Abstract

Laser-driven ion acceleration is a rapidly developing branch of plasma physics and laser science whose primary practical goal is to provide a physical and technological basis for the construction and development of new types of ion accelerators. Laser-driven accelerators can be less complex and more compact than currently used RF-driven accelerators, while the intensities, fluences, and powers of laser-accelerated ion beams can potentially exceed those achieved in RF accelerators. This paper focuses on the generation of very intense ion beams driven by a multi-PW femtosecond laser. The acceleration mechanisms enabling the generation of such beams are characterized, and the properties of multi-PW laser-driven uranium ion beams are discussed in detail based on the results of advanced particle-in-cell numerical simulations. The feasibility of generating sub-picosecond, multi-GeV, mono-charge uranium beams with extreme intensities (~>1020 W/cm2) and fluences (~>GJ/cm2) is demonstrated, and methods for controlling the beam parameters are identified. It is shown that using such beams, extreme states of matter with parameters unattainable with ion beams from conventional accelerators can be created. The prospects for applications of ultra-intense laser-driven ion beams in high-energy density physics, inertial confinement nuclear fusion, and in certain areas of nuclear physics are outlined.

1. Introduction

Energetic ion beams find applications in a variety of scientific and technological fields, including nuclear and particle physics, high-energy density physics (HEDP), inertial confinement fusion (ICF), materials science, cancer therapy, and others. They are routinely produced in conventional accelerators (RF-driven and others), which enable the generation of narrow-spectrum beams with ion energies ranging from MeV to multi-TeV. High-energy ion beams can also be produced in plasma accelerators driven by short (pico- or femtosecond) high-power laser pulses. The electric fields accelerating ions in such accelerators can range from GeV/cm to TeV/cm, and thus ions can be accelerated to very high energies in ~1 ps or less over distances no greater than 1 mm. As a result, these accelerators can be significantly smaller and less complex than conventional accelerators, and the generated ion beams can have significantly shorter durations and higher intensities than those from conventional accelerators.

Research on laser ion acceleration driven by short laser pulses, spanning over two decades, has been focused primarily on maximizing ion energy and minimizing the energy spectrum width and angular divergence of the ion beam (see, for example, review papers [1,2,3]). However, for ion beam applications in fields such as HEDP and ICF, in addition to the energy spectrum and angular distribution of the beam, the energy fluence (Fi) and intensity (Ii) of the ion beam are crucial. At currently achievable laser intensities (~1022–1023 W/cm2 [4,5,6]), the maximum experimentally demonstrated ion energies are in the multi-GeV range [7] and are three orders of magnitude lower than the maximum energies achieved in large RF-driven accelerators. At ultra-high intensities of ~1023–1024 W/cm2 expected in 100-PW lasers [8,9,10,11], the energies of ions produced in laser-driven accelerators are likely to reach sub-TeV values. This will still be at least one order of magnitude lower than those achieved in RF-driven accelerators. The energy spectrum of laser-accelerated ions is relatively broad, much broader than that achieved in conventional accelerators, and methods to narrow this spectrum to the level achieved in these accelerators without dramatically reducing beam efficiency have not yet been developed. The competitiveness of laser-driven accelerators with conventional ones in terms of achievable ion energies and spectral quality seems questionable, not only currently but also in the foreseeable future. The situation is completely different when we compare the fluences, intensities, and powers of ion beams produced in laser accelerators and conventional accelerators. It has been demonstrated in experiments for quite a long time that even at relatively low intensities (~1019 W/cm2) and energies (~10–20 J) of a sub-picosecond laser driver, the intensity of a laser-accelerated ion (proton) beam near the ion source can reach 1018 W/cm2 and the beam power can exceed 1 TW [12,13]. These beam parameters are comparable to those achieved by ion beams produced in large conventional accelerators. An increase in the intensity and power of the laser driver naturally leads to an increase in the intensity and power of the generated ion beam, and at currently achievable laser intensities (~1022–1023 W/cm2) and powers (multi-PW) [4,5,6] of femtosecond lasers, the peak intensities and powers of the generated ion beams can potentially reach very high values, much higher than those achieved even in the largest RF-driven accelerators. Very high intensities and powers of laser-generated ion beams are primarily the result of very short ion pulse durations, which near the ion source can be ~1 ps or shorter [14,15]. Furthermore, the density of the laser-generated ion beam near the source is typically several orders of magnitude higher than that of conventional accelerator beams. As a result, the energy fluences of laser-generated beams could reach GJ/cm2.

Thus, when comparing the intensities, powers, fluences and durations of ion beams, laser-driven accelerators can not only effectively compete with conventional accelerators but, in principle, can also produce ion beams with parameters significantly exceeding those achieved in conventional accelerators. Constructing laser-driven accelerators focused on achieving maximum ion beam intensities, powers, and fluences would open the prospect of exploring new areas of research in HEDP and ICF, and perhaps also in nuclear physics and other fields. Unfortunately, most researchers studying laser-driven ion acceleration have focused their research on maximizing ion energy and improving the quality of the energy and angular spectrum of the ion beam (see review papers [1,2,3]). Only in relatively few works (e.g., [15,16,17,18,19,20]), and mainly in those related to fast ignition of inertial confinement fusion [16,17,18,19], have ion beam parameters such as intensity, fluence, power, and beam duration been analyzed and numerically optimized. However, to produce ion beams enabling thermonuclear ignition, picosecond laser drivers with very high energy (≥100 kJ) are necessary, the prospect of building which is still quite distant.

Very intense ion beams can, in principle, also be produced at currently achievable intensities (~1023 W/cm2) and powers (multi-PW) of femtosecond laser drivers [15,20]. Such beams can be very useful in HEDP research and also in certain areas of nuclear physics. In HEDP, beams of super-heavy ions such as uranium or lead ions [21,22] are particularly desirable, primarily due to their high stopping power in interactions with materials. Collisions of high-energy super-heavy ions also play a very important role in nuclear physics. Therefore, from the point of view of possible applications of laser-generated intense ion beams in these two fields of research, beams of super-heavy ions are of special interest.

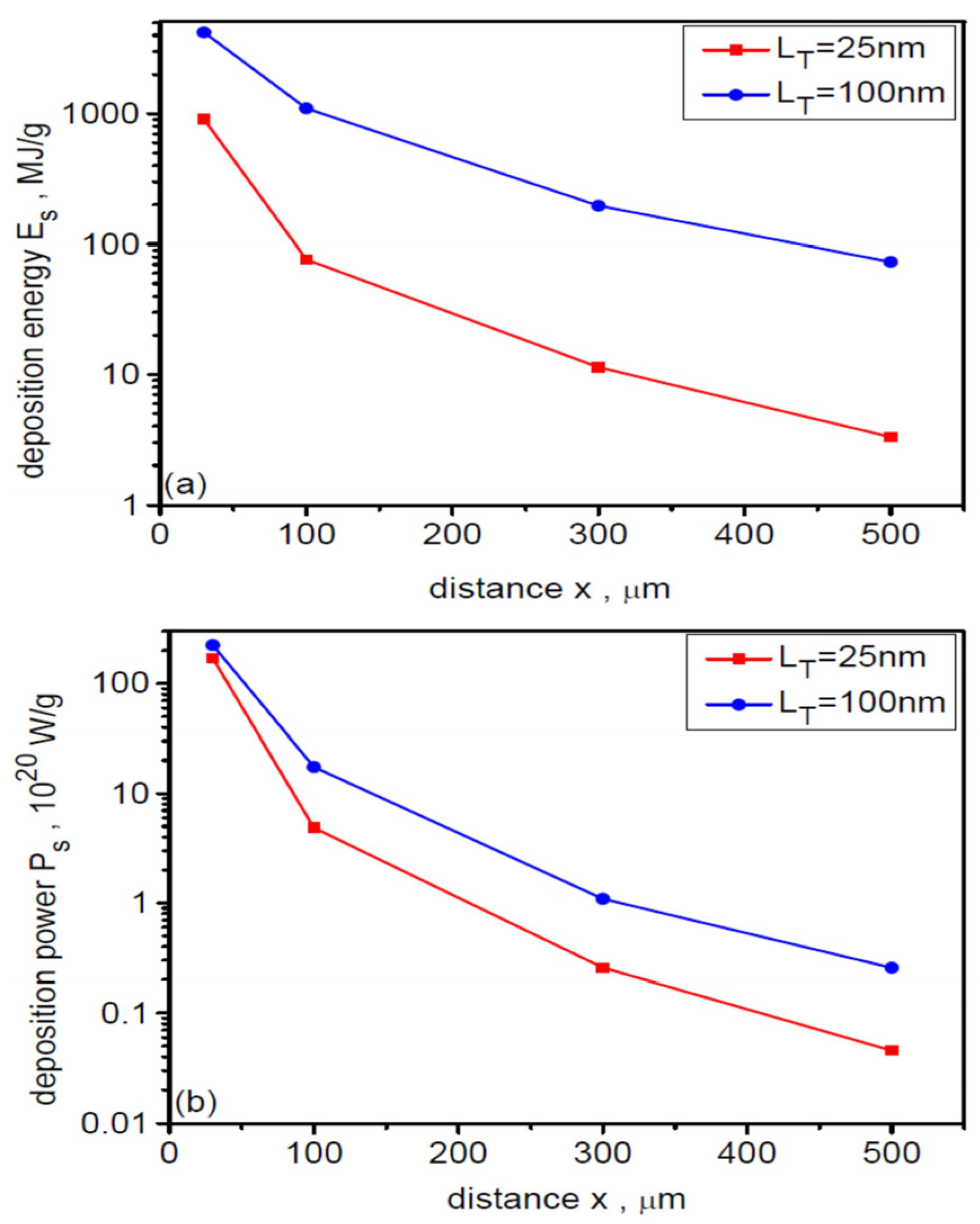

This paper demonstrates the feasibility of producing ultra-intense uranium ion beams in a laser accelerator driven by a multi-PW femtosecond laser and presents the results of comprehensive numerical studies of the properties of the generated beams. The studies were conducted using an advanced two-dimensional (2D) particle-in-cell (PIC) computer code, which specifically incorporates dynamic ionization of uranium atoms and ions and the generation of synchrotron radiation accompanying ion acceleration. At a fixed laser intensity of 1023 W/cm2, the effects of the laser focal spot size, dL, and the target thickness, LT, on various ion beam characteristics were investigated. In particular, the influence of dL and LT on the ionization and energy spectrum of the ion beam, on the intensity, fluence, and duration of the ion beam, as well as on the energetic efficiency of ion acceleration was determined. Furthermore, key parameters characterizing the ability of the generated uranium ion beam to create high-energy-density (HED) states of matter—namely, the energy and power deposited per gram of matter—were calculated for a carbon target irradiated by the beam.

The paper is structured as follows. After an introduction (Section 1), Section 2 briefly characterizes the mechanisms of laser-driven ion acceleration that favor the generation of ultra-intense ion beams. Section 3 describes the laser driver and target parameters selected for numerical simulations and the PIC code. The most important simulation results are presented in Section 4, where the influence of the laser focal spot size (Section 4.1) and the uranium target thickness (Section 4.2) on various parameters of the generated uranium ion beam is presented and discussed. Section 5 presents selected results concerning the generation of synchrotron radiation, which is the main source of losses in the ion acceleration process but can also be a source of powerful pulses of short-wavelength radiation Section 6 discusses some limitations and inaccuracies of the computer model used in the simulations, some issues related to plasma instabilities occurring during ion acceleration, the practical achievability of the assumed target and laser parameters, and the possibility of conducting experiments to verify the simulation results. Section 7 outlines some possible applications of ultra-intense laser-generated ion beams, primarily in HEDP. Section 8 summarizes the main results of our research.

2. Ion Acceleration Mechanisms Enabling the Generation of Ultra-Intense Ion Beams

To produce ultra-intense ion beams useful for a variety of applications, the mechanism of laser-driven ion acceleration must meet several requirements. Below, we will discuss the more important of these requirements and attempt to identify mechanisms that can best meet these requirements. The intensity (Ii) and energy fluence (Fi) of an ion beam can be defined as follows: Ii = niviEi = niEi3/2, Fi = σiEi where ni is the ion density, vi and Ei are the ion velocity and energy, respectively, σi = nil is the areal ion density (or ion fluence in units of cm−2), and l is the thickness of the ion layer. To achieve high intensity values, high ion energy and ion density are necessary, and to achieve high energy fluence, the ion layer must also be sufficiently thick. To achieve high values of Ii and Fi, the ion acceleration mechanism should not only be capable of accelerating ions to high energies but also effectively accelerate dense, possibly thick, ion layers.

Most possible ion beam applications require the ion accelerator to be compact, economical, and flexible enough to adapt beam parameters to the specific application. The largest, most complex, and most expensive component of a laser-driven accelerator is the laser driver. Its size, complexity, and cost usually depend largely on the laser energy. From this perspective, a crucial requirement for the usefulness of an ion acceleration mechanism is its ability to ensure high efficiency in converting laser energy into ion beam energy. The higher this efficiency, the lower the laser energy required to achieve the required beam parameters, which in turn allows for minimizing the size and cost of the driver. Lower driver energy also potentially allows for an increase in the driver repetition rate. Thus, the ion acceleration mechanism should ensure high efficiency of transformation of laser energy into ion beam energy.

An important parameter determining the usefulness of an ion beam is the beam angular divergence. A large beam divergence usually hinders or prevents effective studies of ion beam-target interactions, because moving the target away from the ion source by a distance much greater than the source’s size, typically required in research, can lead to a dramatic decrease in the beam intensity and fluence at the target. The ion acceleration mechanism used to produce an ultra-intense ion beam should therefore enable the generation of a beam with a relatively small angular divergence.

A desirable property of an ion beam in many applications is a narrow energy spectrum. Meeting this requirement is particularly important in the potential applications of ultra-intense ion beams in nuclear and particle physics, where relative spectral widths of no more than a few percent are often required. When using these beams in HEDP or ICF research, the requirements for energy spectral width are more lenient, and spectral widths of several dozen percent are typically acceptable. Furthermore, when using heavy ion beams in nuclear/particle physics, HEDP or ICF, a desirable beam property is a narrow ionization spectrum, meaning the beam should be largely mono-charged.

Currently, many ion acceleration mechanisms are known that enable the acceleration of ions of various masses (from protons to super-heavy ions) by laser pulses with intensities ranging from non-relativistic to ultra-relativistic, and under various laser-target interaction conditions (see, for example, review papers [1,2,3,14]). The most common include: target normal sheath acceleration (TNSA) [23,24,25,26,27,28], radiation pressure acceleration (RPA) [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], collisionless electrostatic shock acceleration (CESA) [39,40], skin layer ponderomotive acceleration (SLPA) [13,41,42], Coulomb explosion acceleration (CEA) [38,43,44,45], laser afterburner acceleration (BOA, sometimes called relativistic induced transparency acceleration—RITA) [46,47,48,49], and magnetic vortex acceleration (MVA) [50,51]. At high laser intensities, several mechanisms typically participate in the acceleration process (e.g., RPA + TNSA + CEA or RPA + TNSA + CEA + RITA), and the contribution of each is determined by the laser and target parameters. Unfortunately, at the current stage of research on these mechanisms, none of them is capable of simultaneously meeting all the above-mentioned requirements for generating an “ideal” ultra-intense ion beam. It seems that the RPA mechanism comes closest to meeting these requirements. We will discuss this mechanism in more detail below.

In the RPA mechanism, ions are accelerated by ponderomotive forces induced by the laser beam in the skin layer near the critical plasma density (pre-plasma) in front of the target illuminated by the beam. One of these forces is directed forward (in the direction of beam propagation), and the other in the opposite direction (backward). Each of these forces pushes electrons from the skin layer in the direction of the force and locally separates them from the plasma ions. Two so-called double layers are created, each composed of an electron layer and an ion layer, one propagating forward and the other backward. A very strong electric field is generated between the negative electron layer and the positive ion layer, accelerating the ions in the wake of the moving electron layer driven by the ponderomotive force. In this way, two bunches of ions are generated and accelerated in the forward and backward directions. However, when the laser beam intensity is sufficiently high (>1020 W/cm2) and the plasma density gradient near the critical density is high, the forward ponderomotive force (ponderomotive or radiation pressure) is much higher than the backward one, and practically only one high-density forward accelerated ion bunch is generated. This ion acceleration mechanism is commonly called radiation pressure acceleration (RPA) [1,2,3,14].

The RPA mechanism typically consists of two stages (regimes): the hole-boring stage (HB) and the light-sail stage (LS). Which of these regimes dominates depends on the target thickness (LT) and the laser fluence (FL). When the target is thick enough (or the fluence is insufficiently high), ions from the front of the target are accelerated toward the target interior by the charge separation field of the forward-moving double layer driven by the laser radiation pressure. The increase in ion energy is accompanied by an increase in the number and density of accelerated ions, since the positively charged ion layer in the moving double layer acts like a snowplough on the ions in the undisturbed portion of the target. As a result, a dense ion (plasma) block is formed, and almost all the laser energy is used to form and accelerate this block inside the target. In this case, the RPA-HB regime dominates the acceleration process. Optimal conditions for this regime occur when the target thickness LT ≈ LHB = τLVHB, where VHB is the average recession velocity of the ion surface driven by the laser piston and τL is the laser pulse duration. Approximate analytical formulas for estimating the energy of ions accelerated in the RPA-HB regime can be found in [2].

If the target is sufficiently thin (or the laser fluence is sufficiently high), the RPA-LS regime dominates the ion acceleration process. In this case, only a small portion of the laser energy is used to ionize the target and accelerate ions within the target, while the dominant portion is used to accelerate the ionized target in free space behind the initial target position. For the RPA-LS regime to be effectively implemented, the target thickness should meet the following conditions [34]: 1/4 Lskin < LT < 5 Lskin, where Lskin = γ1/2 c/ωp is the relativistic skin depth of the plasma (γ ~ IL1/2—relativistic parameter; ωp—electron plasma frequency; c—speed of light). When LT > 5 Lskin, the TNSA-like mechanism dominates, while when LT < 1/4 Lskin, the acceleration corresponds to the CEA mechanism. Acceleration is most efficient when LT ~ (1–2) Lskin, provided that the transverse expansion of the plasma during the laser pulse is small and the pulse is not very long. An analytical formula for estimating the energy of ions accelerated in the RPA-LS regime when the target areal density, σ, and the laser fluence are known can be found in [2].

From the point of view of generating ion beams with ultra-high fluences and intensities, the following features can be considered the most important advantages of the RPA mechanism (see, e.g., [14]): (a) the areal ion density, σi, of the beam can be very high (up to ~1019 cm−2 close to the source), (b) with ultra-high laser driver intensities already achieved, ion energies can reach multi-GeV energies and higher, (c) the energy efficiency of ion acceleration is high and can reach several dozen percent for both light, heavy, and super-heavy ions, (d) ion pulses generated by the RPA can be very short—from several tens of fs to several ps. The main disadvantages of the RPA mechanism are: (a) achieving high energy efficiency of conventional acceleration requires very high laser intensities (>>1021 W/cm2) and high laser pulse contrast, (b) obtaining high ion beam quality requires high laser beam homogeneity, (c) ion acceleration is usually accompanied by plasma instabilities (Rayleigh-Taylor-like and others), which lead to a deterioration of the ion beam quality. Despite these drawbacks, RPA remains the most effective currently known mechanism for generating ultra-intense ion beams.

RPA typically dominates ion acceleration when laser intensities are very high (>>1021 W/cm2). In the region of relativistic but moderate laser intensities (~1019–1021 W/cm2), acceleration is typically dominated by TNSA—the best-understood and widely used acceleration mechanism. Potentially, TNSA also enables the generation of ion beams of high intensity and fluence, although with parameters significantly lower than those achievable using RPA.

In TNSA, the laser beam interacting with the target generates fast electrons that penetrate the target and, upon exiting, form a negatively charged layer at its rear surface, acting as a moving virtual cathode. Between the cathode and the target surface, a very strong electric field (~tens of GV/cm or higher) is created which ionize atoms located in a thin (~5–10 nm) layer near the target surface. The ions thus produced are then accelerated by this field and move in a direction close to the normal to the target surface. Because only ions from a very thin target layer are accelerated, the areal density σi of the ion source is relatively small, σi < 1017 cm−2, and the ion density in the source ni is moderate, ni < 1019 cm−3. Thus, achieving high ion beam fluences (Fi = σiEi) and intensities (Ii = niviEi) is possible only at very high ion energies, significantly higher than in the RPA mechanism, where the values of σi and ni can be 2–3 orders of magnitude higher. Achieving Ei values much higher with TNSA than with RPA does not seem possible primarily due to the less favorable scaling of Ei with laser intensity IL [14]: Ei ~ IL1/2 for TNSA, while for RPA-LS Ei ~ (ILτL)a, where a = 2 for vi << c, and a = 1 for vi ≈ c. Furthermore, the energy spectrum of TNSA-driven ions is typically much broader than that achievable with RPA, and therefore the ion pulse generated by TNSA is longer than for RPA.

