Abstract

Diabetes poses a global health challenge, with accurate classification and blood glucose prediction being crucial for effective management and treatment. However, traditional methods are hindered by data scarcity. This study aims to use deep learning to complete data expansion to improve the accuracy of diabetes classification and blood glucose prediction. Raman spectroscopy, Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks (CGAN), and a suite of optimized regression models were employed, with the best hyperparameter combinations for each model on the current dataset determined through grid search and cross-validation. The introduction of CGAN for data augmentation effectively addressed the issue of data scarcity, resulting in a significant improvement in overall performance. The top-performing model achieved a diabetes classification accuracy of over 99% and a blood glucose prediction error of 0.28 mg/dL. The application of CGAN notably enhanced both classification and prediction accuracy, a trend further supported by performance improvements illustrated through comparative graphs. This integrated approach provides a robust solution for accurate diabetes diagnosis and blood glucose prediction, demonstrating potential advancements in non-invasive diabetes management.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus remains a significant global health concern, with rising prevalence and associated complications posing substantial challenges to healthcare systems [1,2,3]. Accurate and non-invasive methods for diabetes diagnosis and blood glucose prediction are crucial for timely intervention and effective management [4,5,6]. Traditional diagnostic approaches often face limitations, particularly in dealing with limited datasets and achieving a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency [7]. In the realm of optical diagnostics, Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a promising tool for its ability to provide molecular information from biological samples [8,9,10]. Pandey R et al. introduced a mass transfer model into a chemometric algorithm to accurately measure blood glucose using Raman spectroscopy [11]. Dingari N C et al. studied the correlation problem of blood glucose detection based on Raman spectroscopy, and verified the influence of chance correlation through physical tissue model, animal model and human experiment [12]. With the development of artificial intelligence, researchers have also introduced the technology into the detection of diabetes and the prediction of blood sugar values [13,14,15,16]. Pian F et al. used one-dimensional shallow convolutional neural network structure combined with elastic network to predict blood glucose concentration by Raman spectra for the first time [17]. Wang Q et al. proposed a one-dimensional convolutional neural network based on Gramian Angular field to convert one-Villaman spectral data into images and use it to predict biochemical values of blood glucose [18]. However, challenges persist in overcoming data scarcity, hindering the full realization of its potential in diabetes research. The advent of Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) offers a compelling solution for addressing this limitation [19], enabling the augmentation of limited datasets.

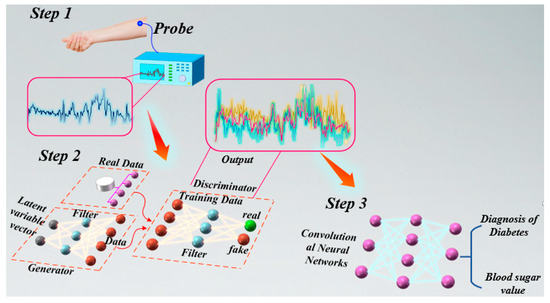

In this study, we aim to synergize Raman spectroscopy, Conditional GAN, and neural networks to improve diabetes classification accuracy and blood glucose prediction precision. This integration addresses current challenges in data availability and computational efficiency, advancing non-invasive diabetes diagnostics. Our study has two primary objectives: first, demonstrating the effectiveness of Conditional GAN in augmenting Raman spectral datasets for diabetes research, and second, showcasing enhanced model performance in diabetes classification and blood glucose prediction, the overall workflow framework is illustrated in Figure 1. By leveraging GAN’s data augmentation to overcome data scarcity, our approach yielded substantial performance improvements. The optimal model achieved an impressive 99% accuracy in diabetes classification, with a minimal blood glucose prediction error of 0.21. Analysis of classification results for both original and augmented data revealed that each model significantly improved accuracy (11–13%) for diabetes classification and demonstrated enhancements in blood glucose prediction errors (0.5–1.2); the overall work flow is shown in Figure 1. These results underscore the efficacy of our methodology, contributing to advancements in non-invasive diabetes diagnostics and potential enhancements for personalized healthcare interventions. Our research strives to offer a robust methodology for improved diabetes diagnostics, potentially paving the way for more personalized and effective healthcare interventions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework. Collecting glucose spectra from volunteers’ forearms, we enhance the dataset using CGAN, and subsequently employ models such as CNN for the classification of diabetes and the specific prediction of blood glucose levels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Data

