Abstract

The liquid diffusion coefficient is a critical parameter for studying mass transfer processes, calculating mass transfer rates, and facilitating chemical engineering design and development, with its value strongly influenced by factors such as temperature and concentration. Conventionally, determining the concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient relationship D(C) requires multiple measurements across various concentrations followed by fitting, which is time-consuming and prone to cumulative errors, especially under varying thermal conditions encountered in industrial applications. To address this limitation, this study proposes an optimized finite difference numerical method that enables rapid determination of D(C) using only a single diffusion image, significantly enhancing measurement efficiency. This approach was validated by comparison with the shift of equivalent refractive index slice method and ray-tracing simulations. Diffusion coefficients for β-alanine aqueous solutions at different concentrations were measured over the temperature range of 288.15 K to 318.15 K using both techniques. The results from the two methods showed excellent consistency, with diffusion coefficients well described by the Arrhenius equation across temperatures, allowing for the rapid derivation of activation energies. Numerical simulations based on the derived D(C) relationship yielded images that closely matched experimental observations, confirming the accuracy and reliability of the finite difference method. This innovative technique not only offers a streamlined pathway for characterizing concentration-dependent diffusion in amino acid systems like β-alanine—relevant to pharmaceutical and biochemical processes—but also demonstrates broad applicability for obtaining diffusion coefficients and activation energies with minimal experimental effort.

1. Introduction

β-type amino acids are the limiting amino acids for the synthesis of endogenous imidazole dipeptides in humans and mammals, which have functions such as increasing the content of imidazole dipeptides in muscles, enhancing antioxidant capacity, improving muscle buffering capacity, and providing anti-fatigue effects [1,2,3]. The speed of β-alanine molecular motion has a significant impact on these processes, and temperature is an important factor affecting the speed of molecular motion. Microscopically, diffusion is caused by the random thermal motion of particles. The diffusion coefficient is a physical quantity that characterizes the speed of diffusion and serves as important foundational data for studying mass transfer processes and calculating mass transfer rates [4,5,6]. Therefore, investigating the diffusion coefficients of β-alanine molecules at different concentrations and temperatures is of great significance. Currently, diffusion coefficients are mostly measured experimentally, for example, using the Taylor dispersion method [7,8], the diaphragm cell method [9,10], optical interferometry [11,12], and so on [13]. The diffusion coefficient D can be regarded as a constant in infinitely dilute solutions, but when the concentration gradient in the solution is high, the diffusion coefficient D becomes a function of the solution concentration C and is no longer a constant [14,15,16,17,18]. The aforementioned methods can only measure the diffusion coefficient at a specific temperature and fixed concentration and cannot directly determine the relationship between the diffusion coefficient and concentration.

To address the limitations of traditional methods, this paper employs a method based on finite-difference numerical calculation [19] to measure the diffusion coefficients D(C) of β-alanine aqueous solutions at different concentrations within the temperature range of 288.15–318.15 K. To verify the accuracy of the results, the shift of equivalent refractive index slice method [20,21] and the ray tracing numerical simulation method were, respectively, used to validate the experimental results. The outcomes indicate that the liquid-phase diffusion coefficients obtained from the two methods are in close agreement and consistent with literature values, while the simulation results align well with the experimental images. The finite difference numerical calculation comparison method not only enables the rapid and accurate measurement of diffusion coefficients for β-alanine aqueous solutions at different temperatures and concentrations but also allows for the determination of the diffusion activation energy.

2. Experimental Principles and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Experimental Setup and Imaging Principle

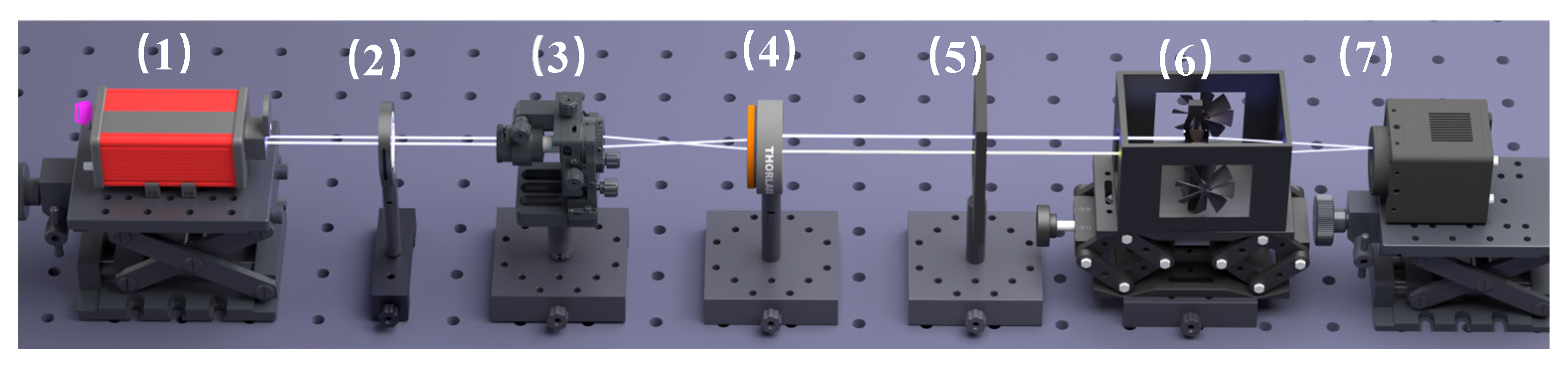

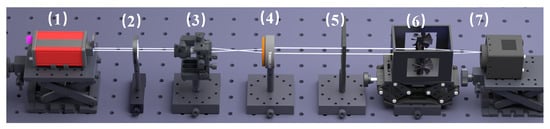

The experimental setup is shown in Figure 1. A semiconductor laser (λ = 589.0 nm) passes through an attenuator, beam expander collimation system, and limiting slit (13.0 mm) to obtain a monochromatic parallel light source of a certain width. The asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens (ALCL) is mounted within the temperature control device of the liquid-phase diffusion coefficient measurement system (precision ± 0.1 K). The monochromatic parallel light source vertically incident on the ALCL through the viewing window of the temperature control system. The ALCL has four surface radii of curvature (distance from the lens surface to its center of curvature): R1 = 32.0 mm, R2 = 24.0 mm, R3 = 34.7 mm, R4 = 79.5 mm. The wall thicknesses (axial thickness of the lens element) and distances from the center point of the lens are d1 = d4 = 3.0 mm, d2 = 1.8 mm, d3 = 1.2 mm. The lens material is K9 glass (n0 = 1.5163), and the length is 50.0 mm [19]. The monochromatic parallel light source is imaged on the CMOS detector after passing through the ALCL, and the detector is connected to a computer as the image acquisition and display system.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the experimental facility. 1: Laser; 2: Attenuator; 3: Spatial filter; 4: Lens; 5: Temperature control device for liquid-phase diffusion coefficient measuring instrument and asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens; 6: Asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens; 7: Image acquisition system.