On the other hand, because ions are accelerated primarily in the direction normal to the rear surface of the target, TNSA enables focusing of the ion beam by curving this surface [52,53,54,55]. This enables achieving ion fluences and densities higher than those in the ion source (at the target surface) at distances comparable to the radius of curvature of this surface (e.g., a hemisphere). The increase in Fi and σi values is also facilitated by the fact that the surface from which ions are extracted and accelerated is much larger than the size of the laser beam on the target, and therefore the total number of accelerated and focused ions can be high. Unfortunately, due to the non-uniform distribution of propagation directions and energies of ions in the source, a significant portion of the ions propagate outside the ion focus region, and the efficiency of laser energy transfer into the energy of the dense focused ion beam usually does not exceed a few percent [55]. Moreover, due to the strong dependence of the TNSA mechanism efficiency on the Z/A ratio of the accelerated ions (Z—charge state of the ion, A—atomic mass number of the ion), this mechanism is effective mainly for protons (Z/A = 1) and fully ionized light ions (Z/A = 1/2).

Despite the shortcomings noted above, TNSA can be a useful mechanism for generating ion beams of high fluence and intensity, both when TNSA is the dominant mechanism in the acceleration process and when it merely supports the RPA mechanism in this process.

The remaining acceleration mechanisms mentioned above are usually unable to generate ultra-intense ion beams with useful properties because they do not meet most of the requirements outlined at the beginning of this section. However, some of them can support the RPA and/or TNSA mechanisms in generating such beams if the laser and target parameters are properly selected. These include the RITA mechanism. If the laser pulse is sufficiently long and intense, RITA can accompany RPA in the final stage of acceleration and, by increasing the ion energy at this stage, increases the intensity and fluence of the ion beam. An acceleration scheme combining RPA and RITA, called sheet crossing, has recently been studied and applied to proton acceleration [36,37]. In this scheme, ions from the front part of a relativistically transparent thin target are accelerated by the RPA to high energies, enabling them to cross through the TNSA sheet generated on the rear side of the target. As a result, the mean energy and number of accelerated ions increase, thus increasing the energy fluence and intensity of the produced ion beam. Whether this scheme will be effective for the acceleration of heavy and super-heavy ions remains an open question and requires further research. In turn, the CEA mechanism, which often accompanies RPA, can hinder the generation of ultra-intense ion beams, particularly superheavy ion beams. Although CEA can increase the energy of RPA-driven ions, it also leads to a significant increase in the angular divergence of the ion beam. This results in a rapid decline in the beam fluence, intensity, and density with increasing distance from the ion source, thus reducing the ion beam’s application utility.

The basis of ion acceleration mechanisms such as RPA, TNSA, and the others mentioned above is the electromagnetic forces induced in the plasma by a laser. At relativistic laser intensities, they enable the acceleration of ions to energies in the GeV range and higher, and primarily (but not exclusively) these high ion energies result in high ion beam intensities and fluences. In laser-produced plasma, besides EM forces, other forces also exist, particularly hydrodynamic forces. These forces can also effectively accelerate plasma ions. In laser-produced plasma, they dominate the acceleration process at relatively low, nonrelativistic laser intensities (<1016 W/cm2) and are used to accelerate ions (plasmas), driven primarily by nanosecond or sub-nanosecond laser pulses. The best-known and widely used ion (plasma) acceleration mechanism utilizing laser-induced hydrodynamic (thermal) forces is ablation acceleration (AA) [56]. In the AA mechanism, a hot plasma is generated on the surface of a target illuminated by a laser beam. This plasma expands backward and accelerates the remaining portion of the target forward (via the “rocket effect”). The most important application of AA is in ICF research, where it is used to accelerate and compress DT fuel in fusion targets [57,58]. It is also used to accelerate microprojectiles [59,60,61] and in HEDP research, primarily to generate high pressures [58]. The main drawback of the AA mechanism is the relatively low energy efficiency of acceleration, usually on the order of a few percent [56,59,60]. A much more efficient acceleration mechanism utilizing hydrodynamic forces is the so-called LICPA (laser-induced cavity pressure acceleration) mechanism [62,63]. In LICPA, a target placed in a cavity is irradiated by a laser beam introduced into the cavity through a hole and then accelerated in a guiding channel by the pressure of a hot plasma produced in the cavity by the laser beam. It has been shown [63,64] that the efficiency of acceleration of ion (plasma) flux by LICPA is many times higher than by AA and can reach several dozen percent.

Ions accelerated by hydrodynamic forces have relatively low velocities (<108 cm/s) and energies (<0.1 MeV), many orders of magnitude lower than those achieved in EM acceleration. However, ion densities (ni) and areal ion densities (σi) can reach values significantly higher than those achieved in EM acceleration. In accelerators with flat geometry, these values can reach values of ni ~ 1023 cm−3 and σi ~ 1020–1021 cm−2, while in spherical geometry used for plasma compression in ICF research, these values can be even 1–2 orders of magnitude higher. Although the fluences and intensities of ion fluxes accelerated hydrodynamically are much lower than those accelerated by EM forces (due to the much lower ion energies), they are high enough to play a very important role in HEDP and ICF studies. In particular, by impinging an ion flux generated in flat geometry on a solid target, it is possible to generate very high pressures up to Gbar [65,66], while acceleration and compression of the ion flux in spherical geometry can lead to the initiation of nuclear fusion. The above applications, however, require nanosecond or sub-nanosecond laser drivers with very high energies, from ~1 kJ in flat geometry experiments to ~104–106 J in spherical experiments. In this work, we will focus on the generation of intense ion fluxes driven by EM forces induced in plasma by femtosecond laser drivers with energies ≤ 1 kJ and multi-PW powers.

3. Research Method Used to Demonstrate and Investigate the Properties of Laser-Driven Extreme Ion Beams

To demonstrate the ability to generate ultra-intense ion beams using a multi-PW femtosecond laser and to investigate the properties of these beams in detail, we used the results of a series of numerical simulations performed using an advanced particle-in-cell code. The ion beam driver was a multi-PW laser with parameters achievable with current short-pulse laser technology, specifically: laser pulse duration τL = 30 fs (FWHM), circularly polarized beam intensity focused on the target IL = 1023 W/cm2, and laser wavelength λ = 0.8 µm. The laser pulse interacted with a flat uranium target with a width of 16 µm, composed of a solid part with an atomic density of 4.82 × 1022 atoms/cm3 and a pre-plasma with an exponential change in density and a total thickness of 184 nm. The presence of the pre-plasma in front of the main solid part of the target reflects the fact that the intensity contrast of the laser pulse is finite, and the pre-pulse preceding the main part of the pulse can ionize the target surface and generate a plasma. The uranium target was chosen because beams of high-energy superheavy ions such as uranium can be particularly useful in HEDP and nuclear physics research. To reveal the properties of ultra-intense laser-generated ion beams and to investigate the possibility of controlling their parameters, the size of the laser focal spot on the target (from 3 µm to 6 µm) and the thickness of the target solid part (from 7 nm to 100 nm) were varied in simulations, with fixed values of IL and τL and pre-plasma parameters. It is worth adding that the effective pre-plasma thickness (at the 1/e level of density distribution) is ~20 nm, so the actual initial target thickness (before laser exposure) varied in the simulations from ~27 nm to ~120 nm. With current target fabrication technologies, flat targets with such thicknesses are relatively easily achievable (e.g., [67,68]).

The simulations of uranium ion acceleration in plasma generated by the interaction of the laser pulse with the uranium target were performed using a fully electromagnetic, relativistic multi-dimensional (2D3V) particle-in-cell PICDOM code [69]. This code includes, in particular, the dynamic ionization of the laser-irradiated target and the accelerated ions [34,70], as well as the emission of synchrotron radiation by relativistic electrons produced in the plasma by the laser [71,72,73,74]. To model the ionization process, it was assumed that the process is dominated by field ionization, and its quantitative description was described using the Ammosov-Delone-Krainov formula [75]. This assumption is justified by the fact that the energies of fast electrons generated by lasers in plasma at laser intensities of ~1023 W/cm2 are very high (from tens to even hundreds of MeV [15,76]), while the average plasma density (below 1021 cm−3) and size (~10–20 µm) in the cases studied here are relatively small. As a result, the probability of electron-ion collisions is very low, and therefore processes such as collisional ionization of atoms/ions, electron-ion recombination, or bremsstrahlung radiation can be omitted in numerical modelling ion acceleration (see, e.g., [71,72,73]). This allows simulations to be performed with lower computational power and in much shorter time. For numerical modelling of synchrotron radiation emission accompanying ion acceleration at very high laser intensities and calculations of radiative losses associated with this emission, the well-known Sokolov model [77] was used.

The simulations were carried out in the x-y plane with dimensions of 70 μm × 20 μm (the x-axis is parallel to the direction of laser beam propagation). The time and spatial steps were 2.2 as and 6 nm, respectively, and the number of uranium macroparticles per cell was 50 particles. The total number of uranium particles in the simulation depended on the thickness of the uranium target and ranged from 777,431 to 2,667,000. The number of electron macroparticles changed during the simulation with the change of the ion ionization levels and was equal to the number of uranium macroparticles multiplied by the current average ion ionization level. To account for the fact that the ion beam propagates in three-dimensional (3D) space, a 3D correction [19,76,78] was applied when determining the absolute values of the beam parameters. When calculating this correction, it was assumed that the movement of ions in the x-z plane perpendicular to the x-y simulation plane was identical to that in the simulation plane. As shown in the discussion in Section 6, when RPA is the dominant acceleration mechanism, the differences between the values of beam parameters such as ion energy, beam intensity and beam fluence obtained from 2D and 3D simulations are usually not very large (paradoxically, 2D simulations often give values of these parameters that are slightly lower than those from 3D simulations). Therefore, we can believe that the results of our simulations, enriched with the 3D correction, are sufficiently accurate for the purposes of this work.

4. Properties of a Uranium Ion Beam Driven by a Multi-PW Femtosecond Laser

In this section, we will demonstrate the feasibility of generating uranium ion beams with ultrahigh intensities and fluences using a multi-PW laser and present the basic properties of these beams. We will also examine whether it is possible to effectively control the parameters of these beams by varying certain laser and target parameters. In Section 4.1, we will examine the effect of the laser focal spot size on the properties of a uranium ion beam, and in Section 4.2, we will demonstrate how the beam properties change with varying the uranium target thickness.

4.1. The Effect of the Laser Focal Spot Size on the Properties of the Uranium Ion Beam

To investigate the effect of the laser focal spot size, dL, on the properties of a uranium ion beam and to assess the effectiveness of beam parameter control by varying the dL value, numerical simulations were performed for four values of this parameter (dL = 3 µm, 4 µm, 5 µm, and 6 µm) at a fixed laser intensity of 1023 W/cm2 and a laser pulse duration of τL = 30 fs. The influence of dL on the ionization and energy spectra of uranium ions, the spatial and angular distributions of ion fluence, the temporal distributions of beam intensity, and the global characteristics of the ion beam, such as peak intensity, peak fluence, and energy, was analyzed.

For superheavy ions such as uranium, the ionization spectrum is an important characteristic of the laser-generated ion beam. This is primarily because the efficiency of ion acceleration in laser-induced electric fields in plasma depends significantly on the ratio of the ion charge q to its mass m, i.e., on q/m = Z/A, where Z is the charge state of the ion and A is its atomic mass. In the case of targets with a low atomic number Zat (e.g., a carbon target), even at moderate laser intensities of ~1020–1021 W/cm2, virtually all atoms of the thin target are completely ionized by the laser beam, and for most accelerated ions, Z/A = 1/2. In the case of targets containing super-heavy atoms, even at ultra-high intensities ≥ 1023 W/cm2, the ionization process takes much longer; the atoms are not completely ionized, and there are usually several dozen types of ions with different q/m = Z/A < 1/2. As a result, super-heavy ions are accelerated less efficiently than light ions, and the acceleration efficiency for different ion types (ions with different Z) is different. This is a significant obstacle to achieving high-efficiency acceleration and producing a high-quality ion beam. Detailed knowledge of the ionization spectrum and its possible control towards a monocharged beam is crucial for producing a high-quality super-heavy ion beam.

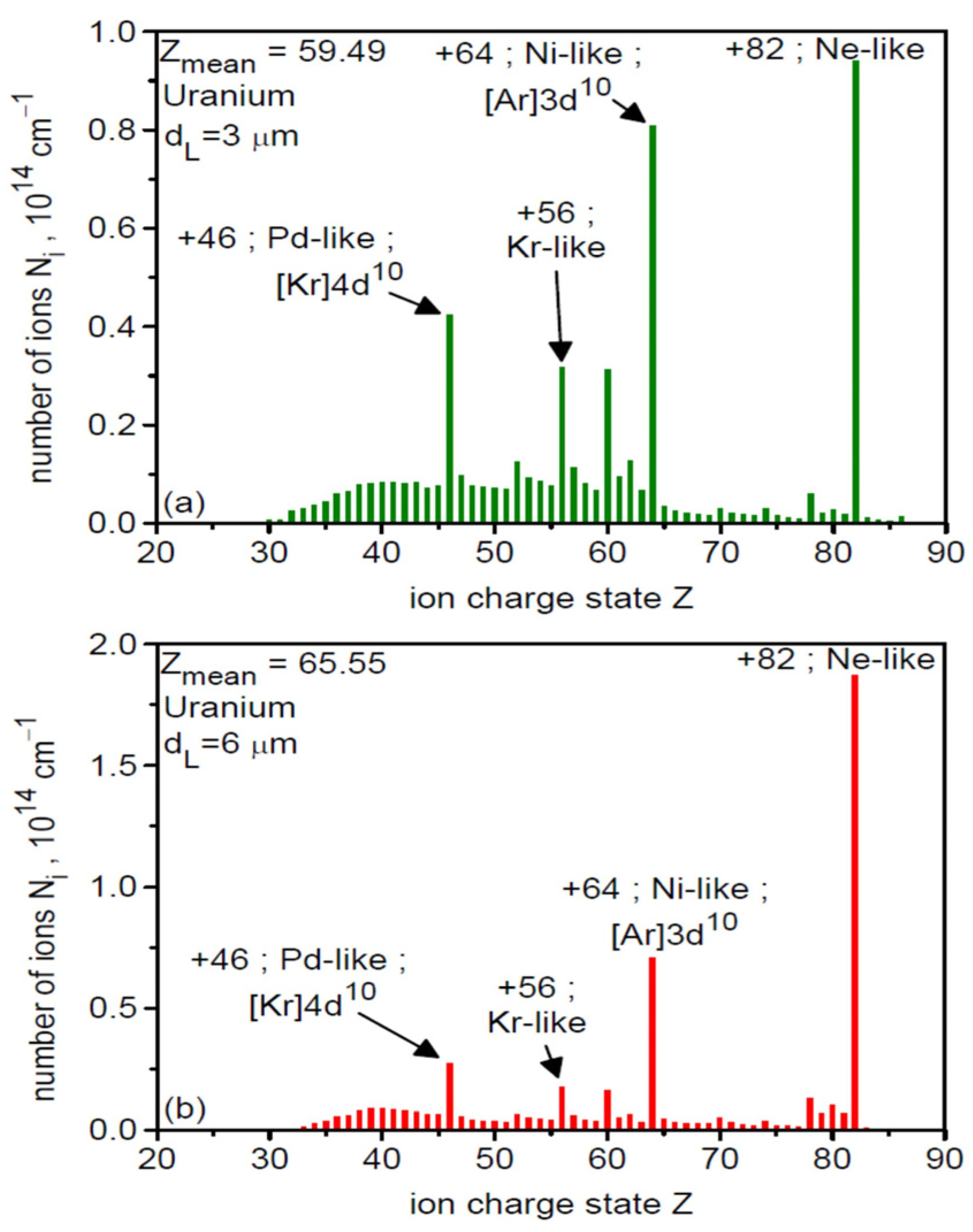

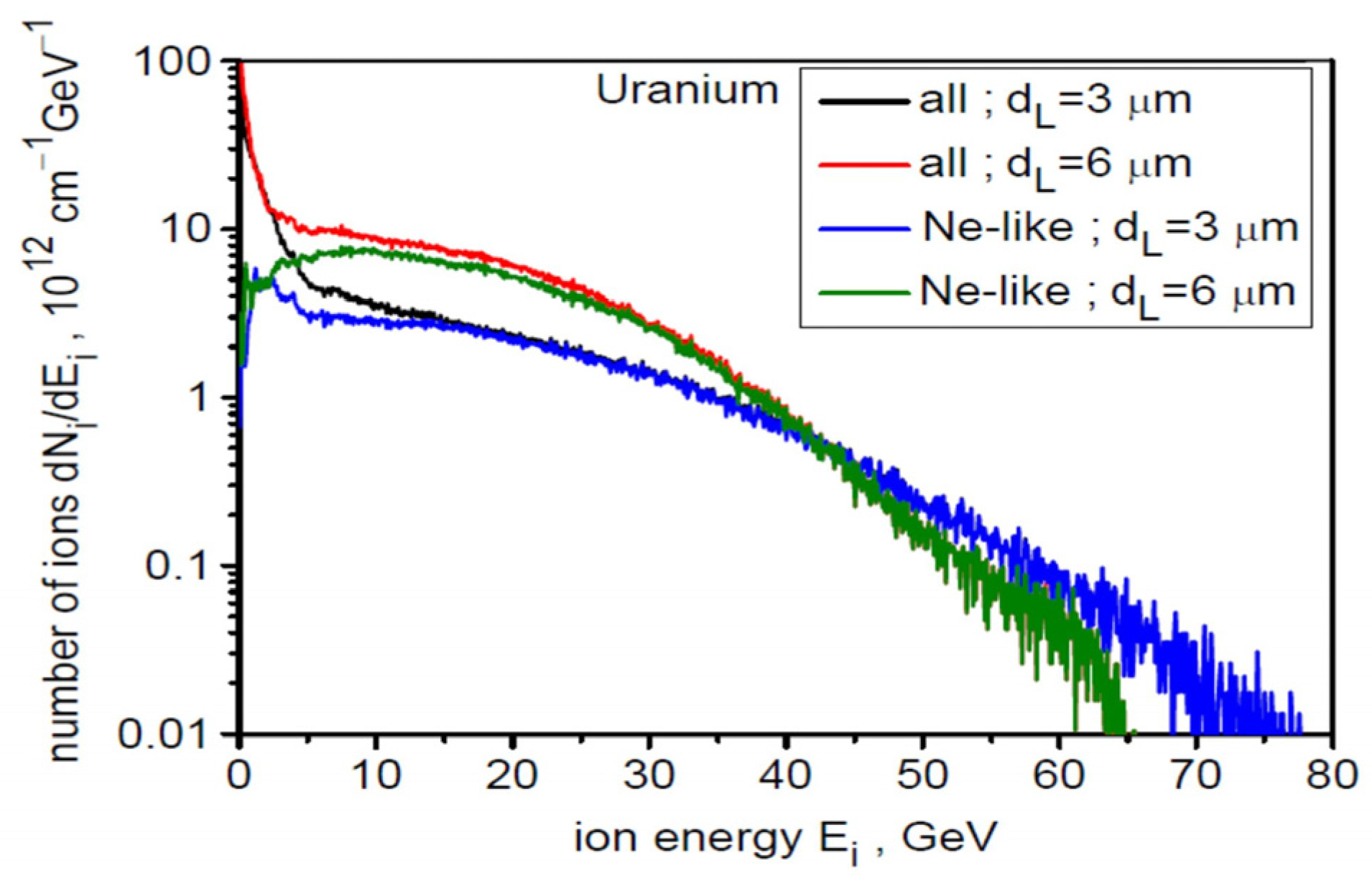

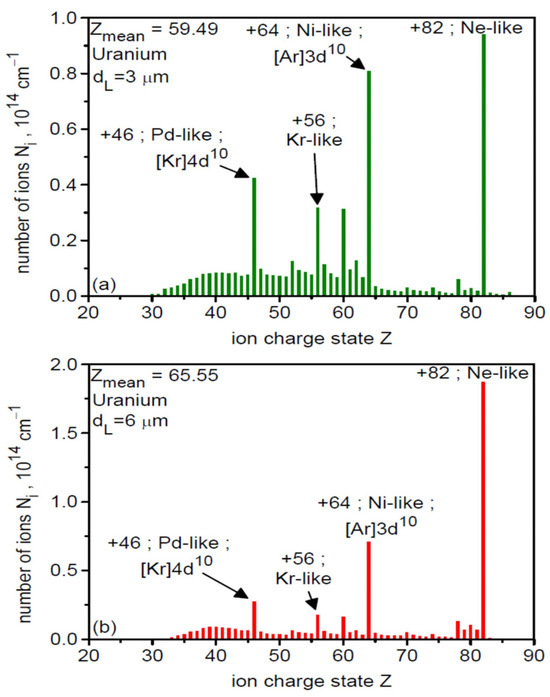

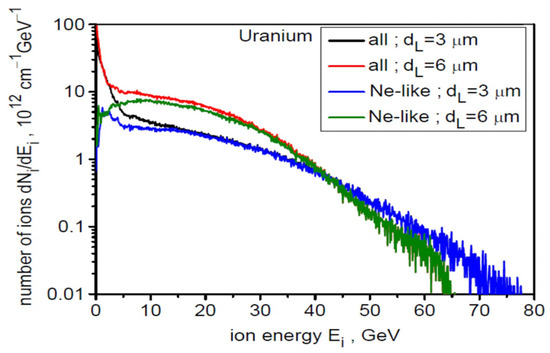

Figure 1 shows the ionization spectra of uranium ions in the final stage of acceleration (t = 8τL = 240 fs) for two laser focal spot sizes of 3 µm (a) and 6 µm (b). As can be seen, the spectral structure is similar in both cases: several dozen ion types with different charge states Z are generated, with the largest population being Ne-like ions with Z = 82. Because Ne-like ions have the highest Z/A ratio among the highly populated ions, they are accelerated most efficiently and thus have the highest energy (both mean and maximum) and carry a substantial portion of the energy deposited by the laser in the ion beam. This is clearly seen in Figure 2, which shows the energy spectra for all ions in the generated beam (red and black curves) and for the Ne-like ion group (green and blue). The high-energy part of the spectrum (Ei > 10 GeV) is completely dominated by Ne-like ions for both dL values, with the maximum energy of these ions being slightly higher for dL = 3 µm and reaching 80 GeV.

