The Use of Local Ingredients in Shaping Tourist Experience: The Case of Allium ursinum and Revisit Intention in Rural Destinations of Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

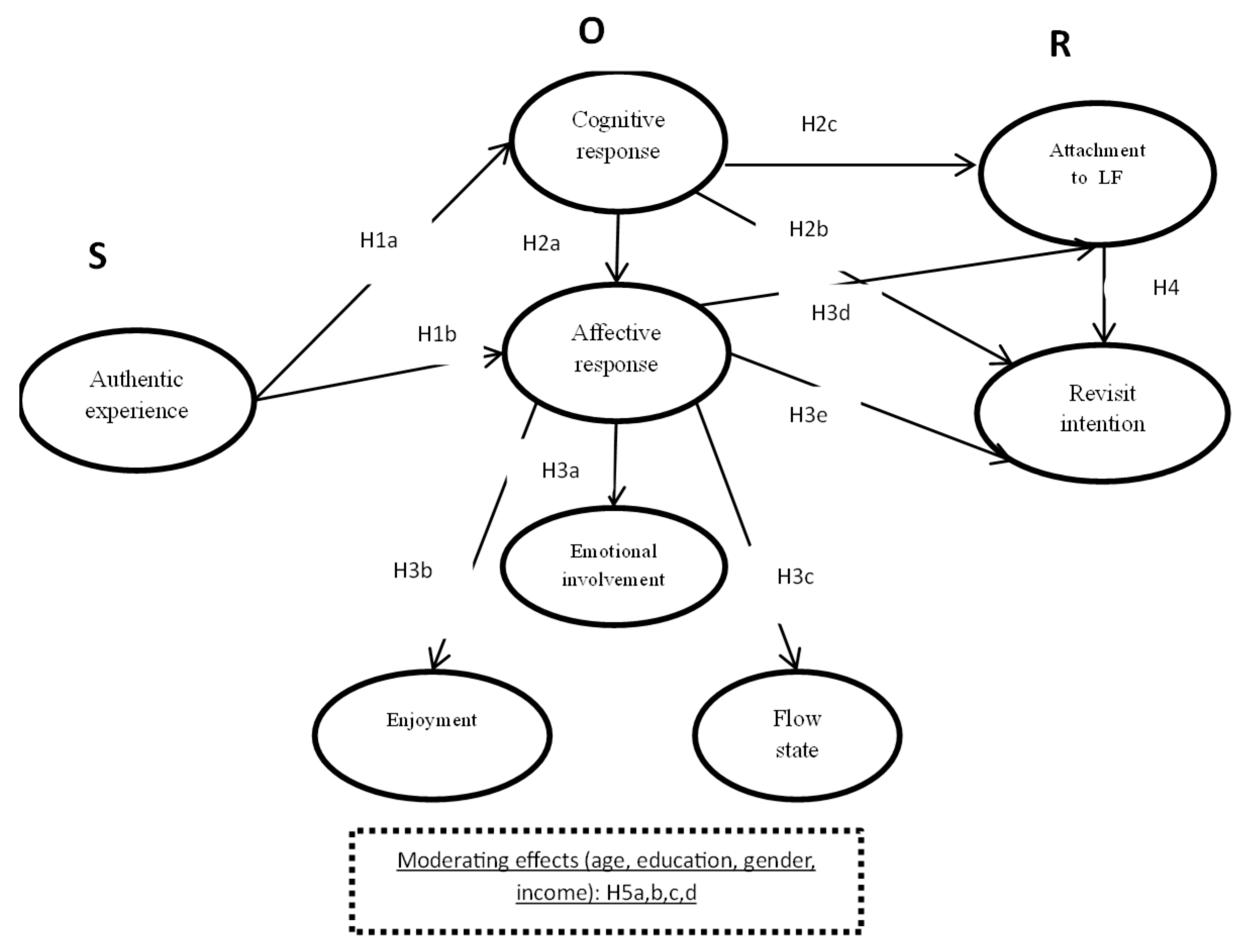

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Formulation

- Stimulus (S): Authentic experience

- Organism (O): Cognitive and affective responses

- Response (R): Behavioral intentions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Questionnaire Design

