Abstract

Achieving high-precision 3D reconstruction of highly reflective objects remains a major challenge in structured light measurement due to local overexposure and fringe degradation caused by specular reflections, which destabilize phase retrieval and reduce reconstruction accuracy. To address this problem, we propose an enhanced structured-light reconstruction network, FaNIC-Net, enabling robust feature extraction and fringe restoration under strong reflective interference. FaNIC-Net comprises two complementary modules: a Frequency-aware Multi-scale Convolution (FaMC) module that embeds DFT/IDFT operations into a multi-scale convolution pipeline to enhance critical frequency components and preserve fringe periodicity, and a Nearest-Neighbor Interpolation Convolution (NIC) module that decouples resolution enhancement from convolution, effectively mitigating checkerboard artifacts and improving high-frequency texture continuity. Experiments on real and synthetic datasets demonstrate that FaNIC-Net outperforms state-of-the-art methods in terms of MAE and SSIM, achieving superior depth recovery particularly in severely reflective regions, thus providing a robust and generalizable solution for fringe degradation on high-reflective surfaces.

1. Introduction

High-precision three-dimensional reconstruction of highly reflective objects constitutes a crucial yet challenging problem in the field of Structured Light (SL) measurement [1]. In a typical SL system, encoded fringe patterns are projected onto the target surface, where they are modulated by the object’s reflectance characteristics and subsequently recorded by a camera. Depth information is then recovered through phase demodulation [2] and triangulation [3]. However, the reliability of this procedure strongly depends on the integrity and distinguishability of the fringe patterns within the captured images. Once the fringe deformation is severely corrupted, the accuracy of phase retrieval and 3D reconstruction degrades accordingly.

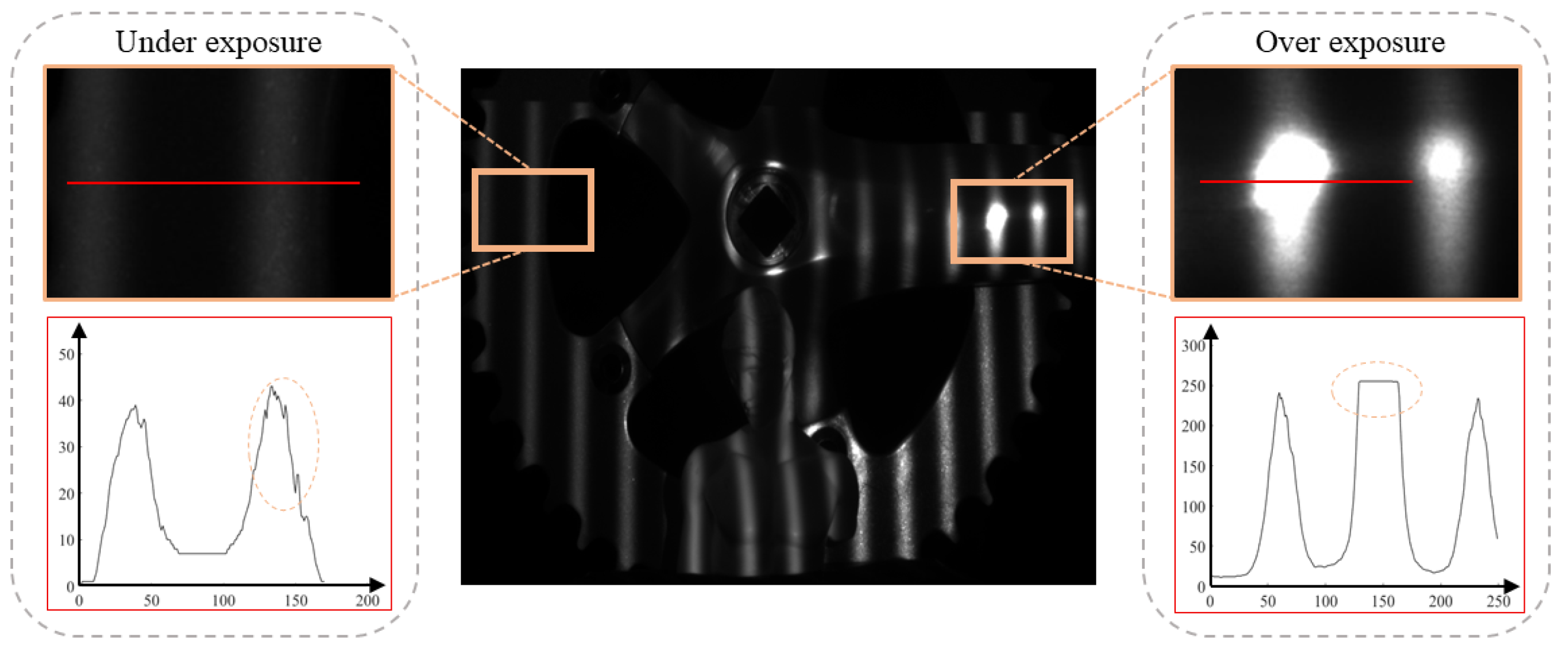

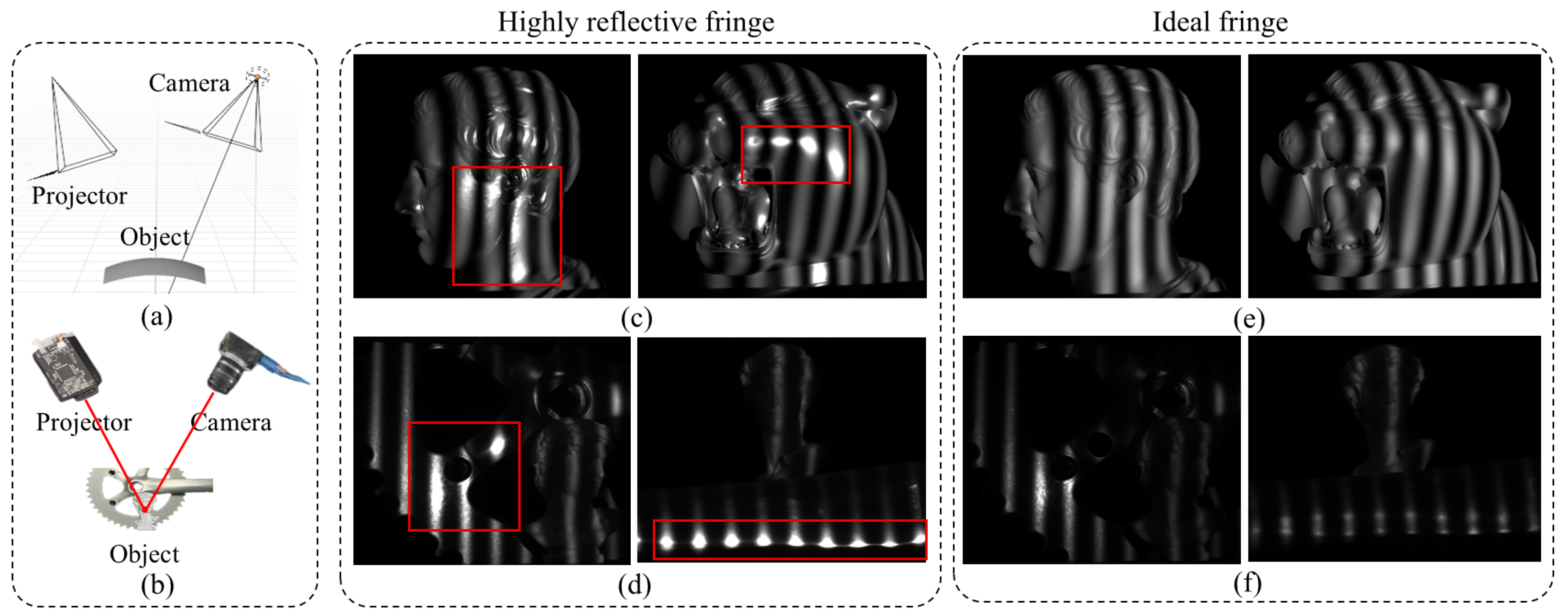

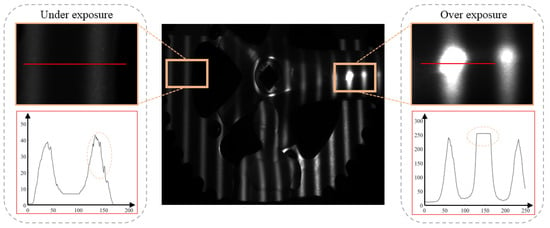

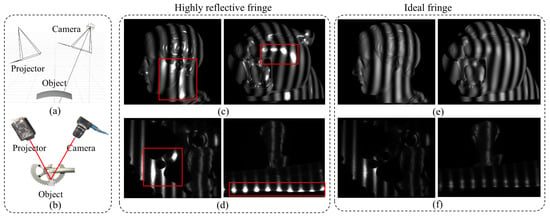

For diffuse or moderately reflective surfaces, SL systems typically achieve robust phase inversion and high reconstruction accuracy. In contrast, on metallic, electroplated, or mirror-coated surfaces, specular reflection causes severe local overexposure or even complete loss of fringe patterns, disrupting the spatial texture and frequency structure of the projected sinusoidal illumination. This instability in phase extraction leads to a significant reduction in reconstruction accuracy [4]. As illustrated in Figure 1, the projected sinusoidal fringes on a highly reflective surface suffer from two typical exposure distortion modes: underexposure and overexposure. The middle image shows an example of an acquired fringe pattern where non-uniform surface reflectance results in pronounced spatial fluctuations in fringe intensity. The left magnified region corresponds to an underexposed area, where fringe contrast becomes extremely low and gray intensities remain within a narrow dynamic range, causing irreversible loss of phase transition information. Conversely, the right magnified region demonstrates overexposure, where saturated highlight responses produce “fringe discontinuities” or plateau-like saturation segments, destroying the sinusoidal distribution and compromising accurate phase computation. Therefore, it is of great significance to develop fringe restoration or enhancement methods with strong high-dynamic-range adaptability to mitigate the exposure-induced phase distortion and improve the robustness and practicality of SL-based 3D measurement for highly reflective surfaces.

