Abstract

PN-junction-based modulators are widely used in silicon photonic transceivers for different applications. Different junction shapes have been proposed in the literature. This work studies the optimization of the PN junction by tailoring the doping profile to achieve a high-efficiency modulator with sufficient bandwidth. For this purpose, a new N-shaped junction is proposed, which achieves superior performance compared to other junction shapes. The proposed junction has an efficiency that is 60% better than that of the lateral PN junction for the same doping condition, while maintaining a high bandwidth similar to other junctions such as the L-shaped and S-shaped designs. A junction design with an estimated RC bandwidth between 70 GHz and 94 GHz is also proposed. The impact of using the proposed junction in micro-ring modulators (MRMs) is also studied. N-shaped junctions in MRM demonstrated a 112% increase in electro-optic bandwidth over the vertical PN junction, with 60% and 140% improvements in extinction ratio (ER) and optical modulation amplitude (OMA), respectively, compared to the lateral PN junction.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, silicon photonics (SiPh) has received considerable recognition due to its low cost, high performance, and CMOS fabrication compatibility [1]. The demand for ultra-high-speed networks has grown significantly, leading to silicon photonics attracting substantial attention, particularly in the fabrication of optical transceivers for both long-haul and short-reach optical communication links.

For high-speed networks, fast optical phase shifters are essential components in photonic integrated circuits (PICs). The landscape of optical modulators is vast, with modulation schemes depending on phase or amplitude modulation. Existing literature reports the implementation of optical modulators on multiple platforms [2]: silicon [3], monolithic barium titanate (BTO) on silicon [4], thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN) on silicon [5], etc., each of which offers different material properties, leading to the exploration of a plethora of operating principles such as the plasma dispersion effect [6], the Pockels effect [7], the Franz–Keldysh (FK) effect [8], and the quantum-confined Stark (QCS) effect [9].

With the dense, cost-effective, and power-efficient integration of photonics on SiPh platforms [10,11,12], the deployment of the plasma dispersion effect in high-speed modulators has become the most widely adopted. The plasma dispersion effect depends essentially on the creation of a refractive index change in a silicon waveguide as a result of the movement of the carriers in the formed PN junction through injection, accumulation, or depletion of charges [12]. The junction performance as a modulator or phase shifter is usually evaluated by the applied voltage required to achieve a phase shift of π () through a waveguide of length . The reduction in the value of the product is highly desired to achieve a high-speed modulator with low voltage swing and a small footprint, as an increase in the modulator length directly reduces its bandwidth. This product for injection and accumulation junctions can be as low as 0.16 V.cm [11] and even 0.058 V.cm [13], while depletion junctions can reach data rates as high as 100 Gbps (OOK) [14]. The work presented in this paper focuses on plasma-dispersion-based modulators using the depletion principle due to the high speeds they can achieve as a result of their limited capacitance compared to injection- and accumulation-based junctions.

By increasing the overlap of the formed depletion region with the optical mode, stronger spatial variation can be achieved. This means that the change in the free carrier density results in a stronger change in the material refractive index, which translates into an enhancement in modulation efficiency.

A lot of research has been conducted in this direction by altering the junction doping profile, some of which includes U-shaped junctions [15], zigzag junctions [16], and interleaved junctions [17]. All of the previous work shows a clear trade-off between enhancing modulation efficiency and maintaining optical losses and capacitance.

This paper describes how to obtain the required junction and how the resulting junctions perform so they can accordingly serve different applications based on the previously mentioned trade-offs. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, the theory behind optical modulation is thoroughly explained, and the method of optimization is described in sufficient detail. The simulation results are presented in Section 3, along with the subsequent discussion in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 summarizes all the findings of this study and their relevance.

2. Theory and Methods

Within the plasma dispersion effect, changes in carrier concentration under an applied electric field lead to variations in silicon absorption. Material absorption is generally described by the imaginary part of the refractive index, and according to the Kramers–Kronig relation, the variation in the imaginary part of the complex refractive index is accompanied by a corresponding change in its real part. Soref and Bennet [18] calculated the changes in real (Δn) and imaginary (Δα) parts of the refractive index due to changes in carrier densities in silicon at a wavelength of 1.55 μm to be [18]:

where and are the changes in the electron and hole concentrations, respectively. The main design specifications for optical modulators are the modulation bandwidth (speed) and the modulation efficiency. Lateral PN (LPN) junctions [19], illustrated in Figure 1a, have played a significant role in optical modulation over the past decade due to their relatively simple fabrication (photolithography and doping), and high modulation speed resulting from their reduced junction capacitance. However, lateral junctions have limited depletion regions, and hence limited overlap with the optical mode in the structure, which results in low modulation efficiency. Another well-known junction is the vertical PN (VPN) junction [20], shown in Figure 1b, which exhibits high modulation efficiency with limited bandwidth due to its high capacitance.