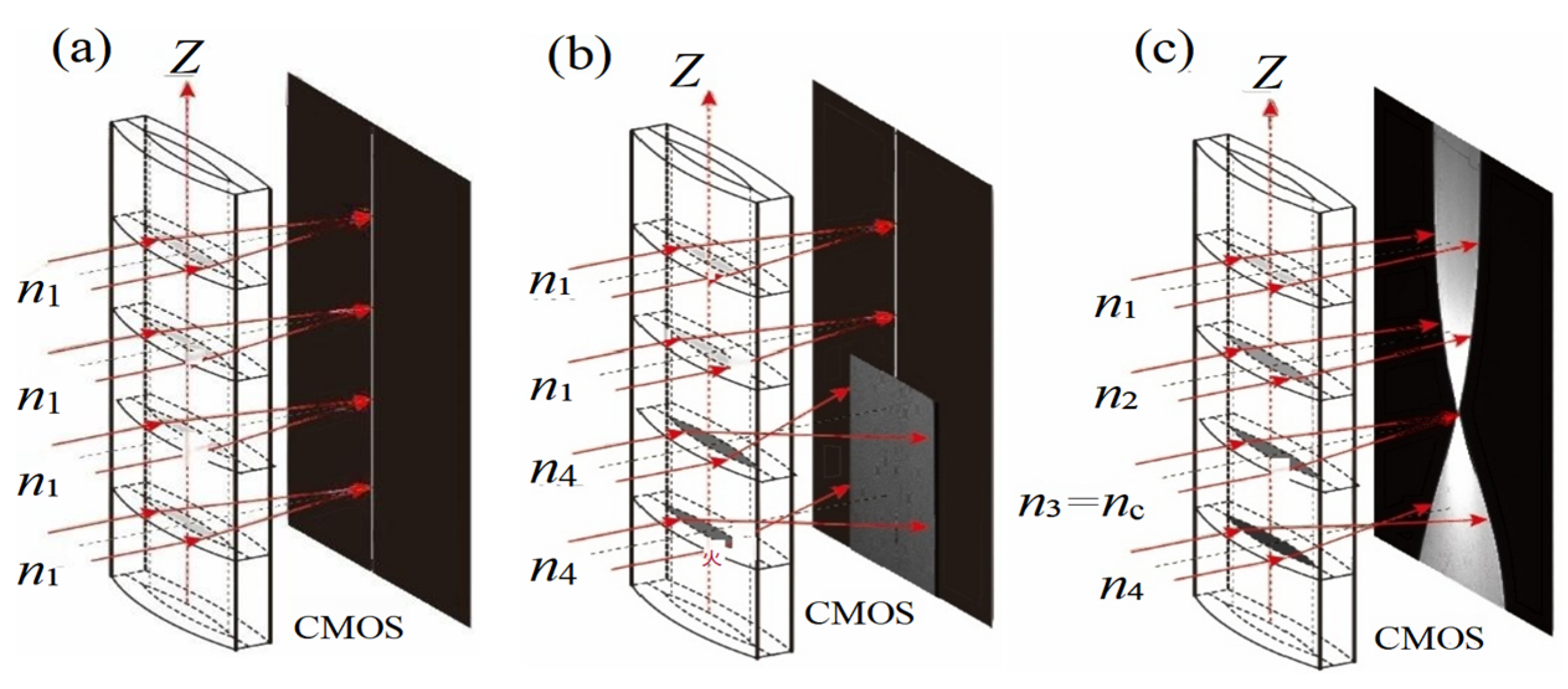

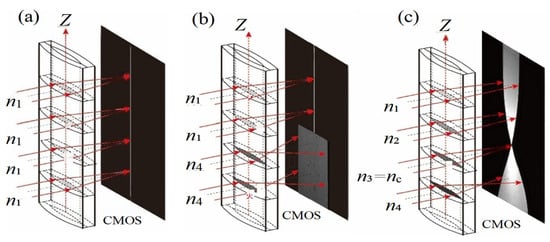

The imaging principle of the ALCL [19] is illustrated in Figure 2. When a solution with a single refractive index n1 is injected into the ALCL, the incident monochromatic parallel light converges after vertically entering the cylindrical lens. The position of the CMOS detector is adjusted back and forth; when the CMOS is positioned at the image-side focal plane of the cylindrical lens, a sharp bright line, as shown in Figure 2a, is captured. When two solutions with refractive indices n1, n4 (n1 ≤ n4) are sequentially injected into the ALCL, the resulting image is as shown in Figure 2b. Upon contact between the two liquids, diffusion occurs, forming a concentration gradient distribution along the Z-direction of the cylindrical lens. The CMOS position is then adjusted such that the refractive index layer RI = nc is clearly imaged on the CMOS. The other refractive index layers, due to under-focusing (n < nc) or over-focusing (n > nc), form blurred images resembling beam waists, as depicted in Figure 2c. As diffusion progresses, both the diffusion image and the beam waist evolve. By recording and analyzing the diffusion images, the diffusion coefficient can be determined.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the imaging principle of the asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens. (a) Imaging of a single solution; (b) Imaging of two different solutions; (c) Imaging after formation of a concentration gradient along the Z-axis (n1 < n2 < n3 = nc < n4).

2.2. Theoretical Basis for the Shift of Equivalent Refractive Index Slice Method

The diffusion of a binary solution along the axial direction of the ALCL (defined as the Z-axis) obeys Fick’s second law [20]. Prior to the onset of diffusion (t ≤ 0), the initial concentrations of the diffusing solutions on either side of the interface (at Z = 0) are C1 and C2, respectively. When the concentration difference between the two solutions is relatively small, the concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient D(C) can be approximated as a constant D0. Under this condition, the analytical solution to Fick’s second law can be expressed in terms of the following error function:

where denotes the Gaussian error function. The relationship between the solution concentration and refractive index, n(C), is experimentally determined prior to the measurements .

With the CMOS detector position fixed to ensure clear imaging of the refractive index layer (RI = nc), the beam waist corresponding to this fixed refractive index nc in the diffusion image undergoes temporal drift as diffusion proceeds. By recording the beam waist positions (Zi) at various time points (ti) during the diffusion process and performing a linear fit of Zi versus , the relationship can be expressed as . The diffusion coefficient D0 is then obtained by applying the inverse error function to Equation (1) [21]:

To determine the diffusion coefficients at different concentrations, the upper-layer solution is replaced with one corresponding to the desired concentration, thereby yielding the concentration-specific diffusion coefficient for practical applications. This approach not only simplifies the measurement but also enhances the accuracy by leveraging the established n(C) calibration curve to map refractive index profiles back to concentration distributions.

2.3. Theoretical Basis for the Finite Difference Numerical Calculation Method

When the concentration difference between the two solutions is large, the diffusion coefficient D generally depends on the concentration C and can be expressed in polynomial form (3) [19],

where k1, k2, k3… are undetermined coefficients, and D0 represents the diffusion coefficient under conditions of infinite dilution. In this case, Fick’s second law can be expressed as Equation (4),

By discretizing Equation (4), a system of linear equations is obtained and solved using the tridiagonal matrix algorithm (Thomas algorithm). The optimal D(C) is determined by iteratively adjusting the coefficients in the polynomial D(C), comparing the numerical concentration profile Cn(zj, t0) with the experimental concentration profile Ce(zj, t0), and minimizing the standard deviation δx.

This method is based on the finite difference principle, and detailed numerical procedures can be found in reference [19].

3. Data Analysis and Results

The diffusion coefficients of β-alanine aqueous solutions at temperatures ranging from 288.15 K to 318.15 K were measured using the “finite difference numerical calculation comparison method” and the “shift of equivalent refractive index slice method.” For both methods, the measurement procedure first involves establishing the relationship between the concentration C and refractive index n of β-alanine aqueous solutions at different temperatures, enabling the calculation of concentrations corresponding to selected thin-layer refractive indices.

Twelve sets of β-alanine aqueous solutions with varying molar concentrations were prepared at room temperature using β-alanine (Hefei Bomei Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hefei, China; analytical grade, purity ≥ 99%) and homemade deionized water. The refractive indices of these prepared solutions were measured at different temperatures using an Abbe refractometer (precision 0.0002). Linear relationships between the solution concentration C and refractive index n at various temperatures were subsequently fitted, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The relation between the concentration and refractive index of β-alanine aqueous solution at different temperatures.

