Abstract

Granny Josie’s Notebooks are salvaged notebooks written in 1946–1947 during a rural domestic science course for girls. This study aims to extract historically valuable information on the culinary heritage of post-war Poland and the housekeeping role attributed to women, with a specific focus on assessing the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) in corpus analysis. The research began with an inquiry into the historical context of the notebooks. Three notebooks were digitised and stored in data repositories, then converted into editable vector text. The corpus was analysed with AI, and the results were compared with a text profile prepared by qualified linguists. According to the AI, the texts’ characteristic features are descriptions of nearly ritual food preparation, serving, and table setting. Women appear as central figures in post-war Polish housekeeping, acting as guardians of the hearth and planners and preparers of meals. However, AI’s interpretations were often overly idealised, with embellished descriptions that did not fully reflect the actual text. The digitisation and analysis of Granny Josie’s Notebooks provided new information about the culinary heritage of post-war Poland and preserved these materials from oblivion, while offering insights into the potential application of LLMs in corpus analysis.

1. Introduction

I believe placement at the Rural Domestic Science School for Girls in Szynwałd was the best dowry the father could give his adolescent daughters at that time.Alicja Wiązowska from Tarnów, daughter of Granny Josie’s

Cultural identity emerges from constant transformations and multifaceted interactions of elements specific to the place, time, and external cultural impacts. It comprises multiple components, including language, values and beliefs, traditions and customs, natural environment, lifestyle and behavioural patterns, regional products, plant and animal species, processing methods, and food recipes (Partarakis et al., 2021). Culinary heritage is a collection of traditions, recipes, and customs for preparing, serving, and eating food. It is also a type of intangible culture, combining food with history, geography, religion, customs, and social norms (Holliday, 2010). Culinary heritage is embodied in ingredients and products of plant origin based on old plant varieties, traditional animal breeds, and regional recipes. Other components of culinary heritage are preparation techniques, cooking rituals, and eating and drinking styles. The third factor group is people, their behaviour, places and ways they obtain and cook products, and specific traditional production equipment (Lee, 2023). Many of them are forgotten as technology advances and socioeconomic and cultural changes approach. Time, globalisation, cultural homogenisation, commercialisation and mass production, lifestyle and consumer preference changes, and shifting values and social attitudes may cause folklore and original designs of traditional and local food products to vanish gradually (Fontefrancesco & Zocchi, 2020). Therefore, to save them from oblivion, the unique customs, recipes, and foods made with traditional methods, along with the lifestyle and housekeeping culture, need to be preserved (Knapik & Król, 2023).

One-of-a-kind recipes or accounts of local customs were often recorded by hand by local people, aficionados, community leaders, or food manufacturers. These particularly fragile artefacts provide insight into the cultural heritage of past generations (Wharton, 2010). Therefore, those not yet lost should be protected, preserved, digitised, and made available to the public. The story of Granny Josie’s Notebooks is the perfect example of this approach.

Granny Josie’s Notebooks are school notebooks salvaged by Alicja Wiązowska from Tarnów, Poland. They contain notes her mother made in 1946–1947 during a domestic science course for girls from rural settings expected to become farmwives (Król, 2025b). The notebooks record what young women were taught at the time as knowledge and skills considered necessary for housekeeping. Three hand-written notebooks were preserved: (1) the first notebook of 159 pages, (2) the second notebook of 80 pages, and (3) the third notebook of 166 pages. The study aims to extract historically valuable information on the culinary heritage of post-war Poland and the housekeeping role attributed to women. The tangible contribution of the article is (1) preservation of culinary heritage artefacts: three notebooks written right after the Second World War by Józefa Kmieć née Kapusta; (2) results of an in-depth AI analysis of the digitised content of the notebooks juxtaposed with independent expert analysis; (3) Granny Josie’s Notebooks made available as e-books on a website and in data repositories.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides background on Granny Josie, followed by literature research on the application of Large Language Models (LLMs) in research, including corpus analysis. Section 3 presents the methodology, focusing on the method of corpus building and analysis. ‘Formal’ and ‘informal’ results are presented in Section 4. Section 5 contains a discussion of the results and observations of the linguists who built the corpus. A summary and practical implications provide a closure.

2. Background

After the Second World War, Poland faced the challenge of restoring its infrastructure and economy, along with the entire education and social values systems, particularly in rural areas. The reinstated education system prioritised educating women in housekeeping, food preparation, hygiene, and family management. Schools that taught household economy and management played an important role in post-war Poland, disseminating practical skills and shaping citizens, instilling a sense of social responsibility and work ethic. Their curricula were intended to support the restoration of everyday life and promote household autarky, health, and healthy eating. These institutions were part of a larger social policy scheme in which the state used the education of women as a means to modernise rural areas and reinforce family values (Świgost-Kapocsi, 2021). Women were taught to use local products, plan meals, and ensure hygienic eating conditions amid the post-war resource shortages and supply issues. The classes aimed to guide the girls’ upbringing by teaching them housekeeping skills and showing them how to take responsibility for their families’ health (Mach, 2020).

