Abstract

Chirality remains the most neglected axis of pesticide residue science. Many active ingredients are sold as racemates although their enantiomers differ in potency, persistence, transport, and toxicology; as a result, total concentration is a poor surrogate for risk. This review synthesizes green and enantioselective strategies spanning the full analytical–remediation continuum. We survey solvent-minimized sample preparation approaches (SPME/TF-SPME, FPSE, µSPE, DLLME with DES/NADES), MS-compatible chiral separations (immobilized polysaccharide CSPs in LC and SFC, cyclodextrin-based selectors in GC, CE/CEC), and HRMS-enabled confirmation and suspect screening. Complex matrices (e.g., fermented beverages such as wine and high-sugar products) are critically discussed, together with practical matrix-tolerant workflows and the complementary role of chiral GC for hydrophobic residues. We then examine emerging enantioselective materials—MIPs, MOFs/COFs, and cyclodextrin-based sorbents—for extraction and preconcentration and evaluate stereoselective removal via adsorption, biodegradation, and chiral photocatalysis. Finally, we propose toxicity-weighted enantiomeric fraction (EF) metrics for decision-making, outline EF-aware green treatment strategies, and identify metrological and regulatory priorities (CRMs, ring trial protocols, FAIR data). Our thesis is simple: to reduce hazards efficiently and sustainably, laboratories and practitioners must measure—and manage—pesticide residues in the chiral dimension.

1. Introduction

1.1. Pesticide Residues in Food and Environmental Matrices: Current Status and Regulatory Perspectives

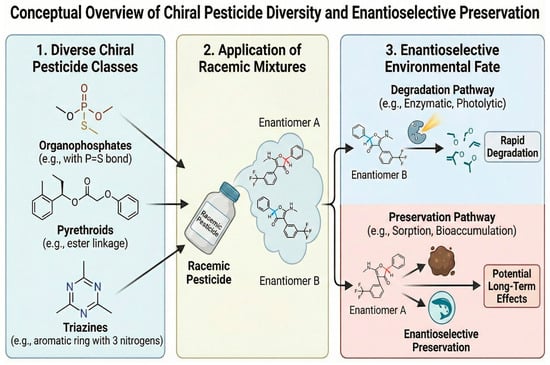

Pesticide residues remain among the most intensively monitored chemical contaminants in food and environmental matrices, with routine surveillance reporting detections across fruits, vegetables, cereals, milk, pollen, fruit/vegetable juices, jam, wine, honey, surface waters, sediments, and even indoor dust [1]. While reported violation rates are generally low in high-income regions, cumulative exposures to complex mixtures at trace levels continue to challenge risk assessors and regulators [2]. A notable yet under addressed dimension is stereochemistry: a substantial fraction of modern active ingredients are chiral, and their individual enantiomers frequently differ in pesticidal potency, off target toxicity, persistence, and bioaccumulation [3]. As visually synthesized in Figure 1, the application of these agrochemicals creates a complex exposure network where racemic mixtures, via differential enantiomeric fate and toxicity, indiscriminately affect target pests and non-target organisms alike, necessitating a shift toward stereochemical precision to mitigate ecological collateral [4]. Current maximum residue limit (MRL) frameworks—such as Codex Alimentarius, the European Union’s Regulation (EC) No. 396/2005, U.S. EPA tolerances, and China’s GB standards—are typically established for total residues of the racemate or the sum of isomers, seldom distinguishing enantiomer specific limits despite mounting evidence that enantiomeric composition can shift along the farm-to-fork continuum and within environmental compartments [5]. Because stereoselective processes—including sorption, photolysis, microbial transformation, and plant metabolism—can alter the enantiomeric fraction (EF) over time and space, monitoring that reports only total concentration risks masking hazard-relevant changes in exposure profiles [6].

Figure 1.

A comprehensive scheme illustrating the adverse effects of chiral pesticide application.

1.2. Multi-Residue Methods and the Pivotal Role of Sample Preparation

Over two decades, multi-residue workflows have converged on streamlined extraction–cleanup protocols coupled to tandem mass spectrometry, enabling the simultaneous quantification of hundreds of analytes in diverse matrices. The QuEChERS concept—“quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe”—with dispersive solid-phase cleanup (e.g., PSA, C18, GCB) remains the de facto starting point in many laboratories for fruits, vegetables, grains, and complex animal products [7]. LC–MS/MS and GC–MS/MS form the quantitative backbone, increasingly complemented by high-resolution MS for suspect and non-target screening [8]. Yet sample preparation remains the principal determinant of data quality due to matrix effects (ion suppression/enhancement), analyte instability, and recovery variance across physicochemical space—issues amplified in pigmented, fatty, or protein-rich matrices [9]. For chiral analytes, extraction conditions must additionally avoid epimerization or enantiomerization and preserve stereochemical integrity prior to enantioselective separation [10,11].

1.3. Green Analytical Chemistry and Microextraction

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) recasts analytical design around prevention, miniaturization, energy efficiency, and safer reagents, seeking to reduce the cumulative footprint of high-throughput surveillance without compromising data integrity [12]. Microextraction approaches—solid-phase microextraction (SPME), stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE), dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME), hollow-fiber LPME, fabric-phase sorptive extraction (FPSE), magnetic SPE, and related micro SPE formats—shrink solvent volumes by orders of magnitude, enable automation, and are inherently portable, thereby aligning with GAC while remaining compatible with chiral separations [13]. Parallel advances in greener media (e.g., bio-based sorbents, deep eutectic and natural deep eutectic solvents) further reduce toxic burden, though life cycle and toxicity assessments of some “green” solvents (e.g., certain ionic liquids) warrant careful scrutiny [14].

1.4. Scope and Structure of This Review

This review interrogates the “neglected chiral dimension” in pesticide residues through a green chemistry lens. We first examine greener sample preparation strategies suited for enantioselective analysis across food and environmental matrices. We then summarize advances in chiral separations and MS detection, followed by emerging enantioselective sorbents (MIPs, MOFs/COFs) for extraction and preconcentration. Finally, we assess stereoselective removal/degradation technologies and propose how EF-resolved data can be integrated into risk assessment and remediation design, highlighting practical gaps, standardization needs, and research priorities [5].

2. Green Sample Preparation for Enantioselective Analysis of Chiral Pesticides

2.1. Limitations of Conventional Sample Preparation for Chiral Analysis

Most legacy residue workflows—QuEChERS variants followed by dispersive SPE, gel permeation cleanup (GPC), or cartridge SPE—were optimized to maximize total recoveries across a wide polarity window, not to preserve stereochemical integrity. As a result, they often obscure or distort enantiomeric fractions (EFs) through differential extraction, cleanup, or ionization of enantiomers and diastereomers [15]. Strongly basic or acidic conditions used during buffering, cleanup, or derivatization can catalyze enantiomerization of α-stereogenic carboxylates and related motifs, while hydrolysis (e.g., of aryloxyphenoxypropionate esters) can alter the analyte form and, with it, the apparent EF [10]. Thermal stress and prolonged solvent evaporation may induce isomerization in multicenter pyrethroids, confounding enantiomer-resolved quantification [16]. Matrix effects—long recognized in LC/GC–MS—can be enantiomer differential, especially in pigmented or lipid-rich extracts where co-eluting interferences affect one enantiomer more than the other [17]. Finally, the scarcity of enantiomer-pure, isotopically labeled internal standards hampers accurate EF correction, making methodological bias more difficult to diagnose and control [17].

2.2. Microextraction Techniques Compatible with Enantioselective Analysis

Microextraction approaches shrink solvent volumes, minimize thermal and chemical stress, and reduce contact time—all favorable for preserving EFs while advancing Green Analytical Chemistry. The imperative for such gentle, solvent-minimized protocols is chemically dictated by the structural fragility of target analytes; as illustrated in Figure 2, chiral pesticides span diverse classes—from organophosphates to pyrethroid-possessing labile asymmetric centers and functional groups prone to hydrolysis or racemization under harsh conventional extraction conditions [5]. Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) and its high-area thin-film format (TF SPME) enable equilibrium or pre-equilibrium sampling from complex matrices with direct thermal or solvent desorption into GC or LC, respectively; when coupled to chiral stationary phases (CSPs) downstream, these formats deliver EF-resolved data with minimal sample manipulation [18].

Figure 2.

Chemical structural diversity of priority chiral pesticides requiring enantioselective preservation. Arrows indicate the processing flow.

Coatings doped with cyclodextrin (CD) or amino acid-derived selectors can impart partial enantioselectivity already at the extraction step, increasing method selectivity while preserving greenness [3]. Stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) and fabric-phase sorptive extraction (FPSE) expand phase volume while retaining low solvent use; these are attractive for hydrophobic chiral analytes (e.g., pyrethroids, triazoles) in waters and fruit purées and are fully compatible with LC–MS/MS after solvent back extraction [19]. Miniaturized SPE (µSPE/MEPS) using cartridges or pipette tips packed with chiral or CD-grafted sorbents allows fast extraction–cleanup cycles and is amenable to 96-well automation—critical for surveillance programs [20].