Figure 1.

The ionization spectra of uranium ions in the final stage of acceleration (t = 240 fs) for two laser focal spot sizes of 3 µm (a) and 6 µm (b). The target thickness LT = 50 nm.

Figure 2.

The energy spectra for all ions in the generated beam (red and black curves) and for the Ne-like ion group (green and blue) for two laser focal spot sizes of 3 µm and 6 µm. LT = 50 nm, t = 240 fs.

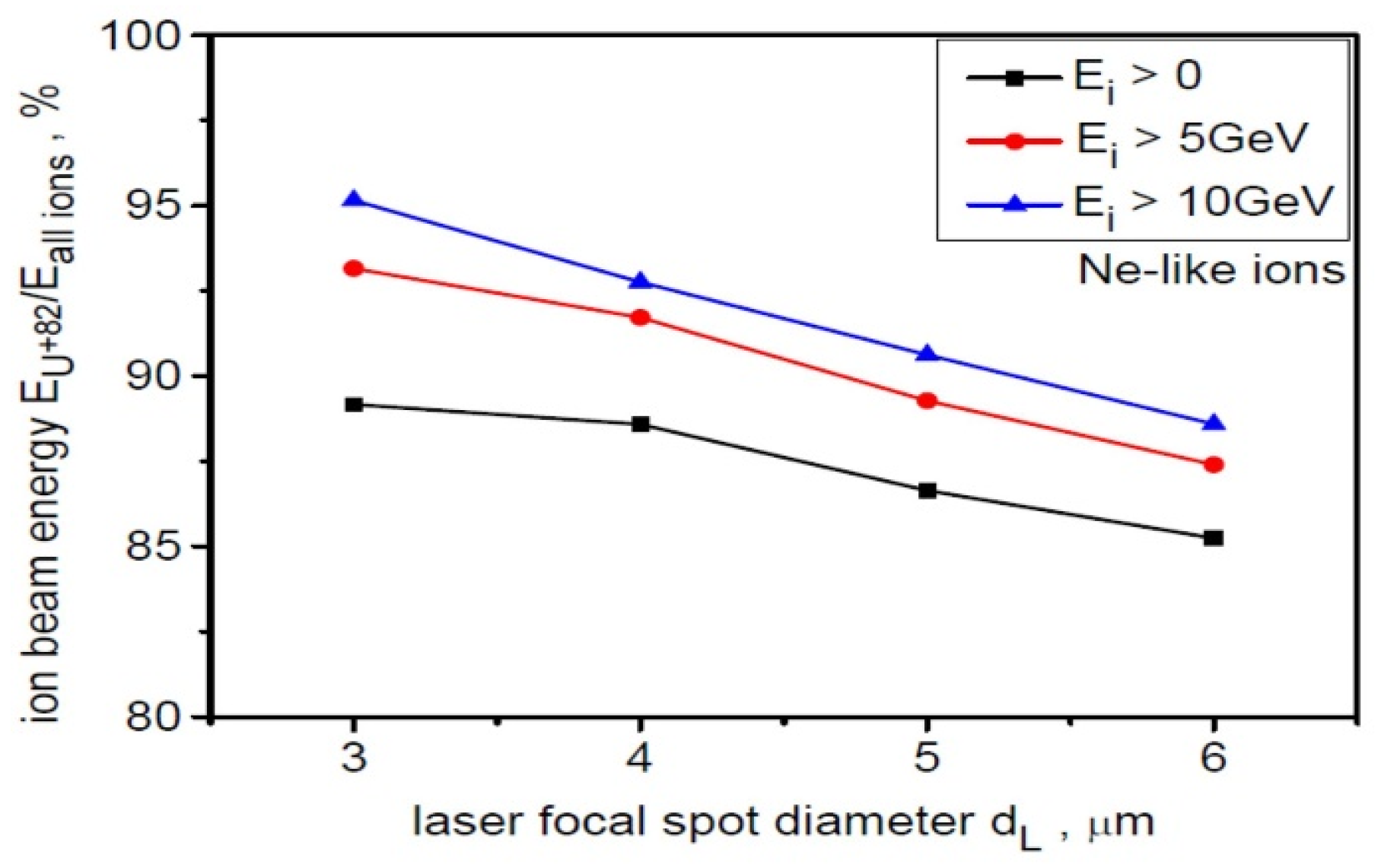

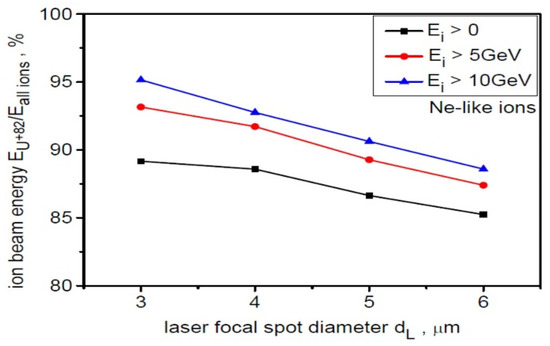

The percentage share of energy carried by Ne-like ions relative to the energy of all ions as a function of the laser focal spot size for various ion energy ranges is shown in Figure 3. This share decreases slightly with increasing dL but increases with increasing ion energy, and for the high-energy part of the energy spectrum, it can significantly exceed 90%. The ion beam is therefore practically mono-charged, with a dominant charge state of Z = 82. As our studies (not presented here) have shown, the mono-charge of the beam can be further increased by separating its paraxial part of size ~ dL from the beam. In this case, Ne-like ions can carry over 98% of the energy stored in the paraxial beam.

Figure 3.

The percentage share of energy carried by Ne-like ions relative to the energy of all ions as a function of the laser focal spot size for various ion energy ranges. LT = 50 nm, t = 240 fs.

The mono-charged nature of a beam of super-heavy ions such as uranium, demonstrated above, is an important feature from the point of view of their potential applications, for example, in HEDP. It allows for better concentration of the beam energy in the irradiated material and facilitates the interpretation of beam-target interaction measurements. The physical causes and conditions necessary for generating a mono-charged beam of super-heavy ions are discussed in [79]. It has been shown that the generation of such beams is possible when the laser intensity is properly matched to the energy level structure of the super-heavy atom. In the case of uranium, generation of a beam dominated by Ne-like ions is possible at intensities of ~(1–2.4) × 1023 W/cm2, i.e., in a quite wide range of intensities. For super-heavy ions with lower mass numbers (e.g., Au, Pb, Bi), the laser intensities required to generate Ne-like beams are lower than for uranium, but still well above 1022 W/cm2 [79].

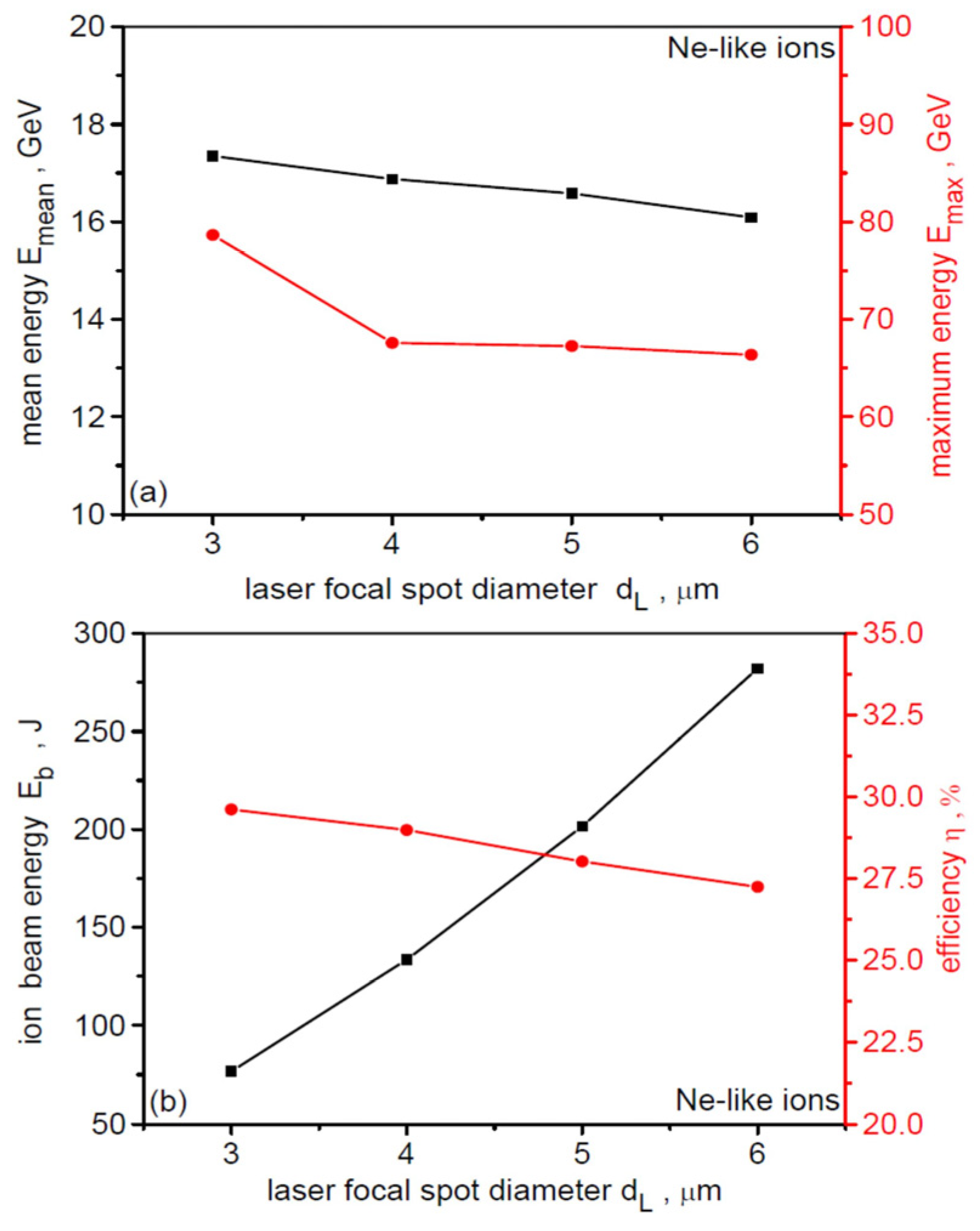

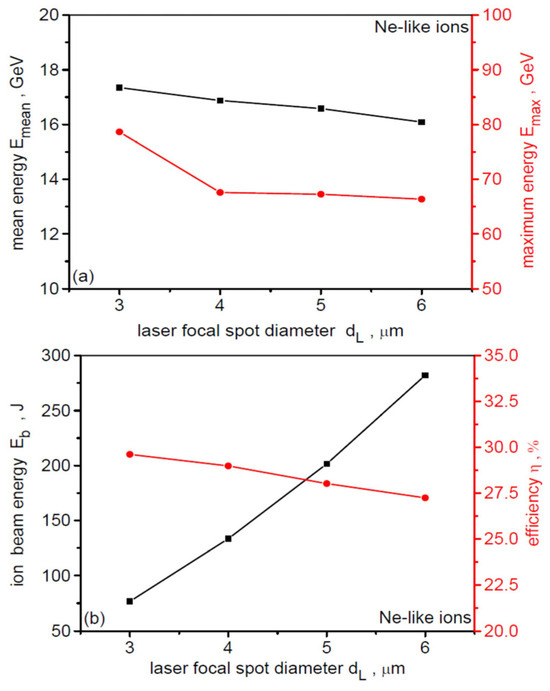

Figure 4 shows the dependence of the mean (Emean) and maximum (Emax) energy of Ne-like ions (a), as well as the Ne-like ion beam energy (Eb) and the laser-to-Ne-like ion energy conversion efficiency (η) (b), on the laser focal spot size. Increasing dL leads to a decrease in the values of Emean and Emax, but the change in these values is small—less than 10% for Emean and ~15% for Emax. Controlling the Ne-like ion energy by changing dL is therefore ineffective. The energy conversion efficiency η is almost independent of dL and is very high—close to 30%. However, the beam energy Eb increases almost parabolically with dL, which is understandable, because at a constant laser intensity, the laser beam energy increases proportionally to dL2.

Figure 4.

The dependence of the mean and maximum energy of Ne-like ions (a), as well as the Ne-like ion beam energy and the laser-to-Ne-like ions energy conversion efficiency (b), on the laser focal spot size. LT = 50 nm, t = 240 fs.

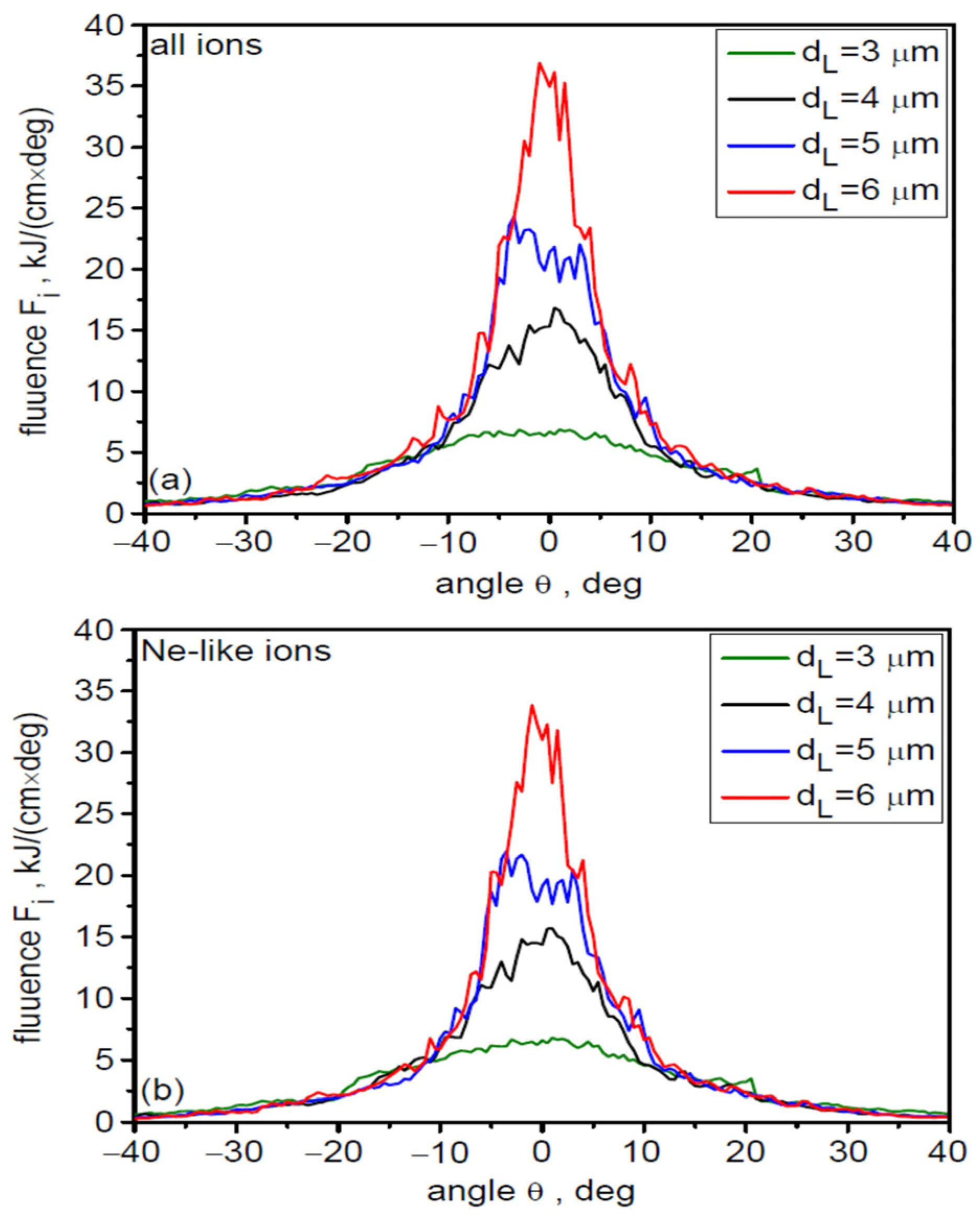

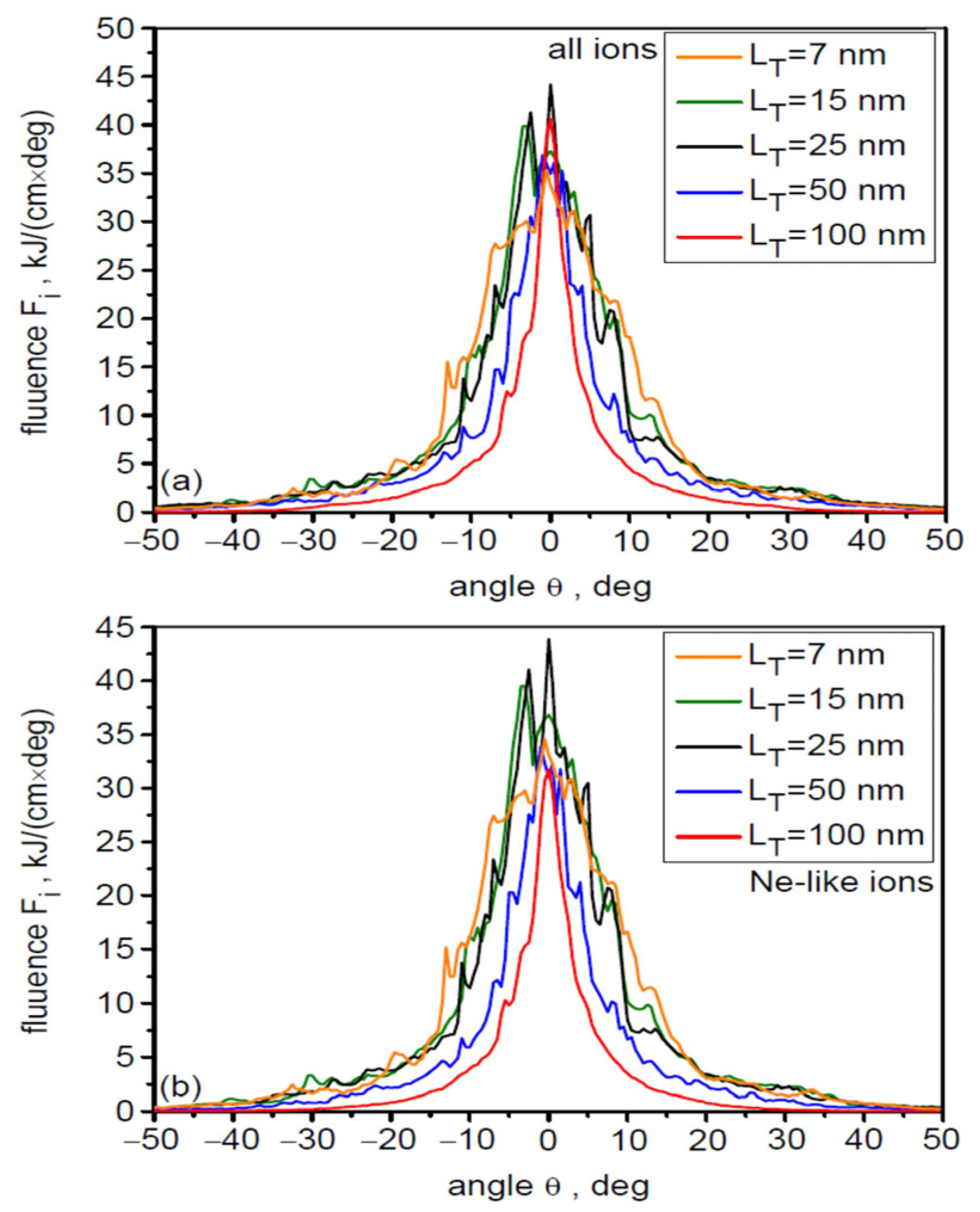

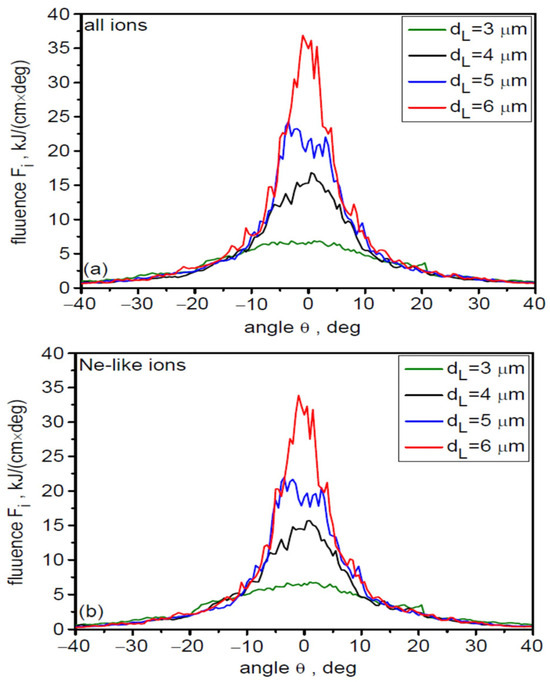

As already mentioned in Section 2, an important parameter of the ion beam, largely determining its practical usefulness, is the beam’s angular divergence. The angular distribution of the fluences of all accelerated uranium ions (a) and Ne-like ions (b) for different values of the laser focal spot size is shown in Figure 5. Both distributions are practically identical. This proves that the beam is mono-charged not only in terms of the energy carried by Ne-like ions, but also that other beam characteristics are completely dominated by this type of ion. The beam’s angular divergence clearly decreases with increasing dL, from ~30 degrees (FWHM) for dL = 3 µm to ~10 degrees for dL = 6 µm. The main cause of the observed changes in angular divergence is the decreasing gradient of laser intensity changes near the laser beam axis with increasing dL. The increase in peak fluence value with dL is primarily the result of increasing beam energy with increasing dL.

