluster I–Cluster VIII. Gene expression values are normalized to log10 (FPKM); (b) TOP20 KEGG functional enrichment analysis of Cluster-IV DEGs; (c) TOP20 KEGG functional enrichment analysis of Cluster-V DEGs; (d) TOP20 KEGG functional enrichment analysis of Cluster-VII DEGs.

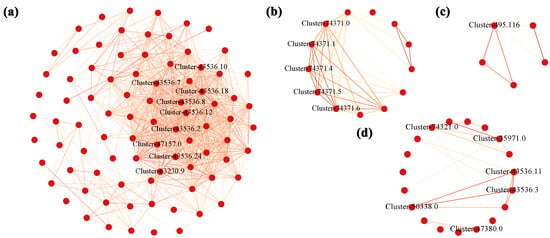

3.4. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network (WGCNA) Analysis of Unigenes

A total of 184,121 genes were identified in A. membranaceus stems and leaves. After removing the genes with low and unstable expression by R language, 36,482 genes were obtained and constructed by weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). The square threshold of the correlation coefficient between genes was set to 0.85; that is, R2 > 0.85, the soft threshold (β, power Estimate) was calculated, and β = 19 was selected as the soft threshold (Figure 3a). The clustering tree was constructed according to the correlation of gene expression levels, and the modules were divided by the number of module genes ≥ 50, and the merging threshold of the modules was set to 0.25, resulting in 32 gene modules (Figure 3b). The number of genes in each module was shown in Supplement Table S4. Perform inter module correlation analysis on 32 modules based on their eigengene, and draw a heatmap (Figure 3c). The darker the color of the square (red or blue), the stronger the correlation. Subsequently, the H-clust method was used to cluster the module genes (Figure 3d), where each tree represents a module, and each branch represents a gene, and the darker the color of each point, the stronger the connectivity between the two genes corresponding to the rows and columns.

Figure 3.

WGCNA analysis. (a) Soft threshold selection; (b) module hierarchical clustering tree; (c) the gene co-expression module of hickory nut; (d) cluster analysis of module gene correlation. The position of the red line is represented as a soft threshold.

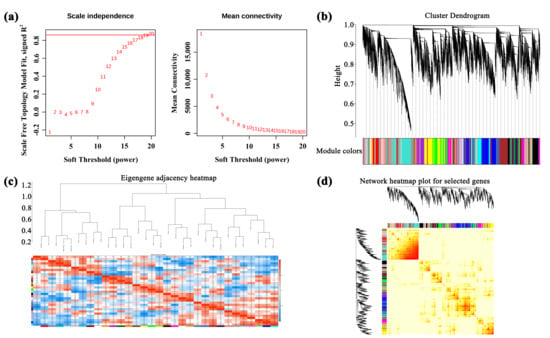

KEGG functional enrichment analysis of the above 32 module genes showed that the modules related to flavonoid biosynthesis process during the development of A. membranaceus stems and leaves were mainly black, cyan, midnightblue, and steelblue modules. Among them, the pathways related to flavonoid biosynthesis in the black module were phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, isoflavone biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis and phenylalanine metabolism; the cyan module was phenylalanine metabolism; the midnightblue and steelblue modules were phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (Figure 4). Supplement Table S5 listed the genes involved in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in four modules.

Figure 4.

TOP20 KEGG functional enrichment analysis of module genes. (a) black module; (b) cyan module; (c) midnightblue module; (d) steelblue module.

The genes enriched in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in the modules of black, cyan, midnightblue, and steelblue were plotted to draw a network regulation map, and the hub gene of flavonoid biosynthesis in the development of A. membranaceus stems and leaves was established. The weight value of each gene was determined by the connectivity of the gene, and the genes with high connectivity may play a pivotal role in the module. Therefore, the top 10% of the average connectivity of a single gene in a significant module was used as hub genes. The results showed that the hub genes closely related to flavonoid biosynthesis in the black module were PAL (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase: Cluster-43536.18, Cluster-43536.2, Cluster-43536.12, Cluster-43536.10, Cluster-43536.7, Cluster-43536.8, Cluster-43536.24, Cluster-47157.0), and CHI (chalcone isomerase: Cluster-63230.9). In the cyan module, it was AMIE (amidase: Cluster-74371.0, Cluster-74371.1, Cluster-74371.4, Cluster-74371.5, Cluster-74371.6). In the midnightblue module, there were CAD (cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase: Cluster-74321.0, Cluster-35971.0), PAL (Cluster-43536.11, Cluster-43536.3, Cluster-50338.0), and PRX (peroxidase: Cluster-47380.0). In the steelblue module, it was PRX (Cluster-495.116) (Figure 5). It can be seen that PAL, CHI, AMIE, CAD, and PRX play a core regulatory role in the flavonoid biosynthesis and are the hub genes of flavonoid biosynthesis during the development of A. membranaceus stems and leaves.

Figure 5.

Gene network regulation relationships in four flavonoid biosynthetic modules. (a) black; (b) cyan; (c) steelblue; (d) midnightblue. The red underline was marked as the hub gene.

3.5. Overview of Sequencing Data and Differential Metabolite Analysis

The mass spectrometry data were processed by Analyst 1.6.1 software. The combined sample’s total ion current (TIC) of the mixed sample and the detection of multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) metabolites’ multiple peaks indicated that the signal for sample analysis signal was robust, the peak capacity was high, and the retention time reproducibility was good (Supplement Figure S2a–d). The integral correction results of quantitative analysis of random metabolites ensured the accuracy of qualitative and quantitative analyses (Supplement Figure S2e–f). The coefficient of variation (CV) and the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) were used to analyze the data distribution. The metabolites with CV values less than 0.3 in quality control (QC) samples accounted for 95.66% of the total metabolites, indicating that the sequencing data were very stable (Supplement Figure S3a). Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) of different sample metabolites showed that the repeatability of samples in six stages was good, and the expression trend of metabolites was basically the same (Supplement Figure S3b). The results of sample correlation analysis are shown in Supplement Figure S3c. All three repeated samples in each group had correlation coefficients more than 0.8, indicating excellent repeatability within the group and a strong correlation. The results of principal component analysis (PCA) are shown in Supplement Figure S3d. PC1 and PC2 accounted for 26.44% and 15.8%, respectively. The distinct separation of the six stages indicated significant differences in the accumulation and expression patterns of metabolites throughout these stages. A total of 944 metabolites were identified in A. membranaceus stems and leaves (Supplement Figure S3e), of which flavonoids were the most abundant, accounting for 39.51%. The composition of the metabolites in the substance was as follows: phenolic acids (16.74%), terpenoids (15.68%), alkaloids (8.47%), lignans and coumarins (6.14%), quinones (2.44%), tannins (0.74%), and other metabolites (10.28%).

