Abstract

Techno-economic analysis (TEA) plays a vital role in assessing the feasibility and scalability of emerging technologies, especially in the context of innovation and development. Central to any effective TEA is a reliable and detailed model of capital and operational costs. This paper reports the development of such a model for optical networks in the framework of the SEASON project, aimed at supporting a broad spectrum of techno-economic evaluations. The model is constructed using publicly available data and expert insights from project participants. Its generalizable design allows it to be used both within the SEASON project and as a reference for other studies. By harmonizing assumptions and cost parameters, the model fosters consistency across different analyses. It includes cost and power consumption data for a wide range of commercially available optical network components (including transceivers for point-to-multipoint communications), introduces a statistical framework for estimating values for emerging technologies, and provides a cost model for multiband-doped fiber amplifiers. To demonstrate its practical relevance, the paper applies the model to two case studies: an evaluation of how the cost of various multiband node architectures scales with network traffic in meshed topologies and a comparison of different transport solutions to carry fronthaul flows in the radio access network.

1. Introduction

In the realm of innovation and technology development, techno-economic analysis (TEA) serves as a critical tool for evaluating the viability and scalability of emerging technologies. At the heart of any meaningful TEA lies a robust and comprehensive capital and operating cost model. This model should not merely be a financial exercise. It is a framework that informs strategic decisions, guides research priorities, and ultimately determines the commercial potential of a technology [1,2]. Moreover, a well-structured cost model enables benchmarking against existing technologies and industry standards.

A comprehensive cost model captures all relevant capital and operational expenditures (CAPEX and OPEX, respectively). By encompassing both fixed and variable costs, the model provides a realistic picture of the financial landscape across different production scales and market scenarios. The robustness of a cost model is equally vital. It must be built on accurate, up-to-date data and validated assumptions.

In summary, a robust and complete cost model transforms TEA from a theoretical exercise into a powerful decision-making tool. It bridges the gap between laboratory innovation and market implementation, ensuring that technological breakthroughs are not only scientifically sound but also economically feasible and strategically aligned with broader societal needs.

Cost modeling is a powerful tool in techno-economic analysis, but it comes with several challenges that can affect the accuracy, reliability, and usefulness of the results. Table 1 presents some of the most common challenges, their impact on the TEA, and suggestions on how to mitigate them [3]. A critical issue is the availability and quality of data, as reliable cost information for emerging technologies is often limited, outdated, or proprietary, leading to potentially misleading results if not validated. Uncertainty and variability in input parameters further complicate analyses, since fluctuating values can reduce the reliability of projections unless stochastic approaches such as Monte Carlo simulations are applied. The inherent complexity of multi-step systems also presents difficulties, as overly simplified models risk omitting key cost drivers while excessively detailed ones may obscure insights; modular approaches can help balance detail with usability. Scale-up assumptions pose another challenge, as extrapolating from laboratory or pilot data to industrial scale introduces uncertainty that requires benchmarking and sensitivity analysis. Additionally, regional and temporal variability means that cost estimates are not universally transferable, necessitating localized and regularly updated models. Finally, the lack of standardization in methodologies and assumptions across studies hinders comparability, underscoring the importance of following established guidelines and explicitly stating all assumptions.

Table 1.

Challenges of cost modeling, their impact on the TEA, and mitigation suggestions.

Moreover, cost modeling in optical networks has evolved significantly through joint efforts among academia, industry, and network operators. Notable initiatives such as the STRONGEST [4], IDEALIST [5], and Metro-Haul [6] projects have contributed valuable methodologies and data sets for estimating costs across various segments of the network. In particular, the Metro-Haul project developed a widely referenced cost model for techno-economic analyses in metro-access networks [7].

More recently, the B5G-Open [8] project introduced a suite of techno-economic models covering long-haul, metropolitan, and metro-aggregation domains. However, those models are standalone and tailored to specific use cases. Additional research published in journals and conferences also presents cost models, though these are typically confined to their respective domains and often rely on distinct methodologies for cost value estimation [9,10,11].

This paper advances cost modeling in optical networks by presenting a unified model that overcomes key limitations of prior approaches. Previous initiatives have delivered valuable datasets; however, their models are generally domain-specific, standalone, and based on heterogeneous assumptions and estimation techniques. Moreover, they lack timely updates, which is critical given the rapid evolution of communication technologies. In contrast, the proposed model integrates multiple network segments and device types within a consistent and transparent methodology, ensuring interoperability and methodological coherence and providing up-to-date values for commercial devices.

A key innovation of this work lies in the inclusion of current commercial device data, providing accurate and up-to-date values derived from market sources. Furthermore, the model introduces two estimation frameworks: one for extrapolating costs and performance for devices requiring incremental improvements in existing technologies, and another for forecasting values for devices that demand entirely new technological developments.

These frameworks extend the applicability of the model beyond commercially available solutions, enabling robust techno-economic analyses for both present and future network scenarios. By promoting methodological consistency and offering mechanisms for adaptation and expansion, the proposed model not only supports the SEASON project’s [12] objectives but also serves as a reference architecture for future research. This approach addresses the lack of standardization in cost modeling and fosters collaboration across academia and industry, ultimately enhancing reproducibility and comparability in techno-economic studies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the methodology adopted for the development of the generalized cost model, including general multilayer network model architecture, data sourcing strategies, modeling approaches, and treatment of uncertainty. The section further details the collection and normalization of cost and power consumption values for commercially available devices, such as transceivers, amplifiers, Layer 3 switches, routers, and compute/storage systems. It also outlines the extrapolation framework for estimating costs of future technologies and introduces an approach for modeling multiband (MB) optical amplifiers. Section 3 demonstrates the applicability of the proposed cost model through two case studies. The first evaluates capital expenditure savings of multi-granular and modular node architectures for high-capacity multiband and space-division multiplexed (SDM) networks. The second compares alternative transport solutions for fronthaul traffic in the radio access network, analyzing both capital costs and energy consumption across different deployment scenarios. Other applications of the cost model can be found in the SEASON project deliverables [12] (especially D2.3). Finally, Section 4 summarizes the main conclusions and highlights future directions for extending the cost model towards broader techno-economic analyses.

2. Methodology

This section presents the network model used to describe the assignment of devices and systems to the various network layers, as well as the connections between them in Section 2.1. Then, it describes the methodology utilized to collect the information available in the cost model in order to facilitate comparison with future studies that should follow a similar strategy, in an attempt to reduce the impacts of Challenge 6. It characterizes the framework for sourcing reliable data from publicly available online resources and expert consultations within the project partners (addressing Challenges 1 and 2), discusses the trade-offs between model complexity and accuracy (Challenge 3), and highlights the regional specificity of the data employed (Challenge 5) in Section 2.2. It also outlines a recommended methodology for extrapolating existing data to account for non-commercial or future equipment, such as higher-capacity transceivers (Challenge 4) in Section 2.3. Lastly, the section introduces a modeling framework for estimating the cost and power consumption of doped-fiber optical amplifiers operating in transmission bands beyond the conventional C-band (Section 2.4). A similar framework can also be applied to predict the values of other devices that rely on emerging technologies.

