Abstract

Capacitive deionization (CDI) technology represents an emerging and energy-efficient solution for seawater desalination and wastewater treatment. To further enhance its sustainability and economic viability, it is very important to develop high-performance electrodes made from low-cost and renewable raw materials. Herein, a new electrode material is introduced; the material was derived from wheat straw and modified via a simple and green process using ammonium ferric citrate (AFC) as a synergistic activator and modifier. The modification of AFC significantly enhanced the physicochemical properties of biochar. At the optimal AFC concentration of 1 mol·L−1, the specific surface area reached 321.27 m2·g−1, with a specific capacitance of 208.19 F·g−1. In the NaCl desalination experiment, the MWC-1.0 electrode exhibited a desalination capacity of 13.62 mg g−1 under the conditions of 1.2 V voltage and 2 mm electrode spacing in an initial solution concentration of 500 mg L−1. After 20 cycles of adsorption/desorption, the deionization capacity of the material was still retained at 90.5% of its initial capacity, demonstrating excellent regeneration performance. This work provides a sustainable method for preparing efficient and stable biochar electrodes, further highlighting its potential application in energy-saving seawater desalination technology.

1. Introduction

With economic and social development alongside population growth, global freshwater resources are facing a severe structural shortage [1,2,3]. Converting seawater into usable freshwater represents a fundamental strategic initiative to tackle the increasingly severe global water crisis [4,5,6]. Currently, conventional desalination methods confront operational challenges including excessive energy requirements, significant membrane fouling issues, and high maintenance costs, making them economically unsuitable for treating water with medium to low salinity levels [7,8]. Over the past few years, capacitive deionization (CDI) has been developed rapidly as a prospective desalination solution [9,10]. This technology utilizes an electrostatic field to adsorb ions onto the surface of porous electrodes, thereby achieving highly efficient seawater desalination [11]. It is characterized by low energy consumption, chemical-free operation, and good environmental sustainability. CDI is now progressively being applied in many fields, such as seawater desalination, industrial wastewater reuse, and emergency water supply, charting an innovative course for the green transformation of future water treatment technologies.

The capacity of CDI primarily depends on the electrochemical performance of the electrode material [12]. Ideal CDI electrode materials usually show a suitable pore structure, a high specific capacitance, excellent conductivity, and stable cycling performance while being economically friendly. Carbon-based materials represent a major class of electrode materials used in CDI systems [13,14]. These materials offer advantages, such as good conductivity and tunable pore structures. They primarily include activated carbon [15], carbon fibers [16], carbon nanotubes [17], etc. Despite the excellent deionization capability of these electrode materials, they are still hindered by issues including relatively prohibitive costs, complex preparation processes, and difficulties in achieving industrial production.

In recent years, biochar-derived electrode materials have gained traction as a CDI solution. The transport of internal ions is facilitated due to the porous structure of biochar [18]. Natural elements such as O and N also exhibit self-doping effects, which further enhance the hydrophilicity and electrochemical properties of biochar [19,20,21,22]. However, biochar produced via direct pyrolysis exhibits limited types of surface functional groups and a low specific surface area, leading to a weak adsorption capacity. Therefore, modification is often required to enhance its physical and chemical adsorption capabilities [23,24]. Modification methods usually include physical and chemical approaches. Physical methods commonly involve steam and CO2 activation [25], which are energy-intensive, and the modified biochar may exhibit insufficient hydrophilicity. Chemical methods, which commonly employ activators such as KOH, NaOH, and ZnCl2, are faster and less energy-consuming than physical methods [26]. However, these chemical reagents typically pose certain environmental hazards. Unlike the aforementioned activators, ammonium ferric citrate (AFC) is a food additive commonly used in dairy products and biscuits, offering the advantages of being environmentally friendly and cost-effective. During the pyrolysis process, the hydrophilic functional groups of AFC not only augment more functional components in biochar, but the substances produced via its decomposition (CO2, H2O, and Fe3O4) also form pores within the carbon framework, enhancing its electrochemical performance by providing more adsorption active centers. Some studies have reported that, through the carbonization of AFC, Fe3O4 particles were successfully distributed uniformly on a carbon skeleton derived from AFC, thereby preparing an anode material with excellent electrochemical performance [27]. Therefore, using biochar modified with AFC to prepare electrode materials is feasible.