Figure 1.

Waveguide cross-section view of (a) LPN junction and (b) VPN junction.

The figure of merit (FOM) typically used to characterize a modulator PN junction is , where expresses the modulation efficiency, R is the junction resistance, and C is its capacitance. The RC value usually has a dominant contribution to minimizing the FOM, often resulting in an LPN-like junction. To mitigate this shortcoming, we penalize over RC, which instead provides a junction profile with a more appropriate efficiency–bandwidth trade-off.

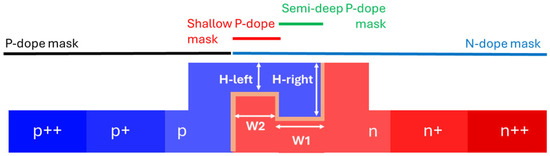

In this work, we consider a silicon rib waveguide with dimensions of 220 nm in height, 500 nm in width, and a 95 nm-high slab, with degenerately doped regions (N++ and P++) of concentration 1020 cm−3, heavily doped regions (N+ and P+) of concentration 1019 cm−3, and lightly doped regions (N and P) of peak concentrations 5 × 1018 cm−3 [21]. The junction is implemented using four doping masks (P-dope mask, shallow P-dope mask, semi-deep P-dope mask, and N-dope mask). Their design parameters are W1, W2, H-left, and H-right, and they are mapped as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Doping masks used and junction parameters.

Using Ansys Lumerical CHARGE and FDE simulations, the PN-junction charge distribution is calculated, and the mode profile is examined. The junction is assumed to have a Pearson-4 distribution to approximate the real post-fabrication junction as closely as possible [22]. Comprehensive steady-state CHARGE simulations have been conducted to optimize the profile geometry, where the dimensions of the doping masks are swept to include all possible widths, offset from the center, and heights at a constant peak doping concentration. For each junction profile, the variation in the effective refractive index, the junction losses, resistance, and capacitance are extracted. The optimized junction parameters are then plugged into Lumerical INTERCONNECT in a microring modulator (MRM) to perform a clear comparison of the optical modulation amplitude (OMA), extinction ratio (ER), ratio of level mismatch (RLM), and electro-optic (EO) bandwidth, demonstrating the extent of the improvement and the different trade-offs compared to the conventional junctions. While we have chosen to show the performance based on an MRM, the junction can be used in different modulator designs such as a Mach–Zehnder modulator (MZM) or a ring-assisted Mach–Zehnder modulator (RAMZI).

3. Simulation Results

The results can be divided into three main areas of optimization: (1) modulation efficiency, (2) bandwidth, and (3) FOM with penalized . It is prudent to consider imposing constraints on physical design parameters, specified by the doping mask overlay and dimensions included in the aforementioned sweep, for the resulting junction to be compliant with the fabrication process limitations. Similar considerations apply to resulting optical parameters, where the previously discussed trade-offs should be maintained within acceptable ranges.

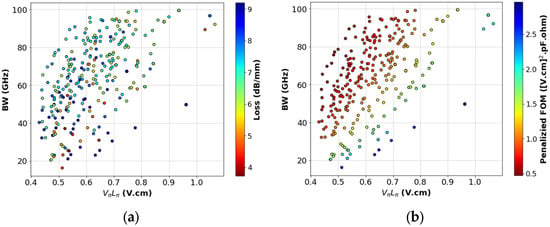

For each appropriate FOM value, the exact values of efficiency, bandwidth, and losses are evaluated. Figure 3 presents the junction modulation efficiency () and RC bandwidth along with their associated losses, as shown in Figure 3a, and their relation to the penalized FOM (2. RC), as shown in Figure 3b. Each point represents a junction with acceptable performance, where the point’s shape can be mapped to the exact doping masks dimensions and placement. The results reveal the inherent trade-off between RC bandwidth and modulation efficiency, indicating that configurations with low penalized FOM tend to yield a denser cluster of points with higher efficiency but correspondingly lower bandwidth. The most efficient region, characterized by 0.4 V.cm–0.5 V.cm and penalized FOM near 1 (V.cm)2.pF., corresponds to bandwidths of 20 GHz–80 GHz. Conversely, designs achieving the highest bandwidth (~100 GHz) exhibit lower efficiency, with values of 0.8 V.cm–1.1 V.cm.

Figure 3.