This study involving 46 volunteers, to measure blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels using Raman spectroscopy and conventional methods. The protocol for the present study was approved by the local ethics committee (approval number: CEPREC 08–001). All participants included in the presented analysis provided written informed consent to participate, and all study procedures were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The forearm was identified as the most reliable data source through comparative analysis, leading to further investigation. Measurements of glucose and HbA1c levels were taken, and HbA1c was chosen as a diagnostic marker for diabetes due to its ability to offer a long-term average of blood glucose levels. The HbA1c values ranged from 5.2 to 14%. Following diabetes diagnostic criteria, 42 participants were diagnosed with diabetes, and 4 were healthy. This study employed the QE65000 Raman spectrometer from Ocean Optics® (Dunedin, FL, USA) and the RIP-RPS-785 Raman probe from InPhotonics® (Norwood, MA, USA). The excitation laser power was specified as 60 mW (determined according to the instrument specifications). A light-shielding material was coated on the surface of the Raman probe to block external light, with a focal length of 7 mm; the collected Raman spectral data were subjected to signal enhancement and denoising preprocessing. After collecting the blood samples, low-temperature centrifugation was performed immediately. The InPhotonics® RIP-RPS-785 Raman probe was used and placed close to the surface of the treated blood sample. The sample was irradiated with a laser power of 60 mW to excite the molecules in the sample to generate Raman scattered light. The scattered light was collected by the probe and transmitted to the spectrometer. The vibration modes of the sample molecules were obtained by analyzing the frequency changes in the scattered light, and then the spectral characteristics of their chemical composition were acquired. Measurements were conducted under controlled environmental conditions, and a total of 414 blood glucose Raman spectra were collected from the forearm location [20], the collected data were normalized.

2.2. Model Building and Training

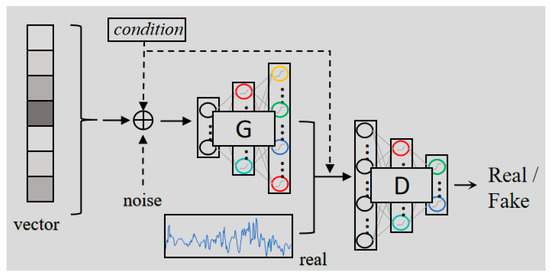

To address the challenge of limited data, we employed CGAN for data augmentation [21]. CGAN enhance data quality by utilizing the adversarial interaction between the generator and discriminator networks. This framework offers better control compared to traditional GAN, enabling the generation of more realistic and structured data that better matches the distribution of the original dataset. The CGAN network architecture of this study is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The architecture of CGAN, enhancing the quality of generated data through the iterative process of generator and discriminator confrontation.

The architecture of a CGAN consists of two main components: the generator and the discriminator. The generator network produces synthetic data, while the discriminator distinguishes between real and generated data. The generator is trained to produce data that is increasingly similar to the real data, while the discriminator is trained to identify whether a sample is real or fake. The generator receives two inputs, a random noise vector z and a conditioning variable y. The conditioning variable can represent labels or other relevant attributes, such as specific Raman signal features, which guide the data generation process. The generator transforms the noise and the conditional input through a series of layers, fully connected layers, convolutional layers, batch normalization, and leaky ReLU activations. The output is synthetic data that ideally resembles the real data distribution. The generator’s objective is to learn a mapping G(z,y) that produces samples that are indistinguishable from real data x. In other words, G should generate realistic Raman spectra conditioned on y, whether y represents class labels or other domain-specific features.

