Preparation of Fe3O4/P(U-AM-ChCl) Composite Hydrogel and Study on Its Mechanical and Adsorption Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Analysis

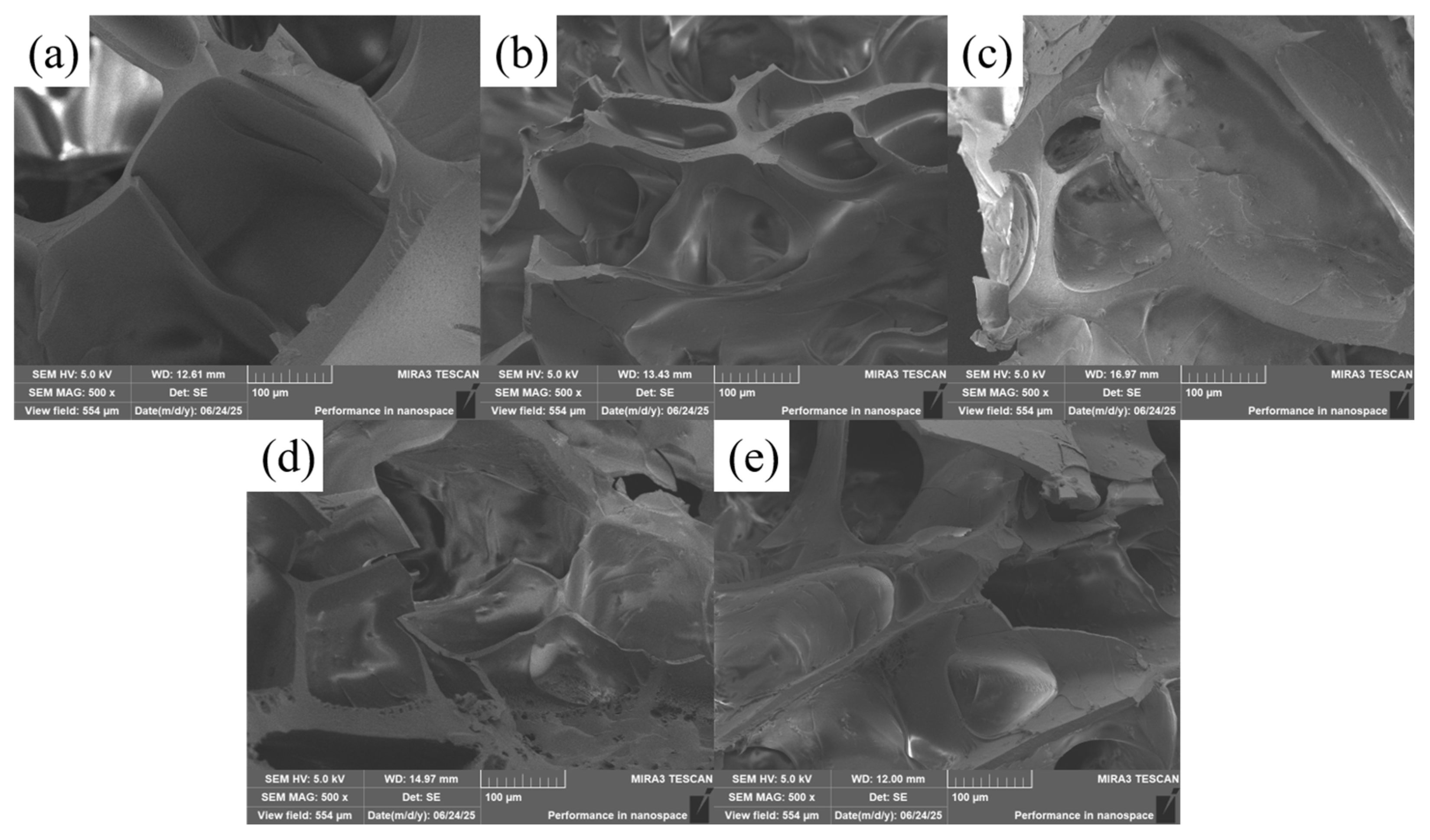

2.1. Analysis of the Microscopic Morphology of Composite Hydrogels

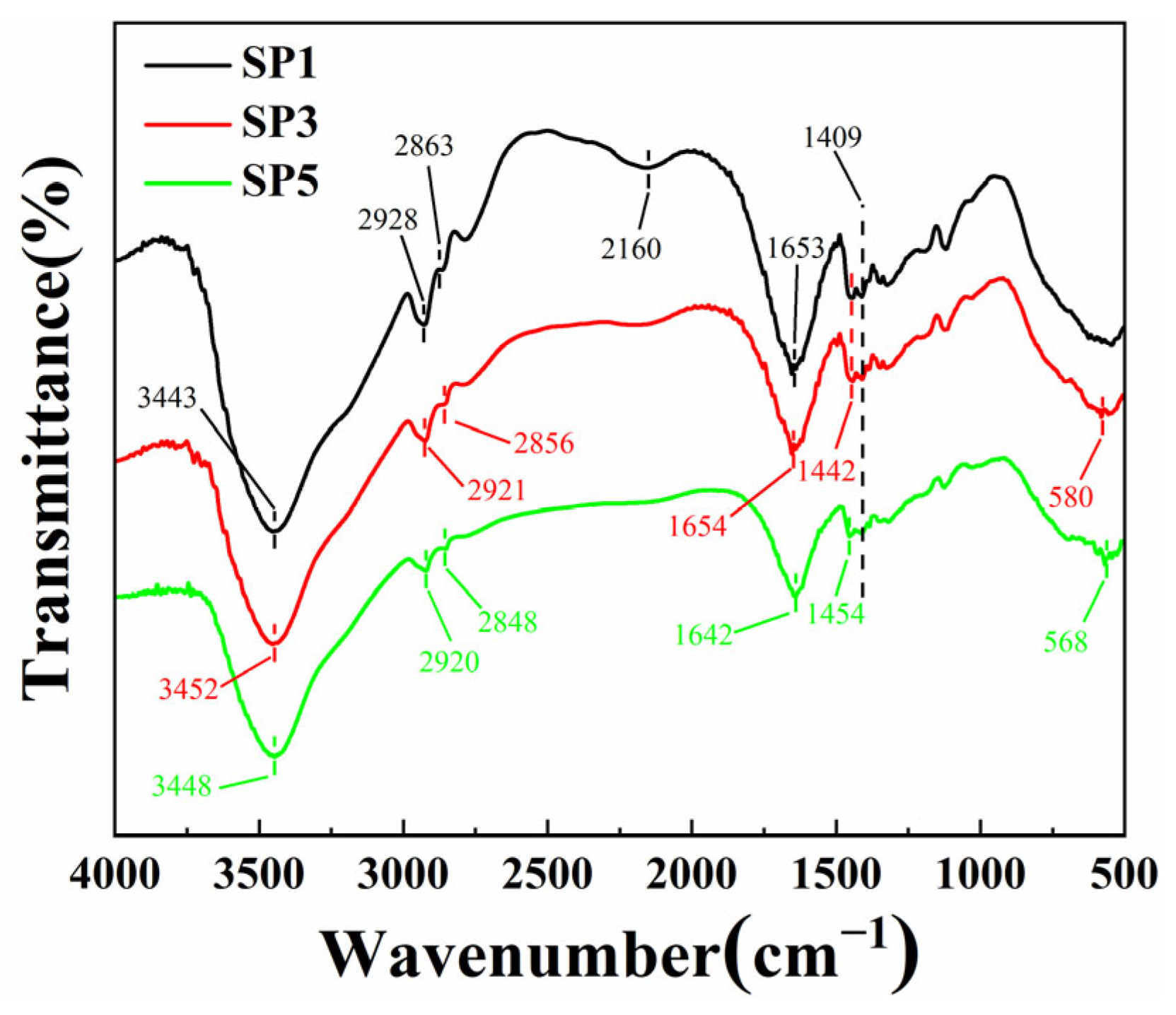

2.2. FTIR Spectra of Composite Hydrogel

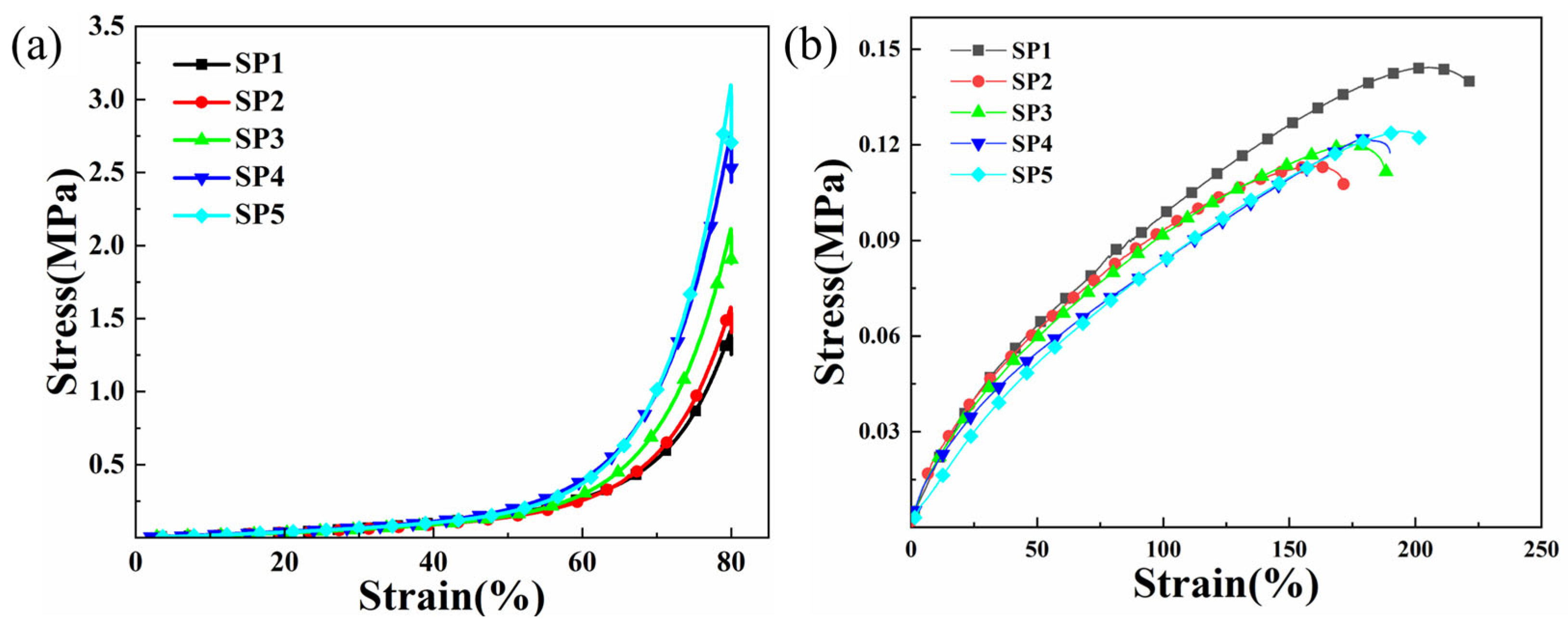

2.3. Mechanical Properties of Composite Hydrogels

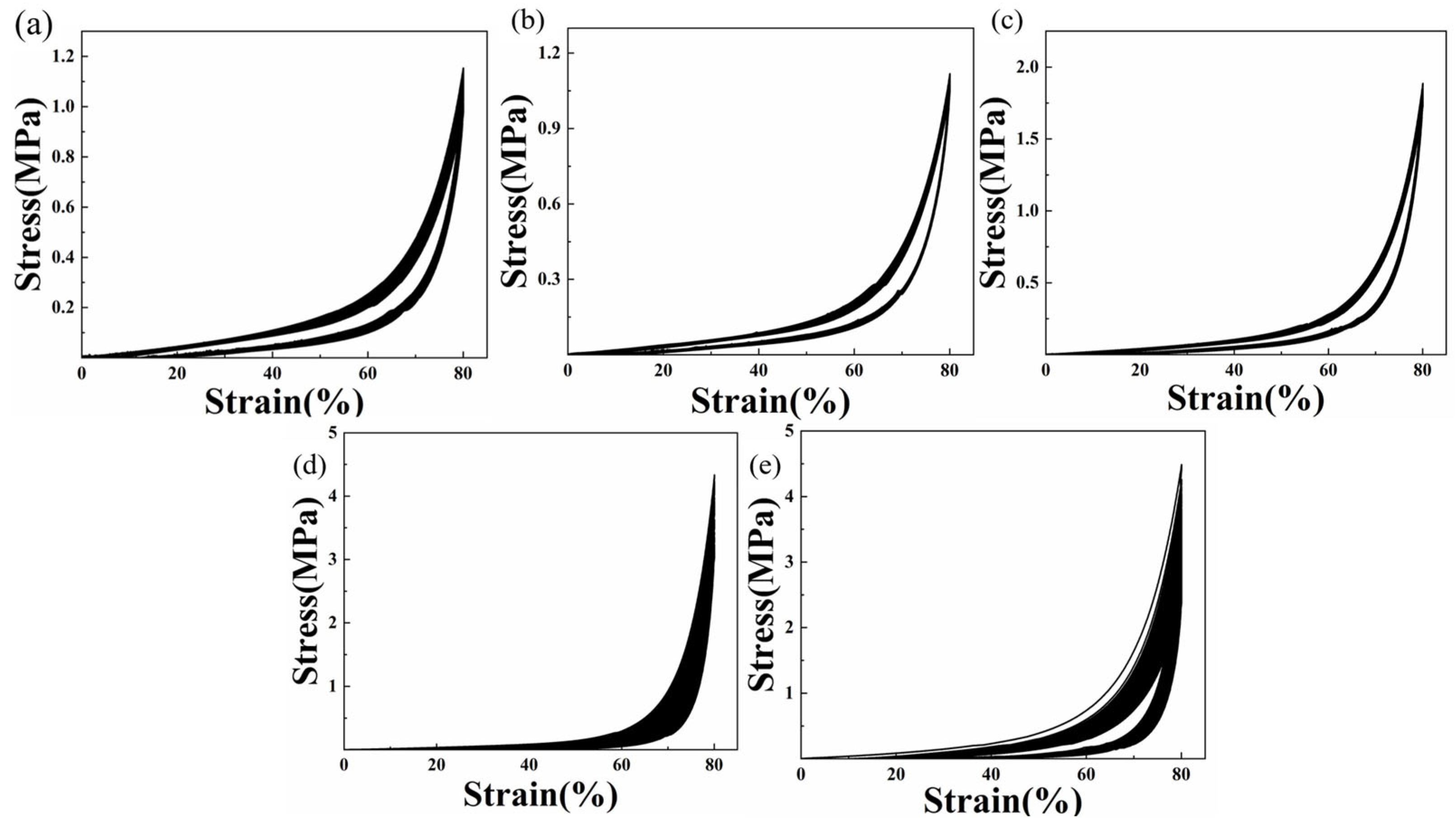

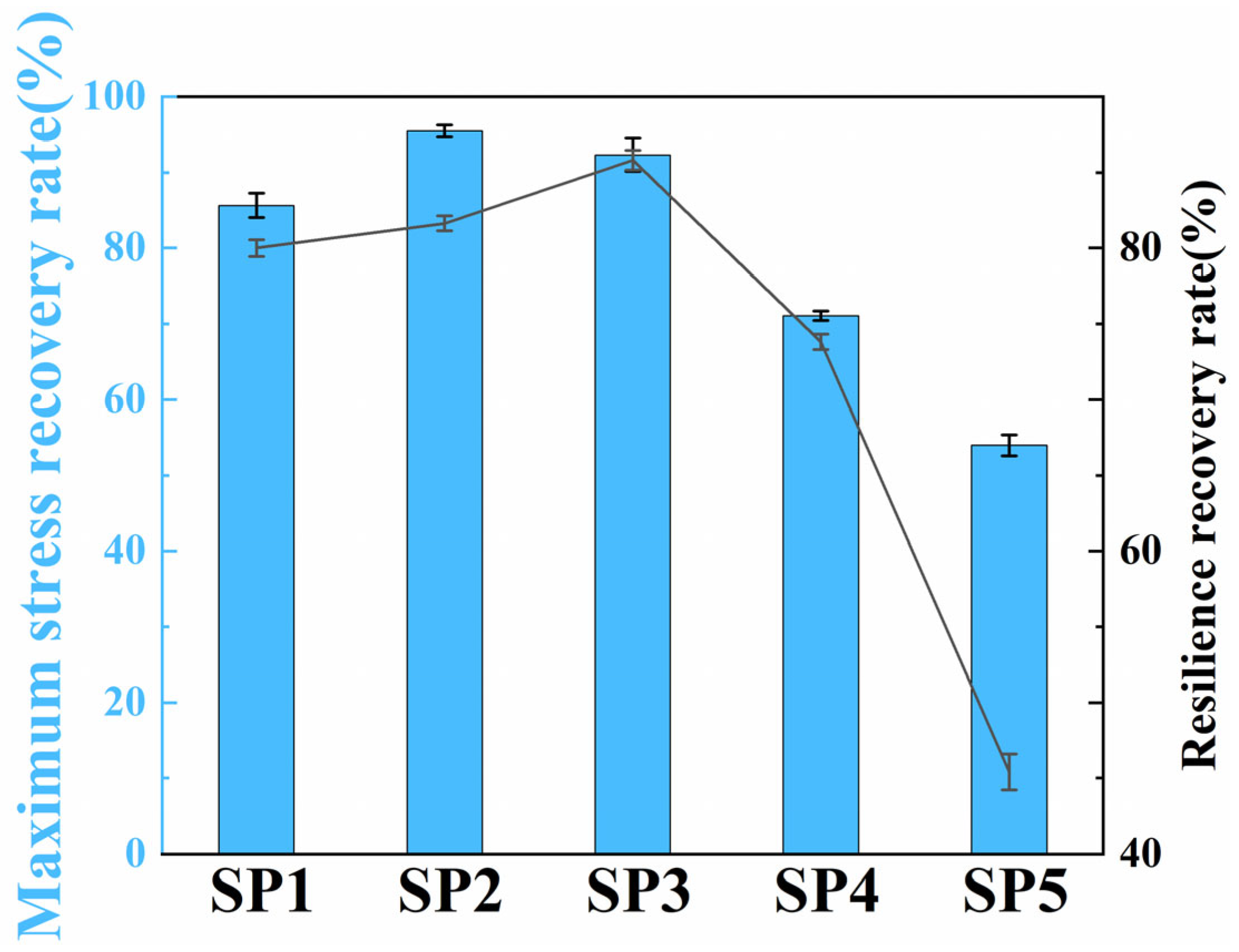

2.4. Fatigue Resistance of Composite Hydrogels

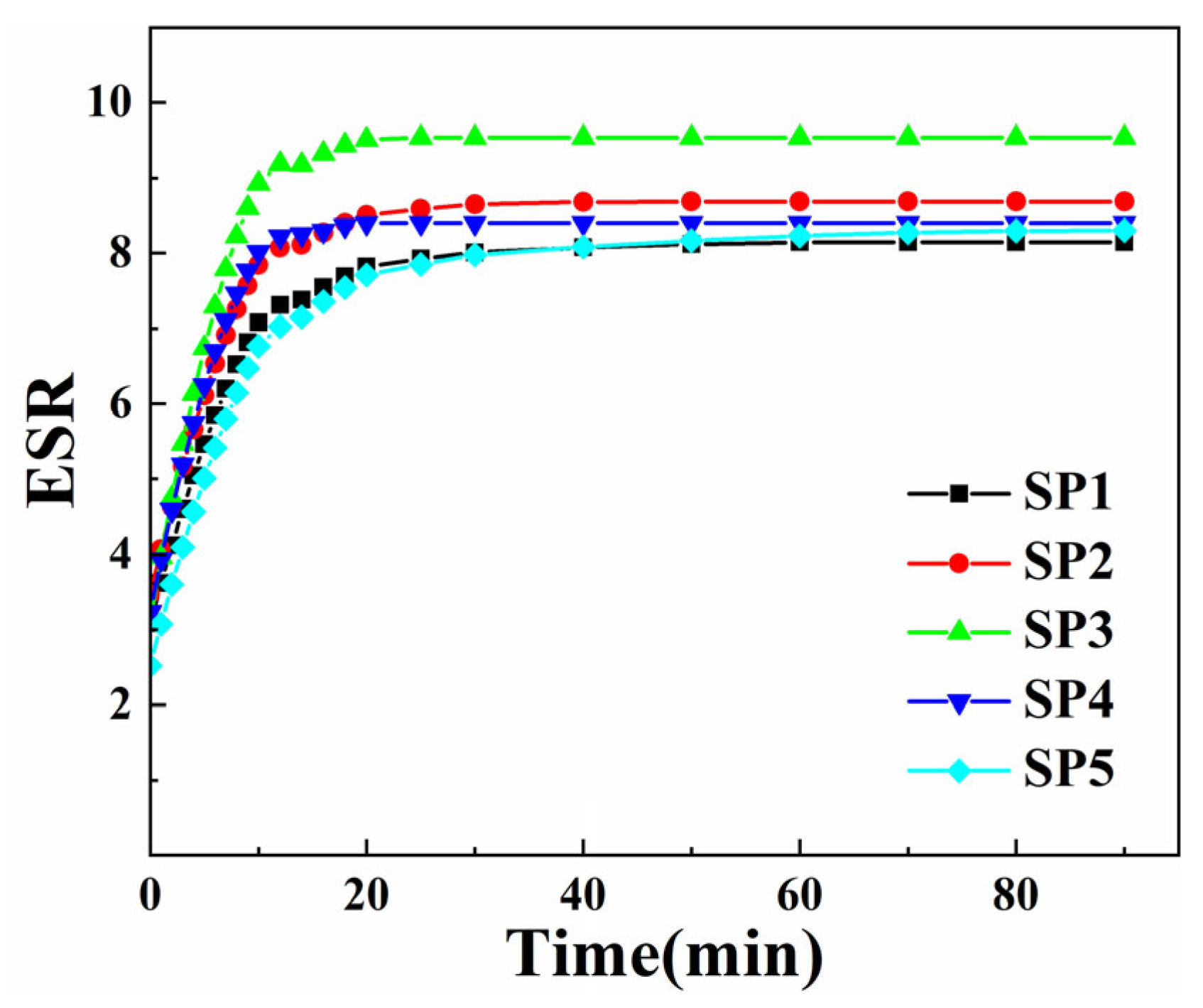

2.5. Swelling Performance of Hydrogel

2.5.1. Swelling Properties of Composite Hydrogels

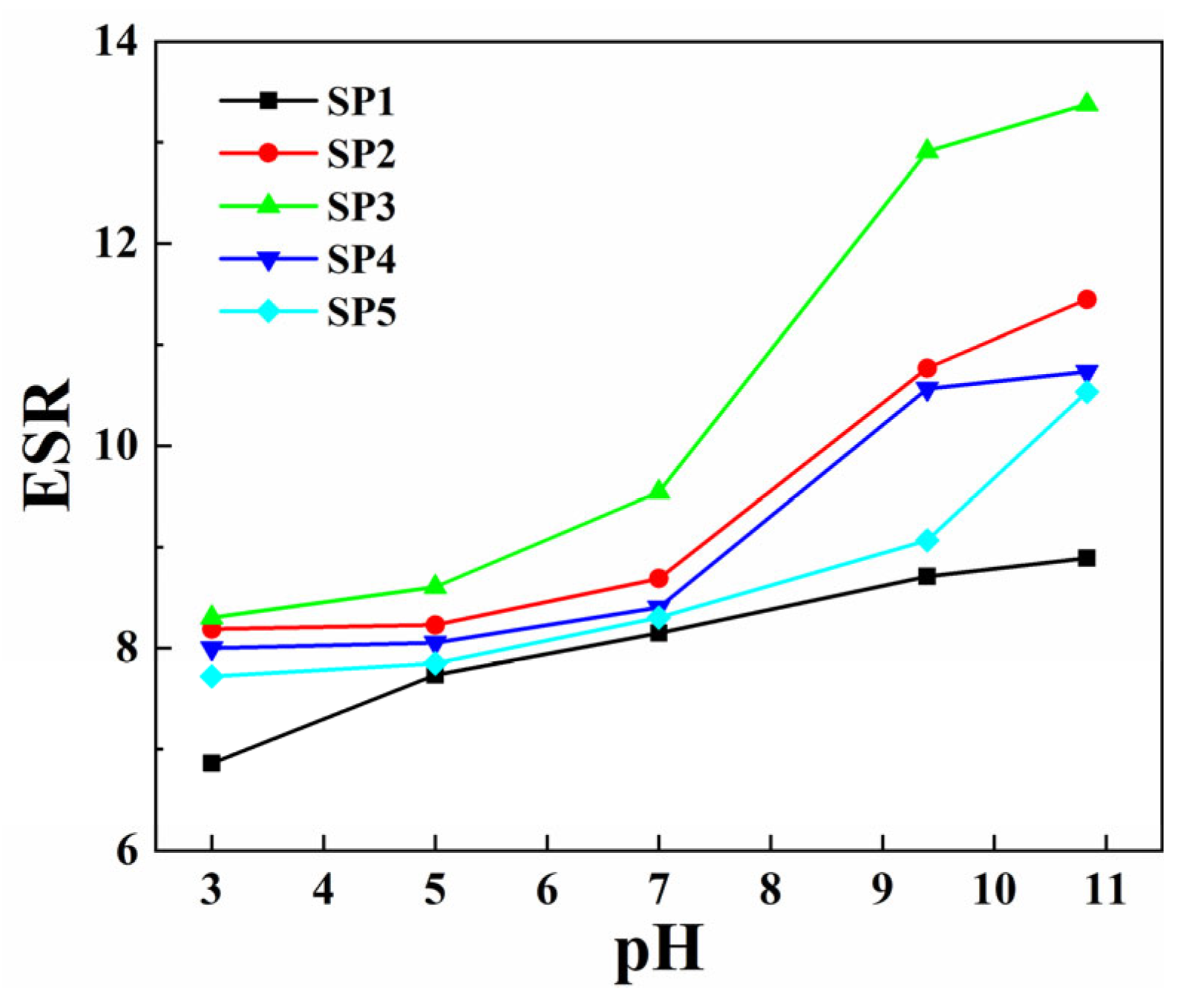

2.5.2. Swelling Properties of Composite Hydrogel in Different pH Environments

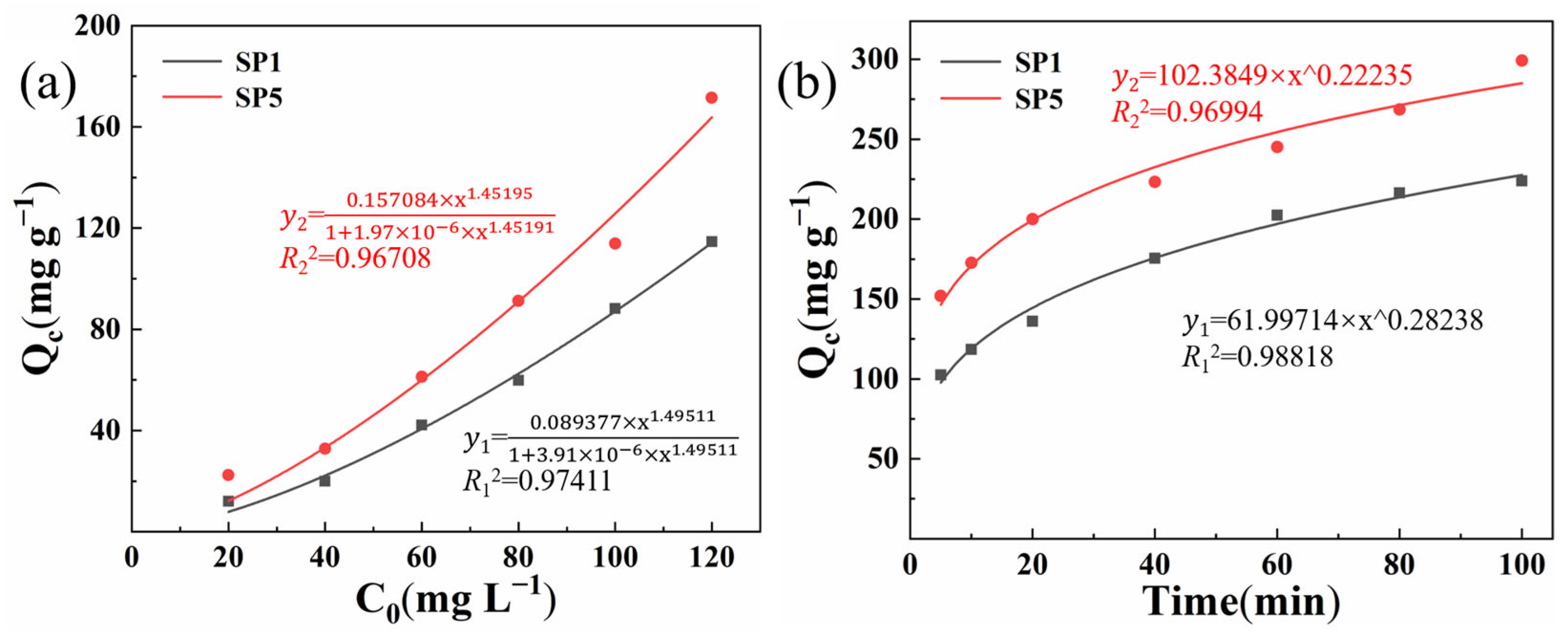

2.6. Adsorption Properties of Composite Hydrogel

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

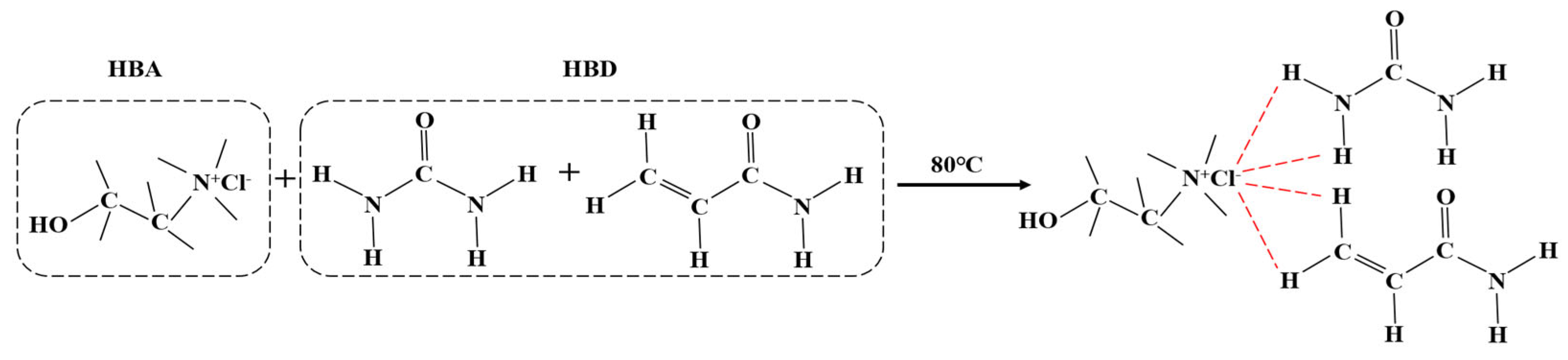

3.2. Preparation of DES

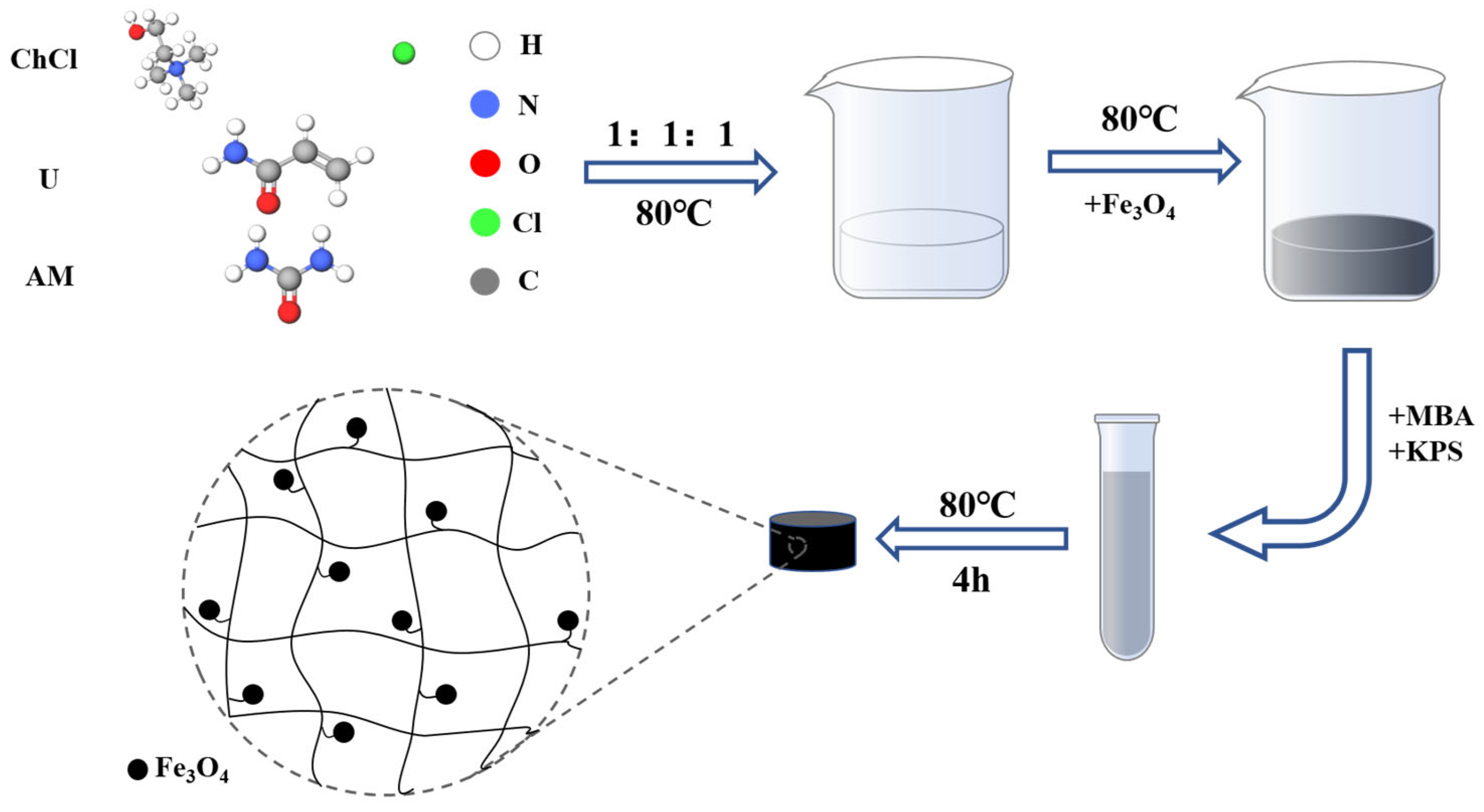

3.3. Preparation of Hydrogels by SP

3.4. Characterization of Composite Hydrogels

3.5. Performance Testing of Composite Hydrogel

3.5.1. Mechanical Testing of Hydrogel

3.5.2. Swelling Test of Hydrogel

3.5.3. Fatigue Resistance Test of Hydrogel

3.5.4. Adsorption Performance Testing of Hydrogel

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| U | Urea |

| AM | Acrylamide |

| ChCl | Choline chloride |

| MBA | N,N’-methylenebisacrylamide |

| KPS | Potassium persulfate |

| DES | Deep eutectic solvent |

| SP | In situ polymerization |

| ESR | Equilibrium swelling ratio |

References

- Yazdi, M.K.; Vatanpour, V.; Taghizadeh, A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Ganjali, M.R.; Munir, M.T.; Habibzadeh, S.; Saeb, M.R.; Ghaedi, M. Hydrogel membranes: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 114, 111023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, A.J.; de Alba, E. A Simple Method to Determine Diffusion Coefficients in Soft Hydrogels for Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 10852–10865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; Bonicelli, P.G.; Ripa, C.; Poni, S. Soil incorporation of Superabsorbent Hydrogels to counteract water scarcity: Modelling tree physiological and biochemical response. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 223, 109775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennakesavan, G.; Mostakhdemin, M.; Dkhar, L.K.; Seyfoddin, A.; Fatihhi, S.J. Acrylic acid/acrylamide based hydrogels and its properties—A review. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 180, 109308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoyo, A.H.; Wilson, L.D. A Review on the Design and Hydration Properties of Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels. Materials 2021, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Chen, Q.; Qin, H.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D.; Hua, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xu, J. A Temperature-Responsive Copolymer Hydrogel in Controlled Drug Delivery. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 6584–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Vermani, K.; Garg, S. Hydrogels: From controlled release to pH-responsive drug delivery. Drug Discov. Today 2002, 7, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Scheiger, J.M.; Levkin, P.A. Design and Applications of Photoresponsive Hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Lincoln, S.F.; Guo, X. Preparation of a poly(acrylic acid) based hydrogel with fast adsorption rate and high adsorption capacity for the removal of cationic dyes. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 21075–21085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Cao, X.; Lee, L.J. Design of a novel hydrogel-based intelligent system for controlled drug release. J. Control. Release 2004, 95, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, G.; Xue, L.; Dong, G.; Su, W.; Cui, M.J.; Wang, Z.G.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, X. Ultrasoft and Biocompatible Magnetic-Hydrogel-Based Strain Sensors for Wireless Passive Biomechanical Monitoring. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 21555–21564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelu, M.; Musuc, A.M.; Popa, M.; Calderon Moreno, J.M. Chitosan Hydrogels for Water Purification Applications. Gels 2023, 9, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.S. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Sun, M.; Bi, J.; Wang, S.; Guo, X.; Li, F.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y. Removal of ciprofloxacin by PAA-PAM hydrogel: Adsorption performance and mechanism studies. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 71, 107361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, R.; Milzi, L.; Gentile, F.S.; Pannico, M.; Musto, P.; Maiello, A.; Panunzi, B. A versatile pH-sensitive hydrogel based on a high-performance dye: Monitoring the freshness of milk and chicken meat. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 135, 106667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Lo, I.M.C. A holistic review of hydrogel applications in the adsorptive removal of aqueous pollutants: Recent progress, challenges, and perspectives. Water Res. 2016, 106, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, R.; Gao, D.; Wang, Z.; Qin, C.; Yang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, P. Enhanced Mechanical Strength of Metal Ion-Doped MXene-Based Double-Network Hydrogels for Highly Sensitive and Durable Flexible Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 51774–51784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, T.; Huang, J.; Guo, Z. Metal ion mediated conductive hydrogels with low hysteresis and high resilience. Mater. Today Phys. 2025, 51, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, F.; Lu, Q.; Liu, B.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y. Metal-ion-mediated hydrogels with thermo-responsiveness for smart windows. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 99, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Song, M.; Gu, J.; Xu, Z.; Xue, B.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y. A Highly Stretchable, Tough, Fast Self-Healing Hydrogel Based on Peptide–Metal Ion Coordination. Biomimetics 2019, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chakravarthy, R.D.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lin, H.-C.; Yeh, M.-Y. Effect of Metal Ions on the Conductivity, Self-Healing, and Mechanical Properties of Alginate/Polyacrylamide Hydrogels. Materials 2025, 18, 3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Weng, L.; Guan, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhao, W. Preparation of magnetic-oriented electronic packaging composite materials with improved thermal conductivity and insulating properties by filling magnetic BN@Fe3O4 core-shell particles into epoxy. High Volt. 2025, 10, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katheria, A.; Das, P.; Nayak, J.; Roy, B.; Pal, A.; Biswas, S.; Das, N.C. MXene and Fe3O4 decorated g-C3N4 incorporated high flexible hybrid polymer composite for enhanced electrical conductivity, EMI shielding and thermal conductivity. Next Mater. 2025, 6, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, W.; Li, Z.; Qu, L.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yan, T.; Zhou, Q. Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Modified Hydroxyapatite Whisker: A Novel Framework with Superior Osteogenic Efficacy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e09715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Nian, G.; Liang, X.; Wu, L.; Yin, T.; Lu, H.; Qu, S.; Yang, W. Adhesive Tough Magnetic Hydrogels with High Fe3O4 Content. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 10292–10300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchi, D.P.; Cazetta, A.L.; Canesin, E.A.; Almeida, V.C.; Bonafé, E.G.; Kipper, M.J.; Martins, A.F. New magnetic chitosan/alginate/Fe3O4@SiO2 hydrogel composites applied for removal of Pb(II) ions from aqueous systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.-H.; Li, X.-N.; Wu, X.-G.; Qin, Y.-X.; Chen, W.-Y. Fe3+, NIR light and thermal responsive triple network composite hydrogel with multi-shape memory effect. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 206, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, R.; He, Z.; Xue, F.; Ju, S. Construction of robust H2TiO3@PAM hydrogel ion-sieve via in-situ polymerization for Li+ adsorption. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 56, 105697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Si, D.; Zhou, H.; Yang, M.; Wang, X. An In situ Forming Hydrogel Based on Photo-Induced Hydrogen Bonding. Macromol. Res. 2020, 28, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, B.; Tang, J.; Zhou, M.; Wu, A.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y. Preparation of acrylamide-urea composite hydrogels based on deep eutectic solvents and their self-healing and pressure-sensitive properties. J. Porous Mater. 2025, 32, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-A.; Yeom, J.; Hwang, B.W.; Hoffman, A.S.; Hahn, S.K. In situ-forming injectable hydrogels for regenerative medicine. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 1973–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Greaves, T.L.; Warr, G.G.; Atkin, R. Mixing cations with different alkyl chain lengths markedly depresses the melting point in deep eutectic solvents formed from alkylammonium bromide salts and urea. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 2375–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Dai, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Wen, J.; Huang, G.; Xu, S. Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents for next-generation lithium batteries: Safer and greener. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 146, 101338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Hou, M.; Guo, X.; Cao, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, W.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shi, H. Recent progress in deep eutectic solvent(DES) fractionation of lignocellulosic components: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 192, 114243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Morales, J.D.; Gutiérrez, M.C.; Sanchez, I.C.; Luna-Bárcenas, G.; del Monte, F. Frontal polymerizations carried out in deep-eutectic mixtures providing both the monomers and the polymerization medium. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 5328–5330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ke, Z.; Qi, S.; Dai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S.; Chen, W. Innovative development of deep eutectic solvent based supramolecular hydrogel as excellent surface functional material of porous silica gel with favorable chromatographic performance. Microchem. J. 2024, 207, 112247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larriba, M.; Ayuso, M.; Navarro, P.; Delgado-Mellado, N.; Gonzalez-Miquel, M.; García, J.; Rodríguez, F. Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Dearomatization of Gasolines. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; He, C.; Zhang, L.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X. Freeze-resistant, rapidly polymerizable, ionic conductive hydrogel induced by Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) after lignocellulose pretreatment for flexible sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Peng, W.; Chen, J.; Yu, C.; Bo, R.; Liu, M.; Li, J. Multifunctional hydrogel based on polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan/metal polyphenols for facilitating acute and infected wound healing. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 29, 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, I.N.; Gun’ko, V.M.; Turov, V.V.; Dainiak, M.; Phillips, G.J.; Galaev, I.Y.; Mikhalovsky, S.V. Porous structure and water state in cross-linked polymer and protein cryo-hydrogels. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 4276–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, A. Water- and Fertilizer-Integrated Hydrogel Derived from the Polymerization of Acrylic Acid and Urea as a Slow-Release N Fertilizer and Water Retention in Agriculture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5762–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Miao, C.; Duan, Q.; Jiang, S.; Liu, H.; Ma, L.; Li, Z.; Bao, X.; Lan, B.; Chen, L.; et al. Developing slow release fertilizer through in-situ radiation-synthesis of urea-embedded starch-based hydrogels. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 191, 115971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, D.; Yang, W.; Song, Y. Compressive mechanical properties and microstructure of PVA–HA hydrogels for cartilage repair. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 20166–20172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Tang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, X.; Lin, L. A self-healing water-dissolvable and stretchable cellulose-hydrogel for strain sensor. Cellulose 2021, 29, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, D.; Singh, R.P. Characterisation of carboxymethyl cellulose and polyacrylamide graft copolymer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 57, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wang, J.; Teng, F.; Shao, Z.; Huang, X. Zr (IV)-crosslinked polyacrylamide/polyanionic cellulose composite hydrogels with high strength and unique acid resistance. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2019, 57, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, K.P.; Fukamachi, C.R.B.; Wypych, F.; Mangrich, A.S. Dehydrated halloysite intercalated mechanochemically with urea: Thermal behavior and structural aspects. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 338, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, A.M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.E.; El-Sayed, E.S.A.; Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; Abd El-Hakim, A.A.; Kamel, S.; Turky, G. Morphological, electrical & antibacterial properties of trilayered Cs/PAA/PPy bionanocomposites hydrogel based on Fe3O4-NPs. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruksawan, S.; Lim, J.W.R.; Lee, Y.L.; Lin, Z.; Chee, H.L.; Chong, Y.T.; Chi, H.; Wang, F. Enhancing hydrogel toughness by uniform cross-linking using modified polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane. Commun. Mater. 2023, 4, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, S.J.; Anseth, K.S.; Lee, D.A.; Bader, D.L. Crosslinking density influences the morphology of chondrocytes photoencapsulated in PEG hydrogels during the application of compressive strain. J. Orthop. Res. 2004, 22, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Xie, S.; Lu, D.; Liu, D.; Xu, H.; Wu, P.; Si, B.; Zhang, C.; Lin, X.; et al. Eco-Friendly Fabrication of PVA/Chitosan Hydrogel With Superior Mechanical Strength and Antibacterial Efficacy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 143, e58063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Dong, L.; Wu, J.; Shi, Y.; Feng, X.; Lu, X.; Zhu, J.; Mu, L. Versatile Ionic Gel Driven by Dual Hydrogen Bond Networks: Toward Advanced Lubrication and Self-Healing. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 5932–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Abeykoon, C.; Karim, N. Investigation into the effects of fillers in polymer processing. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2021, 4, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwenberg, C.; Balk, M.; Wischke, C.; Behl, M.; Lendlein, A. Shape-Memory Hydrogels: Evolution of Structural Principles To Enable Shape Switching of Hydrophilic Polymer Networks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Xie, Z.; Xu, J.; Weng, Y.; Guo, B.-H. Design of a self-healing cross-linked polyurea with dynamic cross-links based on disulfide bonds and hydrogen bonding. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 107, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Sun, X. The Influence of Carbon Black Dosage and Type on the Fatigue Failure Characteristics of Rubber Materials. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e56882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoychev, G.; Guiducci, L.; Turcaud, S.; Dunlop, J.W.C.; Ionov, L. Hole-Programmed Superfast Multistep Folding of Hydrogel Bilayers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 7733–7739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, R.; Saboury, A.; Javanbakht, S.; Foroutan, R.; Shaabani, A. Carboxymethylcellulose/polyacrylic acid/starch-modified Fe3O4 interpenetrating magnetic nanocomposite hydrogel beads as pH-sensitive carrier for oral anticancer drug delivery system. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 153, 110500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, F.; Wang, H.-S.; Lu, Y.-S.; Zhong, C.; Chu, L.-Q. Preparation, characterization and antibacterial applications of carboxymethyl chitosan/CuO nanocomposite hydrogels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tran, V.; Park, D.; Lee, Y.-C. Hydrogel applications for adsorption of contaminants in water and wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 24569–24599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humelnicu, D.; Dragan, E.S.; Ignat, M.; Dinu, M.V. A Comparative Study on Cu2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, Fe3+, and Cr3+ Metal Ions Removal from Industrial Wastewaters by Chitosan-Based Composite Cryogels. Molecules 2020, 25, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, F.; Ding, G.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Liu, P.; Qi, X.; Ni, L. Synthesis of a novel ionic liquid modified copolymer hydrogel and its rapid removal of Cr (VI) from aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 455, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Identification | Chemical Group | Wavenumber (cm−1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | O-H stretching vibration of water molecules and N-H stretching vibration of urea molecules | 3700–3000 | [42] |

