Abstract

Chaenomeles speciosa (Sweet) Nakai (CF), a traditional food in East Asia and a recent addition to clinical dietary recommendations, has demonstrated potential for managing hyperuricemia. However, its bioactive components and therapeutic mechanisms remain largely unexplored. In this study, we used an integrative approach incorporating serum pharmacochemistry, metabolomics, bioinformatics, molecular docking, and in vitro/vivo validation to investigate CF’s effects and mechanisms in hyperuricemia. In hyperuricemic mice, CF significantly reduced serum uric acid, creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels, improved kidney histopathology, and restored redox balance by increasing antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD and GSH-Px) while lowering malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. Metabolomic analysis revealed that CF modulated pathways associated with oxidative stress, including purine metabolism, arachidonic acid metabolism, and α-linolenic acid metabolism, to reverse hyperuricemia-associated metabolic perturbations. Correlation analysis between differential metabolites and serum-absorbed constituents identified androsin, cynaroside, and salicin as potential bioactive compounds. These compounds showed high predicted binding affinities to COX-1, PGE2, and XOD in molecular docking, and these interactions were validated by in vitro assays, where the compounds effectively suppressed inflammatory cytokine production and inhibited XOD activity. Overall, CF exerts anti-hyperuricemic and renoprotective effects through coordinated regulation of purine metabolism, inflammation, and oxidative stress, supporting its potential as a functional food or complementary therapy for hyperuricemia-related conditions.

1. Introduction

The global prevalence of hyperuricemia is on the rise, posing a significant public health challenge due to its strong bidirectional association with renal dysfunction and chronic kidney disease [1,2]. While hyperuricemia arises from an imbalance between uric acid (UA) production and excretion [3], elevated serum UA levels exacerbate kidney damage through mechanisms including inflammatory pathway activation, oxidative stress induction, and direct impairment of renal excretory function [4]. Notably, while pharmaceutical treatments can help to regulate UA levels, they are often associated with limitations such as side effects and limited efficacy. This highlights the need for alternative therapeutic approaches, such as dietary interventions, which have the potential to regulate UA levels and provide renal protection with fewer risks.

Dietary modulation represents a frontline strategy for managing serum UA concentrations: purine-rich foods augment endogenous UA synthesis and elevate serum levels, while increasing fruit intake and reducing animal product consumption may mitigate hyperuricemia risk [5,6]. Among fruits with potential therapeutic value, Chaenomeles speciosa (Sweet) Nakai (CF, commonly known as “ZhoupiMugua” in China)—a member of the Rosaceae family widely cultivated in East Asia [7]—has garnered attention for its nutritional and bioactive properties. Specifically, CF fruits are enriched in flavonoids, triterpenes (e.g., oleanolic acid, ursolic acid), organic acids, and tannins [8,9], which contribute to their documented anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and renal-protective effects [10,11,12]. Critically, closely related Chaenomeles sinensis has demonstrated xanthine oxidase (XOD) inhibitory activity, reducing serum UA levels in hyperuricemic mice [13], suggesting the genus may harbor untapped potential for hyperuricemia management.

Reflecting this promise, CF fruit has been included in China’s Dietary Guidelines for Hyperuricemia and Gout in Adults (2024 Edition) as a recommended dietary supplement [National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2024]. However, despite its widespread consumption and preliminary evidence of efficacy, the specific bioactive compounds in CF responsible for UA-lowering effects, their molecular targets, and the metabolic pathways they modulate in vivo remain poorly defined. This knowledge gap is compounded by the multifactorial nature of hyperuricemia and the complex phytochemical profile of CF, necessitating a comprehensive, integrated investigative approach.

To address these limitations, the present study employs metabolomics, bioinformatics, and in vivo and vitro validation to dissect the therapeutic mechanisms of CF fruit in a hyperuricemia model. Our objectives are threefold: (1) identify CF-derived bioactive compounds; (2) evaluate the effects of CF on hyperuricemia and renal injury; (3) explore the molecular mechanisms and targets of CF. This integrated strategy will provide novel mechanistic insights into CF’s role as a functional food for hyperuricemia management and related renal complications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of C. speciosa Fruits Extracts

Chaenomeles speciosa fruit (CF) was provided by Qilingtou Mugua planting base (Changyang, China) and authenticated by Prof. Xinqiao Liu from school of pharmaceutical science, South-Central Minzu University. 90 g of CF sample was decocted with water (1:10, w/v) for 40 min. The extraction was repeated twice. The collected solution was filtered and concentrated to 50 mL volume for experiments. Extraction yield (17.73 ± 1.86%, n = 3 batches) and final extract concentration was 1.8 g/mL.

2.2. Reagents

Allopurinol (ALL) was acquired from Hefei JiuLian Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Hefei, China, Batch No. 20220905). Potassium oxonate (PO, purity ≥ 98%), hypoxanthine (HX, purity ≥ 99%), monosodium urate (MSU), androsin and cynaroside were obtained from Shanghai Yuanye Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China, Cat. No.: S17112, S18025, S30775, B20131, B20887). Salicin was acquired from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China, Cat. No.: S104923). Assay kits of xanthine oxidase (XOD), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), uric acid (UA) and creatinine (CRE) were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China, Cat. No.: A002-1-1, C03-1-1, C012-2-1, C011-2-1). Malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) were acquired from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China, Cat. No.: S0131S, S0109, S0057S). Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) were acquired from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan, Cat. No.: CK04). ELISA kits for prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) was purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China, Cat. No.: SEKM-0173) and Shanghai Jianglai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China, Catalog No.: JL13697). ELISA kits for interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were purchased from Abclonal Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China, Cat. No.: RK00027, RK00006). Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat. No.: L2630).

2.3. Compositional Analysis of CF

1.0 g CF watery extract was added with 40 mL 80% methanol and ultrasonicated for 30 min. Suspension was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min under 4 °C, then 100 μL of supernatant was pipetted into an injection vial for detection. Sample separation was performed using a Vanquish Flex UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (Waters Co., Milford, MA, USA). HPLC conditions: mobile phase A (water + 0.1% formic acid, v/v)/B (acetonitrile, v/v); flow rate 0.3 mL/min, column temp 40 °C, injection 6.0 μL. Gradient: 98% A (0–1.0 min) → 70% A (14.0 min) → 0% A (25.0–28.0 min) → 98% A (28.1–30.0 min), linear transitions. The MS data was collected by a hybrid quadrupole orbitrap mass spectrometer (Q Exactive, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a HESI-II spray probe. The data was acquired in “Full scan/dd-MS2” mode. Full scan parameters were set as follows: resolution 7000, automatic gain control (AGC) target 1 × 106, mass-to-charge ratio scanning range: 100–1500. The dd-MS2 data was collected with the parameters of resolution 17,500, auto gain control target 1 × 105, maximum isolation time 50 ms, loop count of top 10 peaks, isolation window m/z 2, collision energy 10 V, 30 V, 60 V and intensity threshold 1 × 105. Metabolites were identified via a multi-dimensional comprehensive evaluation by searching the reference standard database (TCM Pro 2.0, Hexin Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and an in-house theoretical compound library. The in-house library was constructed by integrating published data from Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Herbal Compound Identification Database, TCMSP, TCMID, and literature-reported constituents of the studied herbal formula. Identification was based on multiple orthogonal criteria: retention time deviation (<±0.2 min), precursor ion mass error (<5 ppm), MS/MS fragment pattern similarity (>85%), isotope distribution consistency, and relative peak intensity.