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

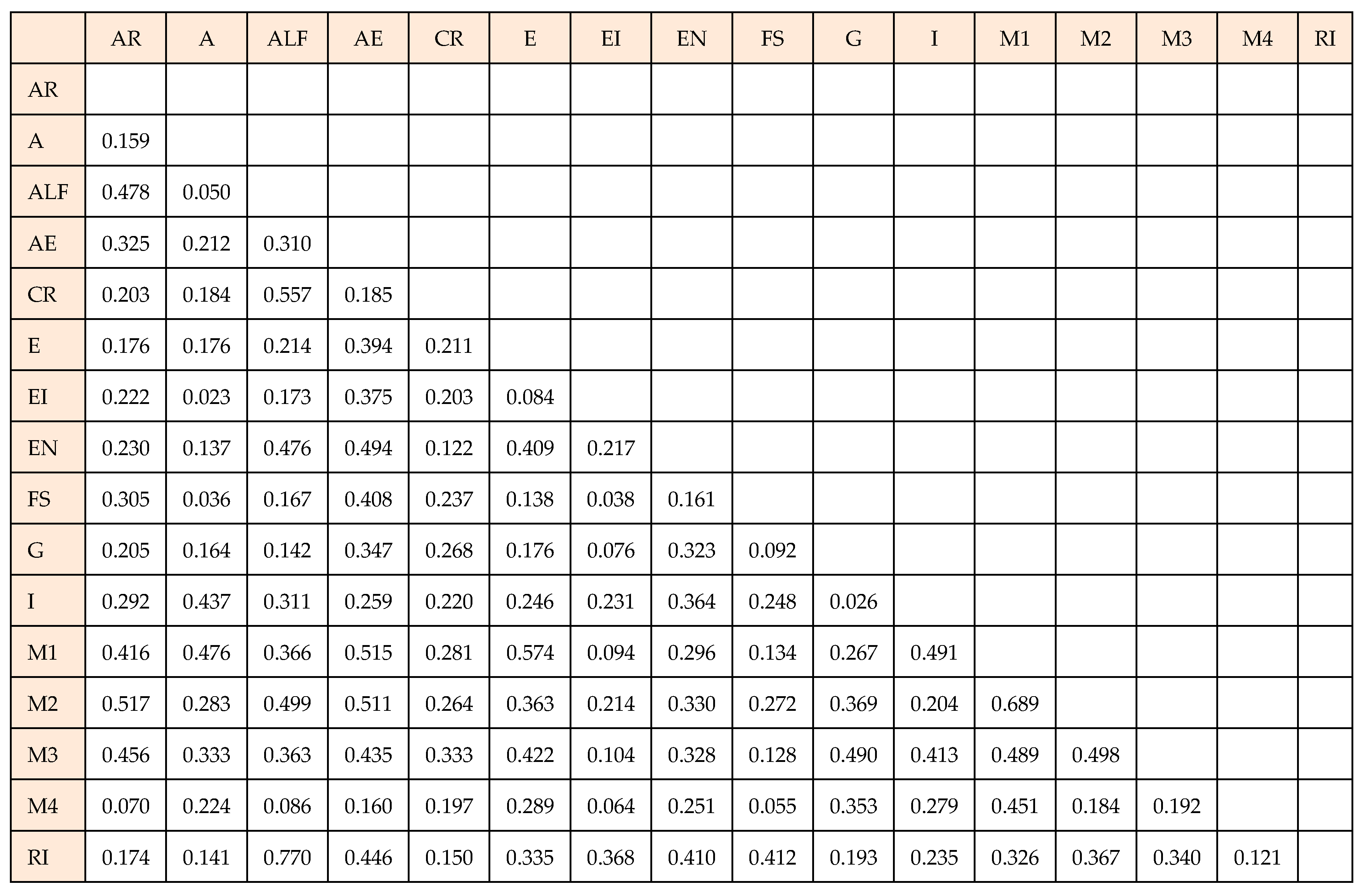

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Factor Analysis of the Construct