Coarse sweep results showing trade-offs in junction modulation efficiency and bandwidth ( vs. BW), with (a) colored by loss and (b) colored by penalized FOM.

3.1. Optimized Junctions

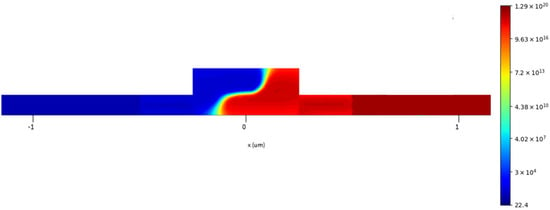

The findings show that an L-shaped junction provides the highest efficiency at V.cm while still maintaining an appropriate bandwidth of almost 46.72 GHz. The charge profile of the junction is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

L-shaped junction profile.

On the other hand, when maximizing the bandwidth with a constraint placed on efficiency, where is kept below 0.8 V.cm (a maximum 2× degradation compared to typical LPNs), the results shown in Figure 5 indicate that an S-shaped junction has the highest RC bandwidth at 103.35 GHz while maintaining an appropriate efficiency of almost 0.664 V.cm.

Figure 5.

S-shaped junction profile.

It can be deduced that a compromise between bandwidth and efficiency can manifest in a junction that combines both L-like and S-like profiles. When optimizing for the FOM with penalized , the resulting newly proposed junctions were found to have an N-like profile, as shown in Figure 6. It can be observed that different junction profiles have been achieved based on different doping mask alignments. Referring to the illustrative schematic in Figure 2, the mask alignments needed in the fabrication process to achieve the junctions shown below have the same shallow P-doping mask width (W2) of 125 nm. The difference in the doping profiles among those junctions lies in the achieved shallow and semi-deep P-doping region depths (H-left and H-right) and the semi-deep P-doping mask width (W1), with junctions N-shape I, II, and III having W1 of 125 nm, while N-shape IV has W1 of 62.5 nm. Furthermore, the doping energy by which the impurities are introduced into the silicon dictates the shallow- and semi-deep-doping region depths. The difference in the energy applied to each region gives the junctions their N-like profile. The previously mentioned N-shaped junctions have the same H-right of 155 nm and different H-left values of 110 nm, 155 nm, 65 nm, and 110 nm, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the geometrical parameters of the mentioned N-shaped junctions. Such geometries result in different modulation efficiencies and bandwidths due to the different depletion junction shapes. The bandwidth and efficiency for these junctions range from 69 GHz to 93 GHz and 0.54 V.cm to 0.61 V.cm, respectively. The different junction simulation results are summarized in Table 2. As mentioned previously, this FOM penalty adds emphasis to the modulation efficiency by increasing its weight; if it is desired to have a junction with higher bandwidth, with the efficiency being of lower priority but not as low as in junctions optimized solely for bandwidth, the weights can be tailored as needed.

Figure 6.

Optimized (a) N-shape I, (b) N-shape II, (c) N-shape III, and (d) N-shape IV junction profiles.

Table 1.

Summary of the geometrical parameters for the chosen N-shaped junction configurations.

Table 2.

Summary of the optimized junction results.

3.2. MRM Study

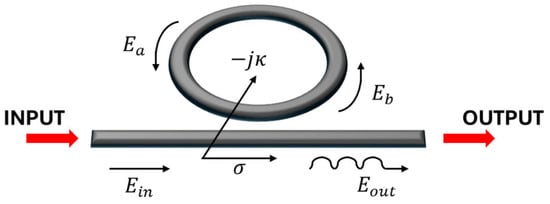

To demonstrate the significant impact of junction profile optimization on the performance of a typical compact modulator, this study uses an all-pass ring-based MRM as an example, as illustrated in Figure 7, with the following static transfer function [23]:

where is the ring round-trip loss, is the coefficient of the power coupled into the ring, is the transmitted power coefficient, and is the circumference of the ring. Meanwhile, the dynamic response can be expressed as follows [24]:

where is the round-trip time. The MRM used in this study has a radius of 10 μm. Using L-shaped and N-shaped junctions in the MRM, the ring is studied in Lumerical INTERCONNECT, where the RLM, OMA, ER, and EO bandwidths are examined. The RLM is the ratio between the smaller of the two modulation amplitudes and the larger one, assessing the symmetry of the modulation levels and therefore the modulation linearity. Performance improves as the RLM approaches unity, indicating perfect balance between the power levels and ideal linearity. The OMA is defined as where and are the high and low power levels, respectively. Additionally, an OMA relative to 0 dBm input power (rOMA) is defined as . Throughout the following sections, the rOMA is reported in its absolute value; accordingly, its reduction is desirable. The newly proposed junctions are compared to conventional ones, particularly the VPN and LPN junctions, as shown in Figure 8. For the junction comparison to be conclusive, a fixed peak-to-peak voltage swing of 2 V is applied, the same insertion loss (IL) of approximately 6 dB is enforced, as it lies near the maximum OMA region, and the same quality factor (Q) ranging from 3400 to 3500 is chosen for each design by varying the power coupling coefficient into the ring. Q is kept the same for all MRMs to assess the modulation efficiencies of the different PN junctions. After initial assessment of the MRM behavior at the previously mentioned junctions, it was found that increasing the doping concentration to 7 × 1018 cm−3 results in better overall performance for the LPN, L-shaped, and N-shaped junctions. Meanwhile, the VPN exhibits the highest round-trip losses; consequently, its doping level is kept at 5 × 1018 cm−3 for the MRM to demonstrate the same quality factor and insertion loss as its counterparts. Accordingly, the power coupling coefficient () was set to 15%, 11%, 17%, and 17% for the LPN-, VPN-, L-shaped-, and N-shaped-junction-based MRMs, respectively. Table 3 summarizes the modulation efficiency, RC bandwidth, round-trip losses, and doping concentrations for each junction. The EO bandwidth of the MRM is limited by both the optical and the electrical (RC) bandwidths, where the dominant factor depends on the operating region. Accordingly, the RC bandwidth values provided in the table are not the only metric determining which junction can provide a higher 3 dB EO bandwidth, as explained in the next section.

Figure 7.

All-pass ring resonator.

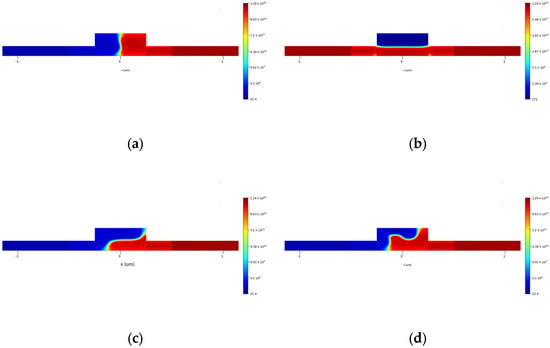

Figure 8.

(a) LPN, (b) VPN, (c) L-shaped, (d) N-shaped junction profiles.

Table 3.

Chosen junctions for MRM implementation.

