Abstract

An innovative dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction technique utilizing a solid dispersion was established for the quantification of triazine herbicides in environmental water samples. Naturally derived monoterpenoids were utilized as eco-friendly extraction solvents, markedly decreasing the reliance on harmful extraction solvents. A small amount of Pop Rocks candy served as a solid dispersant; the rapid release of carbon dioxide promoted the generation of fine monoterpenoid droplets, effectively replacing conventional hazardous liquid dispersants. The solidification technique of floating organic droplets facilitated the effective phase separation of monoterpenoids from aqueous samples, thereby obviating the need for centrifugation. Triazine herbicides exhibited good linearity within the concentration range of 0.008–0.8 mg/L with correlation coefficients above 0.99 and detection limits of 0.002 mg/L. The proposed method was effectively implemented on surface and groundwater samples, attaining recoveries between 86.4% and 98.0%. Molecular docking analysis suggests a spontaneous binding between the monoterpenoid and triazine herbicides. A comprehensive green assessment utilizing two evaluation tools confirmed the excellent environmental performance of the method. This technique offers superior greenness and simplicity compared with conventional techniques, demonstrating strong potential for application in the environmental analysis of pesticide residues.

1. Introduction

Pesticides are essential in modern agricultural systems, as they protect crops to ensure stable yields and food security [1]. Triazine herbicides are one of the most widely utilized groups globally, inhibiting photosynthesis in leaves, particularly impeding the photosystem [2]. These compounds are persistent in the environment, presenting significant risks to aquatic ecosystems and human health [3]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that triazine herbicides are hazardous to aquatic organisms even at trace concentrations [4]. Therefore, the precise and sensitive quantification of triazine herbicide residues in environmental water samples is crucial for environmental monitoring and risk assessment.

Sample pretreatment is essential in pesticide residue analysis, as it directly affects the accuracy, sensitivity, and reliability of the analytical results. Among several pretreatment strategies, liquid-phase microextraction (LPME) has garnered significant interest due to its benefits of reduced solvent consumption and enhanced enrichment efficiency [5]. Dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME) is the most extensively utilized approach [6]. In DLLME, a small volume of an extractant and a dispersant is introduced into an aqueous sample, forming a cloudy solution in which fine extractant droplets are dispersed throughout the sample matrix. This wide interfacial area significantly enhances mass transfer, facilitating rapid extraction within a short equilibrium time [7]. The DLLME procedure enables a markedly higher sample throughput compared with classical liquid–liquid extraction or solid–phase extraction, owing to its short extraction time and minimal handling requirements. Despite its simplicity and efficiency, DLLME is still plagued by several drawbacks. First, the extractants commonly utilized, including chloroform and dichloromethane, are often toxic and non-biodegradable, which limits the greenness of the method [6]. Second, DLLME requires a relatively large amount of dispersant, including acetonitrile or methanol, which are not environmentally benign [8]. Third, the retrieval of the dispersed extractant is laborious, as it typically requires time-consuming and energy-intensive centrifugation [9]. Consequently, advancing more environmentally friendly and convenient alternatives to conventional DLLME has become an important research direction.

Monoterpenoids are an essential class of natural organic compounds derived from isoprene units. As secondary metabolites, they are extensively found in diverse plant tissues, particularly in essential oils [10]. Because of their renewable origin, comparatively low cost, and favorable hydrophobic characteristics [11], monoterpenoids have recently garnered significant interest as emerging solvents in sustainable chemistry. Menthol, linalool, and terpineol are representative monoterpenoids with varied physicochemical properties and applications. Current research in green analytical chemistry predominantly examines the application of monoterpenoids in formulating deep eutectic solvents (DES) to lower the melting point of monoterpenoids [12,13]. The direct application of monoterpenoids as extractants, without the need for DES preparation, is of crucial significance for streamlining procedures and enhancing the efficiency of the analytical process.

In DLLME, the extractant requires the assistance of a dispersant to achieve uniform dispersion and adequate contact with the sample. Most conventional approaches utilize liquid dispersants, including acetonitrile or methanol, which exhibit certain toxicity. Furthermore, the volume of liquid dispersant is often approximately 1 mL [14]. Consequently, although the extractant is utilized at the microliter scale, the toxic dispersant may exist at the milliliter scale, significantly compromising the method’s environmental sustainability. Conversely, solid dispersants, including sugar cubes, have received little attention [15,16]. The extractant is released from the solid dispersant’s surface, facilitating comprehensive interaction with the sample. In contrast to liquid dispersants, which are toxic and may enhance the solubility of target analytes in the sample, thereby reducing extraction efficiency [17], sugar cubes are environmentally friendly and can reduce the solubility of analytes in the aqueous phase through the sugar-out effect [18], thereby improving extraction performance. A unique solid dispersion, Pop Rocks candy, emits a substantial quantity of high-pressure carbon dioxide when it reacts with the aqueous sample, hence enhancing mass transfer and extraction efficiency. Consequently, DLLME with solid dispersants, specifically Pop Rocks candies, has clear advantages over conventional liquid dispersant-based DLLME regarding solvent consumption, method greenness, and extraction efficiency. Compared with effervescent reactions, Pop Rocks candy can rapidly release carbon dioxide without involving a chemical reaction, offering an advantage in extraction kinetics. Moreover, as no acid is required, it is particularly suitable for extracting compounds that are unstable under acidic conditions. Although solid dispersant-based DLLME has been reported previously [15,16], its integration with novel green extraction solvents such as monoterpenoids has not been explored. This combination offers the potential to further enhance the environmental friendliness of existing microextraction techniques.

The separation of the extractant is a critical issue in DLLME. In single-drop microextraction and hollow-fiber LPME, the extractant can be easily retrieved by retracting the droplet into a microsyringe or by extracting the solvent retained within the fiber membrane [19]. In DLLME, phase separation generally requires a time-consuming and energy-intensive centrifugation process. The solidification of a floating organic droplet (SFOD) technique utilizes a simple solid–liquid separation process, thus eliminating the need for centrifugation [20]. After extraction, the solvents with low density and low melting points float on the samples and can be solidified simply by cooling [21]. By selecting monoterpenoids with melting points marginally exceeding room temperature, the molten monoterpenoids can solidify as extractants under ambient conditions. Compared with the conventional DLLME-SFOD method, that require low-temperature cooling for solidification [22], Monoterpenoids-based DLLME-SFOD method prevents melting and loss during collection at room temperature. Consequently, the separation approach significantly simplifies the separation process, diminishes energy consumption, and improves the extractant collection in DLLME.

This study aimed to develop a sustainable and efficient LPME technique for quantifying triazine herbicides in environmental water samples. Herein, monoterpenoid menthol was introduced as a novel bio-based and environmentally friendly extractant in DLLME, whereas Pop Rocks candy was utilized as a solid dispersant to replace toxic liquid dispersants. The extractant phase was effectively obtained using the SFOD technique, eliminating the need for centrifugation. The main experimental parameters affecting the extraction efficacy, including the extractant, dispersant, temperature, sample, salt concentration, and pH, were systematically optimized. The proposed solid dispersant-based DLLME (SD–DLLME), combined with high-performance liquid chromatography equipped with an ultraviolet detector (HPLC–UV), was effectively utilized for determining triazine herbicides in environmental water samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

Commercial simazine (98%), atrazine (98%), terbuthylazine (99%), menthol, linalool, and terpineol were acquired from J&K Chemicals (Beijing, China). Pop Rocks candy was obtained from Baida Food Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China). Water samples were collected from the Tarim River and Bosten Lake (Tarim, China), transported to the laboratory under refrigerated conditions, and stored at 4 °C in the dark. Prior to analysis, the samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane to remove suspended particulate matter.

