Abstract

Underwater localization using airborne visible light beams offers a promising alternative to acoustic and radio-frequency methods, yet accurate modeling of light propagation through a dynamic air–water interface remains a major challenge. This paper introduces a physics-informed machine learning framework that combines geometric optics with neural network inference to localize submerged optical nodes under both flat and wavy surface conditions. The approach integrates ray-based light transmission modeling with a third-order Stokes wave formulation, enabling a realistic representation of nonlinear surface slopes and their effect on refraction. A multilayer perceptron (MLP) is trained on synthetic intensity–position datasets generated from this model, learning the complex mapping between received optical power (light intensity) and coordinates of the submerged receiver. The proposed method demonstrates high precision, stability, and adaptability across varying geometries and surface dynamics, offering a computationally efficient solution for optical localization in dynamic underwater environments.

1. Introduction

The growing demand for high-speed, low-latency, and interference-free communication in marine environments has accelerated research into optical methods for underwater data exchange and positioning [1]. Traditional acoustic and radio-frequency (RF) techniques, while well established, face inherent limitations in bandwidth, propagation delay, and signal distortion, particularly in shallow or turbulent waters. Although acoustic systems are capable of long-range communication, they suffer from strong multipath effects, low data rates, and environmental dependency on temperature and salinity [2]. RF signals, on the other hand, attenuate rapidly in conductive seawater, restricting their range to only a few centimeters [3]. In contrast, visible light communication (VLC) has emerged as a promising alternative, leveraging high-frequency optical carriers to achieve data rates several orders of magnitude higher than those possible with acoustic or RF systems [4]. Moreover, VLC enables energy-efficient, low-interference links that can be harnessed not only for communication but also for localization, imaging, and sensing in aquatic environments [5].

However, the practical realization of optical communication and localization underwater remains challenging. The propagation of light through the air–water interface and within the water column is governed by a combination of geometric and physical optics, including reflection, refraction, absorption, and scattering phenomena [6]. These effects are highly dependent on wavelength, water composition, turbidity, and most critically, the shape and dynamics of the water surface [7]. Even small perturbations at the interface can significantly alter the path and intensity distribution of transmitted rays, affecting both the received signal strength and the inferred spatial geometry. In particular, localization using airborne light beams is of interest since it can be encoded to include Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates and enable submerged nodes to be globally localized without the need for surface (floating) nodes. Consequently, developing models that accurately describe how light behaves when transitioning between two refractive media with a dynamic boundary is essential for designing reliable underwater VLC and localization systems.

Existing optical models commonly assume a flat and static air–water interface, which simplifies the geometry of refraction and allows analytical expressions for transmitted irradiance [8,9,10,11,12]. In these models, the beam is typically approximated as a cone of light refracted uniformly according to Snell’s law, and the intensity attenuation is modeled exponentially using the Beer–Lambert law. While these assumptions facilitate simulation and are useful for system prototyping, they do not reflect real-world conditions. In practice, the ocean surface is constantly modulated by gravity waves, surface tension effects, and environmental disturbances, producing continuously changing slopes and curvatures [13]. These variations result in nonuniform focusing and defocusing of optical energy [14], localized caustics, and intensity fluctuations that directly influence the reliability of underwater positioning.

To overcome these limitations, this paper introduces a practical framework that models light propagation from an airborne transmitter into an underwater medium through a nonplanar, dynamically evolving surface. The model integrates geometric ray tracing with third-order Stokes wave theory, which provides an analytical yet accurate representation of nonlinear periodic waves in deep water [15]. Unlike sinusoidal or first-order approximations, the Stokes expansion incorporates higher harmonics of the wave phase, capturing the asymmetry between crests and troughs and thus yielding a more realistic depiction of real sea surface profiles. By combining this wave representation with Snell’s law and Fresnel transmission coefficients, each individual light ray experiences a locally defined surface slope and normal, resulting in the precise computation of incidence, refraction, and transmission angles. The model thereby accounts for spatial variations in surface curvature and their corresponding influence on light distribution below the surface.

This framework is then used to generate synthetic datasets that couple physical simulation outputs with machine-learning-based localization. Specifically, the multilayer perceptron (MLP) network is employed to learn the nonlinear mapping between measured light intensity and the three-dimensional position of an underwater node (UN). The MLP network takes as input the received optical power and the transmitter’s spatial coordinates, and outputs an estimate of the UN’s true position. Training is conducted using physically consistent data generated by the simulation under two scenarios: (1) a flat-surface case serving as an idealized reference, and (2) a wavy-surface case incorporating dynamic Stokes surface motion and multiple phase realizations. Such a dual configuration enables a quantitative evaluation of how interface dynamics influence the optical field and the neural network’s learning behavior.

The proposed Learning-based Airborne-enabled Underwater Localization (LAUL) framework differs from existing localization methods in several keyways. First, LAUL is hybrid in nature, combining a physics-based forward model with a data-driven inverse model. The forward component simulates the actual propagation environment, producing ground-truth intensity and positional data, while the neural network learns to invert this process by estimating the UN’s location directly from measurable quantities. This separation allows the machine learning (ML) model to leverage the realism of the physical simulator while remaining lightweight and generalizable. Second, LAUL captures wave-induced refractive variability, a factor typically omitted in prior optical localization studies. By simulating multiple transmitter positions and surface phases, the constructed dataset encapsulates the spatial–temporal diversity inherent in real marine conditions, providing the neural network with richer information for robust learning. Third, despite this physical and computational complexity, the overall system remains efficient, achieving full data generation and training within seconds, as indicated by the validation results. In summary, this work makes the following contributions:

- A comprehensive physical–optical model of underwater light propagation that integrates third-order Stokes wave surface modeling, Snell’s law refraction, and exponential attenuation, providing an accurate representation of underwater irradiance.

- A hybrid physics-informed learning pipeline, where a multilayer perceptron is trained on synthetic data derived from physical ray tracing to perform accurate 3D localization from limited optical information.

- Extensive simulation-based validation under both flat and wavy-surface conditions, demonstrating high localization accuracy and efficient convergence.

By integrating physically grounded optical modeling with data-driven estimation, this study bridges the gap between theoretical optics and practical underwater localization. The combination of physical realism, computational efficiency, and learning flexibility positions this framework as a foundational tool for next-generation underwater communication and positioning technologies.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 sets LAUL apart from published studies. The detailed design of LAUL is provided in Section 3 and Section 4. Section 3 presents the cross-medium light propagation model. The machine learning model is discussed in Section 4. Section 5 focuses on the dataset construction while the performance results are presented in Section 6. Finally, the paper is concluded in Section 7.

2. Related Work on Underwater Localization

Ranging Techniques: Underwater localization has traditionally employed acoustic, radio, and magnetic induction (MI) techniques, each of which presents inherent trade-offs in range, bandwidth, and deployment complexity [16,17,18,19,20]. Acoustic-based systems offer long-range capability but suffer from limited bandwidth, strong multipath interference, and high latency, particularly in shallow or turbulent environments. RF techniques experience severe attenuation in seawater, while MI-based localization remains restricted to short ranges and requires bulky hardware. These limitations have motivated increasing interest in VLC for underwater applications, particularly in scenarios requiring high data rates, low latency, and high spatial resolution [21].

Most existing VLC-based underwater localization models assume a planar air–water interface and employ Snell’s law in conjunction with Beer–Lambert attenuation to derive closed-form expressions for received irradiance [9]. While this flat-surface assumption enables analytical tractability and has been widely adopted in geometry-based localization frameworks, it neglects the spatially varying refraction introduced by realistic ocean surface waves. In practice, the air–water interface is continuously modulated by wind-driven waves, resulting in time-varying surface slopes and curvature that distort optical propagation paths. Recent studies have examined optical signal propagation through nonplanar or wavy air–water interfaces and have demonstrated significant surface-induced distortion of the underwater optical field [22]. However, these efforts have largely focused on communication-oriented performance metrics—such as received signal strength (RSS), signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and bit-error rate (BER)—rather than on localization. As a result, relatively few localization frameworks explicitly couple dynamic surface-induced refraction with geometric beam propagation, and even fewer investigate learning-based inversion methods built upon physically grounded wavy-surface optical models.

Data-Driven Positioning Methodologies: Machine-learning-based localization has been increasingly explored in underwater systems to overcome the limitations of geometry-based inversion (multilateration) under nonlinear propagation, multipath interference, and environmental uncertainty. Several studies have formulated localization as a supervised regression problem, where node coordinates are inferred directly from measured signal features. For example, Yuan et al. employed classical learning algorithms to estimate underwater acoustic source locations from received signal features, demonstrating improved robustness compared to conventional analytical localization methods under noisy conditions [23]. Similar learning-based formulations have shown that data-driven models can reduce sensitivity to measurement noise and model mismatch relative to multilateration-based approaches.

Deep learning architectures have further extended these ideas by exploiting spatial, spectral, and temporal structure in underwater measurements. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been applied to time–frequency representations and array observations for underwater source localization and direction-of-arrival estimation, achieving superior performance in reverberant and low-SNR environments compared to classical beamforming and model-based techniques [24,25]. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and hybrid CNN–RNN models have also been investigated to capture temporal correlations in underwater acoustic signals, enabling improved localization and tracking of mobile sources in dynamic environments [26,27]. Hybrid localization frameworks that combine learning-based inference with classical estimation techniques have likewise been reported, where neural networks provide coarse position estimates or likelihood mappings that are subsequently refined using Kalman filters or particle filters to improve convergence and robustness in sparse sensing scenarios [28].

Despite these advances, the majority of learning-based underwater localization methods have focused on acoustic sensing modalities, where multipath propagation and medium inhomogeneity dominate system performance. Learning-based localization in the optical domain remains comparatively limited, and existing optical studies typically rely on simplified flat-surface propagation assumptions. Even when machine learning is employed, complex surface-induced effects—such as wave-driven refraction, spatially correlated intensity fluctuations, and time-varying focusing and defocusing—are rarely incorporated explicitly into the learning process and are instead treated as unstructured noise [29]. This model–data mismatch can significantly degrade performance when learning-based models trained under idealized assumptions are applied to realistic ocean environments.