Figure 1.

Example of projected fringe distortion on a highly reflective surface. The left amplification area at the red line shows insufficient exposure and serious attenuation of stripe contrast, while the right amplification area shows overexposure, saturated highlight response and discontinuous stripes.

Traditional solutions mainly fall into three categories: surface extinction processing [5], optical hardware assistance [6], and multi-exposure imaging fusion (MIF). Extinction processing typically sprays matte coating or white powder onto the surface to reduce reflectance; however, this method is intrusive, irreversible, and impractical for high-value industrial components. Optical auxiliary methods incorporate polarizers [7] or spectral filters into the projection or imaging path to suppress specular reflection, but these approaches suffer from complicated calibration and reduced flexibility. Multi-exposure [8] and adaptive projection strategies [9] capture multiple images under varied exposure settings and fuse them to compensate for saturated regions, yet their reliance on repeated acquisition limits real-time performance. Consequently, how to recover or complete degraded fringe structures without auxiliary hardware and without altering the surface state has become a key research focus in SL-based 3D reconstruction [10].

With the rapid advancement of deep learning, researchers have increasingly integrated deep neural networks into SL fringe restoration tasks. Yu et al. [11] proposed a CNN-based FMENet that employs a Fringe Modulation Enhancement Module (FMEM) to convert two low-modulation phase-shifted images into three high-modulation counterparts, thereby enabling high-quality 3D reconstruction even under uneven surface reflectance. Zhang et al. [12] further designed a CNN architecture for robust phase extraction under low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and saturation. Wu et al. [13] integrated a U-Net with dynamic phase measuring deflectometry to reconstruct accurate shapes from single distorted orthogonal fringe images. Similarly, Dang et al. [14] combined U-Net and physics-based polarization modeling to suppress highlight-induced nonlinear errors. Liu et al. [15] introduced a single-shot SL measurement method with a novel exposure evaluation metric and proposed the SP-CAN network to enhance image details while preserving phase consistency. Song et al. [16] developed DcMcNet, a lightweight network incorporating deformable convolution and multi-scale fusion to restore saturated sinusoidal and Gray-code patterns. Cao et al. [17] proposed a lightweight Transformer–CNN architecture, TC-Net, which achieves real-time phase recovery for high-dynamic-range scenes through dual attention mechanisms and an efficient transformer module. It significantly improves inference speed while maintaining high accuracy, providing an effective and practical solution for HDR fringe-projection reconstruction. Despite these advances, conventional convolutional architectures [18] still struggle to capture critical structural cues under heavy fringe saturation. The widely used traditional networks also encounter limitations, including blurred texture representation, insufficient physical constraints, and weak robustness to intense specular reflectance, ultimately hindering high-precision phase and depth reconstruction.

To address these challenges, this work proposes a novel Frequency-aware and Nearest-Interpolation Convolution Network (FaNIC-Net) composed of two complementary modules tailored for feature extraction and reconstruction under strong reflectance interference:

(1) A Frequency-Aware Multi-scale Convolution (FaMC) module, which explicitly integrates the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) [19] and its inverse (iDFT) within a multi-scale convolutional pipeline. By decomposing and enhancing essential frequency components across scales, FaMC effectively preserves the inherent periodic structure of fringes while suppressing high-reflectance noise, improving texture fidelity.

(2) A Nearest Interpolation with Convolution (NIC) module, which replaces traditional transposed convolution during upsampling. By decoupling spatial resolution enlargement from feature extraction, NIC alleviates checkerboard artifacts and ensures better spatial continuity, particularly beneficial for restoring high-frequency fringe distortions.

Together, these modules provide both frequency-domain awareness and structural consistency, significantly improving robustness in fringe restoration for highly reflective surfaces and supporting high-quality 3D reconstruction.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We propose an enhanced deep-learning framework for SL-based 3D reconstruction of highly reflective objects, demonstrating strong applicability and generalization capability under severe exposure degradation.

- We introduce the FaMC module, which embeds frequency-domain modeling to reinforce responses to periodic fringe structures and improve feature separation and restoration under complex spectral interference.

- We design the NIC module, an innovative upsampling strategy that eliminates checkerboard artifacts and enhances structural continuity and texture representation within high-frequency fringe regions.

2. Principle

SL three-dimensional reconstruction adopts an active projection strategy in which a projector casts pre-designed encoded fringe patterns onto the target object’s surface, while a camera synchronously captures the deformed patterns modulated by the object’s geometry and reflectance [20]. The projected patterns are typically displayed in a temporal sequence and serve as temporarily imposed surface textures, enriching geometric cues and significantly enhancing feature extraction and correspondence establishment, particularly for texture-deficient regions. By analyzing the spatial displacement or phase shift of the captured fringe patterns, the spatial correspondence between the projector and camera can be robustly estimated, enabling high-precision 3D geometry recovery and yielding dense depth maps or point clouds.

In recent years, numerous SL encoding and decoding strategies have been proposed to improve the accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency of three-dimensional reconstruction. Among them, Gray-code encoding [21] and Phase Shifting [22] have become mainstream in high-precision SL systems due to their unique encoding capability, strong noise immunity, and sub-pixel depth reconstruction accuracy. In particular, the hybrid scheme formed by combining Gray-code’s global indexing ability with the Four-step Phase Shifting strategy [23] provides robust phase unwrapping and consistent reconstruction quality even under complex reflectance conditions, weak textures, and environmental disturbances. Therefore, this hybrid encoding scheme is adopted as the core projection strategy in our SL system.