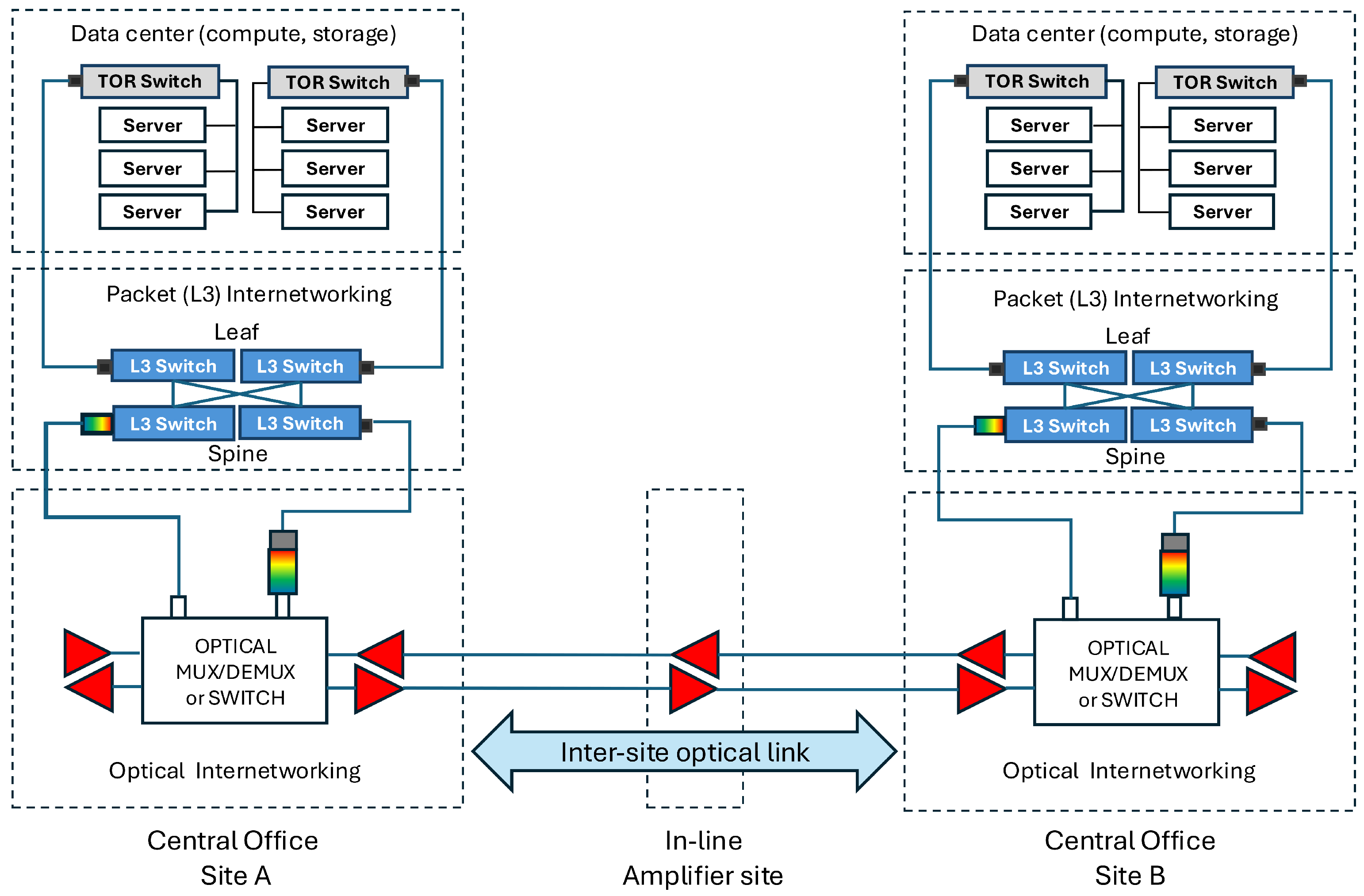

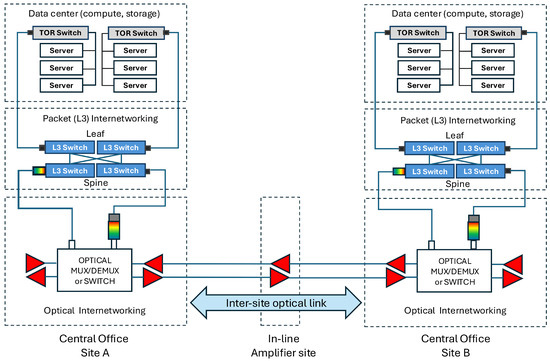

2.1. Network Model Architecture

The network model architecture (Figure 1) is organized into three main layers: the compute and storage layer (data center), the packet networking layer (typically Layer 3, IP), and the optical layer. In the figure, the equipment belonging to these three layers is located in the central offices A and B, which are interconnected by a fiber inter-site link that may require one or more intermediate optical amplification stages, depending on the link length. In-line amplification is represented by an intermediate site hosting the amplifiers. In general, a network is a complex system comprising multiple central offices interconnected in a mesh or ring topology and typically organized into hierarchical levels (e.g., access, aggregation, metro core, backbone). The scheme in Figure 1 provides a concise and functional representation of the cost model discussed in this article. More comprehensive and detailed modeling, useful in network design and planning contexts, is beyond the scope of this work.

Figure 1.

Model for the network layered architecture made of compute/storage (cloud), packet (IP) and optical layers. The figure shows two central office sites, A and B, each including the complete layer stack, interconnected by an optical link requiring an intermediate optical amplification.

At the top of Figure 1, the data center (DC) component is shown, consisting of servers and top-of-rack (TOR) switches (typically Layer 2 switches). This component hosts compute functions (performed by CPUs or GPUs, with the latter also supporting Artificial Intelligence (AI) workloads) and storage functions. Depending on cloud architecture (centralized or distributed), the DC can be large (Central DC), medium (Edge DC), or small (Far Edge DC). In some central offices, the DC component may be absent if its deployment is not planned.

The intermediate layer represents the layer of packet internetworking, shown in Figure 1 with Layer 3 switches arranged in a leaf–spine topology, which is typical, although not exclusive, for packet internetworking. The spine switches are connected to the data center TOR switches (or to other access devices) via gray transceivers. The leaf switches are connected to the optical network either through gray transceivers interfacing with transponder modules that connect to the optical switch/multiplexer or through colored transceivers directly connected to the ports of the optical switch/multiplexer. The choice between these two options depends on the selected IP-over-WDM architecture, i.e., a traditional approach with transponder modules on the optical node or a pluggable-optics approach with colored transceivers inserted directly into the packet switches and connected to the optical switch/multiplexer.

The optical layer, shown at the bottom, consists of multiplexing and switching systems, transponders, and optical amplifiers. The switching or multiplexing function can be implemented using different technologies and architectures, for example, a reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) based on wavelength-selective switches (WSS). Transponders are cards that adapt a gray client signal (typically from a packet switch) to a colored signal suitable for multiplexing on the WDM line. The depicted architecture is an IP-over-optical solution without an OTN photonic switching layer. If an OTN layer were present, this additional layer, with its devices and related interconnections, would also need to be modeled.

The interconnection of devices within a central office, between devices of the same layer or adjacent layers, is achieved with intra-site links, usually made with fiber optic cables.

In the optical layer, the inter-site fiber links are represented in Figure 1 by pairs of fibers carrying two unidirectional signals, one for each transmission direction (EAST–WEST and WEST–EAST). Amplification is represented by pairs of optical amplifiers, which are required for links whose length causes attenuation beyond the maximum sensitivity of the receiving device (transponder or colored transceiver). Multiple intermediate amplification stages may be required, including those used for transparent optical node crossing, but the signal must still be received with an adequate signal-to-noise ratio, which ultimately sets the maximum length of a transparent lightpath. When the signal-to-noise ratio of an optical signal along its path falls below the allowable threshold, an optical–electrical–optical regeneration stage is required.

2.2. Commercially Available Devices

One of the most common challenges in cost modeling is the lack of accurate and reliable data (Challenge 1). Since data forms the foundation of any cost model, insufficient or imprecise information can lead to misleading or incorrect results. Therefore, price and power consumption for commercially available systems were gathered from websites that provide them publicly and cross-validated with data provided by various partners involved in the SEASON project but cannot be publicly referenced. It should be noted right away that prices and power consumption can be found fairly easily for widely available items subject to open competition (such as transceivers, packet switches, and servers). However, for equipment that is less widely available, more expensive, and that requires customization and ad hoc offerings (for example, optical nodes and transponders), it is much more difficult to find this information online.

For transceivers and switches, the primary source used to obtain pricing and power consumption data was [13], chosen for its extensive catalog of optical and packet networking devices, competitive pricing, and user-friendly interface for querying products. Additionally, [14] was consulted to gather transceiver data, enabling comparisons and the calculation of average values. For compute and storage components, information was sourced from [15] and supplemented through expert consultations. The data collection and analysis efforts resulted in the cost and power consumption tables presented in the following sections.

It is important to note that the values provided in this article are based on surveys conducted during the first quarter of 2025. As is commonly known, prices may vary over time due to various factors. Moreover, when defining device or system items, some simplification was necessary. Similar items often exist in multiple variants, which may differ significantly in price. To address this, we defined a “typical” item (an abstraction representing the average market offering for a given device or system). Each typical item includes an estimated average price, expected power consumption, and representative performance parameters. These abstractions do not correspond to specific commercial products but rather serve as generalized models for analysis.

The cost values exclude value-added tax (VAT) and are expressed in euros, assuming a European country context. This approach ensures consistency and applicability across different European regions. To further mitigate temporal, geographical, and source-related variations, costs are normalized and presented as ratios relative to a defined cost unit (c.u.) of five thousand euros, rather than as absolute euro values. These normalized values are then compared and validated against internal data from project partners. Power consumption values are reported in watts (W) and represent the maximum device power usage. Unlike cost parameters, power values are not normalized, as geographical or source-dependent variations are not anticipated. Nevertheless, normalization may be applied by third parties seeking to extend or adapt the model.

The objective of the cost model is to be as comprehensive as possible while maintaining accuracy and avoiding excessive complexity. Accordingly, the model focuses on components based on mature, commercially available technologies, grouped into four categories: transceivers, amplifiers, Layer 3 switches and routers, and compute/storage devices. Components for which reliable data could not be obtained are excluded from the model. Similarly, elements with negligible cost impact are not considered.

The following subsections describe the methodology for gathering the information for each component category.

2.2.1. Transceivers

The transceivers are divided into three categories based on their application: gray transceivers, colored transceivers for wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) systems, and coherent digital subcarrier multiplexing (DSCM) transceivers, which allow subcarrier-level capacity allocation, enabling coherent point-to-multipoint (P2MP) communication. The application categories are further divided into reference reach categories as presented in Table 2, where the assignments are as follows: SR is short reach, LR is long reach, ER is extended reach, ZR is extended range/zero dispersion, ZR+ is a variant of extended range/zero dispersion with longer reach, and LH is long haul.

Table 2.

Transceiver reach categories.

Gray Transceivers

Table 3 presents the cost and power consumption of gray transceivers. Data rates from 10 G to 400 G and three reach categories are selected: SR, LR, and ER. SR gray transceivers use multimode fiber, while LR and ER use single-mode fiber. The types of the form factor range from small form-factor pluggable (SFP) to quad SFP-double density (QSFP-DD), depending on the data rate and power consumption. Gray transceivers transmit in the O-band unless otherwise indicated (only one case: 10 G ER C-band).

Table 3.

Gray transceiver cost (in c.u.) and power consumption (in W).

WDM Transceivers

Table 4 reports a selection of WDM colored transceivers for different reaches. All transceivers are based on the Multi-Source Agreement (MSA) form factor and are tuneable in the extended C-band (∼4.8 THz), enabling dense WDM (DWDM) multiplexing (48 to 96 channels), except those specified otherwise, which are 10 G ER and ZR (CWDM, up to 12 channels, and fixed) and 100 G ZR (WDM, 20 channels, and fixed). The 10 G models use non-return-to-zero (NRZ) detection; the 100 G ZR coarse WDM (CWDM) fixed model uses pulse amplitude modulation with four levels (PAM4), while the remaining ones are all coherent. For the 100 G ZR+ transceiver, power consumption is specified for the QSFP-DD form factor. The same device with a smaller form factor (e.g., QSFP28) consumes much less, around 6 W, with comparable performance and cost. Data for 400 G ZR+ is taken from a variable data rate transceiver that can be configured from 100 Gbit per second (Gb/s) to 400 Gb/s. When configured at 100 Gb/s, the reach extends to LH (<2000 km).

Table 4.

WDM colored transceiver cost (in c.u.) and power consumption (in W).

DSCM Coherent Transceivers

Coherent transceivers based on DSCM represent a new type of device that enables flexible networking by allowing P2MP communication [16,17]. The target specifications for this type of device are defined in the OpenXR forum [18].

Currently, commercial offerings are limited to 100 G modules (typically used as leaf modules) and 400 G modules (used as hub modules), both within the ZR+ reach class. As no public price lists for these specific devices were found, pricing estimates were inferred from similar coherent single-carrier modules. For each module type, a range of values is provided for both cost (in c.u.) and power consumption (in W) to account for potential future variability. The minimum price for a DSCM coherent module was assumed to match that of a comparable single-carrier coherent device with the same bit rate and reach class. The maximum price was set at 25% above this baseline. A similar approach was applied to power consumption, with the maximum value set 10% higher than the minimum.

Table 5 presents 100 and 400 Gb/s modules with 4 and 16 subcarriers (SCs), respectively. Each subcarrier supports 25 Gb/s of traffic, and the data rate of a point-to-point (P2P) or P2MP device can be configured with this granularity. Two reach classes, ZR and ZR+, are proposed, corresponding to two different price levels and with slightly different power consumption. Although the coherent technology currently used complies with class ZR+ (with amplification), given the potential applications in the access-metro aggregation segment, the idea was to also introduce the more economical class ZR, which can be achieved with a lower-cost (and lower-performance) implementation. It is not certain whether the market will offer such devices in the future, but the combination of a competitive cost with the advantages of P2MP networking could find the market’s favor.

Table 5.

DSCM transceiver cost (in c.u.) and power consumption (in W).

