Abstract

Extended reality (XR), encompassing virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR), is rapidly reshaping the landscape of digital interaction and immersive communication. As XR evolves toward ultra-realistic, real-time, and interactive experiences, it places unprecedented demands on wireless communication systems in terms of bandwidth, latency, and reliability. Conventional RF-based networks, constrained by limited spectrum and interference, struggle to meet these stringent requirements. In contrast, visible light communication (VLC) offers a compelling alternative by exploiting the vast unregulated visible spectrum to deliver high-speed, low-latency, and interference-free data transmission—making it particularly suitable for future XR environments. This paper presents a comprehensive survey on VLC-enabled XR communication systems. We first analyze XR technologies and their diverse quality-of-service (QoS) and quality-of-experience (QoE) requirements, identifying the unique challenges posed to existing wireless infrastructures. Building upon this, we explore the fundamentals, characteristics, and opportunities of VLC systems in supporting immersive XR applications. Furthermore, we elaborate on the key enabling techniques that empower VLC to fulfill XR’s stringent demands, including high-speed transmission technologies, hybrid VLC-RF architectures, dynamic beam control, and visible light sensing capabilities. Finally, we discuss future research directions, emphasizing AI-assisted network intelligence, cross-layer optimization, and collaborative multi-element transmission frameworks as vital enablers for the next-generation VLC–XR ecosystem.

1. Introduction

The advent of XR technologies has initiated a transformative shift in how humans perceive and interact with digital environments, giving rise to the broader concept of the metaverse—a fully virtualized and interactive digital world that mirrors and extends physical reality. In recent years, this vision has captured significant attention from the research community, telecommunication industry, and standardization bodies. This new wave of digital transformation indicates a paradigm shift beyond traditional information and communication technologies, which have reached near saturation in terms of service capability, performance, and scalability. As users increasingly demand richer, more realistic, and multi-sensory experiences, service providers are driven to advance toward immersive, intelligent, and ultra-low latency communication systems.

At the core of this digital evolution lie the promising XR technologies, comprising VR, AR, and MR. More specifically, VR immerses users in a fully simulated 3D environment that excludes physical surroundings; AR overlays digital content onto real world scenes, enhancing contextual awareness and interaction; and MR enables dynamic integration between virtual and physical elements, allowing users to interact naturally with both. Together, these technologies form the fundamental enablers of interconnected, 3D virtual spaces that blend physical and digital worlds. From immersive entertainment and gaming to remote education, collaborative design, and medical training, XR applications are driving the evolution of next-generation user interfaces and interaction paradigms. Therefore, according to IDC, global VR headset shipments are expected to experience explosive growth in 2026, with a year-on-year increase of 87%. This surge will push the annual shipment volume beyond the previous peak of 11.2 million units recorded in 2021 during the pandemic. Furthermore, between 2025 and 2029, International Data Corporation (IDC) anticipates a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 38.6%. As a result, the global XR market is projected to exceed USD 100 billion by 2030, with compound annual growth driven by adoption in entertainment, industrial design, healthcare, education, and telepresence [1,2,3,4].

Despite this promising momentum, most current XR applications still remain at an early stage of development, focusing primarily on 360° immersive video playback or pre-rendered, cached content rather than truly interactive, real-time experiences [5,6]. These applications typically adjust the displayed scene based on the user’s head orientation or viewpoint without involving deep bidirectional interaction with the virtual environment, consequently exhibiting moderate demands on network performance. However, as XR evolves toward real-time, interactive, and collaborative applications, network latency, particularly the motion-to-photon (MTP) delay, is becoming a critical bottleneck. It has been proven that the MTP should be maintained below 20 ms [7] to avoid motion sickness, disorientation, and reduced immersion, which severely degrade the overall QoE. In some cases, this threshold can be as low as 5 ms [8]. In addition, 360° immersive interaction demands large-scale real-time rendering and image transmission, resulting in very high data throughput requirements. For achieving seamless interaction and fully immersive experience, the communication links have to provide ultra-high bandwidth, ultra-low latency, and high reliability [9,10,11]. However, traditional wireless technologies, such as Wi-Fi 6, 5G, and millimeter wave (mmWave), face limitations including spectral congestion, interference, and high power consumption [12,13].

VLC has attracted substantial academic and industrial attention in recent years, with numerous experimental and theoretical studies demonstrating its feasibility as a high-capacity, low-latency access technology for indoor terminals [12,13,14]. Prior work has validated VLC’s capability to deliver multi Gb/s downlink throughput [15,16,17], centimeter-level positioning accuracy [18,19], and favorable spatial reuse through highly directional optical channels [20], while co-existing with conventional lighting functions. With these inherent advantages, VLC holds the potential to complement and enhance existing XR communication frameworks, addressing some of the key performance gaps in current wireless architectures. At the same time, the physical layer characteristics of VLC introduce new design opportunities, including the integration of illumination, sensing, and adaptive beam control, as well as new challenges such as uplink provisioning and maintaining reliable handover in dynamic user scenarios [14]. More importantly, VLC is not intended as a complete replacement for existing wireless paradigms. Rather, it serves as a complementary technology whose strengths can be leveraged, either independently or within hybrid VLC/RF architectures, to meet the unique end-to-end requirements of immersive XR systems [21]. In this paper we therefore examine both the demonstrated potential of VLC for indoor access and the specific research questions that must be resolved to realize its practical adoption in XR applications.

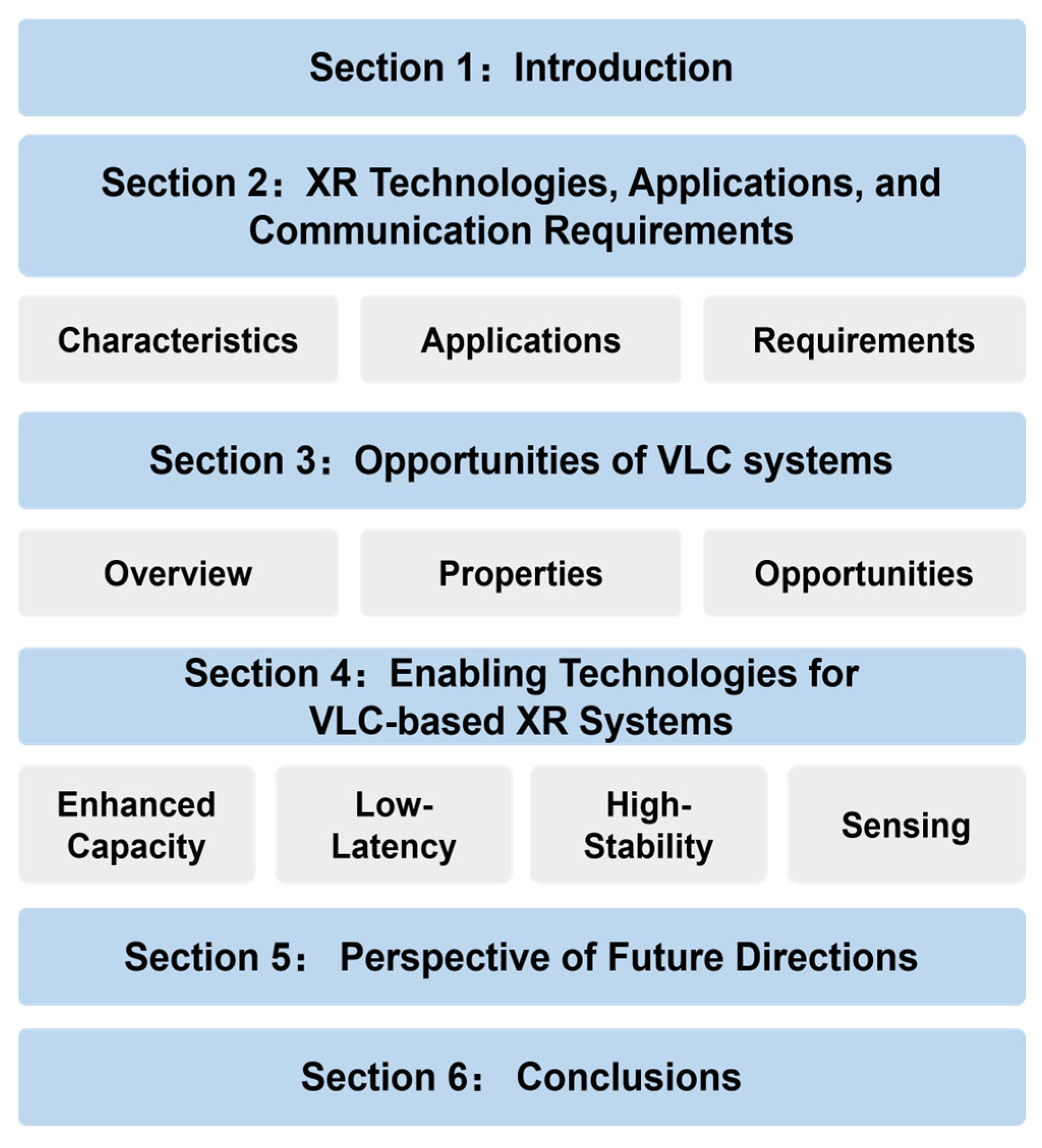

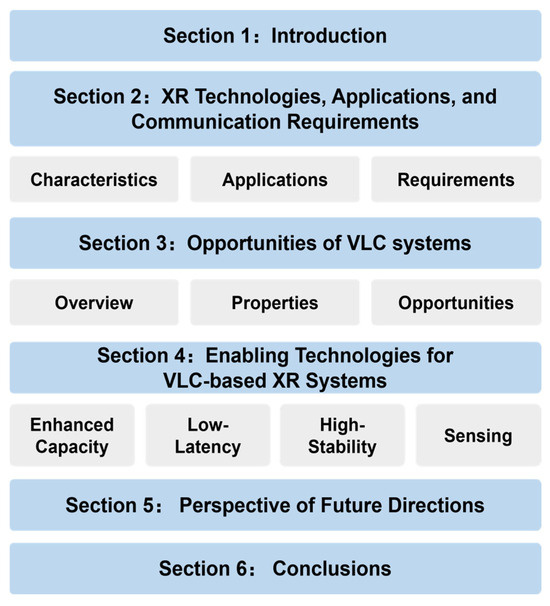

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows and as shown in Figure 1. Section 2 provides a comprehensive overview of XR technologies, covering their fundamental concepts, key application domains, and the resulting network performance requirements such as bandwidth, latency, and reliability. Section 3 introduces the fundamentals of VLC, outlining its system architecture, inherent characteristics, and the opportunities of deploying VLC in XR communication scenarios. Building on these foundations, Section 4 explores the enabling technologies that empower VLC to meet XR’s stringent performance demands, including high-capacity transmission, low-latency networking, link stability, and perception capabilities. Section 5 discusses future research directions, emphasizing emerging opportunities such as AI-driven optimization, multi-element collaborative systems, cross-layer co-design, and integrated sensing and communication (ISAC). Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary.

Figure 1.

Structure of this paper.

