Abstract

The rapid evolution of smart transportation systems necessitates the integration of advanced sensing technologies capable of supporting the real-time, reliable, and cost-effective monitoring of road infrastructure. Fiber-optic sensor (FOS) technologies, given their high sensitivity, immunity to electromagnetic interference, and suitability for harsh environments, have emerged as promising tools for enabling intelligent transportation infrastructure. This review critically examines the current landscape of classical mechanical and electrical sensor realization in monitoring solutions. Focus is also given to fiber-optic-sensor-based solutions for smart road applications, encompassing both well-established techniques such as Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors and distributed sensing systems, as well as emerging hybrid sensor networks. The article examines the most topical physical parameters that can be measured by FOSs in road infrastructure monitoring to support traffic monitoring, structural health assessment, weigh-in-motion (WIM) system development, pavement condition evaluation, and vehicle classification. In addition, strategies for FOS integration with digital twins, machine learning, artificial intelligence, quantum sensing, and Internet of Things (IoT) platforms are analyzed to highlight their potential for data-driven infrastructure management. Limitations related to deployment, scalability, long-term reliability, and standardization are also discussed. The review concludes by identifying key technological gaps and proposing future research directions to accelerate the adoption of FOS technologies in next-generation road transportation systems.

1. Introduction—Classical Mechanical and Electrical Sensor Realization in Monitoring

The current monitoring systems instrumented for road and pavement condition utilize various sensor technologies to measure the strain, stress, deflection, vibration, and temperature of asphalt layers. Classical road and pavement monitoring systems implement electronic sensors, which can be surface-mounted as well as being embedded into the road or pavement. These sensors are used to provide the road infrastructure entities with real-time or periodic data that the engineers can use to assess the overall condition, extent, and type of damage, as well as the remaining life cycle of the road or pavement, and schedule its maintenance. Some of the major types of electrical sensors used for road and pavement monitoring are outlined in the following subsections [1].

1.1. Resistive Strain Gauges

Resistive foil strain gauges are among the most widely used embedded sensors for structural condition monitoring of road pavements. These sensors enable deformation measurement of different layers of the pavement. The gauges are often placed near the bottom or base layers in the pavement to measure longitudinal or transverse strain induced in the pavement by moving traffic [1,2].

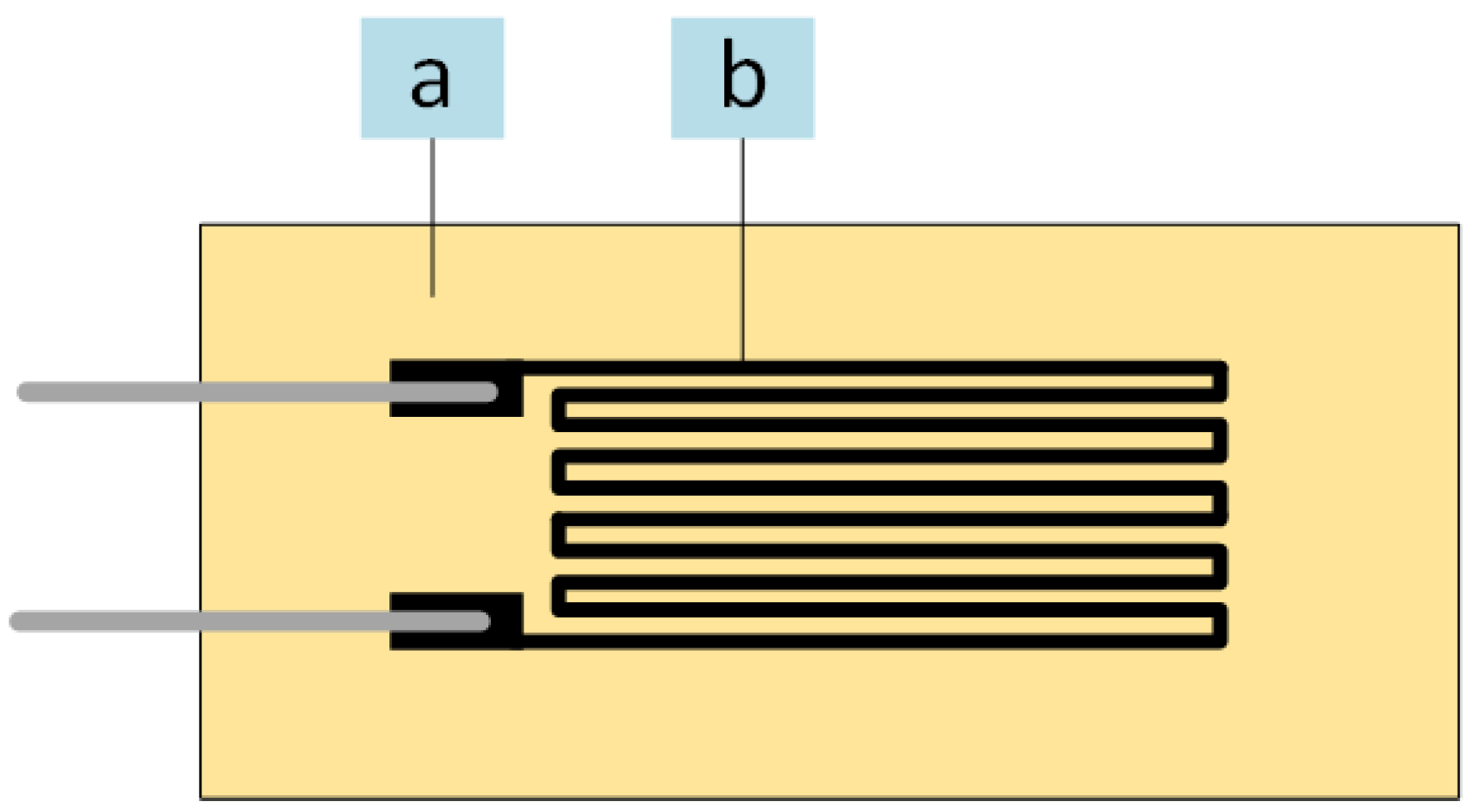

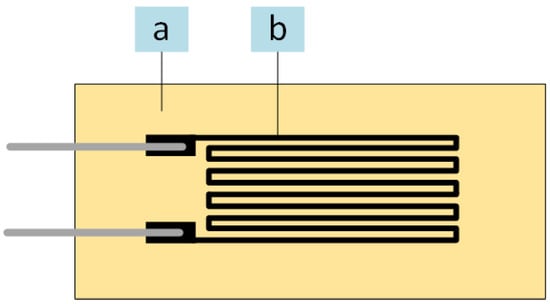

The gauge is manufactured as a metallic resistive grid, visible in Figure 1; it is usually made using Constantan, which enhances the sensitivity of the sensor. The resistive grid is bound to the thin-film substrate, allowing it to maintain its geometrical shape and arrangement; furthermore, it helps maintain insulation and protect against the environmental temperature’s influence [1,3].

Figure 1.

Resistive foil strain gauge: (a) thin film substrate; (b) resistive grid.

The strain is transferred from the pavement to the sensor’s resistive grid. The resistance of the resistive grid changes due to mechanical deformation. The change in the material’s resistance relies on the strain-resistance effect, which describes resistance to be dependent on the material’s geometry (length and cross-sectional area). When the tensile strain is applied to the gauge, its length increases, but its cross-section decreases, thus leading to an increase in resistance. When compressive strain is applied, the gauge’s length decreases, and the cross-sectional area increases, leading to a decrease in resistance. For elastic strain, the change in resistance should be approximately proportional to the applied strain. This linear ratio is described by the gauge factor (GF), which is defined as the relative resistance change per unit of strain [3,4].

A resistive strain gauge can be manufactured in different ways and configurations to meet its intended application requirements, and it is widely used in monitoring solutions for civil infrastructure. Usually, resistive strain gauges can be glued to the smooth surface of concrete, steel, etc., to monitor structural elements of the civil infrastructure and measure deformations. However, in the instance of asphalt pavements, it needs to be concealed in a protective structure to prevent the strain gauge from being damaged in harsh construction conditions. Furthermore, the bonding between the resistive strain patch and pavement layers is poor. Therefore, the packaging of the resistive strain gauge is highly important for the effective performance and robustness of the sensor [4,5].

Resistive strain gauges can measure strain with a typical resolution of around 1–5 µε, sensitivity up to ±1 µε, and accuracy of 0.03 to 1% [6,7]; they are a relatively simple and cost-effective approach for monitoring solutions of the road infrastructure and fatigue analysis of the pavement. Furthermore, they do not require the complex and often-costly interrogation units needed for fiber-optical sensors (FOSs). They are also more robust for the installation process; FOSs can be fragile and become damaged during installation [1,8].

To ensure sensor protection and accurate data acquisition, they are encapsulated in specific “smart” packaging materials. Considering that the elastic moduli of asphalt mixture layers may be 0.95–25 GPa, it is important to achieve the modulus of the embedding material close to these values, depending on the site of constriction. Such a modulus may be achieved by selecting appropriate materials with similar modulus values, considering that they are resistant enough to asphalt-laying conditions (temperatures, compression forces, and bituminous organic media, represented by SARA fractions). Suitable examples for such embedding materials are epoxy-based resins reinforced with rigid inorganic fillers. Moreover, for technically viable in situ embedding applications, it is also important that the curing of the embedding composite material is fast enough, with limited post-curing effects.

Earlier investigations have established benchmark stiffness values for the concrete used in airport pavement systems. The values reported for the elastic modulus of concrete generally fall within the range of 27–48 GPa [9,10], while flexural elastic modulus values have been measured to be between 33.76 and 45.74 GPa [11]. In addition, representative modulus profiles for composite pavements consisting of asphalt overlays on Portland cement concrete indicate that concrete slabs typically exhibit elastic moduli in the range of 74.5–100 GPa [12,13,14,15,16], whereas asphalt mixture layers show significantly lower values, approximately 0.95–25 GPa [12,13,14,15,16,17]. These stiffness characteristics demonstrate that fluoropolymer materials such as PTFE, FEP, and ETFE are suitable candidates for encapsulating Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors.

For strain measurement, the accuracy of the resistive strain gauge is comparable to that of the FBG and distributed fiber-optical sensors (DFOSs). However, for repeated loading and unloading of the sensor, the resistive strain gauge can exhibit higher strain deviation (between the measured and actual strain) and local strain shifts (local shift in the strain gauge’s resistance) due to the mechanical fatigue of the gauge and the adhesive (debonding between the grid and substrate micro-cracks) [18]. Furthermore, the resistive strain gauge offers lower sensitivity and resolution for strain measurements than FOSs. Resistive sensors have low signal power and are heavily affected by noise and electromagnetic interference; therefore, sensors and cables need to be shielded and can suffer from baseline drift due to the ambient temperature’s influence or creep. Resistive strain sensors are point sensors and can only measure deformations in discrete locations; meanwhile, FOSs can be multiplexed relatively easily into one sensor network, which facilitates distributed strain measurement at long distances and different layers with minimal cabling. A resistive strain gauge requires a separate channel for each sensor to connect to the data logger, as well as the power supply [1,2].

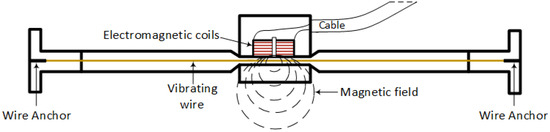

1.2. Vibrating Wire Strain Gauge

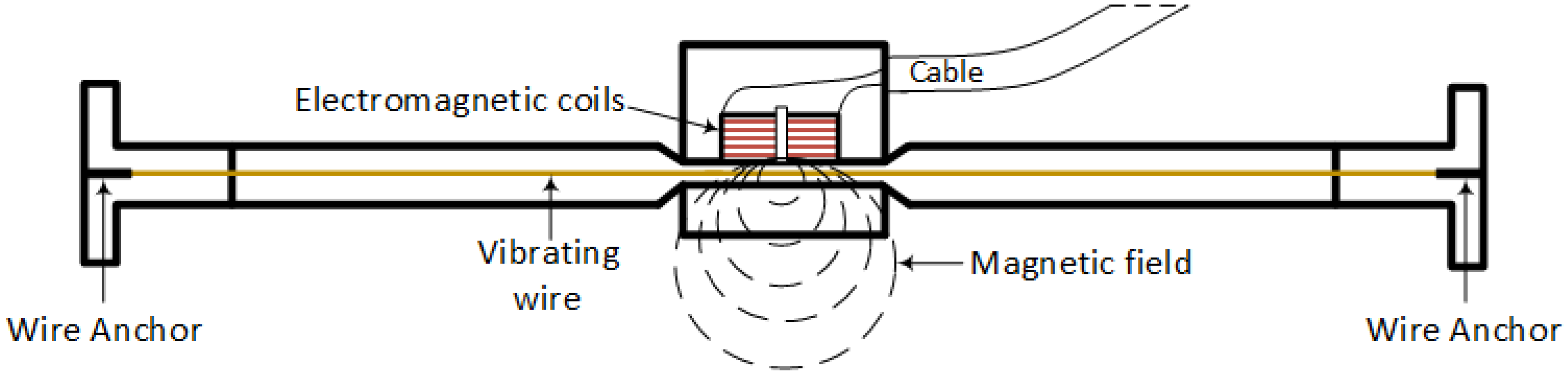

Vibrating wire sensors are widely utilized for the strain measurements of civil infrastructure and can be employed for road pavement monitoring [19,20]. A vibrating wire (VW) strain gauge is constructed from a thin steel wire that is anchored between two blocks, as seen in Figure 2. The steel wire is excited by an electromagnetic coil; if no strain is applied, then the wire will vibrate at its natural resonant frequency. When the pavement that is measured deforms, the transferred strain causes the distance between the anchors to change; thus, the tension of the steel wire is altered. This causes the wire’s resonant frequency to change with the applied strain to the gauge. A coil with a magnet is utilized to vibrate the wire briefly and then to pick up the induced voltage as the wire vibrates. The measured frequency is converted to strain considering the calibration constant [19].