The discriminator’s role is to distinguish between real and generated data. It receives both real data x and generated data, conditioned on y. It outputs a probability D(x,y) that the input is real, meaning it belongs to the true data distribution. The discriminator is tasked with maximizing its ability to correctly identify whether data is real or fake, while the generator works to fool the discriminator by producing data that appears real. This adversarial relationship drives the training process.

The generator and discriminator are trained in an adversarial manner, meaning that they optimize their respective objective functions in opposition to each other. The goal is for the generator to create synthetic data that is so realistic that the discriminator cannot reliably distinguish it from real data. The generator loss encourages the generator to produce data that the discriminator classifies as real. Typically, this is formulated as

Here, is the generator’s loss, and denotes the expected value over the noise vector z and the conditioning variable y. The generator aims to minimize this loss by producing samples that maximize D’s output, which makes the discriminator more likely to classify generated samples as real.

The discriminator loss, on the other hand, encourages the discriminator to correctly classify real and generated data. It is typically formulated as

Here, is the discriminator loss, where the first term corresponds to the loss from real data and the second term corresponds to the loss from generated data. The discriminator goal is to minimize this loss, thereby improving its ability to distinguish real from fake data. The overall optimization problem is a minimax game between the generator and the discriminator. The generator seeks to minimize , while the discriminator seeks to minimize . This adversarial process improves the quality of the generated data over time.

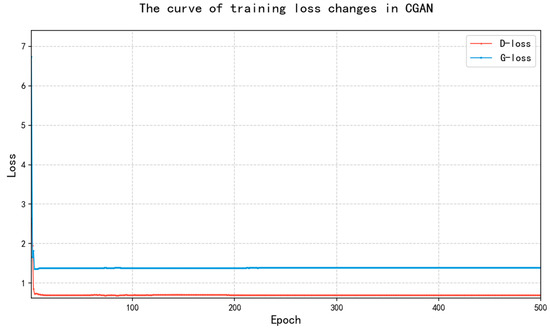

In the CGAN model, the generator receives a 100-dimensional Gaussian noise vector and labels. After expanding the dimensions through fully connected layers, the noise vector is concatenated with the labels along the channel dimension. The resulting vector is then upsampled to 800 points using 4 layers of Conv1D-BN-ReLU. Finally, the output is cropped to 789 points and passed through a Tanh activation function. The discriminator concatenates the spectrum with the corresponding label and extracts features through 2 layers of Conv1D with stride = 2 and LeakyReLU. After flattening, the output is passed through a sigmoid function to produce a probability score for authenticity. The loss function used is binary cross-entropy, and the optimizer is Adam. The learning rate is set to 0.0001, the batch size is 32, and the training consists of 500 epochs. During training, the discriminator and generator are updated alternately until the discriminator’s loss stabilizes at 0.68, and the generator’s loss stabilizes at 1.37. This adversarial optimization continues until both networks converge, producing high-quality synthetic data that is indistinguishable from real Raman spectra. The changes in the loss value during the training process are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The changes in the loss value of the CGAN model during the training process.

The analysis of the plot reveals that initially, the discriminator’s loss value is relatively high and experiences significant fluctuations during the first few epochs. Afterward, it stabilizes at a level of around 0.68. This stabilization aligns with the training setup, where the discriminator is alternately updated with the generator to enhance its ability to distinguish between real and generated samples. The fluctuations in the early stages suggest that the discriminator struggles to differentiate between real and fake data because the generator initially produces low-quality samples. The generator’s loss remains relatively low and stable, staying around 1.0. It quickly reaches this value, indicating that once the discriminator performs better, the generator starts producing relatively good samples. This stable loss suggests that the generator is successfully learning to generate convincing data that is harder for the discriminator to distinguish from real data.

