Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) for different rice aroma types using sensory evaluation, headspace solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS), and gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) techniques, and to explore the material basis for the flavor differences. Based on the sensory evaluation results, rice aroma was categorized into three types, distinguished by their unique aroma compounds. Type A was characterized by a prominent sweet, popcorn aroma, type B by a more prominent cereal and starchy flavor, and type C by a more complex aroma. Untargeted metabolomics analysis using HS-SPME-GC-MS identified and characterized 74 volatile compounds. A comparison of A versus B versus C revealed 8 key aroma compounds, primarily alkanes, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, and heterocyclic compounds. (E)-2-Octenal, 6-Undecanone, 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole, and P-menthan-1-ol in type A gave it a better sweet aroma, Dodecane, 2,6,10-trimethyl-, 1-Octen-3-one, and 2-Methyldecane in type B gave it a better starchy and cereal flavor. 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole, Heptacosane, and 1-Propanol in type C contributed to a complex aroma. GC-IMS analysis showed that the fingerprints of rice with different aroma types were significantly different. The VOCs of aroma type A contained (+)-limonene, 2-methylpyrazine, 2-pentanone, ethyl butanoate, n-pentanal, styrene, 1-butanol, 3-methyl-, acetate, 1-hexanal, 1-pentanol, and 2-heptanone, which gave it a better sweet aroma. The VOCs of aroma type C contained 1-octen-3-ol, 2,6-dimethyl pyrazine, 2-acetylpyridine, and ethyl hexanoate, which gave it a better complex aroma.

1. Introduction

Rice, one of the major food crops in the world today, serves as the primary food source for more than half the world’s population, particularly in Asia and Africa [1,2]. Rice, domesticated by the Chinese between 13,500 and 8200 years ago [3,4], is now a staple crop worldwide [5]. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization reports that rice production is expected to reach a record high of 555.5 million tons (converted into refined rice) in the 2025/26 fiscal year [6]. Changes in the consumer market and advancements in rice breeding have made the flavor of rice a critical indicator of its market price and consumer acceptance. Therefore, the study of rice flavor is particularly important.

Current rice flavor research mainly focuses on two key areas: analyzing volatile compounds in rice and characterizing the aroma quality [7]. The quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA) method is a subjective evaluation technique mainly used to establish descriptive words, which are then used to analyze the aroma attributes of the fragrant rice [8,9,10]. Gas chromatography, supplemented by related pretreatment and detection techniques, is currently the main objective flavor evaluation method [11]. Numerous studies have confirmed that the flavor of rice is jointly determined by the concentrations, thresholds, and interactions of different types of volatile compounds. Currently, more than 500 volatile components have been detected and identified in rice [12,13], mainly including hydrocarbons, alcohols, aldehydes, esters, ketones, phenols, heterocyclic compounds, and so forth [14,15]. Multiple studies using sensory evaluation and flavor metabolomics have analyzed the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in rice/millet [16,17], confirming that only a select few are responsible for the distinct and significant flavor profile of rice [18]. Studies have also reported the effects of different processing conditions on the flavor of rice [14]. These key aroma components undergo concentration changes during breeding, planting, drying, storage, processing, preservation, cooking, and oral chewing processes, and the compounds exhibit different flavors due to varying concentrations, thereby influencing the overall flavor of rice [19].

Currently, rice is classified into two main categories based on aroma: fragrant rice and nonfragrant rice. The key differences in volatile components between fragrant and nonfragrant rice include 2-acetyl-1-pyrrolidine (2-AP), 2-octene, isopentanol, 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, 1-octen-3-ol, and so forth [20]. 2-AP, first identified in 1982 [21], has a strong popcorn aroma [22,23,24]. It is responsible for the characteristic aroma compound of fragrant rice [25]. Several studies have also reported on the aroma types of rice. Lu et al. [12] used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to analyze the volatile components in fragrant rice from China and Thailand. They divided fragrant rice into three types (popcorn flavor, corn flavor, and lotus seed flavor) and determined the main aroma-active substances of each type. Dong et al. [26] used GC-MS, Gas chromatography–olfactometry (GC-O), and multivariate analysis to analyze the aroma chemical components of six different types of rice from India, Thailand, and South Korea. They identified the main compounds causing aroma differences. Zhou et al. [19] collected nine samples of rice with different aromas, established an aroma description word bank based on QDA, identified four aroma types, and analyzed the flavor substances in each aroma type. At present, the rice aroma research is mainly focused on fragrant rice. However, fragrant and nonfragrant rice have their own specific aromas for consumers, and the differences in their flavor substances result in certain differences in their aroma types. Thus, the classification of rice with different aroma types due to different flavor substances needs further systematic research.

Taking into account the significant influence of the aroma of raw rice on consumers’ purchasing decisions, this study focuses on raw rice as the research object, aiming to verify the feasibility of rice aroma differentiation based on the main varieties available in China. The material basis of rice aroma differences was systematically analyzed using sensory evaluation, GC-MS, and GC-IMS analytical methods. The aromas of different Chinese rice varieties were differentiated and the key flavor substances were explored, providing a reference for the quantitative evaluation and standard upgrade of rice aroma and offering high-quality products to consumers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2-Methyl-3-heptanone, 4-Hydroxy-2,5-dimethylfuran-3-one, Butyraldehyde, 1-Octanol, 2-Acetyl-1-pyrrolidine were procured from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). A mixed standard of n-alkanes (C9–C23) (chromatographic grade, purity ≥ 99.5%) was bought from Shanghai Anpu Laboratory Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). n-Ketones [2-butanone, 2-pentanone, 2-hexanone, 2-heptanone, 2-octanone, and 2-nonanone (all analytical grade)], phenethyl alcohol were procured from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Starch, Toothpick, pasteurized milk, quaker oatmeal, cream style sweet corn were procured from Wal-Mart Stores (Beijing, China). Ultrapure water was prepared by a Hokee Company (Hefei, China, HK-DI-10/20/30 model).

2.2. Sample Collection

11 different types of commercial raw rice, all with distinct aromas, were purchased between July and October 2024. Prior to the experiments, each sample was divided into three portions for subsequent research. These samples were vacuum-packed and stored at 4 °C. All experiments were completed within 2 months of rice purchase. All samples were prepared before each test, kept fresh in the refrigerator, and then brought to room temperature for evaluation. The samples were assigned three random numbers. Table 1 presents the numbers and variety information of the samples.

Table 1.

Information on commercially available rice samples.

2.3. Sensory Evaluation of Rice Flavor

According to the requirements of GB/T 16291.1-2012 (National Standard, 2012) [27], a rice sensory evaluation panel was formed based on previous findings [28,29,30]. 10 participants regularly engaged in sensory analysis of cereal products, primarily adults over the 20 years of age with at least two years of experience in the sensory evaluation of rice products, were enrolled in the study. Three sensory training sessions were conducted. In the first one, panelists with rich experience in rice descriptive sensory analysis generated aroma descriptors for raw rice samples studied. For the second session, the panelists performed a sensory evaluation of the samples based on their own subjective perceptions and recorded some different aroma descriptors. In the last session, all sensory panelists were asked to participate in a discussion of sensory descriptors screening and deletion. Ultimately, ten aroma attributes (starchy, grainy, floral, Popcorn, sweet, grassy, woody, oatmeal, dairy, corn) were determined to be most effective in characterizing the rice and highlighting key differences among them. After the training period, the quantitative description analysis was performed using the screened sensory descriptors and the provided standard references (Table 2) [19]. The strength of each descriptor ranged from 0 to 9 [31], with 0 representing no sensation and 9 representing a strong sensation (0.5 is the minimum increment).

