Abstract

Graph neural networks (GNNs) have rapidly matured into a unifying, end-to-end framework for energy-materials discovery. By operating directly on atomistic graphs, modern angle-aware and equivariant architectures achieve formation-energy errors near 10 meV atom−1, sub-0.1 V voltage predictions, and quantum-level force fidelity—enabling nanosecond molecular dynamics at classical cost. In this review, we provide an overview of the basic principles of GNNs, widely used datasets, and state-of-the-art architectures, including multi-GPU training, calibrated ensembles, and multimodal fusion with large language models, followed by a discussion of a wide range of recent applications of GNNs in the rapid screening of battery electrodes, solid electrolytes, perovskites, thermoelectrics, and heterogeneous catalysts.

1. Introduction

The global transition toward carbon-neutral energy technologies demands the rapid identification of materials that can store, convert, and harvest energy with unprecedented efficiency and stability. As a result, computational methods have emerged as essential tools for the design and discovery of new halide perovskite materials. Unfortunately, conventional density-functional-theory (DFT)-driven high-throughput screening scales poorly with the chemical complexity and configurational freedom of modern energy materials, leaving vast swaths of compositional space essentially unexplored. Machine learning (ML) is playing an increasingly pivotal role, significantly impacting tasks such as predicting material properties, accelerating computational simulations, designing novel structures, and revealing structure–property relationships.

Among the rapidly evolving classes of ML models, graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as a disruptive paradigm in computational materials science. By operating directly on atomic graphs—where nodes represent atoms and edges encode chemical bonds or interatomic interactions—GNNs eliminate the lossy feature engineering required by grid- or sequence-based models and learn hierarchical structure–property relationships through message passing and attention mechanisms [1]. Early crystal GNNs such as CGCNN and MEGNet already achieved sub-0.05 eV atom−1 errors for formation energies on Materials Project crystals [2,3], while recent angle-aware and equivariant architectures (e.g., ALIGNN, GemNet-OC, E2GNN) have pushed accuracy to the 10 meV scale and extended coverage to forces, stresses, long-range electrostatics, and even Hessians [1,4,5].

The GNN revolution of the application of energy materials has been catalyzed by two complementary trends. First, public mega datasets—from the more than 150,000 relaxed structures in the Materials Project [6] to the 260 million single-point calculations of the Open Catalyst (OC20/OC22/OCx24) benchmarks [7,8]—provide the labeled data needed to train deep models without over-fitting. Second, advances in high-performance computing (HPC) and distributed graph learning now allow billion-parameter GNNs to be optimized across multi-GPU clusters with near-linear speed-up, making million-structure corpora tractable for academic groups [9]. In parallel, multimodal fusion with large language models (LLMs) couples structural priors with textual synthesis knowledge, enabling closed-loop, autonomous laboratories that can propose, evaluate, and even execute experiments within days [10,11].

Technological breakthroughs in GNNs are rapidly accelerating materials discovery across key domains of energy materials: (i) battery electrodes and electrolytes, where GNN models now predict voltages, ionic conductivities and diffusion barriers with <0.1 V or <40 meV Å−1 error, enabling rapid triage of layered oxides, and solid electrolytes and multivalent hosts; (ii) solar-cell absorbers—from halide perovskites and organic donor–acceptor pairs to wide-gap oxides—where GNN models reach hybrid-functional band-gap accuracy while screening tens of thousands of candidates in minutes; (iii) thermoelectric materials, for which GNN models deliver reliable surrogates for power factor and lattice thermal conductivity across chalcogenides, half-Heuslers, and complex oxides; (iv) heterogeneous catalysts (electro-, thermo-, and photocatalysts), where GNN models predicting the force fields push the field from static adsorption-energy estimates toward nanosecond, micro-kinetically resolved reaction networks.

By contextualizing these domain-specific advances within a common methodological framework—covering embeddings, attention, HPC scaling, and LLM coupling—we aim to provide both a state-of-the-art snapshot and a forward-looking roadmap for researchers seeking to deploy GNNs in the accelerated discovery of next-generation energy materials. We conclude with an outlook on the pivotal challenges of overcoming data scarcity, capturing non-local physics, and ensuring robustness for autonomous discovery systems, emphasizing how advancements in foundational pre-training, hybrid architectures, and integrated uncertainty/safety frameworks will be critical to unlocking the full potential of GNNs in realizing a sustainable energy future.

2. Computational Tools

2.1. Basic Framework of GNN

Classical machine learning models, including fully connected and convolutional neural networks, depend on substantial feature engineering to process non-Euclidean data. This process, which is often lossy, necessitates reformatting the inherent structures into fixed-dimensional vectors, thereby potentially obscuring information that is topologically and relationally critical.

The core entities studied in chemistry and materials science—molecules, crystals, polymers—are intrinsically represented not as simple sequences or grid-like images, but as complex networks (graphs) composed of atoms (nodes) connected by chemical bonds/interactions (edges). This graph formalism precisely encodes topological information, including atomic connectivity, spatial configuration, and local chemical environments. The defining advantage of GNNs lies in their native ability to process graph-structured data. They directly ingest molecular or crystal structures as input graphs, eliminating the need for structure-disruptive preprocessing [12]. Some basic techniques of GNN include:

Node Embedding: GNNs learn a feature vector (embedding) for each atom (node). This embedding initially represents intrinsic atom properties (e.g., element type, charge, hybridization state) and is progressively enriched by aggregating information from the surrounding environment during message passing.

Edge Embedding: Chemical bonds or atomic interactions (edges) can similarly possess their own feature vectors (e.g., bond length, order, type).

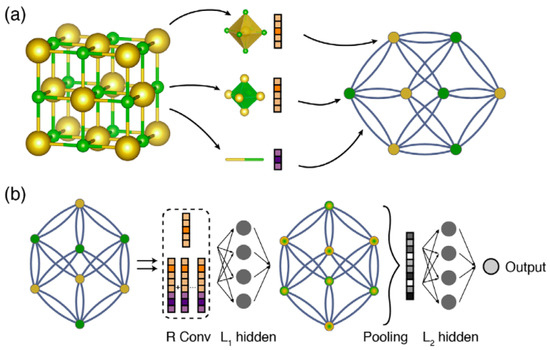

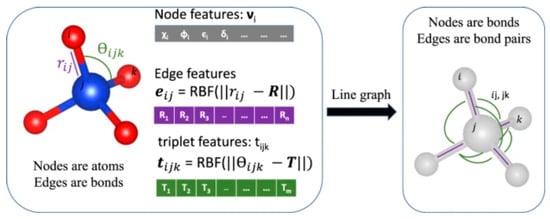

Figure 1a illustrates how a crystal structure is represented by a graph that encodes both atomic information and bonding interactions between atoms. Afterwards, using node and edge features in combination with the graph’s structure, GNNs can derive a node-level embedding of the graph, i.e., learned vectors representing each atom including its individual chemical environment. Such a technique is performed in the so-called message passing mechanism:

Message Passing Mechanism: This is the core operation of GNNs. It simulates the flow of information along edges within the graph. Each node aggregates “messages” from its neighboring nodes and connecting edges. These aggregated messages are then processed through learnable neural network layers to update the node’s embedding. This iterative process, typically performed over multiple steps (layers), allows the final embedding of each node to incorporate information about its extended chemical environment across multiple hops within the molecular/material structure.

Figure 1b shows how a message passing mechanism works. In message passing layers (R), atoms iteratively exchange information with bonded neighbors. Each layer updates atom states using messages from adjacent atoms and bonds. The L1 hidden layer refines the updated atom states capturing the local environment. Then, atom states are aggregated into a single vector representing the entire crystal in the pooling layer. L2 hidden layers then process the pooled crystal vector, and the output layer provides the target property prediction.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the GNN framework. (a) Construction of the crystal graph. (b) Structure of the message passing mechanism on the crystal graph. (Reproduced with permission from [2]).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the GNN framework. (a) Construction of the crystal graph. (b) Structure of the message passing mechanism on the crystal graph. (Reproduced with permission from [2]).

2.2. Advanced Technology of GNN

Classical ML models (e.g., fully connected neural networks, convolutional neural networks) often require extensive and potentially lossy feature engineering to handle such non-Euclidean data, forcing structural information into fixed-dimensional vectors, which can obscure critical topological and relational details. Early crystal GNNs such as CGCNN and MEGNet already achieved sub-0.05 eV atom−1 errors for formation energies on the Materials Project database [2,3]. Recent GNN architectures have further improved accuracy while also extending coverage to a wider range of applications (Figure 2). These advances are largely due to several key GNN advancements, including the following:

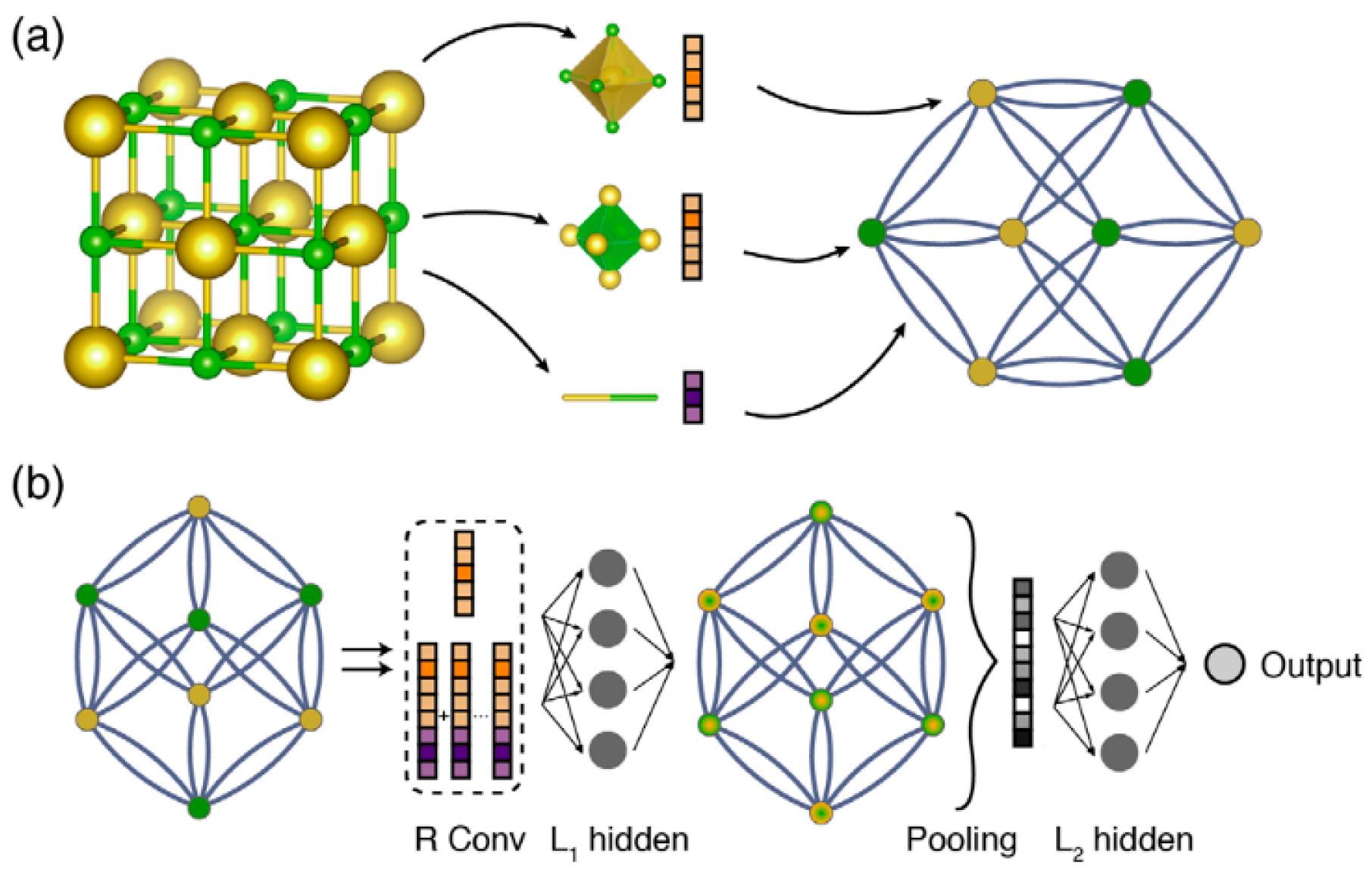

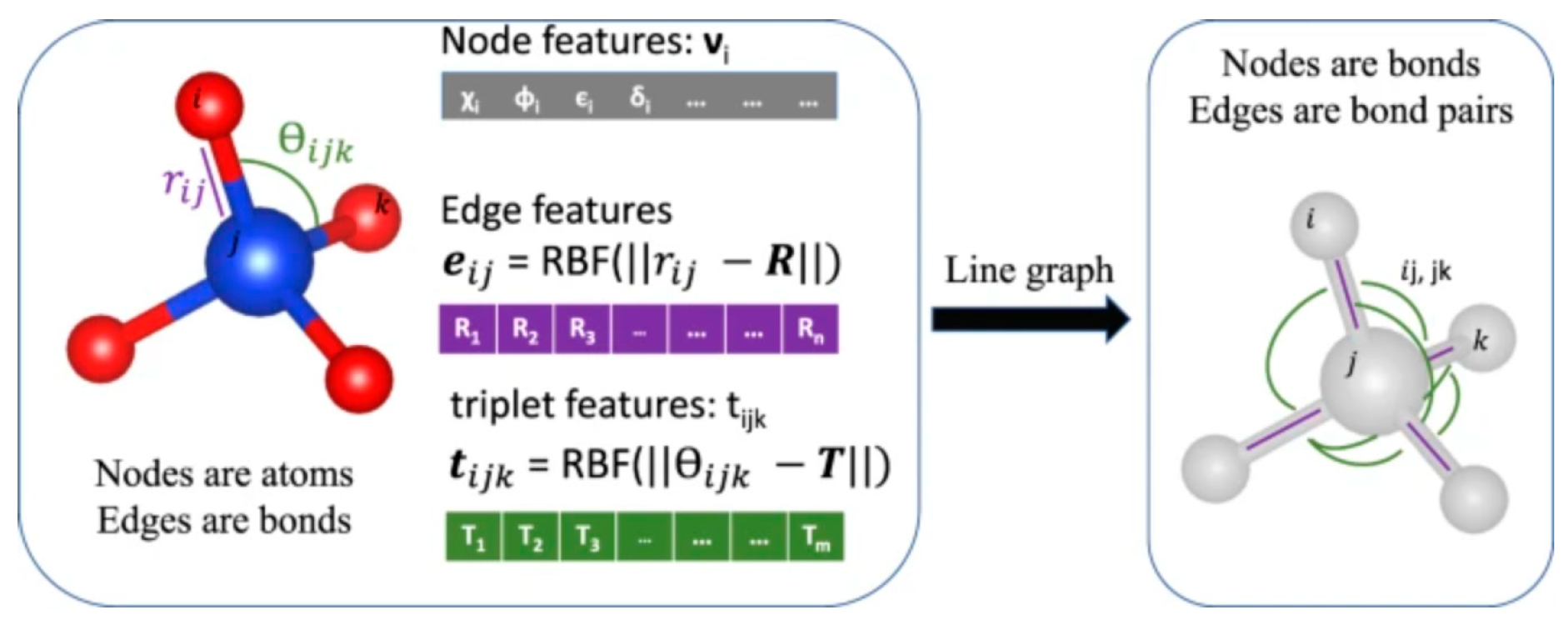

Advanced structural embedding: State-of-the-art energy-materials GNNs now combine learned element embeddings that capture periodic-table trends with structural embeddings that encode bonds, angles, and higher-order motifs. For example, ALIGNN augments node embeddings with a line-graph of bond angles, cutting band-gap MAE to ≈0.12 eV across 52 solid-state targets—an order-of-magnitude improvement for battery and thermoelectric datasets [1].

Figure 2.

Schematic showing undirected crystal graph representation and corresponding line-graph construction. Each node in the atomistic graph is assigned input node features based on its atomic species: electronegativity, group number, covalent radius, valence electrons, first ionization energy, electron affinity, block, and atomic volume. (Reproduced with permission from [1]).

Figure 2.

Schematic showing undirected crystal graph representation and corresponding line-graph construction. Each node in the atomistic graph is assigned input node features based on its atomic species: electronegativity, group number, covalent radius, valence electrons, first ionization energy, electron affinity, block, and atomic volume. (Reproduced with permission from [1]).

Moreover, EOSnet further injects graph-overlap-matrix fingerprints into the embedding layer, pushing MAE to 0.16 eV and enabling a robust metal/non-metal classification for photovoltaic candidates [13]. More recent “elEmBERT” tokenizers treat each element symbol as a sub-word unit, allowing the unified pre-training of crystal and molecule graphs; this boosts cross-domain transfer while keeping model size modest—which is critical for resource-constrained labs [14].

Attention mechanisms: Graph-attention layers let models focus on catalytically active atoms or redox-relevant sublattices. GATGNN employs stacked local plus global attention to rank atomic contributions, outperforming GNN baselines on Materials Project band gaps and delivering interpretable saliency maps for alloy hydrogen-evolution catalysts [15]. ACGNet extends this idea by fusing attention scores with physically motivated descriptors (oxidation state, coordination) and improving charge-density prediction for intermetallic catalysts [16]. Transformer architectures, frequently employing multi-head self-attention, represent a widely used framework for implementing such attention mechanisms, which are particularly effective in capturing long-range dependencies within complex material structures [17].

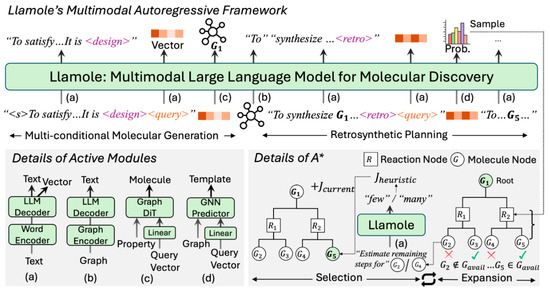

Multimodal fusion with large language models (LLMs): Coupling text-based LLM embeddings with graph features yields hybrid foundation models that reason over both structural and contextual knowledge (Figure 3). MolPROP concatenates BERT sentence vectors of synthesis protocols with molecular graphs, boosting conductivity predictions for Li-battery electrolytes by 18% [10]. PolyLLMem extends the idea to polymers via joint Uni-Mol + LLM encoders, capturing long-range sequence effects critical to proton-exchange membranes [18]. At the frontier, Llamole enables bidirectional generation of text and molecular graphs, unlocking inverse design workflows that propose synthetically accessible cathode materials along with retrosynthetic plans in a single pass [11].

Figure 3.

Overview of Llamole: Trigger tokens (<design> and <retro>) switch active modules from the base LLM to the respective graph component. The subsequent <query> token utilizes output vectors from the LLM to summarize past texts as conditions. Using these, Llamole generates molecules and predicts one-step reactions. Enhanced with a graph encoder and A* search, Llamole efficiently plans synthesis routes through selection and expansion iterations on the AND-OR Tree. (Reproduced with permission from [11]).

Figure 3.

Overview of Llamole: Trigger tokens (<design> and <retro>) switch active modules from the base LLM to the respective graph component. The subsequent <query> token utilizes output vectors from the LLM to summarize past texts as conditions. Using these, Llamole generates molecules and predicts one-step reactions. Enhanced with a graph encoder and A* search, Llamole efficiently plans synthesis routes through selection and expansion iterations on the AND-OR Tree. (Reproduced with permission from [11]).

Parallel and distributed training: The shift from thousands to millions of DFT labels has forced GNN workflows onto multi-GPU and HPC clusters. Graph parallelism partitions large crystal graphs across devices, scaling GemNet-OC to billion-parameter regimes and trimming force-MAE on the OC20 catalytic benchmark by 15% at near-linear speed-up [9]. Such distributed training allows week-long single-GPU schedules to collapse into overnight jobs, making high-throughput screening of perovskite proton conductors or Li-solid electrolytes feasible for academic groups.

Ensemble and bootstrap bagging: Energy-materials discovery pipelines increasingly deploy bags of GNNs—each trained on different bootstrap samples or initial seeds—to quantify aleatoric noise and flag out-of-distribution inputs. Frontiers-in-Materials benchmarking shows that a five-model D-MPNN ensemble shrinks prediction intervals by 25% while maintaining nominal coverage for dielectric constants [19]. Moreover, Chen et al. combines ensemble variance with genetic-algorithm sampling to steer molecular-electrolyte generation, doubling the hit rate of low-viscosity candidates at fixed compute cost [20].

Together, these technical advances—richer embeddings, attention-driven interpretability, HPC-level scalability, and LLM-guided multimodality—are turning GNNs into versatile engines for accelerated, autonomous energy-materials discovery.

2.3. Database

Table 1 presents a list of popular datasets that can be used for screening novel energy materials. While some datasets include experimental data, most datasets typically rely on computational methods to generate labels. These datasets often focus on specific targets, such as the electronic band gap, relevant for energy applications.

Table 1.

Common datasets used for the discovery of energy materials.

3. GNN Utility in Accelerating Materials Discovery

The expanding realm of GNN marks a paradigm shift for the discovery of energy materials from a serendipitous discovery to systematic engineering. By integrating property prediction, molecular dynamics simulation, and generative design, GNNs accelerate the entire materials development pipeline.