Handling Wavy Surface: Although several recent studies have rigorously investigated optical signal propagation through a wavy water surface, their primary focus has remained on communication-oriented metrics such as RSS, SNR, and BER. To date, these physically grounded wavy-surface channel models have not been explicitly incorporated into a localization framework. A notable example is the work by Fang et al. [30], in which the wavy air–water interface is modeled using the Pierson–Moskowitz (PM) wave spectrum. The PM model characterizes the sea surface as a stochastic process governed by wind speed, where higher wind conditions correspond to increased wave amplitudes, steeper surface slopes, and enhanced spatiotemporal variability. That study provides a comprehensive forward model for underwater optical signal propagation through a dynamically evolving air–water interface, mapping transmitter–receiver geometry and surface realizations to observable quantities such as RSS and SNR. However, it does not address the inverse problem of estimating receiver position from these measurements.

To our knowledge, no existing underwater localization framework explicitly incorporates a dynamically evolving wavy air–water interface into the end-to-end localization process, nor do current methods jointly model wave-induced refraction, geometric beam propagation, and position estimation. This limitation is especially pronounced in cross-medium optical localization scenarios, where refraction at the air–water boundary introduces strong coupling between transmitter geometry, surface state, and underwater irradiance patterns. As a result, existing localization techniques—whether acoustic, electromagnetic, or optical—remain fundamentally constrained by simplified surface assumptions that do not reflect realistic ocean conditions.

3. Light Propagation Model

The proposed framework models the propagation of light from an airborne optical transmitter into the underwater medium through a wavy air–water interface. The model combines geometric optics and physical attenuation to describe how optical energy evolves as it passes through two refractive media with a nonplanar boundary. It accounts for variations in surface slope due to wave motion, changes in local incidence and refraction angles for each ray, attenuation of light intensity through absorption and scattering in water, and beam divergence dictated by the transmitter’s emission cone. Together, these components form a physically realistic system that enables the computation of underwater irradiance for different wave geometries, transmitter configurations, and receiver depths. The detailed model is described in this section.

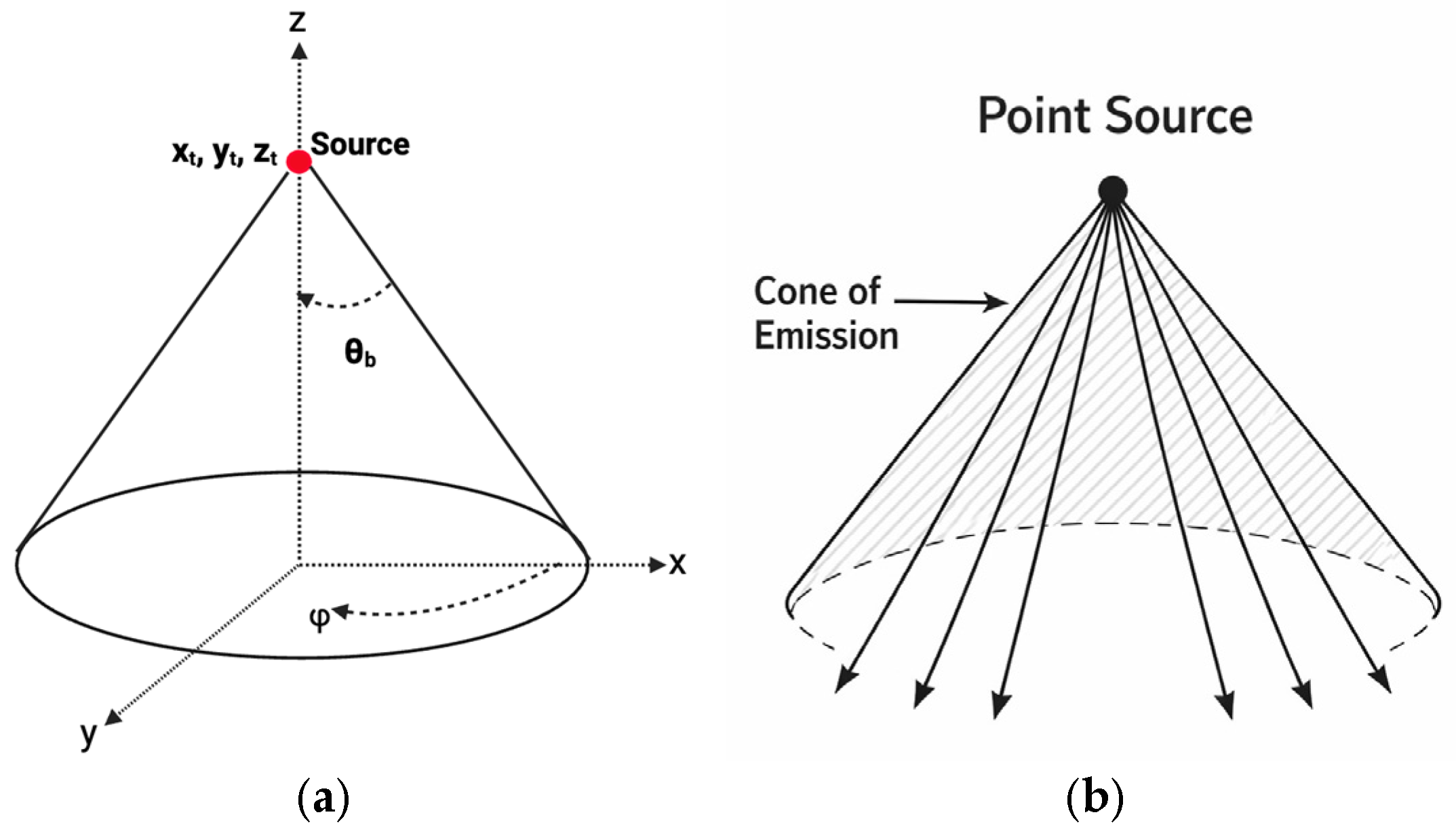

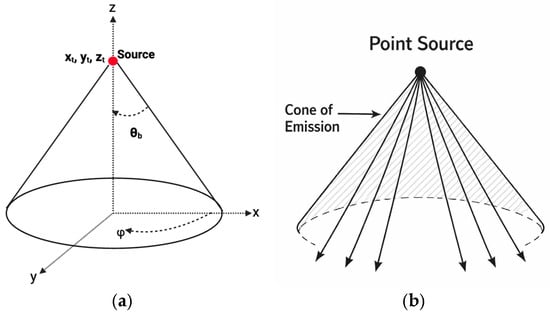

Ray Emission and Propagation in Air: The optical transmitter is positioned above the surface at coordinates and emits a conical beam of light characterized by a half-angle as shown in Figure 1. This parameter defines the beam’s angular spread—smaller values of produce a narrow, high-intensity beam capable of deeper penetration, while larger values generate a wider beam that illuminates a broader region at the expense of lower energy density per unit area.

Figure 1.

(a) Ray emission visualization (b) Point source transmitter at cone apex. Arrows signify individual light rays.

Each emitted ray is parameterized by its emission angles , where is the polar deviation from the optical axis and is the azimuthal direction. The emission direction in Cartesian coordinates is:

Uniform sampling of and ensures even coverage across the beam cone. The position of each ray in space is given by

where denotes the propagation distance along the ray’s direction. The components of this ray are

