Abstract

Photobiomodulation causes an immediate increase in local blood flow. This study aimed to investigate the effect of 890 nm NIR exposure on local skin blood flow in young and middle-aged healthy subjects. In this placebo-controlled clinical trial, 12 young and 12 middle-aged subjects received either continuous or intermittent NIR exposure (890 nm, 5.1 mW/cm2, 4.6 J/cm2, and 35.9 J total energy) on the skin of the upper lateral arm. The continuous exposure experiment, performed in young subjects only, applied 30 min of continuous NIR light. The intermittent exposure experiment, conducted in both age groups, applied NIR light through 10 cycles of 3 min NIR exposure and 2 min OFF (for recording blood flow), resulting in a total duration of 50 min. Laser Doppler flowmetry and thermal images were used to monitor local blood flow and skin temperature. In young subjects, continuous NIR exposure significantly increased blood flow for the first 20 min post-exposure compared to placebo. Further, in young and middle-aged subjects, intermittent exposure increased blood flow during the whole exposure period and 15 min post-exposure. In young subjects, blood flow after continuous NIR exposure was significantly higher than intermittent NIR exposure only for the first 10 min. Comparing intermittent exposure between the two age groups, the blood flow was significantly higher in middle-aged subjects. We conclude that NIR PBM increases local skin blood flow in young and middle-aged subjects. The mode of NIR irradiation and the subjects’ age influenced the local skin blood flow response.

1. Introduction

Photobiomodulation (PBM) or Low-Level Light Therapy (LLLT) is the use of low intensity red and near-infrared light (R/NIR) (wavelengths of 600–1100 nm) to modulate biological activity in response to the energy delivered by the photons of light and not due to heat [1,2]. PBM has demonstrated a wide range of therapeutic effects in both preclinical and clinical settings, including tissue repair, neuronal regeneration, treatment of stroke and traumatic brain injury, and improvement of neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases [1,2,3,4]. It has also been shown to promote wound healing, reduce inflammation, and provide analgesia in rheumatic and orthopedic disorders [5,6,7,8]. However, the exact mechanisms, optimal light parameters, and dosages to achieve these biological responses remain largely unknown. The parameters of the light source and the doses of light used in PBM are key determinants of cellular and tissue responses after treatment with NIR light. However, a generally accepted mechanism is that R/NIR light modulates cellular activity due to increased mitochondrial oxidative metabolism [3,7,9]. The mitochondrial chromophores (photo-acceptors) in the respiratory chain absorb light photons, mainly cytochrome c oxidase (CCO). The absorption increases the mitochondrial membrane potential, followed by increased metabolism and ATP synthesis, activation of different signaling pathways, and changes in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) concentration [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. However, optimal dosing appears to be critical, as NIR exposure that is either too high or too low (defined in terms of fluence, irradiance, delivery duration, or repetition frequency) may result in a lack of significant effects or, in some cases, even inhibitory responses [16,17,18].

NO is a potent endogenous vasodilator, and R/NIR light exposure is reported to cause vasodilatory effects by photo-dissociating NO from CCO, the NO stores in endothelial cells in blood vessels, and the hemoglobin in circulating erythrocytes [11,12,13,14]. Red and NIR light increases vasodilation in healthy and diabetic mice by releasing NO-bound substances (S-nitrosothiols or non-heme iron nitrosyl complexes) from the vascular endothelium [19,20,21]. These effects were reversed after adding a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor or removing endothelial cells from the arteries [19]. R/NIR light has also been shown to protect cardiomyocytes from hypoxia and reoxygenation damage by a NO-dependent mechanism [22]. Local PBM therapy has also been shown to enhance NO content and improve circulation in an experimental model of burned rat skin [23]. Different light wavelengths stimulate the expression of inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) differently [24,25].

In clinical studies, increased skin blood flow has been observed after NIR PBM in healthy and diabetic subjects [26,27,28,29,30]. However, the response varies, possibly due to (1) the physical parameters of the light administered, such as the power density and mode of irradiation, wavelength, fluence, size of the irradiated area, and depth of the targeted tissue; (2) the type of tissues as cells with higher numbers of mitochondria theoretically would exhibit a more significant response [31]. The varying response may also depend on all other endogenous factors that influence the skin micro-circulation [32,33] or the differing light parameters and dosages used in different studies [26,27,28,29,30]. Potential sex-related differences in skin blood flow response to PBM may be attributed to hormonal variations, vascular reactivity, and other physiological factors that can vary between males and females [34]. The direct thermal effect of exposing the skin to the device delivering the R/NIR light might also be involved.

Although studies investigating skin microcirculation have used both R and NIR light [26,27,29,30], we chose to use NIR light with wavelength 890 nm. Using a layered skin model and the measured wavelength-dependent absorption and reduced scattering coefficient for each layer, the wavelength-dependent optical penetration depth has been estimated using Monte Carlo simulations [35,36], or simple analytical model for a single layer skin model [37]. There is a great variability in the geometry and content of skin between and within individuals, which limits the value of comparison between studies. Finlayson et al. [36] report a penetration depth (fluence rate reduced to 10% of incident light) of approximately 3.5 mm for 890 nm, while Bashkatov et al. [37] report a penetration depth (fluence rate reduced to 37% of incident light) of approximately 2.5 mm at the same wavelength. The penetration depth of NIR light in tissue is influenced by multiple factors, such as the wavelength of the NIR light, the energy of the radiation, the attenuation coefficient (scatter, refraction, and absorption), the area of irradiance, the coherence of the light, and the pulsing characteristics [38,39]. The literature on the effect of NIR light on human skin micro-circulation is limited. Studies have reported increased skin micro-circulation [29,30] or no increase in blood flow following NIR light exposure in humans [40]. To the best of our knowledge, no placebo-controlled studies on the effect of the mode of irradiation and the subject’s age on local skin blood flow in humans have been reported.

Considering the limited literature and conflicting reports, we performed a series of pilot experiments within our research group. The study protocol was developed based on a combination of prior published work and internal pilot experiments conducted to optimize experimental parameters. The present study aimed to evaluate the immediate effect of NIR (890 nm) light exposure on local skin blood flow using continuous NIR light exposure in young subjects and intermittent NIR light exposure in both young and middle-aged subjects to investigate the effect of different irradiation modes on skin blood flow response and heat deposition in the skin. In addition, intermittent NIR light exposure was also used to study the possible effect of age on local skin blood flow between young and middle-aged subjects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Participants

Twenty-four healthy Caucasian subjects aged 18 to 60 were enrolled in a single-blinded, placebo-controlled study between May and August. Participants were assigned to two age groups, 12 young adults (Group 1, age 25 (21–31)) and 12 middle-aged adults (Group 2, age 51 (41–58)). Participants served as their own controls, with placebo and intervention procedures performed on the same subject at the same skin site on the same day. The young subject group participated in two experiments on two different days (continuous (experiment 1) and intermittent (experiment 2) NIR light exposure), while it was a single-day study for the middle-aged group (intermittent NIR exposure (experiment 3)). Experiments 1 and 2 were conducted between the months of May and July, and Experiment 3 was conducted between July and August. Apart from the three main experiments, where NIR light exposure and placebo interventions were performed on the same day, participants from each group (subject to availability) were invited to participate in control experiments. In the young group, all 12 participants attended the control session: 5 for intermittent control and 7 for continuous control. In the middle-aged group, 6 participants attended the intermittent control session. Inclusion criteria were: (1) 18–65 years old, and (2) generally healthy subjects with no reported illness in the last three months. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Major unstable chronic diseases, (2) chronic skin conditions, (3) pregnancy, and (4) participants deemed ineligible to participate for any reason after evaluation by the study physician (SCC). Throughout the experiments, the study physician was available by cell phone to address medical concerns or emergencies.