Figure 5.

The angular distribution of the fluences of all accelerated uranium ions (a) and Ne-like ions (b) for different values of the laser focal spot size. LT = 50 nm, t = 240 fs.

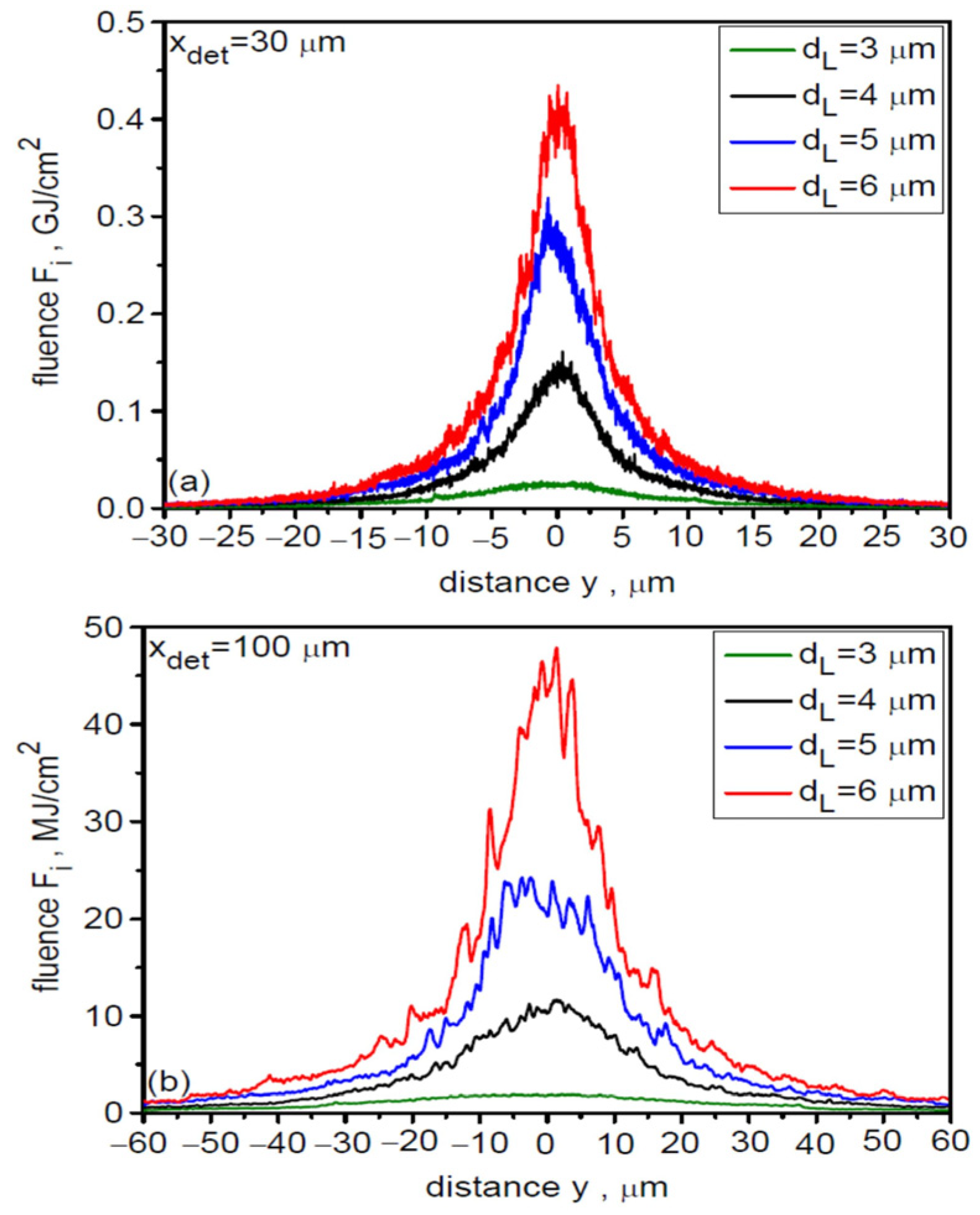

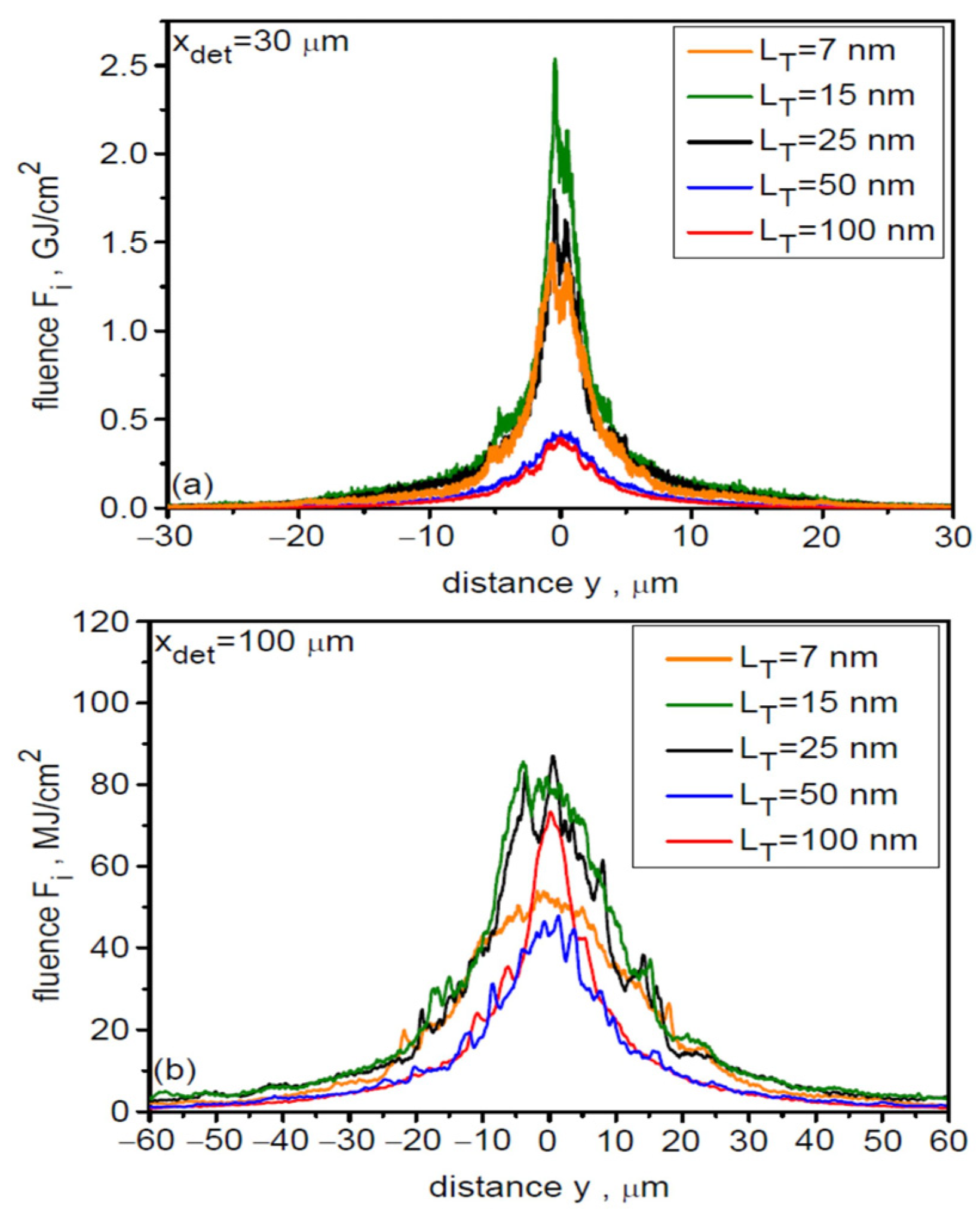

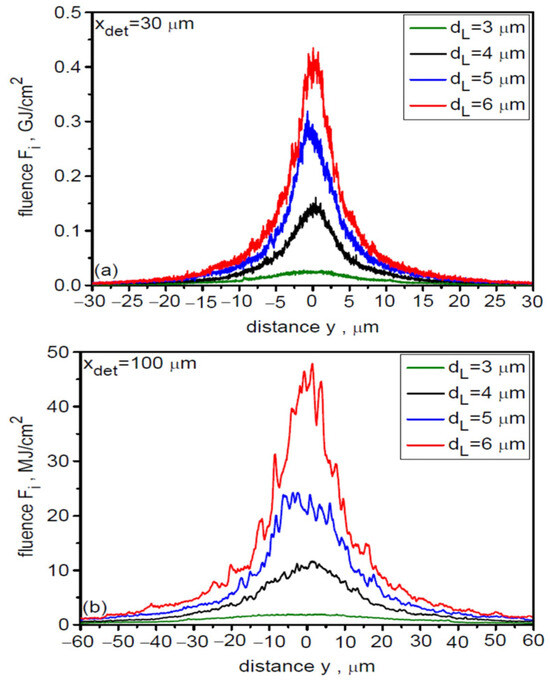

The non-zero angular divergence of the ion beam causes the lateral distribution (along the y and z axes) of the beam fluence to broaden and the peak fluence value to decrease with increasing distance from the target. This is illustrated in Figure 6, which shows the spatial distributions (along the y axis) of fluence for various dL at distances of 30 µm (a) and 100 µm (b) from the target. When determining the absolute fluence values in these distributions, a 3D correction was used to account for the fact that the ion beam propagates in three-dimensional space. With increasing distance from the target, the distribution broadens and the peak fluence decreases quite quickly, but also the difference between the peak fluence for large and small dL increases, which is the result of different angular divergences of beams with different dL.

Figure 6.

The spatial distributions of fluence for various laser focal spot sizes at distances of 30 µm (a) and 100 µm (b) from the target. LT = 50 nm, t = 240 fs.