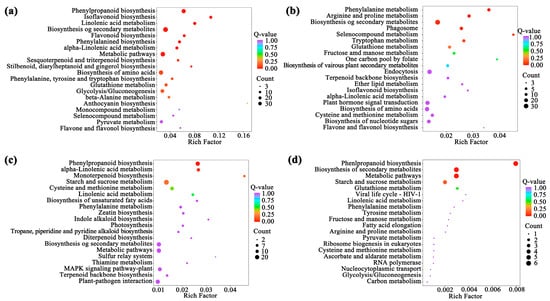

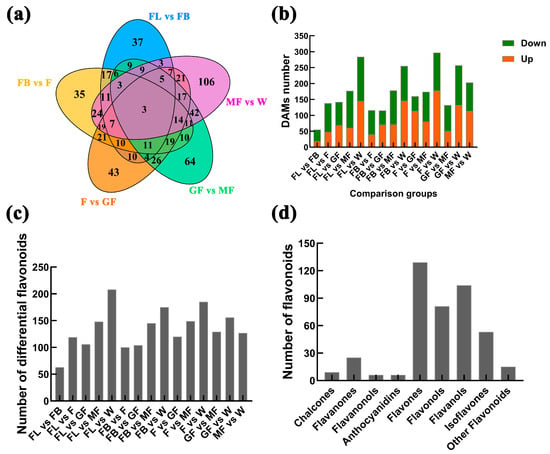

3.6. Differential Metabolites of Flavonoids Were Identified in Six Stages

The OPLS-DA analysis of A. membranaceus stems and leaves in six stages showed that the metabolites were obviously separated. The prediction parameter Q2 of each comparison group in the model verification is greater than 0.5, indicating that the model was effective (Supplement Figures S4 and S5). DAMs between sample groups were determined by variable importance in projection (VIP > 1), fold change ≥ 2 or fold change ≤ 0.5, and p < 0.05 as screening conditions. A total of 770 DAMs were identified in 15 comparison groups (Figure 6a). The up-/down-regulated differential metabolites were 19/36 (FL vs. FB), 48/90 (FL vs. F), 69/73 (FL vs. GF), 61/116 (FL vs. MF), 145/139 (FL vs. W), 40/76 (FB vs. F), 71/44 (FB vs. GF), 72/106 (FB vs. MF), 146/109 (FB vs. W), 114/46 (F vs. GF), 81/93 (F vs. MF), 178/119 (F vs. W), 51/81 (GF vs. MF), 133/124 (GF vs. W), and 114/89 (MF vs. W), as shown in Figure 6b. To clarify the flavonoid biosynthesis regulatory network, we focused on DAMs enriched in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway. A total of 330 differentially accumulated flavonoids were identified in 15 comparison groups, namely, 63 (FL vs. FB), 119 (FL vs. F), 106 (FL vs. GF), 148 (FL vs. MF), 208 (FL vs. W), 100 (FB vs. F), 104 (FB vs. GF), 145 (FB vs. MF), 175 (FB vs. W), 120 (F vs. GF), 149 (F vs. MF), 185 (F vs. W), 129 (GF vs. MF), 156 (GF vs. W), and 127 (MF vs. W), as shown in Figure 6c and Supplement Table S6. The 330 differentially accumulated flavonoids were divided into nine categories of chalcones (9), flavanones (25), flavanonols (6), anthocyanidins (6), flavones (129), flavonols (81), flavanols (6), isoflavones (53), and other flavonoids (15), as shown in Figure 6d.

Figure 6.

Number of DAMs between different comparison groups. (a) DAMs between comparison groups; (b) up-/down-regulated DAMs, the green box represents down, the orange box represents up; (c) number of differentially accumulated flavonoids; (d) classification of differential accumulation flavonoids.