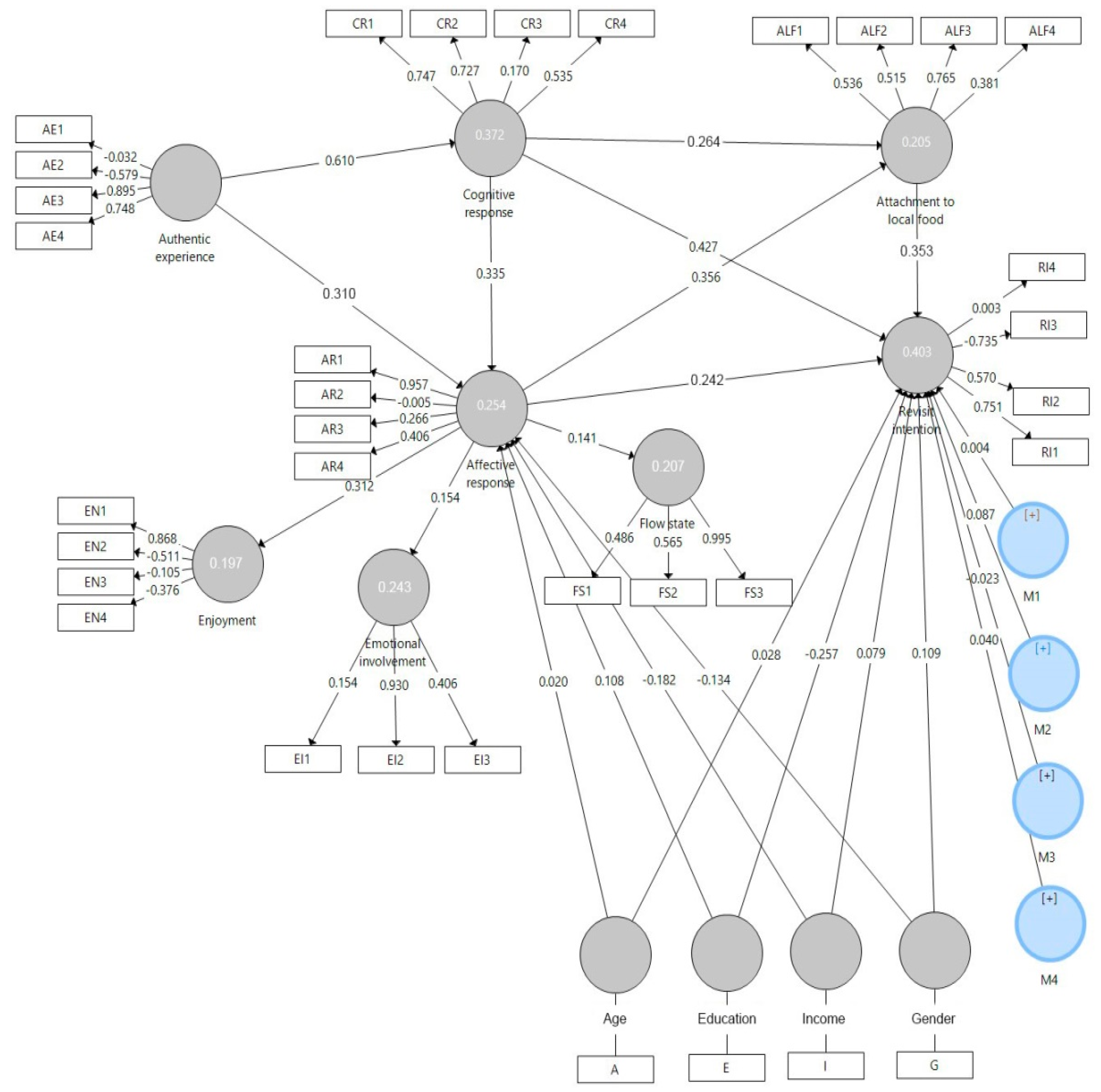

3.2. Results of the SEM Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chin, W.L.; Musa, S.F.P.D. Exploring the potential of community-based agritourism in Brunei Darussalam. In Brunei Darussalam’s Economic Transition in a Shifting Global Asia; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tërpollari, A.; Hoxha, E.; Domi, S. The identification and importance of local and traditional food offered by tourist businesses in Shkodra lake area. Eur. J. Econ. 2025, 9, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, K.V. A gastronomic journey through food courts: Exploring culinary diversity, flavours, and cultural fusion experiences. Int. J. Interdiscip. Multidiscip. Stud. 2025, 1, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Vafadari, K.; Khoshkam, M.; Yotsumoto, Y.; Bielik, P.; Ferraris, A. Determinants of resilience in local food systems: Insights from world agriculture heritage sites. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 950–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, L.R.; Rashid, S.; Sharma, D.; Majeed, L.F.; Bhat, M.A. Nature conservation and poverty alleviation through sustainable ecotourism: The case of Lolab Valley, India. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz-Martínez, N. Extending actor engagement: Human–environmental engagement in multilevel socioecological systems. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2025, 35, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, C. Specific dietary considerations for the food tourist. In The Food Tourist (The Tourist Experience); Fusté-Forné, F., Wolf, E., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2025; pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzinger, N.; Dean, D. (Eds.) Vanilla production in the context of culture, economics, and ecology of Belize. In Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Di-Clemente, E.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Campón-Cerro, A.M. Olive oil tourism: State of the art. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 25, 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H. Spear Thistle (Cirsium vulgare L.) and Ramsons (Allium ursinum L.), Impressive Health Benefits and High-Nutrient Medicinal Plants. Phcog. Commn. 2021, 11, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, S. Herbs as Functional Foods. In Functional Foods: Sources & Health Benefits; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 141–165. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320735359_Herbs_as_Functional_Foods (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Gordanić, S.V.; Kostić, A.Ž.; Krstić, Đ.; Vuković, S.; Kilibarda, S.; Marković, T.; Moravčević, Đ. A detailed survey of agroecological status of Allium ursinum across the Republic of Serbia: Mineral composition and bioaccumulation potential. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipčev, B.; Kojić, J.; Miljanić, J.; Šimurina, O.; Stupar, A.; Škrobot, D.; Travičić, V.; Pojić, M. Wild Garlic (Allium ursinum) Preparations in the Design of Novel Functional Pasta. Foods 2023, 12, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazewicz-Wozniak, M.; Kesik, T.; Michowska, A.E. The growth, flowering and chemical composition of leaves of three ecotypes of Allium ursinum L. Acta Agrobot. 2011, 64, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.S.; Imran, M.; Khan, M.K.; Ahmad, M.H.; Arshad, M.S.; Ateeq, H.; Rahim, M.A. Introductory Chapter: Herbs and Spices—An Overview. In Herbs and Spices: New Processing Technologies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokou, D.; Kokkini, S.; Bessiere, J.M. Geographic variation of Greek oregano (Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum) essential oils. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1993, 21, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arraiza, M.P.; Andrés, M.P.; Arrabal, C.; López, J.V. Seasonal Variation of Essential Oil Yield and Composition of Thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) Grown in Castilla—La Mancha (Central Spain). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2009, 21, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, G.; Panagopoulos, G.; Tarantilis, P.; Kalivas, D.; Kotoulas, V.; Travlos, I.S.; Polysiou, M.; Karamanos, A. Variability in essential oil content and composition of Origanum hirtum L., Origanum onites L., Coridothymus capitatus (L.) and Satureja thymbra L. populations from the Greek island Ikaria. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov Raljić, J.; Blešić, I.; Ivkov, M.; Petrović, D.M.; Gajić, T.; Aleksić, M. Functional Handmade Minions Consumers and Experienced Tasters Sensory Evaluation of the new Product. Acta Period. Technol. 