3.1. Property Prediction

Graph neural networks now underpin state-of-the-art crystal-property prediction pipelines. Firstly, for the prediction of thermodynamic stability, the original CGCNN framework already pushed the mean-absolute error (MAE) for formation energy below ≈0.04 eV atom−1 across Materials Project crystals, enough to flag metastable phases reliably [2].

While early models such as CGCNN and MEGNet established <0.05 eV atom−1 MAE for formation energy, recent advances push both depth and breadth. For example, the hybrid topological-Transformer architecture fuses local graph convolutions with global self-attention, cutting data requirements for niche properties (e.g., elastic constants) by 30–50% and reaching sub-0.25 V MAE for redox voltages [17]. The follow-up ALIGNN framework incorporates bond-angle information and reports MAEs ≈ 0.02 eV atom−1, allowing confident screening of hypothetical structures produced by generative models [1]. For the prediction of electronic band gap, hybrid topological-Transformer variants of MEGNet drive band-gap MAE down to the 0.23–0.28 eV range on mixed organic/inorganic datasets, comparable to hybrid-functional accuracy at a fraction of the cost [26]. For mechanical response, the equivariant MatTen network outputs the full 4-rank elastic tensor for any crystal system; derived bulk and shear moduli exhibit <6% relative error, enabling rapid identification of ultra-stiff ceramics or ductile alloys without additional DFT runs [27].

Closing the discovery-validation gap, the robotic A-Lab platform integrated GNN stability forecasts with language-model synthesis planning and, in 17 days of autonomous operation, successfully crystallized 41 of 58 model-proposed inorganic phases spanning 33 elements, which is evidence that inverse-designed candidates can be delivered to the benchtop on engineering timescales [28].

These results show that once a structure is available, today’s GNNs can predict formation energies, band gaps, and elasticity with errors that are on par with, or even below, the intrinsic uncertainty of many-body electronic structure methods, turning them into practical “digital property meters” for discovery pipelines.

3.2. Molecular Dynamics

Equivariant GNN force fields have closed the accuracy–speed gap that has long limited atomistic simulation. For example, NequIP learns E(3)-equivariant GNN interatomic potentials that achieve force MAEs <20 meV Å−1 while requiring orders-of-magnitude fewer reference frames [29]. The resulting trajectories faithfully reproduce structural and kinetic observables for molecules, oxide slabs, and a lithium super-ionic conductor, yet run three to four orders faster than ab initio MD [30]. A similar example includes Allegro, which uses iterated tensor products of learned equivariant representations without atom-centered message passing [31]. EGraFFBench benchmarks reveal that such descriptor-free equivariant models (e.g., NequIP, Allegro) outperform traditional symmetry-invariant MLPs on Li-ion diffusion and crack propagation, while also retaining energy conservation [32].

Long-range electrostatics have been incorporated via global charge-equilibration heads, extending GNN potentials to ionic solids and solid electrolytes with RMS force errors down to 35 meV Å−1 [4]. Moreover, Implicit Transfer Operator (ITO) Learning framework, a multi-time-resolution surrogate that combines coarse GNN predictions with occasional DFT corrections, enabling the nanosecond-scale sampling of catalytic surfaces at near-DFT accuracy [33].

Together, these studies demonstrate that GNN-based force fields now enable interrogate diffusion, phase transitions, and fracture processes with quantum-level fidelity across the time and length scales relevant to device operation.

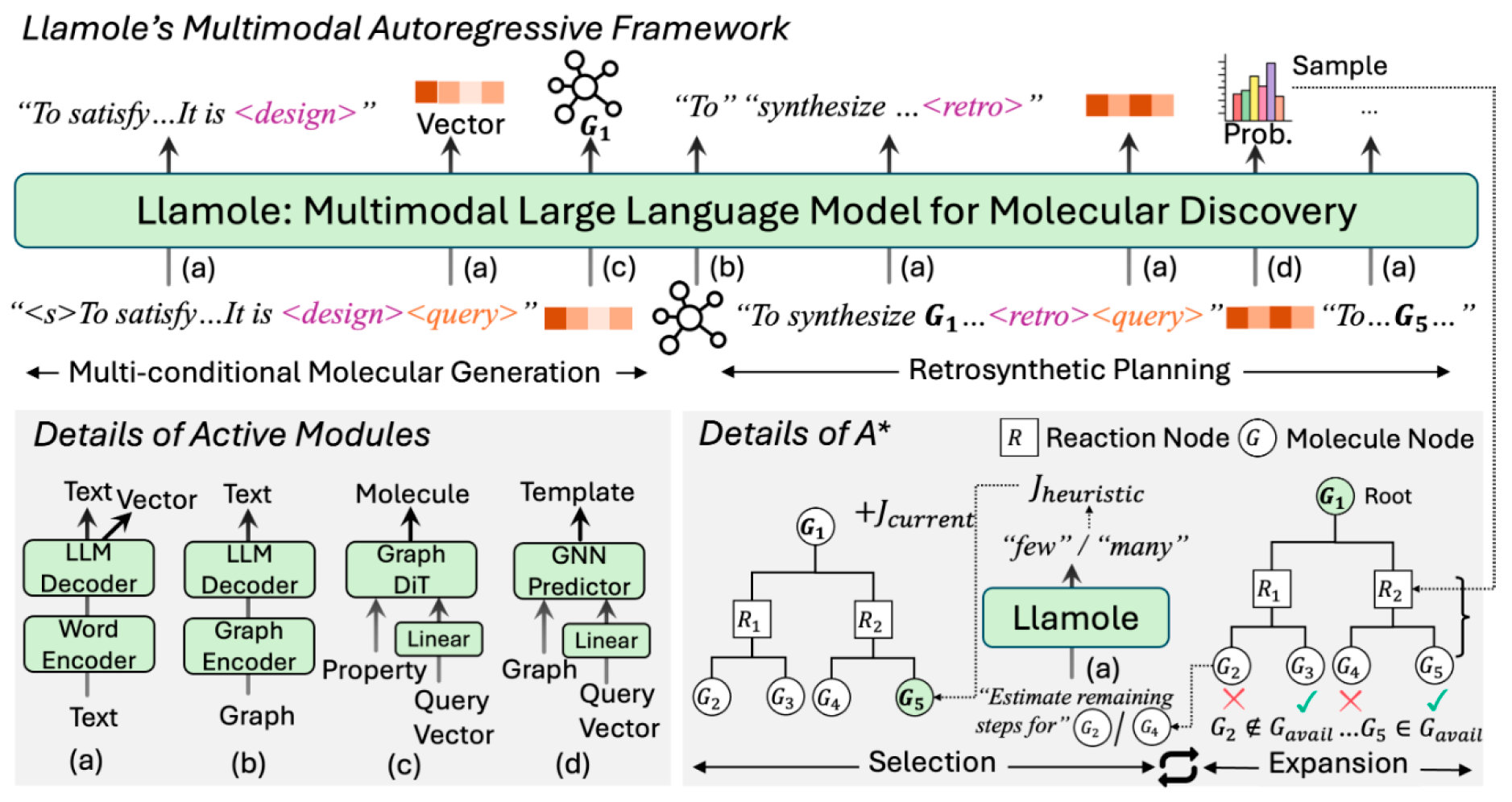

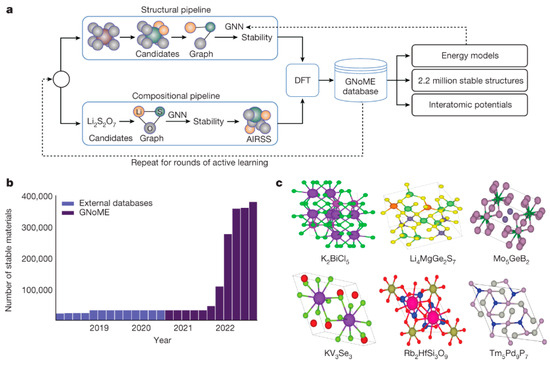

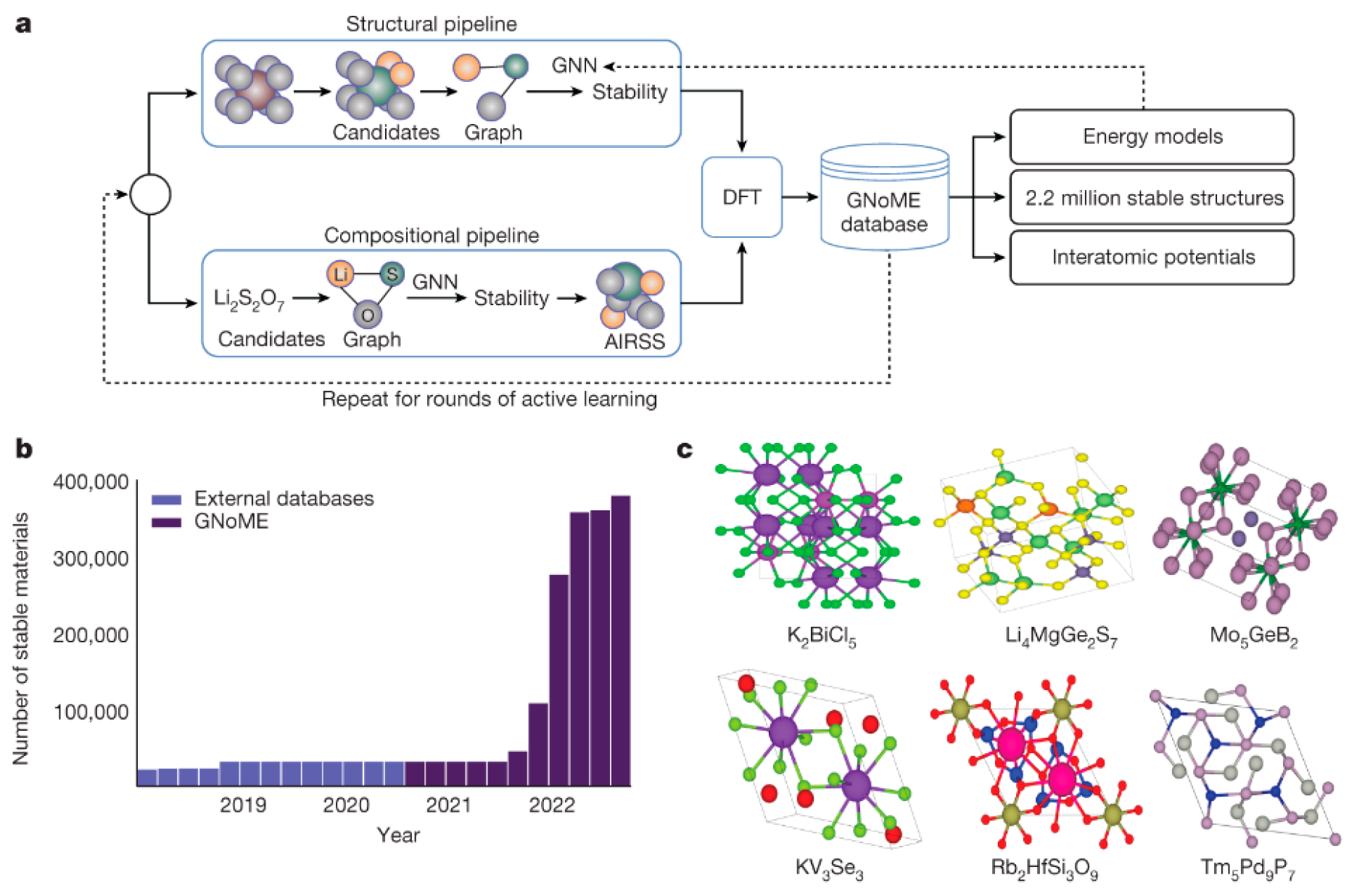

3.3. Inverse Design from Generative Models

GNNs have evolved from evaluative tools to generative engines, creating experimentally viable material candidates, supplying candidates that are already being made in the lab. Conditional generative GNNs produce 3D molecules that satisfy target electronic or steric constraints, achieving >90% validity and high novelty relative to the training data [34]. More recently, DeepMind’s GNoME couples twin GNNs with active learning to predict ∼380,000 previously unknown thermodynamically stable crystals (Figure 4) [35]. At the macro scale, GNoME’s closed loop (GNN prediction -> automated synthesis -> feedback) has already synthesized 41 of 58 AI-suggested phases in 17 days, underscoring the feasibility of autonomous inverse design [28].