Of all the transceivers presented in these sections, the coherent DSCM ones are the ones subject to the greatest uncertainty regarding prices and actual market availability. However, we thought it important to include them because this information could be key to realizing meaningful comparisons of transport solutions for access and metro networks.

2.2.2. C-Band Amplifiers

Cost and power consumption estimates for optical amplifiers operating outside the C-band are discussed separately in Section 2.4, as these bands exhibit distinct characteristics. While L-band amplifiers show less uncertainty due to the availability of some commercial devices, future cost values will still be influenced by production volumes and ongoing technological development.

To streamline the model, we reduced the number of devices modeled. Among the factors influencing amplifier pricing, the most significant are the amplification band and the number of amplification stages. Consequently, the model includes cost and power consumption data for both standard C-band (4.0 THz) and extended C-band (4.8 THz) EDFAs, while excluding parameters with lower impact on pricing—such as noise figure, gain, gain flatness, maximum output power, and number of operating modes—since these characteristics tend to be similar across available devices (typical amplifiers used in metro/regional networks).

The cost and power consumption values used in the model represent average values derived from publicly available devices. The values are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Amplifier cost (in c.u.) and power consumption (in W).

2.2.3. Layer 3 Switches and Routers

In view of the benefits of the IP-over-WDM architecture, there has been a significant uptick in its adoption in current and future network deployments. In this architecture, coherent pluggable transceivers are hosted directly in switches or routers. This further motivates us to jointly consider the L0 up to L3 equipment to be deployed.

The data collected and analyzed for packet switches resulted in Table 7, which presents devices categorized as Layer 3 switches. It should be clarified that there are different types of packet switching nodes, and the two main categories are the so-called Layer 3 switches and the IP routers. In fact, Layer 3 switches and IP routers both perform network layer (Layer 3) packet routing, but they differ significantly in their roles, hardware design, and application scope within networks. Layer 3 switches are specialized devices optimized for high-speed internal local area network (LAN) routing and switching, while IP routers are designed to connect different networks and provide advanced wide area network (WAN) and edge capabilities.

Table 7.

Layer 3 switch cost (in c.u.) and power consumption (in W).

The price source used in this case is [13], and the devices are of the gray- or white-box Layer 3 switch for networking. They are equipped with basic software (SW), i.e., the operating system, but do not include the SW necessary for routing and management (which must be quoted separately and in addition). The overall price of a Layer 3 switch ready to operate in a network could be much higher than the cost of the hardware itself (e.g., by a factor of 2 or more). An all-inclusive model is beyond the scope of this work.

Providing pricing for routers is more difficult, as public pricing is less available and is more subject to buyer-seller negotiation and volume. A router with the same raw switching/forwarding capacity as a Layer 3 switch can typically cost 2 to 5 times as much (and sometimes significantly more), depending on features, redundancy, and service contracts. A factor of ×4 can be taken as a general rule of thumb.

The Layer 3 switches in Table 7 are supplied in seven models of different sizes (from the extra extra small, EES, to the extra extra large, XXL), in which the maximum cumulative capacity of interfaces it can host is specified. For example, the S model, which has a total capacity of 1.6 Tb/s, can be equipped with 4 interfaces at 400 Gb/s, or with 16 interfaces at 100 Gb/s (or with other combinations with a sum of 1.6 Tb/s). At full load, and in theory, the switch is capable of switching double the total capacity of interfaces since they are bidirectional (i.e., they allow the nominal data rate to be transmitted in both directions on two separate ports). It must be said that the switch will always switch a smaller fraction of the maximum traffic it can receive from its interfaces, often a significantly smaller fraction (typically less than 50%).

It should be emphasized that the pricing of L3 switches and especially routers is subject to high uncertainty, as it depends on factors such as SW features for packet policy and routing, HW redundancy, and telemetry capabilities, just to give a few examples. These factors are subject to highly variable costs depending on the vendor, model, and configuration. Therefore, the model presented above should be used with caution and awareness.

2.2.4. Compute and Storage

Just as Layer 3 switches are useful for evaluating IP-over-WDM architectures, compute and storage servers are useful for evaluating network solutions that use virtualized Telco and Service functions (such as cloud-based mobile radio access network (RAN), among others). Indeed, for a comprehensive evaluation of all the components involved, evaluation of optical, IP networking, and compute and storage levels is required. A selection of HW elements used in the cloud as compute, storage, and networking card elements to support Telco and Service functions are included in Table 8. The first five rows include server configurations classified according to their size (XS with a single 24-core CPU, S with two 24-core CPUs, and M with two 32-core GPUs) and their memory and GPU cards, if present. Servers with distributed storage have storage units with a total capacity of 10 TBytes. Server configurations are, in reality, countless and subject to rapid evolution over time (think, for example, of the growing need for GPUs for AI applications), so the selection is made purely for illustrative purposes and to allow for a high-level economic evaluation of simple scenarios.

Table 8.

Compute and storage device cost (in c.u.) and power consumption (in W).

The first two servers are suitable for RAN applications and specifically for implementing virtual distributed unit (vDU) functions. Their price difference is due not only to their compute capacity (one or two processors) but also to their network cards, which have different data rate ports (25 G for the first, 100 G for the second). Size M servers are used for standard data center applications or for Telco functions like virtual centralized unit (vCU) or user plane function (UPF). Other items in the table are a graphics processing unit (GPU), whose reference model is Nvidia L40, and cards, standard network interface cards (NICs) and more powerful data processing units (DPUs), which are cards with additional processing capabilities that can relieve the central processing units (CPUs) and speed up processing by performing tasks such as processing, routing, and forwarding functions.

For reasons similar to those given for Layer 3 switches, the cost model for compute and storage equipment is also subject to significant uncertainty, given the very rapid developments in certain components such as GPUs and high-speed network cards with processing power (smart NICs or DPUs). Therefore, even in the case of computing and storage equipment, caution and awareness are required in applying the cost model.

2.3. Cost and Power Consumption Estimation as a Function of Equipment Capacity

The uncertainty of technological evolution is a challenge for techno-economic analysis. Still, predicting the pace and direction of new optical technologies (e.g., new data rate transceivers and higher capacity routers) and their impact on network design in multi-period planning scenarios is often required. Trend analysis and extrapolation, using, e.g., regression analysis, can provide insightful information by analyzing historical pricing data for various optical components (e.g., transceivers of different data rates). Regression analysis is a statistical method used to model the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. It helps to understand how the value of the dependent variable changes when any of the independent variables are varied, allowing for prediction and forecasting.