2.2. Experimental Equipment

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) from the Therapy System (Model 120, Anodyne Therapy Professional System, Tampa, FL, USA) were used to develop a modified version of the Anodyne device (Figure 1). This modified system reduced the number of LEDs from 60 per pad to 20, resulting in an illuminated area of 23 × 34 mm2. The Anodyne device was modified to create a 19 mm distance between the LEDs and the skin to reduce the transport of conductive heat to the skin. A Laser Doppler blood Flowmeter (LDF) with a miniature standard surface probe was used to measure local skin blood flow (AD Instruments, Oxford, UK) (Figure 1). The probe emits light (830 ± 10 nm, power < 0.5 mW) through an optic fiber, and the light illuminates the skin and finally gets reflected by moving and static structures. A second optic fiber in the same probe registers this reflected light. This output signal is recorded as blood perfusion units (BPU). BPU is an arbitrary unit that only represents the perfusion of blood cells (numbers and speed) in the targeted skin (illuminated) area. The LDF utilizes the Doppler shift in the reflected light caused by the moving blood cells to register the BPU/skin blood flow. For cutaneous measurements, the LDF measurement depth volume is estimated to be approximately 1.0 to 1.5 mm2, leading to a sample volume of approximately 1 mm3 [41]. To measure local skin temperature, a thermal camera with a spatial resolution of 128 × 96 pixels and a thermal sensitivity of <70 mK was used (FLIR, C3-X series, FLIR Systems Inc., Wilsonville, OR, USA).

Figure 1.

Laser Doppler Flowmeter standard probe (a), modified Anodyne (note that LEDs will not touch the skin) (b), intervention site upper lateral arm (c), and experimental setup (d).

2.3. Interventions and Experimental Procedure

Participants were instructed to avoid smoking, exercise, a hot bath or shower, workouts, excessive caffeine consumption the last 3–4 h before the study session, and any other activities that might influence the skin blood flow. The experiment room was quiet and comfortable, with a steady temperature of 24 ± 2 °C. Participants sat in a comfortable recliner chair for 15–20 min before starting the intervention to normalize breathing, relax, and acclimate to the environment. Movements were limited for the experiment period to minimize motion artifact noise because that could cause an overestimation of the LDF (BPU) readings. The LDF probe was attached to the skin of the left upper lateral arm with self-adhesive tape. For all interventions, the intervention site was localized approximately 15 cm below the acromion process on the left lateral arm. The upper arm was selected for its relatively uniform skin and subcutaneous tissue thickness [42] and ease of stabilization, enabling reliable skin blood flow measurements with minimal motion artifacts. The placebo (sham procedure with the LED equipment turned off) and the intervention (NIR light exposure) were performed at the same skin site on the left upper lateral arm. Placebo procedures were performed before the active intervention period to avoid any lingering effects from active NIR exposure. The placebo procedure closely replicated the active NIR light exposure protocol in timing, duration, and setup, except for the absence of actual NIR light stimulation. There was a time gap between the placebo and active intervention to prevent any potential effects stemming from the temporary removal and reattachment of the experiment equipment. The exposed skin area was marked for young subjects to ensure the two study sessions were performed at the same skin site.

For the control procedures, the same modified Anodyne device used in the main experiments was covered with aluminum foil to block the NIR light while allowing heat conduction from the LEDs. Control experiments were performed at the same skin site on the left upper lateral arm but on a different day. These control procedures replicate the timing and duration of the placebo and active NIR exposure protocols, maintaining a similar experimental setup. The control setup allowed thermal conduction from the device without NIR light exposure.