2.4. Animal Experiments

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) male KM mice (6–8 weeks old, 18–22 g) were purchased from Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention [License No. SCXK (E) 2020-0018, SYXK 2021-0089, Wuhan, China]. Before the experiment initiation, the mice were allowed one-week environmental adaptation period to recover from transportation stress and adapt to the housing conditions. Animals were housed 6 per cage (sufficient activity spaces, terile wood shavings bedding, changed twice weekly) in an SPF laboratory under a 12 h light–dark cycle (23 ± 3 °C, 40–70% humidity) with standard chow (purchased from Wanqian Jiaxing Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) and water ad libitum. All mice were randomly assigned to each group using a random number table. Administration and all outcome assessments were performed double-blind to eliminate experimenter bias. The study was approved by the Committee on Research Ethics and Technology Security, South-Central Minzu University (Approval No. 2022-scuec-057, Approval date: 2 November 2022, Wuhan, China). All procedures were conducted in accordance with Chinese legislation on the use and welfare of animals.

48 mice were divided into 6 groups randomly, namely the control group (CON), the model group (PO + HX, 300 mg/kg + 500 mg/kg, allopurinol group (ALL, 20 mg/kg), CF extract groups including low (CF-L, 0.8 g/kg), medium (CF-M, 1.6 g/kg) and high (CF-H, 3.2 g/kg). With the exception of the control group (injections an equal volume of normal saline), all mice were administered intraperitoneal injections of PO and gavaged HX to establish a hyperuricemia model. Both PO and HX were suspended in 0.5% CMC-Na. The mice were orally administered with the positive and tested samples 1 h later. The control and model groups were administered an equivalent volume of saline via oral gavage. Experiments were conducted daily in the morning in an SPF-grade operating room for 14 days. During the experiment, the occurrence of toxic or lethal events in mice will be observed.

2.5. Blood and Tissues Sample Collection

After 14 days of treatment, the mice were weighed, anesthetized, and subsequently euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation to obtain blood samples via enucleation for further analysis. Whole blood was on standing for two hours, then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min under 4 °C to collect serum. Simultaneously, liver and kidney tissues were rapidly isolated and rinsed with 0.9% saline solution. The left kidney was fixed for histopathological analyses (final n = 6/group after quality control), whereas the right kidney and whole liver were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until biochemical and metabolomics assays.

2.6. Biochemistry and Histopathology Detection

Biochemical markers including XOD, BUN, UA, CRE, MDA, SOD, GSH-Px and PGE2 were measured according to the instructions of the kit. The detection wavelengths and principles are followings: UA (510 nm, enzymatic colorimetric method), CRE (546 nm, sarcosine oxidase method), BUN (520 nm, diacetyl monoxime colorimetric method), XOD (530 nm, colorimetric method), MDA (532 nm, TBA-based method), SOD (560 nm, NBT photoreduction method), PGE2, TNF-α and IL-1β (450 nm, sandwich ELISA). All assays were run in duplicate, and standard curves showed linearity with R2 > 0.990. Target-wavelength OD values were measured for samples, blank-subtracted to eliminate background interference, and used for subsequent concentration and activity quantification.

Renal tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-μm sections. Hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed on the prepared sections. The stained sections were observed and photographed under a 200× light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Subsequently, semi-quantitative assessment of key pathological parameters was performed [14,15].

2.7. Identification of Blood Components

A total of 100 μL of serum sample was added to 300 μL pre-cooled chromatographic grade methanol. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C using a refrigerated centrifuge, 270 μL of supernatant was carefully collected without disturbing the precipitate. The supernatant was concentrated by vacuum centrifugation for 4 h, with sealed centrifuge tubes to prevent sample loss. Subsequently, 90 μL of 50% methanol aqueous solution was added, followed by vortexing at 800 rpm for 1 min and centrifuged again at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. HPLC and MS conditions are the same as in Section 2.3 (Supplementary Tables S1–S4).

2.8. Biological Information Analysis

The SwissTargetPrediction database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/, accessed on 22 October 2024) and PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 22 October 2024) were used to retrieve the predicted targets of CF’s blood-entering constituents. After deduplicating predicted targets, core targets were identified by applying a threshold of Tanimoto similarity score (T-value) > 0.12. Visualization of protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks was performed using the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/, accessed on 22 October 2024) and visualized via Cytoscape software (version 3.8.0) to explore the interrelationships between the active compounds and core targets involved in hyperuricemia treatment.

KEGG and GO enrichment analyses were conducted using the ClusterProfiler package (version 4.14.4) in R. Functional terms and pathways with both p value < 0.05 and adjusted p value (padj) < 0.05 were considered significantly enriched.

2.9. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

Serum samples from the control, model, and high-dose groups were subjected to metabolomic analysis. After thawing on ice, 100 μL of serum was mixed with 300 μL of pre-cooled methanol, vortexed for 1 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. A 300 μL aliquot of the supernatant was collected, lyophilized under vacuum, and reconstituted in 100 μL of 50% methanol using sonication in an ice-water bath. The mixture was centrifuged again, and 90 μL of the final supernatant was transferred to vials for analysis. Each sample was injected at a volume of 5 μL.

Chromatographic separation was performed using a Waters UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) maintained at 40 °C. Mass spectrometry was conducted on a UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS system (Q Exactive™, Thermo Fisher Scientific), operating in both full MS and data-dependent MS2 (dd-MS2) modes. Key settings included a resolution of 70,000 for full MS and 17,500 for MS2, AGC targets of 1 × 106 and 1 × 105, a maximum injection time of 50 ms, and stepped collision energies of 10, 30, and 60 eV. Up to 10 precursors per cycle were selected for fragmentation with dynamic exclusion. Additional LC and MS parameters are provided in Supplementary Tables S4–S7.

Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by pooling aliquots from all study groups and were injected at regular intervals to monitor instrument stability. Ion features with a coefficient of variation (CV) > 15% in QC samples were excluded from further analysis (3504 features retained). Retention time alignment and total ion current (TIC) normalization were performed using Progenesis QI software. Metabolite identification was based on accurate mass and MS2 spectral matching against the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) and lipid databases such as LipidMaps.

2.10. Molecular Docking

Three bioactive compounds were selected for molecular docking based on serum component analysis and bioinformatics predictions. The crystal structures of COX-1 (PDB ID: 1EQG), XOD (1FIQ), and PGE2 (PDB ID: 2ZB4) were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/, accessed on 2 May 2025). Co-crystallized ligands were retained for redocking validation, and water molecules were removed using PyMOL 2.6.0.