2021, 52, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugarčić, J.; Cvijanović, D.; Vukolić, D.; Zrnić, M.; Gajić, T. Gastronomy as an effective tool for rural prosperity—Evidence from rural settlements in Republic of Serbia. Econ. Agric. 2023, 70, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, C.; Bakshi, U.; Mallick, I.; Mukherji, S.; Bera, B.; Ghosh, A. Genome-guided insights into the plant growth promotion capabilities of the physiologically versatile Bacillus aryabhattai Strain AB211. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar, A.; Vidović, S.; Vladić, J.; Radusin, T.; Mišan, A. A Sustainable Approach for Enhancing Stability and Bioactivity of Allium ursinum Extract for Food Additive Applications. Separations 2024, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar, A.; Kevrešan, Ž.; Bajić, A.; Tomić, J.; Radusin, T.; Travičić, V.; Mastilović, J. Enhanced Preservation of Bioactives in Wild Garlic (Allium ursinum L.) through Advanced Primary Processing. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, S.; Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Oszmiański, J.; Wiśniewski, R. Comparison of phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of bear garlic (Allium ursinum L.) in different maturity stages. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voća, S.; Šic Žlabur, J.; Fabek Uher, S.; Peša, M.; Opačić, N.; Radman, S. Neglected Potential of Wild Garlic (Allium ursinum L.)—Specialized Metabolites Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Wild Populations in Relation to Location and Plant Phenophase. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadway, M.J. ‘Putting Place on a Plate’ along the West Cork Food Trail. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, M.; Sundbo, D.; Sundbo, J. Local food and tourism: An entrepreneurial network approach. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritts, J.R.; Fort, C.; Corr, A.Q.; Liang, Q.; Alla, L.; Cravener, T.; Hayes, J.E.; Rolls, B.J.; D’Adamo, C.; Keller, K.L. Herbs and spices increase liking and preference for vegetables among rural high school students. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, G. Feeding the rural tourism strategy? Food and notions of place and identity. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 223–238. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:154448032 (accessed on 1 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Radovanović, M.; Tretiakova, T.; Syromiatnikova, J. Creating brand confidence to gastronomic consumers through social networks—A report from Novi Sad. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2020, 14, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.A.; Lorenzo-Cuyás, D. The ‘social heroes’ approach as a methodology for valorising the primary sector and promoting local products. A pilot study in Lanzarote, Canary Islands. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 39, 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkić, J.; Filep, S.; Taylor, S. Shaping tourists’ wellbeing through guided slow adventures. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 2064–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydar, H.; Sağdıç, O.; Özkan, G.; Karadoğan, T. Antibacterial activity and composition of essential oils from Origanum, Thymbra and Satureja species with commercial importance in Turkey. Food Control 2004, 15, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Gajić, T.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A.; Radovanović, M.; Popov-Raljić, J.; Yakovenko, N.V. How the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Can be Applied in the Research of the Influencing Factors of Food Waste in Restaurants: Learning from Serbian Urban Centers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić-Obrdalj, H.; Keser, I.; Ranilović, J.; Palfi, M.; Gajari, D.; Cvetković, T. The use of herbs and spices in sodium-reduced meals enhances saltiness and is highly accepted by the elderly. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 105, 104789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gođevac, D.; Vujisić, L.; Mojović, M.; Ignjatović, A.; Spasojević, I.; Vajs, V. Evaluation of antioxidant capacity of Allium ursinum L. volatile oil and its effect on membrane fluidity. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukolić, D.; Gajić, T.; Petrović, M.D.; Bugarčić, J.; Spasojević, A.; Veljović, S.; Vuksanović, N.; Bugarčić, M.; Zrnić, M.; Knežević, S.; et al. Development of the Concept of Sustainable Agro-Tourism Destinations—Exploring the Motivations of Serbian Gastro-Tourists. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kæsik, T.; Bùaýewicz-Woêniak, M.; Michowska, A.E. Influence of mulching and nitrogen nutrition on bear garlic (Allium ursinum L.) growth. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2011, 10, 221–223. [Google Scholar]