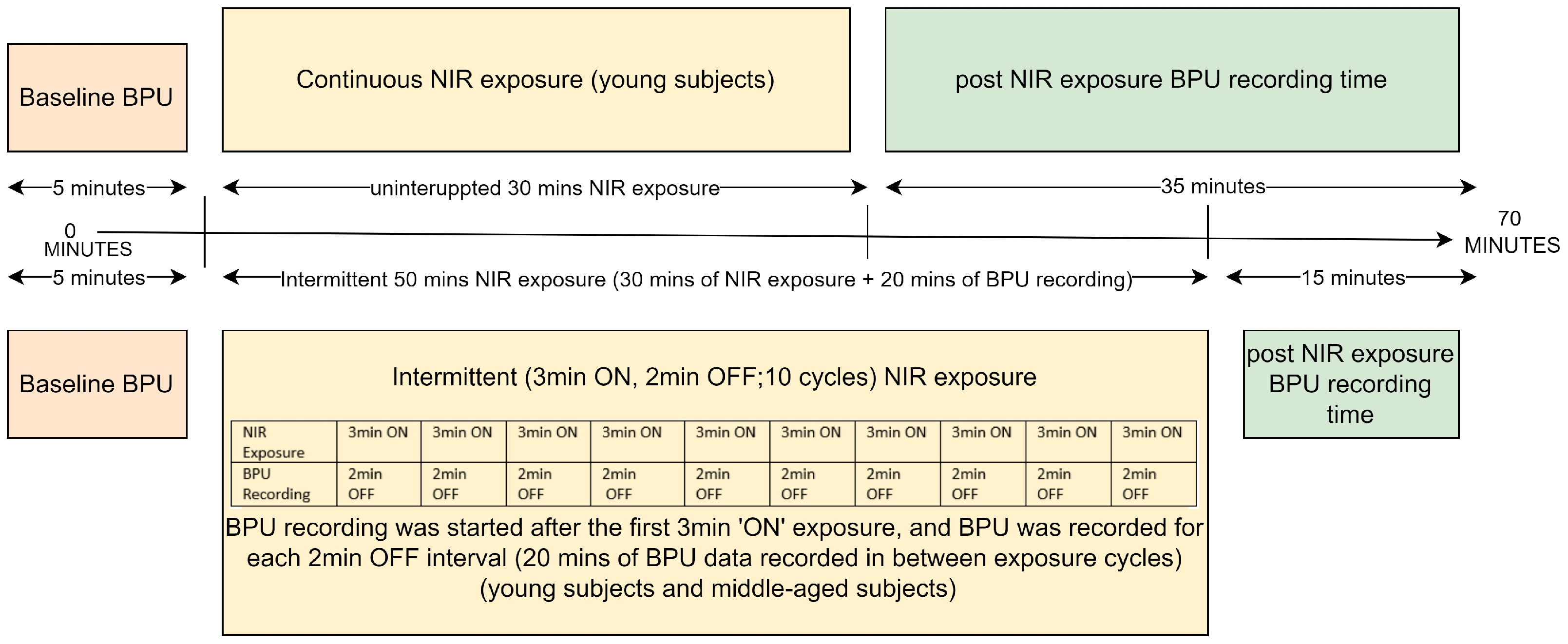

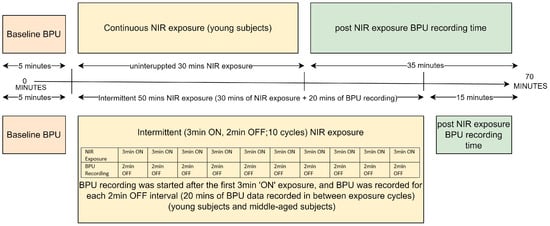

Experiment 1 involved young subjects (n = 12) and used 30 min of continuous NIR light exposure on the left lateral upper arm, and BPU was recorded before and for 35 min post-exposure. Experiment 2 included the same young subjects and used intermittent NIR light exposure (3 min ON, 2 min OFF, 10 cycles of NIR light exposure with altogether 20 min of BPU recording between the cycles) at the same skin site. BPU was also recorded for 15 min post-exposure. Experiment 3 resembled experiment 2 except that it was performed on middle-aged subjects (n = 12). BPU data collection during NIR exposures was challenging due to small differences in wavelengths: NIR was 890 nm, while LDF operates at 830 ± 10 nm. During near-infrared (NIR) exposure, BPU data acquisition was disrupted because the 890 nm NIR light overlapped with the wavelength range of the detector of the LDF. Consequently, simultaneous NIR exposure and BPU recording was not feasible. Hence, BPU could only be recorded for 35 min post-continuous exposure. During intermittent exposure, we initiated BPU recording after the initial 3-min NIR exposure and continued to record during all the “OFF” sessions (altogether 20 min). This approach allowed us to examine how blood flow changed between exposure sessions. Control experiments followed the primary experiment protocol, targeting approximately the same site on the upper left arm. The continuous control experiment (n = 7) involved young subjects and replicated the main protocol, except without NIR light exposure. Blood Perfusion Units (BPU) were recorded for 35 min post-exposure. The intermittent control experiment included young subjects (n = 5). It mimicked the intermittent protocol of the main experiments (3 min ON, 2 min OFF, totaling 10 cycles, with a BPU recording period of 20 min between exposure shots) at the identical skin site. BPU was recorded for an additional 15 min post-exposure. The control experiments aimed to investigate the impact on blood flow attributable to the heat generated by the active LEDs. In middle-aged subjects, the intermittent control experiment (n = 6) closely resembled the same experiment in young subjects. An overview of the mode of intervention and timeline for all placebo and active NIR light exposures of all three experiments are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Experiment Protocol Timeline.

Local skin blood flow was recorded for 5 min prior to all interventions, for 35 min following continuous NIR exposure, for 20 min during the OFF intervals during intermittent NIR exposures, and for 15 min post intermittent exposure (Figure 2). The skin temperature was recorded using an IR FLIR thermal camera which was positioned 7 to 10 cm from the intervention site. Heart rate and blood pressure (BP) (the mean of the last two of three consecutive BP readings taken 1 min apart) were measured by an automated device (M7, Intelli IT, Omron Healthcare Co., Kyoto, Japan) both at baseline and post-exposure. The parameters of NIR light exposure protocol are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of NIR device and NIR exposure.

The primary outcome was the percentage change in local blood flow (BPU) from baseline. The secondary outcome was the absolute change in local skin temperature from the baseline.

2.4. Data Analysis, Statistical Analysis, and Data Presentation

Sample calculation was not performed due to a lack of previous data. LDF data was recorded as 10 BPU/s. The average of the last 5 min before initiation of intervention was used as the baseline. The BPU data, collected over a 35-min duration post-continuous exposure and 35 min for intermittent exposure (comprising 20 min between exposures and 15 min post-exposure), were averaged for each 5-min interval, and the percentage change from baseline was calculated for every single time interval after NIR light exposure (total of seven time intervals). All the initial data analysis was performed in MATLAB version R2020b, and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9. As the data was not normally distributed, we used the Wilcoxon sign rank test to analyze the NIR light exposure effect (experiments 1, 2, and 3) for all seven time intervals individually, which allowed us to identify specific time intervals where NIR light exposure intervention resulted in significantly greater BPU-responses than placebo exposure. We used a Wilcoxon rank sum test to compare the mode of NIR light exposure and the effect of age between young and middle-aged groups. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. No adjustments for multiple tests were performed. No statistical tests were performed for the control experiments because of the low number of participants. Data are presented as means ± SD or medians ± CI unless otherwise specified. Data were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 9.

3. Results

3.1. Subject Characteristics

The baseline and post-exposure characteristics of study participants are given in Table 2. No participants were excluded from the study, and no adverse effects of NIR light exposure or the experiment procedures were observed.

Table 2.

Data are presented as means (range).