Figure 2.

Schematic of a vibrating wire strain gauge.

The sensor output is frequency-dependent, unlike in the instance of the resistive strain gauge; therefore, VW sensors are immune to the resistance changes and electronic noise. Furthermore, the output signal of the sensor can be transmitted over relatively long distances, which offers advantages in the field deployment of such sensors. For temperature compensation, the VW sensor device usually includes a thermistor, which compensates for the temperature influence [20,21].

The VW sensor offers high sensitivity with high resolution of ±1 µε and can perform well for long periods of time with minimal signal degradation. The robustness of VW sensors is attributed to their design and materials being used for the sensor and the housing, enabling a reliable long-term strain measurement [21,22].

The drawback of VW sensors is the time delay introduced by the excitation of the steel wire and measuring its oscillation frequency, which can cause a high-speed deformation event not to be fully captured; therefore, it is not applicable to measure dynamic traffic loads unlike FOSs (FBG- or Rayleigh-scattering-based DFOSs), which excel at measuring dynamic strain events, as well as vibrations induced by traffic. So, VW is often used to measure static loads of pavement. VW sensors are significantly larger than FOSs or resistive gauge sensors, which can cause stiffness mismatch in the asphalt [20,21]. Furthermore, since VW strain gauges are point sensors, only localized strains can be measured, as VW strain gauges do not support an inherent multiplexing like FOSs do; the deployment of quasi-distributed or distributed strain sensing limits their utilization at the network scale [23].

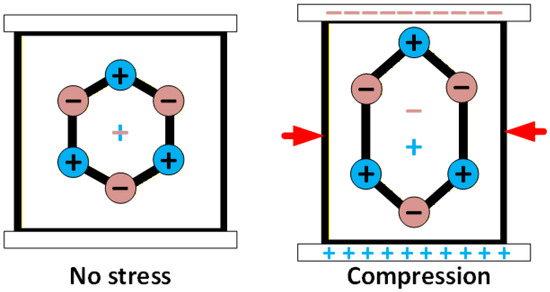

1.3. Piezoelectric Transducer Sensors

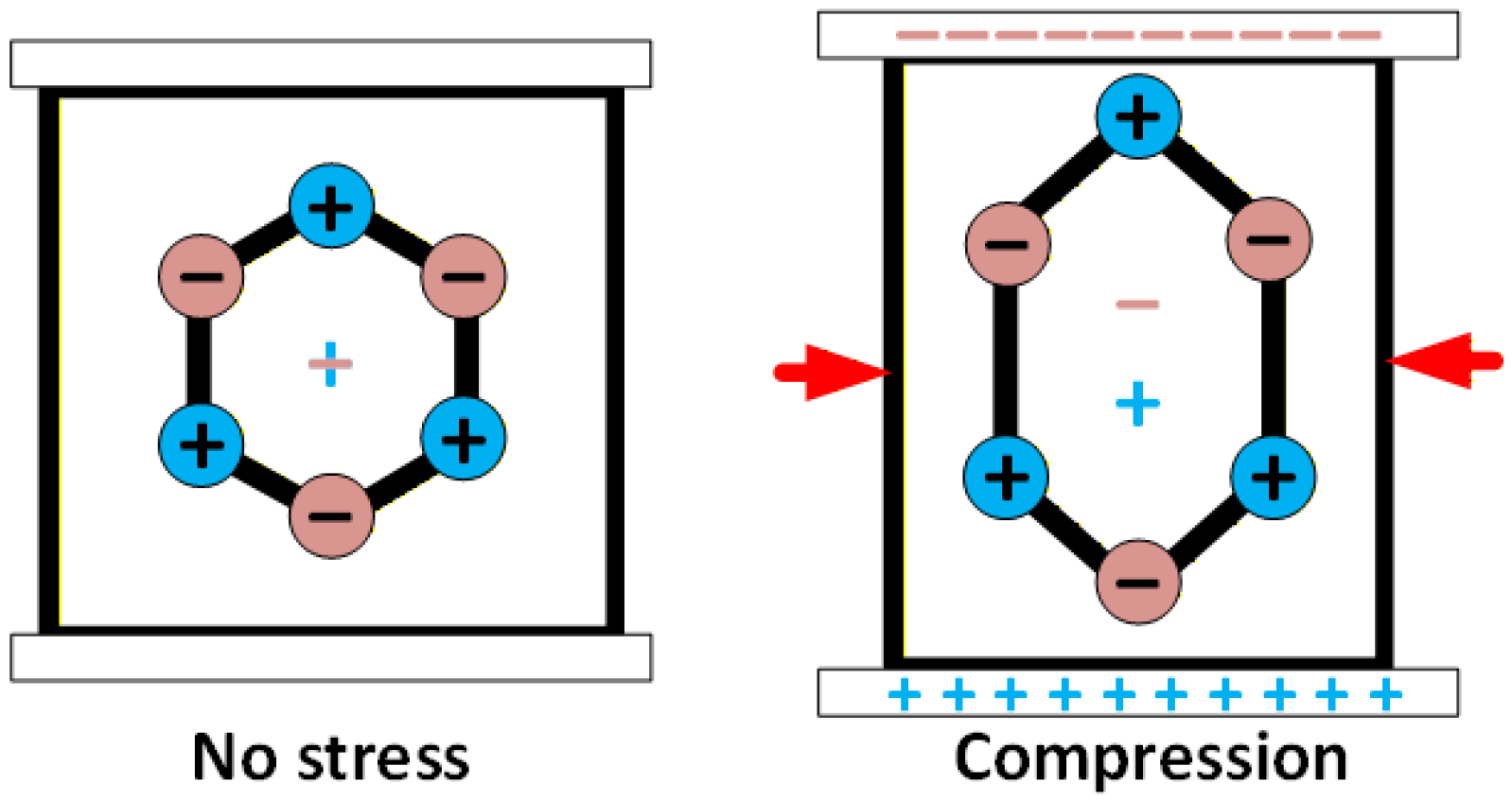

Piezoelectrical transducer (PZT) sensors are an attractive technology because the piezoelectric element itself is passive and does not require power to operate, which has advantages in field deployment. PZT sensors generate an electrical signal when they are deformed; this phenomenon is called the piezoelectric effect. When a piezoelectric material is deformed, the balance of positive and negative charged atoms is disrupted, and net positive and negative charges are generated on the opposite sides of the material, as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Operating principle of PZT.

PZT sensors are often produced from ceramics, such as lead zirconate titanate or barium titanate, or polymers, such as polyvinylidene fluoride. A PZT produces an electric charge that is proportional to the applied strain; therefore, it can be used as a strain gauge and is often used in weigh-in-motion (WIM) systems [1,19,24].

PZT sensors can be employed for short-term and long-term monitoring. An example of short-term monitoring is the WIM system. For long-term monitoring, dynamic traffic loads can be measured over a long period of time (months and years), and the change in the measured dynamic strain over this period of time can be analyzed. This can give insight into the stiffness of the pavement, damage, and deterioration, and can aid in estimating the fatigue damage and the pavement’s remaining life cycle [25,26].

PZT sensors perform well for condition monitoring of road pavement while measuring the vibrations and axle loads of passing traffic, offering a fast response to impact loading. However, PZT sensors can measure only dynamic strain or rapidly changing strain; they are not able to measure constant strain, because the generated electrical charge caused by deformation dissipates over time. Therefore, a PZT sensor under constant strain will not retain a steady output. The output of a PZT sensor is low, so shielded cables and signal amplifiers are required to mitigate interference. PZT sensors are susceptible to temperature influence; therefore, WIM systems usually employ periodic temperature correction or calibration processes, which makes it challenging to maintain year-round accuracy for these sensors [19,20,27].

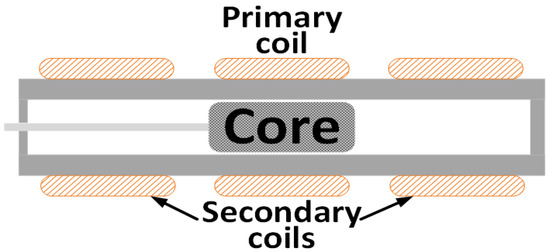

1.4. Linear Variable Differential Transformer

The Linear Variable Differential Transformer (LVDT) is a widely used device for linear displacement measurement and is also implemented in road pavement monitoring. LVDTs can be utilized to measure the displacement of one layer or multiple layers of the pavement. LVDTs are installed in the road pavement by drilling holes, placing the device into the hole, and sealing it [28].

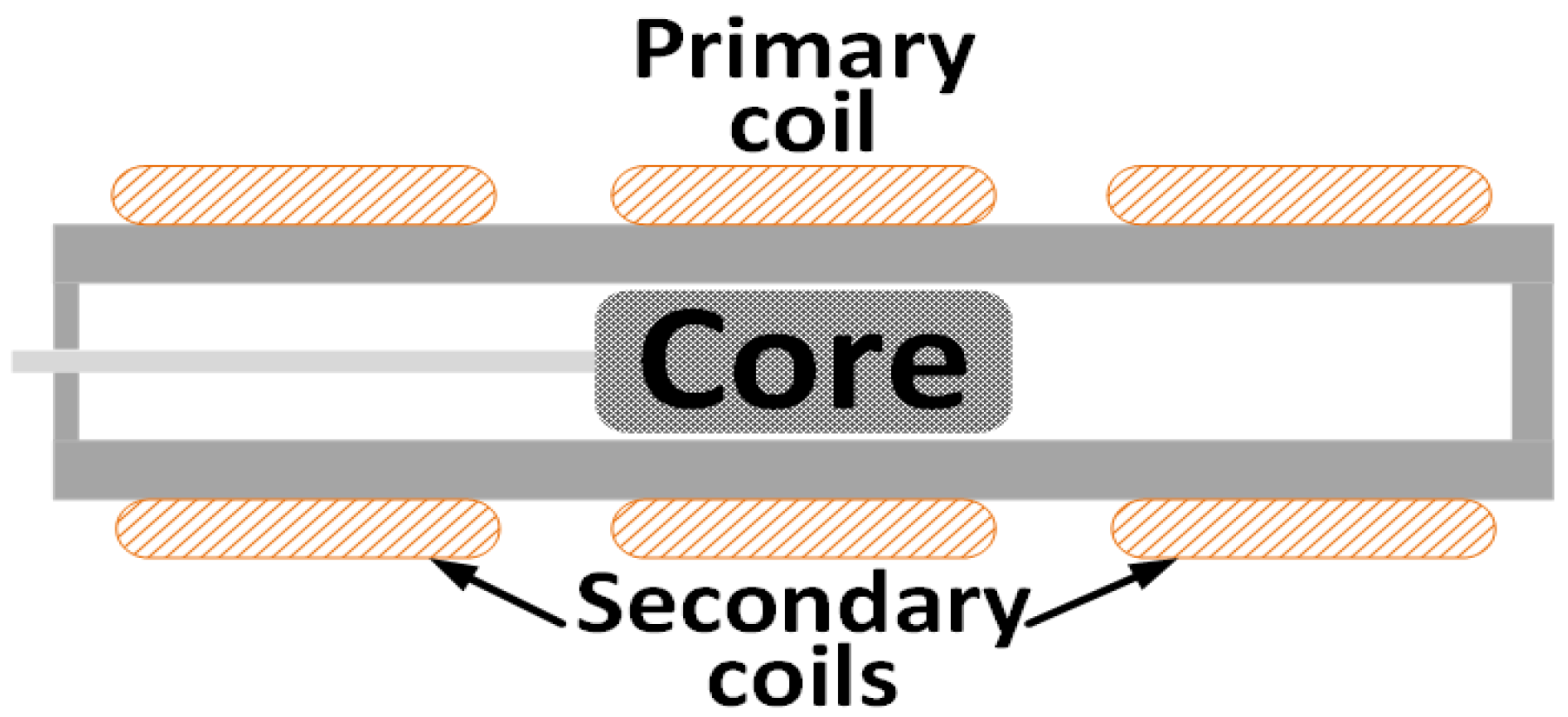

LVDTs consist of a hollow cylindrical shaft, a solid cylindrical core made of ferromagnetic material, and a series of inductors, as shown in Figure 4. The core is free to interact with electromagnetic fields generated by the inductors.

Figure 4.

Cross-section of LVDT.

An LVDT’s primary winding is energized by alternating current, generating a magnetic flux that induces voltage in the two secondary coils. The ferromagnetic coil is free to move axially, as a consequence of the displacement of the measured structure. The output of an LVDT is a differential voltage between the two secondary windings. This voltage varies depending on the core’s axial position. As the core shifts axial position, the mutual inductance of the secondary and primary coils varies because the magnetic field between primary and secondary coils is altered; hence, the output voltage of an LVDT changes proportionally to the displacement of the core. This allows for precise displacement measurement over a wide range [1,29,30].

Furthermore, LVDTs exhibit high resolutions of around 1 µm, a repeatability of 99% of the measuring range, and an accuracy of 0.25 to 0.5% of the full scale range (FS); they can perform well in harsh environments with vibrations [31,32,33]. This makes them applicable for the structural health monitoring (SHM) of road pavements to measure vertical deformation under applied loads and measure both instantaneous and residual deformation of the pavement [30,34]. However, the measurement range for deflections is limited, from 0.5 to 250 mm [35].