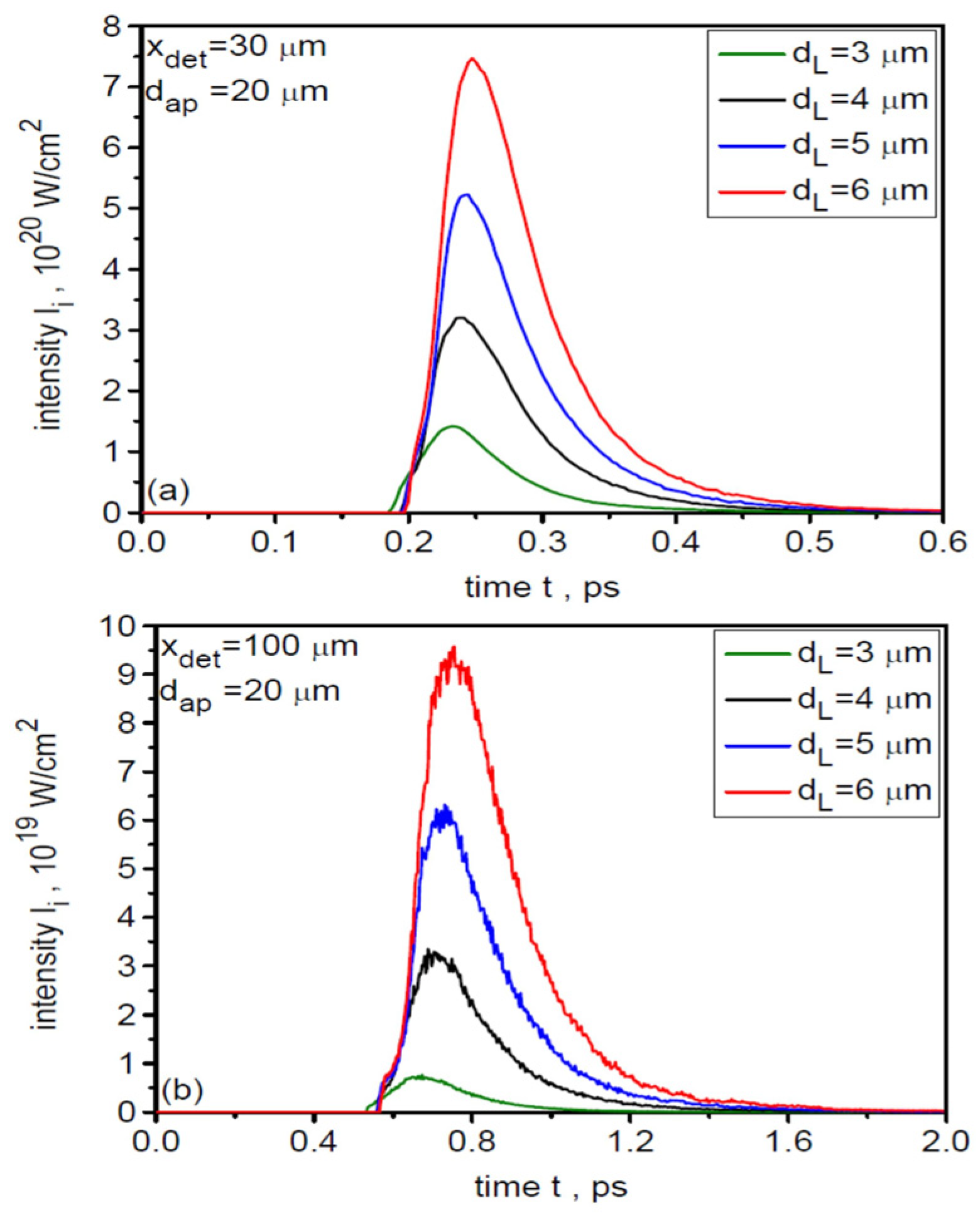

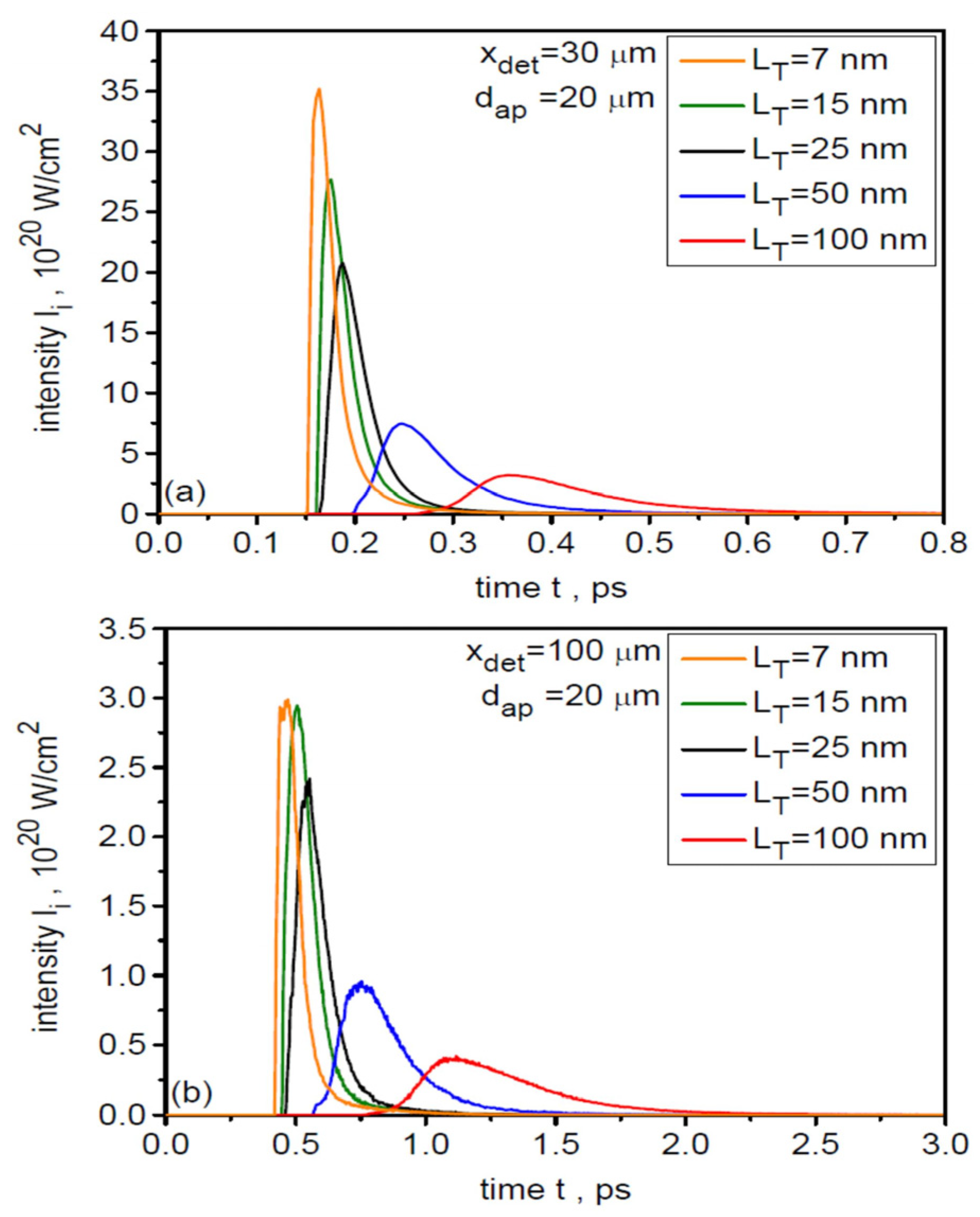

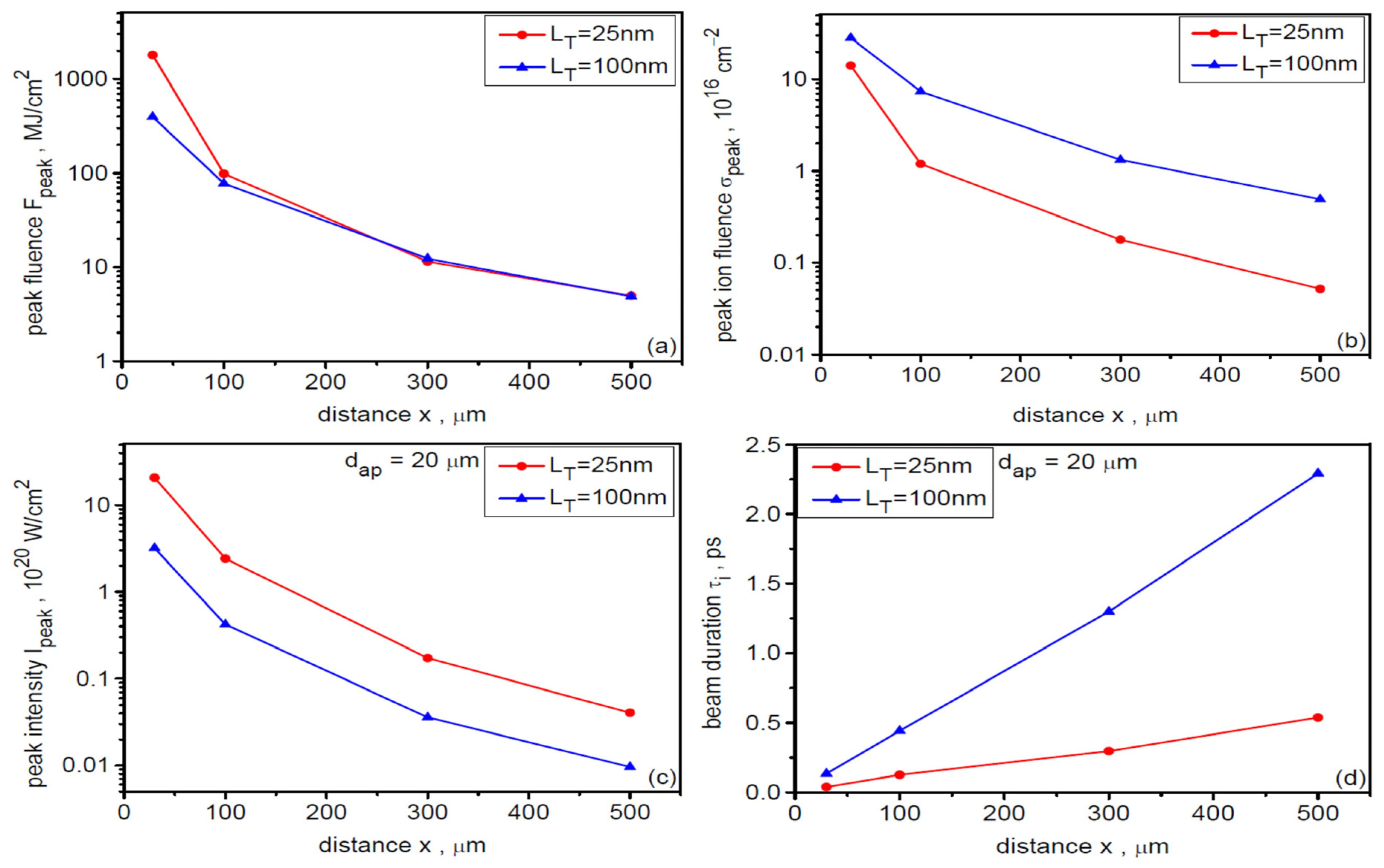

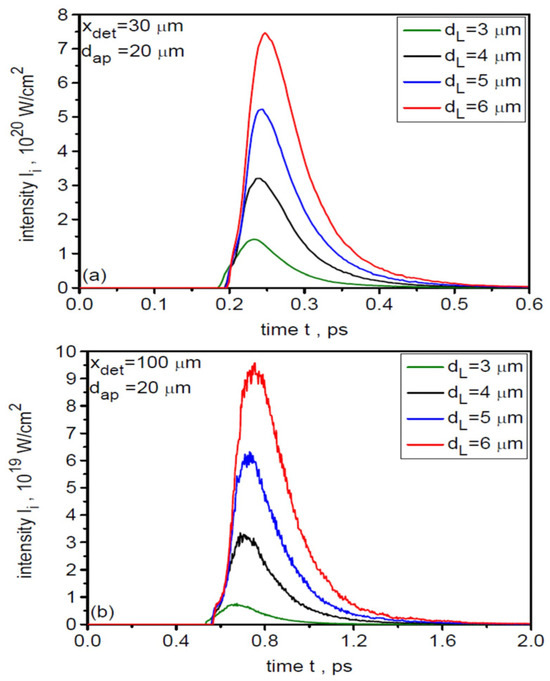

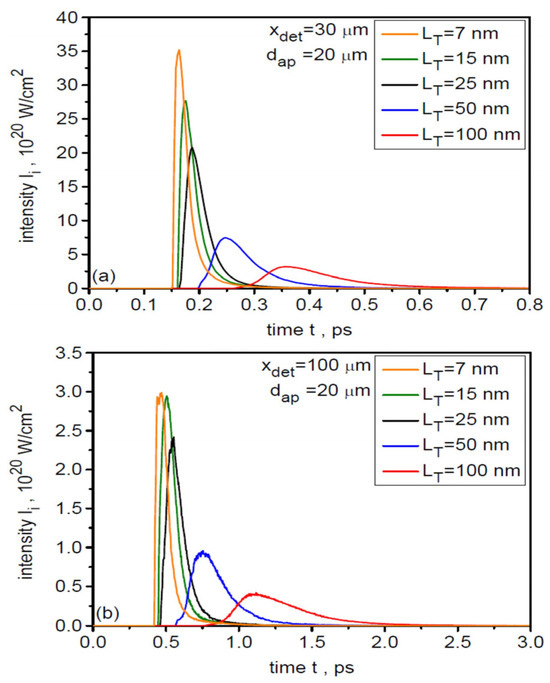

In studies of ion beam interactions with matter, an important beam characteristic that largely determines the course of the interaction process is the temporal shape of the beam intensity and the ion pulse duration. Figure 7 shows the temporal distributions of the uranium ion beam intensity (averaged over a 20-µm region) at distances x = 30 µm and 100 µm from the target for various laser focal spot sizes. A 3D correction was applied to determine the absolute intensity values in these distributions. As dL increases, the peak intensity of the ion pulse increases quite rapidly (primarily due to the increase in laser energy), while its duration changes only slightly and is very short, even shorter than the laser pulse duration. Changing the distance from the target from 30 µm to 100 µm leads to a decrease in the peak intensity by about an order of magnitude and a lengthening of the ion pulse from ~0.08 ps (FWHM) to ~0.25 ps. The change in peak intensity with increasing x is a result of both the non-zero angular divergence of the ion beam and ion velocity dispersion, while the lengthening of the ion pulse is caused by ion velocity dispersion.

Figure 7.

The temporal distributions of the uranium ion beam intensity (averaged over a 20-µm region) at distances x = 30 µm (a) and 100 µm (b) from the target for various laser focal spot sizes. LT = 50 nm.

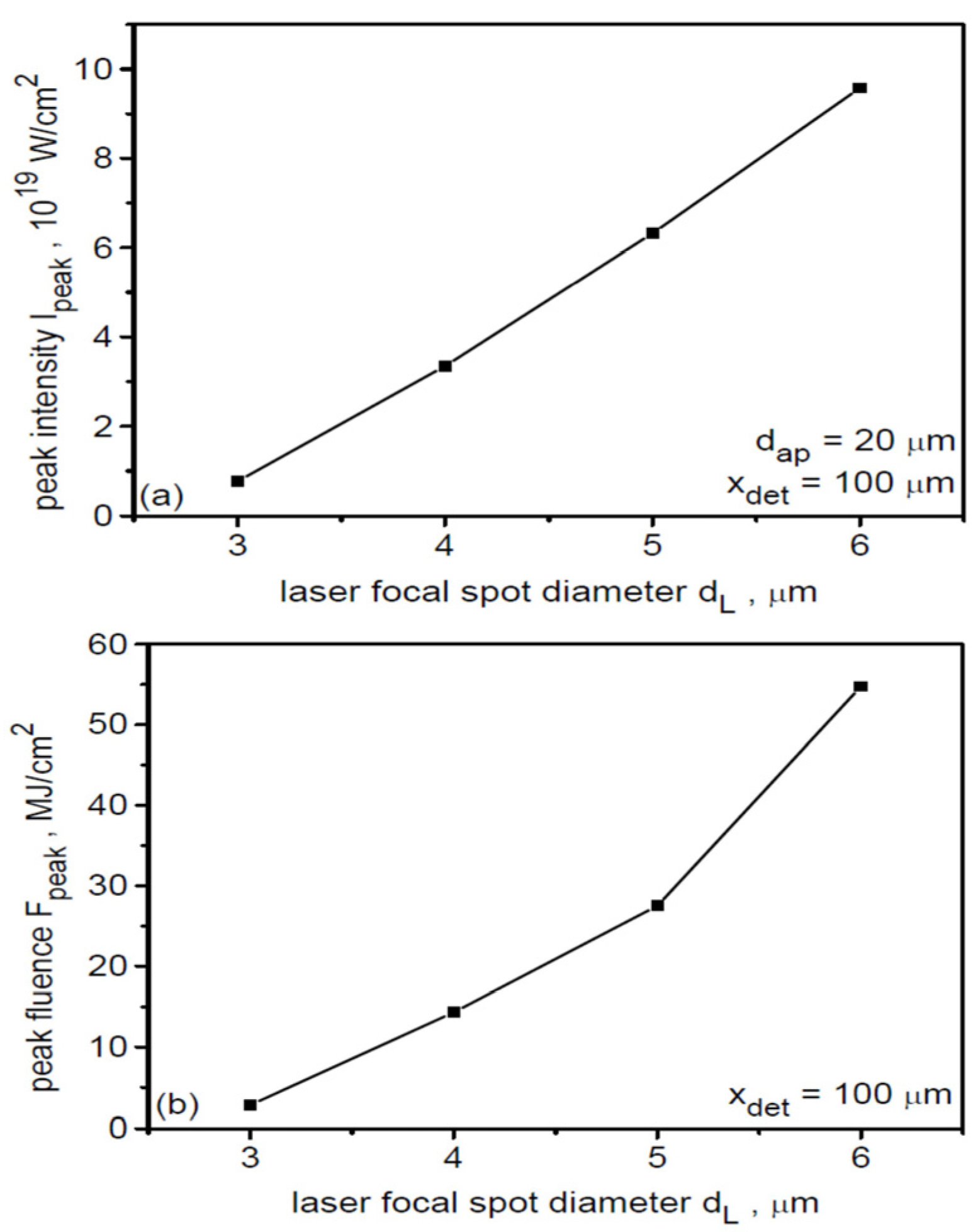

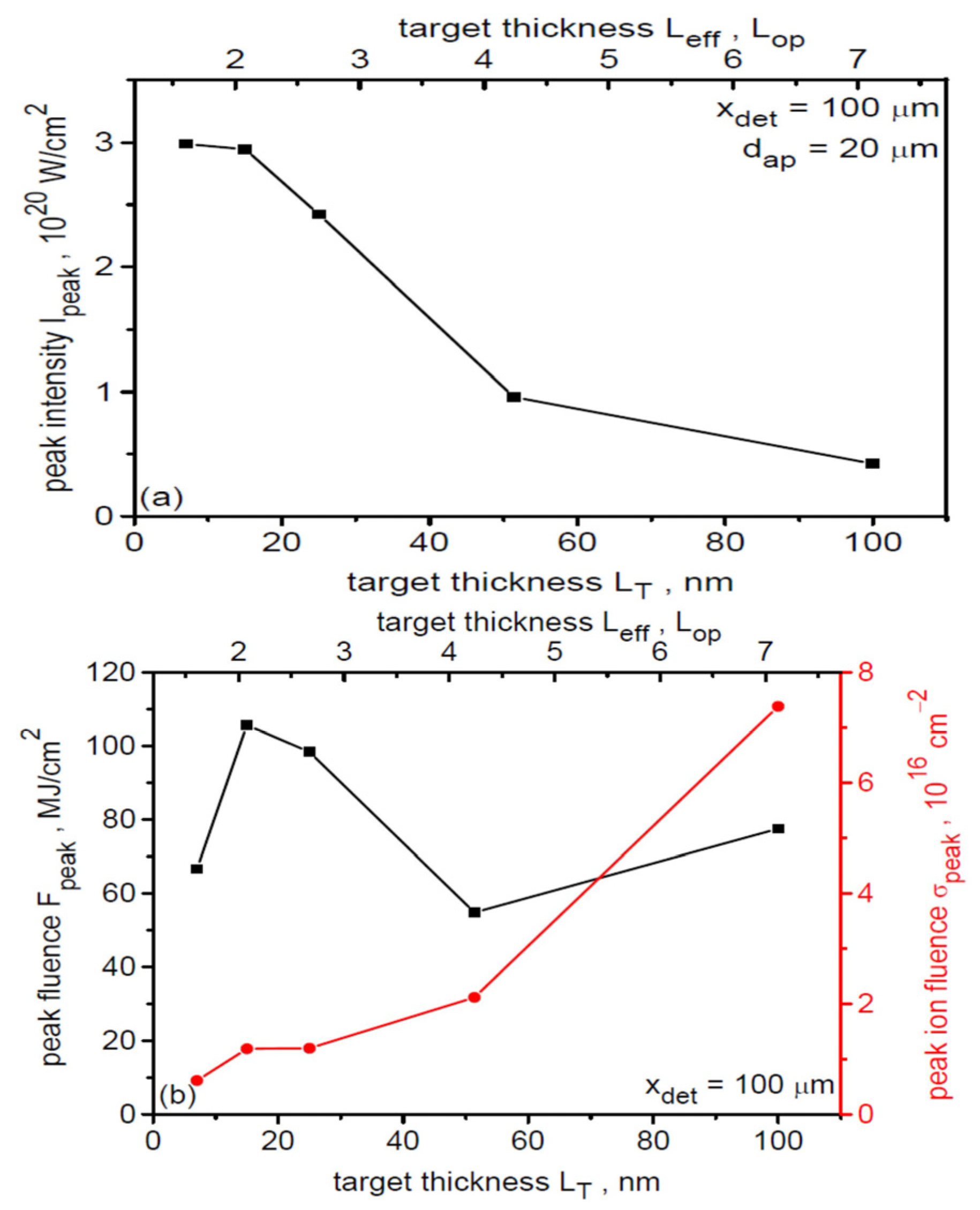

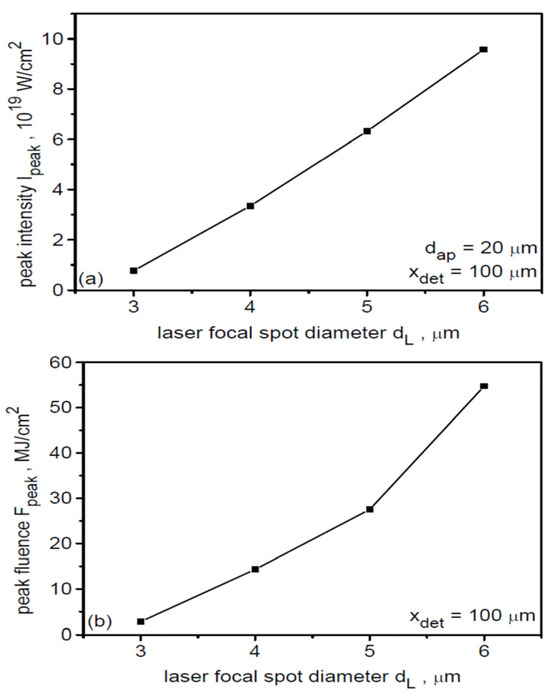

A quantitative summary of the changes in the peak intensity and peak fluence of the ion beam with variations in the laser focal spot size at distances from the target much larger than the initial ion source size (x = 100 µm > 10 dL) is presented in Figure 8. Both parameters increase very rapidly with increasing dL: changing dL from 3 μm to 6 μm results in increases in Ipeak and Fpeak by more than an order of magnitude.

Figure 8.

The peak intensity (a) and peak energy fluence (b) of the ion beam as a function of the laser focal spot size at the distance of 100 µm from the target. LT = 50 nm, t = 240 fs.

In summary, changing the laser focal spot size dL at a fixed laser intensity and target thickness leads to small changes in the mean and maximum energy of uranium ions and the laser-to-ions energy conversion efficiency. Therefore, changing dL is not an effective way to control ion energy over a wide range. On the other hand, the dL variation results in very rapid changes in the peak intensity and peak fluence of the ion beam and can generally be used to control these beam parameters in possible beam-target interaction studies. It should be noted, however, that rapid changes in ion beam fluence and intensity with dL at fixed IL and LT require changes in laser energy, which is a definite disadvantage of this method of controlling these ion beam parameters.

4.2. The Effect of the Target Thickness on the Properties of the Uranium Ion Beam

Modern target technology enables the production of high-quality targets of various thicknesses, shapes, and structures [67,68], including flat high-Z metal targets with thicknesses ranging from a few nm to several hundred nm, which are particularly desirable for laser acceleration of super-heavy ions [7]. It is well known that changing the target thickness leads to changes in the properties of the generated ion beam, but the magnitude and dynamics of these changes strongly depend on the laser parameters and the type of accelerated ions. To assess whether varying the target thickness allows for effective control of ion beam parameters, it is necessary to analyze the quantitative changes in these parameters at fixed laser parameters. In this subsection, we will investigate how changing the thickness of a uranium target illuminated with a 30-fs laser pulse with an intensity of 1023 W/cm2 and a laser focal spot size of 6 µm affects the uranium ion beam parameters crucial for ultra-intense ion beams and their possible applications. Given a fixed uranium pre-plasma density profile and its total thickness of 184 nm (see Section 3), the thickness of the solid part LT of the target was varied from 7 nm to 100 nm. Since the effective pre-plasma thickness (at 1/e maximum density) was ~20 nm, the effective uranium target thickness Leff varied from ~20 + 7 nm to ~20 + 100 nm.