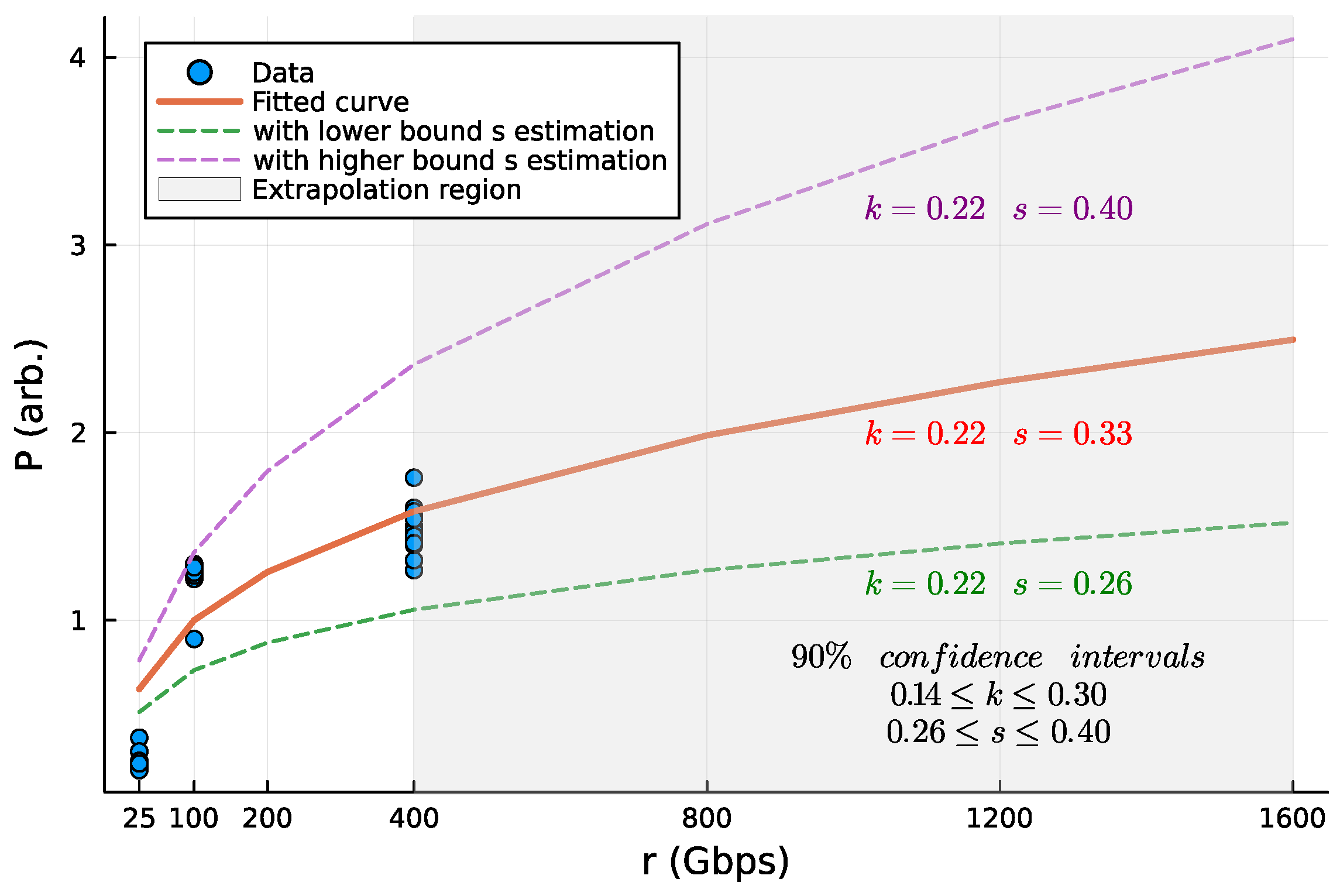

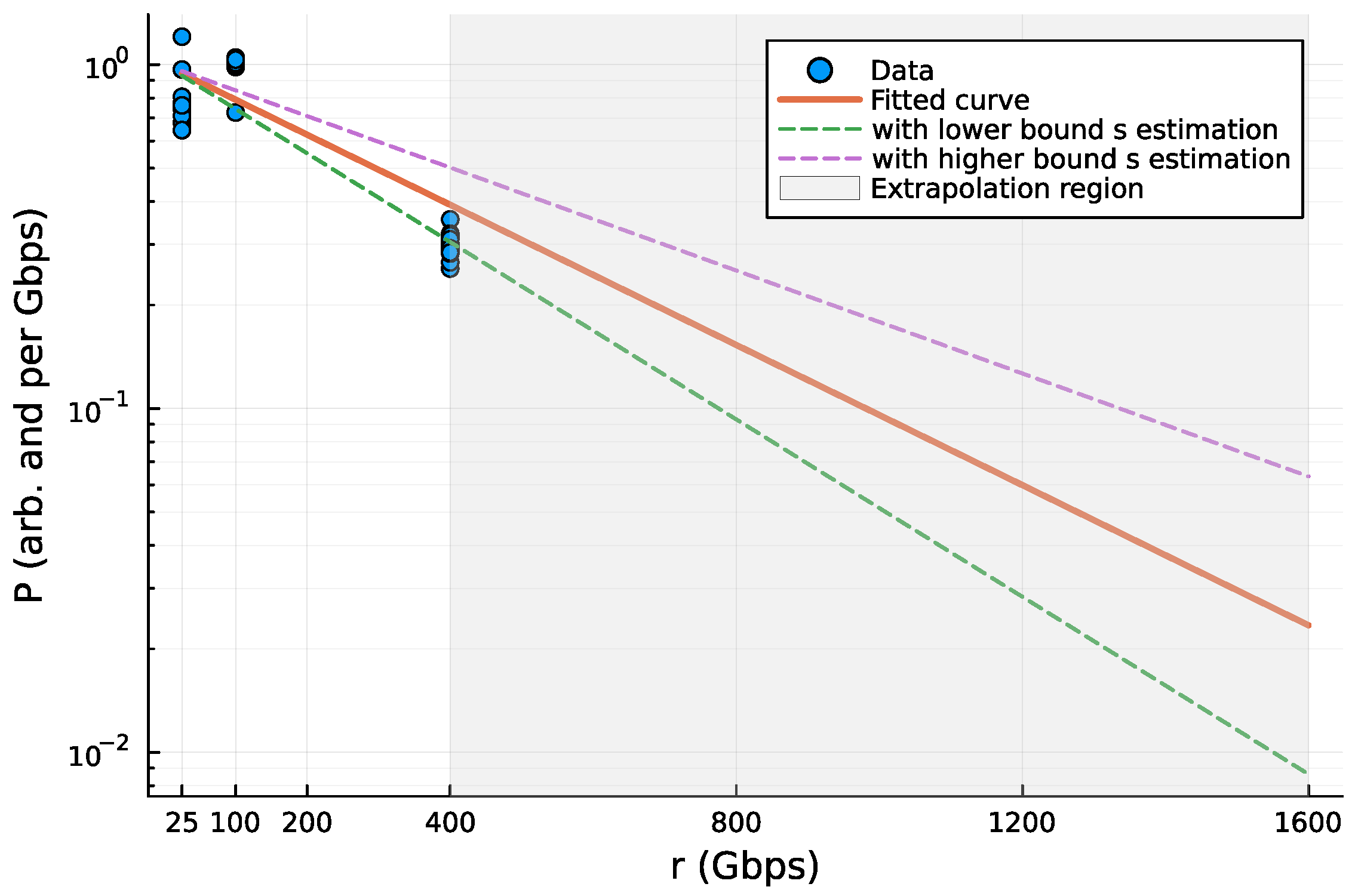

The following example focuses on the coherent long-reach transceiver price, but the method and technique can be applied to other equipment as well. The cost of higher data rate transceivers can be predicted by fitting a curve to available data and then extrapolating for those that do not exist yet in the market. Note that the price of optical transceivers can be modeled using a power law due to cumulative production, capturing the efficiency of manufacturing experience, or alternatively, with exponential decay over time for early-stage technologies with rapid improvements. Empirical data typically guide the choice between the two models for accurate forecasting. The price of a transceiver can be expressed for a power law as follows:

where is the price of transceivers with data rate r Gb/s; , , and are coefficients; and s is an exponent smaller than one. term can model the fixed cost of transceivers, while , and can model the linear and power law trends, respectively. This is because technology tends to become cheaper over time per fixed unit (e.g., per Gb/s, per memory) [19], driven by a powerful synergy between the learning/experience curve (given by the effect of increases in efficiency in production) and scale factors such as economies of scale (increases in production volumes by producers) and scale discounts (increases in sales volumes to customers) [20,21].

Since there is not much data, and for the sake of simplicity, we use a simpler curve and only keep the last term, which is the most important one [21]:

where k, and s are the unknowns and must be estimated to relate data rate r in Gb/s to the normalized price . Nonlinear least squares (NLS) fitting is a statistical technique used to find the best-fit parameters for the above-mentioned nonlinear model.

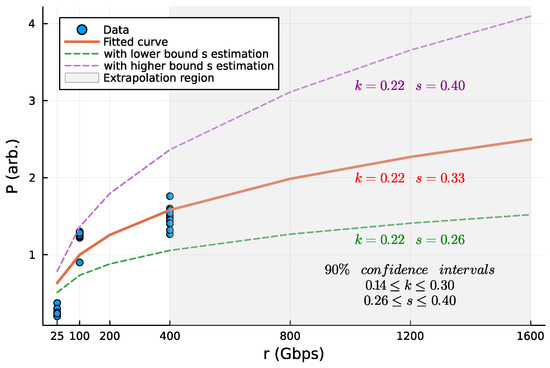

We use a normalized data set with 50 samples, of which only 12 of them are original, and the rest are fabricated. The goal of this analysis is to present a general methodology for cost analysis and extrapolation that can be applied to a wide range of devices. The fabricated data are introduced heuristically solely to clarify the example, admitting that at this stage, it could bias the final results. Figure 2 shows the data set (blue points) and the optimal curve fitted to the normalized data with an arbitrary (arb.) price unit. The developed mathematical framework can be used to estimate k, s and consequently predict higher data rate transceiver prices while providing average values and uncertainty ranges. Also, the 90% confidence intervals for k and s are reported. Obviously, the more data available, the more accurate and less uncertain the model will likely be.

Figure 2.

Curve fitting to a data set of transceiver prices and the confidence intervals.

The coefficient of determination is defined as

where is the residual sum of squares and is the total sum of squares. measures how well the model explains the variance of the data, with values closer to 1 indicating a better fit. For the transceiver cost model provided, we obtained , which shows a moderately good fit.

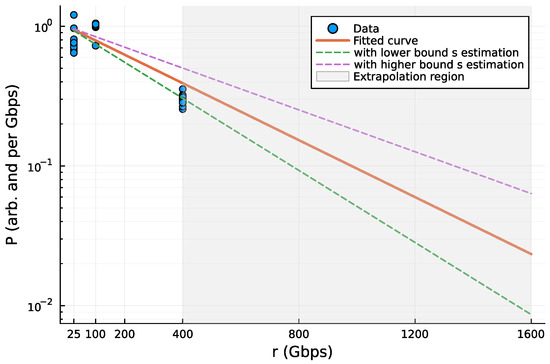

We normalize the price variable by dividing the price by the data rate and fit the parametric model:

This models the exponential decay of technology for a fixed unit [19]. As shown in Figure 3, the negative slope observed on the log-linear plot indicates that the cost per unit of bandwidth for transceivers (price, arb., and per Gb/s) declines exponentially as the data rate (r in Gb/s) increases. This dramatic cost reduction is primarily driven by three intertwined factors: Moore’s Law scaling in silicon and photonic integrated circuits, which reduces the cost of implementing high-speed functions; economies of scale resulting from massive demand, allowing R&D costs to be amortized over high volumes; and architectural innovations like the adoption of better techniques and materials. Note that for this fitting, is 0.66.

Figure 3.

Curve fitting to a data set of normalized transceiver prices and the confidence intervals.

These models can help run more accurate and consistent TEA. Recognizing the inherent sensitivity and scarcity of public pricing data, we proposed that this mathematical framework can bridge the gap, offering a robust benchmark even with limited information. This extrapolation is meant to support comparative and scenario-based analysis and should not be interpreted as an exact cost prediction.

2.4. Method to Estimate the Cost of Amplifiers for Multiband Systems

Optical amplifiers are critical components in long-haul and metro optical networks [22], enabling signal regeneration without electrical conversion. While the C-band remains the most widely deployed due to its favorable gain characteristics and mature component ecosystem, spectrum expansion into adjacent bands is necessary to accommodate future capacity requirements (the widely deployed ITU-T G.652D fiber offers a low-loss transmission spectrum spanning approximately 54 THz from the O- to the L-band [23]). However, realizing this expansion requires addressing additional challenges in terms of cost and power efficiency.

The cost of optical amplifiers outside the C-band is generally higher due to several factors. For instance, the mature, reliable, and cost-effective optical amplifiers widely deployed rely on erbium-doped amplification technology. However, this doping material is only suitable for two of the wavelength bands, namely the C-band and the L-band. Thus, new amplification technologies have to be developed to fully exploit the potential of MB transmission. Building these new amplifiers is complex (alternative doping materials are required) and faces limitations in terms of amplification efficiency and a lack of large-volume production. For instance, the existing component ecosystem is optimized for C-band operation, and hence, components for other bands, such as pump lasers, isolators, and wavelength filters, are either not manufactured or only manufactured on a small scale, leading to higher unit costs. Non-C-band amplifiers also suffer from higher costs due to lower amplification efficiency and more complex designs [24]. For instance, L-band EDFAs require longer erbium-doped fiber lengths and dual-stage configurations to achieve comparable gain and noise performance, increasing both material and integration costs, whereas S-band thulium-doped amplifiers require more complex pumping schemes to avoid self-termination [25].

To account for future uncertainties, ranges of cost and power consumption values are defined. Table 9 summarizes the cost and power consumption increment of MB amplifiers compared to their C-band counterparts. The cost increment primarily reflects the anticipated lower production volumes of amplifiers designed for transmission bands other than C-band.

Table 9.

Cost and power increment for multiband amplifiers in relation to the C-band.

EDFAs can be effectively used in the L-band, resulting in cost and power consumption values that are comparable to those of C-band amplifiers. A cost increment of approximately 5% to 15% is expected due to reduced production volumes, while power consumption is projected to be 5% to 10% higher, attributed to lower power conversion efficiency [22].