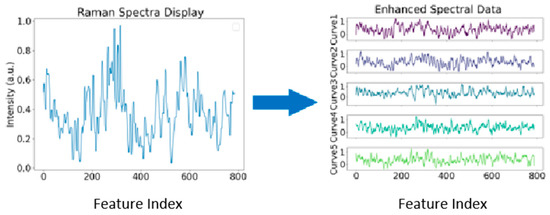

After several epochs, both loss values stabilize, indicating that the model has reached an equilibrium. At this point, the generator and discriminator are effectively competing with each other. The small gap between the generator and discriminator loss values indicates that neither model dominates the other, maintaining a balanced training process. Overall, the analysis of the plot demonstrates that the model training is stable, with the discriminator learning quickly and the generator continually improving its output. The stable loss values indicate that the training is progressing well, and after reaching this stable phase, the model is capable of generating reasonable results. The process of generating data by the model is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Original data generated diverse datasets through CGAN. The figure illustrates the original data alongside the diverse datas generate through CGAN.

The FID score of 9.37 between the generated data and the original data indicates that the generated data is highly similar to the original, also reflecting the high quality of the synthetic spectra. This score suggests that the model has successfully captured the underlying distribution of the original data, making the generated spectra highly realistic. By generating synthetic data that reflects the characteristics of the original data, CGAN helps to expand the dataset, providing more examples for training downstream models, such as classifiers or detectors. In this study, we augmented the original dataset of 414 Raman spectra by generating 1656 additional synthetic samples through a well-trained CGAN model. This resulted in an augmented dataset containing 2070 spectral data points, which is better suited for classification tasks and improves model generalization. The generated data preserves the fundamental characteristics of the original Raman spectra while introducing diversity. By conditioning on various attributes during generation, CGAN ensures that the synthetic data maintains the structural integrity of the original dataset while diversifying the sample space. This approach not only mitigates the problem of data scarcity but also ensures that the generated data can be effectively used for training classifiers.

To comprehensively assess the performance of blood glucose classification and prediction models, we selected a range of models, including Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR), and CNN. These algorithms are constructed under the premise of being data-driven, learning the relationship between input features and target outputs. Each model possesses unique advantages, Random Forest and SVR excel in handling large volumes of data quickly and efficiently, while GBR and CNN demonstrate superior performance in feature extraction and representation learning, enabling higher accuracy and performance in more complex data structures and patterns.

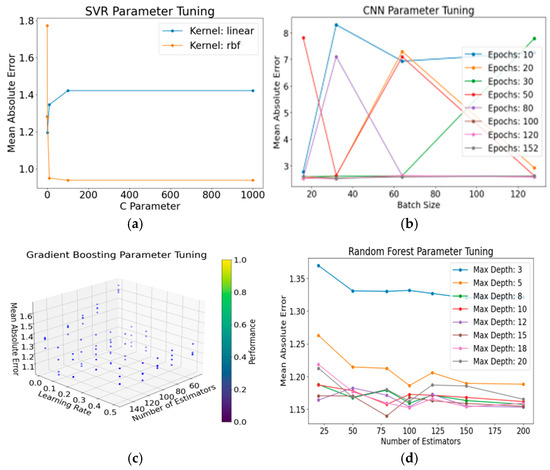

To determine the optimal hyperparameter combinations for each model’s performance on the current dataset, we employed Grid Search coupled with 5-fold Cross-Validation. The dataset was initially partitioned into an 80% training/validation set and a 20% independent test set. During the hyperparameter optimization process, the 80% training/validation data was equally divided into five subsets (folds). The model was iteratively trained and validated, ensuring that each subset served as the validation set exactly once. We selected the hyperparameter combination that performed best by optimizing the mean of the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) from the five validation results. This comprehensive evaluation step ensures a thorough assessment of each model’s performance, resulting in optimized models that achieve better performance in diabetes classification and blood glucose prediction tasks. The performance variations in each model are illustrated in Figure 5, demonstrating the effectiveness of this comprehensive evaluation strategy in achieving optimal performance across various tasks. This approach not only provides a more reliable foundation for experimental results but also offers robust support for subsequent explanations and applications.

Figure 5.