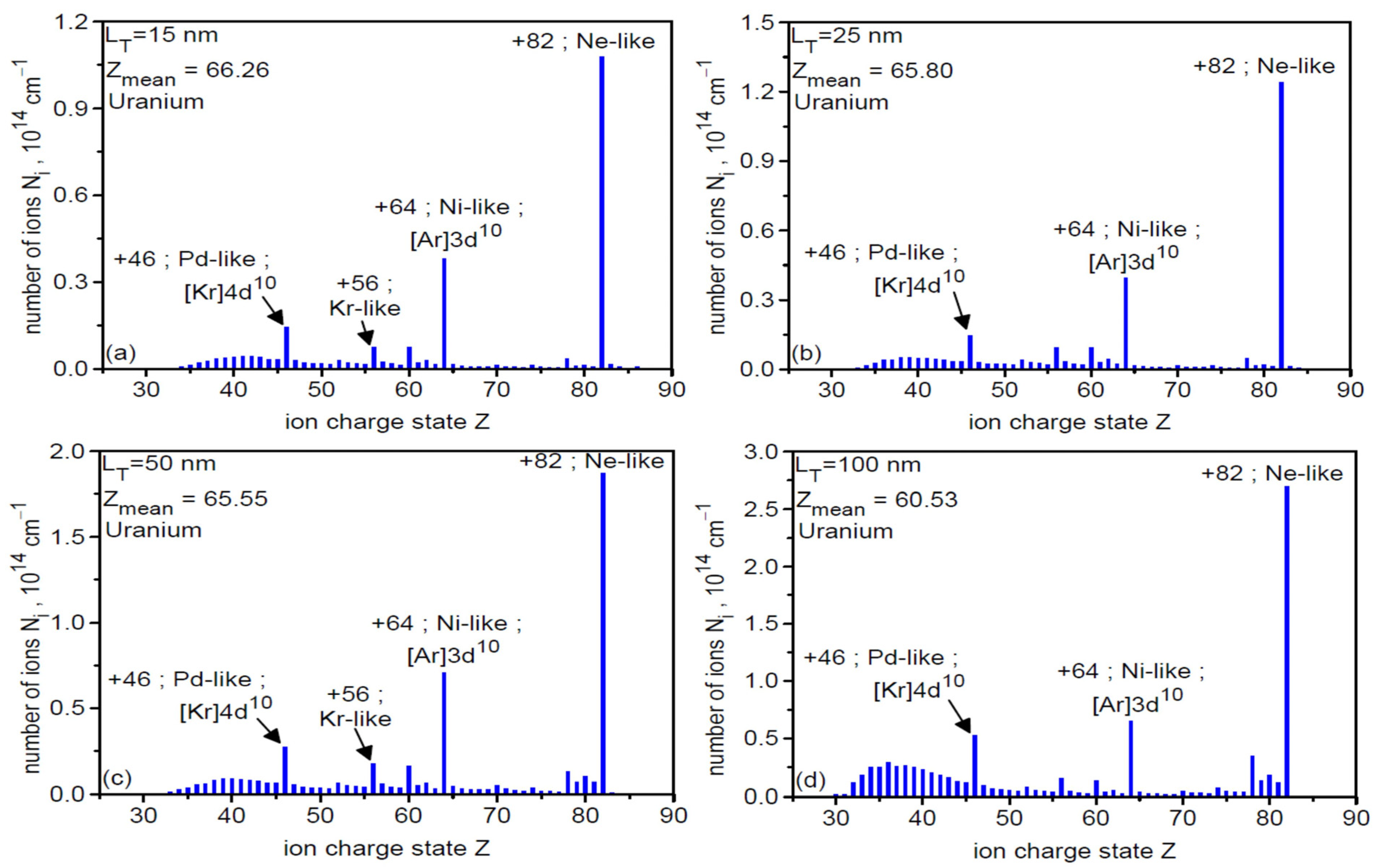

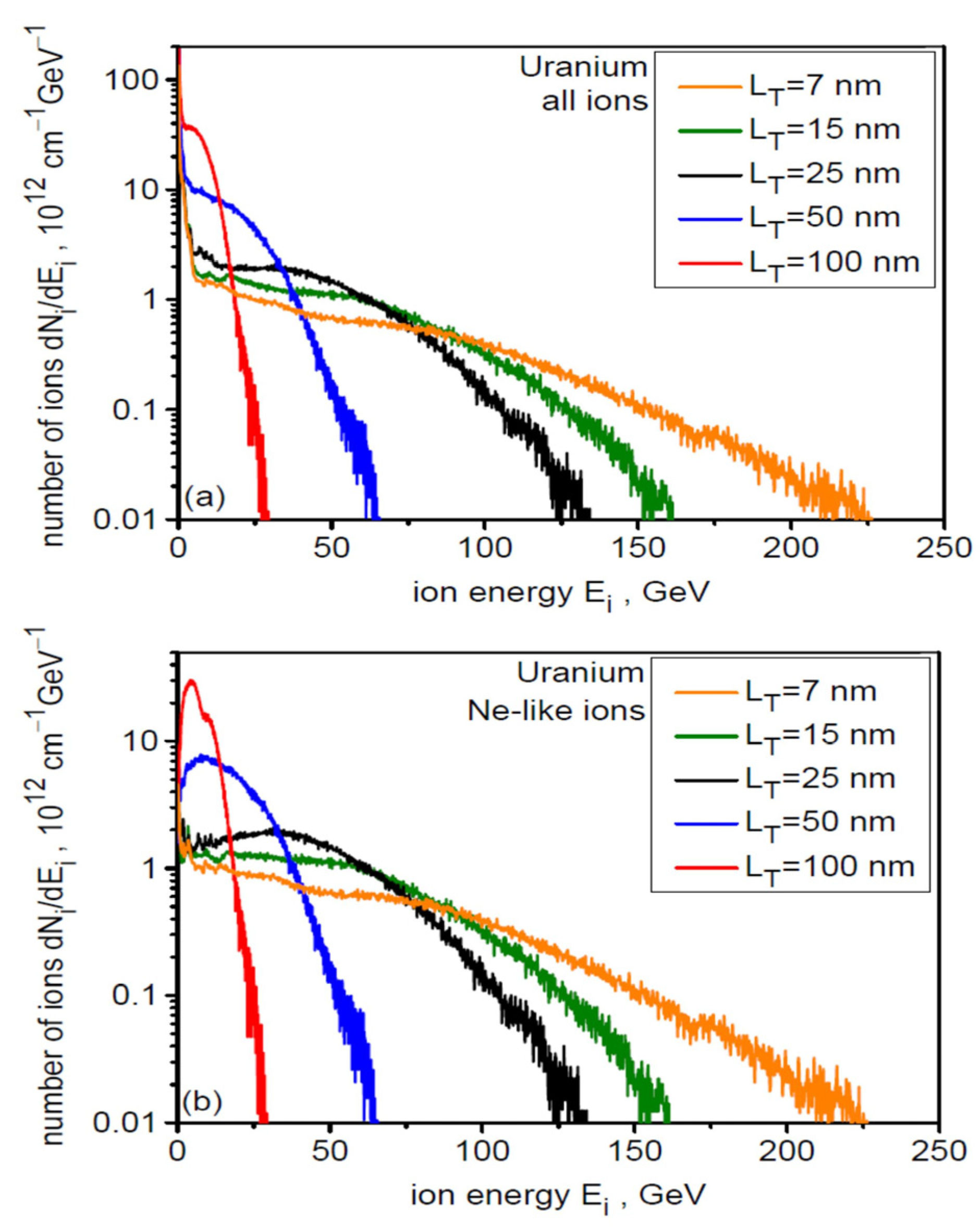

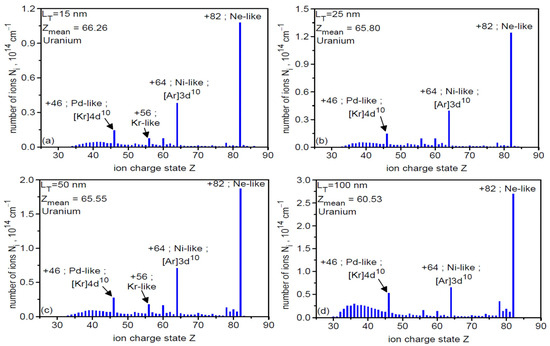

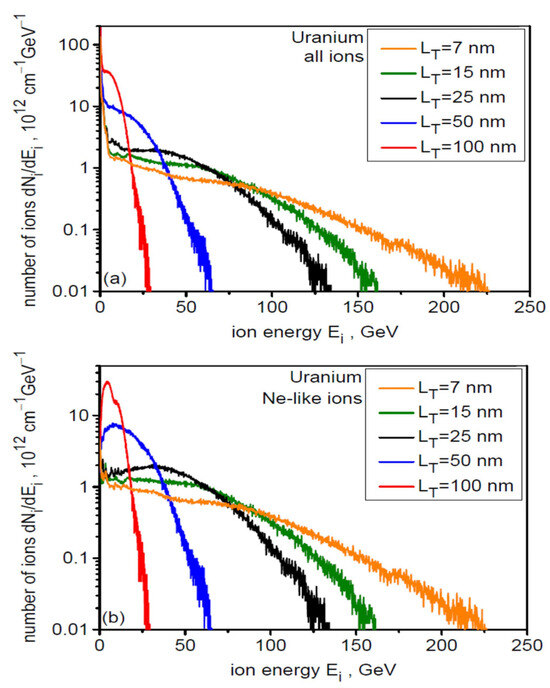

Figure 9 presents the ionization spectra of U ions in the final stage of acceleration for four different uranium target thicknesses (its solid part) LT. The general structure of the spectrum is practically independent of LT, whereas the populations of individual ion species (ions with a given Z) depend on the target thickness. In all cases considered, the most numerous are Ne-like ions (Z = 82), which, due to the highest Z/A ratio, should be accelerated most efficiently. This is confirmed by Figure 10, which presents the energy spectra for all accelerated ion species (a) and for Ne-like ions (b) for six thicknesses of the constant target part LT. As can be seen from the figure, the high-energy part of the spectrum is completely dominated by Ne-like ions regardless of the target thickness, with the highest ion energies achieved with the thinnest targets.

Figure 9.

The ionization spectra of uranium ions in the final stage of acceleration for four different uranium target thicknesses (LT = 15 nm (a), LT = 25 nm (b), LT = 50 nm (c), LT = 100 nm (d)). The laser focal spot size dL = 6 µm, t = 240 fs.

Figure 10.

The energy spectra for all accelerated ion species (a) and for Ne-like ions (b) for different uranium target thicknesses LT. dL = 6 µm, t = 240 fs.

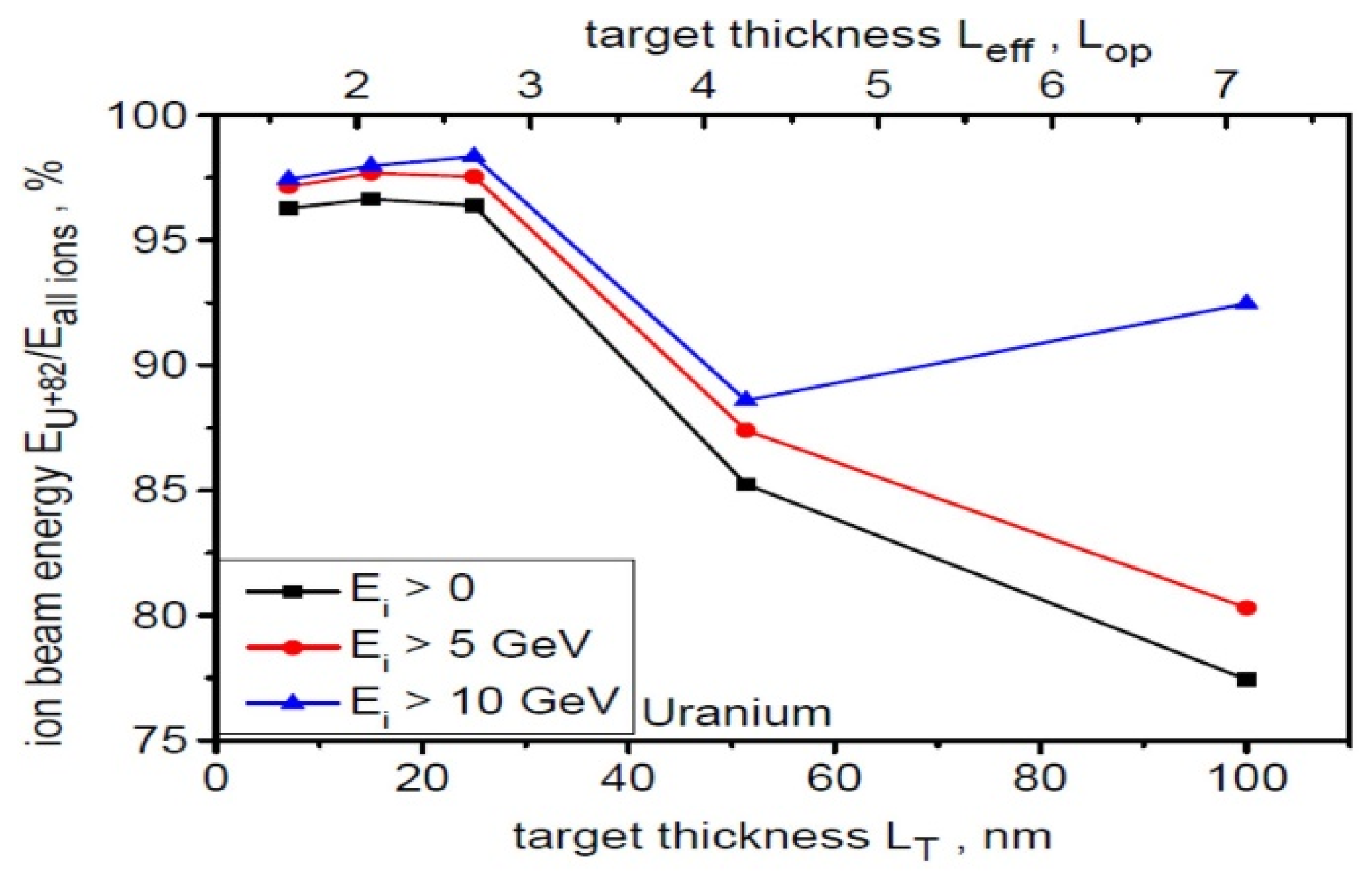

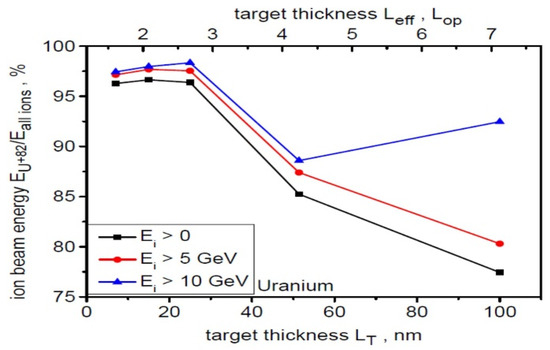

The quantitative contribution (in percentage) of the energy carried by Ne-like ions to the energy of the entire uranium beam as a function of target thickness for three ion energy ranges is presented in Figure 11. The upper scale bar in this figure also provides the effective target thicknesses Leff (including the pre-plasma thickness) in Lop units. In the theoretical description of the RPA mechanism, Lop is the optimal target thickness ensuring the highest RPA acceleration efficiency and is described by the formula [2]:

where is a dimensionless amplitude of the laser pulse, is critical plasma density, ne is electron density, is the laser wavelength, is amplitude of the electric field of the laser pulse, is angular frequency of the laser pulse, is electro charge, is electron mass and is speed of light. For a uranium target and for laser intensity equal of 1023 W/cm2 and , . As can be seen from Figure 11, the contribution of the energy carried by Ne-like ions to the entire beam energy is highest for the thinnest targets used () and, depending on the assumed ion energy range, ranges from 96% (for Ei > 0) to 98% (for Ei > 10 GeV). For thicker targets, the contribution of Ne-like ion energy to the overall beam energy is noticeably lower, reaching values of ~80–90%. Changing the target thickness therefore enables quite effective control of the ion beam’s mono-charge degree without changing the laser parameters.

Figure 11.

The quantitative contribution (in percentage) of the energy carried by Ne-like ions to the energy of the entire uranium beam as a function of target thickness for three ion energy ranges. dL = 6 µm, t = 240 fs.

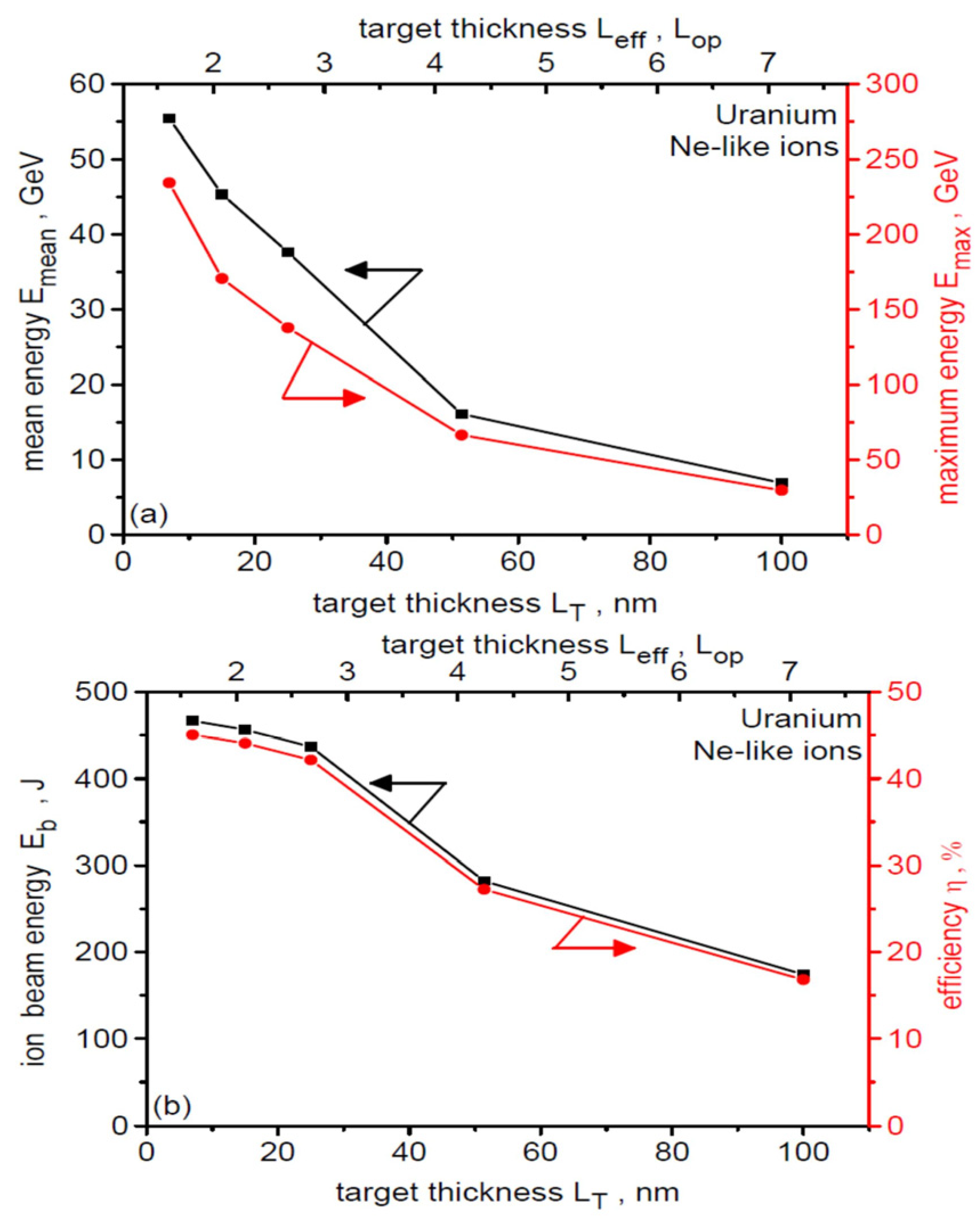

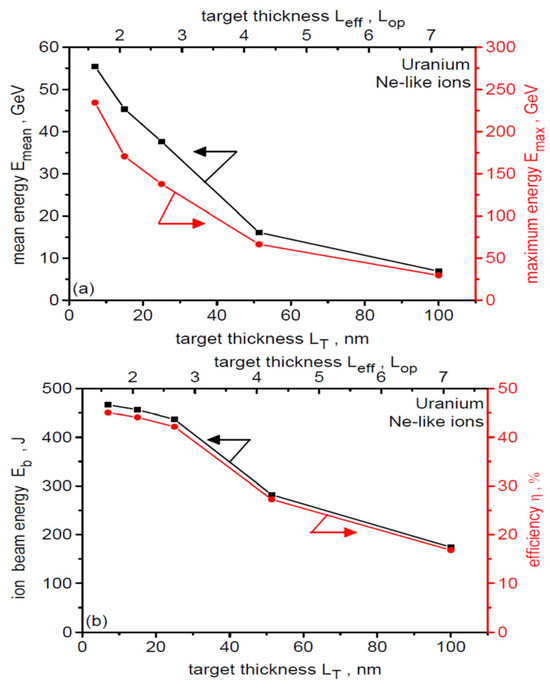

The effect of target thickness on the mean and maximum energy of Ne-like ions (a) and on the total energy of these ions and the energy efficiency of their acceleration (b) is illustrated in Figure 12. Both Emean and Emax of Ne-like ions increase quite rapidly with decreasing target thickness (a change in Leff by a factor of 4.4 leads to a change in ion energy by an order of magnitude), and for the thinnest target with Leff = 1.6 Lop, they reach 55 GeV and 234 GeV, respectively. Decreasing target thickness also results in an increase in the energetic efficiency of Ne-like ion acceleration, and for the thinnest target, this efficiency reaches a very high value of close to 45%. Variation of target thickness can therefore be a simple and effective way to control the mean and maximum energy of uranium ions.

Figure 12.

The effect of target thickness on the mean and maximum energy of Ne-like ions (a) and on the total energy of these ions and the laser-to-Ne-like ions energy conversion efficiency (b). The arrows in the figure assign a given graph to the appropriate y-axis. dL = 6 µm, t = 240 fs.

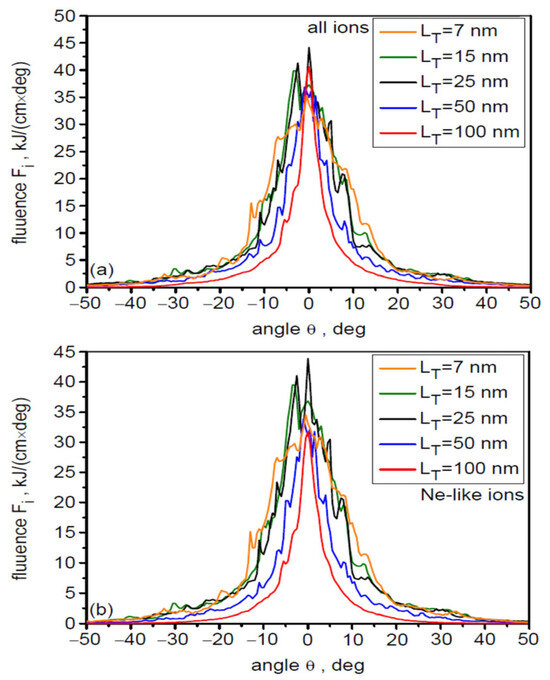

The target thickness has a significant effect on the angular and spatial (transverse) distributions of ion energy fluence and the temporal shape of the ion pulse, as well as the peak values of fluence and intensity of the ion beam. This is illustrated in Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15. Figure 13 shows the angular distributions of fluence for all accelerated uranium ions (a) and Ne-like ions (b) for the five considered target thicknesses LT. These distributions for all ions and Ne-like ions are practically identical, which is the result of the clear dominance of Ne-like ions in the ion beam. An increase in LT leads to a decrease in the beam angular divergence, the main reason for which in the considered cases is the decreasing contribution of the CEA mechanism in the acceleration process. As LT increases, the spatial distribution of the ion beam fluence also narrows, as illustrated in Figure 14 for two distances from the target (x = 30 µm and 100 µm). Increasing the distance from the target leads to a broadening of the distribution and a significant reduction in the peak fluence.