Table 2.

The rice aroma descriptors and definitions.

The sensory experiment was conducted in an air-conditioned laboratory at 25 °C with good ventilation. The rice samples (20 g) were placed in a plastic cup and marked with a three-digit code according to Table 1. The participants were asked to quickly select the descriptors they thought were suitable to describe the flavor attributes of the rice. Samples were presented at intervals of approximately 5 min. The results of each aroma descriptor of samples were averaged for statistical analysis.

2.4. Flavor Metabolomic Analysis by HS-SPME-GC-MS

Flavor metabolomic analysis was performed on 11 different types of commercial raw rice. The method used headspace solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS), with an Agilent system consisting of a 7890B chromatograph and a 5977B mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The aroma compounds were extracted using a Supelco solid-phase microextraction fiber [50/30 µm (Divinylbenzene (DVB)/Carboxen (CAR)/Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), StableFlex (2 cm)], and the volatile compounds were separated using a DB-Wax capillary column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.4.1. Metabolite Extraction

First, 0.816 μg/μL of 2-methyl-3-heptanone standard solution was prepared using deionized water as the solvent. The rice samples (2000 ± 40 mg) were placed in 20 mL headspace bottles, and 1 μL of 2-methyl-3-heptanone was added as an internal standard. Headspace injection conditions included incubation at 60 °C, preheating for 15 min, adsorbing for 30 min, and desorption for 4 min.

2.4.2. GC-MS Analysis

The volatile substances were analyzed using a DB-Wax chromatographic column and an Agilent 7890B gas chromatography–5977B mass spectrometry system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The system used a nonsplit injection mode, with high-purity helium as the carrier gas. The pre-injection port purge flow rate was 3 mL/min, and the column flow rate was 1 mL/min. The initial temperature was controlled at 40 °C for 4 min, and then increased at a rate of 5 °C/min to 245 °C and maintained for 5 min. The injection port temperature was 250 °C, the transfer line temperature was 250 °C, the ion source temperature was 230 °C, and the quadrupole temperature was 150 °C. The electron impact ionization energy was 70 eV. The mass spectrometry scan range was set at m/z 20–400, and the solvent delay time was 2.37 min. After the measurement, the mass spectrum of the volatile compounds were then compared with data from the NIST 2017 database. Then, the actual retention index (RI) value is calculated according to the relevant research methods of the same laboratory [32,33]. The RI were compared with the values reported in the literature. When the difference is <50, it was inferred that the two match. The volatile compounds were quantified (semi-quantitative analysis) by dividing the peak areas of the compounds of interest by the peak area of 2-methyl-3-heptanone as internal standard. Each experiment with the samples was conducted triplicately.

2.4.3. Calculation of Relative Odor Activity Value

The relative odor activity values (ROAV) were performed to evaluate the specific contribution of each compound to the overall aroma, which was well reported in previous studies [34]. ROAV was mainly used to quantitatively evaluate the contribution of each volatile substance to the overall flavor of the test sample and thus identify key aroma-active compounds. A high ROAV is also indicative of the great contribution of a component to the overall flavor of the sample. The compounds with ROAV ≥ 1 were the principal aroma compounds of the sample, whereas those with 0.1 ≤ ROAV < 1 had a important modifying effects on its overall flavor. ROAV was calculated as described previously [35,36].

2.5. GC-IMS Analysis

GC-IMS analysis of volatiles was performed using an Agilent 490 GC (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) and a FavourSpec IMS instrument (Gesellschaft für analytische Sensorsysteme (G.A.S.), Dortmund, Germany) as described previously [37,38]. First, 5000 ± 100 mg of rice sample was ground at low temperature and placed in a 20 mL headspace vial. The headspace injection conditions included incubation at 60 °C for 20 min and splitless injection with an injection volume of 500 µL, an injection speed of 500 rpm, and an injector temperature maintained at 85 °C. A capillary column (15 m × 0.53 mm × 1.0 μm, MXT-5; Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA) was used, with a column temperature of 60 °C and 99.99% nitrogen as the carrier gas. A programmed pressure was employed with an initial flow rate of 2.0 mL/min, which was maintained for 2 min and then linearly increased to 10.0 mL/min for 8 min, 100.0 mL/min for 10 min, and 150.0 mL/min for 10 min. The chromatographic run time was set at 30 min, and the inlet temperature was maintained at 80 °C. The volatile compounds were identified based on the drift time and RI according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and G.A.S. databases. These measurements were performed in triplicate. The IMS conditions were as follows: ionization source, tritium (3H); drift tube length, 53 mm; electric field strength, 500 V/cm; drift tube temperature, 45 °C; drift gas, high-purity nitrogen (≥99.999%); flow rate, 75 mL/min; and positive ion mode. Each experiment with the samples was conducted in triplicate.

The retention index (RI) was calculated using n-ketones C4–C9 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) as external references by the Laboratory Analysis View (LAV) software(LAV version 2.0.0; G.A.S.) in the GC-IMS device. The volatile compounds were tentative identified based on comparison of RI and the drift time with the NIST library and IMS database retrieval software obtained from G.A.S (Dortmund, Germany, version 2.0.0). Finally, the intensities of the volatile compounds were analyzed according to the peak volumes of the selected signal peaks by Gallery Plot analysis (v.1.0.7, G.A.S.) [37]. Visual and quantitative comparisons of volatility differences between samples were performed using the Gallery plot plug-in. Two-dimensional top views and three-dimensional fingerprints were constructed using the Reporter plug-in.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Chroma Time-of-Flight (TOF) 4.3X software of LECO Corporation (St. Joseph, MI, USA) and NIST database were used for raw peak extraction, data baseline filtering and calibration of the baseline, peak alignment, deconvolution analysis, peak identification, integration, and spectrum matching of the peak area [39].

The Reporter, Gallery Plot, and Dynamic Principal component analysis (PCA) plug-ins in LAV software were used to generate two- and three-dimensional spectra, difference spectra, fingerprints, and PCA plots of volatile components for comparing VOCs between samples. In order to avoid deviations between measurements, the drift time of sample spectra was normalized relative to RIP drift time, which proceed automatically in the LAV software.

Excel and Origin 2021 software were used for statistical analysis, including principal component analysis (PCA), cluster analysis, spider plots, and histograms.

