Abstract

The goal of this exploratory study was to analyze the influence of culture on African women’s diet considering their role as primary caregivers. The analysis differentiated between Moroccan and Senegalese women and identified the key elements that influence their dietary habits and their health. Using a qualitative methodology, we performed a triangulation of data based on a literature review and a panel of experts, all of which served as the basis for the interview script to conduct 14 semi-structured interviews (n = 7 Moroccan and n = 7 Senegalese). This study reflects the substantial relationship between dietary habits, cultural identity, and health that healthcare providers need to acknowledge. It is important for healthcare practitioners to be culturally competent in order to provide holistic and individualized care.

1. Introduction

Nourishment is a basic need for human evolution, which has undergone important transformations. Food has gone from being understood as a means of subsistence to a matter influenced by biological, geographic, psychological, and cultural factors that determine how we behave, how we live, and how we relate to others [1]. Studies focusing on this topic have prioritized the positivist paradigm, emphasizing the nutrient itself rather than specific eating behaviors; this reflects the “prominence of caloric values over symbolic values” [2] without taking into account the relationship between cultural practices and eating habits, which are closely related to overall health among the population, making their study and examination crucial [3]. The scientific community has found that the complexity of nutritional issues goes beyond aspects that are merely physical, physiological, and quantifiable. This highlights the key role of social and cultural issues, which, after all, are the determining factors in the construction of eating-related ideologies and representations of what is and what is not healthy food [4,5]. Diet is not solely a medical prescription with a healing purpose; the main feature of eating behaviors involves the social practices that surround them. These practices are embedded in the culture, customs, traditions, policies, norms, and values of each social group, which are influenced by geography, time, economic models, and policies, particularly health policies [6].

It is noteworthy that the influence of culture is rooted in historical traditions that tend to legitimize certain eating and drinking social practices. For instance, in France, wine has long been associated with healthy habits [7]. The epistemic function enables a conceptual framework for sensemaking, while the affiliation function can convey a cultural baggage that consolidates the social representations of food in a given culture, binding tradition and eating/drinking habits while connecting food and cultural identity [4,5,6].

In this context, it is important to recognize the direct impact of eating habits on health, whereby the concept of health must be added to the diet–cultural identity pairing, creating a triad that should not be overlooked by healthcare providers. Another study describes how cultural identity can modify people’s interpretation of nutritional information and, consequently, their food consumption habits [8]. Health-conscious patients or consumers capable of taking action for their life goals and preferences will be consistent with food and health as long as their culture integrates them into their habits [9]. Therefore, personal nutrition researchers and providers should devise strategies to inform and discuss with patients or consumers the implications of their life goals and health preferences.

Although there are many studies that discuss existing relationships between particular foods and certain diseases, this study aims to understand, through the testimonies of the women themselves, their perspectives and perceptions regarding the factors that condition health in relation to food as well as the elements that influence it, highlighting the importance of culture in decision making.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

A qualitative exploratory study with a phenomenological approach was conducted by means of a content analysis as described by Taylor and Bodgan [10]. This research adheres to the COREQ guidelines [11].

In order to address the proposed research objectives, a data triangulation [12] was carried out, comprising an initial bibliographic search that, together with the panel of experts, served as the basis for the interview script. These resulting categories were validated using a “modified Delphi” methodology, where, based on the opinions of the experts, a consensus was reached, which made it possible to obtain the interview guide to be used with the participants [13]. The sampling strategy for the expert panel was based on theoretical sampling with a total of 7 professional experts from different disciplines (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics addressed in the expert panel.

To conclude the methodological triad, we began with semi-structured interviews targeted at two populations. On the one hand, we selected Moroccan women living in Spain or Morocco, and on the other hand, we selected Senegalese women living in Spain or Senegal. Given the difficulties of accessibility to recruit volunteers as informants, a snowball sampling technique was used [14], reaching 7 Moroccan women and 7 Senegalese women, achieving saturation in each of the dimensions [15].

The semi-structured interviews were conducted through open-ended questions, allowing the participants to argue and elaborate their answers, lasting between one and one and a half hours during the months of December 2020 and June 2021. Fieldwork continued until no new data could be extracted in relation to the thematic categories.

The inclusion criteria required female participants to be over 18 years of age, to live or have lived in an area of Morocco or Senegal (depending on their group), to participate voluntarily, and to have read and signed the informed consent form.

For the analysis of the interviews, the model described by Taylor-Bodgan [10] (Table 2) was used.

Table 2.

Analytical process in qualitative research (Taylor-Bogdan).

The research team listened to recordings and read interview transcripts to make an initial cursory interpretation. This provided a general idea that supported a deeper analysis (this involved the identification of relevant recurring themes, the search for similarities and differences between themes to develop codes—dimensions—and, with these, thematic categories). The presence of coinciding codes—dimensions—by different researchers—blind analysis—indicated that the analysis reached the core and revealed the meanings of the phenomenon under study.

