Abstract

To improve the comprehensive performance of indium oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric materials, this study systematically investigates the regulatory effects of tantalum (Ta) doping on their electrical transport characteristics, thermoelectric conversion efficiency, and mechanical properties. The results show that Ta doping achieves synchronous optimization of multiple properties through precise regulation of crystal structure, electronic structure, and microdefects. In terms of electrical transport, the electron doping effect of Ta5+ substituting In3+ and the introduction of impurity levels lead to a continuous increase in carrier concentration; lattice relaxation and impurity band formation at high doping concentrations promote mobility to first decrease and then increase, resulting in a significant growth in electrical conductivity. Although the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient slightly decreases, the growth rate of electrical conductivity far exceeds the attenuation rate of its square, increasing the power factor from 1.83 to 5.26 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K). The enhancement of density of states near the Fermi level not only optimizes carrier transport efficiency but also provides electronic structure support for synergistic performance improvement. For thermoelectric conversion efficiency, the substantial increase in power factor collaborates with thermal conductivity suppression induced by lattice distortion and impurity scattering, leading to a leapfrog increase in ZT value from 0.055 to 0.329 (973 K). In terms of mechanical properties, lattice distortion strengthening, formation of strong Ta-O covalent bonds, and dispersion strengthening effect significantly improve the Vickers hardness of the material. Ta doping breaks the bottleneck of mutual property constraints in traditional modification through an integrated mechanism of “electronic structure regulation-carrier transport optimization-multiple performance synergistic enhancement”, providing a key strategy for designing high-performance indium oxide-based thermoelectric materials and facilitating their practical application in the field of green energy conversion.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the global energy structure transformation and the advancement of the “dual carbon” goals, energy shortage and environmental pollution have become core challenges restricting the sustainable development of human society. A large amount of medium and low-temperature waste heat generated in industrial production, transportation, and the operation of electronic equipment (such as automobile exhaust waste heat and factory waste heat) has long been wasted due to the lack of efficient recovery technologies [1,2,3]. This not only intensifies energy consumption but also causes environmental problems such as greenhouse gas emissions. As a functional material capable of direct mutual conversion between “thermal energy and electrical energy”, thermoelectric materials, with their unique advantages of no moving parts, no noise pollution, high reliability, and low maintenance costs, provide a key technical path for the resource utilization of waste heat and the development of new clean energy devices [4,5]. In the aerospace field, radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) based on thermoelectric materials have successfully supplied energy to deep-space probes; in the civil field, their applications in thermoelectric power supply for portable electronic devices, industrial waste heat power generation devices, and high-precision temperature control systems are gradually promoting the transformation of energy utilization modes from “passive consumption” to “active recovery” [6,7,8]. Therefore, developing high-performance thermoelectric materials and improving their thermoelectric figure of merit (ZT value) to break through the bottleneck of energy conversion efficiency are of great scientific significance and engineering value for alleviating energy pressure and building a green and low-carbon energy system.

Compared with traditional thermoelectric materials, oxide thermoelectric materials also have the characteristics of being non-oxidizable, non-toxic, and pollution-free, which is in line with the concept of green and sustainable development [9,10,11]. However, oxide thermoelectric materials also have some deficiencies at present. Their thermoelectric performance mainly depends on the dimensionless thermoelectric figure of merit ZT. Currently, the ZT values of oxide thermoelectric materials are generally low, which is difficult to meet the requirements of practical applications. This is mainly because there is a strong mutual coupling among the Seebeck coefficient, electrical conductivity, and thermal conductivity that determines the thermoelectric performance of the material. Moreover, the preparation process of oxide thermoelectric materials needs to be improved, with problems such as a complex process, high cost, and low production efficiency. Indium oxide is an intrinsic n-type semiconductor material with electrons as the main carrier type. As an oxide, it has the advantages of low cost and non-toxicity. At the same time, indium oxide-based materials have a certain potential in thermoelectric applications, and high thermoelectric performance is expected to be achieved through doping and other means [12,13,14]. However, pure indium oxide also has some disadvantages. Its electrical conductivity is low, and its intrinsic thermal conductivity is high, which makes it difficult to improve its thermoelectric figure of merit. For example, in practical applications, pure indium oxide is difficult to effectively convert heat energy into electrical energy. In order to improve the thermoelectric performance of indium oxide, it is necessary to modify it by doping, such as Mo-doping, to adjust its electrical conductivity and thermal conductivity, thereby increasing its thermoelectric figure of merit [15,16]. Hardness stands as a pivotal mechanical property for thermoelectric (TE) modules, with profound implications for their reliability, durability, and practical applicability [17,18]. TE modules operate under inherent thermal cycling conditions—alternating heating and cooling cycles during service induce significant thermal stress at the interfaces between TE legs, electrodes, and substrates. This cyclic stress often triggers microcracking, delamination, or even catastrophic failure if the TE materials lack sufficient hardness to resist plastic deformation and crack propagation. Specifically, the TE legs, which are the core functional components, must maintain structural integrity under repeated thermal loading; a higher hardness ensures enhanced resistance to wear, indentation, and mechanical damage during module fabrication (e.g., cutting, bonding) and long-term operation. Moreover, mechanical robustness directly influences the module’s service life [19,20], as soft TE materials are prone to creep deformation and dimensional instability when exposed to elevated temperatures over extended periods. In addition, hardness is closely correlated with other critical mechanical properties such as fracture toughness and Young’s modulus, which collectively determine the module’s ability to withstand thermal shock and mechanical vibrations in real-world applications (e.g., automotive exhaust systems, industrial waste heat recovery). For TE technology to achieve widespread commercialization, addressing the mechanical limitations—particularly through optimizing hardness—has become imperative, as even high thermoelectric performance (ZT value) is rendered irrelevant if the module fails prematurely due to mechanical degradation. Thus, investigating the hardness of TE materials is not merely a fundamental research pursuit but a practical necessity to bridge the gap between lab-scale performance and industrial reliability.

