Boosting Food System Stability Through Technological Progress in Price and Supply Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

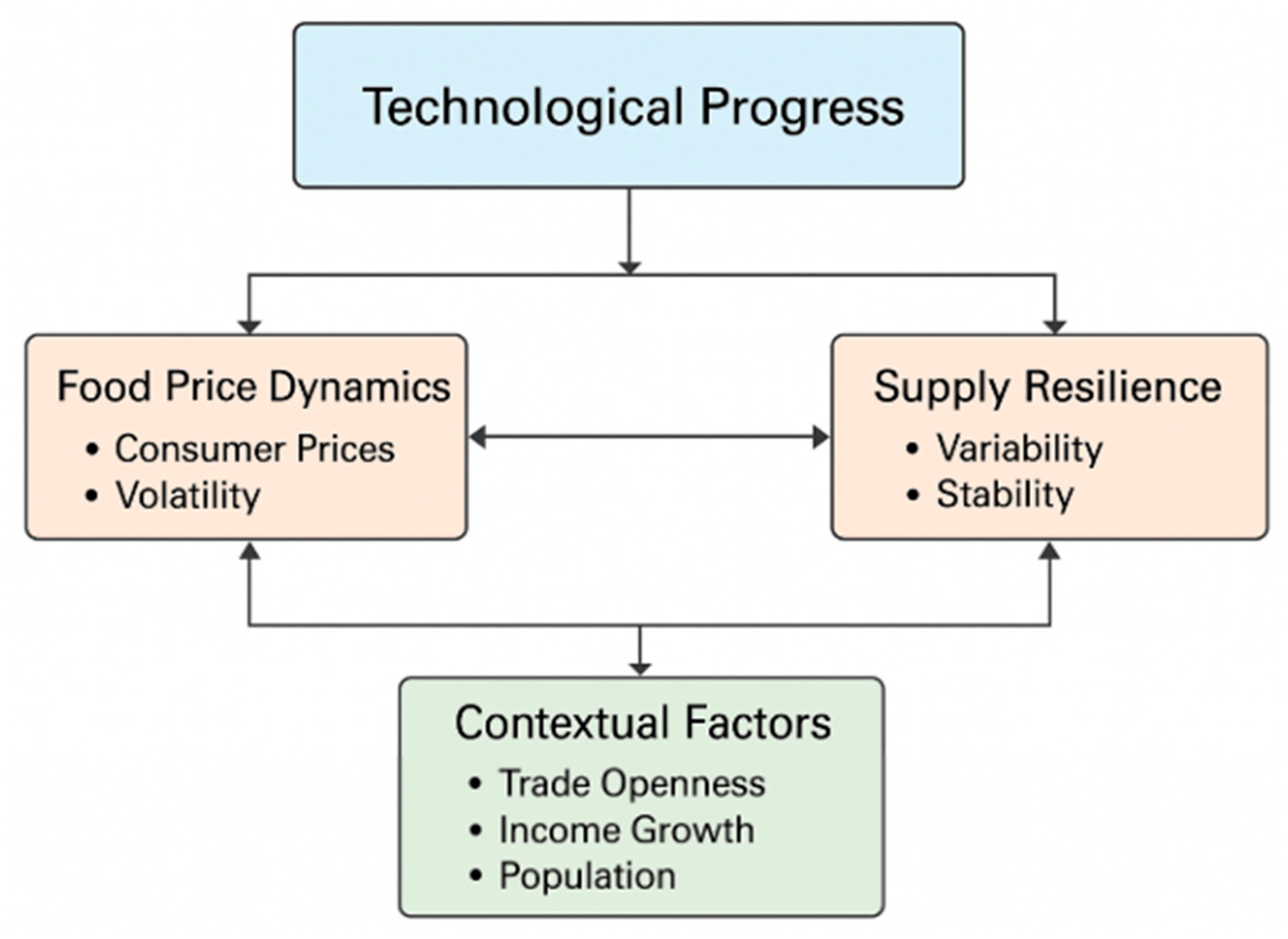

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Variables Description

3.2. Methodology

4. Results and Discussions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 (SOFI 2024); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy—For a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal, COM(2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, C.L.; Morgan, C.W. Food price volatility. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 3023–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Making Better Policies for Food Systems; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, K.R.; Fanzo, J.; Haddad, L.; Herrero, M.; Moncayo, J.R.; Herforth, A.; Remans, R.; Guarin, A.; Resnick, D.; Covic, N.; et al. The state of food systems worldwide in the countdown to 2030. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 1090–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Food Security Indicators—Descriptions and Metadata (FAOSTAT); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; UN Statistics Division. SDG 2.c.1—Indicator of Food Price Anomalies (IFPA): Metadata; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Domestic Food Price Volatility—Definition and Method (Metadate FAO); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Headey, D.; Fan, S. Reflections on the Global Food Crisis: How Did It Happen? How Has It Hurt? And How Can We Prevent the Next One? IFPRI Research Monograph: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 165. [Google Scholar]