For other transmission bands, the model does not incorporate the currently elevated costs associated with emerging technologies, under the assumption that these challenges will be mitigated over time. Instead, the increments reflect differences in production volume and amplification efficiency relative to C-band amplifiers. The model considers multiple production volume scenarios for each band to account for varying adoption rates. Among the bands analyzed, the L-band is expected to see the highest demand for amplifiers due to its similar characteristics and performance to the C-band. This is followed by the O-band, which is anticipated to be more relevant in metro/access networks, the S-band due to its spectral proximity to the L- and C-bands, and finally the E-band. Power consumption increments are estimated based on differences in power conversion efficiency relative to C-band amplifiers [22]. L- and S-band amplifiers exhibit similar efficiencies (about 5% to 10% lower than erbium-based C-band amplifiers), despite requiring different doping materials (erbium and thulium). In contrast, O- and E-band amplifiers, which typically use praseodymium and bismuth, exhibit lower conversion efficiencies, leading to higher power consumption, especially for E-band. The selected materials for each band correspond to those with the highest conversion efficiency reported in [22]. Note that variations in doping materials directly affect power consumption.

3. Application Examples and Discussion

This section presents techno-economic studies to demonstrate the practical relevance of the cost model, including (1) an evaluation of how the cost of various multiband node architectures scales with network traffic in meshed topologies and (2) a comparison of transport solutions to support RAN.

3.1. CAPEX Savings of Node Architectures for High-Capacity MBoSDM Optical Networks

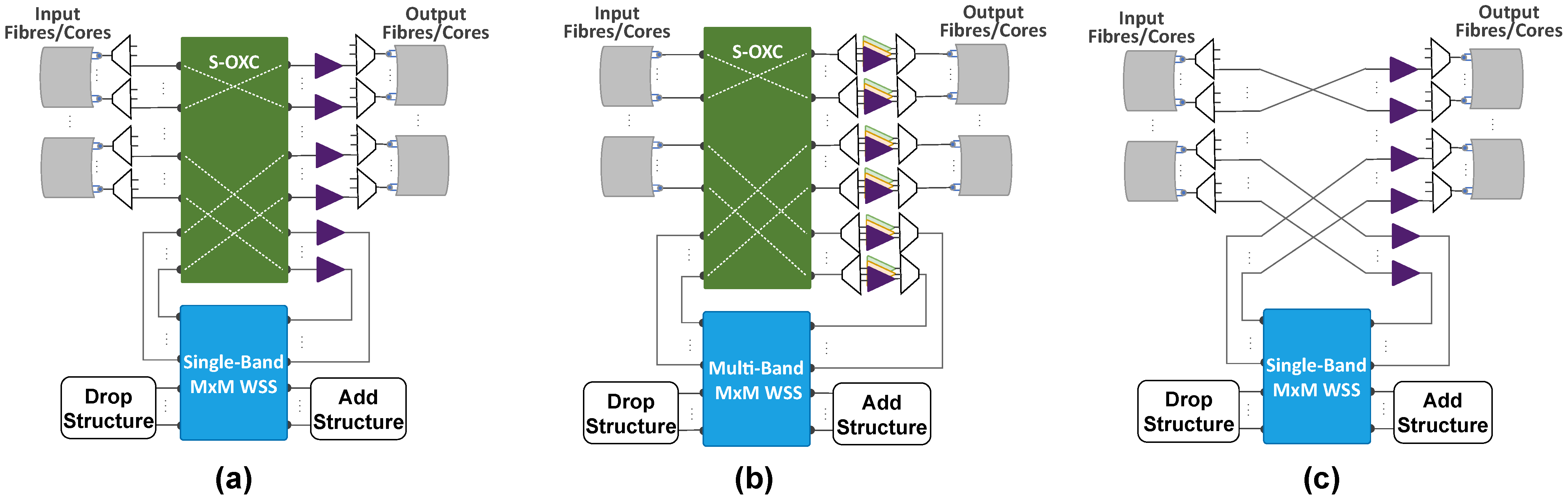

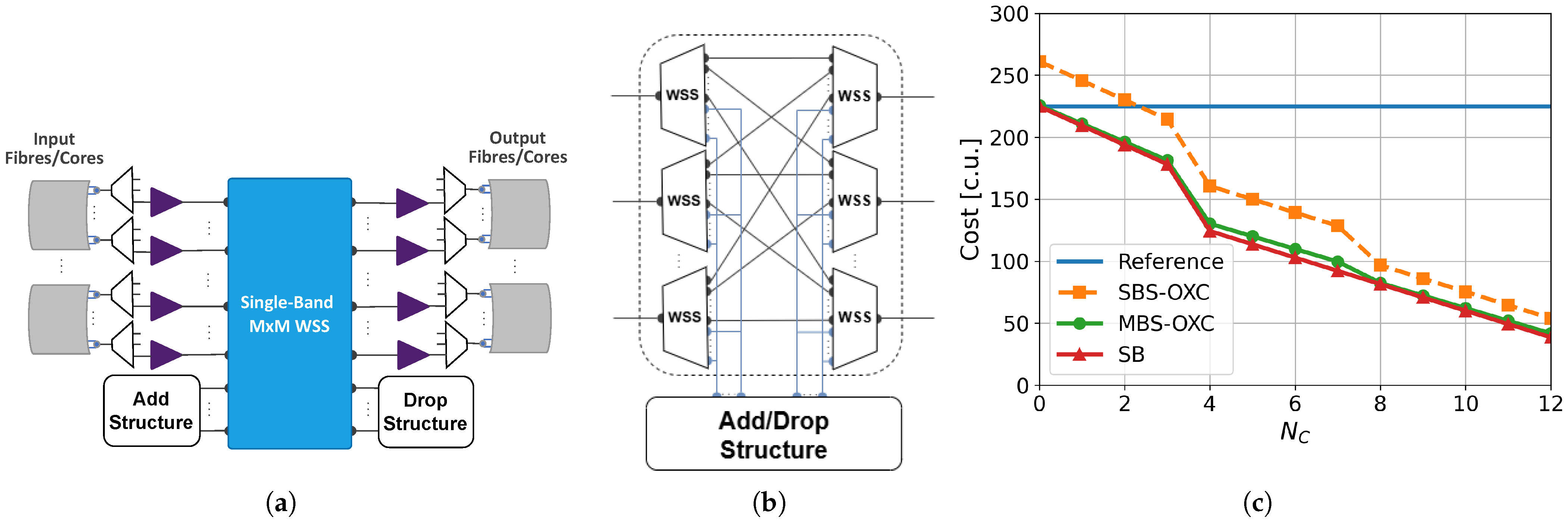

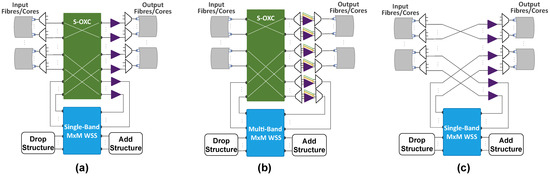

This study assesses the potential cost savings enabled by multi-granular, modular, and adaptable switching network node architectures with advanced capabilities, leveraging MB and SDM technologies. The nodes are designed to meet the growing traffic demands and the rigorous requirements of forthcoming optical networks. Ref. [26] introduced three architectural solutions grounded on current technologies, presenting viable approaches for efficient MB switching over SDM systems (MBoSDM) for the next generation of optical networks (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Node architecture #1 (SBS-OXC): single-band matrix-switch-based MBoSDM node with an S-OXC. (b) Node architecture #2 (MBS-OXC): MB matrix-switch-based MBoSDM node with an S-OXC. (c) Node architecture #3 (SB): single-band matrix-switch-based MBoSDM node without an S-OXC.

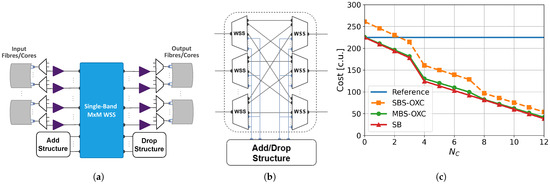

The main simplifying feature of the proposed architectures is the possibility of directly interconnecting cores (bypassing the WSS and the add-drop structure) via physical connections or an S-OXC. This direct connection holds the potential to simplify the node by reducing the WSS and optical amplifier count in relation to a reference architecture that does not allow direct fiber/core switching, such as the one presented in Figure 5a (a more detailed description of all node architectures is presented in [26]).

Figure 5.

(a) Reference node architecture. (b) Schematics of an implementation of an M × M WSS by a concatenation of smaller WSSs in a route and select structure. (c) Cost evolution of the different network node architectures for an increasing number of directly switched core pairs ().

The CAPEX of the node architectures presented in this section depends on the number and cost of S-OXCs, M × M WSSs, and optical amplifiers, assuming that the cost of band filters is negligible (which is the case of band filters used in commercial C+L-band systems).

For simplicity, we assume an equal number of bands per core, denoted by B, and an equal number of fiber cores per degree, denoted by C. Based on these assumptions, equations can be derived to determine the number of ports and devices required for each architecture [26]. Table 10 shows these equations. Here, D represents the nodal degree, denotes the number of core pairs directly switched, and indicates the number of ports of the WSSs connected to the A/D structure. It is worth noting that these figures exclude the A/D structure since the same one can be employed independently of the node architecture.

Table 10.

Number of components and port count for the different node architectures.

The analysis of Table 10 shows that each directly switched core pair saves two ports on the M × M WSS and a number of optical amplifiers corresponding to the number of bands per core (B). It is important to note that it is assumed that all bands of a core pair are directly switched, and it is not possible to directly switch only some of the transmission bands from a core. The equations in Table 10 provide a method to calculate the number of optical amplifiers, WSSs, and S-OXCs needed for a network node defined by B, C, and D. These component counts can then be converted into the node’s CAPEX by summing the costs of the required optical amplifiers, WSSs, and S-OXCs. The cost of band filters is considered negligible, and fiber and add-drop structure costs are excluded since they are assumed to be identical across all node architectures.

The cost of the optical amplifiers is taken from the cost model for dual-stage amplifiers; however, the cost of WSSs and S-OXCs is not available and should therefore be estimated using a similar strategy as the one used in the cost model. The cost increment is assumed to be 10% for the L-band amplifier and 25% for the S-band.

To estimate the cost of the M × M WSS, it is assumed that it is implemented by a concatenation of WSS in a route and select structure [27]. With this assumption, the number of required WSSs to construct an M × M WSS is given by if (additional WSSs are not required for the add and drop ports because they are taken directly from the ports of the WSSs as shown in Figure 5b). This work does not consider the case of .

The costs and power consumption values of a 1 × 12 and a 1 × 32 WSS and of 16 × 16 and 32 × 32 S-OXCs are estimated using the following framework. The costs are c.u. for the 1 × 12 and the 1 × 32 WSSs and the 16 × 16 and the 32 × 32 S-OXCs, respectively. The S-OXC cost values are taken from the same public website as the cost model [13] and using the same strategy (European cost value excluding VAT). Even though there is only a single example of each device, the values are consistent with expert partner consultations. The WSS values are hard to find in public databases and are therefore based solely on expert knowledge from the partners for these two specific WSS configurations. For the architecture using MB devices (MBS-OXC), we assume that a three-band multiband WSS costs 95% of three single-band WSSs and that the integrated amplifiers and band filters device for amplification of three bands cost 95% of three single-band amplifiers.