3. Results

3.1. Sensory Evaluation and Aroma Classification of Rice

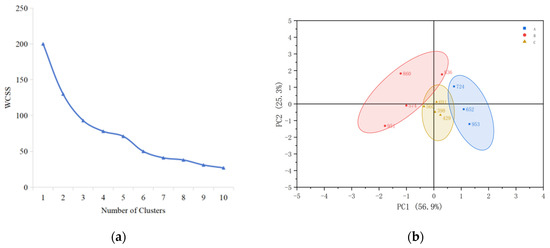

The flavor sensory properties of 11 different rice types were evaluated, and their aroma profiles were clustered using the Ward hierarchical clustering method. The number of clusters was determined by the elbow method using the Within-Cluster Sum of Squares (WCSS). The results are presented in Figure 1a. As the number of clusters increases, the WCSS value decreases. The decrease is rapid from class 1 to class 3, and after the number of clusters reaches 3, the curve of WSS changes gradually and becomes flat, which is identified as the “elbow” point. To maintain the tightness within the clusters while ensuring the degree of segmentation, cluster 3 is selected as the best clustering number. The 11 rice samples were divided into 3 major groups. The first group comprised three samples, and the second and third groups comprised four samples each. The results are shown in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

Ward hierarchical cluster analysis of sensory evaluation: (a) relationship between the number of clusters and WCSS, (b) cluster diagram of sensory evaluation of 11 rice samples, A: aroma type A rice; B: aroma type B rice; C: aroma type C rice.

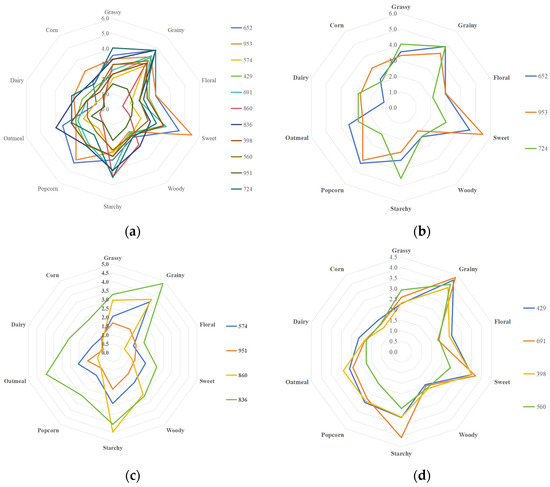

The aroma characteristics of each group of rice were analyzed, and a flavor profile spider plots was drawn (Figure 2), illustrating different aromas. (1) The first group included samples 652, 953, and 724. Their sweet, popcorn, cereal, and grassy aromas were more prominent, and no obvious floral aroma was observed. This group of samples was defined as the sweet aroma type (aroma type A). (2) The second group included samples 574, 951, 860, and 836. The most prominent aromas of this group were cereal and starchy, whereas their sweet and popcorn aromas were significantly reduced compared with other samples. Other sensory attributes were not obvious, so this group of samples was defined as the cereal aroma type (aroma type B). (3) The third group included samples 429, 691, 398, and 560. Their cereal, sweet, and starchy aromas were higher, and the aroma of this group was complex. Therefore, this group of samples was defined as a complex aroma type (aroma type C).

Figure 2.

Aroma profile spider plots of rice of different aroma types: (a) all rice samples; (b) aroma type A rice; (c) aroma type B rice; and (d) aroma type C rice.

3.2. Analysis of Volatile Aroma Compounds in Different Rice Aromas Based on HS-SPME-GC-MS

3.2.1. VOCs in Rice with Different Aroma Types

HS-SPME-GC-MS was used to analyze the volatile components of 11 aromatic rice samples. Table 3 presents the volatile compounds of the three aromatic rice types. HS-SPME-GC-MS analysis of 11 samples identified 74 volatile compounds. The number of volatile compounds varied among rice with different aromas. In addition, 52 volatile compounds with flavor characteristics were identified, which constituted 70.27% of the identified aroma compounds.

Table 3.

Comparison of the odor profiles and odor threshold values of the volatile compounds found in the three rice cultivars.

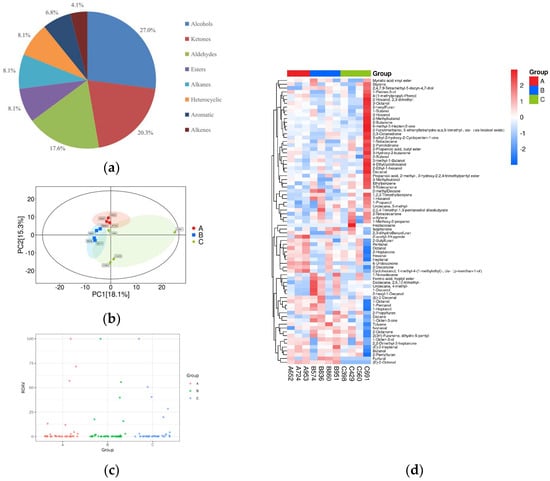

HS-SPME-GC-MS analysis of 11 samples characterized 74 volatile compounds into 8 categories, as shown in Figure 3a. Of these, alcohols accounted for 27%, followed by ketones molecules for 20.2%, aldehydes for 17.5%, esters, alkanes and heterocyclic for 8.1%, and aromatics compounds for 6.7%, and alkenes for 4%.

Figure 3.

Multivariate statistical analysis of volatile compounds: (a) pie chart of metabolite classification proportions; (b) cluster analysis: A: aroma type A rice; B: aroma type B rice; C: aroma type C rice; (c) relative odor activity values; (d) heat map of hierarchical clustering analysis for all groups.

A PCA of 11 rice varieties was performed based on volatile aroma compounds, as shown in Figure 3b. All samples were within the 95% confidence interval (Hotelling’s T2 ellipse), confirming clear differentiation between the three aroma types. Based on 74 volatile compounds, the samples were sorted into three distinct clusters: the first cluster comprised samples 652, 953, and 724; the second primarily comprised samples 574, 951, 860, and 836; and the third primarily comprised samples 429, 691, 398, and 560. This clustering was consistent with the cluster analysis results from the sensory evaluation. The ROAV of the volatile aroma compounds was calculated to determine which volatile compounds had the greatest impact on the overall flavor of the tested samples. This allowed the identification of key aroma compounds and more effective analysis of their contribution to the flavor of rice varieties, as shown in Figure 3c. An ROAV scatter plot was drawn based on the ROAV to visualize the distribution of the ROAV of flavor substances in different groups. Each point in the figure represents a substance. The horizontal axis of the ROAV scatter plot represents different sample groups, and the vertical axis represents the ROAV of flavor substances in these groups. A cluster analysis was conducted on all the volatile flavor substances of the samples, and a cluster heat map was drawn. Figure 3d shows the cluster heat map of the total content of volatile compounds in rice samples of different aroma types, indicating that volatile aroma compounds differed significantly among these samples.

3.2.2. Analysis of the Differential Volatile Profiling of Three Rice Cultivars

The 8 volatile compound values with the greatest differences were screened out by performing analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the volatile flavor compound data of the three rice types and based on the principle of ANOVA p-value < 0.05 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Analysis of variance of differential volatile metabolites.