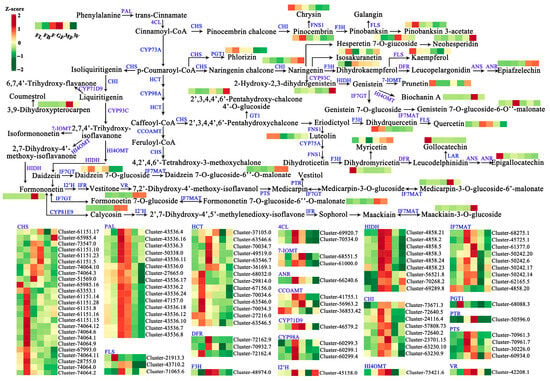

3.7. Analysis of Flavonoid Biosynthesis Pathway

In order to further explore the relationship between DEGs and DEMs involved in flavonoid biosynthesis, this study systematically constructed the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway during the development of A. membranaceus stems and leaves (Figure 7). First, PAL was used as a catalytic enzyme to catalyze the conversion of Phenylalanine to trans-Cinnamate, followed by the conversion to Coumaroyl-CoA under the catalysis of 4CL, and then Coumaroyl-CoA opened two pathways (1–2). (1) Coumaroyl-CoA was converted to Pinocembrin (the largest accumulation in FB stage) under the action of CHS and CHI, and then Pinocembrin opened two pathways (1.1–1.2). (1.1) Pinocembrin was catalyzed by FNS1 to convert into Chrysin (the largest accumulation in FL stage). (1.2) Pinocembrin was catalyzed by F3H to Pinobanksin 3-acetate (the largest accumulation in W stage). (2) Coumaroyl-CoA was converted to p-Coumaroyl-CoA catalyzed by CYP73A, followed by four pathways (2.1–2.4). (2.1) p-Coumaroyl-CoA was converted to Phlorizin (the largest accumulation in FB stage) under the catalysis of CHS and PGT1. (2.2) p-Coumaroyl-CoA was converted to Naringenin (the largest accumulation in W stage) under the action of CHS and CHI, and four pathways were opened at the same time (2.2.1–2.2.4). (2.2.1) Naringenin was successively transformed into Hesperetin 7-O-giucoside (the largest accumulation in GF stage) and Neohesperidin (the largest accumulation in W stage). (2.2.2) Naringenin converted to Isosakuranetin (the largest accumulation in F stage). (2.2.3) Naringenin was transformed into Dihydrokaempferol (the largest accumulation in F stage) under the action of F3H, and two pathways were opened at the same time (2.2.3.1–2.2.3.2). (2.2.3.1) Dihydrokaempferol was converted to Kaempferol (the largest accumulation in FL stage) under the catalysis of FLS. (2.2.3.2) Dihydrokaempferol was converted to Epiafzelechin (the largest accumulation in W stage) under the action of DFR, ANS, and ANR. (2.2.4) Naringenin was converted to 2-Hydroxy-2,3-dihydropistein (the largest accumulation in W stage) under the catalysis of CYP93C, and then converted to Genistein under the catalysis of HIDH, and three pathways were opened (2.2.4.1–2.2.4.3). (2.2.4.1) Genistein was converted to Prunetin (the largest accumulation in FL stage) under the catalysis of 7-IOMT. (2.2.4.2) Genistein was converted to Biochanin A (the largest accumulation in MF stage) under the catalysis of HI4OMT. (2.2.4.3) Genistein was converted to Genistein 7-O-glucoside-6-O’’-malonate (the largest accumulation in F stage) by Genistein 7-O-glucoside catalyzed by IF7GT. (2.3) p-Coumaroyl-CoA was converted to Caffeoyl-CoA under the catalysis of HCT and CYP98A, opening two pathways (2.3.1–2.3.2). (2.3.1) Caffeoyl-CoA was converted to 2′,3,4,4′,6′-Pentahydroxy-chalcone under the catalysis of CHS, and two pathways were simultaneously opened (2.3.1.1–2.3.1.2). (2.3.1.1) 2′,3,4,4′,6′-Pentahydroxy-chalcone was converted to 2′,3,4,4′,6′-Pentahydroxy-chalcone 4′-O-glucoside (the largest accumulation in W stage) under the action of GT1. (2.3.1.2) 2′,3,4,4′,6′-Pentahydroxy-chalcone converted to Eriodictyol, opening two pathways (2.3.1.2.1–2.3.1.2.2). (2.3.1.2.1) Eriodictyol was converted to Dihydrquercetin (the largest accumulation in FL stage) and Quercetin (the largest accumulation in F stage) under the action of F3H and FLS. (2.3.1.2.2) Eriodictyol was converted to Luteolin (the largest accumulation in FB stage) by FNS1, and then converted to Dihydromyricetin (the largest accumulation in FL stage) by CYP75A, FNS1, and F3H, opening two pathways (2.3.1.2.2.1–2.3.1.2.2.2). (2.3.1.2.2.1) Dihydromyricetin converted to Myricetin (the largest accumulation in W stage). (2.3.1.2.2.2) Dihydromyricetin was converted to Leucodelphinidin, opening two pathways (2.3.1.2.2.2.1–2.3.1.2.2.2.2). (2.3.1.2.2.2.1) Leucodelphinidin was converted to Gollocatechin (the largest accumulation in FL stage) under the action of ANR. (2.3.1.2.2.2.2) Leucodelphinidin was converted to Epigallocatechin (the largest accumulation in FL stage) under the action of ANS and ANR. (2.3.2) Caffeoyl-CoA was converted to 4,2′,4,6′-Tetrahdroxy-3-methoxychalone catalyzed by CCOAMT and CHS. (2.4) p-Coumaroyl-CoA was converted to Liquiritigenin under the action of CHS and CHI, opening two pathways (2.4.1–2.4.2). (2.4.1) Liquiritigenin was converted to 6,7,4′-Trihydroxy-flavanone under the action of CYP71D9. (2.4.2) Liquiritigenin was converted to 2,7,4′-Trihydroxy-isoflavanone under the action of CYP93C, and four pathways were opened at the same time (2.4.2.1–2.4.2.4). (2.4.2.1) 2,7,4′-Trihydroxy-isoflavanone converted to 3,9-Dihydroxypterocarpen. (2.4.2.2) 2,7,4′-Trihydroxy-isoflavanone was converted to Isoformononetin (the largest accumulation in MF stage) under the action of 7-IOMT. (2.4.2.3) 2,7,4′-Trihydroxy-isoflavanone was converted to Formononetin (the largest accumulation in MF stage) under the action of HI4OMT and HIDH, opening three pathways (2.4.2.3.1–2.4.2.3.3). (2.4.2.3.1) Formononetin was converted to Medicarpin-3-O-glucoside-6′-malonate (the largest accumulation in MF stage) under the action of I2′H, IFR, VR, PTS, IF7GT, and IF7MAT. (2.4.2.3.2) Formononetin was converted to Formononetin 7-O-glucoside (the largest accumulation in MF stage) under the action of IF7GT, and then converted to Formononetin 7-O-glucoside-6′′ -O-malonate (the largest accumulation in MF stage) under the action of IF7MAT. (2.4.2.3.3) Formononetin was converted to Calycosin (the largest accumulation in MF stage) under the action of CYP81E9, and then finally converted to Maackiain-3-O-glucoside (the largest accumulation in W stage) under the action of I2′H, IFR, and IF7MAT. (2.4.2.4) 2,7,4′-Trihydroxy-isoflavanone was converted to Daidzein under the action of HI4OMT and HIDH, opening two pathways (2.4.2.4.1–2.4.2.4.2). (2.4.2.4.1) Daidzein was converted to Daidzein 7-O-glucoside (the largest accumulation in FB stage) under the action of IF7GT, and then converted to Daidzein 7-O-glucoside-6′′-O-malonate (the largest accumulation in W stage) under the action of IF7MAT. (2.4.2.4.2) Daidzein was converted to Formononetin, opening three pathways (the same as 2.4.2.3.1–2.4.2.3.3). In the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway of A. membranaceus stems and leaves, Medicarpin and Medicarpin-3-O-glucoside, Medicarpin-3-O-glucoside and Medicarpin-3-O-glucoside-6′-malonate, Formononetin and Formononetin 7-O-glucoside, Formononetin 7-O-glucoside and Formononetin 7-O-glucoside-6′′-O-malonate, Formononetin and Calycosin, and Maackiain and Maackiain-3-O-glucoside achieved two-way conversion. The results provided a strong research basis for further exploration of flavonoid metabolism in A. membranaceus stems and leaves.

Figure 7.