Figure 4.

(a) GNoME discovery mechanism: model-based filtration and DFT form a self-improving data flywheel. (b) Scale of exploration: 381,000 new stable inorganic crystals discovered—nearly an order of magnitude beyond prior work. (c) Experimental validation: 736 crystals independently verified, with six structural examples shown. (Reproduced with permission from [35]).

Figure 4.

(a) GNoME discovery mechanism: model-based filtration and DFT form a self-improving data flywheel. (b) Scale of exploration: 381,000 new stable inorganic crystals discovered—nearly an order of magnitude beyond prior work. (c) Experimental validation: 736 crystals independently verified, with six structural examples shown. (Reproduced with permission from [35]).

Junction-tree variational models extended to coordination complexes have generated transition-metal ligands with user-specified spin states, later validated by DFT to lie within 0.2 eV of the desired ligand-field energies [36]. Crystal-diffusion VAEs such as ConditionCDVAE+ create van der Waals heterostructures meeting specified band-gap windows, recovering 86% of known structures and proposing thousands of synthetically accessible variants [37]. Moreover, a GPT-/diffusion-based generative GNN trained on ionic-conductive polymers produced 45 molecules, 17 of which doubled room-temperature Li-ion conductivity after molecular-dynamics validation, a 38% hit rate that far exceeds random search [38].

These successes illustrate how generative models and fast GNN scorers can shrink the materials discovery cycle from years to weeks and point toward routine on-demand design of batteries, catalysts, and other functional energy materials.

4. Accelerated Discovery of Materials

Here, we demonstrate this transformation across batteries, solar absorbers, thermoelectrics, and heterogeneous catalysis, where GNN surrogates and physics-aware workflows compress months of computation into minutes and close the loop from target properties to synthesizable candidates.

4.1. Battery Electrolytes and Electrode

For battery electrodes, graph neural networks enable efficient screening, precise property prediction, and generative design—accelerating discovery while reducing the reliance on empirical approaches.

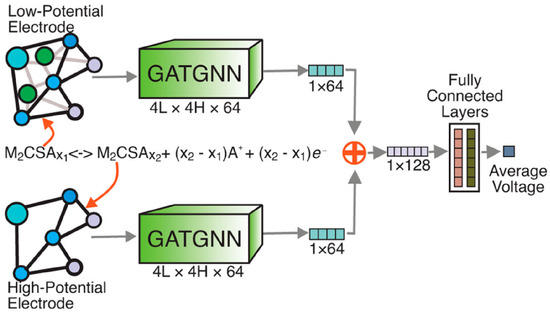

For battery electrodes, Louis et al. propose an attention-based GNN, GATGNN, that reproduces average intercalation voltages within ≈0.10 V and was used to down-select ∼10,000 hypothetical Li/Na/Mg insertion compounds to a shortlist combining high capacity (> 800 mAh g−1) with low volume strain, slashing months of DFT workload to minutes of inference (Figure 5) [39].

Figure 5.

A summary of the GATGNN-based discovery of battery electrodes. (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [39]).

Figure 5.

A summary of the GATGNN-based discovery of battery electrodes. (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [39]).

Specifically, for layered-oxide cathodes, GNN have become indispensable for forecasting key properties of layered oxides. The interpretable ACGNet can predict oxidation potentials and average working voltages with a mean-absolute-error below 0.25 V while attention weights highlight Ni-O motifs prone to structural instability in Li-Ni-Co-Mn systems [16]. At the other extreme end of the scale, Google DeepMind’s GNoME engine, trained on millions of Materials Project structures, now identifies thousands of previously unknown, low-cost layered or gradient cathodes within hours—materials that could raise practical Li-ion specific energies beyond 350 Wh kg−1 [35]. For alloy anodes, trial-and-error alloy screening is expensive; a CGCNN-based high-throughput pipeline has already evaluated > 12,000 binary alloys for insertion voltage and capacity in a single pass, short-listing ≈120 candidates that simultaneously exhibit low lithiation voltages (<0.20 V) and high theoretical capacities (>800 mAh g−1). The same workflow transfers to Na, K, and Mg systems with minimal retraining, demonstrating cross-chemistry portability [40]. For sodium-ion cathodes, a multi-branch voltage GNN (MBVGNN) that fuses global topology and local geometry achieves sub-0.03 eV atom−1 errors across 130,000 structures and has predicted F-substituted layered Na(NiO2)2 phases approaching 5 V, as well as high-capacity NASICON derivatives, pushing projected Na-ion energy densities beyond 160 Wh kg−1 [41]. Complementary graph-based models focused on NASICON compounds rationalize how Na-excess activation raises usable capacities and deliver a ranked list of synthetically accessible, air-stable candidates [42]. For multivalent-ion cathodes, pursuing higher charge-carrier densities, an end-to-end AI workflow integrates sparse Mg data with transfer-learned GNNs, screening ≈ 15,000 Mg-bearing crystals to surface 160 intercalation cathodes above 3 V and 800 Ah L−1—dramatically shortening the concept-to-candidate cycle [43]. An interpretable deep-learning model further generalizes voltage prediction to Mg2+, Zn2+, and Al3+ electrodes at data-poor limits (150–500 structures), achieving ±0.30 V accuracy and revealing chemically intuitive voltage-governing features [44]. Generative frameworks now complete the loop from target property to synthesizable formula. A physics-informed, symmetry-aware diffusion model conditioned on room-temperature ionic conductivity (σ > 10−2 S cm−1) generated thousands of candidate lattices and pinpointed new LiBr/LiCl-rich halides whose computed conductivities rival Li6PS5Cl [45].

For electrolytes, Xie et al. coupled bond-valence descriptors with a GNN to screen tens of thousands of potential inorganic Li solid electrolytes, rapidly flagging phases that combine low formation energies and high Li-ion conductivities, and quantitatively attributing σₗᵢ gains to channel geometry and bond-strength factors [46]. In disordered polymer electrolytes, a multi-task GNN trained on short noisy MD snippets reduces the cost of converged transport calculations by two orders of magnitude and has already uncovered 17 room-temperature conductors with ≈2 × higher ionic conductivity than the training set [47].

Equivariant GNN force fields such as NequIP now deliver quantum-level force accuracy at classical MD computational cost, enabling detailed investigation of dynamic battery phenomena like ion diffusion. Trained on <1000 DFT snapshots, NequIP reproduced Li+ diffusivity in Li6.75P3S11 within statistical error and enabled nanosecond trajectories on 1000-atom cells, exposing collective “knock-on” hops that set the conductivity ceiling of thiophosphate electrolytes [29]. Finally, a universal GNN-derived potential plus rapid descriptors ranked >30,000 Li-containing crystals and confirmed eight room-temperature superionic conductors by ab initio follow-up, offering a 50-fold speed-up over MD-driven searches [30].

Above all, by hierarchically learning atom–bond–topology relations, GNNs are transforming battery-materials discovery from empirical “black-box” exploration into an interpretable, transferable, and even generative “white-box” paradigm.

4.2. Solar Cells Materials

GNNs accelerate solar materials discovery by enabling precise property prediction and targeted screening across organic photovoltaics (OPVs) and perovskites.