Table 4 shows that the main differential volatile compounds were alkanes, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, and heterocyclic compounds, and so forth. (E)-2-Octenal and 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole exhibited significant aroma expression in rice. Among these, (E)-2-Octenal mainly contributed to the fatty, herbal, fresh, green, fruity, and nutty flavors [19]. 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole contributed to a nutty flavor, 1-Octen-3-one contributed to a herbal flavor [19,42,50].

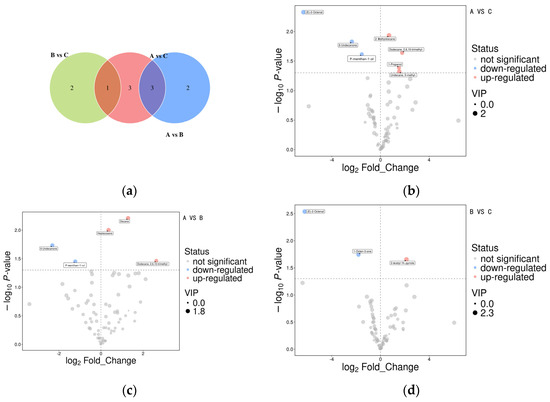

The volatile flavor data for the three aroma types were analyzed pairwise using Student t tests and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) model analysis of variance. Figure 4 shows the differential volatile compounds across different rice aroma types based on the Student t test (p < 0.05) and the variable importance in the projection (VIP) of the OPLS-DA model greater than 1. In Figure 4a, different circles represent different comparison groups. The numbers in the overlapping area indicate the number of common differentially expressed metabolites between the comparison groups, and the numbers in the nonoverlapping area indicate the number of unique differentially expressed metabolites. A total of 7 common differentially expressed metabolites between groups A and C, 5 between groups A and B, and 3 between groups B and C. Across the comparison groups, 3 common differentially expressed metabolites between A versus C and A versus B groups, and 1 between A versus C and B versus C groups.

Figure 4.

Differential flavor substances among aroma type A, B, C. (a) Venn analysis of differential metabolites among different comparison groups, (b) Volcano plots of differential metabolites of A versus C, (c) Volcano plots of differential metabolites of A versus B, (d) Volcano plots of differential metabolites of B versus C.

Figure 4b–d shows the results of the differential metabolite screening as volcano plots, with each dot representing a metabolite. The abscissa represents the fold change (logarithm to base 2) of each substance in the comparison group, and the ordinate represents the p value (negative logarithm to base 10) of the Student t test. The size of the scatter plot represents the VIP value of the OPLS-DA model, with larger scatter plots indicating higher VIP values. The significantly upregulated metabolites in Figure 4b–d are represented in red, the significantly downregulated metabolites are shown in blue, and the metabolites with no significant difference are indicated in gray. Figure 4b–d ashows that the A versus B comparison group had a higher number of differentially expressed metabolites, indicating a greater difference between aroma types A and B. In the three comparison groups, the flavor of the differential volatile substances in aroma type B was relatively weaker and not distinctive, indicating it had a less distinctive flavor than aroma types A and C, and A and C had better sweet, fruity, and other aromas compared with aroma type B.

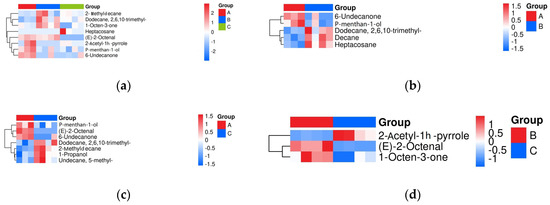

The Euclidean distance was used to quantify the differences in metabolites among different comparison groups. The data were clustered using the complete linkage method, and the results were presented as a heat map, shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Hierarchical cluster analysis heat map among aroma type A, B, C. (a) A versus B versus C comparison group, (b) A versus B comparison group, (c) A versus C comparison group, and (d) B versus C comparison group.

The different colors in the graph on the horizontal axis represent different rice aroma types, the vertical axis represents the differential metabolites, and the different color blocks represent the relative expression levels of the corresponding metabolites. Red indicates a higher expression level of the substance, and blue indicates a lower expression level. Figure 5a presents the data of the A versus B versus C comparison group. The expression levels of (E)-2-Octenal, 6-Undecanone, 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole, and P-menthan-1-ol were high in the aroma type A rice. Among these, (E)-2-Octenal had a nutty, fatty, herbal, fresh, and green aroma [19]. This also better explained the sensory results. Compared with aroma types B and C, aroma type A had a better sweet and grassy aroma. The expression levels of Dodecane, 2,6,10-trimethyl-, 1-Octen-3-one, and 2-Methyldecane were high in aroma type B, among which 1-Octen-3-one had a herbal, mushroom aroma [51]. This also better explained the sensory results that aroma type B had a more prominent starchy and grainy taste compared with aroma types A and C. In aroma type C, the expression levels of Heptacosane were high, and this group had richer differentiated volatile characteristics. This also confirmed that the aroma of this group was complex and was defined as a complex aroma type.

Figure 5b–d represents the data of the A versus B, A versus C, and B versus C comparison groups, respectively. In addition, the expression levels of 6-Undecanone, P-menthan-1-ol in type A were higher than in B in the A versus B comparison group. The expression levels of Dodecane, 2,6,10-trimethyl-, Decane and Heptacosane were higher in aroma type B than in aroma type A. However, the flavor characteristics of these volatile substances were not obvious, indicating that aroma type B had no prominent flavor characteristic. In the A versus C comparison group, the expression levels of 2-Methyldecane, 1-Propanol, and 5-Methylundecane were higher in aroma type C than in aroma type A. Among these, 1-Propanol had a better peanut aroma [51]. Therefore, type C had a better nutty and fruity aroma than types A. In aroma type B versus aroma type C comparison group, the expression levels of (E)-2-Octenal and 1-Octen-3-one were higher in aroma type B. (E)-2-Octenal contributed nutty, fatty, herbal, fresh, and green aroma characteristics [19]. The expression levels of 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole were higher in aroma type C. 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole had a bready, nutty, and caramel aroma [51]. Therefore, type C had a better nutty flavor than types B.