2.1. Who Was Granny Josie?

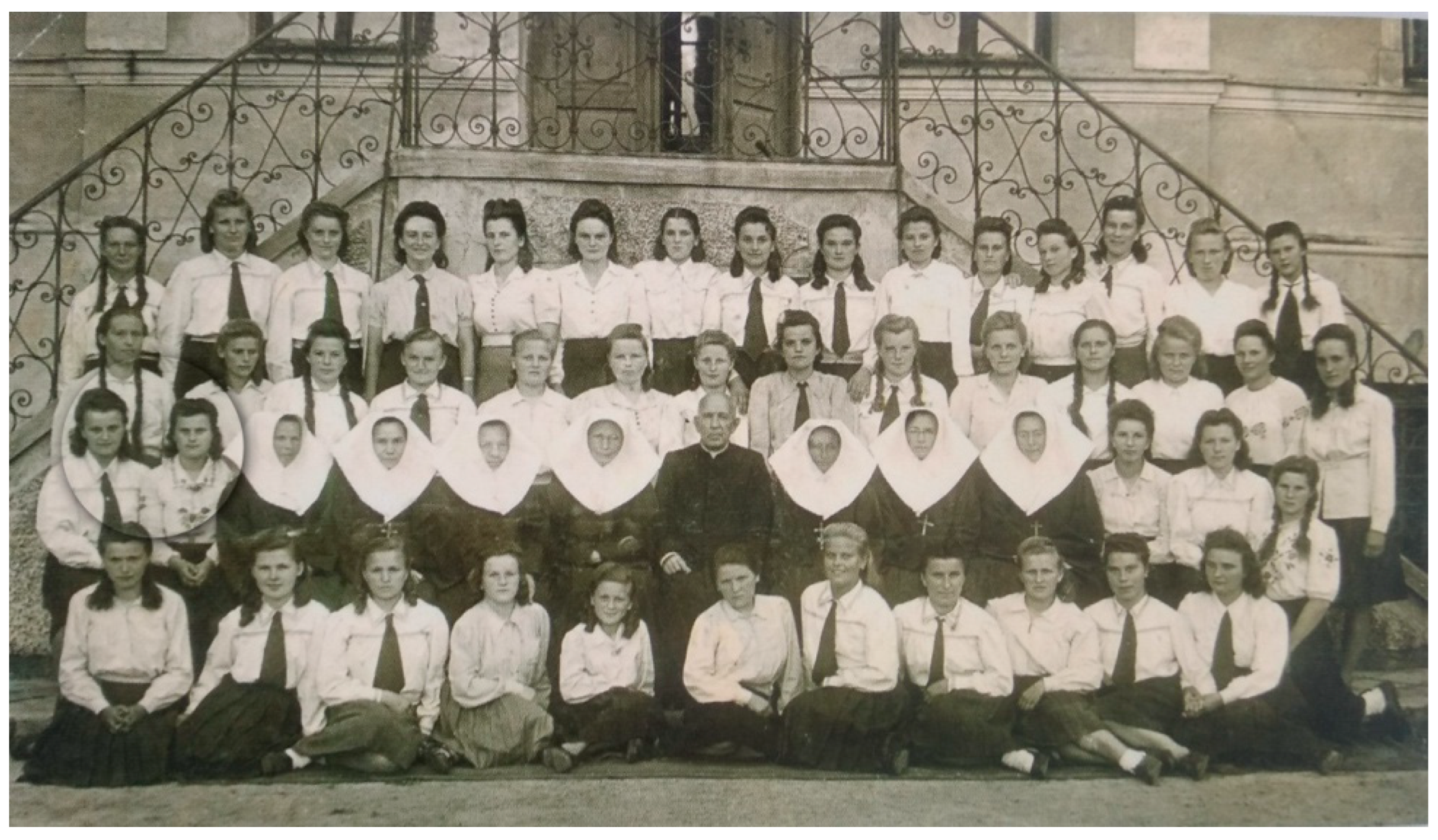

Granny Josie was Józefa Kmieć née Kapusta (1925–2008). The notebooks contain her notes from courses delivered by nuns at the Rural Domestic Science School for Girls in Szynwałd near Tarnów, Małopolskie Voivodeship, Poland (Szkoła Gospodyń Wiejskich w Szynwałdzie). The primary purpose of the school was to provide girls with a comprehensive education and prepare them for housekeeping duties (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graduates of the school for young women run by nuns in Szynwałd near Tarnów. Granny Josie is sitting in the second row from the bottom, the first one from the left. Next to her is her sister, Frania. Source: family archives of Granny Josie’s daughter Alicja Wiązowska from Tarnów.

The Rural Domestic Science School for Girls in Szynwałd was established by Aleksander Siemieński, supported by Deputy to the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria Wincenty Witos and President of Farmer Associations in Lviv Bronisław Dulęba (Król, 2025b). The construction of the school building commenced in 1907. It was opened on 1 October 1909. The first nun teachers were trained at the domestic science school in Katerinky, Czechia. After certification, they started teaching in Szynwałd (Mącior et al., 2017). There were 21 pupils at the school in the first year. Then, the number grew to 30 to 50 a year. They were aged 16 to 22 and paid a fee to cover some costs of running the school.

The pupils were mostly from the countryside, but the school also accepted daughters of landowners, labourers, and officials. All candidates had to have an elementary school background. In 1912, the Farmer Association Society started sponsoring the school (Król, 2025b).

The principal purpose of the Rural Domestic Science School for Girls in Szynwałd was to provide girls with a comprehensive education and prepare them for housekeeping. At first, the school year was ten months, from 1 October to 30 July. It taught general subjects. Practical training was conducted in smaller groups: cooking, laundry and ironing, keeping the house and its surroundings tidy, poultry, rabbit, pig, and cattle husbandry, dairy, sewing, garden work, vegetable cultivation, grafting fruit trees, and floriculture (Mącior et al., 2017).