Performance Analysis of Each Model. (a) SVR Parameter Optimization: Evaluation of models with linear and rbf kernels reveals distinct performances across different parameter counts. (b) CNN Parameter Tuning: The model’s performance exhibits variations with different batch sizes under varying training epochs. (c) Gradient Boosting Parameter Optimization: The model showcases diverse performances influenced by distinct estimations, learning rates, and max depths. (d) Random Forest Parameter Tuning: Varied max depths of the model exhibit diverse performances under different estimation counts.

In Table 1, we have meticulously detailed the optimal hyperparameter combinations for a variety of models, identified and tested through a stringent process of selection and experimentation. Hyperparameters such as learning rates, regularization coefficients, and the depth of trees are included, which are crucial for improving the model’s capacity to generalize and for mitigating overfitting. By methodically tuning these parameters, we can ensure that the models reach a higher level of precision and efficiency when tasked with predicting blood sugar levels. Once the optimal hyperparameters were established, we built several network models based on these parameters. These models were thoroughly trained on the training dataset and their performance was subsequently assessed on the validation dataset.

Table 1.

Optimal hyperparameters for different models.

3. Results

3.1. Criteria of Evaluation

We configured the models with the optimal hyperparameters determined on the given dataset and utilized multiple models to classify diabetes and predict blood glucose levels for both the original and enhanced datasets. To ensure a comprehensive assessment of model performance, we employed various evaluation metrics. Classification accuracy was utilized to measure the model’s correctness in diabetes classification tasks, and blood glucose prediction error was employed to assess the model’s performance in continuous tasks. Additionally, we generated confusion matrices to gain detailed insights into the model’s classification results. The assessment metrics for blood glucose prediction error, employing the MAE loss function, and classification accuracy are delineated as follows:

N represents the sample size, signifies the actual blood glucose value, and denotes the blood glucose value predicted by the model.

In this context, TP denotes true positives, TN signifies true negatives, FP represents false positives, and FN stands for false negatives.

3.2. Comparison of Diabetes Classification Between Original Data and Augmented Data

In order to examine whether the CGAN data augmentation method significantly improves model performance and evaluate the model’s generalization capability on both original and enhanced datasets, we conducted a performance comparison between the original spectral data and the data augmented using CGAN. In the diabetes classification task, various optimization models were employed to classify diabetes using both the original and augmented datasets. The corresponding classification accuracies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Detection Accuracy (%) on Different Data by Various Optimal Classifiers.

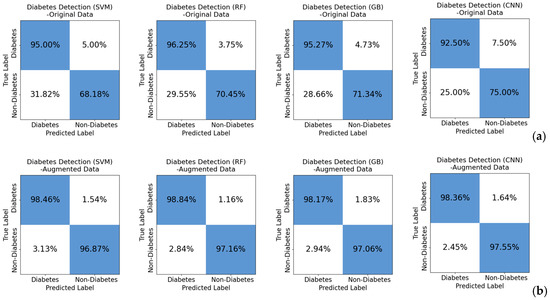

Analysis of Table 2 indicates a significant improvement in diabetes classification accuracy when utilizing CGAN data augmentation. The optimization models, trained on the original dataset, demonstrated commendable performance with classification accuracies ranging from 85% to 88%. However, the introduction of CGAN data augmentation substantially increased the dataset size, resulting in a remarkable improvement in classification accuracy on the augmented dataset, reaching an impressive performance level between 97–99%. This signifies a substantial enhancement in accuracy. The observed improvement is attributed to the richness of data generated by augmentation, allowing the models to benefit from a more diverse dataset and further optimizing their performance. The heightened accuracy, especially on the augmented dataset, underscores the effectiveness of CGAN in generating diverse and information-rich synthetic data. These models, when trained on the augmented dataset, demonstrated an enhanced ability to identify complex patterns and subtle differences related to diabetes, leading to superior classification performance. To provide a more comprehensive view, confusion matrices were constructed and visualized, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix for diabetes classification, (a) shows the classification results for the original data, while (b) presents the classification results for the augmented data. A notable improvement in classification performance is evident with the enhanced data. This offers a detailed insight into the model’s performance, enhancing the ability to distinguish between diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