Ligand structures were retrieved from the PubChem database and converted to 3D format. Geometry optimization was performed using the MMFF94 force field in Open Babel. Proteins and ligands were prepared in AutoDock Tools (version 1.5.7), including hydrogen addition and conversion to PDBQT format. Docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina with an exhaustiveness value of 10. The grid box parameters are provided in the Supplementary Table S10. Known inhibitors such as indomethacin (for COX-1 and PGE2) and febuxostat (for XOD) were used as positive controls. Docking results were visualized using PyMOL.

2.11. BMDM & BRL3A Cell Culture

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were isolated from the bone marrow of the femur and tibia of C57BL/6J mice. After euthanasia, the mice were sterilized by immersing in 75% ethanol, then femurs and tibiae were stripped in a sterile environment and rinsed in pre-cooled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Bone marrow cells were rinsed with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and released, and the cell suspension was filtered through a 70 μm filter, centrifuged to collect the cells, and lysed in erythrocyte lysate for 1 min and then centrifuged again. The cell sediment was resuspended in dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10 ng/mL macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Buffalo Rat Liver-3A (BRL3A) cells are fibroblast-like cell lines isolated from the liver of Buffalo rats. The BRL3A cells line was purchased from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. BRL3A cells at passages 3–10 were used for all experiments. Both BMDM and BRL3A cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humid environment.

2.12. Cell Viability Assay

Cytotoxicity of the three key compounds was detected using CCK-8 assay. After BMDM was fully differentiated and BRL3A cells grew to logarithmic phase, BMDM and BRL3A cells were inoculated in 96 microtiter plates (cell concentration 6 × 104/mL) for overnight. After treatment with different concentrations of androsin, cynaroside and salicin (1, 5, 10, 25, and 100 μM) for 24 h, 10 μL of CCK-8 was carefully added to each well to avoid air bubbles. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured after 1–2 h of incubation using an enzyme labeller (Multiskan SkyHigh, Thermo Scientific, USA).

2.13. Establishment of Cell Models and Indicator Detection

BMDM cells were inoculated in 96-well plates at 6 × 104/mL, pre-treated by adding different concentrations of androsin, cynaroside and salicin for 24 h, with MCC950 as a positive control. After stimulation with LPS (400 ng/mL) for 3 h, the supernatant was discarded, and medium containing MSU (400 μg/mL) was added to stimulate the cells for 6 h. Cell supernatants were collected, and the levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in cell supernatants were determined using assay kit.

BRL3A cells were inoculated into 24-well plates at a concentration of 3 × 105 /mL. After 16 h of inoculation, the cells were treated with 1 mM xanthine and different concentrations of androsin, cynaroside and salicin, with Allopurinol as a positive control. The cell protein was extracted 48 h later, and the activity of XOD enzyme was detected by using XOD kit.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 and SPSS 26.0 software. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Prior to statistical analysis, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution, and Levene’s test was used to evaluate the homogeneity of variances. For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed independent-samples t-test was applied when the data met the assumptions of normality and equal variances; otherwise, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.0, with error bars representing mean ± standard deviation. Sample sizes (n) for each group are indicated in the figure legends and in the Results section.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of CF Components

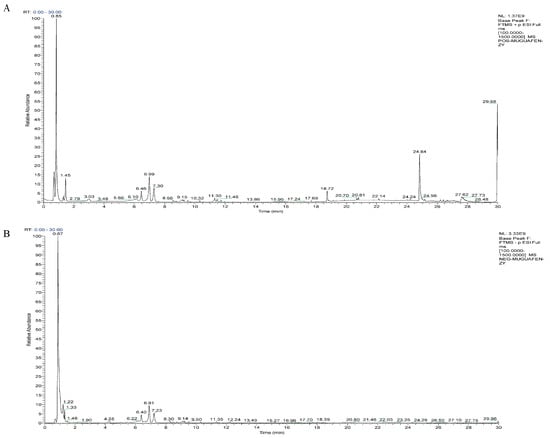

The base peak ion flow chromatograms of CF detected in positive and negative modes are shown in Figure 1. Chemical compounds such as flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics, organic acids, glycosides, phenylpropanoids, amino acids, alkaloids, and other classes were analyzed for different content levels in CF. Flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics, and organic acids exhibited a distinctly high proportion among them. Terpenes mainly included oleanic acid, deacetylasperulosidic acid methyl ester, linalool, asiatic acid, and bayogen. Flavonoids, for example, catechin, L-epicatechin, althosanin, rutin, hyperoside, astipine, hyperoside aglycone, kaempferol, and quercetin were found. Organic acids comprising quinic acid, citric acid, shikimic acid, isocinnamic acid, and p-coumaric acid. Phenols included Salicin, 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid, Protocatechualdehyde, Isovanilline, Sinapyl alcohol, etc. Table 1 contains detailed information, with compounds sorted by relative peak area. The top 10 components with the highest abundance accounted for 89.3% of the total peak area.

Figure 1.

The base peak ion chromatogram of CF detected in positive and negative mode. (A) ESI (+). (B) ESI (−).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of CF (Sort by relative peak area).

3.2. Effect of CF on Serum UA, CRE, and BUN Levels

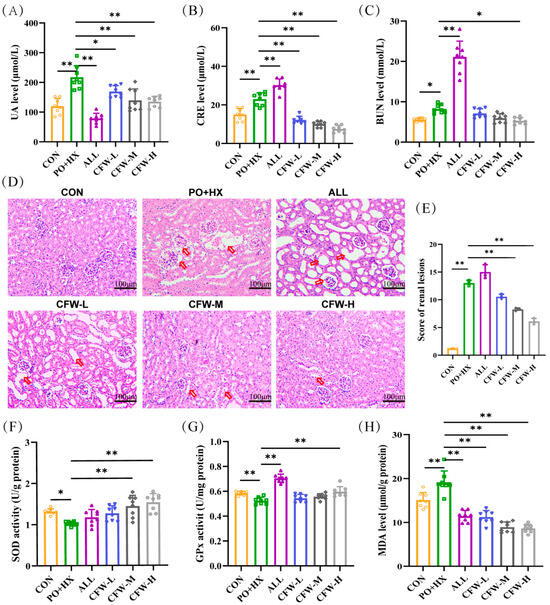

Many studies have confirmed that the PO + HX combination model is better than the single inducer [16,17] and no deaths or overt signs of acute toxicity (e.g., lethargy, piloerection, or reduced food intake) were observed in the experiment. The data for UA, CRE, and BUN are shown in Figure 2A–C, CF dose-dependently and significantly ameliorated hyperuricemia and renal dysfunction in the model. The PO + HX model group displayed serum UA, creatinine, and BUN levels of 216.75 ± 82.97 μmol/L, 21.78 ± 3.86 μmol/L, and 7.96 ± 1.26 mmol/L, respectively. Oral administration of CF produced dose-dependent reductions: CF-L, CF-M, and CF-H decreased UA by 25%, 29.6%, and 32.9% (to 162.78 ± 37.45, 152.65 ± 60.11, and 145.02 ± 32.13 μmol/L; p < 0.01); CRE by 45%, 55%, and 59% (to 12.30 ± 2.59, 10.40 ± 5.35, and 9.73 ± 2.61 μmol/L; p < 0.01); and BUN by 6% (ns), 19% (ns), and 34% (to 7.61 ± 2.44, 6.62 ± 2.60, and 5.54 ± 1.39 mmol/L; p < 0.05 only for CF-H). The ALL group showed higher CRE/BUN than the model, which aligns with clinical reports of ALL’s potential nephrotoxicity [18,19,20]. These marked reductions in serum UA, CRE, and BUN are biologically and clinically significant, as they restore UA below the crystallization threshold, normalize glomerular filtration, and effectively reverse hyperuricemia-induced renal tubular injury and inflammation.