In terms of overall performance, LVDTs are quite comparable to the FOS-based displacement sensors (most commonly implemented using FBGs). LVDTs typically offer higher displacement resolution (0.1–1 μm for LVDTs, 0.5–2 μm for FBG displacement sensors) and better accuracy (0.25–0.5% of FS for LVDTs, 0.5–1% FS for FBG displacement sensors) [36,37,38,39,40]. Both types of displacement sensors are well suited for the measurement of static displacement; for dynamic displacements, LVDTs generally offer better performance than FBG displacement sensors (due to higher bandwidth and simpler signal conditioning). Moreover, usually, a higher measurement range can be achieved with LVDTs [41,42,43].

However, LVDTs have a limited attainable distance between the sensor and the data acquisition device (due to signal degradation), are susceptible to EMI, and require a power supply to the sensor. FBG displacement sensors are well suited and have a significant potential for a long-term monitoring application, because LVDTs can suffer from long- term drift caused by electronic instability (cable resistance varies with temperature, moisture ingress, corrosion); the temperature influence on FBG sensors wavelength shift is linear and can be successfully compensated by using internal reference FBG sensor, enabling stable long-term operation [41,42,43,44].

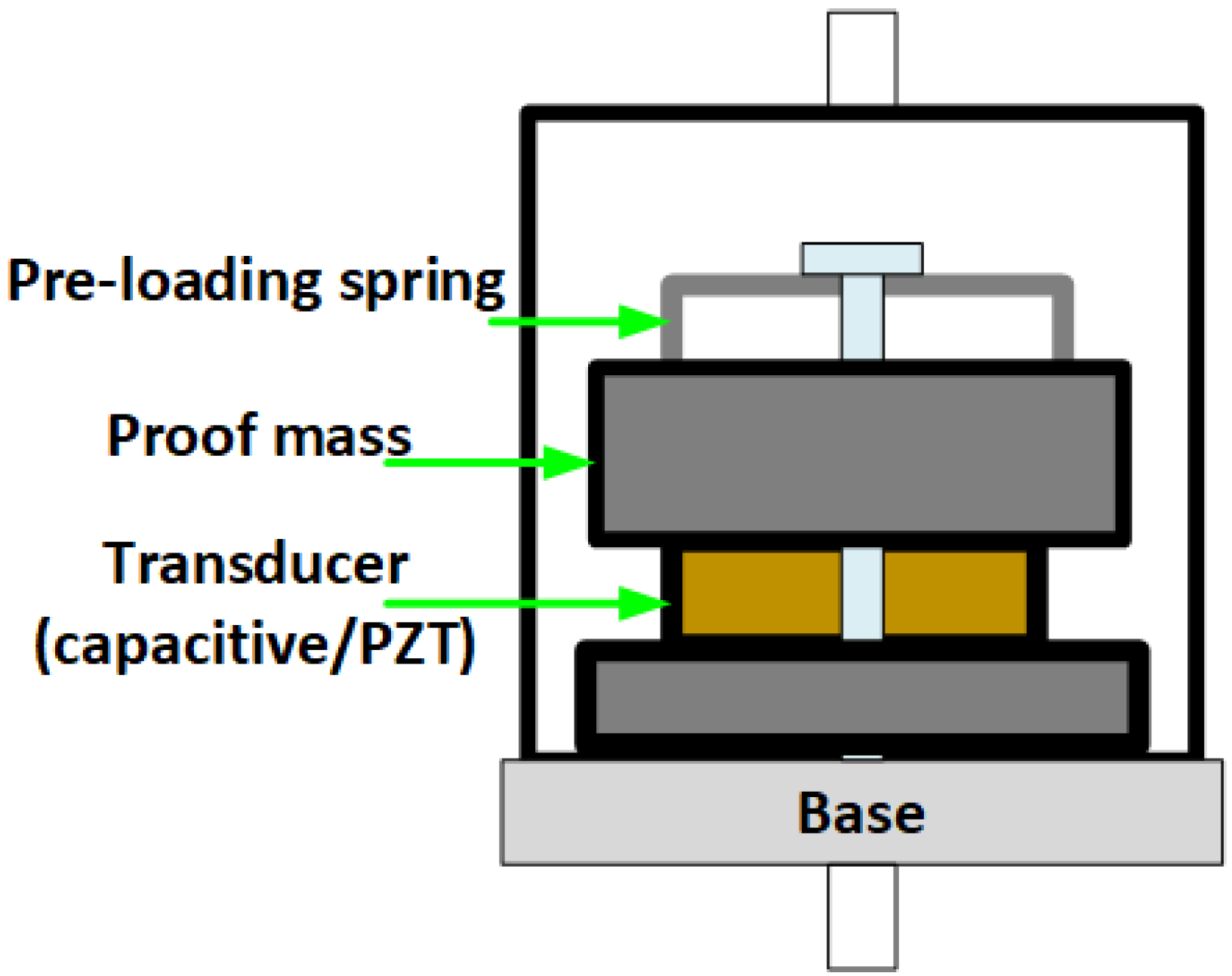

1.5. Accelerometer

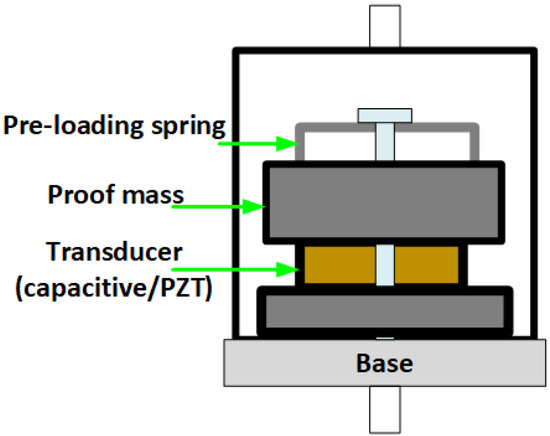

Accelerometers measure vibration-induced acceleration from which velocity or displacement can be derived. Standard accelerometers are based on either capacitive or piezoelectric sensing principles. These sensors can be attached to the surface of the pavement or embedded into the pavement near the surface to detect the dynamic response of the pavement to traffic. Accelerometers are usually constructed with a proof mass on a spring that interacts with a transducer, as depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic cross-section of accelerometer device.

As a consequence of vibration and load, the mass moves. In the capacitive type, the movement of the mass causes the capacitance change between the plates of a capacitance transducer, producing an electrical output proportional to acceleration. In a piezoelectric-type accelerometer, the mass interacts with a PZT, which generates an electrical current proportional to the acceleration. These sensors are highly precise and can detect high-frequency events such as vehicle bounce and road-roughness-induced vibrations. The main uses of these sensors include monitoring of interaction events between the vehicle and pavement, such as potholes, pavement roughness, and structural dynamic testing. The accelerometer sensors can be surface-mounted or embedded into the pavement [1,45,46]. Accelerometers that are used in road condition monitoring have a narrow measuring range (1–5 g), with a sensitivity of around 1 µg [45,47,48].

PZT- and capacitive transducer-based accelerometers are mature electrical sensing technologies that offer high sensitivity as well as frequency response. While FBG-based accelerometers offer slightly lower sensitivity, they are more sustainable for implementation in long-term SHM systems due to their long-term stability, multiplexing capabilities, immunity to EMI, as well as their robustness in terms of embedment into the pavement. Furthermore, FBG-based accelerometers can be integrated into one sensor network together with FBG strain and temperature sensors using a single signal interrogator, decreasing overall system complexity and cost [49,50,51,52].

1.6. Electrical Temperature Sensors

The temperature monitoring of road pavements is crucial in understanding and assessing the performance of the pavements in different climatic or weather conditions, as well as enabling temperature compensation for strain, pressure, displacement, and other measurements. Popular conventional approaches for temperature measurement for road infrastructure are thermocouples, resistance temperature detectors (RTDs), and thermistors. Among them, thermocouples are the most commonly used temperature sensors [1,28,53].

Thermocouples consist of two conductors joined at the ends that are made of different metals, forming a junction. A small voltage is generated due to the Seebeck effect, when the junction is heated or cooled. Thermocouples are often used for asphalt surface temperature measurements and temperature measurements of different asphalt layers to capture the temperature profile of the pavement. Thermocouples can operate from subzero to very high temperatures and offer an accuracy of 0.5 to 5 °C [28,54].

RTD is a resistor-based sensor whose resistance changes as the temperature varies. RTDs are often made out of platinum and exhibit a linear change in resistance with temperature. RTDs offer an accuracy of 0.1 to 1 °C [28,54]. Thermistors are semiconductor material sensors, the resistance of which is temperature-dependent to a higher degree than regular resistors, offering measurement accuracy of 0.05 to 1.5 °C, but with decreased operational range [28,54].

While electrical temperature sensors are relatively inexpensive, accurate, and easy to instrument for point measurements of temperature, they exhibit several limitations: EMI sensitivity, limited measurement distance (due to the noise, signal attenuation), and difficulty in scaling for network-type SHM applications. Fiber-optical sensors, on the other hand, are able to sustain higher measurement distances, offer multiplexing capabilities, and allow for the possibility to deploy quasi-distributed (FBG-based temperature sensors) or fully distributed temperature sensing (DFOS-based sensors); this enables the measurement of temperature gradients along the whole structure, facilitating the deployment of SHM solutions for road infrastructure at a network scale [55,56].

A detailed description regarding the operation and use of FBG optical sensors is provided in Section 2.3; for distributed Brillouin, Raman, and Rayleigh optical sensors, the description is provided in Section 2.4.

2. Fiber-Optical Sensor Topicality in Infrastructure Monitoring Applications

Civil infrastructure is under continuous stress conditions and environmental exposure, particularly road infrastructure, which experiences rising traffic volumes that impose greater load on the pavements, accelerating wear and deterioration. This elevates the importance of structural monitoring solutions for such infrastructure to ensure the safety, necessary performance, and longevity of the infrastructure.

Furthermore, various industries, including civil infrastructure, are transitioning into so-called smart industries, incorporating technological solutions to promote automation, efficiency, safety, longevity, and overall sustainability. To achieve this, modern structural monitoring solutions require sensors that enable high reliability and accuracy, robustness, and performance, as well as real-time monitoring capabilities to ensure that the gradual deterioration of the structure is detected to track and assess the overall condition, and carry out necessary actions to repair the damage and mitigate risks to ultimately extend the lifespan of the structure [56,57]. Therefore, one of such potential technologies to be applied can be FOS-based solutions. For instance, in recent years, multiple technological and scientific fields have been merged, and the development of cross-industry and scientific fields has advanced. For example, there is growing interest [58,59,60] in polymer optical fiber realization for distributed fiber-optical sensors, provision of strain detection in road construction, as well as critical deformation monitoring.

Real-time data fusion systems are also worth mentioning in this FOS-related field: this approach is relevant when multi-sensor data are correlated for real-time multi-object tracking [61]. Additionally, intelligent vehicles that are based on multi-source data fusion to support real-time targeted detection systems [62] are also vital for the safety of the road infrastructure and its users. Hence, upcoming intelligent transportation systems [63] will also rely on such mechanisms, tools, technologies, and data.

Last but not least, the growing interest in artificial intelligence (AI) and the provided capabilities are also promising in the field of sensor realization, thus ensuring AI-enhanced sensor performance. For example, there is growing interest in AI-enhanced sensing for vulnerable road user safety purposes [64]. This kind of intelligent traffic monitoring is possible with the use of different distributed sensors; acoustic ones in particular are showing recent topicality [65]. Supplementing that, recent studies also show deeper integration with IoT systems, especially in road-related constructions such as bridges [66].

