Abstract

This paper investigated the effects of agroforestry (AF) on the sensory profiles of cocoa beans and the organoleptic quality of end-chocolates. A three-day opening delay for the Ivorian hybrid cultivar commonly known as “Mercedes” (Amelonado × West African Trinitario) from AF and full-sun (FS) plantations as control located at five cocoa-producing areas were fermented in wooden boxes for 6 days and stirred at days 2 and 4. Fermented cocoa was sun-dried until reaching 7–8% moisture and processed into chocolate. Volatile compounds of cocoa powder and chocolate were analyzed using the SPME-GC-MS method, while the organoleptic perception of chocolates was assessed by 12 professional judges according to 10 sensory descriptors. The findings revealed that the concentrations of esters ranged from 9.41 ± 0.61 to 19.35 ± 1.28 µg.g−1, aldehydes from 11.56 ± 0.7 to 25.33 ± 1.5 µg.g−1, and ketones from 5.76 ± 0.62 to 55.84 ± 4.39 µg.g−1 in cocoa beans regardless of the cropping system. However, the concentrations of some volatile compounds classes including alcohols, acids, and pyrazines were similar in AF and FS chocolate samples. AF system clearly influenced the volatile compound profiles of cocoa beans in only the Adzopé, Guibéroua, and Méagui regions without impacting those of the chocolates regardless of the geographical origin after fermentation and roasting. Furthermore, AF chocolate was not less appealing than the FS chocolate samples. So, AF system did not significantly influence the sensory perception of chocolate. AF can therefore be encouraged as a cropping system for cocoa cultivation to reduce deforestation and promote reforestation, ensuring the sustainability of cocoa.

1. Introduction

Cocoa beans and chocolate are known as luxury foods that provide an astringent taste and typical aroma [1]. Cocoa, a perennial crop highly cultivated only in the equatorial regions, holds significant economic importance in several countries including Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana [2], accounting for 70% of the cocoa international supply [3], providing incomes for 2 million farmers. Unfortunately, both countries are incriminated in deforestation while benefiting from cocoa production [4]. Cocoa bean is the main raw material for chocolate and other cocoa products [5]. Chocolate is one of the most consumed foods worldwide due to its unique sensory and sensory characteristics, resulting from the unique and fascinating cocoa sensory [6,7]. The quality parameters of the finished chocolate are strongly influenced by cocoa farmers’ farming practices at the start of the chocolate supply chain [8]. The chocolate’s sensory quality largely depends on the genotype, the soil quality, the microclimatic variables, as the primary postharvest processing and the industrial process of beans until obtaining chocolate, at which point the fermentation and the roasting are emphasized [6,9,10,11]. Various studies and surveys showed differences in the farming practices regarding cocoa growing between farmers within the same country [8]. However, several studies emphasize that the primary postharvest processing of cocoa, such as cocoa pod opening delay, fermentation, and drying carried out mainly by farmers, must target the production of specialty cocoa, and the processing conditions must be controlled by integrating the quality characteristics required by the chocolate market [6,9]. The postharvest processing of cocoa is mediated by dynamic biochemical reactions under the actions of successive microorganisms including yeasts, lactic acid bacteria, and acetic acid bacteria spontaneously inoculating cocoa pulp and producing ethanol and lactic and acetic acids [6,12]. Endogenous enzymes catalyze the production of peptides and amino acids from seed storage proteins [13], and the inversion of sucrose and the subsequent formation of reducing sugars occur [14]. The resulting metabolites from enzymatic reactions of proteolysis and hydrolysis of the biochemical seed components are volatile compound precursors [6,15]. Then, during roasting, these products interact through nonenzymatic browning Maillard reactions, leading to the generation of molecules including pyrazines, alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, and esters. In turn, these molecules are responsible for the final sensory notes comprising the chocolate sensory attributes, e.g., flowery, fruity, caramel, nutty, etc. [15]. Thus, the sensory profiles of cocoa beans and of chocolate depend on the biochemical composition of the fresh cocoa pulp [16,17,18]. Cocoa plantations are one of many drivers of deforestation, and assessments must consider competing sectors in a landscape [19]. Several inconveniences including a reduction in agrarian forest areas, impoverishment of soils, disappearance of biodiversity, and food insecurity for the populations have been associated to the deforestation [20]. However, cocoa cultivation that maintains higher proportions of shade trees in a diverse structure (AF cocoa) is progressively being considered as a sustainable land-use practice that meets ecological, biological, and economic objectives [21]. For a long time, AF in cocoa cultivation has also been regarded as environmentally preferable to other forms of cocoa-cropping activities in tropical forest regions [22,23]. By creating favorable microclimatic conditions, AF is viewed as a strategy to sustainably enhance agricultural production, which includes cocoa [24]. It was previously reported that the shade environment produced in AF practices affects the morphology, anatomy, and chemical composition of intercropped forages and therefore may affect forage quality [25]. Our assumption is that the biochemical composition of both pulp and cocoa beans can be affected by the tree shade favored by AF in cocoa cultivation. It is essential to evaluate the balance between the positive and negative effects of AF on the sensory profile of cocoa beans and chocolate, particularly as weather patterns change as a result of climate change. Although Côte d’Ivoire is the world leader producer of raw cocoa beans, up to now, no study really has addressed the issue of cocoa bean sensory and chocolate sensory quality in relation to AF as a relevant cropping system. Moreover, raw cocoa beans sourced from this country are not known for their fine aroma quality [26]. This work investigates the effects of AF as a cropping system on both the volatile compound profiles of cocoa beans and the organoleptic quality of the chocolate produced thereof. To achieve this goal, three major research questions were formulated:

(i) What could be the effect of AF as a cropping system on the sensory profile of cocoa beans?

(ii) Does the cultivation system (AF vs. FS) impact the level of volatile compounds in cocoa beans?

(iii) Does the sensory quality of chocolates made from cocoa beans obtained in the AF or FS systems differ significantly?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Sites of Carrying out of Research Activities

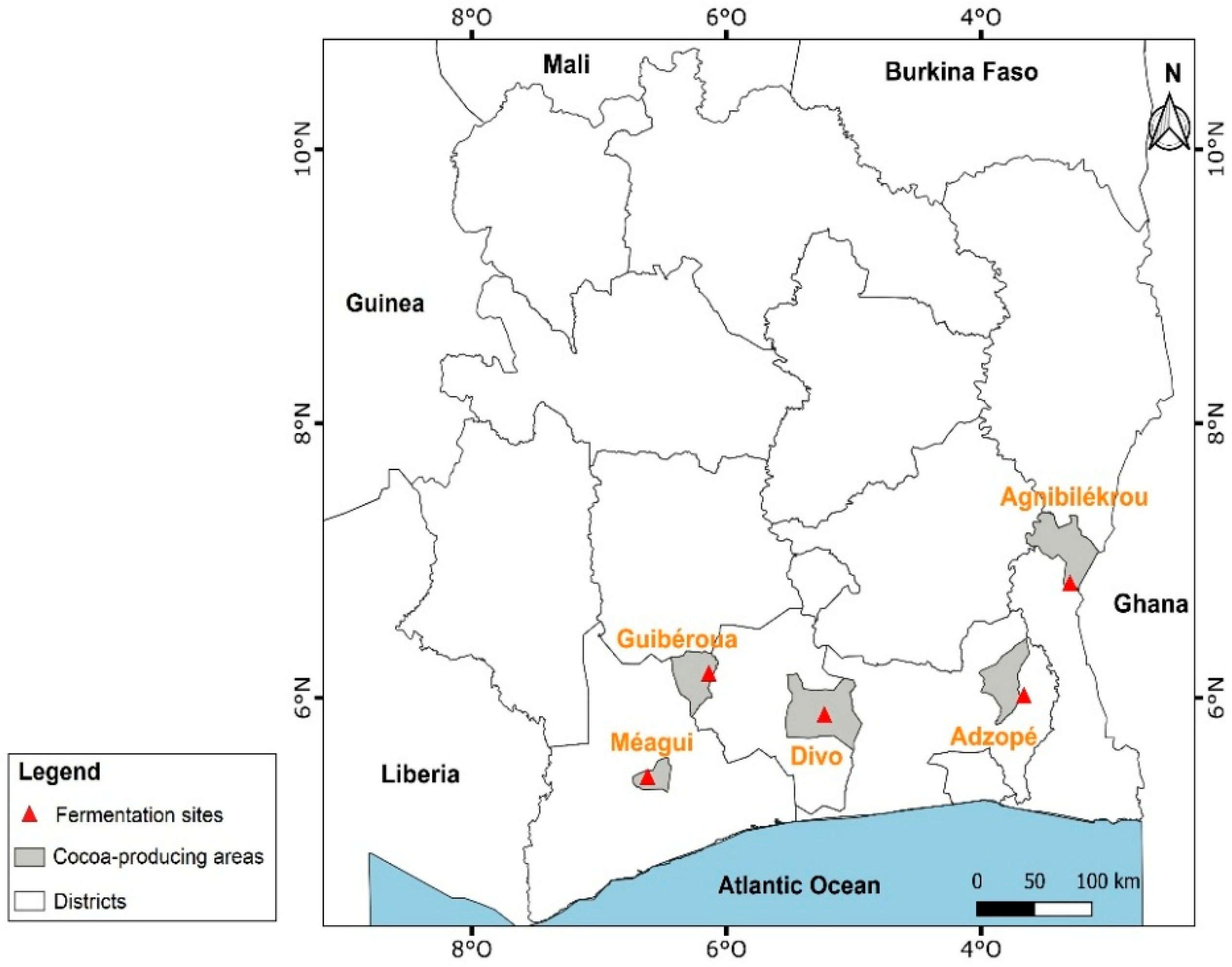

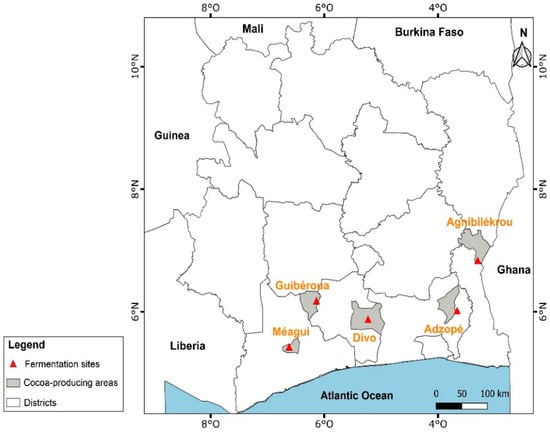

The harvest of ripe cocoa pods and primary cocoa postharvest processing (pod opening, fermentation, and sun-drying) was carried out in 5 main producing areas such as Agnibilekrou (east, geographic coordinates: 7°7′49.012″ N 3°12′11.074″ W), Adzopé (southeast, geographic coordinates: 6°6′25.726″ N 3°51′19.264″ W); Divo (south center, geographic coordinates: 5°49′59.999″ N 5°22′0.001″ W), Guibéroua (west center, geographic coordinates: 6°14′9.805″ N 6°10′16.536″ W), and Méagui (southwest, geographic coordinates: 5°24′00″ N 6°34′00″ O) on both AF and FS system cocoas (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of the main cocoa-producing areas in Côte d’Ivoire.

2.1.2. Cocoa Beans Samples

Fresh cocoa beans originating from the mature and full ripe pods of the Ivorian hybrid cultivar, commonly known as “Mercedes” (Amelonado × West African Trinitario), harvested [27] in November 2023 and 2024 from both AF and FS peasant plantation systems were used in this paper. Before the implementation of research activities, partnership agreements between all cocoa producers in each region and the project team were contracted. It is therefore in prior agreement with the owners of the cocoa plantations that we used the different production areas to carry out our research work. So, 5 groups of both AF and FS cocoa bean samples were formed as follows: Group 1 consisted cocoa bean samples from the Méagui region, Group 2 included cocoa bean samples from the Adzopé region, Group 3 comprised cocoa bean samples from the Guibéroua region, Group 4 consisted of cocoa bean samples from the Divo region and Group 5 contained cocoa bean samples from the Agnibilekrou region.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Fresh Cocoa Beans

The cocoa pods were stored for 3 days before manually opening them with a piece of wooden as a bludgeon, according to the method of Guehi et al. [26]. The fresh cocoa beans were extracted manually without placenta and then sorted to discard the rotten beans. After opening the cocoa pods, approximately 250 g of fresh cocoa beans were taken from each batch of cocoa obtained. These cocoa beans were manually shelled using a scalpel to remove the husk and mucilaginous pulp. The cocoa seeds obtained were rinsed with distilled water before being coarsely ground using a Moulinex grinder (John Gordon®, London, UK) [26]. The shreds of the different samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen at −80 °C to be reduced to fine cocoa powder and then stored at −20 °C in a glass vial hermetically closed until analysis of the volatile compounds [27].

2.2.2. Cocoa Beans Fermentation

The cocoa beans fermentation process was simultaneously carried out in wooden boxes in duplicate in all 5 fermentation locations for 6 days regardless of both cropping system and producing areas. We stirred simultaneously the fermenting cocoa beans at days 2 and 4 at all fermentation sites [27]. The fermented cocoa beans were put on the rack daily from 9 a.m. to 17 p.m. for sun drying until reaching 7–8% moisture.

2.2.3. Cocoa Bean Sampling

Three samples of 1000 g of 5-day-fermented cocoa beans were removed from both batches at each fermentation location. All operating workers wore new sterile gloves for the removal of the fermenting cocoa beans from the heap as previously reported by Koné et al. [28]. To ensure moisture removal of 7–8%, every fermented cocoa bean sample was sun-dried on the rack before carrying out chemical analyses [28].

2.2.4. Cocoa Volatile Compounds Analysis

Fifty grams of dry fermented cocoa beans was manually shelled and ground into fine powder (0.5 µm) using a Moulinex grinder (John Gordon®, London, UK) and then stored at −20 °C in a glass vial that was hermetically closed [27]. The volatile compounds were extracted from 2.5 g of each cocoa powder sample using the headspace solid-phase micro-extraction technique (HS-SPME) and fibers of 50/30 µm divinylbenzene/carboxene/polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS, Supelco, Sigma-Aldrich N.V., Bornem, Belgium) according to the previously described method by Nascimento et al. [29] with n-butanol as standard. Each volatile compound was identified using three criteria: (i) by comparison of the retention index with the database of volatile compounds of the Center for International Cooperation in Agronomic Research for Development (CIRAD) [30], (ii) by matching their mass spectra with those obtained from a commercial database (Wiley275.L, HP product no. G1035 A, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA), and (iii) whenever possible, the identification was confirmed using pure standards of the components [31]. The formula used to calculate the concentration of each volatile compound was as follows:

where qi is the relative concentration of the volatile compound; Ai is the area of the volatile compound i; Abut is the area of 1-butanol (internal standard); 60 is the concentration of 1-butanol in 100 µL of a test sample expressed in µg.g−1; me is the mass of the cocoa powder or the chocolate sample introduced into the vial in g.

The Kovats Retention Index is a dimensionless quantity used to express the relative retention time of a volatile compound in a chromatographic column normalized to the retention time of a reference n-butanol.

2.2.5. Sensory Analysis of Chocolate

Two samples of 2 × 500 g of dry 5-day-fermented cocoa beans were taken from each cocoa bean batch treated at five fermentation locations [27]. Whole cocoa beans were roasted at 125 °C for a duration of 25 min [30]. For the chocolate sensory perception, a trained panel of 12 judges (6 women, 6 men; age, 23–55 years) with experience in dark chocolate evaluation [27] participated in the study. The judges voluntarily agreed to participate in the sensory analysis and authorized the use of their information under a confidentiality agreement proposed by the sensory analysis laboratory of the UMR Qualisud, Montpellier (France). Ethical approval was not required for conducting the sensory evaluation in this study.

They were asked to smell and taste each AF chocolate sample against the FS chocolate as control made from cocoa beans sourced from the same cocoa-producing region. Two training sessions were held in order to calibrate the panel to the selected sensory traits. The performance of the panel was verified using reference chocolates with known sensory profiles and highly perceivable aromatic notes. Sixteen sensory descriptors were simultaneously evaluated using a scale ranging from 0 to 10, and a total score for global quality was assigned to each chocolate sample.

Quantitative descriptive analysis of the chocolate samples was performed according to the methodology reported by Kouassi et al. [27]. Each sample was assessed once. The intensity of 15 attributes and global quality were rated on a continuous line scale from 0 (absent) to 10 (very pronounced). Seven core traits were considered: sweetness, acidity, bitterness, astringency, cacao aroma intensity, cacao taste, and roasted. The complementary attributes included fruitiness, nuttiness, florality, woodiness, spiciness, and vegetal notes.