2. XR Technologies, Applications, and Communication Requirements

2.1. Evolution and Characteristics of XR Technologies

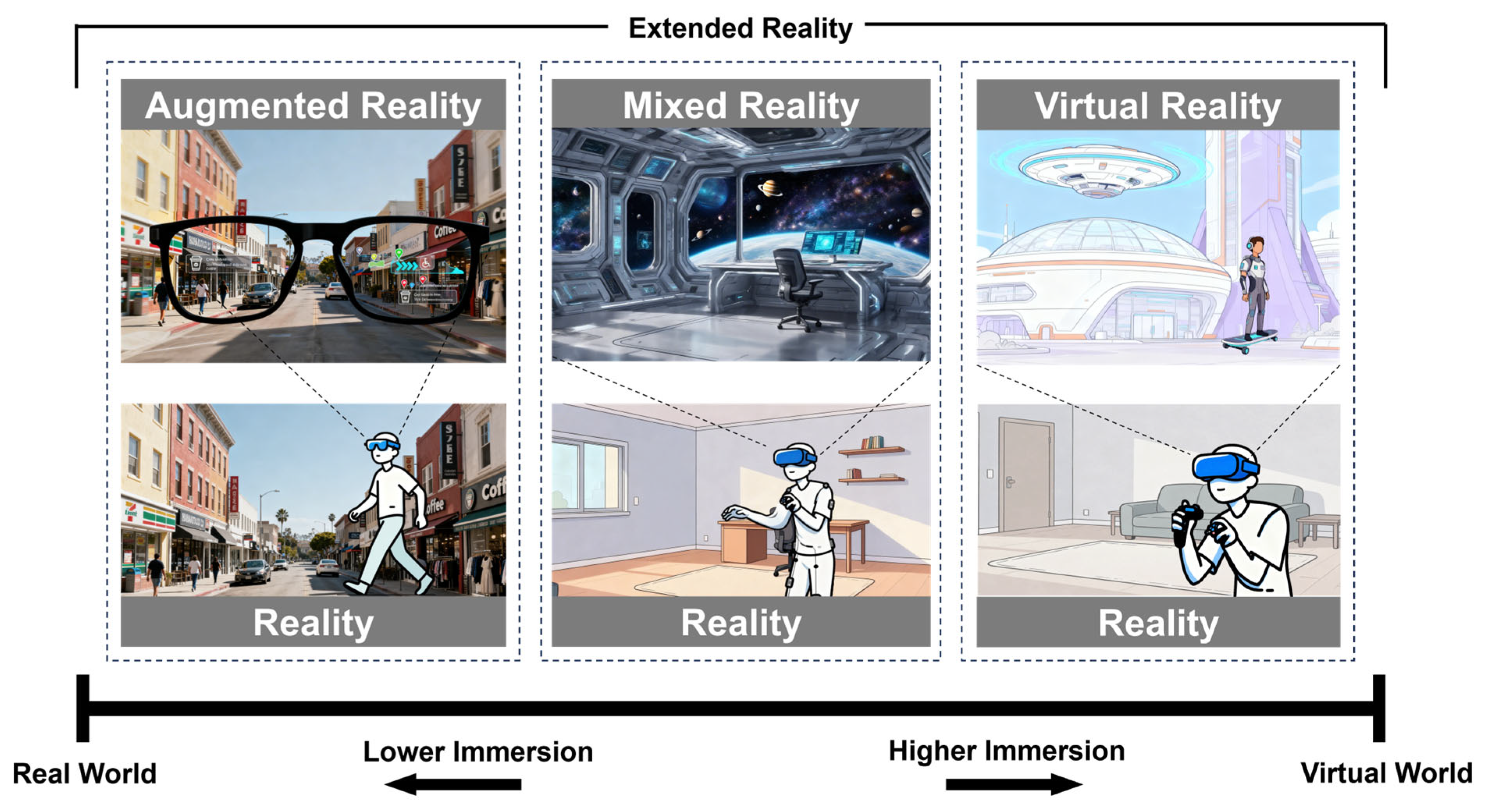

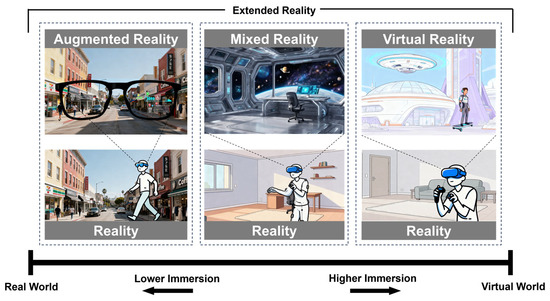

The concept of XR encompasses a family of technologies—VR, AR, and MR—which together form a continuum ranging from the real world to fully virtual environments [22], as shown in Figure 2. Collectively, these technologies represent the progressive convergence of the physical and digital domains. Over the past few decades, as the boundaries between the physical and digital worlds have gradually blurred, researchers and industry practitioners have been exploring new ways to create immersive and interactive environments that go beyond the traditional two-dimensional interfaces of computers and mobile devices.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of XR technologies and their relationship.

2.1.1. Virtual Reality

The initial virtual reality devices can be traced back to the 1950s–1960s, when Morton Heilig built a prototype of his conception dubbed the Sensorama. The Sensorama provided users with an immersive experience by combining visual, auditory, olfactory, and tactile stimuli while displaying short motion pictures [23]. In the 1980s, Jaron Lanier formally coined the term “virtual reality”, and his company VPL Research developed several commercial VR devices, propelling VR into a new stage. With the miniaturization of sensors and the popularization of head-mounted displays (HMDs), VR re-emerged in the 2010s as an accessible consumer technology, powered by advancements in visual rendering and motion tracking [24].

Modern VR systems create a computer-generated, fully immersive, and interactive digital environment that replaces a user’s perception of the real world, as Figure 2 shows. By using HMDs equipped with high-resolution screens, the visual field is entirely covered, effectively isolating the user from their physical surroundings. These devices are typically connected to a personal computer, game console, or mobile platform, which provides the computational resources for real-time rendering and scene updates. Through the integration of spatial audio, motion tracking, and haptic feedback, VR systems create a coherent multi-sensory illusion that allows users to see, hear, and even feel as though they are physically present in the simulated environment. The movements of the user are continuously captured and reflected in the virtual space, enabling natural navigation and interaction with virtual objects.

2.1.2. Augmented Reality

Unlike VR, which completely replaces the user’s surroundings, AR blends digital and real-world information within the same field of view, allowing users to remain aware of their physical context while interacting with virtual components, as depicted by Figure 2. The concept of AR was first put forward during 1990s [25], and it gradually evolved from laboratory prototypes to practical tools. The AR system relies on optical see-through displays, smartphones, or wearable glasses, equipped with cameras, depth sensors, and inertial measurement units (IMUs) to capture the surrounding environment. Then, the AR device continuously processes and aligns virtual imagery with physical landmarks using computer vision and simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) algorithms. As a result, virtual annotations or 3D objects appear fixed in space, providing spatially consistent visual feedback to the user. This capability enables intuitive interactions, such as manipulating virtual components or receiving real-time guidance.

2.1.3. Mixed Reality

MR represents the next stage in immersive technology, merging the strengths of VR and AR to enable real-time interaction between physical and virtual worlds. In MR environments, digital objects are not fully fictitious or simply superimposed but anchored in the real surroundings, responding dynamically to changes in lighting, perspective, and motion, as exhibited in Figure 2. This creates a shared space where virtual and physical entities coexist and can influence one another, offering a seamless blend of immersion and realism. The concept was formalized in the mid-1990s through the Reality–Virtuality Continuum proposed by Paul Milgram [26], defining experiences that combine real-world context with virtual interactivity.

With advances in depth sensing, 3D spatial mapping, and environment reconstruction, nowadays, MR systems can accurately perceive geometry and depth, allowing precise alignment of digital elements with the real environment. MR products, such as Microsoft HoloLens 2 and Magic Leap One [27], employ eye tracking, gesture recognition, and spatial anchoring to support interactive tasks in which users can manipulate virtual models as if they were tangible.

2.2. Applications of XR Technologies

2.2.1. Entertainment and Gaming

The entertainment industry remains one of the earliest and most influential drivers of XR development. Focusing on the gaming industry, XR-based games have evolved from simple 3D environments to large-scale interactive ecosystems that combine real-time motion tracking, haptic feedback, and 360° spatial audio to deliver high levels of immersion. According to a report by Fortune Business Insights, the global XR gaming market exceeded USD 17.96 billion in 2023 and is projected to surpass USD 180 billion by 2032 [28]. In addition to XR games, VR-based cinematic experiences, virtual concerts, and live performances [29] have also gained immense popularity.

2.2.2. Industry and Manufacturing

The industrial sector is one of the most promising areas for XR adoption, particularly in remote collaboration, maintenance, and industrial training. By integrating XR with internet of things (IoT) and digital twin technologies, engineers can visualize complex equipment in 3D, interact with live data overlays, and perform maintenance tasks with real-time remote assistance. According to PricewaterhouseCoopers, XR is expected to contribute over USD 360 billion to industrial productivity by 2030 [30]. In smart factories, AR headsets allow technicians to see step-by-step assembly guidance superimposed on machinery, reducing operational errors by up to 30% [31].

2.2.3. Commerce and Retail

In commercial environments, XR is revolutionizing how customers engage with products and brands. XR enables virtual try-on experiences for clothing, eyewear, or cosmetics, allowing consumers to visualize products in real time through their smartphones, HMDs, or AR mirrors. Major retailers such as IKEA and Nike have launched AR-based platforms like IKEA Place and Nike Fit, offering customers immersive and personalized shopping journeys. Meanwhile, VR showrooms provide realistic 3D product visualization for automobiles, furniture, or real estate properties, enabling potential buyers to explore digital replicas before making decisions [32].

2.2.4. Medicine and Healthcare

XR technologies are transforming the healthcare sector through surgical training, remote diagnosis, and rehabilitation. VR-based surgical simulators, such as Osso VR [33] and Fundamental XR [34], provide realistic, interactive 3D environments that allow students to practice complex procedures without physical risk. Studies have shown that such systems can significantly improve the effect of surgical training compared to traditional methods [35,36]. In AR-assisted surgery, real-time medical imaging and anatomical data are superimposed onto the patient’s body to guide surgeons during operations [37]. These applications all require ultra-low latency and high visual accuracy to ensure that overlays align precisely with the physical anatomy.

In addition, telemedicine and remote consultation through MR technologies enable doctors to collaborate with specialists across the world, sharing 3D patient models and vital signs in real time [38]. Rehabilitation programs using VR have also shown promise in treating neurological and motor disorders by providing adaptive, gamified environments for repetitive training [39].

2.2.5. Education

Compared with traditional classroom-based instruction, modern education, which is driven by rapid technological advancement, has evolved toward a more multi-scenario, multidimensional, and intelligent paradigm. The COVID-19 pandemic further acted as a catalyst, pushing online and hybrid learning models to unprecedented status and accelerating the integration of immersive and interactive technologies into mainstream education. According to MarketsandMarkets, the global XR education market is projected to reach USD 14.2 billion by 2028, with a CAGR exceeding 29.6% during the period 2023–2028 [40].

2.2.6. Simulation and Specialized Training

XR’s ability to reproduce realistic environments makes it invaluable for simulation-based training, particularly in defense [41], aviation, astronautics [42], and emergency response. Compared to traditional training methods, these immersive simulations have been shown to significantly reduce training costs and physical resource consumption while improving procedural accuracy [41,43].

2.2.7. Tourism and Cultural Heritage

XR is reshaping the tourism and cultural heritage sectors by enabling virtual exploration of destinations and historical sites [44]. VR tourism platforms, such as Ascape VR and YouVisit, allow users to explore global landmarks through immersive 360° tours, offering lifelike experiences without physical travel. Beyond virtual tourism and digital scene reconstruction, AR also enhances real-world travel experiences by offering personalized, context-aware information to visitors [45].

2.3. Requirements of Communication

2.3.1. User Experience Assurance

The user experience in XR applications is fundamentally determined by the degree to which the system can create, sustain, and synchronize immersive virtual environments that resemble and respond to the real world. Within the XR spectrum, different modalities exhibit distinct characteristics and consequently impose different levels of system requirements. While VR and MR aim to deliver fully immersive or deeply interactive virtual environments that require continuous rendering, spatial synchronization, and low latency feedback, AR typically overlays digital elements onto the physical world. As a result, AR applications demand relatively lower system performance in terms of bandwidth, computational power, and latency, since the user’s primary sensory input remains grounded in the real environment. Essentially, the quality of the immersive experience (MR and VR) is determined by three core attributes, which are immersion, interaction, and imagination (3I), where immersion describes the user’s perception of being completely surrounded by and engaged in a virtual or mixed environment, interaction reflects the degree of active involvement and control that users have within an XR environment, and imagination represents the creative and exploratory potential that XR technologies unlock. These aspects define how users perceive realism, respond to feedback, and emotionally engage with virtual content [46].