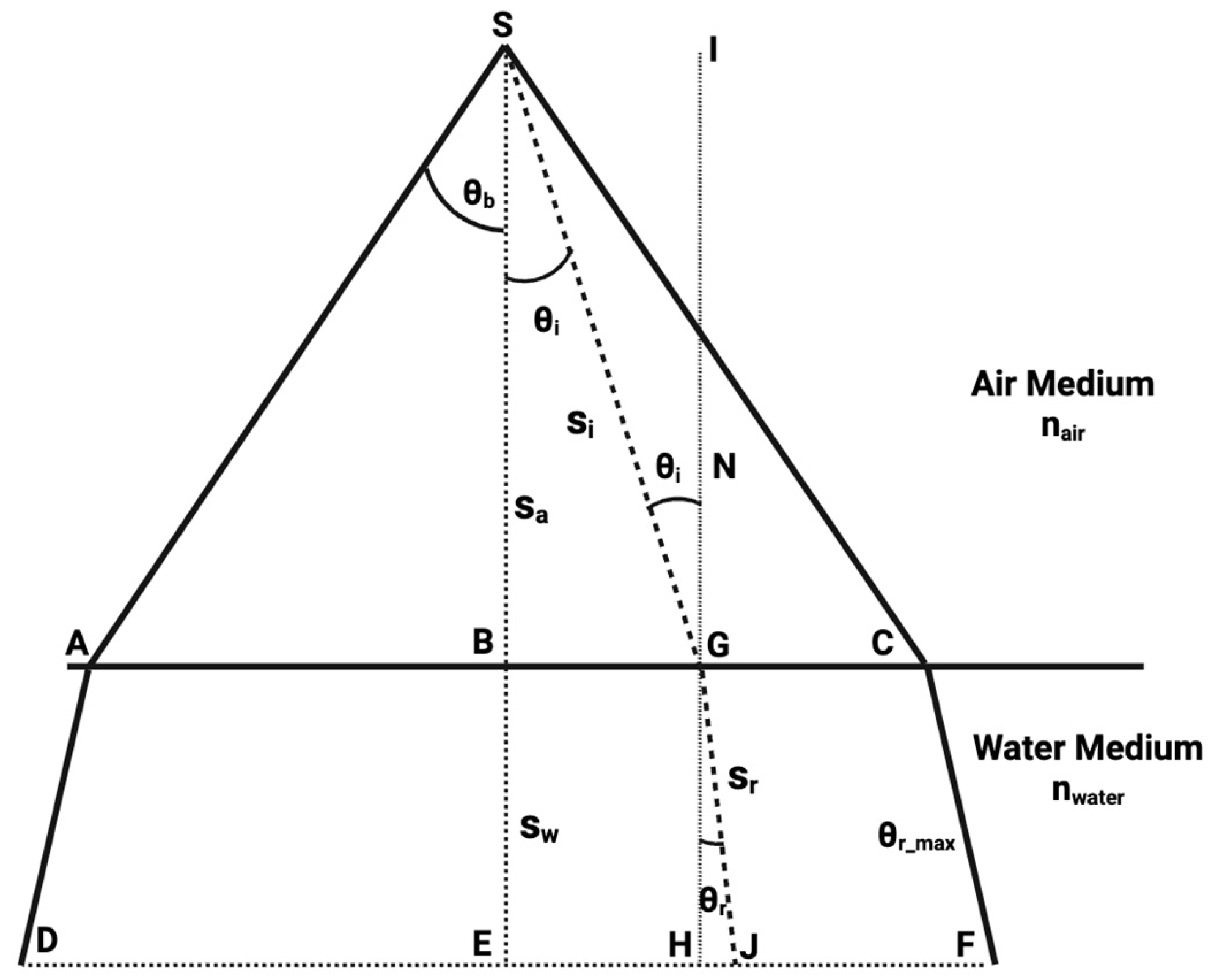

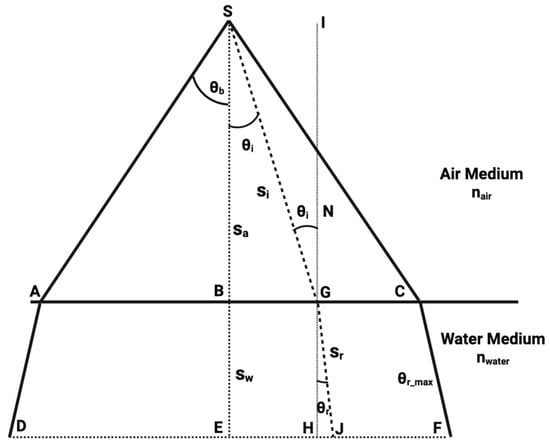

Wavy Water Surface Challenge: Assuming a stationary, horizontally planar interface, uniform refractive behavior is experienced across all rays [9]. As illustrated in Figure 2, we can consider a calm and flat water surface with a uniform light source located at point , emitting a conical beam characterized by a half-beam angle . The source is positioned meters above the water surface, while an underwater sensor is placed at a depth of meters. Because the water surface is assumed to be perfectly flat, the surface normal remains constant across all points of incidence. Consequently, the computation of the incidence angle for each light ray—and the corresponding refraction angle upon entering the water—follows directly from Snell’s law and remains straightforward. denotes the unit normal vector at the surface intersection point, and denote propagation distances (path lengths) in air and water, respectively.

Figure 2.

A 2D illustration of the coverage of light transmission from a source at S above the water surface.

Unlike the flat-surface, the wavy-surface model introduces a spatially varying normal vector at every point on the surface. This means that each emitted ray encounters a distinct local incidence angle depending on where it strikes the undulating interface. As a result, refraction follows Snell’s law individually for every ray, creating nonuniform angular bending and intensity redistribution beneath the surface. Furthermore, the wave-dependent geometry leads to focusing and defocusing patterns—regions where light converges or diverges due to local curvature—which cannot be captured by a flat interface. The wavy model, therefore, provides a more faithful approximation of realistic oceanic and laboratory water surfaces, where dynamic roughness causes stochastic variations in irradiance, energy loss, and beam spread that significantly influence underwater visibility and localization accuracy.

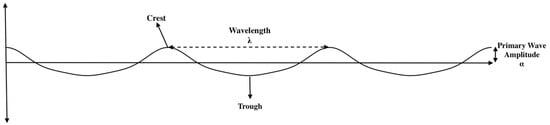

Wavy Surface Representation: The dynamic air–water interface is modeled using a third-order Stokes wave formulation [15,31], which captures the nonlinear crest–trough asymmetry of realistic ocean surfaces. This approach improves upon the simple sinusoidal representation by accounting for higher harmonic contributions that shape sharper crests and broader troughs—characteristics commonly observed in real wave profiles. The instantaneous surface elevation is defined as

where

Here, is the primary wave amplitude, , is the wavenumber corresponding to wavelength , and represents the direction of wave propagation. The coefficients , , and are derived from the Stokes perturbation series and incorporate higher-order nonlinear effects, given by [32]

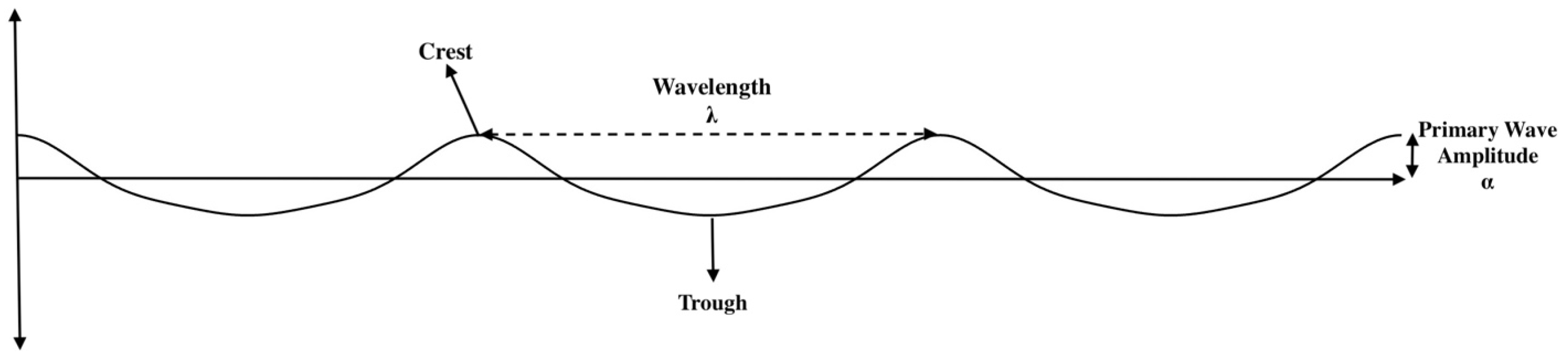

The phase term governs the instantaneous surface state, effectively representing temporal evolution. By varying across multiple simulations, distinct surface realizations are generated, emulating dynamic wave motion over time. Figure 3 illustrates the wave.

Figure 3.

Surface wave visualization according to Stokes’ third-order theory.

The wavy air–water interface is modeled as a height field defined by

where denotes the instantaneous surface elevation and represents the wave phase.

To obtain the local surface normal required for refraction modeling, the height field is converted into an equivalent implicit surface representation. Define the scalar field

The interface corresponds to the zero level set of this function,

For any implicit surface , a normal vector is given by the gradient of :

Using , the partial derivatives become

Therefore, the (unnormalized) normal vector can be expressed as

Finally, the corresponding unit normal vector is obtained via normalization:

where

Substituting the above expressions yields

At each point on the surface, this local slope determines the orientation of the surface normal.

Here,

These spatial gradients are directly derived from the Stokes surface equation and vary with both and , creating locally tilted interfaces that influence the incidence and refraction angles of each incoming ray. Our Stokes-based formulation provides a physically meaningful representation of wave geometry while remaining analytically manageable for simulation. It captures essential nonlinear behaviors of surface undulations without resorting to fully numerical fluid simulations, making it ideal for optical ray-tracing studies that require realistic but computationally efficient wave profiles.