Beyond naming the formats, a useful way to “choose” among sorptive microextraction options is to compare capacity through the phase ratio concept (β = Ve/Vs, where Ve is the extraction-phase volume and Vs is the sample volume); in equilibrium sorptive extraction, the recovery (R) and enrichment (E) scale with β (R = Eβ) [21]. Because Ve differs by orders of magnitude across devices, a practical capacity hierarchy emerges: classical PDMS fiber SPME typically provides ~0.6 µL coating volume, while higher-capacity formats increase Ve to ~3.8–11.8 µL (SPME Arrow), ~40 µL (TF-SPME), ~63 µL (HiSorb), and ~24–126 µL (SBSE); i.e., SBSE can offer ~40–210× larger phase volume than fiber SPME [21].

For hydrophobic chiral pesticides in high-matrix-load samples (pigmented/polyphenol-rich or high-Brix matrices), the higher Ve reduces sorbent saturation and competitive displacement by co-extractives, improving robustness of LOQs and helping avoid recovery-driven EF bias. TF-SPME partially mitigates the capacity–speed trade-off by combining increased Ve with a higher surface-to-volume ratio (faster kinetics), while multi-cumulative trapping/repeated extraction strategies provide a practical sensitivity boost when using low-volume SPME formats [21]. From an implementation standpoint, packed-bed microformats such as MEPS and the pressure-driven µSPEed configuration offer syringe-compatible enrichment/cleanup; µSPEed’s one-way flow and smaller sorbent particles (≤3 µm) increase contact surface area and can be semi-automated using an electronic syringe, making them attractive for high-throughput monitoring workflows [22]. These phase volume and geometry considerations complement the solvent-based microextraction formats described below.

Liquid-phase microextraction (LPME) variants, including hollow-fiber LPME and electromembrane extraction (EME), use microliter acceptors and can incorporate chiral carriers (e.g., CDs, tartaric acid derivatives, chiral ionic liquids) to bias transmembrane flux [23]. Dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME) can be re-engineered with deep eutectic solvents (DES/NADES) or switchable hydrophilicity solvents to reduce toxicity and improve preconcentration; when paired with chiral LC or SFC, DLLME provides rapid, EF-preserving cleanup even for high-fat foods [18].

2.3. Green Solvents and Sorbent Materials for Chiral Pesticide Extraction

Deep eutectic solvents (DES) and natural DES (NADES) offer tunable polarity and hydrogen bonding networks, enabling DLLME or dispersive SPE workflows that avoid halogenated or highly volatile organic solvents; hydrophobic DES (e.g., thymol-based) efficiently extract hydrophobic chiral fungicides and pyrethroids [24]. Chiral DES (e.g., L menthol combinations) have emerged as bifunctional media—simultaneously “green” extractants and stereochemical discriminators—opening a path to enantio-enriched preconcentration prior to CSP-based separation [25]. Supercritical CO2 (SFE) provides another solvent-sparing option for fatty matrices (nuts, oils), with co-solvent-tuned recovery and reduced thermal load, and can be interfaced to chiral SFC or off-line LC [26].

On the sorbent side, bio-based materials—cellulose nanofibers, chitosan, and polydopamine—can be grafted with β cyclodextrin or amino acid selectors to deliver enantioselective µSPE, magnetic SPE, or FPSE while improving biodegradability and lowering embodied energy [27]. Carbonaceous and MOF-derived magnetic composites expand capacity yet must be evaluated for leaching and recyclability; ionic liquids and task-specific polymers, while powerful, require careful scrutiny of life cycle impacts to avoid “regrettable substitutions [28].”

2.4. Case Studies: From Food to Environmental Samples

Fruits and Vegetables: TF SPME followed by chiral LC–MS/MS has been validated for triazole fungicides (e.g., tebuconazole, hexaconazole, propiconazole) in citrus and berries, achieving sub µg kg−1 LOQs with solvent consumption in the tens of microliters and stable EFs across processing replicates—contrasting with EF drift observed under basic QuEChERS [29].

Cereals and Teas: Hydrophobic NADES DLLME coupled to chiral GC or SFC effectively isolates multicenter pyrethroids from roasted teas and rice, mitigating matrix pigments and preserving cis/trans-enantiomer distributions relative to conventional Soxhlet or pressurized liquid extraction [30,31].

Surface Waters: Headspace or direct immersion SPME with CD modified coatings, followed by chiral LC–MS, quantifies enantiomer-resolved mecoprop and fenoxaprop acids in river and runoff samples, enabling EF mapping along agricultural gradients and after storm events [32].

Soils and Sediments: Magnetic µSPE using β CD-grafted Fe3O4@polydopamine provides rapid cleanup of triazoles and aryloxyphenoxypropionates from fine soils; EFs are maintained during extraction and correlate with land use history [33].

Wastewater: EME with a CD containing acceptor selectively enriches azole fungicides from secondary effluents, furnishing EF-resolved, time-of-day profiles that track treatment performance and diurnal loadings [34].

Processed and Fermented Commodities: Enantioselective residue analysis becomes particularly challenging in high-sugar matrices (e.g., honey, jams, and juice concentrates) and polyphenol-/pigment-rich beverages (e.g., red wine and grape juice), where viscosity and abundant co-extractives can amplify matrix effects and compromise enantiomer-resolved quantification. In these matrices, matrix effects can be enantiomer-dependent (e.g., differential recoveries or ion suppression between enantiomers), so EF interpretation can become unreliable unless enantiomer-specific validation and matrix-matched calibration are performed. Importantly, food processing can also redistribute residues in ways that cannot be extrapolated from raw agricultural commodities: within the processing-factor (PF) framework, PF < 1 indicates reduction, whereas PF > 1 indicates a concentrating effect during dehydration/concentration steps—an issue directly relevant to juice concentration and jam manufacturing [35].

Fermentation further adds a mechanistic dimension because it functions as a biochemical reactor; during wine fermentation, tebuconazole showed enantioselective dissipation (R-tebuconazole eliminated faster than S-tebuconazole) and a pronounced EF increase from 0.46 to 0.68, indicating that microbial metabolism can reshape enantiomeric profiles and therefore risk interpretation [36]. Consistently, a recent study on wine and rice-wine processing reported stereoselective degradation for multiple chiral pesticides and PF values as low as 0.04–0.34 across processing, reinforcing that fermented products should be treated as dynamic matrices rather than ‘processed water’ [37]. Analytically, these challenging matrices motivate higher-capacity and more matrix-tolerant enrichment/cleanup (e.g., SBSE or FPSE with solvent back-extraction and/or modified QuEChERS) coupled with chiral LC–MS/MS, so that both LOQ and EF can be reported with defensible accuracy despite strong co-extractives.

3. Advanced Enantioselective Separation and Detection Platforms

3.1. HPLC with New-Generation Chiral Stationary Phases (CSPs)

High-performance liquid chromatography remains the workhorse for enantioselective analysis of pesticide residues, and recent CSP innovations have shifted practice from artisanal optimization toward robust, MS compatible methods. Immobilized polysaccharide CSPs (amylose/cellulose tris carbamates) now dominate because their covalent anchoring tolerates water, alcohols, and modest buffer levels, enabling normal-phase, reversed-phase, and polar organic modes on a single column—an advantage when handling heterogeneous matrices and when coupling with ESI–MS/MS [38]. Superficially porous (core–shell) chiral particles and sub 2 µm fully porous media deliver high efficiency at UHPLC back pressures, supporting narrow peaks and improved signal-to-noise ratios for low-level residues [39]. Beyond polysaccharides, macrocyclic antibiotic CSPs (vancomycin/teicoplanin) excel for azoles and aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicides via multipoint hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions, while zwitterionic/ion exchange-type CSPs provide strong retention and selectivity for acidic chiral herbicides such as mecoprop and dichlorprop [40].

Method development increasingly uses generic screens (3–5 CSP chemistries × 2–3 eluent families) to reach baseline resolution rapidly, followed by fine tuning of alcohol type, water fraction, and acid/base additives (e.g., formic or acetic acid; ammonium formate) to secure MS compatibility and EF stability [5]. Temperature is a powerful, often underused, variable: van ’t Hoff analysis can reveal enthalpy- or entropy-controlled regimes that allow isocratic baselines at lower organic content, reducing solvent use without sacrificing resolution [41]. Finally, 2D LC (achiral × chiral) resolves co-eluting matrix components and diastereomeric interferences; heart-cutting modes preserve sensitivity and are increasingly accessible using routine instruments [42].