The sensory analysis was carried out using the “Click and Collect” methodology. This involved a tasting plan for each judge who collected and analyzed chocolate samples. For tasting sessions, FIZZ Software package 3.9.4 (Biosystemes, Saint-Ouen-l′Aumône, France) was used. A tasting plan was developed for each judge, and to randomize the chocolate samples in the sensory analysis, a Latin Square design was employed. The FIZZ software generated three-digit codes and randomized the samples for each judge, allowing the creation of analysis sessions containing four samples. Each judge accessed the FIZZ platform using their credentials, and while conducting the sensory analysis, they recorded the results for each quality trait for every chocolate sample online. Data were collected once all judges completed the sensory analysis of all chocolate samples.

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

The area of the chromatographic peak of each sensory compound precursor was calculated and then exported using Microsoft Excel 2013. The statistical analyses were carried out with the XLSTAT PLS2 (Addinsoft, New York, NY, USA). Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, DC, USA) was used to analyze the data from the sensory perception of each chocolate sample. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used as an unsupervised method to reveal clustering within targeted favor profiles, while partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was employed as a supervised method to identify discriminating volatile compounds across cropping systems and geographical origins of cocoa production [31]. The testing of the equality of variances was performed with the Fischer test with a single factor (p < 0.05) in order to indicate the significant differences between volatile compound profiles of cocoa beans and chocolate samples as well as the sensory perception of chocolate produced from tested cocoa as affected by the cropping system or the producing geographical origin [27].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Agroforestry on Native Volatile Compound Contents of Crude Cocoa Beans

Table 1 indicates that five (5) main classes of volatile compounds including aldehydes, esters, alcohols, ketones, and terpenes were naturally found in crude cocoa beans regardless of both the cropping system and producing geographical origins in Côte d’Ivoire. Similar classes of volatile compounds were found in unfermented cocoa beans by other experiments [32]. The native volatile compound classes in crude cocoa beans could be due to the biological activity of plants that produce a wide spectrum of volatile compounds including aldehydes, alcohols, carboxylic acids, isoprene, and monoterpenes [33]. Among the oxygenated hydrocarbons which are produced by trees, C-1 and C-2 aldehydes, alcohols, and carboxylic acids are of great importance [34]. Cocoa beans from both the Adzopé and Agnibilékrou regions recorded higher concentrations of aldehydes from 102.4 ± 12 to 138.6 ± 7.6 µg.g−1 regardless of cropping system. AF cocoa recorded higher aldehydes concentrations than FS cocoa in all producing regions except Divo and Guiberoua. The total concentration of ester class varied from 56 ± 3.5 to 159.8 ± 4.2 µg.g−1 regardless of both cocoa cultivation system and cocoa-producing areas. AF cocoas produced in the Méagui region are richest in esters with 159.8 ± 4.2 µg.g−1. Furthermore, the AF cocoa bean samples universally contained higher concentrations of esters than the FS cocoas from all of the cocoa-producing regions tested except Agnibilékrou and Divo. C-1 compounds are synthesized during many growth and developmental processes such as seed maturation and the senescence of plant tissues. The production of C-2 compounds, however, seems mainly to be associated with changing environmental conditions, particularly during stress [33]. According to Kreuzwieser et al. [33], acetaldehyde is produced in the leaves of trees if the roots are exposed to anaerobic conditions and produces ethanol through alcoholic fermentation. The production of acetaldehyde and ethanol was not catalyzed by the enzymatic activity of microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. The production of these metabolites could be also ascribed to the fact that when exposed to anoxia or hypoxia, the plant organ could be enriched in the enzymes necessary for fermentation [34]. In addition, aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes (ALDHs) catalyze the oxidation of a broad range of aliphatic and aldehydes to their corresponding carboxylic acids using NAD+ or NADP+ as cofactors [35]. The concentration of the alcohols class was the highest, ranging from 173.9 ± 12 to 1134.4 ± 34 µg.g−1, while the concentration of the terpenes class was the lowest, between 1.7 ± 0.4 and 12.7 ± 7.2 µg.g−1, as previously reported by Yang et al. [32]. AF cocoa beans from the regions of Adzopé, Guibéroua and Méagui recorded a higher concentration in the alcohol family than FS cocoa beans, inversely to cocoa from the regions of Agniblekrou and Divo. Moreover, AF cocoa beans from the Méagui region showed the highest concentration of alcohol with 1134.4 ± 34 µg.g−1. The alcohol class concentration varied from 58.6 ± 7 to 504.6 ± 2.7 µg.g−1 regardless of the cropping system and producing regions. AF cocoa beans from the areas of Agniblékrou, Guiberoua and Méagui recorded more ketones than FS cocoa. Cocoa beans sourced from the Divo area exhibited similar concentrations in ketones of around 191–195 µg.g−1.

Table 1.

Changes in total concentration of each main class of sensory compounds of crude cocoa beans as a function of the cropping system in different cocoa-producing areas of Côte d’Ivoire.

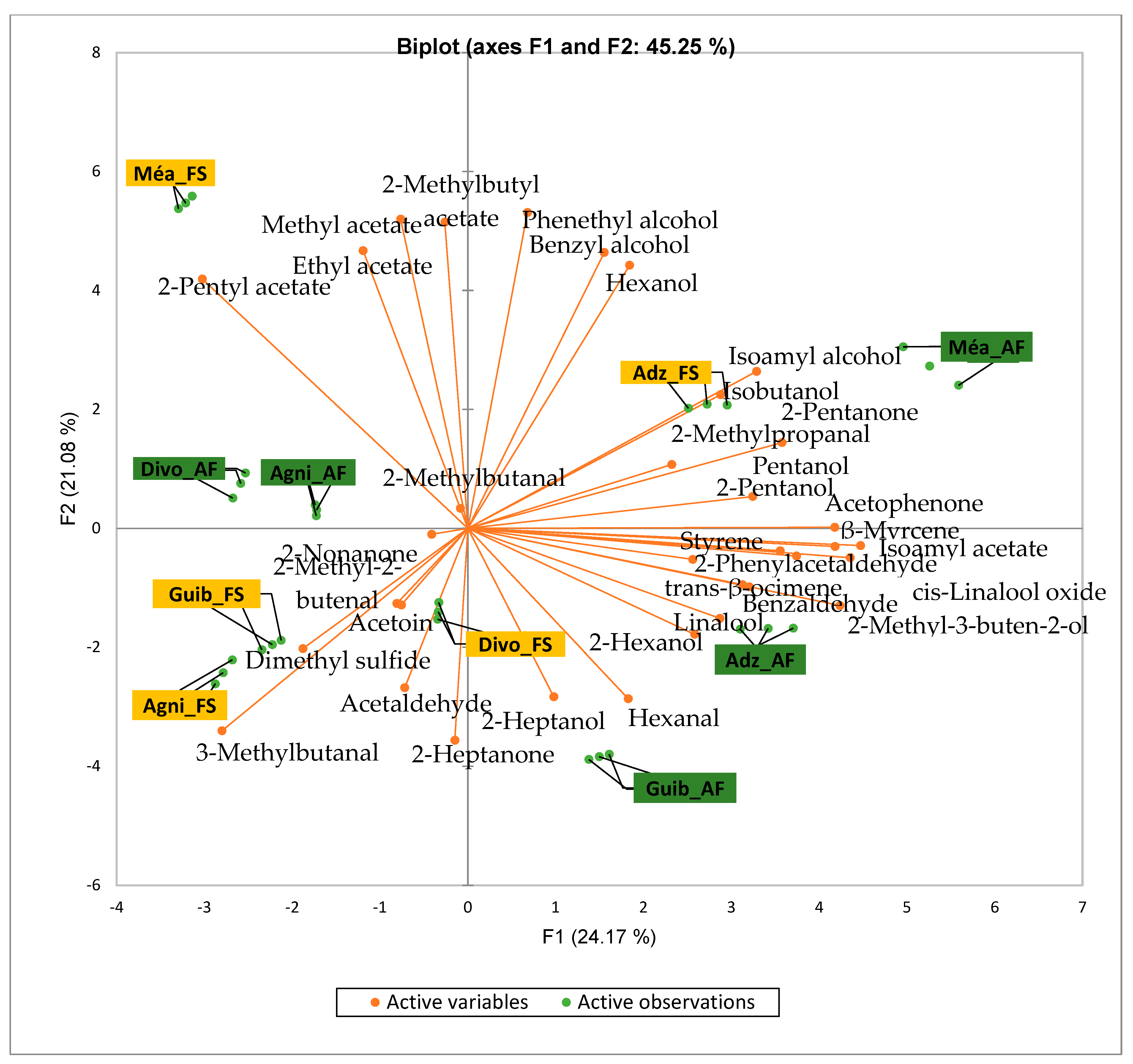

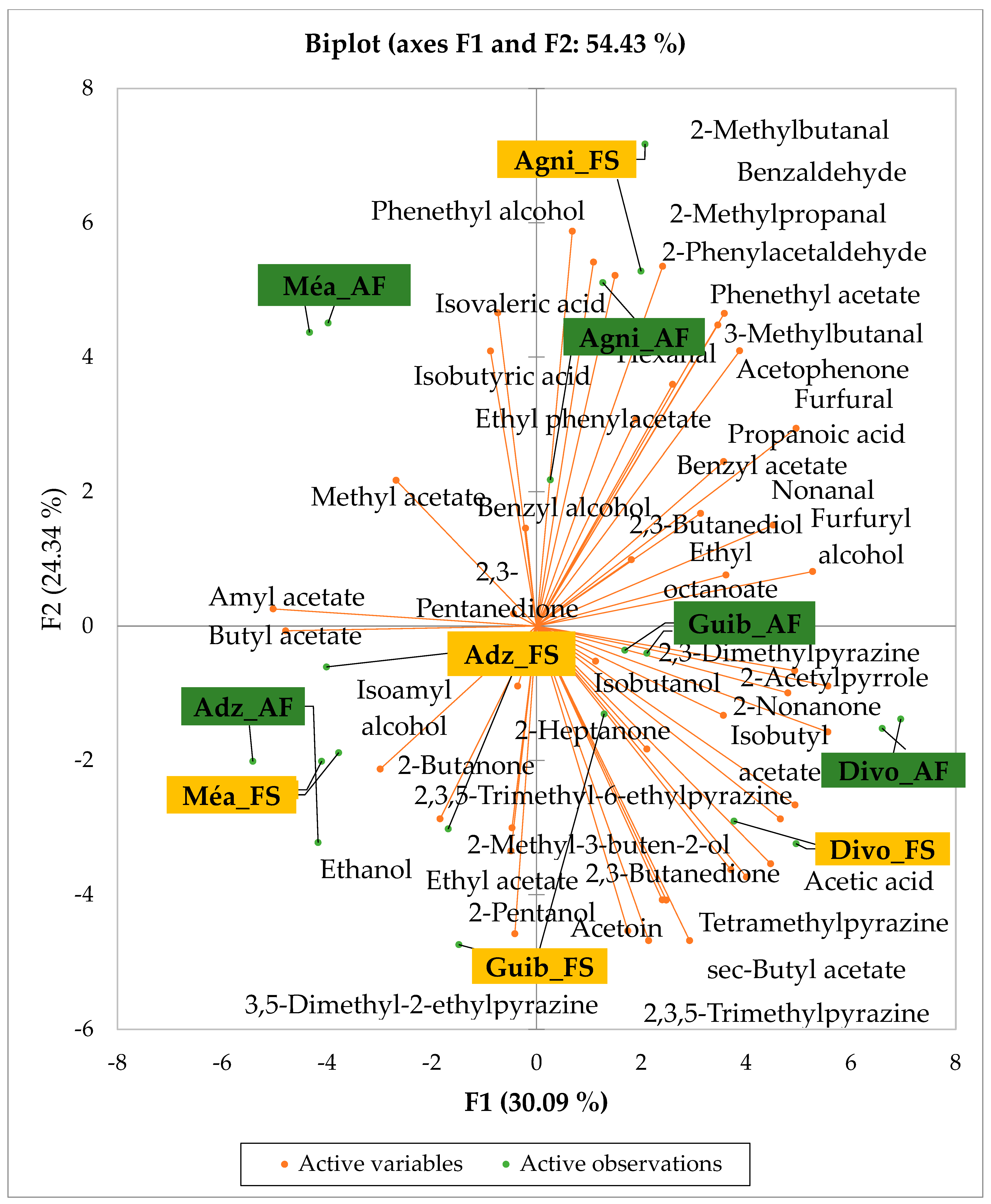

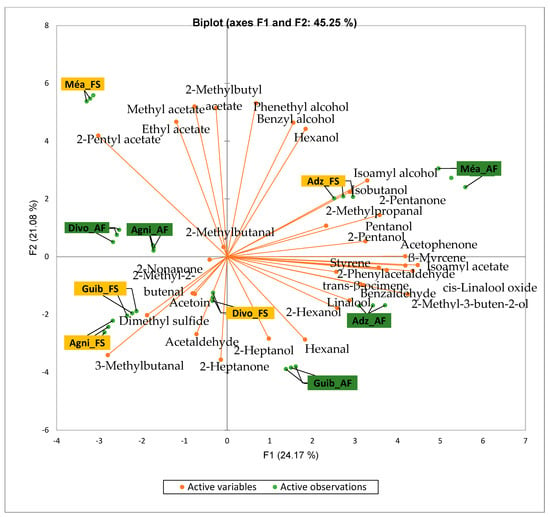

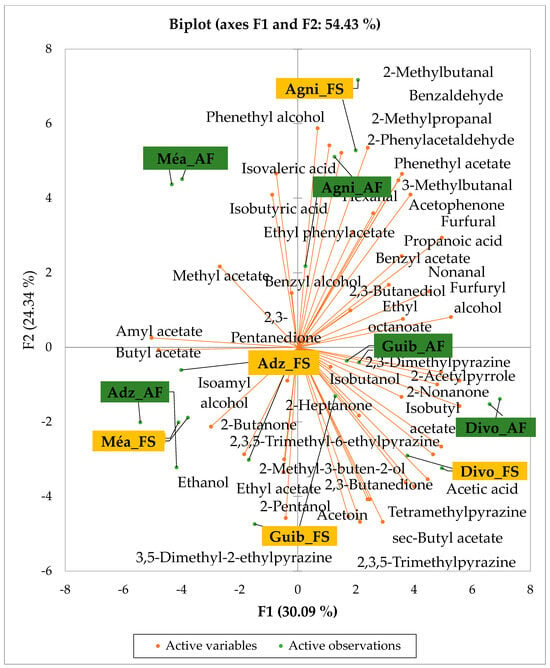

Figure 2 presents the PCA biplot revealing different groups of unfermented cocoa beans with specific volatile compound profiles produced from the cocoa cultivation system. A total of 34 volatile compounds were found in all of the cocoa bean samples tested. AF has always had a significant influence on sensory profiles. The volatile compound profiles of cocoa beans from AF system were differentiated from those of cocoa beans from FS system throughout all the analyzed production regions except the Agnibilekrou area.

Figure 2.

PCA biplot of the sensory profiles of crude cocoa beans according to cropping system. The volatile compounds and cropping systems of the cocoa-producing regions of Côte d’Ivoire are indicated on the labels at the bottom of the figure. Adz = Adzopé region; Agni = Agnibilékrou region; Divo = Divo’s region; Guib = Guibéroua region; Mea = Méagui region.

Cocoa bean samples from the Méagui region were mainly characterized by the alcohols such as isoamyl alcohol, isobutanol, pentanol and hexanol. Cocoa bean samples from the Adzopé region recorded various classes of volatile compounds such as benzaldehyde, 2-phenylacetaldehyde, isoamyl acetate, linalool, and β-myrcene. Group 3 consisted of cocoa beans whose sensory profiles recorded 2-heptanol, 2-hexanol, and hexagonal. Volatile compounds such as 2-methyl butanol were detected in the AF cocoa beans from both the Divo and Agnibilekrou areas in Group 4.

The total number of volatile compounds found in our unfermented cocoa bean samples is less abundant than those found in cocoa beans from China, which are 2.5 times higher [36]. The genotype, climatic and pedological factors, soil quality [10], and cropping system may be responsible for these differences. The significant variations observed between the concentrations of some groups of volatile compounds of AF cocoa bean samples from some geographic origins could be due to the variation in AF system types of cocoa cultivation in Côte d’Ivoire. The density of associated trees to the AF system consisted of 48.16 individuals/ha in the west, 22.79 individuals/ha in the central west, and 25.39 individuals/ha in the southwest, as reported by Konan et al. [37]. So, we thought that the shade created by each type of AF system also varied and differentially impacted the soil fertility from cocoa farms to cocoa farms and from producing area to producing area. Indeed, Sauvadet et al. [38] reported that the effects of shade type management are more pronounced on the soil nutrient availability through changes in the soil food web structure than on the direct organic chemical composition of crops, highlighting the importance of choosing shade tree species in an AF system. Moreover, the AF system in the central west and southwest is dominated by trees taller than 8 m with a high density of associated perennial crops in the central west, while the AF systems in the southwest are characterized by plots averaging 30 years in age [37]. To conclude, AF in cocoa cultivation influenced the native volatile compounds of Ivorian cocoa beans. But the significant variation observed in the quality of volatile compound profiles depends on the producing geographical origins due to the type of AF and probably climatic factors as well. Our study is relevant and could be continued by implementing the same AF system regarding the density and height of trees, the soil quality, the local climatic factors of each area, and the age of the studied cocoa trees, which seems to impact the sensory profile of the crude cocoa beans [10].

