Abstract

The mechanism of charge partitioning during Coulomb explosion, especially via charge-asymmetric dissociation (CAD) pathways, remains a key question in strong-field molecular dynamics. We present an experimental and theoretical study of CAD in the heteronuclear diatomic molecule iodine bromide (IBr) driven by 800 nm femtosecond laser pulses. Using dc-sliced ion velocity map imaging, we measured the kinetic energy releases of fragment ions Ip+ (p = 1–4) and Brq+ (q = 1–3), observing both charge-symmetric (CSD) and charge-asymmetric (CAD) dissociation channels. A unified model combining charge-resonance-enhanced ionization (CREI) with a classical over-the-barrier (COB) picture is introduced, which accounts quantitatively for the observed channels. The findings reveal the correlated electron–nuclear dynamics in IBr during Coulomb explosion, advance the understanding of strong-field dissociation in heteronuclear systems, and contribute to the analysis of ultrafast charge transfer in molecules.

1. Introduction

The interaction of atoms and molecules with intense laser fields has long been a central theme in physics, giving rise to fundamental phenomena such as high-order harmonic generation [1,2], above-threshold ionization [3,4], and Coulomb explosion (CE) [5,6]. Among these, Coulomb explosion—the rapid fragmentation of a highly charged molecule—serves as a particularly direct probe of correlated electron and nuclear dynamics on ultrafast timescales. This potential was realized through the pioneering technique of Coulomb explosion imaging [7], which has since evolved into a powerful method for interrogating molecular structure and dynamics.

For diatomic molecules, the two ionic fragments from a CE event obey momentum conservation. A key characteristic of this process is the final distribution of charge between the fragments, which primarily follows two distinct pathways: charge-symmetric dissociation (CSD) and charge-asymmetric dissociation (CAD) [8,9,10]. For parent ions with an even total charge, CSD corresponds to p = q. For those with an odd total charge, symmetric partitioning is impossible; in this case, we define CSD as channels where the more easily ionized iodine atom carries the higher charge, reflecting the molecular ionization propensity. Conversely, CAD refers to channels where bromine carries the higher charge. Compared to CSD, CAD generally requires more specific conditions—often involving the population of higher-lying electronic states—and encompasses richer physical processes such as charge transfer and electron localization [11,12,13].

Initial observations of CAD were reported in small homonuclear molecules. For example, studies of N2 and O2 in femtosecond laser fields attributed asymmetric dissociation to mechanisms involving field–dipole coupling and strong-field excitation [14,15]. The observation of CAD in the symmetric N2 system—producing fragment pairs such as N+ + N2+ from N23+ and N+ + N3+ from N24+—demonstrates that strong-field ionization is not governed solely by the intrinsic ionization potentials of the constituent atoms. Instead, it underscores the decisive roles of molecular orbital symmetry, laser-induced electron dynamics, and charge-resonance effects in determining the final ionic charge distributions. Subsequent research extended to heavier halogen molecules like I2, where the formation of highly charged fragments is often explained by models such as enhanced ionization (EI) [16,17,18]. Specific CAD channels in I2 have been further interpreted through direct electronic excitation involving charge-resonant or charge-transfer states [19,20]. Extending this understanding to heteronuclear diatomics introduces an additional layer of complexity. In molecules such as iodine bromide (IBr), the inherent asymmetry in atomic ionization potentials and mass establishes a natural predisposition for charge imbalance. This intrinsic asymmetry competes and couples with laser-induced charge migration dynamics, making the branching between CAD and CSD channels more intricate and rich in physical insight. Consequently, a systematic investigation of heteronuclear systems like IBr, in comparison with homonuclear benchmarks, is crucial for developing a more universal picture of how strong-field charge redistribution correlates with molecular electronic structure.

While significant progress has been made in elucidating CAD dynamics in symmetric molecules, the behavior of heteronuclear systems remains largely unexplored. IBr, a classic heteronuclear diatomic molecule, has been extensively studied in the context of coherent photodissociation control [21,22,23,24]; however, its CAD dynamics in intense femtosecond laser fields have not been reported. In this work, we present an investigation of strong-field dissociative ionization and CAD in IBr driven by 800 nm femtosecond laser pulses. Using dc-sliced ion velocity imaging [25,26], we measure the kinetic energy releases (KERs) for both CAD and CSD channels, detecting fragment ions from Iᵖ+ (p = 1–4) to Brq+ (q = 1–3). To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the observed CAD pathways, we introduce a unified model integrating charge-resonance-enhanced ionization (CREI) [27] with a classical over-the-barrier (COB) model [28]. This model not only accounts for our experimental results but also provides new insights into how molecular asymmetry governs fragmentation pathways in intense laser fields.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Overview

The strong-field dissociative ionization of iodine bromide (IBr) was investigated using a velocity map imaging (VMI) apparatus coupled with an intense femtosecond laser source. The experimental sequence consisted of four main stages: (1) generation of a cold, pulsed molecular beam of IBr; (2) irradiation of the beam at the interaction region by intense, linearly polarized 800 nm femtosecond laser pulses; (3) extraction, velocity mapping, and detection of the resulting fragment ions via a time-sliced imaging system; and (4) reconstruction of the velocity distributions and derivation of kinetic energy releases (KERs) from the analyzed channels. This approach allows for the complete determination of the vector momenta for correlated ion pairs, providing a detailed view of the dissociation dynamics.

2.2. Molecular Beam Preparation

A cold and collimated molecular beam was essential to minimize thermal broadening and achieve high resolution in velocity measurements. Iodine bromide vapor (99.5% purity, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was seeded in helium carrier gas (99.999% purity) at a backing pressure of 0.2 atm. The use of helium ensures efficient supersonic cooling during the expansion. The gas mixture was introduced into the source chamber via a pulsed solenoid valve (General Valve, Parker, Cleveland, OH, USA), operated at 100 Hz with a 100 μs pulse duration) and subsequently collimated by a 1.5 mm diameter skimmer positioned 50 mm downstream. According to supersonic expansion theory, the translational temperature perpendicular to the beam propagation direction, T⊥, can be estimated using Equation (1):

where T0 is the initial temperature (~300 K), γ is the adiabatic index of the carrier gas (He, γ = 5/3), and M is the Mach number. Under our experimental conditions, theoretical calculations indicate that T⊥ can be reduced to a few Kelvin. Considering integration effects over the velocity distribution and residual collisional broadening, the effective translational temperature of the molecular beam is estimated to be approximately 10–20 K, consistent with values reported in the literature under similar jet-cooling conditions [29].