3.1. Measurement Results Using the Shift of Equivalent Refractive Index Slice Method

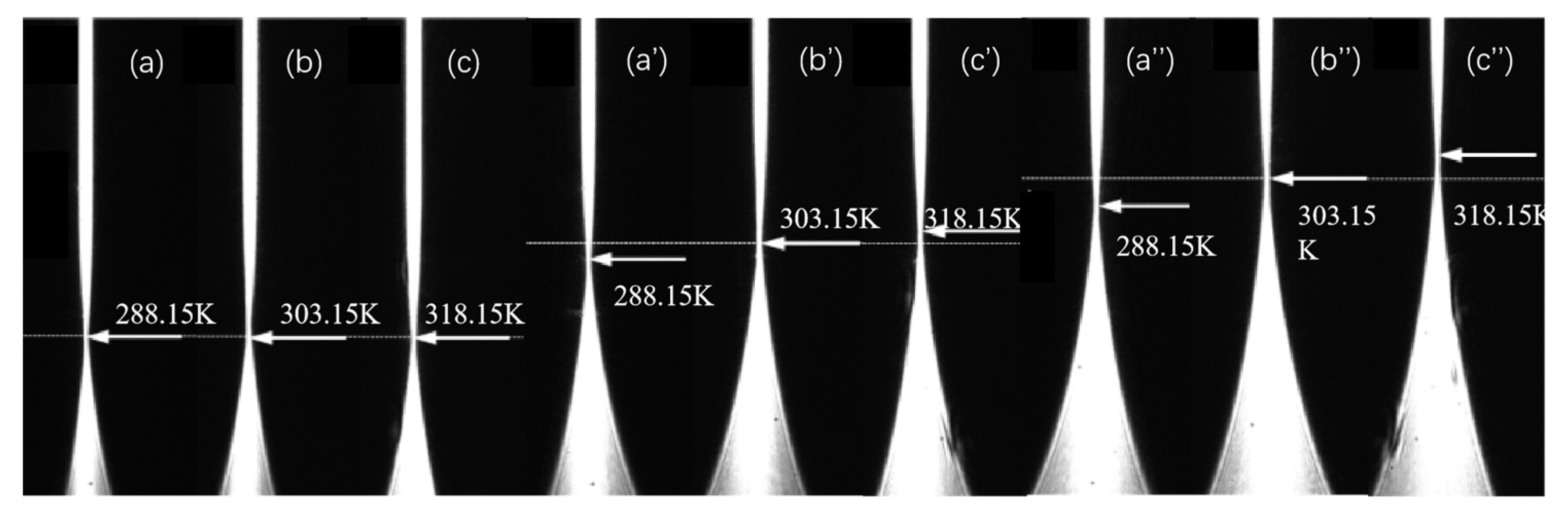

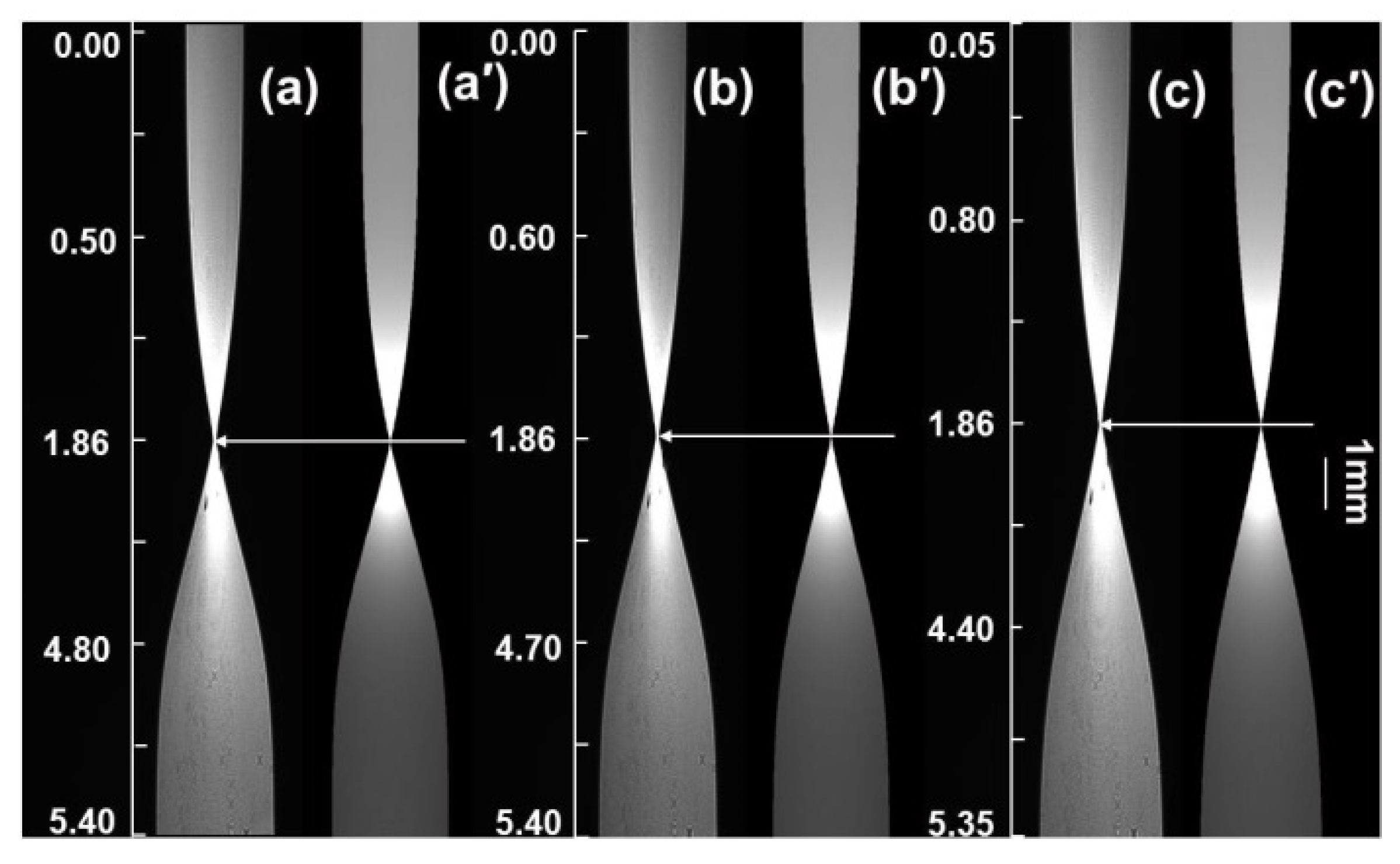

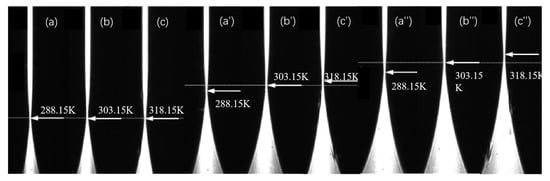

As an illustrative example, the procedure for measuring the infinite dilution diffusion coefficient at 298.15 K is described as follows. The temperature control unit of the liquid-phase diffusion coefficient measurement system is activated and set to the target temperature, with a preheating period of 3–5 min. Concurrently, the target solution (the upper solution in the diffusion cell) is placed in the temperature control system to equilibrate to the set temperature. Using a digital syringe pump, a high-concentration β-alanine aqueous solution (5.4 mol/L) is slowly injected into the cylindrical lens up to approximately half its height. After a static settling period of 600 s (to minimize turbulence induced by injection and stabilize the set temperature), the upper target solution—pure water—is slowly injected. Therefore, at t = 0, the initial state of the two-liquid mixture can be considered such that their concentrations remain at their respective initial values C1 and C2. In accordance with the liquid thin-layer selection principle [22,23], the refractive index layer RI = nc = 1.3348 (corresponding to a β-alanine concentration of 0.0745 mol/L) is positioned for clear imaging. Following an additional stabilization period of 10–20 min at the set temperature, diffusion images are acquired at 2 min intervals. Under identical temperature conditions, representative diffusion images captured at various time points are shown in Figure 3 (displaying selected experimental images only), where the beam waist of the diffusion image exhibits temporal drift.

Figure 3.

Diffusion images of infinitely dilute β-alanine aqueous solution at different times. (a–c): 1200; (a′–c′): 2400; (a″–c″): 3600 s.

The positional drift of the beam waist Zi with respect to time ti during the diffusion process is recorded. A linear fit is performed using the least-squares method on Zi versus yielding: Zi = + b. Substituting C1 = 0 mol/L, C2 = 5.4 mol/L, and the corresponding thin-layer concentration of 0.0745 mol/L into Equation (2) results in an infinite dilution diffusion coefficient for the β-alanine aqueous solution at 298.15 K of D0 = 0.92 × 10−5 cm2/s, with a relative error of 1.9% compared to the literature value [24].

The infinite dilution diffusion coefficients of β-alanine aqueous solutions were similarly measured across the temperature range of 288.15–318.15 K by selecting appropriate positions for the near-infinite-dilution thin-layer refractive index. Transient diffusion images acquired at different time points for measurements at selected temperatures (e.g., 288.15 K, 303.15 K, and 318.15 K) are presented in Figure 3. As evident from the figure, the drift velocity of the beam waist in the diffusion images varies with temperature: higher temperatures correspond to faster drift rates, indicating accelerated diffusion and thus larger diffusion coefficients. This behavior arises because elevated temperatures enhance the speed of random thermal motion of molecules, thereby accelerating the overall diffusion process.

Using the same method, the diffusion coefficients of β-alanine aqueous solutions with target solution concentrations of infinite dilution, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mol/L were measured across the temperature range of 288.15 K to 318.15 K (all values represent the averages of five replicate experimental measurements). The infinite dilution results at different temperatures exhibit close agreement with literature values [24]. The measurement results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The results of diffusion coefficients of β-alanine aqueous solution at different temperatures and concentrations. Units: D*10−5 (cm2/s).