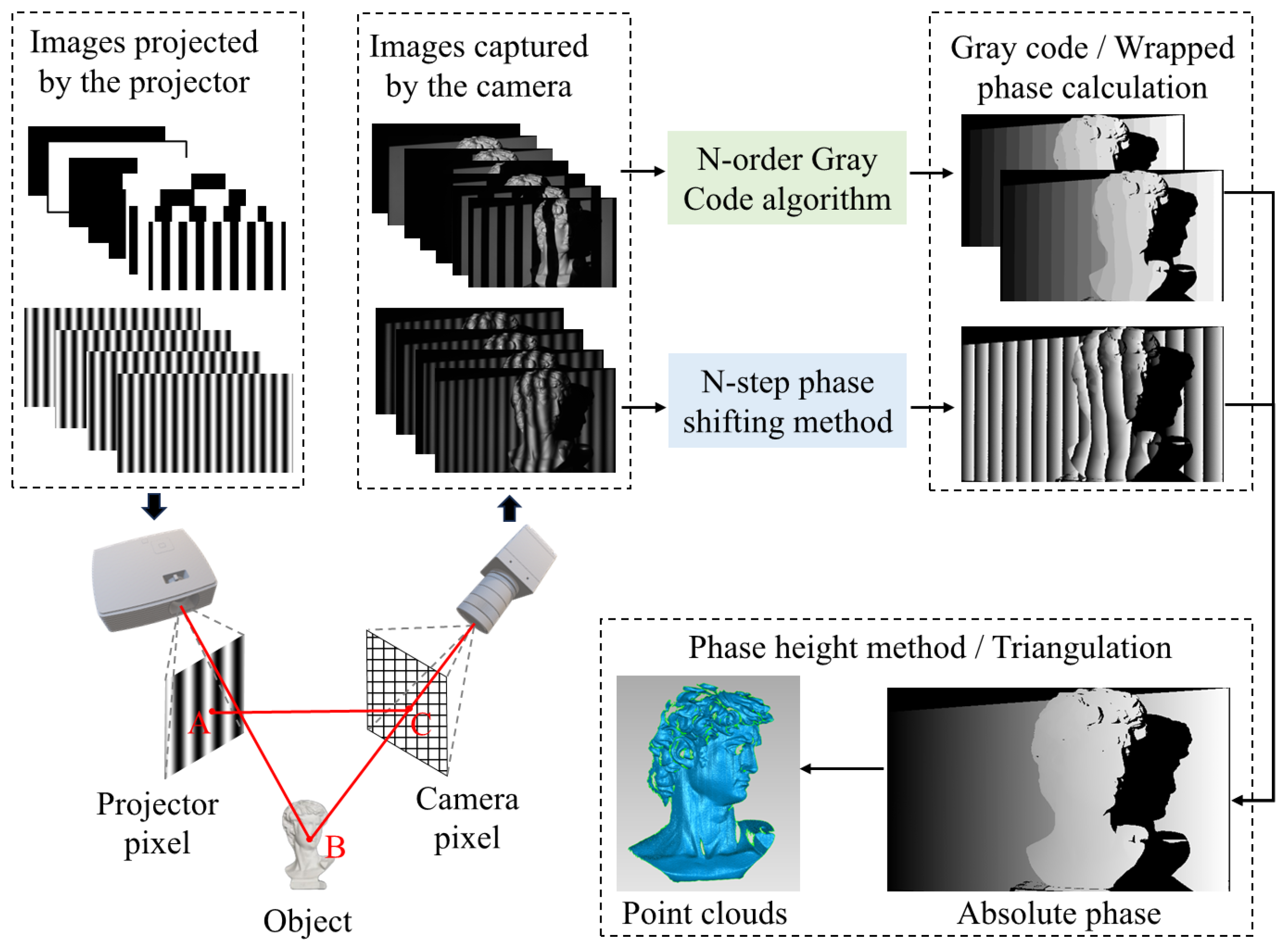

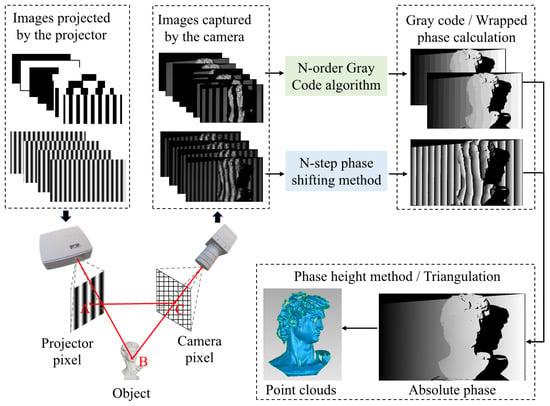

As illustrated in Figure 2, the projector sequentially projects multiple Gray-code patterns and phase-shifted sinusoidal fringes (upper left), and the camera synchronously records the corresponding reflected images (upper middle). The N-bit Gray-code sequence is first decoded to obtain a global fringe index, while the N-step phase-shifting method is employed to compute the wrapped phase (upper right). These two components jointly enable the construction of the absolute phase, which is subsequently converted into dense 3D point clouds via the phase-height/triangulation model (lower right). This encoding–decoding pipeline ensures globally unique pattern indexing and sub-pixel depth accuracy, providing a reliable phase foundation for the robust fringe restoration and reconstruction framework proposed in this work.

Figure 2.

The principle of structured light 3D reconstruction based on the Gray code and phase shift method.

2.1. Encoding Strategy

Gray-code encoding is a spatial encoding method in SL, using a sequence of binary black–white patterns to index the surface points with strong resistance to occlusion and mismatch. Each projected pixel is uniquely encoded through the Gray sequence, establishing an initial mapping between the projector and camera coordinates.

In contrast, the four-step phase-shifting method is a temporal encoding strategy designed to capture the same sinusoidal fringe with phase offsets, enabling high-precision phase retrieval. Four sinusoidal fringe images with successive phase shifts of are projected, and the captured intensity at pixel is expressed as follows:

where denotes the background illumination, the modulation amplitude, and the fringe phase to be recovered. The wrapped phase is computed as follows:

which yields a wrapped solution in the interval , subject to phase unwrapping to obtain the absolute phase.

2.2. Phase Unwrapping and Depth Recovery

The integer fringe order obtained from Gray-code decoding provides the coarse phase index, which is then combined with the wrapped phase from phase shifting. Let denote the Gray-code-derived fringe period index; the absolute phase is given by

Based on the calibrated system geometry, the absolute phase is then mapped through the triangulation model to recover the 3D coordinates of each pixel on the object surface.

Overall, Gray-code encoding provides reliable pixel-level global indexing, while phase shifting refines surface geometry to sub-pixel precision. Their complementary nature yields a robust and high-accuracy SL reconstruction framework. Even when facing complex surface reflectance, partial occlusions, and locally saturated highlights, this hybrid encoding scheme maintains stability and anti-interference capability, offering a solid foundation for subsequent fringe restoration and 3D reconstruction components proposed in this work.

3. Network

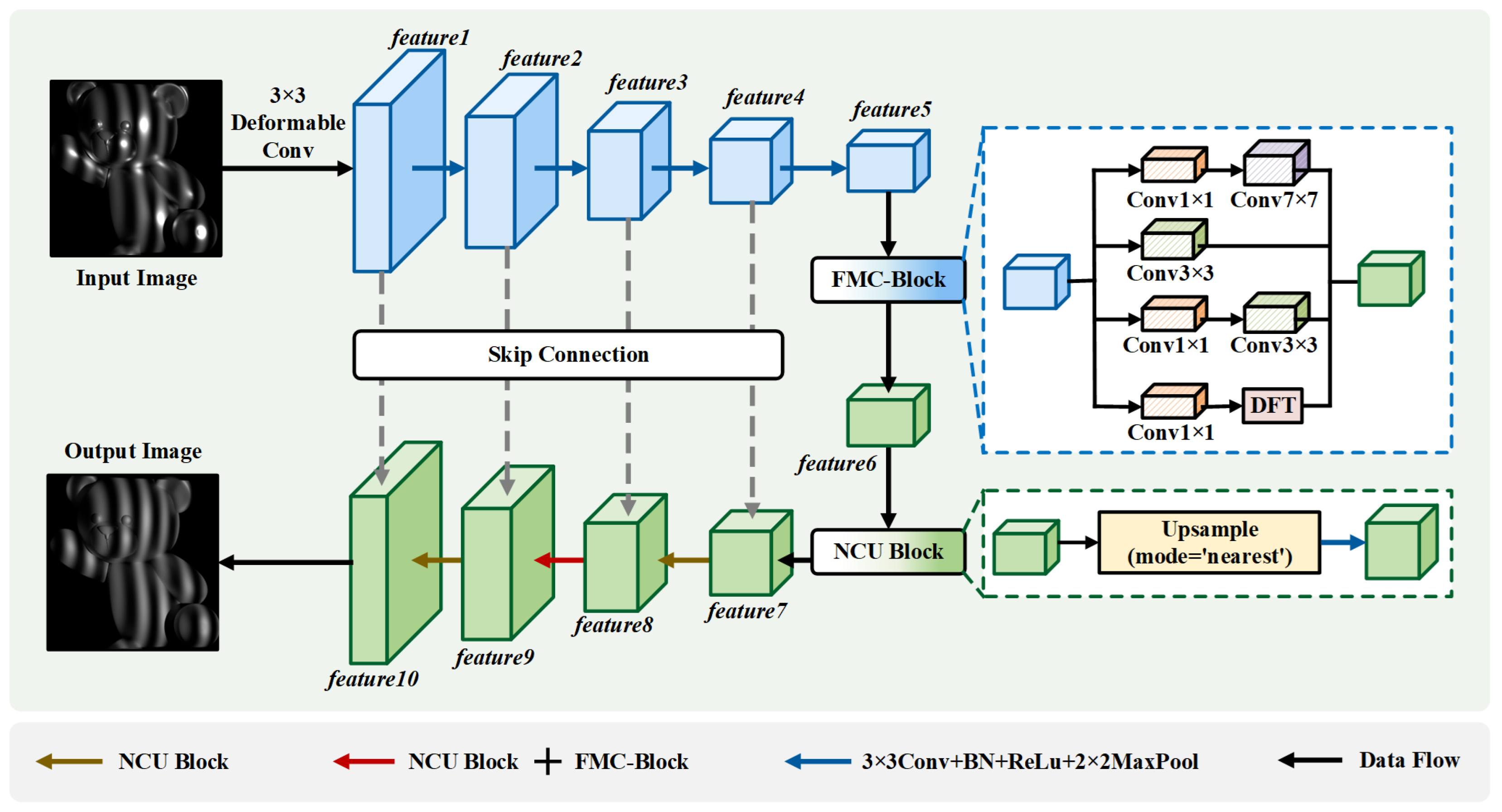

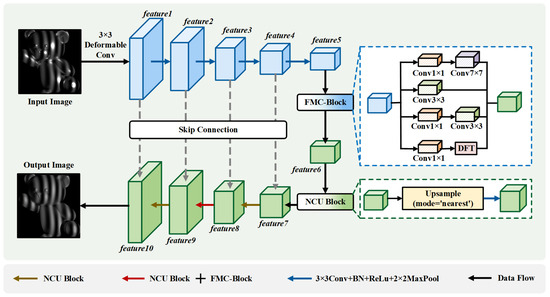

To enhance the representational capacity and restoration robustness of structured-light fringe images under strong specular reflection, this study proposes an end-to-end phase restoration network based on an encoder–decoder architecture. The overall framework is illustrated in Figure 3. The key idea is to strengthen the restoration of fringe patterns in complex reflective environments by integrating multi-scale frequency-domain modeling with spatial structural continuity enhancement.

Figure 3.

Overall architecture of the proposed end-to-end phase restoration network, which integrates the FaMC module and the NIC module to enhance fringe restoration under strong specular reflection.

It is worth noting that FaNIC-Net takes as input a single distorted fringe image containing saturated or specular-degraded regions, and aims to restore its ideal sinusoidal form without requiring multi-exposure or auxiliary coding.