The evolution of the CAPEX of a network node for an increasing number of directly switched core pairs is evaluated. The evaluation considers a transmission system with three bands per core B (S, C, and L) and a node with four degrees D, three parallel single-core fibers per degree (leading to ), resulting in a total of 12 input/output core pairs. Furthermore, the node configuration includes four WSS add/drop ports ().

Figure 5c shows the CAPEX evolution for the different proposed node architectures and the reference node as a function of . The cost of the reference node remains at 225 c.u. because it does not offer the possibility of core/fiber switching. When , the cost of architecture SB is the same as the reference node because they have the same number of devices. The other two proposed node architectures have the additional cost of the S-OXCs, but the reduced cost of the integrated multiband devices makes the total cost of the MBS-OXC architecture similar to the reference and SB node architectures. On the other hand, when all fiber pairs are directly connected (), the cost of the proposed architectures is reduced to half of the initial number of amplifiers plus the S-OXCs, given that no WSS is needed. The sharper reduction of the cost of the proposed architectures from to and from to is caused by the reduction of the number of ports of the WSS (from 1 × 32 to 1 × 12) and the S-OXC (from 32 × 32 to 16 × 16), respectively. Furthermore, the costs associated with the MBS-OXC and SB architectures are comparable. This similarity is a consequence of the cost reductions assumed for integrated multiband devices. In the absence of such integration-related savings, the cost of the MBS-OXC architecture would exceed that of the SB architecture by the cost of the S-OXC. Consequently, greater estimated cost reductions narrow this gap.

3.2. Comparison of Different Transport Solutions in the RAN

The second example of the application of the proposed cost model is the comparison of different transport solutions to carry the fronthaul (FH) flows in the RAN between the radio unit (RU) located at a mobile site and the distributed unit (DU) function located in the central office (CO).

The relevance of this case study with optical networks is due to the fact that it compares solutions that imply the use of different technologies and architectures for the transport of traffic generated by radio systems, which, within the same scenario (i.e., geotype) and time period, constitute an invariant in the problem setting.

The analysis has been made in different conditions of macro and small cell deployments (four geotype configurations reflecting areas with different population densities and socio-economic contexts) and in two different time frames—medium and long term (MT and LT, respectively)—each of them with specific configurations and requirements of radio layers at mobile sites. The assumption is that four operators share the same mobile site to install their radio units, and a single transport service from the mobile site to the CO is shared by the four operators to carry their FH flows as well. The scenario setting is described in detail in [28]. Here, we provide a summary description.

Regarding the scenarios, we can summarize the main features of the four geotypes considered in the study: urban (UR), dense urban (DU), suburban (SU), and rural (RU). The DU geotype covers an area of 0.64 km2, has a population of 10,000 people, and has 5 mobile sites with both macro and small cells and 20 sites with only small cells. The UR geotype covers an area of 2.56 km2, has a population of 17,500, and has 9 sites with both macro and small cell types and 16 with only small cells. The SU geotype covers 3.61 km2, has a population of 13,750 people, and has 9 sites with both macro and small cell types and 8 with only small cells. Finally, the RU geotype has a coverage of 163.84 km2, has a population of 5500 people, and has 5 sites with macro cells plus 4 with only small cells. The model also assumes that the radio mobile sites are uniformly distributed within each geotype according to a uniform grid drawn on a square-shaped area. More details about geotype characterization can be found in [28].

In Table 11, the radio carrier parameters applied in the study are specified. The table shows for both categories of cells (macro and small), an identifier for the combination of cell type and band range (cell type; BR id.), the band range, the number of bands (N.Bands) within the band range, the carrier width (C.W.) in MHz, the multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) layers, and the resulting FH data rate in Gb/s (FH Gb/s).

Table 11.

Assumptions on radio carrier parameters in each band range for macro and small cells.

In Table 12, the number of carriers for each geotype and for the two timeframes (MT and LT) is provided. For each carrier, three cells are considered in macro cell sites, while in small cell sites, there is only one cell per site. The data rate transportation need of a macro cell site or a small cell site is obtained by combining the FH data rates of Table 11, the number of carriers in each radio site as in Table 12, and the number of cells per carrier. Please note that FH streams originate from each individual RU and, as such, can be transported separately or aggregated, depending on the solution chosen for transport between the site and the central office.

Table 12.

Number of site carriers for different geotypes in the two timeframes.

The FH signal transport problem consists of carrying the streams from each RU to the distributed unit (virtual, vDU, or physical, like a conventional baseband unit) located at the CO. The size of the stream depends on the channel width and the number of MIMO layers, depending in turn on the type of RU, and it ranges from a few hundred Mb/s to tens of Gb/s per single RU, as can be seen in the fourth column of Table 11, where the values of data rates are given for the Split 7.2 option [29] for the urban geotype setting and for eight MIMO layers. These flows can be transported separately or aggregated; in the latter case, all or a subset of them can be aggregated.

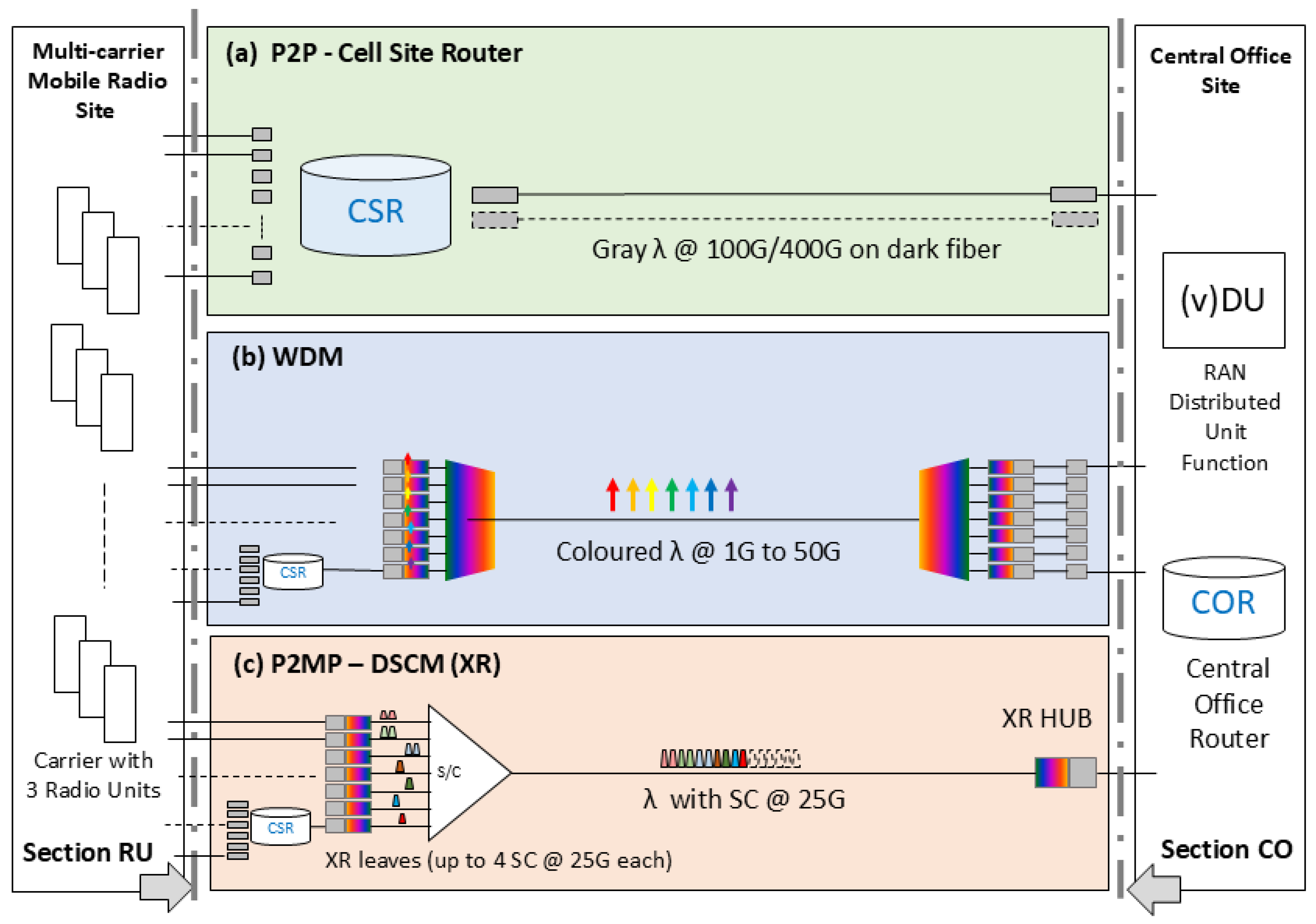

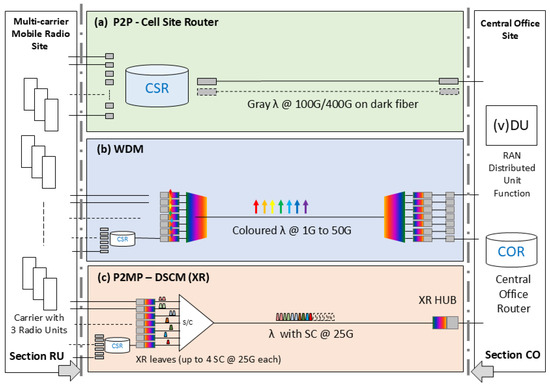

Figure 6 presents three alternative solutions for FH traffic transportation. The first option (inset (a), P2P—Cell Site Router) uses a Layer 3 aggregator switch for all FH flows coming from the RUs and exchanges the traffic with the CO through circuits made with gray transponders and fibers. A dedicated pair of fibers (one for each direction of monodirectional transmission) is used for each circuit. Depending on the traffic collected and the data rate of the gray transceivers used, one or more circuits could be required.

Figure 6.

Alternative solutions for FH traffic transportation. FH is carried between the RU (mobile site) section and the CO section by (a) P2P transceivers on dark fiber, (b) a WDM line system, or (c) P2MP-DSCM transceivers (Cell Site Router can be used to aggregate all, as in (a), or part, as in (b,c), of FH flows).

The second option considered uses a WDM system (typically CWDM, inset (b) WDM) to optically multiplex the signals from the RUs onto a single-line system and carry the traffic to the CO. This system proves adequate when the data rate of the FH flows makes good use of the WDM system; this happens when the single flows are in the order of one Gb/s or higher, but it is inefficient for the transport of lower bit rate flows. To overcome this drawback, it is possible to insert a low-capacity aggregator router that aggregates the low-bit-rate flows into a single circuit at 1 Gb/s or higher to be transported over the WDM system.