3.2. Chiral Gas Chromatography (GC): Indispensable for Volatile and Semi-Volatile Chiral Pesticides

Despite the dominance of LC–MS/MS for many polar and thermally labile pesticides, chiral gas chromatography (GC) remains indispensable for volatile/semi-volatile and highly hydrophobic residues, particularly for pyrethroids and selected organochlorines where GC–MS offers mature ionization/detection options and very high separation efficiency. Complementary to LC, chiral GC (typically hyphenated to GC–MS) serves as a practical solution for these classes and provides high-efficiency enantioseparations. A recent critical review integrates and compares pesticide enantioseparation strategies across LC, SFC, GC, and capillary electromigration, summarizing key chiral selectors and platform-specific considerations [43]. Consequently, real-world monitoring campaigns still deploy GC–MS in parallel with LC–MS/MS to cover the full polarity spectrum of chiral residues, selecting the platform primarily based on volatility and logKow rather than analytical fashion [44].

Enantioselectivity in GC is most commonly achieved using derivatized cyclodextrin stationary phases, where transient inclusion complexation combined with hydrogen-bond/dipole and steric interactions provides stereodiscrimination; a consolidated overview of chiral GC columns, detectors, and performance metrics for pesticide enantioseparation is available [43]. Specifically, SBSE has been successfully utilized for extracting chiral residues from wine followed by thermal desorption GC–MS, leveraging its high capacity for flavor-rich matrices [36]. GC is also the natural “home field” for multi-chiral-center pyrethroids, whose 4–8 stereoisomers require high resolving power to avoid isomer–group co-elution and biased EF interpretation [45]. For extremely complex matrices, coupling green microextraction (HS-SPME, SBSE/HiSorb) with comprehensive GC×GC–MS provides a forward-looking solution by markedly increasing peak capacity and reducing co-elution-driven EF bias, while method validation should explicitly check for thermal degradation or racemization during injection/desorption [21].

3.3. Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC): A Greener Alternative

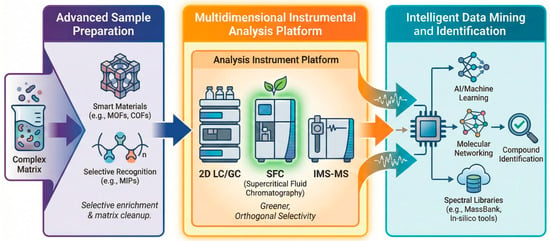

Chiral SFC leverages compressed CO2 with alcoholic modifiers (MeOH, EtOH, i PrOH) to deliver fast separations at low viscosity and high diffusivity, slashing the analysis time and organic solvent consumption relative to HPLC (Figure 3) [46]. Beyond its inherent green metrics, SFC has transcended its historical status as a niche technique to become a central pillar in the modern analytical ecosystem. As visualized in Figure 3, contemporary workflows now integrate SFC alongside 2D-LC and IMS-MS as a critical multidimensional “Analysis Instrument” platform, leveraging its orthogonal selectivity to untangle complex food matrices in high-throughput Nontargeted Screening (NTS) campaigns [47]. With modern back-pressure regulation and immobilized polysaccharide CSPs, most triazole fungicides, pyrethroids, and aryloxyphenoxypropionates achieve baseline separations within minutes (often Rs > 1.5 in 3–6 min) while maintaining gentle thermal conditions favorable to configurationally labile analytes [48,49].

Figure 3.

Positioning SFC within the modern non-targeted screening (NTS) analytical workflow. Arrows indicate the processing flow.

Ethanol—preferable from a green metrics standpoint—frequently matches or surpasses methanol for selectivity when paired with 0.1–0.5% acid/base additives that modulate ionizable analytes [26]. Coupling SFC to MS is now routine; APCI interfaces handle hydrophobic pesticides effectively, whereas ESI with make-up flow accommodates more polar chiral acids and oximes [50]. Strategic water addition (≤5%) in the modifier can improve peak shape for acidic herbicides without compromising supercriticality, though highly polar, strongly anionic targets may still require HILIC like LC modes [51]. Importantly, SFC’s rapid scouting capability enables high-throughput EF screening and straightforward scale up to preparative chiral SFC to isolate enantiopure reference standards—an essential, often overlooked, prerequisite for rigorous EF quantitation and for toxicology studies [26]. Life cycle assessments consistently indicate lower energy and waste footprints for SFC workflows, strengthening the environmental case for their broader adoption in residue labs [52].

3.4. Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) and Related Techniques

CE offers inherently “green” separations due to microliter consumption of aqueous buffers and minimal waste. Enantioseparations most commonly exploit neutral or charged cyclodextrins (CDs) as chiral selectors in capillary zone electrophoresis or micellar electrokinetic chromatography; the selector type and degree of substitution tune the cavity size and electrostatic interactions, allowing fine control over migration order for azoles, phenoxypropionates, and certain pyrethroids [53]. For ionizable herbicides, dual selector systems (e.g., sulfated β CD plus bile salt micelles) enhance resolution at low organic content [54]. Sensitivity—CE’s historical Achilles’ heel—has improved via field-amplified sample stacking, sweeping, and capillary solid-phase concentration, leading to sub ng mL−1 LOQs in water and food extracts after minimal cleanup [55]. CE–MS with sheathless interfaces expands the scope to complex matrices using volatile electrolytes (ammonium acetate/formate) and MS-friendly CDs, though ruggedness still lags LC/SFC in routine monitoring [56]. Chiral capillary electrochromatography (CEC) with monolithic polysaccharide phases merges LC-like selectivity with CE efficiency for fast EF determination [57].

3.5. Coupling with Tandem MS and High-Resolution MS

Because enantiomers are isomasses, chromatographic or electrophoretic resolution is a precondition for mass-spectrometric quantification. In LC/SFC–MS/MS, scheduled MRM transitions, matrix-matched calibration, and isotopically labeled surrogates deliver robust quantitation; in the absence of enantiomer pure labeled standards, bracketing with racemic labeled analogs plus EF specific response factor checks provides a pragmatic compromise [11]. High-resolution MS (Orbitrap/TOF) adds exact mass confirmation, fragment ion fidelity, and suspect screening for transformation products; when combined with chiral pre-separation (1D or 2D), HRMS enables retrospective mining of EF-resolved datasets across monitoring campaigns [58].

Ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) generally cannot separate enantiomers; nevertheless, diastereomeric adduct strategies (e.g., gas-phase complexation with chiral crown ethers or CDs) create mobility differences that help deconvolute co-eluting matrix isomers and confirm peak purity—useful adjuncts rather than replacements for CSPs [59]. For gas chromatographic routes relevant to volatile chiral pesticides, cyclodextrin-based chiral GC columns paired with triple-quadrupole MS remain effective, though thermal lability and derivatization artifacts must be diligently controlled [11]. Across platforms, rigorous system suitability (resolution, selectivity factor, EF precision < 2–3%) and orthogonal confirmation (alternate CSP or mode) are critical quality anchors to prevent EF distortion by subtle co-elution or ion suppression asymmetry [60].

4. Emerging Enantioselective Materials for Extraction and Preconcentration

4.1. Chiral Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)

Enantioselective MIPs transpose the logic of asymmetric synthesis into sorbent design: a chiral template (often the bioactive enantiomer or a close structural analog) is complexed with functional monomers and cross-linked to freeze a complementary, stereodefined cavity. When the template is removed, the polymer expresses differential binding (ΔΔG_bind) for opposite enantiomers, which can be harnessed for selective preconcentration prior to chiral LC/SFC or, in some cases, for direct stereoselective cleanup that enriches the environmentally relevant enantiomer [57]. Advances most relevant to pesticide residues include (i) surface imprinting on silica, magnetic Fe3O4, or electrospun fibers to shorten mass transfer paths and raise capacity; (ii) “nanoMIPs” prepared by precipitation or RAFT polymerization with narrow site distributions; and (iii) dummy template strategies to avoid template bleeding when the analytical limits of detection are in the low ng kg−1 range [61].

For triazole fungicides and aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicides, MIPs prepared with acidic (e.g., methacrylic acid) and H bond-donating monomers show enantioselective factors α = 1.5–3.0 in aqueous methanol, sufficient to improve EF precision after matrix cleanup of fruits, grains, and waters [62]. Coating SPME fibers or stir bars with thin MIP layers yields robust, low-solvent workflows compatible with LC–MS/MS; photo initiated polymerization enables room-temperature fabrication that preserves monomer chirality and reduces energy use [63]. Computational pre-screening (DFT/MD) has matured into a practical tool to predict monomer–template pairing and ΔΔG trends, cutting experimental iterations and supporting greener design spaces [64].