T⊥ ≈ T0/(1 + (γ − 1)M2/2),

2.3. Laser System and Interaction

Femtosecond laser pulses (75 fs full width at half maximum, 800 nm central wavelength, 1 kHz repetition rate) were generated by a Ti:sapphire regenerative amplifier system (Spectra-Physics Solstice Ace, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The laser beam was focused onto the molecular beam at the interaction point using a plano-convex lens (f = 40 cm, Thorlabs LA4148, Newton, NJ, USA). The peak intensity at the focus was calibrated to be approximately 2.7 × 1014 W/cm2 using the well-established method based on the Ar2+/Ar+ yield ratio (see Supplementary Materials for details).

2.4. Ion Velocity Imaging Setup

Fragment ions were analyzed using a custom dc-sliced ion velocity imaging system constructed according to velocity map imaging principles [25]. The apparatus comprises a four-electrode ion lens assembly with dynamic focusing compensation, coupled to a time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer. The lens potentials were optimized via SIMION 8.0 (Scientific Instrument Services, Ringoes, NJ, USA) simulations and set as follows: Repeller: +2500 V; Electrode 1: +2220 V; Electrode 2: +2050 V; and Ground electrode: 0 V. This configuration maximized velocity resolution while preserving spatial focusing. Field uniformity within the interaction and extraction region was verified through electron impact ionization tests using N2 as a reference gas. The velocity resolution of the apparatus was determined to be better than 2% (relative error), corresponding to an absolute uncertainty in KER of approximately 0.1 eV for typical fragments [30,31]. Throughout the experiments, the main reaction chamber was maintained at an ultrahigh vacuum pressure below 5 × 10−8 Pa to minimize background collisions.

2.5. Data Acquisition

Fragment ions were detected by a dual micro-channel plate (MCP) detector coupled with a P47 phosphor screen (H7732-11, Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan). The resultant light spots were recorded using an intensified CCD camera (PI-MAXII, Princeton Instrument, Trenton, NJ, USA), typically operating in a 4 ns shutting mode to enhance signal-to-noise ratio. Each velocity map image represents an accumulation over 3000 laser shots. Background signal was subtracted using an average of 500-shot dark frames recorded with the laser blocked. Simultaneously, time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectra were recorded for ion identification using a photomultiplier tube (H7732-11, Hamamatsu) connected to a 10 GHz digital oscilloscope (LeCroy WavePro 8010HD, Chestnut Ridge, NY, USA). All experimental timing sequences were synchronized and controlled by a digital delay/pulse generator (DG535, Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrum

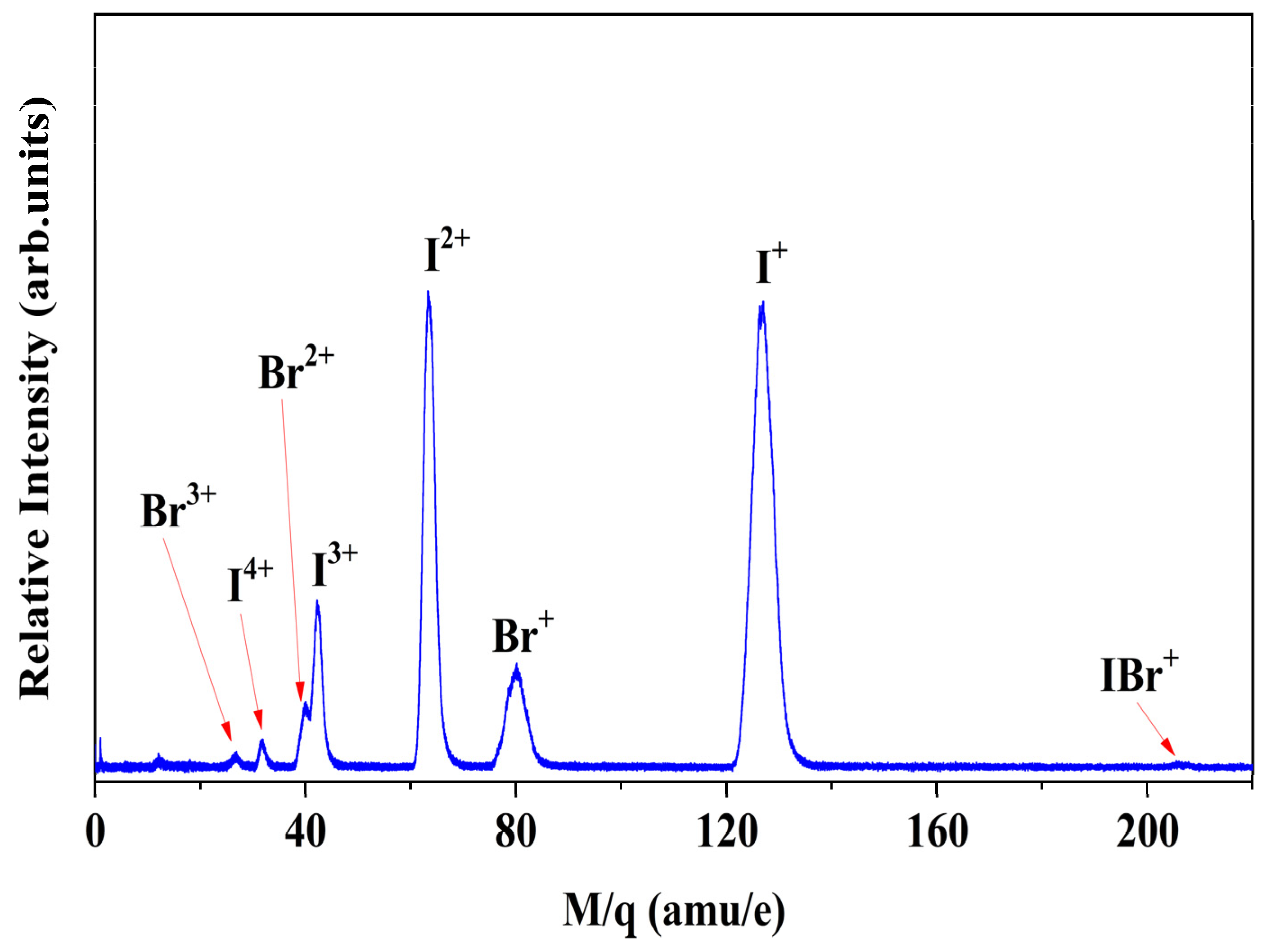

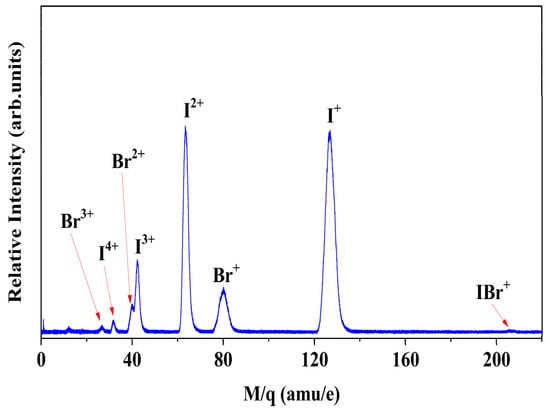

Figure 1 presents the time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrum obtained from the interaction of IBr with 75 fs, 800 nm laser pulses at a peak intensity of 2.7 × 1014 W/cm2. The spectrum is dominated by atomic fragment ions, spanning IP+ (p = 1−4) and Brq+ (q = 1−3). In contrast, the signal for the parent molecular ion IBr+ is exceedingly weak. This observation is corroborated by the velocity map imaging (VMI) results and kinetic energy (KE) release spectra for I+ and Br+ fragments. The VMI images for these low-charge fragments (see Figure 2) show pronounced, diffuse rings near the center, which are characteristic of dissociative ionization channels (e.g., IBr+ → I+ + Br or IBr+ → I + Br+).The corresponding KER distributions for these channels are centered at very low energies, consistent with direct dissociation on a repulsive potential energy surface [32]. The pronounced dominance of atomic fragments over the parent ion signals underscores the high efficiency of dissociative ionization under the present strong-field conditions. It implies that following initial ionization, the molecular ion undergoes rapid, often immediate, fragmentation on an ultrafast timescale, competing effectively with any process that would lead to a stable IBr+ ion.

Figure 1.

Time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrum of IBr under strong-field irradiation. The spectrum, resulting from interaction with 75 fs, 800 nm laser pulses at 2.7 × 1014 W/cm2, is dominated by atomic fragment ions Ip+ (p = 1–4) and Brq+ (q = 1–3). The negligible signal of the parent ion IBr+ underscores the prevalence of efficient dissociative ionization pathways.

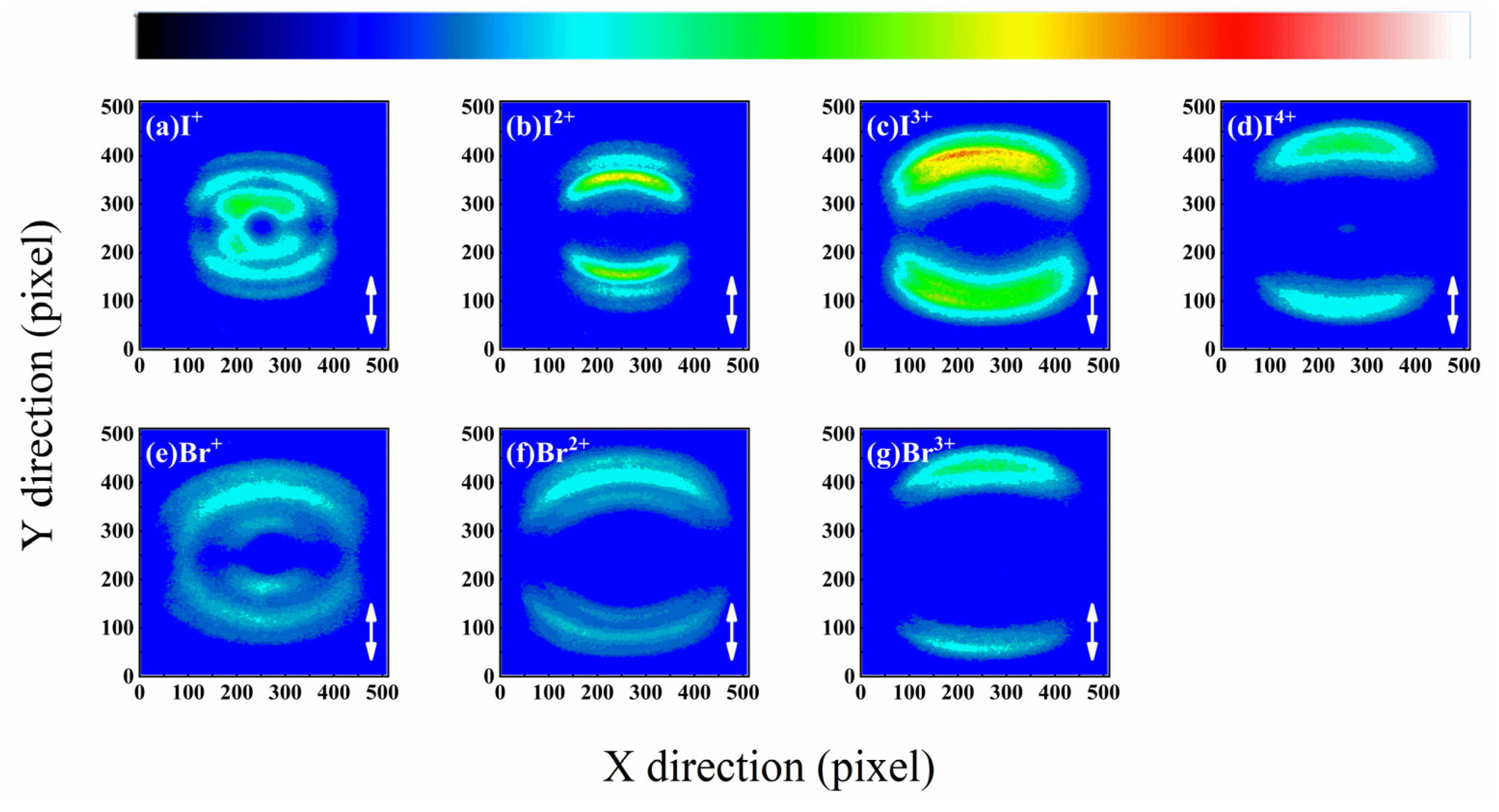

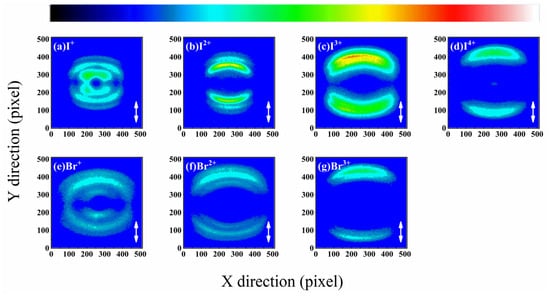

Figure 2.