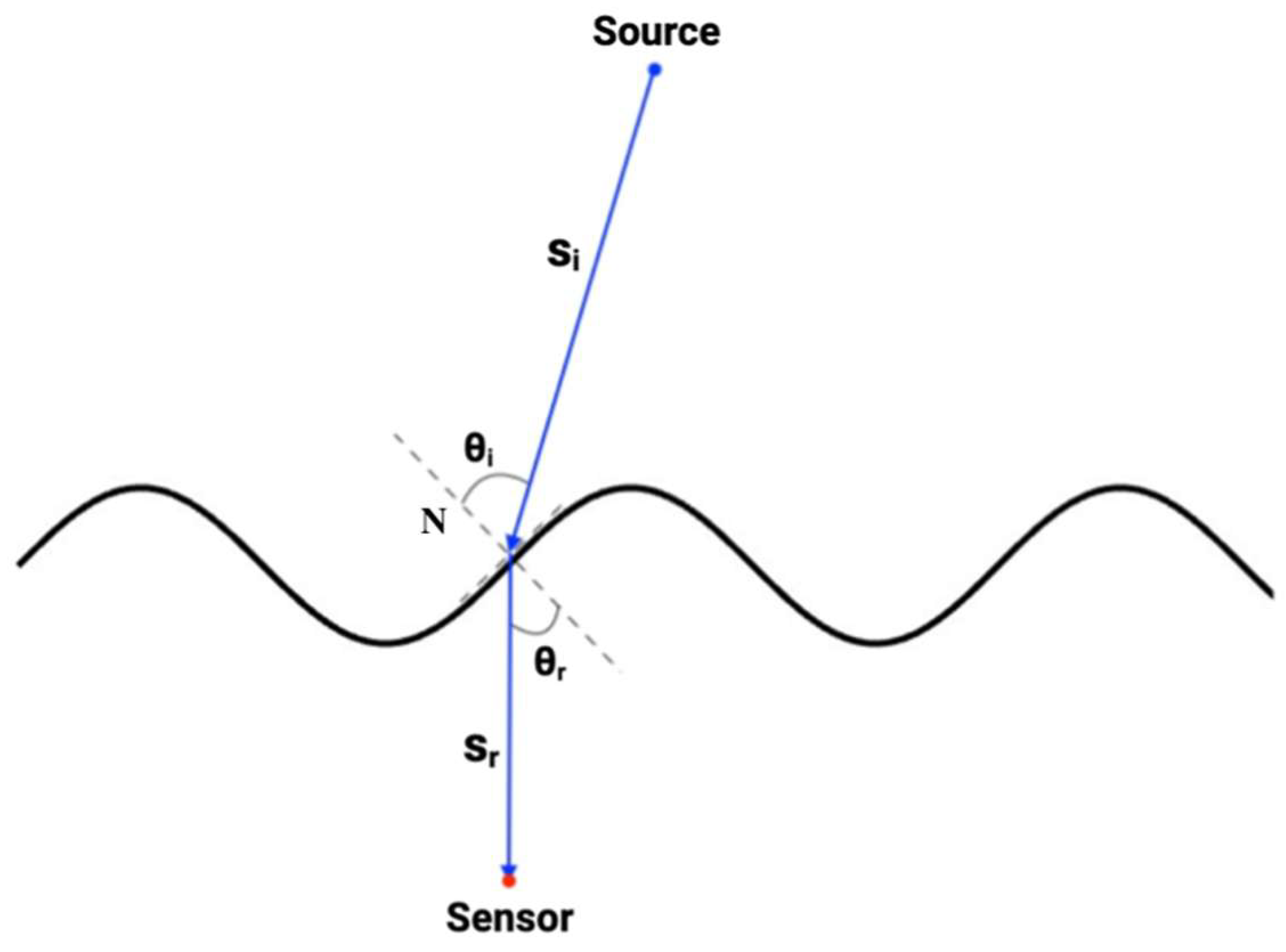

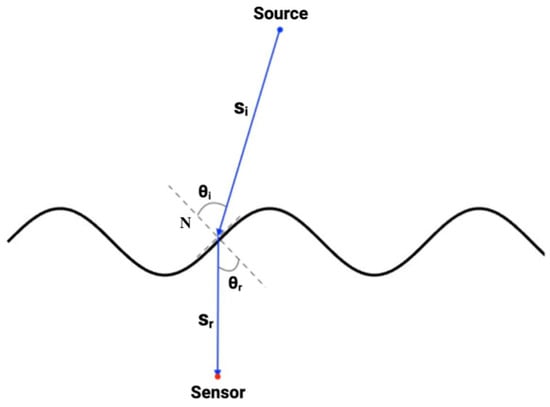

Ray–Surface Intersection: As illustrated in Figure 4, the intersection point occurs when the ray height equals the surface height. Thus, the intersection of each ray with the moving water surface is determined by solving

where

Figure 4.

Light ray direction illustration for wavy surface.

This nonlinear equation is solved numerically to obtain the distance to the intersection point. The corresponding coordinates of the intersection are

Because the surface is spatially varying, every ray strikes a slightly different location and encounters a unique local normal, resulting in individual refraction behaviors that collectively determine the light distribution below the surface.

Refraction at the Air–Water Interface: At the intersection point, each incident ray undergoes refraction according to Snell’s law:

where ). Here, denotes the unit incident direction in air and denotes the unit surface normal at the intersection point. The refracted ray direction is computed using the vector form of Snell’s law:

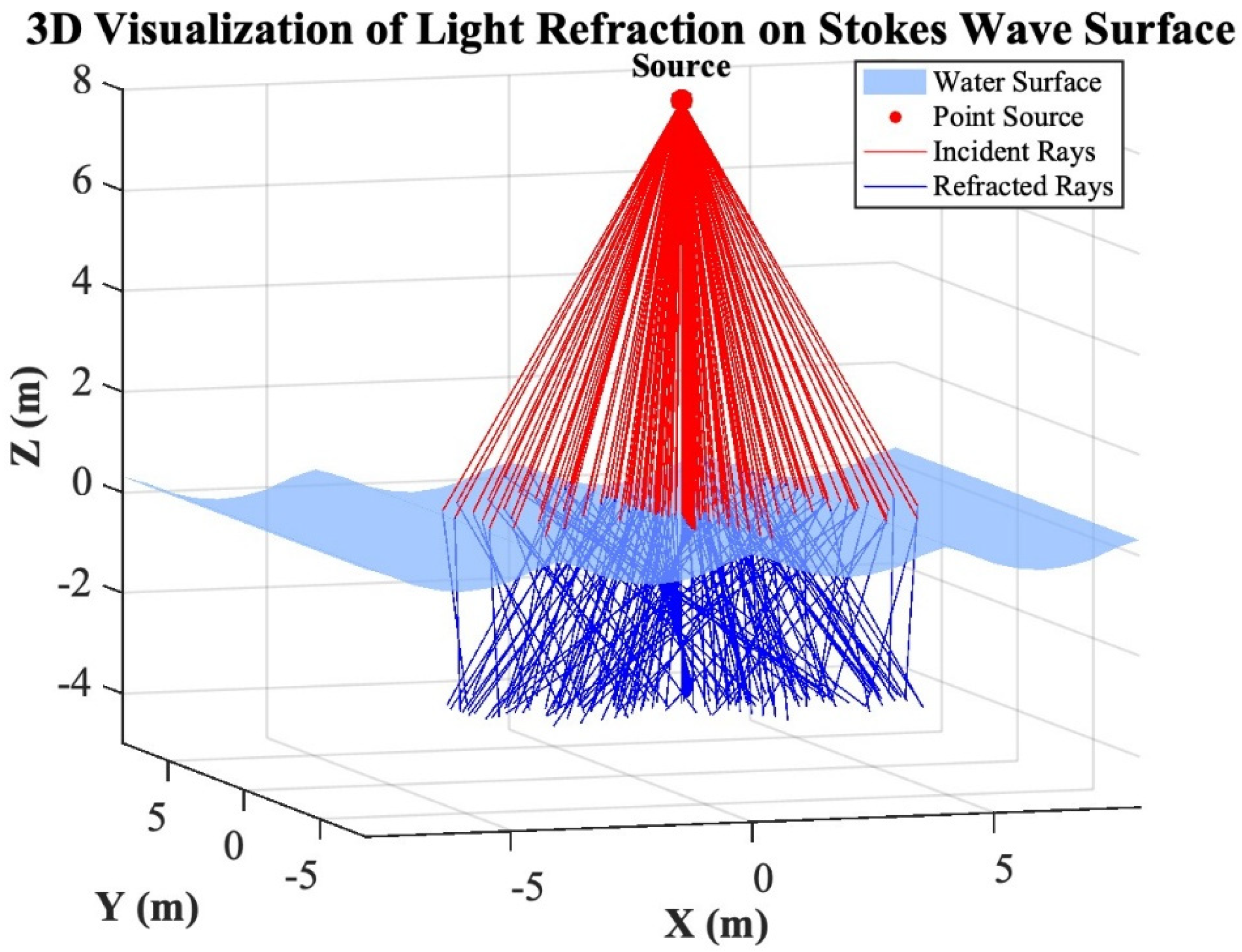

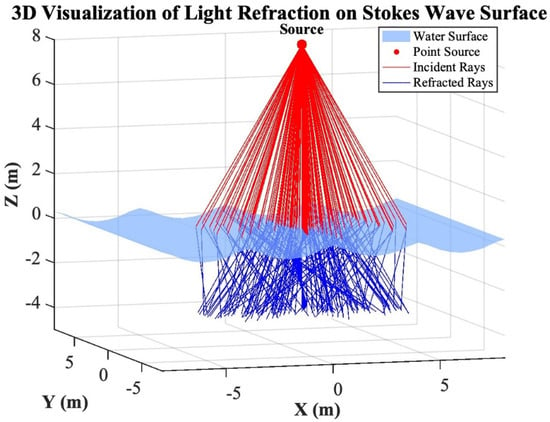

The refractive indices and play a central role in defining how sharply the rays bend. Because >, the refracted rays bend toward the normal, compressing the cone of light and increasing the density of rays beneath the interface. Variations in surface curvature, combined with this refractive bending, produce complex patterns of convergence and divergence in the underwater illumination as illustrated in Figure 5. Algorithm 1 summarizes the ray-tracing process.

| Algorithm 1 Ray–Tracing through a Wavy Air–Water Interface |

| Input: transmitter position , beam half-angle , number of rays , refractive indices , surface , target depth , wave phase Output: refracted ray endpoints at depth Freeze wave snapshot: Fix a single wave phase and treat the interface as stationary during one transmission. For each ray : (a) Sample emission angles uniformly within the transmitter cone and compute the incident direction in air . (b) Propagate the ray in air from the transmitter until it intersects the instantaneous wavy surface, and compute the intersection point . (c) Evaluate the local unit normal vector at the intersection point using the surface gradients. (d) Apply Snell’s law at to compute the refracted direction in water . (e) Propagate the refracted ray in water until it reaches the target depth plane , producing the endpoint . Return the set of underwater ray endpoints . |

Figure 5.

3D visualization of light refraction on a wavy surface.

Underwater Propagation and Attenuation: Once refracted, each ray continues through the water along the direction . For a desired observation depth , the distance a ray travel underwater is

where is the vertical component of the refracted direction.

The ray’s intensity decreases along this path due to absorption and scattering, described by the exponential attenuation law [9]:

Here, is the transmitted optical power, represents the transmittance at the interface, and is the attenuation coefficient of water. A larger value indicates stronger absorption and scattering, leading to rapid intensity decay with depth. Clear water with a small maintains energy over longer distances, while turbid water severely restricts light penetration. The exponential term, therefore, captures the combined effects of water clarity and propagation distance on the observed irradiance.