4.2. Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs)

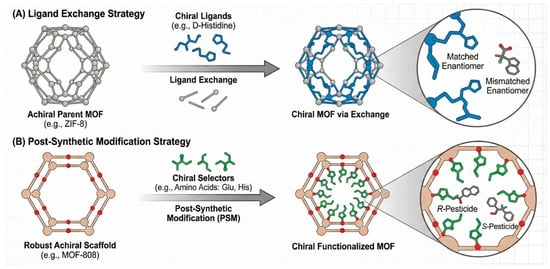

Framework materials bring crystallinity, permanent porosity, and modularity to enantioselective extraction. In MOFs, chirality can arise from intrinsically chiral linkers (e.g., BINOL, camphorate, or tartaric-derived ligands) or via post-synthetic modification of robust scaffolds (e.g., UiO 66, MIL 101) with chiral selectors such as amino acids or cyclodextrins [65]. As visually elaborated in Figure 4, the versatility of MOFs allows for the precise engineering of chiral microenvironments—either through ligand exchange (e.g., D-His-ZIF-8, Figure 4A) or post-synthetic functionalization (e.g., MOF-Glu/His, Figure 4B)—creating tunable channels that stereoselectively discriminate guest molecules based on their spatial configuration, a mechanism distinct from the rigid cavities of MIPs. These modular pore structures facilitate the selective adsorption of target enantiomers through stereochemical matching within the confined nano-space, offering a versatile alternative to MIPs [66]. The resulting channels display steric and stereoelectronic complementarity that discriminates between R/S forms of pesticides bearing aromatic and heteroatom motifs (e.g., triazoles, phenoxypropionates), often with α > 2 in mixed aqueous–organic eluents and good recyclability over tens of cycles [67].

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of two primary strategies for engineering chiral microenvironments within metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). (A) The ligand exchange approach. (B) The post-synthetic modification (PSM) approach.

Magnetic chiral MOF composites facilitate rapid separation and integration into µSPE cartridges; their Lewis acidity also assists in the preconcentration of N/O donor analytes without excessive organic modifiers [68].

Beyond structural advantages (high surface area, tunable pore microenvironments), recent MOF/COF platforms have already delivered data-rich, matrix-relevant performance for enantiomer-resolved pesticide analysis. For instance, a zirconium-based UiO-66 MOF integrated into a magnetic core–shell composite (Fe3O4@C@UiO-66) enabled MSPE coupled with chiral LC–MS/MS for the simultaneous enantiomeric determination of eight chiral pesticides in water and fruit juices, achieving ultra-trace sensitivity (LODs 0.10–0.35 ng L−1; LOQs 0.35–1.00 ng L−1) with recoveries of 83.68–95.99% and a total separation time within 19 min [39]. This case underscores how hydrolytically robust Zr-MOFs and magnetic handling can reduce solvent/handling burdens while maintaining stereochemical resolution in complex aqueous matrices. Likewise, hierarchical hybridization can further enhance practical extraction in sugar- and pigment-containing samples: a magnetic LDH/MOF composite (Fe3O4@CuZnAl-LDH@MIL-100(Fe)) was demonstrated for the simultaneous extraction and enantiomeric determination of three chiral triazole fungicides in water and juice, providing LOQs of 1.00–3.80 µg L−1 and recoveries of 86.28–98.22% [69].

Importantly, COF chemistry is also extending beyond sorptive enrichment toward rapid enantio-discriminating screening: a post-synthetically modified chiral fluorescent COF (COF Dha Tab-3) enabled optosensing of imazamox enantiomers with detection limits of 4.20 and 3.03 µmol L−1 for the S- and R-forms, respectively, and showed preferential interaction with R-imazamox (e.e. 5.30%) [70]. Collectively, these case studies move MOFs/COFs from “promising adsorbents” to operational tools that report enantiomer-specific figures of merit (LOD/LOQ, recovery and recognition metrics) in chemically challenging matrices.

COFs, constructed from light elements via dynamic covalent chemistry, can be rendered chiral by using chiral monomers (e.g., proline, BINOL) or by chiral induction during crystallization [71]. β Ketoenamine and imine COFs with helical pores exhibit size/shape-filtered enantioselectivity and superior hydrolytic stability compared with early COFs, enabling solid-phase extraction of azoles and pyrethroids in high-moisture foods with minimal solvent [72]. While scale up remains nontrivial, gram-scale syntheses under solvent lean or mechanochemical conditions are now feasible, foreshadowing routine deployment in residue labs [73].

4.3. Other Emerging Chiral Sorbent Materials

Cyclodextrin (CD) polymers and CD-grafted carbons (graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes) offer accessible, bio-derived selector chemistries; hydrophobic cavity-driven host–guest interactions complement H bonding to afford modest but useful enantioselectivity for bulky, aromatic pesticides [74]. Chiral ionic liquids (CILs) immobilized on silica or polymer brushes act as tunable ion exchange/π–π selectors in µSPE and FPSE, especially for acidic herbicides; task-specific cations (e.g., imidazolium L amino acid derivatives) impart adjustable stereodiscrimination and green solvent compatibility [75]. Peptide, polypeptoid, and short oligonucleotide decorated surfaces introduce biomimetic recognition that can be tailored to specific pharmacophores present in triazoles or oxime carbamates, though long-term robustness in organic modifiers needs improvement [76]. Finally, chiral porous organic cages and helicene-based polymorphs supply discrete, shape persistent cavities with notable enantio-enrichment factors during off-line cleanup—promising for small-volume, high-selectivity tasks [77].

4.4. Green Aspects and Practical Limitations

Selectivity is a double-edged sword in analytical preconcentration: while chiral enrichment can sharpen limits of detection, it may bias the measured EF unless recoveries are verified for each enantiomer. Consequently, calibration with enantiomer-resolved standards or EF-bracketed QC samples is mandatory when using chiral MIPs/MOFs/COFs upstream of chiral separations [78]. From a green perspective, imprinting traditionally relies on volatile organic porogens and extensive Soxhlet-style template removal; recent transitions to NADES/aqueous media, supercritical CO2 washing, and photo-initiated or mechanochemical syntheses substantially reduce solvent and energy footprints [79]. Nevertheless, challenges persist: site heterogeneity, template leakage, framework stability in high-salt or high-fat matrices, potential metal leaching from MOFs, and microplastic concerns for polymeric particulates [80]. Economic and regulatory acceptance hinges on batch-to-batch reproducibility, regeneration without performance decay (>50 cycles), and validated life cycle assessments demonstrating net benefit over conventional d SPE or silica-based cleanup [81]. Future progress will likely couple computation guided selector design with scalable, solvent lean fabrication and rigorous EF-aware validation protocols [82].

5. Enantioselective Removal and Degradation of Chiral Pesticides

5.1. Concept of “Chiral Removal”: Beyond Total Concentration Reduction

Traditional treatment metrics—percent removal or residual concentration—collapse a stereochemically heterogeneous mixture into a single number and can therefore misrepresent hazards. “Chiral removal” explicitly evaluates changes in enantiomeric fraction (EF) alongside total mass, recognizing that the toxicodynamic and toxicokinetic profiles of R/S forms often diverge substantially [3]. For a racemate, an intervention that preferentially eliminates the less toxic enantiomer can increase specific risk despite high overall removal; conversely, selective depletion of the more toxic enantiomer (Etox) can deliver meaningful risk reduction even with modest total removal [83]. Accordingly, process evaluation should report (i) concentration-based removal, (ii) ΔEF across unit operations, and (iii) a risk-weighted removal index integrating enantiomer-specific potency or guideline values when available [84]. Mass balance with EF tracking across sorption, biotransformation, and oxidation steps is essential to avoid apparent EF shifts caused by analytical bias or differential matrix effects [85]. Framing removal in this stereochemically explicit way converts EF from a diagnostic curiosity into an operational design and compliance parameter [71].

5.2. Stereoselective Adsorption and Separation

Adsorptive strategies exploit enantioselective interactions at the solid–liquid interface. Chiral molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) packed in mini columns or coated on magnetic cores achieve α (selectivity factors) of ~1.3–3.0 for triazoles, aryloxyphenoxypropionates, and certain pyrethroids, enabling continuous flow polishing with low pressure drops; regeneration with ethanol/water maintains capacity over tens of cycles [57]. Chiral MOF/COF sorbents—either intrinsically chiral or post-synthetically functionalized with amino acids or cyclodextrins—offer higher capacities and rapid kinetics and can be integrated as magnetically recoverable particles or as thin films on porous support [39]. Enantioselective membranes (imprinted polyamide, β cyclodextrin gated nanofiltration) demonstrate measurable permselectivity under cross flow, pointing to scalable platforms for irrigation return flows and food processing wastewaters [86]. In real matrices, natural organic matter (NOM), electrolytes, and surfactants can attenuate stereoselectivity by competing for binding sites; surface passivation (e.g., polydopamine) and hydrophilic outer layers mitigate fouling and preserve α over longer runs [87]. Hybrid “adsorb and react” beds that embed photocatalysts or oxidants into chiral sorbents promise both capture and selective degradation [87].