The schematic diagram of flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in A. membranaceus stems and leaves. The six columns for each gene and metabolite represent the expression level at FL, FB, F, GF, MF, and W stage, respectively. Red represents the high expression level; green represents the low expression level. PAL: phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; 4CL: 4-coumarate--CoA ligase; CHS: chalcone synthase; CHI: chalcone isomerase; FNS1: flavone synthase I; F3H: naringenin 3-dioxygenase; FLS: flavonol synthase; CYP73A: trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase; PGT1: phlorizin synthase; DFR: bifunctional dihydroflavonol 4-reductase/flavanone 4-reductase; ANS: anthocyanidin synthase; ANR: anthocyanidin reductase; HCT: shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase; CYP98A: 5-O-(4-coumaroyl)-D-quinate 3′-monooxygenase; GT1: chalcone 4′-O-glucosyltransferase; CYP75A: flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase; LAR: leucoanthocyanidin reductase; CCOAMT: caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase; CYP93C: 2-hydroxyisoflavanone synthase; HIDH: 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase; 7-IOMT: isoflavone-7-O-methyltransferase; HI4OMT: 2,7,4′-trihydroxyisoflavanone 4′-O-methyltransferase/isoflavone 4′-O-methyltransferase; IF7GT: isoflavone 7-O-glucosyltransferase; IF7MAT: isoflavone 7-O-glucoside-6′′-O-malonyltransferase; CYP71D9: flavonoid 6-hydroxylase; I2′H: isoflavone/4′-methoxyisoflavone 2′-hydroxylase; IFR: 2′-hydroxyisoflavone reductase; VR: vestitone reductase; PTS: pterocarpan synthase; PTR: pterocarpan reductase; CYP81E9: isoflavone 3′-hydroxylase.

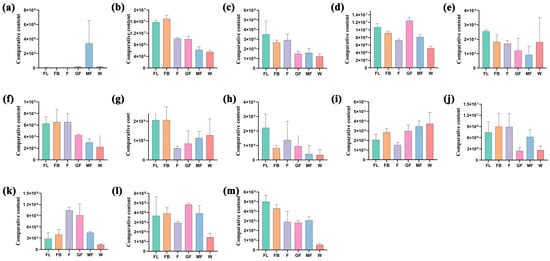

3.8. Screening of Key Genes for Isoquercitrin Biosynthesis

Our previous studies have shown that isoquercitrin contained in A. membranaceus stems and leaves has significant antioxidant activity. Therefore, this study intends to screen key enzyme genes related to isoquercitrin biosynthesis. In flavone and flavonol biosynthesis (ko00944), FL vs. FB, FL vs. F, FL vs. GF, FL vs. MF, FL vs. W, FB vs. F, FB vs. GF, FB vs. MF, FB vs. W, F vs. GF, F vs. MF, F vs. W, GF vs. MF, GF vs. MF, GF vs. MF, and GF vs. W were enriched in 1, 3, 6, 5, 7, 3, 4, 3, 7, 2, 4, 7, 3, 4, and 5 differentially accumulated flavonoids, respectively (Supplement Table S7). The accumulation of 13 differential flavonoids in the synthesis pathway of flavone and flavonols in different stages was shown in Figure 8. The accumulation of cosmosiin, kaempferol, luteolin-7-O-glucuronide, and rutin was the highest in the FL stage; the accumulation of baimaside, kaempferol-3-O-sophorotrioside, luteolin, and nicotiflorin was the highest in the FB stage; the accumulation of quercetin was the highest in the F stage; the accumulation of isoquercitrin and quercetin-3-O-sambubioside was the highest in the GF stage; the accumulation of acacetin and myricetin was the highest in the MF and W stages. Pearson correlation analysis was performed on 13 DEMs and 38 DEGs annotated in the flavonoid and flavonol biosynthesis pathways. The key genes related to isoquercitrin were screened with p-value ≤ 0.05 as the threshold. The results showed that IF7MAT, FG3, and UGT78D2 were closely related to the biosynthesis of isoquercitrin (Table 1).

Figure 8.

Relative content of differentially accumulated flavonoids in flavonoid and flavonol pathways. (a) Acacetin; (b) Baimaside; (c) Cosmosiin; (d) Isoquercitrin; (e) Kaempferol; (f) Kaempferol-3-O-sophorotrioside; (g) Luteolin; (h) Luteolin-7-O-glucuronide; (i) Myricetin; (j) Nicotiflorin; (k) Quercetin; (l) Quercetin-3-O-sambubioside; and (m) Rutin.

Table 1.

Key genes of isoquercitrin biosynthesis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Application of Transcriptome and Metabolome in Mining Key Genes for Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis

Metabolites are the material basis for plants to exert their active effects. The analysis of the biosynthetic pathways of important secondary metabolites and identification of key enzyme genes in the synthetic pathway have become the main contents of the plant’s functional genomics. The combined analysis of transcriptome and metabolome can effectively identify the key genes involved in the biosynthesis pathway of plant secondary metabolites. In the study of sinopoodophyllum hexandrum, 10 key genes in the podophyllotoxin synthesis pathway were identified and synthesized in vitro [39]. In Garland lily, multiple genes involved in colchicine synthesis were screened out [40]. In Glycyrrhiza urulensis, specific expression genes related to isoflavone and glycyrrhizic acid biosynthesis were found [41]. Multi-omics combined research has further promoted the analysis of key enzymes in the biosynthetic pathway of plant active ingredients such as Scutellaria baicalensis and in vitro production [42]. These findings collectively demonstrate that the combination of transcriptomics and metabolomics is a powerful strategy for unraveling the genetic basis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis in plants. In this study, stems and leaves were collected at six stages during the growth and development of A. membranaceus for transcriptome sequencing and metabolomics analysis. A total of 184,121 unigenes were obtained by assembling the transcriptome sequencing results, including 52,568 DEGs. Based on the flavonoid metabolic pathway, the expression pattern and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs were performed. The results showed that 35 genes involved in flavonoid metabolism in A. membranaceus stems and leaves were annotated. The WGCNA and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs and DAMs at different growth stages of Tilia miqueliana Maxim. leaves underscored the link between gene expression and flavonoid levels [43]. In this study, WGCNA analysis of unigenes obtained by transcriptome sequencing showed that PAL, CHI, AMIE, CAD, and PRX played a core regulatory role in flavonoid biosynthesis and were hub genes of flavonoid biosynthesis during the development of A. membranaceus stems and leaves. A total of 944 metabolites were identified by metabolomics analysis, of which flavonoids were the most, accounting for 39.51%.