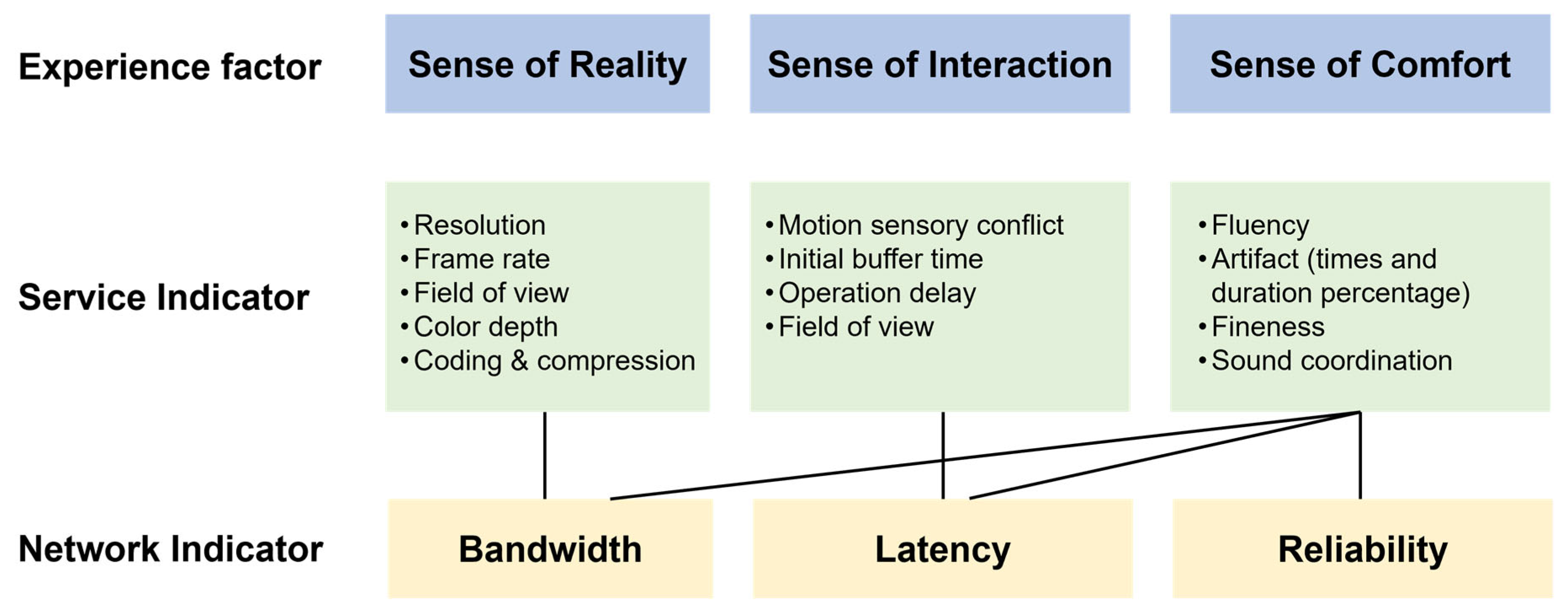

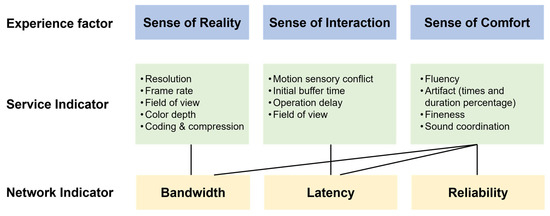

Correspondingly, the experiential dimensions of XR can be interpreted through three user-centered aspects: the sense of reality, the sense of interaction, and the sense of pleasure, as illustrated in Figure 3. The sense of reality in XR experiences largely stems from how convincingly the system can reproduce visual and auditory stimuli that align with human perception. This depends on factors such as display resolution, frame rate, color accuracy, and the efficiency of video compression. The illusion of presence will quickly collapse whereas the image quality deteriorates or temporal smoothness is lost, weakening user engagement. Therefore, maintaining visual fidelity requires communication links with sufficient bandwidth to sustain high definition, real-time content delivery. Secondly, the sense of interaction depends on how quickly and precisely the system responds to user inputs. In XR architectures, rendering and computation are partially or entirely offloaded to cloud or edge servers. This distributed processing makes network latency a key determinant of responsiveness. Even small transmission delays or jitter can cause mismatches between user motion and visual updates, resulting in discomfort or motion sickness. Finally, the sense of pleasure is relevant to the smoothness and stability of the entire XR session. Frame drops, image tearing, and synchronization errors disrupt the continuity of experience and reduce overall satisfaction. To ensure fluid and enjoyable immersion, the network must guarantee sufficient throughput, low latency, and stability under dynamic conditions.

Figure 3.

Network indicator relevant to XR experience factors.

Taken together, these perceptual factors demonstrate that user experience in XR is not merely dictated by content richness or hardware capability but is also tightly coupled with the performance reliability of the supporting communication network. The next section further examines the technical parameters that underpin these experiential dimensions and their implications for system design.

2.3.2. QoS Requirement

The performance of XR applications is fundamentally determined by the relationship between QoS at the network layer and QoE at the user level. QoS refers to the objective technical parameters of a communication system (such as bandwidth, latency, jitter, and packet loss rate), which represent how efficiently the network transmits data. QoE, on the other hand, reflects the user’s subjective perception of the service, encompassing immersion, interactivity, comfort, and visual realism [47]. Although QoE reflects the user’s sensory and psychological satisfaction, it is inherently constrained by the network’s ability to ensure smooth content delivery, visual clarity, and real-time responsiveness. In this sense, high QoS performance serves as the essential prerequisite for achieving satisfactory QoE in XR systems, as the consistency and fidelity of immersive experiences directly depend on the communication system’s technical capacity.

To achieve a high level of QoE in XR applications, network and system parameters must ultimately be aligned with human visual and perceptual characteristics. The human visual system is highly sensitive to spatial resolution, frame rate, color depth, and motion smoothness, all of which jointly determine the user’s sense of realism and comfort. The human visual system possesses a wide field of view (FoV) of about 210° horizontally and 135° vertically [48], and can distinguish approximately 60–200 pixels per degree (PPD) [49], implying that near-eye displays must reach several thousand pixels per eye to achieve retina-level fidelity. Vision can be divided into foveal and peripheral regions: the fovea provides high acuity and color sensitivity, while peripheral vision covers a wider angle with reduced detail perception. Commonly, the refresh rate of the human eye is regarded as 120 Hz [50]. For large movements, however, the human eye can move at speeds up to 30° per second, requiring display updates of about 1800 pixels per second for a 60 PPD HMD [51]. Moreover, it perceives contrast ratios up to 1:109 and over 10 million colors, necessitating at least 24-bit color depth for realistic reproduction [52]. Based on these perceptual characteristics, an ideal XR system should be designed to meet corresponding parameters shown in Table 1 to deliver a truly immersive experience.

Table 1.

Specification for an ideal XR device.

For ensuring visual fidelity and a high level of immersion, image parameters such as resolution, frame rate, and color depth must align with the characteristics of the human visual system, resulting in extremely high data transmission demands. According to previous studies, the bandwidth requirement in different phases of XR applications is exhibited in Table 2 [11]. As can be seen, the bandwidth requirement increases exponentially with improvements in immersion degree and QoE. When the XR media streams are transmitted without compression, even the Pre-XR phase demand data rates exceed 10 Gb/s, while ideal-level XR experiences may require several terabits per second, highlighting the extreme scale of data involved. This necessitates the use of highly efficient compression algorithms to minimize transmission load [53]. However, even with lossless or low-latency compression, achieving optimal visual quality and immersion still requires tens of gigabits per second of sustained throughput. This escalating bandwidth demand arises from the simultaneous transmission of high-resolution stereoscopic video and multi-view rendering data, far exceeding the capabilities of current Wi-Fi 6/7 and 5G networks.

Table 2.

Bandwidth requirements of XR in different phases [11].

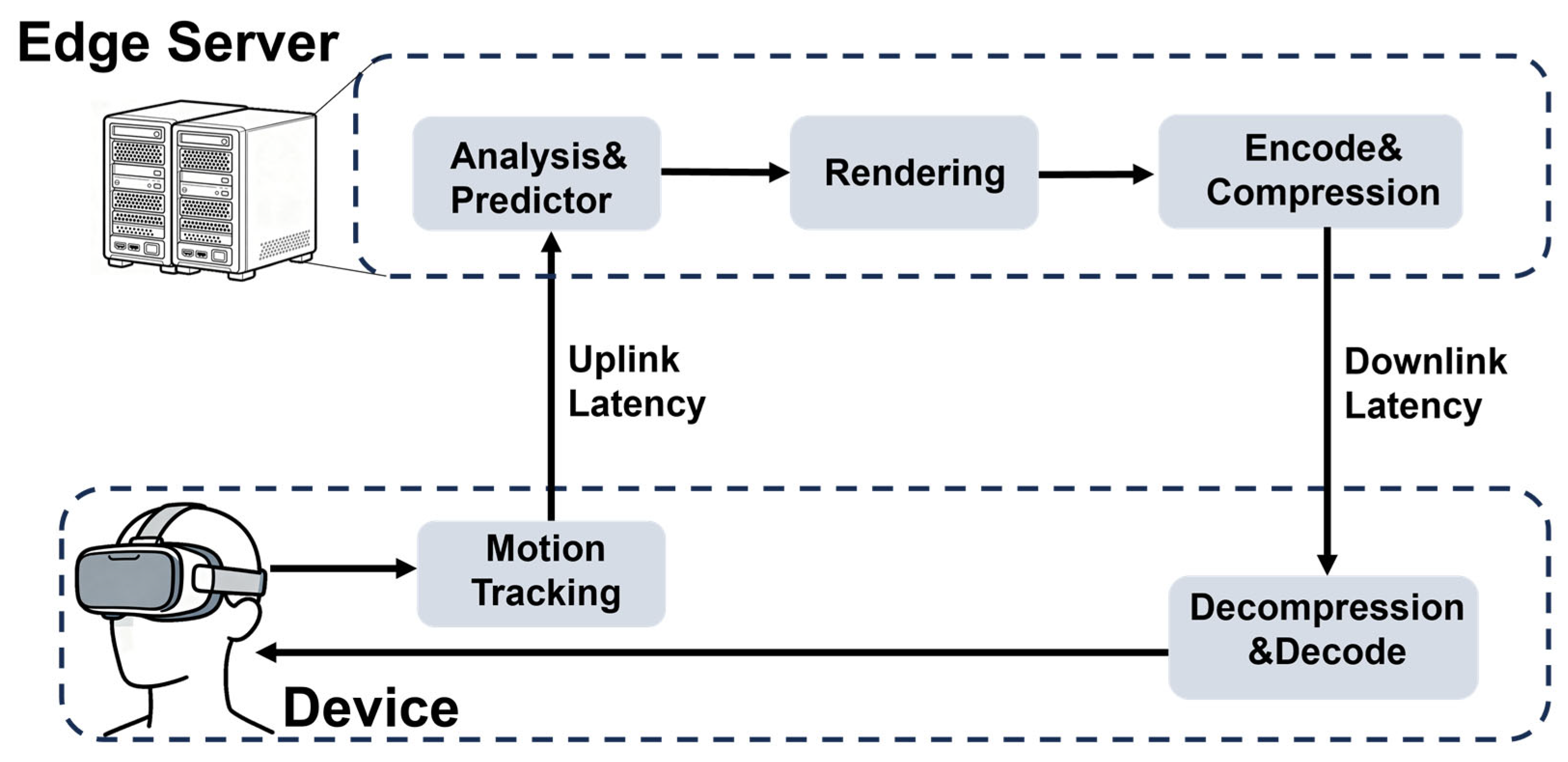

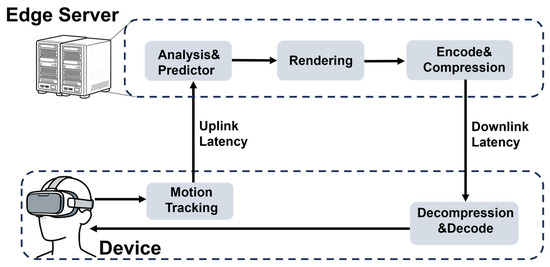

While bandwidth determines the richness and fidelity of XR content, latency plays an equally critical role in real-time interaction and preserving user comfort. In immersive environments, even slight delays between user actions and system responses can disrupt the sense of presence and cause motion sickness, dizziness, or visual–vestibular conflict [5,6,11,54]. For this reason, latency has become one of the most stringent QoS constraints in XR communication systems. In XR systems, due to the high computational demand of rendering and scene reconstruction, most processing tasks are offloaded to edge or cloud servers. As illustrated in Figure 4, when a user performs a movement, the system first captures motion and tracking data and then transmits this information to the server, where it is analyzed, rendered, and encoded. The processed video frame is then transmitted downstream to the XR headset, decoded, and finally displayed to the user [46]. The MTP latency therefore represents the total end-to-end delay across this entire processing chain (from motion capture to visual feedback), in which the network transmission latency remains one of its major contributing factors. As indicated in Table 3, the latency requirement is relatively moderate for noninteractive scenarios (such as 360° VR video), which should be kept below 20 milliseconds. For real-time interactive XR applications, however, the overall latency constraint is extremely stringent, which is of sub-8 milliseconds.

Figure 4.

End-to-end XR interaction latency.

Table 3.

Latency requirements for various cases [46].