In order to ensure validity and reliability, the entire process of coding and discourse analysis was carried out independently by three members of the research team. Discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines [16].

3. Results

Characteristics of the Participants

The present study was conducted with 14 women, namely 7 Moroccan women (MW) and 7 Senegalese women (SM), who were representative in terms of age, geographic area, religion, level of education, and interview language, with some participating women not sharing our mother tongue (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Coding of discourse was carried out using the interview transcripts, and it produced 11 different codes. Data were analyzed via discourse analysis using ATLAS.ti 9 Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany. Considering repetition patterns in expressions in relation to each code, four lines of argumentation emerged. These were evenly distributed within both population groups, suggesting the determining factors influencing the perception of food coincide in both populations.

Through observation, expert interviews, and interviews with women, different categories emerged underlying those initially raised.

Such themes arose after reflection on how the study population thinks and comments on their own health and well-being.

Through their discourses, we learned about these women’s perspectives and perceptions of the factors that condition health in relation to food as well as the elements that influence them; this enabled us to move to the interpretation stage, increasing the level of abstraction.

Their health self-concept is a unique aspect, which is evident in the discourse by participants from both populations. In this context, there are different reflections on the importance of maintaining a healthy diet in order to achieve good health and how nutrition conditions their health (Table 4).

Table 4.

Origin of categories and subcategories by population group.

There are multiple elements that have an impact on eating habits and, consequently, on their health. Among them, the resources and materials are noteworthy as well as their religion, the impact of culture, resource accessibility, and health promotion investment and practices. These factors contribute to the consumption of certain types of food and limit access to others, also affecting the way they are cooked and ingested (Table 4).

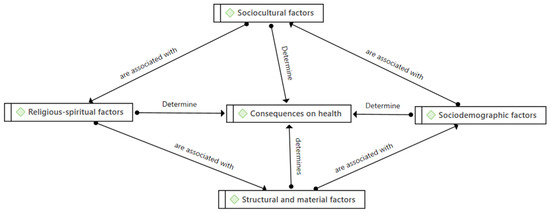

Religion invites activities that promote health, such as healthy eating, hygiene, and prayer, which are very present in both populations. These constitute key aspects in their perception of health (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Health conditioning factors. Source: Prepared by the authors.

The respondents stated that their diet follows patterns dictated by their religion. For example, Muslim women say that their religion prevents them from eating pork or that they prepare certain foods in a particular way. This religion has a symbiotic relationship with culture, and their mutual influence generates some remarkable eating habits (Table 5).

Table 5.

Health self-concept: Senegalese and Moroccan women’s statements.

Culture is expressed through rituals and traditions and becomes yet another element that influences the foods that are eaten and when and why. With participants from both Muslim and Christian countries, we found interesting differences between them, such as, for example, the Feast of the Lamb or Ramadan for Muslims and avoiding meat or fasting on Fridays during Lent for Christians (Table 5).

On the other hand, a common and very frequent diet staple in both populations is tea. Their culture assigns a significance to tea that goes beyond its nutritional or hydration values, adding a cultural and customary value.

Accessibility to food resources conditions the type of food consumed as well as the perception of its value for their health self-concept.

In their discourses, a multifactorial self-concept of health was revealed, which conditions the health promotion initiatives that they develop and assume as communities and as individuals (Table 5).

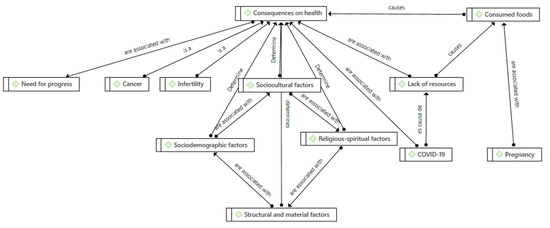

Regarding the elements that generate health differences (Table 6) among the Senegalese and Moroccan populations, two important subcategories were observed: gender and economic resources (Figure 2).

Table 6.

Differences and consequences on health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Senegalese and Moroccan women’s statements.

Figure 2.

Gender-related health consequences and lack of resources. Source: Prepared by the authors.

Gender conditions the distribution, responsibilities, and modes of participation in family and cultural nutrition as well as specific elements of the female condition. Women are the main caregivers responsible for feeding their entire family, while tea and its cultural significance is the responsibility of men.

Pregnancy involves a special process and a stage of life that highlights the importance of taking care of nutrition.

One of the emerging categories found in this study is infertility, associated with current eating habits, which are considered poorer than in the past.

Socioeconomic level is a key element that all the participants, both Moroccans and Senegalese, mentioned as a decisive factor that influences their diet and, ultimately, their health. People with fewer resources buy cheaper and less diverse foods as opposed to those with a higher economic level.