4.2. Construction of Metabolic Regulation Network of Flavonoids in A. membranaceus Stems and Leaves

Flavonoids, as one of the three major secondary metabolites of plants, can not only regulate their own growth and development but also help resist the adverse external environment. The molecular mechanism of the synthesis and regulation of flavonoids has been a hot topic, and the research reports on the molecular regulation of flavonoids have gradually increased in recent years. The study of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius L. showed that the high expression of the CHS1 gene increased the content of quinone chalcone glycosides by 20–30% and decreased the accumulation of quercetin-3-β-D-glucoside and quercetin by 48% and 63%, respectively [44]. The study of Artemisia annua L. and Ginkgo biloba L. showed that CHS and CHI genes were significantly correlated with the accumulation of flavonoids [45,46]. In addition, the recombinant fusion protein of the flavonol synthase gene FLS in Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. can catalyze dihydroquercetin to produce quercetin [47]. Transcriptome and metabolome analysis on Cinnamomum camphora have identified Cc4CL_1 and Cc4CL_9 acting as robust positive regulators of rutin biosynthesis, contrasting sharply with the strong inhibitory role of CcC4H_1 [48]. At present, the research on flavonoids in A. membranaceus mainly focuses on the biological activity of active compounds, and there are relatively few studies on its biosynthesis, especially stems and leaves. A continuous flavonoid synthesis pathway of ‘Zizhouhuangqi’ was obtained by using transcriptome and metabolome data, and 15 secondary metabolites and 16 enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of flavonoids were annotated [49]. In this study, high-throughput sequencing technology was used to perform transcriptome sequencing and metabolomics analysis at different growth and development stages of A. membranaceus stems and leaves. A total of 32 differentially accumulated flavonoids and 109 differentially accumulated unigenes were annotated in the flavonoid metabolic pathway. At the same time, they were combined and analyzed to construct the flavonoid metabolic regulatory network starting from phenylalanine during the growth and development of A. membranaceus stems and leaves. A branch of the biosynthesis of Calycosin and Biochanin A isoflavones was found downstream of the production of coumaroyl-CoA, which was consistent with the research of Wu et al. [50]. In addition to the Coumaroyl-CoA branch in the downstream pathway of Cinnamoyl-CoA, this study also found the Pinocembrin chalcone branch, which was completed by Pinobanksim 3-acetate. As a downstream pathway of Formononetin, Calycosin, and Formononetin branches have been reported in previous studies [50,51], but this study found another branch, which is completed with Medicarpin-3-O-glucoside-6′-malonate. In the upstream pathway of Formononetin, Daidzein can be further acylated to form Daidzein 7-O-glucoside-6″-O-malonate, confirming the activity of IF7GT and IF7MAT. Interestingly, this study identified Myricetin, Gallocatechin, and Epigallocatechin in the downstream pathway of Luteolin, while Wu et al. found Chrysoerial and its derivatives [50]. It should be noted that in transcriptome analysis, multiple unigenes may be annotated as the same enzyme, mainly because these unigenes belong to different alternatively spliced transcripts and specific gene families [52]. In this study, multiple genes encoding the same enzyme were also identified in the A. membranaceus stems and leaves (Figure 8).

4.3. Biological Activity of Isoquercetin and Excavation of Key Genes for Its Biosynthesis

Isoquercitrin is a flavonol with a molecule of glucose attached to the 3-position of the basic nucleus of flavone. It is almost insoluble in water and easily soluble in organic solvents such as methanol and ethanol [53]. Isoquercitrin has good antioxidant activity and can effectively scavenge DPPH free radicals, superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, and nitrite [54]. Isoquercitrin can reduce the oxidative damage of retinal ganglion caused by hydrogen peroxide and improve the tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to hydrogen peroxide and menadione [55,56]. Isoquercitrin has a protective effect on oxidative damage induced by H2O2 and tert-butyl hydroperoxide, and can reduce Cd2+-induced liver and kidney toxicity [57,58]. In addition, it also exhibits a variety of beneficial activities, such as anti-tumor, anti-bacterial, anti-viral, anti-hypertensive, lipid-lowering, anti-atherosclerosis, hypoglycemic, anti-osteoporosis, and neuroprotection [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

Our previous studies have shown that isoquercitrin contained in A. membranaceus stems and leaves has significant antioxidant activity [29]. Wang et al. also isolated the flavonoids from A. membranaceus leaves by preparative high-performance liquid chromatography [68]. In this study, the transcriptome and metabolome of 18 samples from six stages were sequenced and analyzed. The results showed that three genes that may be related to isoquercitrin biosynthesis were screened, namely IF7MAT, FG3, and UGT78D2. In plants, flavonoids exist in a variety of modified forms such as hydroxylation, methylation, acylation, and glycosylation, among which glycosylated flavonoids are the most common natural compounds. Glycosylation is mainly catalyzed by glycosyltransferases, and flavonoid C-glycosides and O-glycosides are both catalyzed by uridine diphosphate-sugar-dependent glycosyltransferases (UGTs) [69]. Xu et al. research showed that the decrease of IF7MAT expression after hydrogen treatment of germinated soybean under UV-B radiation promoted the conversion of soybean isoflavone glycosides to aglycones [70]. Wu’s study also identified the expression of the IF7MAT gene in A. membranaceus stems and leaves [50]. Glycosylation is often the final step in flavonoid biosynthesis and is catalyzed by the family 1 glycosyltransferases referred to as UDP glycosyltransferases (UGTs) that transfer a glycosyl moiety from UDP sugars to a wide range of acceptors including flavonoids [71]. Flavonoid glycoside glycosyltransferases (FGGs) attach additional sugars to an existing sugar moiety of flavonol glycosides (FGs), resulting in a wide variety of binding positions and sugar combinations [72]. The function of these key genes will be identified in our future work.

5. Conclusions

In this study, widely targeted metabolomics and transcriptomics techniques were used to analyze the six different growth stages of A. membranaceus stems and leaves. A total of 52,568 DEGs and 944 DAMs were identified. The WGCNA analysis of unigenes identified five hub genes, namely PAL, CHI, AMIE, CAD, and PRX, which play a core regulatory role in flavonoid biosynthesis in A. membranaceus stems and leaves. At the same time, the combined analysis of transcriptomics and metabolomics constructed a flavonoid metabolic regulatory network during the growth and development of A. membranaceus stems and leaves. Three genes, IF7MAT, FG3, and UGT78D2, which may be related to isoquercitrin biosynthesis, were screened. The results provide a theoretical basis for the biosynthesis and molecular breeding of flavonoids in A. membranaceus.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/foods15020218/s1, Figure S1: Transcriptome analysis at different developmental stages; Figure S2: TIC analysis of mixed sample mass spectrum, MRM detection of metabolites, and integral correction of quantitative analysis of some metabolites; Figure S3: The CV value distribution map, clustering heat-map, correlation diagram, PCA plot, and metabolite class composition in this study; Figure S4: OPLS-DA analysis of different groups of A. membranaceus stems and leaves; Figure S5: OPLS-DA model validation; Table S1: Transcriptome sequencing results of A. membranaceus stems and leaves; Table S2: The transcriptome data of A. membranous stems and leaves during the six development stages; Table S3: Genes involved in flavonoid synthesis during fruit development of A. membranaceus; Table S4: Statistical table of gene modules in A. membranaceus stem and leaf samples; Table S5: Gene Set in four modules that participate in flavonoid biosynthesis; Table S6: Differentially accumulated flavonoid compounds in 15 comparison groups; Table S7: Differentially accumulated flavonoid compounds in flavone and flavonol biosynthesis.