The pseudo-color sliced images of fragment ions of IBr. Panels (a–g) display the results for the fragment ions (a) I+, (b) I2+, (c) I3+, (d) I4+, (e) Br+, (f) Br2+, and (g) Br3+, respectively. In the images, the color bar encodes the signal intensity, which represents the yield of the ions. The double-headed arrow marks the laser polarization direction.

3.2. Velocity Map Imaging and Kenitic Energy of Fragment Ions

Figure 2 displays the pseudo-color sliced images (512 × 512 pixels) of the fragment ions, Ip+ and Brq+. Panels (a)–(d) correspond to I+, I2+, I3+, and I4+, respectively, while panels (e)–(g) show and Br+, Br2+, and Br3+. Each two-dimensional image records the projection of ion velocities onto the detector plane. Ions with lower initial kinetic energy appear near the center of the image. The pronounced concentric ring structures observed for most charge states are characteristic of dissociating ions with well-defined kinetic energies. The signal intensity, encoded by the color bar (darker color indicating higher yield), represents the relative ion yield. A double-headed arrow on each image indicates the laser polarization direction, which is vertical in the laboratory frame. A slight elliptical distortion is visible in some velocity map images. This arises primarily from the challenge of achieving perfect velocity focusing for multiple ion species with significantly different mass-to-kinetic energy ratios simultaneously. This distortion has been corrected in our data analysis. It introduces an additional systematic broadening in the velocity calculation, the effect of which has been incorporated into the uncertainty assessment of the kinetic values discussed in the following sections.

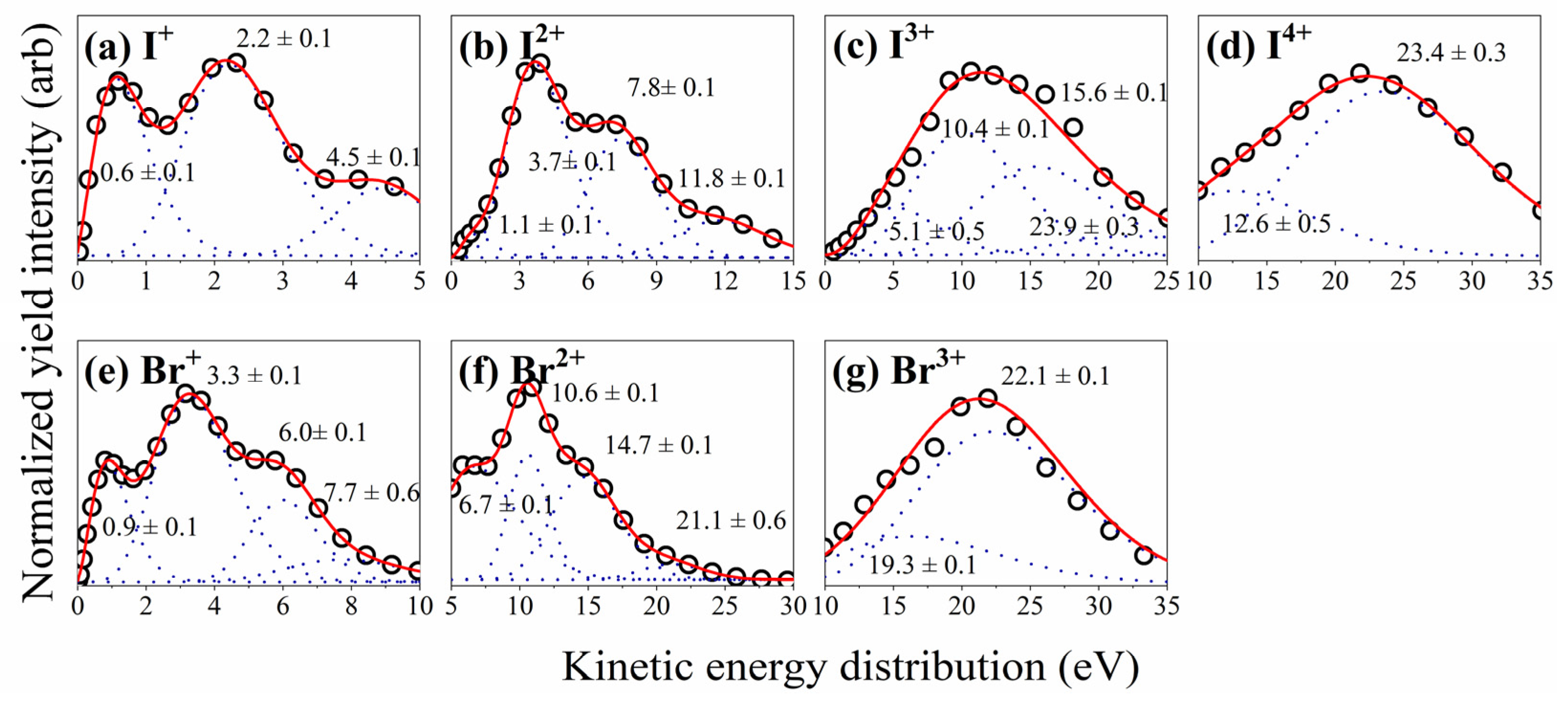

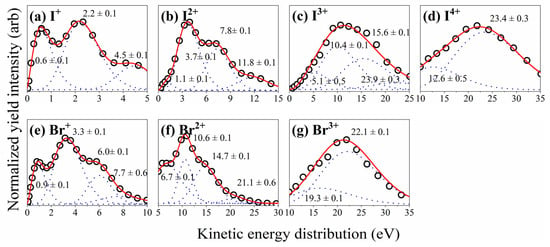

Figure 3 presents the reconstructed kinetic energy spectra for all fragment ions. The raw dc-sliced images were processed using an in-house MATLAB (R2022a) routine. The core procedure is as follows: For each ion, its time of flight (TOF) was determined from the ratio of mass to charge. In the plane perpendicular to the time-of-flight axis, the ions are assumed to travel with constant velocity. Therefore, the pixel position on the sliced image can be converted into a transverse displacement, which, when divided by the TOF, yields the transverse velocity component. This allows for the construction of the two-dimensional velocity distribution for each ion species. The kinetic energy (KE) for correlated fragment ions was then calculated from their measured velocities using Equation (2):