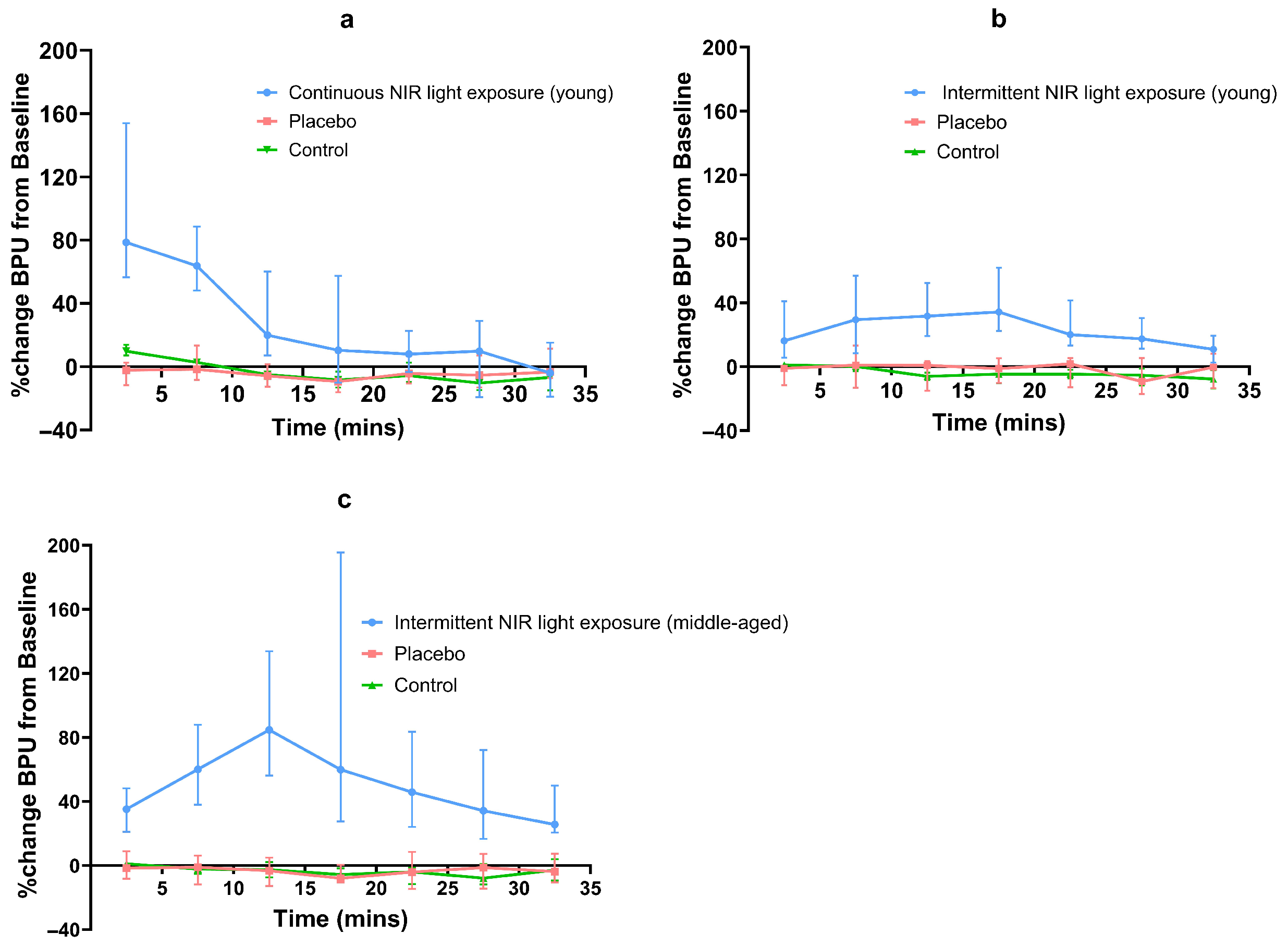

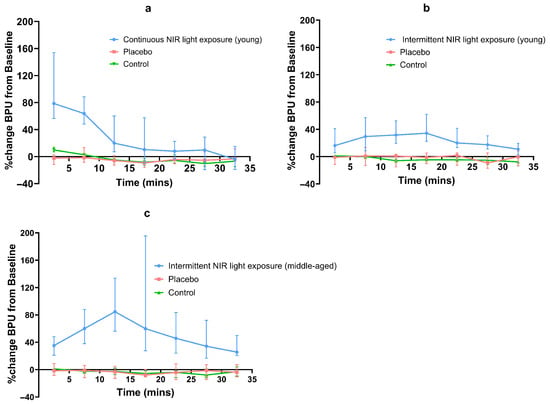

Both continuous and intermittent NIR light exposure led to an increase in skin blood flow. This increase varied with time for all interventions. In young subjects, continuous and intermittent NIR light exposure (experiments 1 and 2) increased local skin blood flow by a median maximum of 79% and 34%, respectively. In middle-aged subjects, intermittent NIR light exposure (experiment 3) increased local skin blood flow by a median maximum of 85%. For continuous NIR exposure (experiment 1), maximal BPU was observed in the 0–5 min post-exposure interval. For intermittent exposure (experiments 2 and 3), maximal BPU was observed at 15–20 min and 10–15 min intervals during the NIR exposure, respectively (Table 3) (Figure 3). In both age groups, the median percentage change in BPU from baseline for all placebo exposures (experiments 1, 2, and 3) was either minimal or negative.

Table 3.

Maximal median BPU.

Figure 3.

Line graph of percentage median (95% CI) BPU changes from baseline for NIR and placebo exposures; (a) continuous NIR exposure in young subjects, (b) intermittent NIR exposure in young subjects, (c) intermittent exposure in middle-aged subjects.

In young subjects, the median (95% CI) baseline BPU values were 35 (29, 46), 38 (29, 41) before continuous NIR light exposure and placebo, and 38 (25–46) and 41 (37, 46) before intermittent NIR light exposure and placebo, respectively. In middle-aged subjects, the median (95% CI) baseline BPU values were 34 (28–46) and 44 (37, 48) for intermittent NIR light exposure and placebo, respectively. We observed a considerable inter-individual variation in local skin blood flow response to all NIR light exposures.

3.2. Effect of Mode of NIR Light Exposure

In young subjects, after continuous NIR light exposure, only the BPU values for the first four time intervals were significantly increased compared to placebo exposure (p < 0.0005, p < 0.0005, p < 0.001, p < 0.02, respectively). When comparing intermittent NIR light exposure and placebo exposure in young subjects, BPU values were significantly higher during all seven time intervals (p < 0.0005 for the first six time intervals and p < 0.02 for the last time interval). In middle-aged subjects, a comparison between the intermittent exposure and the placebo showed significantly increased BPU values for all seven time intervals (p < 0.0005 for all time intervals) (Figure 3).