3.3. Analysis of Volatile Odor Components of Rice by GC-IMS Spectroscopy

3.3.1. Volatile Compounds Identified by GC-IMS

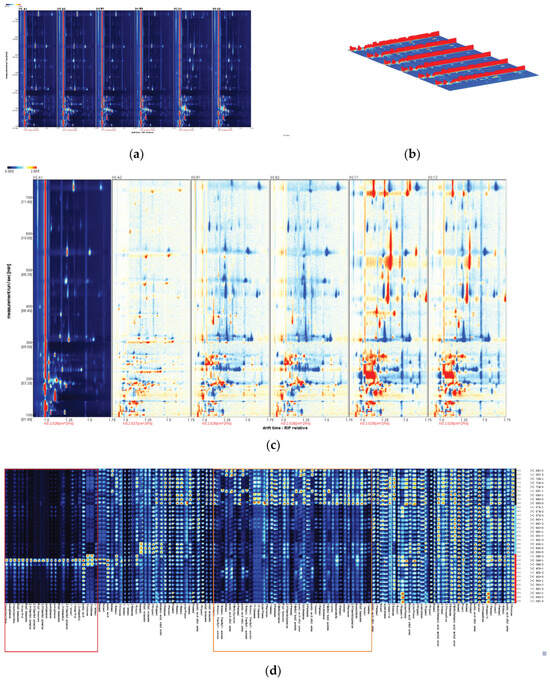

The volatile components of the three rice cultivars were determined using GC-IMS, and fingerprint patterns and cluster heat maps were obtained to more intuitively distinguish the differences in volatile components among different types of fragrant rice. As shown in Figure 6, the ion migration time and the position of the reactive ion peak (RIP) were normalized; the ordinate represents the retention time of the gas chromatography; the abscissa represents the ion migration time, and the vertical line at the abscissa 1.0 is the RIP. Figure 6a shows that most of the signals appeared in the retention time of 100–800 s and the drift time of 1.0–1.75. As shown in Figure 6b, the X, Y, and Z axes represent the ion drift time, retention time, and peak intensity of the volatile substances, respectively, which were used for identifying volatile substances [52]. In addition, some volatile compounds such as 1-pentanol, 1-propanol, and acetic acid ethyl ester produced multiple spots or signals, which were interpreted as protonated monomers, trimers, polymers, and proton-bound dimers in the fingerprint area, which could not be observed using GC-MS [53].

Figure 6.

GC-IMS analysis of volatile compounds in 11 samples of the 3 aroma types A, B, and C. Volatile fingerprints (a), gallery plots (b), and comparison of differences using A1 as a reference (c). Fingerprint of volatile components of rice with different flavors (d).

Figure 6a,b shows that the fingerprints of different aroma types of rice samples differed significantly after normalization of ion drift time and reactive ion peak position, with the signal intensities for A, B, and C showing considerable differences.

The fingerprints of two samples were randomly selected for each aroma type, using A1 as a reference. This reference sample was compared with the fingerprints of the other aroma types to generate a differential spectrum, as shown in Figure 6c. Higher concentrations are displayed in red, concentrations equal to the reference value are displayed in white, and concentrations below the reference value are displayed in blue. Although VOCs signal intensities within the same aroma type (A1/A2, B1/B2, and C1/C2) were not significantly different, they were significantly different among different aroma types, with A and C showing a significant difference. Samples C1 and C2 displayed more red dots compared with samples A1 and A2, indicating a more intense aroma and flavor profile for aroma type C. Samples B1 and B2 displayed more blue dots, indicating a milder, more balanced flavor profile, consistent with the sensory evaluation and flavor metabolomics results.

The fingerprint identification method was adopted to display the volatile chemical information in the samples for a deeper understanding of the flavor characteristics of different aroma types of rice, as shown in Figure 6d. In this figure, each row represents the signal peak of the volatile components of each sample, and each column represents the signal peak of a specific volatile chemical substance in different samples. The color of the signal peak represents the substance. These graphs present the complete volatile compound profile of each sample in an easily understandable manner, highlighting the differences between samples [54,55]. The volatile chemical fingerprints of aroma types A, B, and C were significantly different. The two distinct regions in the figure represent the differences in the volatile chemical fingerprints between different flavor types. The red region represents primarily alcohols, heterocyclic compounds, and ketones, whereas the orange region represents primarily esters and aromatic hydrocarbons. In the red region, the volatile chemical fingerprint of flavor type C was significantly higher than that of A and B, indicating that C had a higher content of alcohols, heterocyclic compounds, and ketones, giving it a richer flavor profile. In the orange region, the volatile chemical fingerprint of flavor type A was significantly higher than that of B and C, indicating that A had a higher content of esters and aromatic hydrocarbons, giving it a better sweet and fragrant flavor [56]. Flavor type B had fewer volatile aroma compounds than flavor types A and C, which is why the flavor of type B was softer than the other two aroma types.

3.3.2. Differential Analysis of Volatile Compounds Based on GC-IMS

Table 5 lists all the volatile substances in the three fragrant rice types and their peak intensities. A total of 55 volatiles were detected and identified, including 14 ketones, 13 alcohols, 12 esters, 8 aldehydes, 4 heterocyclic compounds, 3 aromatic hydrocarbon compounds, and 1 other compound. The number of these categories differed from the results of GC-MS. A total of 14 VOCs were identified as monomers and dimers. These chemicals had high proton affinity or concentration, generating several signals in the analysis [57]. The aforementioned data showed that the volatile aroma compounds of the three different aromatic rice types had significant characteristics [51]. The samples of aroma type A contained higher contents of (+)-limonene (lemon- and orange-like flavors), 1-hexanol (grassy flavor), 2-methylpyrazine (nutty, coffee, and cocoa-like flavors), 2-pentanone (fruity, floral, and grassy flavors), 3-methyl butyl acetate, cyclohexanone, ethyl butanoate (a unique fresh fruity flavor), n-pentanal (fruity and floral flavors), styrene (floral and sweet flavor), 1-butanol (fruity and caramel flavors), 3-methyl-acetate 1-hexanal (grassy and fruity flavors), 1-pentanol (vanilla and sweet flavors), and 2-heptanon (coconut, sweet, and fruity flavors), indicating a better sweet aroma. In contrast, the samples of aroma type C contained higher contents of 1,2-ethanediol and 1-octen-3-ol (mushroom, lavender, and green-like flavors), 2,6-dimethyl pyrazine (peanut butter and peanut flavors), 2-acetylpyridine (popcorn flavor), acetophenone, and ethyl hexanoate (fruity and green flavors), indicating a better overall aroma. The various volatile flavor substances in aroma type B, were between those in aroma types A and C, without any significant outstanding features, which was consistent with the results of sensory evaluation and flavor metabolomics.

Table 5.

GC-IMS analysis of volatile components of the three aromatic rice samples.

3.4. Comparison of Different Volatile Compounds in Rice with Different Aroma Type Based on HS-SPME-GC-MS and GC-IMS

The differential flavor and compound analysis showed that the three rice aromas could be differentiated in sensory evaluation, HS-SPME-GC-MS, and GC-IMS.

From a sensory perspective, the main differential flavors of the three aromas included sweetness, woodiness, popcorn, cereal, and corn flavors. The main feature of aroma type A was the prominent sweetness, and the main feature of aroma type B was the prominent woodiness, cereal, and starch flavors. Aroma type C was more comprehensive than aroma types A and B, with a balanced focus on cereal, sweetness, starch, and popcorn flavors.

From the perspective of differential volatile substances, the main differential compounds included alkanes, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, and heterocyclic compounds.

Aldehydes are an important type of volatile compounds in rice. These compounds have a low odor threshold and give rice pleasant grassy, citrus, and fresh grassy flavors at low levels. They are an important component of rice flavor. Aldehydes are decomposition products of lipid oxidation [58]. Among these aldehydes, the key volatile aroma compounds of rice are octanal [59], pentanal (valeraldehyde), and heptanal [48], which were also found in the differential compounds of the three aroma types. Studies have shown that heptanal, octanal, and so forth are formed from linoleic acid precursors [60]. In this study, the presence of aldehydes such as octanal and n-pentanal resulted in the prominent sweet flavor of aroma type A compared with aroma type B.