where m is the mass of the fragment ions, and v is their relative velocity. Figure 3 presents the kinetic energy distributions of the generated fragment ions. The horizontal axis denotes the kinetic energy in eV, while the vertical axis represents the normalized yield. Panels (a) through (g) sequentially show the results for: (a) I+, (b) I2+, (c) I3+, (d) I4+, (e) Br+, (f) Br2+, and (g) Br3+. Multiple distinct peaks are resolved in each spectrum, each corresponding to a specific dissociation channel from a defined precursor ion charge state. For instance, the distribution for I+ [panel (a)] features prominent peaks at 0.6 ± 0.1 eV, 2.2 ± 0.1 eV, and 4.5 ± 0.1 eV. Here, the peak center μ is taken as the kinetic energy value, with the standard deviation σ from the Gaussian fit reported as its uncertainty. This uncertainty reflects the intrinsic width of the dissociation channel’s kinetic energy distribution.

KE = mv2/2,

Figure 3.

Kinetic energy distributions of fragment ions of IBr. Panels (a–g) display the results for (a) I+, (b) I2+, (c) I3+, (d) I4+, (e) Br+, (f) Br2+, and (g) Br3+, respectively. The horizontal axis represents the kinetic energy distribution in eV, and the vertical axis shows the normalized yield intensity. The black circles denote the experimental data. The multi-peak Gaussian fitting results are plotted as dotted violet curves, with the centroid positions of the individual component peaks annotated as KE = μ ± σ. The red solid lines represent the simulated distributions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Assignment of Dissocaitiove Ionization and Coulomb Explosion Channels

The kinetic energy (KE) values discussed here correspond to those of individual fragment ions, obtained from their velocity distributions. For a given dissociation channel, the total kinetic energy release (KER) is defined as the sum of the kinetic energies of the two correlated fragments. These measured KERs serve as direct fingerprints for reconstructing specific Coulomb explosion (CE) pathways. A two-body CE process, in which a multiply charged molecular ion undergoes rapid dissociation into two charged fragments, is governed by momentum conservation and Coulomb repulsion. For such a process, producing fragments Xm+ and Yn+, the ratio of their kinetic energies satisfies Equation (3):

where m denotes the mass of the fragment. This characteristic energy–mass correlation allows for the identification of fragment pairs originating from the same precursor ion based on their measured kinetic energies. Applying this criterion to our experimental data enables the assignment of all observed dissociation channels, which are systematically summarized in Table 1.

KE(Xm+)/KE(Yn+) = m(Yn+)/m(Xm+),

Table 1.

Kinetic energy releases (KERs) for identified dissociation channels of IBr. Channel (p, q) denotes the dissociation pathway yielding fragment ions Ip+ and Brq+.

Table 1 compiles the kinetic energy releases (KERs) for the identified dissociation channels of IBr⁽ᵖ+q⁾+, where the measured fragment kinetic energies satisfy the momentum conservation condition for a direct two-body Coulomb explosion. A clear systematic trend in charge partitioning emerges for each channel, denoted as (p, q) and corresponding to IBr(p+q)+→Ip+ + Brq+. The data reveal that the fragment kinetic energy correlates strongly with the total charge of the precursor molecular ion. Channels yielding fragments with low kinetic energies (on the order of a few eV), such as (1,0) and (0,1), are attributed to the dissociation of low-charged precursors (IBr+). In contrast, channels exhibiting high kinetic energies (tens of eV), such as (4,2) and (3,3), originate from the Coulomb explosion of highly charged molecular ions (e.g., IBr6+). This progression confirms that the total KER scales approximately with the product of the final fragment charges, a hallmark of Coulomb-repulsion-dominated dynamics. Notably, several potential channels—such as (1,3), (4,1) and (4,3)—are absent from Table 1 because the measured fragment kinetic energies could not be paired to satisfy the momentum conservation criterion within experimental uncertainty.

Based on the preceding analysis, the discussion now focuses on the remaining channels originating from higher-charged precursors, which exhibit signatures of Coulomb explosion dynamics. A clear pattern emerges regarding charge partitioning. Molecular ions with an even total charge preferentially dissociate into two fragments carrying equal charges (p = q). These pathways are classified as charge-symmetric dissociation (CSD), as exemplified by the (3,3), (2,2), and (1,1) channels. Conversely, dissociation into fragments with unequal charges (p ≠ q) is categorized as charge-asymmetric dissociation (CAD), such as the (2,0), (3,1), and (4,2) channels.

For parent ions with an odd total charge, the dominant pathways are those in which the absolute charge difference between the fragments is one (|p − q| = 1). Among these, channels where the iodine fragment carries the higher charge (p − q = 1)—specifically (3,2) and (2,1)—are also classified as CSD. This preference can be attributed to the higher ionization potential of bromine compared to iodine at equivalent charge states (see Supplementary Materials), making this charge distribution energetically more favorable for a direct Coulomb explosion from the ground ionic state. Consequently, the complementary pathways from the same precursor with p − q = −1, such as (1,2) and (2,3), are correspondingly classified as CAD channels.

To quantitatively support this interpretation, we have included a “Yield” column in Table 1, which lists the integrated signal intensities for each observed channel. For example, the yield of channel (2,1) is substantially higher than that of (1,2), consistent with the energetics dictated by the ionization potential difference. This experimental evidence directly substantiates the preferential population of iodine higher-charge states in odd-charged parent ions. Furthermore, the overall higher yields of CSD channels compared to CAD channels align with the interpretation that CAD processes often involve excited-state dynamics, which are generally less efficient and have more restrictive formation conditions.