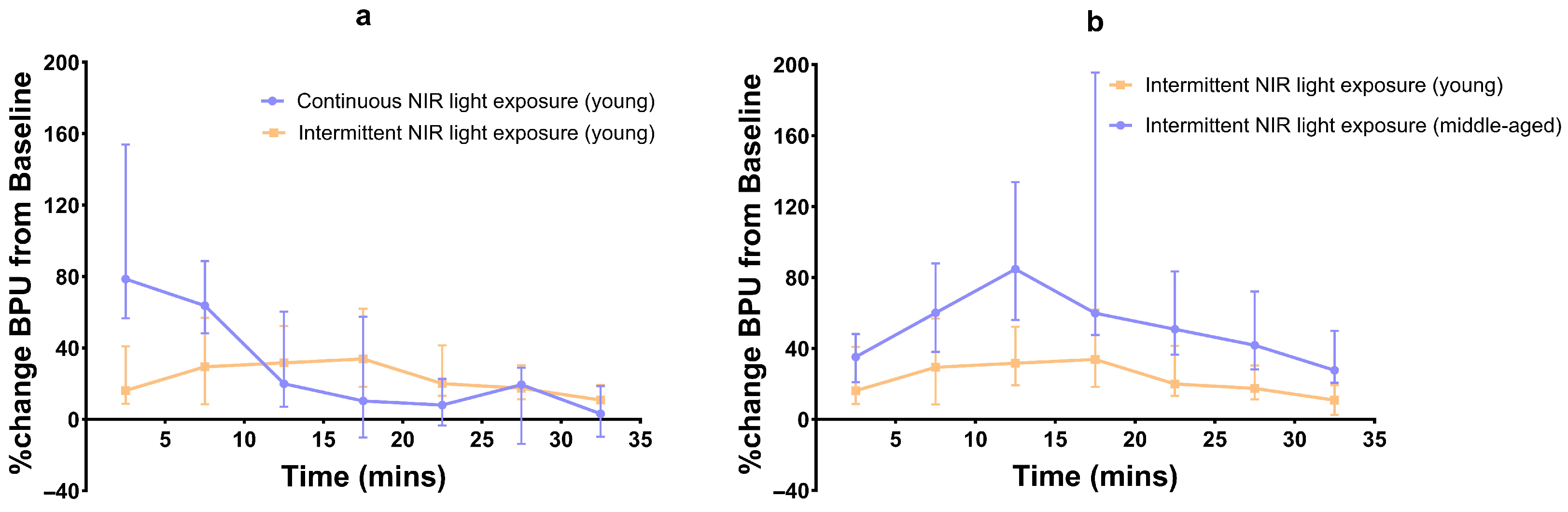

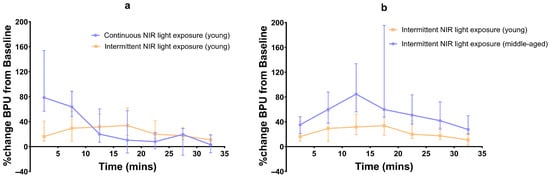

When comparing the continuous and intermittent exposures in young subjects, significant differences in BPU values were observed only for the first two time intervals (p < 0.001 and p < 0.02) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Line graph of percentage median (95% CI) BPU changes from baseline; (a) continuous vs. intermittent NIR exposure in young subjects, and (b) intermittent NIR exposure in young vs. middle-aged subjects.

3.3. Effect of Age

Compared to young subjects, the blood flow in middle-aged subjects after intermittent NIR light exposure was significantly higher during all seven time intervals (p < 0.01, p < 0.02, p < 0.001, p < 0.01, p < 0.0004, p < 0.0007, and p < 0.0002, respectively) (Figure 4).

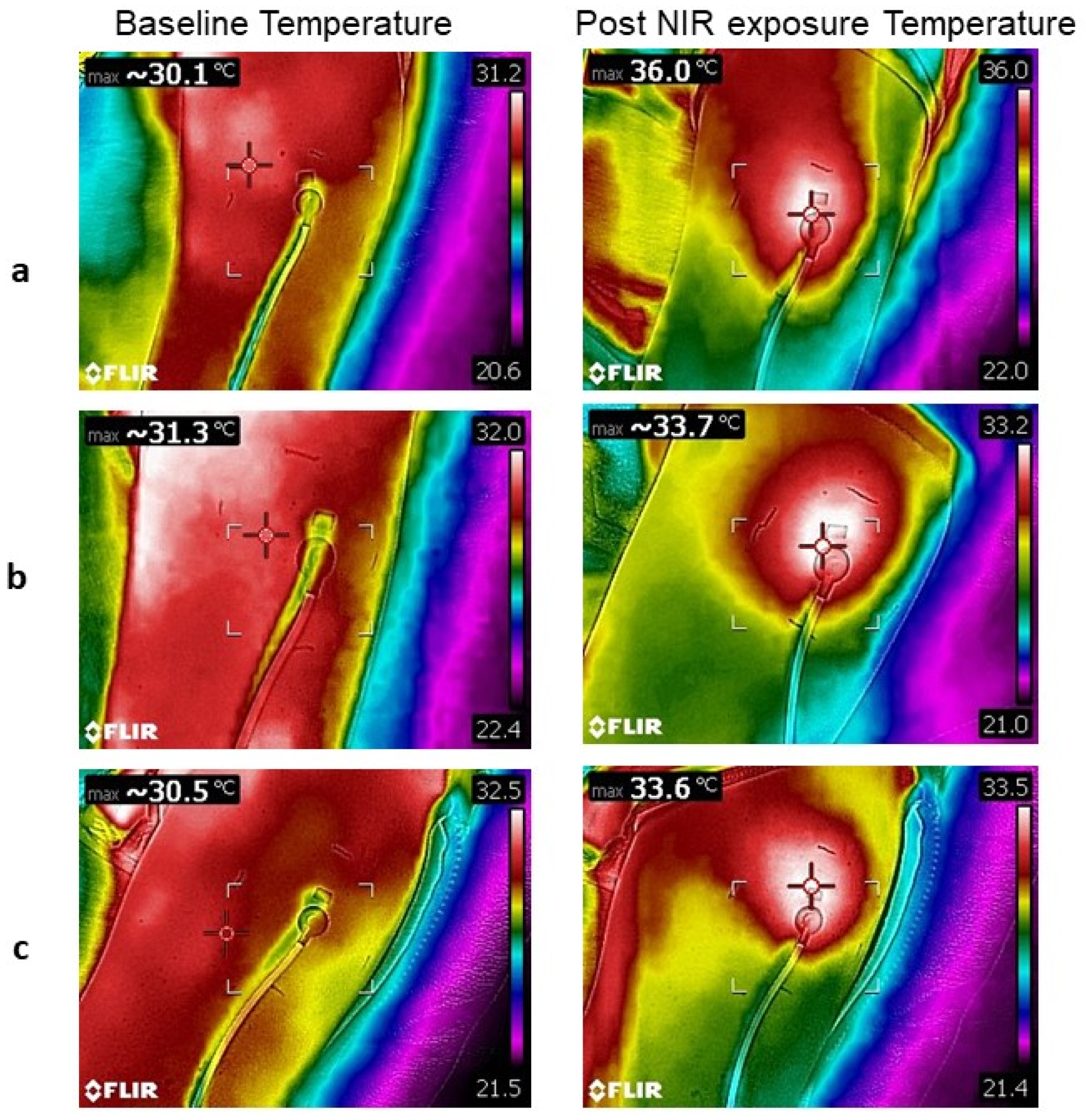

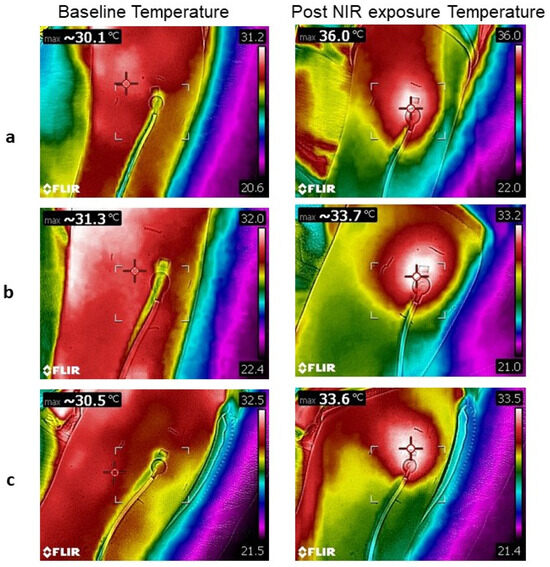

3.4. Effect on Skin Temperature

For young subjects, the mean maximum intervention site skin temperature increased by 6 °C after continuous NIR light exposure (experiment 1). In comparison, it increased only by 2 °C after intermittent NIR exposure in both age groups (experiments 2 and 3) (Table 4, Figure 5). For the placebo NIR light exposures, the mean maximum intervention site skin temperature decreased by −1.2 °C after continuous exposures (experiment 1). Additionally, after intermittent placebo exposure, the temperature decreased by −0.8 °C in the young group and by −1.1 °C in the middle-aged group (experiments 2 and 3) (Table 4). For the control groups, the mean maximum intervention site skin temperature increased by 2.1 °C after continuous control, while it decreased by −0.7 °C after intermittent control in both age groups (Table 5). No statistical testing was performed on the temperature change.