3.2. Measurement of the D(C) Relationship Using the Finite Difference Numerical Calculation Comparison Method

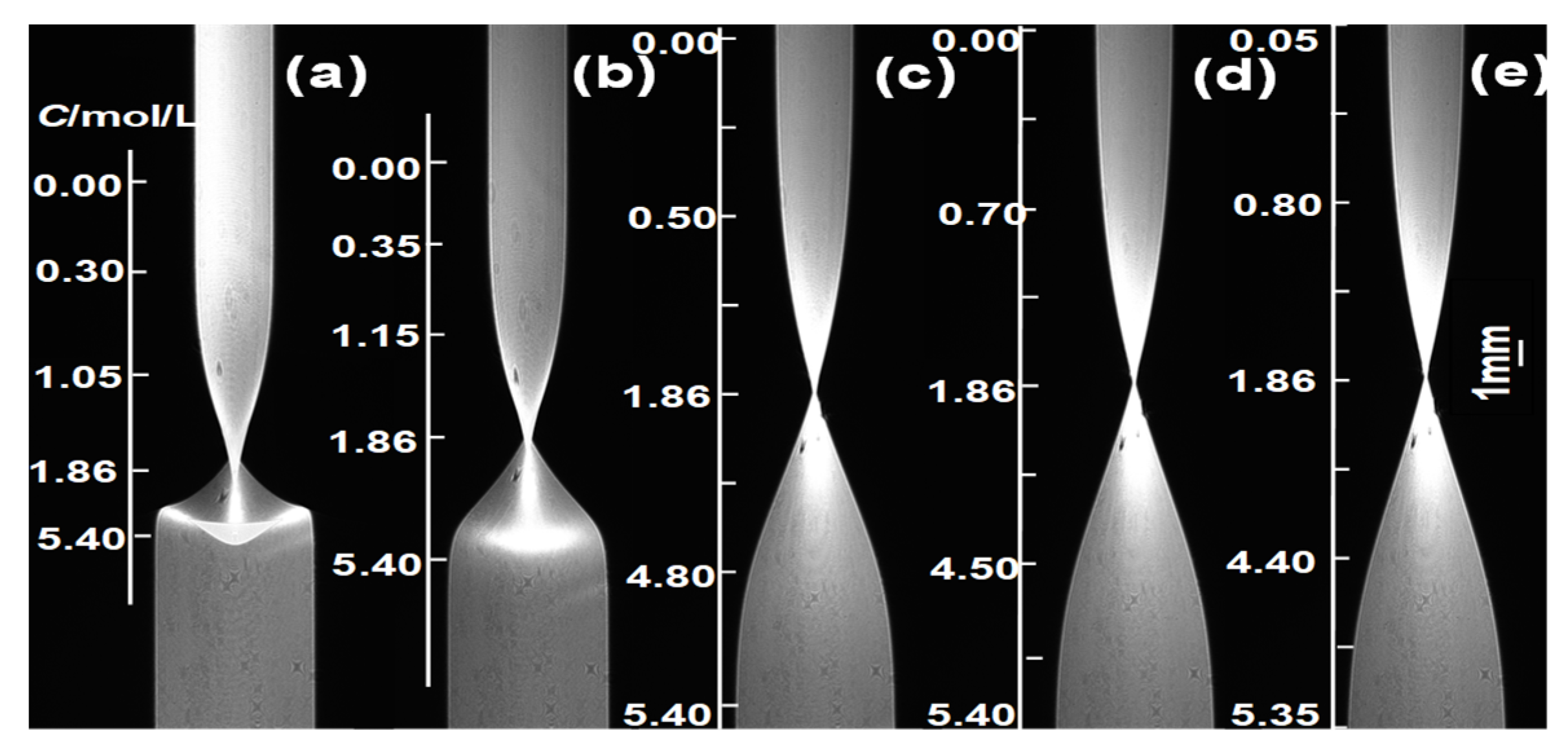

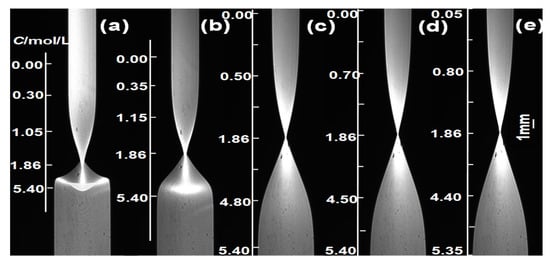

Following the experimental procedure described above, pure water (C1 = 0) was injected into the upper part of the lens, and an aqueous solution of β-alanine (C2 = 5.4 mol/L) was injected into the lower part. Clear imaging was achieved on the CMOS at RI = nc = 1.3616 (using the experimental temperature of 298.15 K as an example), with a diffusion image recorded every 10 min. Selected images are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Diffusion images taken at different diffusion times (at 298.15 K). (a) 40; (b) 80; (c) 240; (d) 360; (e) 420 min.

From the diffusion images in Figure 4, it can be observed that in the early-stage diffusion images, the large concentration gradient causes light ray deflection, resulting in deformation of the interface region, which is primarily distributed at the contact surface between the two diffusing solutions. When t ≥ 360 min, the diffusion images no longer satisfy the boundary calculation conditions of the finite difference numerical calculation comparison method (i.e., bottom C = C2 = 5.4 mol/L, top C = C1 = 0 for the diffusion images [19]). Therefore, diffusion images collected at diffusion times of 240 min ≤ t ≤ 360 min were selected to calculate the D(C) relationship.

As shown in Figure 2b, different refractive indices correspond to different image widths on the CMOS. To determine the relationship between the experimental image width and the refractive index, this study employed an experimental calibration method. First, liquid solutions with varying refractive indices were prepared, and the position of the CMOS was adjusted to achieve clear imaging on the CMOS when RI = nc = 1.3616 (using the experimental temperature of 298.15 K as an example; the position for clear CMOS imaging was determined by the refractive index of the “waist” pairs in diffusion images at different temperatures). The prepared solutions were then injected into the ALCL separately, and the images were recorded. Due to under-focusing or over-focusing of the refractive index thin layer on the CMOS image, which forms blurred images as shown in Figure 2b, the recorded image width Wi (in μm) on the CMOS surface was linearly fitted using a piecewise function for the injected liquid’s refractive index when n ≤ nc and n > nc, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The fitting relationship between refractive index and width at different temperatures.

R2 is the coefficient of determination, which is used to measure the goodness of fit for the piecewise function relationship between the refractive index and the image width.

Using the experimentally measured n-Wi relationship and C-n relationship, the relationship between concentration C and diffusion image width Wi was calculated. The diffusion images were processed to extract the widths of the diffusion images at different positions. Based on the C-Wi relationship, the experimental concentration distribution Ce(Zj, t) from the diffusion images was obtained.

When the diffusion coefficient is concentration-dependent, D(C) is expressed as the polynomial in Equation (3), where the infinite dilution diffusion coefficient D0 = 0.9360 × 10−5 cm2/s for the β-alanine aqueous solution was calculated using the shift of equivalent refractive index slice method. Since the coefficients for terms beyond the cubic order in concentration in the D(C) expression are small, only coefficients up to the cubic term were considered. Thus, the undetermined coefficients [k1, k2, k3] were computed using the finite difference numerical calculation comparison method. A set of initial parameters [k1, k2, k3] was iteratively calculated to determine D(C). The numerical concentration spatial distribution Cn(Zj, t) was then computed from D(C). The corresponding computed concentration spatial distribution Cn(Zj, t) was compared with the experimental curve Ce(Zj, t) (j = 0, 1, 2, …, M + 1), and the standard deviation δx, as defined in Equation (7), was calculated. By varying [k1, k2, k3], a series of δx values (x = 2, 3, …, N) was obtained. The [k1, k2, k3] values corresponding to the minimum δx were selected as the optimal parameters.

To obtain a stable polynomial D(C), diffusion images at 8 time points were analyzed, from 290 min to 360 min at 10 min intervals. The computed results for the sets of undetermined parameters [k1, k2, k3] are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The calculated values of undetermined coefficients of the D(C) polynomial over a diffusion period from 290 to 360 min at 298.15 K. Unit: D/×10−5 cm2·s−1/.

Under the condition of 298.15 K, the diffusion coefficients corresponding to concentrations were calculated based on the D(C) relationships from the eight time points. The resulting diffusion coefficients were stable (standard deviation ≤ 0.01 × 10−5 cm2/s). Therefore, the average of the undetermined parameters from these eight time points was taken as the optimal undetermined coefficients at this temperature, namely k1 = −0.0886, k2 = −0.0005, and k3 = −0.0001. Using the above method, the D(C) relationship for β-alanine at temperatures ranging from 288.15 K to 318.15 K was calculated, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

D(C) relationship from 288.15 K to 318.15 K.