In addition to bandwidth and latency, reliability is another crucial QoS parameter that directly affects the quality of XR experiences. Even minor packet loss or transmission errors can cause frame freezing, motion artifacts, or desynchronization between audio, video, and user interaction, leading to a noticeable degradation in QoE. For fully immersive systems, maintaining seamless visual flow and consistent feedback requires an end-to-end packet loss rate lower than 10−6 [55]. The reliability requirement is even more demanding in multi-user or collaborative XR scenarios, where synchronization between participants must be maintained with millisecond precision. Therefore, XR communication systems must ensure ultra-reliable data transmission with mechanisms for fast error recovery, multi-connectivity, and adaptive retransmission without introducing additional latency.

2.4. Challenges of Conventional Wireless Communication in XR Systems

Despite the rapid progress of traditional wireless technologies such as Wi-Fi and 5G, these systems still face significant limitations when supporting the stringent requirements of XR applications. The first major challenge lies in spectrum congestion and limited capacity. As XR demands continuous multi-gigabit data transmission for high-resolution rendering and multi-view video streaming, existing RF bands become easily saturated, especially in dense indoor environments where multiple devices compete for limited bandwidth [56,57].

Secondly, interference and signal instability remain critical bottlenecks. The shared nature of the RF spectrum leads to unpredictable channel quality variations [58,59], which cause frame drops and latency spikes—both detrimental to immersive experiences. Although high-frequency bands such as mmWave offer abundant spectrum resources, their practical deployment faces significant technical challenges. The generation and processing of high-frequency signals require significant power consumption, and the associated beamforming and beam-tracking operations are both computationally intensive and costly to implement [60].

Moreover, XR applications demand high-precision user tracking, including accurate estimation of head orientation, body posture, and spatial position, to ensure consistent rendering and stable perspective alignment in virtual environments [61,62]. Such precise motion awareness is essential for maintaining immersion and preventing visual–vestibular conflicts. However, achieving ultra-fine localization remains a formidable challenge for current RF-based wireless systems [63]. Conventional wireless systems suffer from multipath interference, limited spatial resolution, and inconsistent phase measurements, making them inadequate for continuous, fine-grained tracking in dynamic indoor settings.

These challenges collectively indicate that traditional RF-based wireless technologies are approaching their physical and architectural limits in sustaining next-generation XR communication. Therefore, it is necessary to explore complementary or alternative approaches such as VLC, which can provide higher data rates, lower interference, and enhanced spatial reuse to meet the growing performance demands of immersive applications.

3. Opportunities of VLC Systems

VLC utilizes the visible light spectrum (380–780 nm) for data transmission by modulating light emitting diodes (LEDs). This means that the communication access point (AP) can be integrated with existing lighting systems, leading to a comprehensive system of communication and illumination functions. Compared with traditional RF communication, VLC offers several intrinsic advantages, including vast unlicensed bandwidth, immunity to electromagnetic interference, low latency, and enhanced physical layer security [13,64,65]. Furthermore, the directional and confined nature of light propagation makes VLC particularly well suited for short-range, high-capacity indoor links, aligning closely with the operating environments of most XR systems. Recent advances in high-speed LED modulation [66], optical receivers [67], and hybrid VLC/RF architectures [68] have further improved VLC’s practical feasibility, enabling gigabit-level transmission rates and stable communication in dynamic scenarios. These unique properties make VLC an effective complement to RF technologies, providing a new way for constructing high-throughput, low-latency, and interference-free communication frameworks tailored for immersive XR experiences.

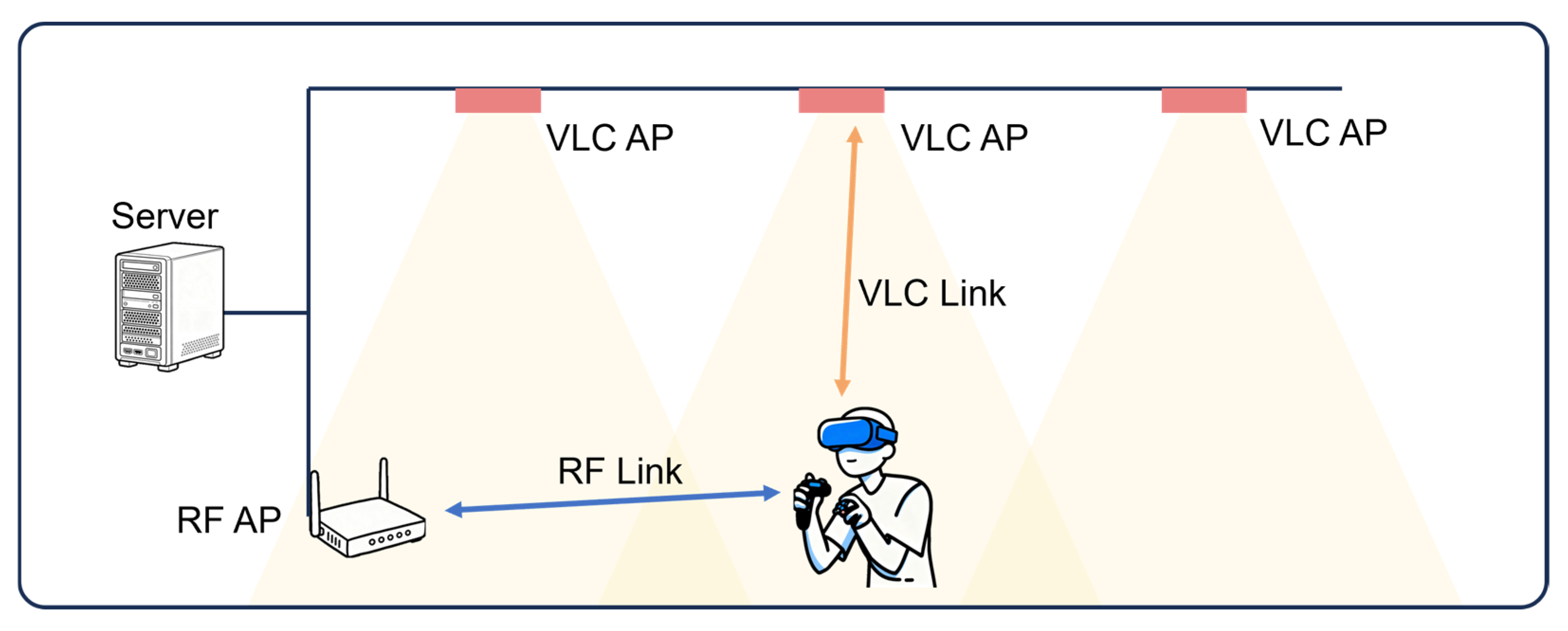

3.1. Overview of the VLC System

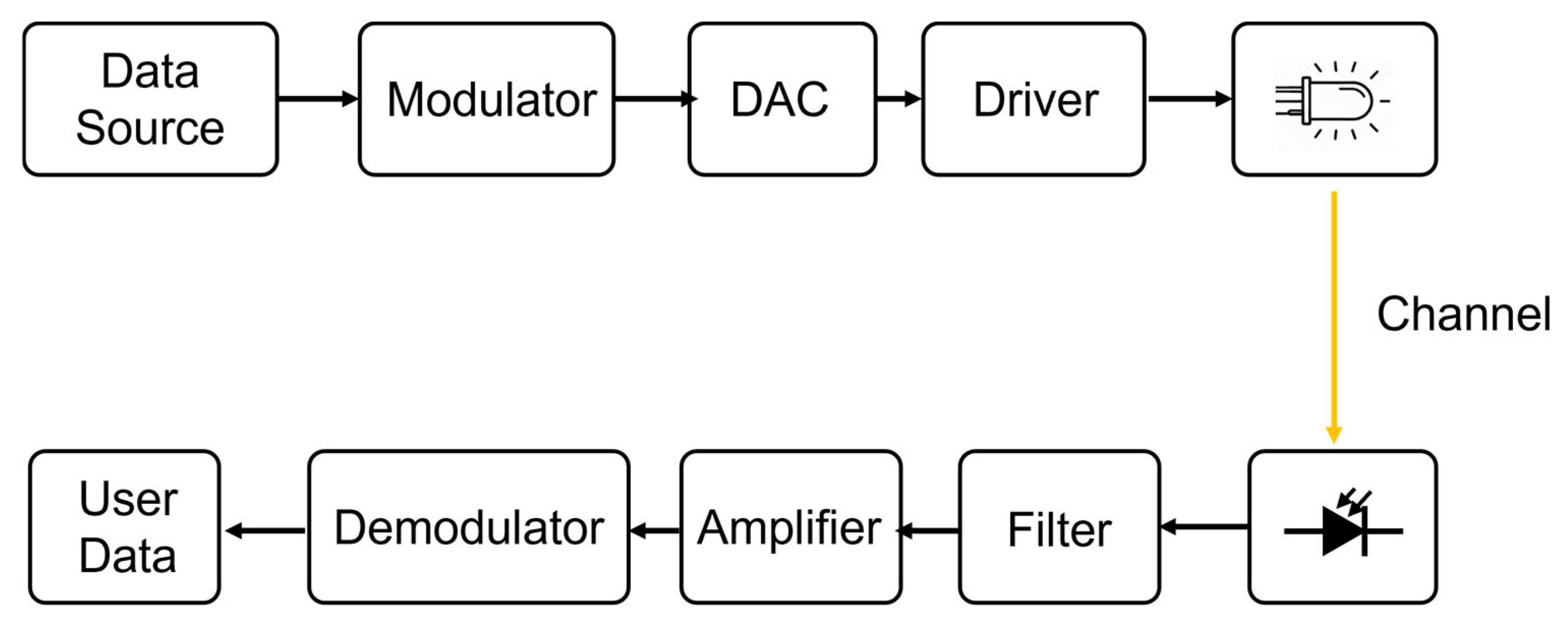

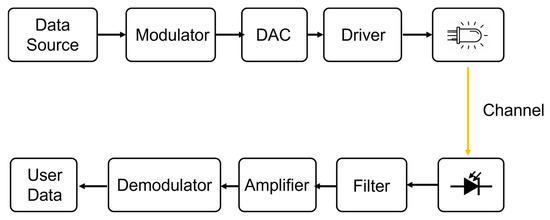

As a typical communication system, VLC contains both transmitters and receivers in the optical domain, where visible light serves as the carrier of information. In most implementations, LEDs are employed as transmitters due to their high energy efficiency, fast switching capability, and widespread deployment in illumination infrastructures. Data transmission is achieved by modulating the light intensity at rates imperceptible to the human eye, thereby embedding digital information into the emitted optical signal. During propagation, the optical signal may experience attenuation and distortion due to factors such as particle scattering, reflection from surrounding surfaces, and ambient light interference. To mitigate these effects, optical filters can be employed to extract the communication wavelength and suppress the unwanted signals [13]. At the receiver side, the photodiode (PD) or image sensor detects the incoming light and converts it into an electrical current proportional to the light intensity [69,70]. The resulting electrical signal is then amplified and demodulated to recover the transmitted data. The use of low-noise amplifiers and adaptive filtering circuits further enhances the robustness of the VLC link, reducing susceptibility to interference and improving overall signal quality. The architecture of a typical VLC is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Architecture of the VLC system.

VLC has gained in increasing attention from both academia and industry, prompting several standardization initiatives to ensure interoperability and promote large-scale deployment. Early efforts were led by the IEEE 802.15.7 standard [71], first published in 2011, which defined the physical (PHY) and medium access control (MAC) layers for short-range, low-data-rate optical wireless communication using visible light. This standard established fundamental concepts such as optical intensity modulation and direct detection (IM/DD), flicker, and dimming support, primarily targeting applications like indoor networking and vehicular communication. Building upon this, the IEEE 802.15.7 m task group later introduced extensions to support higher data rates, advanced modulation schemes, and multi-gigabit throughput, enabling more demanding use cases [72].

A significant milestone was reached with the release of IEEE 802.11bb [73] in 2023, which formally integrates light-based communication into the broader Wi-Fi framework, marking a significant milestone toward the convergence of optical and radio wireless systems. Unlike its predecessors, 802.11bb provides actionable insights for high-demand applications like XR through specific PHY and MAC layer enhancements:

- PHY Layer Enhancements for High Throughput: 802.11bb aligns its physical layer with the High-Efficiency (HE) and Very-High-Throughput (VHT) specifications of 802.11ax/ac. By supporting bandwidths up to 160 MHz and advanced OFDM schemes, it achieves multi-gigabit speeds (up to 9.6 Gbps). For XR, this provides the necessary pipe for uncompressed, ultra-low-latency 8K video streaming, effectively eliminating the MTP latency.