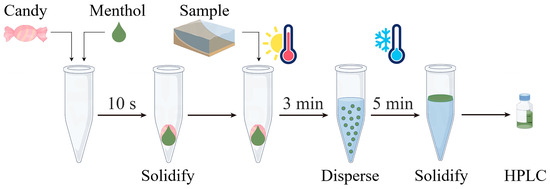

2.2. Extraction Processes

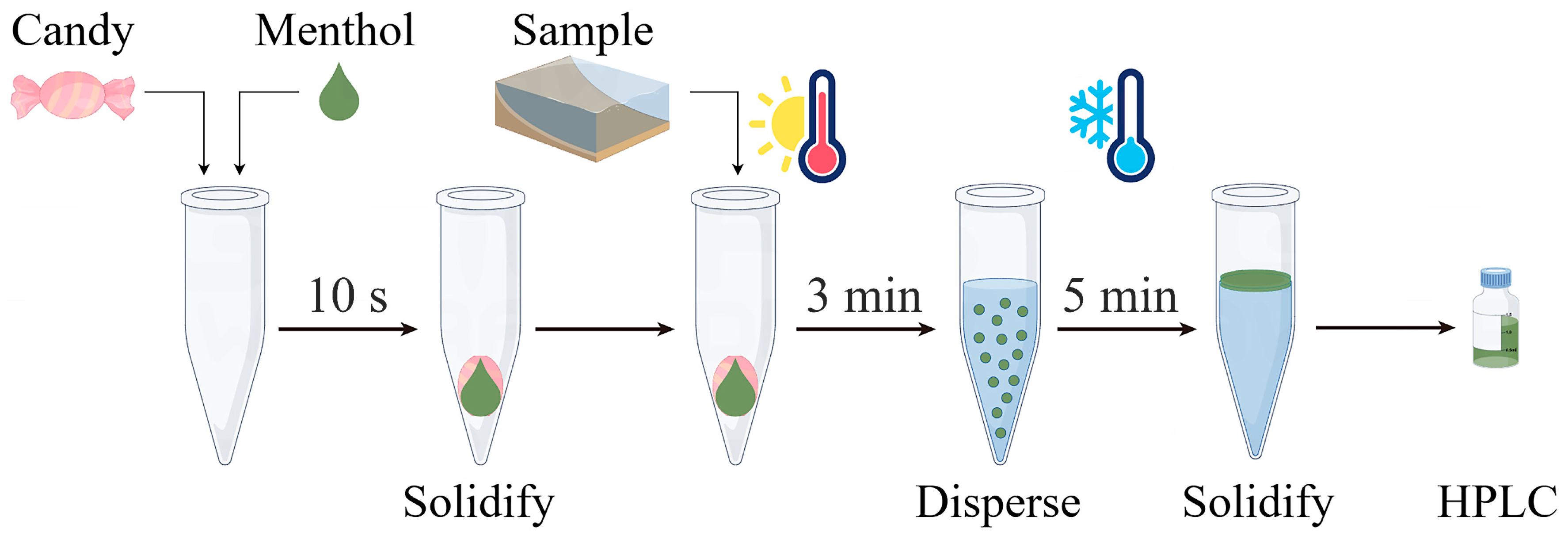

We sequentially added 300 mg of Pop Rocks candy (used as a solid dispersant) into a 10 mL centrifuge tube, followed by 200 µL of menthol (used as the extractant) whose temperature was controlled at 30 °C using a thermostatic water bath. Within 10 s, the menthol solidified on the surface of the Pop Rocks candy. Subsequently, 5 mL of the sample, preheated to 70 °C in a thermostatic water bath, was introduced into the centrifuge tube. Upon contact, molten menthol was released from the Pop Rocks candy surface within 3 min, rapidly interacting with the sample alongside the forceful emission of carbon dioxide. The centrifuge tube was subsequently placed in a −20 °C freezer for 5 min to accelerate the solidification of menthol in the upper layer. The solidified menthol was subsequently transferred into an autosampler vial and diluted with 50 µL of methanol before HPLC analysis. Figure 1 depicts the schematic diagram.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the solid dispersant-based DLLME (SD–DLLME) procedure.

2.3. Optimization of Extraction Variables

Preliminary experiments were conducted to determine suitable ranges for the extraction variables. While single-factor optimization was employed, potential interactions between variables were considered. The examined variables comprised the type and volume of monoterpenoid, the amount of Pop Rocks candy, the temperature and volume of the sample, the amount of sodium chloride, and the pH value. All optimization experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Statistical comparisons were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with differences considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

2.4. HPLC–UV Detection

Triazine herbicides were examined utilizing an Agilent 1260 HPLC–UV. Separation was accomplished using an Eclipse Plus C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm). The injection volume was 10 µL, and the column temperature was maintained at 35 °C. An isocratic elution was conducted utilizing a mobile phase comprising 60% acetonitrile and 40% water at a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1. Under these conditions, the retention times of simazine, atrazine, and terbuthylazine were 4.9, 6.2, and 8.6 min, respectively. Based on the absorption characteristics, the detection wavelength was set at 220 nm.

2.5. Enrichment Factor (EF) and Extraction Recovery (ER) Calculation

EF was calculated as follows:

where Cextractant represents the concentration in the extractant, and Csample represents the concentration in the sample.

ER was calculated as follows:

where Cfound represents the detected concentration in spiked samples, Creal represents the detected concentration in unspiked samples, and Cadded represents the concentration added in samples.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of Extraction Variables

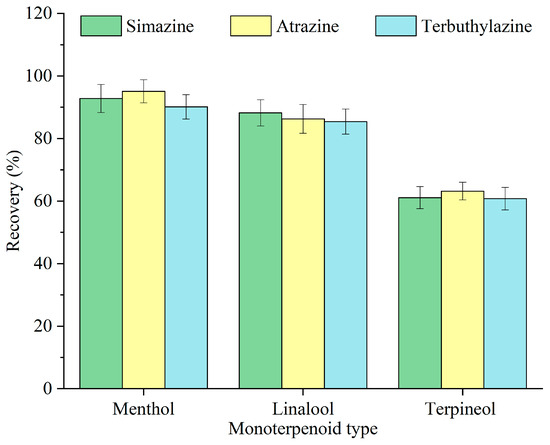

3.1.1. Monoterpenoid Type

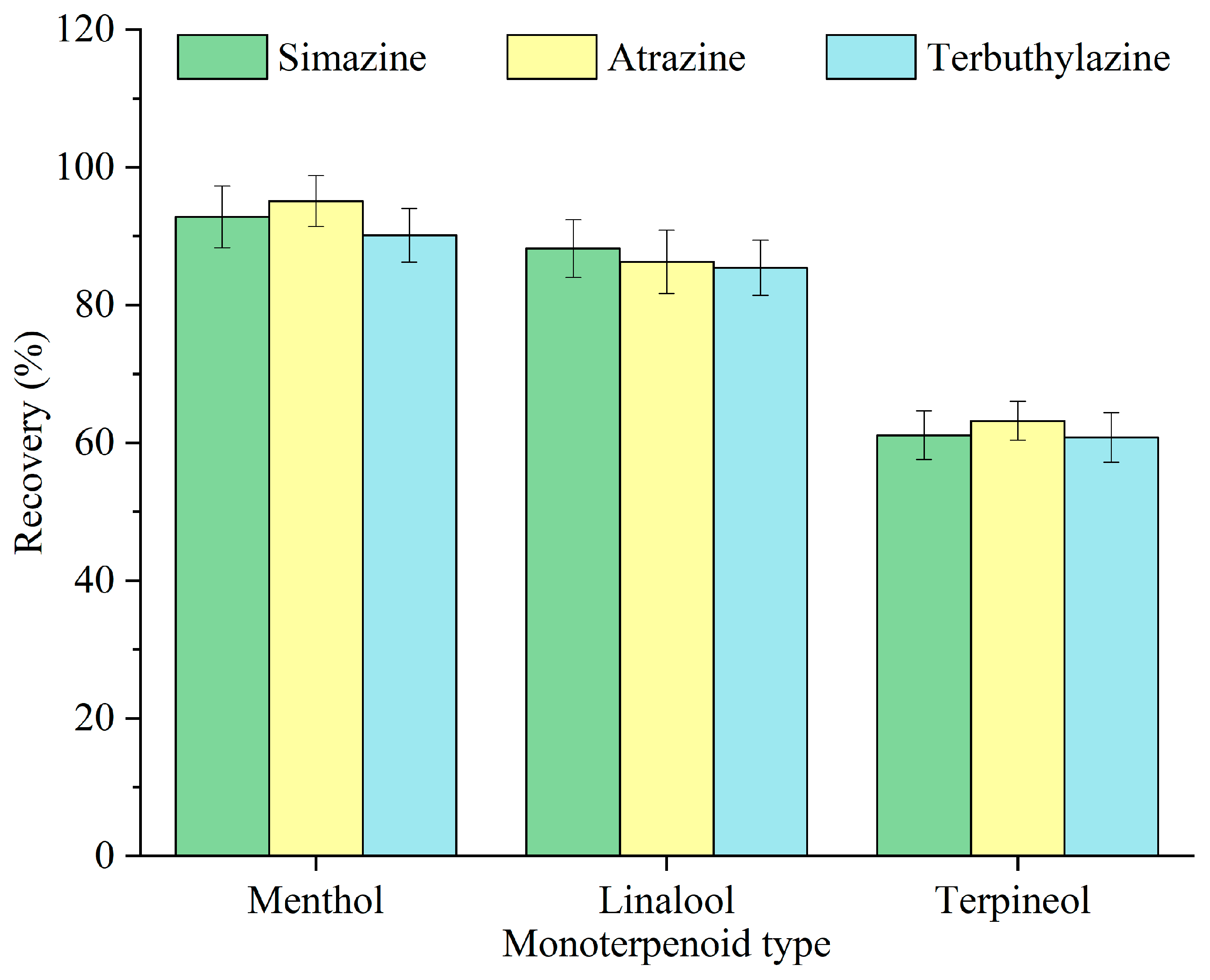

The structure and physicochemical properties of extractants are essential in determining the extraction efficiency of target analytes [23]. The impact of various monoterpenoids—menthol, linalool, and terpineol—on the recovery of triazine herbicides was investigated, and the findings are illustrated in Figure 2. Among the three monoterpenoids, menthol exhibited the highest recovery. All three monoterpenoids contain a hydroxyl group; however, menthol possesses a reduced polarity and increased hydrophobicity, hence facilitating its affinity toward the hydrophobic triazine herbicides. Accordingly, menthol was selected as the optimal monoterpenoid for subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

Optimization of the monoterpenoid type.