3.2. Effect of Agroforestry on Sensory Compound Contents of Dry Fermented Cocoa Beans

Seven (7) main classes of sensory compounds, including aldehydes, esters, alcohols, ketones, acids, pyrazines, and terpenes, were detected in the dry fermented cocoa bean samples regardless of both the cropping system and producing regions in Côte d’Ivoire (Table 2). In the dry fermented cocoa beans, the concentrations of each sensory compound class were significantly increased. Also, two new classes such as acids and pyrazines occurred in comparison to unfermented cocoa beans regardless of both the cropping system and the cocoa-producing region. Fermentation led to the development of specific cocoa volatile compounds via the degradation of proteins and formation of volatile compounds, such as pyrazines, which were described as one of the few classes of compounds with desirable sensory properties [36]. AF dry fermented cocoa beans recorded higher concentrations of aldehydes than FS cocoa beans in the Guibéroua and Méagui regions, while lower concentrations were recorded in cocoa beans sourced from the Agnibilékrou and Divo regions. Cocoa bean samples from the Adzopé region recorded the highest concentrations of aldehydes (456.08 ± 77.6 µg.g−1), while those from the Guibéroua region recorded the highest concentration of esters with about 117. 68 ± 9.7 µg.g−1. Alcohol concentrations of dry fermented cocoa beans varied from 83.31 ± 1.2 to 385.67 ± 259.1 µg.g−1. The concentration of ketones was relatively constant; the approximate values ranged between 40.55 ± 12.76 and 154.46 ± 4.9 µg.g−1 regardless of both the cropping system and the cocoa-producing area. All tested dry fermented cocoa bean samples contained pyrazines. However, the highest concentration of pyrazines was recorded in dry fermented cocoa beans sourced from the Divo region (70.61 ± 28.51 µg.g−1).

Table 2.

Changes in total concentration of each class of volatile compounds (µg.g−1) of AF dry fermented cocoa beans from different cocoa-producing region of Côte d’Ivoire.

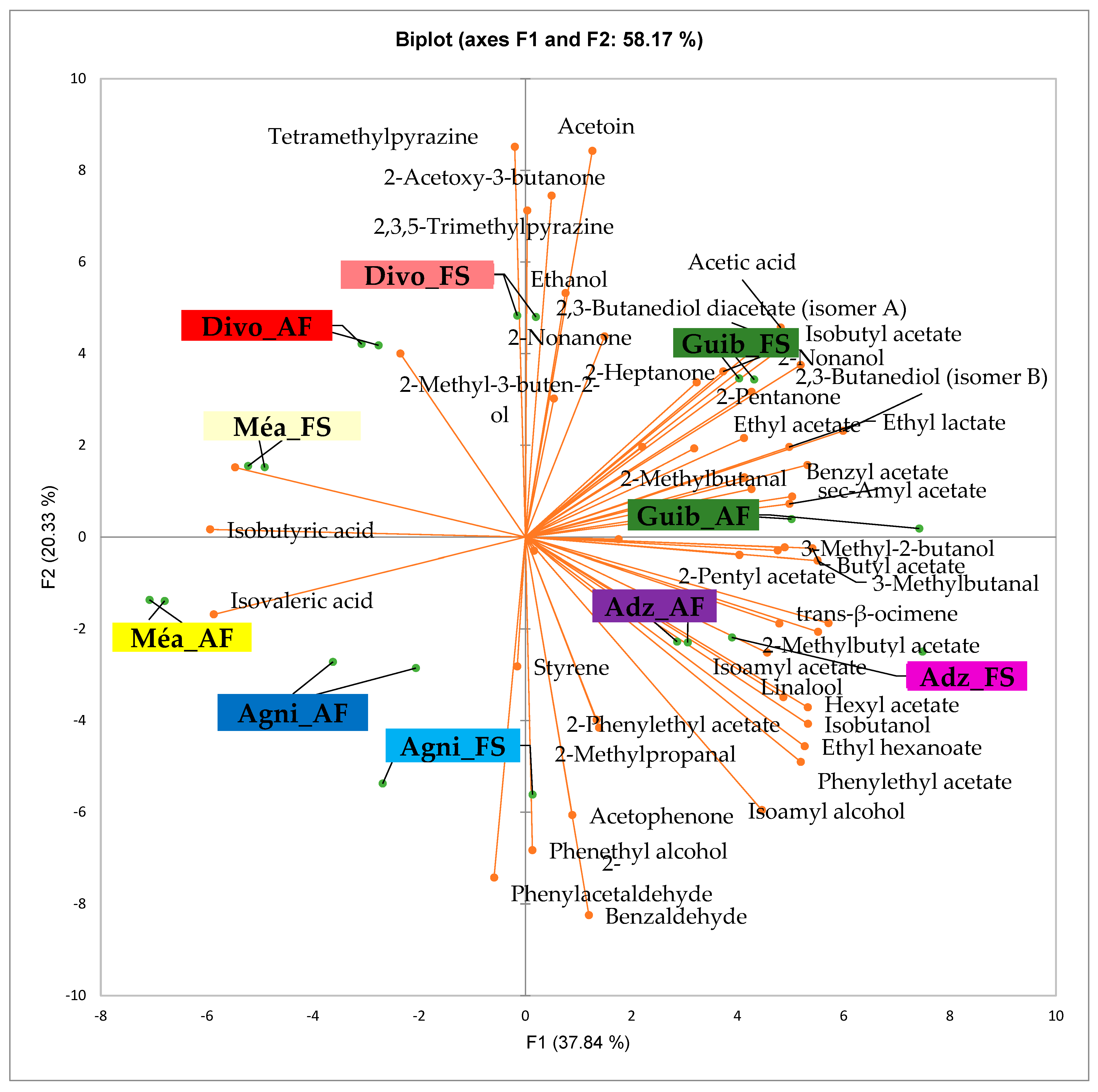

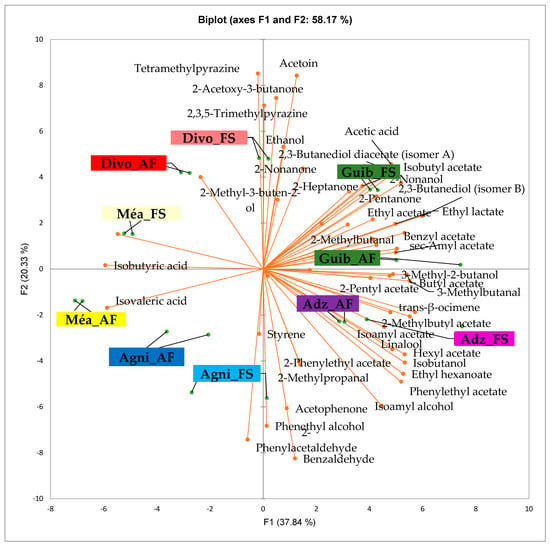

Figure 3 presents the PCA biplot, which reveals different groups of dry fermented cocoa beans regarding their sensory compound profiles according to the cocoa cultivation system between all production areas tested. A total of 49 volatile compounds were found in all of the dry fermented cocoa bean samples tested. The volatile compound profiles of cocoa beans from the AF system were not differentiated from those of FS cocoa beans, while the geographical origins did show a significant influence.

Figure 3.

PCA biplot of the sensory profiles of dry fermented cocoa beans according to cropping system. The volatile compounds and cropping systems of the cocoa-producing regions in Côte d’Ivoire are indicated on the labels at the bottom of the figure. Adz = Adzopé region; Agni = Agnibilékrou region; Divo= Divo region; Guib = Guibéroua region; Mea = Méagui region. (AF = agroforestry system; FS = full sun system).

Group 1 consisted of both AF and FS cocoa bean samples from the Méagui region. The volatile compound profiles contained primarily isoamyl alcohol, phenylethyl acetate, ethyl acetate, ethyl hexanoate, linalool, hexyl acetate, methylethyl acetate, methyl butanol, butyl acetate, 2 acetate, 2-methylpropanal, and ethyl octanoate. Group 2 included both AF and FS cocoa beans from the Adzopé area. Its volatile compound profile contained more sensory compounds, including isoamyl alcohol, phenylethyl acetate, ethyl hexanoate, linalool, methyl, ethyl acetate, methyl butanol, butyl acetate, 2-pentyl acetate, and 2-methyl propane. Group 3 included both AF and FS cocoa bean samples sourced from the Guibéroua region. These cocoa bean samples exhibited volatile compound profiles consisting of various classes such as benzylacetate, sec amyl acetate, 2 heptanol, 2-methyl butanol, 2,3-butanol acetate, 2,3 butanediol, ethylacetate, 2,2-butanediol acetate, acetic acid, isobutyl acetate, 2-nonanol, and 2-heptanone. Group 5 consisted of cocoa bean samples from the Agnibilékrou region which were characterized by no specific volatile compounds, whereas Group 4 consisted of cocoa bean samples from the Divo region and contained acetoin, 2-acetoxy-3-butanone, 2,3,5-trimethyl pyrazine, ethanol.