Alcohols are the second major VOCs identified in rice. Methanol, 1-propanol, 1-butanol, 1-pentanol [60], and 1-octen-3-ol are the key volatile aroma compounds of rice. They were all detected in the control sample and were the most abundant besides aldehydes [15]. Alcohols (1-octen-3-ol, hexanol, 1-octanol, etc.) have higher olfactory thresholds, contributing to rice’s mild aromatic profile [61,62]. The floral and fruity aroma of rice is attributed to alcohols [1]. Among all alcohols, 1-octen-3-ol is produced during lipid oxidation. It has a high content, a low threshold, and the smell of wild mushrooms, and contributes the most to the aroma of rice [63]. Previous reports have shown that 1-octen-3-ol can be derived from the peroxide of linoleic acid [64]. In this study, the contents of alcohols such as 1-octen-3-ol and 1-propanol were higher in aroma type C than in aroma type A, which is why aroma type C exhibited a richer flavor than aroma type A.

Ketones are the third largest class of volatile components found in japonica rice. These compounds contribute a pleasant fruity flavor to the rice [61,65]. The main ketones identified in this study were 2-butanone and 2-heptanone, which gave cooked rice a unique fruity and pleasant aroma [66]. 2-Heptanone is produced from oleic acid [60]. In this study, the presence of ketones such as 2-heptanone resulted in a prominent sweet aroma in aroma type A compared with aroma types B and C.

Esters can give a fruity and floral aroma to rice [67]. However, they generally have a relatively high taste threshold, thus contributing little to the flavor of rice [68]. Ethyl acetate, octanoate acetate, and other esters affect the flavor of rice, making it more intense [15]. Therefore, the esters in type A contributed more to its sweet aroma.

Other volatile compounds contributing to odor include heterocyclic compounds such as pyridines and pyrazines. Heterocyclic compounds are mainly formed through nonenzymatic browning reactions or Maillard reactions [69]. Although these compounds have low concentrations, their thresholds are also low, so they contribute significantly to rice flavor, often imparting sweetness, nutty flavors, and beany notes to rice [1,15]. Aroma type C contains more heterocyclic compounds such as pyridines and pyrazines than aroma type A, which is one of the reasons why aroma type C has a more complex aroma.

Because hydrocarbon compounds have a higher threshold, their contribution to the overall aromatic properties of rice is limited [70]. Therefore, although some aroma type contain higher levels of hydrocarbons, their impact on their distinctive flavors is minimal.

4. Discussion

This study used sensory evaluation, HS-SPME-GC-MS, GC-IMS, and data analysis to systematically investigate the differences in flavor and volatile aroma compounds among different rice samples. The study also explored the key aroma components differentiating rice aroma types, dissecting the molecular basis for these flavor differences. The main findings were as follows:

- Feasibility of distinguishing rice aromas based on sensory evaluation: Cluster analysis based on sensory evaluation data categorized rice aromas into three types: sweet aroma type (A), cereal aroma type (B), and complex aroma type (C). Type A exhibited a prominent sweet and popcorn aroma, type B exhibited a more prominent grainy and starchy aroma, and type C exhibited a more complex aroma.

- Nontargeted metabolomics analysis using HS-SPME-GC-MS: The findings revealed the diversity and differences in volatile components of rice with different aroma types. A total of 74 volatile compounds were identified and classified into three aroma types through PCA, consistent with the sensory results. In the A versus B versus C comparison group, 8 major differential aroma compounds were identified, primarily including alkanes, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, and heterocyclic compounds. (E)-2-Octenal, 6-Undecanone, 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole, and P-menthan-1-ol in type A gave it a better sweet aroma, Dodecane, 2,6,10-trimethyl-, 1-Octen-3-one, and 2-Methyldecane in type B gave it a better starchy and cereal flavor. 2-Acetyl-1h-pyrrole, Heptacosane, and 1-Propanol in type C contributed to a complex aroma.

- GC-IMS analysis: The results revealed the diversity and differences in volatile components of rice with different aroma types. The fingerprints of rice samples with different aroma types showed significant differences. Compared with aroma type A, aroma type C was stronger and aroma type B was milder and more balanced, consistent with the results of sensory evaluation and flavor metabolomics. Samples of aroma type A contained (+)-limonene, 2-methylpyrazine, 2-pentanone, ethyl butanoate, n-pentanal, styrene, 1-butanol, 3-methyl-, acetate, 1-hexanal, 1-pentanol, and 2-heptanone, contributing to a more sweet aroma. Samples of aroma type C contained 1-octen-3-ol, 2,6-dimethyl pyrazine, 2-acetylpyridine, and ethyl hexanoate, contributing to a more complex aroma. The volatile aroma compounds in aroma type B fell between those in aroma types A and C, with no significant standout characteristics, consistent with the results of sensory evaluation and flavor metabolomics.

This study attempted to validate the feasibility of rice aroma differentiation. A comprehensive analysis was conducted on mainstream commercially available rice varieties to determine the molecular factors behind their distinct aromas, using sensory evaluation, flavor metabolomics. Combining complementary methods such as HS-SPME-GC-MS and GC-IMS, a more complete profile of volatile compounds was obtained, which helped distinguish different rice aromas and revealed their molecular basis. Future investigations should build on this study by increasing sample diversity, integrating metabolomics and machine learning technologies to further analyze rice flavor differences and their formation pathways, thereby guiding processing innovation and quality improvement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and S.Q.; methodology, H.R.; software, H.Y.; validation, S.Q., H.R. and H.Y.; formal analysis, H.Y.; investigation, S.Q. and H.Y.; resources, M.Z. and S.Q.; data curation, H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Q.; writing—review and editing, S.Q.; visualization, H.R.; supervision, L.Z. and M.Z.; project administration, S.Q.; funding acquisition, L.Z., M.Z. and S.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

1. Nature of the Research Qualifies for Exemption: This study constitutes a scientific evaluation of raw rice based on sensory analysis. It does not fall under the category of research involving invasive human procedures, or exposing participants to significant physiological or psychological risk. 2. Adherence to National Standards and Safety Protocols: The design and execution of this sensory evaluation experiment strictly followed the relevant regulations of the Chinese National Standards, specifically GB/T 15682-2008 [71] “Inspection of grain and oils-Method for sensory evaluation of paddy or rice cooking and eating quality” and GB/T 16291.1-2012 “Sensory analysis-General guidance for the selection, training and monitoring of assessors-Part 1:Selected assessors”. All testing procedures were standardized, low-risk sensory perception activities. 3. Participant Informed Consent and Voluntariness: All participants were fully informed prior to the test regarding the nature, procedures, duration, and information about the samples they would encounter. Participation was based entirely on voluntariness. Participants retained the right to withdraw from the test unconditionally at any stage without any adverse consequences. In light of the fact that this study presented minimal risk, followed testing procedures per authoritative national standards, and fully implemented informed consent and privacy protection measures, we hereby declare that this research qualified for an ethics exemption.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants of this tasting experiment who gave a fair and objective assessment of the different aroma types of rice.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Shengmin Qi, Haibin Ren, Haiqing Yang and Lianhui Zhang were employed by the COFCO Corporation. They participated in study design, data collection, analysis, or decision to publish in the study. This relationship is disclosed here and has not influenced the content or conclusions of this work. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| HS-SPME-GC-MS | Headspace solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography mass spectrometry |