- Baquedano, F.G.; Liefert, W.M. Market integration and price transmission in consumer markets of developing countries. Food Policy 2014, 44, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, C.P. Reflections on food crises past. Food Policy 2010, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.L.Z.; Ávila Hierrezuelo, N.D.; Acosta Roca, R.A. Open innovation in Cuba: Experience of the Local Agricultural Innovation Program (PIAL). GECONTEC Rev. Int. Gestión Conoc. Tecnol. 2023, 11, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger, S.; Darr, D.; Oude Lansink, A.G.J.M.; Saatkamp, H.W. The influence of the cross-border innovation environment on innovation processes in agri-food enterprises—A case study from the Dutch-German Rhine-Waal region. NJAS Impact Agric. Life Sci. 2023, 95, 2194259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawati, H.; Caska, C.; Hermita, N.; Sumarno, S.; Syahza, A. Green innovation adoption of SMEs in Indonesia: What factors determine it? Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2025, 17, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhunushalieva, G.D.; Teuber, R. A bibliometric analysis of trends in the relationship between innovation and food. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1554–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, J.; Festa, G.; Alam, G.M.; Rossi, M. Ownership structure and technological innovation: An investigation of Tunisian agri-food companies. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny-Sicart, A.; Pansera, M.; Lloveras, J. Directing innovation through confrontation and democratisation: The case of platform cooperativism. J. Responsible Innov. 2024, 11, 2414512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Fu, Z.Y.; Jia, L.; Li, Q.H.; Song, J.H. Impact of digital technology adoption on technological innovation in grain production. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.S.; Sun, Z.Y.; Deng, F.; Yan, C.Z.; Zhu, R.N. Impact of Technological Innovation on Global Crop Export Trade: The Example of Innovation in GM Technology. Food Energy Secur. 2025, 14, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marozzo, V.; Abbate, T.; Cesaroni, F.; Crupi, A.; Di Minin, A. Orchestrating an Open Innovation Ecosystem in low-tech industries: The case of Barilla’s Blu1877. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 36, 3712–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranieri, S.; Orsi, L.; De Noni, I.; Olper, A. Geographical Indications and Innovation: Evidence from EU regions. Food Policy 2023, 116, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Banegas, N.; Sánchez-Garcia, M.; Calafat-Marzal, C.; Roig-Tierno, N. Transforming the agri-food sector through eco-innovation: A path to sustainability and technological progress. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 9075–9097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, I.C.C.; García, A.G.R. Curricular Innovation for Food Security. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, S.; O’Shea, G.; Hakala, H. Scaling sustainable technologies by creating innovation demand-pull: Strategic actions by food producers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 198, 122941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, Z.Y.; Liu, C.X.; Ding, J.H.; Zheng, J.X.; Zhang, C.M.; Li, H.Y. A study of the impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onumah, E.E.; Dogbey, M.J.M.; Asem, F.E. Impact analysis of innovation and gendered constraints in the fisheries sector of southern Ghana. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2023, 15, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujor, A.; Avasilcai, S. Open Innovation in the Creative Industries: A case study of an Italian food company. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2024, 23, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, T.; Monaco, A. How innovation-friendly is the EU novel food regulation? The case of cellular agriculture. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.A.; Santos, S.S.; de Araújo, M.A.; Vinderola, G.; Villarreal, C.F.; Viana, M.D.M. Probiotics as technological innovations in psychiatric disorders: Patents and research reviews. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1567097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onegina, V.; Kucher, L.; Kucher, A.; Krupin, V.; Klodzinski, M.; Logos, V. Unlocking Innovation Capacity: Strategies for Micro-, Small, and Medium Enterprises in Ukrainian Agriculture. Agriculture 2025, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thann, O.H.; Yuhuan, Z.; Uddin, M.; Zuo, S.M. Technological innovation and agricultural performance in the ASEAN region: The role of digitalization. Food Policy 2025, 135, 102939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.O.; Nwulu, N.I.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Adepoju, O.O. Resource sustainability in the water, energy and food nexus: Role of technological innovation. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2025, 23, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onumah, E.E.; Asem, F.E.; Dogbey, M. Gendered perception and factors influencing the choice of innovation in the fisheries sector: A case of southern Ghana. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 252, 107103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Ekren, B.Y.; Kazancoglu, Y.; Luthra, S.; Prasad, M. Assessing Supply Chain Innovations for Building Resilient Food Supply Chains: An Emerging Economy Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.A.; Young, M.J. Doctors as Device Manufacturers? Regulation of clinician-generated innovation in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 52, 1941–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranieri, S.; Orsi, L.; Zilia, F.; De Noni, I.; Olper, A. Terroir takes on technology: Geographical indications, agri-food innovation, and regional competitiveness in Europe. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 110, 103368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgia, R.; Zavalloni, M.; Viaggi, D. Importance of different policy instruments in the introduction of sustainable innovation in fruit and vegetable value chains: The perception of coordinators of European research and innovation projects. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 119, 103695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulah, B.M.; Negro, S.O.; Beumer, K.; Hekkert, M.P. Institutional work as a key ingredient of food innovation success: The case of plant-based proteins. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2023, 47, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletto, C.; Caliari, L.; Callegaro-de-Menezes, D. Scientific and technological parks in innovation ecosystems: The proposition of an analytical structure. Compet. Rev. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Wu, S.W.; Wan, X.Y. Restructuring strategies for crop seed industry innovation: Challenges and prospects. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 3012–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhao, J.H.; Lei, T.; Shi, L.D.; Tan, Y.T.; He, L.P.; Ai, R. The influence mechanism of environmental regulations on food security: The mediating effect of technological innovation. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konfo, T.R.C.; Chabi, A.B.P.; Gero, A.A.; Lagnika, C.; Avlessi, F.; Biaou, G.; Sohounhloue, C.K.D. Recent climate-smart innovations in agrifood to enhance producer incomes through sustainable solutions. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.L.; Hong-Hue, T.H.; Thai, H.C.V. Growth Beyond Borders: How Technological Innovation and Agricultural Competitiveness Propel Agri-venture Internationalisation. J. Entrep. 2024, 33, 581–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondwe, G. Framing the Schemata: Western Media Coverage of African Technological Innovations. J. Media 2024, 5, 1901–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix-Domènech, R.; Sforzi, F.; Galletto, V.; Capone, F. Born to innovate, not to produce: Three decades of compared change, evolution and innovation in the dynamic Marshallian Industrial Districts of Spain and Italy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2025, 33, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.D.D.; Herrera, Y.D.; Abreu, M.B.I.; Rodriguez, P.P.D.; Roca, R.A. Technological Ecosystem Conceptualization for Cuban National System of Science and Agrarian Technological Innovation. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2023, 15, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquero-Piñeiro, C.; Pierucci, E. Spirit of Innovation or Historical Tradition? The Complex Dilemma of EU Policy for Renowned Products. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2025, 135, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mahajan, A.; Virmani, N.; Kumar, P.; Vishnoi, S.K. Analyzing the role of convergence innovation in addressing raised hygiene sensitivity norms in the tourism industry. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2025, 16, 3452–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.D.; Zawislak, P.A. Towards a theory of Capability-Based Transactions: Bounded innovation capabilities, commercialization, cooperation, and complementarity. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, C.; Morgante, A. New Solutions for Old Problems: Exploring Business Model Innovation in Food Sharing Platforms. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2025, 34, 5742–5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marn-García, A.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Berenguer-Contreras, G. Capturing consumer loyalty through technological innovation and sustainability: The moderating effect of the grocery commercial format. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 2764–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, D.; Grudowska, J.; Lewandowski, P. Innovation governance in Poland. Technological Trends with An Outlook to 2030. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekpour, M.; Caboni, F.; Nikzadask, M.; Basile, V. Taste of success: A strategic framework for product innovation in the food and beverage industry. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 94–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.L.; Wang, X.C. The Impact of Technological Innovations on Agricultural Productivity and Environmental Sustainability in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 98480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, J.; Javed, A. The Role of Technological Innovation and Renewable Energy in Sustainable Development: Reducing the Carbon Footprint of Food Supply Chains. Sustain. Dev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, T.; Hartley, K.; Hekkert, M.; Kirchherr, J. Building innovation ecosystems for circularity: Start-up business models in the food and construction sectors in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 481, 143970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudy, M.C.; Parkinson, M.; Aquino, K. Why should innovators care about morality? Political ideology, moral foundations, and the acceptance of technological innovations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 203, 123384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, M.X.; Picavet, M.E.B.; de Oliveira, J.A.P. Innovation in small municipalities: The case of waste management. Habitat Int. 2025, 165, 103554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Consumer Price Index, Food (2015 = 100); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators—Consumer Price Index, Food (Annual % Change); The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Security Indicators—Food Price Volatility (Index and %); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Security Indicators—Food Supply Variability (kcal/capita/day); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- WIPO; INSEAD; Cornell University. Global Innovation Index Database (2011–2024 Editions); World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Trade Openness (% of GDP) (NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS); World Development Indicators, The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. GDP per Capita Growth (Annual %, Constant LCU) (NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG); World Development Indicators, The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Total Population (Log-Transformed in Models); World Development Indicators, The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Baltagi, B.H. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data, 6th ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, A.; Lin, C.F.; Chu, C.S.J. Unit Root Tests in Panel Data: Asymptotic and Finite-Sample Properties. J. Econom. 2002, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels. J. Econom. 2003, 115, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.A. Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econometrica 1978, 46, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H. A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 1980, 48, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Serial Correlation and Misspecification Tests in Panel Data Models. J. Econom. 2010, 162, 112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H. General Diagnostic Tests for Cross Section Dependence in Panels. Empir. Econ. 2021, 60, 13–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D.N.; Porter, D.C.; Gunasekar, S. Basic Econometrics, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023: Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets across the Rural–Urban Continuum; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ianchovichina, E.; Loening, J. What Drives Food Price Volatility? Evidence from the Global Markets; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5642; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- d’Amour, C.B.; Wenz, L.; Kalkuhl, M.; Steckel, J.C.; Creutzig, F. Teleconnected Food Supply Shocks. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 035007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Competitiveness Report 2023: Trade, Innovation, and Industrial Resilience in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H. Time Series and Panel Data Econometrics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baltagi, B.H.; Kao, C. Nonstationary Panels, Cointegration in Panels and Dynamic Panels: A Survey. Adv. Econom. 2000, 15, 7–51. [Google Scholar]