Spatial Intensity Distribution and Energy Accumulation: To simulate the complete underwater light field, a large ensemble of rays is emitted and traced independently through the wavy interface. Each refracted ray travels until it reaches a target depth, at which its intersection coordinates and corresponding intensity are recorded. Because multiple rays may refract through different surface points yet converge at similar underwater positions, their contributions must be accumulated. The total irradiance at a given point is obtained by summing all contributing rays:

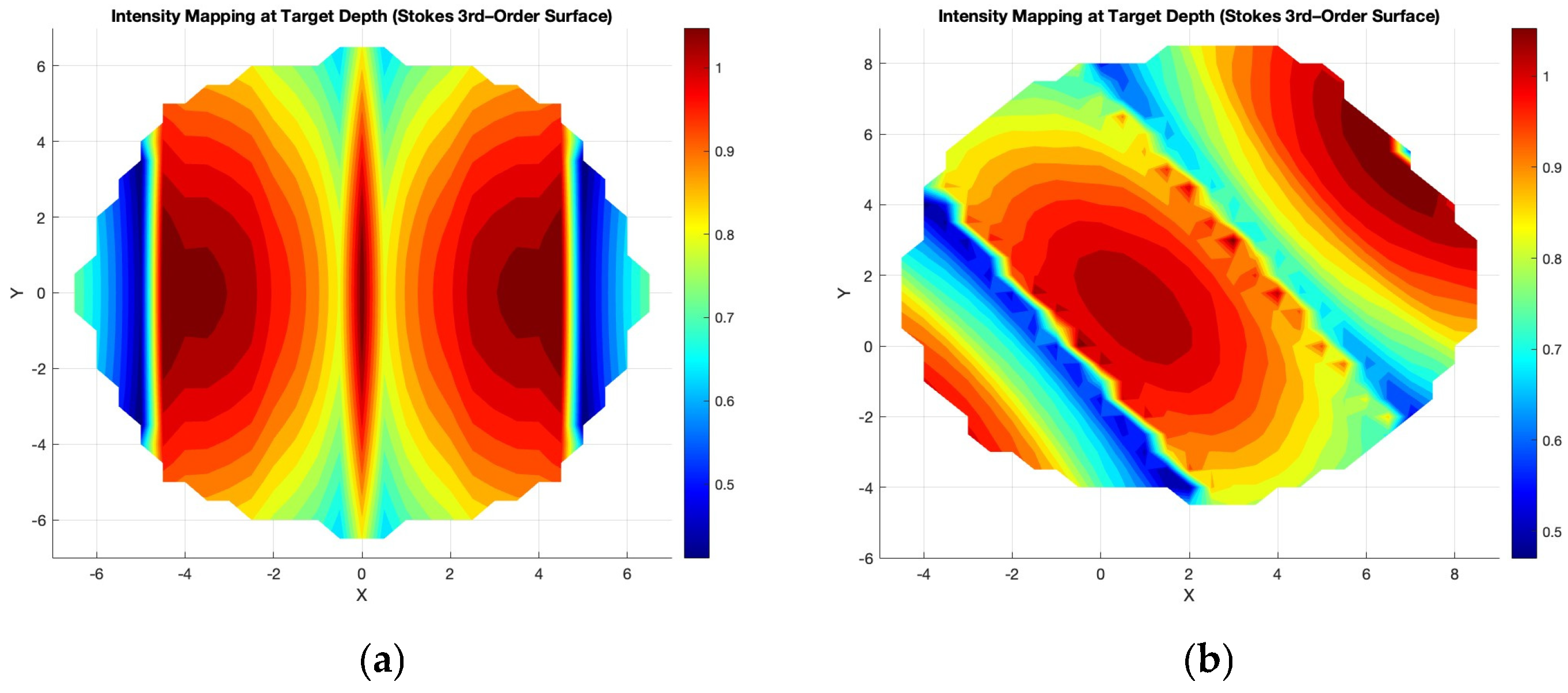

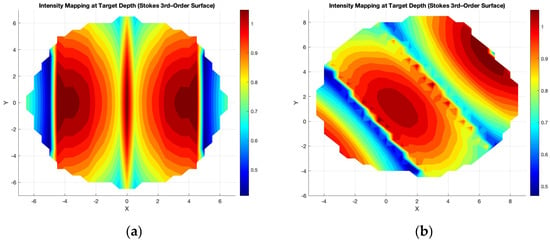

where is the attenuated intensity of the ray, and is the number of rays intersecting the observation plane at that point. As shown in Figure 6, the result is a continuous two-dimensional intensity field or irradiance heatmap, generated via spatial interpolation across a regular grid.

Figure 6.

Intensity heatmap for a wavy surface for (a) and sensor position of (0,0,10) (b) and sensor position of (2,2,10). Color bar denotes received optical irradiance (W/).

The figure reflects a heatmap of how optical energy is redistributed beneath the surface due to the combined effects of beam divergence, surface curvature, and refraction geometry. Bright regions correspond to zones where refracted rays concentrate, producing optical focusing, while darker areas indicate divergence or shadowing. By adjusting model parameters such as wave amplitude, beam angle, and attenuation coefficient, the simulation can replicate a wide range of realistic illumination conditions—from calm, clear waters with symmetric beam patterns to rough, turbulent surfaces producing fragmented and diffuse light fields.

4. LAUL Design

This section presents the proposed LAUL framework, which estimates the three-dimensional position of an underwater sensor by learning the inverse relationship between optical measurements and spatial geometry. Unlike conventional localization techniques that rely on explicit geometric inversion or multilateration, LAUL adopts a data-driven approach that directly maps measured optical intensities and transmitter configurations to the sensor location. This design choice significantly improves robustness to physical uncertainties, surface irregularities, and nonlinear light–matter interactions.

Consider an underwater sensor located at an unknown position within a bounded underwater region. A set of airborne optical transmitters illuminates the water surface from known positions Each transmitter emits a downward-facing conical optical beam with known power . The transmitted light undergoes refraction at the air–water interface and attenuation within the water column before being measured by the underwater sensor as received intensity .

The localization problem is estimating using the set of intensity measurements together with the known transmitter configurations. Due to the nonlinear nature of refraction, Fresnel transmission, beam divergence, and underwater attenuation, deriving a closed-form inverse solution is highly sensitive to physical uncertainties. LAUL addresses this challenge by learning the inverse mapping directly from data generated using a physics-consistent forward model.

Learning Model Design: LAUL formulates underwater localization problem as a supervised regression task. Given an input feature vector, that encapsulates all optical measurements and transmitter parameters, the objective is to learn a nonlinear function: where is parameterized by a neural network with trainable parameters .

Rather than explicitly estimating intermediate physical quantities such as refraction angles or path lengths, the learning model directly predicts the sensor position. This approach avoids error amplification associated with analytical inversion and allows the network to implicitly compensate for modeling inaccuracies and environmental variability.

For each localization instance, the input feature vector is constructed by concatenating the intensity measurement and geometric parameters associated with each active transmitter. Specifically, for transmitters, the input vector is defined as:

Here, represents the received optical intensity from the -th transmitter, while and denote the corresponding transmitter position and emitted optical power. The localization model is trained to estimate the three-dimensional sensor position directly from these measurements, without requiring any prior knowledge of the sensor depth. As a result, depth-dependent attenuation effects must be inferred implicitly from the variations in received intensity and transmitter geometry, reflecting realistic scenarios in which explicit depth information may not be available. The dimensionality of the input vector grows linearly with the number of transmitters, enabling the framework to flexibly operate with varying transmitter counts.

The inverse mapping is implemented using a multilayer perceptron consisting of three fully connected hidden layers with rectified linear unit (ReLU) activations, followed by a linear output layer that produces the estimated sensor coordinates . While the depth of the MLP network is fixed to ensure training stability, the width of the hidden layers is scaled proportionally with the number of transmitters . This design choice accounts for the increasing input dimensionality and information content as additional transmitters are introduced. Scaling the network capacity prevents underfitting in higher-dimensional configurations while maintaining a consistent architectural structure across experiments. Table 1 represents the learning model structure for different transmission count:

Table 1.

LAUL Learning Model Structure.

Training Methodology: The MLP is trained using supervised learning on datasets generated through physics-based optical propagation simulations. For each training sample, the true sensor position serves as the regression target. The training objective is to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) loss:

where denotes the number of training samples. Optimization is performed using the Adam optimizer [33], which offers fast convergence and robustness to variations in gradient magnitude across different transmitter configurations.

The proposed learning framework is evaluated under both flat and dynamically modulated air–water interface conditions. In the flat-surface scenario, light propagation follows an analytically smooth relationship governed by Snell’s law and exponential attenuation. In the wavy-surface scenario, the interface is modeled using a third-order Stokes wave, introducing spatially varying surface normals, phase-dependent refraction, and localized focusing and defocusing effects. Rather than explicitly compensating for these effects, LAUL incorporates them naturally through training data generated by the corresponding forward model. The MLP learns the complex yet consistent mapping between distorted intensity patterns and sensor position, enabling robust localization even in the presence of surface-induced nonlinearities.

5. Dataset Construction

To train and evaluate the proposed learning-based localization framework, a comprehensive dataset is generated using physics-based optical simulations. The dataset is constructed to capture the relationship between airborne optical transmissions and underwater intensity measurements under both flat and dynamically varying water surface conditions, including time-varying surface wave phase.

Simulation Setting: A three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system is adopted, with the air–water interface located at . Underwater sensors are randomly deployed within a bounded region defined by:

Airborne transmitters are positioned above the water surface at heights ranging from 6 m to 12 m. Their horizontal locations are distributed around the underwater node x and y coordinates within a finite radius to reflect realistic airborne illumination where coverage can be partial and non-uniform. The transmitter power is sampled within watts, with an attenuation coefficient of 0.056 m−1 to model absorption and scattering losses in clear water. The transmission coefficient across the air–water boundary was set to 0.99. The refractive indices were defined as and , consistent with the visible light spectrum in seawater. Table 2 represents a brief summary of all relevant parameters.

Table 2.

Transmitter and Receiver Parameter Settings for Dataset Construction.

Two surface conditions are considered:

- Flat surface: the interface is planar, yielding a smooth and deterministic mapping between geometry and received intensity.

- Wavy surface: the interface is modeled as a third-order Stokes wave. In this case, the local surface elevation and surface normal depend on the wave phase, which represents a time snapshot of the evolving surface. As a result, the effective refraction angles and optical paths vary with phase, producing spatial focusing/defocusing and intensity fluctuations.