Figure 2.

Results of biochemical indices of CF in HUA mice. (A–C) Serum levels of uric acid (UA), creatinine (CRE), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) in different groups (n = 8). (D–E) Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (scale bar: 100 μm; magnification: ×200) and quantitative analysis of renal lesion scores based on H&E staining. The red arrows indicate pathological injuries, including renal tubular dilation and glomerular atrophy. (F–H) Activities of SOD (F) and GPx (G), and MDA content (H) in the liver (n = 8). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 between the indicated groups.

3.3. Effect of CF on Renal Histopathological Change

As shown in Figure 2D,E and Supplementary Table S10, the CON group exhibited normal renal structure with clear glomerular boundaries and no inflammatory cell infiltration (total injury score 1.175 ± 0.035). In the model group, HE staining revealed renal edema, marked dilation of the renal tubular lumen, glomerular atrophy with basement membrane thickening, and obvious inflammatory cell infiltration (total injury score 13 ± 0.707, p < 0.001 vs. CON).

ALL group further increased the histopathological injury score to 15.5 ± 1.414 (p < 0.05 vs. model), this situation was consistent with the literature reported aggravated renal pathology description [19,20]. In contrast, CF treatment dose-dependently reduced pathological alterations: the low, medium, and high-dose CF groups showed total injury scores of 10.55 ± 0.636, 8.4 ± 0.141, and 6.15 ± 0.778, respectively (CF-M and CF-H p < 0.01 vs. model), with the high-dose group approaching the normal histological appearance of the CON group. After CF treatment, the pathological alterations in model mice improved.

3.4. Effect of CF on Antioxidant Activity

Liver samples were examined to assess the antioxidant properties of CF by measuring the activities of SOD and GSH-Px, along with the levels of MDA. Figure 2F shows that the SOD concentration in the model group is significantly under that in the CON group (1.32 ± 0.07 vs. 1.02 ± 0.05 U/g, p < 0.05). Conversely, SOD levels were elevated in the CF-M and CF-H groups (1.44 ± 0.26 and 1.53 ± 0.20 U/g, p < 0.01). In Figure 2G, compared with the model group (0.52 ± 0.03 U/mg), the CF-H group (0.59 ± 0.04 U/mg, p < 0.01) showed a significant increase in GSH-Px. The MDA concentration in the model group (19.17 ± 2.53 μmol/g) was markedly (p < 0.01) higher CON group (15.08 ± 1.73 μmol/g) in Figure 2H. However, the CF group significantly regulated MDA levels (11.21 ± 1.5, 8.9 ± 1.18, and 8.6 ± 0.94 μmol/g, p < 0.01). The elevated MDA levels, together with the decreased activities of SOD and GSH-Px, collectively indicated the occurrence of oxidative imbalance in hyperuricemic mice. CF treatment significantly restored antioxidant enzyme activities and decreased MDA levels. Importantly, these biochemical improvements in antioxidant capacity were consistent with the renal histopathological findings.

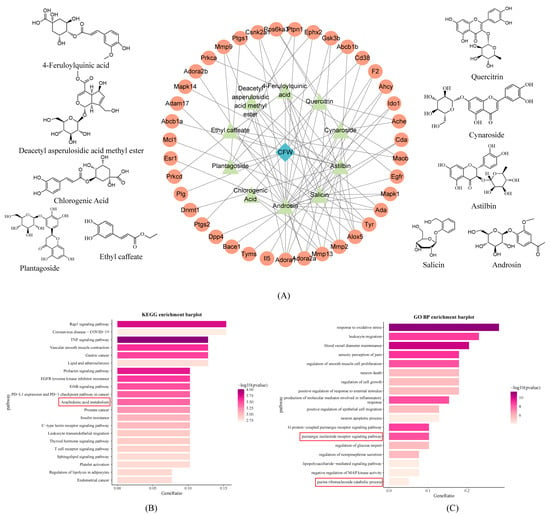

3.5. Joint Analysis of Absorbed Components and Bioinformatics

LC-MS analysis of the absorbed constituents identified 12 prototype components, such as androsin, chlorogenic acid, cymaroside, quercitrin, and salicin, along with 12 secondary metabolites (Supplementary Figure S1, Table S8). Notably, these prototype components were consistent with the composition of the CF aqueous extract. Based on their presence in the blood and aqueous extract, these prototype compounds were selected for network pharmacology analysis. They were screened using the SwissTargetPrediction database (probability > 0.12), yielding 10 key components and 39 non-redundant predicted targets. Subsequently, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the STRING database and visualized in Cytoscape software version 3.8.0, alongside the chemical structures of key components (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Biological information analysis of constituents absorbed into the blood. (A) Structural formula and PPI bioinformatic analysis of CF blood entry components, blue diamond indicates chaenomeles speciosa fruits, green triangles indicate entry components, and orange circles indicate potential targets for each entry component. (B) KEGG analysis of potential target of CF. (C) GO BP analysis of potential target of CF The red box contains the KEGG pathways and GO biological processes associated with arachidonic acid and purine metabolism.

Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the ClusterProfiler package in R. Significantly enriched items were defined as those with both p value < 0.05 and adjusted p value (padj) < 0.05 after Benjamini–Hochberg correction, resulting in 159 KEGG pathways and 984 GO biological processes (Figure 3B,C). KEGG analysis revealed that CF may exert anti-inflammatory effects by modulating pathways such as arachidonic acid metabolism. GO analysis highlighted CF’s involvement in oxidative stress regulation and purine nucleotide receptor-mediated signaling pathways. These findings provide insights into the molecular targets and pathways regulated by CF in hyperuricemia.