Finally, the third option considered (inset (c), P2MP DSCM) uses coherent transceivers that implement digital subcarrier multiplexing and that allow for point-to-multipoint networking with a hub at the CO and leaves at the radio base station. Since the granularity of DSCM flows is 25 Gb/s, packet multiplexing of low-bit-rate FH signals is necessary, while high-bit-rate FH flows (>10 Gb/s) can be efficiently transported by a single subcarrier or by two subcarriers if the data rate is greater than 25 Gb/s (according to the hypothesis, there are no FH flows from a single RU exceeding 50 Gb/s). This is the reason for the presence of the multiplexing router at the radio base station.

We can summarize that, in the first case, we have a solution based on full-packet multiplexing and gray optics; in the second, we have analog optical multiplexing (WDM); and in the third, we have optical digital subcarrier multiplexing. In the second and third options, however, partial-packet multiplexing of low data rate FH flows becomes necessary to optimize the utilization of optical signals.

In all three options presented above, the application is considered static, meaning that the connections (and associated wavelengths) between the radio site and the central office must be permanently active and available. Indeed, it is always necessary to ensure site connectivity (dynamic connectivity is not envisaged), and the data rate to be guaranteed for individual FH flows is the peak rate required by the RUs. Regarding fiber utilization (used optical bandwidth divided by available optical bandwidth), it is low in all cases given the nature of the problem; in fact, the access network is specifically designed to collect traffic from mobile radio sites and only from them, and fiber is a commodity that is assumed to be available and invariant between different cases (a pair of fibers is sufficient to transport the traffic exchanged by each radio base station). In this sense, fiber utilization and the capacity utilization of individual wavelengths (used data rate divided by available data rate of the wavelength) are not variables of interest for the problem. However, optimization is performed in the use of wavelength capacity by choosing a wavelength with the most appropriate data rate, i.e., the lowest possible in relation to the traffic to be transported. A possible fiber sharing could be achieved with the passive optical network (PON) systems of the fixed access network, but this option is not considered in this work, and in any case, it would not change the techno-economic analysis of transport solutions for the radio access.

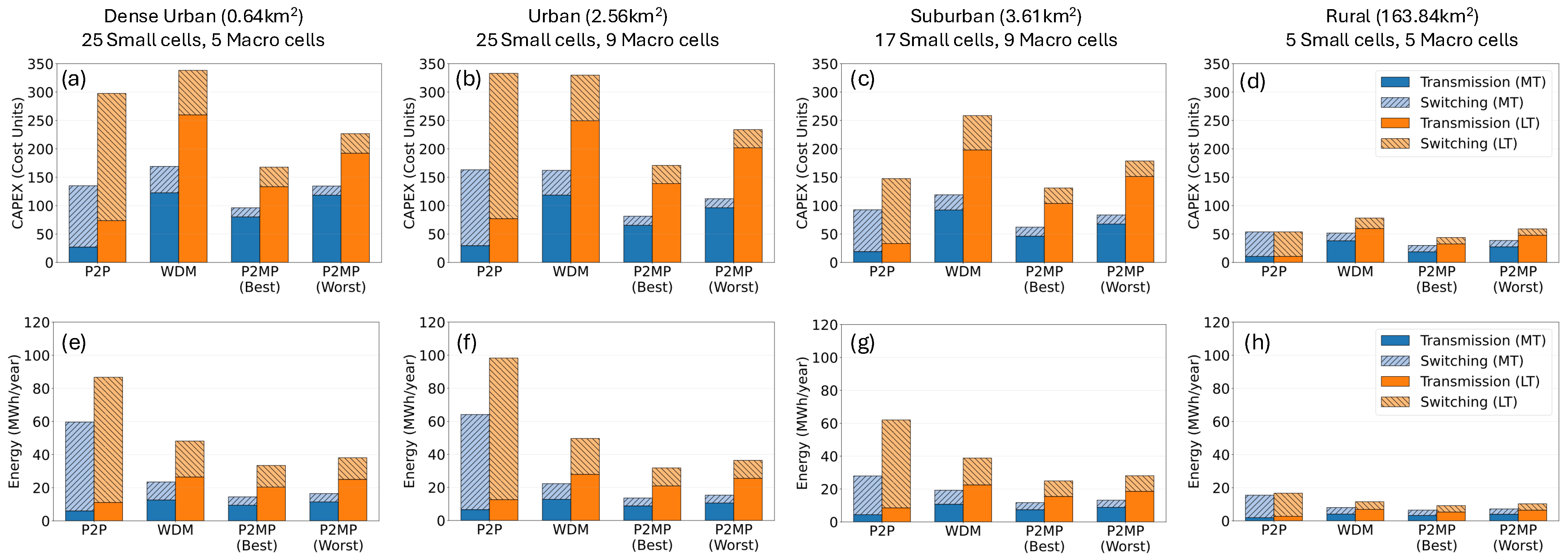

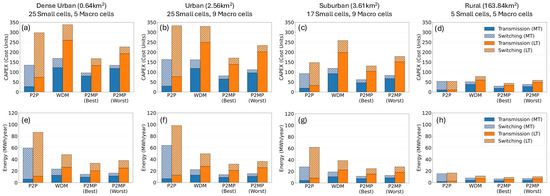

In accordance with the hypotheses presented, the results shown in Figure 7 were obtained. These results update those reported in [30,31] as they apply the cost values presented in this document, which were not previously available. The costs used for the economic evaluation are those reported in Table 3 for the gray transceivers, Table 4 for the WDM transponder, Table 5 for the DSCM coherent transceivers, and Table 7 for the router. A factor is applied in the latter case, as a router is expected to cost four times that of a Layer 3 switch of the same capacity. The WDM multiplexer in case (b) was assigned the cost of 0.24 c.u. For the DSCM modules, the best- and worst-case scenarios were evaluated using the minimum and maximum cost values from the ranges provided in Table 5.

Figure 7.

Comparison of CAPEX (top strip, (a–d)) and energy consumption (bottom strip, (e–h)) for the three transport solutions examined in the four geotypes considered.

The results were obtained with a custom Python-based (v3.13) techno-economic tool [32]. The algorithm’s logic involves, first, sizing the optical systems based on the fronthaul bandwidth requirements of the mobile sites, taking into account their radio layer configuration and combining radio parameters (Table 11) and site configuration data (Table 12), performed separately for each of the four geotypes and for each of the two time horizons considered. A heuristic criterion is applied to optimize the use of fiber in the geotype area; however, it is not included in the economic calculation (it is assumed that there is a sufficient quantity of fiber, as is typical for an incumbent operator; furthermore, at least within certain limits, the cost of the fiber used is invariant across the different solutions analyzed). The final step calculates CAPEX and energy consumption for each geotype and separately for the medium and long term. This is performed by applying the cost and energy model presented in Section 2 to the equipment bill of materials obtained in the dimensioning step.

The results presented in Figure 7 demonstrate the techno-economic performance of the three transport solutions across different deployment scenarios. The analysis reveals several key insights regarding both CAPEX and energy consumption patterns across the four geotypes considered.

The P2P solution consistently exhibits the highest CAPEX across all geotypes, particularly in dense deployments, where it reaches approximately 330 c.u. in the dense urban scenario. This increased cost stems primarily from the requirement for dedicated fiber pairs, which translates into multiple gray transceivers for each fronthaul link and multiple switching devices. The WDM solution offers substantial CAPEX savings compared to P2P, with reductions ranging from 40% to 50% across different geotypes. This efficiency results from the optical multiplexing capability that reduces the number of required fibers and leverages economies of scale in the optical transport layer.

The P2MP DSCM solution demonstrates the most attractive CAPEX profile, especially when considering the best-case scenario with lower cost assumptions for DSCM transceivers. In this configuration, CAPEX reductions of up to 60% compared to P2P are achieved in dense urban scenarios. Even in the worst case with higher DSCM transceiver costs, the P2MP solution remains competitive with WDM across most deployment scenarios. The rural geotype shows the smallest absolute differences between solutions, reflecting the lower traffic aggregation requirements and reduced complexity in sparse deployments.

Energy consumption patterns largely follow the CAPEX trends, with P2P solutions requiring the highest power consumption due to the larger number of active transceivers and Layer 3 switching equipment. Dense urban deployments show P2P energy consumption reaching approximately 85 MWh/year. WDM solutions achieve energy savings of 30–40% compared to P2P across all geotypes, primarily through the elimination of multiple gray transceivers and the efficient optical multiplexing approach. The P2MP DSCM solution demonstrates the most favorable energy profile, with consumption reductions of up to 50% in the best-case scenario. This efficiency results from the point-to-multipoint architecture that reduces the overall number of active optical components and eliminates the need for multiple P2P connections.

The comparison between MT and LT scenarios reveals the impact of evolving radio requirements. The LT scenarios generally show higher absolute costs and energy consumption due to increased capacity requirements from additional radio carriers and higher MIMO configurations. However, the relative performance rankings between transport solutions remain consistent across time frames. Dense urban environments show the largest absolute differences between solutions, making solution selection most critical from both CAPEX and OPEX perspectives, while rural deployments show minimal differences between solutions, suggesting that solution selection may be driven by factors other than pure cost optimization.

Overall, these results indicate that P2MP DSCM solutions offer the most promising techno-economic performance, particularly in high-density deployments where the benefits of P2MP architecture and digital subcarrier multiplexing are most pronounced.

4. Conclusions

This work introduces a generalized cost model designed to support TEA in optical networks. Unlike prior models that are often restricted to specific domains or technologies, the proposed framework harmonizes cost assumptions, integrates data from publicly available sources and expert knowledge, and incorporates methods for extrapolating costs of emerging equipment. The model provides updated cost and power consumption estimates for a broad range of commercially available optical components, including transceivers, amplifiers, switches, routers, and compute/storage systems, while also addressing the challenges of uncertainty, scalability, and regional variability. It also provides two frameworks for estimating the cost and power consumption of non-commercial or future equipment that requires the development of current or new technologies. The cost data processed and published in this article have also been made publicly available, as reported below in the Data Availability Statement. The file including cost values is considered to be a temporary version that will be updated with data from new devices or classes of devices as they are introduced in future work.

Two case studies demonstrated their practical relevance: (i) an assessment of cost savings achievable through MBoSDM node architectures and (ii) a comparative analysis of different transport solutions for fronthaul traffic in radio access networks. The results showed that modular and flexible architectures, as well as digital subcarrier multiplexing, offer significant reductions in both CAPEX and energy consumption, particularly in dense deployment scenarios. For the second case study, the Python code developed to model the problem and obtain the results has been made openly available [32].