In 1921, the school introduced the curriculum of the agricultural elementary school for girls devised by the Polish Ministry of Agriculture and State Assets. It covered ethics and religion lectures, the Polish language, the history of Poland, the study of Poland, calculations, geography, animate natural environment, inanimate natural environment, husbandry, veterinary science, dairy production, beekeeping, fruit farming, the study of agriculture, hygiene and medical aid, law lectures, singing and drawing. Later, the curriculum also included dressmaking, washing, household, and raising children. The school was renamed in 1938 to Private Rural Domestic Science School for Girls of Sisters of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Szynwałd (Prywatna Żeńska Szkoła Przysposobienia Gospodyń Wiejskich Zgromadzenia Sióstr Służebniczek NMP w Szynwałdzie). During the Second World War, teaching was difficult and often interrupted. The occupants destroyed the buildings and stole the equipment. The school was closed down in 1949 (Mącior et al., 2017).

After completing her education at the Rural Domestic Science School for Girls in Szynwałd, Józefa Kmieć returned home to Łysa Góra (Brzeski District, Małopolskie Voivodeship). She immediately put her education into practice. She helped her father cut up the meat of slaughtered animals, work of which she spoke often. After getting married in 1948, she moved with her husband to Oliwa in Gdańsk, then to Karpacz and Brzesko. They finally settled in Tarnów. Granny Josie’s Notebooks, her notes from her time at the Rural Domestic Science School for Girls in Szynwałd, somehow survived numerous removals and turbulences. They were sources of cooking recipes and housekeeping guidelines, but also a carrier of memories of her youth.

2.2. Related Work

Large Language Models (LLMs) are deep-learning models with a huge number of parameters trained in an unsupervised way on large volumes of text (Birhane et al., 2023, p. 277). Large Language Models can generate human-like text, answer questions, and complete other language-related tasks with high accuracy (Kasneci et al., 2023). Users can mistake them for humans, especially when they are used as assistants or dialogue agents. The user may then be under the impression that they interact with ‘a real interlocutor’, whereas in fact, an LLM is a disembodied neural network that has been trained on a large corpus of human-generated text with the objective of predicting the next word (token) given a sequence of words (tokens) as context (Shanahan et al., 2023, p. 493).

The literature analysis revealed that LLMs are increasingly employed to streamline processes and support various efforts towards preserving and promoting cultural heritage. Zhang et al. (2024) developed Architectural GPT (ArchGPT) to aid architectural restoration jobs. ArchGPT uses an LLM to plan conservation activities. Trichopoulos et al. (2023) analysed the potential of using OpenAI’s ChatGPT as a digital agent who can be trained to act as a museum guide. Colucci Cante et al. (2024) conducted a similar study. They noted that not only did LLMs and chatbots convey content in a more accessible and engaging way, but they also supported personalisation and interaction. Researchers believe these tools encourage cohesive and interesting narratives and accurately represent the historical context. Results by Vasic et al. (2024) demonstrated that LLMs make virtual 3D trips a more personalised and interactive event for art gallery visitors. Large Language Model-based systems can respond dynamically to questions from visitors and display relevant content. This can lead to an automated and yet personalised museum experience. Still, although AI technologies come with a huge potential, the challenges are equal in impact, including factual accuracy and cultural sensitivity.

Uchida (2024) demonstrated that LLMs can be useful for multi-perspective corpus linguistic research, including the creation of word frequency lists, extraction of collocations, identification of expressions fitting certain grammatical patterns, and genre identification experiments. He concluded that such tools as ChatGPT can be useful for textual analysis, but they stumble on more complex tasks. Miah et al. (2024) employed LLMs to investigate sentiment. Their principal assumption was that sentiment analysis is an essential task in natural language processing that involves identifying a text’s polarity. Nitu and Dascalu (2024) demonstrated that LLMs are useful for pinpointing differences between texts created by humans and generated by AI by revealing lexical diversity and textual complexity. Orenstrakh et al. (2024) tested the performance of applications designed to identify AI-generated texts. They turned out to offer limited effectiveness. Fonteyn et al. (2024) reported that although LLMs are useful in linguistic research, their processes and methods of understanding such ideas as metaphors or semantic roles should be further investigated to improve scholars’ confidence in the tools.

Nejjar et al. (2025) pointed out that the application of AI tools in everyday research work is widely disputed. Large Language Models have great potential for elevating research, but there are certain challenges involved. For instance, different AI tools offer similar research results for simple tasks, but more creative and context-dependent prompts lead to significant variations across the answers. Moreover, issues such as AI hallucinations or misleading or outright incorrect results still need to be addressed. The problem of hallucinations was also noted by Rachabatuni et al. (2024). The researchers demonstrated that although Multimodal Large Language Models offer good results of image analysis and text generation, their performance regarding questions related to visual context is mediocre. Currently, LLMs tend to provide false information. This limits their usefulness in domains such as cultural heritage, where fact-driven and methodical interpretation of texts and images is necessary. Therefore, the literature review has demonstrated that AI performance in cultural heritage research depends on the context, including the object and scope of the study. Therefore, LLMs need to be further investigated regarding their performance in studying digital or digitised artefacts, including texts and images.