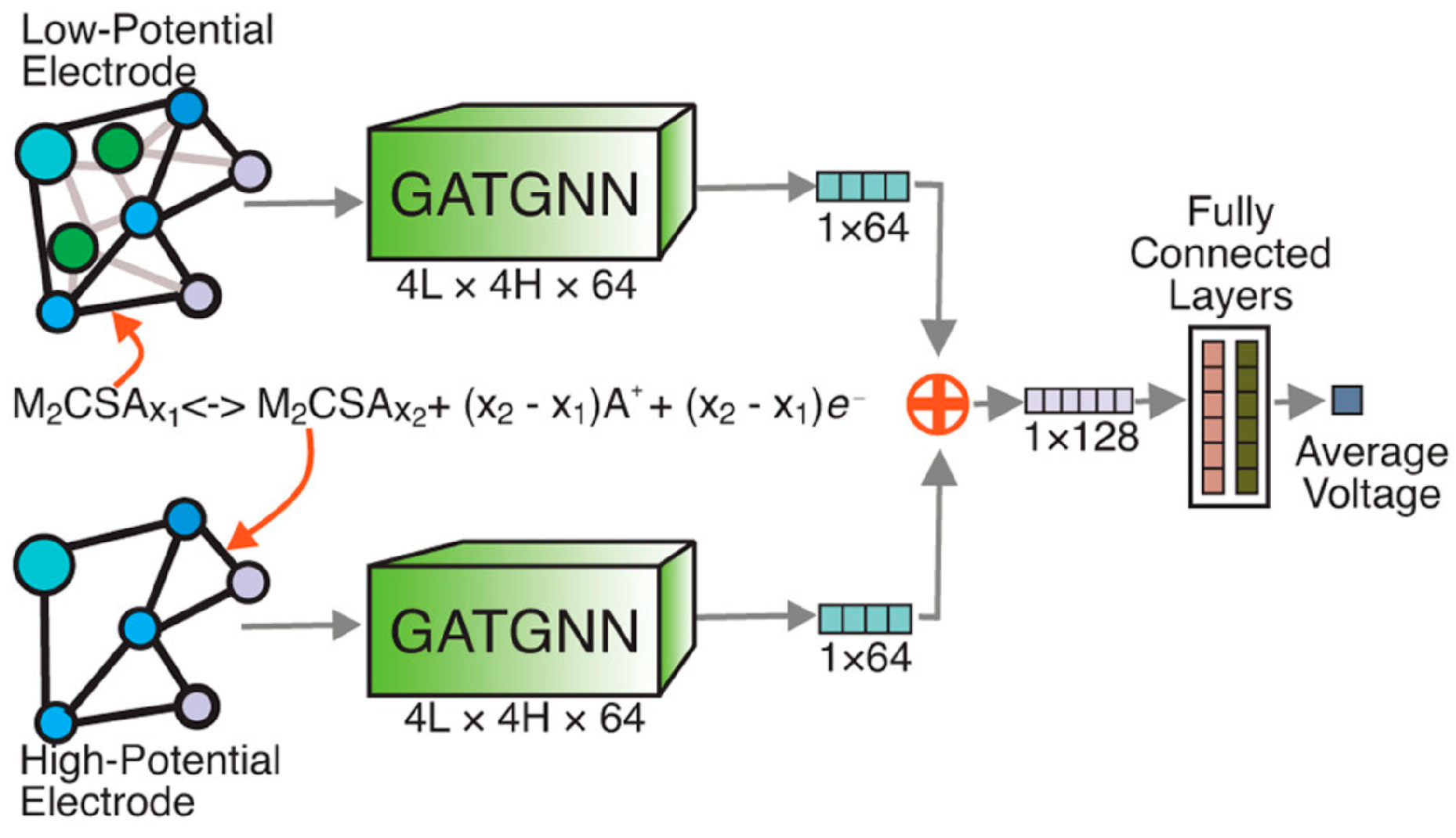

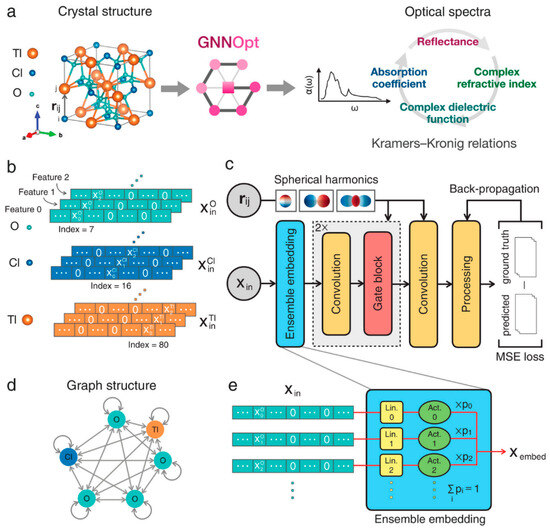

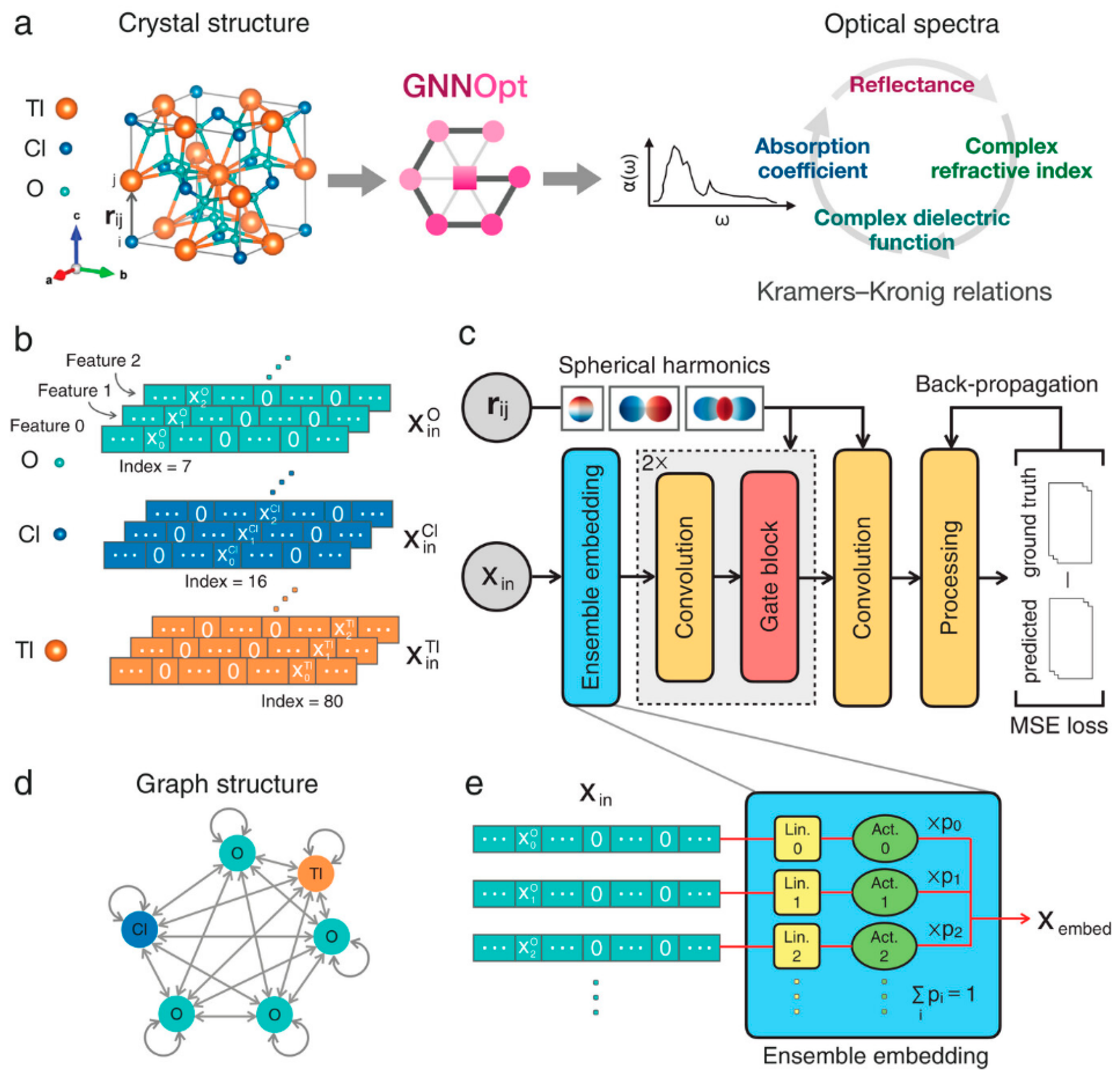

In the discovery of organic photovoltaics (OPVs), key breakthroughs include virtual node-enhanced GNNs (VGNNs) developed by Okabe et al., which predict phonon dispersion and optoelectronic properties with <5% error [48]. Moreover, Wang et al. combined a graph message-passing encoder with LightGBM and cut the time for donor/acceptor (D/A) screening from days of DFT to minutes while retaining an R ≈ 0.85 on 2000 experimental devices [49]. CGCNN-style models trained on 68-element datasets classified and regressed band gaps of 3 × 104 double-perovskite oxides, isolating 310 stable wide-gap (Eg > 2 eV) candidates for power electronics and UV photonics [50]. Follow-up work benchmarked eight GNN variants on a curated 1060 D/A-pair dataset; a graph-attention network reached R = 0.74 (RMSE = 2.63% PCE) and then filtered 45,430 virtual pairs to just 2320 candidates predicted to exceed 15% efficiency [51]. Pushing further, to design OPV molecules, Qiu et al. propose a framework that pretrained a GNN on ~50 k small molecules, coupled it to a GPT-2 generator through reinforcement learning, and produced novel D/A pairs with predicted efficiencies up to 21% [52]. For inorganic absorbers, GNNs have shifted from simple band-gap surrogates to multifunctional predictors and optical-spectrum engines. An equivariant GNNOpt architecture has been proposed by Hung et al. that learns full frequency-dependent dielectric functions from only 944 crystals and screens >5000 unseen structures for high spectroscopic-limited efficiencies—an essential step for tandem and thin-film device design [53]. The structure of GNNOpt is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

GNNOpt architecture for ab initio optical spectra prediction. (a) Input: Only crystal structure (e.g., TlClO4) with atomic distance vectors rᵢⱼ. (b) Atomic feature encoding: Weighted one-hot representation. (c) Workflow: Features optimized by an ensemble embedding layer → processed through equivariant graph convolution and gated nonlinear layers → aggregated to predict frequency-dependent optical properties; trained via MSE minimization. (d) Periodic graph representation: Nodes = atoms, edges = message-passing directions. (e) Ensemble embedding: Per-element linear/activation layers weighted by learnable probabilities pᵢ. (Reproduced with permission from [53]).

Figure 6.

GNNOpt architecture for ab initio optical spectra prediction. (a) Input: Only crystal structure (e.g., TlClO4) with atomic distance vectors rᵢⱼ. (b) Atomic feature encoding: Weighted one-hot representation. (c) Workflow: Features optimized by an ensemble embedding layer → processed through equivariant graph convolution and gated nonlinear layers → aggregated to predict frequency-dependent optical properties; trained via MSE minimization. (d) Periodic graph representation: Nodes = atoms, edges = message-passing directions. (e) Ensemble embedding: Per-element linear/activation layers weighted by learnable probabilities pᵢ. (Reproduced with permission from [53]).

For perovskite, GNN have emerged as transformative tools for accelerating perovskite materials discovery and optimization. For property prediction, large-scale band gap and formation-energy models trained on ~105 ABX3 compositions now routinely achieve mean-absolute errors below 0.28 and 0.12 eV, respectively [26,54]. Also, The GNN-stability classifiers capture dopant-induced phase transitions in systems such as Cd- or Zn-modified CsPbI3 [55]. For synthesizability screening, Gu et al. [56] developed GNN integrating positive-unlabeled (PU) learning and transfer learning achieved 95.7% true-positive rates across 179 experimentally validated perovskites, significantly outperforming empirical ionic radius rules. Such GNN-predicted synthesizability was reported to outperform Goldschmidt-factor heuristics with a true-positive rate of 0.96, which is then used to identify synthesizable perovskite candidates for two potential applications, the Li-rich ion conductors and metal halide optical materials that can be tested experimentally [56]. The multi-modal architectures also be applied in the discovery of perovskite. Rahman et al. fuse SEM images, precursor formulas and processing parameters can simultaneously predict power-conversion efficiency and T80 lifetime in seconds, keeping relative errors under 8% [57].

4.3. Thermoelectric Materials

GNNs efficiently predict thermoelectric transport properties (power factor, κₗ, etc.) and screen millions of compositions, enabling rapid discovery of optimized chalcogenides, half-Heuslers, and oxides with validated performance gains.