High-valence Ta-doped indium oxide thermoelectric materials are used to enhance thermoelectric performances and Hardness. The core innovation of Ta-doped indium oxide (In2O3) lies in the donor effect induced by high-valence element doping. Tantalum (Ta), as a +5 valence element, replaces indium (In3+) in the In2O3 lattice. For each Ta3+ ion substituted, two free electrons are generated to maintain charge neutrality. This targeted electron injection breaks the limitation of traditional low-valence doping (e.g., Sn4+ doping, which only provides one free electron per substitution) and realizes efficient regulation of carrier concentration. Meanwhile, the ionic radius of Ta5+ (0.064 nm) is close to that of In3+ (0.080 nm), which avoids severe lattice distortion while introducing carriers. This “high-efficiency carrier supply + low lattice damage” doping strategy is a key innovation in optimizing the electrical transport properties of oxide thermoelectric materials. While improving electrical conductivity, Ta doping also optimizes the thermal transport performance of In2O3. On the one hand, the slight difference in ionic radius between Ta5+ (0.064 nm) and In3+ (0.080 nm) could cause mild lattice distortion, which enhances the scattering of phonons (the main carriers of heat). On the other hand, during the doping process, local defect complexes (such as Ta-In antisite defects and oxygen vacancies) could form, which further block the transmission of medium and low-frequency phonons. By combining the optimization of conductivity and thermal conductivity, the thermoelectric performance of indium oxide could be improved.

2. The Results and Discussions

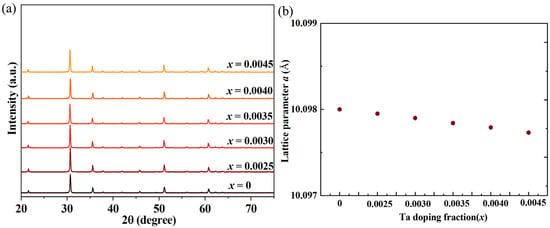

Figure 1 presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of Tantalum (Ta)-doped indium oxide (In2O3). The diffraction pattern exhibits exclusively the characteristic peaks corresponding to the cubic bixbyite structure of pure In2O3. No extraneous peaks attributable to secondary phases, such as tantalum oxide (Ta2O5) or other Ta-In-O compounds, are detected within the resolution limits of the XRD instrument. The decreased lattice constants confirmed an overall contraction of the lattice constant in the Ta-doped sample compared to the pristine In2O3 (The Sigmas we refined are shown in Table 1). The conjunction of phase purity and lattice contraction provides compelling evidence that Ta has been effectively incorporated into the In2O3 crystal structure. However, unlike the isovalent substitution seen with La3+, the incorporation mechanism for Ta5+ is more complex and involves aliovalent (heterovalent) substitution. This process is the primary cause of the observed lattice shrinkage. The underlying reason can be attributed to two interconnected factors: the ionic radius difference and the charge compensation mechanism. The ionic radius of the host cation In3+ in six-fold coordination is approximately 0.80 Å. The ionic radius of the dopant cation Ta5+ in six-fold coordination is approximately 0.64 Å. There is a significant size mismatch, with Ta5+ being about 20% smaller than In3+. When a smaller Ta5+ ion directly replaces a larger In3+ ion at its crystallographic site, it pulls the surrounding oxygen ions inward, leading to a local contraction of the lattice around the dopant atom. This direct substitution contributes to the overall reduction in lattice constant.

Figure 1.

(a) XRD patterns of Ta-doped In2O3 thermoelectric materials; (b) Lattice constant variation of In2O3 with different Ta doping contents.

Table 1.

The refined results of Celref (when the Sigmas is refined to below 0.0005, the lattice parameters are supposed to be reliable).