Previous studies have shown that Large Language Models have been applied to a wide range of research and creative tasks, including corpus construction and linguistic annotation, semantic and sentiment analysis, authorship attribution and stylometric analysis, transcription and translation of historical texts, narrative elaboration of cultural heritage including the simulation of museum guides, and generation of interpretative summaries and metadata for archival materials. These applications demonstrate that LLMs can function not only as analytical instruments but also as narrative and interpretative agents in digital humanities research. Their effectiveness, however, largely depends on prompt design and contextual conditions, which justifies further research into their reliability and interpretability in cultural heritage projects.

3. Materials and Methods

The analysed source material consists of three handwritten notebooks from 1946 to 1947. Each contains 80 to 160 pages, similar in size to A5 (about 15 × 21 cm), with handwritten text of variable compaction and meticulousness, demonstrating that it was compiled in various circumstances and at diverse paces. The notebooks show signs of intensive use, such as dog-ears, stains, and marginal annotations, indicating their function as practical learning aids and how-to notes for everyday household chores and kitchen activities. The thin cardboard covers reflect the post-war shortage of raw materials and frugal approach to school aids.

When digitised, Granny Josie’s Notebooks became a database of a kind. The digitised notebooks were subjected to a multidimensional AI analysis. The analysis followed a query where facts reported by Alicja Wiązowska from Tarnów, Granny Josie’s daughter, were recorded. The aim was to put the notebooks in a spatio-temporal historical context. Next, the three volumes were digitised for storage in a digital repository. The texts were digitised by scanning the pages into PDF files (Digitised <scanned> Granny Josie’s Notebooks were uploaded to the repository of the Library of the University of Agriculture in Kraków at http://ruralstrateg.pl/zeszyty-babci-jozi-w-bibliotece-cyfrowej-urk/; accessed: 12 August 2025). At the third stage, the digitised copies were converted from rasters (PDFs) into editable vector text and published as e-books (Granny Josie’s Notebooks as e-books: http://ruralstrateg.pl/e-book-zeszyty-babci-jozi/; accessed: 12 August 2025).

The text was transcribed by two certified linguists. They used SpeechTexter (2025) voice-to-text software. SpeechTexter is a web application that automatically converts speech (sounds) into editable vector text. The application streamlines the conversion of spoken texts, such as notes read out loud, into documents or books. The outcome was a corpus, a database (see Supplementary Materials). According to MS Word statistics, the corpus is 91 pages long (Times New Roman, 11 points, spacing 1.0) or 44,788 words in Polish.

Research Design and Tools

The corpus analysis (AI-powered evaluation) was a semantic investigation using ChatGPT by OpenAI (GPT-4o). Two types of prompts were employed under the research design: (1) formal prompts that followed the Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) and Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) methods and (2) informal prompts for a general keyword analysis and semantic evaluation of the text. Details of the prompts are provided in the Results Section. This step was followed by additional analyses for a more in-depth understanding of the structure and cultural context of the digitised content. These auxiliary analyses included (1) stylometry, an analysis of the stylistic features based on word frequency, sentence length, and grammatical complexity and (2) pragmatic and sociolinguistic analysis to reveal the social context and determine the practical or perhaps educational nature of the text. The research has been designed as a qualitative case study aimed at demonstrating a method rather than making statistical generalisations. Therefore, the interpretation perspective aligns with digital humanities methods. The analysis focused on the qualitative interpretation of the model’s output rather than a replicable computational analysis. It was impossible to access the internal model parameters, complete intermediary results, and error metrics because ChatGPT is a closed-source environment. The outputs were interpreted and processed through a topical synthesis of conclusions. Therefore, the results should be considered the effect of a qualitative, exploratory corpus analysis using language models rather than the results of statistical calculations. The models aided text interpretation and the recognition of linguistic patterns and structures. The digital humanities approach, in a way, directed the effort toward procedural transparency and interpretative cohesion instead of the replicability of the calculations. As a result, the objective was not statistical replicability. The focus was on identifying the relationship between content, language, and cultural context in line with digital humanities. This approach is sensitive to semantic and contextual nuances, which often elude quantification.

Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) is one of the oldest semantic models. It analyses the co-occurrence of words in large sets of texts (corpora). It presents words and documents as vectors in a reduced space to reveal latent semantic relationships between words (Landauer et al., 1998). Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) is a Natural Language Processing and information research method. It aims at assessing the meaning of a specific word in the context of the entire corpus (Havrlant & Kreinovich, 2017).

Validation of the AI’s output was critical. The characteristics provided by ChatGPT were juxtaposed with an independent expert analysis by the linguists involved in the digitisation process. The evaluation involved a qualitative verification of the model’s interpretations. Experts analysed the accuracy of the semantic reading, alignment of the conclusions with the source, and linguistic consistency with the historical context. The goal was to define the boundaries of the model’s interpretative performance in historical text analysis, rather than to confirm that all its answers were correct.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Informal Prompts

Prompt: Characterise the provided text, please. Write 300-word conclusions from a semantic analysis of the text. Focus on the most frequent keywords and identify five main topics in the text. Thank you.

Synthesised (summarised) AI’s responses: According to ChatGPT, the corpus is a collection of cooking recipes with instructions on food preparation and guidelines regarding serving aesthetics. Frequently repeated words are primary ingredients, such as ‘flour’, ‘sugar’, ‘butter’, and ‘potatoes’ and techniques: ‘roasting’, ‘baking’, ‘frying’, and ‘boiling’. The semantic analysis identified five main topics in the texts related to various aspects of cooking and serving food.