Insights gained from the confusion matrix highlight notable observations. In the classification detection of non-diabetic patients in the original dataset, only around 70% were correctly identified, with approximately 30% of non-diabetic patients being erroneously classified as diabetic. This imbalance is attributed to the composition of the original dataset, where, out of the 46 volunteers from whom spectra were collected, 42 participants were diagnosed with diabetes, and only 4 were categorized as healthy. In contrast, after data augmentation, this imbalance issue is effectively addressed. Both non-diabetic and diabetic patients are correctly classified, eliminating the challenges posed by the imbalanced nature of the original data.

3.3. Comparison of Blood Glucose Prediction Values Between Original Data and Augmented Data

The blood glucose prediction work was evaluated on both the original dataset and the augmented dataset, using different optimization models to predict blood glucose values on these datasets. The corresponding prediction performance comparison is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

A Comparative on the MAE of Optimal Classifiers Across Diverse Datasets.

Analysis of the table reveals a noteworthy reduction in prediction errors with the incorporation of CGAN data augmentation. The HbA1c values associated with the spectra range from 5.2 to 14. Different optimization models trained on the original dataset exhibit prediction errors in the range of 1 to 1.25. However, the introduction of CGAN data augmentation significantly increased the dataset size, leading to a remarkable enhancement in prediction performance on the augmented dataset, with errors reduced to the range of 0.28 to 0.42. The notable reduction in prediction errors indicates that CGAN data augmentation effectively addresses the complexities present in the original datasets, allowing the models to generalize better and produce more accurate predictions. These findings underscore the significance of CGAN data augmentation in improving the robustness and accuracy of blood glucose prediction models. To visually compare the prediction results of different models trained on original and augmented datasets, we plotted their predictions, as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

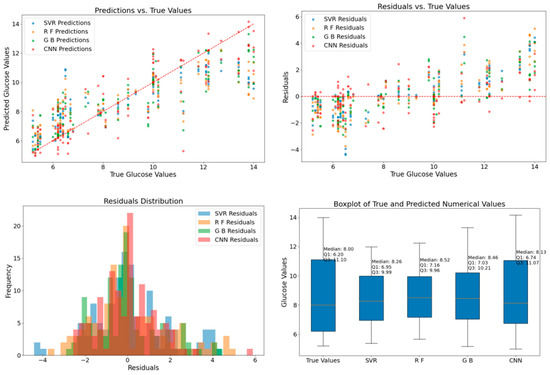

Figure 7.

Comparison of Classifier Predictions on the Original Dataset.

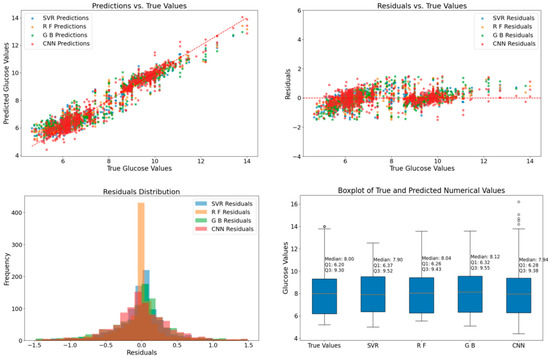

Figure 8.

Comparison of Classifier Predictions on the Augmented Dataset.