- Gajić, T.; Raljic, J.P.; Blešic, I.; Aleksic, M.; Petrovic, M.D.; Radovanovic, M.M.; Vukovic, D.B.; Sikimic, V.; Pivac, T.; Kostic, M.; et al. Factors That Influence Sustainable Selection and Reselection Intentions Regarding Soluble/Instant Coffee—The Case of Serbian Consumers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, M.; Ristić, L.; Bošković, N. Rural tourism as a driver of the economic and rural development in the Republic of Serbia. Hotel Tour. Manag. 2022, 10, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Widyanta, A. Food tourism experience and changing destination foodscape: An exploratory study of an emerging food destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 42, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, S.; Popović-Djordjević, J.B.; Kostić, A.Ž.; Pantelić, N.D.; Srećković, N.; Akram, M.; Laila, U.; Katanić Stanković, J.S. Allium Species in the Balkan Region—Major Metabolites, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurdjevic, L.; Dinic, A.; Pavlovic, P.; Mitrovic, M.; Karadzic, B.; Tesevic, V. Allelopathic potential of Allium ursinum L. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2004, 32, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiralova, A.; Hamarneh, I. Local gastronomy as a prerequisite of food tourism development in the Czech Republic. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2017, 2, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastaki, S.M.; Ojha, S.; Kalasz, H.; Adeghate, E. Chemical constituents and medicinal properties of Allium species. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 4301–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1974-22049-000 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus–Organism–Response Reconsidered: An Evolutionary Step in Modeling (Consumer) Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisavljević, N.; Soković Bajić, S.; Jovanović, Ž.; Matić, I.; Tolinački, M.; Popović, D.; Popović, N.; Terzić-Vidojević, A.; Golić, N.; Beškoski, V.; et al. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of Allium ursinum and their associated microbiota during simulated in vitro digestion in the presence of food matrix. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 601616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, T.K.; Major, N.; Sivec, M.; Horvat, D.; Krpan, M.; Hruškar, M.; Ban, D.; Išić, N.; Goreta Ban, S. Phenolic content, amino acids, volatile compounds, antioxidant capacity, and their relationship in wild garlic (A. ursinum L.). Foods 2023, 12, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.; Waheed, U.; Ahmad, M.; Javed, W. Phytochemistry of Allium cepa L. (Onion): An overview of its nutritional and pharmacological importance. Sci. Inq. Rev. 2021, 5, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Hsu, Y.L. Authentic experiences and support for sustainable development: Applications at two cultural tourism destinations in Taiwan. Leis. Sci. 2025, 47, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medail, F.; Quezel, P. Hot-spots analysis for conservation of plant biodiversity in the Mediterranean basin. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1997, 84, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachão, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Food tourism and regional development: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Lukić, D.; Radovanović, M.M.; Blešić, I.; Gajić, T.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Syromiatnikova, J.A.; Miljković, Đ.; Kovačić, S.; Kostić, M. How Can Tufa Deposits Contribute to the Geotourism Offer? The Outcomes from the First UNESCO Global Geopark in Serbia. Land 2023, 12, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokom, R.; Widjaja, D.C.; Kristanti, M.; Wijaya, S. Culinary and destination experiences on behavioral intentions: An insight into local Indonesian food. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2023, 28, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Y. Assessing the impact of community-based homestay experiences on tourist loyalty in sustainable rural tourism development. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mata, D.; Morales, R. The Mediterranean Landscape and Wild Edible Plants. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Sánchez-Mata, M., Tardío, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanţa, L.C.; Tofana, M.; Socaci, S.; Pop, C.; Pop, A.; Nagy, M. Evaluation of Physicochemical Properties and Antioxidant Capacity of Pepper Sauce with Allium ursinum L. Bull. UASVM Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobolewska, D.; Podolak, I.; Makowska-Wąs, J. Allium ursinum: Botanical, phytochemical and pharmacological overview. Phytochem. Rev. 2013, 14, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Xia, F.; Fu, X. The mechanism of stimulating resident tourists’ place attachment via festivals. J. China Tour. Res. 2025, 21, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanaki, A.; van Andel, T. Mediterranean aromatic herbs and their culinary use. In Aromatic Herbs in Food; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litianingsih, N.; Mariam, I.; Chandra, Y.E.N.; Pratama, A.P. Empowering Leuwimalang Village through digital platform to optimizing potential tourism destination. J. Sci. 2025, 2, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Atham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning, EMEA Cheriton House: Hampshire, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.drnishikantjha.com/papersCollection/Multivariate%20Data%20Analysis.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G. Experimental Designs Using ANOVA. Duxbury: 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259465542_Experimental_Designs_Using_ANOVA (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Williams, L.J.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, J.; Kim, M.-J.; Ryu, K. Does Perceived Restaurant Food Healthiness Matter? Its Influence on Value, Satisfaction and Revisit Intentions in Restaurant Operations in South Korea. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, N.; Zocchi, D.M.; Bonafede, S.; Nanni, C.; Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. Going or Returning to Nature? Wild Vegetable Uses in the Foraging-Centered Restaurants of Lombardy, Northern Italy. Plants 2024, 13, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubičková, V.; Kubíková, L.; Dudić, B.; Premović, J. The influence of motivators on responsible consumption in tourism. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2024, 74, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziekański, P.; Popławski, Ł.; Popławska, J. Interaction Between Pro-Environmental Spending and Environ-mental Conditions and Development. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2024, 74, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirović, D.; Petrović, M.D.; Neto Monteiro, L.C.; Stjepanović, S. An Examination of Competitiveness of Rural Destinations from the Supply Side Perspective. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2016, 66, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 140 (41.7%) |