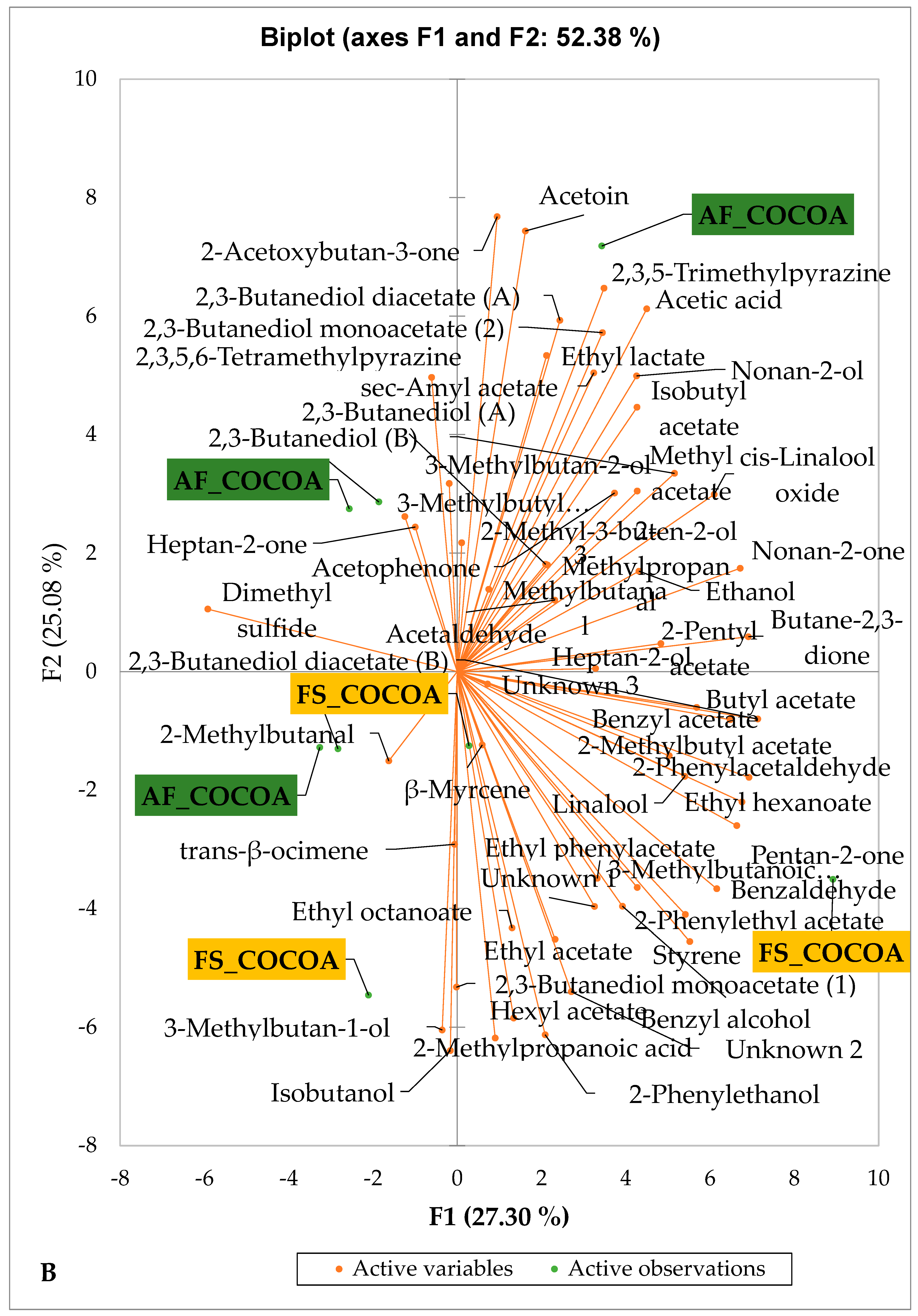

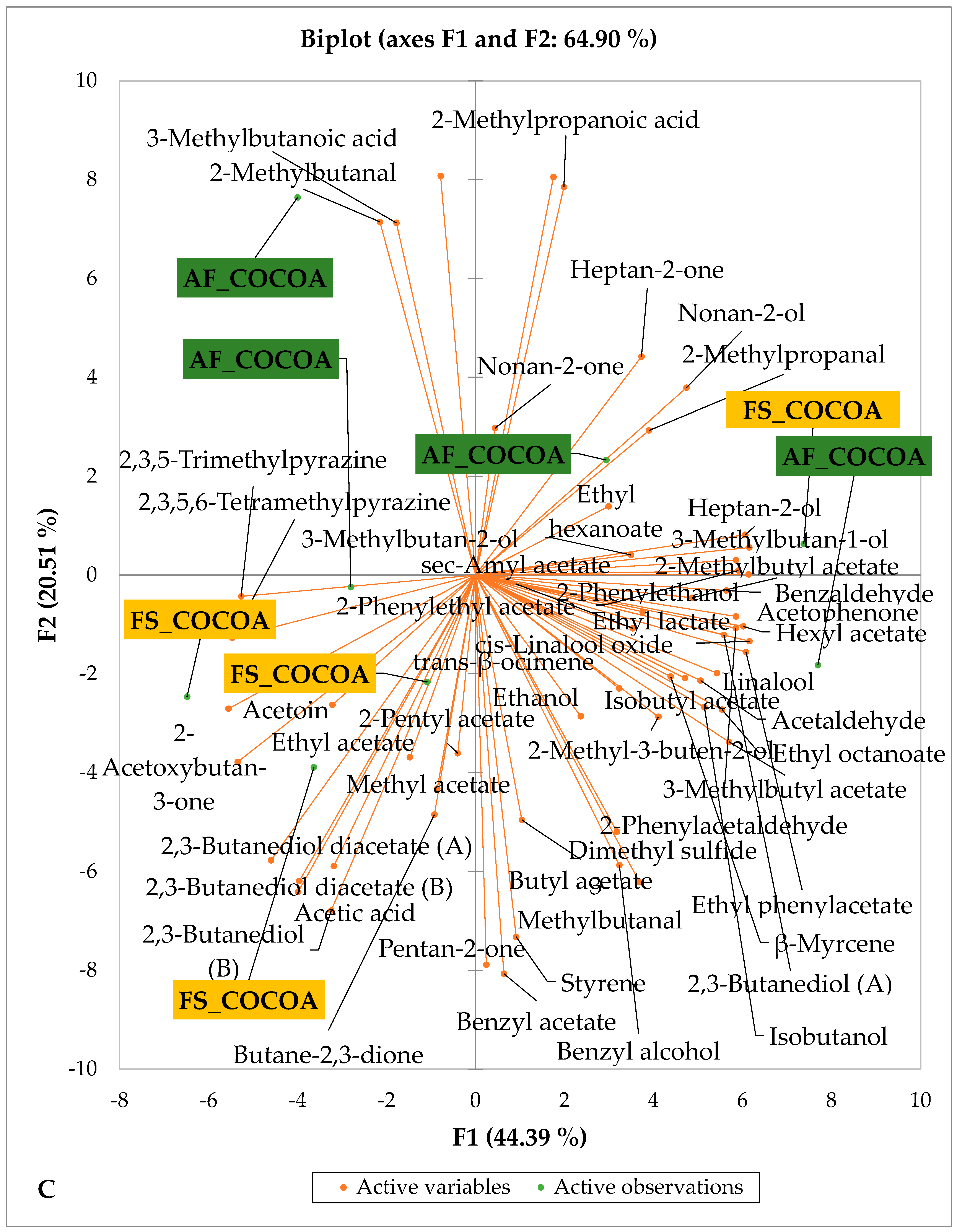

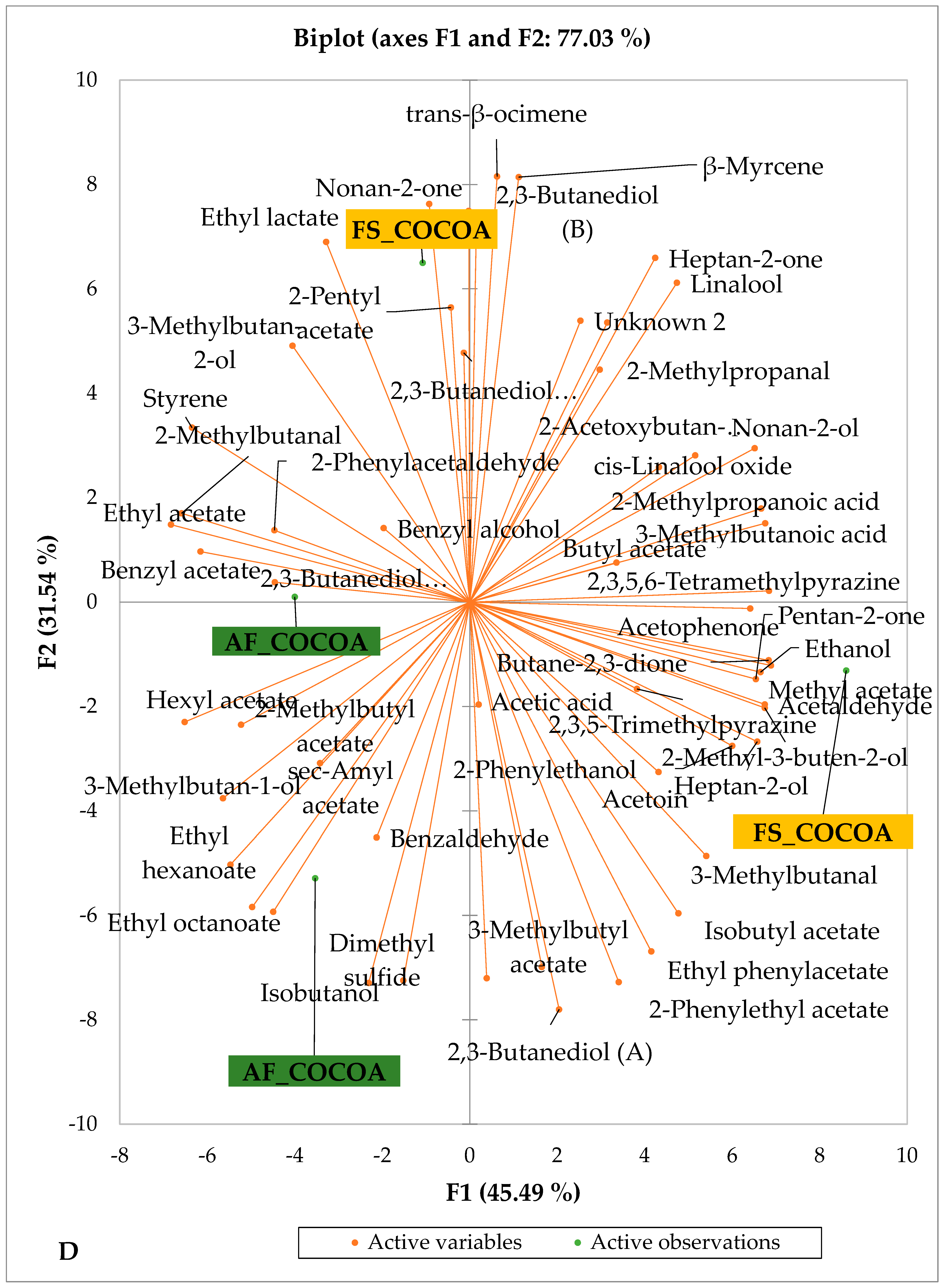

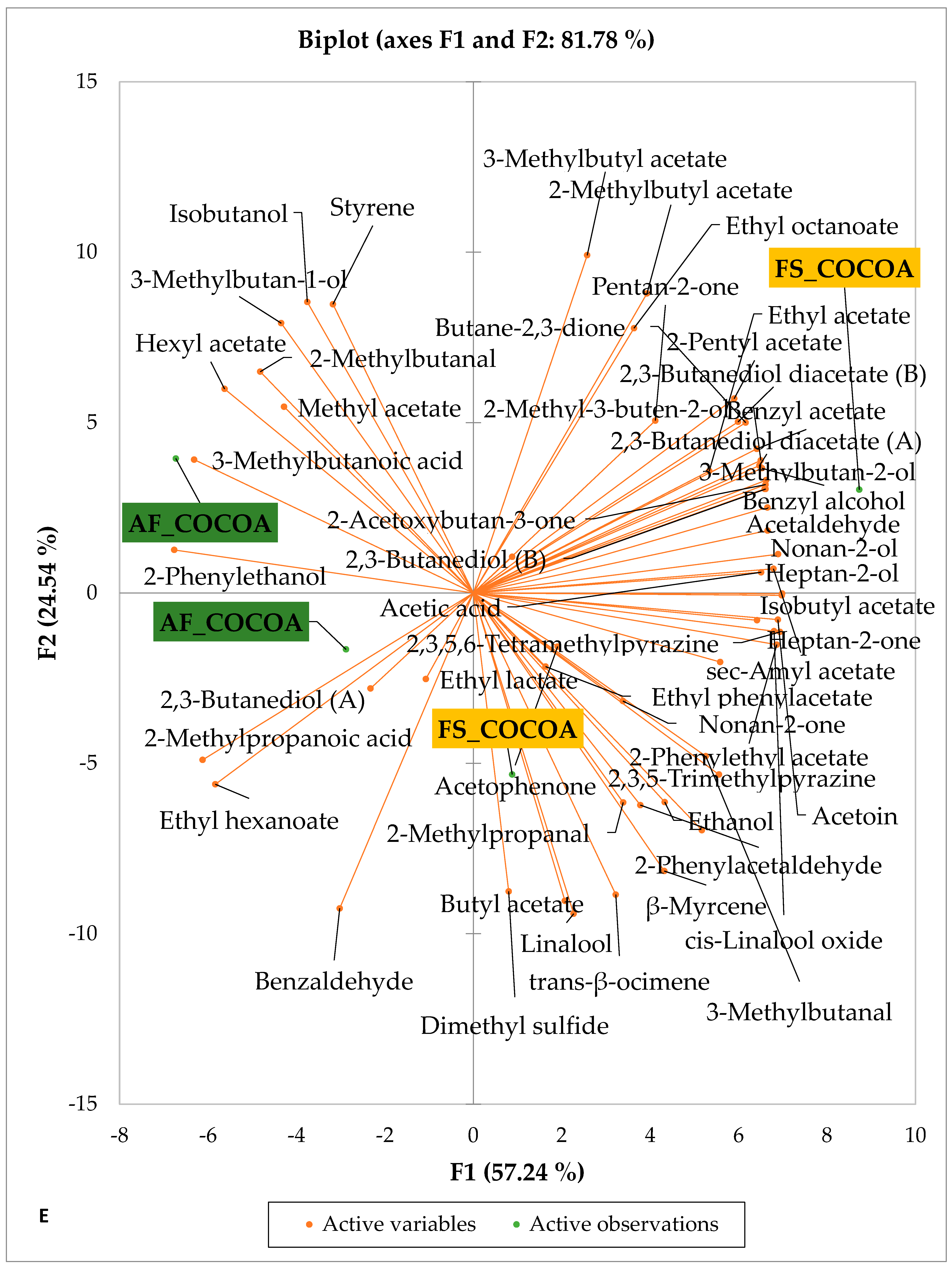

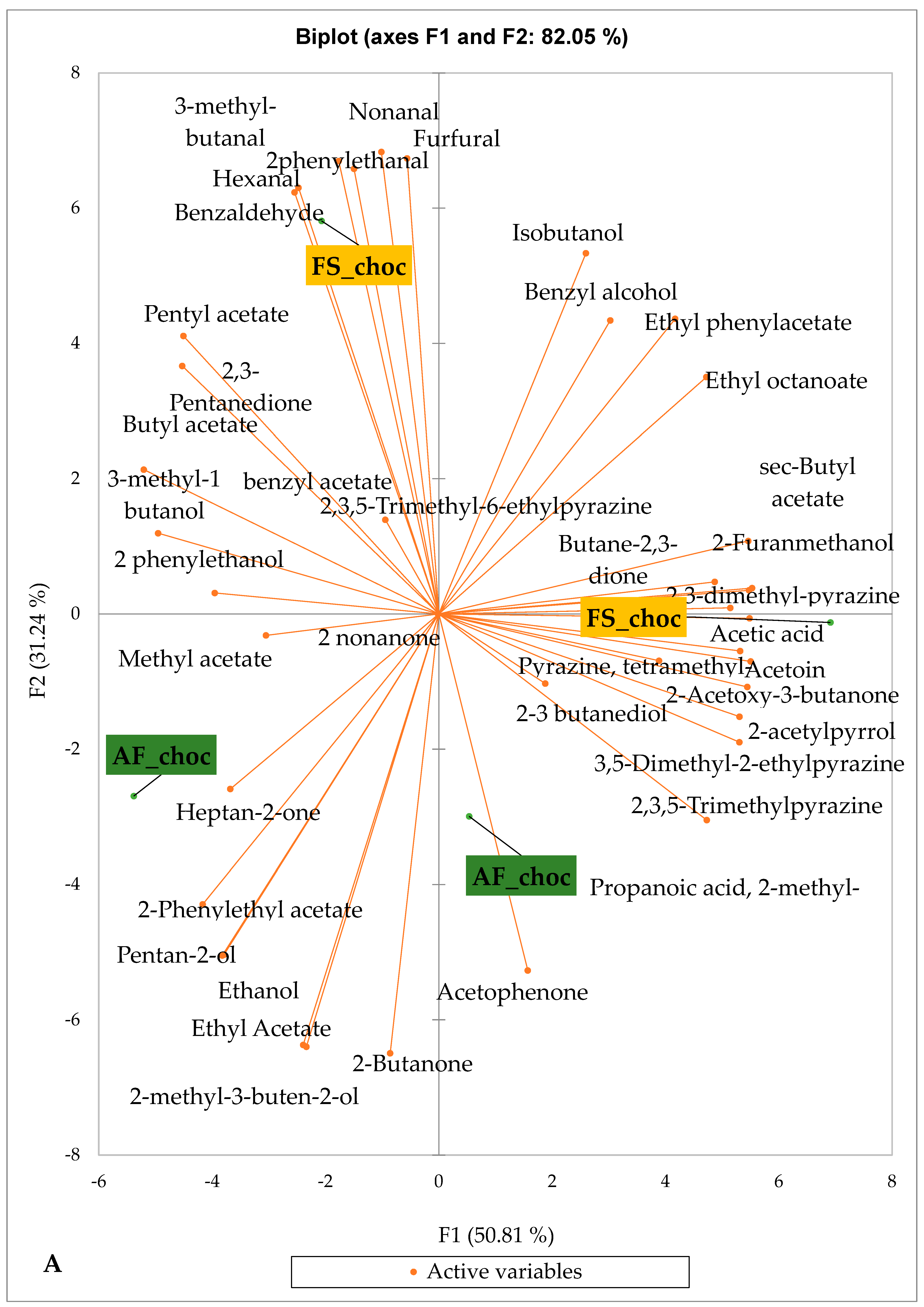

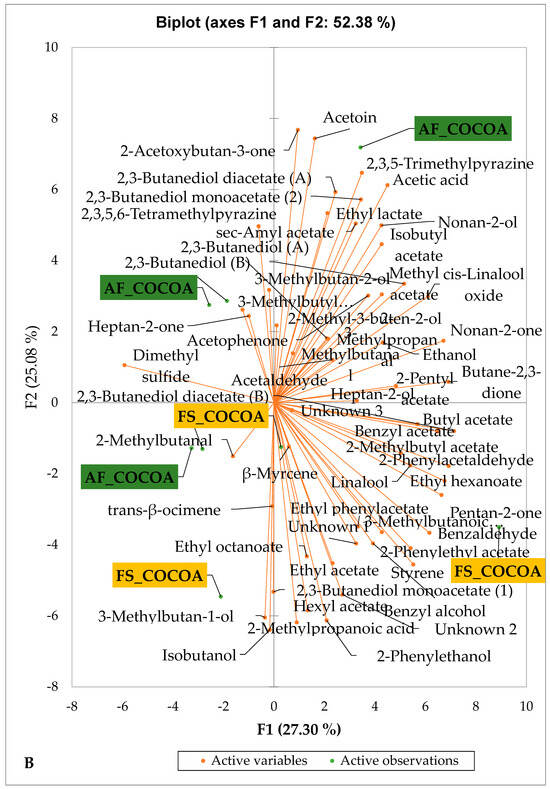

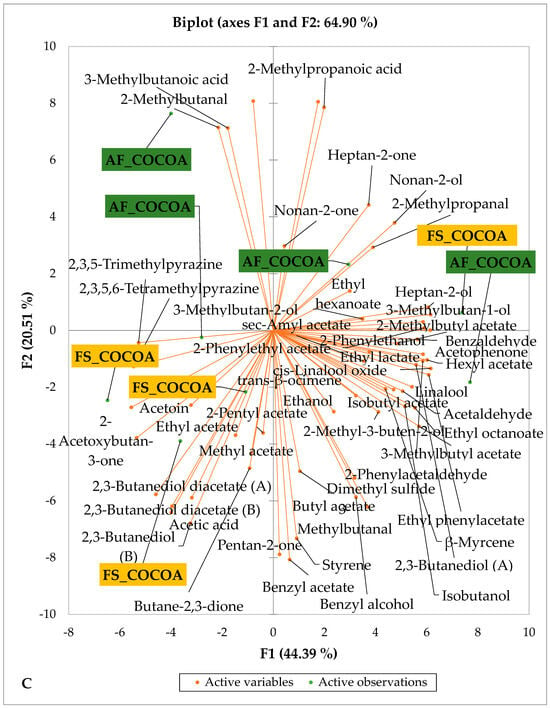

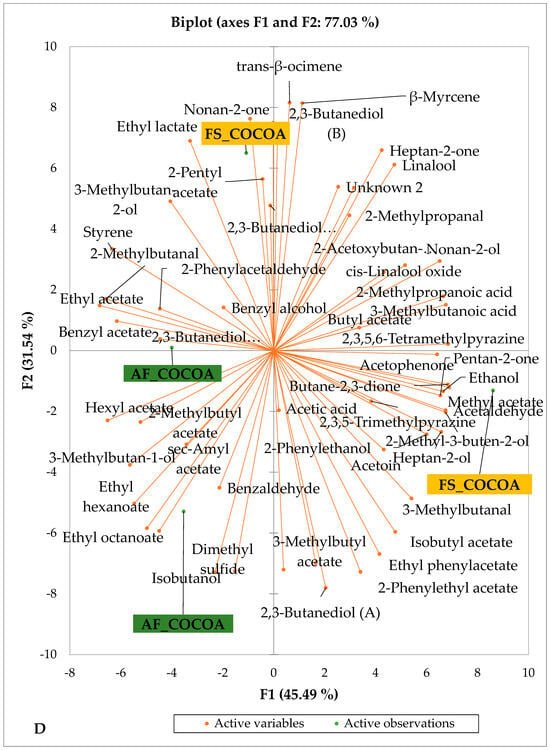

Figure 4 presents the PCA biplot, which reveals the sensory compound profiles of different groups of dry fermented cocoa beans according to the cocoa cultivation system within each cocoa-producing area tested. AF had a significant effect on the sensory profiles of dry fermented cocoa beans from only two cocoa-producing areas, including the Guiberoua and Méagui regions. The volatile compound profiles of cocoa beans from the AF and FS systems sourced from the Adzopé, Agnibilékrou, and Divo regions were similar.

Figure 4.

PCA biplot of the sensory profiles of dry fermented cocoa beans according to cropping system. The volatile compounds and cropping system of the cocoa-producing regions in Côte d’Ivoire are indicated on the labels at the bottom of the figure. (AF = agroforestry system; FS = full sun system). (A) Adzopé region; (B) Agnibilékrou region; (C) Divo region; (D) Guibéroua region; (E) Méagui region.