Figure 7 presents the prediction results of different models on the original dataset. Through visual means such as scatter plots, residual plots, residual histograms, and box plots, the prediction performance of each model can be comprehensively evaluated. In the detection of the original dataset, the prediction data of each model exhibits a relatively dispersed distribution pattern. The scatter plot shows that the degree of dispersion between the predicted values and the true values is relatively high, indicating that it is difficult for the models to establish a close and stable corresponding relationship. This implies that the original dataset has a relatively high complexity, and its inherent patterns are not easily captured by the models. Whether it is Random Forest based on the tree structure, SVR which is good at handling linear relationships, Gradient Boosting of the ensemble learning type, or CNN with powerful feature extraction capabilities, all expose limitations when facing the original data, resulting in significant fluctuations in the prediction results. The residual plot and the residual histogram further confirm this point. They show that the prediction errors of the models vary within the relatively wide interval of [−4, 6], and most of the errors are concentrated within the interval of [−2, 2]. This indicates that although the models have the ability to approximate the true values to a certain extent, there are still some cases where the prediction errors exceed the ideal range, reflecting the heterogeneity of the original data. The box plot shows that the median of the true data is 8, the first quartile (Q1) is 6.20, and the third quartile (Q3) is 11.10. The medians of the prediction results of different models are relatively close to the median of the true data, but the changes in the quartiles indicate that there are significant differences in the degree of dispersion of the prediction results of the models, reflecting the deficiencies of the models in fitting the distribution of the original data.

Figure 8 showcases the prediction results of different models on the dataset augmented by CGAN. Through the same visual means, the impact of data augmentation on the prediction performance of the models can be evaluated. In the detection of the augmented dataset, the prediction data of each model presents a significantly more concentrated distribution state, and most of the prediction points are closely clustered around the line segment representing the true values. This change vividly demonstrates the positive effect of the data augmentation strategy. The data generated by CGAN enriches the diversity of the original dataset and supplements the key pattern information, enabling the models to better understand the data patterns and generate more compact and stable prediction results, significantly improving the accuracy and stability of the predictions. The residual plot and the residual histogram show that the error range is significantly reduced and concentrated within the interval of [−1.5, 1.5]. This indicates that after data augmentation, the models can more sensitively capture the subtle features in the data, fit the true values more closely during prediction, have smaller and more stable errors, and reduce the occurrence of large errors caused by the complexity of the original data. The box plot shows that the median of the true data is 8, the first quartile (Q1) is 6.20, and the third quartile (Q3) is 9.3. The medians of the prediction results of each model are close to the median of the true data, and the ranges of the quartiles show a better degree of fitting, indicating that each model has achieved significant improvements in prediction accuracy and stability after data augmentation.

Through the systematic comparative analysis of the original dataset and the dataset augmented by the generative adversarial network, we clearly witness the significant impact of data augmentation on the prediction performance of each model. In the stage of the original dataset, each model faced problems such as dispersed data, a relatively large range of error fluctuations, and poor fit between the prediction result distribution and the true data, reflecting the difficulties of the models in dealing with complex original data. However, after data augmentation, each model has shown significant improvements in the concentration degree of prediction data, the error range, and the degree of fitting with the data distribution, fully demonstrating the effectiveness and importance of the data augmentation strategy in enhancing the prediction ability of the models and optimizing the overall performance of the models.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the effective use of CGAN for data augmentation in diabetes diagnostics and blood glucose prediction. Augmented data significantly improved diabetes detection accuracy, increasing it from 86% to 99%, which is crucial for timely interventions and personalized healthcare. Additionally, blood glucose prediction precision was enhanced, with the mean absolute error reduced from 1.18 to 0.28, supporting better diabetes management. However, we acknowledge the issue of imbalanced data, with a higher number of healthy samples compared to diabetic samples. This imbalance may introduce biases, particularly in detecting the minority class. Although data augmentation helped mitigate this, the imbalance remains a concern. Future work will focus on acquiring a more balanced dataset and exploring advanced techniques like class-weighted loss functions, SMOTE, and focal loss to further address this challenge.

The findings highlight the transformative impact of data augmentation, specifically using CGAN, in improving diagnostic accuracy and prediction precision. This work provides a foundation for more reliable, non-invasive diabetes diagnostics and contributes to the ongoing development of personalized medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and S.C.; methodology, J.N.; software, Y.Z.; validation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.C.; supervision, J.S.; project administration, Y.D.; funding acquisition, Y.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62171288) and the Innovation Team Project for General Universities in Guangdong Province (Natural Science) (Grant No. 2024KCXTD065).