Graph-based deep learning is already reshaping research on classic layered chalcogenides. For PbTe-family alloys, CGCNN outperform fully connected and tree-based models in power-factor prediction, achieving sub-µW cm−1 K−2 mean-absolute error while using only composition and crystal topology as inputs—a practical screen for low-toxicity dopant chemistries [58]. Similarly, Laugier et al. trained a CGCNN directly on crystal graphs drawn from Materials Project entries that include the canonical PbTe family. Without resorting to any DFT-derived descriptors, CGCNN reproduced scattering-time-independent power factors with mean-absolute errors on the order of 25%—competitive with classical feature-engineered models and sufficient to down-select dopants before expensive Boltzmann-transport calculations. The study established CGCNN as a viable, data-efficient front end for high-ZT optimization in lead chalcogenides [59].

Beyond layered tellurides, compositionally restricted atomistic line-graph networks (CraLiGNN) now cover the chemically vast half-Heusler domain. CraLiGNN lowers the MAE of Seebeck coefficient and carrier-transport descriptors by ~20–35% and proposes 14 previously unreported half-Heuslers with promising mid-temperature performance, demonstrating how GNNs can extrapolate within sparsely labeled chemical subspaces [60]. For high-temperature oxide thermoelectrics—long hampered by intrinsically high lattice thermal conductivity—a CGCNN-driven κₗ surrogate coupled with the Slack model screened >3 × 105 oxides and highlighted thirty-plus Ag-, Ce- and Pb-rich compositions whose κₗ values fall below 2 W m−1 K−1, providing an interpretable map for phonon-glass electron-crystal design [61]. For thermal-management and thermoelectric platforms, a scale-invariant CGCNN predicted lattice thermal conductivity and revealed 99 quaternary chalcogenides with κₗ < 2 W m−1 K−1—materials that had eluded conventional prototype decoration [62].

For high-temperature oxide thermoelectrics, the PINK framework couples a CGCNN surrogate for elastic moduli with the Slack model, enabling lattice-thermal-conductivity (κₗ) estimates for 3.7 × 105 structures straight from CIF files; the workflow rapidly isolated ≈11,800 compounds with κₗ < 1 W m−1 K−1—including Ag3Te4W and Ag3Te4Ta—as prime low-κ hosts. Complementing this, Fan and Oganov combined a three-body Materials Graph Network (M3GNet) with a 796-compound chalcogenide database, achieving >90% precision and recall in flagging promising n-type candidates, thereby demonstrating that modern GNN architectures can serve as accurate, physics-respecting gatekeepers before costly transport simulations [63].

4.4. Heterogeneous Catalysis

Large scale open datasets such as OC20, OC22 and the new OCx24 supply >1 million relaxed trajectories and 260 million single-point calculations, enabling end-to-end GNNs (CGCNN, PaiNN, GemNet-OC, M3GNet) to be applied in heterogeneous catalysis [7].

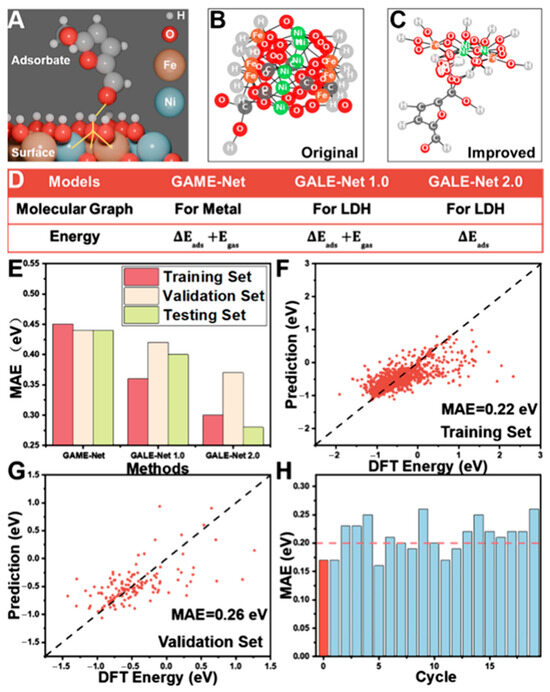

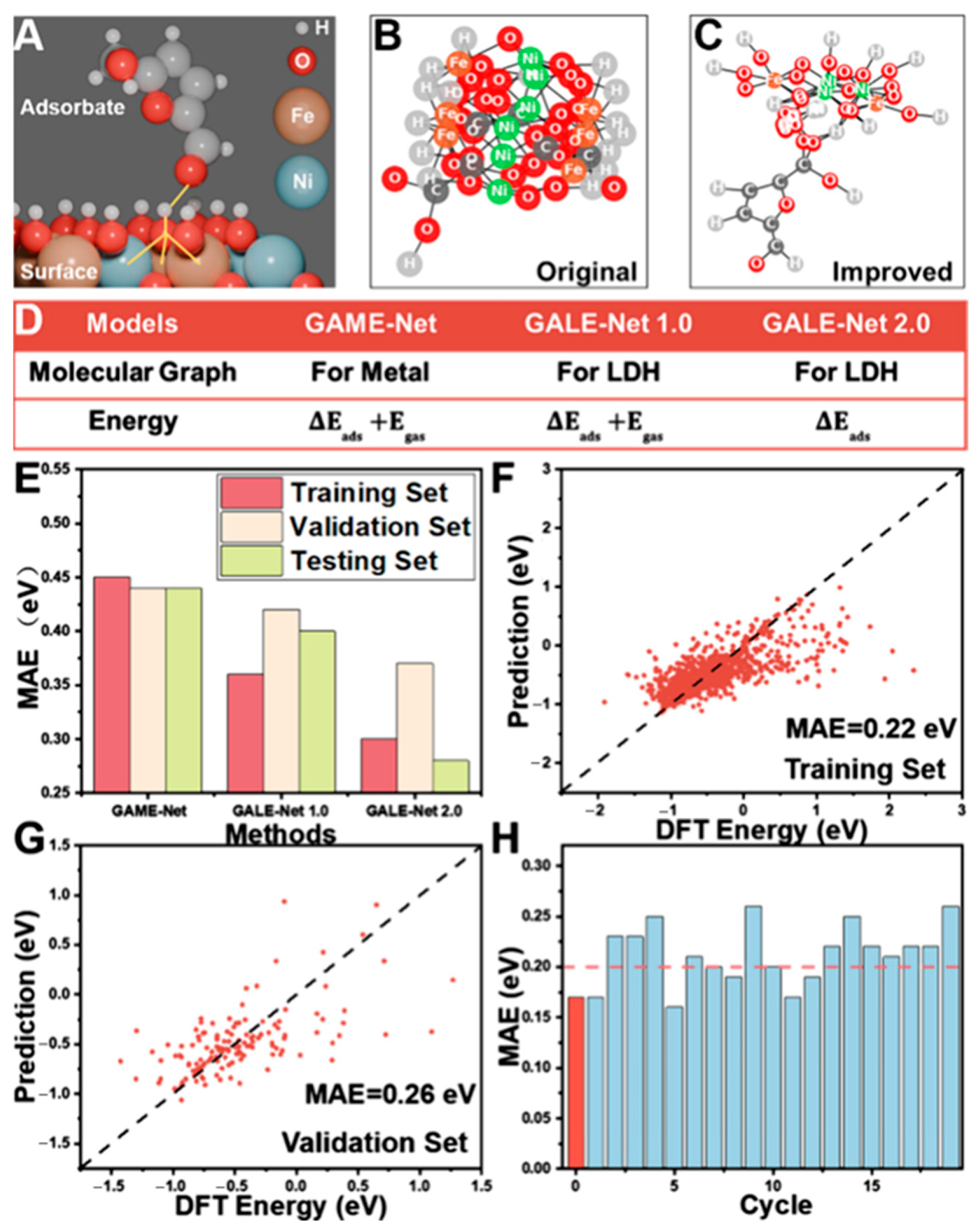

In the electrocatalysis, GNN is used to predict adsorption energies and forces for key reactions including HER, OER, ORR and CO2RR with ∼0.1 eV MAE [8]. Building on the open source data, the sub-graph model ACE-GCN captures lateral adsorbate interactions and can rank >10,000 high-coverage configurations using only ~10% of the DFT labels, thereby accelerating coverage-dependent screening [64]. For complex organic substrates, GALE-Net 2.0 trims DFT wall-time by 6 orders of magnitude while retaining 0.17 eV accuracy, and active-learning variants have been deployed to autonomously explore 3 × 104 single-atom ORR/OER sites on high-entropy alloys (Figure 7) [65].

Figure 7.

GAME-Net Model for Adsorption Energy Prediction. (A) Adsorption configuration of HMF on Ni/Fe (1:1) LDH. (B) Baseline molecular graph generation results. (C) Improved outcomes from rule refinement. (D) Configuration post-second modification. (E) Enhanced model performance after two adjustments. Optimized hyperparameter training yields predictions for the (F) training set and (G) validation set. (H) Repeated random test performance; the red ‘zeroth’ instance represents testing exclusively on Co/Ni 1:2 and 1:3 ratios. (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [65]).

Figure 7.

GAME-Net Model for Adsorption Energy Prediction. (A) Adsorption configuration of HMF on Ni/Fe (1:1) LDH. (B) Baseline molecular graph generation results. (C) Improved outcomes from rule refinement. (D) Configuration post-second modification. (E) Enhanced model performance after two adjustments. Optimized hyperparameter training yields predictions for the (F) training set and (G) validation set. (H) Repeated random test performance; the red ‘zeroth’ instance represents testing exclusively on Co/Ni 1:2 and 1:3 ratios. (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [65]).

In gas-phase heterogeneous catalysis like thermos-catalysis, GNNs excel at representing strained and defect-rich surfaces. The Automatic Graph Representation Algorithm (AGRA) unifies slabs from disparate datasets into transferable graphs and achieves ≤0.1 eV RMSD across five reaction families [66]. A Local-Environment-Pooling GNN further reduces MAE to 0.12–0.15 eV by explicitly encoding step, kink, and curvature motifs [67]. The GAME-Net architecture predicts adsorption energies for large biomass molecules with 0.18 eV error while being 106 × faster than DFT, and strain-aware GNNs now map the continuous response of Eads(ε) for ∼105 surface–adsorbate pairs, offering real-time feedback for strain engineering [68].

GNNs provide a concise structure–property bridge for photo-active semiconductors. Combining molecular graphs with pH, temperature and other experimental descriptors, a TiO2-based GAT model predicts photodegradation rate constants (446 organics) with R2 = 0.90 and RMSE = 0.17 [69]. At the materials-design level, ChemGNN employs adaptive chemical-environment encoding to cut band-gap MAE of doped g-C3N4 systems by >50%, routinely achieving <0.2 eV error and supporting high-throughput visible-light catalyst discovery [70].