- Lateral (LPN) Junction

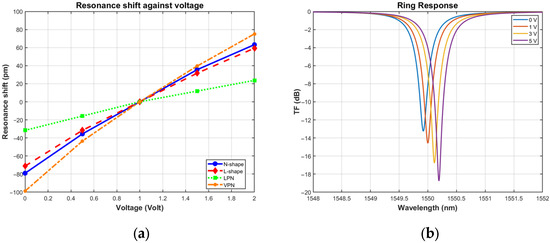

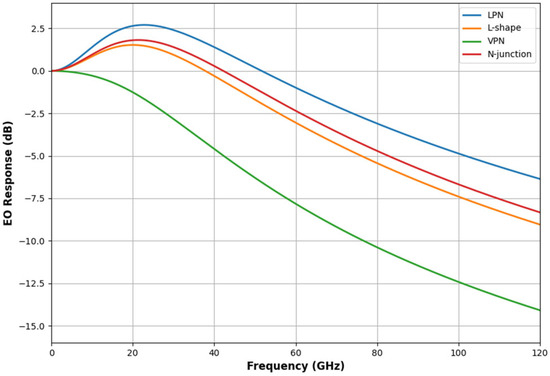

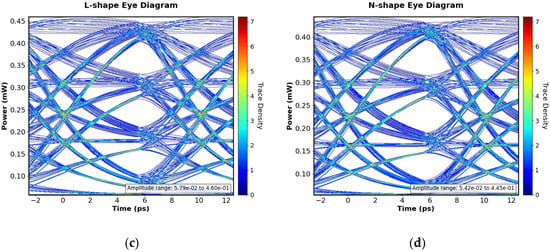

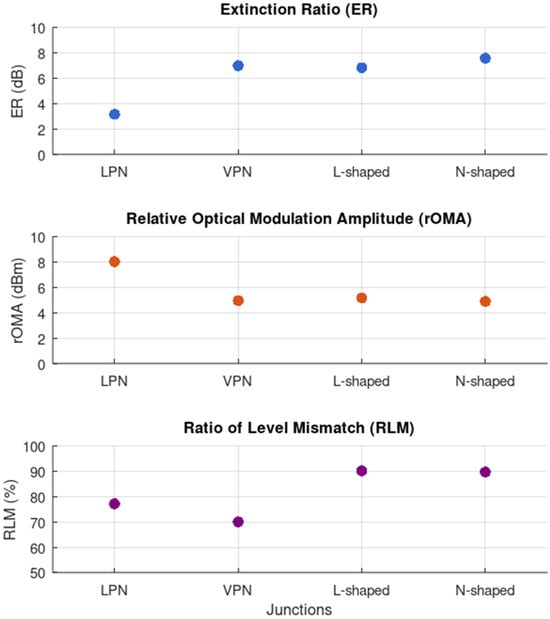

As discussed previously, lateral junctions offer a smaller depletion region and therefore have minimal overlap between the free carriers and the optical mode. Implementing them in an MRM is expected to provide a wide bandwidth (low capacitance) at a low modulation efficiency. The MRM with the LPN junction shows a relatively weak resonance shift of 11 pm/V, as shown in Figure 9a. Although the LPN-MRM, among all the presented junctions, offers the widest 3 dB EO bandwidth at 80 GHz, as illustrated in Figure 10, it demonstrates the worst rOMA at 8.03 dBm, the lowest ER at 3.15 dB, and moderate linearity with an RLM of 77.16%.

Figure 9.

(a) Resonance shift with the applied voltage for the MRMs with the proposed junctions. (b) Ring response for the N-shaped-junction-based MRM.

Figure 10.

MRM EO response for the MRM with the proposed junctions.

- Vertical (VPN) Junction

In contrast, vertical junctions offer a relatively high overlap between the free carriers and the optical mode, making them the conventionally optimal choice for high modulation efficiency. The recorded resonance shift is significantly higher (3.64× increase) than that of the LPN, at almost 40 pm/V compared to 11 pm/V. Additionally, the VPN-MRM shows a high ER of 6.99 dB and a concurrent improvement in rOMA, compared to the LPN, decreasing to 4.96 dBm. Nevertheless, VPN junctions typically have limited RC bandwidth due to their large capacitance. Figure 10 shows a 3 dB EO bandwidth of 31 GHz, the lowest value observed among all the evaluated junctions. Figure 9a also shows that the VPN-MRM exhibits the poorest linearity, with an RLM of 70%.

- L-shaped Junction

L-shaped junctions offer a solution to the bandwidth limitation of VPNs while maintaining only a slight decrease in their high efficiency, due to the nature of their profile being a combination of both vertical and horizontal components, favoring the horizontal [25]. Accordingly, the MRM exhibits a resonance shift of approximately 30 pm/V and a 3 dB EO bandwidth of 60 GHz, as shown in Figure 10, while maintaining a high ER of 6.83 dB, a low rOMA of 5.17 dBm, and a significant enhancement in the RLM, compared to both the LPN- and VPN-MRMs, reaching 90.1%.

- N-shaped Junction

Extending the previously explained trade-off offered by the L-shaped junction, it can be observed that by alternating between vertical and lateral profiles along the junction, an optimal junction can be obtained. The predominantly N-shaped profile that appears in almost all junctions optimized for the -penalized FOM offers the best trade-off between efficiency, bandwidth, and junction losses. The proposed N-shaped junction, when implemented in the MRM at the same quality factor, exhibits a slightly higher resonance shift than the L-shaped junction at approximately 35 pm/V and the second-highest 3 dB EO bandwidth among the junctions under comparison at 66 GHz, as shown in Figure 10. Additionally, it exhibits the highest ER at 7.58 dB and high linearity with an RLM of 89.69%, simultaneously achieving the best rOMA at 4.9 dBm. This illustrates how reliable this profile approach is for increasing the bandwidth compared to the VPN while maintaining a robust enhancement in modulation efficiency compared to the LPN. Figure 9b shows the MRM response at different biasing voltages.