Regarding lifestyle habits and gender, there are two significant findings in relation to sports and physical care; they explain that it is more common to see men engaging in some kind of physical activity than women.

The consequences on the population’s health (Table 6) were reflected in two emerging categories: on the one hand, the concern among members of the Moroccan population for cancer and, on the other, its connection with lifestyle and dietary habits.

The interviewees reflected that food goes beyond fulfilling biological needs but has become a social value and a cultural ritual of solidarity and companionship throughout history. In Senegal, the value they place on eating together as a family is particularly significant and is considered a tradition in itself.

Finally, participants highlighted how the global pandemic of Covid19 (Table 6) conditioned their dietary practices. Due to the subsistence economy, many people were unable to work, so food was also affected, and they began to change eating patterns and consume what was available to them.

4. Discussion

It is important to understand the role of eating behaviors among humans and how they have evolved in order to understand why current eating habits exist and how they influence health.

Our study has shown how people’s eating habits are influenced by factors that are not exclusively biological, such as culture, social class, age, education, health, and even their social environment [17]. Globalization and the scientific and technological revolution have led to the recognition of the complexity of the food process and the need for analysis from a holistic perspective that integrates biological principles, social practices, and the motivations that structure subjects’ eating processes [18].

The results of our study demonstrate that habits do not only satisfy physiological and psychological needs but also respond to cultural needs and gender needs, among other needs. This applies because people tend to show their social status, their economic level (especially if it is high), and their values. However, the meanings attributed to this status are not inherent to food since they depend on the social context in which they are developed. Food thus has both a material and a symbolic meaning. These results are consistent with several authors [19] who assert that distinct social groups have different habits and behaviors, which specifically present the needs of each group, their cultural conditions, their experiences, and their history, among other aspects, thus establishing a particular distinction that can be recognized. These authors also agree with another finding from our research, which refers to the way people feed themselves as a reflection of their social identity and their belonging to a particular social group [19,20,21].

The cultural importance of food and nutrition is centered on the values, meanings, and social beliefs that are present in today’s society.

When choosing food, people are influenced by a series of internal aspects, such as biological and emotional factors, beliefs, and attitudes. There are also social, economic, and physical elements that also influence food choices; these are external factors [22]. Several studies [23,24] establish that there is a statistically significant relationship between eating patterns and the aforementioned variables. In our study, participants’ statements evidence the presence of these variables in dietary decision making, also taking into account gender and religion.

A study conducted at Dalhousie University, Canada [25], examined the meaning of food for Goan women in Toronto and the role of food in creating and maintaining gender-differentiated ethnic identities. The overlaps with our results lie in how the gender role of women in caring for and cooking food had a particular power or “currency” within the family and community, valued for fostering and supporting cultural identity; another study developed in the same country, at the University of Alberta [26], matched the food, culture, and gender triad as part of the ethnic identity within the community, as can be seen in some of our informants’ discourses. In this case, the respondents, the study population of Moroccan women residing in Canada, agreed, concluding that the women shared their struggles to maintain ethnic cuisine as a marker of community affiliation that is related to preservation of health in the community despite the difficulties to access food, whether financial or due to the lack of resources in the country itself.

A study developed at the University of Oviedo, Spain, with the African population [27] supports our main findings along the dimensions of religion, culture, and gender as determinants of health in the food sphere, and it also coincides with the religious prescriptions and eating rituals without taking into account the consequences for health although they affirm that health begins with adequate eating.

5. Conclusions

African women’s understanding of food-related health is influenced by culture, gender, and the identity of the community where they reside.

Religion, both in North African and Sub-Saharan African women (both practice Islam although in Senegal, it is associated with Islam-Animism), has a great influence on the definition of food discourse, and it is remarkable how Islam defines what can be eaten or not, what is allowed by the Muslim community, and what is associated with different religious rituals. There is a radical ban on any food derived from pork, which is a ban derived from religious prescriptions.

The preservation of their own cultural dietary patterns is especially favored by the family, where women play a fundamental role as agents of health in their own community.