Similar deep GNN ensembles now generalize to borates, oxides and sulfides for CO2 reduction and organic synthesis [71]. The field is moving from “static adsorption energies” toward “dynamic reaction networks”. Recent advances show that physics-equivariant force fields, multimodal pre-training and active microkinetic coupling are propelling GNNs into the time-resolved domain of catalysis. The scalar–vector dual E2GNN achieves ab initio energy + force accuracy while permitting nanosecond surface-MD on 103-atom slabs, thereby supplying statistically converged ensembles of transition states for downstream kinetics at <1% of the DFT cost [4]. Moreover, Wander et al. [72] demonstrates that pre-trained GNN potentials enable accurate Hessian calculations for determining Gibbs free energy corrections (including significant translational entropy contributions) with an MAE of 0.042 eV at 300 K and improving transition state optimization convergence by reducing the number of unconverged systems by 65 to 93% overall convergence in heterogeneous catalysis. Collectively, these developments are transforming GNNs from static adsorption-energy estimators into engines capable of building, updating, and interpreting full reaction networks under realistic working conditions, thereby bridging the remaining gap between atomic simulations and reactor-scale catalyst design.

5. Limitations of GNNs on Materials Discovery

Above all, property-prediction GNNs rapidly rank candidates by performance metrics that matter; GNN-accelerated MD illuminates the atomistic mechanisms behind those metrics; generative and closed-loop frameworks leverage both to design and realize materials that satisfy user-defined targets. Together, they convert materials discovery from serendipity into a data-driven, iterative engineering process.

Despite rapid progress, current GNN-based pipelines for materials discovery face several structural limitations that practitioners should weigh against reported headline metrics.

- (i.)

- High training cost: Deeper/equivariant GNNs and foundation-style potentials improve accuracy but raise training cost and make mechanistic interpretation harder compared with descriptor-based models (e.g., scaling relations, linear models). For the training cost, the data requirements of GNNs can be two orders of magnitude higher than other simpler regression algorithms [73]. Equivariant GNN interatomic potentials (e.g., NequIP, MACE, CHGNet) scale roughly linearly with system size under local cutoffs, yet their spherical-tensor products and message-passing layers impose high per-interaction costs so million-atom MD typically necessitates multi-GPU distribution and kernel/communication optimizations [29], which is almost undoable for most of research group.

- (ii.)

- Poor interpretability: For interpretability, classical ML methods built on hand-crafted, physically meaningful descriptors affords inherent interpretability: linear/ensemble models permit straightforward feature attribution, partial-dependence analysis, and domain-aligned narratives (e.g., electronegativity spread, or valence electron counts driving trends). This transparency is a key reason such models remain popular for mechanism-seeking studies, even when they sacrifice some accuracy on complex tasks [74]. By contrast, GNNs embed atomic graphs and learn task-specific representations end-to-end; their decisions are not immediately legible. Attention mechanisms provide an appealing window, yet attention weights are not universally reliable proxies for causal importance, so care is required when interpreting them [75].

- (iii.)

- The validity of generative models: Generative GNNs and diffusion models can satisfy formal validity and property targets while proposing candidates that are kinetically inaccessible, unstable under processing, or incompatible with available precursors. Synthesis-aware models and autonomous labs narrow—but do not close—the gap: even tightly integrated systems (e.g., A-Lab) report partial success rates (74%) and require expert oversight for recipe design, safety, and failure diagnosis [28].

- (iv.)

- Performance Dependency on Data Modality: Classical ML models (e.g., fully connected neural networks, convolutional neural networks) often require extensive and potentially lossy feature engineering to handle such non-Euclidean data, forcing structural information into fixed-dimensional vectors, which can obscure critical topological and relational details [2,3].

Comparison with other ML methods, GNNs generally outperform classical ML models like feature-engineered regressors when structure–property relations dominate the signal (e.g., intercalation voltages learned directly from crystal graphs). However, for datasets with clear and well-defined feature engineering, classical ML algorithms often perform better. For example, for solid-electrolyte transport, recent benchmarks show that universal ML interatomic potentials (mostly GNN-based uMLIPs) attain near-DFT fidelity for migration barriers—beating classical surrogates—while for polymer electrolytes with rich handcrafted features, XGBoost can outperform deep nets in conductivity prediction [76]. For perovskites, broad benchmarks across formation energy and band gap indicate that GNNs (CGCNN/M3GNet/ALIGNN-style) outperform linear and kernel methods and are competitive with tree ensembles, especially in low-label or out-of-distribution regimes. For synthesizability, a GNN with positive-unlabeled and transfer learning vastly outperforms heuristic (Goldschmidt) rules (TPR ≈ 0.96), illustrating a clear advantage when latent structural motifs drive outcomes [54]. However, in thermoelectric power-factor prediction with strong, human-crafted features, a systematic study found random forests (and XGBoost) outperform GNN on accuracy and interpretability [58].

In practice, descriptor-rich tasks often favor classical ML models; structure-first discovery favors GNNs.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

GNN have matured from niche surrogates into a unifying, end-to-end framework that now underpins every major stage of energy-materials discovery—from rapid ranking of candidate structures, through nanoscale mechanistic simulation, to inverse design and autonomous experimentation. By natively encoding atomic connectivity, bond geometries, and even long-range electrostatics, today’s angle-aware and equivariant GNNs routinely achieve ∼10 meV-atom−1 accuracy for formation energies, sub-0.1 V errors for battery voltages, and force fidelities sufficient for nanosecond molecular dynamics. When coupled with large public datasets, distributed training, calibrated ensembles, and multimodal fusion with language models, they collapse years of trial-and-error into weeks of data-driven iteration, already delivering experimentally verified batteries, catalysts, and adsorbents.

Looking forward, three grand challenges remain. (i) Data scarcity and bias. Many technologically critical chemistries—solid electrolytes, metastable perovskites, multivalent hosts—still lack the millions of high-quality labels that fuel state-of-the-art models. Foundation pre-training on noisy, heterogeneous corpora, followed by active-learning loops that target epistemic uncertainty with robotic synthesis, offers a scalable remedy. (ii) Physics beyond locality. Charge transfer, excitons, and phonon–electron coupling all elude purely local message passing. Hybrid GNN–field solvers, global attention, and symmetry-aware hierarchical embeddings are promising routes to embed non-local interactions without prohibitive cost. (iii) Robust autonomous discovery. As GNN-driven pipelines progress from advisory tools to fully closed-loop platforms, rigorous uncertainty quantification, causal interpretability, versioned data provenance, and safety guardrails must be embedded at every stage to ensure reliable, reproducible, and ethically aligned materials exploration. (iv) Catalysis under realistic conditions. For heterogeneous catalysis, surfaces reconstruct, solvate, and change the oxidation state under operando conditions; capturing these effects requires explicit solvents, fields, dynamics, and multiscale kinetics. Current GNN/MLIP models rarely couple all of these, so predictions trained at 0 K/UHV or vacuum slabs may mislead under liquid-phase/electrochemical environments or at elevated temperatures/pressures. Best practices emphasize in situ/operando validation and multiscale frameworks that bridge structure dynamics and kinetics [77].

Such advances on GNN will propel the accelerated, sustainable discovery of next-generation materials that meet the urgent demands of a carbon-neutral energy future.