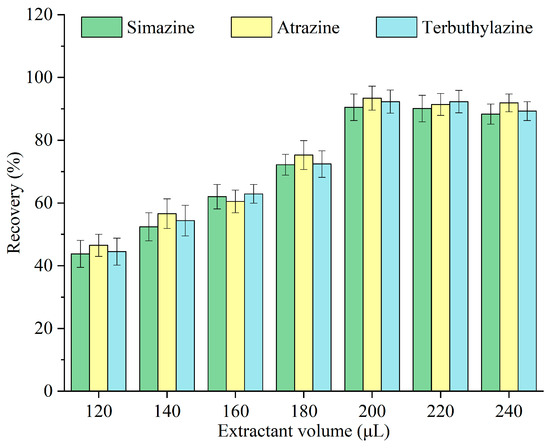

3.1.2. Monoterpenoid Volume

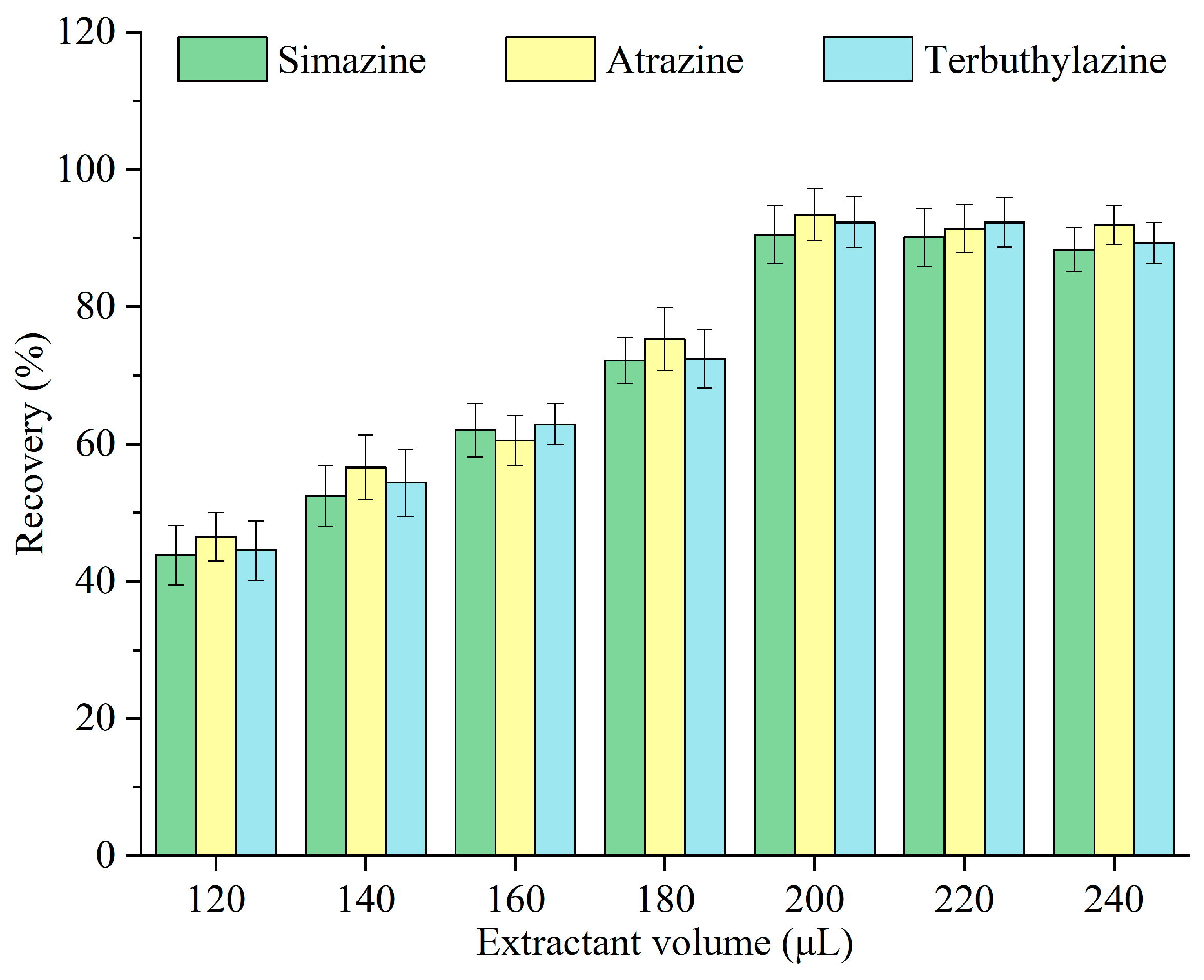

Monoterpenoids were emitted from the surface of Pop Rocks candy and dispersed throughout the sample. An insufficient quantity of monoterpenoid fails to facilitate effective extraction, whereas an excessive amount hinders the interaction between the Pop Rocks candy and the sample, thereby affecting the carbon dioxide release rate and the assisted dispersion effect. The impact of different volumes of monoterpenoids—120, 140, 160, 180, 200, 220, and 240 μL—on the recovery of triazine herbicides was investigated, and the results are illustrated in Figure 3. The recovery escalated with the monoterpenoid volume, peaking at 200 μL, after which it remained constant. When the monoterpenoid volume was insufficient, the contact area with the sample was limited [24]. After the extraction equilibrium was reached, supplementary monoterpenoid diluted the triazine herbicides in the extractant. Consequently, 200 μL was selected as the optimal volume of monoterpenoids for subsequent experiments.

Figure 3.

Optimization of the monoterpenoid volume.