5.3. Biodegradation and Bioremediation with Enantioselectivity

Microbial and plant-associated transformations are inherently chiral because active sites of enzymes enforce stereochemical preferences. Soil and activated sludge communities often degrade phenoxypropionate herbicides (e.g., mecoprop, dichlorprop) with pronounced S or R selectivity governed by enantioselective esterases and β oxidation-like pathways; rate constants (kR, kS) can differ by factors of 2–10, leading to predictable EF trajectories describable by parallel first-order models [3]. For triazole fungicides, cytochrome P450 like monooxygenases in Sphingomonas/Pseudomonas often favor one enantiomer, while white rot fungi (laccase/peroxidase systems) display mediator-dependent enantioselectivity in aromatic ring hydroxylation [88]. Constructed wetlands and membrane bioreactors retain EF trends observed in lab microcosms, though mass transfer limitations and diel redox swings can dampen selectivity; bioaugmentation with strains pre-adapted to specific enantiomers restores kR/kS separation and stabilizes EF at the outlet [89]. Rhizoremediation adds root exudate driven co-metabolism and micro-oxic niches that bias enantiomer uptake and turnover, with consequential EF shifts in porewaters [90]. Importantly, partial biodegradation may yield chiral transformation products (TPs) with distinct EFs and toxicities, underscoring the need for chiral LC–HRMS suspect screening during pilots [5].

5.4. Enantioselective Catalytic Degradation (Photocatalysis, Advanced Oxidation, Etc.)

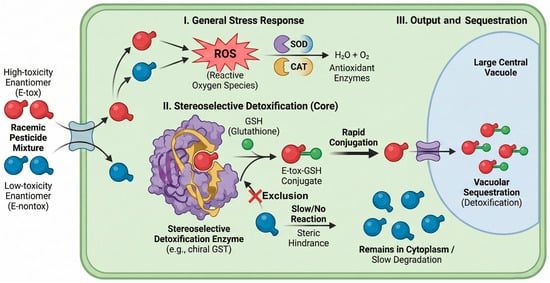

Non-selective radicals (•OH, SO4•−) typically oxidize enantiomers at similar rates; selectivity emerges when adsorption or charge transfer at a chiral catalyst surface becomes rate-limiting. TiO2 or ZnO modified with L/D tartaric acid, proline, or helicene-like ligands shows adsorption controlled, light-driven degradation that depletes Etox more rapidly than its mirror image for selected azoles and pyrethroids [91]. Complementing these abiotic strategies, biological systems offer sophisticated enzymatic machinery for pesticide detoxification.

As illustrated in Figure 5, plants deploy a multi-tiered defense involving antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT) and conjugation systems (GSTs) to sequester and degrade xenobiotics [5,92]. Harnessing these intrinsic biological pathways, particularly their stereoselective enzyme systems, represents a promising frontier for green, in situ remediation of chiral residues. This schematic delineates the coordinated action of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) scavenging systems (e.g., SOD, CAT) and stereoselective Phase II detoxification enzymes (e.g., chiral GST) that preferentially conjugate pesticide metabolites based on steric fit for vacuolar sequestration. Understanding these stereoselective enzymatic pathways is key to developing phytoremediation strategies that preferentially eliminate toxic enantiomers.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of stereoselective enzymatic detoxification pathways for chiral pesticides within a plant cell.

Chiral MOF photocatalysts (e.g., BINOL-derived Zr MOFs) and helical g C3N4 nanostructures similarly bias hole/electron interactions and orient substrates for enantio-differential oxidative steps [93]. In sulfate radical AOPs, immobilizing Co/Fe–N–C catalysts within chiral polymer matrices imposes stereoselective pre-complexation that translates into measurable ΔEF under flow [94]. Electrocatalysis on cysteine or tartaric acid-modified electrodes exhibits modest but reproducible enantio rate differences, potentially enhanced by chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS) effects [95]. Across platforms, combining chiral adsorption (“pre orientation”) with localized oxidative steps (“adsorb react desorb”) maximizes selectivity while suppressing over-oxidation and TP accumulation [96].

5.5. Critical Assessment: How Far Are We from Practical Application?

Proof of concept demonstrations now span sorption, bioprocessing, and catalysis, but few systems have crossed the boundary into validated, full-scale operations with EF-resolved monitoring. Barriers include (i) durability and fouling of chiral materials in NOM rich streams, (ii) modest selectivity (α ≈ 1.3–2) that requires multi-stage trains, (iii) uncertain fate and toxicity of chiral TPs, and (iv) the absence of regulatory drivers mandating EF tracking [97]. Near-term priorities include modular pilots combining chiral adsorption with biological polishing, rigorous mass balance including TPs, and adoption of EF-based performance “guardrails” (target ΔEF for Etox depletion) in treatment specifications [98]. With such discipline, enantioselective removal can evolve from academic curiosity to a credible axis of green remediation [5].

6. Integrating Enantioselective Analysis with Risk Assessment and Green Remediation

6.1. Linking Enantiomeric Fraction (EF) Data to Environmental Risk

The enantiomeric fraction EF = CR/(CR + CS) (or C+/Ctotal for multi-chiral centers after grouping by bioactive pair) is more than a forensic tracer of stereoselective fate; it is an exposure metric with direct toxicological meaning when enantiomer-specific potencies differ [99]. A racemic input (EF = 0.50) that drifts toward the more toxic enantiomer (Etox) under field conditions can increase risk even as total concentration declines—an effect invisible to conventional monitoring [100]. As conceptually illustrated in Figure 6, while total residue concentrations decline over time (a typical dissipation scenario, Figure 6A), the EF value can significantly drift from the racemic baseline (Figure 6B). This stereoselective enrichment—where one enantiomer (e.g., the more toxic one) persists longer—demonstrates why total concentration is an insufficient metric for risk assessment, necessitating the adoption of toxicity-weighted EF (twEF) [101].

Figure 6.

Conceptual illustration of “Silent Risk”: the divergence of Enantiomeric Fraction (EF) from racemate (0.5) during environmental dissipation. (A) Normalized dissipation curves showing that while the total concentration of a racemic pesticide decreases over time (black dashed line), stereoselective degradation leads to the faster disappearance of the less toxic enantiomer (blue line) compared to the more toxic one (red line). (B) The resulting shift in the Enantiomeric Fraction (EF, defined here as the fraction of the more toxic enantiomer) over time. The EF value drifts significantly away from the racemic baseline (0.5), indicating an enrichment of the more toxic form. This demonstrates why relying solely on total concentration monitoring can obscure the true ecological risk [101].

To operationalize this, we advocate a “toxicity weighted EF” (twEF):

where PFs are enantiomer-specific potency factors derived from comparative in vitro bioassays, species-specific LC50/EC50 ratios, or benchmark dose modeling [102]. twEF collapses to EF when PFR = PFS but inflates the contribution of Etox when PFs diverge, aligning the metric with health-relevant endpoints and mixture risk calculations (e.g., toxic units) [103].

In surveillance, spatiotemporal EF/twEF mapping, analyzed with Bayesian hierarchical models that incorporate analytical uncertainty (precision of EF, censored data), enables probabilistic statements about risk hot spots and the likely dominance of biodegradation versus dilution [104]. Finally, EF-resolved source apportionment (e.g., chiral signatures of product formulations versus biotransformed residues) improves attribution in complex catchments and supports targeted interventions where they matter most [105].

6.2. Designing Remediation Strategies with Chiral Information

Chiral information should guide what to remove, where, and how. Decision-making begins by diagnosing process fingerprints: enrichment of one enantiomer at constant total mass implicates stereoselective sorption; enrichment accompanied by transformation products (TPs) with coherent EFs indicates biotic or catalytic pathways [106]. For waters with EF > 0.5 toward Etox in triazoles, design a two stage train: (i) chiral pre-adsorption on MIP or CD-modified magnetic sorbents targeting Etox, monitored by on-line chiral SFC–MS to meet a target ΔEF toward the benign enantiomer, and (ii) bio-polishing in a membrane bioreactor seeded with strains exhibiting the complementary enantio preference to mineralize the residual Esafe [107]. In soils, EF trends inform whether to emphasize sorption (e.g., chiral MOF/COF amendments) or rhizoremediation/bioaugmentation; if kR/kS ≫ 1 for Etox, oxygenated microzones and co-substrates that upregulate the relevant monooxygenases are prioritized [108].

Protocol-wise, we recommend EF explicit design of experiments; they should include EF/twEF as response variables, screen process variables (pH, redox, photoflux, residence time) for their leverage on ΔEF and set “guardrails” (e.g., twEFout ≤ 0.35 for racemic influent) rather than only concentration limits [109]. Reactor control can be automated via soft sensors that infer EF from proxy signals (e.g., differential removal across paired chiral sorbent beds) when on-line chiral analytics are not continuously available [109].