The network is primarily composed of two core modules: (1) a FaMC module designed to improve frequency component decomposition and representation, and (2) a NIC module that enhances spatial consistency and structural fidelity during upsampling. The detailed architectural design and mathematical formulation of both modules are presented below.

As shown in Figure 3, the input image is first processed by a Deformable Convolution to accommodate geometric distortions and local deformations introduced by specular reflection. Subsequently, the encoder is constructed using a sequence of Conv + ReLU + MaxPool operations, generating hierarchical feature maps at progressively reduced resolutions.

At the bottleneck stage, a FaMC-Block is introduced to reconstruct frequency responses via parallel spatial convolution branches and a Fourier-domain transformation pathway. This enables more effective preservation of periodic fringe characteristics and suppression of frequency-domain noise, resulting in intermediate feature representation feature6.

The decoder follows a symmetric architecture with multi-level upsampling and skip connections to progressively recover spatial resolution. To mitigate checkerboard artifacts commonly observed in transposed convolutions, a NIC-Block is utilized at each upsampling stage, decoupling resolution enlargement from convolutional feature extraction, thereby enhancing spatial coherence and texture continuity.

Furthermore, shallow encoder features (feature1∼feature4) are fused with decoder-stage features (feature7∼feature10) to better preserve fine-grained texture details and high-frequency structural information. A final convolution layer maps the decoder output to a single-channel reconstructed fringe image.

Overall, the proposed network provides efficient information flow and dual-domain (frequency and spatial) enhancement capability, enabling robust and fine-grained fringe restoration under challenging reflective imaging conditions. Below, we present the implementation details of the core modules.

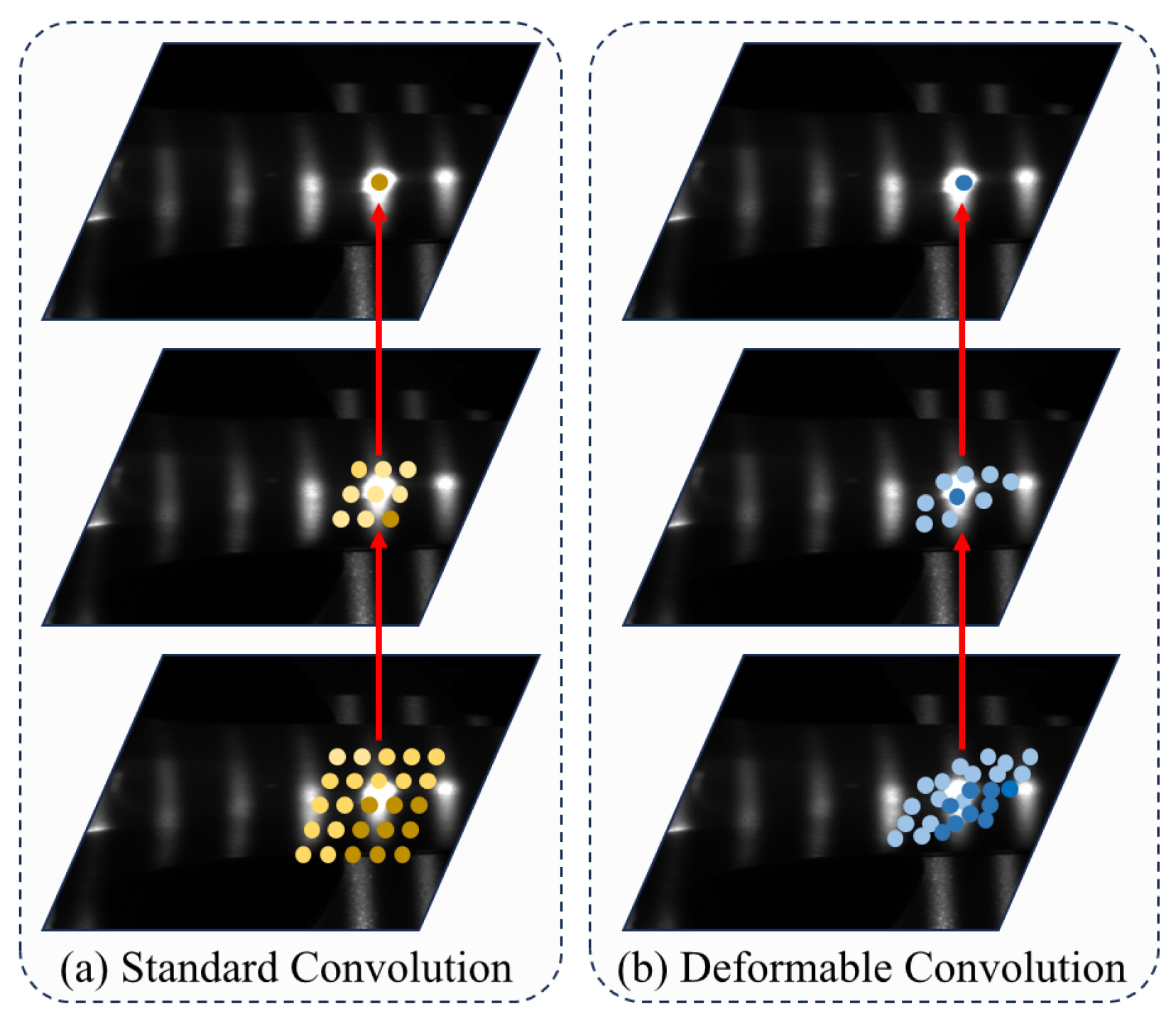

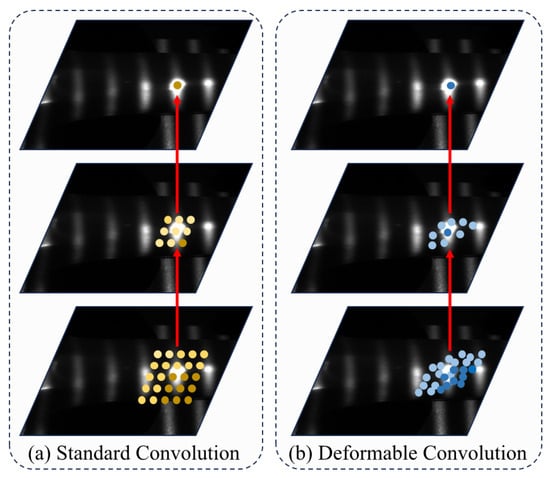

3.1. Deformable Convolution

In structured-light fringe images affected by strong reflections, local overexposure, stripe bending, and displacement may degrade the effectiveness of standard convolution, which relies on fixed sampling positions. To address this limitation, a deformable convolution layer is employed at the encoder input to adaptively adjust sampling locations according to local fringe distortions, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the deformable convolution mechanism used at the encoder input to adaptively adjust sampling positions in response to fringe distortions caused by strong reflections. The red arrow indicates the sampling process.

For a standard convolution, the sampling grid is defined as follows:

Deformable convolution introduces a learnable offset for each sampling location, and the output is computed as follows:

where denotes convolution kernel weights, and and are the input and output feature maps. Since may be non-integer, bilinear interpolation is adopted.

To suppress invalid responses in saturated reflectance regions, a modulated version is adopted by introducing modulation scalars :

This adaptive sampling mechanism enables robust fringe representation despite stripe stretching, discontinuities, or partial saturation, providing a stable foundation for subsequent frequency-domain enhancement and decoding restoration.

3.2. Frequency-Aware Multi-Scale Convolution (FaMC)

Specular reflections often cause local blur and periodic pattern attenuation in fringe images, while different frequency components play distinct roles in fringe representation. To explicitly model frequency responses, we introduce the FaMC module, which integrates a Fourier-domain processing pathway into a multi-branch convolutional structure.

Given input feature , FaMC contains four parallel branches:

- Branch 1: Standard Spatial Convolution

- Branch 2: Large Receptive Field Convolution

- Branch 3: Fourier-domain Transformation

- Branch 4: Channel Compression and Local Convolution

The fused output is obtained as follows:

FaMC enhances periodic structure preservation and improves robustness against high-frequency distortion and noise caused by reflective interference.

3.3. Nearest Interpolation with Convolution (NIC)

Upsampling using transposed convolution may introduce checkerboard artifacts, whereas interpolation-only approaches lack learnability and struggle to restore fine details. To address this, we propose the NIC module, which decouples resolution upsampling from convolutional feature extraction.

Given the low-resolution feature map , NIC performs

- Nearest-neighbor Upsampling:

- Feature Refinement using Convolution:

NIC achieves artifact-free upsampling and effective high-frequency restoration, making it well-suited for fringe reconstruction under reflective degradation.

Within the overall network architecture, the FaMC module is positioned at the end of the encoder to enhance frequency–structure awareness in high-level semantic features, while the NIC module operates along the progressive upsampling path in the decoder to reinforce spatial consistency and detail restoration. Through the complementary effects of these two modules, the proposed network demonstrates strong robustness in reconstructing fringe patterns degraded by severe specular reflections, achieving superior texture preservation and structural continuity.

3.4. Loss Function Design

To further improve the fidelity and structural consistency of fringe restoration under strong reflective interference, we introduce a joint loss function that integrates pixel-wise reconstruction constraints with structural similarity preservation. Specifically, the total loss is formulated as follows:

where and denote the balancing coefficients for each loss term.