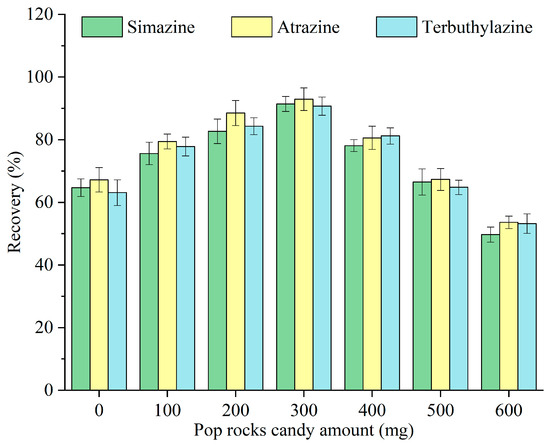

3.1.3. Pop Rocks Candy Amount

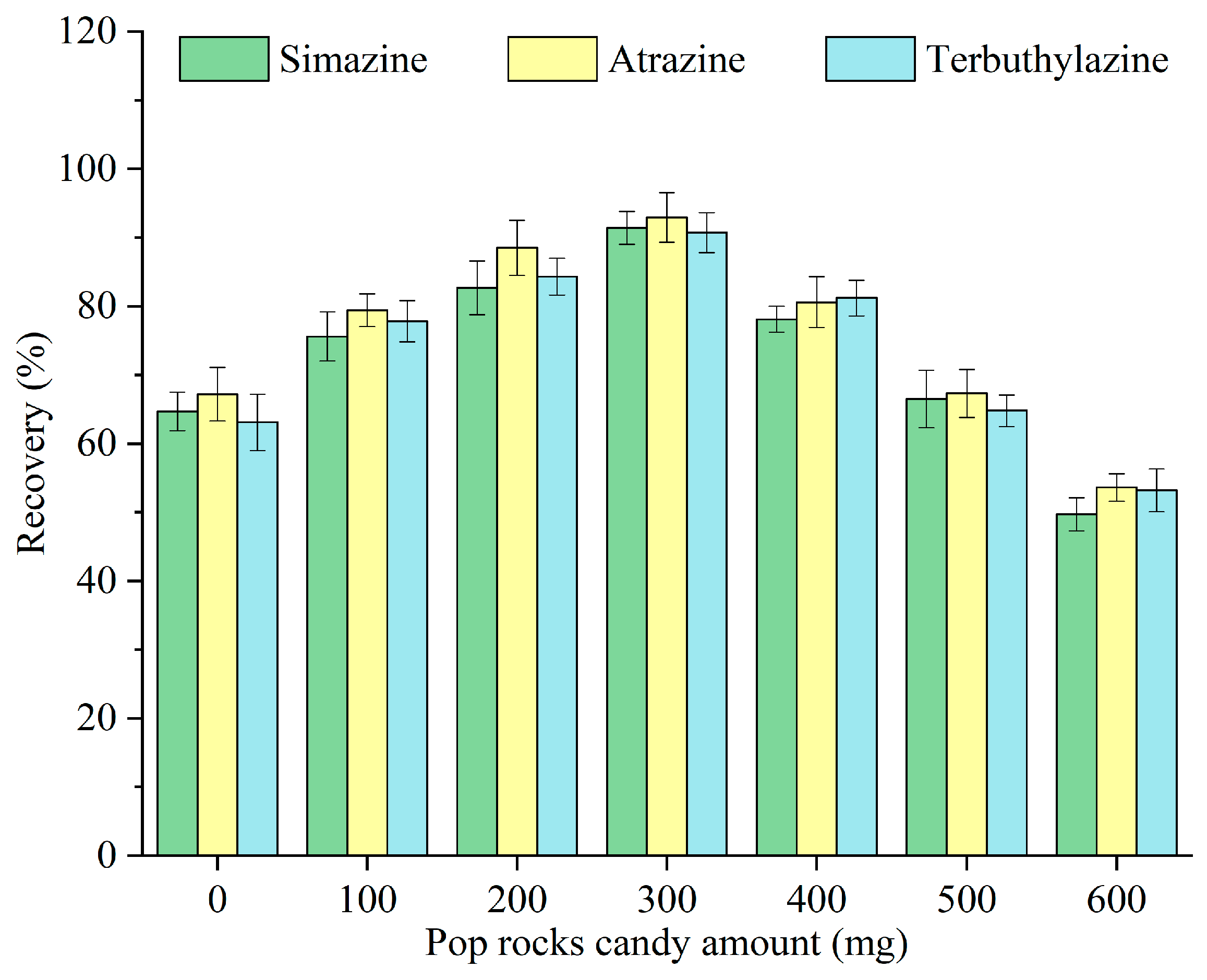

Pop Rocks candy acted as a solid dispersant that, through dissolution, carbon dioxide release, and sugar-out effects, synergistically enhanced the dispersion of monoterpenoids in the sample. The popping effect arises from pressurized carbon dioxide gas encapsulated within the sugar matrix at approximately 600 psi. The sugar mass, rather than its type, was the primary variable influencing the dispersion efficiency [25]. The impact of different amounts of Pop Rocks candy—0, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, and 600 mg—on the recovery of triazine herbicides was examined, and the results are illustrated in Figure 4. The recovery increased with the amount of Pop Rocks candy, peaking at 300 mg, and subsequently decreased. Although sugars facilitate dispersion through multiple synergistic mechanisms, excessive sugar increases the sample’s viscosity [15], thereby reducing mass transfer. Hence, 300 mg was selected as the optimal amount of Pop Rocks candy for subsequent experiments.

Figure 4.

Optimization of the Pop Rocks candy amount.

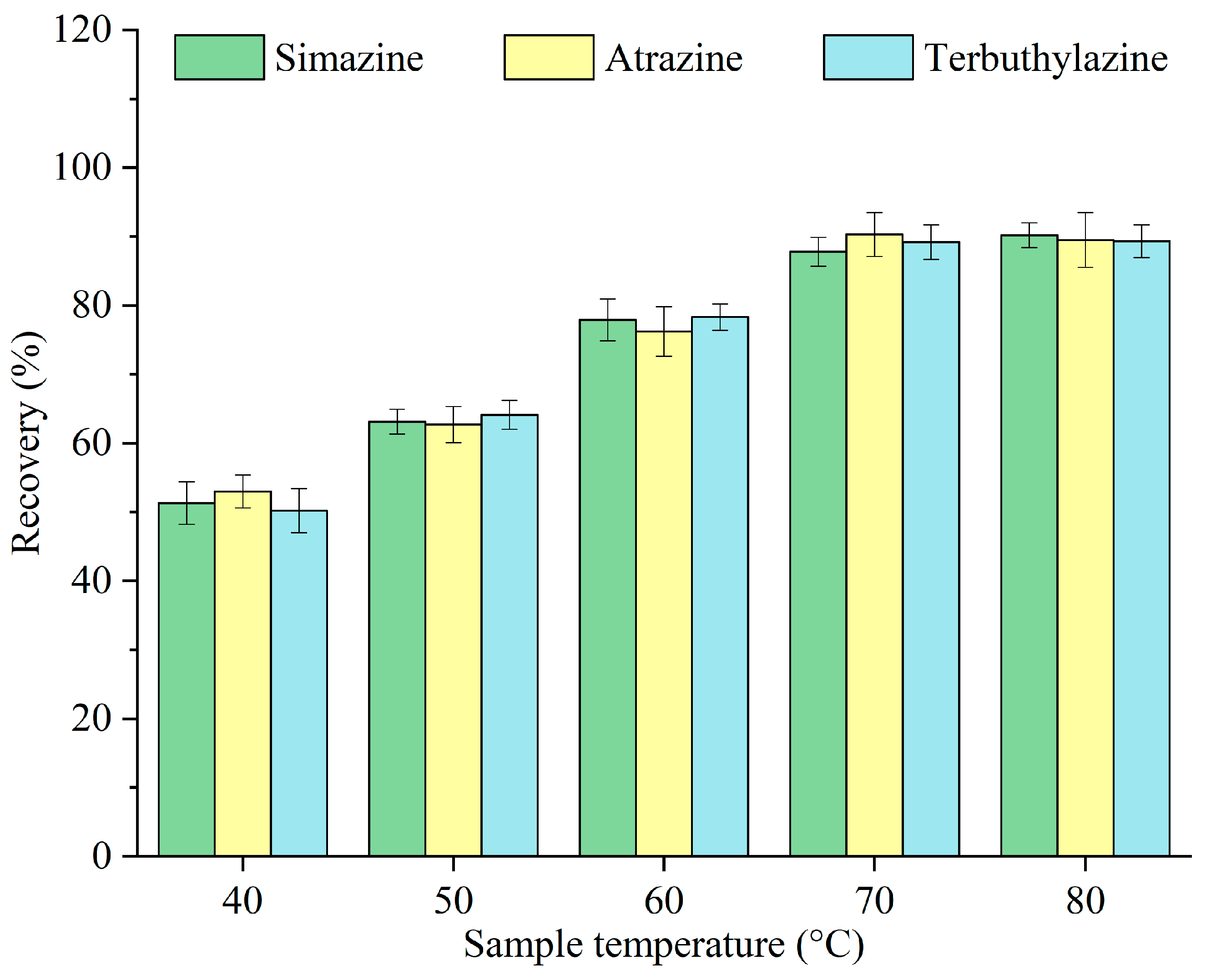

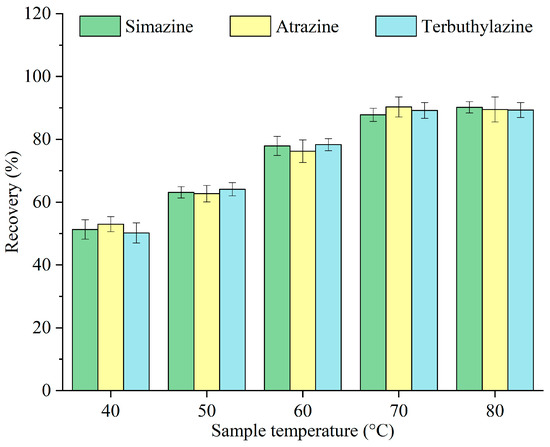

3.1.4. Sample Temperature

Given that menthol has a melting point of 34 °C, the sample temperature must exceed this threshold to facilitate its rapid melting. However, excessively high temperatures can extend the solidification and collection of menthol post-extraction. The effects of various temperatures of the sample—40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 °C—on the recovery of triazine herbicides were investigated, and the results are displayed in Figure 5. The recovery increased with the sample temperature, peaking at 70 °C, and subsequently remained nearly unchanged. This improvement can be ascribed to faster melting of menthol, the solubility of sugar, and the accelerated release of carbon dioxide at elevated temperatures [15]. Consequently, 70 °C was selected as the optimal sample temperature for subsequent experiments.

Figure 5.

Optimization of the sample temperature.