- MAC Layer and Coexistence: A key feature of 802.11bb is its seamless integration with the 802.11 MAC, allowing VLC to operate as a complementary band to RF. This enables the hybrid RF-VLC link, which can ensure the immersive experience for XR applications. The standard supports fast session transfer, ensuring that if the line-of-sight (LoS) VLC link is momentarily obstructed by user movement, the session can immediately failover to the RF band without dropping the immersive experience.

Furthermore, the standard’s emphasis on minimal hardware modifications—leveraging existing Wi-Fi baseband processors—significantly lowers the barrier for integrating VLC into commercial XR hardware. In addition to IEEE efforts, international organizations such as the ITU-T (under the G.9991 series) continue to promote the global harmonization of high-speed VLC systems [74]. The gradual maturation of these standards paves the way for integrating VLC into emerging high-performance applications, including immersive VR/XR systems that demand high data rates, low latency, and enhanced spatial security.

3.2. Properties of VLC

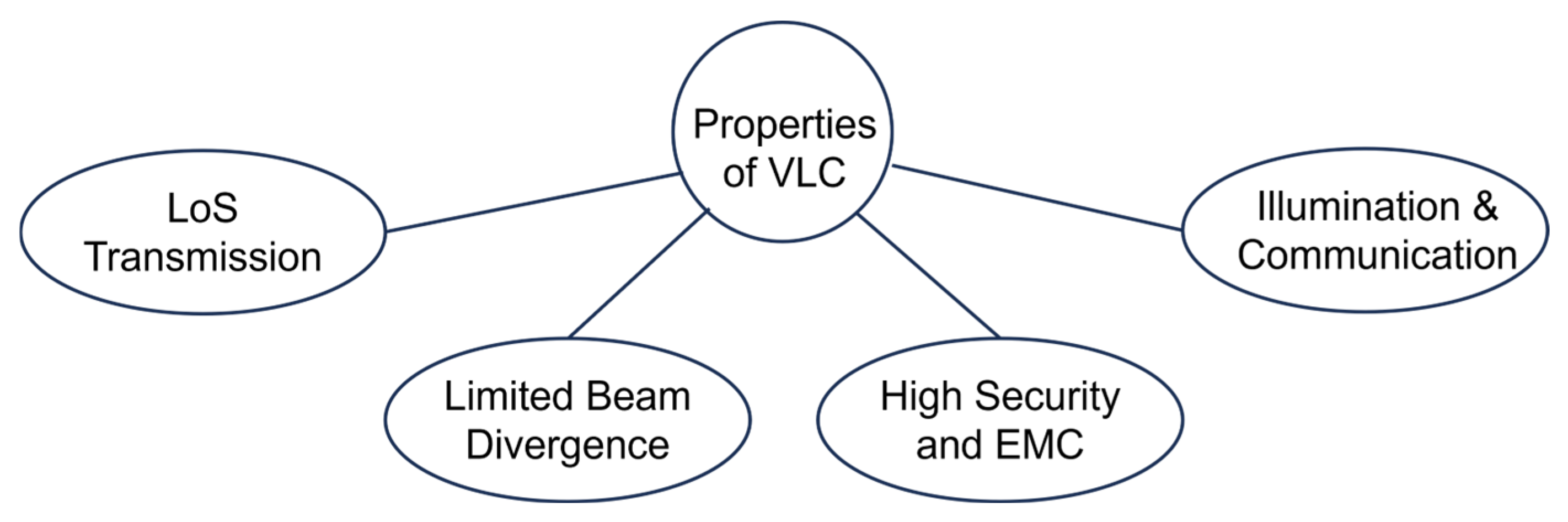

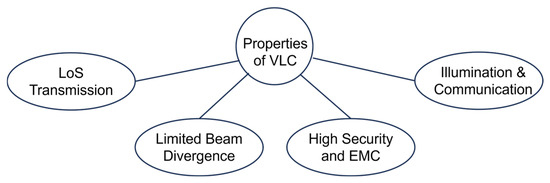

VLC represents a paradigm shift in wireless transmission, characterized by physical properties that distinguish it fundamentally from conventional RF systems. This section delineates the core attributes of VLC across four pivotal dimensions: propagation mechanisms, spatial geometry, security and compatibility, and functional integration, as shown in Figure 6. By leveraging the vast unlicensed visible spectrum, VLC offers unique advantages such as inherent physical-layer security through spatial confinement and the synergy between illumination and data transfer. These characteristics form the foundation of VLC’s potential to meet the stringent demands of XR environments while also introducing specific design constraints that necessitate specialized technical solutions.

Figure 6.

Properties of VLC system.

3.2.1. LoS Transmission

The performance of a VLC system is inherently influenced by its optical propagation characteristics and environmental factors. Unlike traditional radio systems, VLC relies on the LoS propagation of visible light, resulting in a highly confined communication region and high sensitivity to physical obstructions, reflective surfaces, and receiver orientation. In most VLC systems, data transmission primarily occurs under LoS conditions, where a direct optical path connects the LED transmitter and the photodiode receiver. This configuration ensures minimal signal distortion and the highest achievable data rate. However, in practical indoor scenarios, non-line-of-sight (NLoS) propagation arising from light reflections on walls, ceilings, or other surfaces can also be captured by the receiver. Although NLoS components significantly extend coverage and link robustness, they often exhibit weaker intensity and longer delay spread, potentially causing inter-symbol interference (ISI) [68]. To accurately characterize these effects, optical ray-tracing [75] and Lambertian reflection models [76] are commonly used to model multipath propagation and assess power distribution across the environment.

3.2.2. Limited Beam Divergence

The high directionality and limited beam divergence of optical signals make VLC channels inherently sensitive to spatial geometry and receiver alignment. Since visible light propagates primarily in straight lines, the communication link relies on maintaining a proper incidence angle between the transmitter and receiver. Even slight deviations in position or orientation can cause noticeable variations in received optical power, leading to degradation in signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) [14]. The confined nature of optical propagation enables dense spatial reuse and minimal inter-channel interference, but it also constrains the effective coverage area of a single transmitter. Consequently, achieving uniform illumination and stable connectivity across a larger indoor space often requires the coordinated deployment of multiple light sources or overlapping optical cells.

3.2.3. High Security and EMC

Because optical signals cannot penetrate opaque barriers such as walls or furniture, transmission is naturally confined within the illuminated area, effectively minimizing signal leakage and the risk of eavesdropping. This spatial confinement also eliminates cross-room interference, providing a more controlled and secure communication environment [77]. Such characteristics make VLC particularly suitable for sensitive or electromagnetically restricted environments, including hospitals, aircraft cabins, and industrial automation settings, where RF-based systems may cause interference with critical equipment. Furthermore, VLC operates in the unlicensed visible spectrum, which alleviates the growing congestion of radio frequency bands and enables massive reuse of optical channels in dense indoor deployments. Its ability to coexist seamlessly with existing RF systems allows for the creation of hybrid communication networks, where VLC handles high-capacity, short-range links while RF ensures mobility and wide-area coverage. This complementary relationship highlights VLC’s potential as a key component of future heterogeneous wireless architectures, especially in bandwidth-constrained indoor scenarios that demand both high data rate and strong security guarantees.

3.2.4. Duality of Illumination and Communication

A significant characteristic of VLC lies in its duality of illumination and communication. VLC transmitters typically act as conventional lighting fixtures while simultaneously modulating light intensity to transmit data. This dual-purpose design enables VLC systems to be easily deployed by leveraging the existing lighting infrastructure, providing a cost-effective and energy-efficient solution for indoor wireless access. The integration of communication into lighting networks not only reduces hardware redundancy but also supports ubiquitous connectivity in environments such as homes, offices, and shopping malls. However, this coexistence introduces design challenges, as the modulation used for data transmission must not degrade visual comfort or lighting performance. To achieve seamless operation, advanced techniques such as dimming control, flicker suppression, color rendering optimization, and adaptive brightness management are employed to ensure that illumination quality remains consistent while maintaining high data throughput [78].

3.3. Opportunities of VLC in XR

As noted previously, VLC offers intrinsic advantages such as unlicensed spectrum availability, large potential bandwidth, immunity to electromagnetic interference, and natural spatial confinement. These characteristics align remarkably well with the stringent requirements of XR communication, positioning VLC as a compelling enabler for next-generation immersive systems. While various challenges remain, the emerging XR landscape, which is characterized by ultra-high-resolution content delivery, ubiquitous motion interaction, and precise spatial awareness, creates unprecedented opportunities for VLC to evolve into a core component of future XR networks.

One advantage of VLC lies in its deterministic latency. Quantitatively, the PHY layer processing delay of VLC is typically under 1 ms, whereas Wi-Fi 6/7 involves contention-based MAC protocols that introduce over 10 ms of stochastic delay (jitter) in congested environments [79]. Furthermore, while 5G NR URLLC aims for 1 ms air-interface latency, the end-to-end MTP budget for XR (ideally <20 ms) benefits significantly from VLC’s ability to offload the downlink, reducing the total communication-induced latency by approximately 60–80% compared to current Wi-Fi solutions [80].

High-quality XR experiences rely heavily on the transmission of ultra-high-resolution 3D video streams at extreme frame rates. Such requirements translate into multi-gigabit-per-second throughputs per user, far surpassing the capabilities of conventional RF systems and calling for new physical-layer solutions capable of exploiting broader spectral resources [56]. VLC is uniquely positioned in this regard: by leveraging the vast, unregulated visible light spectrum, high-speed optical sources (such as micro-LEDs and advanced GaN emitters), and spectrally efficient modulation schemes, VLC can deliver the capacity headroom demanded by large-scale XR content streaming and real-time rendering [81,82,83]. Thus, XR’s escalating bandwidth requirements create a natural technological pull for VLC advancements.

Another opportunity stems from VLC’s high directionality and tight spatial resolution. Although optical links are sensitive to user orientation and mobility, these same properties enable highly localized, interference-free communication cells suitable for dense deployments and spatial multiplexing in XR applications. With continued progress in dynamic beam steering, adaptive alignment, and multi-source coordination, VLC systems can transform their directional nature from a limitation into a strength—supporting high-capacity, interference-controlled links for users who constantly move and interact within immersive environments [84,85,86,87,88,89]. Emerging technologies such as reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RISs) further expand this potential by enabling programmable optical propagation paths and robust link recovery in visually dynamic spaces [90,91].

Beyond communication, VLC’s inherent spatial determinism and fine-grained optical characteristics offer significant opportunities for sensing and positioning capabilities that are essential to high-fidelity XR experiences. Precise localization and posture tracking allow seamless alignment between virtual and physical spaces, ensuring consistent visual perspective, reduced motion distortion, and natural interaction. The ability of VLC to provide centimeter-level accuracy surpasses many conventional RF-based systems [18,92] and can further enable unified communication and sensing frameworks that support high-capacity communication, motion capture, gesture interpretation, and spatial mapping.

Overall, the rapid expansion of XR applications presents an exceptional opportunity for VLC to mature into a key enabler of immersive networking. The convergence of XR’s demanding performance requirements with the inherent strengths of VLC reveals a forward-looking pathway: with the development of advanced optical devices, robust link adaptation mechanisms, and communication-sensing integration, VLC can evolve from a promising concept to a powerful and practical solution for future XR systems.

4. Enabling Technologies for VLC-Based XR Systems

4.1. Technologies for Enhancing Capacity and Throughput

4.1.1. Advanced Optical Sources

In VLC systems, the LED plays an important role in fundamentally determining the achievable data rate, energy efficiency, and overall system performance. As previously mentioned, conventional phosphor-coated white LEDs show poor modulation bandwidth, which is not sufficient for high-speed XR stream transmission. To overcome this bottleneck, advanced LED technologies with enhanced electro-optical performance and high-speed modulation capabilities have become a primary research focus.

GaN-based LEDs have attracted significant attention owing to their wide direct bandgap, high radiative recombination efficiency, and superior carrier transport characteristics [93]. The short carrier lifetime and strong internal electric fields inherent in GaN-based quantum well structures enable rapid carrier recombination and photon emission, resulting in modulation bandwidths that can reach hundreds of megahertz—far beyond those of conventional phosphor-coated LEDs [82].