- Mean Absolute Error Loss (MAE)

To measure the global reconstruction discrepancy between the predicted fringe image and ground truth I, the MAE is adopted:

where N is the total number of pixels, and and denote the predicted and ground-truth pixel values, respectively. Compared with squared-error losses, MAE is less sensitive to local intensity outliers, thus contributing to more stable optimization under highlight saturation and reflection-induced artifacts.

- Structural Similarity Loss (SSIM)

To enforce structural coherence and texture continuity, the SSIM is incorporated into the loss formulation. SSIM quantifies perceptual similarity between two image patches x and y in terms of luminance, contrast, and structure:

where and are mean intensities, and are variances, is covariance, and are stabilizing constants.

The SSIM-based loss term is defined as follows:

encouraging the restored fringe patterns to maintain perceptually consistent structural attributes, particularly beneficial for reestablishing periodic textures and phase-dependent transitions.

In our experiments, we set and , which provides a favorable trade-off between pixel-wise accuracy and structural preservation. The joint loss effectively constrains the reconstruction from both appearance and perceptual dimensions, and in combination with the frequency-domain enhancement of FaMC and the artifact-free refinement enabled by NIC, results in a more robust and high-fidelity restoration of structured-light fringe images under strong specular reflection interference.

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setup and System Parameters

All experiments were conducted using a camera–projector-based structured-light measurement system. The effective measurement field of view (FOV) is approximately 13 cm × 16 cm, which is suitable for high-dynamic-range 3D reconstruction of medium-scale objects. The input fringe images have a resolution of 1632 × 1248, consistent with the effective imaging resolution of the camera, ensuring adequate spatial sampling and fringe detail preservation. For fringe projection and encoding, the average intensity and a modulation amplitude . A minimum modulation threshold is imposed to cover a wide range of surface reflectance conditions. In addition, a 4-bit Gray code is used for phase unwrapping. The projector gamma parameter is set to to mitigate nonlinear illumination response effects. The geometric relationship between the camera and the projector is established through system calibration. The intrinsic parameters of the camera (including focal length, principal point, and distortion coefficients) and those of the projector are estimated during calibration, while the extrinsic parameters describing their relative pose are jointly obtained to form a unified imaging–projection model. A circular calibration target consisting of 17 × 14 dots with an inter-dot spacing of 6 mm is used. This calibration strategy is widely adopted in structured-light metrology and ensures reliable estimation of both intrinsic and extrinsic parameters, thereby guaranteeing geometric consistency in 3D reconstruction. During point cloud generation and post-processing, voxel-based downsampling and statistical outlier removal are applied to suppress noise and spurious points. The voxel size is set to 0.2 mm, and the reconstruction depth range is limited to [−50 mm, 100 mm]. All system parameters remain fixed across experiments unless otherwise stated.

4.2. Dataset Construction and Training Protocol

4.2.1. Virtual Dataset Generation

To enable effective training of the proposed FaNIC-Net, a large-scale and high-fidelity virtual dataset was constructed by simulating a structured-light scanning environment. As illustrated in Figure 5a, a digital twin of a real fringe projection profilometry (FPP) system was built in Blender, where the geometric configuration of the projector, camera, and target objects can be physically reproduced. This setup allows for the generation of diverse and photorealistic fringe patterns under controlled reflectance conditions.

Figure 5.

Representative examples from the constructed virtual structured-light dataset and the corresponding real-scene dataset.

The dataset generation process consists of two main stages:

- (1)

- Model Import and Preprocessing.

A total of 300 mesh objects in STL format were imported from public 3D model libraries. Each model was scaled and positioned to fit the predefined field of view and depth range. By assigning different material attributes, such as specular intensity and surface roughness—objects with various reflective behaviors were simulated, covering smooth metallic, semi-gloss, and diffuse surfaces.

- (2)

- Fringe Projection and Data Acquisition.

Using Blender’s structured-light scanning plugin, fringe sequences were generated following Gray coding and sinusoidal phase-shifting principles. The fringe frequency, orientation (horizontal/vertical), and image resolution (1920 × 1080) were adjustable. During scanning, the system automatically executed fringe projection and image capture, producing raw fringe images, wrapped/unwrapped phase maps, and ground-truth depth representations.

For each object, two sets of images were rendered: (i) a highly reflective (specular) version, serving as the network input. To improve the model’s adaptability to different surface reflectance conditions, the virtual dataset was constructed with varied material reflectance levels, including specular metal, electroplated surfaces, and diffuse ceramic/plastic targets. Illumination intensity and exposure settings were also adjusted to simulate typical fringe degradations such as saturation, dimming, glare, and contrast loss; (ii) a diffuse surface version, used as the supervision target. The resulting virtual dataset therefore consists of paired high-reflectance fringe patterns and their ideal reference images, providing training data for robust fringe restoration. Representative examples are shown in Figure 5c,e.

4.2.2. Real Measurement Dataset

To verify the network performance in real-world scenarios, we further conducted experiments using an actual fringe projection system, as shown in Figure 5b. The hardware setup includes a DLP projector (TI DLP3010, Tengju Technology, Hangzhou, China 1280 × 720) and an industrial camera (Hikrobot MV-CA020-10UM, Hikvision, Hangzhou, China, 1624 × 1240, 8-bit grayscale) equipped with a 12 mm fixed-focus lens.

Three types of representative objects were selected to cover typical HDR measurement scenarios: turbine blades, bicycle freewheels, and plaster sculptures. For each object, two data acquisition modes were used: (a) original high-reflective surface (network input) and (b) diffuse-coated surface after applying matte spray (supervision target). Such diffuse coating is widely adopted in HDR structured-light metrology as it suppresses specular saturation while preserving the underlying geometry, thus providing a physically reliable reference for supervision.

Additionally, multi-exposure fusion was used to generate HDR-enhanced fringe patterns to improve reconstruction reliability.

4.2.3. Training Configuration

FaNIC-Net was implemented using the PyTorch 1.10 framework and trained on a server equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU. The training consisted of 200 epochs with a batch size of 64 and an initial learning rate of . The full training process required roughly 3 h.

At the initial training stage, a virtual dataset was constructed under diverse reflectance and illumination conditions, covering a wide range of representative surface types such as highly specular metals, electroplated components, semi-gloss coatings, brushed metallic finishes, and diffuse ceramic/plastic materials. By varying surface reflectance levels and projection exposure parameters, the network was enabled to learn fringe deformation patterns associated with different reflectance-induced degradation behaviors.

Following virtual pre-training, real-scene fringe measurements were further employed for fine-tuning, enabling the model to adapt to practical acquisition noise, local saturation, non-uniform exposure, and strong specular interference. This two-stage “virtual pre-training + real fine-tuning” strategy significantly improves the model’s generalization capability when handling heterogeneous and high-reflectance surface materials in actual measurement scenarios.

4.3. Quantitative Experiment

4.3.1. Phase Error Evaluation

Table 1 reports the quantitative results of five representative methods, including 3-step, 12-step, DcMcNet, TC-Net, and our approach. A lower MAE [24] indicates that the reconstructed depth map is closer to the ground-truth distribution, thus reflecting the deviation in global reconstruction accuracy. Conversely, a SSIM [25] value closer to 1 signifies higher structural similarity between the predicted and reference depth maps.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison (MAE and SSIM) of five methods on different datasets. Lower MAE and higher SSIM indicate better performance.

From the MAE perspective, the 3-step method exhibits the largest reconstruction error (e.g., up to 0.0134 on the test set), revealing its clear limitations in depth recovery. The 12-step method achieves the best overall performance, maintaining MAE values within 0.0006–0.0007 across multiple evaluations. Our method achieves MAE values around 0.0007–0.0009, which are slightly higher than those of the 12-step approach but still substantially lower than those of DcMcNet (approximately 0.00072–0.00082) and TC-Net (approximately 0.00074–0.00084). Although DcMcNet and TC-Net show similar error levels, both remain marginally inferior to our method.

Regarding the SSIM metric, the 12-step method consistently produces the highest scores (up to 0.9412), indicating its superior structural fidelity. Our method maintains SSIM values in the range of 0.9370–0.9390, ranking second among all methods and outperforming both DcMcNet (0.9335–0.9376) and TC-Net (0.9327–0.9368). In contrast, the 3-step method yields the lowest SSIM scores (e.g., 0.8324–0.8452), demonstrating limited structural consistency.

In summary, both MAE and SSIM metrics reveal that although DcMcNet and TC-Net improve depth-map quality to some extent, their reconstruction accuracy and structural consistency remain inferior to those of the 12-step method and our approach. Notably, our method performs particularly well in highly reflective and distorted regions, effectively reducing reconstruction errors while preserving structural coherence. This ensures that the recovered depth maps provide high-quality and reliable inputs for structured-light-based 3D reconstruction systems.