Each data sample corresponds to a single underwater sensor illuminated by multiple airborne transmitters. Each simulated transmission is generated using a snapshot (single frozen realization) of the wavy air–water interface. Specifically, the surface is treated as stationary within one transmission by fixing the phase . To emulate time-varying water motion across transmissions, the phase is randomly varied among transmissions producing diverse refractive conditions and corresponding intensity observations. This approach captures the dynamic influence of wave motion while maintaining a physically consistent ray-tracing procedure for each transmission. For the baseline configuration, a master dataset of 5000 independent samples is generated using five transmitters. Each sample is associated with a unique sensor position, transmitter geometry and optical power configuration. Reduced-input configurations with two, three, or four transmitters are derived by selecting subsets of the five-transmitter measurements from the same master dataset. This strategy ensures that comparisons across different transmitter counts are performed on consistent physical scenarios and that performance differences primarily reflect sensing diversity rather than changes in environmental conditions. For each transmitter configuration, the dataset is randomly divided into training and testing subsets, with 80% of the samples used for training and the remaining 20% reserved for evaluation. Input features are normalized using statistics computed from the training set only, and the same normalization parameters are applied to the test set.

6. Validation Results

The experiments were conducted under two complementary operating regimes. The first considered a flat air–water interface, where the received optical intensity was computed using a closed-form physical model with injected parameter uncertainties to reflect measurement errors and noise. The second employed a dynamically modulated wavy surface modeled using a third-order Stokes wave, where light propagation was simulated via physics-based ray tracing through a time-varying interface. In both regimes, the input to the learning model consists of the received optical intensity measurements together with the known positions and optical power of multiple airborne transmitters. The network was trained to estimate the full three-dimensional position of the underwater sensor. No prior depth information was provided during inference; instead, the depth coordinate was inferred implicitly from the joint spatial and radiometric variations in the received signals. Localization performance has been evaluated using the Euclidean distance between the predicted and true sensor positions.

Flat surface scenario: First, we compare the localization performance of the LAUL framework with a conventional multilateration-based localization method under flat-surface conditions [9]. To ensure a fair comparison, both methods were evaluated using the same noisy measurements. Specifically, the transmitted optical power was perturbed by up to ±10% to reflect source instability and calibration errors, and small angular deviations on the order of ±1–2° were introduced to model beam misalignment and airborne platform motion. These uncertainties propagate nonlinearly through refraction, geometric spreading, and underwater attenuation, directly affecting the received intensity used for localization. To enhance practical relevance, the simulations explicitly incorporate several non-idealities encountered in real deployments, including wave-induced refraction with spatially varying surface normals, non-uniform and partial illumination due to randomized transmitter placement, transmitter power variability, and discretized intensity sampling, which collectively introduce realistic distortions and measurement uncertainty into the localization process.

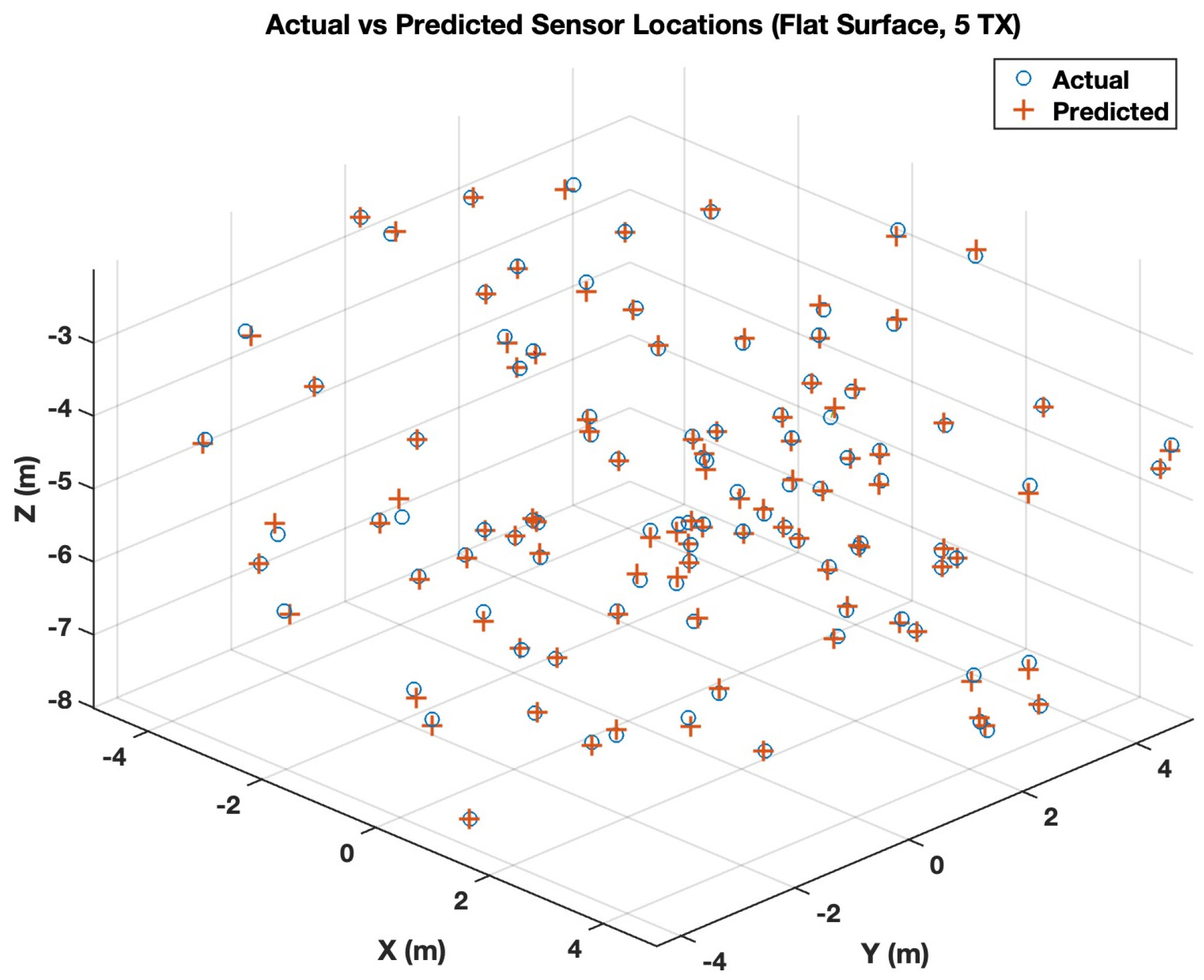

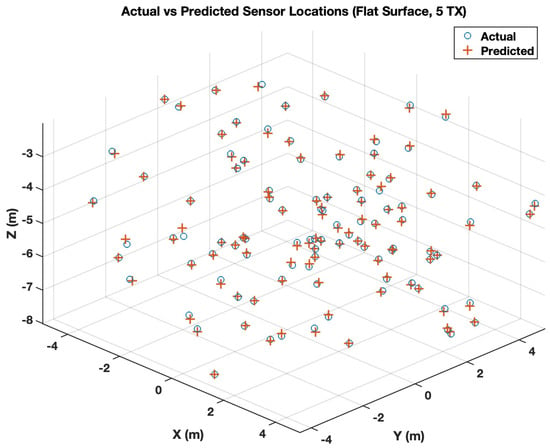

The LAUL’s results in Table 3 show a strong dependence on the number of transmitters. With two transmitters, the localization accuracy is limited by weak geometric constraints, resulting in a mean error of approximately 0.69 m. However, the median error remains below 0.6 m, indicating that most estimates are reasonably accurate despite occasional large outliers. As the number of transmitters increases, the localization accuracy improves rapidly. With three transmitters, the mean error drops by more than 60%, and both median and maximum errors decrease substantially. For four and five transmitters, LAUL achieves consistent sub-decimeter median errors and limits worst-case errors to below 1 m. This behavior demonstrates the ability of the learning-based model to exploit measurement redundancy and absorb physical parameter uncertainty. To visually assess localization performance, we present scatter plots in Figure 7 comparing the predicted sensor coordinates against the corresponding ground-truth for a transmission count of 5.

Table 3.

Flat-Surface Localization Performance Using LAUL.

Figure 7.

Actual vs. predicted underwater sensor locations under flat-surface conditions (LAUL, 5 transmitter positions, 100 sample).

The localization results in Table 4 are obtained using the multilateration-based framework developed in our prior work on air-assisted underwater localization using visible light communication [9]. That model derives sensor position by inverting closed-form optical intensity expressions under the assumption of a flat air–water interface and applies trilateration or multilateration when more than three airborne transmissions are received. The results in Table 3 exhibit significantly higher localization errors than LAUL across all transmitter configurations. With two transmitters, both mean and median errors exceed 1 m, indicating that large errors are typical rather than rare. Although increasing the number of transmitters improves performance, the reduction in error is gradual, and substantial residual error remains even with five transmitters.

Table 4.

Flat-Surface Localization Performance Using multilateration-based Localization.

A direct comparison between Table 3 and Table 4 reveals a consistent and substantial performance advantage for LAUL. Across all transmitter counts, the underlying MLP model achieves approximately 2–3 times lower mean and median errors than the multilateration method. The improvement is most pronounced for lower transmitter counts, where multilateration suffers from severe geometric ambiguity and nonlinear error amplification. The maximum error metric further highlights this difference. While both approaches experience larger errors in unfavorable geometric configurations, LAUL consistently limits worst-case errors more effectively. This reflects the fundamental difference between the two approaches: the multilateration method must explicitly invert nonlinear optical equations, where small physical parameter errors are amplified, whereas the MLP model learns a robust inverse mapping directly from noisy data and implicitly compensates for correlated uncertainties.