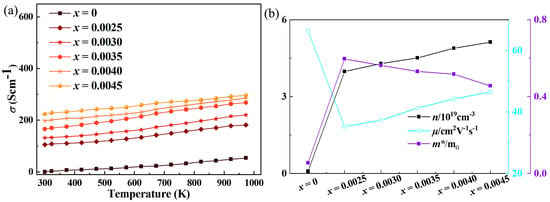

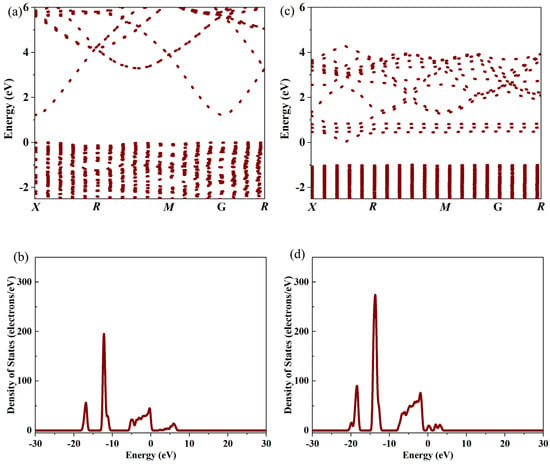

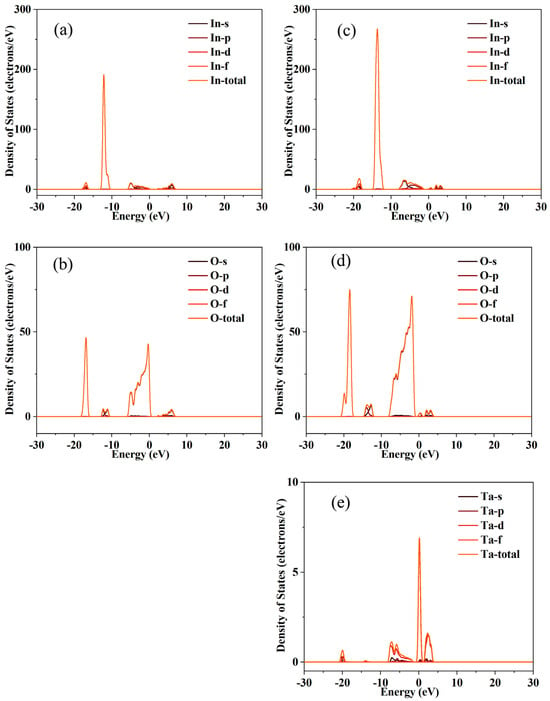

Experimental studies have found that in Ta-doped In2O3 thermoelectric materials, with the increase in Ta doping concentration, the electrical conductivity increases significantly, accompanied by a continuous increase in carrier concentration and a non-monotonic change in mobility (first decreasing and then increasing) as shown in Figure 2. First-principles calculation results show that Ta doping introduces impurity levels near the Fermi level of In2O3, leading to a significant enhancement of the system’s density of states (DOS) as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. The crystal structure of In2O3 is a body-centered cubic structure (bixbyite structure) with a space group of Ia-3, where In3+ ions occupy two different lattice sites (octahedral coordination and tetrahedral coordination), and O2− ions form a face-centered cubic packing. The band gap of pure In2O3 is approximately 3.75 eV, and intrinsic carriers are mainly derived from intrinsic defects such as oxygen vacancies, whose concentration is usually low, leading to limited electrical conductivity. When Ta is doped into In2O3, a typical electron-doping effect occurs due to the valence difference between Ta5+ and In3+. When Ta5+ substitutes for In3+ in the In2O3 lattice, to maintain the electrical neutrality of the crystal, each Ta5+ ion introduced releases two free electrons into the system. With the increase in Ta doping concentration, more and more Ta5+ ions enter the In2O3 lattice, replacing the positions of In3+, thereby continuously injecting free electrons into the system, directly leading to a significant increase in carrier concentration [21]. Compared with carriers generated by intrinsic defects, the electron concentration introduced via doping is more precisely controllable by adjusting the doping dosage and achieves higher levels, thus serving as the primary contributor to increased carrier concentration. As a 5d-group element, tantalum (Ta) features a large atomic number, extended electron cloud distribution, and strong interactions with oxygen (O) atoms, rendering the Ta–O bond more covalent than the In–O bond. This alteration in chemical bonding facilitates electron migration within the lattice, mitigates electron localization, and further boosts carrier concentration. Notably, Ta doping does not severely compromise the crystalline integrity of In2O3, preserving unobstructed lattice pathways for carrier transport and providing structural support for sustained carrier concentration elevation. Mobility reflects the ease of carrier movement in the lattice and is primarily governed by lattice scattering, impurity scattering, and defect scattering. At low Ta doping concentrations, mobility decreases with increasing doping levels, mainly due to intensified impurity scattering. When Ta5+ ions substitute In3+ in the lattice, differences in ionic radius, atomic weight, and electronegativity between Ta5+ and In3+ induce local lattice distortion and potential fluctuations, which scatter moving electrons and impede their directional transport, thus reducing electron mobility. At low doping concentrations, Ta atoms exist predominantly in an isolated state, with each Ta ion acting as an independent scattering center. Higher doping concentrations increase the number of scattering centers, elevating electron-scattering center collision probability and exacerbating mobility decline. Meanwhile, the limited increase in carrier concentration partially offsets the negative impact of reduced mobility on conductivity, resulting in a moderate upward trend in conductivity. Moreover, interactions between intrinsic defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies) and Ta dopants may form composite defects, increasing lattice disorder and introducing additional electron scattering, leading to further mobility reduction. When Ta doping concentration exceeds a critical threshold, mobility increases with further doping, which is associated with lattice relaxation, impurity band formation, and scattering mechanism transformation. First, high doping concentrations enable extensive Ta5+ incorporation into the In2O3 lattice; lattice self-relaxation accommodates ionic radius differences, alleviating local distortion, regularizing atomic positions, and reducing distortion-induced scattering, thus providing smoother electron transport pathways. Meanwhile, uniform Ta distribution at high doping levels avoids local ion aggregation and minimizes strong scattering center formation, further weakening impurity scattering. Second, high doping concentrations significantly increase impurity level density, forming a continuous impurity band that overlaps with the conduction band minimum. This shifts electron transport from hopping to band conduction, where electrons experience weaker scattering and exhibit higher mobility. Impurity band formation also broadens the electron transport energy range, enabling free electron movement across a wider spectrum and further improving mobility. Finally, the substantial carrier concentration increase at high doping levels enhances carrier-carrier interactions, forming an electron gas that shields the Coulomb potential field of impurity ions, weakening Coulomb scattering and reducing electron scattering probability. Additionally, high carrier concentrations mitigate phonon-induced lattice scattering, further promoting mobility improvement. In the high doping regime, improved mobility and sustained carrier concentration growth synergistically drive rapid conductivity enhancement, leading to a pronounced upward trend in conductivity with increasing doping levels. The density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level directly reflects the number of electrons that the system can accommodate at this level. Ta doping introduces impurity levels that significantly enhance the Fermi-level DOS. As Ta doping concentration rises, impurity level density increases, further enhancing the Fermi-level DOS. When DOS reaches a critical value, the Fermi level shifts toward and enters the conduction band, conferring degenerate semiconductor characteristics. In degenerate semiconductors, carrier concentration follows the Fermi-Dirac distribution instead of the Boltzmann distribution, maintaining high carrier concentrations even at room temperature. This degenerate transition further elevates the saturation carrier concentration, enabling continuous carrier concentration growth with increasing doping levels and sustaining conductivity enhancement. Additionally, enhanced DOS affects electron effective mass. Interactions between Ta-induced impurity levels and In2O3 conduction band states reduce electron effective mass, which facilitates higher mobility because smaller effective mass decreases electron inertial resistance in the lattice and weakens scattering effects, further promoting electron transport. Enhanced Fermi-level DOS not only increases carrier concentration but also improves electron transport efficiency. High DOS provides more electronic states near the Fermi level for electron occupation; during transport, electrons can rapidly transition to adjacent states, minimizing energy loss. Impurity levels also reduce electron localization, enhance electron cloud overlap, and promote electron delocalization, enabling free electron movement throughout the lattice and increasing transport range and rate. Furthermore, high DOS increases electron transition probability, allowing electrons to quickly find new transport pathways after scattering, reducing transmission residence time, and further improving transport efficiency. In Ta-doped In2O3, the synergistic effects of enhanced Fermi-level DOS, increased carrier concentration, and non-monotonic mobility variation collectively drive substantial conductivity enhancement. Particularly in the high doping regime, the significant DOS enhancement drastically improves electron transport efficiency, which, combined with high carrier concentration and improved mobility, synergistically pushes conductivity to high levels.