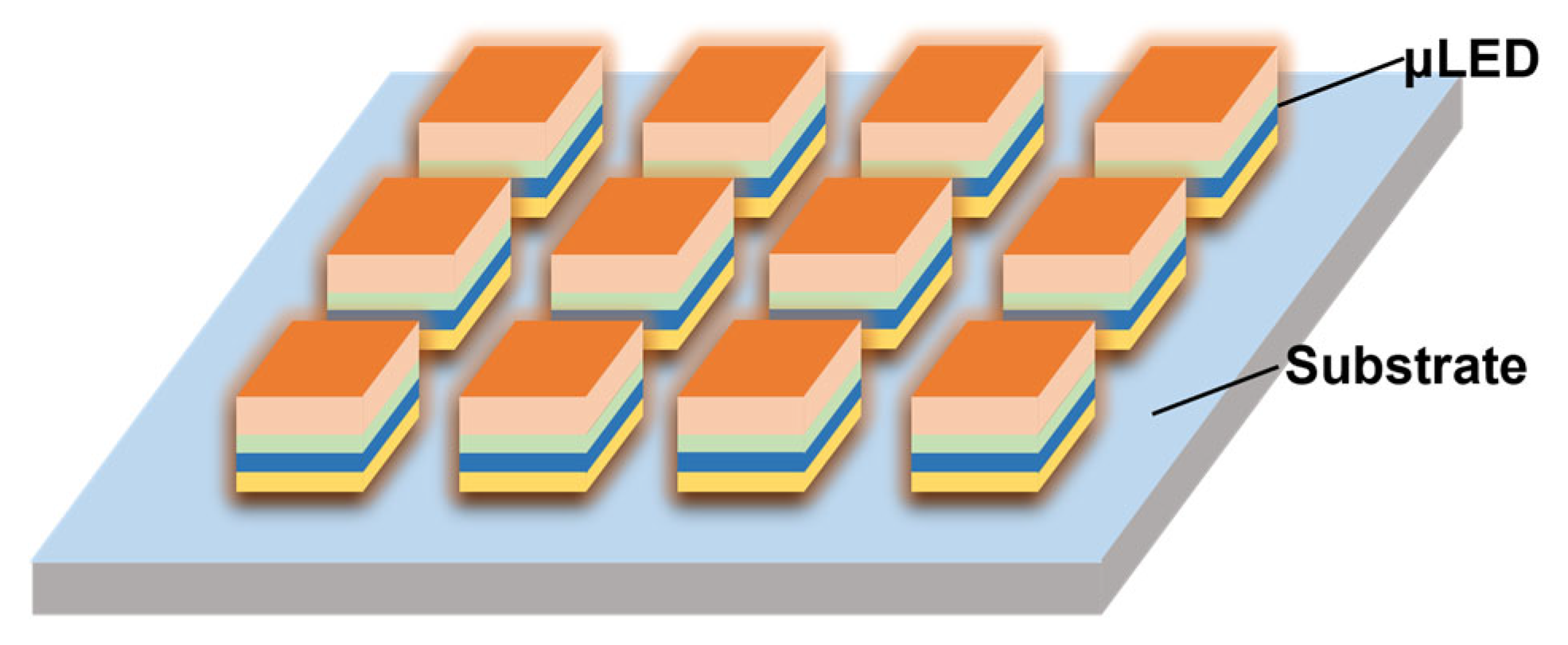

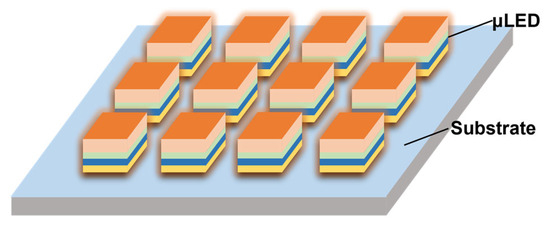

In terms of device structure, optimization of the component design is also crucial for enhancing the modulation bandwidth and optical efficiency of LEDs. Micro-LEDs (µLEDs) have been developed and consequently gained a lot of attention in VLC, owing to their ultra-small active areas and superior carrier dynamics. The reduced junction capacitance and short carrier lifetime in µLEDs enable rapid modulation of optical intensity [94], achieving bandwidths beyond 1 GHz [95]. By fabricating multiple µLEDs on a single substrate, the devices can reach very-high optical power and excellent energy efficiency under high current injection [96], making them ideal for high-speed transmission in short-range links, as shown in Figure 7. Recent experimental demonstrations have achieved data rates exceeding 10 Gbps per channel [17].

Figure 7.

Schematic of a µLED array consisted of multiple pixels.

Furthermore, multi-chip LED architectures combining multiple emitters offer parallel wavelength channels for hybrid illumination and communication. By selectively modulating different chips, multi-chip LEDs can support wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) within the visible band, significantly expanding the overall transmission capacity without sacrificing illumination quality [15,16].

The progress in LED resources has demonstrated significant improvements in modulation bandwidth and achievable data rates, as summarized in Table 4. These results validate the potential of VLC in bandwidth intensive XR applications.

Table 4.

VLC links utilizing various light sources, modulation format, and multiplexing scheme.

4.1.2. High-Efficiency Modulation and Coding

To meet the strict requirements of XR applications, efficient modulation and coding techniques are essential at the physical layer. As the LED relies on intensity modulation, the transmitted signal is restricted to real values, imposing unique design constraints on waveform generation and encoding.

In VLC systems, on–off keying (OOK) and pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) are the most fundamental modulation schemes, carrying data through light intensity variations. While they are simple to implement, the low spectral efficiency significantly limits their application for high-capacity systems [66]. To further improve the bandwidth efficiency, carrierless amplitude and phase (CAP) modulation has been widely adopted, which is conceptually related to quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM). CAP generates a real-valued optical waveform by combining two orthogonal pulse-shaping filters, thereby exploiting both in-phase and quadrature components of the signal without using carrier modulation. It offers higher spectral efficiency and resilience to channel distortions while maintaining moderate implementation complexity [101]. However, ISI becomes more pronounced at high data rates, requiring adaptive equalization with multiple taps at the receiver.

In scenarios with strong ISI or multipath reflections, multi carrier modulation techniques such as orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) and discrete multi-tone (DMT) modulation provide more effective solutions. By dividing the spectrum into orthogonal subcarriers and applying adaptive bit and power allocation, these schemes achieve high spectral efficiency and robustness against channel dispersion [100,103]. In addition, the use of constellation shaping such as geometrical shaping (GS) and probabilistic shaping (PS) would further improve the overall capacity [66]. While OFDM-based schemes offer high spectral efficiency, their high peak-to-average power ratio (PAPR) remains a significant bottleneck for VLC systems. In the context of compact XR HMDs, high PAPR drives the LED into its nonlinear transfer region, causing clipping distortion and increasing the EVM. This nonlinearity necessitates sophisticated pre-distortion or power back-off strategies, which in turn increases the hardware design complexity [17,96,97]. Therefore, there is a delicate trade-off between spectral efficiency and computational overhead. For instance, DCO-OFDM provides superior spectral efficiency but requires a high DC bias, leading to higher power consumption. Conversely, ACO-OFDM and PAM-DMT are more power-efficient but sacrifice half the spectral efficiency. For XR-class hardware with limited thermal and battery budgets, PAM-DMT often presents a more hardware-friendly alternative due to its lower complexity in real-time DSP implementation compared to complex-valued OFDM variants [104,105]. Ultimately, for XR-oriented VLC, the selection of modulation schemes must prioritize deterministic low latency and DSP efficiency over mere spectral gains to ensure compatibility with the limited computational resources of wearable terminals.

4.1.3. Multiplexing

Multiplexing technologies have been recognized as an effective method to improve the capacity of communication systems, including the VLC system. Wavelength division multiplexing enables simultaneous data transmission across multiple wavelength channels, efficiently utilizing the visible spectrum while maintaining illumination quality. Multi-chip LED structures allow independent modulation of each wavelength, achieving aggregate throughputs of several tens of Gbps [15].

In parallel, spatial multiplexing techniques such as multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) VLC use arrays of LEDs and photodiodes to transmit and receive multiple spatially separated data streams simultaneously [106]. Spatial diversity and beam steering can further enhance link robustness against shadowing or user movement, which are frequent in XR scenarios.

By combining wavelength and spatial multiplexing, VLC systems can achieve substantial gains in throughput, coverage, and link stability—establishing a scalable foundation for dense, high-capacity wireless networks that support immersive XR experiences.

4.2. Technologies for Latency Reduction

4.2.1. Edge-Assisted Computing and Rendering Offload

In XR systems, a substantial portion of the MTP delay originates from computationally intensive tasks, including motion tracking, scene rendering, and video encoding. Executing these operations locally on HMDs is constrained by limited processing power, thermal dissipation, and energy consumption, resulting in unsatisfying latency performance. To address this challenge, edge-assisted computing has emerged as a promising approach [107]. However, its effectiveness heavily relies on stable and high-bandwidth transmission of decoded and rendered data streams, which happens to be the inherent characteristic of VLC systems. By offloading rendering, encoding, and motion prediction tasks to nearby edge servers (deployed within indoor environments such as smart homes, offices, or industrial facilities), the computational load on user devices can be significantly reduced. This approach minimizes uplink and downlink distances compared to centralized cloud servers, thereby reducing round-trip latency to the millisecond scale [107,108].

Furthermore, cooperative edge architectures can coordinate multiple APs or light cells, allowing joint scheduling and predictive task migration to address user movement or link blockage. When integrated with VLC-based positioning and motion prediction, the edge server can anticipate user trajectories and pre-render the corresponding visual content, effectively reducing the rendering delay perceived by users [108,109]. In addition, the system responsiveness can be further enhanced by cross-layer optimization between the VLC physical layer and edge computing frameworks, utilizing strategies such as adaptive rate control and dynamic computational resource allocation. Supported by edge-assisted computing, the VLC-XR architectures will achieve high-quality immersive experiences with stringent real-time requirements.

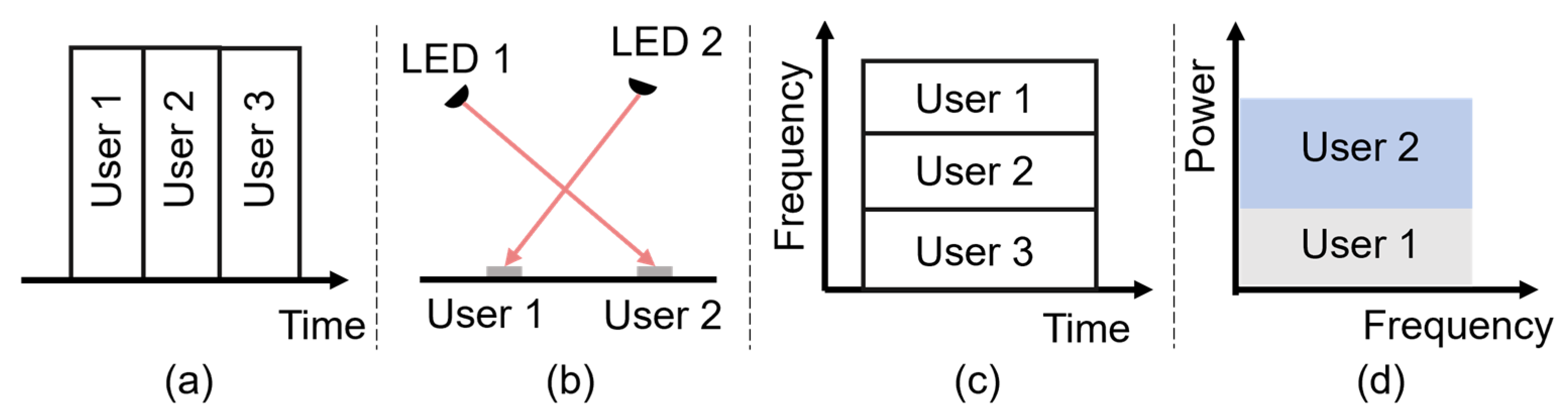

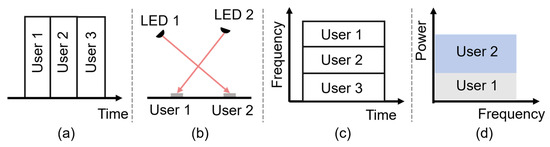

4.2.2. High-Efficiency Multiple Access

Efficient multiple access is essential for ensuring a low-latency experience for multiple users in XR applications. Unlike RF systems, VLC channels are characterized by strong spatial confinement and low inter-cell interference, which naturally supports high link reuse. Time division multiple access (TDMA) is one of the most common multiple access schemes that divides transmission time into distinct slots assigned to each user, as shown in Figure 8a. It is simple to implement via LED driving circuits and has been demonstrated as an effective approach to providing stable connections for multiple XR users [110]. However, the delay introduced by sequential access may limit its applicability for latency-sensitive XR scenarios requiring real-time updates.