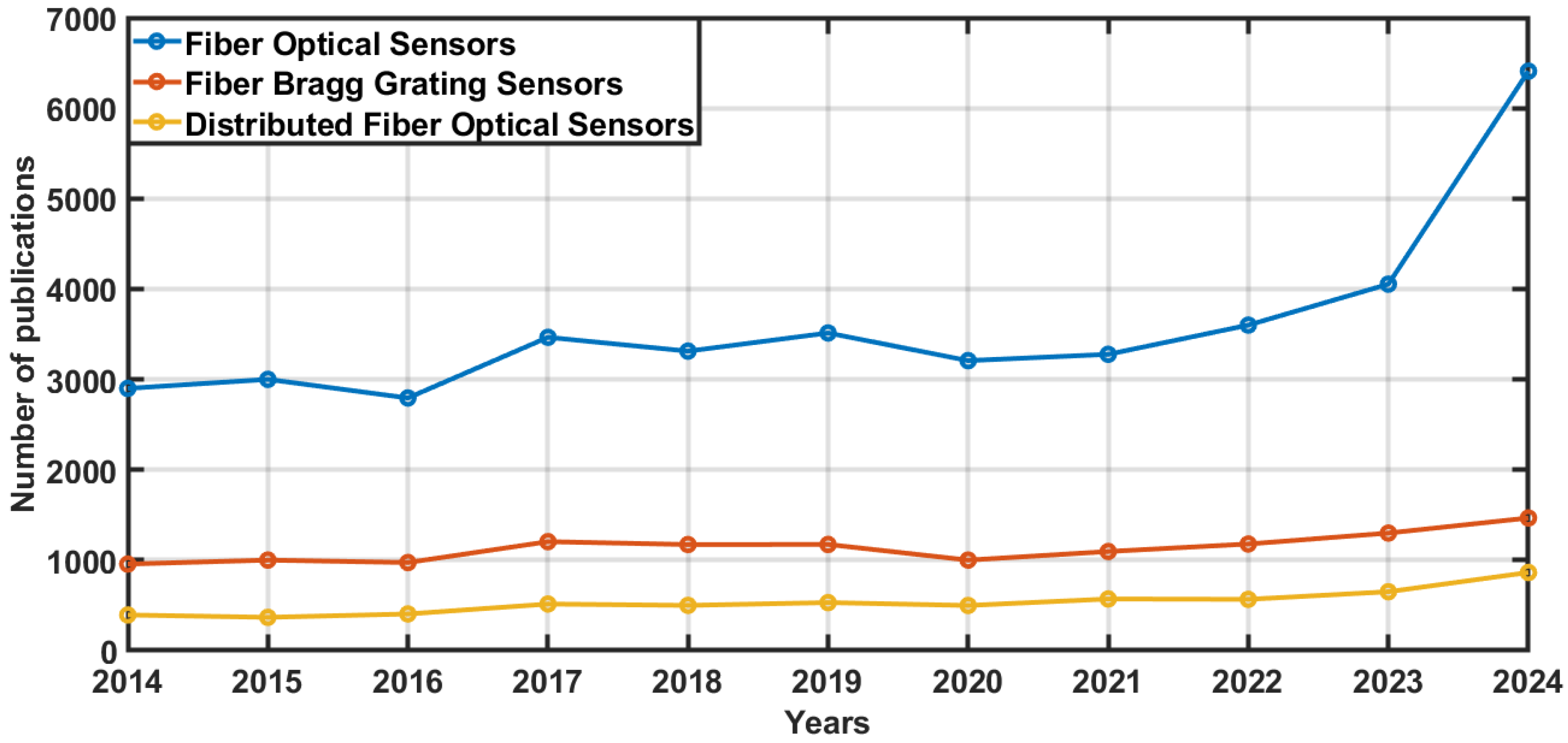

2.1. Statistics of Fiber-Optical Sensors’ Topicality

FOSs and their solutions are gaining prominence in the structural monitoring field across various industries. The high relevance of these technologies is in significant part due to the numerous advantages the FOS possess compared to the conventionally adopted electrical sensors for monitoring solutions, such as high accuracy, reliability, immunity to electromagnetic interference, ease of multiplexing, distributed sensing capabilities, small dimensions, high resilience in harsh environments, and others [67,68,69,70].

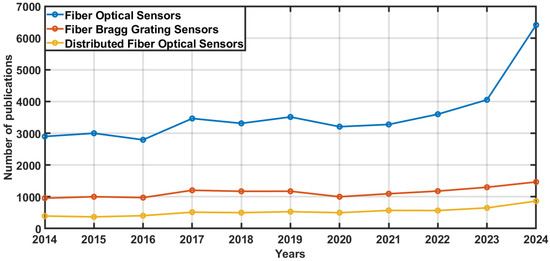

The high relevance and potential of FOS technologies are underscored by considering the market trends. The overall market share of FOSs is presently relatively low, and the value of the FOS market reached EUR 2.98 billion in 2024. However, it is projected to grow to EUR 7.2 billion by 2033 [71,72]. This growth rate outpaces those of many traditional sensor segments, indicating the high potential and value of the technology, as well as rising demand for such solutions offering high-performance sensing. Furthermore, in the field of research, it is a common trend that the topicality of FOS is quite high. The number of publications on the topic is increasing every year, as evident in Figure 6, which underlines the high interest in the field, since these publications offer actual solutions to deploy these sensors for infrastructure monitoring in various scenarios, case studies, new sensor designs and architectures, which is accelerating and will continue to accelerate the development, interest, and technological maturity in this field.

Figure 6.

Number of scientific publications in the Scopus database authored on the topic of fiber-optical sensors.

This trend is driven by factors such as demand for real-time monitoring with improved performance compared to electrical sensors. Furthermore, advancements in the fiber-optics field have further improved the performance and reduced the cost of the technology, making it more accessible and attractive for implementation in various monitoring solutions [56,71,72].

2.2. Fiber-Optical Sensors in Modern-Day Road Infrastructure Monitoring

Road infrastructures are large, distributed, and exposed to growing heavy traffic loads as well as harsh environments. Moreover, road infrastructures are critical assets that must remain durable and safe over their lifespan. Given the nature of these infrastructures, it is quite challenging to deploy SHM solutions on a large scale, not even considering the solutions for monitoring it on a network scale [73]. The challenge is further compounded by the limitations and constraints imposed by conventional electrical sensors, which have been widely used for road infrastructure monitoring and management. Those limits and constraints include the necessity for an external power supply to the sensor, susceptibility to EMI, challenging multiplexing, and the fact that these sensors can only perform measurements in discrete points [1,8,21,24,28,36].

The concept of smart road infrastructures requires solutions to enable effective, real-time, large-scale monitoring [74]. FOSs offer such possibilities, considering the advantages they possess over conventional electrical sensors used for road monitoring: EMI immunity; long operational range; efficient multiplexing capabilities with quasi-distributed or even fully distributed sensing to acquire continuous strain or temperature profiles; high sensitivity; the prospect of measuring multiple parameters with one sensor. Furthermore, FOSs are completely passive; they do not require an external power source to operate, and they require minimal cabling in comparison with electrical sensors [67,68,69,70,75,76,77,78,79,80].

For the last couple of years, FOSs have been considered for the SHM of road infrastructures to monitor parameters such as internal strain, temperature, displacement, and vibrations. Monitoring these parameters is crucial for assessing the condition and performance aspects of road infrastructures. FOSs can be embedded or attached to pavement or structural components of bridges and tunnels to obtain continuous real-time data on various structural and operational performance parameters. Monitoring these parameters enables effective pavement SHM in the exploitation period, quality control of the construction and materials used while building the infrastructure, and monitoring of traffic loads, including WIM [81,82]. Chief types of FOS already deployed are FBG, and scattering-based or distributed fiber-optical sensors (DFOSs), such as Rayleigh, Raman, and Brillouin sensors [67,68,69,70,75,76,77,78,79,80].

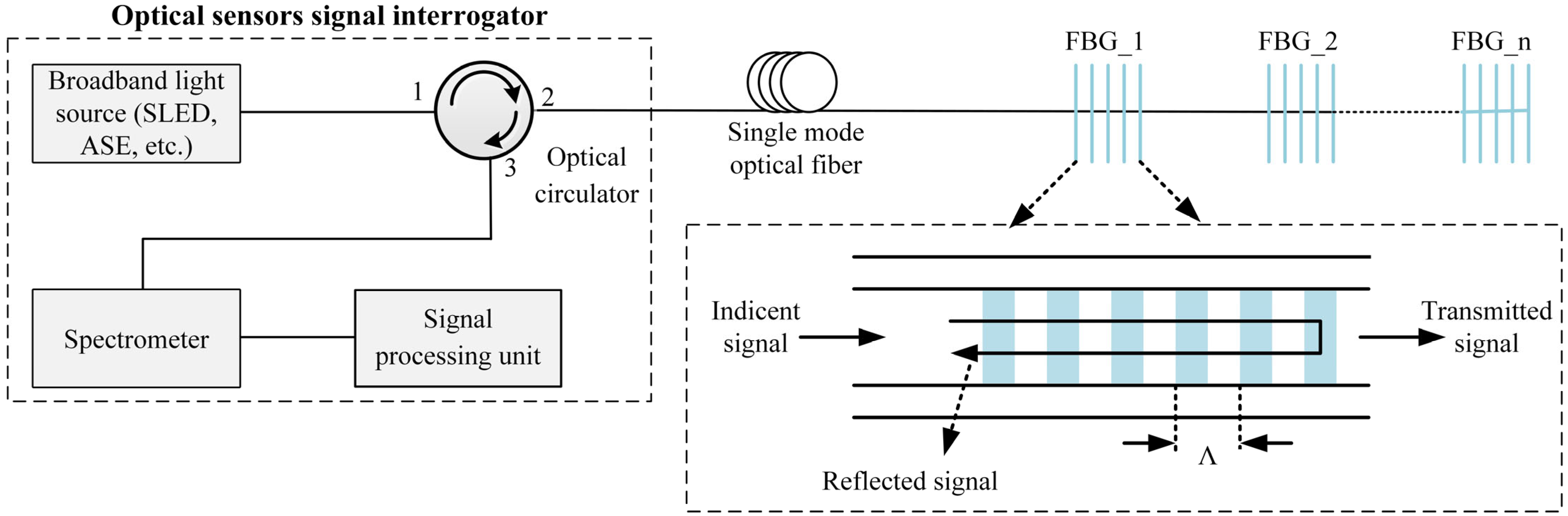

2.3. Fiber Bragg Grating Optical Sensors for Monitoring

FBG sensors are considered a well-established and mature optical sensing technology for civil infrastructure. An FBG is manufactured inside the optical fiber where a periodic modulation of refractive index is inscribed, creating a fiber grating. The Bragg wavelength equation [67,68,69,70], describing the central wavelength of the reflected optical signal, can be estimated as follows:

where λB is the Bragg wavelength, is the effective refractive index of the fiber core, and Λ is the grating period.

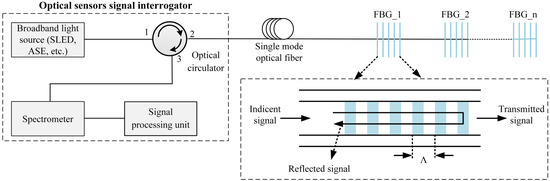

When broadband light propagates through the fiber, the inscribed FBG reflects a specific wavelength of the light, called the Bragg wavelength, but transmits all other wavelengths. A 3-port optical circulator (OC) is used to separate the FBG sensor signal flows—transmitted (port 1 to 2) and reflected (port 2 to 3). In Figure 7, a typical operational principle of the FBG is depicted.

Figure 7.

Operating principle of the FBG.

In an instance where an FBG sensor is subjected to a strain or temperature change, the spacing of the grating and its optical properties vary slightly as a consequence. This, in turn, causes a linearly proportional shift in Bragg wavelength. Monitoring the Bragg wavelength enables direct measurement of the applied strain or temperature change to the sensor with high precision and accuracy. Typical sensitivity for strain measurement is around 1.2 pm/µε and 10 pm/°C for temperature, while attaining the accuracy of 1 µε or 0.1 °C for temperature measurements [83]. FBG sensors are point sensors on their own. However, multiple gratings can be inscribed into a single fiber in different locations, establishing a quasi-distributed FBG sensor network [67,68,69,70,82,84,85].

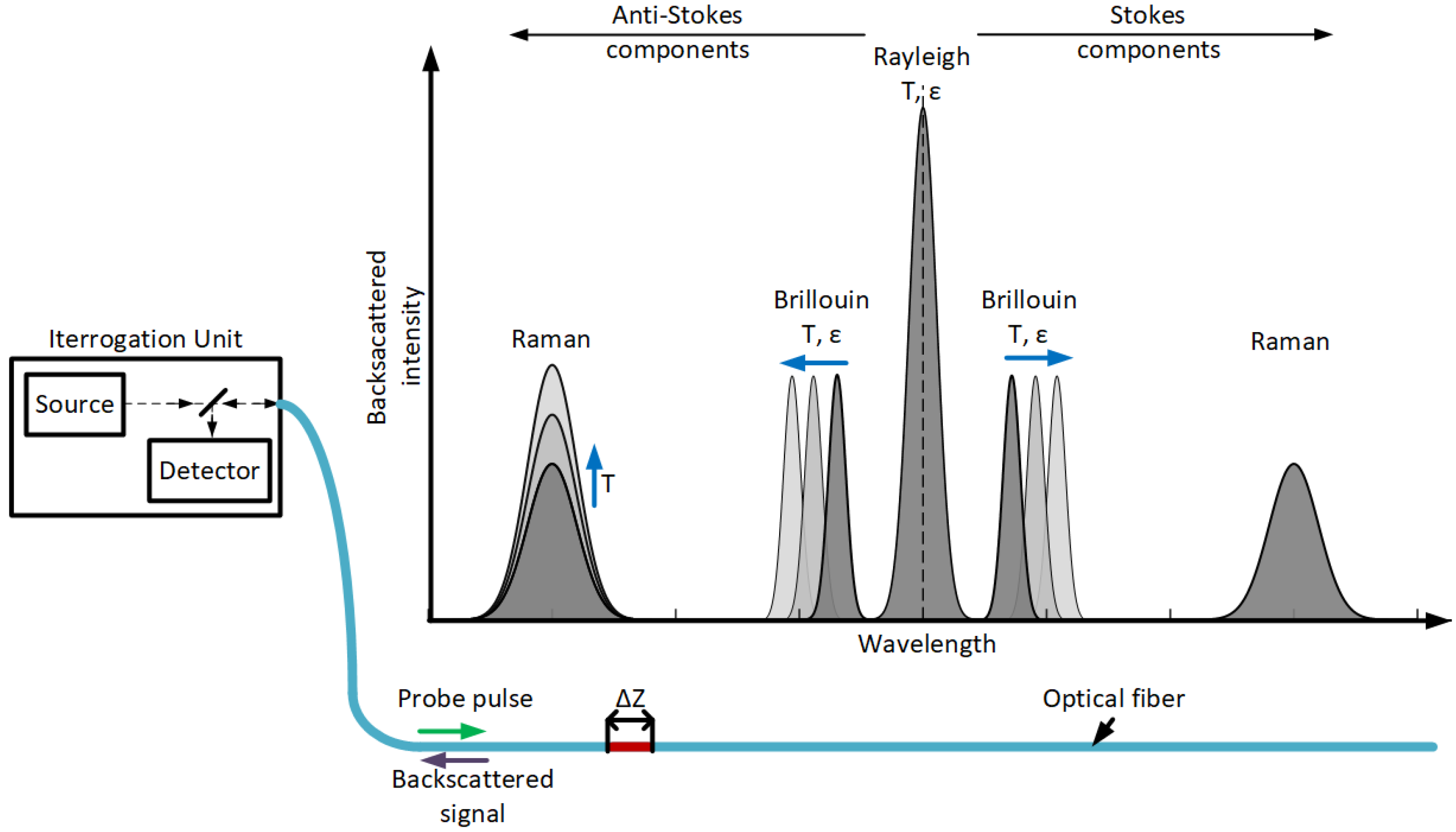

2.4. Distributed Rayleigh, Brillouin, and Raman Fiber-Optical Sensors for Monitoring

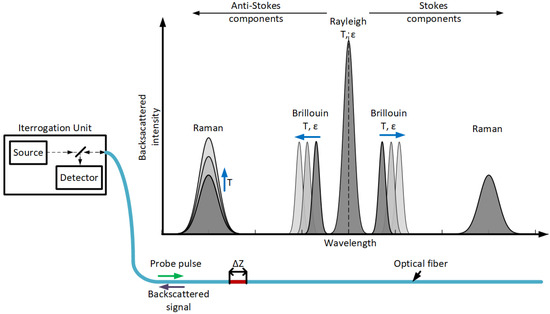

DFOS provides continuous measurements of strain or temperature along the entire length of the optical fiber by exploiting the scattering phenomena in the fiber. As the light launched into the fiber propagates through the fiber, it is partially backscattered, and the intensity, phase, or spectrum of this backscattered light is affected by localized environmental conditions such as applied strain and temperature [75,76,77,78,79,80].

