Autofocusing Method Based on Dynamic Modulation Transfer Function Feedback

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Automatic Focus Method Based on Dynamic MTF Feedback

2.1. Image Evaluation Methods

- Edge detection: detect prominent edges in the image using the Canny operator;

- Edge Spread Function (ESF) calculation: compute the gradient magnitude along the edge direction to obtain the ESF:Here, I(x) denotes the grayscale value at the edge position, and x is the positional coordinate.

- Line Spread Function (LSF) calculation: differentiate the ESF to obtain the LSF:

- LSF normalization: normalize the LSF to unit area:

- Optical Transfer Function (OTF) calculation: perform a Fourier transform on the normalized LSF to obtain the OTF:

- MTF calculation: take the modulus of the OTF to obtain the MTF:

2.2. Search Algorithms

- Determine the initial search space for PSO: Based on the designed focal length value f0 of the tested optical system and the tolerance range δ, provide the possible minimum fmin and maximum fmax of the focal length as the initial search space for PSO: [fmin, fmax]fmin = f0 × (1 − δ)where δ denotes the mechanical adjustment tolerance (typically taken as 0.05–0.1).fmax= f0 × (1 + δ)

- Set the PSO algorithm parameters to include:(a) Particle number M: set to 20–50;(b) Inertia weight w: initialized at 0.9 and decreased linearly to 0.4;(c) Learning factors c1 and c2: set to 2;(d) Random numbers r1, r2: take values in the range 0–1;(e) Maximum number of iterations N: set to 50–100 iterations.

- Particle initialization: Particle positions are initialized as , where denotes the particle index; particle velocities are initialized as

- Calculate particle fitness: compute in real time and record the MTF values of the image at the positions of all particles in the current iteration. Select the MTF value at the Nyquist frequency fNyquist as the particle fitness; its calculation function is:Here, denotes the position of the i-th particle at the t-th iteration, is the MTF value of the image at that position under the Nyquist frequency, and d is the pixel size of the image sensor.

- Set the initial individual best and the global best :

- Iterative update (assuming iteration t to t + 1, where ): after obtaining the fitness values of all particles at the current iteration t + 1, the individual best value and the global best value among particles at iteration t + 1 are identified by comparison and recorded. Their update formulas are as follows:Here, the fitness value of the current position is compared with the historical best ; if the current one is superior, is updated to the current position; otherwise the original value is retained. Then, all particles, are iteratively traversed and the position with the maximum fitness is selected as the new global optimum; if multiple particles share the same optimal fitness value, the position of the first particle is preserved.

- Update particle information: During each iteration, continuously update the velocity and position of the current particles. The update formulas for velocity and position are as follows:

- Convergence criterion: Terminate when the maximum number of iterations is reached, or when the change in the population best value falls below a threshold (e.g., 1%). Record the optimal interval [fleft, fright]; the computation is given by the following formula:

- Interval partitioning: Within the interval [fleft, fright] produced by PSO, select two points according to the golden ratio:

- Iteratively narrow the interval: compare the MTF values of the images acquired at the positions fa and fb, and retain the interval on the side with the larger MTF value;

- Repeated subdivision of the new point: continue until the interval length is less than the precision threshold, typically set to 0.1% of the focal length range;

- Record the optimal focus position f: compare the MTF values of the images acquired at positions fa and fb, and select the position with the higher MTF value as the optimal focus position f.