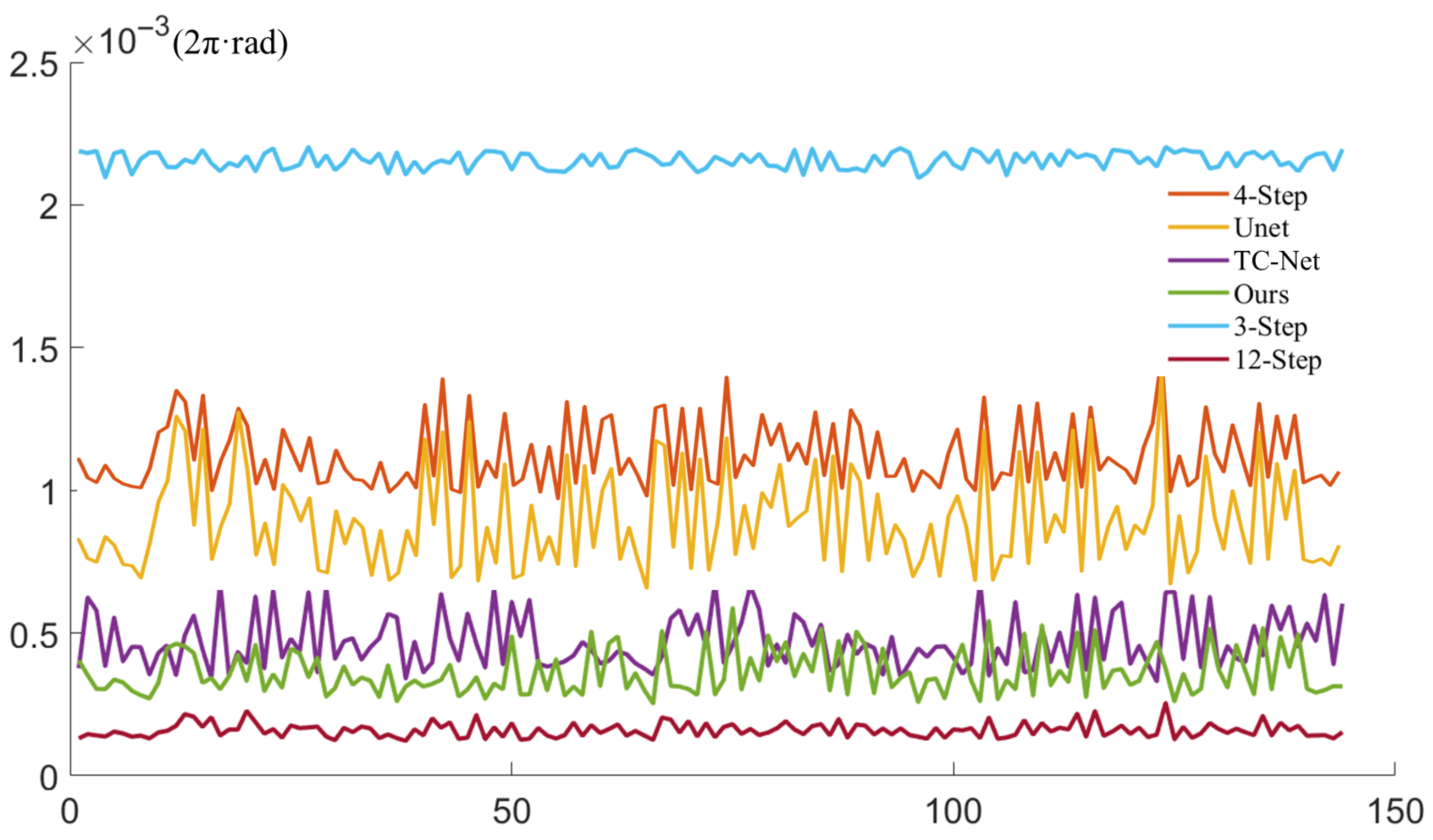

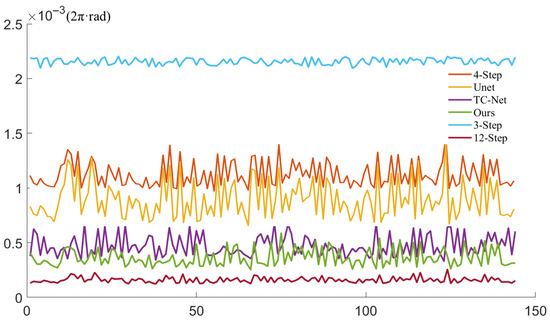

We also conducted a systematic quantitative evaluation of the performance of different methods in absolute phase computation. Specifically, the average absolute error (AAE) was calculated over 144 test scenarios, where a modulation threshold of was applied to automatically discard low-quality regions, ensuring that the error statistics were computed only over reliable phase pixels. The error distribution across all scenarios is shown in Figure 6, where the horizontal axis represents the scene index and the vertical axis denotes the average absolute error. The AAE is defined as follows:

where i indexes the valid pixels, and P denotes the total number of valid pixels.

Figure 6.

Distribution of the AAE over 144 test scenarios after modulation-based masking.

As illustrated in the figure, the proposed method consistently maintains a low error level across all test scenarios, without exhibiting noticeable outliers, which demonstrates its strong generalization ability and robustness. In terms of reconstruction accuracy, our method significantly outperforms both the classical three-step phase-shifting approach and U-Net-based learning methods, achieving higher phase-recovery precision while requiring substantially fewer input images. This advantage makes the proposed framework particularly suitable for real-time or resource-constrained phase measurement applications, where both computational efficiency and reconstruction quality are critical.

4.3.2. Metal Step Block Evaluation

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the proposed method on high-reflective industrial components, an optical-grade specular metal gauge block with a step interval of 5 mm was selected as the standard reference target. Due to its strong mirror-like reflectance characteristics, the step transition regions of this specimen easily exhibit severe saturation highlights, fringe discontinuities, and phase jumping, and therefore are widely adopted as benchmark objects for structured-light measurement validation under HDR conditions.

In this experiment, the same gauge block was reconstructed using seven representative approaches, including the 3-step phase shifting, 12-step phase shifting, fringe projection adjustment (FPA), multi-exposure compensation, U-Net, TC-Net, and the proposed FaNIC-Net. The reconstructed step heights were quantitatively compared against the nominal dimensions of the standard block. The corresponding measurement statistics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quantitative accuracy comparison on the specular metal gauge block with 5 mm step intervals. Bold font for best results.

Experimental results indicate that although both the 12-step phase shifting and the multi-exposure strategy partially mitigate saturation-induced errors, noticeable phase jump peaks remain at the step boundaries. The fringe restoration method also presents texture loss in strongly reflective regions, particularly around the sharp step transitions of the mirror surface. In contrast, the proposed FaNIC-Net achieves the highest surface continuity in mirror-reflective step areas, without exhibiting fringe collapse or phase discontinuities. The mean absolute error is reduced to 0.021 mm, and the maximum deviation is limited to 0.038 mm, which demonstrates a clear improvement over both conventional phase-shifting approaches and existing learning-based reconstruction methods.

Although the proposed method achieves stable restoration under most reflectance conditions, slight over-smoothing still occurs in extremely high-reflective regions, particularly at steep mirror transitions. To quantify this effect, we report the peak attenuation ratio (PAR) defined as the ratio between the recovered fringe amplitude and the reference amplitude in the same local region. As shown in Table 3, the PAR maintains a level of 0.92 in regular mirror zones, while it drops to approximately 0.85 in highly saturated curvature edges, indicating an 8–15% amplitude compression. Notably, this over-smoothing is localized at reflective discontinuities and does not propagate to adjacent diffuse or semi-reflective surfaces, which preserves global geometry consistency.

Table 3.

PAR in high-reflectance failure regions.

4.3.3. Efficiency Evaluation

To further assess the deployability of the proposed method in real-time structured light measurement scenarios, we evaluated the inference efficiency and reconstruction frame rate, and compared them with classical phase-shifting approaches and representative deep neural network frameworks. All experiments were conducted on an RTX 4060 GPU under identical input resolutions, using a single-frame fringe reconstruction configuration for timing measurement.

The results indicate that the proposed method achieves a real-time processing speed of 21.27 FPS, which is comparable to that of the 6-step phase-shifting approach while requiring only a single-shot fringe input instead of multiple exposures. In contrast, the representative learning-based TC-Net model reaches 16.56 FPS; although computationally efficient, its phase accuracy degrades notably under mirror-like high-reflective conditions. By comparison, the proposed method maintains high reconstruction fidelity and effective saturation compensation, while still achieving near real-time performance, demonstrating strong practicality for industrial structured light deployment.