Author Contributions

L.C.: Data curation, visualization, writing–original draft, funding acquisition; J.Y.: software, visualization; R.Y.: resources, investigation; S.W.: resources, investigation; Z.M.: data curation, software; D.W.: supervision, writing–review and editing. Y.N.: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA, grant number CARS-21; Shanxi Agricultural University’s project of “Introducing Talents for Scientific Research Launch”, grant number 2023BQ132; Doctoral graduates, post-doctoral researchers to work in Shanxi research projects, grant number SXBYKY2024026; and Applied research basic plan of Shanxi province, grant number 202503021212168.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information repository, [ACCESSION NUMBER: PRJNA1182064, https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1182064?reviewer=ka3q61l14ncsa9t4v2u3pn7rf (accessed on 2 November 2025)].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 4CL | 4-coumarate--CoA ligase |

| 7-IOMT | isoflavone-7-O-methyltransferase |

| AAT | aspartate-prephenate aminotransferase |

| AMIE | amidase |

| ANR | anthocyanidin reductase |

| ANS | anthocyanidin synthase |

| AOC3 | primary-amine oxidase |

| CAD | cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase |

| CC | Cellular component |

| CCOAMT | caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase |

| CCR | cinnamoyl-CoA reductase |

| CDS | Coding sequence |

| CHI | chalcone isomerase |

| CHR | chalcone reductase |

| CHS | chalcone synthase |

| COMT | caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase |

| CSE | caffeoylshikimate esterase |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| CYP450 | cytochromeP450 |

| CYP71D9 | flavonoid 6-hydroxylase |

| CYP73A | trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase |

| CYP75A | flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase |

| CYP81E9 | isoflavone 3′-hydroxylase |

| CYP93C | 2-hydroxyisoflavanone synthase |

| CYP98A | 5-O-(4-coumaroyl)-D-quinate 3′-monooxygenase |

| DAMs | Differentially accumulated metabolites |

| DDC | aromatic-L-amino-acid |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| DFR | flavanone 4-reductase |

| DPPH | 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical 2,2-Diphenyl-1-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)hydrazyl |

| ECDF | Empirical cumulative distribution function |

| F | Flowering stage |

| F3H | naringenin 3-dioxygenase |

| F5H | ferulate-5-hydroxylase |

| FB | Flower bud stage |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| FL | Flowerless stage |

| FLS | flavonol synthase |

| FNS1 | flavone synthase I |

| FG3 | flavonol-3-O-glucoside/galactoside glucosyltransferase |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped |

| GF | Green fruit stage |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HCA | Hierarchical cluster analysis |

| HCT | shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase |

| HI4OMT | isoflavone 4′-O-methyltransferase |

| HIDH | 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase |

| HPPD | 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase |

| HPPR | hydroxyphenylpyruvate reductase |

| I2′H | isoflavone/4′-methoxyisoflavone 2′-hydroxylase |

| IF7GT | isoflavone 7-O-glucosyltransferase |

| IF7MAT | isoflavone 7-O-glucoside-6″-O-malonyltransferase |

| IFR | isoflavone reductase |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KOG | EuKaryotic Orthologous Groups |

| MF | Mature fruit stage |

| MF | Molecular function |

| MIF | phenylpyruvate tautomerase |

| MRM | Multiple reaction monitoring |

| MSEA | Metabolite set enrichment analysis |

| NR | Non-Redundant |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal projections to latent structures-discriminant analysis |

| PAL | phenylalanine ammonia-lyase |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PDH | phenylalanine dehydrogenas |