| Female | 196 (58.3%) | |

| Age | 18–29 years | 82 (24.4%) |

| 30–44 years | 128 (38.1%) | |

| 45–59 years | 92 (27.4%) | |

| 60+ years | 34 (10.1%) | |

| Country of origin | Serbia | 214 (63.7%) |

| Germany | 42 (12.5%) | |

| Hungary | 28 (8.3%) | |

| Austria | 18 (5.4%) | |

| Slovenia | 14 (4.2%) | |

| Others (Italy, Czech Republic, Slovakia) | 20 (5.9%) | |

| Place of residence | Urban | 242 (72.1%) |

| Rural | 94 (27.9%) | |

| Education | Secondary education | 98 (29.2%) |

| Higher education (BA/MA/PhD) | 238 (70.8%) | |

| Monthly income | Below average (EUR <600) | 116 (34.5%) |

| Average (EUR 600–900) | 146 (43.5%) | |

| Above average (EUR >900) | 74 (22.0%) |

| Factor | Statement | m | sd | α | FA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic experience | Allium ursinum in local food provided me with authentic experiences. | 3.76 | 1.054 | 0.647 | 0.884 |

| m = 3.88, sd = 1.131 α = 0.992 CR = 0.894, AVE = 0.678 Eigenvalues—5.453 Variance explained—18.176 | Allium ursinum in local food provided me with genuine experiences. | 4.18 | 0.887 | 0.653 | 0.830 |

| Allium ursinum in local food provided me with exceptional experiences. | 3.69 | 1.380 | 0.666 | 0.827 | |

| Allium ursinum in local food provided me with unique experiences. | 3.90 | 1.203 | 0.670 | 0.746 | |

| Cognitive response | Allium ursinum in local food helps me gain knowledge about local traditions. | 3.90 | 0.976 | 0.687 | 0.825 |

| m = 4.28, sd = 0.911 α = 0.960 CR = 0.861, AVE = 0.610 Eigenvalues—3.644 Variance explained—12.147 | Allium ursinum in local food is beneficial for my health. | 4.19 | 1.140 | 0.699 | 0.823 |

| Allium ursinum in local food is useful for expanding culinary knowledge. | 4.57 | 0.725 | 0.701 | 0.794 | |

| Allium ursinum in local food allows me to form friendships with other food enthusiasts. | 4.49 | 0.805 | 0.710 | 0.669 | |

| Enjoyment | Allium ursinum in local food is enjoyable for me. | 4.66 | 0.650 | 0.720 | 0.803 |