3.3. Comparison of Measurement Results from the Two Methods

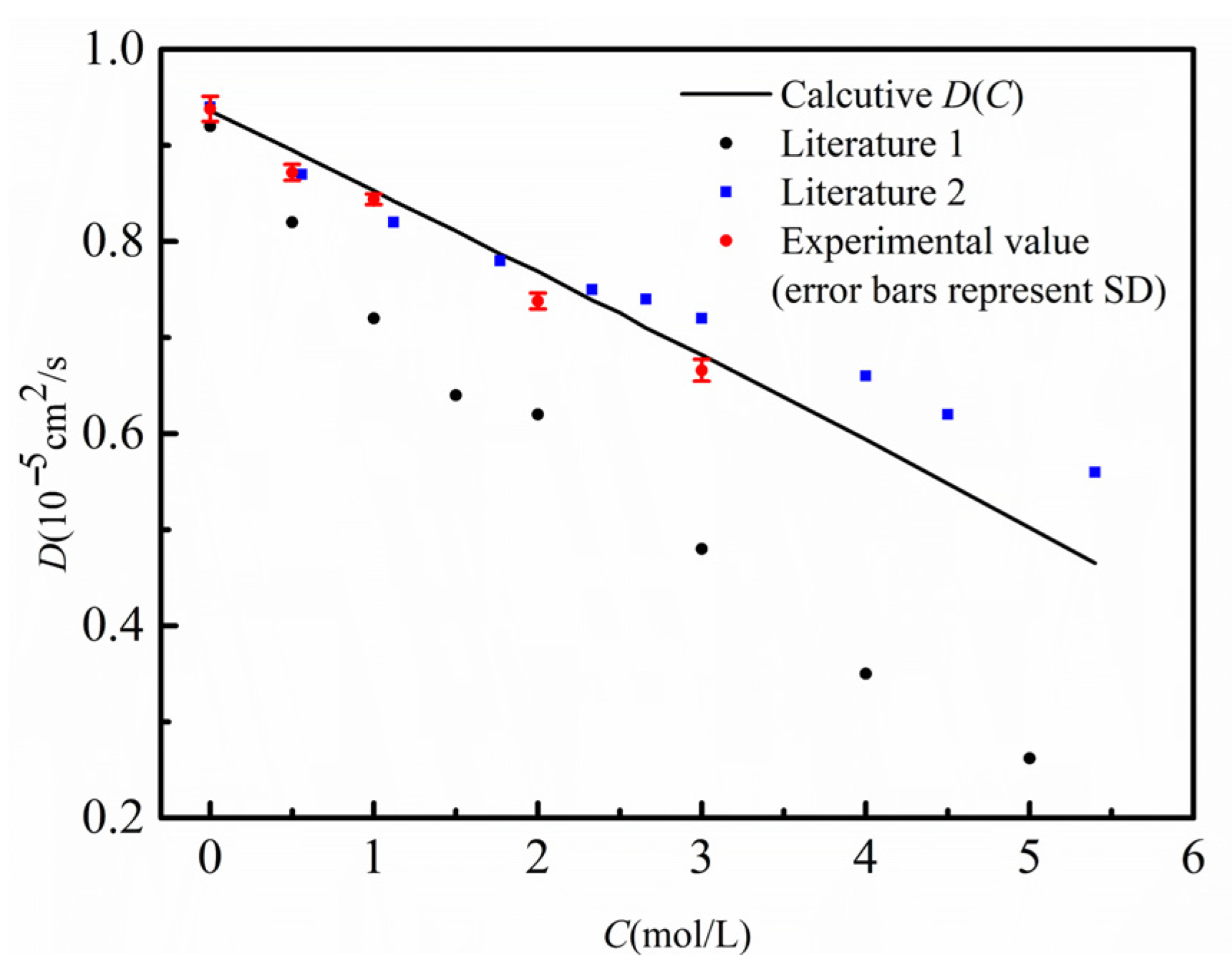

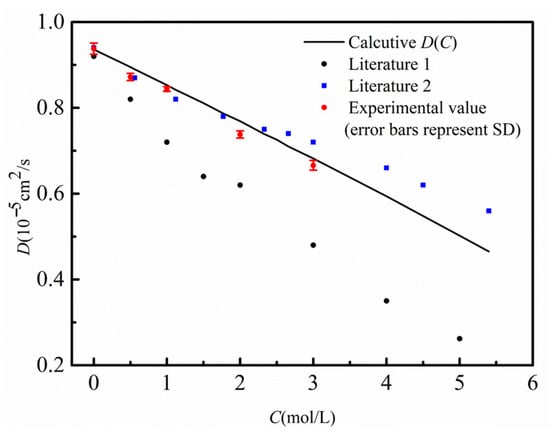

To verify the reliability of the concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient D(C) obtained by the finite difference numerical calculation comparison method, its results were compared with the measurement results from the research group’s equivalent refractive index thin-layer shift method, as well as with literature data.

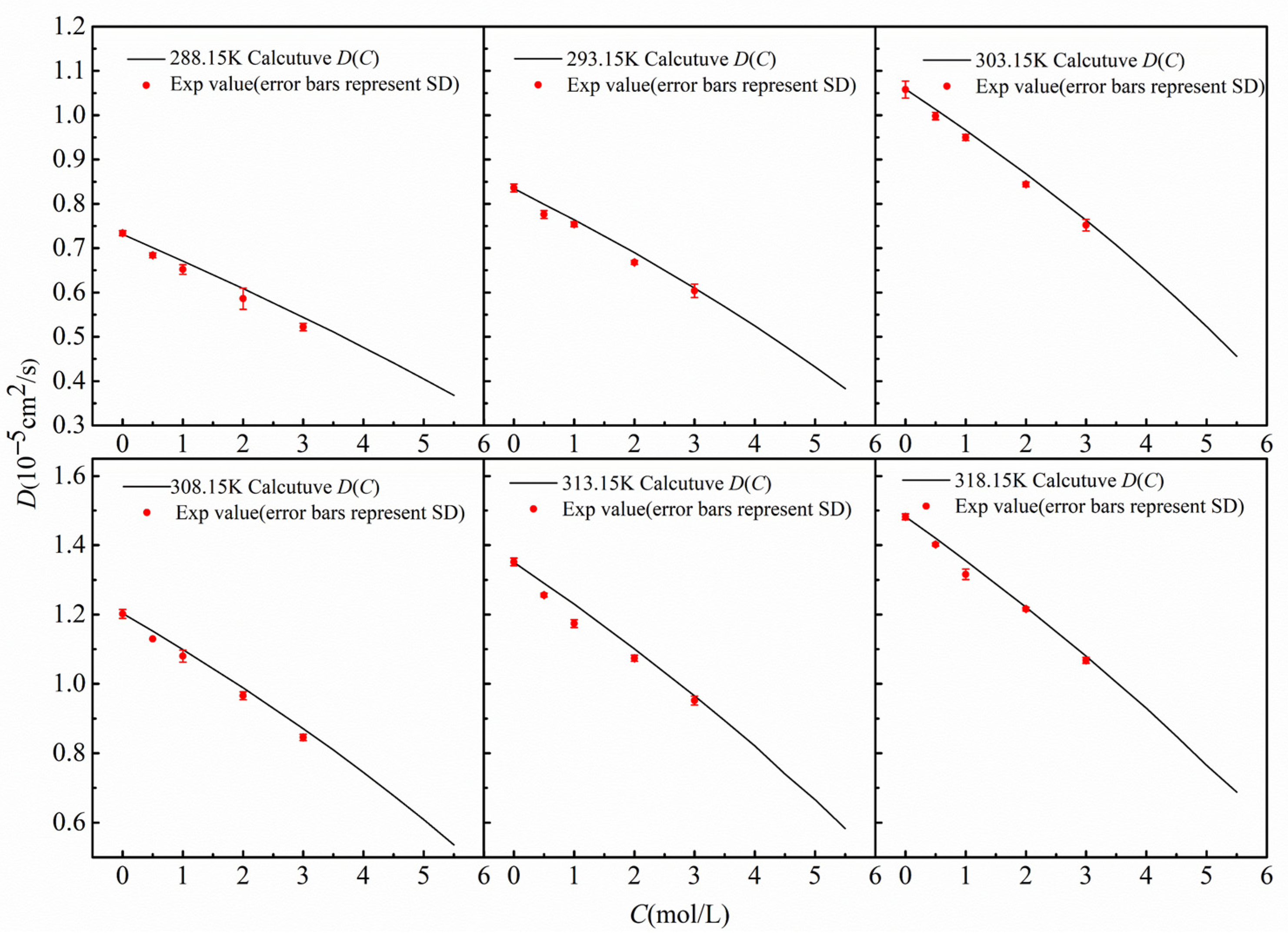

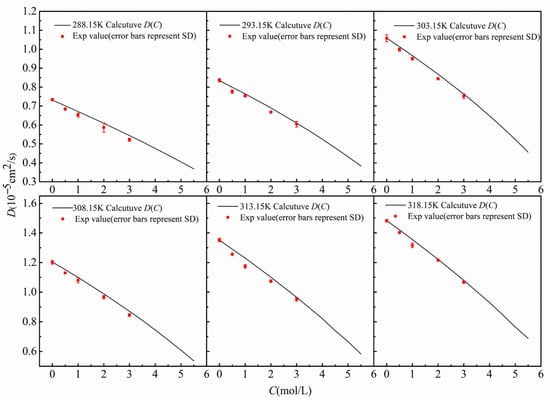

As shown in Figure 5, at 298.15 K, the D(C) curve obtained by the finite-difference numerical calculation comparison method (black solid line), the diffusion coefficients at multiple concentration points measured by the shift-of-equivalent-refractive-index-slice method (red dots), and the data reported in the literature are in good agreement, with the results closely matching the literature values [25]. To examine the applicability of the method over a wide temperature range, Figure 6 further compares the measurement results of the two methods at different temperatures from 288.15 K to 318.15 K. A comprehensive analysis indicates that within the temperature range of 288.15 K to 318.15 K, the diffusion coefficients obtained by the two methods are highly consistent, which strongly validates that the finite-difference numerical calculation comparison method—based on the inversion of a single diffusion image for D(C)—possesses correct measurement accuracy and good reliability.