Table 4.

Baseline intervention skin site temperature and post-NIR exposure temperature.

Figure 5.

Thermal images at baseline and post NIR light exposure. Continuous exposure in a young subject (a). Intermittent exposure in a young subject (b). Intermittent exposure in a middle-aged subject (c). The cross in thermal pictures indicates the site of the highest temperature.

Table 5.

Baseline intervention skin site temperature and post control temperature.

4. Discussion

We used a novel approach to investigate the effects of PBM (NIR light exposure) on local skin blood flow. Our results demonstrate that the change in blood flow following 890 nm NIR light exposure is modified by the mode of irradiation and subjects’ age. In young subjects, continuous exposure resulted in a 79% increase in blood flow, while intermittent exposure increased blood flow by 34%. In contrast, the same intermittent exposure in middle-aged subjects led to an 85% increase in skin blood flow, exceeding the young group’s response. Continuous exposure in young subjects resulted in a significant increase in blood flow only for the first 20 min post-exposure, whereas intermittent exposure led to a significant increase in blood flow throughout the exposure and post-exposure periods in both young and middle-aged subjects. These results indicate that both young and middle-aged individuals exhibited a significant increase in skin blood flow following NIR light exposure, albeit with slightly different temporal patterns depending on the mode of irradiation.

Although multiple studies have investigated the effect of R/NIR light exposure on skin blood flow in healthy people and patients with diabetes and have reported positive results [26,27,29,30], the present study is the first study to investigate the effects of NIR light exposure on the local skin blood flow using different modes of irradiation in different age groups. Further, using a placebo intervention (no thermal conduction or NIR light exposure) and a control intervention (with direct thermal conduction on the skin while blocking NIR light) helped us elucidate the heat effect from the pure effect of NIR light. Additionally, comparing intermittent exposure between age groups allowed us to discern the potential influence of subjects’ age on changes in skin microcirculation.

Several studies have demonstrated that R/NIR light increases local blood flow, which is either associated with localized NO release or stimulation of NO synthase gene expression in cell systems [11,16,19,43]. Samoilova et al. [26,27] have also reported that irradiating the skin in healthy volunteers and diabetic patients using polarized visible light for 5 min (385–750 nm, 40 mW/cm2, and 12 J/cm2) resulted in an increase in blood flow (measured by LDF) that peaked at 30 min and was reported higher than baseline even at 90 min post-exposure. The study also implies that the activation of NO synthesis in the irradiated area is responsible for increased blood flow. Although the mechanisms behind increased blood flow following R/NIR light exposure are not entirely understood, our study supports that NIR light exposure increases the local skin blood flow, which might be NO-dependent [11,26,27]. However, we did not measure the NO content in the present study. Our observations that both intermittent and continuous modes of irradiation increase blood flow are in line with the results in a recent study by Gavish et al. [30], which reported a 54% increase in local skin blood flow in the palm after 5 min of wrist irradiation with 830 nmNIR (irradiance: 55 mW/cm2; fluence: 16.5 J/cm2). Gavish et al. reported that skin blood flow increased in the 20-min follow-up period after irradiation; however, we observed the maximum blood flow (79%) response in the 0–5 min interval after continuous NIR light exposure cessation in young adults. For intermittent NIR light exposure in young and middle-aged adults, maximum blood flow was observed at 15–20 min (34%) and 10–15 min (85%) during exposure, accordingly. After ceasing the NIR light exposure, the blood flow continued to decline. However, continuous NIR light exposure resulted in a faster decline in blood flow than intermittent exposure, which led to a more sustained vasodilatory effect. This observation might suggest that intermittent exposure with OFF periods should be the preferred method if a more lasting effect is the goal of the intervention. The study by Gavish et al. [30] also indicates that skin temperature at the intervention site might influence the response to NIR PBM. That study indicated that only subjects with a temperature increase of at least 0.5 °C were responders. For continuous NIR light exposure in the young subjects’ group in our study, the subjects with a higher increase in intervention skin site temperature from baseline had a higher increase in blood flow. However, we did not observe that the baseline or post-irradiation temperature influenced the increase in skin blood flow for intermittent NIR exposure for both young and middle-aged groups.

Another study by Michael et al. [29] showed that continuous 30 min of NIR light exposure in contact mode (890 nm, 60 mW/cm2, 108 J/cm2 over an area of 22.5 cm2) led to a significant increase in the skin blood flow of foot at both the capillary and compartment levels compared to placebo and control groups. However, the increase in skin blood flow was relatively small (20% as measured by LDF) as compared to our experiment with continuous NIR exposure for 30 min (79%), where we performed the exposure using a modified version of the same device (Anodyne therapy system) in non-contact mode. The differences in response might be due to the parameters of our modified device and the difference in intervention site.

Furthermore, our study also demonstrated that continuous NIR light exposure results in more pronounced direct optical energy (heat) deposition into the skin at the intervention site than intermittent NIR exposure. This distinction is evident in the observed differences between continuous and intermittent control experiments (Table 5). In young subjects, continuous NIR exposure caused a 6 °C increase in skin temperature from baseline, whereas intermittent exposure led to only a mild 2 °C increase in both young and middle aged subject groups. In contrast, all placebo groups showed a decrease in temperature (Table 4). Furthermore, the continuous control group showed a temperature increase of 2.1 °C, whereas both intermittent control groups showed a decrease of −0.7 °C (Table 5). These temperature differences might be the reason why blood flow after the continuous NIR exposure session (79%) is significantly higher than for the intermittent exposure session (34%) in young subjects. NIR light exposure may increase the temperature by several mechanisms, including local vasodilation or heat deposited by LEDs. However, it should be noted that we used a non-contact NIR light exposure protocol to avoid heat conduction from the LEDs to the skin. It is possible that the temperature during the continuous NIR light exposure and continuous control significantly increased because the skin was continuously irradiated with NIR light, i.e., the light was delivered over a shorter period of time, reducing the body’s ability to transport heat away from the illuminated area. However, for intermittent NIR exposure, the skin was exposed to NIR light in 10 shots of 3 min ON with 2 min OFF times between each exposure, and the OFF time allowed the heat to diffuse away from the intervention skin site (or a cooling effect). As such, we assume that the higher percentage increase in skin blood flow for the continuous NIR intervention could be partly due to heat instead of a pure NIR effect. It is crucial to elucidate the effect of the deposited heat from the pure NIR effect because nitric oxide is also reported to contribute to the active cutaneous vasodilation response following local heat application to the skin [34,44]. Importantly, however, the continuous control group, despite showing a temperature increase comparable to that of the intermittent NIR exposure groups, did not show similar increases in blood flow, indicating the effect of NIR exposure is attributable to the light and not to heat generated by the light source.