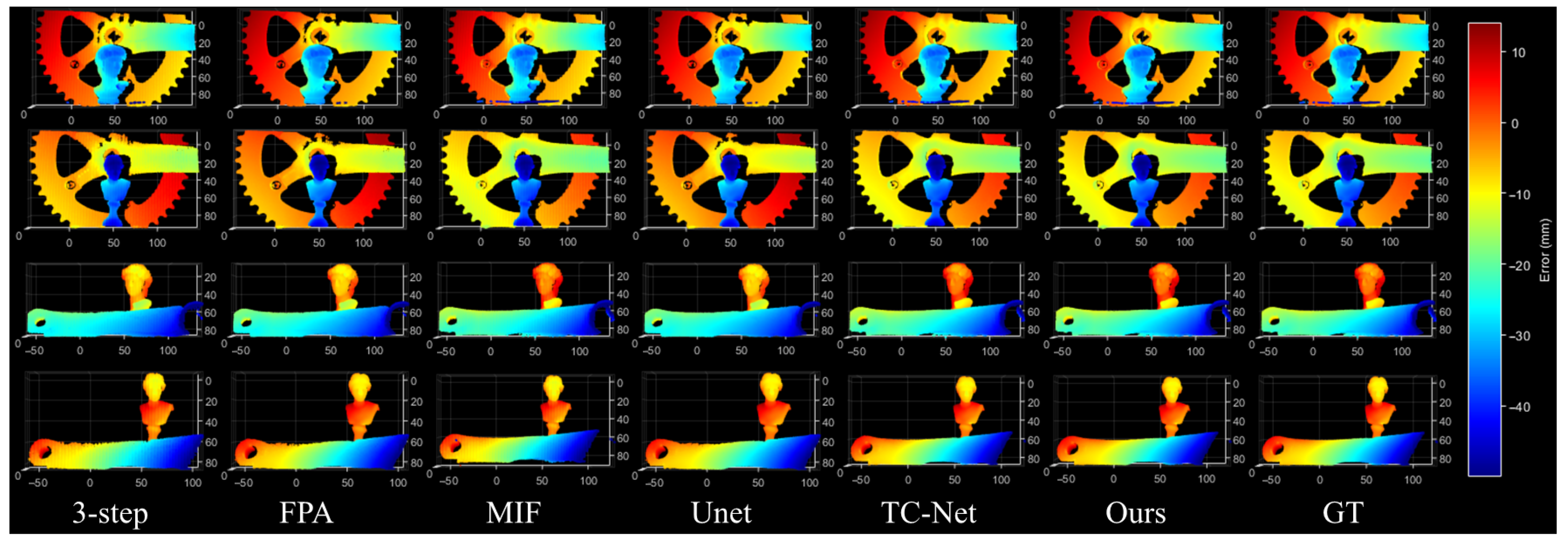

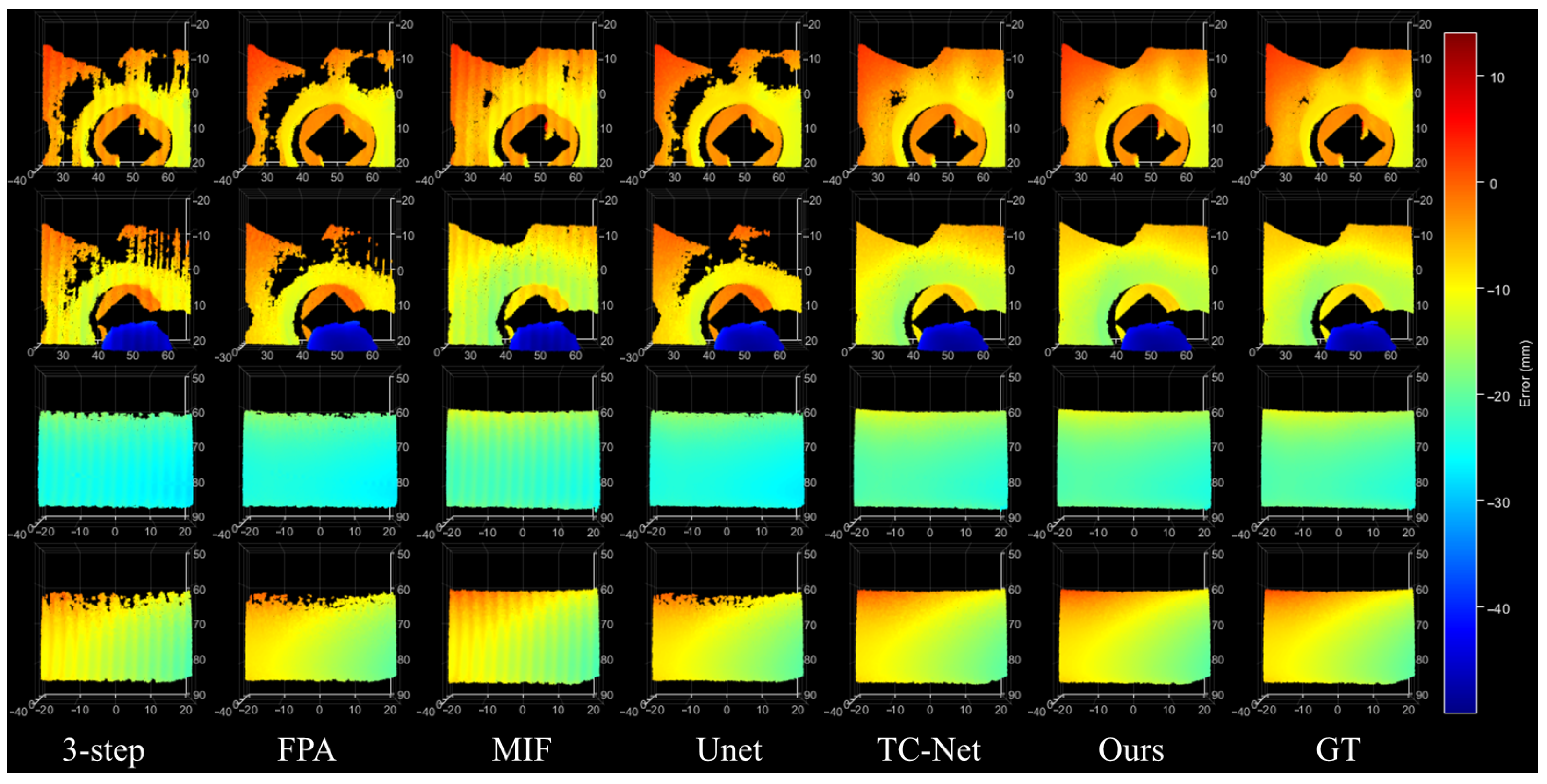

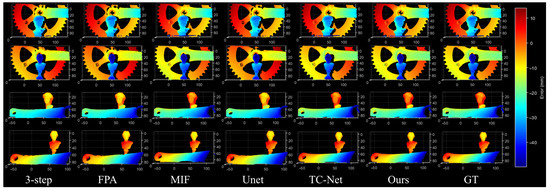

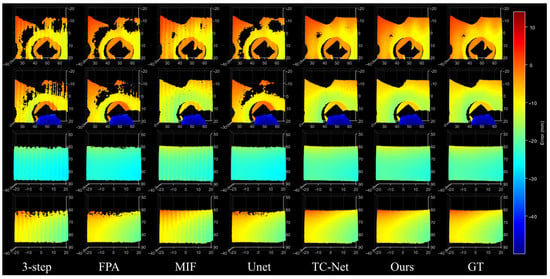

4.4. Qualitative Experiment

To further validate the applicability and generalization capability of the proposed method in complex high-dynamic-range (HDR) scenarios, we conducted qualitative comparison experiments on three representative HDR objects: a turbine blade, a bicycle flywheel, and a plaster bust. Figure 7 presents the overall reconstruction results obtained by different methods, while Figure 8 shows enlarged views of several critical regions. As can be observed, traditional three-step phase-shifting suffers from severe artifacts such as holes, discontinuities, and staircase distortions under highly challenging conditions, including strongly reflective metallic surfaces, densely distributed thin structures, and weak-texture smooth regions. Learning-based approaches such as U-Net and TC-Net demonstrate improved reconstruction performance yet still exhibit issues such as fringe breakage, local noise accumulation, and blurred geometric details.

Figure 7.

Overall 3D reconstruction results of different methods on three representative HDR objects, including a turbine blade, a bicycle flywheel, and a plaster bust.

Figure 8.

Zoomed-in comparison of key regions from the HDR reconstruction results. The proposed method achieves superior continuity, detail fidelity, and noise suppression relative to competing methods.

In contrast, the proposed method consistently achieves superior structural continuity and detail fidelity across all difficult scenarios. Highly reflective regions are accurately restored with smooth transitions, thin structures are reconstructed with clear contours and without misclassification, and weakly textured surfaces maintain natural and coherent depth variations. The zoomed-in results further confirm that our method provides significantly better saturation compensation, detail recovery, and noise suppression than the competing methods, thereby enhancing reconstruction quality under complex HDR conditions.

In summary, across the three representative HDR measurement objects—whether in saturated reflective areas, densely distributed thin structures, or weak-texture smooth surfaces—the proposed method exhibits qualitatively superior performance compared with existing approaches. The advantages are especially pronounced in the local enlarged views, underscoring the high robustness and practical reliability of our framework in challenging real-world scenarios.

4.5. Ablation Study

4.5.1. Frequency-Dependent Robustness Evaluation

We further examined the robustness of fringe restoration under different spatial periods T. Sinusoidal patterns with –104 were tested to cover both high-frequency (near-Nyquist) and low-frequency fringe conditions. For each period, distorted high-reflectance fringe inputs were restored by different methods and evaluated using MAE.

As summarized in Table 4, the proposed FaNIC-Net maintains low error across the majority of periods (–80), whereas performance degradation only appears at the extreme ends ( and ), where all approaches are affected by aliasing and phase instability. Importantly, FaNIC-Net consistently yields the lowest MAE across all T, demonstrating a clear robustness margin in frequency-constrained scenarios.

Table 4.

MAE comparison under varying fringe periods T. Bold font for best results.