- Magazzino, C.; Gattone, T.; Usman, M.; Valente, D. Unleashing the Power of Innovation and Sustainability: Transforming Cereal Production in the BRICS Countries. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camel, A.; Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Wetzels, M.; Touriki, F.E. Servitizing for Sustainability. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 189, 115166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, B. Technological Innovations in Food Grain Processing and Storage in India. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 114, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, G.; de Mattos, C.S.; Otter, V.; Hagelaar, G. Exploring How EU Agri-Food SMEs Approach Technology-Driven BMI. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2023, 26, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Sun, M.X.; Wu, J.Y. Potential of Technological Innovation to Reduce the Carbon Footprint of Urban Facility Agriculture. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 339, 117806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.; D’CRoz, D.M.; Kugler, C.; Remans, R.; Zornetzer, H.; Herrero, M. Enabling Food System Innovation: Accelerators for Change. Glob. Food Secur. 2024, 40, 100738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, L.; Andersson, J.; Fernqvist, N. Business Model Innovation in Food System Transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2025, 57, 101027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, P.; Cassia, F.; Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Giaretta, E. Food Innovation towards a Sustainable World: Lab-Grown Meat. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 184, 123912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xiao, Y.B.; Zhang, W.G. Consumers’ Attitude toward Innovations in Aquaculture Products. Aquaculture 2024, 587, 740834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelken, L.; Weckowska, D.M.; Dreher, C.; Rauh, C. Toward an Innovation Radar for Cultivated Meat. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1390720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, C.; Viu-Roig, M.; Alvarez-Palau, E.J.; Gottardello, D. Foodtech in Motion. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 4182–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobande, O.A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Ogbeifun, L. Repositioning green policy and green innovations for energy transition and net zero target: New evidence and policy actions. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Jiang, Y.; Song, J.; Sun, H.; Sha, Y. The impact of digital inclusive finance on alternate irrigation technology innovation: From the perspective of the’catfish effect’in financial markets. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 312, 109423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Sikka, A.; Dirwai, T.L.; Mabhaudhi, T. Research and Innovation in Agricultural Water Management. Irrig. Drain. 2023, 72, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasso, M.; Blasi, E.; Pezzoli, F.; Cicatiello, C. Co-Innovation Strategies to Prevent Food Loss. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 467, 142984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.J.; Liu, Y.S.; Li, R.T.; Li, Y.R.; Wang, J.Y. TIC-driven sustainable land use mode in the Loess Plateau: A case study of gully land consolidation project in Yan’an City, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 140, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Fan, X.W.; Bai, Z.H.; Ma, L.; Wang, C.; Havlik, P.; Cui, Z.L.; Balkovic, J.; Herrero, M.; Shi, Z.; et al. Holistic food system innovation strategies can close up to 80% of China’s domestic protein gaps while reducing global environmental impacts. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takyi, K.N.; Gavurova, B.; Mikeska, M. Assessing the moderating role of technological innovation on food security in poverty reduction within the Visegrad region. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1545–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Acronym | Definition/Measurement | Unit | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Prices, Food Indices (2015 = 100) | CPFI | Index of consumer prices for food products (base year = 2015) | Index (2015 = 100) | FAOSTAT/World Bank [60] |