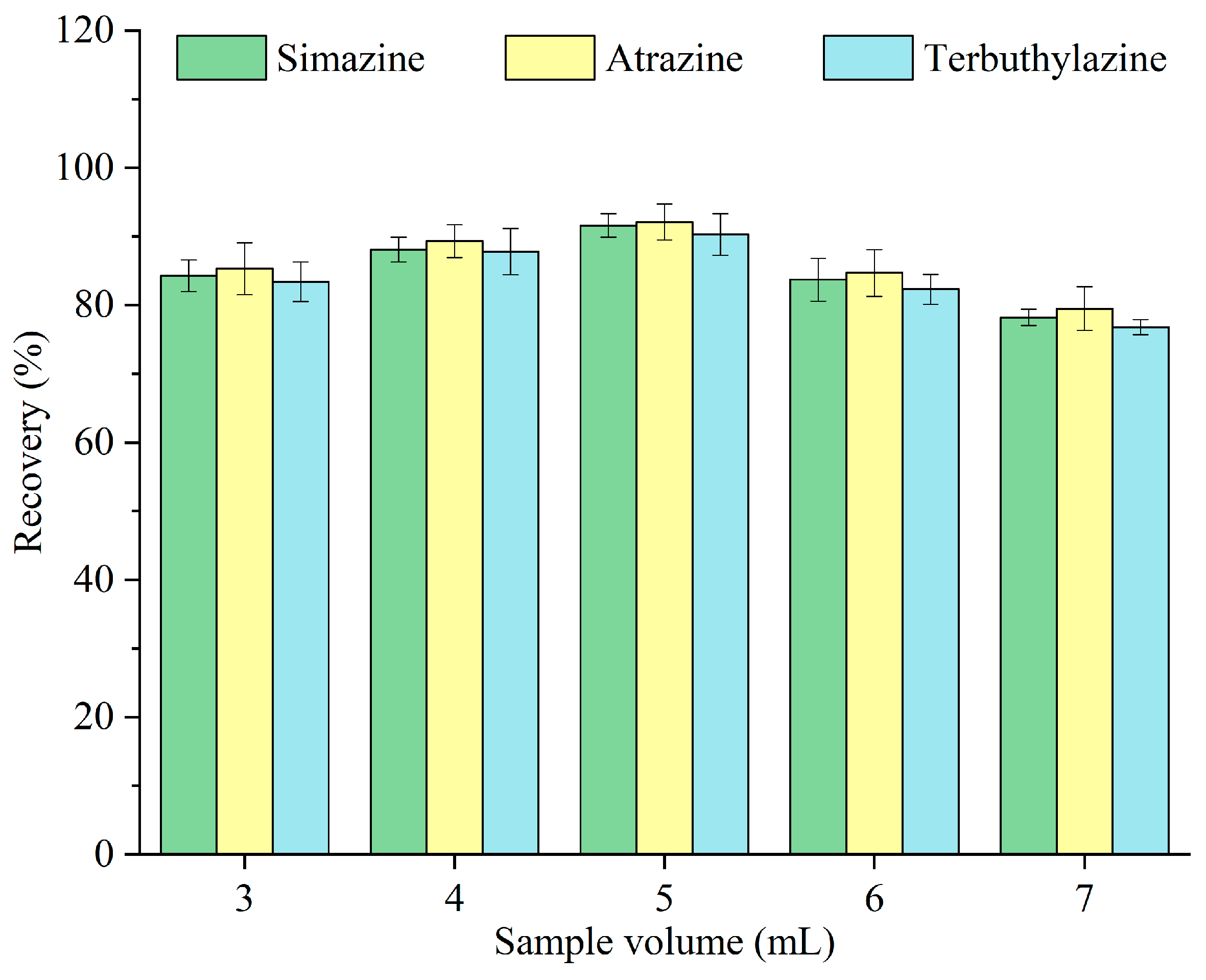

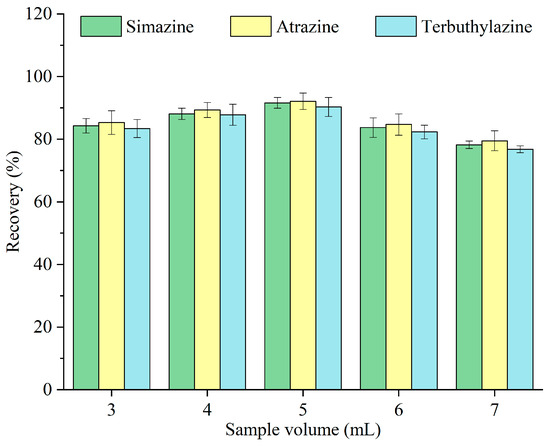

3.1.5. Sample Volume

To achieve a higher enrichment factor, a larger sample volume is typically desirable; however, this may result in diminished extraction efficiency. The effects of different volumes of sample—3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 mL—on the recovery of triazine herbicides were investigated, and the results are depicted in Figure 6. The recovery was improved with increasing sample volume and peaked at 5 mL and subsequently declined. When the sample volume was minimal, more extractant droplets adhered to the tube wall due to the vigorous release of carbon dioxide, complicating their collection. Conversely, at larger sample volumes, a larger fraction of the extractant was dissolved in the aqueous phase [26], leading to extractant loss and decreased recovery. Therefore, 5 mL was designated as the optimal sample volume for subsequent experiments.

Figure 6.

Optimization of the sample volume.

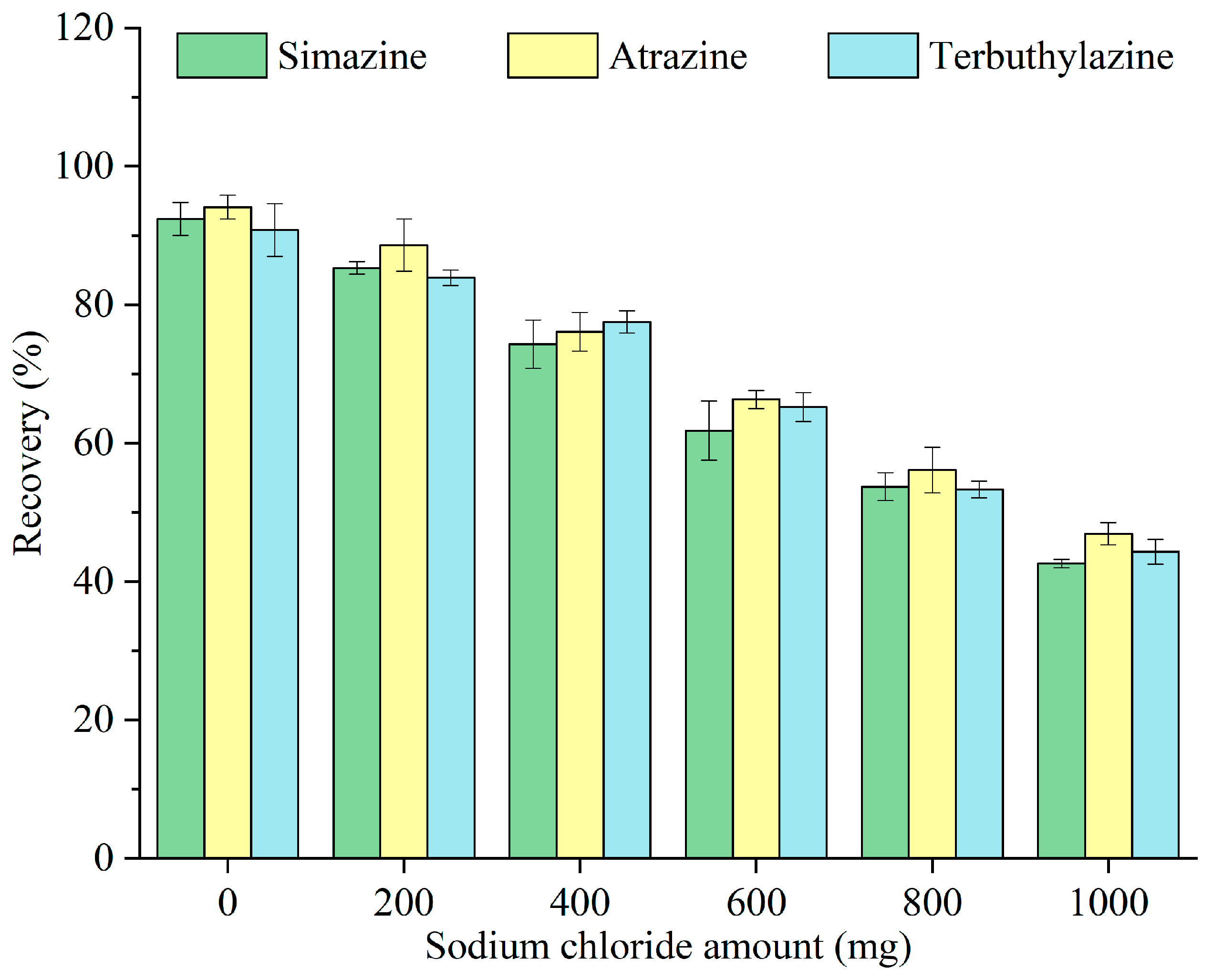

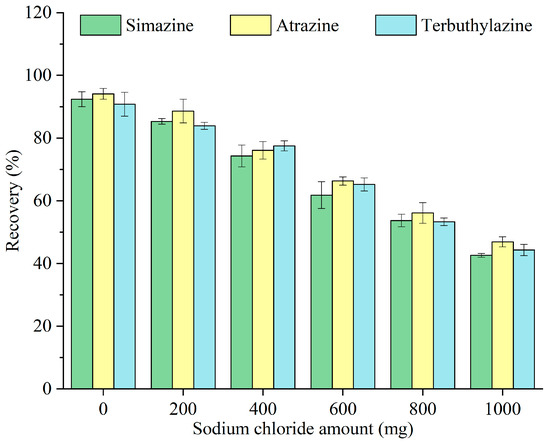

3.1.6. Sodium Chloride Amount

Salt addition before extraction can influence the solubility of target analytes within the sample matrix, hence impacting the extraction effectiveness. The impacts of different concentrations of sodium chloride (0, 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 mg) on the recovery of triazine herbicides were examined, and the results are illustrated in Figure 7. The recovery decreased with increasing sodium chloride amount. As Pop Rocks candy had already acted as a sugar-out reagent, the addition of sodium chloride resulted in no further enhancement of the extraction efficiency. Its presence increased the ion strength and viscosity of the sample matrix and hindered mass transfer between the aqueous and organic phases [27]. As a result, any potential positive contribution from the ionic strength of NaCl was largely offset by these negative effects, leading to a reduced recovery. Thus, no salt was added before extraction in subsequent experiments.