Figure 2.

(a) Electrical conductivity test results of In2O3 thermoelectric materials with different Ta doping contents; (b) Corresponding characterization results of carrier concentration (n), mobility(μ), and effective mass (m*/m0).

Figure 3.

(a,b) Band structure and density of states (DOS) of pure In2O3; (c,d) Band structure and density of states (DOS) of Ta-doped In2O3.

Figure 4.

(a,b) Electronic partial density of states (PDOS) diagrams of undoped In2O3; (c–e) Electronic partial density of states (PDOS) diagrams of Ta-doped In2O3.

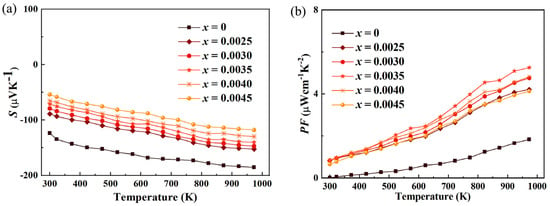

Figure 5a shows the Seebeck coefficient of Tantalum (Ta)-doped Indium Oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric material. It can be observed that the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient decreases significantly after doping. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the fundamental changes in the electrical transport properties of the material induced by doping, specifically reflected in the increased electrical conductivity, the significantly increased carrier concentration, and the potentially decreased mobility. Firstly, and most crucially, Ta doping greatly increases the carrier concentration of the material. Intrinsic indium oxide is typically an n-type semiconductor with a limited carrier concentration. When high-valence Ta5+ ions substitute for In3+ ions in the crystal lattice, each Ta atom contributes two extra electrons to the conduction band. This process acts as an electron doping, effectively injecting a large number of free electrons into the system. According to the fundamental formula for the Seebeck coefficient (for n-type materials, S is negative, and we discuss its absolute value), S ∝ 1/n^(2/3) (under degenerate conditions), where S is the Seebeck coefficient and n is the carrier concentration. This formula clearly indicates that the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient is inversely proportional to the 2/3 power of the carrier concentration. Consequently, when Ta doping causes a sharp increase in n, the absolute value |S| inevitably decreases. This is the primary physical mechanism responsible for the phenomenon observed in Figure 5. Secondly, the increase in electrical conductivity (σ) is also closely related to the decrease in the Seebeck coefficient. Electrical conductivity is determined by the formula σ = n e μ, where e is the electron charge and μ is the electron mobility. As mentioned, Ta doping significantly increases n. Even if the mobility μ decreases somewhat due to enhanced ionized impurity scattering (detailed below), the dramatic increase in n usually dominates, ultimately leading to an overall increase in electrical conductivity σ. In thermoelectric research, there is often a trade-off relationship between the Seebeck coefficient and electrical conductivity: high conductivity (implying stronger metallic character) is usually accompanied by a lower Seebeck coefficient. This is because a high density of carriers makes the asymmetry in the carrier energy distribution (i.e., the thermoelectric voltage) induced by a temperature gradient relatively smaller. Therefore, the increase in conductivity and the decrease in the Seebeck coefficient are two interconnected manifestations of the same physical process (increased carrier concentration).

Figure 5.

(a) Seebeck coefficient test results of In2O3 thermoelectric materials with different Ta doping contents; (b) Corresponding power factor calculation results.

In Ta-doped indium oxide materials, the significant improvement of power factor from 1.83 to 5.26 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K) as shown in Figure 5b essentially results from the compensation and surpassing of the decrease in the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient by the substantial increase in electrical conductivity. This is very competitive compared to 5.10 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K) for Nb doping with S = −147.05 μVK−1, 7.76 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K) for V doping with S = −128.93 μVK−1, 1.77 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K) for Mo doping with S = −361.23 μVK−1 [15,22,23]. Ta doping significantly increases the carrier concentration, leading to a continuous increase in carrier concentration. The enhancement of carrier concentration directly promotes a significant increase in electrical conductivity and provides core momentum for the growth of power factor. The decrease in the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient is an inevitable consequence of the increased carrier concentration. However, the significant enhancement of the density of states near the Fermi level can mitigate the decrease in the Seebeck coefficient, avoiding excessive negative impacts on the power factor. The final improvement of power factor stems from the fact that the growth rate of electrical conductivity far exceeds the decrease rate of the square of the Seebeck coefficient. At low doping concentrations, the increase in electrical conductivity offsets the negative impact of the decreased Seebeck coefficient, resulting in a steady growth of power factor. At high doping concentrations, the electrical conductivity shows an exponential increase with the synergistic improvement of carrier concentration and mobility, while the decrease in the Seebeck coefficient tends to level off. This makes the product of S2σ increase sharply, ultimately achieving a leapfrog growth of power factor from 1.83 for the undoped sample to 5.26 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K) for Ta-doped.