| Food Price Inflation | FPI | Annual percentage change in food consumer prices | % | FAOSTAT/WDI [61] |

| Food Price Volatility | FPV | Year-to-year variability in food prices, calculated as the standard deviation of monthly changes | Index/% | FAOSTAT/FAO Food Security Indicators [62] |

| Food Supply Variability | FSV | Variability in the per capita food supply measured in kilocalories per day | kcal/capita/day | FAOSTAT—Food Security Indicators [63] |

| Technological Progress (proxied by Global Innovation Index) | TECHP | Composite measure of a country’s technological development and innovation performance, derived from the Global Innovation Index (GII, WIPO–INSEAD–Cornell) | Score (0–100) | Global Innovation Index Database (WIPO, INSEAD, Cornell University) [64] |

| Trade Openness | TO | Sum of exports and imports of goods and services as a share of GDP | % of GDP | World Bank—WDI [65] |

| GDP per Capita Growth | GDP | Annual percentage growth rate of GDP per capita based on constant local currency | % | World Bank—WDI [66] |

| Population | POP | Total population (log-transformed in models) | Individuals (log) | World Bank—WDI [67] |

| CPFI | FPI | FPV | FSV | TECHP | TO | GDP | POP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 108.6254 | 3.5578 | 0.7905 | 36.2991 | 48.3685 | 131.7268 | 1.9817 | 16,484,585 |

| Median | 102.7000 | 2.1000 | 0.7647 | 30.0000 | 47.8500 | 123.9713 | 1.7949 | 8,797,566 |

| Maximum | 195.2000 | 47.8000 | 1.9091 | 158.0000 | 64.8000 | 412.1772 | 23.4436 | 83,901,923 |

| Minimum | 90.6000 | −6.2000 | 0.2569 | 3.0000 | 34.1000 | 53.9394 | −11.3931 | 416,268.0 |

| Std. Dev. | 16.2784 | 5.8299 | 0.2142 | 24.0721 | 7.5804 | 64.2572 | 3.7807 | 21,745,372 |

| Skewness | 2.2752 | 3.2941 | 0.7201 | 1.9008 | 0.2097 | 1.7252 | 0.2472 | 1.8033 |

| Kurtosis | 8.7756 | 18.0154 | 4.7250 | 8.3512 | 2.0576 | 7.1788 | 6.7854 | 5.0430 |

| Jarque–Bera | 790.7030 | 3932.190 | 73.8622 | 630.1770 | 15.5606 | 429.5263 | 213.1419 | 251.2867 |

| Probability | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Sum | 38,127.50 | 1248.800 | 277.4968 | 12,741.00 | 16,977.35 | 46,236.09 | 695.6091 | 5.79 × 109 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 92,745.64 | 11,895.90 | 16.0674 | 202,813.6 | 20,112.30 | 1,445,148. | 5003.047 | 1.66 × 1017 |

| Observations | 351 | 351 | 351 | 351 | 351 | 351 | 351 | 351 |

| LLC | IPS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Statistic | Prob. | Statistic | Prob. |