4.5.2. Main Module Ablation Contribution

To comprehensively evaluate the contributions of each component within the proposed network, we constructed a series of ablation sub-networks (SubNet-1 to SubNet-3) centered around the deformable convolution (DC), the FaMC, and the NIC. Specifically, SubNet-1 removes all three modules and retains only the baseline architecture; SubNet-2 preserves DC alone to examine the effect of dynamic sampling on distortion compensation; SubNet-3 introduces only FaMC to analyze the role of multi-scale frequency-domain information in fringe restoration; additionally, a NIC-only sub-network was constructed to investigate its impact on structural detail preservation. Table 5 summarizes the mean absolute error (MAE) and structural similarity (SSIM) obtained by the full model and all ablation variants on the training set, validation set, test set, and real-world datasets.

Table 5.

Ablation study of the proposed network components. Full Model denotes the complete architecture, while DC, FaMC, and NIC represent removing the deformable convolution, frequency-aware multi-scale convolution, and nearest-interpolation convolution modules, respectively. Bold font for best results.

From the MAE results, it can be observed that the complete model achieves the lowest error across all datasets, significantly outperforming any sub-network with one of the modules removed. Using DC or FaMC alone yields noticeable performance improvements, while incorporating NIC further enhances structural continuity in the recovered depth maps, leading to an additional reduction in reconstruction error. The SSIM results likewise confirm that all three modules contribute positively to structural consistency: FaMC substantially strengthens the representation of frequency-domain fringe structures, DC effectively suppresses edge misalignment caused by local distortions, and NIC improves geometric smoothness and boundary fidelity in weak-texture regions.

4.5.3. Fine-Grained Ablation of FaMC and NIC

To further investigate the independent contributions of each sub-branch within the FaMC module, a fine-grained ablation study was conducted. Specifically, the frequency branch (DFT/IDFT), the large-receptive-field branch, and the local-detail branch were individually removed while keeping the overall network structure unchanged. As summarized in Table 6, removing any of these branches leads to a noticeable degradation in reconstruction accuracy. In particular, eliminating the frequency branch results in an increase of approximately 15–20% in MAE, indicating that explicit frequency-domain modeling plays a key role in suppressing specular-induced fringe distortions. Meanwhile, the large-receptive-field branch and the local-detail branch contribute roughly 6–10% performance gains from the perspectives of global structural consistency and high-frequency preservation, respectively.

Table 6.

Fine-grained ablation analysis of FaMC and NIC sub-components. Bold font for best results.

In addition, a fine-grained comparison of the NIC upsampling strategy was performed. Using transposed convolution as the baseline, the upsampling process was replaced with nearest-neighbor interpolation, bilinear interpolation, and nearest-neighbor interpolation with a following 3 × 3 convolution refinement. The results demonstrate that interpolation-only variants cause a 3–5% SSIM drop due to insufficient detail recovery, whereas transposed convolution tends to introduce checkerboard artifacts in highly reflective transition regions. In contrast, the nearest-neighbor plus convolution refinement design achieves approximately 8–12% accuracy improvement over the baseline by balancing high-frequency fidelity and artifact suppression, which is the main reason this upsampling strategy was ultimately adopted in our final architecture.

In summary, the DC, FaMC, and NIC modules collectively enhance the network’s ability to restore distorted fringes under high-reflectance conditions. FaMC improves multi-scale frequency-domain structural modeling, DC provides adaptive sampling to correct localized distortions, and NIC reinforces geometric and structural consistency. Their synergistic integration enables the final model to achieve superior reconstruction accuracy and detail fidelity in challenging reflective scenarios.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we address the severe fringe distortions and phase information loss caused by specular reflections on highly reflective object surfaces, and propose an enhanced structured-light 3D reconstruction framework, termed FaNIC-Net. The framework integrates a FaMC and a NIC, which jointly strengthen the network’s representational capacity from the perspectives of frequency–structure modeling and spatial-structure restoration. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms existing approaches on both synthetic and real-world datasets, exhibiting superior robustness in fringe restoration within reflective regions, depth-map consistency, and geometric detail preservation. Furthermore, FaNIC-Net effectively compensates for phase information loss in high-reflectance areas without requiring additional hardware assistance or multi-exposure acquisition, providing an efficient and scalable solution for high-precision 3D measurement under complex reflective conditions.

In addition to outperforming existing solutions in fringe restoration accuracy, the proposed FaNIC-Net reveals a more fundamental implication for HDR structured-light measurement. Rather than relying on multi-exposure strategies or optical hardware suppression, our method demonstrates that single-frame fringe recovery can be achieved through joint frequency-domain modeling and spatial continuity reinforcement. This indicates a shift from traditional exposure-dependent HDR compensation toward learning-based fringe reconstruction, where periodicity restoration, saturation decoupling, and phase stability are handled in a unified computational framework. As evidenced by both real-scene and high-reflectance failure cases, FaNIC-Net provides not only quantitative improvements but also a practical pathway toward non-invasive, calibration-free, and real-time structured-light imaging, which is of direct value to demanding industrial inspection scenarios involving specular metals, polished components, and optical-grade surfaces.

Despite the favorable performance achieved, several aspects warrant further investigation. First, the current framework primarily learns from static fringe images, and its adaptability to varying projection frequencies, exposure strategies, or non-periodic illumination patterns remains to be systematically evaluated. Second, although the NIC module alleviates checkerboard artifacts, local over-smoothing may still occur in extremely reflective or strong-spot regions, indicating that the model’s generalization ability under extreme dynamic-range conditions can be further improved. Finally, while the inference speed of FaNIC-Net meets basic measurement requirements, real-time industrial inspection scenarios demand additional network optimization or model compression strategies to enhance overall computational efficiency and advance its real-time performance for broader industrial deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and J.M.; methodology, X.Z.; software, C.L.; validation, X.Z. and C.L.; formal analysis, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.L. and J.C.; visualization, C.L.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, J.M.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by General research projects of Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education, Y202557906, and the APC was funded by C.L.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author due to their large volume and storage limitations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cui, B.; Tao, W.; Zhao, H. High-precision 3D reconstruction for small-to-medium-sized objects utilizing line-structured light scanning: A review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, X.; Song, Z.; Song, L.; Zeng, H. Robust pattern decoding in shape-coded structured light. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2017, 96, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, J.; Vargas, R.; Romero, L.A.; Zhang, S.; Marrugo, A.G. What is the best triangulation approach for a structured light system? In Proceedings of the Dimensional Optical Metrology and Inspection for Practical Applications IX, Online, 27 April–8 May 2020; Volume 11397, pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, T.; Liang, D.; He, Z. A review on 3D measurement of highly reflective objects using structured light projection. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 4205–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Qi, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Gao, J. A high precision measurement method of large-size turbine blade based on structured light 3D measurement. In Proceedings of the Eighth Symposium on Novel Photoelectronic Detection Technology and Applications, Kunming, China, 9–11 November 2021; Volume 12169, pp. 3191–3196. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Bai, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, Q.; Luo, Y.; Yang, K.; Zhang, X. Target enhanced 3D reconstruction based on polarization-coded structured light. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Ye, Y.; Gu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Song, Z. A polarized structured light method for the 3d measurement of high-reflective surfaces. Photonics 2023, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, H. Automatic Setting of Optimal Multi-Exposures for High-Quality Structured Light Depth Imaging. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 152786–152797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Pan, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, P.; Liu, L. Real-time stripe width computation using back propagation neural network for adaptive control of line structured light sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, X. 3D reconstruction of a highly reflective surface based on multi-view fusion and point cloud fitting with a structured light field. Appl. Opt. 2025, 64, A73–A83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Zheng, D.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, C.; Han, J. Deep learning-based fringe modulation-enhancing method for accurate fringe projection profilometry. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 21692–21703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Zuo, C.; Feng, S. High-speed high dynamic range 3D shape measurement based on deep learning. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2020, 134, 106245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Jiang, X.; Fan, L.; Wei, C.; Yue, H.; Liu, Y. High-precision dynamic three-dimensional shape measurement of specular surfaces based on deep learning. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 17437–17449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, G.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, X.; Xie, D.; Zou, B. Deep-learning-assisted composite polarized fringe projection profilometry for three-dimensional measurement of high-dynamic-range objects. Appl. Opt. 2024, 64, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chen, W.; Madhusudanan, H.; Ge, J.; Ru, C.; Sun, Y. Optical measurement of highly reflective surfaces from a single exposure. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 1882–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y. An accurate measurement of high-reflective objects by using 3D structured light. Measurement 2024, 237, 115218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Tu, D. Fringe projection profilometry with lightweight transformer-CNN network for high-dynamic-range scenes. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 105202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’shea, K.; Nash, R. An introduction to convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.08458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, D. The Discrete Fourier Transform: Theory, Algorithms and Applications; World Scientific: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. High-speed 3D shape measurement with structured light methods: A review. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2018, 106, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, R.W. The Gray Code; Technical Report; Department of Computer Science, The University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, C.; Feng, S.; Huang, L.; Tao, T.; Yin, W.; Chen, Q. Phase shifting algorithms for fringe projection profilometry: A review. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2018, 109, 23–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Sun, X.; Wu, H. Unequal-period combination approach of gray code and phase-shifting for 3-D visual measurement. Opt. Commun. 2016, 374, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hore, A.; Ziou, D. Image quality metrics: PSNR vs. SSIM. In Proceedings of the 2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Istanbul, Turkey, 23–26 August 2010; pp. 2366–2369. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.