4.2. Origin of Charge-Symmetric Dissociation: Role of Charge-Resonance-Enhanced Ionization

The formation mechanisms for charge-symmetric dissociation (CSD) can be understood within a unified framework initiated by charge-resonance-enhanced ionization (CREI). We attribute the production of the observed highly charged molecular ion precursors to the CREI mechanism. In this process, a neutral molecule, upon sequential absorption of photons, undergoes rapid bond stretching during the laser pulse. At a critical internuclear distance, Rc, the ionization potential of the molecule is significantly lowered due to charge-resonance effects, leading to a resonant enhancement of ionization probability and the rapid formation of a highly charged molecular ion. Subsequently, the intense Coulomb repulsion between the charged atomic centers causes the bond to rupture, accelerating the fragments apart in a back-to-back manner.

Within the CREI model, the critical distance Rc for a given CE channel yielding fragments Ip+ and Brq+ can be estimated by equating the Coulomb potential energy at separation Rc to the measured kinetic energy release (KER) of that channel by Equation (4):

where p and q denote the final charge states of the fragments, and Ecoul corresponds to the measured KER (in eV) for that channel. Table 2 summarizes the calculated Rc for all identified CSD channels. The KER column lists the values in the form [center value] ± [standard deviation] eV. Uncertainties in Rc were propagated from the KER uncertainties using standard error propagation formulas.

Table 2.

Critical internuclear distances (Rc) for charge-symmetric dissociation (CSD) channels.

Table 2 lists the calculated Rc for the CSD channels. The progression from IBr2+ to IBr6+ illustrates the sequential ionization process within a dynamically stretching molecule. As the internuclear distance increases under field-driven expansion, the molecular ion can stabilize successively higher charge states until the repulsive Coulomb force overwhelms the remaining bonding interaction, leading to Coulomb explosion at the respective critical distances Rc.

4.3. Origin of Charge-Asymmetric Dissociation: Integrated CREI-COB Model

While the charge-resonance-enhanced ionization (CREI) model successfully accounts for the observed charge-symmetric dissociation (CSD) channels, it cannot consistently explain the charge-asymmetric dissociation (CAD) channels listed in Table 3. A key inconsistency arises for the IBr5+ precursor: the calculated Rc for channel (2,3) is 2.79 ± 0.02 Å, which is notably smaller than the Rc values for lower-charge-state IBr4+precursors. The anomalously small Rc for the channel (2,3) contradicts the general trend that Rc should increase—or at least remain comparable—with greater total repulsive charge. This discrepancy strongly suggests that the formation of CAD channels involves dynamic processes beyond the static, geometry-driven CREI picture, including non-adiabatic transitions, charge-transfer dynamics, or the population of specific repulsive electronic states.

Table 3.

Critical internuclear distances (Rc) for charge-asymmetric dissociation (CAD) channels. The table lists the observed CAD channels, their measured KERs, and the corresponding Rc values calculated using the charge-resonance-enhanced ionization (CREI) model.

Previous studies indicate that CAD likely proceeds through a charge-transfer (CT) event following the initial ionization [19,20]. Our analysis follows a two-step integrated model: (1) a highly charged molecular ion is formed at the critical internuclear distance Rc via the CREI mechanism; and (2) during the subsequent fragment separation, an electron-transfer event—governed by classical over-the-barrier (COB) dynamics—redirects the dissociation from a symmetric to an asymmetric outcome. The COB model provides a quantitative criterion for this charge-transfer step. It defines a critical internuclear distance, Rcrit, within which an electron can be transferred from a donor fragment Ap+ to an acceptor fragment Bq+. Under a static field condition, the critical distance is given by the empirical formula [20] shown in Equation (5):

where Ip is the ionization energy (in eV) of the donor ion Ap+, and Rcrit is given in Å. Beyond Rcrit, the fragments behave essentially as isolated ions, and charge transfer is suppressed. The calculated Rcrit values for all possible CT pathways originating from the observed CSD precursors, together with their corresponding CREI distances Rc, are listed comprehensively in Table 4 (see Supplementary Materials for details).

Table 4.

Critical charge-transfer distances (Rcrit) for possible pathways.