4. Discussion

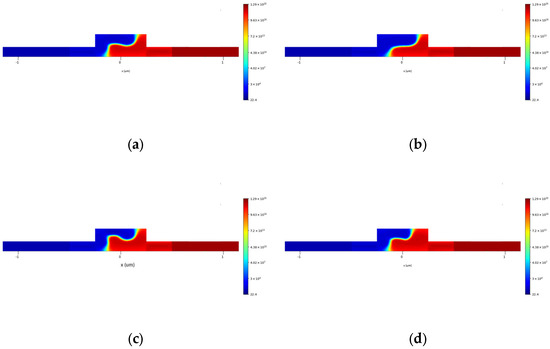

4.1. Mode Overlap Comparison

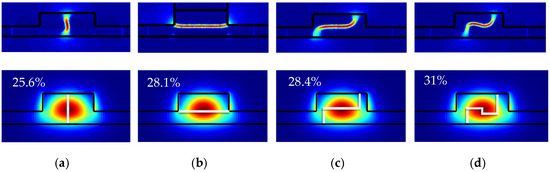

VPN junctions tend to provide higher efficiency due to their horizontal profile that maximizes the overlap with the optical mode (28.1%), whereas the LPN exhibits the least overlap at 25.6%. On the other hand, the L-shaped junctions approach the lateral shape on the sides and the VPN shape in the middle, increasing the overlap compared to the LPN, with an overlap of 28.4%. Yet, it has a smaller depletion area, minimizing its capacitance, and hence increasing its RC bandwidth as illustrated in Section 3. Meanwhile, the proposed N-shaped junction provides a rational compromise between the two junctions; with the central section of the depletion region combining both horizontal and vertical profiles and the side sections being vertical, increasing the overlap to 31%, which is the highest among all the other discussed shapes, and simultaneously decreasing the depletion area, consequently decreasing the capacitance and increasing the RC bandwidth compared to the VPN. Intuitively, efficiency should increase with the overlap, but the efficiency also depends on the doping type with which most of the overlap occurs, and the depletion width variation with modulation. Figure 11 illustrates the differences discussed in the modal overlap and the electrostatic field distribution among the different junctions.

Figure 11.

Mode overlap illustration. The first row is the electrostatic field distribution and the second is the charge profile of (a) LPN, (b) VPN, (c) L-shaped, and (d) N-shaped junctions, where the white lines represent the depletion region.

4.2. MRM Performance Comparison

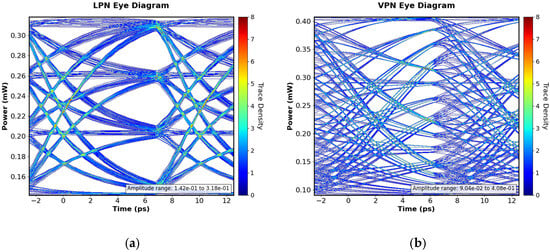

As mentioned in Section 3.2., to perform an equitable assessment of the different junctions’ implementation in the MRM, the applied voltage swing was chosen to be 2 V for the MRM to have an acceptable performance and concurrently remain CMOS-compatible. To clearly illustrate the effect of the used PN junction on the bandwidth of the MRM, Figure 10 shows the different EO responses. Figure 12 depicts the 100 Gbaud PAM4 eye diagrams for the LPN-, VPN-, L-shaped-, and N-shaped-based MRM. The VPN exhibits the lowest 3 dB bandwidth while the N-shaped one offers the highest. All of those junctions have different round-trip losses, with the N-shaped being the least lossy and the VPN being the most, hence the noticeable distinct peaking in each one of them. It is evident how the newly proposed N-shaped junctions elevate the bandwidth performance capabilities of the MRM.

Figure 12.

100 Gbaud eye diagrams for the MRM with the (a) LPN, (b) VPN, (c) L-shaped, and (d) N-shaped junctions.

As discussed above when assessing the implementation of different junctions in the MRM, both the junction efficiency and the RLM are reflected in the resonance shift with the applied voltage as shown in Figure 9a, while the adequacy the EO bandwidth, or lack thereof, manifests in the eye opening as illustrated in Figure 12. The LPN exhibits the lowest resonance shift, hence the lowest efficiency. Even though the VPN demonstrates the highest resonance shift, it shows less ER and OMA than the N-shaped junction because the VPN losses are higher and its coupling coefficient is lower; thus, it is operating in the under-coupled region, with a higher dip in response compared to the N-shaped junction. The N-shaped junction bridges the gap between VPN and LPN most effectively, offering higher efficiency and comparable linearity with respect to the L-shaped counterpart.

Also, from the results presented in Figure 13, the LPN-MRM proves superior in terms of its EO bandwidth yet exhibits a relatively weak ER and the worst rOMA, while the VPN-MRM demonstrates a significant improvement in the rOMA and ER, with a moderate deterioration of the RLM compared to its lateral counterpart. The L-shaped junction retains the substantial improvement in the ER and rOMA achieved by the VPN, with only a slight decline. Notably, the N-shaped optimized junction offers the best trade-off among all the performance specifications as it minimizes the rOMA, simultaneously maximizing the ER and RLM, where ER, rOMA, and RLM are calculated based on the static MRM model. Table 4 summarizes the performance of the MRM for the various junction configurations presented above.

Figure 13.

Summary of ER, rOMA, RLM, and 3 dB EO BW of different junctions.

Table 4.

MRM performance summary at the different chosen junctions.