Figure 7.

Optimization of the sodium chloride amount.

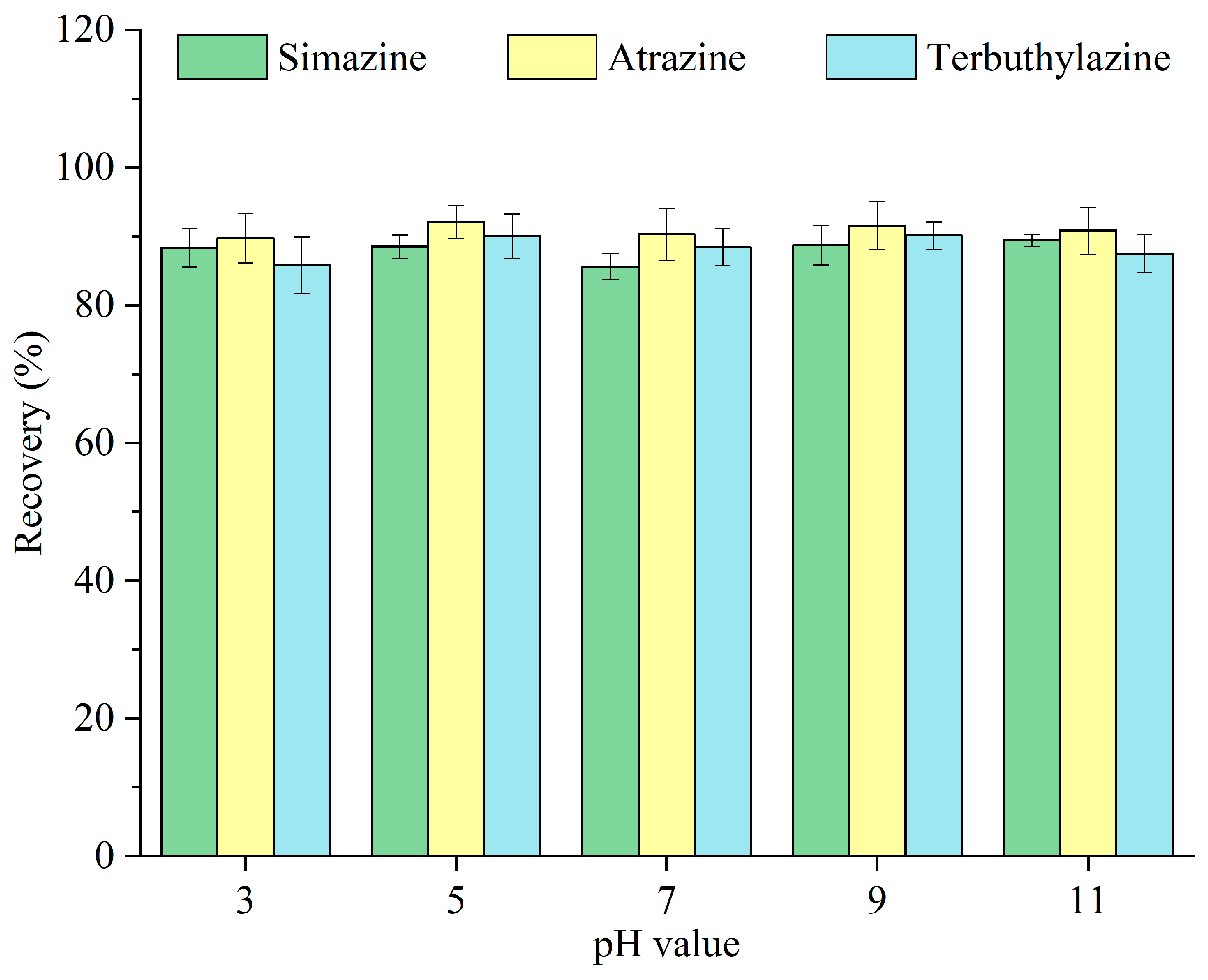

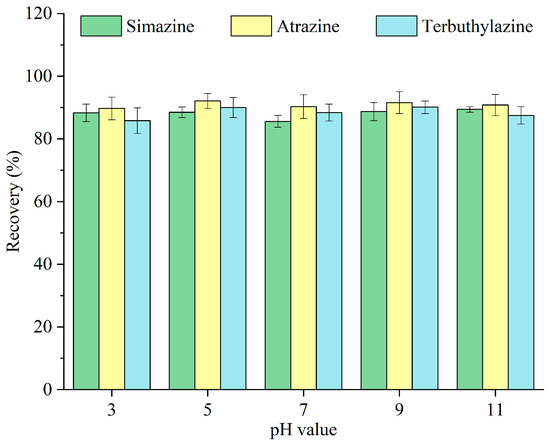

3.1.7. pH Value

The chemical form of analytes can fluctuate with pH levels. The impacts of varying pH values—3, 5, 7, 9, and 11—on the recovery of triazine herbicides were examined, and the results are depicted in Figure 8. The recoveries of triazine herbicides remained very stable across the tested pH range. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Pesticide Properties Database indicates that the dissociation constants (pKa) of simazine, atrazine, and terbuthylazine at 25 °C are 1.62, 1.70, and 1.90, respectively. Triazine herbicides may predominantly exist in their molecular form in aqueous solutions [28]. Therefore, water samples were immediately extracted without preliminary pH modification in the following experiments.

Figure 8.

Optimization of the pH value.

3.2. Method Assessment

Table 1 presents the analytical performance of the proposed method, which was evaluated based on the calibration curve, coefficient of determination (R2), limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ), and relative standard deviation (RSD). Calibration curves were generated by plotting the peak area against the five mass concentrations (0.008, 0.04, 0.08, 0.4, and 0.8 mg/L). Excellent linearity was attained within the range of 0.008–0.8 mg/L, with R2 exceeding 0.998. The LOD and LOQ were determined in the matrix after extraction and were found to be 0.002 and 0.008 mg/L, respectively. The signal-to-noise ratios of 3 and 10 were used to define LOD and LOQ, with noise estimated from blank samples. Precision was evaluated with three replicate analyses, yielding intra-day RSDs of 2.0–5.6% and inter-day RSDs of 3.1–7.4%. These results indicate that the approach has satisfactory linearity, sensitivity, and repeatability.

Table 1.

Analytical performance of the SD–DLLME–HPLC–UV method.

3.3. Analysis of Triazine Herbicides

To assess the accuracy and precision of the proposed method, the optimized extraction and detection procedures were employed to quantify triazine herbicide residues in various real water samples, including river, lake, and well waters. The concentrations of triazine herbicides in samples were below the LODs. Consequently, spiking experiments were performed at three concentration levels (0.008, 0.08, and 0.8 mg L−1) to further validate the analytical performance. Table 2 indicates that the mean recoveries ranged from 86.4% to 98.0%, with RSDs between 0.9% and 6.6%. These results illustrate the excellent precision, reliability, and usefulness of the developed approach for trace-level detection of triazine herbicides in environmental water matrices.

Table 2.

Analysis of triazine herbicides in environmental water samples.