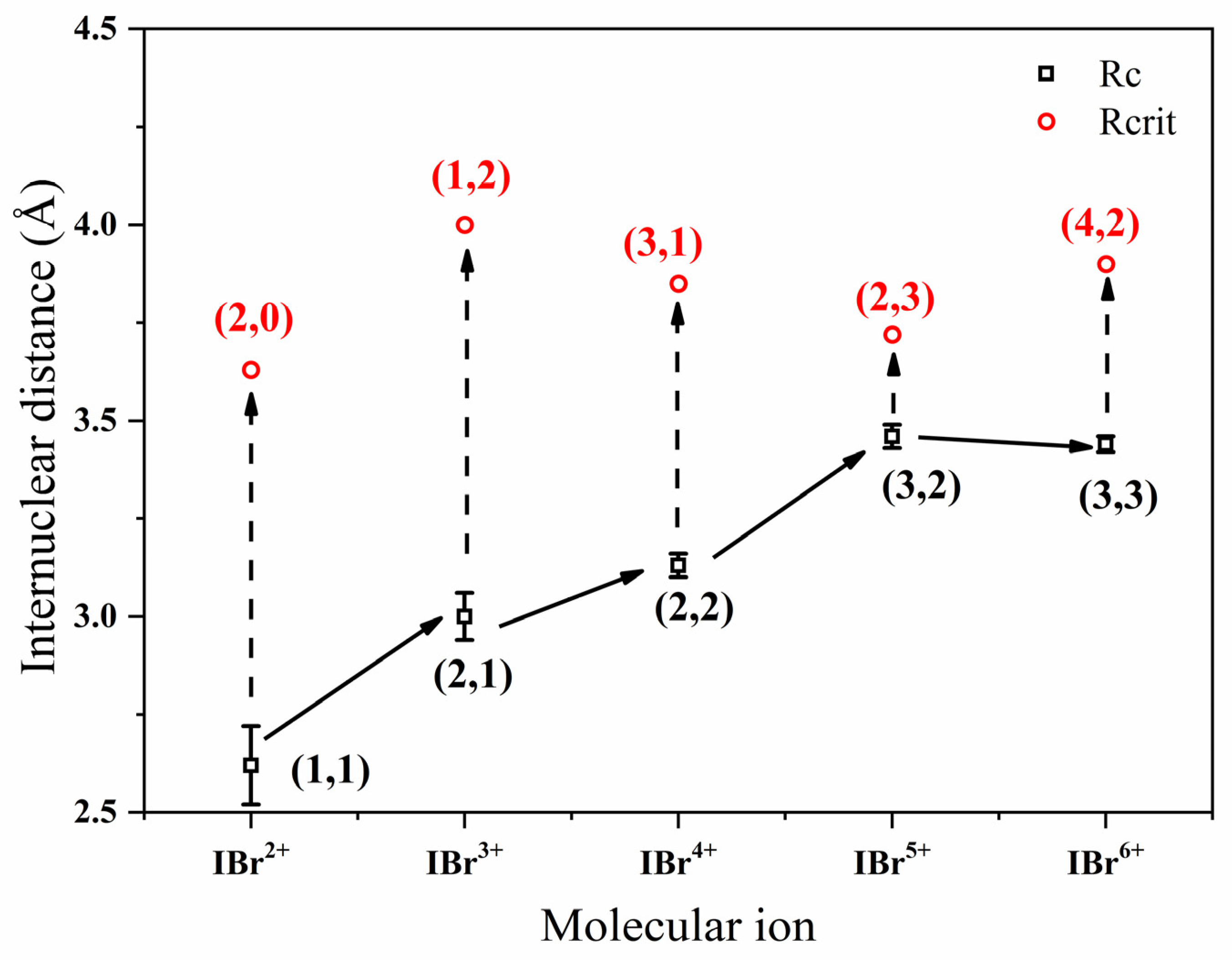

The existence of the observed CAD channels—(2,0), (1,2), (3,1), (2,3) and (4,2)—can be consistently explained by the relation between the critical charge-transfer distance Rcrit and the critical internuclear distance Rc of their precursor states, as detailed in Table 4. Taking the (4,2) channel as an example, which originates from the (3,3) precursor (Rc = 3.44 ± 0.02 Å), its Rcrit is calculated to be 3.90 Å. Since Rcrit > Rc, a clear and substantial window for charge transfer (I3+→Br3+) exists, providing a direct mechanistic basis for the experimental observation of this channel. A CAD channel becomes accessible only if a geometrically allowed charge-transfer window opens before the direct Coulomb explosion occurs. This window is definitively established when Rcrit > Rc. This consistent relationship underscores the role of post-ionization charge-redistribution dynamics in enabling various CAD pathways.

4.4. Conclusion of Discussion

In summary, the complex dissociation landscape of IBr under intense femtosecond laser irradiation has been coherently interpreted through an integrated CREI-COB model. The CREI mechanism governs the initial production of highly charged molecular ions and determines the critical internuclear distance (Rc) at which Coulomb explosion is initiated. Subsequently, the classical over-the-barrier (COB) model describes the charge-redistribution dynamics that occur during fragment separation, thereby dictating the branching between symmetric and asymmetric dissociation pathways.

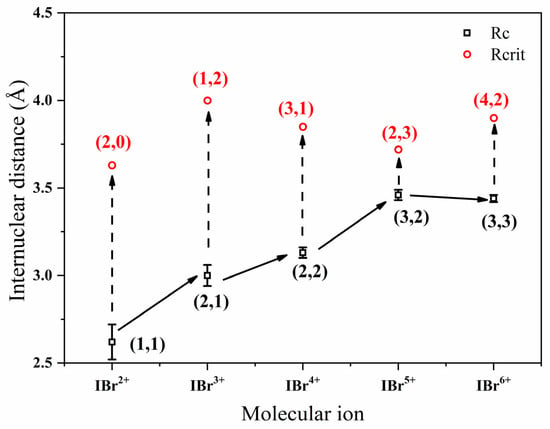

The complete mechanistic pathways are illustrated in Figure 4. The Coulomb explosion process initiates from IBr2+. The solid black line represents the CSD pathway: as the internuclear distance stretches, enhanced ionization occurs, leading to direct Coulomb explosion at the specific Rc of the molecular ion and yielding equally charged fragments. The dashed black line depicts the CAD pathway: after the precursor ion is formed at Rc, if the condition Rc < Rcrit is met, a charge-transfer step takes place prior to explosion, followed by dissociation into an asymmetric fragment pair. Thus, Rc < Rcrit serves as a key prerequisite for the opening of a CAD channel.

Figure 4.

Schematic of Coulomb explosion pathways in IBr(p+q)+. All experimentally observed charge-symmetric dissociation (CSD) channels are marked with black squares, representing the critical internuclear distance (Rc) for direct Coulomb explosion via a charge-resonance-enhanced ionization (CREI) mechanism. Observed charge-asymmetric dissociation (CAD) channels are marked with red circles, indicating the critical distance (Rcrit) for charge transfer via a classical over-the-barrier (COB) mechanism. Solid black arrows depict the CREI process leading to symmetric precursor states, while dashed black arrows depict the subsequent charge transfer (CT) process that converts a symmetric state into an asymmetric one. The condition Rcrit > Rc (satisfied for the channels shown) defines a geometrically allowed window where CT can occur prior to CREI-driven explosion, thereby governing the subset of CAD channels that become experimentally accessible.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study presents a combined experimental and theoretical investigation of the charge-asymmetric dissociation (CAD) dynamics in the heteronuclear diatomic molecule iodine bromide (IBr) driven by an intense femtosecond laser field. By employing dc-sliced velocity map imaging, we have identified multiple Coulomb explosion channels, encompassing both charge-symmetric (CSD) and charge-asymmetric (CAD) fragmentation pathways. The observed fragmentation patterns are explained by a unified sequential model that integrates charge-resonance-enhanced ionization (CREI) with classical over-the-barrier (COB) charge-transfer dynamics. Within this framework, the CREI mechanism governs the initial formation of highly charged symmetric precursor ions and determines the critical internuclear distance (Rc) for their subsequent Coulomb explosion. The key charge-redistribution step leading to the observed CAD channels is then described by the COB model, which defines a distinct charge-transfer critical distance (Rcrit). The empirical criterion for the emergence of a CAD channel, Rcrit > Rc, successfully accounts for the subset of asymmetric pathways observed in our experiments on IBr.

This analysis offers a systematic approach for unraveling charge-partitioning dynamics in heteronuclear diatomic systems, clarifying how the interplay between a geometry-dependent ionization mechanism and subsequent charge redistribution jointly governs the branching of strong-field dissociation channels. The elucidation of these dynamics in the prototypical molecule IBr thus provides a methodological framework and a useful reference for future studies. While validated here for IBr, the generality of this framework should be tested in systematic studies of other heteronuclear diatomics (e.g., ICl, BrCl, IF) and more complex molecular systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/photonics13020160/s1. Refs [33,34] are cited in the supplementary file.