African women’s conception of health in the study is conditioned by dietary prescriptions linked to their culture. These are also associated with the deprivation of banned substances such as alcohol and tobacco although most of the women interviewed linked this not only to culture but also to economic resources, which are fundamental for good health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.C.-T. and E.B.G.-N.; methodology, E.B.G.-N.; software, M.J.C.-T. and M.A.-H.; validation, E.B.G.-N. and M.A.-H.; formal analysis, M.J.C.-T.; investigation, E.B.G.-N., M.J.C.-T. and M.A.-H.; resources, E.B.G.-N., M.J.C.-T. and M.A.-H.; data curation, E.B.G.-N., M.J.C.-T. and M.A.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.G.-N. and M.J.C.-T.; writing—review and editing, E.B.G.-N., M.J.C.-T. and M.A.-H.; visualization, E.B.G.-N.; supervision, E.B.G.-N.; project administration, E.B.G.-N., M.J.C.-T. and M.A.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants who took part in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arroyo, P. Diet in man evolution: Relation with the risk of chronic and degenerative diseases. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. Mex. 2008, 65, 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, B.; Conde, D.; Muñoz, B.; García, J.; Fonseca, C.; Mariano, L. Cultural approaches of feeding in elderly rural people. First-rate issues and evidences. Index Enferm. 2019, 28, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrick, G.; Torelli, C. It’s not just numbers: Cultural identities influence how nutrition information influences the valuation of foods. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, K.; Coff, C.; Jönsson, H.; Nordenfelt, L.; Görman, U. Food and health: Individual, cultural, or scientific matters? Genes Nutr. 2013, 8, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez, J.; Cañez, G. La cocina tradicional regional como un elemento de identidad y desarrollo local: El caso de San Pedro El Saucito, Sonora, México. Estud. Soc. 2019, 17, 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Arnaiz, M. Alimentación y cultura en España: Una aproximación desde la antropología social. Physis Rev. Saúde Coletiva 2010, 20, 357–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoz-Campos, M.A.; Gracia-Pérez, F.J.; Hervás-Morcillo, J.; Camañes-Salvador, A. Sin vino… ¿estás seguro, corazón? De la trilogía mediterránea a la paradoja francesa. Enfermería Cardiol. 2019, 9, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, J.; Arnaiz, M.G. Alimentación y Cultura: Perspectivas Antropológicas; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; Volume 392. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, E.J.; Wiik, F.B. Antropología, salud y enfermedad: Una introducción al concepto de cultura aplicado a las ciencias de la salud. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2010, 18, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introducción a los Métodos Cualitativos de Investigación; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1987; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Arena, P.; Craig, J. Criterios consolidados para informar sobre investigación cualitativa (COREQ): Una lista de verificación de 32 ítems para entrevistas y grupos focales. Inter. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J.A. Diseño de Investigación Cualitativa; Editorial Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; Volume 241006. [Google Scholar]

- García Valdés, M.; Suárez Marín, M. El método Delphi para la consulta a expertos en la investigación científica. Rev. Cuba. De Salud Pública 2013, 39, 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, C.; Castro, A. El muestreo en la investigación cualitativa. NURE Investig. Rev. Cient. Enferm. 2007, 27, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. ¿Ya estamos allí? Saturación de datos en investigación cualitativa. Interciencia 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, J.L. Declaración de Helsinki: Principios éticos para la investigación médica sobre sujetos humanos. Acta Bioeth. 2000, 6, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes dos Santos, C. Somos lo que comemos: Identidad cultural y hábitos alimenticios. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2007, 16, 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker-Sagastume, R.; Hunot-Alexander, C.; Moreno-Gaspar, L.E.; López-Torres, P.; González-Gutiérrez, M. Epistemologías y paradigmas de los campos disciplinares de la nutrición y los alimentos en la formación de nutriólogos. Análisis y propuestas para el desarrollo curricular. Rev. Educ. Desarro. 2012, 21, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.; Campbell, H.; Murcott, A. A brief pre-history of food waste and the social sciences. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 60, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugh, C.; Murcott, A.; MacKenzie, A. Kosher in New York City, halal in Aquitaine: Challenging the relationship between neoliberalism and food auditing. Agric. Hum. Values 2011, 28, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcott, A. The cultural significance of food and eating. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1982, 41, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresson, J.L.; Flynn, A.; Heinonen, M.; Hulshof, K.; Korhonen, H.; Lagiou, P.; Løvik, M.; Marchelli, R.; Martin, A.; Moseley, B.; et al. The setting of nutrient profiles for foods bearing nutrition and health claims pursuant to Article 4 of the Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006: Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. EFSA J. 2008, 6, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L. Sociology of food consumption. Handb. Food Res. 2013, 91, 324–337. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.; Germov, J. A Sociology of Food & Nutrition: The Social Appetite; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- D’Sylva, A.; Beagan, B.L. Food is culture, but it’s also power: The role of food in ethnic and gender identity construction among Goan Canadian women. J. Gend. Stud. 2011, 20, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianatos, H.; Raine, K. Consuming food and constructing identities among Arabic and South Asian immigrant women. Food Cult. Soc. 2008, 11, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, T.S.; Van den Broek, H.P. Inmigración, alimentación y salud: La percepción de la dieta saludable entre los inmigrantes musulmanes en España. In Actas del VIII Congreso sobre Migraciones Internacionales en España: Granada, 16–18 de Septiembre de 2015; Instituto de Migraciones: Granada, Spain, 2015; p. 279. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).