- (1)

- Baking and desserts: a significant portion of the corpus is recipes for baked products and desserts with such frequent ingredients as flour, sugar, and butter and instructions on how to knead and bake cakes.

- (2)

- Main courses: potato main courses are another common topic in the corpus. Words like ‘potatoes’, ‘butter’, and ‘onion’ occur frequently in recipes for potato patties, croquettes, and gratins. The corpus contains the following frequent keywords: ‘boiling’, ‘mashing’, ‘forming’, and ‘frying’. This demonstrates that potatoes are an important part of the traditional Polish cuisine.

- (3)

- Soups and sauces/gravies: the text contains numerous recipes for soups and sauces/gravies, which is evident from such frequent words as ‘water’, ‘vegetables’, ‘onion’, and ‘cream’. The corpus includes descriptions of various soups, including traditional cabbage soup and borsch, and sauce/gravy recipes as additions to the main courses.

- (4)

- Cabbage dishes: cabbage, especially sauerkraut, is another important ingredient of old Polish cuisine, according to the corpus analysis. Recipes for cabbage dishes contain keywords related to fermenting foods and boiling and stewing.

- (5)

- Table setting: the corpus offers extensive instructions on etiquette, table setting, and table manners. This conclusion is supported by the frequent use of the words ‘table’, ‘tableware’, and ‘decoration’. A significant part of the text concerns the aesthetic side of meals, table arrangements, and proper serving principles.

Prompt: Assess the text’s sentiment, please. Next, determine whether the overall message of the sample is positive, neutral, or negative. Thank you.

Synthesised (summarised) AI’s responses: According to ChatGPT, the text is neutral. The recipes and instructions focused on practical performance and providing information. They are intended to instruct the reader on how to prepare food and serve it aesthetically. The corpus is dominated by technical vocabulary related to cooking and food preparation, such as ‘flour’, ‘sugar’, ‘butter’, ‘boil’, ‘roast’, ‘bake’, and ‘fry’. Such words and their contexts do not express emotions. Instead, they convey actions, instructions, and descriptions of necessary ingredients. Additionally, the text has an educational function. It aims at transferring knowledge rather than provoking specific feelings or emotions.

Some excerpts may invoke subtle positive emotions when table arrangements or meal-related occasions are described. They may bring to mind hospitality, warm welcome, and traditions. Still, the general sentiment is neutral and free of emotions. As a whole, it offers no judgment, praise, or criticism, which confirms its neutrality.

Prompt: Evaluate the text to see whether it has some features of the Old Polish language, please.

Synthesised (summarised) AI’s responses: According to ChatGPT, the text has some features of Old Polish that are evident in the vocabulary and grammatical structures. Such frequent phrases as ‘ukrop’ (in its obsolete meaning of scolding/boiling water), ‘szabaśnik’ (an old type of kitchen oven), or ‘karafka’ (in the archaic meaning of water jug) suggest old linguistic forms. The grammatical structures are extensive, and the word order is typical of the previous stages of the Polish language’s evolution when longer and more grammatically ambiguous phrases were used. The style also aligns with past housekeeping guides aimed at educating on preparing meals in line with traditions and set ceremonies.

4.2. Results of Formal Prompts

4.2.1. LSA and TF-IDF Analyses

Prompt: Analyse the corpus using the LSA method, please. Analyse the corpus using the TF-IDF method, please. Thank you.

Synthesised (summarised) AI’s responses: The LSA identified three primary topics in the corpus. The first one, baked products, cakes, and biscuits, is based on selected food ingredients, such as ‘sugar’, ‘flour’, ‘yolks’, and ‘cream’. The coherence in the keyword set and their high weights suggest that these terms are critical and most frequent in the context of baking. The second topic concerns keywords related to table setting and food serving. Such fragments as ‘for the table to be set in an aesthetic way’ and ‘set the table for breakfast and supper’ that describe the aesthetic and functional aspects of table setting are relevant here. The third topic concerns main courses dominated by potatoes and cabbage, which is evident from the frequency of words like ‘potatoes’, ‘cabbage’, ‘onion’, ‘water’, and ‘roux’.

The results of the LSA are corroborated by the TF-IDF analysis. Words: ‘flour’, ‘sugar’, ‘yolks’, and ‘cream’ have higher weights in recipes for sweet baked products, such as ‘sweet pretzels’ or ‘Warsaw biscuits’. The high values of TF-IDS metrics of these words emphasise their central roles in confectionery recipes. The weight of the words ‘sugar’ and ‘flour’ indicates their significance as the primary ingredients of most sweet baked products, which sets them apart from recipes for main courses, soups, or sauces/gravies. In the main course category, high TF-IDF weights were assigned to ‘potatoes’, ‘onion’, and ‘water’. In recipes for more complex dishes, like rice and meat stuffed cabbage, high weights were assigned to ‘cabbage’, ‘rice’, and ‘meat’. Their higher weights indicate their significance as basic ingredients and highlight their uniqueness within the corpus. Rarely appearing outside of the context of main dish recipes, the words have high TF-IDF weights, which demonstrates their central roles in the text. Words like ‘important’ and ‘in order to’ have higher weights in sections on table setting and food serving rules. This suggests the fragments on table savoir vivre have special word sets different from more technical descriptions of food preparation.

4.2.2. Stylometry Results

Prompt: Run stylometry, please. Thank you.