| PGT1 | phlorizin synthase |

| PRX | peroxidase |

| PTR | pterocarpan reductase |

| PTS | pterocarpan synthase |

| QC | Quality control |

| REF1 | coniferyl-aldehyde dehydrogenase |

| TAT | tyrosine aminotransferase |

| TF | Transcription factor |

| TIC | Total ion current |

| BP | Biological process |

| TrEMBL | Translation of EMBL |

| UGTs | Uridine diphosphate-sugar-dependent glycosyltransferases |

| UGT78D2 | flavonol 3-O-glucosyltransferase |

| VIP | Variable importance in projection |

| VR | vestitone reductase |

| W | Withering stage |

| WGCNA | weighted gene co-expression network analysis |

References

- Bedir, E.; Pugh, N.; Calis, I.; Pasco, D.S.; Khan, I.A. Immunostimulatory effects of cycloartane-type triterpene glycosides from Astragalus species. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 23, 834–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Chen, C.; Fu, X. Hypoglycemic activity in vitro and vivo of a water-soluble polysaccharide from Astragalus membranaceus. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 11210–11222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.M.; Jiang, N.; Zheng, J.P.; Hu, H.M.; Yang, H.B.; Lin, A.Z.; Hu, B.F.; Liu, H.T. Structural characterization and anti-inflammatory activity of polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSheng, Z.L.; Jiang, Y.M.; Liu, J.M.; Yang, B. UHPLC–MS/MS analysis on flavonoids composition in Astragalus membranaceus and their antioxidant activity. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.L.; Li, A.P.; Wang, G.H.; Qin, X.M.; Liu, Y.T. Metabolomics analysis of Astragali Radix in Shanxi Province: Investigating the impact of various cultivation methods and growth years on metabolite profiles. Food Chem. 2025, 468, 142492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Q.; Dai, X.X.; Sheng, M.K.; Shi, Y.S.; Peng, X.H.; Cen, S.; Shi, X.Y. Preparation and physical property research on Astragalus polysaccharide gummy confections. Food Nutr. China 2023, 29, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, X.; Cao, J.Q.; Zhang, X.R. Preparation of Astragalus membranaceus–cranberry biscuits and the evaluation of physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 3134–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.N.; Guo, X.Q.; Li, M.Z.; Yang, M.M.; Xu, L.F.; Wang, F.; Cai, Y.G. Evaluation of anti-fatigue action of compound preparations based on the principle of medicine and food homology. Acta Nutr. Sin. 2022, 44, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, M.; Zhao, H.S.; Hu, W.W.; Wang, R.F. Comparison of volatile components between Astragalus vinegar and shanxi mature vinegar. Acta Nutr. Sin. 2020, 45, 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. Study on optimization of Astragalus healthy yoghurt technology by response surface method. Food Eng. 2019, 3, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.S.; Yan, B.S.; Wang, X.Y.; Yan, J.N.; Hu, J.Y. Brewing and technological optimization of Astragalus membranaceus and Lycium barbarum beer. J. Suzhou Univ. 2023, 38, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.J.; Gao, F.; Yang, Q.Q.; Fang, M.; Wang, R.Q.; Wu, G.T. Analysis on the application status of edible and medicinal substances Astragalus membranaceus in functional food in China. Mod. Food 2024, 30, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Liu, H.K.; Hsiao, P.C.; Kuo, L.M.Y.; Lee, I.J.; Wu, T.S.; Chiou, W.F.; Kuo, Y.H. New Isoflavonoid glycosides and related constituents from Astragali Radix (Astragalus membranaceus) and their inhibitory activity on nitric oxide production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Q.; Zhang, X.B. National Statistical Report of Chinese Herbal Medicine Production; Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.A. Resources Utilization of Chinese Herbal Medicine Wastes; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Y.; Lin, X.Y.; Wang, A.Y.; Ran, X.H.; Zhao, H.P.; Dai, Z.X.; Qin, J. A Preparation Method of Astragalus membranaceus Leaf Tea. Patent CN110810576A, 21 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, J.H.; Cui, Y.; Ma, D.Z.; Zhang, K.Y.; Liu, J.C. Evaluation of acute oral toxicity, genetic toxicity, and subchronic of Astragalus stem and leaf. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 37, 332. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.M.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, Y.W.; Yang, Y.M.; Da, H.R.; Hwang, S.J.; Lee, J.R.; Sang, C.K.; Sang, G.K. Inhibition of liver Xreceptor-α-dependent hepatic steatosis by isoliquiritigenin, a licorice antioxidant flavonoid, as mediated by JNK1inhibition. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.; Song, Y.G.; Yang, B. Pharmacological action of flavonoids and its application in food industry. Jiangxi Food Ind. 2007, 3, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Study on the antioxidant activity of natural pigment. Food Sci. 2003, 6, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.H.; Jia, S.J.; Hao, T.J.; Jing, C.; Sun, K.X.; Li, D.H. The Study of physiologic function and application in food on the Licorice flavonoids compounds. For. By-Prod. Spec. China 2016, 3, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, S.N.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.T. Progress on extraction and determination methods of flavonoids in Flos Lonicerae. Food Res. Dev. 2015, 36, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Xu, F.; Liang, J.; Shang, M.Y.; Wang, X.; Cai, S.Q. Isoflavonoids from roots of Astragalus membranaceus var. Mongholicus. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2012, 37, 3243–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, J.; Ma, W. Application and prospect of traditional Chinese medicine Astragalus on medical cosmetology. Chin. J. Aesthetic Med. 2017, 26, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Fan, H.; Yao, F.; Cao, X.X.; Liu, M.M.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.J. Transcriptomics and targeted metabolomics profilings for elucidation of pigmentation in Lonicera japonica flowers at different developmental stages. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 111981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.T.; Han, R.P.; Yu, J.W.; Zhu, M.K.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Li, Z.Y. Anthocyanins accumulation and molecular analysis of correlated genes by metabolome and transcriptome in green and purple asparaguses (Asparagus officinalis L.). Food Chem. 2019, 271, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, M.D.; Wen, C.X.; Xie, X.L.; Tian, W.; Wen, S.Q.; Lu, R.K.; Liu, L.D. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis of the anthocyanin regulatory networks in Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge. Flowers. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.L.; Ahmad, N.; Meng, W.J.; Zhao, S.Y.; Chang, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, M.; Yao, N.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, J. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics provide key molecular insights into floral stage-driven flavonoid pathway in Safflower. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.Y.; Ma, Z.N.; Wang, D.F.; Niu, Y.B. Ultrasound-assisted extraction, optimization, isolation, and antioxidant activity analysis of flavonoids from Astragalus membranaceus stems and leaves. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 10, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, B.; Powers, R. PCA as a practical indicator of OPLSDA model reliability. Curr. Metab. 2016, 4, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.F.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.R.; Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 1884–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.M.; Oshlack, A. Corset: Enabling differential gene expression analysis for de novo assembled transcriptomes. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.D.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, C.N.; Li, B. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from rna-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huson, D.H.; Buchfink, B. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varet, H.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Coppée, J.Y.; Dillies, M.A. SARTools: A DESeq2- and EdgeR-based r pipeline for comprehensive differential analysis of RNA-seq data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, L.; Elizabeth, S.S. Six enzymes from mayapple that complete the biosynthetic pathway to the etoposide aglycone. Science 2015, 349, 1224–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, R.S.; Lau, W.; Sattely, E.S. Discovery and engineering of colchicine alkaloid biosynthesis. Nature 2020, 584, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramilowski, J.A.; Sawai, S.; Seki, H.; Mochida, K.; Yoshida, T.; Sakurai, T.; Muranaka, T.; Saito, K.; Daub, C.O. Glycyrrhiza uralensis transcriptome landscape and study of phytochemicals. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.R.; Xu, Z.C.; Pu, X.D.; Song, J.Y. Research progress in biosynthesis and synthetic biology of active ingredients of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi based on multi-omics approach. Sci. Sin. Vitae 2021, 51, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.J.; Shen, Y.B. Integrative transcriptomics and metabolomics reveal the biosynthesis of flavonoid metabolites in Tilia miqueliana Maxim. leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1642949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.D.; Xue, Y.R.; Li, D.Q.; Song, Q.J.; Zhang, J.J.; Li, D.H.; Wu, H.W.; Li, Y.F. Overexpression of Ct CHS1 increases accumulation of quinochalcone in safflower. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Li, L.L.; Cheng, S.Y.; Cao, F.L.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.H. Molecular cloning and function assay of a chalcone isomerase gene (GbCHI) from Ginkgo biloba. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilshad, E.; Zafar, S.; Ismail, H.; Waheed, M.T.; Cusido, R.M.; Palazon, J.; Mirza, B. Effect of Rol genes on polyphenols biosynthesis in Artemisia annua and their effect on antioxidant and cytotoxic potential of the plant. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 179, 1456–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.J.; Wang, T.; Guo, Q.S.; Zhang, W.Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.H.; Xiao, Y.M. Prokaryotic expression and in vitro enzyme activity analysis of flavonol synthase in Chrysanthemum morifolium cv. ‘Hangju’. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2018, 43, 3471–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.P.; Yang, X.N.; Yang, Z.R. Integration of transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals the genes and pathways regulating flavonoids biosynthesis in Cinnamomum camphora. BMC Genom. Data 2025, 26, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.L.; Liu, L.Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, Y.L.; Zhan, Z.L.; Li, H.Z. Analysis of flavonoids synthesis pathway in Astragalus membranaceus root of ‘Zizhou’ based on transcriptome and metabolome. Mol. Plant Breed. 2025, 4, 1–16. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/46.1068.s.20250417.1448.002.html (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Wu, X.T.; Li, X.T.; Wang, W.; Shan, Y.H.; Wang, C.T.; Zhu, M.L.; La, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Nan, P.; et al. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics study of traditional herb Astragalus membranaceus Bge. var. Mongolicus (Bge.) Hsiao reveals global metabolic profile and novel phytochemical ingredients. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.T.; Xu, Y.Q.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Y.X.; Chen, J.K.; Li, X.; Nan, P. Global transcriptome analysis profiles metabolic pathways in traditional herb Astragalus membranaceus Bge. var. Mongolicus (Bge.) Hsiao. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, H.X.; Zeng, Y. A geraniol-synthase gene from Cinnamomum tenuipilum. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhan, Y.J.; Li, C.Y.; Xu, F.; Zhao, J. Research progress in biological activity of isoquercitrin. Mod. Chin. Med. 2018, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Ahmad, N.; Naqvi, A.A.; Exarchou, V.; Upadhyay, A.; Tuenter, E.; Foubert, K.; Apers, S.; Hermans, N.; Pieters, L. Antioxidant and antiglycating constituents from leaves of Ziziphus oxyphylla and Cedrela serrata. Antioxidants 2016, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.H.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, E.H.; Osborne, N.N. Isoquercitrin is the most effective antioxidant in the plant Thuja orientalis and able to counteract oxidative-induced damage to a transformed cell line (GGC-5 cells). Neurochem. Int. 2010, 57, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.G.; Raulino, R.J.; Cerqueira, D.M.; Mannarino, S.C.; Pereira, M.D.; Panek, A.D.; Silva, J.F.; Menezes, F.S.; Eleutherio, E.C. In vitro and in vivo determination of anti-oxidant activity and mode of action of isoquercitrin and Hyptis fasciculata. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentova, K.; Sima, P.; Rybkova, Z.; Krizan, J.; Malachova, K.; Kren, V. (Anti) mutagenic and immunomodulatory properties of quercetin glycosides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 96, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.J.; Yuan, C.; Dong, C.; Shuang, S.M.; Choi, M.M.F. In vivo antioxidative effect of isoquercitrin on cadmium-induced oxidative damage to mouse liver and kidney. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2011, 383, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orfali, G.D.; Duarte, A.C.; Bonadio, V.; Martinez, N.P.; Araujo, M.E.M.B.; Priviero, F.B.M.; Carvalho, P.O.; Priolli, D.G. Review of anticancer mechanisms of isoquercitin. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 7, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracanna, M.I.; Fortuna, A.M.; Cardenas, A.V.C.; Marr, A.K.; McMaster, W.R.; Anaximandro, G.V.; Eugenio, S.A.; Hernandez, L.R.; Bach, H. Anti-leishmanial, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities of phenolic derivatives from Tibouchina paratropica. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, M.; Kim, Y.; Desper, J.; Chang, K.O.; Hua, D.H. Synthesis and antiviral activity of substituted quercetins. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, A.G.; Prando, T.B.L.; Leme, T.D.S.V.; Gasparotto, F.M.; Lourenco, E.L.B.; Rattmann, Y.D.; Silva-Santos, J.E.D.; Kassuya, C.A.L.; Marques, M.C.A. Mechanisms underlying the diuretic effects of Tropaeolum majus L. extracts and its main component isoquercitrin. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon-Loodu, S.; Ziaullah, Z.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Wang, Y.W.; Kulka, M.; Shahidi, F. Novel quercetin-3-O-glucoside eico-sapentaenoic acid ester ameliorates inflammation and hyperlipidemia. Inflammopharmacology 2015, 23, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimu, R.; Fan, Z.Z.; Wang, X.L.; Hu, J.P.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.H. Anti-platelet aggregation activities of different fractions in leaves of Apocynum venetum L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 168, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuwamongkolwiwat, P.; Hira, T.; Hara, H. A nondigestible saccharide, fructooligosaccharide, increases the promotive effect of a flavonoid, α-glucosyl-isoquercitrin, on glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) secretion in rat intestine and enteroendocrine cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1581–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Schroder, H.C.; Feng, Q.L.; Diehl-Seifert, B.; Grebenjuk, V.A.; Müller, W.E.G. Isoquercitrin and polyphosphate co-enhance mineralization of human osteoblast-like Sa OS-2 cells via separate activation of two RUNX2 cofactors AFT6 and Ets1. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 89, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzolo, G.; Horvath, P.; Zenobi-Wong, M. The flavonoid isoquercitrin promotes neurite elongation by reducing Rho A activity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.B.; Zhu, W.B.; Chen, Y.J.; Yu, J.L.; Ma, Z.P.; Wu, G.S.; Yang, B.Y.; Kuang, H.X. Flavonoids from the leaves of Astragalus membranaceus. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 2017, 39, 1634–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.F.; Su, Y.L.; Chen, N.Z.; Shen, S.H. Genome-wide analysis of the UGT gene family and identification of flavonoids in Broussonetia papyrifera. Molecules 2021, 26, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.L.; Li, M.; Li, W.X.; Liu, H.Y.; Xu, X.X.; Yang, T.B.; Ma, M. Effect of H2 treatment under UV-B irradiation on the enrichment of germinated soybean isoflavones and mechanisms based on growth state, antioxidant system, and metabolomics. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 195, 115821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Hanada, K. An evolutionary view of functional diversity in family 1 glycosyltransferases. Plant J. 2011, 66, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas, F.R.; Di, S.K.; Murai, Y.; Iwashina, T.; Sugawara, S.; Mori, T.; Nakabayashi, R.; Keiko, Y.S.; Saito, K.; Takahashi, R. Cloning and characterization of soybean gene Fg1 encoding flavonol 3-O-glucoside/galactoside (1→6) glucosyltransferase. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 92, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.