No previous study in healthy subjects has investigated the possible effect of age on the blood flow response to NIR light exposure. We observed that intermittent NIR light exposure led to a significantly higher median percentage change in blood flow in middle-aged compared to young subjects (85% vs. 34%). This might suggest that middle-aged individuals have a more pronounced vascular response to PBM, possibly due to age-related changes in skin physiology. A marked site and age effect on the skin blood flow is known in the literature [44,45,46]. The effect of age might be attributed to the fact that R/NIR light affects the cellular processes in young and middle-aged people differently, considering that R/NIR light exposure boosts mitochondrial membrane potential and produces ROS when normal cells are exposed, but in cases of low mitochondrial potential due to oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, or electron transport inhibition, light absorption restores potential and reduces ROS production [1,3,10,11,16] when it is applied to improve tissue or muscle injury (diseased or aged cells). We also observed that after initiating intermittent NIR light exposure, maximal BPU was achieved between 10–15 and 15–20 min in middle-aged adults and young adults, accordingly, and further intermittent NIR light exposure decreased the skin blood flow, which might be explained by biphasic dose response [31]. In other words, it implies that after the biostimulation is achieved, further irradiation (over-dosing) might replace the stimulation with bioinhibition (hence the decrease in percentage increase in the local skin blood flow in our study for intermittent exposure sessions). In contrast, insufficient R/NIR application (under-dosing) might lead to no response [31]. Overall, our results indicate that NIR light exposure appears to induce a significant increase in local skin blood flow in the upper lateral arm, which is modified by the mode of radiation and age of the subjects.

The observed relationship between changes in skin temperature and blood flow responses should be interpreted in the context of this study, and further research is necessary to fully understand the underlying mechanisms and optimize NIR exposure protocols for specific therapeutic applications.

The small sample size is a limitation of this study. The response to NIR light exposure demonstrates significant inter-individual and intra-individual variations, and a larger sample size would have produced more detailed and reliable results. In addition, intrinsic skin characteristics such as tissue thickness, and optical properties are known to influence light absorption, scattering, and penetration depth in NIR range [37], thereby modulating PBM efficacy. Variations in tissue composition [47] across individuals may therefore have contributed to the observed variability in BPU response. Another limitation of the study is that it was not possible to record blood flow during the NIR application as the flowmeter and the NIR light source operate at approximately the same wavelengths (830 ± 10 nm and 890 nm, respectively), and using them together would have caused overestimation of BPU. Other limitations include the small area of skin illuminated by the LDF and uncertainty about how much time is required to achieve a maximal BPU response before a decline in effect is observed. However, using study subjects as their own controls and performing a placebo adds to the strengths of the current study. Both the active and the placebo interventions were performed in non-contact mode to reduce or eliminate the direct heat conduction as a cause of increased blood flow. By this approach, we investigated the “pure” NIR light effect, which is a strength of our observations. Conducting both placebo and NIR light exposure at the same skin site is also a study strength, accounting for variations in skin vasculature across different skin areas. Furthermore, employing intermittent exposure allowed us to observe the timeline of the BPU response, and prolonged intermittent NIR exposure might lead to a decrease in blood flow, which adds to the strengths of the study. In the current study, we used a one-time application of NIR light. More research and more extensive and sophisticated experiments are needed to determine whether the observed effects are reproducible and what the appropriate parameters, mode of irradiation, and fluence are to achieve a maximum increase in local blood flow with minimal effect from heat and other factors that could affect this response.

5. Conclusions

This placebo-controlled study indicates that NIR PBM increases local skin blood flow in both young and middle-aged healthy subjects. The effect is modified both by age and mode of irradiation. Further research and more extensive and sophisticated experiments are needed to determine whether the observed effects are reproducible and what are the appropriate parameters, mode of irradiation, and fluence to achieve a maximal increase in local blood flow with minimal effect from deposited optical energy (heat).

These experiments were not registered to protect possible intellectual property rights.

Author Contributions

M.R.: Methodology, Visualization, Software Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data collection, Manuscript Draft; P.C.B.: Modification of Anodyne Device, Calculation of Power Density and Dosage, Software Validation, Review and Editing; M.K.Å.: Methodology, Visualization, Software, Review and Editing; R.E.: Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization; D.R.H.: Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization; S.C.C.: Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Project Administration, Review and Editing, Funding acquisition; S.M.C.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Review and Editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Helse Midt-Norge (grant number 90647400) and the Research Council of Norway (grant number 294828).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee (approval number 180559) and was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants signed an informed consent before participating in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PBM | Photobiomodulation |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| BPU | Blood Perfusion Units |

| LDF | Laser Doppler FLowmeter |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