Our results regarding the presence of seven classes of sensory compounds in dry fermented cocoa bean samples are in agreement with those of several previous works [7,27,30,36,39,40,41,42]. The appearance of new classes, including acids and pyrazines, in the beans could be due to the microbial activity comprising yeast and acetic acid bacteria during cocoa fermentation, as previously reported by Fang et al. [35]. Indeed, several volatile compounds not found in fresh beans gradually produced after fermentation and appeared in dry fermented cocoa beans. Our results regarding the detection of a pyrazines class in all of our tested dry fermented cocoa bean samples regardless of both cropping system and production area are in agreement with those reported by several works [39,43,44]. However, several other researchers reported that pyrazines are formed in cocoa beans only during roasting [45,46]. Yet, recent work has highlighted that the pyrazines are formed in food via both thermal treatment and fermentation [47]. Furthermore, for a long time, it was reported that pyrazines are formed in cocoa beans during fermentation due to the enzymatic activities produced by Bacillus sp. [43,48], but their concentration was increased by thermal treatment notably during the roasting [49]. The acidification of cocoa beans could be ascribed to the production of a high amount of acetic acid by acetic acid bacteria during fermentation, which induces various biochemical reactions and pathways leading to the development of other various cocoa sensory compounds [36]. The acidification process of cocoa beans is largely influenced by the acetic acid content, which closely correlates with the pH level of the beans. [50]. In addition, the aldehydes, esters, and acids classes recorded higher concentrations, while the pyrazines and terpenes families presented lower concentrations, as previously reported [36,39]. It is possible that the increased acid content is responsible for the creation of esters and higher alcohols [51]. The highest concentration of aldehydes in some of the AF and FS dry fermented cocoa beans from the Guiberoua and Méagui regions could be due to the activity of Galactomyces geotrichum, which is a aldehydes-producing yeast species currently involved in cocoa fermentation in Côte d’Ivoire [28]. The high concentrations of alcohols in AF dry fermented cocoa beans could be due to the wide amounts of fermentable sugars of cocoa pulp [52] and the involvement of high alcohols producing yeast species including Candida tropicalis, Wikehamoyces anomalus, Pichia kudriazevii, Saccharomyces cerevisae, Pichia galieformis [28]. Ethanol and acetic acid are the primary molecules generated when cocoa pulp substrates, such as sugars, citric acid, and polyphenols, are metabolized [53]. Indeed, the AF system favors a higher amount of substrates in AF cocoa pulp than the FS cocoa does via the soil fertilization, as previously reported [38]. To conclude, although AF influences the native sensory compounds of cocoa beans, it does not influence the sensory profiles of dry fermented beans, which is probably due to the activity of the yeast involved in cocoa fermentation. However, regarding each cocoa-producing area, we observed that AF influenced the volatile compound profiles of dry fermented cocoa beans from the Guibéroua and Méagui areas in the central west of Côte d’Ivoire. These results could be ascribed to the type of AF system in this region, which is dominated by trees taller than 8 m with a high density of associated perennial crops [37], the climatic factors, the soil quality [10], and probably the community of yeast species involved in the fermentation process [27].

3.3. Effects of Agroforestry and Producing Regions on the Desired Volatile Compound Profiles of Cocoa Beans

Table 3 shows the concentration of several positive sensory compounds of dry fermented cocoa beans regarding both the AF system and the cocoa-producing regions. A total of 15 useful sensory compounds were found in all of the dry fermented cocoa beans analyzed regardless of the cropping system. The detected desirable sensory attributes belong to various classes such as esters (3-methylbutyl acetate, 2-methylbutyl acetate, benzyl acetate), aldehydes (2-methylpropanal, 2-methylbutanal, 3-methylbutanal), alcohols (benzyl alcohol, 2-phenylethanol, linalool), ketones (acetoin, 2-acetoxybutan-3-one, acetophenone), and pyrazines such as 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine and tetramethylpyrazine. The fermentation process significantly influences cocoa’s sensory attributes and aroma [54]. Several desirable volatile compounds were detected at the highest concentrations in AF dry fermented cocoa beans from the Guiberoua region. Indeed, 2-methyl butyl acetate, 3-methyl butyl acetate and benzyl acetate were found at 84.2 ± 3.7, 76.3 ± 11.8, and 3.4 ± 2.3 µg.g−1 concentrations respectively. Regarding aldehydes, AF dry fermented cocoa beans recorded 65.32 ± 3.32 µg.g−1 of methyl butanol, while FS cocoa beans recorded 26.3 ± 9.7 µg.g−1. In the class of alcohols, 2-phenylethanol was found at the highest concentrations of 75.4 ± 54.3 and 22.7 ± 8.2 kg.g−1 µg.g−1 in AF and FS cocoa bean samples, respectively. Among pyrazines, tetramethyl pyrazine was found at the highest concentration in dry fermentation produced in the Guiberoua area. The concentration of specific acetate esters including ethyl acetate and phenyl ethyl acetate can be favored by fermentation techniques like turning the beans [55]. The richness of Gubéroua cocoa in various relevant volatile compounds may be due to the sensory attributes produced by yeast species such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia kudriazevii and Hanseniaspora opuntia in the fermentation of cocoa carried out in this region [28,56]. Furthermore, Crafack et al. [54] have previously demonstrated that several sensory compounds are produced primarily by yeast and bacteria during the fermentation process, which converts amino acids and higher alcohols into various volatile compound precursors. According to Ho et al. [46] and Ziegleder [57], the volatile compound profile of chocolate is enhanced by significant increases in esters concentration during spontaneous fermentation. The distinct floral and fruity notes that distinguish premium chocolate from bulk varieties are due to other key compounds like linalool (found in fine cocoa varieties) and phenylethyl acetate [12]. Linalool is the essential volatile compound that forms during cocoa fermentation, as Ziegleder [58] has reported for a considerable amount of time. Our finding that tetramethyl pyrazine is the main compound of the pralines class was in accordance with those of previous studies [59]. Although several works reported that the pyrazine group is more common in well-fermented roasted beans, these metabolic products of Bacillus species (B. subtilis or B. megaterium) are formed at the end of cocoa fermentation [40,41,60,61]. Each sensory compound could contribute to the final volatile compound profile of dry fermented cocoa beans. For example, pyrazine compounds have cocoa, chocolate, walnut, popcorn, coconut, candies, and fruity notes [42]. However, certain volatile compounds were more concentrated in AF cocoa beans than those of FS from the Guibéroua region. The impact AF on the formation of crucial volatile compounds in dry-fermented cocoa beans has yet to be shown.

Table 3.

Changes in total concentration of desirable sensory compounds of dry fermented cocoa beans as a function of cropping system in different cocoa-producing regions of Côte d’Ivoire.