Furthermore, the impact of process variations on the N-shaped junction performance was investigated. The analyzed variations include deviations in the semi-deep P-doping mask alignment (60 nm), the P-doping and N-doping mask alignments (60 nm), the waveguide width (20 nm), and the rib etch depth (10 nm), representing realistic tolerances typically observed in standard SiPh fabrication processes. The efficiency () varies between 0.45 V.cm and 0.67 V.cm, compared to the nominal value of 0.46 V.cm. Similarly, the loss fluctuates around the nominal 8.32 dB/mm, with a maximum deviation of approximately 1 dB/mm. The bandwidth, on the other hand, exhibits the highest sensitivity to the process variations, ranging from 47.6 GHz to 107.5 GHz, with the nominal bandwidth being 68.22 GHz. Nevertheless, this bandwidth range can still provide adequate performance. These results confirm the robustness of the design under typical fabrication deviations. Table 5 details the impact of each process variation on the junction’s performance parameters.

Table 5.

Impact of process variations on N-shaped junction performance parameters.

5. Conclusions

This work examined the potential of PN junction optimization for optical modulators, to support the requirements of different applications for high-speed optical communication networks. Our work examined the trade-off between modulation efficiency and RC bandwidth, and highlighted its impact on practical modulator (MRM) performance. It demonstrated the importance of tailoring the junction profile shape. The L-shaped junctions show an 80% improvement in efficiency compared to LPN but experience a significant compromise in the RC bandwidth. Meanwhile, when its performance is assessed in an MRM, it offered an adequate 3 dB EO bandwidth at 60 GHz, a high ER of 6.83 dB, and a low rOMA of 5.17 dBm. On the other hand, N-shaped junctions offer up to 60% improvement in efficiency, compared to LPN junctions, with a modest penalty to the RC bandwidth. When implemented in the MRM, they show a high ER of 7.58 dB, a low rOMA of 4.9 dBm, and a sufficiently fast modulation bandwidth of 66 GHz. The results and their related discussions show how the proposed N-shaped junctions offer the optimal middle ground among the presented trade-offs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., C.M. and A.E.-D.; methodology, M.H.; software, M.H. and A.E.-D.; validation, M.H., C.M. and A.E.-D.; formal analysis, M.H.; investigation, M.H., C.M. and A.E.-D.; resources, D.K., E.E.-F. and A.F.; data curation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, M.H., C.M., A.E.-D., D.K., E.E.-F. and A.F.; visualization, M.H. and C.M.; supervision, D.K., E.E.-F. and A.F.; project administration, D.K., E.E.-F. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Mahmoud Hamouda, Carine Mankarious, Aser El-Dahshan, Alaa Fathy, and Diaa Khalil were employed by InfiniLink. The remaining author, Eslam El-Fiky, declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Shekhar, S.; Bogaerts, W.; Chrostowski, L.; Bowers, J.E.; Hochberg, M.; Soref, R.; Shastri, B.J. Roadmapping the next Generation of Silicon Photonics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Hermans, A.; Wohlfeil, B.; Petousi, D.; Kuyken, B.; Thourhout, D.V.; Baets, R.G. Taking Silicon Photonics Modulators to a Higher Performance Level: State-of-the-Art and a Review of New Technologies. Adv. Photonics 2021, 3, 024003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Xiao, X.; Yu, S. Silicon Intensity Mach–Zehnder Modulator for Single Lane 100 Gb/s Applications. Photonics Res. 2018, 6, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltes, F.; Mai, C.; Caimi, D.; Kroh, M.; Popoff, Y.; Winzer, G.; Petousi, D.; Lischke, S.; Ortmann, J.E.; Czornomaz, L.; et al. A BaTiO3-Based Electro-Optic Pockels Modulator Monolithically Integrated on an Advanced Silicon Photonics Platform. J. Light. Technol. 2019, 37, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ma, X.; Liu, G.; Dai, X.; Lu, Q.; Guo, W. High Performance Thin-Film Lithium Niobate Modulator on Silicon Substrate with a Thick Silica Buffer Layer. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 20334–20344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Kumar, R.; Sakib, M.; Driscoll, J.B.; Jayatilleka, H.; Rong, H. A 128 Gb/s PAM4 Silicon Microring Modulator with Integrated Thermo-Optic Resonance Tuning. J. Light. Technol. 