| HS-GC-IMS | Headspace gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry |

| GC-O | Gas chromatography-olfactometry |

| RI | Retention index |

| ROAV | Relative odor activity value |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis |

| VIP | Variable Importance in the Projection |

| RT | Retention time |

| QDA | Quantitative descriptive analysis |

| LAV | Laboratory Analysis View software |

References

- Verma, D.K.; Srivastav, P.P. A paradigm of volatile aroma compounds in rice and their product with extraction and identification methods: A comprehensive review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaza, G.; Huma, N.; Sharif, M.K.; Zia, M.A. Probing a best suited brown rice cultivar for the development of extrudates with special reference to Physico-Chemical, microstructure and sensory evaluation. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.; Sikora, M.; Garud, N.; Flowers, J.M.; Rubinstein, S.; Reynolds, A.; Huang, P.; Jackson, S.; Schaal, B.A. Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8351–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Kurata, N.; Wang, Z.X.; Wang, A.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y. A map of rice genome variation reveals the origin of cultivated rice. Nature 2012, 490, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, D.M.; Willy, M. International Rice Outlook:International Rice Baseline Projections 2023–2033. AAES Res. Rep. 2024, 5, 1015. Available online: https://aaes.uada.edu/communications/publications/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/csdb/en?amp= (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Dai, Z.; Fan, X.; Liu, M.; Ma, J.; Shang, W.; Zhou, Z. A study on volatile metabolites screening by HS-SPME-GC-MS and HS-GC-IMS for discrimination and characterization of white and yellowed rice. Cereal Chem. 2020, 97, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H.L.; Koop, L.A.; Riste, M.E.; Miller, R.K.; Maca, J.V.; Chambers, E.; Hollingsworth, M.; Bett, K.; Webb, B.D.; McClung, A.M. Developing a common language for the U.S. rice industry: Linkages among breeders, producers, processors and consumers. In TAMRC Consumer Product Market Research; Texas A&M: College Station, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Meullenet, J.F.; Marks, B.P.; Griftin, K.; Daniels, M.J. Effects of rough rice drying and storage conditions on sensory profiles of cooked rice. Cereal Chem. 1999, 76, 438–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, K.O. Effect of milling ratio on sensory properties of cooked rice and on physicochemical properties of milled and cooked rice. Cereal Chem. 2001, 78, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyaningsih, W.; Majchrzak, T.; Dymerski, T.; Namiesnik, J.; Palma, M. Key-Marker volatile compounds in aromatic rice (Oryza sativa) grains: An HS-SPME extraction method combined with GCxGC-TOFMS. Molecules 2019, 24, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hu, Z.; Fang, C.; Hu, X. Characteristic Flavor Compounds and Functional Components of Fragrant Rice with Different Flavor Types. Foods 2023, 12, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champagne, E.T. Rice aroma and flavor: A literature review. Cereal Chem. 2008, 85, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lu, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, Z. Volatile compounds, affecting factors and evaluation methods for rice aroma: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.S.; Lee, K.S.; Jeong, O.Y.; Kim, K.J.; Kays, S.J. Characterization of volatile aroma compounds in cooked black rice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, J.F.; Bassinello, P.Z.; Colombari Filho, J.M.; Lindemann, I.S.; Elias, M.C.; Takeoka, G.R.; Vanier, N.L. Volatile compounds profile of Brazilianaromatic brown rice genotypes and its cooking quality characteristics. Cereal Chem. 2018, 96, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.Z.; Lan, Y.B.; Zhu, J.M.; Westbrook, J.; Hoffmann, W.C.; Lacey, R.E. Rapid identification of rice samples using an electronic nose. J. Bionic Eng. 2009, 6, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakte, K.; Zanan, R.; Hinge, V.; Khandagale, K.; Nadaf, A.; Henry, R. Thirty-three years of 2-acetvl-1-pyrroline, a principal basmati aroma compound in scented rice (Oryza sation L.): A status review. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, S.; Wei, J.; Chen, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, X. Systematical construction of rice flavor types based on HS-SPME-GC–MS and sensory evaluation. Food Chem. 2023, 413, 135604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griglione, A.; Liberto, E.; Cordero, C.; Bressanello, D.; Cagliero, C.; Rubiolo, P.; Bicchi, C.; Sgorbini, B. High-quality ltalian rice cultivars: Chemical indices of ageing and aroma quality. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttery, R.G.; Ling, L.C. 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline: An important aroma component of cooked rice. Chem. Ind. 1982, 958–959. [Google Scholar]