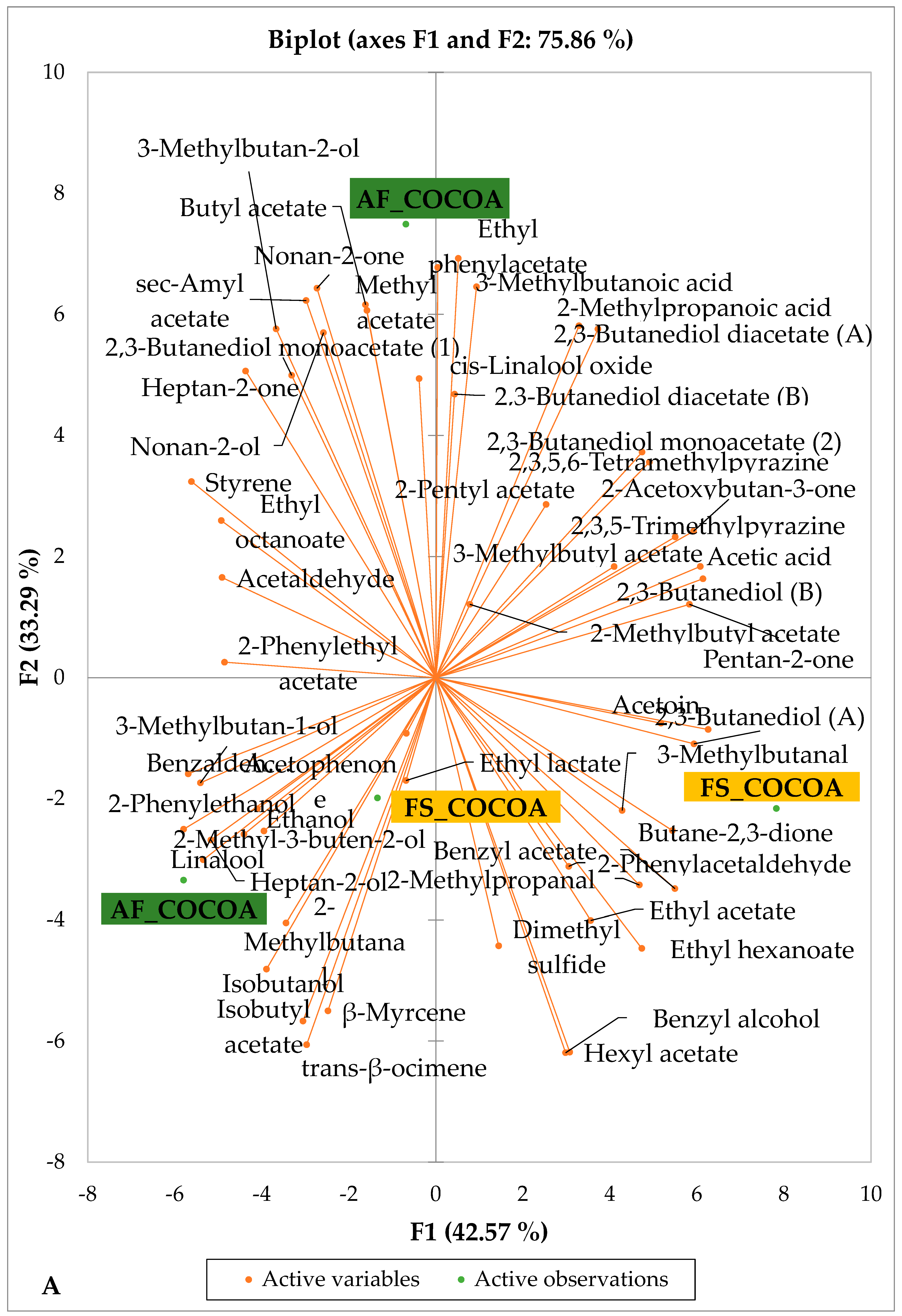

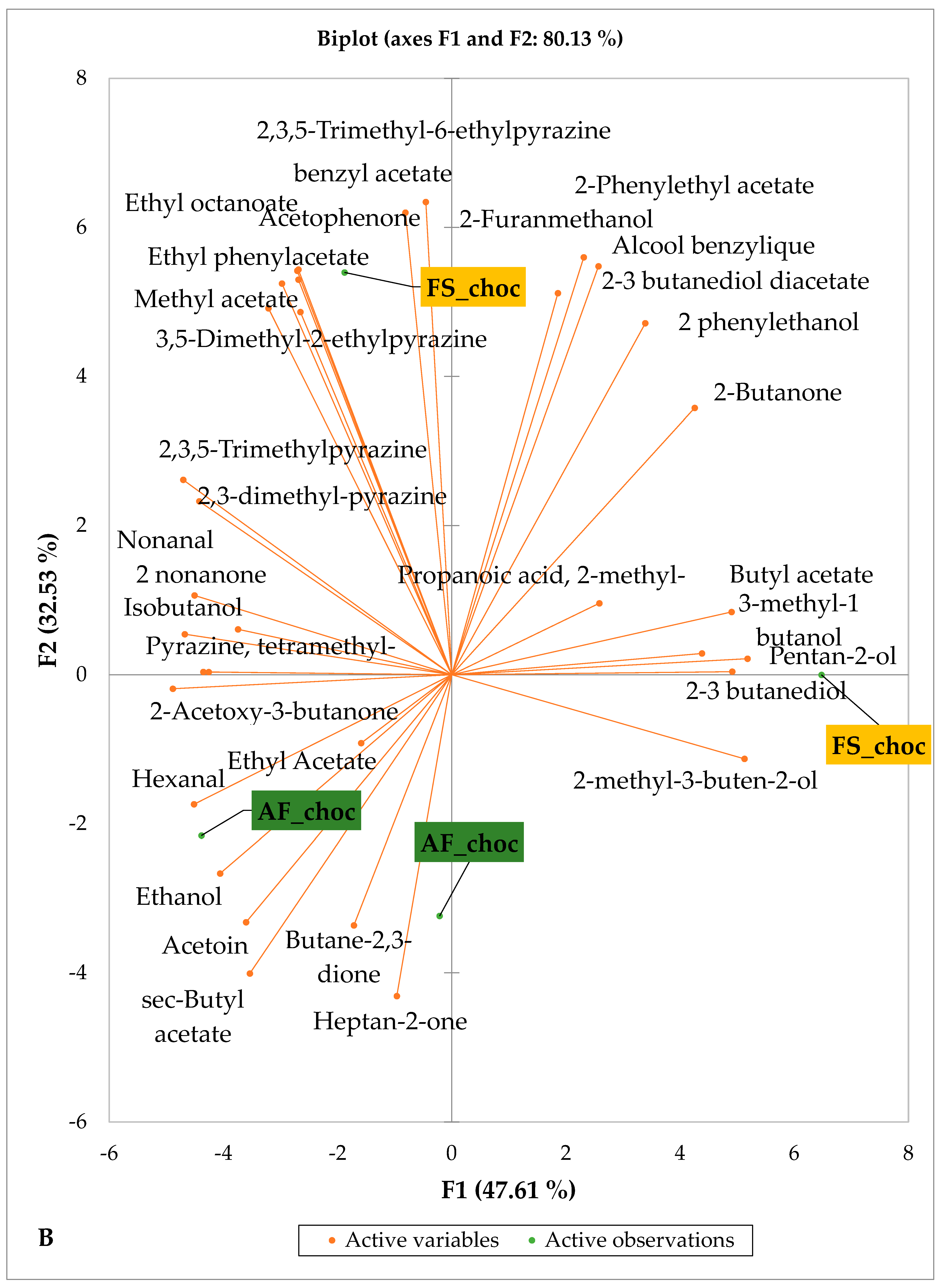

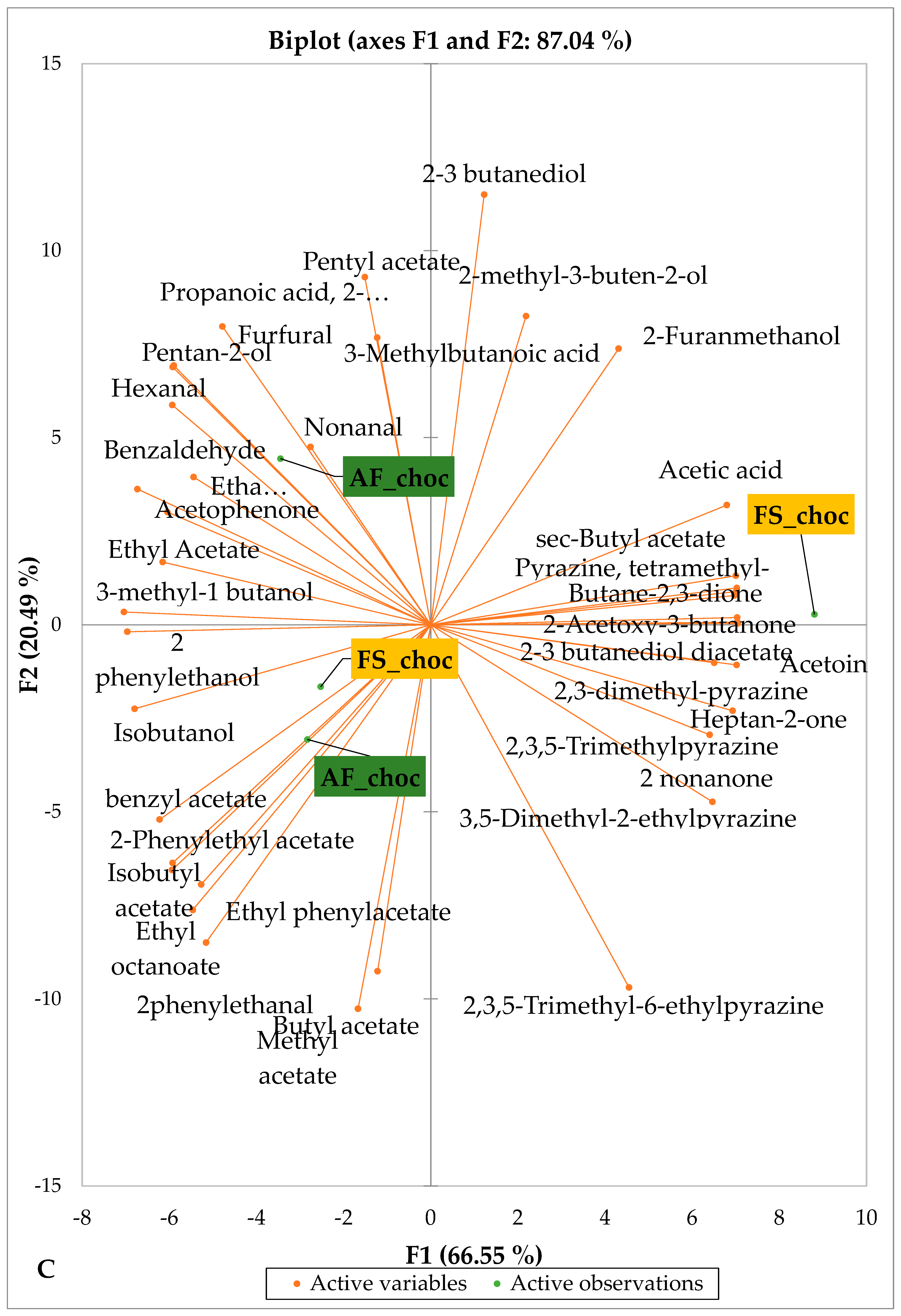

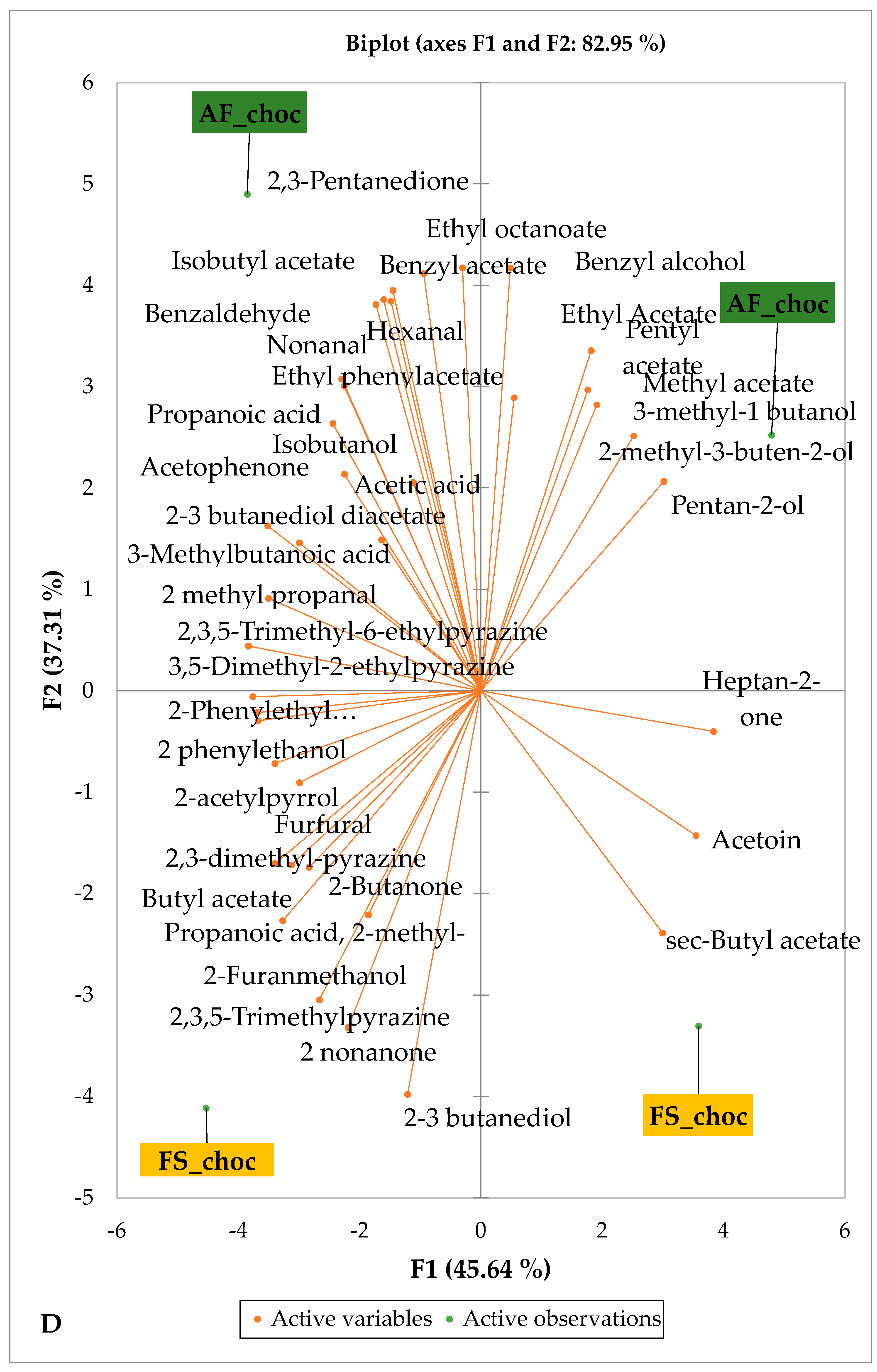

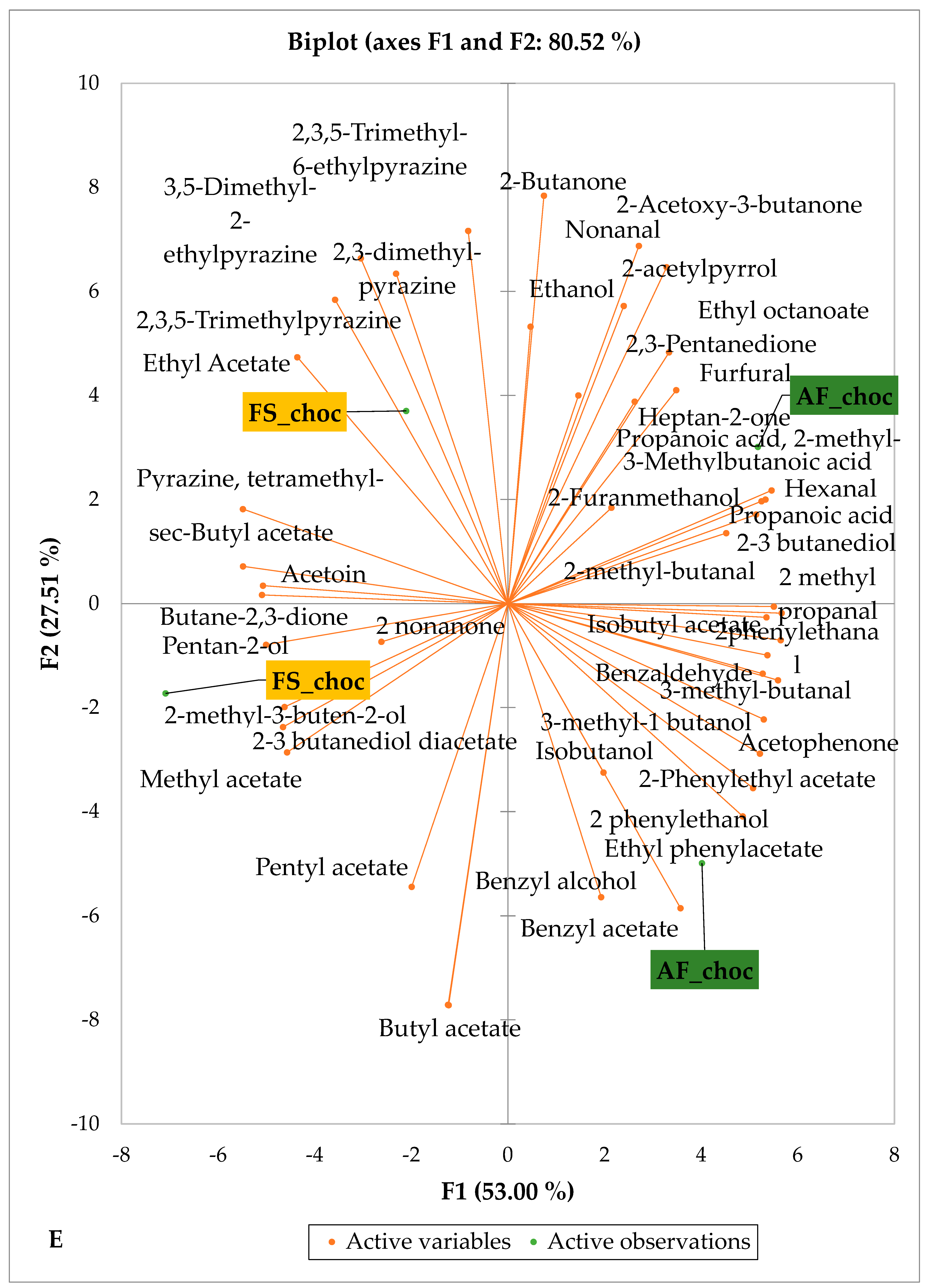

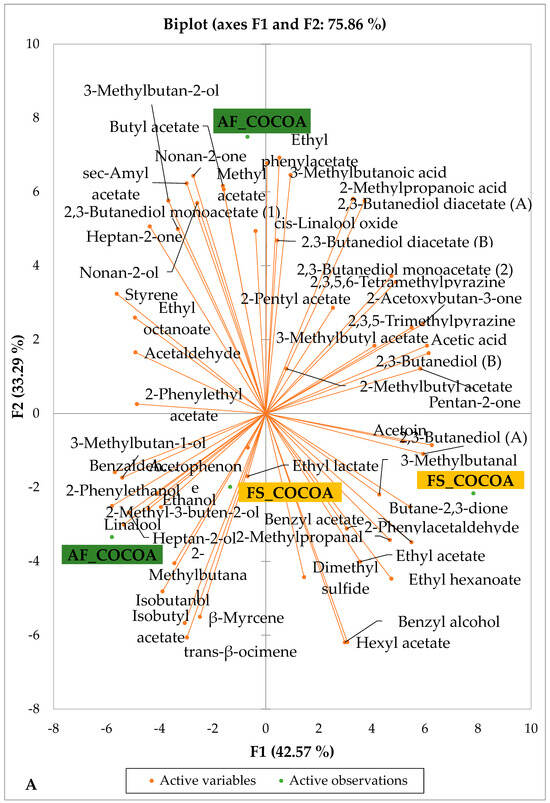

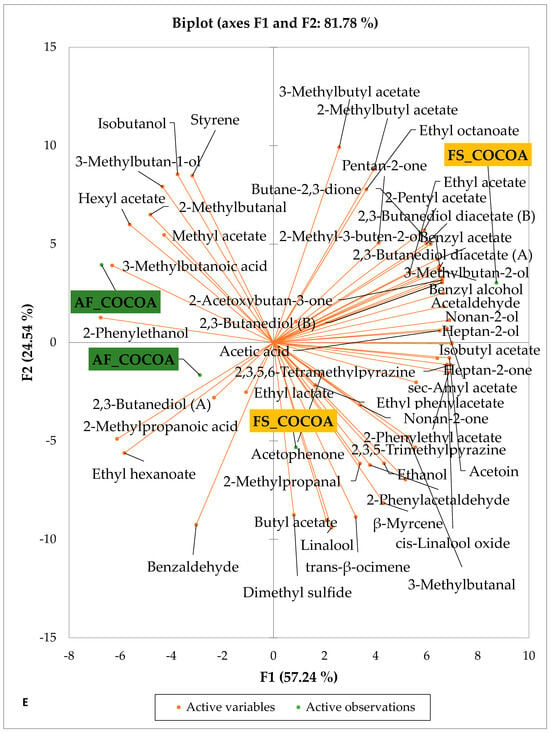

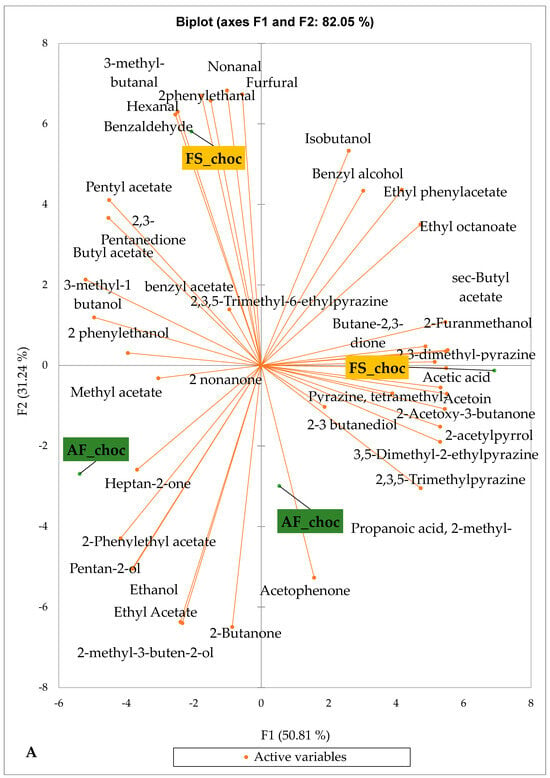

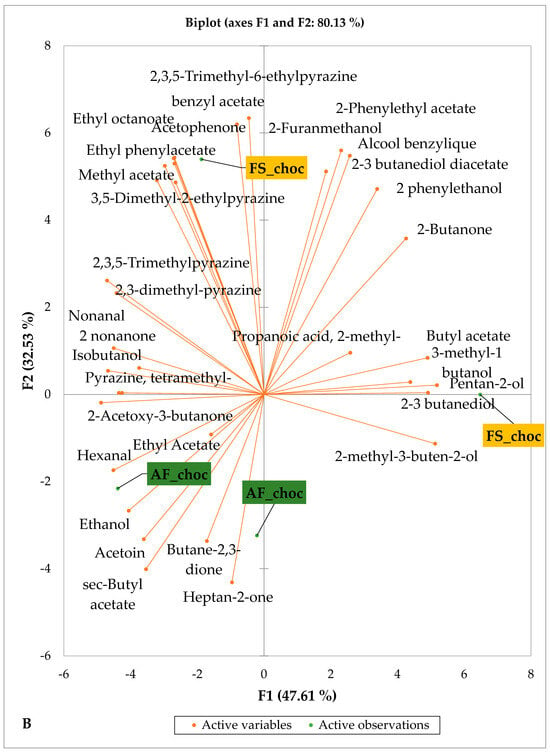

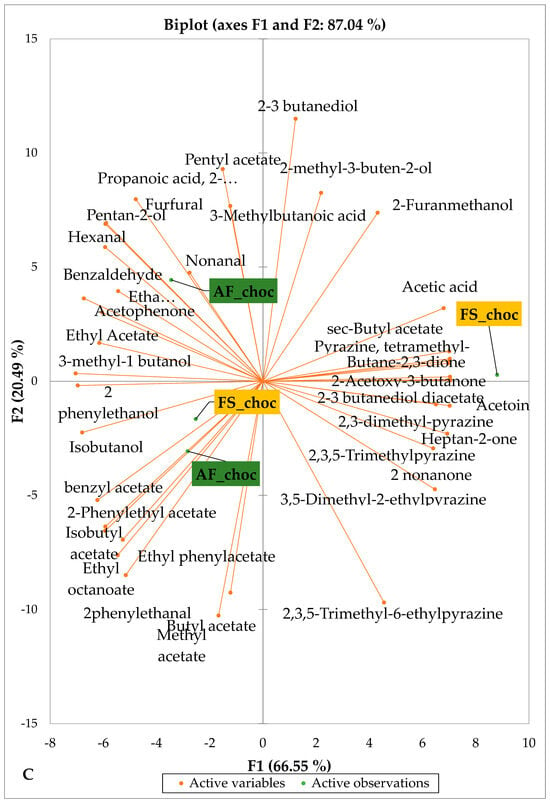

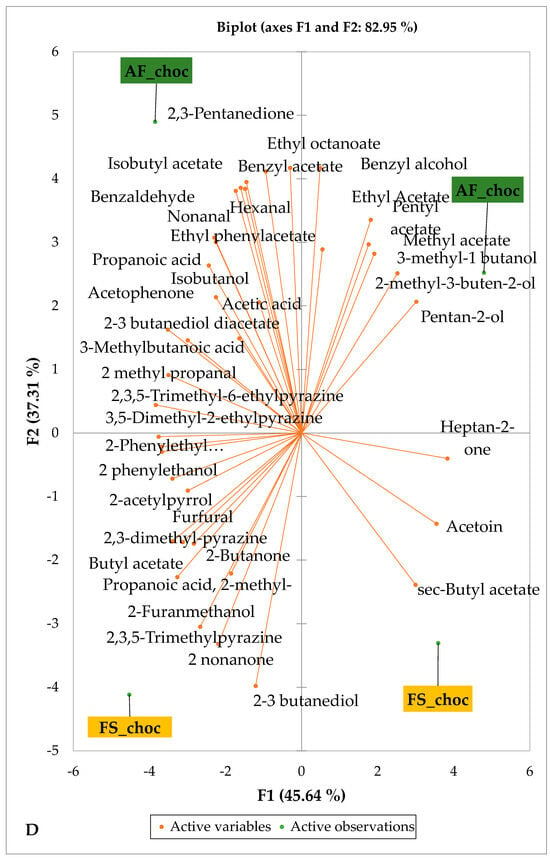

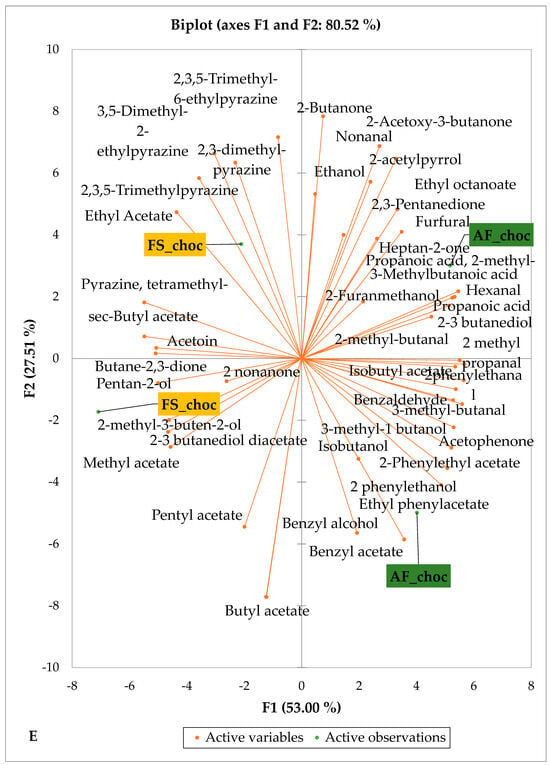

3.4. Effects of Agroforestry on the Volatile Compound Profiles of Chocolates Within Each Cocoa-Producing Area

Figure 5 and Figure 6 indicate the PCA biplot, which reveals the effects of AF on the sensory profiles of chocolate both between and within the production areas tested, respectively. The comparison between cocoa-producing areas revealed that the sensory profile of chocolate produced from AF cocoa beans was only distinctive from that of chocolate from FS cocoa beans in the Méagui region. However, our findings about each cocoa-producing area showed that the sensory compound profiles of chocolate derived from AF cocoa beans sourced from the areas of Agnibilékrou (Figure 6B) and Méagui (Figure 6E) were distinctive from those of the chocolate samples derived from FS cocoas within the corresponding areas. AF has shown no significant effect on the sensory profiles of the chocolates issued from other cocoa-producing areas: the Adzopé (Figure 6A), Divo (Figure 6C), and Guiberoua (Figure 6D) regions. The sensory profiles of AF chocolate from the Agnibilékrou region included hexanal, ethyl acetate, ethanol, sec butyl acetate, acetoin and butane-2,3-dione, while those from FS dry fermented cocoa beans included 2,3-butanediol, butyl acetate, 3 methyl butanol, pentan-2-ol, benzyl acetate, ethyl octonate, ethyl phenyl acetate, 3,5 dimethyl-2-ethyl pyrazine, acetophenone, 2-phenyl acetate, and 2,3,5-trimethyl-6-ethyl pyrazine. In the Méagui region, the chocolate derived from AF cocoa beans contained more volatile compounds (23) than those derived from FS cocoa. The sensory profile of this AF chocolate included several key volatile compounds: benzyl alcohol, iso-butanol, benzyl acetate, ethyl phenylacetate, 2-phenyl butanol, benzaldehyde, 2-phenyl ethanol, isobutyl acetate, and 3-methyl butanoic acid. Recall that the sensory profiles of AF dry fermented cocoa beans from Méagui and Agnibilekrou consist of isobutyric and isomeric acids. Isobutyric acid is present in cocoa beans, being formed during the fermentation and drying processes from the decomposition of sugars and other compounds [62]. Although it contributes to the overall sensory profile of the beans, its concentration may vary based on factors such as fermentation time, bean variety, and subsequent processing like roasting [63]. However, isovaleric acid is present in cocoa beans, where it is a volatile organic acid that develops during fermentation. It is produced by microorganisms and contributes to the acidification of the beans, though it is considered an undesirable compound when present in high concentrations, as it can produce a “rancid” smell. The sensory quality of chocolate broadly depends on the volatile compound profile resulting from microbial metabolism during cocoa bean fermentation [64]. The discrimination of the sensory profiles of chocolates derived from AF cocoa beans produced in the Agnibilékrou and Méagui regions could be due to the presence of either one, the other, or even both isovaleric and isobutyric acids.