| 2 | Stretching vibration of the C-H group | SP1:2928, 2863 | [43,44] |

| SP3:2921, 2856 | |||

| SP5:2920, 2848 | |||

| 3 | C≡N stretching vibration | SP1:2160 | [48] |

| 4 | Amide I C=O stretching vibration | SP1:1653 | [45] |

| SP3:1654 | |||

| SP5:1642 | |||

| 5 | CH2 bending and twisting vibrations | SP1:1442, 1349 | [46] |

| SP3:1442, 1349 | |||

| SP5:1454, 1349 | |||

| 6 | Vibration of the -CONH2 group | 1409 | [47] |

| 7 | Fe-O stretching vibration | SP3:580 | [49] |

| SP5:568 |

| Samples | AM/U/ChCl (Molar Ratio) | KPS (wt%) | MBA (wt%) | Fe3O4 (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP1 | 1:1:1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 |

| SP2 | 1:1:1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| SP3 | 1:1:1 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 |

| SP4 | 1:1:1 | 1 | 0.8 | 2 |

| SP5 | 1:1:1 | 1 | 0.8 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, M.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y. Preparation of Fe3O4/P(U-AM-ChCl) Composite Hydrogel and Study on Its Mechanical and Adsorption Properties. Inorganics 2026, 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010005

Liu Y, Li J, Li B, Hu Z, Zhou M, Lv H, Wang Y. Preparation of Fe3O4/P(U-AM-ChCl) Composite Hydrogel and Study on Its Mechanical and Adsorption Properties. Inorganics. 2026; 14(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yuzuo, Jiawei Li, Bin Li, Zhigang Hu, Mengjing Zhou, Haoyu Lv, and Ying Wang. 2026. "Preparation of Fe3O4/P(U-AM-ChCl) Composite Hydrogel and Study on Its Mechanical and Adsorption Properties" Inorganics 14, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010005

APA StyleLiu, Y., Li, J., Li, B., Hu, Z., Zhou, M., Lv, H., & Wang, Y. (2026). Preparation of Fe3O4/P(U-AM-ChCl) Composite Hydrogel and Study on Its Mechanical and Adsorption Properties. Inorganics, 14(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010005