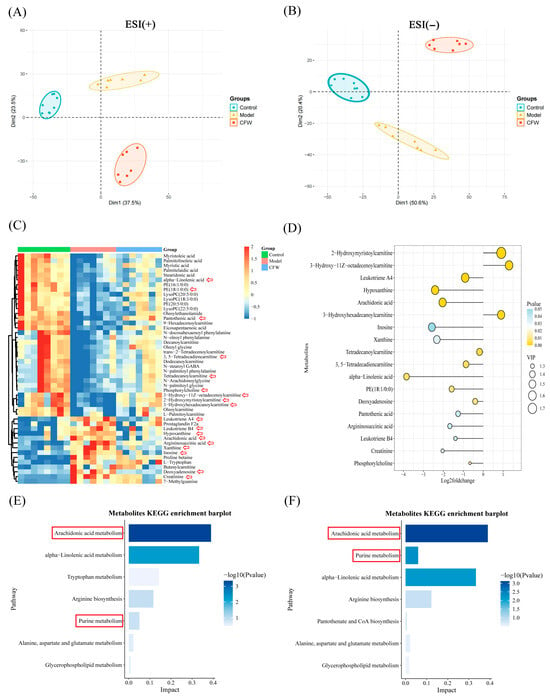

3.6. Regulatory Effect of CF on Serum Metabolic Homeostasis in Hyperuricemic Mice

Serum untargeted metabolomics analysis was conducted using UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS to identify metabolic alterations associated with hyperuricemia and evaluate the metabolic modulation induced by CF treatment (Supplementary Figure S2). Metabolites were identified using Progenesis QI software to process the collected data. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed distinct separation among the control, model, and CF-treated groups in both positive and negative ion modes (Figure 4A,B), with the CF group clustering closer to the control group, indicating a partial metabolic rebalancing. To further characterize the metabolic changes, OPLS-DA was employed, yielding robust models with good explanatory and predictive power (positive ion mode: R2Y(cum) = 0.983, Q2(cum) = 0.784; negative ion mode: R2Y(cum) = 0.985, Q2(cum) = 0.837), validated through 200-time permutation tests (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 4.

Metabolomics data analysis. (A) Positive ion PCA score plot for each group (n = 7). (B) Negative ion PCA score plot for each group (n = 7). (C) Heatmap of differential metabolites between groups (n = 7). Red arrows mark the metabolites displayed in the lollipop plot. (D) The lollipop plot illustrates the p values, Log2 fold change values, and VIP scores of these metabolites (ranked by VIP value), based on the comparison between the model group and the CF-treated group. In this analysis, a Log2 fold change < 0 indicates that the metabolite level was downregulated after CF treatment, whereas a Log2 fold change > 0 reflects an upregulation in response to CF treatment. (E) Analysis of metabolic pathways in the control and model groups containing differential metabolites. (F) Pathway analysis of different metabolites in the model and CF groups The red arrows denote metabolites exhibiting significant differences. The red box indicates the KEGG pathways related to arachidonic acid and purine metabolism.

A total of 48 differential metabolites were identified using the criteria of VIP > 1 from the OPLS-DA model and p < 0.05 from Student’s t-test (Supplementary Table S9, Figure 4C). Among them, key metabolites dysregulated in the model group—including arachidonic acid, leukotriene A4, hypoxanthine, xanthine, and alpha-linolenic acid—were significantly reversed by CF treatment (Figure 4C,D). These metabolites are closely associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, and purine metabolism. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis highlighted arachidonic acid metabolism, purine metabolism, and alpha-linolenic acid metabolism as the top pathways impacted by CF intervention (Figure 4E,F). Notably, several key metabolites involved in inflammatory lipid signaling and purine metabolism were significantly altered in the model group and partially restored following CF treatment. In particular, arachidonic acid and leukotriene A4—pro-inflammatory eicosanoids derived from the arachidonic acid cascade—were markedly elevated in hyperuricemic mice but were significantly reduced after CF administration (Figure 4C,D), suggesting an attenuation of eicosanoid-mediated inflammatory responses. Similarly, the levels of hypoxanthine and xanthine, central intermediates in purine degradation that contribute to ROS production through xanthine oxidase, were decreased after treatment, consistent with the observed decreased uric acid. Moreover, CF increased metabolites such as phosphocholine and creatinine, which may indicate improvements in membrane phospholipid turnover and cellular energy metabolism. These metabolic adjustments align with the restored activities of antioxidant enzymes (SOD and GSH-Px) and reduced MDA levels, collectively supporting that CF confers renoprotective effects by mitigating oxidative stress and modulating key metabolic pathways, including arachidonic acid metabolism and purine catabolism.

3.7. Integrated Analysis of Metabolic Networks and Blood-Absorbed Constituents-Metabolite Correlations

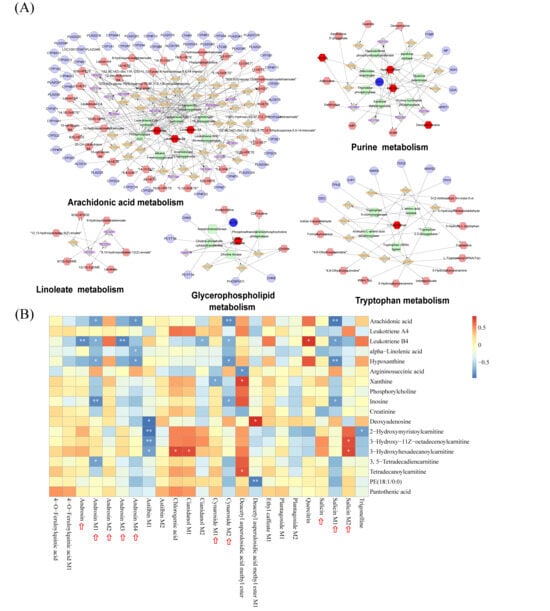

To systematically visualize the metabolic interactions modulated by CF, we constructed an integrated networ based on the identified differential metabolites and the predicted targets of the blood-absorbed constituents. The network topology unveiled the complex interplay among upstream genes, enzymatic reactions, and downstream metabolites. As shown in Figure 5A, the identified CF-regulated metabolite, specifically arachidonic acid, leukotriene A4, hypoxanthine, and xanthine, occupied central positions within the arachidonic acid and purine metabolism pathways. Serving as key metabolic nodes, their prominence highlights these pathways as critical targets potentially regulated by CF.

Figure 5.

Integrated analysis of metabolic pathways and component-metabolite correlations. (A) Interaction networks of key metabolic pathways, including arachidonic acid, purine, linoleate, glycerophospholipid, and tryptophan metabolism. In the network diagrams, circles, diamonds, hexagons, and rounded rectangles represent genes, reactions, metabolites, and proteins, respectively. (B) Heatmap visualizing the correlation analysis between the constituents of CF absorbed into the blood (X-axis) and differential endogenous metabolites (Y-axis). The color scale indicates the correlation coefficient (red for positive correlation, blue for negative correlation). * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 indicate statistical significance The red arrows indicate blood components and their secondary metabolites exhibiting significant correlations.

To further elucidate the potential “material basis” responsible for these metabolic regulations, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis between the 24 absorbed constituents (including prototype components and secondary metabolites) of CF and the 18 key differential metabolites identified by serum untargeted metabolomics (Figure 5B). The heatmap revealed significant correlations between specific prototype components and the restoration of metabolic markers. Notably, salicin, cynaroside, androsin and its metabolites exhibited strong negative correlations with pro-inflammatory lipid mediators, specifically arachidonic acid and leukotriene B4. Meanwhile, some of them also showed significant negative correlations with purine metabolism-related markers, including hypoxanthine, xanthine, and inosine. These results suggest that these blood-absorbed components are potential active ingredients of CF, supporting its role in lowering uric acid and protecting the kidney by regulating arachidonic acid and purine metabolism pathways.