Figure 5.

PCA biplot of sensory compounds in chocolates produced from dry fermented cocoa beans produced according to cropping system and producing region. The volatile compounds and cropping system of the cocoa-producing regions in Côte d’Ivoire are indicated on the labels at the bottom of the figure. Adz = Adzopé region; Agni = Agnibilékrou region; Divo = Divo region; Guib = Guibéroua region; Mea = Méagui region. (AF = agroforestry system; FS = full sun system).

Figure 6.

PCA biplot of sensory compounds in chocolates produced from dry fermented cocoa beans according to the cropping system within producing regions. The sensory compounds and cropping systems of the cocoa-producing regions in Côte d’Ivoire are indicated on the labels at the bottom of the figure. (AF = agroforestry system; FS = full sun system). (A) Adzopé region; (B) Agnibilékrou region; (C) Divo region; (D) Guibéroua region; (E) Méagui region.

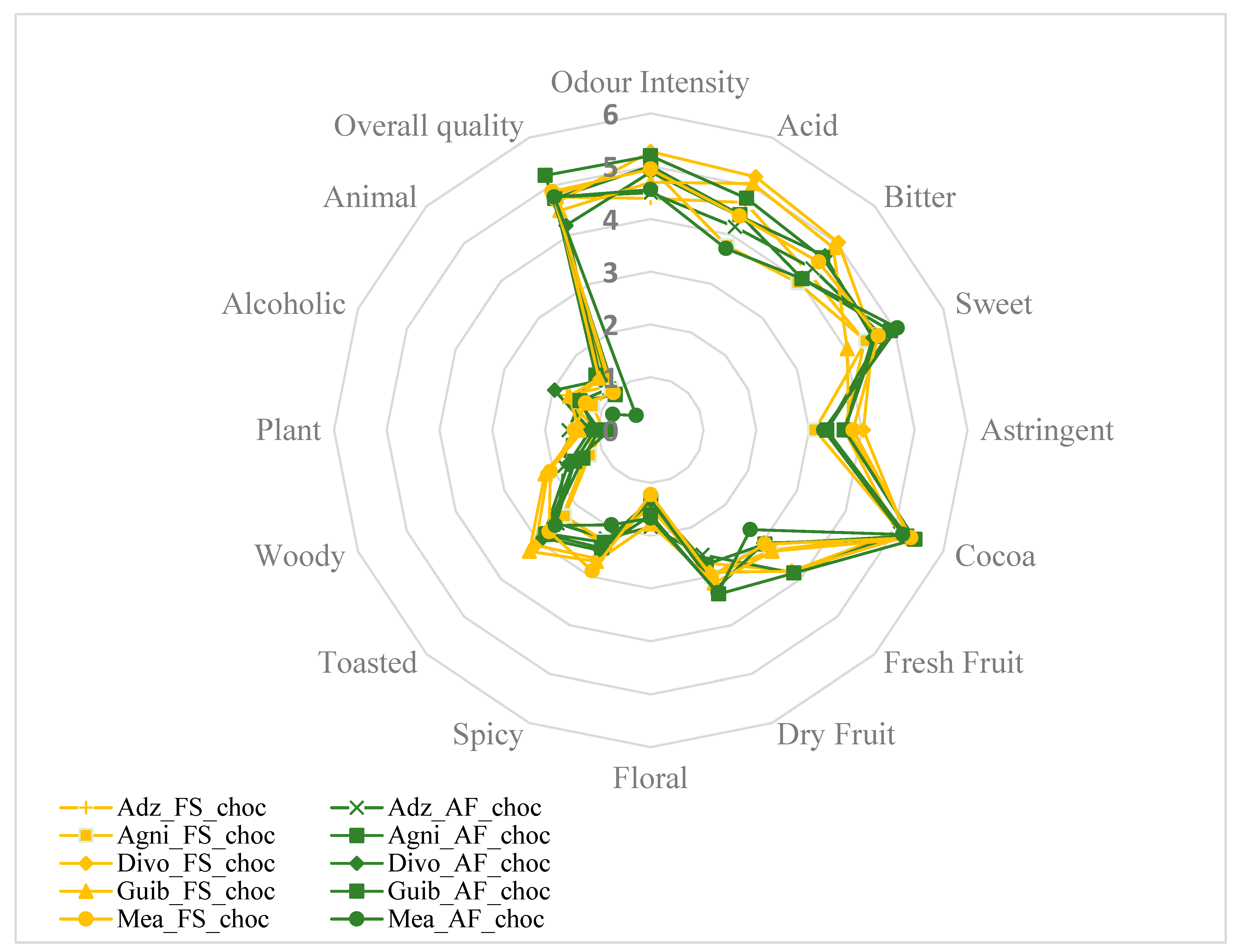

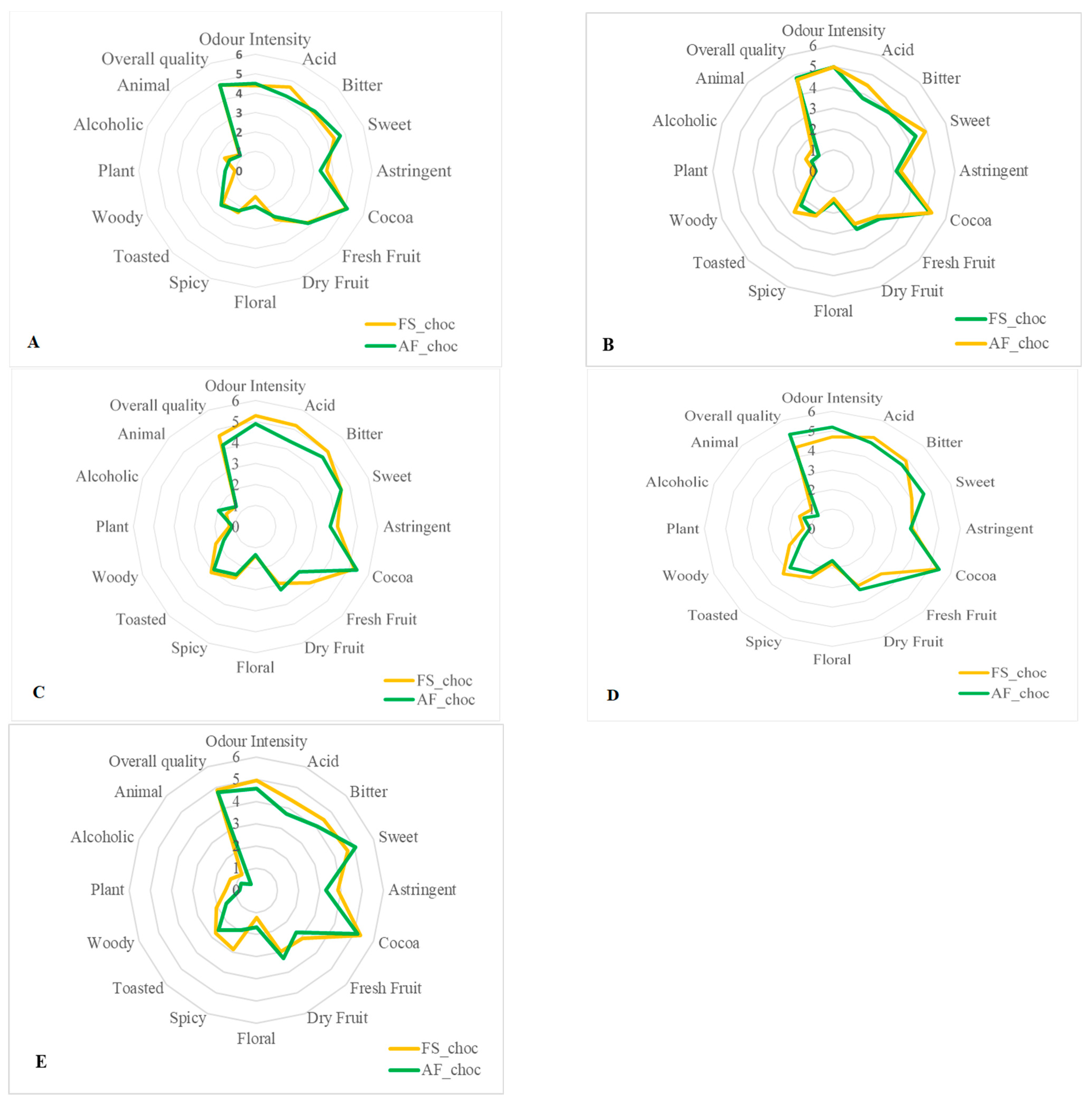

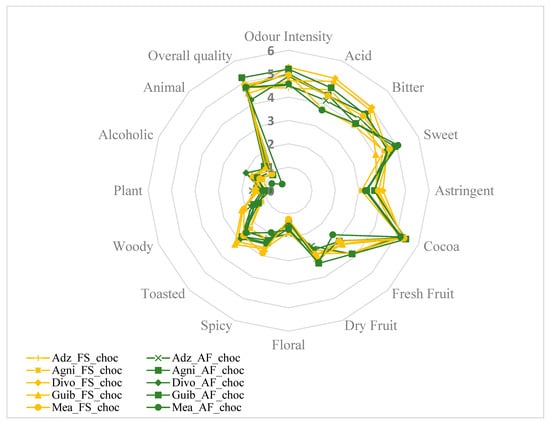

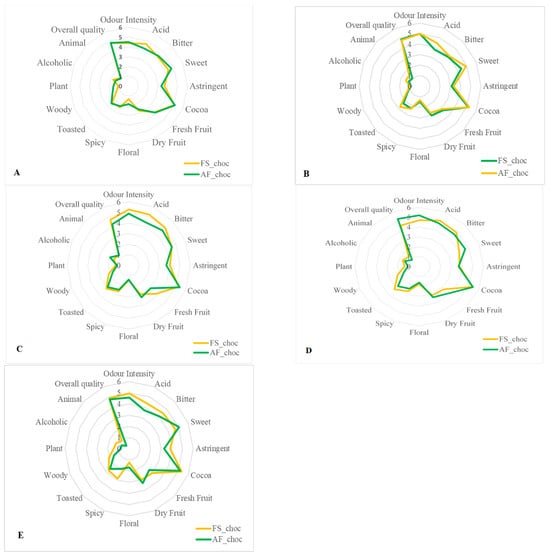

3.5. Effects of Agroforestry on the Organoleptic Quality of Chocolate Samples

Sixteen descriptive attributes, namely intensity of odor, acid, bitter, sweet, astringent, cocoa aroma, fresh fruit, dried fruit, floral, spicy, toasted, woody, plant, alcoholic aroma, animal, and global quality, were evaluated. The average of the score attributed for each sensory property to the finished chocolates from each fermented cocoa sample was then calculated. Figure 7 and Figure 8A,B show that all end-chocolate samples present the same score for almost all descriptive attributes regardless both of cropping system and geographical origin. Neither AF nor the cocoa production area influenced the sensory perception of the manufactured chocolates.

Figure 7.

Effects of agroforestry on the sensory attributes of chocolate samples made from cocoa beans between different cocoa-producing areas in Côte d’Ivoire. Adz_FS_choc: Chocolate derived from FS cocoa beans from Adzopé region; Adz_AF_choc: Chocolate derived from AF cocoa beans from Adzopé région; Agni_FS_choc: Chocolate derived from FS cocoa beans from Agnibilékrou region; Agni_AF_choc: Chocolate derived from AF cocoa beans from Agnibilékrou region; Divo_FS_choc: Chocolate derived from FS cocoa beans from Divo region; Divo_AF_choc: Chocolate derived from AF cocoa beans from Divo region; Guib_FS_choc: Chocolate derived from FS cocoa beans from Guibéroua region; Guib_AF_choc: Chocolate derived from AF cocoa beans from Guibéroua region; Méa_FS_choc: Chocolate derived from FS cocoa beans from Méagui region; Méa_AF_choc: Chocolate derived from AF cocoa beans from Méagui region.

Figure 8.