Figure 8.

Multiple access schemes of VLC: (a) TDMA, (b) SDMA, (c) OFDMA, and (d) NOMA.

Leveraging the high spatial directionality of VLC, space division multiple access (SDMA) differentiates users by their physical position or angle within the illumination cell, as illustrated in Figure 8b. Each user can be served by an independent light beam, achieving spatial reuse and high aggregate throughput [20]. SDMA can be a promising scheme to support multiple XR terminals in the same space by dynamically steering beams toward user headsets, but maintaining alignment under user mobility remains a challenge.

Orthogonal frequency division multiple access (OFDMA) is an effective scheme that has been widely used in wireless communication [111]. It divides the spectrum into multiple orthogonal subcarriers, allowing simultaneous multi-user transmission with adaptive bit and power allocation [112]. It offers high spectral efficiency and robustness against multipath interference, making it suitable for high-density XR streaming. Yet, its digital signal processing complexity and high PAPR may increase system cost and energy consumption.

Different from other multiple access schemes, non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) enables multiple users to simultaneously share the same time and frequency resources by allocating distinct power levels to each user, as depicted in Figure 8d. On the receiver side, successive interference cancelation (SIC) is employed to sequentially decode and remove stronger signals, allowing weaker signals to be recovered effectively [13]. This power-domain multiplexing approach markedly improves spectral efficiency and user fairness [113], exhibiting potential in heterogeneous XR scenarios where users have varying SNRs, data rate demands, and spatial positions. For XR applications requiring simultaneous transmission of ultra-high-definition video streams and control feedback, NOMA provides an effective means of maximizing throughput under limited bandwidth resources. Nevertheless, the practical deployment of NOMA in VLC faces notable challenges, such as precise power allocation, nonlinear LED response, and low-latency SIC processing, all of which must be carefully optimized to maintain synchronization and ensure real-time interactivity essential for immersive XR experiences.

4.3. Technologies for Ensuring Stability and Mobility

4.3.1. Wide FoV Receiver

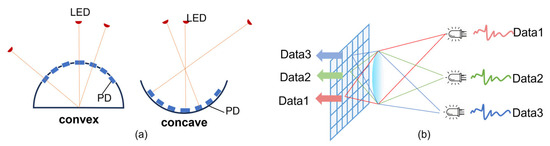

In XR-oriented VLC systems, receiver design plays a crucial role in maintaining reliable connectivity under dynamic user motion and frequent changes in orientation. Unlike conventional narrow FoV receivers, wide FoV receivers are specifically developed to support large-angle light collection and enhance spatial adaptability. These designs effectively mitigate signal degradation caused by body shadowing, head rotation, and temporary LOS interruptions, which are common in immersive XR interactions.

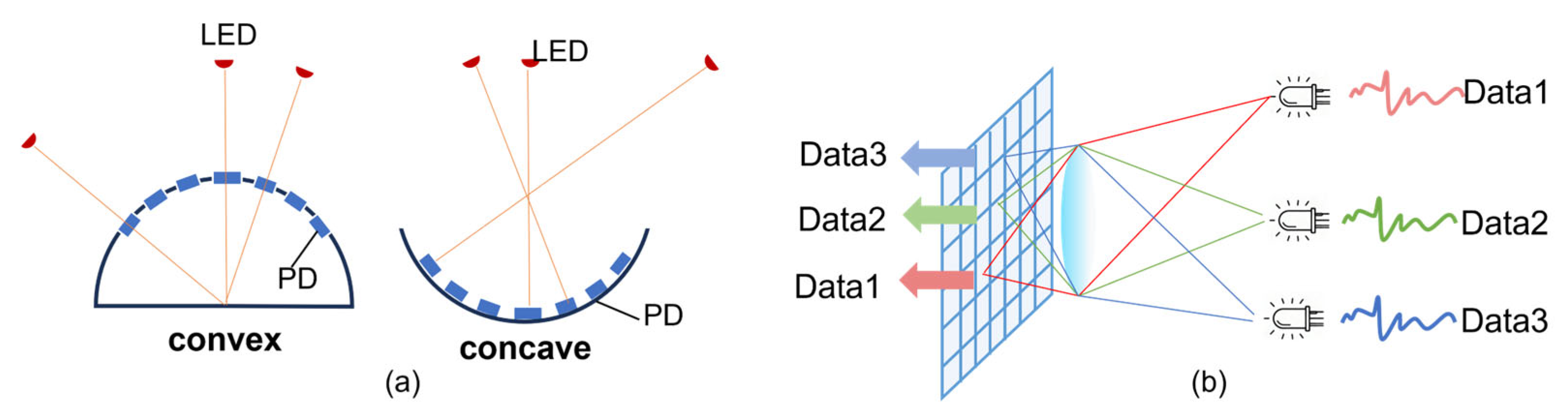

Angle diversity receivers (ADRs) employ multiple photodiodes with narrow yet complementary FoVs, oriented in different spatial directions to capture optical signals from various incident angles, as shown in Figure 9a. Each photodiode functions as an independent reception branch, enabling the system to select or combine the optimal signal based on instantaneous channel conditions. The signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR) can be improved by 20 dB–50 dB by using different combining strategies [114], such as selection combining (SC) [115], equal gain combining (EGC) [20], and maximal ratio combining (MRC) [116].

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of (a) angle diversity receivers and (b) imaging receivers.

In contrast, imaging receivers utilize optical lenses and pixelated detector arrays (e.g., CMOS or CCD sensors) to capture and spatially resolve incident light patterns across a wide angular range [117], as illustrated in Figure 9b. Although current imaging sensors are limited by relatively low modulation bandwidth, they still exhibit strong potential for future XR HMD and wearable terminals due to their inherent wide FoV and spatial resolution. To further enhance the robustness of such systems, liquid lens technology has been recently introduced as an adaptive optical component. Unlike static lenses, liquid lenses can dynamically adjust their focal length or steering angle via electrical control, effectively mitigating interference [118] and optimizing signal reception in MIMO VLC systems even under complex user mobility [119]. This adaptive capability significantly improves link reliability, making it a key enabling technology for maintaining stable connectivity in highly dynamic XR environments.

4.3.2. Dynamic Beam Steering and Link Adaptation

In VLC-based XR systems, maintaining stable connectivity is particularly challenging due to frequent user motion, body rotation, and dynamic head orientation inherent to immersive interaction. Because VLC links rely on LOS propagation with limited beam divergence, even small angular changes can result in significant signal fluctuations or temporary link blockage. To address this, dynamic beam steering has emerged as a key technique for ensuring robust optical link between transmitters and receivers.

The performance of these steering mechanisms is summarized in Table 5, highlighting the trade-offs between speed, range, and efficiency. Micro-electro-mechanical system (MEMS) mirrors are one of the most effective solutions for steering the beam in VLC systems [85,89]. MEMS mirrors offer high angular precision and sub-millisecond response times. However, they require careful mechanical calibration and are of high complexity, resulting in only moderate reliability and robustness. The second approach, liquid crystal (LC)-based beam deflectors, exploits electrically tunable refractive indices to achieve optical phase modulation [88,120]. While LC devices are compact and offer vibration-free operation with wider steering angles (up to ±40°), their response speed is typically slower (5–20 ms). Additionally, they suffer from optical efficiency penalties due to diffraction losses and polarization dependence, which can reduce overall signal intensity. Micro-LED arrays provide a solid-state beam steering alternative by selectively activating sub-arrays of emitters. This electronic switching allows for near-instantaneous response times (in the nanosecond range). Each pixel can serve as an independent light source, allowing for digital beam shaping and multi-user spatial multiplexing [16,87,89]. This enables dynamic adaptation of illumination zones according to user position, which is beneficial for multi-user XR environments. When integrated with real-time pose estimation data from HMDs, µLED arrays can achieve intelligent link adaptation through predictive spatial control. However, the optical efficiency of µLED arrays is often constrained by fill-factor losses and the pixel pitch of the array.

Table 5.

Performance of different steering mechanisms.

Since XR users often undergo rapid angular motion (ranging from 100°/s to 400°/s), the response time of the steering mechanism is critical for link stability. At a peak velocity of 400°/s, a steering delay of 20 ms (as seen in LC deflectors) would result in an angular lag of 8°, which could lead to a complete loss of the LOS path if the beam is narrow. Consequently, while MEMS and µLED switching provide sufficient speed to track real-time head movements, LC-based steerers may require advanced predictive algorithms to compensate for their intrinsic latency and maintain seamless connectivity during rapid physical interactions.

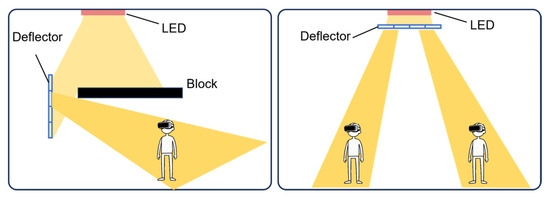

On the other hand, RISs have been gaining increasing attention recently for their potential to steer the beam beyond the LOS domain [86,88,90,91]. These programmable surfaces consist of tunable optical elements (such as MEMS and LC elements mentioned previously) that adjust reflection (or transmission) amplitude and phase, enabling controlled redirection of light toward shadowed or blocked areas, as presented in Figure 10. In XR environments where human body occlusion is frequent, RIS-assisted VLC can effectively reconstruct indirect optical paths and stabilize connectivity in NLOS conditions. Furthermore, RISs can cooperate with active beam steering to form hybrid adaptive systems, enhancing spatial coverage and maintaining high-quality links even in dynamic and cluttered indoor environments.

Figure 10.

Illustration diagrams of reflective and transmissive RISs.

4.3.3. VLC-RF Hybrid System

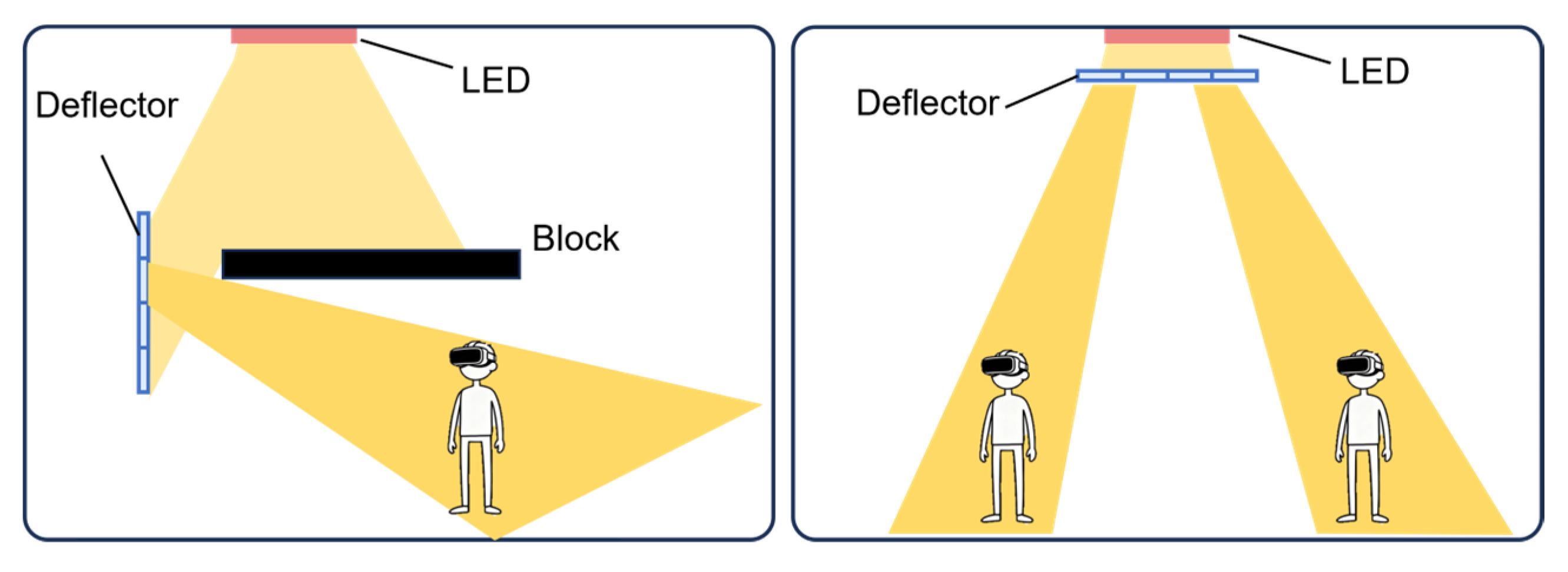

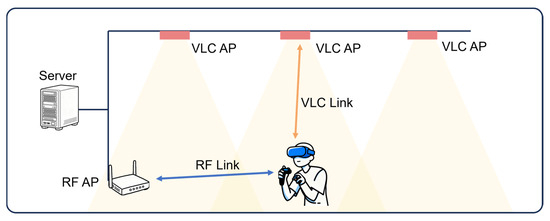

As previously mentioned, while VLC offers significant advantages, one of the challenges in practical VLC systems lies in the realization of a reliable uplink, as optical transmitters on user devices are constrained by power, size, eye safety regulations, and orientation variability. While downlink VLC transmission can be naturally supported by ceiling-mounted luminaires, establishing a symmetric optical uplink remains difficult, particularly in mobile and immersive XR scenarios. Furthermore, the VLC link usually suffers from NOS transmission and limited coverage. In comparison, RF systems exhibit high mobility, strong penetration, and wide-area coverage, although they suffer limited bandwidth and tight spectral resources. To provide a clear overview of the characteristics of VLC and RF links, a multidimensional comparison is presented in Table 6. Therefore, a natural thought is to integrate both schemes to achieve complementary advantages, on which numerous investigations have been conducted [121,122,123,124,125], as depicted in Figure 11.