| m = 4.75, sd = 0.758 α = 0.955 CR = 0.865, AVE = 0.617 Eigenvalues—2.106 Variance explained—7.020 | Allium ursinum in local food provides me with satisfaction. | 4.43 | 0.975 | 0.735 | 0.799 |

| Allium ursinum in local food is fun for me. | 4.66 | 0.636 | 0.747 | 0.795 | |

| Allium ursinum in local food makes me happy. | 4.55 | 0.732 | 0.758 | 0.744 | |

| Affective response | Allium ursinum in local food evokes positive emotions in me. | 4.22 | 1.221 | 0.763 | 0.629 |

| m = 4.61, sd = 0.672 α = 0.800 CR = 0.837, AVE = 0.564 Eigenvalues—1.686 Variance explained—5.619 | Allium ursinum in local food makes me feel happy and satisfied. | 4.88 | 0.322 | 0.770 | 0.833 |

| Allium ursinum in local food makes me emotionally attached to local customs. | 4.54 | 0.730 | 0.780 | 0.781 | |

| Allium ursinum in local food provides me with a sense of connection to the culture. | 4.83 | 0.417 | 0.799 | 0.744 | |

| Emotional involvement | I am fully engaged in the experience of using Allium ursinum in local food. | 4.36 | 1.033 | 0.800 | 0.700 |

| m = 4.32; sd = 1.028 α = 0.987 CR = 0.855, AVE = 0.663 Eigenvalues—1.584 Variance explained—5.281 | I am deeply impressed by the use of Allium ursinum in local food. | 4.30 | 1.024 | 0.810 | 0.680 |

| I feel complete empathy towards experiences related to Allium ursinum in local food. | 4.30 | 1.027 | 0.822 | 0.720 | |

| Flow state | When enjoying local food with Allium ursinum, I feel completely absorbed. | 4.24 | 1.038 | 0.836 | 0.710 |

| m = 4.27, sd = 1.033 α = 0.971 CR = 0.802, AVE = 0.577 Eigenvalues—1.407 Variance explained—4.689 | When enjoying local food with Allium ursinum, time flies by quickly. | 4.27 | 1.029 | 0.845 | 0.690 |

| When enjoying local food with Allium ursinum, I forget all my worries. | 4.30 | 1.024 | 0.850 | 0.680 | |

| Attachment to Local Food | I am closely connected to the experiences of using Allium ursinum in local food. | 4.28 | 1.028 | 0.869 | 0.750 |

| m = 3.40, sd = 1.129 α = 0.901 CR = 0.839, AVE = 0.569 Eigenvalues—1.285 Variance explained—4.283 | Using Allium ursinum in local food is part of my life. | 4.22 | 1.042 | 0.874 | 0.770 |

| I am attached to the use of Allium ursinum in local food. | 2.78 | 1.068 | 0.880 | 0.760 | |

| Using Allium ursinum in local food is important to me. | 2.34 | 1.378 | 0.895 | 0.780 | |

| Revisit intention | I want to explore destinations where Allium ursinum is used in local cuisine. | 3.90 | 1.315 | 0.901 | 0.800 |

| m = 3.73, sd = 1.163 α = 0.875 CR = 0.872, AVE = 0.632 Eigenvalues—1.174 Variance explained—3.914 | I am attracted to places where I can try dishes with Allium ursinum. | 2.93 | 1.112 | 0.983 | 0.820 |

| I plan to visit restaurants that offer specialties with Allium ursinum. | 3.60 | 1.463 | 0.924 | 0.840 | |

| I am interested in visiting destinations where Allium ursinum is a key ingredient in dishes. | 4.49 | 0.764 | 0.930 | 0.860 |

| α | rho_A | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective response | 0.976 | 0.804 | 0.880 | 0.688 |

| Age | 0.080 | 0.822 | 0.900 | 0.600 |

| Attachment to local food | 0.868 | 0.824 | 0.840 | 0.621 |

| Authentic experience | 0.983 | 0.849 | 0.816 | 0.624 |

| Cognitive response | 0.916 | 0.842 | 0.846 | 0.651 |

| Education | 0.920 | 0.847 | 0.903 | 0.674 |

| Emotional involvement | 0.895 | 0.897 | 0.833 | 0.551 |

| Enjoyment | 0.810 | 0.863 | 0.935 | 0.592 |

| Flow state | 0.879 | 0.875 | 0.842 | 0.615 |

| Gender | 0.917 | 0.833 | 0.817 | 0.599 |

| Income | 0.945 | 0.852 | 0.919 | 0.618 |

| M1 | 0.874 | 0.800 | 0.905 | 0.644 |

| M2 | 0.866 | 0.894 | 0.855 | 0.629 |

| M3 | 0.769 | 0.888 | 0.830 | 0.607 |

| M4 | 0.745 | 0.805 | 0.955 | 0.668 |

| Revisit intention | 0.830 | 0.868 | 0.819 | 0.658 |

| Constructs | AIC | AICu | AICc | BIC | HQ | HQc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective response | −131.797 | −124.747 | −110.200 | −102.380 | −120.248 | −119.774 |