Effects of agroforestry on the sensory attributes of chocolate samples made from cocoa beans produced within each tested cocoa-producing area in Côte d’Ivoire. (A) Adzopé region, (B) Agnibilekrou region, (C) Divo region, (D) Guibéroua region, (E) Méagui region.

4. Conclusions

This paper investigated the effect of AF on the sensory profiles of cocoa beans and the chocolate’s sensory perception. The AF system significantly influenced the native sensory profiles of raw cocoa beans regardless of the geographical origin. After transformation (fermentation and roasting), the difference in sensory compound profiles is not as significant as it was in fresh cocoa beans because of the yeasts and thermal treatments such as roasting. Furthermore, the AF system influenced the volatile compound profile of both dry fermented cocoa beans and end-chocolate as a function of the cocoa-producing region, but it showed no effect on the organoleptic quality of the end-chocolate. The AF system can therefore be promoted in cocoa cultivation around the world in order to contribute to the conservation and restoration of the biosphere and ensure the sustainability of cocoa. The outcome of this work will be to evaluate the effect of both soil quality and AF featuring the same density and the same species of trees of even height on the organoleptic qualities of chocolate.

Author Contributions

F.G.K.A.: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft. M.K.K.: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft. C.A.K.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. A.K.Y.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. I.M.: Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision, Writing—reviewing and editing. R.B.: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Writing—reviewing and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. S.T.G.: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Writing—reviewing and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of the Cocoa4Future (C4F) project funded by the European DeSIRA Initiative under grant agreement No. FOOD/2019/412–132 and the French Development Agency. The C4F project brings together a wide range of expertise to address the development challenges facing West African cocoa farming. It unites numerous partners with a shared ambition to place people and the environment at the heart of the cocoa farming of tomorrow.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Under French and European Union regulations, ethical approval is not legally required for sensory studies involving adult participants provided that the research does not include sensitive personal data, does not involve vulnerable populations, and does not pose any risk to the participants’ health or well-being. The sensory evaluation was non-invasive, non-clinical, and involved no physical or psychological risk to the participants.

Informed Consent Statement

The assessors voluntarily consented to participate in the sensory analysis and authorized the use of their information under a confidentiality agreement proposed by the sensory analysis laboratory of the UMR Qualisud 95, CIRAD, Montpellier (France).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to YAPI Abe Ephrem, KOUAKOU Kouakou, KONE Clanon, ZONGO Bassiri, ALOU Daniel as Ivorian cocoa producers for all their enthusiastic work and their cooperation from the beginning of this research. We also thank anyone who has contributed directly or indirectly to the realization of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pedan, V.; Fischer, N.; Bernath, K.; Hühn, T.; Rohn, S. Determination of oligomeric proanthocyanidins and their antioxidant capacity from different chocolate manufacturing stages using the NP HPLC-online-DPPH methodology. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahurul, M.H.A.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Norulaini, N.A.N.; Sahena, F.; Jinap, S.; Azmir, J.; Sharif, K.M.; Omar, A.K.M. Cocoa butter fats and possibilities of substitution in food products concerning cocoa varieties, alternative sources, extraction methods, composition, and characteristics. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICCO. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics; Vol. L, No. 2, Cocoa year 2023/24; International Cocoa Organization: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kalischek, N.; Lang, N.; Renier, C.; Daudt, R.C.; Addoah, T.; Thompson, W.; Blaser-Hart, W.J.; Garrett, R.; Schindler, K.; Wegner, J.D. Cocoa plantations are associated with deforestation in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achaw, O.W.; Danso-Boateng, E. Cocoa Processing and Chocolate Manufacture. In Chemical and Process Industries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander Muñoz, M.; Rodríguez Cortina, J.; Vaillant, F.E.; Escobar Parra, S. An overview of the physical and biochemical transformation of cocoa seeds to beans and to chocolate: Sensory formation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 1593–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Luca, S.V.; Miron, A. Sensory chemistry of cocoa and cocoa products—An overview. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltini, R.; Akkerman, R.; Frosch, S. Optimizing chocolate production through traceability: A review of the influence of farming practices on cocoa bean quality. Food Control. 2013, 29, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Heimdal, H. Effect of fermentation method, roasting and conching conditions on the aroma volatiles of dark chocolate. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2012, 36, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongor, J.E.; Hinneh, M.; de Walle, D.V.; Afoakwa, E.O.; Boeckx, P.; Dewettinck, K. Factors influencing quality variation in cocoa (Theobroma cacao) bean sensory profile—A review. Food Res. Int. 2016, 82, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.J.R.; Almeida, M.H.; Nout, M.R.; Zwietering, M.H. Theobroma cacao L., “The food of the Gods”: Quality determinants of commercial cocoa beans, with particular reference to the impact of fermentation. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 731–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadow, D.; Niemenak, N.; Rohn, S.; Lieberei, R. Fermentation-like Incubation of Cocoa Seeds (Theobroma cacao L.)—Reconstruction and Guidance of the Fermentation Process. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hue, C.; Gunata, Z.; Breysse, A.; Davrieux, F.; Boulanger, R.; Sauvage, F.X. Impact of fermentation on nitrogenous compounds of cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) from various origins. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Weckx, S. The cocoa bean fermentation process: From ecosystem analysis to starter culture development. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafack, M.; Mikkelsen, M.B.; Saerens, S.; Knudsen, M.; Blennow, A.; Lowor, S.; Takrama, J.; Swiegers, J.H.; Petersen, G.B.; Heimdal, H.; et al. Influencing cocoa sensory using Pichia kluyveri and Kluyveromyces marxianus in a defined mixed starter culture for cocoa fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 167, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.; Lieberei, R. Biochemistry of cocoa fermentation. In Cocoa and Coffee Fermentations; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Quao, J.; Takrama, J.; Budu, A.S.; Saalia, F.K. Chemical composition and physical quality characteristics of Ghanaian cocoa beans as affected by pulp pre-conditioning and fermentation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanquah, D.T. Effect of Mechanical Depulping on the Biochemical, Physicochemicaland Polyphenolic Constituents During Fermentation and Drying of Ghanaian Cocoa Beans. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Paitan, C.; Meyfroidt, P.; Verburg, P.H.; Zu Ermgassen, E.K. Deforestation and climate risk hotspots in the global cocoa value chain. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 158, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraatpisheh, M.; Bakhshandeh, E.; Hosseini, M.; Alavi, S.M. Assessing the effects of deforestation and intensive agriculture on the soil quality through digital soil mapping. Geoderma 2020, 363, 114139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, G.; da Fonseca, G.A.; Harvey, C.A.; Gascon, C.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; Izac, A.M.N. (Eds.) Agroforestry and Biodiversity Conservation in Tropical Landscapes; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; 523p. [Google Scholar]

- Somarriba, E.; Saj, S.; Orozco-Aguilar, L.; Somarriba, A.; Rapidel, B. Shade canopy density variables in cocoa and coffee agroforestry systems. Agroforest Syst. 2024, 98, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middendorp, R.S.; Vanacker, V.; Lambin, E.F. Impacts of shaded agroforestry management on carbon sequestration, biodiversity and farmers income in cocoa production landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 33, 1953–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.B.; Rawale, G.B.; Pradhan, A.; Uthappa, A.R.; Kakade, V.D.; Morade, A.S.; Paul, N.; Das, B.; Chichaghare, A.R.; Changan, S.; et al. Optimizing tree shade gradients in Emblica officinalis-based agroforestry systems: Impacts on soybean physio-biochemical traits and yield under degraded soils. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; McGraw, M.L.; George, M.F.; Garret, S.E. Nutritive quality and morphological development under partial shade of some forage species with agroforestry potential. Agrofor. Syst. 2001, 53, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guehi, T.S.; Dadie, A.T.; Koffi, K.P.; Dabonne, S.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Kedjebo, K.D.; Nemlin, G.J. Performance of different fermentation methods and the effect of their duration on the quality of raw cocoa beans. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 2508–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouassi, A.D.D.; Koné, K.M.; Assi-Clair, B.J.; Lebrun, M.; Maraval, I.; Boulanger, R.; Guéhi, T.S. Effect of spontaneous fermentation location on the fingerprint of volatile compound precursors of cocoa and the sensory perceptions of the end-chocolate. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 4466–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koné, M.K.; Guéhi, S.T.; Durand, N.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Berthiot, L.; Tachon, A.F.; Brou, K.; Boulanger, R.; Montet, D. Contribution of predominant yeasts to the occurrence of aroma compounds during cocoa bean fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.B.; Amorim, L.R.; Nonato, M.A.; Roselino, M.N.; Santana, L.R.; Ferreira, A.C.; Rodrigues, F.M.; Mesquita, P.R.R.; Soares, S.E. Optimization of HS-SPME/GC-MS method for determining volatile organic compounds and sensory profile in cocoa honey from different cocoa varieties (Theobroma cacao L.). Molecules 2024, 29, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi-Clair, B.J.; Koné, M.K.; Kouamé, K.; Lahon, M.C.; Berthiot, L.; Durand, N.; Lebrun, M.; Julien-Ortiz, A.; Maraval, I.; Boulanger, R.; et al. Effect of aroma potential of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation on the volatile profile of raw cocoa and sensory attributes of chocolate produced thereof. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1459–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander, M.; Leguizamón, L.; Vaillant, F.; Boulanger, R.; Zuluaga, M.; Maraval, I.; Rodriguez, J.; Liano, S.; Sommerer, N.; Meudec, E.; et al. Influence of driven fermentation of cacao in bioreactors on quality: Decoding the effect of temperature, mixing, and pH on metabolomic, sensory, and volatile profiles. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 231, 118313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wu, B.; Qin, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Yan, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, G.; Li, F. Quality differences and profiling of volatile components between fermented and unfermented cocoa seeds (Theobroma cacao L.) of Criollo, Forastero and Trinitario in China. Beverage Plant Res. 2024, 4, e010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzwieser, J.; Schnitzler, J.P.; Steinbrecher, R. Biosynthesis of organic compounds emitted by plants. Plant Biol. 1999, 1, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmerer, T.W.; MacDonald, R.C. Acetaldehyde and ethanol biosynthesis in leaves of plants. Plant Physiol. 1987, 84, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missihoun, T.D.; Kotchoni, S.O. Aldehyde dehydrogenase and the hypotheisis of a glycolaldehyde shunt pathway of photorespiration. Plant Signal. Behav. 2018, 13, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Li, R.; Chu, Z.; Zhu, K.; Gu, F.; Zhang, Y. Chemical and sensory profile changes of cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) during primary fermentation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 4121–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konan, G.D.; Kpangui, K.B.; Kouakou, K.A.; Barima, Y.S.S. Typology of cocoa-based agroforestry systems according to the cocoa production gradient in Côte d’Ivoire. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2023, 17, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvadet, M.; Van den Meersche, K.; Allinne, C.; Gay, F.; de Melo Virginio Filho, E.; Chauvat, M.; Becquer, T.; Tixier, P.; Harmand, J.M. Shade trees have higher impact on soil nutrient availability and food web in organic than conventional coffee agroforestry. Sci. Tot. Environ. 2019, 649, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, K.M.; Assi-Clair, B.J.; Kouassi, A.D.D.; Yao, A.K.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Durand, N.; Guéhi, T.S. Pod storage time and spontaneous fermentation treatments and their impact on the generation of cocoa flavour precursor compounds. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 2516–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseglia, A.; Musci, M.; Rinaldi, M.; Palla, G.; Caligiani, A. Volatile fingerprint of unroasted and roasted cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) from different geographical origins. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottiers, H.; Tzompa Sosa, D.A.; De Winne, A.; Ruales, J.; De Clippeleer, J.; De Leersnyder, I.; De Wever, J.; Everaery, H.; Messens, K.; Dewettinck, K. Dynamique des composés volatils et des précurseurs d’arômes lors de la fermentation spontanée de fèves de cacao Trinitario de qualité supérieure. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1917–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Contreras-Ramos, S.M.; Orozco-Avila, I.; Jaramillo-Flores, E.; Lugo-Cervantes, E. Effect of fermentation time and drying temperature on volatile compounds in cocoa. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinap, S.; Ikrawan, Y.; Bakar, J.; Saari, N.; Lioe, H.N. Aroma precursors and methylpyrazines in under fermented cocoa beans induced by endogenous carboxy peptidase. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puziah, H.; Jinap, S.; Sharifah, K.S.M.; Asbi, A. Changes free amino acid, peptide, sugar and pyrazine concentration during cocoa fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 78, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Ramli, N.; Hassan, O.; Said, M.; Samsudin, W.; Idris, N.A. Influence of roasting conditions on volatile sensory of roasted Malaysian cocoa beans. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2006, 30, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.T.T.; Zhao, J.; Fleet, G. Yeasts are essential for cocoa bean fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 174, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayek, N.M.; Xiao, J.; Farag, M.A. A multifunctional study of naturally occurring pyrazines in biological systems; formation mechanisms, metabolism, food applications and functional properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 5322–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, H.G.; Koffi, B.L.; Karou, G.T.; Sangaré, A.; Niamke, S.L.; Diopoh, J.K. Implication of Bacillus sp. in the production of pectinolytic enzymes during cocoa fermentation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 24, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reineccius, G.A.; Keeney, P.G.; Weissberger, W. Factors affecting the concentration of pyrazines in cocoa beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1972, 20, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinneh, M.; Semanhyia, E.; Van de Walle, D.; De Winne, A.; Tzompa-Sosa, D.A.; Scalone, G.L.L.; De Meulenaer, B.; Messens, K.; Durme, J.V.; Afoakwa, E.O.; et al. Assessing the influence of pod storage on sugar and free amino acid profiles and the implications on some Maillard reaction related sensory volatiles in Forastero cocoa beans. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouamé, C.; Loiseau, G.; Grabulos, J.; Boulanger, R.; Mestres, C. Development of a model for the alcoholic fermentation of cocoa beans by a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 337, 108917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetschik, I.; Pedan, V.; Chatelain, K.; Kneubühl, M.; Hühn, T. Characterization of the sensory properties of dark chocolates produced by a novel technological approach and comparison with traditionally produced dark chocolates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3991–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, P.; Frey, L.J.; Berger, A.; Bolten, C.J.; Hansen, C.E.; Wittmann, C. The key to acetate: Metabolic fluxes of acetic acid bacteria under cocoa pulp fermentation-simulating conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 4702–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafack, M.; Keul, H.; Eskildsen, C.E.; Petersen, M.A.; Saerens, S.; Blennow, A.; Skovmand-Larsen, M.; Swiegers, J.H.; Petersen, G.B.; Heimdal, H.; et al. Impact of starter cultures and fermentation techniques on the volatile aroma and sensory profile of chocolate. Food Res. Int. 2014, 63, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meersman, E.; Steensels, J.; Struyf, N.; Paulus, T.; Saels, V.; Mathawan, M.; Allegaert, L.; Vrancken, G.; Verstrepen, K.J. Tuning chocolate sensory through development of thermotolerant Saccharomyces cerevisiae starter cultures with increased acetate ester production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 732–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Ríos, H.G.; Suárez-Quiroz, M.L.; Hernández-Estrada, Z.J.; Castellanos-Onorio, O.P.; Alonso-Villegas, R.; Rayas-Duarte, P.; Cano-Sarmiento, C.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.Y.; González-Rios, O. Yeasts as producers of sensory precursors during cocoa bean fermentation and their relevance as starter cultures: A review. Fermentation 2022, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegleder, G. Composition of Sensory Extracts of Raw and Roasted Cocoas. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1991, 192, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegleder, G. Linalool Contents as Characteristic of Some Sensory Grade Cocoas. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1990, 191, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Chen, K.F.; Changchien, L.L.; Chen, K.C.; Peng, R.Y. Volatile variation of Theobroma cacao Malvaceae L. beans cultivated in Taiwan affected by processing via fermentation and roasting. Molecules 2022, 27, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdouche, Y.; Meile, J.C.; Lebrun, M.; Guehi, T.; Boulanger, R.; Teyssier, C.; Montet, D. Impact of turning, pod storage and fermentation time on microbial ecology and volatile composition of cocoa beans. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selamat, J.; Mordingah Harun, S. Formation of methyl pyrazine during cocoa bean fermentation. Pertanika 1994, 17, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Orozco-Avila, I.; Lugo-Cervantes, E.; Jaramillo-Flores, M.E. Dynamics of volatile and non-volatile compounds in cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) during fermentation and drying processes using principal components analysis. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauendorfer, F.; Schieberle, P. Changes in key aroma compounds of Criollo cocoa beans during roasting. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 10244–10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, A.B.; da Cruz, M.L.; de Souza Oliveira, F.A.; Soares, S.; Druzian, J.I.; de Santana, L.R.R.; de Souza, C.O.; da Silva Bispo, E. Influence of under-fermented cocoa mass in chocolate production: Sensory acceptance and volatile profile characterization during the processing. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 149, 112048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).