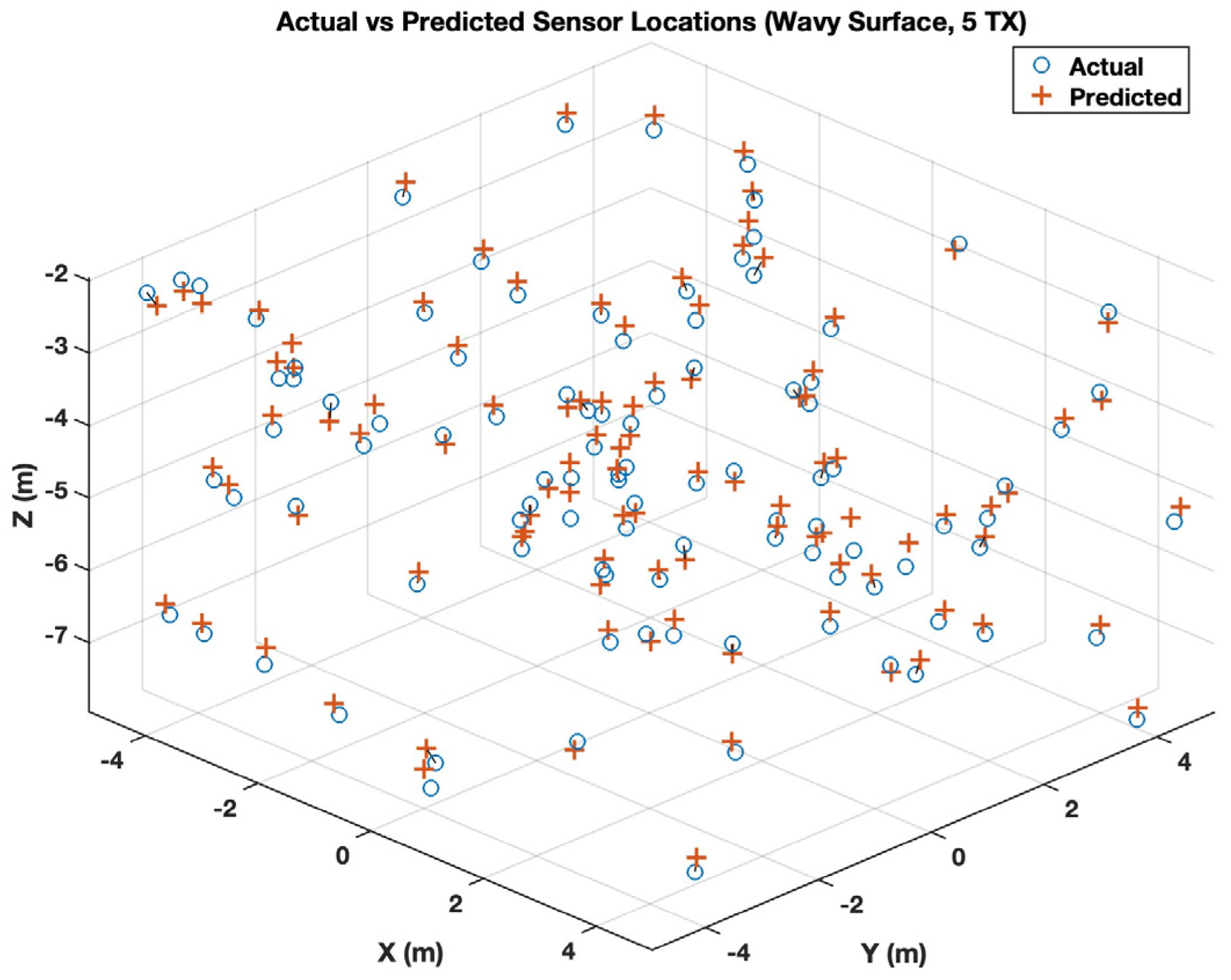

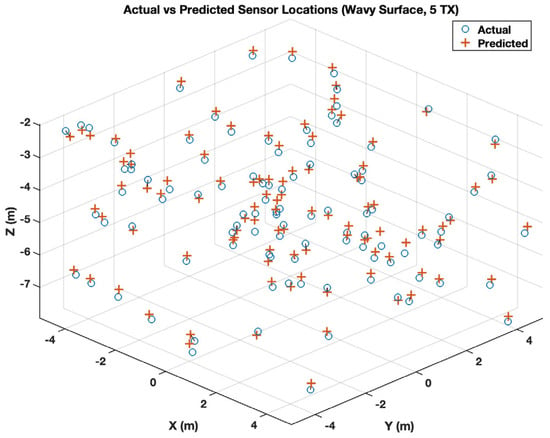

Wavy Surface Scenario: Next, we evaluate the performance of LAUL under wavy-surface conditions, where the air–water interface is dynamically modulated and optical propagation is subject to phase-dependent refraction and spatially varying surface normals. In contrast to the flat-surface case, the wavy-surface environment introduces additional nonlinear distortions in the received intensity patterns, posing a more challenging inference problem. Table 5 summarizes the localization accuracy achieved by LAUL under wavy-surface conditions with injected physical parameter uncertainties, as mentioned above.

Table 5.

Wavy-Surface Localization Performance Using LAUL.

Several important trends emerge from these results. First, localization performance under wavy-surface conditions degrades relative to the flat-surface baseline, which is very much expected. With two transmitters, the mean localization error increases to approximately 0.89 m, and the median error approaches 0.80 m, reflecting the combined effect of weak geometric constraints and phase-dependent surface distortion. The corresponding maximum error exceeds 3.7 m, indicating that unfavorable wave-induced refraction can significantly distort intensity cues in sparsely constrained scenarios.

As the number of transmitters increases, localization accuracy improves substantially. With three transmitters, the mean error drops to 0.43 m, representing more than a 50% reduction relative to the two-transmitter case. Both median and maximum errors decrease sharply, demonstrating that additional spatial diversity helps mitigate wave-induced ambiguity. This improvement continues for four and five transmitters, where the median error stabilizes around 0.21–0.27 m, and the maximum error falls below 1.2 m. Interestingly, the improvement from three to four transmitters is modest in terms of mean error, suggesting that wave-induced variability can partially limit the benefit of additional measurements once a sufficient level of geometric diversity is achieved. Nevertheless, the five-transmitter configuration achieves the best overall performance, with a mean error of 0.36 m and a median error of 0.21 m, indicating that higher redundancy remains beneficial in suppressing extreme outliers.

Overall, the observed error distributions reveal that LAUL remains robust under wavy-surface conditions despite the absence of explicit surface state information during inference. The relatively small gap between mean and median errors across all configurations suggests that most localization estimates remain clustered around the true sensor position, while larger errors arise only in a limited number of unfavorable phase and geometry combinations. The scatter plots in Figure 8 provides a visual comparison between the predicted sensor coordinates and the corresponding ground-truth when the sensor receives five transmissions.

Figure 8.

Actual vs. predicted underwater sensor locations under wavy surface conditions (LAUL, 5 transmitter positions, 100 sample).

Comparison with existing work: As a baseline for comparison, we have considered the work of Fang et al. [30], also discussed earlier in Section 2. We reformulated such a work as a measurement function for localization.

To model a realistic wind-driven air–water interface, this work adopts the Pierson wavy-surface formulation used in Fang et al. [30], in which the ocean surface is represented as a stochastic spatiotemporal process synthesized via a superposition of harmonic wave components across discretized frequency and direction bins. The surface elevation is expressed as

where and denote the number of discretization levels along frequency and direction, respectively, is the angular frequency of the -th component, is its propagation direction, and is a uniformly distributed random phase. The wavenumber , associated with the angular frequency , is obtained using the deep-water dispersion relation , where is gravitational acceleration. The component amplitudes are determined by the directional wave spectrum as

with . Following Fang et al. [30], the frequency spectrum is modeled using the Neumann-type wind-dependent expression as

while the directional spreading is captured by . Importantly, the wind speed enters explicitly through , thereby controlling the overall wave energy distribution and directly influencing the statistical characteristics of the generated surface, including wave height, surface slope, and spatiotemporal variability. As increases, the synthesized interface exhibits stronger fluctuations and steeper local slopes, which in turn produce more pronounced surface-induced refraction and higher variability in the underwater optical field.

The received optical signal is treated as a stochastic function of the unknown underwater sensor position, with randomness arising from the PM-modeled surface realizations. For any candidate sensor location, the forward channel model is evaluated across multiple surface realizations to obtain expected signal statistics and wave-induced variability. Localization is then formulated as an inverse estimation problem in which the sensor position is inferred by matching measured signal patterns to those predicted by the wavy-surface channel model. This results in an RSS-based localization framework that is fully consistent with the underlying wave physics and does not rely on flat-surface assumptions or heuristic noise modeling. While such an analytical approach provides a physically interpretable baseline, it remains fundamentally limited by the complexity of surface-induced distortions. In essence, the PM-modeled surface introduces highly nonlinear, non-Gaussian, and phase-dependent variations in the received signal, which are difficult to invert analytically, particularly under rough sea states or when the number of transmitters is limited.

To evaluate localization performance under realistic ocean conditions, we have compared LAUL with the baseline method, derived based Fang et al. [30], across three representative sea states: calm (3 m/s), moderate (7 m/s), and rough (12 m/s) wind conditions. These wind speeds correspond to increasing surface roughness and wave-induced variability as defined by the PM spectrum. For each state, localization accuracy was evaluated using two to five airborne transmitters, and the mean three-dimensional localization error was recorded. Table 6 summarizes the localization performance of both methods. Across all sea states and transmitter counts, LAUL consistently outperforms the baseline method.

Table 6.

Mean 3D Localization Error (m) under Wavy Surface Conditions for PM wave.

As expected, the localization error increases with wind speed for both methods due to stronger surface-induced refraction, beam steering, and intensity fluctuations. Under calm conditions (3 m/s), the baseline method exhibits mean errors ranging from 1.183 m (2 transmissions) to 0.257 m (5 transmissions), whereas LAUL reduces these errors to 1.028 m and 0.189 m, respectively. This corresponds to an average improvement of approximately 13–26%, even in relatively benign surface conditions. Under moderate wind conditions (7 m/s), the impact of surface dynamics becomes more pronounced. The error increases significantly for the baseline method, particularly for lower transmitter counts, reaching 1.653 m for 2 transmissions. In contrast, LAUL limits the error to 1.138 m, achieving a reduction of approximately 31%.

Similar improvements are observed for higher transmitter counts, indicating that LAUL effectively mitigates wave-induced distortions beyond what is achievable through analytical inversion alone. In rough sea conditions (12 m/s), where the surface exhibits large slopes and rapid spatiotemporal variation, the limitations of the baseline method become most evident, where the mean localization error exceeds 2.35 m for 2 transmitters and remains above 0.55 m even with 5 transmitters. Meanwhile, LAUL consistently achieves substantially lower errors, reducing the mean error to 1.626 m and 0.396 m for the two and five transmissions cases, respectively. The relative improvement in this regime ranges from approximately 30% to 40%, demonstrating the robustness of LAUL under highly dynamic surface conditions.