Funding

This research was funded by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grant number ZR2024QF165.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B. Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network for improved materials property predictions. npj Comput. Mater. 2021, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Grossman, J.C. Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks for an Accurate and Interpretable Prediction of Material Properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 145301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ye, W.; Zuo, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ong, S.P. Graph Networks as a Universal Machine Learning Framework for Molecules and Crystals. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 3564–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Lv, Q.; Chen, C.Y.-C.; Shen, L. Efficient equivariant model for machine learning interatomic potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, J.; Shuaibi, M.; Sriram, A.; Günnemann, S.; Ulissi, Z.; Zitnick, C.L.; Das, A. GemNet-OC: Developing Graph Neural Networks for Large and Diverse Molecular Simulation Datasets. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.02782. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, J.; Kim, J.; Shuaibi, M.; Wander, B.; Duijf, B.; Mahesh, S.; Lee, H.; Gharakhanyan, V.; Hoogland, S.; Irtem, E.; et al. Open Catalyst Experiments 2024 (OCx24): Bridging Experiments and Computational Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.11783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanussot, L.; Das, A.; Goyal, S.; Lavril, T.; Shuaibi, M.; Riviere, M.; Tran, K.; Heras-Domingo, J.; Ho, C.; Hu, W.; et al. Open Catalyst 2020 (OC20) Dataset and Community Challenges. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6059–6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, A.; Das, A.; Wood, B.M.; Goyal, S.; Zitnick, C.L. Towards Training Billion Parameter Graph Neural Networks for Atomic Simulations. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.09697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, Z.A.; Cheng, A.C.; Metwally, E. MolPROP: Molecular Property prediction with multimodal language and graph fusion. J. Cheminformatics 2024, 16, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Sun, M.; Matusik, W.; Jiang, M.; Chen, J. Multimodal Large Language Models for Inverse Molecular Design with Retrosynthetic Planning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.04223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, P.; Neubert, M.; Eberhard, A.; Torresi, L.; Zhou, C.; Shao, C.; Metni, H.; van Hoesel, C.; Schopmans, H.; Sommer, T.; et al. Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 2022, 3, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Zhu, L. EOSnet: Embedded Overlap Structures for Graph Neural Networks in Predicting Material Properties. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shermukhamedov, S.; Mamurjonova, D.; Probst, M. Accurate classification of materials with elEmBERT: Element embeddings for chemical benchmarks. APL Mach. Learn. 2025, 3, 026104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, S.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Nasiri, A.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, F.; Hu, J. Graph convolutional neural networks with global attention for improved materials property prediction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 18141–18148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Sha, W.; Han, Q.; Tang, S.; Zhong, J.; Du, J.; Tian, J.; Cao, Y.-C. ACGNet: An interpretable attention crystal graph neural network for accurate oxidation potential prediction. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 473, 143459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, M.; Lacivita, V.; Shin, Y.; Tarakanova, A. Accelerating materials property prediction via a hybrid Transformer Graph framework that leverages four body interactions. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, D.-B. Multimodal machine learning with large language embedding model for polymer property prediction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, C.M.A.; Bhandari, G.; Nasrabadi, N.M.; Romero, A.H.; Gyawali, P.K. Enhancing material property prediction with ensemble deep graph convolutional networks. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1474609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Li, Y.-P. Uncertainty quantification with graph neural networks for efficient molecular design. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirklin, S.; Saal, J.E.; Meredig, B.; Thompson, A.; Doak, J.W.; Aykol, M.; Rühl, S.; Wolverton, C. The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD): Assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. npj Comput. Mater. 2015, 1, 15010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtarolo, S.; Setyawan, W.; Hart, G.L.W.; Jahnatek, M.; Chepulskii, R.V.; Taylor, R.H.; Wang, S.; Xue, J.; Yang, K.; Levy, O.; et al. AFLOW: An automatic framework for high-throughput materials discovery. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2012, 58, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draxl, C.; Scheffler, M. The NOMAD laboratory: From data sharing to artificial intelligence. J. Phys. Mater. 2019, 2, 036001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, K.; Garrity, K.F.; Reid, A.C.E.; DeCost, B.; Biacchi, A.J.; Hight Walker, A.R.; Trautt, Z.; Hattrick-Simpers, J.; Kusne, A.G.; Centrone, A.; et al. The joint automated repository for various integrated simulations (JARVIS) for data-driven materials design. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.; Wang, Q.; Ganose, A.; Dopp, D.; Jain, A. Benchmarking materials property prediction methods: The Matbench test set and Automatminer reference algorithm. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omprakash, P.; Manikandan, B.; Sandeep, A.; Shrivastava, R.; P, V.; Panemangalore, D.B. Graph representational learning for bandgap prediction in varied perovskite crystals. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 196, 110530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Horton, M.K.; Munro, J.M.; Huck, P.; Persson, K.A. An equivariant graph neural network for the elasticity tensors of all seven crystal systems. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, N.J.; Rendy, B.; Fei, Y.; Kumar, R.E.; He, T.; Milsted, D.; McDermott, M.J.; Gallant, M.; Cubuk, E.D.; Merchant, A.; et al. An autonomous laboratory for the accelerated synthesis of novel materials. Nature 2023, 624, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzner, S.; Musaelian, A.; Sun, L.; Geiger, M.; Mailoa, J.P.; Kornbluth, M.; Molinari, N.; Smidt, T.E.; Kozinsky, B. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maevskiy, A.; Carvalho, A.; Sataev, E.; Turchyna, V.; Noori, K.; Rodin, A.; Castro Neto, A.H.; Ustyuzhanin, A. Predicting ionic conductivity in solids from the machine-learned potential energy landscape. Phys. Rev. Res. 2025, 7, 023167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaelian, A.; Batzner, S.; Johansson, A.; Sun, L.; Owen, C.J.; Kornbluth, M.; Kozinsky, B. Learning local equivariant representations for large-scale atomistic dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bihani, V.; Mannan, S.; Pratiush, U.; Du, T.; Chen, Z.; Miret, S.; Micoulaut, M.; Smedskjaer, M.M.; Ranu, S.; Krishnan, N.M.A. EGraFFBench: Evaluation of equivariant graph neural network force fields for atomistic simulations. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, M.; Winther, O.; Olsson, S. Implicit Transfer Operator Learning: Multiple Time-Resolution Models f or Molecular Dynamics; Oh, A., Naumann, T., Globerson, A., Saenko, K., Hardt, M., Levine, S., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 36, pp. 36449–36462. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer, N.W.A.; Gastegger, M.; Hessmann, S.S.P.; Müller, K.-R.; Schütt, K.T. Inverse design of 3d molecular structures with conditional generative neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, A.; Batzner, S.; Schoenholz, S.S.; Aykol, M.; Cheon, G.; Cubuk, E.D. Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature 2023, 624, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandgaard, M.; Linjordet, T.; Kneiding, H.; Burnage, A.L.; Nova, A.; Jensen, J.H.; Balcells, D. A Deep Generative Model for the Inverse Design of Transition Metal Ligands and Complexes. JACS Au 2025, 5, 2294–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Huang, Q.; Huang, C.; Li, C.; Liu, K.; Sa, B.; Yu, Y.; Xue, D.; Liu, Z.; Dai, M. Deep generative model for the inverse design of Van der Waals heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ye, W.; Lei, X.; Schweigert, D.; Kwon, H.-K.; Khajeh, A. De novo design of polymer electrolytes using GPT-based and diffusion-based generative models. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, S.-Y.; Siriwardane, E.M.D.; Joshi, R.P.; Omee, S.S.; Kumar, N.; Hu, J. Accurate Prediction of Voltage of Battery Electrode Materials Using Attention-Based Graph Neural Networks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 26587–26594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Hong, Z. Machine learning assisted screening of binary alloys for metal-based anode materials. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 104, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Bai, K.; Sun, S. Artificial intelligence driven design of cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries using graph deep learning method. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, Y.; Jeong, I.; Hur, J.; Jeen, H.; Myung, S.T.; Lee, K.T.; Hong, S.; Yuk, J.M.; Lee, C.W. Data-Driven Design of NASICON-Type Electrodes Using Graph-Based Neural Networks. Batter. Supercaps 2024, 7, e202400186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y. AI-driven accelerated discovery of intercalation-type cathode materials for magnesium batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 108, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J.; Shen, L. Interpretable learning of voltage for electrode design of multivalent metal-ion batteries. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Tawfik, S.A.; Tran, T.; Gupta, S.; Rana, S.; Venkatesh, S. The search for superionic solid-state electrolytes using a physics-informed generative model. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 17, 6945–6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.R.; Honrao, S.J.; Lawson, J.W. High-Throughput Screening of Li Solid-State Electrolytes with Bond Valence Methods and Machine Learning. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 9320–9329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; France-Lanord, A.; Wang, Y.; Lopez, J.; Stolberg, M.A.; Hill, M.; Leverick, G.M.; Gomez-Bombarelli, R.; Johnson, J.A.; Shao-Horn, Y.; et al. Accelerating amorphous polymer electrolyte screening by learning to reduce errors in molecular dynamics simulated properties. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, R.; Chotrattanapituk, A.; Boonkird, A.; Andrejevic, N.; Fu, X.; Jaakkola, T.S.; Song, Q.; Nguyen, T.; Drucker, N.; Mu, S.; et al. Virtual node graph neural network for full phonon prediction. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Feng, J.; Dong, Z.; Jin, L.; Li, M.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y. Efficient screening framework for organic solar cells with deep learning and ensemble learning. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapatra, A.; Uberuaga, B.P.; Stanek, C.R.; Pilania, G. Band gap predictions of double perovskite oxides using machine learning. Commun. Mater. 2023, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zou, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, D. Deep learning accelerated high-throughput screening of organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 5295–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Hei Lam, H.; Hu, X.; Li, W.; Fu, S.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. Accelerating High-Efficiency Organic Photovoltaic Discovery via Pretrained Graph Neural Networks and Generative Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.23766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, N.T.; Okabe, R.; Chotrattanapituk, A.; Li, M. Universal Ensemble-Embedding Graph Neural Network for Direct Prediction of Optical Spectra from Crystal Structures. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2409175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Faraji, S.; Liu, B.; Liu, M. Comparative Analysis of Conventional Machine Learning and Graph Neural Network Models for Perovskite Property Prediction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 16672–16683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremin, R.A.; Humonen, I.S.; Kazakov, A.A.; Lazarev, V.D.; Pushkarev, A.P.; Budennyy, S.A. Graph neural networks for predicting structural stability of Cd- and Zn-doped γ-CsPbI3. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 232, 112672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.H.; Jang, J.; Noh, J.; Walsh, A.; Jung, Y. Perovskite synthesizability using graph neural networks. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, W.; Zhong, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, K.; Lin, X. Enhancing perovskite solar cell efficiency and stability: A multimodal prediction approach integrating microstructure, composition, and processing technology. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 15935–15949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitesswar, U.S.; Bash, D.; Huang, T.; Recatala-Gomez, J.; Deng, T.; Yang, S.-W.; Wang, X.; Hippalgaonkar, K. Machine learning based feature engineering for thermoelectric materials by design. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugier, L.; Bash, D.; Recatala, J.; Ng, H.K.; Ramasamy, S.; Foo, C.-S.; Chandrasekhar, V.R.; Hippalgaonkar, K. Predicting thermoelectric properties from crystal graphs and material descriptors—First application for functional materials. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.06219. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, R.; Luo, X.; Ma, J. Compositionally restricted atomistic line graph neural network for improved thermoelectric transport property predictions. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 136, 155103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, J.; Hu, R.; Luo, X. Predicting lattice thermal conductivity of semiconductors from atomic-information-enhanced CGCNN combined with transfer learning. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 122, 152106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, K.; Park, C.W.; Xia, Y.; Shen, J.; Wolverton, C. Scale-invariant machine-learning model accelerates the discovery of quaternary chalcogenides with ultralow lattice thermal conductivity. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Oganov, A.R. Combining machine-learning models with first-principles high-throughput calculations to accelerate the search for promising thermoelectric materials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanekar, P.G.; Deshpande, S.; Greeley, J. Adsorbate chemical environment-based machine learning framework for heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, W.; Lian, Y.; Tao, S. Graph Neural Network Model Accelerates Biomass Adsorption Energy Prediction on Iron-group Hydrotalcite Electrocatalysts. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 10725–10733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariepy, Z.; Chen, Z.; Tamblyn, I.; Singh, C.V.; Tetsassi Feugmo, C.G. Automatic graph representation algorithm for heterogeneous catalysis. APL Mach. Learn. 2023, 1, 036103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chiong, R.; Hu, Z.; Page, A.J. A graph neural network model with local environment pooling for predicting adsorption energies. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2023, 1226, 114161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo-García, S.; Morandi, S.; Vargas-Hernández, R.A.; Jorner, K.; Ivković, Ž.; López, N.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Fast evaluation of the adsorption energy of organic molecules on metals via graph neural networks. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Solout, M.; Ghasemi, J.B. Predicting photodegradation rate constants of water pollutants on TiO2 using graph neural network and combined experimental-graph features. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Xu, E.; Yang, D.; Yan, C.; Wei, T.; Chen, H.; Wei, Y.; Chen, M. Chemical environment adaptive learning for optical band gap prediction of doped graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 37, 3287–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhong, Y.; Dong, X.; Du, M.; Yuan, H.; Zou, Y.; Wang, X.; Lin, Z.; Xu, D. Data Mining and Graph Network Deep Learning for Band Gap Prediction in Crystalline Borate Materials. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 4716–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wander, B.; Musielewicz, J.; Cheula, R.; Kitchin, J.R. Accessing Numerical Energy Hessians with Graph Neural Network Potentials and Their Application in Heterogeneous Catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 3510–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, S.; Yoon, J.; Tian, N.; Zhong, W.; Tran, K.; Ulissi, Z.W. Convolutional Neural Network of Atomic Surface Structures To Predict Binding Energies for High-Throughput Screening of Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 4401–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.; Agrawal, A.; Choudhary, A.; Wolverton, C. A general-purpose machine learning framework for predicting properties of inorganic materials. npj Comput. Mater. 2016, 2, 16028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Y.-T.; Kauwe, S.K.; Murdock, R.J.; Sparks, T.D. Compositionally restricted attention-based network for materials property predictions. npj Comput. Mater. 2021, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitskiy, A.D.; Humonen, I.S.; Eremin, R.A.; Aksyonov, D.A.; Fedotov, S.S.; Budennyy, S.A. Benchmarking machine learning models for predicting lithium ion migration. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Lin, X.; Luo, R.; Wu, S.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Gong, J. Dynamics of Heterogeneous Catalytic Processes at Operando Conditions. JACS Au 2021, 1, 2100–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).