Synthesised (summarised) AI’s responses: Stylometry revealed that the corpus has features typical of Old Polish. The average word length is 5.2 characters, which indicates frequent use of longer words, typical of slightly older texts. The average sentence has 18 words. The text uses compound sentences, suggesting a more formal and descriptive style. Archaic expressions constitute a significant 15%, which confirms the historical nature of the corpus.

The most frequent archaisms include ‘karafka’ (water jug), ‘szabaśnik’ (type of oven), ‘ukrop’ (hot water), and ‘karminować’ (to decorate). The frequency analysis of parts of speech revealed a 1.8:1 rate of nouns to verbs, which implies a descriptive approach focused on specific instructions on the ingredients, dishes, and activities in the kitchen. The dominance of nouns and adjectives fuels the descriptive style typical of food guides.

4.2.3. Results of Pragmatic and Sociolinguistic Analyses

Prompt: Conduct a pragmatic and sociolinguistic analysis, please. Thank you.

Synthesised (summarised) AI’s responses: The text clearly concentrates on educating and providing practical guidelines to people who seek culinary knowledge and want to learn the principles of aesthetic and gracious meal serving. The language and style suggest that the text could be intended for people from higher strata of society or for those aspiring to emulate the behaviour of such social classes, for whom food was not only a pragmatic need but also a matter of status.

The text contains archaisms and phrases typical of Old Polish, indicating that it preserves recipes and linguistic heritage. Such language could have a social function building the national identity and emphasising the importance of traditions. Words like ‘szabaśnik’ or ‘karafka’ refer to objects typical of the Polish culinary culture of the past, which makes the text an important historical and cultural document.

The text is a guide to kitchen practices and instructs on proper food serving. It is intended to provide the reader with specific guidelines regarding measures, proportions, techniques, and principles of food preparation and table setting. Not only does the text inform, but it also sets standards for preparing and serving meals, which may suggest its role in housekeeping education and in professional food service circles.

4.3. Portrayal of the Household and Household Role of Women in Post-War Poland

Prompt: Based on the corpus analysis, describe a typical household in Poland right after the Second World War and the role of women in this household. Thank you.

Synthesised (summarised) AI’s responses: The AI algorithm described the pre-war Polish household as a space dominated by traditional values and attention to everyday rituals related to serving and eating food. The kitchen was the central point of the household. It was where food was prepared and familial relationships were nurtured. According to the AI, everyday life followed the rhythm of three main meals prepared and served with utmost care. The table setting was just as important as the food. Pleasing aesthetics and cleanliness were considered tokens of care for the family and visitors.

According to the AI’s interpretation, women were critical in running the household of post-war Poland. They planned and prepared meals. They are the guardians of the hearth, maintaining harmony and order. Their work was the foundation of the family life, where (according to the AI) ‘the house was a place of respite as well as a spiritual harbour. The woman of the post-war Poland household stood for resourcefulness, care, and peerless catalysts of the familial community.’ According to the AI, the contents of the notebooks demonstrate women’s creativity and confirm their engagement in caring for the family.

5. Discussion

5.1. Observations and Expert Assessment

The primary objective of the digitisation was to record hand-written notes in a digital form. The process required particular efforts considering that some fragments were illegible, the names archaic, and the handwriting varied over time. Additionally, the notebooks are in poor condition as they were written right after the Second World War. These problems hindered the digitisation process.

The dedication of the digitisation team helped decipher many hardly legible phrases. They had to exercise patience when identifying letter variants and studying historical sources to interpret some writings properly. Some words, especially ingredients and dishes, had to be looked up. Recipes where the author used abbreviations instead of complete words posed a particular challenge. Such fragments could have been written hastily from dictation. Another sign of hasty note-taking is that many recipes are incomplete, and consecutive sentences are incoherent. This suggests that the author has never verified or revised the notes and considered them clear enough to use in everyday applications.

She employed succinct phrases. The recipes are written in simple and factual language. The text has spelling and logical errors, as well as frequent repetitions and grammatical and syntactic errors. The style is often instructional (lists of preparation stages), with some parts of sentences missing and no paragraphing (long blocks of text). Sometimes, although not very often, the author employed traditional vivid metaphors, such as ‘gotować/smażyć do nitki’ (cook/fry until the liquid forms threads when pulled up) or ‘ucierać do białości’ (cream until white).

5.2. Reflection of Culinary and Domestic Culture in Post-War Poland

The analysed school notebooks are a unique testament to social and educational changes in post-war Poland. They are records of the practical aspect of teaching housekeeping, gastronomy, and everyday ethics. The documents also reflect the process of restoration of community life and women’s education after the Second World War. Therefore, they align with the broader research on intangible heritage, where daily practices, including cooking, perpetuate cultural memory (Assmann, 2011). One can re-create the realities of rural life and the values inherent to the women of the twentieth century by analysing such records. In this context, language models were merely a tool to aid interpretation by identifying linguistic and semantic patterns. Still, they do not replace historical reflection. This attitude is consistent with the digital humanities paradigm, where technology is auxiliary to the traditional source analysis (Drucker, 2020).

Most of the recipes in the notebooks are based on staple rural ingredients of post-war Poland, such as eggs, flour, butter, cream, cheese, potatoes, and cabbage. Therefore, they accurately represent the diet of rural communities at that time. Furthermore, the notes reveal links between food and folk rites and traditions. The notebooks contain some recipes for special occasion meals, which shows their cultural relevance. The text is also a witness to the changing attitudes toward dietary habits. It reflects the advancing knowledge of the nutritional values of individual products and illustrates changing views on the relationship between health and well-being and a balanced diet.