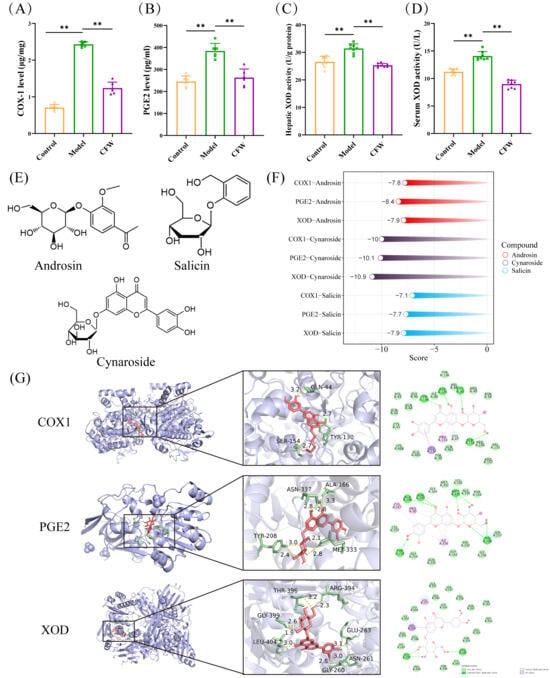

3.8. Molecular Docking of COX-1/PGE2/XOD & In Vivo/In Vitro Validation

We analyzed key indicators related to arachidonic acid metabolism and purine metabolism in the serum, kidneys, and liver of mice with hyperuricemia. The results demonstrated that CF significantly reduced the levels of COX-1 (1.23 ± 0.16 μg/mg) and PGE2 (262.85 ± 38.93 pg/mL) in the kidney (Figure 6A,B). Additionally, CF was found to markedly suppress the activity of XOD in both the serum and liver (9.22 ± 1.66 U/g and 25.18 ± 1.75 U/L) (Figure 6C,D).

Figure 6.

Experimental validation of therapeutic targets of CF and molecular docking analysis. (A,B) Results of enzyme immunoassay for COX-1 and PGE2 in kidney (n = 6). (C) The impact of CF on the hepatic XOD activity level. (D) Effect of CF on the level of XOD activity in serum (n = 8). (E) Structural formulae for androsin, cynaroside, and salicin. (F) Molecular docking scores of COX-1-1EQG, PGE2-2ZB4 and XOD-1FIQ with active compounds in CF (androsin, cynaroside and salicin). (G) The molecular docking results of cynaroside are shown Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ** p < 0.01 as compared with PO+HX model group.

Molecular docking analysis was conducted to explore the potential interactions between the primary blood-entry constituents of CF—androsin, cynaroside, and salicin and three key targets implicated in hyperuricemia: COX-1, PGE2, and XOD. The chemical structures of these compounds are shown in Figure 6E. Docking simulations suggested that all three compounds may exhibit favorable binding affinities toward the selected targets. Notably, cynaroside demonstrated the lowest binding energy values across multiple targets, indicating a potentially stronger predicted interaction (Figure 6F,G). Additionally, Indomethacin and Febuxostat were employed as positive controls targeting COX-1/PGE2 and XOD, respectively (Supplementary Figure S4).

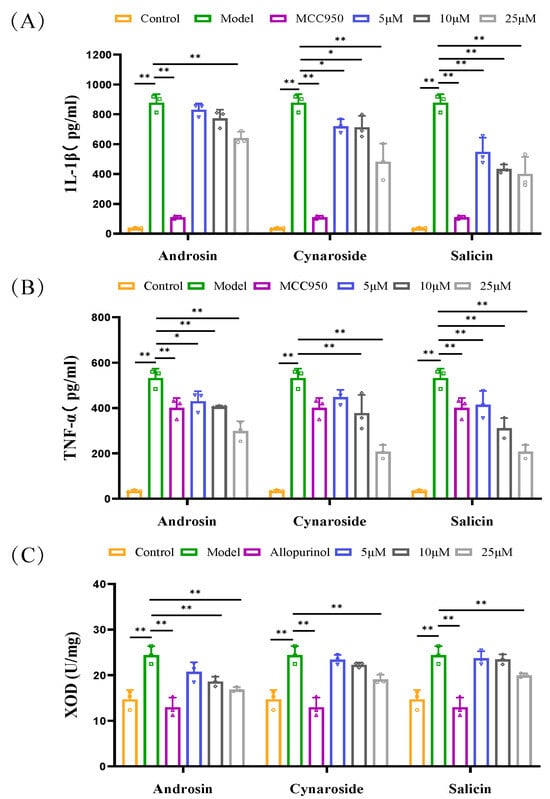

To confirm the predicted interactions, the compounds were tested in relevant cell models. These three compounds did not exhibit toxicity to BMDM and BRL3A cells at concentrations ranging from 5 to 100 μM in vitro experiments (Supplementary Figure S5). At a concentration of 25 μM, androsin, cynaroside, and salicin significantly inhibited the elevation of IL-1β and TNF-α levels in BMDM cells stimulated by LPS + MSU, with cynaroside and salicin exhibiting the stronger anti-inflammatory effect. Additionally, these compounds effectively inhibited XOD activity in BRL3A cells under a xanthine environment at this concentration (Figure 7A–C). These findings highlight the multi-targeted mechanism of CF and its components in the treatment of hyperuricemia and underscore its potential as a therapeutic agent for this condition.

Figure 7.

Regulatory effects of androsin, cynaroside, and salicin on inflammatory cytokines and XOD activity in in vitro models. (A,B) show the regulatory effects of androsin, cynaroside, and salicin on the levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α in the supernatant of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) co-stimulated with LPS and MSU (n = 3). (C) The effects of androsin, cynaroside, and salicin on the levels of XOD protein activity in BRL3A cells under a xanthine environment (n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 as compared with PO + HX model group.

4. Discussion

Hyperuricemia is a complex metabolic disorder inextricably linked to chronic renal inflammation and oxidative stress [21]. While XOD inhibitors such as allopurinol remain the standard of care, their clinical utility is often compromised by adverse reactions, including hypersensitivity and potential renal toxicity, underscoring the urgent need for safer, multi-target natural alternatives [22,23,24]. In the present study, we employed an integrative strategy combining serum pharmacochemistry, metabolomics, and experimental validation to systematically decode the therapeutic mechanisms of CF. Our findings provide evidence that CF exerts anti-hyperuricemic and renoprotective effects through a coordinated multi-level mechanism: systemically restoring redox balance and regulating purine and arachidonic acid metabolism. Furthermore, androsin, cynaroside, and salicin were identified as key blood-absorbed bioactive components that likely serve as the material basis for these effects, potentially by inhibiting both XOD activity and the COX-1/PGE2 inflammatory axis.