For both localization methods, increasing the number of transmitters improves accuracy by enhancing geometric diversity and reducing ambiguity in the inverse localization problem. However, the rate of improvement diminishes beyond three transmitters, particularly under rough surface conditions. This saturation effect arises because additional transmitters are subject to similar wave-induced perturbations, limiting the benefit of redundancy. Notably, LAUL consistently achieves the same level of accuracy with one fewer transmitter compared to the baseline method. For example, under moderate conditions, the proposed method with three transmitters (0.456 m) outperforms the baseline method with four transmitters (0.464 m). This highlights the efficiency of LAUL in extracting useful localization information from distorted intensity measurements.

The superior performance of LAUL can be attributed to its ability to implicitly account for wave-induced nonlinearities and higher-order interactions that are difficult to model analytically. While the baseline method relies on explicit inversion of a forward channel model, it remains sensitive to the wave phase of the water surface, local curvature, and stochastic intensity fluctuations. In contrast, LAUL learns a wave-averaged inverse mapping by leveraging a large ensemble of surface realizations, enabling it to suppress systematic biases and reduce sensitivity to instantaneous surface conditions. Overall, these results demonstrate that incorporating physically grounded wave statistics into a learning-based localization framework provides a substantial advantage over purely analytical methods, particularly in dynamic and rough ocean environments. Therefore, LAUL represents a practical and scalable solution for underwater optical localization under realistic sea surface conditions.

For both flat and wavy surfaces, increasing the number of transmitter positions improves localization accuracy by enhancing spatial diversity and reducing ambiguity in the inverse mapping; however, it also increases operational overhead. In practice, the number of transmitter positions could be limited by the size of the coverage area (time for the UAV to scan the area), UAV energy and mission time, and the desired localization latency and accuracy. Therefore, 2–3 transmitter positions represent a low-overhead operating point, while 4–5 positions provide improved accuracy and robustness with diminishing gains per additional transmission.

Model Complexity: Table 7 quantifies the computational characteristics of the proposed LAUL framework as the number of transmitters increases from two to five. The second column denotes the total number of input features supplied to the model, while H1, H2, and H3 represent the neuron counts of the three hidden layers of the MLP. As expected, the input dimensionality grows linearly with the number of transmitters, since each transmitter contributes five features (received intensity, three-dimensional coordinates of the node position, and transmitted power). To accommodate this increase in input size while maintaining sufficient representational capacity, the widths of the three hidden layers were scaled proportionally, whereas the network depth was kept fixed.

Table 7.

Runtime complexity assessment of LAUL under various parameter settings.

This design choice results in a gradual increase in the number of trainable parameters, from approximately for the two-transmitter configuration to for five transmitters. Despite this growth, the overall model size remains modest, staying well below one million parameters even in the largest configuration. Training times vary only slightly across configurations and stay under two minutes in all cases. Since training is performed offline, this cost does not impact operational performance and can be gradually written off over long deployment periods.

Crucially, the inference latency reported in the last column of Table 5 remains consistently low across all configurations. The average per-sample inference time is in the order of and shows no monotonic increase with the number of transmitters. This indicates that the added computational burden from wider hidden layers and higher-dimensional inputs has a negligible impact on real-time execution. In practice, this enables localization to be performed orders of magnitude faster than typical sensing or communication timescales.

All experiments were conducted on a MacBook Pro (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) equipped with an Apple M3 Pro chip, featuring an 11-core CPU, a 14-core GPU, and 18 GB of unified memory, using MATLAB R2023b and the Deep Learning Toolbox. Taken together, these results demonstrate that LAUL achieves a favorable balance between localization accuracy and computational efficiency. The combination of compact model size, short training time, and ultra-low inference latency makes the framework well-suited for resource-constrained underwater sensor nodes, where processing capability, energy consumption, and response time are critical constraints.

7. Conclusions

This study has presented LAUL, a hybrid optical–learning framework for underwater localization that integrates physical modeling of light transmission with machine learning inference. By combining geometric optics with a third-order Stokes surface representation, the proposed system accurately captures the effects of refraction, attenuation, and wave-induced surface variation. The physically grounded data generation process enabled a multi-layer perceptron network to learn a stable mapping between received intensity and spatial position without requiring real-world calibration. Results from both flat and wavy surface simulations have demonstrated that LAUL generalizes effectively across distinct geometric conditions, maintaining high precision and convergence stability. Future work will extend this framework to time-varying localization of mobile underwater nodes by incorporating temporally correlated wave dynamics and sequential measurements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.S., M.Y. and T.M.A.; methodology, J.B.S., M.Y. and T.M.A.; validation, J.B.S., M.Y. and T.M.A.; formal analysis, J.B.S., M.Y. and T.M.A.; investigation, J.B.S., M.Y. and T.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.S., M.Y. and T.M.A.; writing—review and editing, J.B.S. and M.Y.; visualization, J.B.S., M.Y. and T.M.A.; supervision, M.Y. and T.M.A.; project administration, M.Y.; funding acquisition, M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Saeed, N.; Celik, A.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y.; Alouini, M.-S. Underwater optical wireless communications, networking, and localization: A survey. Ad Hoc Netw. 2019, 94, 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhari, M.; Ibrahimi, K.; Tembine, H.; Ben-Othman, J. Underwater wireless sensor networks: A survey on enabling technologies, localization protocols, and Internet of Underwater Things. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 96879–96899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshitij, K.; Tyagi, P.; Gupta, N. Underwater wireless communication system with the Internet of Underwater Things. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICSC), Noida, India, 28–30 November 2022; pp. 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, G.S.; Cozzella, L.; Leccese, F. Underwater optical wireless communications: Overview. Sensors 2020, 20, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Z.; Tang, X.; Yang, Y.; Yu, C.; Fu, H.Y. Optical communication and positioning convergence for flexible underwater wireless sensor network. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 5321–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarabalan, B.; Shanmugam, P.; Ahn, Y.-H. Modeling the underwater light field fluctuations in coastal oceanic waters: Validation with experimental data. Ocean Sci. J. 2016, 51, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, J. Study on the polarization pattern induced by wavy water surfaces. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Younis, M.F. Analyzing visible light communication through air–water interface. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 123830–123845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, J.B.; Younis, M. Underwater localization using airborne visible light communication links. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Madrid, Spain, 7–11 December 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Saif, J.B.; Younis, M.; Choa, F.-S.; Ahmed, A. Localization of autonomous underwater vehicles using airborne visible light communication links. In Proceedings of the 32nd Wireless and Optical Communications Conference (WOCC), Newark, NJ, USA, 9–10 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Saif, J.B.; Younis, M.; Choa, F.-S.; Ahmed, A. Global positioning of underwater nodes using airborne-formed visual light beams. Opt. Commun. 2025, 595, 132348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Saif, J.; Younis, M.; Choa, F.-S. Three-dimensional localization of underwater nodes using airborne visible light beams. Photonics 2025, 12, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, P.A. Ocean surface roughness from satellite observations and spectrum modeling of wind waves. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2022, 52, 2143–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darecki, M.; Stramski, D.; Sokolski, M. Measurements of high-frequency light fluctuations induced by sea surface waves with an underwater porcupine radiometer system. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2011, 116, C00H09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Chattopadhyay, A.K. Stokes waves revisited: Exact solutions in the asymptotic limit. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2016, 131, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nain, M.; Goyal, N.; Dhurandher, S.K.; Dave, M.; Verma, A.K.; Malik, A. A survey on node localization technologies in UWSNs: Potential solutions, recent advancements, and future directions. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2024, 37, e5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Martínez, J.-F.; Meneses Chaus, J.; Eckert, M. A survey on underwater acoustic sensor network routing protocols. Sensors 2016, 16, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmad, R.; Alraie, H.; Hasaba, R.; Eguchi, K.; Matsushima, T.; Fukumoto, Y.; Ishii, K. Performance analysis of underwater radiofrequency communication in seawater: An experimental study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Lai, M. A review on electromagnetic, acoustic, and new emerging technologies for submarine communication. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 12110–12125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Yoon, K.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Cho, I.-K. Magnetic induction-based wireless communication for challenging environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference (APMC), Bali, Indonesia, 3–6 December 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Theocharidis, T.; Kavallieratou, E. Underwater communication technologies: A review. Telecommun. Syst. 2025, 88, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Fu, M.; Zheng, B. Analysis of wavy surface effects on the characteristics of wireless optical communication downlinks. Opt. Commun. 2022, 507, 127623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. Research on underwater acoustic source localization based on typical machine learning algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Song, Y.; Kong, Z.; Lim, E.; Lopez-Benitez, M.; Ma, F.; Yu, L. Underwater target detection and localization with feature map and CNN-based classification. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Advances in Computer Technology, Information Science and Communications (CTISC), Suzhou, China, 22–24 April 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Singer, A.C.; Wornell, G.W. Towards robust data-driven underwater acoustic localization: A deep CNN solution with performance guarantees for model mismatch. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Tang, J.; Yan, Z. Underwater acoustic source localization using LSTM neural network. In Proceedings of the 39th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shenyang, China, 27–29 July 2020; pp. 7452–7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.-F.; He, B.; Guo, J. Position correction model based on gated hybrid RNN for AUV navigation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 5648–5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, W.; Zhu, W.; Qiu, Y. A hybrid localization algorithm for underwater nodes based on neural network and mobility prediction. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 26731–26742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Li, F.; Khan, Z.U.; Khan, F.; Khan, J.; Khan, S.U. Exploration of contemporary modernization in UWSNs in the context of localization including opportunities for future research in machine learning and deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K. Investigation of non-line-of-sight underwater optical wireless communications with wavy surface. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 4799–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegel, R. A presentation of cnoidal wave theory for practical application. J. Fluid. Mech. 1960, 7, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L.-F.; Dingemans, M.W. Derivation of the third-order evolution equations for weakly nonlinear water waves propagating over uneven bottoms. Wave Motion 1989, 11, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.