Rayleigh scattering is an elastic scattering of light that occurs in an optical fiber due to random microscopic refractive index fluctuations. The DFOS interrogator launches light into the optical fiber and analyzes the backscattered light signal. The changes in the backscattered spectrum or phase are used to derive the strain or temperature profile at certain points along the fiber.

One of the relevant equations in Rayleigh scattering strain sensing is the estimation of spectral shift, ΔνR, measurements [86], that are calculated based on the variations in the temperature, ΔT, and the strain, Δε:

where Cε is the strain sensitivity coefficient and CT is the temperature sensitivity coefficient (shown in GHz/°C).

ΔνR = CεΔε + CTΔT

Solutions, such as Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry (OFDR) and phase-sensitive Optical Time Domain Reflectometry (φ-OTDR), can be used to enable high-resolution Rayleigh-scattering-based sensing. Depending on the interrogation method being used, Rayleigh-scattering-based DFOS solutions offer spatial resolution from around 1–10 m and a range of a few tens of kilometers (OTDR-based interrogator) [76,87,88] and resolution up to around 0.5 mm and a typical range of 100 m (OFDR-based interrogator) [76,89,90]. The high attainable spatial resolution, even if the operational distance of the sensor has to be conceded, makes them appropriate for detecting or analyzing highly localized distress like cracking, small strain, or temperature gradients. Commercially available OFDR-based Rayleigh-scattering-based sensor solutions have a limited operational distance of about 100 m, which can limit their application prospects for monitoring road infrastructure at the network level [91]. In that aspect, OTDR-based Rayleigh scattering DFOSs possess great promise for large-scale real-time monitoring solutions for traffic monitoring. A major application of OTDR-based Rayleigh scattering DFOSs is distributed acoustic sensing (DAS). In DAS, a DFOS operates as an array of virtual vibration sensors (or microphones, if you will), continuously monitoring the vibrations along its length. DFOSs can be installed along the road to continuously detect and assess the vibrations that are caused by moving vehicles. Each vehicle produces a characteristic vibration signature that can be analyzed by the implementation of data analysis algorithms to classify the vibration events to potentially detect the vehicle type, average speed, direction, and position on the road, and detect crashes or potholes [92,93]. Rayleigh-scattering DFOS possess high response, making them ideal for the detection of dynamic events or distress, such as vibration, acoustics, and seismic waves, as well as high accuracy at around 1 µε and 1 °C for temperature measurements [75,76].

Brillouin scattering is an inelastic scattering process that is caused by the light’s interaction with acoustic phonons in the optical fiber’s material, producing a frequency-shifted backscattered light (Stokes light). The frequency shift () between the pump and backscattered Stokes light is estimated as [94,95]:

where is the effective refractive index of the fiber, is the acoustic velocity in the fiber, and is the wavelength of the incident light.

The Brillouin frequency shift is caused by the acoustic wave’s propagation characteristics, and it is highly sensitive to environmental conditions. Physical changes like strain or temperature affect the optical fiber’s acoustic velocity and the refractive index, which alters the Brillouin frequency shift. The change in frequency is approximately linear (given the possibility of measurement error deviation) to the strain or temperature change, which enables the Brillouin scattering-based sensing. Brillouin-scattering-based sensor solutions, unlike Rayleigh-scattering-based ones, can be successfully deployed for monitoring large structures and road infrastructure at the network scale due to the relatively high operational range (in enhanced laboratory setups up to 100 km). The accuracy of Brillouin scattering-based sensors is usually at 5–20 µε and 1 °C for temperature measurements for practical applications, though higher accuracy has been demonstrated with advanced setups over relatively short distances of several kilometers. Furthermore, Brillouin sensors exhibit good stability and reliability for long-term monitoring. And they are a good choice for measuring static strain or temperature over long distances, which makes them prospective for deploying FOS-based SHM solutions for road infrastructure on the network level [77,78,79,80].

Raman scattering is an inelastic scattering process that is caused by the interaction between the light and the vibrational modes in the fiber’s glass molecules. As light is transmitted through the fiber, backscattered Stokes and anti-Stokes light are produced. One of the relevant calculations in Raman scattering-based sensing regards the anti-Stokes/Stokes intensity ratio (R(T)) calculation [96,97,98,99]:

which is achieved by estimating the anti-Stokes signal () and the Stokes signal (). is the wavelength of the Stokes Raman backscattered light and λaS is the wavelength of the anti-Stokes Raman backscattered light. h—Planck’s constant, and Δν is the frequency shift between incident and scattered light. k—Boltzmann’s constant, while T is the absolute temperature.

The backscattered light is frequency-shifted, and the extent of the frequency shift depends on the local temperature variation in the optical fiber. The anti-Stokes component is strongly temperature-dependent, while the Stokes component is only marginally temperature-dependent. By implementing OTDR or OFDR (less common for Raman scattering-based sensing solutions), each point of the fiber can be assessed, yielding a continuous temperature profile along the length of the fiber. Raman scattering in silica fiber is insensitive to strain; Raman-based DFOS can uniquely measure absolute temperature without interaction with strain. Therefore, Raman-scattering-based DFOS solutions are used for temperature monitoring on a large scale, especially for temperature profiling in road pavement structures, to assess the condition of the pavement and detect distress, as cracks, voids, or delamination of the pavement will produce differences in the local heat profile. It is also used in tunnels to detect leakage or fire by assessing the detected temperature anomalies. In practical applications, Raman-based DFOSs attain a spatial resolution of around 0.2–2 m for sensor lengths of tens of kilometers. Typical temperature accuracy is at 0.1–1 °C, while the dynamic range is around 100 km [100,101,102,103].

Rayleigh, Brillouin, and Raman-based scattering principles are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The principles of Rayleigh, Brillouin, and Raman scattering in fiber-optics.

As can be seen in Figure 8, the elastic Rayleigh peak at the pump wavelength dominates between them, while much weaker inelastic Raman Stokes/anti-Stokes bands at relatively more distant wavelength offsets and narrow Brillouin frequency-shifted peaks at relatively closer offsets are also present.

We have also created a unified data comparison (see Table 1) of topical traditional (such as manual and imaging inspection, strain gauge, inductive loop, weigh-in-motion, falling weight deflectometer) and FOS technologies (FBG and DFOS) that can be used as a solution for physical parameter monitoring of road infrastructure.

Table 1.

Comparison of topical traditional and fiber-optical sensor technologies [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,67,68,69,70,75,76,77,78,79,80,82,84,85,89,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131].

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of traditional road-monitoring technologies versus modern fiber-optical sensing methods. It highlights the types of parameters each technology can measure, along with their typical resolution, accuracy, robustness, perceived technology readiness level (TRL) in terms of specific technologies’ integration and application into smart road infrastructure solutions, and cost levels. Overall, fiber-optical solutions (FBG, Raman, Brillouin, Rayleigh) offer higher precision and multi-parameter sensing capabilities compared to traditional methods, though with higher overall system costs.

Conventional road infrastructure monitoring technologies typically achieve high technology readiness levels (TRL 7–9), as technologies like manual inspection and digital imaging are already standardized and widely deployed, offering high robustness due to their non-contact operational principle. Electrical sensor technologies individually are well established; however, their full integration into smart road infrastructure monitoring systems is still relatively limited.

FOSs provide a higher robustness when compared to electrical sensors due to the inherent immunity to EMI, resistance against corrosion and other environmental factors, as well as the sensor design considerations. In terms of TRL, Raman-distributed temperature sensor systems are mostly technology-ready (TRL 8) and have already been implemented in commercial smart infrastructure applications; these are followed by Brillouin- and Rayleigh-scattering-based systems, which remain at TRL 7 due to the higher system complexity and absence of actual commercial smart road infrastructure monitoring solutions.

3. Potential and Topical Physical Parameter Monitoring in Road Infrastructures Using Fiber-Optical Sensor Technologies

For road infrastructure monitoring, multiple physical parameters can be measured and monitored by using certain optical sensors, which can collect the data necessary to maintain the safety and security of built structures; moreover, they can be used to build datasets for smart-road-based solutions. The key physical parameters for data collection are strain, temperature, vibration, pressure, and humidity. Yet when deciding on which physical parameters would be used in specific solutions, the broader perspective has to be taken into account; one needs to decide on the type of optical sensor technology that would be most suitable, given the specifications. Some of the main physical parameters that are relevant to future smart road transportation monitoring are analyzed in this section.

3.1. Temperature Monitoring in Road Infrastructure

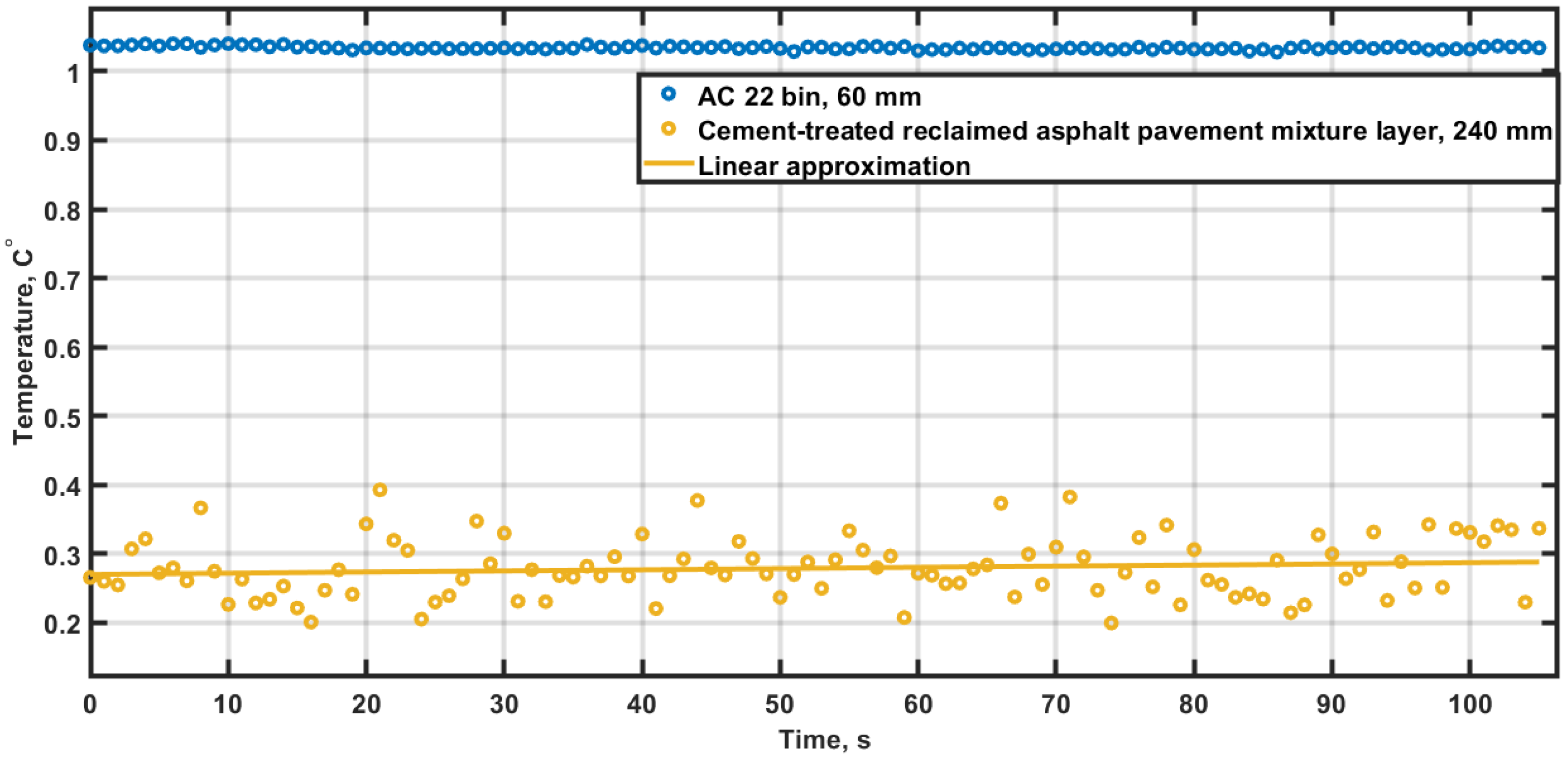

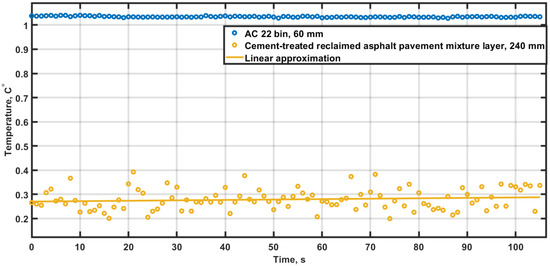

Temperature monitoring is a crucial factor for maintaining road infrastructures, as temperature shifts and fluctuations can lead to the expansion and contraction of the used materials during pavement laying and long-term operation. Accurate and real-time temperature data enables managers to plan maintenance efficiently. FBG sensors have been used to measure temperature versus time in road and pavement cement-treated reclaimed asphalt mixture layers (240 mm thick) and asphalt concrete, AC22 (60 mm thick), layers, as shown in Figure 9. The measurements were taken in the morning, and the data show that the surface layer (AC22) of the road is 0.8 degrees higher than the cement-treated reclaimed asphalt pavement mixture layer.