Clinically, the primary therapeutic goal is to lower serum UA to preventing urate crystal deposition [25]. In our in vivo experiments, CF treatment elicited a potent, dose-dependent reduction in serum UA, CRE, and BUN levels, effectively restoring them toward baseline. These biochemical improvements were strongly corroborated by histopathological evidence, where CF treatment markedly reversed HUA-induced renal injuries, including glomerular atrophy, tubular dilation, and inflammatory cell infiltration. It is worth noting that the biochemical improvements in renal function were closely mirrored by the restoration of antioxidant capacity [26,27]. The observed upregulation of hepatic SOD and GSH-Px activities, coupled with the reduction in MDA content, suggests a potential mechanism by which CF may attenuate renal damage: namely, by interrupting the “oxidative stress–inflammation” vicious cycle, which in turn could help preserve the structural integrity of the kidney. Intriguingly, the positive control group (Allopurinol) exhibited paradoxically elevated CRE/BUN levels and aggravated renal pathology compared to the CF group, a phenomenon likely associated with the known nephrotoxicity or hypersensitivity risks of allopurinol [28,29], further highlighting the superior safety profile of CF at the effective dose.

To investigate the metabolic alterations associated with these phenotypic improvements, we employed untargeted metabolomics. The analysis indicated that CF treatment helps regulate perturbed metabolic networks, particularly involving purine catabolism and inflammatory lipid signaling. Notably, the metabolic adjustments observed in the CF group were consistent with the therapeutic outcomes. First, in the purine metabolism pathway, CF treatment was associated with a downregulation of serum hypoxanthine and xanthine levels. As these metabolites serve as direct substrates for uric acid generation, their reduction aligns with the observed decrease in serum UA and correlates with the inhibition of hepatic and serum XOD activity demonstrated in our enzymatic assays [30]. Second, regarding the arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism pathway [31], CF appeared to attenuate the accumulation of pro-inflammatory mediators, including arachidonic acid and leukotriene A4 (LTA4). Given the role of LTA4 as a chemotactic agent for immune cells, its downregulation is consistent with the histological observation of reduced inflammatory cell infiltration in renal tissues. Moreover, the modulation of metabolites such as phosphocholine and creatinine may reflect improvements in membrane phospholipid homeostasis and renal filtration function.

Transitioning from systemic metabolic regulation to the material basis, we focused on the constituents of CF absorbed into the blood, postulating them as the primary effectors in vivo. Through integrated bioinformatics and correlation analysis, androsin [32], cynaroside [33], and salicin [34,35] were identified as potential key bioactive candidates. Notably, our data proposes a novel “dual-inhibition” potential for these components. On one hand, molecular docking and in vitro enzymatic assays demonstrated that cynaroside and salicin bind deeply into the active pocket of XOD, directly inhibiting its activity; this interaction creates the molecular basis for the systemic reduction in purine metabolites (xanthine/hypoxanthine) and serum UA. On the other hand, these components were found to target the inflammatory axis by binding to COX-1 and PGE2. This was validated in BMDM cells, where the compounds significantly suppressed cytokine release (IL-1β, TNF-α), providing a cellular-level explanation for the alleviation of AA metabolism-driven renal inflammation.

Despite these promising findings, rigorous caution is warranted in interpreting the direct causality of specific components. While identifying androsin, cynaroside, and salicin as absorbed constituents provides a strong lead, their specific pharmacokinetic profiles—including bioavailability, half-life, and tissue distribution within the kidney—remain to be fully elucidated. Furthermore, although metabolomics highlighted the regulatory role of the AA pathway, the specific upstream molecular nodes (e.g., PLA2 activity or specific transporter expression) were not directly quantified in this study. Future investigations employing gene-knockout models or specific inhibitors are necessary to definitively validate the causal contribution of the COX-1/PGE2 pathway to CF-mediated renoprotection.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study provides preliminary evidence that CF exerts uric acid-lowering and renoprotective effects in hyperuricemic mice, potentially through modulating purine metabolism, arachidonic acid metabolism, and oxidative stress pathways. The integrated approach of functional evaluation, metabolomics, and bioinformatics identified androsin, cynaroside, and salicin as potential bioactive components, which may target COX-1, PGE2, and XOD to inhibit inflammation and UA production. These results validate the traditional use of CF as a dietary component for managing hyperuricemia and provide a scientific basis for its development into functional foods. Nevertheless, more rigorous studies are needed to refine our understanding of CF’s mechanisms and optimize its clinical application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/foods15010020/s1, Tables S1–S4. Parameter for chemical composition analysis of CF and serum. Tables S5–S8. Parameter for untargeted metabolomics analysis. Table S9. Differential metabolites in mouse serum metabolomics. Table S10. Criteria for renal histopathological scoring. Table S11. The grid box parameters. Figure S1. Base peak ions chromatogram of Incoming blood components detected in positive and negative mode. Figure S2. The chromatograms of serum metabolomics. A: representative chromatograms of CF samples in positive ion mode. B: Representative chromatograms of the negative ion patterns of CF samples. Figure S3. OPLS-DA analysis of non-targeted metabolomics of mouse serum and validation results. A: OPLS-DA score plots and validation diagrams (positive ions). B: OPLS-DA score plots and validation diagrams (negative ions). Figure S4. Molecular docking visualizations of positive control drugs with their respective targets. Figure S5. Cell viability of BMDM (A) and BRL3A (B) cells at different concentrations of androsin, cynaroside, and salicin.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, M.Z. and C.L.; Validation, M.Z. and H.Z.; Visualization, M.Z., C.L. and S.C.; Investigation, Y.Z., Z.Y., S.C. and H.Z.; Data curation, C.L. and M.Z.; Methodology, Z.Y. and C.L.; Writing—review and editing; X.H., Y.G., L.C. and Z.M.; Supervision, X.H., Z.M. and L.C.; Conceptualization, L.C. and Y.G.; Review project administration, Y.G.; Resources, Y.G.; Funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Key R&D Plan Project of Hubei Province (Grant number: 2025BBB011), the Fund for Academic Innovation Teams of South-Central Minzu University (Grant Number: XTZ24025) and Chinese Medicinal Materials Industrial Chain Project of Hubei province in 2025 (Grant Number: 2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by committee on research ethics and technology security, South-Central Minzu University (Approval No. 2022-scuec-057, 2 November 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CF | Chaenomeles Fructus | COX-1 | cyclooxygenase-1 |

| CF | Chaenomeles Fructus watery extract | XOD | xanthine oxidase |

| CRE | creatinine | PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| UA | uric acid | PO | potassium oxonate |

| GSH-Px | glutathione peroxidase | HX | hypoxanthine |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen | CMC-Na | sodium carboxymethyl cellulose |

| MDA | malondialdehyde | ALL | allopurinol |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase | CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide | MSU | Monosodium urate |

| BMDM | Bone marrow-derived macrophages | PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum | DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium |

| BRL3A | Buffalo Rat Liver-3A |

References

- Singh, J.A.; Cleveland, J.D. Gout Is Associated with a Higher Risk of Chronic Renal Disease in Older Adults: A Retrospective Cohort Study of U.S. Medicare Population. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.A.; Gaffo, A. Gout Epidemiology and Comorbidities. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020, 50, S11–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goarant, C.; Acharya, S. Gout Is a Neglected Non-Communicable Disease in the Pacific. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e550–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Xu, D.; Ding, X.-Q.; Kong, L.-D. Protection of Curcumin against Fructose-Induced Hyperuricaemia and Renal Endothelial Dysfunction Involves NO-Mediated JAK–STAT Signalling in Rats. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 2184–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Liu, F.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiong, J.; Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, P. Associations between Dietary Patterns and Serum Uric Acid Concentrations in Children and Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 9803–9814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Liu, T.; Ju, H.; Xia, Y.; Ji, C.; Zhao, Y. Association between Dietary Patterns and Chronic Kidney Disease Combined with Hyperuricemia. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Wu, G.; Liu, S. Comparative Metabolomics Study of Chaenomeles Speciosa (Sweet) Nakai from Different Geographical Regions. Foods 2022, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, C.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, W. Active Compounds, Antioxidant Activity and α -Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of Different Varieties of Chaenomeles Fruits. Food Chem. 2018, 248, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Li, S.; Zhu, Z.; He, J. Recent Advances in Valorization of Chaenomeles Fruit: A Review of Botanical Profile, Phytochemistry, Advanced Extraction Technologies and Bioactivities. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y.-X.; Liu, A.-L.; Wang, H.-D.; Wang, Y.-L.; Du, G.-H. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Influenza Properties of Components from Chaenomeles Speciosa. Molecules 2010, 15, 8507–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Zhong, P.-X.; Xu, Y.-J.; Li, C.-H.; Ji, K.-X.; Wang, L.-S. Polyphenols and Triterpenes from Chaenomeles Fruits: Chemical Analysis and Antioxidant Activities Assessment. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 4260–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wei, W. Effects and Mechanisms of Glucosides of Chaenomeles Speciosa on Collagen-Induced Arthritis in Rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2003, 3, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Sun, H.; Wang, X. Mass Spectrometry-driven Drug Discovery for Development of Herbal Medicine. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2018, 37, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ji, S.; Peng, B.; Lu, H.; He, Q.; Bi, J.; Kwan, H.Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Simiao Pills Alleviates Renal Injury Associated with Hyperuricemia: A Multi-Omics Analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 333, 118492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ansari, A.; Gupta, J.; Singh, H.; Jagavelu, K.; Sashidhara, K.V. Androsin Alleviates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Activating Autophagy and Attenuating de Novo Lipogenesis. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Wu, K.; Mo, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhou, P.; Lan, T. Establishment and Optimization of a Novel Mouse Model of Hyperuricemic Nephropathy. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2427181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.; Shen, Y.; Su, E.; Du, L.; Xie, J.; Wei, D. Anti-Hyperuricemic, Nephroprotective, and Gut Microbiota Regulative Effects of Separated Hydrolysate of α-Lactalbumin on Potassium Oxonate- and Hypoxanthine-Induced Hyperuricemic Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, 2200162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.-L.; Gao, Y.-Y.; Yang, Y.-X.; Zhu, Q.-F.; Guan, H.-Y.; He, X.; Zhang, C.-L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G.-B.; Zou, S.-H.; et al. Amelioration Effects of α-Viniferin on Hyperuricemia and Hyperuricemia-Induced Kidney Injury in Mice. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Lu, F.; Liu, S. Investigating the Mechanisms of Resveratrol in the Treatment of Gouty Arthritis through the Integration of Network Pharmacology and Metabolics. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1438405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Fang, Y.; Yu, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Xia, D. The Flavonoid-Rich Fraction from Rhizomes of Smilax Glabra Roxb. Ameliorates Renal Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Uric Acid Nephropathy Rats through Promoting Uric Acid Excretion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, C.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Johnson, R.J.; Kielstein, J.T.; Lurbe, E.; Mancia, G.; Redon, J.; Stack, A.G.; Tsioufis, K.P. Hyperuricaemia and Gout in Cardiovascular, Metabolic and Kidney Disease. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 80, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gois, P.H.F.; Souza, E.R.D.M. Pharmacotherapy for Hyperuricaemia in Hypertensive Patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD008652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K.; Kubo, A.; Miyashita, K.; Sato, M.; Hagiwara, A.; Inoue, H.; Ryuzaki, M.; Tamaki, M.; Hishiki, T.; Hayakawa, N.; et al. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitor Ameliorates Postischemic Renal Injury in Mice by Promoting Resynthesis of Adenine Nucleotides. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e124816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Jiang, W.; Xu, Y.; Gao, M.; Shen, G.; Liu, Y.; Ling, N.; Cui, L. Diverse Development Approaches for Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors: Synthetic Chemistry, Natural Product Chemistry, and Drug Repositioning. CMC 2025, 32, e09298673384402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathallah-Shaykh, S.A.; Cramer, M.T. Uric Acid and the Kidney. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2014, 29, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Turkiewicz, I.P.; Tkacz, K.; Hernandez, F. Comparison of Bioactive Compounds and Health Promoting Properties of Fruits and Leaves of Apple, Pear and Quince. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Cui, H.; Xu, W.; He, Y.; Ma, H.; Gao, R. Effect of Oral Administration of Collagen Hydrolysates from Nile Tilapia on the Chronologically Aged Skin. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 44, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, L.K.; Chapman, P.T. Allopurinol Hypersensitivity: Pathogenesis and Prevention. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 34, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, L.K.; Dalbeth, N. What Is Allopurinol Failure and What Should We Do About It? J. Rheumatol. 2024, 51, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lü, J.-M.; Yao, Q. Hyperuricemia-Related Diseases and Xanthine Oxidoreductase (XOR) Inhibitors: An Overview. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 2501–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wu, L.; Chen, J.; Dong, L.; Chen, C.; Wen, Z.; Hu, J.; Fleming, I.; Wang, D.W. Metabolism Pathways of Arachidonic Acids: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, W.; Stuppner, H.; Wagner, H.; Gropp, M.; Demoulin, S.; Ring, J. Antiasthmatic effects of Picrorhiza kurroa: Androsin prevents allergen- and PAF-induced bronchial obstruction in guinea pigs. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1991, 95, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ye, W.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, Z. Cynaroside Improved Depressive-like Behavior in CUMS Mice by Suppressing Microglial Inflammation and Ferroptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 173, 116425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Lv, H.; Qiu, J.; Chi, G.; Feng, H. D(−)-Salicin Inhibits the LPS-Induced Inflammation in RAW264.7 Cells and Mouse Models. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 26, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, K.; Duan, H.; Khan, G.J.; Xu, H.; Han, F.; Cao, W.; Gao, G.; Shan, L.; Wei, Z.-J. Salicin from Alangium Chinense Ameliorates Rheumatoid Arthritis by Modulating the Nrf2-HO-1-ROS Pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6073–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.