Overall, the proposed cost model provides a foundation for establishing a consistent methodology for TEA in optical networking. It serves not only as a reference tool within the SEASON project but also as a general framework that can be reused and extended by the wider research community.

Moreover, the model’s assumptions and frameworks were developed in close collaboration with industrial partners, which ensures alignment with practical requirements. Consequently, it can be used beyond academic research, particularly by operators who need to perform architectural evaluations for the networks they need to deploy by comparing alternatives in the absence or scarcity of known cost values. This happens, for example, when the equipment and devices (elements) are not yet in their commercial phase but only in the prototype phase or in the development roadmap. This can also be the case when a rough preliminary and quick TEA is needed, and even though the elements are available on the market, the request-for-quotation process for the equipment and devices is avoided, which is always a time-consuming and resource-intensive step. Again, when a comparison between a legacy solution (with elements with known costs) and an innovative solution (with elements whose costs are only predictable with uncertainty) is required, the methodology and the dataset model provided by this work can be of great help.

Future work will enhance the model by integrating additional device categories, improving the representation of uncertainty, and factoring in other operational expenditures. These advancements aim to establish a more comprehensive foundation for techno-economic assessments of next-generation optical networks. Furthermore, the data gathered for the model could be leveraged to develop an AI-driven tool capable of quickly and accurately estimating the cost of optical network systems based on user-defined parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Q., J.M.R.-M., G.G., L.N., M.R., and J.P.; methodology, A.S., M.Q., M.M.H., and J.P.; software, A.S., M.M.H., A.M., and C.C.; validation, A.S., M.Q., F.A., A.V.P., J.M.R.-M., G.G., L.N., and S.P.; formal analysis, A.S., M.Q., A.M., C.C., and F.A.; investigation, A.S., M.Q., A.V.P., J.M.R.-M., and L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., M.Q., M.M.H., and A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.S., M.M.H., C.C., F.A., A.V.P., J.M.R.-M., G.G., L.N., M.R., S.P., and J.P.; visualization, A.S., M.M.H., and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the SNS Joint Undertaken—European Union’s Horizon RIA research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 101096120 (SEASON).

Data Availability Statement

The cost model values are provided as a spreadsheet at https://zenodo.org/records/17304012 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

André Souza, Mohammad M. Hosseini, and João Pedro were employed by Nokia. Marco Quagliotti was employed by Telecom Italia (TIM). Arantxa Villavicencio Paz was employed by Adtran. José Manuel Rivas-Moscoso was employed by Telefónica. Gianluca Gambari was employed by Ericsson. Stephen Parker was employed by Acceleran. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| c.u. | Cost Unit |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| CO | Central Office |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| CWDM | Coarse WDM |

| DC | Data center |

| DPU | Data Processing Unit |

| DSCM | Digital Subcarrier Multiplexing |

| DU | Distributed Unit |

| DWDM | Dense WDM |

| EDFA | Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers |

| FH | Fronthaul |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| LAN | Local Area Network |

| LT | Long Term |

| MB | Multiband |

| MBoSDM | MB over SDM |

| MIMO | Multiple-input Multiple-output |

| MSA | Multi Source Agreement |

| MT | Medium Term |

| NIC | Network Interface Card |

| NLS | Nonlinear Least Squares |

| NRZ | Non-return-to-zero |

| OPEX | Operational Expenditures |

| P2MP | Point-to-multipoint |

| P2P | Point-to-point |

| PAM4 | Pulse Amplitude Modulation with 4 levels |

| QSFP-DD | Quad SFP- Double Density |

| RAN | Radio Access Network |

| ROADM | Reconfigurable Optical Add-Drop Multiplexer |

| RU | Radio Unit |

| SC | Subcarrier |

| SDM | Space Division Multiplexing |

| SFP | Small Form-factor Pluggable |

| S-OXC | Spatial Optical Cross-connects |

| SW | Software |

| TEA | Techno-economic Analysis |

| TOR | Top-of-Rack |

| UPF | User Plane Function |

| VAT | Value-added Tax |

| vCU | Virtual Centralized Unit |

| vDU | Virtual Distributed Unit |

| WAN | Wide Area Network |

| WDM | Wavelength Division Multiplexing |

| WSS | Wavelength Selective Switch |

References

- Burk, C. Techno-economic analysis for new technology development. Adv. Mater. 2017, 1, 266–269. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, S.Y.W.; Phang, F.J.F.; Yeo, L.S.; Ngu, L.H.; How, B.S. Future era of techno-economic analysis: Insights from review. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 924047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capital, F. Cost Modeling Challenges: How to Overcome the Common Difficulties and Problems of Cost Modeling. Available online: https://fastercapital.com/content/Cost-Modeling-Challenges--How-to-Overcome-the-Common-Difficulties-and-Problems-of-Cost-Modeling.html (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Scalable, Tunable and Resilient Optical Networks Guaranteeing Extremely-High Speed Transport (STRONGEST) Project Website. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/247674/reporting/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Industry-Driven Elastic and Adaptive Lambda Infrastructure for Service and Transport Networks (IDEALIST) Project Website. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/317999/reporting/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- METRO High Bandwidth, 5G Application-Aware Optical Network, with Edge Storage, Compute and Low Latency (Metro-Haul) Project Website. Available online: https://metro-haul.eu/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Hernandez, J.A.; Quagliotti, M.; Serra, L.; Luque, L.; Lopez da Silva, R.; Rafel, A.; Gonzalez de Dios, O.; Lopez, V.; Eira, A.; Casellas, R.; et al. Comprehensive model for technoeconomic studies of next-generation central offices for metro networks. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2020, 12, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyond 5G—OPtical nEtwork coNtinuum (B5G-OPEN) Project Website. Available online: https://www.b5g-open.eu/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Jana, R.K.; Srivastava, A.; Lord, A.; Mitra, A. Optical cable deployment versus fiber leasing: An operator’s perspective on CapEx savings for capacity upgrade in an elastic optical core network. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2023, 15, C179–C191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Correia, B.; Napoli, A.; Curri, V.; Costa, N.; Pedro, J.; Pires, J. Cost analysis of ultrawideband transmission in optical networks. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2024, 16, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpanaei, F.; Rivas-Moscoso, J.M.; Francesca, I.D.; Hernández, J.A.; Sánchez-Macián, A.; Zefreh, M.R.; Larrabeiti, D.; Fernández-Palacios, J.P. Enabling seamless migration of optical metro-urban networks to the multi-band: Unveiling a cutting-edge 6D planning tool for the 6G era. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2024, 16, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEASON: Seasonal Energy Storage and Optimization Network. 2025. Available online: https://www.season-project.org (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- FS. Available online: https://www.fs.com/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Approved Networks. Available online: https://www.approvednetworks.com/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Dell Technologies. Available online: https://www.dell.com/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Welch, D.; Napoli, A.; Bäck, J.; Sande, W.; Pedro, J.; Masoud, F.; Fludger, C.; Duthel, T.; Sun, H.; Hand, S.J.; et al. Point-to-Multipoint Optical Networks Using Coherent Digital Subcarriers. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 5232–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, D.; Napoli, A.; Bäck, J.; Buggaveeti, S.; Castro, C.; Chase, A.; Chen, X.; Dominic, V.; Duthel, T.; Eriksson, T.A.; et al. Digital Subcarrier Multiplexing: Enabling Software-Configurable Optical Networks. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open XR Optics Forum. Available online: https://www.openxropticsforum.org/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Farmer, J.D.; Lafond, F. How predictable is technological progress? Res. Policy 2016, 45, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Simplification Agenda for European Telecoms. Available online: https://www.telefonica.com/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2025/07/A-Simplification-Agenda-for-European-telecoms-2025-ADL-for-Connect-Europe.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hosseini, M.M.; Pedro, J.; Napoli, A.; Costa, N.; Prilepsky, J.E.; Turitsyn, S.K. Optimization of survivable filterless optical networks exploiting digital subcarrier multiplexing. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2022, 14, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, L.; Eiselt, M. Optical Amplifiers for Multi–Band Optical Transmission Systems. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Napoli, A.; Fischer, J.K.; Costa, N.; D’Amico, A.; Pedro, J.; Forysiak, W.; Pincemin, E.; Lord, A.; Stavdas, A.; et al. Assessment on the Achievable Throughput of Multi-Band ITU-T G.652.D Fiber Transmission Systems. J. Light. Technol. 2020, 38, 4279–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, L. Challenges for Multiband Optical Amplification and Solutions Therefore. J. Light. Technol. 2024, 42, 4202–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, M.; Nasr, M.; Seleem, H. Thulium doped fiber amplifier in the S/S/sup +/ band employing different concentration profiles. In 2005 Fifth Workshop on Photonics and Its Applications, Giza, Egypt, 10 May 2005; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Costa, N.; Nadal, L.; Casellas, R.; Melgar, A.; Rivas-Moscoso, J.M.; Quagliotti, M.; Riccardi, E.; Napoli, A.; Pedro, J. Node Architectures for High-Capacity Multi-band Over Space Division Multiplexed (MBoSDM) Optical Networks. In 2024 24th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Bari, Italy, 14–18 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahara, A.; Kawahara, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Kawai, S.; Fukutoku, M.; Mizuno, T.; Miyamoto, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Yamaguchi, K. Proposal and experimental demonstration of SDM node enabling path assignment to arbitrary wavelengths, cores, and directions. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 4061–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEASON Project Deliverable D2.1, Definition of Use Cases, Requirements and Reference Network Architecture. Available online: https://www.season-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/Deliverables/Deliverable-2-1_SEASON_V2.1.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- O-RAN ALLIANCE Specification O-RAN.WG9.XTRP-REQ-v01.00, O-RAN Open Xhaul Transport Working Group 9, Xhaul Transport Requirements, Feb. 2021. Available online: https://orandownloadsweb.azurewebsites.net/specifications/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- SEASON Project Deliverable D2.2, Techno-Economic Analysis: First Results. Available online: https://www.season-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/Deliverables/D2.2%20%20Techno-economic%20Analysis%20-%20First%20Results.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Marotta, A.; Centofanti, C.; Graziosi, F.; Quagliotti, M.; Agus, M. Coherent Point-to-Multipoint as a Viable Techno-Economic Solution for Mobile Network Fronthaul. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Optical Network Design and Modeling (ONDM), Pisa, Italy, 6–9 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Marotta, A.; Centofanti, C.; Quagliotti, M.; Agus, M. SeasonTechnoEconomic: A Techno-Economic Analysis Tool for Optical Transport Solutions in Next Generation RAN (GitHub Repository). 2025. Available online: https://github.com/andreamarotta/SeasonTechnoEconomic (accessed on 11 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.