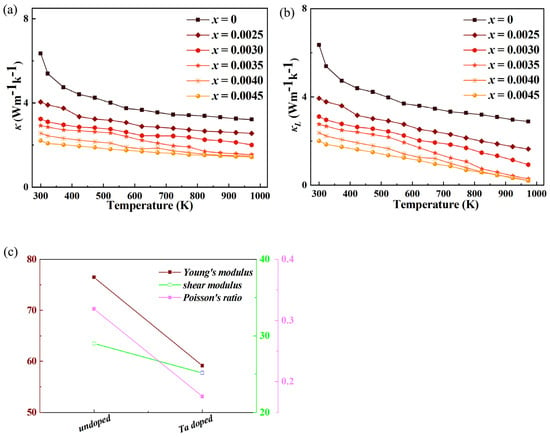

The thermal conductivity (κ) of thermoelectric materials is a key parameter determining their thermoelectric conversion efficiency, as it directly affects the temperature gradient maintenance in devices. For Ta-doped indium oxide, the overall thermal conductivity (κ) and lattice thermal conductivity (κL) both exhibit a significant decreasing trend with doping as shown in Figure 6. Combined with the previously observed variations, the intrinsic mechanism of thermal conductivity reduction can be analyzed as follows. First, enhanced carrier scattering induced by lattice distortion dominates the reduction in lattice thermal conductivity. Pure indium oxide (In2O3) has a relatively ordered cubic bixbyite structure, and lattice thermal conductivity is mainly transmitted through phonon propagation. When Ta5+ is doped into the In2O3 lattice to replace In3+, the significant difference in ionic radius between Ta5+ (0.064 nm) and In3+ (0.080 nm) causes severe local lattice distortion. This distortion breaks the original periodicity of the crystal lattice, generating a large number of lattice defects such as Ta-In antisite defects, oxygen vacancies (induced by charge compensation to balance the valence difference between Ta5+ and In3+). These defects act as strong scattering centers for phonons: low-frequency phonons (long-wavelength phonons) are scattered by large-scale defects (e.g., dislocation clusters), while high-frequency phonons (short-wavelength phonons) are scattered by point defects (e.g., antisite defects and oxygen vacancies) [24,25,26]. As a result, the mean free path of phonons is drastically shortened, and the efficiency of lattice thermal energy transmission is significantly reduced, leading to a notable decrease in κL. Since κL is the main component of κ in oxide thermoelectric materials, the reduction of κL directly drives the decline of κ. Second, the change in carrier transport behavior has a dual regulatory effect on thermal conductivity but does not reverse the overall downward trend. On one hand, the increase in carrier concentration (n) (consistent with the previously observed electrical conductivity enhancement) leads to a slight increase in electronic thermal conductivity (κe). According to the Wiedemann-Franz law, κe = L0σT (where L0 is the Lorenz number, σ is electrical conductivity, and T is absolute temperature). The elevated σ (caused by higher n) theoretically promotes κe. On the other hand, the reduced carrier mobility (μ) (resulting from lattice distortion and defect scattering) weakens the contribution of carriers to thermal conduction. The decrease in μ indicates that carriers (electrons) undergo more frequent collisions with defects during transport, reducing the efficiency of electronic thermal energy transmission and partially offsetting the κe increase caused by higher n. In Ta-doped indium oxide, the experimental results show that the increase in κe is far less than the decrease in κL. Therefore, the overall thermal conductivity still exhibits a decreasing trend. Third, the synergy between carrier transport and lattice dynamics further optimizes the thermal conductivity. The decrease in the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient (|S|) indirectly reflects the more uniform energy distribution of carriers. Although |S| itself does not directly affect thermal conductivity, its variation is closely related to carrier concentration and mobility—key factors influencing κe. The higher carrier concentration (which reduces |S|) increases the number of charge carriers participating in thermal conduction, but the reduced mobility (which also correlates with |S| reduction) limits the speed of carrier thermal energy transmission. This balance between carrier quantity and transport efficiency ensures that κe does not become a dominant factor in κ, allowing the lattice thermal conductivity reduction to remain the main driver of overall thermal conductivity decline. This synergy is crucial for optimizing the thermoelectric performance of Ta-doped indium oxide, as it achieves a simultaneous improvement in electrical conductivity (favorable for thermoelectric efficiency) and reduction in thermal conductivity (also favorable for thermoelectric efficiency), breaking the traditional trade-off between electrical and thermal transport properties to a certain extent.

Figure 6.

(a) Total thermal conductivity test results of Ta-doped In2O3 thermoelectric materials; (b) Lattice thermal conductivity analysis results; (c) Elastic parameter results obtained from first-principles calculations.