7. Challenges, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Outlook

7.1. From Method Development to Routine Monitoring

The grand challenge is translation: moving elegant, EF-resolved methods from specialist labs into high-throughput, compliance-orientated workflows. Three bottlenecks dominate. First, there is metrology. Routine labs need uncertainty budgets that explicitly include enantiomer-specific recovery, matrix effects, and racemization during storage/cleanup; without this, EF results are not decision-grade. The adoption of ring trial vetted “MICR” (Minimum Information for Chiral Residues) reporting—CSP identity, resolution (Rs), selectivity (α), EF precision, orthogonal confirmation, and ISTD strategy—would create common quality anchors [110,111]. A second challenge concerns reference materials. Enantiopure CRMs and isotopically labeled enantiomers remain scarce and costly, impeding calibration and system suitability testing in matrix-rich extracts [112]. Third, there is the issue of integration. Most residue labs are configured around QuEChERS LC/GC–MS/MS; retrofitting chiral LC/SFC or CE requires validated screening protocols, automated scouting, and software that manages paired peak quantification with EF-specific QC limits [5]. Practical solutions include 2D LC (achiral × chiral) switching for “EF flagged” analytes, retention time locking across CSP lots, and matrix-matched calibration with EF bracketed QCs [113]. Regulatory pilots that request EF co-reporting alongside MRL compliance would accelerate normalization [114].

7.2. Toward Greener and Higher-Throughput Enantioselective Workflows

Greenness and throughput need not be trade-offs. Automated TF SPME/SPME, 96-well µSPE/MEPS with CD or MIP functionalized phases, and magnetic bead formats enable parallel sample preparation with microliter solvent footprints and minimal energy input [115]. UHPSFC on immobilized polysaccharide CSPs provides sub 5 min separations; multiplexed column banks and staggered injections can double throughput without increasing solvent usage [116]. On-line enrichment (turboflow/on-line SPE) coupled directly with chiral LC/SFC reduces handling and EF drift, while ethanol-rich eluents and scCO2 minimize VOC emissions [10]. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and greenness metrics (e.g., Analytical Eco Scale, AGREE) should be reported alongside analytical figures of merit so that EF precision and environmental footprint are optimized jointly [117]. Furthermore, emerging technologies like ion mobility–mass spectrometry (IM-MS) are breaking the speed limits of traditional chromatography. As exemplified in Figure 7, by converting enantiomers into diastereomers via rapid derivatization, IM-MS can achieve separation in seconds rather than minutes, offering a glimpse into the ultra-high-throughput future of chiral residue screening [118,119]. This schematic illustrates a workflow where chiral analytes (e.g., amino acids, adaptable to pesticides) are derivatized with a chiral selector and separated in the gas phase based on differences in their 3D shapes and resulting collision cross-sections (CCSs). This approach reduces analysis time from minutes to seconds, representing the pinnacle of “throughput” and “greenness” by virtually eliminating solvent waste.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the mechanism behind second-scale chiral discrimination using ion mobility–mass spectrometry (IM-MS) [118,119].

Digital twins that emulate EF response to process parameters—pH, temperature, modifier, CSP choice—can guide DoE-based optimization with fewer wet runs, shrinking time, waste, and cost [120]. Finally, lightweight scripts for EF-aware QA (automated twin peak integration, symmetry checks, EF control charts) reduce analyst burden and improve reproducibility [121].

7.3. Future Trends

Several trajectories are already visible. (i) From racemates to eutomers: registration dossiers will increasingly favor single-enantiomer formulations, compressing environmental uncertainty and simplifying EF interpretation while demanding enantiomer-resolved toxicology [122]. (ii) Edge analytics: portable chiral sensing—imprinted electrochemical sensors, CD-gated nanopore membranes, and mini SFC modules—will push EF screening forward in the field and to processing plants [52]. (iii) Computation first design: machine learning-assisted selector design (MIP/MOF/COF) and predictive eluent/CSP matching will shorten development cycles and privilege greener solvents [123]. (iv) EF-aware remediation: hybrid “adsorb react” beds and bio-electrocatalytic systems will target the toxic enantiomer preferentially, and treatment contracts will specify ΔEF or twEF guardrails alongside concentration limits [124]. (v) Data infrastructure: FAIR repositories for raw chiral chromatograms and EF uncertainty will enable meta-analysis and regulatory confidence [125].

8. Conclusions

Chirality reframes pesticide residue science: when enantiomers differ in toxicity and fate, conventional “total concentration” monitoring obscures the very dimension that governs hazard. The enabling toolkit now exists. On the analytical side, solvent lean microextraction preserves stereochemical integrity; MS-compatible chiral LC/SFC/CE provides rapid, robust EF measurements; HRMS secures identification and opens up suspect screening for chiral transformation products. On the materials and engineering side, enantioselective sorbents (MIPs, MOFs/COFs, cyclodextrin-based hybrids) and chiral catalysts translate analysis into action by capturing or degrading the toxic enantiomer preferentially.

What lags is translation to routine practice. Decision-grade EF requires reference materials, EF-aware QA, and software that treats enantiomer pairs as first-class analytical entities. Greenness must be quantified—not assumed—so that minimized solvent, energy, and waste accompany high sensitivity and accuracy. Most importantly, EF (and its toxicity-weighted analog) should be co-reported with concentration and embedded in remediation specifications. When laboratories, engineers, and regulators act together on these points, the chiral dimension will move from a neglected curiosity to a practical, green standard for measuring—and reducing—risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G. and B.L.; methodology, Z.G.; software, B.L. and Z.G.; validation, H.G., B.L., and Z.G.; formal analysis, H.G.; investigation, B.L. and Z.G.; resources, H.G.; data curation, B.L. and Z.G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L. and Z.G.; writing—review and editing, H.G.; visualization, H.G.; supervision, H.G.; project administration, H.G.; funding acquisition, H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key R&D Program of China, grant number 2018YFC1604402.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MRL | Maximum residue limit |

| EF | Enantiomeric fraction |

| GAC | Green Analytical Chemistry |

| SPME | Solid-phase microextraction |

| SBSE | Stir bar sorptive extraction |

| DLLME | Dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction |

| FPSE | Fabric-phase sorptive extraction |

| GPC | Gel permeation cleanup |

| CSPs | Chiral stationary phases |

| CD | Cyclodextrin |

| LPME | Liquid-phase microextraction |

| EME | Electromembrane extraction |

| DES | Deep eutectic solvent |

| NADES | natural DES |

| SFE | Supercritical CO2 |

| SFC | Supercritical fluid chromatography |

| NTS | Nontargeted Screening |

| CE | Capillary electrophoresis |

| CEC | Chiral capillary electrochromatography |

| IMS | Ion mobility spectrometry |

| MIPs | Molecularly imprinted polymers |

| MOFs | Chiral metal–organic framework |

| COFs | covalent organic frameworks |

| PSM | post-synthetic modification |

| CILs | Chiral ionic liquids |

| NOM | Natural organic matter |

| TPs | Transformation products |

| CSTs | Conjugation systems |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| CISS | Chiral-induced spin selectivity |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| CCS | collision cross-section |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| LDH | Layered double hydroxide |

| MEPS | Microextraction by packed sorbent |

| MSPE | Magnetic solid-phase extraction |

| PF | Processing factor |

| TF-SPME | Thin-film solid-phase microextraction |

References

- Wahab, S.; Muzammil, K.; Nasir, N.; Khan, M.S.; Ahmad, M.F.; Khalid, M.; Ahmad, W.; Dawria, A.; Reddy, L.K.V.; Busayli, A.M. Advancement and New Trends in Analysis of Pesticide Residues in Food: A Comprehensive Review. Plants 2022, 11, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisner, O.; Frische, T.; Liebmann, L.; Reemtsma, T.; Ross-Nickoll, M.; Schäfer, R.B.; Schäffer, A.; Scholz-Starke, B.; Vormeier, P.; Knillmann, S.; et al. Risk from pesticide mixtures—The gap between risk assessment and reality. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 149017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, X.Y.; Jiang, S.X.; Han, J.J.; Wu, J.X.; Yan, M.L.; Yao, Z.L. Enantioselective Behaviors of Chiral Pesticides and Enantiomeric Signatures in Foods and the Environment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 12372–12389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.L.; Zhao, L.L.; Kang, S.S.; Liew, R.K.; Lichtfouse, E. Toxicity and environmental fate of the less toxic chiral neonicotinoid pesticides: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 23, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashistha, V.K.; Sethi, S.; Mittal, A.; Das, D.K.; Pullabhotla, R.V.S.R.; Bala, R.; Yadav, S. Stereoselective analysis of chiral pesticides: A review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.S.; Sun, X.F.; Lv, B.; Xu, J.Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.Y.; Gao, B.B.; Shi, H.Y.; Wang, M.H. Stereoselective environmental fate of fosthiazate in soil and water-sediment microcosms. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.M.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.Z.; Xie, L.F.; Wu, Y.B.; Li, G.L. Current Research Status, Opportunities, and Future Challenges of Nine Representative Persistent Herbicides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 21959–21972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mesa, M.; Moreno-González, D. Current Role of Mass Spectrometry in the Determination of Pesticide Residues in Food. Separations 2022, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Olomukoro, A.A.; Emmons, R.V.; Goodage, N.H.; Gionfriddo, E. Matrix effects demystified: Strategies for resolving challenges in analytical separations of complex samples. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, e2300571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cabeza, R.; Francioso, A. Chiral Pesticides with Asymmetric Sulfur: Extraction, Separation, and Determination in Different Environmental Matrices. Separations 2022, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhou, R.D.; Xie, H.Y.; Li, G.; Xu, Z.G.; Liu, M.J.; Gao, W.T. Chiral Separation and Determination of Multiple Organophosphorus Pesticide Enantiomers in Soil Based on Cellulose-Based Chiral Column by LC-MS/MS. J. Sep. Sci. 2025, 48, e70100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez-Cejuela, H.; Gionfriddo, E. Evolution of Green Sample Preparation: Fostering a Sustainable Tomorrow in Analytical Sciences. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 7840–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.D.; do Nascimento, H.O.; Gomes, H.D.; do Nascimento, R.F. Pesticide residues in groundwater and surface water: Recent advances in solid-phase extraction and solid-phase microextraction sample preparation methods for multiclass analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Microchem. J. 2021, 168, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razic, S.; Arsenijevic, J.; Mracevic, S.D.; Musovic, J.; Trtic-Petrovic, T. Greener chemistry in analytical sciences: From green solvents to applications in complex matrices. Curr. Chall. Future Perspect. Crit. Rev. Anal. 2023, 148, 3130–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ovidio, C.; Bonelli, M.; Rosato, E.; Tartaglia, A.; Ulusoy, H.I.; Samanidou, V.; Furton, K.G.; Kabir, A.; Ali, I.; Savini, F.; et al. Novel Applications of Microextraction Techniques Focused on Biological and Forensic Analyses. Separations 2022, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.L.; Kiss, L.; Mei, H.B.; Remete, A.M.; Ponikvar-Svet, M.; Sedgwick, D.M.; Roman, R.; Fustero, S.; Moriwaki, H.; Soloshonok, V.A. Chemical Aspects of Human and Environmental Overload with Fluorine. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4678–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Maia, A.S.; Ribeiro, C.; Tiritan, M.E. Chiral analysis with mass spectrometry detection in food and environmental chemistry. In Mass Spectrometry in Food and Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 249–273. [Google Scholar]