Figure 13.

The angular distributions of ion beam energy fluence for all accelerated uranium ions (a) and Ne-like ions (b) for five target thicknesses LT. dL = 6 µm, t = 240 fs.

Figure 14.

The spatial distributions of ion beam energy fluence for all accelerated uranium ions at distances x = 30 µm (a) and 100 µm (b) from the targets with various thicknesses. dL= 6 µm.

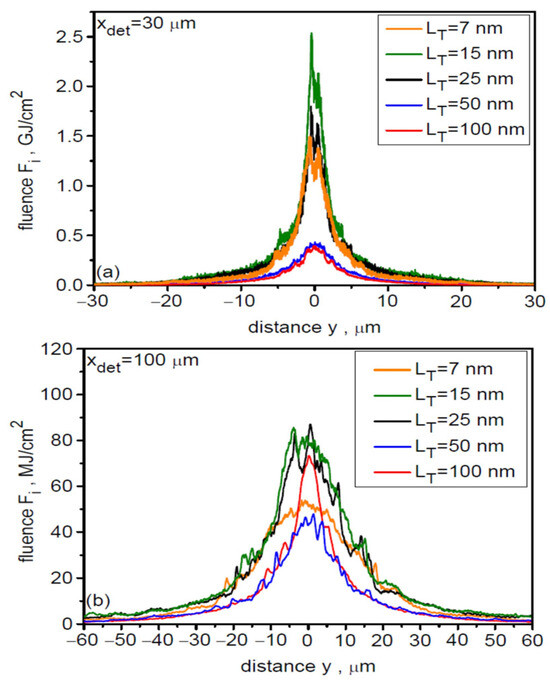

Figure 15.

The temporal distributions of ion beam intensity (averaged over a 20-µm region) for all accelerated uranium ions at distances x = 30 µm (a) and 100 µm (b) from the targets with various thicknesses. dL = 6 µm.

In the case of temporal distributions of the ion beam intensity, increasing the target thickness leads to a broadening of the temporal distribution (ion pulse duration) and a reduction in the peak intensity (Figure 15). This is due to the decreasing ion energy with increasing dL. As the distance from the target x increases, the peak ion pulse intensity decreases (due to both the angular divergence of the beam and ion velocity dispersion) and its duration increases (due to ion velocity dispersion). For the thinnest targets with LT ≤ 15 nm (Leff ≤ 35 nm), the ion pulse peak intensity decreases from ~30 × 1020 W/cm2 at x = 30 μm to ~3 × 1020 W/cm2 at x = 100 µm, while its duration increases from ~50 fs to ~200 fs (FWHM). Considering that the ion pulse energy is >400 J (Figure 12b), the ion pulse power is ~8 PW at x = 30 µm and ~2 PW at x = 100 µm, thus being in the multi-PW range in both cases.

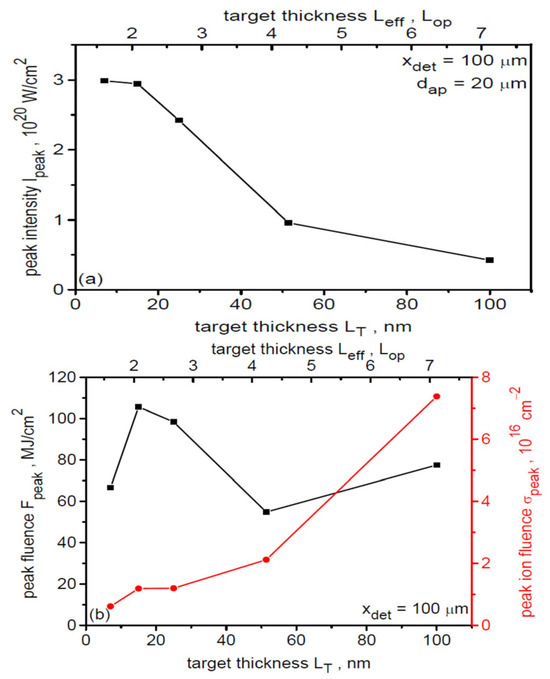

The dependence of the peak values of the intensity (a) as well as energy and ion fluences (b) of the ion beam on the target thickness is presented for 100 µm from the target in Figure 16. A 3D correction was used to determine these values (also for the graphs in Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15). The beam intensity decreases from ~3 × 1020 W/cm2 for LT = 7 and 15 nm to ~0.5 × 1020 W/cm2 for LT = 100 µm. This course of the dependence is primarily determined by the relatively rapid reduction of ion energy with increasing dL (Figure 12), which has a greater impact on the change in beam intensity than possible increase in ion density ni accompanying increasing LT (Ii = niEi3/2). In the case of peak energy fluence of the beam, its dependence on dL is nonmonotonic with a clear maximum at LT = 15 nm (Leff ~ 2 Lop). This is because energy fluence linearly depends on both the areal ion density (ion fluence) σi and the ion energy Ei, i.e., Fi = σiEi, and for sufficiently small target thicknesses, the increase in Ei accompanying the reduction in dL cannot compensate for the reduction in ion areal density. On the other hand, the peak ion fluence σpeak increases with increasing LT because a higher number of ions is accelerated in the case of thicker targets. It should be added that also in the case of Ipeak (dL) dependence on target thickness, a decrease in intensity can be expected for very thin targets with Leff < Lop. For such targets, the sharp decrease in σi due to the relativistic transparency of the plasma could not be compensated by the increase in ion energy and thus the peak beam intensity would decrease. With the fixed effective pre-plasma thickness assumed to be Leff ~ 20 nm > Lop ~ 15 nm, it is not possible to demonstrate this case.

Figure 16.

Dependence of the peak intensity (a) and peak energy fluence and peak ion fluence (b) of the ion beam on the target thickness. dL = 6 µm, x = 100 µm.

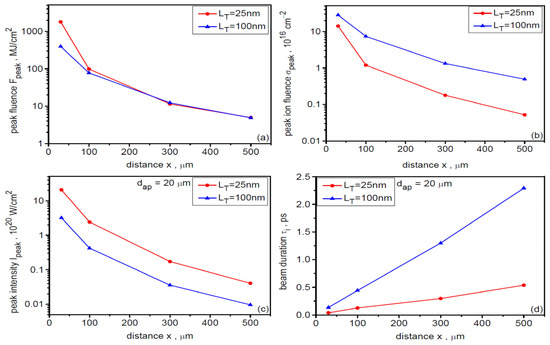

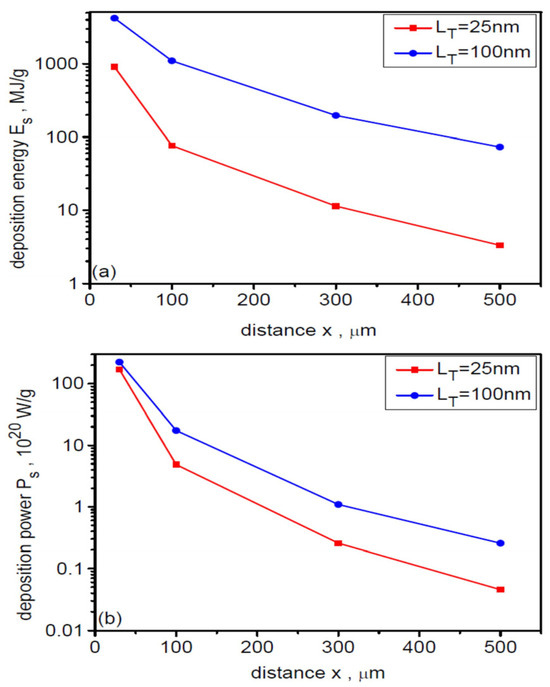

As demonstrated in Figure 14 and Figure 15, the peak intensity and peak energy fluence of the ion beam as well as the ion pulse duration depend on the distance of the beam detection point, x, from the target. The dependence of these values as well as peak ion fluence on x over a wide range from x = 30 µm to x = 500 µm for three target thicknesses LT is shown in Figure 17. With increasing x, the Ipeak, Fpeak and σpeak values decrease quite rapidly, while the ion pulse length increases. For thinner targets, the intensity decreases from very large values exceeding 1021 W/cm2 at x = 30 µm to ~5 × 1018 W/cm2 at x = 500 µm. For the thickest target, the peak intensity also changes by nearly three orders of magnitude, but the intensities are several times lower. As mentioned earlier, this strong intensity decrease with increasing x is the result of the combined effect of beam angular divergence and ion velocity dispersion on beam propagation. Due to beam angular divergence, the peak beam fluence changes from ~2 GJ/cm2 for x = 30 µm to ~5–7 MJ/cm2 for x = 500 µm. The differences in fluence values for targets of different thicknesses are not very large, especially for x > 100 µm. However, the changes in ion pulse duration with increasing x are very large for different dL: for thinner targets, these changes range from several tens of fs to several hundred fs, while for the thickest target, the ion pulse duration varies from ~100 fs for x = 30 µm to ~2.3 ps for x = 500 µm. It is worth adding that the considered changes in Ipeak, Fpeak, σpeak and τi with increasing x occur with practically unchanged ion energy, because at x > 50 μm the fields accelerating the ions are so small that very heavy uranium ions are insensitive to these fields and move ballistically.

Figure 17.

Dependence of the peak values of energy fluence (a), ion fluence (b), intensity (c), and duration (d) of the ion beam on the distance from the uranium target with a thickness of 25 µm and 100 µm. dL = 6 µm.

In summary, reducing the uranium target thickness LT at fixed laser pulse parameters leads to an increase in (a) mean and maximum ion energy, (b) energetic acceleration efficiency, (c) beam intensity, and (d) the percentage of Ne-like ions in the beam (the beam becomes more mono-charged), as well as to shortening the ion pulse duration. Simultaneously, reducing the target thickness results in an increase in the beam’s angular divergence and a reduction in ion fluence (the number of ions per unit area). Changes in these beam parameters with changes in target thickness are relatively rapid, which allows for control of these parameters by varying the target thickness.

The energy fluence, ion fluence, and beam intensity decrease rapidly (faster than linearly), while the ion pulse duration increases with increasing distance between the beam detection point and the target (these changes occur while the ion energy remains constant). Changing this distance can therefore be a simple and effective way to control these parameters, e.g., in ion beam-target interaction experiments.

5. Synchrotron Radiation Accompanying the Generation of Ultra-Intense Ion Beams

At very high laser intensities ~>1023 W/cm2, ion acceleration is accompanied by the emission of short-wavelength synchrotron radiation (SR) (typically gamma radiation with photon energy > 1 MeV), the sources of which are relativistic electrons produced in laser-plasma interactions [71,72,73,74]. The efficiency of laser energy conversion into the radiation energy depends not only on the laser intensity (it increases with IL) but also on various laser and target parameters and can range from ~1% to several dozen percent [71,72,73,74,76,78]. Because SR emission consumes some of the laser energy that could otherwise be used to accelerate ions, it can lead to reduced acceleration efficiency and lower ion beam parameters.

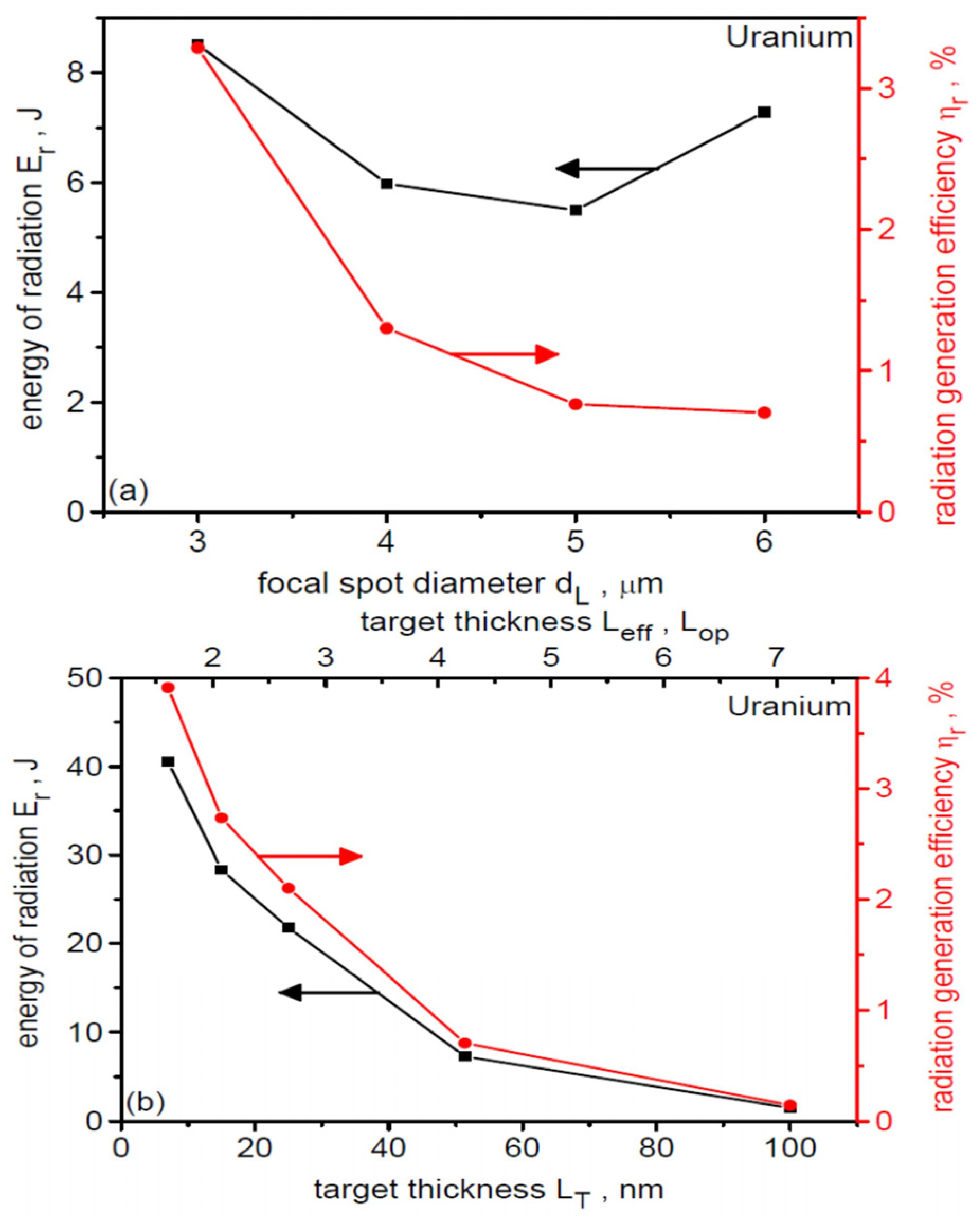

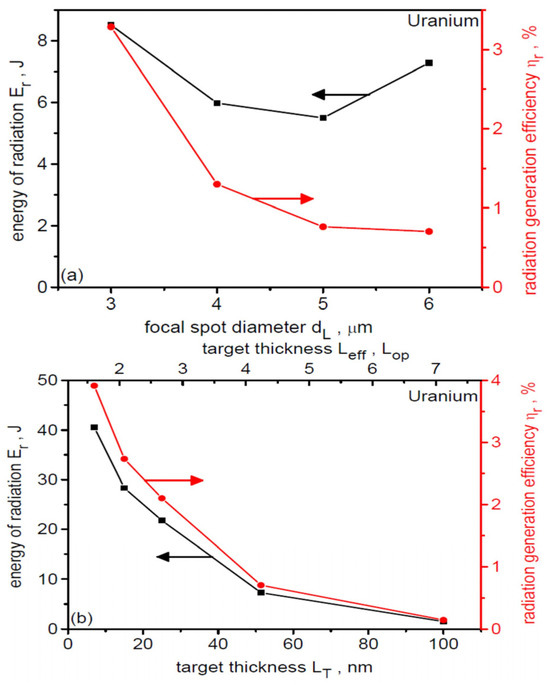

Figure 18 shows the synchrotron radiation energy, Er, and the laser-to-radiation energy conversion efficiency, ηr, as a function of the laser focal spot size (a) and uranium target thickness (b) at IL = 1023 W/cm2 with other laser and target parameters fixed (see Section 3). As dL increases, the conversion efficiency decreases, suggesting that despite the increase in laser energy (proportional to dL2) and the number of accelerated electrons, the temperature of the relativistic electrons decreases. As a result, the energy of the generated radiation changes only slightly (by ~30%). However, changing the target thickness leads to much faster changes in the SR energy. Reducing LT leads to an increase in the temperature of the relativistic electrons (laser energy is used to accelerate fewer electrons), and as a result, the energy of the emitted radiation and the conversion efficiency increase rapidly. For the thinnest target, the SR energy reaches 40 J, and the conversion efficiency ηr is 4%. However, when we compare the ηr values with the efficiency of converting laser energy to accelerated ion energy, which is over 40% (Figure 12b), we see that no more than 1/10 of the laser energy that could be used to accelerate ions is wasted in SR emission. Therefore, in the cases considered in this work, the influence of radiation losses caused by SR emission on the parameters of the uranium ion beam is small.

Figure 18.

The synchrotron radiation energy and the laser-to-radiation energy conversion efficiency as a function of the laser focal spot size (a) and uranium target thickness (b). IL = 1023 W/cm2. For (a) LT = 50 nm, for (b) dL = 6 µm. The arrows in the figure assign a given graph to the appropriate y-axis.

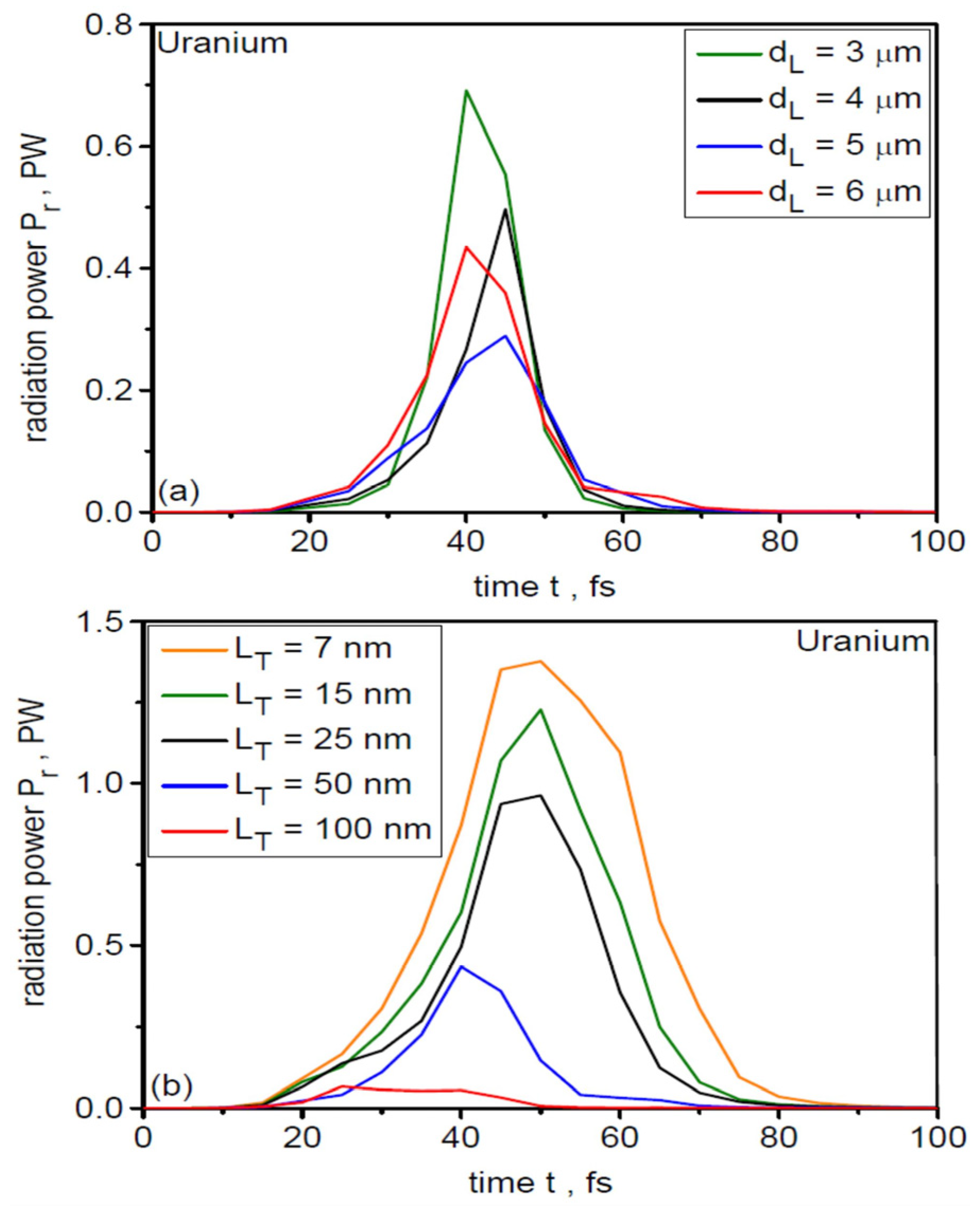

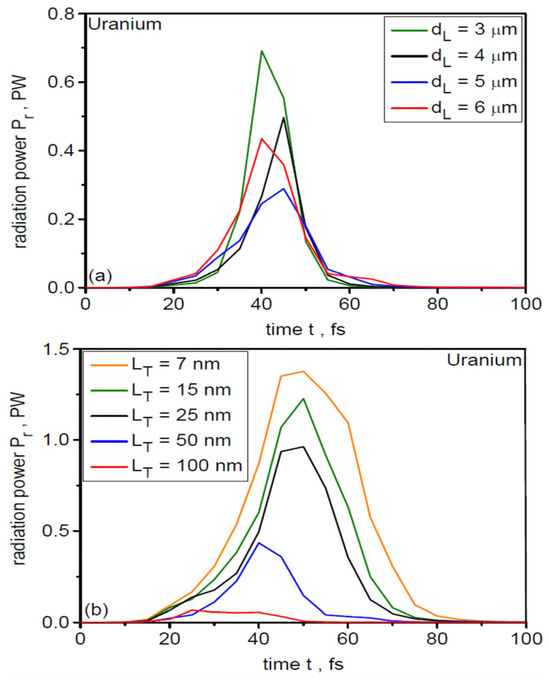

As demonstrated, for example, in [76], synchrotron radiation is emitted primarily from the region of direct interaction of the laser field with the laser-produced plasma electrons. Therefore, the intensity of SR emission is highest near the laser beam axis, where the beam intensity is highest, and the emission duration is comparable to the laser pulse duration. The energy of SR photons increases with the energy (Ee) of the emitting electrons, and at Ee >> 1 MeV, the electrons emit gamma radiation [72,73]. In the cases considered in this work, the energy of relativistic electrons reaches several tens of MeV, and synchrotron radiation is therefore gamma radiation. Figure 19 shows gamma radiation pulses accompanying uranium ion acceleration for various sizes of the laser focal spot at LT = 50 µm (a) and various target thicknesses at dL = 6 µm (b). The duration of the gamma pulses ranges from ~15 fs to ~30 fs, and their power exceeds 1 PW (for LT ≤ 15 nm). It is worth adding that, unlike ion pulses, the duration of gamma pulses in vacuum does not depend on the distance from the SR source, and even at large distances from the target, the duration and power of the gamma pulse will be the same as near the target. Of course, due to the angular divergence of the radiation, the intensity of gamma radiation will decrease with increasing distance from the target.