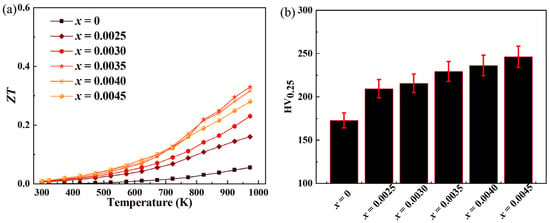

In Ta-doped indium oxide materials, the significant improvement of ZT value as shown in Figure 7a increase in power factor and the optimized regulation of thermal conductivity, which is closely related to the modification of carrier transport properties and electronic structure. Ta doping achieves a continuous increase in carrier concentration through the electron doping effect: Ta5+ releases free electrons when substituting In3+, and the introduction of impurity levels reduces the electron excitation energy barrier, leading to a significant increase in carrier concentration. The enhancement of carrier concentration directly promotes a substantial increase in electrical conductivity. Although the absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient decreases due to the increase in carrier concentration, the growth rate of electrical conductivity far exceeds the decrease rate of the square of the Seebeck coefficient, ultimately achieving a significant improvement in power factor and providing core momentum for the growth of the ZT value. In addition, the impurity atoms and lattice distortions introduced by Ta doping can scatter thermal phonons, reduce the thermal conductivity, and further improve the ZT value. The leapfrog improvement of ZT value ultimately stems from the synergistic optimization of the increased power factor and reduced thermal conductivity. The significant improvement of power factor lays the foundation for the growth of ZT value, while the effective suppression of thermal conductivity amplifies this gain effect, making the ratio of (S2σT)/κ increase sharply from 0.055 to 0.329 (973 K), which is lower than 0.42 for V dop, but higher than 0.301 for Nb doping and 0.08 for Mo doping [15,22,23].

Figure 7.

(a) ZT value test results of In2O3 thermoelectric materials with different Ta doping contents; (b) Corresponding Vickers hardness test results.

In Ta-doped indium oxide thermoelectric materials, the significant improvement of Vickers hardness as shown in Figure 7b does not directly result from changes in electrical transport properties (such as power factor and electrical conductivity), but from the combined effects of crystal structure strengthening, chemical bond modification, and defect regulation induced by Ta doping, with an indirect correlation to the optimization of electronic structure. From the perspective of crystal structure, the ionic radius of Ta5+ (0.064 nm) differs from that of In3+ (0.080 nm). When Ta5+ substitutes for In3+ in the In2O3 lattice, local lattice distortion is induced. This distortion forms a “lattice stress field” that hinders the slip and movement of dislocations in the lattice, thereby enhancing the material’s resistance to plastic deformation and directly improving Vickers hardness. With the increase in doping concentration, the scope and intensity of lattice distortion gradually increase, leading to a more significant hardness enhancement effect.

The change in chemical bond characteristics is one of the core factors for hardness improvement. As a 5d transition metal element, Ta forms Ta-O bonds with O atoms that have significantly higher covalency than In-O bonds, along with higher bond energy and shorter bond length. The formation of strong covalent bonds enhances the bonding force between atoms, making the crystal structure more stable. A higher external force is required to break the interatomic bonds, resulting in a significant increase in Vickers hardness. Meanwhile, the strong interaction of Ta-O bonds inhibits the thermal vibration and diffusion of atoms, further strengthening the mechanical stability of the material. In addition, the impurity atoms and lattice defects introduced by Ta doping form a “dispersion strengthening” effect. Ta atoms are uniformly distributed in the lattice, equivalent to introducing a large number of tiny “strengthening particles” into the In2O3 matrix. These particles hinder grain boundary migration and dislocation movement, further improving the material’s hardness. The enhancement of density of states near the Fermi level reflects an increase in electron cloud overlap, indirectly indicating strengthened interatomic interactions and providing electronic structure support for hardness improvement. Ta doping significantly improves the Vickers hardness of indium oxide materials through lattice distortion strengthening, formation of strong covalent bonds, and dispersion strengthening effect. Although this change has no direct causal relationship with the optimization of electrical transport properties, both originate from the regulation of the material’s microstructure and electronic state by Ta doping, demonstrating the important role of doping modification in synchronously improving the functional characteristics and mechanical properties of thermoelectric materials.