The meal planning charts, along with calculations of ingredient consumption and food cost for the entire family, suggest that housewives were expected to be able to organise and plan the household budget. The classes included special diets for particular health problems.

5.3. Hallucinations, Embellishment, or Misinterpretation?

The results offered by ChatGPT are useful and generally correct. Still, the authors noted certain hallucinations, or rather significant embellishments of the description of the corpus, diverging from the actual content. This phenomenon is also confirmed in the literature (Król, 2025a). The algorithm seems to magnify certain characteristics or misinterpret the content and assign features of which it has none. The AI described the corpus with specific phrases, like ‘very traditional in nature’, ‘old kitchen ceremonies’, ‘attention to details’, ‘ceremonial dimension’, ‘culinary aesthetics guide’, ‘cooking was a complex ritual’. Moreover, according to the AI, the notebooks were written in a vivid, almost poetic language ‘which not only makes the text sound historical but also moves the reader back to times when meals were nearly ceremonial and cooking and serving food were a form of art. Careful wording and detailed instructions suggest that the document was not only a cookbook but also a culinary aesthetics guide’. On the contrary, the content is much more mundane, and this characteristic is far from accurate. The notebooks are not as sophisticated. They are written in a simple language of instructions and spotted with errors. In fact, these are hasty class notes of a teenage pupil rather than literary-style records of the past era, which only confirms their authenticity.

6. Conclusions

The article reports an interdisciplinary study. It combines historical, linguistic, and technological approaches. Therefore, the insights may be useful to experts in digital humanities and researchers of cultural heritage, applied linguistics, and AI tool designers. In fact, the pre-processing and digitisation of Granny Josie’s Notebooks contribute to preserving Poland’s intangible cultural heritage.

During the analysis, the author took into account the language models’ propensity for overinterpretation and narrative ‘embellishments’ of the content, particularly regarding social roles and cultural contexts. This is due to the intrinsic characteristics of training data and LLMs, which reproduce dominant linguistic and cultural patterns from their sources. The study intentionally maintains a neutral voice, avoiding excessive emotional or ideological interpretations of the text. This qualification is considered indispensable to ensure faithfulness to the input, where any signs of emotions or judgment are subtle and regard mainly hospitality, care, and community, and are declared explicitly.

The notebooks offer more than just historically valuable knowledge about traditions in Polish households. They also vouch for the regional culinary heritage. ChatGPT, a Large Language Model, identified three main topics in Granny Josie’s Notebooks: baking (confectionery recipes), table setting and food serving culture, and main courses (dinner). The topics reflect the diversity of traditional Polish cuisine and a specific attitude towards food serving aesthetics. They also reveal the main ingredients used in food preparation. Moreover, the AI analysis suggests that women were central to housekeeping in post-war Poland as guardians of the hearth.

Practical Implications and Research Limitations

The reported case study is an analysis of school notebooks from 1946 to 1947. The results demonstrate how digital humanities and AI analysis can be used to investigate cultural heritage. They do not offer any generalisation. The lack of a control is an intentional methodological decision to preserve the integrity and consistency of the corpus. Future research will include comparisons with other sources, including texts from various areas of Poland.

An independent analysis by linguists confirmed the general accuracy of the results and conclusions offered by the LLM. Nevertheless, they demonstrated that the characteristics drafted by the AI contained misinterpretations and embellishments even though the prompts were neutral. The analysis also revealed more details of the content and writing situation. It may be because, put simply, LLMs use the frequency of specific character strings in the corpus and data aggregation, which makes the results and conclusions rather general compared to an in-depth and detailed expert assessment. Consequently, LLMs and tools like ChatGPT can assist with research work but are incapable of replacing expert analysis as such. Large language models can be narratively biased by the profile of training data, which can affect how they generate descriptions and classify emotions, to some extent. This impact was limited in the study through a manual verification of the interpretations and comparison with quotes from the corpus, focusing on semantic consistency rather than emotional evaluation.

Large Language Models’ answers adapt to user expectations. If the user expects a specific tone or style, the answer is worded to satisfy the requirements in the prompt. As a result, LLM’s corpus evaluation largely depends on the wording of the prompt. For the results to be as objective as possible without potential manipulations, the scope of the analysis has to be clearly defined without suggesting a perspective. The prompts used in the study seem to conform to this policy because they contain only a list of analyses without hints at the potential results.

The study takes into account methodological limitations linked to the application of the GPT-4o language model for the semantic and stylometry. The very nature of the ChatGPT environment prevents access to the model’s internal parameters, complete intermediary results, or error metrics, which limits full computational replicability. Therefore, the results should be considered a qualitative synthesis of the data instead of a statistical experiment. The corpus size reflected the exploratory nature of the study, which focused on identifying semantic and linguistic patterns rather than on quantitative conclusions. The recurrence of some words and motifs, typical of culinary and school notes, was considered genre-specific, not a source of errors. These limitations do not affect the interpretability of the results, which remain consistent with expert observations and confirm the potential of language models regarding analysing historical corpora.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at Corpus (research data): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27889698 (accessed on: 19 September 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K.; methodology, K.K.; software, K.K.; validation, K.K., M.S. and E.L.; formal analysis, K.K., M.S. and E.L.; investigation, K.K., M.S. and E.L.; resources, K.K., M.S. and E.L.; data curation, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K., M.S. and E.L.; writing—review and editing, K.K.; visualisation, K.K.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Co-financed by the Minister of Science under the ‘Regional Initiative of Excellence’ programme. Agreement No. RID/SP/0039/2024/01. Project period: 2024–2027.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-4o, OpenAI) for the purpose of linguistic analysis of a text corpus. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GPT | Generative Pre-Trained Transformer |