Figure 5.

Comparison chart of measured diffusion coefficients at different concentrations with literature values. The black solid line represents the D(C) curve calculated by the finite difference method in this work; the red dots denote the experimentally measured D values at different concentrations; the blue box represents the literature value 1 [25]; the black dots represent the literature value 2 [26].

Figure 6.

Diffusion coefficients varying with concentration at different temperatures.

3.4. Dependence of Diffusion Coefficient on Temperature

The relationship between the diffusion coefficient and temperature follows the Arrhenius equation [27,28,29,30],

where R is the molar gas constant; T is the temperature in K; and Ea represents the activation energy for diffusion, which is the energy required for the diffusion of 1 mol of particles. Within a narrow temperature range, this value can be considered constant.

Taking the natural logarithm of the Arrhenius Equation (6) yields:

where A is the pre-exponential factor.

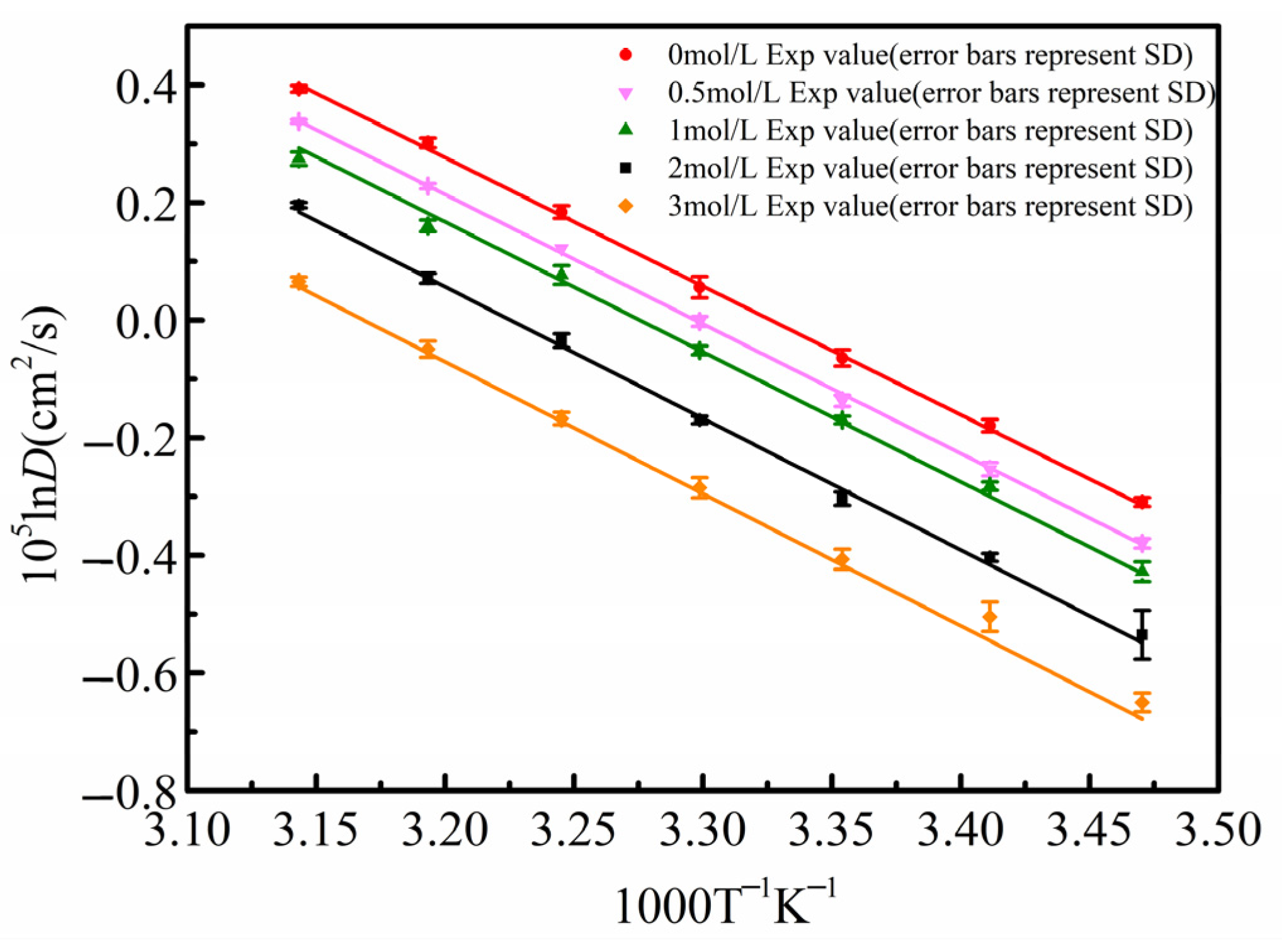

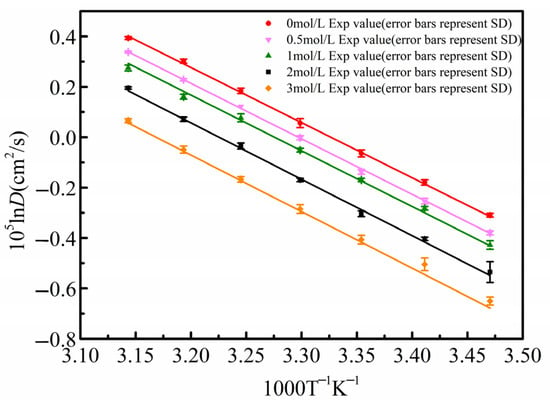

The diffusion coefficient results for β-alanine aqueous solutions at different concentrations from 298.15 K to 318.15 K, as listed in Table 2, were fitted using the Arrhenius equation. In Figure 7, the solid points represent the experimentally measured diffusion coefficients, where the error bars indicate the standard deviation from five repeated experiments, with a relative standard deviation of less than 2% for all data points, and the solid line is the linear fit of ln(D) versus 1/T.

Figure 7.

Arrhenius plot of β-alanine diffusion coefficients from 298.15 K to 318.15 K.

From Figure 7, it can be observed that for the same concentration of β-alanine aqueous solution, the diffusion coefficient increases with rising temperature. Moreover, the diffusion coefficients at different temperatures fit well with the Arrhenius relationship, confirming the stability and reliability of the measurement results. Additionally, the calculated activation energy Ea can be used to determine the diffusion coefficients at different temperatures.

The fitted Arrhenius equations for different concentrations, along with their coefficients, are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Arrhenius formula coefficients of diffusion coefficients of β-alanine aqueous solutions at different concentrations.

R2 is the coefficient of determination, which quantifies the goodness of fit for the relationship between ln(D) and 1/T.