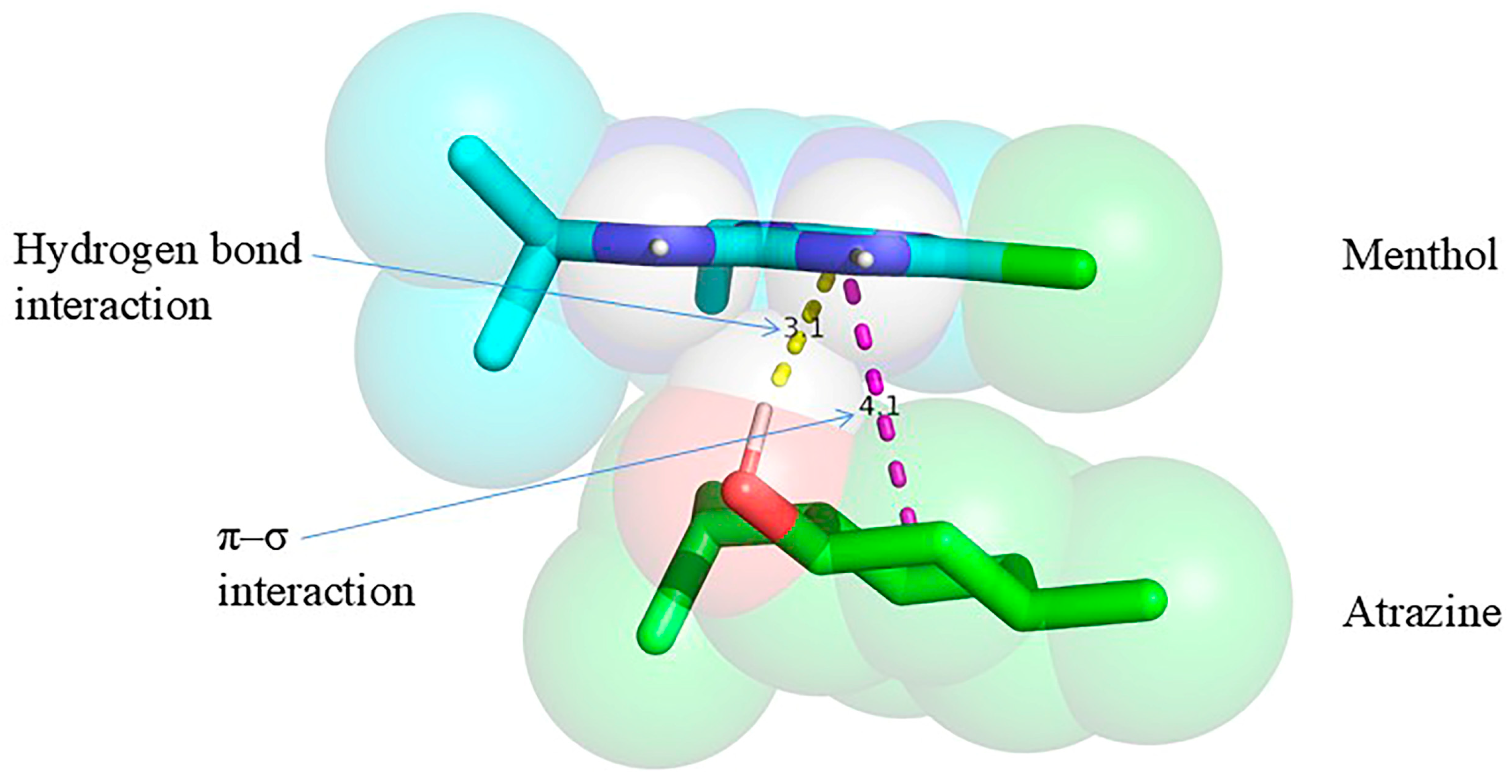

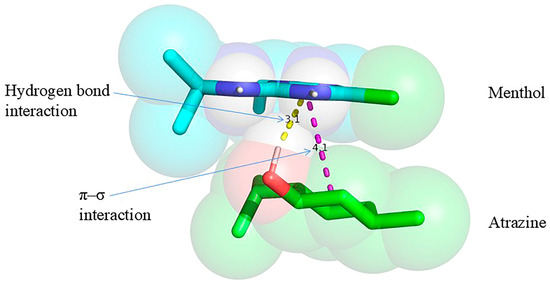

3.4. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was conducted using menthol as the extractant and atrazine as the target herbicide. The low-energy conformations of menthol and atrazine were initially optimized utilizing AutoDock Vina 1.1.2, subsequently followed by docking simulations conducted in PyRx to calculate the binding energy. The docking results were visualized and analyzed utilizing PyMOL 2.3. Figure 9 depicts the hydrogen bond formation between the hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group in menthol and the nitrogen atom on the triazine ring of atrazine, with an interaction distance of 3.1 Å. Moreover, a weak π–σ interaction was noted. The calculated binding energy between menthol and atrazine was −1.8 kcal mol−1, signifying a spontaneous interaction (as negative binding energy denotes spontaneous binding [29]). While the relatively low binding energy may contribute to some extent, the observed extraction efficiency is more likely influenced by general physicochemical properties such as hydrophobicity and partitioning behavior.

Figure 9.

Molecular docking analysis of menthol with atrazine.

3.5. Comparison of the SD–DLLME–HPLC–UV Method with Reported Approaches

The proposed method was evaluated against previously reported approaches [30,31,32,33] regarding solvents, reagents, instrumentation, LOQs, and recoveries (Table 3). The present method requires 200 μL of the green solvent menthol, thereby avoiding the need for large quantities of toxic organic solvents (methanol, dichloromethane, and acetonitrile) and solvents that require laborious preparation (DES). Moreover, 300 mg of Pop Rocks candy was utilized as a solid dispersant to enhance extraction, eliminating the need for large amounts of salts (sodium chloride, calcium oxide) or substances requiring complex preparation procedures (biochar and fibers). Furthermore, compared to other analytical instruments (HPLC-DAD, GC–FID, and GC–MS), the proposed method achieved satisfactory LOQs and recoveries. This method offers clear benefits of greenness, simplicity, and operational efficiency.

Table 3.

Comparison of SD–DLLME–HPLC–UV with reported microextraction methods for the determination of triazine herbicides.

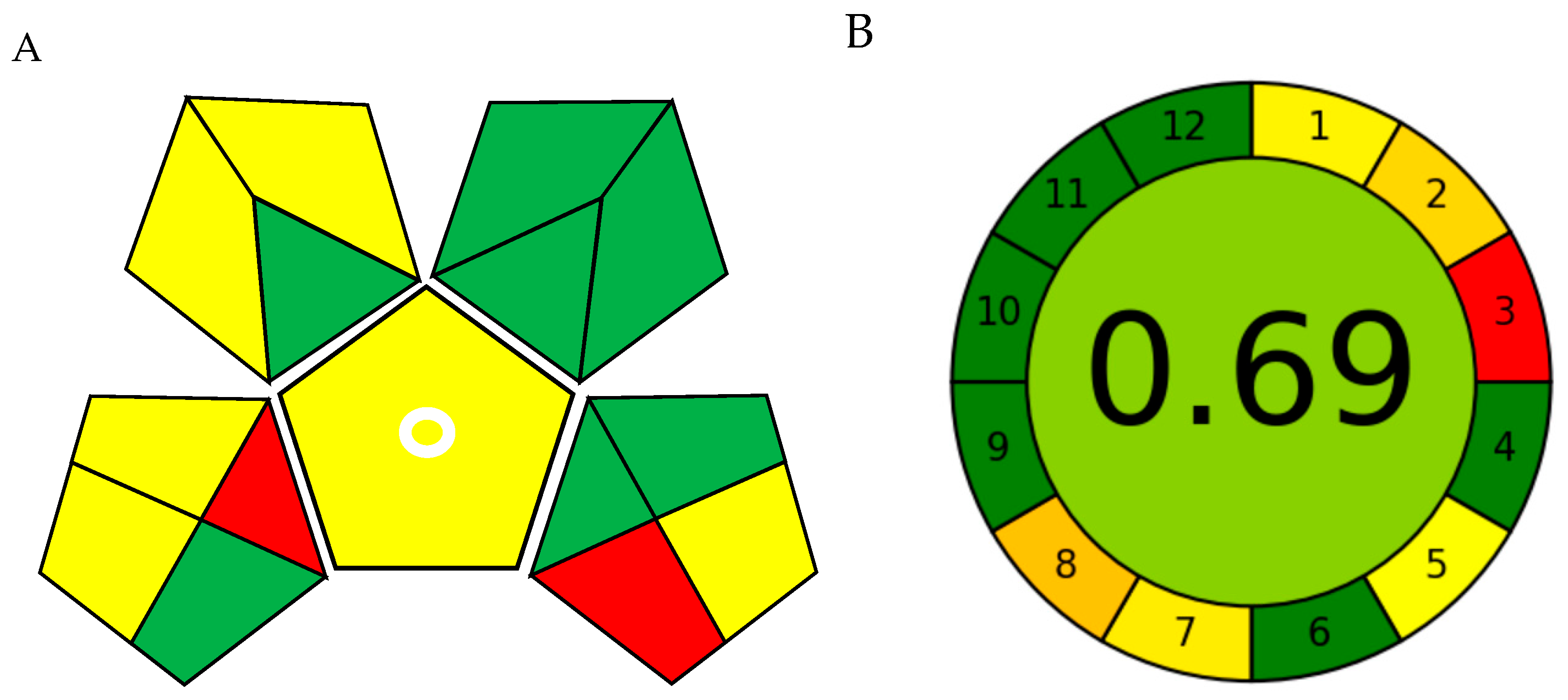

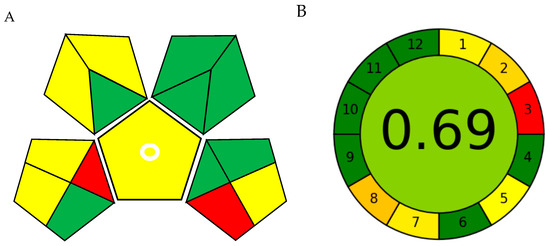

3.6. Greenness Evaluation

Green analytical chemistry (GAC), based on its twelve foundational principles, provides a systematic framework for evaluating the environmental sustainability of analytical methodologies [34]. This study included two widely recognized greenness assessment tools to comprehensively evaluate the ecological performance of the proposed method.

The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) offers a pictorial representation of environmental impact, featuring a pictogram with seven green, six yellow, and two red zones (Figure 10A and Table 4). The prevalence of green zones indicates the method’s low overall environmental burden, whereas the few yellow and red areas are primarily associated with sample preparation and waste management stages.

Figure 10.

Greenness evaluation of the SD–DLLME–HPLC–UV procedure. (A) Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) and (B) Analytical GREEnness (AGREE).

Table 4.

Systematic GAPI evaluation of the SD–DLLME–HPLC–UV procedure.

The Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) assessment yielded a comprehensive score of 0.69/1 (Figure 10B and Table 5), represented as a clock-shaped figure that effectively visualizes proficiency across the twelve GAC principles. This result underscores the method’s strengths in energy conservation and process miniaturization.

Table 5.

Systematic AGREE evaluation of the SD–DLLME–HPLC–UV procedure.

The consistently high scores obtained from two greenness assessment tools collectively indicate that the developed method is an environmentally sustainable and resource-efficient analytical method.

4. Conclusions

This study developed a simple and eco-friendly solid dispersant-based DLLME method, integrated with HPLC–UV for quantifying triazine herbicides in environmental water samples, including river, lake, and well water. The suggested solid dispersant-assisted strategy provides an efficient and eco-friendly alternative for conventional toxic liquid dispersants, promoting safer and more sustainable analytical methodologies. Menthol was effectively utilized as a bio-derived, environmentally friendly extractant, exhibiting excellent performance in the extraction of pesticide residues. Their relatively high melting points facilitated simple and efficient collection through solid–liquid separation. In the analysis of real samples, all target triazine herbicides were below the limits of detection. Therefore, the applicability of the proposed method was evaluated using spike–recovery experiments, which yielded satisfactory recoveries ranging from 86.4% to 98.0%, with RSDs between 0.9% and 6.6%. Because of its simplicity, efficiency, and environmental compatibility, this solid dispersant-based microextraction method offers great promise for broader application in the analysis and monitoring of pesticide residues in environmental water samples. Since the extraction procedure is conducted at 70 °C, the applicability of this method may be limited for thermolabile pesticides and samples. Future studies will focus on preparing custom solid dispersants, which could further improve the reproducibility of the method.

Author Contributions

B.H.: Investigation, Writing—original draft. N.Z.: Investigation. C.C.: Methodology. Y.J.: Validation. Z.Z.: Data Curation. L.W.: Data Curation. H.D.: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Fan, S.; Ren, X.; Shi, G.; Zhao, L.; Ma, J.; Li, Q.; Wen, D.; Zhang, Y. Determination of 28 Food Safety Risk Factors in Novel Foods by Ultra-high-performance Liquid Chromatography-quadrupole/Orbitrap High-resolution Mass Spectrometry. Food Qual. Saf. 2024, 9, fyae049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Chandrasekaran, M.; Ahmad, H.W. Investigation of the Persistence, Toxicological Effects, and Ecological Issues of S-Triazine Herbicides and Their Biodegradation Using Emerging Technologies: A Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, R.; Jin, M. Materials Synthesized in Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Detection of Food Contaminants. Food Qual. Saf. 2025, 9, fyaf006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Ru, S.; Wang, J.; Xiong, J.; Yang, L.; Hao, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Effects of Co-exposure of the Triazine Herbicides Atrazine, Prometryn and Terbutryn on Phaeodactylum Tricornutum Photosynthesis and Nutritional Value. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokosa, J.M. Principles for Developing Greener Liquid-Phase Microextraction Methods. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 167, 117256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notardonato, I.; Avino, P. Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Micro Extraction: An Analytical Technique Undergoing Continuous Evolution and Development—A Review of the Last 5 Years. Separations 2024, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo, E.d.M.; Maciel, P.K.; Luckow, A.C.B.; Malinowski, M.H.d.M.; Soares, B.M. Recent Developments in Reverse Phase-Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction: A Review. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 6282–6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, F.R.; Danielson, N.D. Solvent-terminated Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction: A Tutorial. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Xue, H.; Huang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Jia, L. An Effervescence-assisted Centrifuge-less Dispersive Liquid-Phase Microextraction Based on Solidification of Switchable Hydrophilicity Solvents for Detection of Alkylphenols in Drinks. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2021, 49, 21065–21071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tao, R.; Ju, Y.; Duan, J.; Xie, Q.; Fan, B.; Wang, F. Natural active products in fruit postharvest preservation: A review. Food Front. 2024, 5, 2043–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Crespo, E.A.; Pontes, P.V.A.; Silva, L.P.; Bülow, M.; Maximo, G.J.; Batista, E.A.C.; Held, C.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Tunable Hydrophobic Eutectic Solvents Based on Terpenes and Monocarboxylic Acids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 8836–8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, K.A.; Sadeghi, R. Database of Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Physical Properties: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 384, 121899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, M.A.; Anwar, F.; Saari, N. Valorization of Biomass for Food Protein via Deep Eutectic Solvent Extraction: Understanding the Extraction Mechanism and Impact on Protein Structure and Properties. Food Front. 2024, 5, 1265–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarurwa, H.; Tavengwa, N.T. Deep Eutectic Solvent-based Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Micro-extraction of Pesticides in Food Samples. Food Chem. 2021, 342, 127943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Xue, H.; Wu, B.; Wang, X.; Jia, L. Popping Candy-assisted Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction for Enantioselective Determination of Prothioconazole and its Chiral Metabolite in Water, Beer, Baijiu, and Vinegar Samples by HPLC. Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaroensan, J.; Khiaophong, W.; Kachangoon, R.; Vichapong, J. Efficient Analyses of Triazole Fungicides in Water, Honey and Soy Milk Samples by Popping Candy-generated CO2 and Sugaring-out-assisted Supramolecular Solvent-based Microextraction Prior to HPLC Determinations. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 4195–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deen, A.K.; Elmansi, H.; Belal, F.; Magdy, G. Recent Advances in Dispersion Strategies for Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction from Green Chemistry Perspectives. Microchem. J. 2023, 191, 108807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, R.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Green Aqueous Two-Phase Systems Formed by Sugaring-Out Effect in Aqueous Polymer/Ionic Liquid Solutions: A Review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 15838–15874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, Y. Simultaneous Determination of Trace Matrine and Oxymatrine Pesticide Residues in Tea by Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction Coupled with Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Test. 2024, 8, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammood, N.H.; Kadhim, F.A.; Al-Gufaili, M.K.; Azooz, E.A.; Snigur, D. A Comparative Review of Solidified Floating Organic Drop Microextraction Methods for Metal Separation: Recent Developments, Enhanced Co-factors, Challenges, and Environmental Assessment. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2025, 55, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Huang, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, H.; Jing, X. An Effervescence Tablet-Assisted Microextraction based on the Solidification of Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Determination of Strobilurin Fungicides in Water, Juice, Wine, and Vinegar Samples by HPLC. Food Chem. 2020, 317, 126424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Yang, L.; Zhao, W.; Wang, F.; Chen, Z.; Ma, L.; Jia, L.; Wang, X. Evaporation-Assisted Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction based on the Solidification of Floating Organic Droplets for the Determination of Triazole Fungicides in Water Samples by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1597, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; He, Y.; Ren, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, P. Research Progress on Single-Droplet Microextraction Technology. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 21763–21778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherniakova, M.; Varchenko, V.; Belikov, K. Menthol-Based (Deep) Eutectic Solvents: A Review on Properties and Application in Extraction. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202300267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazaieli, F.; Mogaddam, M.R.A.; Farajzadeh, M.A.; Feriduni, B.; Mohebbi, A. Development of Organic Solvents-free Mode of Solidification of Floating Organic Droplet–based Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction for the Extraction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from Honey Samples before Their Determination by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 43, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.R.; Gama, M.R.; Pizzolato, T.M. Ionic Liquids in Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction for Environmental Aqueous Samples. Microchem. J. 2025, 208, 112254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrarca, M.H.; Cunha, S.C.; Fernandes, J.O. Determination of Pesticide Residues in Soybeans Using QuEChERS Followed by Deep Eutectic Solvent-based DLLME Preconcentration Prior to Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1727, 464999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manousi, N.; Kabir, A.; Zachariadis, G.A. Recent Advances in the Extraction of Triazine Herbicides from Water Samples. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zheng, X.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Jing, X. Determination of chiral prothioconazole and its chiral metabolite in water, juice, tea, and vinegar using emulsive liquid–liquid microextraction combined with ultra-high performance liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Jing, X.; Wu, J. Determination of Triazine Herbicides from Water, Tea, and Juice Samples using Magnetic Dispersive Micro-solid Phase Extraction and Magnetic Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction with HPLC. Food Chem. 2025, 468, 142430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Niu, Y.; Bi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, L.; Jing, X. Rapid Analysis of Triazine Herbicides in Fruit Juices Using Evaporation-Assisted Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction with Solidification of Floating Organic Droplets and HPLC-DAD. Anal. Methods 2022, 14, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golmohammadpour, M.; Koltappeh, S.A.; Ayazi, Z.; Mohammad-Rezaei, R. Determination of Ametryn Residues in Fruit Juice Samples via Electro-enhanced Solid-Phase Microextraction using NiCo-LDH Coated Fiber and GC Analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 148, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucci, R.G.; da Silva, T.C.; Felipe, L.P.G.; Cestaro, B.I.; da Silva, B.J.G. Ultrasound-Assisted Solvent-Terminated Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction for Determination of Atrazine and Simazine in Bovine Milk via GC-MS. Food Anal. Methods 2025, 18, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. Extraction of Eugenol from Essential Oils by In Situ Formation of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Green Recyclable Process. J. Anal. Test. 2024, 8, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.