Figure 9.

Temperature versus time in road pavement layers.

Researchers have shown [132,133] the potential and durability of FBG optical sensors; they are able to measure temperatures up to +135 °C and achieve temperature sensitivity of 0.01075 nm/°C. In their research, FBG optical sensors were installed in a prepared fresh asphalt concrete structure. Zhao et al. [134] highlighted the importance and topicality of the growing number of smart road networks and distributed optical sensors in this niche, with temperature sensors being one of them.

Another recent study [135] focused on the optimization of structural design in road-use optical fiber sensors. In this research, the packaging structural material of the sensor was optimized, highlighting the cross-sensitivity of temperature and strain measurements, again proving the need for temperature optical sensors when strain optical sensors are used. Additionally, Dong et al. [136] proposed a strain correction formula (based on the Boltzmann equation) considering the different temperatures for the different asphalt pavement layers. Such an approach in the typical asphalt environment temperature range (from 20 °C to 60 °C) showed a decrease in the average error in strain measurements from ~4 to 90%, based on the course of the road layer.

Liang et al. [137] indicated optical temperature sensors and their involvement in advancing autonomous driving vehicles, contributing to safe road infrastructure and network development potential. Thus, temperature optical sensors directly and indirectly contribute to road monitoring, as well as assisting in gathering precise measurement data of other physical parameters and smart application development.

3.2. Strain Monitoring in Road Infrastructure

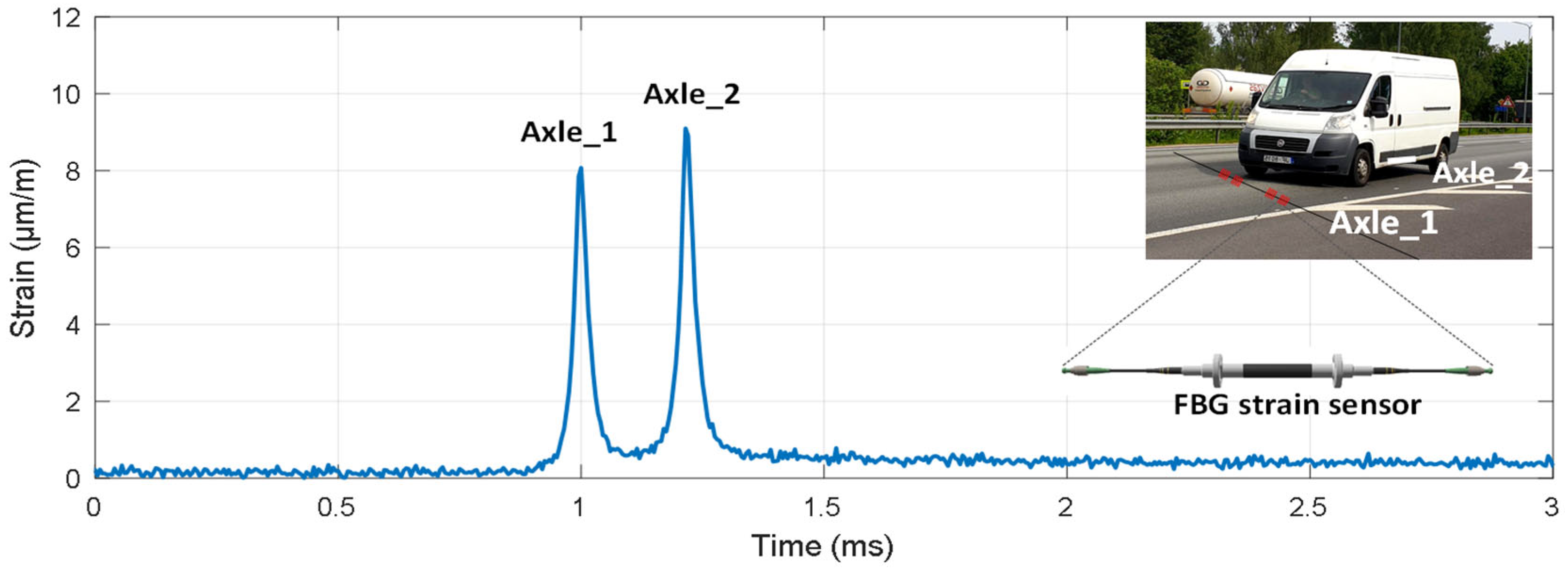

Strain monitoring is one of the main aspects to consider for road structure integrity and longevity assessment. By detecting strain-induced deformations and stress distribution within the pavement layers, road engineers can proactively address the most probable failures, optimize maintenance schedules and plans, and improve the overall safety of the road infrastructure and its users. Our realization of FBG temperature and distributed strain sensor integration in the road pavement layer is shown in Figure 10. Initially, a small groove (of the typical width of 4–6 mm) was cut, and then the groove was leveled and dried. After surface preparation, sensor integration was conducted, and they were encapsulated with specific “smart” packaging materials that matched the modulus of the asphalt to prevent “stiffness mismatch”. The sensor was fully encapsulated with bitumen emulsion; then, the next layer of road was applied.

Figure 10.

Temperature FBG and distributed strain sensor integration in road pavement layer.

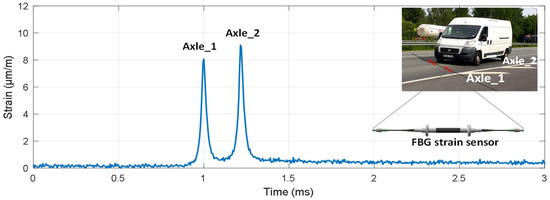

In our previous research [82,84,109,123], FBG optical sensors were successfully implemented in various conditions and layers, embedding them within the pavement structure to monitor vehicle-induced strain, as shown in Figure 11. However, it is important to highlight that FBG-based strain sensors are inherently cross-sensitive to temperature, as both mechanical strain and thermal effects induce Bragg wavelength shifts. To ensure accurate strain quantification, temperature compensation is therefore required. Therefore, one of the ways to ensure that temperature effects are mitigated is by employing a reference FBG that is isolated from mechanical loads and thus responds only to temperature changes. The reference wavelength shift is used to correct the measured strain FBG reflected signals, allowing the true mechanical strain to be extracted. This approach is widely used in FBG sensing systems and ensures stable performance under varying environmental conditions. Studies have demonstrated FBG sensors’ capabilities to capture real-time strain data and strain variations, addressing different vehicle types and axle configurations and thus proving their effectiveness in road pavement SHM [138,139].

Figure 11.

Optical FBG strain sensors for road infrastructure monitoring applications.

Xin et al. [8] discussed self-sensing concrete pavement by using multiple rows of strain sensors. The concept of conductive polymer composite material realization has also been investigated as an option. Meanwhile, Liu et al. [2] showed accelerated pavement testing (APT) and falling weight deflectometer (FWD) experiments for the road segment where FBGs were used. Precise strain values could be recorded. For instance, the horizontal transverse sensor indicated peak strain values around 66 με while horizontal longitudinal strain ranged between 3 and 5 με. Hence, monitoring strain components from various layers and angles is crucial to achieve comprehensive datasets. Lastly, another recent study [140] proposed a strain sensor realization as a traffic stream estimation method.

3.3. Vibration Monitoring in Road Infrastructure

Vibration monitoring [141,142] is yet another crucial component in the assessment of the structural integrity and safety of the road infrastructure. Vibration can also be correlated with the detection of settlements, cracks, or road infrastructure material fatigue, which eventually can also decrease the longevity and overall performance of the road infrastructure. Hence, advancements in optical sensor technologies have ensured more accurate and real-time monitoring capabilities of vibrations, supporting proactive maintenance and governance of the road network.

FOSs, especially distributed ones that use phase-sensitive optical time-domain reflectometry (ϕ-OTDR), can be utilized for vibration monitoring. Such optical sensors can localize vibrations that are caused by different sources, including vehicles or other environmental factors impacting the infrastructure of interest. Single-mode optical fibers used in telecommunication infrastructure are typically built over long distances, and near main roads as well; therefore, vibration monitoring can be realized [123,141,142].

Additionally, not only the direct implementation of vibration-based sensors within the pavement structure, but also integration within the vehicles themselves, can provide valuable data. The authors of [143] proposed an alternative approach for road condition estimation. Taxi vehicles were equipped with a black-box type of equipment to collect vibration data to analyze the pavement condition and vehicle movement speed. Such a method could also be feasible for FOS implementation; variables such as vehicle speed and optical sensor placement should be analyzed.

The authors of [144,145,146] have shown that vibration monitoring is a vital part of SHM of many structures, including bridges, which are a segment of the road network infrastructure. Hence, vibration analysis should be part of optical sensor solutions when long-term data gathering regarding road infrastructure is to be considered.

3.4. Pressure Monitoring in Road Infrastructure

Pressure within road infrastructures is another essential parameter for assessing structural integrity, ensuring the long-term durability of the structure and the materials used, and evaluating load-bearing capacities. If the road infrastructure is subjected to excessive or uneven pressure, then it can lead to pavement deformation, cracking, and eventually the failure of the structure or of its components. Therefore, the implementation of smart-sensor-based pressure-monitoring systems could allow for timely maintenance estimation and planning as well as improving on-road safety levels.

FBGs in particular can be used to monitor pressure in pavement structures. Kashaganova et al. [147] developed a road surface monitoring solution with an FBG-based sensor. Additionally, Rebelo et al. [148] studied and installed a pavement monitoring system, which was also based on FBG optical sensors. There, a system design was proposed in which measurements regarding the effects of vehicle-induced loads and temperature on pavement performance could be analyzed. Lastly, another recent study [135] showed structural design and optimization for road-use solutions with optical sensors. There, a radial pressure load was applied by adjusting the gradient loading displacement at a speed of 0.01 mm/min and a maximum loading displacement of 0.10 mm. Additionally, road infrastructure and its related components are not only measured by the direct embedding of the optical sensors within the pavement structure. Fontaine et al. [149] used distributed optical sensors and attached the optical fiber to the inner liner of the tire. There, a pressure load from 2800 to 4800 N was applied, reaching a relative error of 1% to 3%. Such an approach can also provide data on wheel load estimation for every wheel angular position.

Such solutions can ensure that FBG optical sensors can be effectively used to monitor pavement responses under different loading conditions, therefore providing important data in maintenance planning.