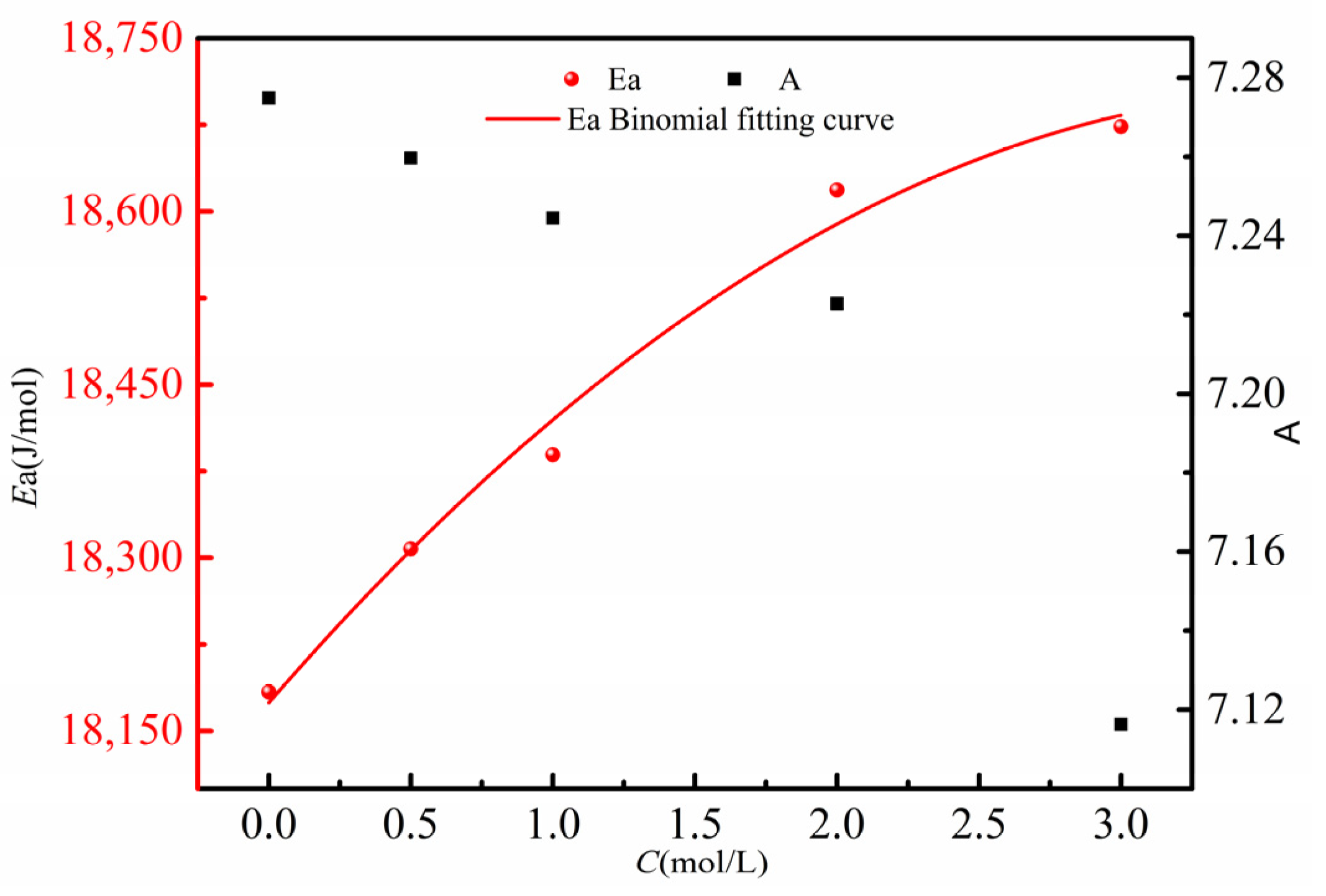

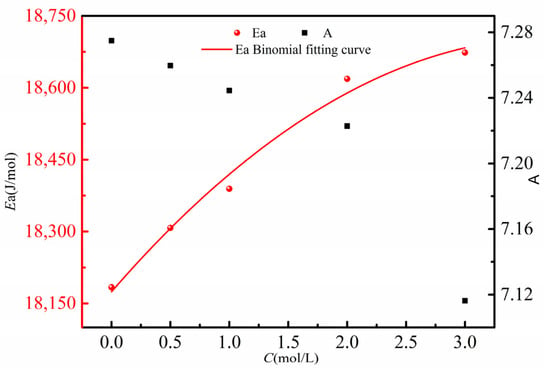

Fitting the activation energies Ea (red circles) corresponding to different concentrations from Table 6, along with the pre-exponential factor A (black squares), yields the curves shown in Figure 8. From Figure 8, it can be observed that as the concentration of the β-alanine aqueous solution increases, the corresponding diffusion activation energy Ea increases, while the pre-exponential factor A decreases. This indicates that diffusion of high-concentration β-alanine molecules from the aqueous solution into the 5.4 mol/L β-alanine aqueous solution becomes more difficult. This phenomenon arises from the increased molecular density in the β-alanine aqueous solution, which correspondingly elevates the energy required for molecules to escape from the high-concentration region. Consequently, this explains the observed decrease in the diffusion coefficient of the β-alanine aqueous solution with increasing concentration.

Figure 8.

Relationship between diffusion activation energy Ea of different concentrations of β-alanine aqueous solution and pre-exponential factor A.

Performing a quadratic fit on the five sets of experimentally calculated diffusion activation energies Ea and concentration C data, as indicated by the red solid line in Figure 8, yields the following relationship between the diffusion activation energy Ea and concentration C:

Based on this relationship (correlation coefficient R2 = 0.9885, which is used to measure the goodness of fit of the quadratic fitting relationship between the diffusion activation energy Ea and concentration C), the diffusion activation energy for β-alanine aqueous solutions at different concentrations can be calculated. These values can then be used to determine the diffusion coefficients at various temperatures.

3.5. Simulation Results of Diffusion

To verify the accuracy of the experimental results, ray tracing [19] was employed to simulate the diffusion process within the asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens under the same conditions. The CMOS used in the experiment has dimensions of 6576 pixels × 4384 pixels, with each pixel measuring 5.5 μm × 5.5 μm. Using MATLAB (R2023a), a 13 mm wide parallel beam was simulated to be vertically incident on the central liquid region of the asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens. The positions where the rays passing through the liquid thin layers in the asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens intersect the CMOS were tracked, and the light intensity distribution on the CMOS was obtained by accumulating the number of rays incident on it.

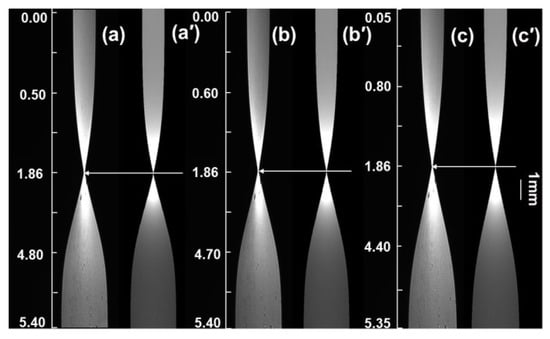

As an example, for the measurement of diffusion in β-alanine aqueous solution at 298.15 K, the CMOS was fixed at the position for clear imaging of the liquid thin layer with a refractive index of 1.3616. The simulated images based on the D(C) relationship calculated using the finite difference numerical calculation comparison method are shown in Figure 9a′–c′.

Figure 9.

Comparison of experimental diffusion and simulated diffusion images at the thin layer of refractive index 1.3616. (a–c): 210, 300, and 420 min experimental images; (a’–c’): corresponding simulated images.

From Figure 9, it can be observed that when simulating using the D(C) relationship derived from the finite difference numerical calculation comparison method, the drift rate of the “waist” in the β-alanine simulated images is essentially consistent with that of the experimental images, and the contours of the simulated images closely match those of the experimental images. The simulated images further validate the accuracy and reliability of the D(C) relationship obtained from the finite difference numerical calculation comparison method.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper introduces a method termed the “finite-difference numerical calculation comparison method” for rapidly measuring concentration-dependent diffusion coefficients, D(C). The core of this approach lies in integrating the optical imaging capabilities of an asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens (ALCL) with finite-difference method (FDM) numerical computation. Using the ALCL, we can acquire the spatiotemporal concentration distribution of a solution in a non-invasive, full-field, and real-time manner from a single diffusion experiment. Subsequently, by solving Fick’s second law with variable coefficients via FDM, we inversely derive the relationship between the diffusion coefficient and concentration, D(C). To validate the reliability of this method, we concurrently employed the “shift of equivalent refractive index slice method” for comparative measurements and conducted comprehensive ray-tracing simulations. Both approaches confirmed that the data obtained using the new method are stable and credible. In this study, the method was applied to the β-alanine aqueous solution system. The diffusion coefficients at various concentrations were systematically measured within the temperature range of 288.15 K to 318.15 K. Experimental results show that the diffusion data at each temperature adhere well to the Arrhenius relationship, allowing the determination of the diffusion activation energy, Ea, through fitting. Further analysis reveals a significant quadratic dependence between Ea and concentration C: Ea = −37.702C2 + 282.72C + 181,174. The establishment of this empirical formula enables the prediction of the diffusion activation energy based solely on concentration.

Compared with traditional measurement methods, the proposed approach offers distinct advantages. Unlike diaphragm cell or holographic interferometry methods, which require multiple experiments at different concentrations, this method reconstructs the complete D(C) relationship across the entire concentration range using only a single experiment and one diffusion image, significantly enhancing measurement efficiency. Furthermore, in contrast to earlier methods developed by the research group, such as the equal-refractive-index thin-layer tracking method, the transient method [31], the equal-height method [32], and the equal-width method [33]—all of which are theoretically based on the assumption of a constant diffusion coefficient—this method overcomes the limitations of “infinitely dilute solutions” or “narrow concentration ranges.” It accurately handles real systems where the diffusion coefficient varies significantly with concentration, representing a crucial methodological advancement.

The impact and significance of this work are primarily reflected in three aspects. First, it systematically obtained a comprehensive D(C, T) dataset for β-alanine aqueous solutions across wide temperature and concentration ranges, providing essential fundamental property data for its applications in related fields. Second, the method establishes an efficient measurement paradigm, enabling researchers to rapidly and directly obtain diffusion coefficients at any concentration. Additionally, the derived Ea(C) relationship allows reliable extrapolation to other temperatures, significantly reducing the burden of tedious experimental work. Finally, this method offers a powerful and versatile tool for studying diffusion behaviors in non-ideal solutions, complex mixtures, and even biological systems.