3. Experimental Part

High-purity indium oxide (In2O3) and tantalum pentoxide (Ta2O5) powders were chosen as the initial precursors. To guarantee a uniform mixture, these raw powders underwent a pre-treatment procedure. The synthesis of Ta-doped In2O3 powder was achieved via mechanical alloying utilizing a planetary ball mill. Precisely weighed quantities of In2O3 and Ta2O5, calculated to attain the desired nominal molar doping percentage of Ta, were blended meticulously. This powder mixture was then transferred into hardened steel containers, accompanied by appropriate grinding media. Put the weighed powder into a ball milling tank for 10 h with the speed of 450 rpm and the ball/material ratio of 20:1, then add anhydrous ethanol, ball milling with a planetary ball mill(QM-2SP12, Nanjing University Instrument Factory, Nanjing, China) for 1 h with the speed of 300 rpm, and then dry the obtained powder for more than 48 h at the temperature of 373 K. Then place the obtained powder into a quartz tube, fill it with argon gas for protection, and seal it. Put it into a muffle furnace and calcine at a high temperature of 1473 K for 8 h. Crush the obtained sample and then perform discharge plasma sintering at a temperature of 1273 K with 30 min of insulation and a pressure of 60 MPa. For the SPS process, the pellets were carefully positioned within specialized graphite molds. The entire sintering cycle was executed under a continuous flow of inert argon gas to maintain sample purity and minimize atmospheric contamination. Specific SPS conditions, such as sintering temperature, applied pressure, and dwelling duration, are consistent with those detailed in prior work [27]. Phase identification and structural analysis of the sintered samples were conducted by acquiring X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns. A diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source was used for this purpose, enabling the detection of phase constituents and assessment of potential lattice modifications induced by the incorporation of Ta dopants. The electronic transport characteristics, namely the electrical conductivity and the Seebeck coefficient, were evaluated across a designated temperature span. These measurements were performed employing a standardized commercial apparatus designed for assessing thermoelectric properties. The thermal conductivity (κ) of the sintered specimens was derived by applying the laser flash technique. This method directly measures the thermal diffusivity. The obtained diffusivity values were subsequently combined with experimentally determined sample density and specific heat capacity data to compute the final thermal conductivity value. In addition to the experimental work, computational studies based on density functional theory (DFT) were carried out. These calculations focused on simulating the electronic band structure and the density of states for Ta-doped In2O3. The primary objective of this theoretical modeling was to gain deeper insights into how Ta doping influences critical parameters such as charge carrier concentration and the ensuing electronic transport behavior. A diffractometer is used to characterize the phase structure of the material, and the equipment is a Bruker AXS D8 diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The diffraction analysis adopts Cu and rays with a wavelength of 1.5406 Å. Nickel plates were used as the substrate on the XRD sample stage with a diffraction angle range of 10–80°, a step size of 0.02°, a tube current of 20 mA, and a tube voltage of 40 kV. The electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient were tested using an electrical performance tester (ZEM-3, ULVAC KIKO, Tokyo, Japan). The carrier concentration and mobility at room temperature were measured by the van der Pauw method using the Hall-effect measurement system (HMS-5500, Ekopia, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The volume density was measured by the Archimedes method. The relative densities were 97.13%, 97.26%, 97.22%, 97.35%, 97.23%, and 97.31% for x = 0, 0.0025, 0.0030, 0.0035, 0.0040, and 0.0045, respectively. The flash thermal conductivity tester used was LFA457 (Netzsch, Berlin, Germany), Germany, for thermal conductivity testing. And the specific heat capacity (Cp) was determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC 404C, Netzsch, Berlin, Germany) under an inert atmosphere. All the specimens were polished with two parallel planes and the plane close to the central part was utilized for Vickers hardness (HV) measurement, which was conducted on HV-10008 with a load of 25 g and a loading time of 15 s. Every sample was tested with 5 data points, and the average HV was used for characterizing mechanical properties. The uncertainty of the Vickers hardness is estimated to be within 5%. The uncertainty of the Seebeck coefficient and electrical conductivity measurements was 5%. The uncertainty of the thermal conductivity is estimated to be within 8%, considering the uncertainties regarding thermal diffusion coefficient, specific heat, and density. The combined uncertainty for all measurements involved in the calculation of ZT is less than 15%. The density functional calculation used here is the CASTEP software 8.0 package in the materials studio software 8.0, and the constructed 2 × 2 × 1 unit cell is calculated. The cut-off energy in plane wave expansion is 550 eV, the total energy is converged to less than 2.0 × 10−5 eV/atom. The maximum stress, maximum force were converged to less than 0.05 GPa and 0.3 eV/nm. The tolerance in the self-consistent field (SCF) calculation was set to 10−6 eV/atom.