Data Availability Statement

The data can be obtained on the Kaggle website.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tomic, D.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.B.; Florez, J.C. Genetics of diabetes mellitus and diabetes complications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.D.; Gloyn, A.L.; Evans-Molina, C.; Joseph, J.J.; Misra, S.; Pajvani, U.B.; Simcox, J.; Susztak, K.; Drucker, D.J. Diabetes mellitus—Progress and opportunities in the evolving epidemic. Cell 2024, 187, 3789–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hædersdal, S.; Andersen, A.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsbøll, T. Revisiting the role of glucagon in health, diabetes mellitus and other metabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D.; Immanuel, J.; Hague, W.M.; Teede, H.; Nolan, C.J.; Peek, M.J.; Flack, J.R.; McLean, M.; Wong, V.; Hibbert, E.; et al. Treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed early in pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2132–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanan, P.; Magee, L.A.; Banerjee, A.; Coleman, M.A.; Von Dadelszen, P.; Denison, F.; Farmer, A.; Finer, S.; Fox-Rushby, J.; Holt, R.; et al. Gestational diabetes: Opportunities for improving maternal and child health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Qu, S. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and cancers and its underlying mechanisms. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 800995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorio, A.; Saito, R. Raman spectroscopy for carbon nanotube applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 021102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapliyal, V.; Alabdulkarim, M.E.; Whelan, D.R.; Mainali, B.; Maxwell, J.L. A concise review of the Raman spectra of carbon allotropes. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 127, 109180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Deng, L.; Kinloch, I.A.; Young, R.J. Raman spectroscopy of carbon materials and their composites: Graphene, nanotubes and fibres. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 135, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Paidi, S.K.; Valdez, T.A.; Zhang, C.; Spegazzini, N.; Dasari, R.R.; Barman, I. Noninvasive monitoring of blood glucose with Raman spectroscopy. Accounts Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingari, N.C.; Barman, I.; Singh, G.P.; Kang, J.W.; Dasari, R.R.; Feld, M.S. Investigation of the specificity of Raman spectroscopy in non-invasive blood glucose measurements. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 400, 2871–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzstein, G.; Ozcan, A.; Gigan, S.; Fan, S.; Englund, D.; Soljačić, M.; Denz, C.; Miller, D.A.B.; Psaltis, D. Inference in artificial intelligence with deep optics and photonics. Nature 2020, 588, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Sheng, X.; Cao, J.; Jia, H.; Gao, W.; Gu, S.; Wang, X.; Chu, P.K.; Lou, S. Machine-learning-assisted omnidirectional bending sensor based on a cascaded asymmetric dual-core PCF sensor. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 4929–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, R.; Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Z. Fish quality evaluation by sensor and machine learning: A mechanistic review. Food Control 2022, 137, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayassi, R.; Triki, A.; Crespi, N.; Minerva, R.; Laye, M. Survey on the use of machine learning for quality of transmission estimation in optical transport networks. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 5803–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pian, F.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Shan, P.; Li, Z.; Ma, Z. A shallow convolutional neural network with elastic nets for blood glucose quantitative analysis using Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 264, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pian, F.; Wang, M.; Song, S.; Li, Z.; Shan, P.; Ma, Z. Quantitative analysis of Raman spectra for glucose concentration in human blood using Gramian angular field and convolutional neural network. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 275, 121189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gou, C.; Duan, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, F.-Y. Generative adversarial networks: Introduction and outlook. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2017, 4, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Viveros, N.; Castro-Ramos, J.; Gómez-Gil, P.; Cerecedo-Núñez, H.H.; Gutiérrez-Delgado, F.; Torres-Rasgado, E.; Pérez-Fuentes, R.; Flores-Guerrero, J.L. Quantification of glycated hemoglobin and glucose in vivo using Raman spectroscopy and artificial neural networks. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3537–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, B.; Wang, L.; Zu, C.; Lalush, D.S.; Lin, W.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Shen, D.; Zhou, L. 3D conditional generative adversarial networks for high-quality PET image estimation at low dose. NeuroImage 2018, 174, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).