3.5. Displacement and Tilt Monitoring in Road Infrastructure

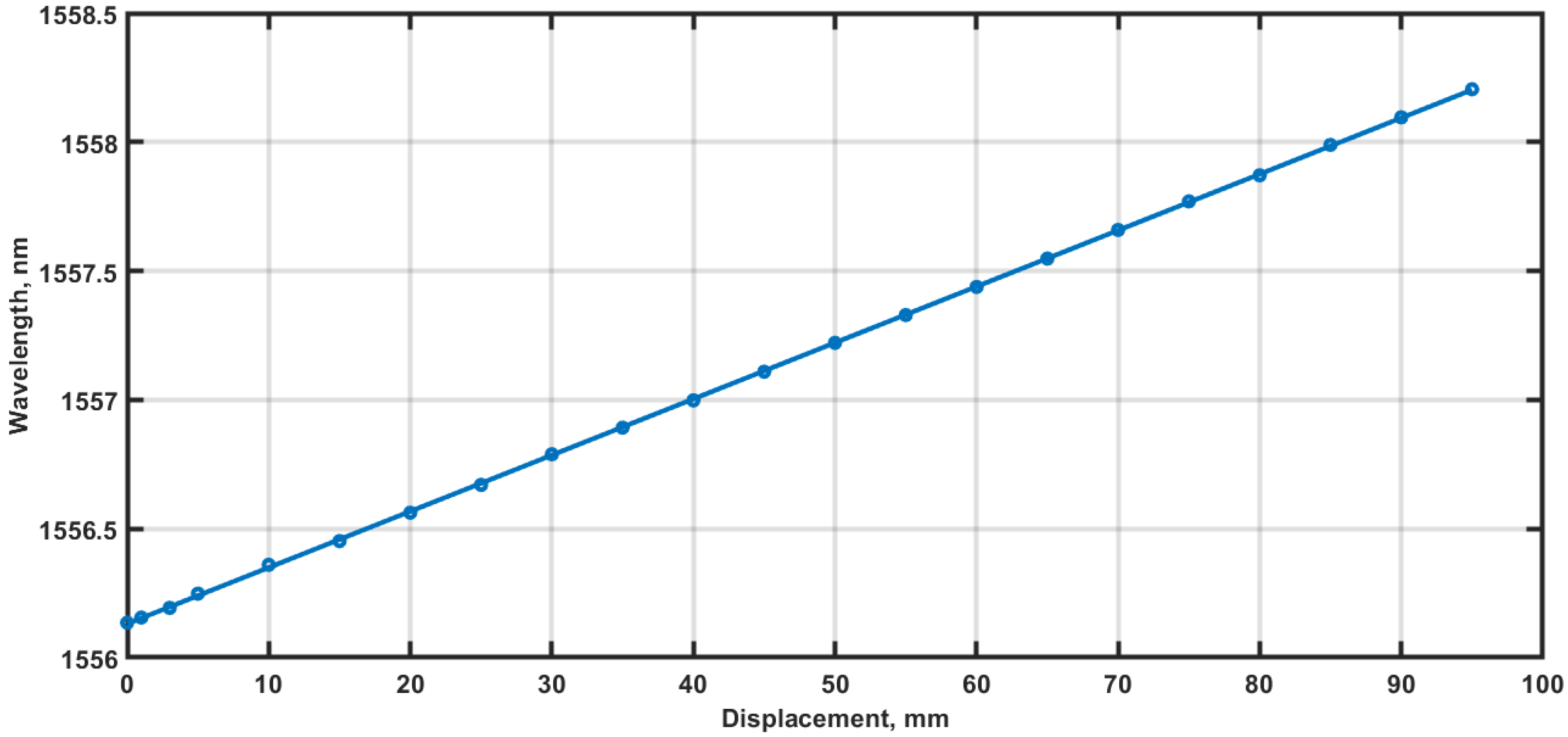

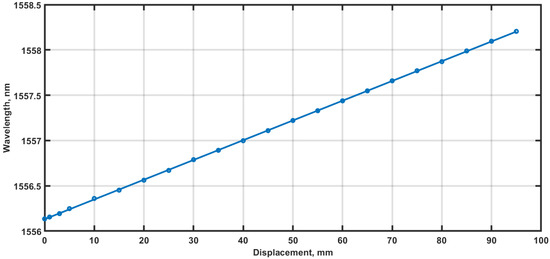

Monitoring of displacement and tilt in road architecture is also critical to ensuring the structural integrity of the pavement structure, as well as overall safety and infrastructure longevity, which are of the utmost priority. The detection of tilt can signal the rotational instabilities, uneven settlements, and deterioration of the pavement layers, while displacement can indicate processes such as lateral movements, heave, or subsidence in the pavement structure and materials. Proactive detection of such deformations can allow road infrastructure managers to ensure timely maintenance and potentially prevent car accidents caused by damaged road infrastructure or the complete failure of the road segment. Commercial FBG displacement sensors provide a measurement range typically from 0 to 100 mm and, in rare cases, 0 to 250 mm. A measurement wavelength vs. displacement curve is presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

The FBG displacement sensor’s Bragg wavelength changes with the displacement.

The data in Figure 12 reflect our own measured experimental characterization of the FBG-based displacement sensor. It shows the Bragg wavelength shift as a function of the applied displacement; however, the FBG responds to displacement through the strain induced in the grating. The pull-type displacement sensor incorporates an FBG ring-shaped fixator and a sliding measuring rod attached to the fixator ring via a spring. The spring allows the rod to retract to its starting position and provides a controlled, linear force to the fixator ring, transferring displacement to the FBG indirectly to extend the sensor’s measurement range and protect the FBG against excessive forces. When linear displacement is applied to the road, a certain tensile force is applied to the fixator ring via the spring. This tensile force (as displacement increases) is applied to the FBG, stretching it, thus causing its reflected wavelength to increase. The same casing of the sensor contains another FBG sensor used for the purposes of temperature compensation. A particular sensor provides a sensitivity of approximately 0.02181 nm/mm over the tested displacement range. The linear trend shown in Figure 12 reflects the strain–wavelength proportionality of the FBG under this configuration.

In a recent study [147], an FBG-based optical sensor was developed specifically for road surface monitoring. There, combinations of physical parameters such as stress, deformation, temperature, and displacement were monitored, reaching less than 0.1% nonlinearity errors, and the linear displacement changes that are proportional to temperature shifts in the range of −40 to 80 °C. Hence, this indicates the potential for a suitable solution in pavement structure displacement evaluation as well.

Tilt monitoring can also be used to gather important data on road pavement structures. For instance, ref. [150] showed FBG-based tiltmeter installation on bridge bearings to ensure dynamic rotational angle monitoring. Natural frequencies and mode shapes could be analyzed, highlighting the capability of the detection of rotational movements and the dynamic analysis of the infrastructure.

Additionally, distributed optical sensors can also be employed. The authors of [151] showed the use of distributed sensing techniques implemented for ground deformation monitoring. There, a single-mode optical fiber was used and implemented in a shallow trench to monitor ground surface deformation. Due to static and dynamic loads, strain variations could be captured, demonstrating the possibility of detecting subsidence or uplift in road subgrades, for example.

3.6. Humidity Monitoring in Road Infrastructure

Humidity monitoring for road infrastructure is a topical and urgent issue that ensures the structural integrity and safety of users, prevents premature degradation of layer structures, and improves maintenance plans. High increases in moisture can negatively affect pavement layers, exacerbate damage attained during the freeze–thaw process, and accelerate the degradation of material quality. Previously, humidity-based sensors have been used for environmental monitoring applications, yet recent studies regarding optical-fiber-based sensor solutions promote improved durability, integration capabilities, and sensitivity [152].

FOSs, such as FBGs, can be used for humidity parameter recording of the infrastructure, such as road infrastructure monitoring. The operation principle here is based on detecting changes in the refractive index of the applied hygroscopic coating [153] of the fiber that is being used. Thus, if the humidity levels fluctuate, then such shifts can also be correlated. Induced shifts in the Bragg wavelength can be calculated for precise humidity measurements. For instance, the analysis conducted by Mathew et al. [152] highlights the potential of optical-fiber-based humidity sensors, marking their advantages in harsh environments. Leone et al. [153] showed the development of a fiber-optic FBG thermo-hygrometer designed for soil moisture monitoring, which is also a relevant area for road infrastructure monitoring. In this research, a polymer micro-porous membrane was used to seal FBG, enabling the real-time monitoring of volumetric water content (VMC) in soils. This type of technological approach can also be beneficial to the assessment of the moisture measurements in subgrade layers of road pavement, contributing to the studies and the development of pavement longevity and performance.

Humidity-based optical sensors can also further advance intelligent transportation systems (ITS) and their development [19]. Incorporation of various optical sensors, such as temperature and humidity, in ITS solutions can be utilized for real-time data analysis and enhancement of traffic safety, especially under various weather conditions. Systems such as these can proactively support the determination of weather-induced road hazards and enable proactive traffic management by the responsible authorities.

4. Discussion—Potential for Next-Generation Smart Road Transportation Infrastructures

Based on the previous sections of this article, it is clear that road transportation infrastructure relies on different sensor technologies and various levels of large data. Therefore, it is safe to say that the next-generation road transportation will continue to advance to more smart-based solutions that integrate multiple high-level technologies together. One part of it is data gathering solutions for which FOS, such as FBGs and distributed FOS solutions [123], will be needed, yet other technologies are topical to be used to continue the improvements in the development and safety of road infrastructure. Some of those are digital twins (DTs), Internet of Things (IoT), and machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence solutions (AI). In the subsections of this section, we have discussed and analyzed the most relevant future developments on the path to full-scale smart road transportation infrastructure.

4.1. Fiber-Optical Sensors and Digital Twins in Road Infrastructure

DT-based systems are based on the concept of a dynamic, real-time virtual model that mirrors a physical asset, thus enabling enhanced monitoring, simulation scenarios, and predictive control across infrastructure and their lifecycles. Hence, such capabilities are also topical in transport infrastructure [154,155]. In road transportation infrastructure, DT can be used to depict the geometry of the pavement, its structural layers, and the geometry of the overall road; moreover, it can allow for the integration of the real-time data that are gathered by FOSs to ensure the synchronization of the physical and digital components and their alignments, as well as calibration necessities [155,156].

FOSs, such as FBGs or other distributed FOS systems that ensure, for instance, temperature or acoustic parameter measurements, can be specifically positioned to provide valuable data input for more precise DT systems and developed models. As such, FOS systems have high spatial resolution, long-range measurement coverage, immunity to electromagnetic interference, and durability when operating in harsh outdoor environments (e.g., weather changes). These sensor technologies can be specifically suitable in various locations and environments in which road infrastructures are being built and maintained [156,157,158,159]. One such example is long-range temperature and strain measurements of road infrastructures, allowing for the creation of temperature and strain profiles along tens of kilometers of road infrastructures. Therefore, detecting subsurface thermal or integrity events and anomalies could also indicate freeze–thaw cycles. Similarly, acoustic readings could provide large amounts of data for traffic-induced vibrations, vehicle movement, and structural strain impact on road infrastructures [158,159,160]. These are important considerations when developing accurate DT models.

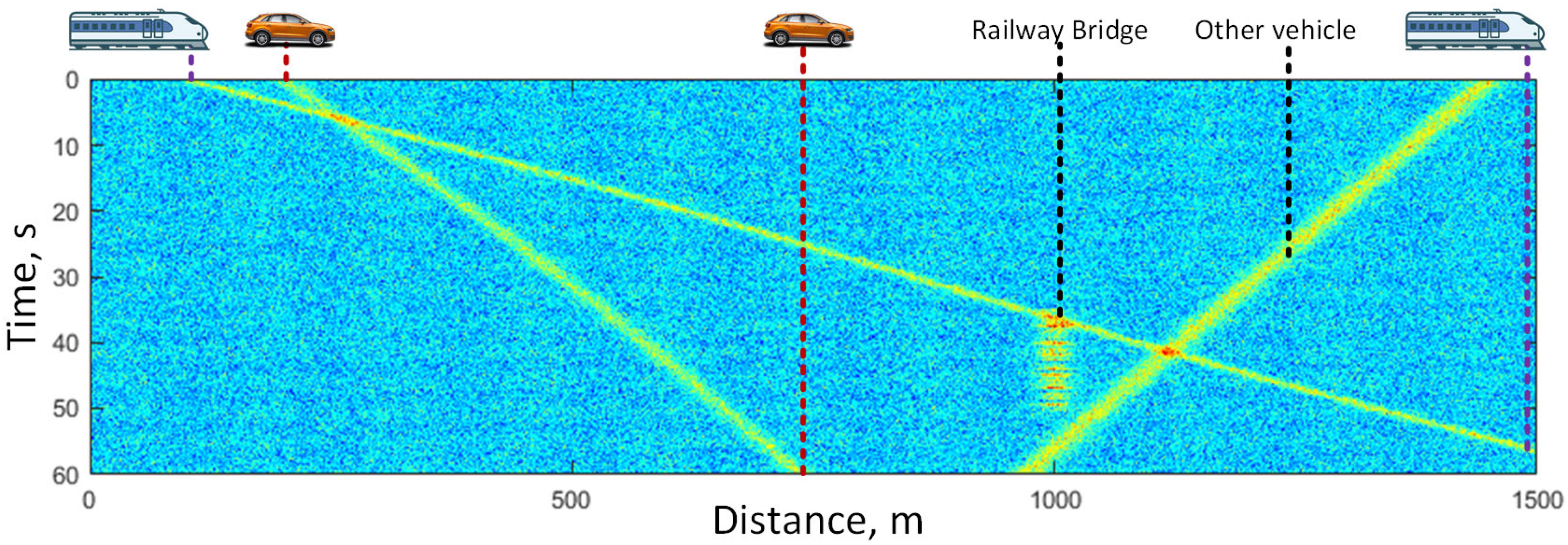

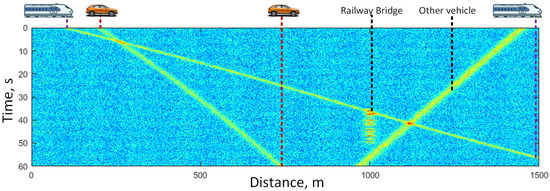

Integrating FOS data into the model of a DT can significantly add to the functionalities of road infrastructure applications. Real-time fiber-optic data can ensure a stream of information, supporting advanced DT capabilities, such as track-recorded historical diagnostics and continuous monitoring. A railroad example [161] highlights the potential of such a “neural system” in which APSensing deployed distributed FOSs for acoustic sensing; the gathered sensing data were input to a DT model, enabling it to support train tracking, anomaly detection, and historical-record-based acoustic data analysis (see Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Fiber-optical acoustic sensors for train tracking.

Figure 13 shows a time–distance acoustic heatmap obtained from the distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) system. The color scale represents the local amplitude of the acoustic signal along the fiber, plotted on a logarithmic scale, explicitly highlighting the varying strengths of vibration as trains travel along the track.

Given this, a similar approach could be made in the road context, in which road DT models could also be fed with FOS data. Such data would allow DTs to be updated swiftly with the changes in pavement integrity, while detecting the subsurface moisture and temperature changes and following dynamic load patterns and potential cracking.

For instance, research conducted by Wang et al. [158] demonstrated the use of fiber-optical sensors for monitoring traffic flow. The authors demonstrated a traffic-flow and speed monitoring system using a distributed acoustic sensing application in various environments such as cities, tunnels, and highways. From the fiber-optical acoustic signals, researchers were able to extract vehicle movement trajectories, providing data on trajectory tracking and traffic flow statistics; this information, when integrated in next-generation road DT models, could also dynamically update traffic-based data and infrastructure stress profiles.