| Attachment to local food | −108.629 | −105.620 | −96.500 | −96.022 | −103.679 | −103.567 |

| Cognitive response | −227.159 | −225.155 | −218.500 | −218.754 | −223.860 | −223.800 |

| Emotional involvement | −27.823 | −25.819 | −20.500 | −18.418 | −25.523 | −25.463 |

| Enjoyment | −47.609 | −45.605 | −40.500 | −39.204 | −44.309 | −44.249 |

| Flow state | −26.908 | −24.904 | −23.500 | −21.497 | −23.609 | −23.549 |

| Revisit intention | −231.860 | −219.712 | −210.500 | −181.429 | −212.061 | −210.783 |

| Path | Effect | m | sd | t | p | Confirmation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective response → Attachment to local food | 0.356 | 0.356 | 0.045 | 7.930 | 0.000 | H3d | ✔ |

| Affective response → Emotional involvement | 0.154 | 0.076 | 0.148 | 1.038 | 0.030 | H3a | ✔ |

| Affective response → Enjoyment | 0.312 | 0.223 | 0.240 | 1.298 | 0.005 | H3b | ✔ |

| Affective response → Flow state | 0.141 | 0.112 | 0.118 | 1.197 | 0.032 | H3c | ✔ |

| Affective response → Revisit intention | 0.242 | 0.137 | 0.070 | 2.033 | 0.023 | H3e | ✔ |

| Attachment to local food → Revisit intention | 0.353 | 0.152 | 0.069 | 2.218 | 0.027 | H4 | ✔ |

| Authentic experience → Affective response | 0.310 | 0.164 | 0.053 | 3.055 | 0.002 | H1a | ✔ |

| Authentic experience → Cognitive response | 0.610 | 0.612 | 0.028 | 21.756 | 0.000 | H1b | ✔ |

| Cognitive response → Affective response | 0.335 | 0.334 | 0.061 | 5.534 | 0.000 | H2a | ✔ |

| Cognitive response → Attachment to local food | 0.264 | 0.168 | 0.040 | 4.086 | 0.000 | H2c | ✔ |

| Cognitive response → Revisit intention | 0.427 | 0.405 | 0.138 | 3.091 | 0.002 | H2b | ✔ |

| Affective response → (M1) → Revisit intention | 0.004 | −0.002 | 0.154 | 0.026 | 0.979 | H5c | X |

| Affective response → (M2) → Revisit intention | 0.087 | 0.077 | 0.073 | 1.199 | 0.231 | H5d | X |

| Affective response → (M3) → Revisit intention | −0.023 | −0.019 | 0.101 | 0.226 | 0.821 | H5b | X |

| Affective response → (M4) → Revisit intention | 0.040 | 0.040 | 0.051 | 0.785 | 0.433 | H5a | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gajić, T.; Veljović, S.P.; Petrović, M.D.; Blešić, I.; Radovanović, M.M.; Malinović Milićević, S.; Milanović Pešić, A.; Issakov, Y.; Khamitova, D.M. The Use of Local Ingredients in Shaping Tourist Experience: The Case of Allium ursinum and Revisit Intention in Rural Destinations of Serbia. Foods 2025, 14, 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091527

Gajić T, Veljović SP, Petrović MD, Blešić I, Radovanović MM, Malinović Milićević S, Milanović Pešić A, Issakov Y, Khamitova DM. The Use of Local Ingredients in Shaping Tourist Experience: The Case of Allium ursinum and Revisit Intention in Rural Destinations of Serbia. Foods. 2025; 14(9):1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091527

Chicago/Turabian StyleGajić, Tamara, Sonja P. Veljović, Marko D. Petrović, Ivana Blešić, Milan M. Radovanović, Slavica Malinović Milićević, Ana Milanović Pešić, Yerlan Issakov, and Dariga M. Khamitova. 2025. "The Use of Local Ingredients in Shaping Tourist Experience: The Case of Allium ursinum and Revisit Intention in Rural Destinations of Serbia" Foods 14, no. 9: 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091527

APA StyleGajić, T., Veljović, S. P., Petrović, M. D., Blešić, I., Radovanović, M. M., Malinović Milićević, S., Milanović Pešić, A., Issakov, Y., & Khamitova, D. M. (2025). The Use of Local Ingredients in Shaping Tourist Experience: The Case of Allium ursinum and Revisit Intention in Rural Destinations of Serbia. Foods, 14(9), 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091527