Author Contributions

B.L. completed the experimental work and draft, and Z.L. finished part of theoretical calculation. The original experiment idea was proposed by Z.L., the experiments were designed by Z.L., and B.L. submitted the final manuscript for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by The Scientific Research Project for the Introduction of Talent of Yancheng Institute of Technology (No. xjr2021069), and The Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (No. 24KJB140020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Materials file.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yan Yang and Zhenrong Sun of East China Normal University for the experimental setup and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAD | Charge asymmetric dissociation |

| CSD | Charge symmetric dissociation |

| CREI | Charge-resonance-enhanced ionization |

| COB | Classical over-the-barrier |

References

- Krause, J.L.; Schafer, K.J.; Kulander, K.C. High-order harmonic generation from atoms and ions in the high intensity regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 3535–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macklin, J.J.; Kmetec, J.D.; Gordon, C.L. High-order harmonic generation using intense femtosecond pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 766–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, W.; Grasbon, F.; Kopold, R.; Milošević, D.B.; Paulus, G.G.; Walther, H. Above-Threshold Ionization: From Classical Features to Quantum Effects. In Advances in Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics; Bederson, B., Walther, H., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; Volume 48, pp. 35–98. [Google Scholar]

- Eberly, J.H.; Javanainen, J.; Rza̧żewski, K. Above-threshold ionization. Phys. Rep. 1991, 204, 331–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaggia, C.; Schmidt, M.; Normand, D. Laser-induced nuclear motions in the Coulomb explosion of C2H2+ ions. Phys. Rev. A At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1995, 51, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaggia, C.; Schmidt, M.; Normand, D. Coulomb explosion of CO2 in an intense femtosecond laser field. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1994, 27, L123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vager, Z.; Naaman, R.; Kanter, E.P. Coulomb explosion imaging of small molecules. Science 1989, 244, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, N.G.; McKenna, J.; Sayler, A.M.; Gaire, B.; Zohrabi, M.; Ablikim, U.; Carnes, K.D.; Ben-Itzhak, I. Charge asymmetric dissociation of a CO+ molecular-ion beam induced by strong laser fields. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 013418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, D.T.; Beaudoin, Y.; Dietrich, P.; Corkum, P.B. Optical studies of inertially confined molecular iodine ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 2755–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatherly, P.A.; Stankiewicz, M.; Codling, K.; Frasinski, L.J.; Cross, G.M. The multielectron dissociative ionization of molecular iodine in intense laser fields. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1994, 27, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seideman, T.; Ivanov, M.Y.; Corkum, P.B. Role of electron localization in intense-field molecular ionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torlina, L.; Ivanov, M.; Walters, Z.B.; Smirnova, O. Time-dependent analytical R-matrix approach for strong-field dynamics. II. Many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. A At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2012, 86, 043409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harumiya, K.; Kono, H.; Fujimura, Y.; Kawata, I.; Bandrauk, A.D. Intense laser-field ionization of H2 enhanced by two-electron dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 66, 043403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, M.; Gibson, G.N. Charge asymmetric dissociation induced by sequential and nonsequential strong field ionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, K.; Luk, T.; Solem, J.; Rhodes, C. Kinetic energy distributions of ionic fragments produced by subpicosecond multiphoton ionization of N2. Phys. Rev. A 1989, 39, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocharova, I.; Karimi, R.; Penka, E.F.; Brichta, J.-P.; Lassonde, P.; Fu, X.; Kieffer, J.-C.; Bandrauk, A.D.; Litvinyuk, I.; Sanderson, J. Charge resonance enhanced ionization of CO2 probed by laser Coulomb explosion imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 063201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavičić, D.; Kiess, A.; Hänsch, T.; Figger, H. Intense-Laser-Field Ionization of the Hydrogen Molecular Ions H2+ and D2+ at Critical Internuclear Distances. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 163002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, E.; Stapelfeldt, H.; Corkum, P. Observation of enhanced ionization of molecular ions in intense laser fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 76, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonti, V.; Chen, H.; Gibson, G. Multielectron effects in charge asymmetric molecules induced by asymmetric laser fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 073002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.N.; Li, M.; Guo, C.; Nibarger, J.P. Direct evidence of the generality of charge-asymmetric dissociation of molecular iodine ionized by strong laser fields. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 58, 4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, H.; Nakanaga, T.; Tachiya, M. Coherent control of photofragment separation in the dissociative ionization of IBr. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 113002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Shao, F.-W.; Fan, K.-N. Coherent control of the photodissociation of CH3I and IBr. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 329, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, H.; Nakanaga, T.; Arakawa, H.; Tachiya, M. The interference effects induced by two-color excitation in the photodissociation of IBr. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 363, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.N.; Roberts, G. Wave packet dynamics of IBr predissociation. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 2474–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, D.; Minitti, M.P.; Suits, A.G. Direct current slice imaging. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2003, 74, 2530–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppink, A.T.; Parker, D.H. Velocity map imaging of ions and electrons using electrostatic lenses: Application in photoelectron and photofragment ion imaging of molecular oxygen. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1997, 68, 3477–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Bandrauk, A.D. Charge-resonance-enhanced ionization of diatomic molecular ions by intense lasers. Phys. Rev. A 1995, 52, R2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryufuku, H.; Sasaki, K.; Watanabe, T. Oscillatory behavior of charge transfer cross sections as a function of the charge of projectiles in low-energy collisions. Phys. Rev. A 1980, 21, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, M.D. Supersonic beam sources. In Experimental Methods in the Physical Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 29, pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y. Multi-ionization of the Cl2 molecule in the near-infrared femtosecond laser field. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Z. Channel-resolved multiorbital double ionization of molecular Cl2 in an intense femtosecond laser field. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 043402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, Z. Dissociative ionization of CH2Br2 in 800 and 400 nm femtosecond laser fields. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 685, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramida, A.; Ralchenko, Y.; Reader, J.; NIST ASD Team. 2024. NIST Atomic Spectra Database (Version 5.12). Available online: https://physics.nist.gov/asd (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/pml/atomic-spectra-database (accessed on 26 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.