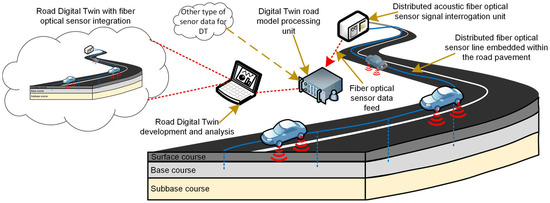

Hence, we have created a visual concept design of an FOS realization in road infrastructure, for which a road DT that has other types of data sensors could be correlated with embedded FOSs for even more in-depth data acquisition, analysis, and representation of a more realistic road DT model that observes the data from the layers of the pavement (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Concept of road fiber-optical sensor integration within the development of the road digital twin model.

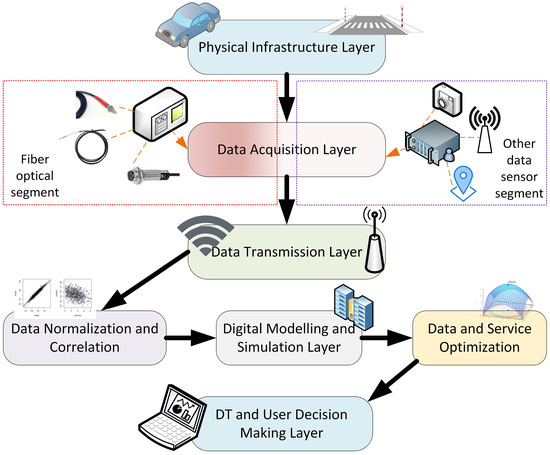

However, one of the main difficulties currently is the structuration of DT models and their architectures in correspondence to designing FOS and ensuring appropriate sensor data ingestion within the DT model. Some of the recent frameworks [156,162] for road infrastructure DTs propose segregated and layered models, in which there is typically a a physical infrastructure layer, a data acquisition layer (including various types of data sensors, such a cameras and others), a data transmission and fusion layer (normalization and correlation), a digital modelling and simulation layer, and service (optimization) and user decision-making layers. Adding the FOSs and its technological capabilities to the data acquisition layer (see Figure 15) would supplement the spatial awareness abilities, in addition to predictive maintenance and more realistic road-based application development and simulations, such as safety tests. Additionally, convergence with the other types of IoT applications and ML algorithms discussed in further subsections of this article could extend even further the smart road infrastructure segment.

Figure 15.

Digital twin layer segregation with the integration of fiber-optical sensor data acquisition and leading consequential impact.

Overall, some of the main challenges to effectively integrating FOSs within DT models remain. The most highlighted ones are the absence of unified standards, challenges in data interoperability, the necessity for a scalable approach and open frameworks, and long-term data for the most suitable embedding methods of the FOS within the road pavement infrastructure [154]. The DT field in road infrastructure and other related areas is commonly project-specific, meaning that changes are implemented from one type to another, as the lack of reference architectures remains. Additionally, concerns regarding data ownership and security should also be evaluated.

4.2. Fiber-Optical Sensors and Internet of Things (IoT) in Road Infrastructure

Another topical and prospective area regarding smart-based road solutions is the integration of FOSs within the network or IoT. Such technological emergence allows for the transformative potential of smart road infrastructure, where complex real-time data acquisition can be correlated and used for various applications and responsive analytics in road development, maintenance, and safety provision. FOS such as FBGs or distributed ones, for instance, based on stimulated Brillouin scattering (SBS), as well as distributed acoustic, temperature, strain, or other relevant physical parameter ones, offer high sensitivity, durability, and long-reach monitoring capabilities [163]. These advantages are exceptional for such road IoT frameworks. For instance, previous research carried out by A. R. Al-Ali et al. [163] used SBS-based distributed fiber sensing that had been successfully embedded in bridge monitoring systems, where strain data from FBGs and Brillouin sensors were transmitted via IoT channels to provide structural health diagnostics and early defect detection.

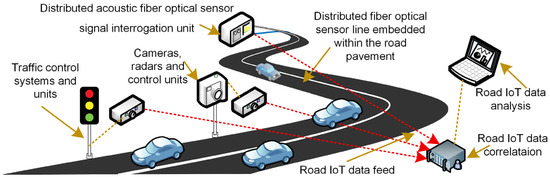

For the integration within the road IoT ecosystem, we have developed a visual concept of road FOS integration, along with the surface layer data acquisition tools and sensors used for road IoT applications (see Figure 16). Hence, merging the surface-level tools and methods together with the subsurface ones, such as the point of distributed FOSs, can lead to in-depth data gathering, allowing for advancing on next-generation smart road IoT solutions.

Figure 16.

Concept of road fiber-optical sensor integration within a road IoT solution.

In some configurations, IoT-enabled FOS systems can be used within a configuration where low-power microcontrollers and wireless modules are used for data processing and transmission. One of the related studies in this topic was performed by Herlin et al. [164] who studied geotechnical monitoring by using fiber sensors that were combined with an Arduino Uno R3 microcontroller to detect soil displacement and later ensure post-processing to issue early-warning notification, showing the feasibility of a low-cost embedded fiber-optical IoT monitoring platform in the field of civil infrastructure.

Increasing interest has also been seen in reducing maintenance costs and enhancing coverage distance for smart road and smart city applications [165]. FOSs offer such IoT systems additional advantages and capacity to support distributed passive sensor networks; this is especially the case in scenarios when thousands of point-based sensors are used for continuously collecting acoustic, strain, vibration, and/or temperature data across vast areas, and now can be replaced with distributed fiber-optical ones.

However, in such large-scale sensor networks, sensor identification, especially smart self-based sensor identification, can be challenging in supporting scalable IoT deployment. A study performed by Renner et al. [166] investigated the use of a unique FBG marker pattern that could embed an optical “address” into each fiber, ensuring that interrogation systems could provide automotive identification processes for sensor origin detection, thus allowing for sensor data reading integration within IoT-based data management systems by using Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture (OPC UA) protocol. Such an approach can also be topical in the field of smart road infrastructure, where IoT and FOS systems are to be used. Currently, the lack of unified standards for large-scale distributed sensing can partially be mitigated by adapting existing industrial data protocols such as OPC UA [166,167]. For instance, researchers should investigate approaches for adoption that surpass the simple collection of telemetry data and mapping of sensors. Information models consisting of sensor data, channel information, spatial data, and lengths could be transported via OPC UA PubSub (publisher-subscribed model) [168] or other means. Ladegourdie and Kua [167] discussed in detail the implementation principles and performance trade-offs. Ló pez-Castro et al. [169] have discussed another approach, which commonly is used in SHM/IoT monitoring solutions and therefore could possibly be applied in fiber-optical sensor monitoring solutions. The use of the Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) protocol can be planned for as a means for FOS data transport. Lastly, Zhou et al. [170] highlights the potential constraints regarding large datasets produced by distributed sensing; certain protocols and data model approaches should be adjusted, especially when accounting for different parameter collection approaches, such as those that are spatial, calibration-related, or compensation-related.

Based on the analyzed information, FOSs with IoT architectures offer vast capabilities for smart road infrastructure—enabling continuous and distributed physical parameter data recording, scalable FOS deployment and identification, as well as advanced-level analytics potential. Future research in this area must aim to resolve difficulties related to sensor interoperability, powering of optical interrogators, and their placement strategies, as well as large data handling and correlations, and the preparation of unified frameworks and standardization for FOS and IoT system integration in smart road applications.

4.3. Fiber-Optical Sensors and Machine Learning (ML)—Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Road Infrastructure

With the rise in topicality of ML and AI applications, such fusion with FOS sensing can assist in smart road infrastructure development and advancements. ML and AI can ensure the addressing of the key challenges inherent in the FOS system’s output data. For instance, the large amount of recorded data have to be processed. This includes data regarding physical parameters themselves and the quality and performance of the solution, such as noise estimation, cross-sensitivity, and others. Hence, efficient use can enhance optical signal processing, predictive analysis process, and anomaly detection.

A recent study conducted by Zhou et al. [171] shows that the use of ML and AI methods has become an important aspect of FOS system innovation. Particularly in the areas of advanced signal demodulation schemes, distributed sensing and data processing, and pattern recognition in various related applications. Similarly, Reyes-Vera et al. [172] and Venketeswaran et al. [173] investigated the ways in which modern ML and AI approaches overcome FOS constraints related to cross-sensitivity issues, signal drift, and high data throughput. Hence, there is potential to advance in making new real-time intelligent monitoring approaches for infrastructure monitoring and related applications.

An important study was recently conducted by Saha et al. [174] regarding smart road applications, where FBG sensors were used and embedded in the pavement structure to track strain and vehicle loads. Given that environmental temperature fluctuations can affect the precision of such measurements, the study used multi-array FBGs that were coupled with an ML solution to distinguish strain and temperature effects via supervised data-based learning, thus also improving the performance of this SHM application.

For distributed FOS-based systems, for instance, distributed acoustic sensors, ML techniques such as neural networks enhance real-time strain and vibration-induced signal data interpretation. For example, artificial neural networks (ANNs) surpass traditional algorithms in accuracy and processing speed when dynamic distributed FOS data are evaluated. As for the noise processing in long-range signal transmission, the application of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) could be examined, which is also relevant for road-based monitoring systems [172,175].

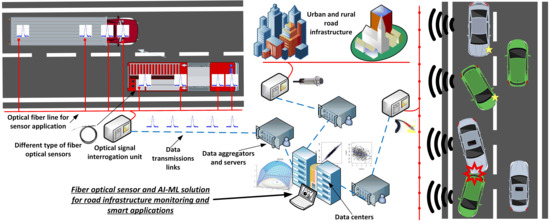

We have accordingly developed a concept for FOS convergence with ML and AI solutions to improve on-road infrastructure monitoring capabilities further (see Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Concept of road fiber-optical sensor convergence with ML and AI applications.

Given the vast amount of sensor-measured data, their diversity, measuring distance, field of measurement, and application, a large amount of these data, or big data, can be processed, correlated, and analyzed more conveniently, allowing for the optimization of sensor performance and developing more advanced solutions and monitoring capacities. Future directions for this innovation should emphasize the integration of ML-enhanced FOS data streams into predictive maintenance modules to develop resilient, adaptive road-based smart systems.

4.4. Fiber-Optical Sensors and Quantum-Technology-Based Sensors in Road Infrastructure

Another exploitable approach is the fusion of classical FOSs and quantum technologies, opening a new perspective in infrastructure monitoring, further extending the precision, reliability, and multifunctionality of the sensing solution.

Quantum sensing techniques and tools, especially those utilizing the quantum light sources and designs, elevate FOS capabilities. When employing quantum fiber sensors that are built upon interferometer architecture and technologies, such as Michelson, Mach-Zehnder, or Sagnac, an ultra-precise detection of physical parameters like temperature, strain, and curvature can be reached, reaching sensitivity levels beyond those provided by classical FOSs. For instance, recent studies have shown that single-photon interferometer-based fiber-optical temperature sensors can ensure temperature resolution as high as 0.029 °C while surpassing shot-noise limitations [176,177].

Recently studied frameworks propose integration between distributed FOSs and quantum communication within a unified infrastructure. One of such examples is integrated sensing and quantum networks (ISAQN) [178], which can ensure both secure communication by using CV-QKD protocols and distributed vibration sensing with a nano-level strain resolution (~0.50 nε/√Hz) and overall spatial resolution of ~0.20 m. Such an approach could potentially be applied in certain smart road applications, where both infrastructure health monitoring and cryptographic resilience are established.

Regarding road infrastructure, quantum-enhanced fiber-optical systems also offer a transformative approach for potential improvements. High-resolution quantum sensing can lead to detection capabilities of micro-cracking, more precise pavement fatigue estimation, or large-scale thermal variation detection before conventional methods and tools register the induced changes, hence contributing to proactive maintenance. For instance, Kantsepolsky and Aviv [179] discussed integrating quantum magnetometers and quantum gravimeters into traffic management systems to ensure real-time data on vehicle movements, traffic density, and congestion patterns. Also, quantum accelerometers and quantum strain gauges were analyzed as a solution for continuous monitoring and detection of structural defects in transportation infrastructure. Such systems can complement FOS networks that already monitor strain, vibration, temperature, and other parameters of road structures.

Additionally, the U.S. Department of Transportation recently published a report on Quantum Technologies in Transportation Workshop [180], which highlights that quantum sensing is closing in on near-term deployment. Given the technological advantages such as self-calibration capabilities, long-term stability potential, and reduced power consumption, quantum-based sensors can be particularly topical in the monitoring of pipelines, bridges, and roadways. Thus, when deployed alongside classical FOS and their interrogation units, quantum sensor-based devices could provide layered and hybrid sensing approaches to establish a smart road framework.

However, challenges still need to be resolved, and real-case implementations are currently relatively limited. For instance, quantum-based sensing implementations include high-cost quantum-level detectors, and the interferometric stability should also be investigated further. Additionally, research on integration within complex dynamic road environments can be challenging, given the vast environmental and user-induced influences. To achieve robust, cost-effective quantum fiber setups suitable for routine road infrastructure deployment, the authors suggest several future research areas, such as designing quantum interferometric sensors that are tailored for road stress, temperature detection, and subsurface anomaly evaluation. Another one is the study of a hybrid approach in which classical FOSs ensure wide-range measurement, while quantum-based sensors pinpoint the precision. Lastly, further investigation of the hybrid quantum network architectures and distributed FOS arrays is needed, especially when the most suitable deployment protocols are studied.

5. Conclusions