- Vallamkonda, B.; Sethi, S.; Satti, P.; Das, D.K.; Yadav, S.; Vashistha, V.K. Enantiomeric Analysis of Chiral Drugs Using Mass Spectrometric Methods: A Comprehensive Review. Chirality 2024, 36, e23705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Câmara, J.S.; Perestrelo, R.; Berenguer, C.V.; Andrade, C.F.P.; Gomes, T.M.; Olayanju, B.; Kabir, A.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pereira, J.A.M. Green Extraction Techniques as Advanced Sample Preparation Approaches in Biological, Food, and Environmental Matrices: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocelli, M.D.; Medina, D.A.V.; Lanças, F.M.; dos Santos-Neto, A.J. Automated microextraction by packed sorbent of endocrine disruptors in wastewater using a high-throughput robotic platform followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 6165–6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, D.; Spadafora, N.D.; Aspromonte, J.; Pellegrino, R.; Purcaro, G. Exploring different high-capacity tools and extraction modes to characterize the aroma of brewed coffee. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 4501–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cansino, L.; García, M.Á.; Marina, M.L.; Câmara, J.S.; Pereira, J.A. Simultaneous microextraction of pesticides from wastewater using optimized μSPEed and μQuEChERS techniques for food contamination analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayatloo, M.R.; Tabani, H.; Nojavan, S.; Alexovic, M.; Ozkan, S.A. Liquid-Phase Microextraction Approaches for Preconcentration and Analysis of Chiral Compounds: A Review on Current Advances. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2023, 53, 1623–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell-Rozas, L.; Canales, R.; Lara, F.J.; García-Campaña, A.M.; Silva, M.F. A natural deep eutectic solvent as a novel dispersive solvent in dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction based on solidification of floating organic droplet for the determination of pesticide residues. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 6413–6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucci, E.; Falcinelli, G.; Antonelli, L.; Dal Bosco, C.; Felli, N.; De Cesaris, M.G.; Gentili, A. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent-ferrofluid microextraction followed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry for the enantioselective determination of chiral agrochemicals in natural waters. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2025, 417, 1341–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Rahimi-Nasrabadi, M.; Mirsadeghi, S.; Pourmortazavi, S.M. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Pesticides and Insecticides from Food Samples and Plant Materials. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 51, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, M.; Laddha, H.; Agarwal, M.; Gupta, R. Effective Adsorption–Desorption Kinetic Study and Statistical Modeling of Bentazon Herbicide Mediated by a Biodegradable β-Cyclodextrin Cross-Linked Poly(vinyl alcohol)–Chitosan Hydrogel. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madugula, A.C.S.; Haselbach, L.; Jeffryes, C.; Henry, J.; Benson, T.J. Environmental life cycle assessment methods applied to amine-ionic liquid hybrid CO absorbents. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 54, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Li, M.F.; Jin, X.Z.; Yao, L.P.; Wang, W.Y.; Liu, J.S.; Li, Z.G. Combination of switchable hydrophilic solvent liquid-liquid microextraction with QuEChERS for trace determination of triazole fungicide pesticides by GC-MS. Anal. Sci. 2023, 39, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganmohanrao, L. Role of deep eutectic solvents as alternate solvents in the microextraction and estimation of pesticide, insecticide, fungicide residues and metal contaminants in tea (Camellia sinensis). Microchem. J. 2025, 208, 112515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.Q.; Guo, Z.Y.; Li, X.T.; Huang, X.; Teng, C.; Chen, Z.J.; Jing, X.; Zhao, W.T. Analysis of pyrethroids in cereals by HPLC with a deep eutectic solvent-based dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction with solidification of floating organic droplets. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, S.M.S.; Salemi, A.; Jochmann, M.; Joksimoski, S.; Telgheder, U. Development and comparison of direct immersion solid phase micro extraction Arrow-GC-MS for the determination of selected pesticides in water. Microchem. J. 2021, 164, 106006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaziarati, M.; Sereshti, H. A facile in-situ ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of terephthalic acid-layered double hydroxide/bacterial cellulose: Application for eco-friendly analysis of multi-residue pesticides in vineyard soils. Microchem. J. 2024, 202, 110761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assress, H.A.; Nyoni, H.; Mamba, B.B.; Msagati, T.A.M. Target quantification of azole antifungals and retrospective screening of other emerging pollutants in wastewater effluent using UHPLC-QTOF-MS. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 253, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, O.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Dai, X.; Kong, Z. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Fates of Pesticide Residues in Edible Agricultural Products during Food Processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 18525–18544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Tian, J.; Dai, X.; Kong, Z. Potential risks of tebuconazole during wine fermentation at the enantiomer level based on multiomics analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 12129–12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wen, N.; Lu, Z.; Wei, W.; Shi, H.; Wang, M. Enantioselective Degradation and Processing Factors of Seven Chiral Pesticides During the Processing of Wine and Rice Wine. Chirality 2025, 37, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Xie, S.M.; Yuan, L.M. Recent progress in the development of chiral stationary phases for high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, P.; Xiong, Z.; Yu, J. Magnetic solid-phase extraction based on zirconium-based metal-organic frameworks for simultaneous enantiomeric determination of eight chiral pesticides in water and fruit juices. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 131056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, O.H.; Catani, M.; Mazzoccanti, G.; Felletti, S.; Manetto, S.; De Luca, C.; Ye, M.C.; Cavazzini, A.; Gasparrini, F. Boosting the enantioresolution of zwitterionic-teicoplanin chiral stationary phases by moving to wide-pore core-shell particles. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1676, 463190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, W., Jr.; Watts, W.; Umstead, W.J. The separation of several organophosphate pesticides on immobilized polysaccharide chiral stationary phases. Chirality 2022, 34, 1078–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, M.E.D.; Acquaviva, A.; Padró, J.M.; Castells, C.B. Comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatographic method (Chiral x Achiral) for the simultaneous resolution of pesticides. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1673, 463126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrão, D.B.; Perovani, I.S.; de Albuquerque, N.C.P.; de Oliveira, A.R.M. Enantioseparation of pesticides: A critical review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 122, 115719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Di, S.; Yan, J. Chiral pesticides levels in peri-urban area near Yangtze River and their correlations with water quality and microbial communities. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 3817–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, D.; Razis, A.F.A.; Yusof, N.A.; Mazlan, N.; Nordin, N.; Yu, C.Y. A review of emerging techniques for pyrethroid residue detection in agricultural commodities. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.T.; Huang, J.L.; Wu, J.Q.; Zhang, Q.L. Evaluation of supercritical fluid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry for the analysis of pesticide residues in grain. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, e2300623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Shi, C.; Li, H.; You, Z.; Fang, M.; Wang, C.; Deng, X.; Shao, B. Recent Advances in Nontargeted Screening of Chemical Hazards in Foodstuffs. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunyadi, C.; Szemán, J.; Juvancz, Z.; Mörtl, M.; Székács, A.; Kaleta, Z. Chiral separation of conazole pesticides using supercritical fluid chromatography. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 104, 5012–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.H.; Jiang, Q.T.; Xiu, F.C.; Bao, W.Q.; Hu, B.Z.; Xu, D.M. Residue analysis and degradation studies of two chiral pyrethroids in cabbage by ultra performance convergence chromatography. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutillas, V.; Ferrer, C.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Liquid chromatography versus supercritical fluid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry: A comparative study of performance for multiresidue analysis of pesticides. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 5849–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiesser, S.; Chepliaka, H.; Kollback, J.; Quennesson, T.; Czechtizky, W.; Cox, R.J. N-Trifluoromethyl Amines and Azoles: An Underexplored Functional Group in the Medicinal Chemist’s Toolbox. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 13076–13089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutillas, V.; Ferrer, C.; Martínez-Bueno, M.J.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Green analytical approaches for contaminants: Sustainable alternatives to conventional chromatographic methods. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1750, 465921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Perrucci, M.; Ciriolo, L.; D’Ovidio, C.; de Grazia, U.; Ulusoy, H.I.; Kabir, A.; Savini, F.; Locatelli, M. Applications of electrophoresis for small enantiomeric drugs in real-world samples: Recent trends and future perspectives. Electrophoresis 2024, 45, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriba, G.K.E. Update on chiral recognition mechanisms in separation science. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, e2400148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Miao, S.Y.; Tan, J.H.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, D.D.Y. Capillary Electrophoresis: A Three-Year Literature Review. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 7799–7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cansino, L.; Boltes, K.; García, M.A.; Marina, M.L. Simultaneous enantiomeric separation of fenpropidin and its acid metabolite by Capillary Electrophoresis. Analysis of agrochemicals, degradation study in soil, and ecotoxicity evaluation on. Talanta 2025, 295, 128233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, Z.Y.; Si, Q.K.; Lu, X.L.; Wang, P.; Wu, D.Z.; Mei, Y.Y. Monolithic capillary electrochromatographic system based on gold nanoparticles and chitosan chiral molecularly imprinted polymers for enantioseparation of metolachlor and separation of structural analogs. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.T.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.T.; Liang, W.Y.; Yan, Z.Q.; Lu, X.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhao, C.X.; Xu, G.W. Suspect and nontarget screening of pesticides and their transformation products in agricultural products using liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry. Talanta 2025, 283, 127154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoben, C.; Hartner, N.T.; Hitzemann, M.; Raddatz, C.R.; Eckermann, M.; Belder, D.; Zimmermann, S. Regarding the Influence of Additives and Additional Plasma- Induced Chemical Ionization on Adduct Formation in ESI/IMS/MS. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectr. 2023, 34, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadic, D.; de Lima, A.P.; Ricci, M. Quality assurance and quality control for human biomonitoring data-focus on matrix reference materials. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2025, 417, 3513–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.J.; Gao, P.; Wu, M.J.; Luo, K.; Li, J.P. Construction of a molecularly imprinted electroluminescence sensor for pyrimethanil detection dummy template imprinting combined with click-chemical labeling of mimic enzymes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1363, 344169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martello, L.; Ainali, N.M.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Lambropoulou, D.A. Multivariate design and application of novel molecularly imprinted polymers selective for triazole fungicides in juice and water samples. Microchem. J. 2023, 192, 108968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Faysal, A.; Dorreh, S.; Kaya, B.S.; Gölcü, A. Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensors for Halogenated anti-Infective Agent Detection: A Review of Current Developments and Prospects. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 35327–35351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenzadeh, E.; Ratautaite, V.; Brazys, E.; Ramanavicius, S.; Zukauskas, S.; Plausinaitis, D.; Ramanavicius, A. Design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIP) using computational methods: A review of strategies and approaches. Wires Comput. Mol. Sci. 2024, 14, e1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Chen, Z.J.; Dong, J.Q.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y. Chiral Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 9078–9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Chen, G.Y.; Qin, Y.D.; Li, T.T.; Yang, F.Q. Recent Advance in Electrochemical Chiral Recognition Based on Biomaterials (2019–2024). Molecules 2025, 30, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, L.A.M.; dos Reis, R.A.; Chen, X.F.; Ting, V.P.; Nayak, S. Metal-Organic Frameworks as Potential Agents for Extraction and Delivery of Pesticides and Agrochemicals. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 45910–45934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manousi, N.; Plastiras, O.E.; Kalogiouri, N.P.; Zacharis, C.K.; Zachariadis, G.A. Metal-Organic Frameworks in Bioanalysis: Extraction of Small Organic Molecules. Separations 2021, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tang, J.; Chen, T.; Peng, J.; Guo, H.; Zhang, R.; Lv, X.; Fan, R. Facile synthesis of magnetic layered double hydroxide/metal–organic framework MIL-100 (Fe) for simultaneous extraction and enantiomeric determination of three chiral triazole fungicides in water and juice samples. Microchem. J. 2024, 201, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; You, X.; Guo, X.; Chu, H.; Dong, Q.; Cui, H.; Jin, F.; Gao, L. A chiral fluorescent COF prepared by post-synthesis modification for optosensing of imazamox enantiomers. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 291, 122370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Xu, W.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, C.; Li, H. Porous Organic Frame Materials for Adsorption and Removal of Pesticide Contaminants: A Review. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.H.; Xu, G.J.; Zhou, Y.R.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.L.; Lian, Y.J.; Zhao, R.S. Ketoenamine Covalent Organic Framework Coating for Efficient Solid-Phase Microextraction of Trace Organochlorine Pesticides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 8008–8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.Y.; Qiao, X.L.; Ren, H.X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.J. Industrialization of Covalent Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 8063–8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzeri, G.; Verissimo, L.; Murtinho, D.; Pais, A.A.C.C.; Perrin, F.X.; Ziarelli, F.; Iordache, T.V.; Sarbu, A.; Valente, A.J.M. Poly(β-cyclodextrin)-Activated Carbon Gel Composites for Removal of Pesticides from Water. Molecules 2021, 26, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, T.; Perera, D.; Russo, G.; Wiedmer, S.K. Liquid Chromatographic and Capillary Electromigration Techniques for the Analysis of Azole Antifungals. J. Sep. Sci. 2025, 48, e70135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudpour, M.; Karimzadeh, Z.; Ebrahimi, G.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Dolatabadi, J.E.N. Synergizing Functional Nanomaterials with Aptamers Based on Electrochemical Strategies for Pesticide Detection: Current Status and Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2022, 52, 1818–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.H.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhao, R.; Wang, L.H.; Yuan, M.; Zhao, H.F.; Li, H.X.; Yang, X.; Wang, K.J. Chiral carbon nanostructures: A gateway to promising chiral materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 17073–17127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouant, A.D.; Hela, D. Extraction and Analytical Techniques for Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Sediments: A Critical Review Towards Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, A.; Yayla, S.; Hurkul, M.M.; Ozkan, S.A. The Sample Preparation Techniques and Their Application in the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Medicinal Plants. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. Effects of Microplastics on Bioavailability, Persistence and Toxicity of Plant Pesticides: An Agricultural Perspective. Agriculture 2025, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, L.A.; Vakh, C.; Dushna, O.; Kalisz, O.; Bocian, S.; Tobiszewski, M. Guidelines on the proper selection of greenness and related metric tools in analytical chemistry-a tutorial. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1357, 344052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Hernández, K.I.; Delgado-Alvarado, E.; Pawar, T.J.; Olivares-Romero, J.L. Chirality in Insecticide Design and Efficacy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 20722–20737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, S.S.; Cang, T.; Liu, Z.Z.; Xie, Y.Y.; Zhao, H.Y.; Qi, P.P.; Wang, Z.W.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.Q. Comprehensive evaluation of chiral pydiflumetofen from the perspective of reducing environmental risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, M.; Martín, J.; Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Enantioselective behavior of environmental chiral pollutants: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Env. Sci. Tec. 2022, 52, 2995–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Yao, Y.M.; Chen, S.J.; Li, Y.C.; Xiao, N.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H.Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Z.P.; Zhu, H.K.; et al. An Enhanced Protocol to Expand Human Exposome and Machine Learning-Based Prediction for Methodology Application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 3376–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, B.; Zhong, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L.; Cai, M.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Construction of Micropore Membranes for Efficient Separation of Chiral Pesticides Based on Layer-by-Layer Technology. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.Y.; Wu, W.H.; Jin, M.Q. Electrochemical aptasensing strategies for emerging organic pollutants in environmental analysis. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 7586–7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, D.L.; Voiculescu, D.I.; Filip, M.; Ostafe, V.; Isvoran, A. Effects of Triazole Fungicides on Soil Microbiota and on the Activities of Enzymes Found in Soil: A Review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramteke, P.K.; Rathod, A.P. Biological Treatment Methods for Remediating Wastewater. In Machine Learning in Water Treatment; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gámiz, B.; López-Cabeza, R.; Cox, L.; Celis, R. Environmental Fate of Chiral Pesticides in Soils. In The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]