References

- Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation or low-level laser therapy. J. Biophotonics 2016, 9, 1122–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Shining light on the head: Photobiomodulation for brain disorders. BBA Clin. 2016, 6, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms and applications of the anti-inflammatory effects of photobiomodulation. AIMS Biophys. 2017, 4, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavish, L.; Perez, L.S.; Reissman, P.; Gertz, S.D. Irradiation with 780 nm diode laser attenuates inflammatory cytokines but upregulates nitric oxide in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages: Implications for the prevention of aneurysm progression. Lasers Surg. Med. 2008, 40, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dompe, C.; Moncrieff, L.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Bruska, M.; Dominiak, M.; Mozdziak, P.; Skiba, T.H.I.; et al. Photobiomodulation—Underlying mechanism and clinical applications. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, H.T.; Buchmann, E.V.; Dhokalia, A.; Kane, M.P.; Whelan, N.T.; Wong-Riley, M.T.; Eells, J.T.; Gould, L.J.; Hammamieh, R.; Das, R.; et al. Effect of NASA light-emitting diode irradiation on molecular changes for wound healing in diabetic mice. J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 2003, 21, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyebode, O.; Houreld, N.N.; Abrahamse, H. Photobiomodulation in diabetic wound healing: A review of red and near-infrared wavelength applications. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2021, 39, 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Gupta, A. Noninvasive red and near-infrared wavelength-induced photobiomodulation: Promoting impaired cutaneous wound healing. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2017, 33, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karu, T. Mitochondrial mechanisms of photobiomodulation in context of new data about multiple roles of ATP. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2010, 28, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms and Mitochondrial Redox Signaling in Photobiomodulation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2018, 94, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. The role of nitric oxide in low level light therapy. In Mechanisms for Low-Light Therapy III; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2008; Volume 6846, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Poyton, R.O.; Ball, K.A. Therapeutic photobiomodulation: Nitric oxide and a novel function of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. Discov. Med. 2011, 11, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kochman, A.B. Monochromatic Infrared Photo Energy and Physical Therapy for Peripheral Neuropathy: Influence on Sensation, Balance, and Falls. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2004, 27, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, R.C.; Ong, A.A.; Albasha, O.; Bass, K.; Arany, P. Photobiomodulation Therapy for Wound Care: A Potent, Noninvasive, Photoceutical Approach. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2019, 32, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karu, T.I. Mitochondrial signaling in mammalian cells activated by red and near-IR radiation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Freitas, L.F.; Hamblin, M.R. Proposed Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation or Low-Level Light Therapy. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2016, 22, 7000417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Sharma, S.K.; Carroll, J.; Hamblin, M.R. Biphasic dose response in low level light therapy—An update. Dose Response 2011, 9, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Dai, T.; Sharma, S.K.; Huang, Y.Y.; Carroll, J.D.; Hamblin, M.R. The nuts and bolts of low-level laser (light) therapy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Keszler, A.; Lindemer, B.; Weihrauch, D.; Jones, D.; Hogg, N.; Lohr, N.L. Red/near infrared light stimulates release of an endothelium dependent vasodilator and rescues vascular dysfunction in a diabetes model. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 113, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, N.L.; Keszler, A.; Pratt, P.; Bienengraber, M.; Warltier, D.C.; Hogg, N. Enhancement of nitric oxide release from nitrosyl hemoglobin and nitrosyl myoglobin by red/near infrared radiation: Potential role in cardioprotection. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009, 47, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, E.; Signore, A.; Aicardi, S.; Zekiy, A.; Utyuzh, A.; Benedicenti, S.; Amaroli, A. Experimental and Clinical Applications of Red and Near-Infrared Photobiomodulation on Endothelial Dysfunction: A Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Mio, Y.; Pratt, P.F.; Lohr, N.; Warltier, D.C.; Whelan, H.T.; Zhu, D.; Jacobs, E.R.; Medhora, M.; Bienengraeber, M. Near infrared light protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia and reoxygenation injury by a nitric oxide dependent mechanism. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009, 46, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Zheng, X.; He, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Luo, P.; Xia, Z. Therapeutic efficacy of early photobiomodulation therapy on the zones of stasis in burns: An experimental rat model study. Wound Repair Regen. 2018, 26, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriyama, Y.; Moriyama, E.H.; Blackmore, K.; Akens, M.K.; Lilge, L. In vivo study of the inflammatory modulating effects of low-level laser therapy on iNOS expression using bioluminescence imaging. Photochem. Photobiol. 2005, 81, 1351–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriyama, Y.; Nguyen, J.; Akens, M.; Moriyama, E.H.; Lilge, L. In vivo effects of low level laser therapy on inducible nitric oxide synthase. Lasers Surg. Med. 2009, 41, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilova, K.A.; Zhevago, N.A.; Menshutina, M.A.; Grigorieva, N.B. Role of nitric oxide in the visible light-induced rapid increase of human skin microcirculation at the local and systemic level: I. diabetic patients. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2008, 26, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilova, K.A.; Zhevago, N.A.; Petrishchev, N.N.; Zimin, A.A. Role of nitric oxide in the visible light-induced rapid increase of human skin microcirculation at the local and systemic levels: II. Healthy volunteers. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2008, 26, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindl, A.; Heinze, G.; Schindl, M.; Pernerstorfer-Schön, H.; Schindl, L. Systemic effects of low-intensity laser irradiation on skin microcirculation in patients with diabetic microangiopathy. Microvasc. Res. 2002, 64, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, M.C.; Cheing, G.L. Immediate effects of monochromatic infrared energy on microcirculation in healthy subjects. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2012, 30, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavish, L.; Hoffer, O.; Rabin, N.; Halak, M.; Shkilevich, S.; Shayovitz, Y.; Weizman, G.; Haim, O.; Gavish, B.; Gertz, S.D.; et al. Microcirculatory response to photobiomodulation—Why some respond and others do not: A randomized controlled study. Lasers Surg. Med. 2020, 52, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zein, R.; Selting, W.; Hamblin, M.R. Review of light parameters and photobiomodulation efficacy: Dive into complexity. J. Biomed. Opt. 2018, 23, 120901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M. Nonthermoregulatory control of human skin blood flow. J. Appl. Physiol. 1986, 61, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrofsky, J.; Goraksh, N.; Alshammari, F.; Mohanan, M.; Soni, J.; Trivedi, M.; Lee, H.; Hudlikar, A.N.; Yang, C.H.; Agilan, B.; et al. The ability of the skin to absorb heat; the effect of repeated exposure and age. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17, CR1–CR8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charkoudian, N. Skin blood flow in adult human thermoregulation: How it works, when it does not, and why. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2003, 78, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ash, C.; Dubec, M.; Donne, K.; Bashford, T. Effect of wavelength and beam width on penetration in light-tissue interaction using computational methods. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, L.; Barnard, I.R.M.; McMillan, L.; Ibbotson, S.H.; Brown, C.T.A.; Eadie, E.; Wood, K. Depth penetration of light into skin as a function of wavelength from 200 to 1000 nm. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkatov, A.N.; Genina, E.A.; Kochubey, V.I.; Tuchin, V.V. Optical properties of human skin, subcutaneous and mucous tissues in the wavelength range from 400 to 2000 nm. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2005, 38, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, T.A.; Morries, L.D. Near-infrared photonic energy penetration: Can infrared phototherapy effectively reach the human brain? Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalkar, M.; Pleshko, N. Wavelength-dependent penetration depth of near infrared radiation into cartilage. Analyst 2015, 140, 2093–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heu, F.; Forster, C.; Namer, B.; Dragu, A.; Lang, W. Effect of low-level laser therapy on blood flow and oxygen-hemoglobin saturation of the foot skin in healthy subjects: A pilot study. Laser Ther. 2013, 22, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, I.; Larsson, M.; Strömberg, T. Measurement depth and volume in laser Doppler flowmetry. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 78, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, M.A.; Arce, C.H.; Byron, K.J.; Hirsch, L.J. Skin and subcutaneous adipose layer thickness in adults with diabetes at sites used for insulin injections: Implications for needle length recommendations. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2010, 26, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgård, A.; Hultén, L.M.; Svensson, L.; Soussi, B. Irradiation at 634 nm releases nitric oxide from human monocytes. Lasers Med. Sci. 2007, 22, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrofsky, J.S. Resting blood flow in the skin: Does it exist, and what is the influence of temperature, aging, and diabetes? J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracowski, J.L.; Roustit, M. Human Skin Microcirculation. Compr. Physiol. 2020, 10, 1105–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Mac-Mary, S.; Sainthillier, J.M.; Nouveau, S.; de Lacharrière, O.; Humbert, P. Age-related changes of the cutaneous microcirculation in vivo. Gerontology 2006, 52, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, T.; Wright, P.A.; Chappell, P.H. Optical properties of human skin. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 090901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.