Table 6.

Comparison of VLC and RF link [14,21,80,126].

Figure 11.

Complementary VLC and RF hybrid system.

By combining VLC and RF links, hybrid systems can significantly enhance system feasibility, overall link robustness, coverage continuity, and mobility support [119]. For instance, they can leverage VLC for high-capacity downlink transmission while utilizing RF links for uplink signaling and feedback. And when the VLC link is temporarily obstructed, data transmission can be instantaneously handed over to the RF link, ensuring uninterrupted communication and preserving user experience in high-dynamic applications such as XR. Considering the characteristics of uplink and downlink streams in XR applications, the VLC-RF hybrid interface allows for intelligent task partitioning—offloading high-throughput or delay-sensitive content such as stereoscopic video to the VLC downlink while delegating control signaling and uplink transmission to the RF domain.

Such hybrid architectures enable robust bidirectional communication, significantly improve link availability under blockage or misalignment, and reduce latency and packet loss through fast uplink control and retransmission mechanisms, achieving higher overall system throughput [124]. Furthermore, hybrid networking contributes to higher energy efficiency, as VLC transmitters leverage existing lighting infrastructure while RF modules operate in adaptive low-power modes under joint scheduling [116].

For a cross-domain coordination system, the handover strategies would significantly impact the overall performance of the data transmission. Several coordination strategies have been proposed to optimize hybrid VLC–RF networks, which would be discussed in the next portion. Consequently, VLC–RF hybrid systems provide a scalable and energy-aware solution capable of meeting the stringent demands of XR communication in terms of capacity, mobility, and reliability.

4.3.4. Handover

Given that VLC systems are characterized by limited AP coverage areas and rigorous LOS requirements, user movement inevitably triggers handovers between cells or networks, which can be classified as horizontal handover and vertical handover.

Within VLC systems, each transmitter typically defines an ultra-small cell with limited coverage determined by the LED’s divergence angle. As XR users move or change their orientation, they may frequently leave one illumination zone and enter another, requiring rapid intra-VLC handover to maintain link continuity. Unlike RF systems, where handover is primarily based on signal strength indicators, VLC handover depends heavily on geometric alignment, light intensity distribution, and receiver orientation [127]. Based on this, many handover strategies have been proposed, including received signal strength (RSS)-based handover [128], handover based on coordinated multipoint (CoMP) [129], and handover based on transmission performance [130]. These schemes can anticipate direction changes and proactively establish links with the next LED cell before the current link degrades. Additionally, techniques such as beam overlapping and adaptive illumination mapping can further minimize handover latency and maintain stable throughput in dense cell VLC networks.

In hybrid VLC–RF systems, another vital handover mechanism is vertical handover, which switches the traffic to the RF link when optical links are temporarily blocked or severely attenuated, thereby ensuring the reliability and robustness of the whole system. Conversely, when a stable optical path is re-established, data transmission can migrate back to the VLC link to exploit its high capacity and low latency advantages. Efficient vertical handover strategies rely on decision-making frameworks that jointly evaluate metrics such as received signal strength, link quality, and network load. Common strategies include Markov decision models [131,132], fuzzy logic approaches [133], hybrid metric-based schemes [134], and load-balancing strategies [135]. In addition, AI-driven algorithms and context-aware scheduling can further enhance decision accuracy by considering user trajectory prediction and service type [136]. Seamless integration of VLC and RF control planes, together with fast reconnection protocols, allows vertical handover to occur within a few milliseconds—sufficient to maintain uninterrupted XR experiences even under frequent mobility or partial occlusion.

4.4. Technologies for Positioning and Sensing

4.4.1. VLC-Based Positioning

Accurate user localization and motion tracking are fundamental requirements for immersive XR experiences, enabling spatial alignment, real-time rendering, and natural interaction between users and the virtual environment. Traditional positioning systems based on RF or vision sensors face limitations in XR indoor environments—RF-based methods often suffer from multipath interference and low spatial resolution, while camera-based tracking introduces privacy concerns and high computational overhead. In contrast, VLC systems naturally provide fine-grained spatial resolution and deterministic propagation characteristics, making them well suited for high-precision positioning and orientation tracking.

VLC positioning exploits the geometric and photometric properties of light to estimate user location. Common approaches include RSS-based methods [19,137], which infer distance from light intensity; time of arrival (TOA)- or time difference of arrival (TDOA)-based schemes [18], which rely on propagation delay measurements for centimeter-level accuracy; and angle of arrival (AOA)-based methods [18,138], which use photodiode or image sensor arrays to derive the direction of incident light. Hybrid models that combine multiple measurements (e.g., RSS + AOA + inertial data) can further enhance robustness against reflections or dynamic user movements.

In XR scenarios, VLC-based positioning enables not only the precise localization of HMDs or controllers but also fine-grained tracking of body orientation and movement trajectories. This facilitates accurate virtual-to-real alignment and consistent MTP synchronization. Moreover, VLC positioning can be jointly optimized with communication, using the same optical infrastructure for both data transmission and localization, thereby reducing hardware cost and improving system efficiency [14].

4.4.2. Gesture and Motion Sensing via VLC

Beyond high-precision positioning, VLC can also serve as an effective medium for motion sensing and gesture recognition—key enablers of intuitive human–computer interaction in XR systems. Unlike conventional camera-based approaches, which depend on high computational power and raise privacy concerns, VLC-based sensing leverages variations in optical intensity, reflection, and obstruction to infer user movements in a lightweight and privacy-preserving manner [92].

In principle, human gestures or body motions alter the propagation path and intensity distribution of visible light. By analyzing temporal or spatial fluctuations in the received optical signal, VLC receivers can detect and classify gestures such as hand waving, rotation, or tapping. Current VLC-based sensing techniques can be generally categorized into shadow-based [139,140,141] and reflection-based approaches [142,143,144]. In shadow-based sensing, user movement can partially block the light from LEDs, producing measurable variations in brightness or waveform patterns. These shadow-induced fluctuations can be analyzed to infer gesture type, motion speed, and spatial trajectory. In contrast, the reflection-based sensing scheme exploits the reflected or scattered light from the human body or surrounding surfaces. Subtle changes in reflection intensity or phase contain information about position and motion, enabling non-contact gesture detection even under NLOS conditions [92].

Although the shadow-based schemes deliver superior precision for detecting fine gestures and localized movements, their performance is highly dependent on LOS conditions and the dense deployment of light sensors [92]. In comparison, reflection-based techniques utilize the variations in reflected optical signals from human skin or surrounding objects, offering more robust operation in NLOS scenarios and greater adaptability to diverse environments [144]. By combining these two approaches, a hybrid sensing framework can be established that leverages the high precision of shadow-based detection with the generality and robustness of reflection-based sensing. Such integration holds great potential for achieving continuous, accurate, and context-aware perception in XR applications.

5. Perspective of Future Directions

5.1. Artificial Intelligent Enhanced VLC Systems

Artificial intelligence (AI) has recently attracted significant attention as a key enabler for the optimization and intelligent control of VLC networks. Existing studies have demonstrated its potential in signal processing, channel equalization, link optimization, mobility prediction, and load balancing [98,128,145]. However, for dynamic XR scenarios requiring high mobility, ultra-low latency, and stable connectivity, deeper integration of AI into VLC systems can further unlock their potential toward adaptive, context-aware, and self-optimizing networks.

One of the most promising applications of AI in VLC networks lies in intelligent network coordination and adaptive management, especially for heterogeneous architectures such as VLC-RF hybrid systems. Learning-based frameworks, such as reinforcement learning [146] and graph neural networks [147,148,149], can efficiently capture dynamic link variations, user mobility patterns, and network topology. By exploiting historical observations and real-time context, AI models can predict link quality evolution, user orientation changes, and blockage events, enabling proactive rather than reactive network control. More specifically, AI-driven decision engines can dynamically balance traffic between optical and RF domains, select the most appropriate uplink and downlink paths, and optimize handover timing to minimize service interruption. This capability is particularly important for XR applications, where strict latency constraints and continuous bidirectional interaction must be maintained under rapid user movement. Moreover, AI-based coordination allows joint optimization of spectrum utilization, transmission power, and scheduling across heterogeneous links, improving both reliability and spectral efficiency compared with rule-based approaches. By embedding intelligence into network management and control planes, hybrid VLC–RF systems can evolve toward self-optimizing and context-aware architectures, making them highly attractive for supporting immersive and large-scale XR communication environments.

Beyond network management, AI also offers powerful tools for enhancing optical environment control in VLC systems. By integrating AI with RISs, the propagation of visible light can be dynamically shaped to overcome line-of-sight limitations and optimize spatial coverage. Machine learning algorithms can analyze environmental geometry and user trajectories to adaptively configure surface elements for optimal reflection, refraction, or beam focusing [91]. Meanwhile, AI-assisted optical modeling, including physics-informed neural networks and differentiable ray-tracing methods, can accurately approximate light propagation and predict channel states in complex indoor environments at low computational cost. The combination of intelligent surfaces and AI-based light field modeling enables a self-adaptive VLC environment capable of maintaining robust, low-latency communication for dynamic XR users.

In addition, AI offers new possibilities for semantic and perceptually aware communication [150], where visual and contextual information is selectively transmitted based on user perception or gaze direction. This paradigm can drastically reduce bandwidth requirements while maintaining immersive fidelity.

In summary, the integration of AI into VLC systems can transform them from static optical links into adaptive and predictive communication networks. By combining perception, learning, and control, AI-driven VLC has the potential to become a key enabler for next-generation XR applications, achieving intelligent coordination across communication, sensing, and interaction domains.

5.2. Multi-Element Cooperative VLC

Advanced cooperative transmission frameworks have been validated as highly effective in enhancing network QoS [151,152]. These architectures deploy multiple spatially distributed transmitters and receivers such as LED arrays, dense small cells, or image sensor-based receivers, enabling coordinated transmission and reception across a shared optical domain. This cooperative structure not only enhances throughput through spatial multiplexing but also mitigates the effects of user mobility, orientation change, and shadowing.

Recent developments have extended this concept toward cell-free and distributed MIMO (D-MIMO) architectures, in which a large number of VLC access points jointly serve all users without strict cell boundaries [153]. This decentralized design allows for joint transmission, coordinated beamforming, and dynamic load balancing, significantly improving coverage uniformity and link robustness—critical for XR users moving freely within confined indoor spaces. Additionally, such systems enable seamless signal combination at the receiver through coherent combining or maximum ratio fusion, thereby reducing packet loss and enhancing link stability.

At the system level, efficient channel estimation, synchronization, and interference coordination are key to realizing the potential of these cooperative frameworks. AI-assisted resource allocation and clustering algorithms further optimize AP cooperation and user association in real time. Overall, multi-element cooperative VLC systems will provide a scalable, high-capacity, and resilient communication foundation tailored for the future XR environments.

5.3. Sensing–Communication Integrated VLC

There is a growing consensus that ISAC will play an important role in next-generation communication systems, aiming to unify data transmission and environmental perception within a single physical framework [154,155,156,157,158,159]. In the context of VLC, this paradigm is particularly promising due to the inherent spatial resolution and directionality of optical signals.