| CPFI | −7.8401 | 0.0000 | −2.5292 | 0.0057 |

| FPI | −12.4400 | 0.0000 | −10.6223 | 0.0000 |

| FPV | −10.1874 | 0.0000 | −10.7970 | 0.0000 |

| FSV | −12.2353 | 0.0000 | −5.7293 | 0.0000 |

| TECHP | −7.2970 | 0.0000 | −9.0815 | 0.0000 |

| TO | −22.4757 | 0.0000 | −16.1017 | 0.0000 |

| GDP | −17.5131 | 0.0000 | −12.7217 | 0.0000 |

| POP | −2.0673 | 0.0193 | −1.8147 | 0.0348 |

| Correlation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Statistic | ||||||||

| Probability | CPFI | FPI | FPV | FSV | TECHP | TO | GDP | lnPOP |

| CPFI | 1.0000 | |||||||

| - | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||

| FPI | 0.6552 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| 16.2058 | - | |||||||

| 0.0000 | - | |||||||

| FPV | −0.1479 | −0.3334 | 1.0000 | |||||

| −2.7950 | −6.6083 | - | ||||||

| 0.0055 | 0.0000 | - | ||||||

| FSV | −0.1196 | −0.0876 | 0.0015 | 1.0000 | ||||

| −2.2515 | −1.6428 | 0.0294 | - | |||||

| 0.0250 | 0.1013 | 0.9765 | - | |||||

| TECHP | −0.2155 | −0.1945 | 0.0141 | −0.2112 | 1.0000 | |||

| −4.1239 | −3.7043 | 0.2652 | −4.0369 | - | ||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.7909 | 0.0001 | - | ||||

| TO | 0.0958 | 0.1011 | −0.0264 | 0.0290 | 0.1163 | 1.0000 | ||

| 1.7980 | 1.8999 | −0.4941 | 0.5435 | 2.1883 | - | |||

| 0.0730 | 0.0583 | 0.6215 | 0.5871 | 0.0293 | - | |||

| GDP | 0.0004 | 0.1138 | −0.0528 | −0.0059 | −0.1309 | 0.1125 | 1.0000 | |

| 0.0079 | 2.1399 | −0.9882 | −0.1115 | −2.4681 | 2.1159 | - | ||

| 0.9937 | 0.0330 | 0.3237 | 0.9112 | 0.0141 | 0.0351 | - | ||

| lnPOP | −0.0085 | −0.0193 | 0.0180 | −0.1538 | 0.1178 | −0.4939 | −0.1071 | 1.0000 |

| −0.1601 | −0.3615 | 0.3372 | −2.9088 | 2.2170 | −10.6130 | −2.0140 | - | |

| 0.8729 | 0.7179 | 0.7361 | 0.0039 | 0.0273 | 0.0000 | 0.0448 | - | |

| CPFI | FPI | FPV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Prob. | Coefficient | Prob. | Coefficient | Prob. | Coefficient | Prob. | |

| TECHP | −0.9182 | 0.0001 | −0.1749 | 0.0436 | 0.0030 | 0.6410 | 0.0622 | 0.9283 |

| TO | −0.1748 | 0.0001 | 0.0276 | 0.0965 | −0.0005 | 0.6823 | −0.2160 | 0.0971 |

| GDP | −0.4613 | 0.0053 | −0.1085 | 0.0823 | 0.0013 | 0.7695 | −0.7043 | 0.1337 |

| LNPOP | −54.1438 | 0.0000 | −22.7525 | 0.0000 | 0.1772 | 0.6336 | 164.8150 | 0.0000 |

| C | 1036.2350 | 0.0000 | 368.4751 | 0.0000 | −2.0902 | 0.7200 | −2543.488 | 0.0001 |

| R-squared | 0.8849 | 0.8067 | 0.2441 | 0.4240 | ||||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.8700 | 0.7817 | 0.1465 | 0.3455 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doran, N.M. Boosting Food System Stability Through Technological Progress in Price and Supply Dynamics. Foods 2025, 14, 3910. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223910

Doran NM. Boosting Food System Stability Through Technological Progress in Price and Supply Dynamics. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3910. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223910

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoran, Nicoleta Mihaela. 2025. "Boosting Food System Stability Through Technological Progress in Price and Supply Dynamics" Foods 14, no. 22: 3910. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223910

APA StyleDoran, N. M. (2025). Boosting Food System Stability Through Technological Progress in Price and Supply Dynamics. Foods, 14(22), 3910. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223910