Figure 19.

Temporal shapes of gamma-ray pulses for different laser focal spot sizes (a) and different uranium target thicknesses (b). IL = 1023 W/cm2. For (a) LT = 50 nm, for (b) dL = 6 µm.

In conclusion, under the considered laser-target interaction conditions, the efficiency of converting laser energy into synchrotron radiation energy does not exceed a few percent and is an order of magnitude lower than the efficiency of converting laser energy into the energy of accelerated ions. The effect of SR emission on ion beam parameters is therefore small. Despite this, the emitted ultra-short (~30 fs) gamma radiation pulses have high power (~PW) and can be used in various applications, such as nuclear physics or materials science.

6. Discussion

In this section, we will discuss some limitations and inaccuracies of the computer model used in the simulations, as well as some issues related to plasma instabilities occurring during ion acceleration, the practical achievability of the assumed target and laser parameters, and the possibility of performing experiments to verify the results of the simulations.

The studies of ultra-intense beam generation conducted in this paper are based on the results of numerical simulations using the advanced, two-dimensional particle-in-cell computer code PICD0M. Although this code accounts for most of the physical phenomena relevant to the problem under study, the simulation results are subject to inaccuracies, primarily due to the limited computing power available to the authors. These inaccuracies arise from both technical and physical reasons. Technical inaccuracies result primarily from limitations on the time and space steps used in the simulations, the simulation time, and the size of the simulation box. The PICDOM code has been optimized so that, despite these limitations, the simulations can reveal the physical phenomena crucial to the problem being studied while keeping quantitative errors as small as possible. Another reason for simulation inaccuracy is the use of a 2D code instead of a 3D code, which potentially better reflects reality. In the case of laser-driven ion acceleration, omitting one of the spatial dimensions can result not only in quantitative but also qualitative inaccuracies, including the omission of some phenomena whose full significance is not reflected in the 2D code. Both quantitative and qualitative differences between 2D and 3D simulation results depend on the laser and target parameters, and on the type of acceleration mechanism dominant in the ion beam generation.

Acceleration mechanisms such as RPA, TNSA, CEA, or RITA, crucial for producing ultra-intense ion beams, can be modelled quite well with 2D simulations, as confirmed by many papers investigating ion acceleration using these mechanisms. When determining the basic parameters of the generated ion beam, such as the energy spectrum, ionization spectrum, mean angular divergence of the beam, or the intensity, fluence, and energy of the beam, we are primarily (though not exclusively) dealing with quantitative differences between the results of 2D and 3D simulations. Particularly large differences are observed in the energies of ions accelerated by TNSA. In this case, the energies of ions determined using 2D PIC can be more than twice as high as those determined using 3D codes [80,81,82]. As a result, the intensity, fluence, and energy of the ion beam are also overestimated. This is primarily because the decrease in electron density in the sheet at the target rear surface caused by the lateral expansion of the plasma is slower in two dimensions than in three. Also, in ion acceleration using the CEA mechanism, the acceleration efficiency and ion energy calculated in 2D can be higher than in 3D, because the Coulomb energy (repulsion energy) stored in the ions is dispersed in a plane rather than in three-dimensional space. This applies particularly to ion acceleration in directions close to the laser beam axis, i.e., in the forward direction, supporting the RPA acceleration, and in the backward direction, counteracting the RPA acceleration.

In the case of ion acceleration using RPA, and especially RPA-LS, the situation is different from that for TNSA and CEA. Transverse expansion of the plasma (ions) causes successive decrease in the areal mass density, σ, of the ion (plasma) bunch accelerated by laser light pressure and the decrease in σ is faster in 3D than in 2D. The ion bunch becomes lighter and therefore its velocity increases faster in 3D. As a result, at the end of the RPA acceleration stage, the bunch velocity and the energy of the ions accumulated in the bunch are higher in 3D simulations. On the other hand, if the laser pulse is long enough (or the target is thin enough), a faster decrease in plasma density can lead to faster penetration (transparency) of the bunch by the laser pulse and a shortening of the RPA acceleration stage. This can result in a lower mean ion energy and, therefore, lower intensity and energy fluence of the ion beam in the 3D simulation compared to 2D. In such a case, the increase in ion velocity and energy due to the lower areal density of the ion bunch can be compensated by the shortening period of effective ion acceleration. The picture outlined above is confirmed by works [33,83] which compared the results of 2D and 3D simulations for both RPA-LS and RPA-HB. In these works, the energies of ions driven by RPA are usually higher in 3D simulations than in 2D. The observed differences do not exceed several dozen percent and are much smaller than the typical differences in ion energies observed in the case of TNSA acceleration [80,81,82].

In the uranium ion acceleration studied in this paper, the dominant acceleration mechanism is RPA-LS, and relativistic transparency of the accelerated target is not observed. Considering the argument presented above, the mean ion energies, as well as the intensity, fluence, and energy of the ion beam, may be slightly underestimated compared to the results of possible 3D PIC simulations. In turn, the lower ion acceleration efficiency via the CEA mechanism (which is the main source of increased beam angular divergence) may result in a smaller beam divergence in 3D. On the other hand, the maximum ion energy, which is largely determined by the TNSA mechanism, may be overestimated in our simulations. However, the value of this energy is of secondary importance in the generation of ultra-intense ion beams.

Laser-driven ion acceleration, including that driven by the RPA mechanism, is usually accompanied by the development of plasma instabilities, Rayleigh-Taylor-like (R-T) instabilities [84,85,86,87] and Weibel-like (WB) instabilities [88,89,90]. WB instabilities are favored by targets with rather low densities, comparable to the critical plasma density [89,90] (although they also occur at higher densities), where ion acceleration is dominated by the RPA-HB mechanism (if the laser intensities are sufficiently high). In such targets, WB instabilities have enough space and time to develop and create small-scale inhomogeneities (filamentations) in the plasma, which deteriorate the quality of the generated ion beam. In the case of solid-state targets, WB instabilities are observed primarily in the pre-plasma generated on the target surface by the laser pre-pulse. RT instabilities accompany both RPA-HB acceleration (thick targets) and RPA-LS acceleration (thin targets). They are particularly dangerous for very thin targets, where RT instabilities can lead to complete destruction of the target and the generated ion beam even before the acceleration process is complete. In the case of a high-quality solid target (without surface irregularities), the main source of RT instabilities is inhomogeneity in the lateral intensity distribution of the laser beam. Even for high-quality beams, the formation of these inhomogeneities is difficult to avoid, as they result from diffraction of laser light at the target surface and interference between the incident beam and the beam reflected from the target (from the critical plasma surface). As a result, the laser light intensity distribution on the target surface has a non-uniform periodic structure with a non-uniformity scale of the order of λL. In the initial phase of laser-target interaction, the laser beam produces a periodic density disturbance on the target surface (near the critical plasma surface) with a non-uniformity scale comparable to λL. During ion acceleration, the amplitude of these non-uniformities increases exponentially due to RT instabilities. The growth rate (g) of these instabilities depends on the acceleration (A) of the surface driven by the light pressure and increases with increasing A [56]. If the value of g is sufficiently high and/or the acceleration duration is sufficiently long, the RT instabilities can destroy the accelerated plasma object.

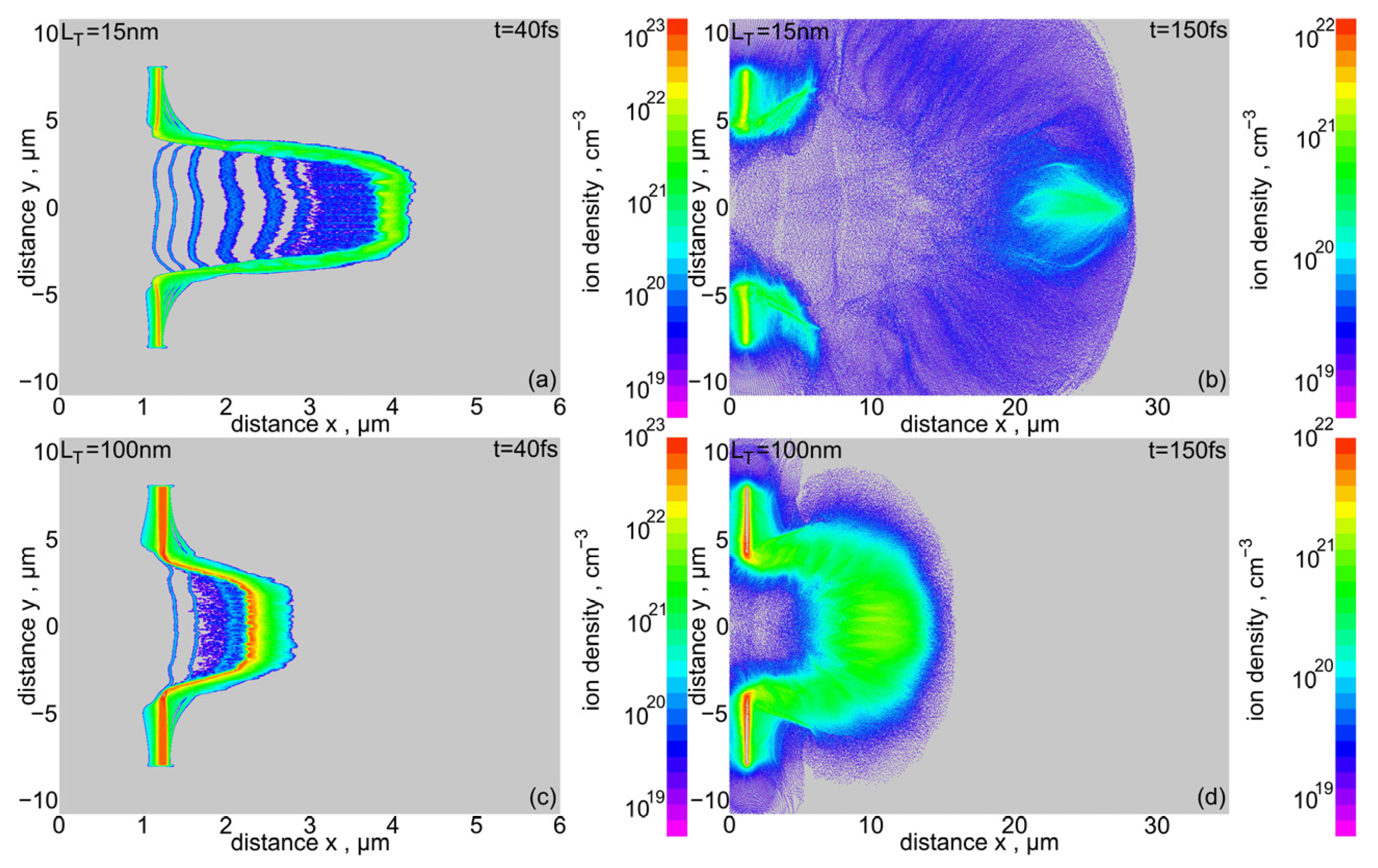

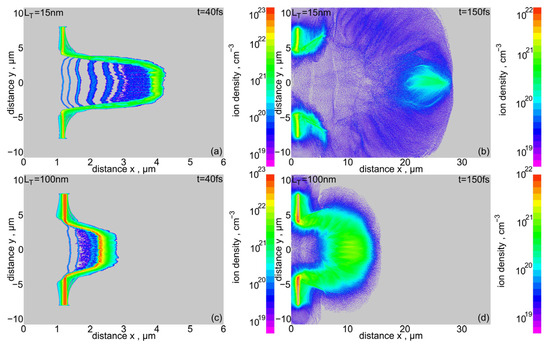

Figure 20 shows the density distributions of uranium ions in the final stage of acceleration by RPA-LS (t = 40 fs) and in the final stage of post-RPA acceleration (t = 150 fs) driven by CEA and TNSA. Figure 20a,b illustrates the density distributions for a target with a thickness of LT = 15 nm (Leff ~ 35 nm), while Figure 20c,d for a target with LT = 100 nm (Leff ~ 120 nm). A more detailed analysis of these distributions showed that, at t = 40 fs in the pre-plasma region, there are many longitudinal filamentations with a width not exceeding λL/10. This suggests that WB-type instabilities occur and dominate in this region. Such filamentations are not observed in the final stage of post-RPA acceleration (t = 150 fs). In the dense plasma region, both in the final RPA stage (Figure 20a) and in the post-RPA stage (Figure 20d), density modulations are observed with a mean distance between density peaks of ~0.5 μm. This inhomogeneity scale is quite close to λL/2 = 0.4 μm, i.e., the scale of the transverse inhomogeneity of the standing wave of laser light irradiating the target. This suggests that the sources of these inhomogeneities are RT instabilities, which dominate here in the dense region of accelerated plasma. Despite the observed instabilities, even with a very thin target (LT = 15 nm), the uranium ion beam was not destroyed, and a fairly compact ion bunch entered the ballistic propagation stage (see also Figure 14) with a density of up to ~5 × 1020 cm−3, areal ion density ~(3–4) × 1017 cm−2, energy fluence > 1 GJ/cm2 (Figure 14a), and intensity > 1021 W/cm2 (Figure 15a). For a 100 nm target, the density and areal ion density are even higher, but—due to the lower ion energy—the energy fluence and beam intensity are slightly lower (Figure 14 and Figure 15). It is worth noting that the relatively high resistance of the uranium ion beam to the destructive effects of RT instability, demonstrated above, is primarily due to the very high mass of the uranium ions. First, due to the high ion mass, the acceleration factor A, which largely determines the growth rate of the instability g, is significantly lower than for light ions accelerated by a laser beam of the same intensity. Second, due to their high mass, uranium ions are less sensitive than light ions to the magnetic and electric fields accompanying the development of instabilities (both RT and WB) and the destructive influence of these fields on the ion beam.

Figure 20.

2D spatial distributions of uranium ion density in two acceleration stages for a uranium target with a thickness LT equal to 15 μm (a,b) and 100 μm (c,d). IL = 1023 W/cm2, dL = 6 μm.

In 3D simulations, the influence of plasma instabilities on the generated uranium beam can potentially be greater than in 2D. The three-dimensional structure of the field, especially the magnetic field, can intensify the development of instabilities and thus increase their destructive effect on beam quality. However, for the reasons indicated above, the impact of including the third dimension in simulations on the degree of beam degradation by these instabilities should be much smaller for the uranium beam than for a light ion beam. Therefore, it can be expected that even in 3D simulations, the uranium beam will not be destroyed for the laser and target parameters considered in this paper. To verify this assumption and to quantitatively assess the impact of the additional dimension in simulations on ion beam parameters, we would need to compare the results of our simulations with the results of the corresponding 3D simulations. However, this is beyond the current capabilities of the authors of this paper.

A crucial issue for experimental verification of our numerical results and the use of super-heavy ion beams in possible applications is the achievability of the laser and target parameters assumed in the simulations. In particular, this concerns the level of laser pulse intensity contrast required under the laser-target interaction conditions considered in this work.

The leading edge of every real laser pulse has a low-intensity part—the pulse “background”—that irradiates the target before the main pulse, carrying almost all the pulse’s energy, reaches the target. If the intensity level of this “background” is sufficiently high, it generates pre-plasma on the target surface. The shape and thickness of the pre-plasma depend not only on the intensity but also on the background structure. This structure is complex and usually includes: a long-term part (from a few to several dozen ns) determined mainly by ASE, an intermediate (sub-ns) part with possible ps or fs pre-pulses, and a short-term (ps, sub-ps) part in the immediate vicinity of the main high-intensity part of the laser pulse. The detailed structure of the pulse “background” in each laser system is different and depends on the detailed technical solutions used in the system. The concept of laser contrast, understood as the ratio of the average intensity of the “background” to the peak intensity of the pulse, is therefore not unambiguous, because the average intensity of each of the three mentioned parts of the “background” is different (the differences can reach several orders of magnitude). In this way, we can talk about three types of laser contrast: long-term contrast, medium-term contrast and short-term contrast. As the numerical values of these contrasts may differ by orders of magnitude, a credible answer to the question of what laser contrast is necessary for the implementation of the laser-target interaction conditions assumed in our simulations does not seem possible without knowing the detailed structure of the laser pulse “background”. This makes it even more difficult to reliably determine (e.g., using hydrodynamic simulations) the characteristics of pre-plasma without knowledge of this structure.

For the reasons mentioned above, to mimic the interaction between the laser pulse “background” and the target in theoretical and numerical studies, the thickness and shape of the pre-plasma density distribution are usually assumed a priori. These pre-plasma parameters have a significant impact on the laser-driven ion acceleration, and on the type and efficiency of the mechanism that dominates acceleration. When the peak intensity of the laser pulse is very high and RPA is the dominant acceleration mechanism, the pre-plasma thickness should be as small as possible, and the pre-plasma density gradient should be high [1,2,14]. If this requirement is not met, the RPA acceleration efficiency may be low, and therefore the parameters of the generated ion beam may be unsatisfactory. In particular, an increase in the pre-plasma thickness and/or a decrease in the pre-plasma density gradient may lead to: (a) a decrease in the ponderomotive force driving ions and thus a decrease in the ion energy and the intensity, fluence and energy of the ion beam, (b) an increase in the angular divergence of the beam, (c) a broadening of the energy spectrum, (d) a deterioration in the quality of the spatial distribution of ion density and energy (e.g., due to the intensification of WB instability or filamentation of the laser beam in the pre-plasma).

Based on our earlier studies (e.g., [20,79]), in this work, we assumed uranium pre-plasma parameters conducive to achieving high RPA acceleration efficiency, namely: an exponential pre-plasma density profile, a total thickness of 184 nm, and an effective thickness (at the level of 1/e of the maximum density) of ~20 nm. These uranium pre-plasma parameters correspond to a CH pre-plasma with a total thickness of ~0.8 μm (plasma expansion velocity is inversely proportional to the square root of the ion mass). The effective target thicknesses (Leff) assumed in the simulations range from 27 nm to 120 nm. They correspond to CH target thicknesses with an areal mass density like that of the uranium target, ranging from ~0.5 μm to ~2 μm. The parameters of the pre-plasma and the thickness of the uranium targets are therefore not particularly sophisticated. Flat targets made of heavy metals (Au, Pb, U, …) with such thicknesses are easily achievable with current target fabrication technologies [67,68] and have been used in experiments for many years [4,7,44].