4. Conclusions

Ta doping is an efficient modification strategy for In2O3 thermoelectric materials, realizing synchronous improvements in electrical transport, thermoelectric conversion efficiency, and mechanical properties via regulating crystal structure, electronic structure, and microdefects. In electrical transport, Ta5+ substituting In3+ releases free electrons, and impurity levels reduce excitation barriers, continuously increasing carrier concentration. At high doping concentrations, lattice relaxation and impurity band formation alleviate scattering, leading to a “decrease-then-increase” mobility trend and significant conductivity enhancement. Despite a reduced Seebeck coefficient absolute value, conductivity growth outpaces the square of Seebeck coefficient attenuation, boosting the power factor sharply from 1.83 to 5.26. Enhanced Fermi-level density of states optimizes carrier saturation and transport efficiency while strengthening interatomic interactions. For thermoelectric efficiency, Ta doping achieves a ZT value leap from 0.055 to 0.329 (973 K) via the “power factor enhancement-thermal conductivity regulation” synergy: improved power factor provides core momentum, and lattice distortion/impurity scattering inhibits lattice thermal conductivity. In mechanical properties, Ta doping enhances Vickers hardness through multiple mechanisms: lattice distortion from ionic radius differences hinders dislocation movement, higher Ta-O bond covalency strengthens interatomic forces, and uniformly distributed Ta atoms form dispersion strengthening particles. These improvements originate from the same doping mechanism, realizing synchronous enhancement of functional characteristics and structural stability. Ta doping breaks traditional property trade-off bottlenecks via synergistic regulation of multiple parameters, with further optimization of doping concentration, microstructure, and composite systems promising to promote practical applications in green energy conversion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; Methodology, Y.Z., Z.Y., T.T. and S.Y.; Software, J.Z. (Jiang Zhu), Y.Z., T.T. and S.Y.; Validation, J.Z. (Jie Zhang), T.T. and S.Y.; Formal analysis, J.Z. (Jiang Zhu), J.Z. (Jie Zhang), W.L., T.T. and S.Y.; Investigation, B.F., Z.Y. and T.X.; Resources, B.F., Z.Y., W.L. and R.R.; Data curation, Z.Y., W.L. and R.R.; Writing—original draft, J.Z. (Jiang Zhu), J.Z. (Jie Zhang), B.F. and T.X.; Writing—review & editing, J.Z. (Jiang Zhu), J.Z. (Jie Zhang), B.F. and T.X.; Visualization, X.Z., T.X. and W.L.; Supervision, X.Z., T.X. and R.R.; Project administration, J.Z. (Jiang Zhu), J.Z. (Jie Zhang), X.Z., T.X. and R.R.; Funding acquisition, J.Z. (Jie Zhang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work is funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province [2021CFB009], Doctoral Startup Fund of Hubei University of Science and Technology [BK202039] Wuhan Donghu College Youth Fund Project [2025dhzk001], the guiding project of Hubei Province in 2022 [B2022313], the Double Hundred Project of Hubei University of Science and Technology in 2023, the Project of Hubei Engineering University of Teaching Research [Grant No. JY2024032], Ministry of Education University-Industry Cooperation Collaborative Education Project [2409025501], College Students, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program [DC2024031, DC2024032], the Sichuan Key Laboratory of Smart Grids [2023-IEPGKLSP- KFYB04]; the Hubei Provincial Key Laboratory for Operation and Control of Cascaded Hydropower Stations [2023KJX02]; the Doctoral Initiation Fund Project of Hubei University of Science and Technology [BK202335]; the Research on Monitoring System Based on Gear Transmission Vibration Signals [2025HX026]; the Research and development of environmentally friendly coating surface gloss powder [2024HX161]; the Research Fund for the Key Laboratory of Geological Hazards in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area [2023KDZ08]; the Guiding Project of the Scientific Research Plan of the Hubei Provincial Department of Education in 2024 [B2024159] and the Science and Technology Talents Serving Enterprises Project of the Hubei Provincial Department of Science and Technology [2025DJB057], The APC was funded by [2025dhzk001] and [BK202039].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Bo Feng, Zhiwen Yang and Tongqiang Xiong were employed by the company Hubei Xiangcheng Intelligent Electromechanical Research Institute Co., Ltd. Author Bo Feng was employed by the company Hubei MAGNIFICENT New Material Technology Co., Ltd. Author Bo Feng was employed by the company Jiangsu MAGNIFICENT New Material Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Dong, C.; Shi, Y.; Li, Q. An analysis on comprehensive influences of thermoelectric power generation based on waste heat recovery. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 44, 102867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araiz, M.; Casi, Á.; Catalán, L. Prospects of waste-heat recovery from a real industry using thermoelectric generators: Economic and power output analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.A.; Velkin, V.I.; Praveenkumar, S. Design and implementation of a thermoelectric power generation panel utilizing waste heat based on solar energy. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2022, 12, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Hooshmand Zaferani, S.; Jafarian, M.; Vashaee, D. Thermal management systems and waste heat recycling by thermoelectric generators—An overview. Energies 2021, 14, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, X. Experimental investigation of a novel heat pipe thermoelectric generator for waste heat recovery and electricity generation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 7450–7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Huang, T.H.; Augusto, G.L. Power generation and thermal stress characterization of thermoelectric modules with different unileg couples by recovering vehicle waste heat. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 375, 133987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Singh, S.K.; Hazra, P. The quest for high-efficiency thermoelectric generators for extracting electricity from waste heat. JOM 2021, 73, 4070–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawasam, L.S.; Jayasena, A.S.; Afnan, M.M.M. Waste heat recovery from thermo-electric generators (TEGs). Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, R.; Fayaz, M.; Ayoub, N. Oxide thermoelectric materials: A review of emerging strategies for efficient waste heat recovery. J. Power Sources 2025, 654, 237806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funahashi, R. Waste heat recovery using thermoelectric oxide materials. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2011, 3, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Chen, B. Two-stage thermoelectric generators for waste heat recovery from solid oxide fuel cells. Energy 2017, 132, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtaki, M.; Ogura, D.; Eguchi, K. High-temperature thermoelectric properties of In2O3-based mixed oxides and their applicability to thermoelectric power generation. J. Mater. Chem. 1994, 4, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotcenkov, G.; Brinzari, V.; Ham, M.H. In2O3-based thermoelectric materials: The state of the art and the role of surface state in the improvement of the efficiency of thermoelectric conversion. Crystals 2018, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.L.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.H. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of In2O3-based ceramics via nanostructuring and point defect engineering. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klich, W.; Ohtaki, M. Thermoelectric properties of Mo-doped bulk In2O3 and prediction of its maximum ZT. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 18116–18121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotcenkov, G.; Brinzari, V.; Cho, B.K. In2O3-based multicomponent metal oxide films and their prospects for thermoelectric applications. Solid State Sci. 2016, 52, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.L.; Zou, J.; Chen, Z.G. Advanced thermoelectric design: From materials and structures to devices. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7399–7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, P.; Rajasekar, M. Recent trends and future perspectives of thermoelectric materials and their applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 21706–21744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, P.; Villoro, R.B.; Bahrami, A.; Wilkens, L.; Reith, H.; Mattlat, D.A.; Pacheco, V.; Scheu, C.; Zhang, S.; Nielsch, K.; et al. Performance Degradation and Protective Effects of Atomic Layer Deposition for Mg-based Thermoelectric Modules. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2406473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, H.; Niu, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Rong, M. Soldering Pressure Effect on Lifetime of Thermoelectric Modules under Thermal Cycling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 27821–27830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsubara, Y.; Ishibe, T.; Kozuki, S. Non-parabolic Band Effect of ZnO Enhanced by Hybridization with Complex Point Defect Donors for Boosting Thermoelectric Conversion. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2025, 17, 46276–46284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Hussain, M.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, R.; Lin, Y.-H.; Nan, C.-W. Thermoelectric performance enhancement of vanadium doped n-type In2O3 ceramics via carrier engineering and phonon suppression. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 3, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Feng, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Tang, T.; Ruan, R.; Jin, P.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, H. The Effect of Nb Doping on the Thermoelectric Properties of Indium Oxide. Inorganics 2025, 13, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gurunathan, R.; Fu, C. Thermoelectric transport effects beyond single parabolic band and acoustic phonon scattering. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 734–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Z.; Liu, W.D.; Mao, Y. Decoupling carrier-phonon scattering boosts the thermoelectric performance of n-type GeTe-based materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ni, J. Strong anharmonic phonon scattering and superior thermoelectric properties of Li2NaBi. Mater. Today Phys. 2023, 31, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Luo, X.; She, X.; An, Q.; Peng, Y.; Cai, G.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Feng, B. Study on the physical mechanism of thermoelectric transport on the properties of ZnO ceramics. Res. Phys. 2023, 54, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.