3. Experimental Validation and Result Analysis

3.1. System Design

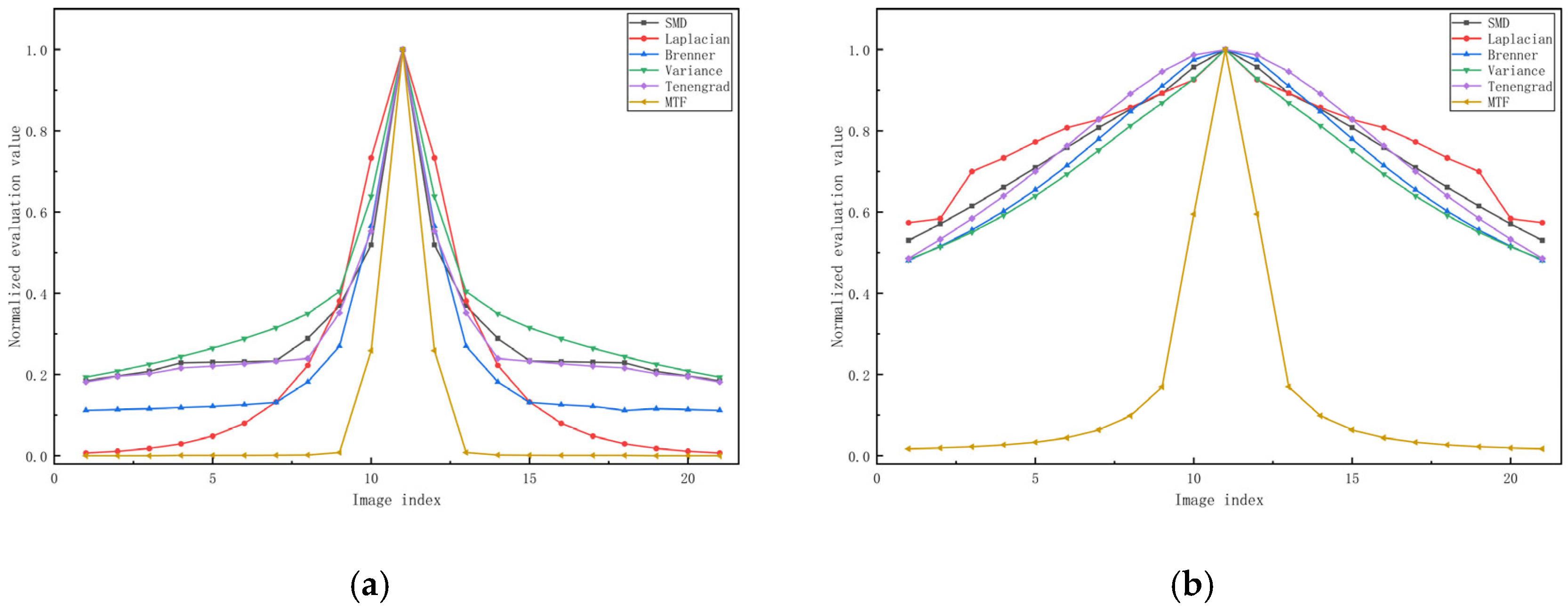

3.2. Image Evaluation Function Experiments

3.3. Repeatability Testing of Autofocus Algorithm

3.4. Efficiency Experiments of the Autofocus Algorithm

3.5. MTF Measurement Accuracy Experiment

3.6. MTF Measurement Repeatability Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hung, J.; Tu, H.; Hsu, W.; Liu, C. Design and Experimental Validation of an Optical Autofocusing System with Improved Accuracy. Photonics 2023, 10, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, F.; Cai, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z. Design of focusing mechanism for long array focal plane with heavy load. Infrared Laser Eng. 2021, 50, 20210270. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Al Rahman, M.; Mousavi, A. A review and analysis of automatic optical inspection and quality monitoring methods in electronics industry. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 183192–183271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.F.; Park, K.; Wijesinghe, R.E.; Jeong, H.; Han, S.; Kim, P.; Jeon, M.; Kim, J. Fast industrial inspection of optical thin film using optical coherence tomography. Sensors 2016, 16, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agour, M.; Falldorf, C.; Bergmann, R.B. Spatial multiplexing and autofocus in holographic contouring for inspection of micro-parts. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 28576–28588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebuffi, L.; Kandel, S.; Shi, X.; Zhang, R.; Harder, R.J.; Cha, W.; Highland, M.J.; Frith, M.G.; Assoufid, L.; Cherukara, M.J. AutoFocus: AI-driven alignment of nanofocusing X-ray mirror systems. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 42067–42082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Li, Y.; Ye, X. A rapid autofocus method for precision visual inspection systems based on YOLOv5s. Chin. Mech. Eng. 2025, 36, 864–872. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H. Deep Learning-Based Dynamic Region of Interest Autofocus Method for Grayscale Image. Sensors 2024, 24, 4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Bai, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Kuang, C. High-accuracy differential autofocus system with an electrically tunable lens. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 2789–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Zhang, X.; Tu, D. Autofocus methods based on laser illumination. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 29465–29479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, W.; Tan, F.; Jing, X.; Hou, Z.; Wu, Y. Automatic focusing of cassegrain telescope based on environmental temperature feedback. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2021, 29, 1832–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, E.; Cao, Y.; Shi, J.; Chang, B.; Zhang, J. Design of compact dual-field lens for visible light. Infrared Laser Eng. 2021, 50, 20210042. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, X.; Dai, J.; Yang, M.; Huang, S.; Chen, X.; Hou, Z.; Huang, J. A Review of Domestic and International Research on Focusing Mechanisms and Development Trends. Infrared 2023, 44, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Sang, Q. No-reference image quality assessment combining convolutional neural networks and deep forest. Prog. Laser Optoelectron. 2019, 56, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Sun, J.; Han, X. Image sharpness assessment and variable-step fusion autofocus method. Infrared Laser Eng. 2023, 52, 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, W. Automatic compensation for defects of laser reflective patterns in optics-based auto-focusing microscopes. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 2034–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Gu, N.; Xu, H. An autofocus evaluation function adaptive to multi-directional grayscale gradient variations. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2022, 59, 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Liu, C.; Huang, X.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Z. Automatic focus-search algorithm for primary focus determination assisted by MTF. Acta Photonica Sin. 2014, 43, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; Han, C.; Li, K.; Tu, H. An Improved Gradient-Threshold Image Sharpness Assessment Algorithm. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2021, 58, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. An auto-focus algorithm of fast search based on combining rough and fine adjustment. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 468, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Zhang, C.; Wu, N.; Zhou, J.; Guo, Z. Autofocus algorithm using optimized Laplace evaluation function and enhanced mountain climbing search algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 10299–10311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Feng, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, B. Microscope autofocus method based on image evaluation. Adv. Laser Optoelectron. 2023, 60, 305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H.; Yu, F. Automatic focusing algorithms for digital microscopes. Prog. Laser Optoelectron. 2021, 58, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Yuan, D. Study on image sharpness evaluation method based on wavelet transform and texture analysis. J. Instrum. 2007, 8, 1508–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sun, H. Abnormality Detection and Quality Diagnosis in Surveillance Video. Comput. Appl. Softw. 2016, 33, 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X. Analysis and Improvement of Digital Refocusing Sharpness Evaluation Functions in Light Field Imaging. Optoelectron. Technol. Appl. 2015, 30, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, J. A Review of Image-Processing-Based Autofocus Techniques. Laser Infrared 2013, 43, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi, M. A focus measure using entropies of histogram. Pattern Recognition. Letters 1998, 19, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Hu, Z.; Du, Z.; Meng, X. An Improved Sobel Gradient Function for Autofocus Evaluation. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2017, 43, 234–238. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, W.; Piao, Y.; Yue, W. Analysis of Edge Method Accuracy and Practical Multidirectional Modulation Transfer Function Measurement. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, L.; Yan, B. Study on microscopic image clarity assessment algorithm based on the Variance-Brenner function. Equip. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 10, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Average Focusing Time (ms) | Number of Focusing Failures |

|---|---|---|

| Proposed method | 4450 | 0 |

| Traditional Method | 8550 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fang, Z.; Song, Y.; Han, B.; Wang, A.; Song, J.; Yue, H. Autofocusing Method Based on Dynamic Modulation Transfer Function Feedback. Photonics 2026, 13, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020107

Fang Z, Song Y, Han B, Wang A, Song J, Yue H. Autofocusing Method Based on Dynamic Modulation Transfer Function Feedback. Photonics. 2026; 13(2):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020107

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Zhijing, Yuanzhang Song, Bing Han, Anbang Wang, Jian Song, and Hangyu Yue. 2026. "Autofocusing Method Based on Dynamic Modulation Transfer Function Feedback" Photonics 13, no. 2: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020107

APA StyleFang, Z., Song, Y., Han, B., Wang, A., Song, J., & Yue, H. (2026). Autofocusing Method Based on Dynamic Modulation Transfer Function Feedback. Photonics, 13(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020107