2019, 37, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeber, S.; Palmer, R.; Lauermann, M.; Heni, W.; Elder, D.L.; Korn, D.; Woessner, M.; Alloatti, L.; Koenig, S.; Schindler, P.C.; et al. Femtojoule Electro-Optic Modulation Using a Silicon–Organic Hybrid Device. Light Sci. Appl. 2015, 4, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbist, J.; Verplaetse, M.; Lambrecht, J.; Srivinasan, S.A.; De Heyn, P.; De Keulenaer, T.; Pierco, R.; Vyncke, A.; Absil, P.; Yin, X.; et al. 100 Gb/s DAC-Less and DSP-Free Transmitters Using GeSi EAMs for Short-Reach Optical Interconnects. In Proceedings of the 2018 Optical Fiber Communications Conference and Exposition (OFC), San Diego, CA, USA, 11–15 March 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S.A.; Porret, C.; Vissers, E.; Favia, P.; De Coster, J.; Bender, H.; Loo, R.; Van Thourhout, D.; Van Campenhout, J.; Pantouvaki, M. High Absorption Contrast Quantum Confined Stark Effect in Ultra-Thin Ge/SiGe Quantum Well Stacks Grown on Si. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2020, 56, 5200207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timurdogan, E.; Sorace-Agaskar, C.M.; Sun, J.; Shah Hosseini, E.; Biberman, A.; Watts, M.R. An Ultralow Power Athermal Silicon Modulator. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ji, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L. Electro-Optical Response Analysis of a 40 Gb/s Silicon Mach-Zehnder Optical Modulator. J. Light. Technol. 2013, 31, 2434–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Spuesens, T.; Baets, R.; Bogaerts, W. Open-Access Silicon Photonics: Current Status and Emerging Initiatives. Proc. IEEE 2018, 106, 2313–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikata, J.; Takahashi, S.; Takahashi, M.; Noguchi, M.; Nakamura, T.; Arakawa, Y. High-Performance MOS-Capacitor-Type Si Optical Modulator and Surface-Illumination-Type Ge Photodetector for Optical Interconnection. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 55, 04EC01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Veerasubramanian, V.; Ghosh, S.; Samani, A.; Zhong, Q.; Plant, D.V. High-Speed Compact Silicon Photonic Michelson Interferometric Modulator. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 26788–26802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, Z.; Sacher, W.D.; Huang, Y.; Mikkelsen, J.C.; Yang, Y.; Luo, X.; Dumais, P.; Goodwill, D.; Bahrami, H.; Lo, P.G.-Q.; et al. U-Shaped PN Junctions for Efficient Silicon Mach-Zehnder and Microring Modulators in the O-Band. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 8425–8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Li, X.; Xu, H.; Hu, Y.; Xiong, K.; Li, Z.; Chu, T.; Yu, J.; Yu, Y. 44-Gb/s Silicon Microring Modulators Based on Zigzag PN Junctions. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2012, 24, 1712–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Xiong, K.; Li, Z.; Chu, T.; Yu, Y.; Yu, J. 25 Gbit/s Silicon Microring Modulator Based on Misalignment-Tolerant Interleaved PN Junctions. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 2507–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soref, R.; Bennett, B. Electrooptical Effects in Silicon. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1987, 23, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jin, T.; Bae, Y. A Comparative Simulation Study on Lateral and L-Shaped PN Junction Phase Shifters for Single-Drive 50 Gbps Lumped Mach–Zehnder Modulators. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 60, 052002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maegami, Y.; Cong, G.; Ohno, M.; Okano, M.; Itoh, K.; Nishiyama, N.; Arai, S.; Yamada, K. High-Efficiency Silicon Mach-Zehnder Modulator with Vertical PN Junction Based on Fabrication-Friendly Strip-Loaded Waveguide. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 14th International Conference on Group IV Photonics (GFP), Berlin, Germany, 23–25 August 2017; pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzens, J. High-Speed Silicon Photonics Modulators. Proc. IEEE 2018, 106, 2158–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, J.D.; Deal, M.D.; Griffin, P.B. Silicon VLSI Technology: Fundamentals, Practice, and Modeling; Prentice Hall Electronics and VLSI Series; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaerts, W.; De Heyn, P.; Van Vaerenbergh, T.; De Vos, K.; Kumar Selvaraja, S.; Claes, T.; Dumon, P.; Bienstman, P.; Van Thourhout, D.; Baets, R. Silicon Microring Resonators. Laser Photonics Rev. 2012, 6, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacher, W.D.; Poon, J.K.S. Dynamics of Microring Resonator Modulators. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 15741–15753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Peng, Y.; Sorin, W.V.; Cheung, S.; Huang, Z.; Liang, D.; Fiorentino, M.; Beausoleil, R.G. A 5 × 200 Gbps Microring Modulator Silicon Chip Empowered by Two-Segment Z-Shape Junctions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).