| LLM | large language model |

| LSA | Latent Semantic Analysis |

| TF-IDF | Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency |

References

- Assmann, J. (2011). Cultural memory and early civilization: Writing, remembrance, and political imagination. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birhane, A., Kasirzadeh, A., Leslie, D., & Wachter, S. (2023). Science in the age of large language models. Nature Reviews Physics, 5, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci Cante, L., Di Martino, B., Graziano, M., Branco, D., & Pezzullo, G. J. (2024). Automated storytelling technologies for cultural heritage. In L. Barolli (Ed.), Advances in internet, data & web technologies (Vol. 193, pp. 597–606). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, J. (2020). Visualization and interpretation: Humanistic approaches to display. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fontefrancesco, M. F., & Zocchi, D. M. (2020). Reviving traditional food knowledge through food festivals. The case of the pink asparagus festival in Mezzago, Italy. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 596028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonteyn, L., Manjavacas, E., Haket, N., Dorst, A. G., & Kruijt, E. (2024). Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings. Linguistics Vanguard, 10, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrlant, L., & Kreinovich, V. (2017). A simple probabilistic explanation of term frequency-inverse document frequency (Tf-Idf) heuristic (and variations motivated by this explanation). International Journal of General Systems, 46, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, A. (2010). Complexity in cultural identity. Language and Intercultural Communication, 10, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E., Sessler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., … Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, W., & Król, K. (2023). Inclusion of vanishing cultural heritage in a sustainable rural development strategy–prospects, opportunities, recommendations. Sustainability, 15, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K. (2025a). Between truth and hallucinations: Evaluation of the performance of large language model-based AI plugins in website quality analysis. Applied Sciences, 15, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K. (2025b). Mapping keywords in Granny Josie’s culinary heritage using large language models. Heritage, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, T. K., Foltz, P. W., & Laham, D. (1998). An introduction to latent semantic analysis. Discourse Processes, 25, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-S. (2023). Cooking up food memories: A taste of intangible cultural heritage. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, E. (2020). Rozwój i transformacja polskiego szkolnictwa po II wojnie światowej. Uniwersytet Jagielloński. [Google Scholar]

- Mącior, B., Mądel, A., Podraza, S., Wójtowicz, E., & Zięba, P. (2017). Szynwałd—Tak było. Historia Szynwałdu na starych fotografiach i dokumentach. Stowarzyszenie Mój Szynwałd. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, M. S. U., Kabir, M. M., Sarwar, T. B., Safran, M., Alfarhood, S., & Mridha, M. F. (2024). A multimodal approach to cross-lingual sentiment analysis with ensemble of transformer and LLM. Scientific Reports, 14, 9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejjar, M., Zacharias, L., Stiehle, F., & Weber, I. (2025). LLMs for science: Usage for code generation and data analysis. Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, 37, e2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitu, M., & Dascalu, M. (2024). Beyond lexical boundaries: LLM-generated text detection for Romanian digital libraries. Future Internet, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenstrakh, M. S., Karnalim, O., Suárez, C. A., & Liut, M. (2024, July 2). Detecting LLM-generated text in computing education: Comparative study for ChatGPT cases. 2024 IEEE 48th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC) (pp. 121–126), Osaka, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Partarakis, N., Kaplanidi, D., Doulgeraki, P., Karuzaki, E., Petraki, A., Metilli, D., Bartalesi, V., Adami, I., Meghini, C., & Zabulis, X. (2021). Representation and presentation of culinary tradition as cultural heritage. Heritage, 4, 612–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachabatuni, P. K., Principi, F., Mazzanti, P., & Bertini, M. (2024, April 15). Context-aware chatbot using MLLMs for cultural heritage. ACM Multimedia Systems Conference 2024 on ZZZ (pp. 459–463), Bari, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, M., McDonell, K., & Reynolds, L. (2023). Role play with large language models. Nature, 623, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SpeechTexter. (2025). Available online: https://www.speechtexter.com (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Świgost-Kapocsi, A. (2021). 200 Years of feminisation of professions in Poland—Mechanism of false windows of opportunity. Sustainability, 13, 8179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulos, G., Konstantakis, M., Caridakis, G., Katifori, A., & Koukouli, M. (2023). Crafting a museum guide using ChatGPT4. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, S. (2024). Using early LLMs for corpus linguistics: Examining ChatGPT’s potential and limitations. Applied Corpus Linguistics, 4, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasic, I., Fill, H.-G., Quattrini, R., & Pierdicca, R. (2024). LLM-aided museum guide: Personalized tours based on user preferences. In L. T. De Paolis, P. Arpaia, & M. Sacco (Eds.), Extended reality (Vol. 15029, pp. 249–262). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Wharton, T. (2010). Recipes: Beyond the words. Gastronomica, 10, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Xiang, R., Kuang, Z., Wang, B., & Li, Y. (2024). ArchGPT: Harnessing large language models for supporting renovation and conservation of traditional architectural heritage. Heritage Science, 12, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).