Beyond its technical merits, this approach holds transformative potential for interdisciplinary applications. In pharmaceutical sciences, it could accelerate the optimization of β-alanine-based drug formulations by quantifying diffusion kinetics in hydrogel matrices or transdermal patches, informing controlled-release profiles. In electrochemical engineering, the method’s sensitivity to concentration gradients enables real-time monitoring of ion transport in batteries or fuel cells, aiding the design of high-efficiency electrolytes. For biomolecular studies, it offers a non-invasive tool to probe protein–solute interactions in crowded cellular environments, bridging gaps in understanding amyloid aggregation or enzyme kinetics. However, despite these advances, comprehensive characterization across multiple concentrations, time points, and temperatures still demands iterative experiments, which can accumulate significant time and resource costs in high-throughput scenarios. To overcome this limitation, future investigations could harness machine learning techniques—already demonstrated in optical detection domains for tasks like automated image segmentation, lidar [15,34,35]—to enable end-to-end automation. For instance, convolutional neural networks could directly infer D(C) from raw CMOS images, while Gaussian processes or recurrent models might forecast multi-temperature behaviors from sparse datasets, drastically reducing experimental demands. Extending this versatility, such integrations may adapt the framework to multicomponent mixtures (e.g., amino acid cocktails) and non-aqueous media (e.g., ionic liquids), unlocking applications in green chemistry and advanced materials synthesis. Ultimately, this work not only furnishes the first comprehensive D(C, t) dataset for β-alanine but also pioneers a scalable paradigm for diffusion metrology, poised to influence predictive modeling in mass transfer-dominated processes across chemical and biological engineering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M.; methodology, B.G.; software, X.C.; data curation, B.G., X.C. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M.; writing—review and editing, W.M. and X.P.; funding acquisition, W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 12164053) and Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project of Yunnan Province of China (Grant No. 202401AT070466, 202202AG070002, 202503AP140018).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xinfei Cao was employed by the company Yunnan Beifang Photo-Electric Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Saffioti, N.R.; Paul, S.; Farias, L.O.D.; da Silva, R.P.; Silva, V.d.E.; Nemezio, K.; Yamaguchi, G.; Artioli, G.G.; Gualano, B.; Saunders, B.; et al. The Muscle Carnosine Response to Beta-Alanine Supplementation: A Systematic Review With Bayesian Individual and Aggregate Data E-Max Model and Meta-Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, M.P. β-Alanine supplementation for athletic performance: An update. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 1751–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Luchuanyang, S.; Yasunosuke, K.; Murayama, F.; Maegawa, T.; Nikawa, T.; Hirasaka, K. Balenine, Imidazole Dipeptide Promotes Skeletal Muscle Regeneration by Regulating Phagocytosis Properties of Immune Cells. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S.; Pires, V. Rapid photoelectrochemical method for in situ determination of effective diffusion coefficient of organic compounds. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 3875–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, T.; Kankanamge, J.C.; Koller, M.T.; Rausch, M.H.; Fröba, A.P.; Assael, M.J.; Wakeham, W.A.; Guevara-Carrion, G.; Vrabec, J. Definitions and preferred symbols for mass diffusion coefficients in multicomponent fluid mixtures including electrolytes (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2025, 97, 689–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chen, X.; Wu, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, W. Analysis of the Distribution and Influencing Factors of Diffusion Coefficient Model Parameters Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 22536–22544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Vanderheyden, Y.; Adams, E.; Desmet, G.; Cabooter, D. Extensive database of liquid phase diffusion coefficients of some frequently used test molecules in reversed-phase liquid chromatography and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1455, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusler, J.P.M. Measurement of Difision, Coeficients im, Bimary vixtures and Solutions by the Taylor Dispersion Method. Int. J. Thermophys. 2024, 45, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, G.P. Diffusion coefficient for diffusion of time-varying surface concentration by the film-roll method. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 1891–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breer, J.; de Groot, K.; Schönert, H. Diffusion in the Diaphragm Cell: Continuous Monitoring of the Concentrations and Determination of the Differential Diffusion Coefficient. J. Solut. Chem. 2014, 43, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.F.; Komiya, A.; Shoji, E.; Okajima, J.; Maruyama, S. Development of phase-shifting interferometry for measurement of isothermal diffusion coefficients in binary solutions. Opt. Laser Eng. 2012, 50, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, S.G. Development of measuring diffusion coefficients by digital holographic interferometry in transparent liquid mixtures. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 10884–10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, R.; Jan, V.; Agnes, L.; Werquin, S.; Bienstman, P.; Baets, R. Measurement of small molecule diffusion with an optofluidic silicon chip. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 4392–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Meng, W.D.; Sun, L.C.; Cao, X.-F.; Pu, X.-Y. Measurement and verification of concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient: Ray tracing imagery of diffusion process. Chin. Phys. B 2020, 29, 084206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, B.; Oliver, G.; Kerstin, M.; Hasse, H. Diffusion coefficients at infinite dilution of carbon dioxide and methane in water, ethanol, cyclohexane, toluene, methanol, and acetone: A PFG-NMR and MD simulation study. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2022, 166, 106691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Pu, X.; Cheng, D. Optical measurement of concentration-dependent diffusion coefficient by tracing diffusion image width. Optik 2022, 270, 169918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.T.; Long, L.; Yang, H.Y.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Q.; Ju, W.; Li, Z. In situ monitoring of non-Fickian liquid-liquid diffusion with a high space-time resolution fiber-integrated plasmonic sensor. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girault, P.; Lemaitre, J.; Guendouz, M.; Lorrain, N.; Poffo, L.; Gadonna, M.; Bosc, D. Micro-resonators based on integrated polymer technology for optical sensing. In SPIE: Optical Sensing and Detection III; Berghmans, F., Mignani, A.G., DeMoor, P., Eds.; SPIE: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Volume 9141, p. 914121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Meng, W.; Chen, Y.; He, B.; Zhou, Q.; Pu, X. Optical measurement of concentration-dependent diffusion coefficients of binary solution using an asymmetric liquid-core cylindrical lens. Opt. Laser Eng. 2020, 126, 105867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Xia, Y.; Song, F.; Pu, X. Double liquid-core cylindrical lens utilized to measure liquid diffusion coefficient. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 5626–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.; Pu, X. Measuring the mutual diffusion coefficient of heavy water in normal water using a double liquid-core cylindrical lens. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.C.; Wang, D.Y.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, D.; Sheng, S. Design and application of a spherical aberration free continuous zoom liquid-filled micro-cylindrical lenses system. Opt. Eng. 2022, 61, 085102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, L. Design and fabrication of a focus-tunable liquid cylindrical lens based on electrowetting. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 47430–47439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yui, K.; Noda, Y.; Koido, M. Binary Diffusion Coefficients of Aqueous Straight-Chain Amino Acids at Infinitesimal Concentration and Temperatures from (298.2 to 333.2) K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2013, 58, 2848–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoian, H.C.; Kegeles, G. The diffusion of beta-alanine in water at 25°. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, J.G. Measurements of the intradiffusion coefficients at 25° of the ternary systems (labeled L-α-alanine)-(DL-α-alanine)-water and (labeled β-alanine)-(β-alanine)-water. J. Phys. Chem. 1966, 70, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.L.; Zhang, Z. The diffusion behaviors in Mg/Al interface under variated temperatures and surface roughness. Phase Transit. 2025, 98, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiyabu, T.; Sakai, T.; Kudo, R.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Katashima, T.; Chung, U.-I.; Sakumichi, N. Temperature dependence of polymer network diffusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 237801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahavandian, M.; Sarkar, S.; Bagchi, S.; Perez, D.; Martinez, E. From anti-Arrhenius to Arrhenius behavior in a dislocation-obstacle bypass: Atomistic simulations and theoretical investigation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 239, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora, T.L.; Singh, S.K.; Kriti; Mishra, R.R.; Verma, A. Synergistic effects of temperature and strain rate on tensile properties of simulated Ni-6Cu alloy with Σ3 non-Arrhenius grain boundary. Mol. Simul. 2024, 50, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.-D.; Sun, L.-C.; Zhai, Y.; Yang, R.-F.; Pu, X.-Y. Rapid measurement of the diffusion coefficient of liquidsusing a liquid-core cylindrical lens: A method foranalysing an instantaneous diffusive picture. Acta Phys. Sin. 2015, 64, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Meng, W.; Chen, Y.; Song, F.; Pu, X. Measurement of Liquid Diffusion Coefficient Based on Double Liquid-Core Cylindrical Lens: Equivalent Observation Altitude Measurement Method. Acta Opt. Sin. 2018, 38, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Q.; Mneg, W.; Pu, X. A new method for measuring liquid refractive index byanalyzing a defocused image of liquid-core cylindrical lens. Coll. Phys. 2022, 41, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahpour, S.; Kadkhodaei, S. Improving ab initio diffusion calculations in materials through Gaussian process regression. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 013804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Renault, C.; Dick, J.E. Measuring Liquid-into-Liquid Diffusion Coefficients by Dissolving Microdroplet Electroanalysis. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 18748–18753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.