- Routray, W.; Rayaguru, K. 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline:key aroma component of aromatic rice and other food products. Food Rev. Int. 2018, 34, 539–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.G.; Duarte, G.H.B.; Mariutti, L.R.B.; Bragagnolo, N. Aroma profile of rice varieties by a novel SPME method able to maximize 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline and minimize hexanal extraction. Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Bagchi, T.B.; Dhali, K.; Kar, A.; Sanghamitra, P.; Sarkar, S.; Majumder, J. Evaluation of sensory, physicochemical properties and Consumer preferenceof black rice and their products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Oh, Y.; Kim, T.H.; Cho, Y.H. Quantitation of 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline inaseptic-packaged cooked fragrant rice by HS-SPME/GC-MS. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.Y.; Robert, L.; Shewfelt, K.-S.L.; Stanley, J.; Kays, J. Comparison of odor-active compounds from six distinctly different fice flavor types. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2780–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 16291.1-2012; Sensory Analysis—General Guidance for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Assessors—Part 1: Selected Assessors. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Brown, M.D.; Chambers, D.H. Sensory characteristics and comparison of commercial plain yogurts and 2 new production sample options. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, S2957–S2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Ma, M.J.; Yu, M.; Bian, Q.; Hui, J.; Pan, X.; Su, X.X.; Wu, J.H. Classification of Chinese fragrant rapeseed oil based on sensory evaluation and gas chromatography-olfactometry. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 945144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Mi, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, S.; Ye, G. Construction of aroma association network of cooked rice based on gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and sensory analysis. Flavour. Fragr. J. 2024, 39, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Han, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, B. Rapid prediction of the aroma type of plain yogurts via electronic nose combined with machine learning approaches. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, T.; Wohlgemuth, G.; Lee, D.Y. FiehnLib: Mass spectral and retention index libraries for metabolomics based on quadrupole and time-of-flight gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009, 81, 10038–10048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Guan, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, S.; Mi, Y. Study on the correlation between aroma compounds and texture of cooked rice: A case study of 15 Japonica rice species from Northeast China. Cereal Chem. 2025, 102, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y. Discrimination and characterization of the volatile profiles of five Fu brick teas from different manufacturing regions by using HS–SPME/GC–MS and HS–GC–IMS. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1788–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemert, L.J.V. Compilations of Odour Threshold Values in Air, Water and Other Media; Oliemans Punter: Zeist, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, F.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, K.; Hu, H.; Zhang, H. Comparative flavor analysis of eight varieties of Xinjiang flatbreads from the Xinjiang Region of China. Cereal Chem. 2019, 96, 1022–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.Y.; Bai, L.; Feng, X.; Chen, Y.P.; Zhang, D.; Yao, W.S. Characterization of Jinhua ham aroma profiles in specific to aging time by gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS). Meat Sci. 2020, 168, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailimuhan, A.; Ren, X.; Zhang, M.; Tuohetisayipu, T.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Liang, S.; Wang, Z. Characterization of japonica rice aroma profiles during in vitro mastication by gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) and electronic nose technology. Int. J. Food Eng. 2022, 18, 679–688. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.G.; Tan, Y.Y.; Gossner, S.; Li, Y.F.; Shu, Q.Y.; Engel, K.H. Impact of Crossing Parent and Environment on the Metabolite Profiles of Progenies Generated from a Low Phytic Acid Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Mutant. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2396–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajarayasiri, J.; Chaiseri, S. Comparative study on aroma-active compounds in Thai, black and white glutinous rice varieties. Kasetsart J. Nat. Sci. 2008, 42, 715–722. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Kays, S.J. Aroma-active compounds of wild rice (Zizania palustris L.). Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinge, V.; Patil, H.; Nadaf, A. Aroma volatile analyses and 2AP characterization at various developmental stages in Basmati and Non-Basmati scented rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Rice 2016, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezussek, M.; Juliano, B.O.; Schieberle, P. Comparison of key aroma compounds in cooked brown rice varieties based on aroma extract dilution analyses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpawattana, M.; Yang, D.S.; Kays, S.J.; Shewfelt, R.L. Relating sensory descriptors to volatile components in flavor of specialty rice types. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahattanatawee, K.; Rouseff, R.L. Comparison of aroma active and sulfur volatiles in three fragrant rice cultivars using GC-Olfactometry and GC-PFPD. Food Chem. 2014, 154, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraval, I.; Mestres, C.; Pernin, K.; Ribeyre, F.; Boulanger, R.; Guichard, E.; Gunata, Z. Odor-active compounds in cooked rice cultivars from Camargue (France) analyzed by GC-O and GC-MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5291–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kim, K.Y.; Baek, H.H. Potent aroma-active compounds of cooked Korean non-aromatic rice. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 19, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xue, Y.; Shen, Q. Changes in the major aroma-active compounds and taste components of Jasmine rice during storage. Food Res. Int. 2020, 133, 109160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, L.G.; Hacke, A.; Bergara, S.F.; Villela, O.V.; Mariutti, L.R.B.; Bragagnolo, N. Identification of volatiles and odor-active compounds of aromatic rice by OSME analysis and SPME/GC-MS. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, C.; Liu, K.; Liu, Q. Volatile Organic Compounds, Evaluation Methods and rocessing Properties for Cooked Rice Flavor. Rice 2022, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishant, G.; Mansi, G.; Devansh, B.; Neelansh, G.; Rudraksh, T.; Apuroop, S.; Ganesh, B. FlavorDB2: An Updated Database of Flavor Molecules. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 7076–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Y.P.; Blank, I.; Li, F.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. GC × GC-ToF-MS and GC-IMS based volatile profile characterization of the Chinese dry-cured hams from different regions. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Schwab, W.; Ho, C.T.; Song, C.; Wan, X. Characterization of the aroma profiles of oolong tea made from three tea cultivars by both GC-MS and GC-IMS. Food Chem. 2022, 376, 131933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Timira, V.; Zhao, J.; Lin, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Z. Insight into the characterization of volatile compounds in smoke-flavored sea bass (lateolabrax maculatus) during processing via HS-SPME-GC-MS and HS-GC-IMS. Foods 2022, 11, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Q.; Liu, S.; Hong, P.; Zhou, C.; Zhong, S. Characterization of the effect of different cooking methods on volatile compounds in fish cakes using a combination of GC-MS and GC-IMS. Food Chem. 2024, 22, 101291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xi, J.; Xu, D.; Jin, Y.; Wua, F.; Tong, Q.; Yin, Y.; Xu, X. A comparative HS-SPME/GC-MS-based metabolomics approach for discriminating selected japonica rice varieties from different regions of China in raw and cooked form. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L.; Xu, D.; Wang, J.; Gilard, V.; Wu, M.; et al. Comparative study of volatile organic compound profiles in aromatic and non-aromatic rice cultivars using HS-GC-IMS and their correlation with sensory evaluation. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 203, 116321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, R.; Craske, J.D.; Wootton, M. Comparative studies on volatile components of non-fragrant and fragrant rice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1996, 70, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.J.; Mcclung, A.M. Volatile profiles of aromatic and nonaromatic rice cultivars using SPME/GC-MS. Food Chem. 2010, 124, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsoor, M.A.; Proctor, A. Volatile component analysis of commercially milled head and broken rice. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Asimi, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, Z.S. Effects of fatty acids on taste quality of cooked rice. Food Sci. 2019, 40, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, D.K.; Mahato, D.K.; Srivastav, P.P. Simultaneous distillation extraction (SDE): A traditional method for extraction of aroma chemicals in rice. In Science and Technology of Aroma, Flavor, and Fragrance in Rice. Science and Technology of Aroma, Flavor, and Fragrance in Rice, 1st ed.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Su, H.M.; Bi, X.; Zhang, M. Effect of fragmentation degree on sensory and texture attributes of cooked rice. J. Food Process Preserv. 2019, 43, e13920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Sasahara, S.; Akakabe, Y.; Kajiwara, T. Linoleic Acid 10-Hydroperoxide as an Intermediate during Formation of 1-Octen-3-ol from Linoleic Acid in Lentinus decadetes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2003, 67, 2280–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Seo, H.S.; Lee, K.R.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. Effect of milling degrees on volatile profiles of raw and cooked black rice (Oryza sativa L. Cv. Sintoheugmi). Appl. Biol. Chem. 2018, 61, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, R.W.; Holguin, G. Volatile components of unprocessed rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1977, 25, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xie, G.; Wu, C.; Lu, J. A study on characteristic flavor compounds in traditional chinese rice wine-guyue longshan rice wine. J. Inst. Brewing. 2010, 116, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W. Determination of the volatile composition in brown millet, milled millet and millet bran by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Molecules 2012, 17, 2271–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, Y.A.; Tetsuya, Y.A.; Mikio, N.; Hidemasa, S.; Tsutomu, H. Volatile Flavor Components of Cooked Rice. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1978, 42, 1229–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.Y.; Xi, J.Z.; Xu, X.M.; Yin, Y.; Xu, D.; Jin, Y.M.; Wu, F.F. Volatile fingerprints and biomarkers of Chinese fragrant and non-fragrant japonica rice before and after cooking obtained by untargeted GC/MS-based metabolomics. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 15682-2008; Inspection of Grain and Oils-Method for Sensory Evaluation of Paddy or Rice Cooking and Eating Quality. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.