This study utilized wheat straw, a common agricultural waste material in northern China, as a raw material and employed AFC as the modifier to prepare modified biochar. The performance of the modified biochar in capacitive deionization experiments was systematically investigated. The modified biochar exhibited a good mesoporous structure, a large number of hydrophilic functional groups, and Fe3O4 loading, demonstrating excellent electrochemical performance. In NaCl desalination experiments, this material displayed an outstanding adsorption capacity and cyclability. This research utilized environmentally friendly, renewable materials to fabricate electrodes, which open up broad prospects for development in low-cost seawater desalination, wastewater treatment, and electrochemical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Wheat straw was taken from the experimental field of Henan Agricultural University. AFC was gained from Tianjin Damiao Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China. Graphene, KOH, HCl, NaCl, N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAC), and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were bought from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. The reagents used in this work are analytical-grade and have not undergone any further processing.

2.2. Preparation of Modified Biochar Materials

The wheat straw was washed and dried before undergoing initial carbonization, which was subsequently pulverized and screened through a 50-mesh screen. Then, the wheat straw material was placed in a tubular furnace for carbonization under a N2 atmosphere of 0.2 L·min−1. When the temperature was increased to 400 °C (10 °C·min−1), it was maintained for 2 h to obtain biochar materials. For biochar modification, 10 g of biochar was weighed separately and immersed in AFC solutions with concentrations of 0, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0, and 1.1 mol·L−1. After soaking for 24 h, the materials were extracted and dried until reaching a constant weight. In the following carbonization process, the temperature of the tubular furnace was 600 °C, which was kept for 2 h. To eliminate ash impurities, the obtained samples were submerged in a 5% HCl solution for 2 h and then rinsed with deionized water until the pH approached neutrality. Finally, AFC-modified materials were obtained after being dried overnight at 105 °C. The modified wheat char (MWC) was denoted as MWC-0, MWC-0.6, MWC-0.7, MWC-0.8, MWC-0.9, MWC-1.0, and MWC-1.1, respectively.

The modified biochar, PVDF (binder), and graphene (conductive additive) were mixed in a ratio of 8:1:1 and thoroughly ground. Subsequently, an appropriate amount of DMAC was added to the mixture until it became a slurry. Next, the electrode slurry underwent 6 h of magnetic stirring and was then coated onto nickel foam using the impregnation and evaporation coating method, with the thickness of the biochar coating being approximately 0.3 mm. The coated nickel foam sheets were subsequently oven-dried at 80 °C for 6 h and finally pressed in a hot press at 3 MPa and 160 °C (PVDF melting point: 160–170 °C) for 5 min. Following these treatments, the samples were ready for use as working electrodes in subsequent testing.

2.3. Characterization Methods

The size and morphology of materials were identified through scanning electron microscopy (SEM, SUPRA 55, Oberkochen, Germany). The crystal structure of the material was determined via X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/max 2500, Tokyo, Japan). Chemical functional groups were characterized via Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet IS50, Madison, WI, USA). The specific surface area and pore size distribution were evaluated through N2 adsorption–desorption measurements at −196 °C (Micromeritics ASAP 2020 HD88, Norcross, GA, USA). Prior to analysis, all samples were degassed under vacuum at 150 °C for 6 h. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method was employed to determine specific surface area, and the pore diameter distribution was derived from the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) model.

2.4. Electrochemical Characteristics

The electrochemical characteristics of the electrodes were tested on a CHI660E electrochemical workstation. The modified biochar electrodes, a 1 cm2 platinum plate electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode were used as working, counter, and reference electrodes, respectively. The 3 mol·L−1 KOH solution was used as an electrolyte. The cyclic voltammetry (CV), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) tests were all measured on this workstation. The specific capacitance SC can be evaluated through Equation (1) [28].

where I represents the discharge current (A), Δt refers to the discharge time (s), and m defines the mass of modified biochar materials (g), while ΔV represents the voltage variation range (V).

2.5. CDI Desalination Tests

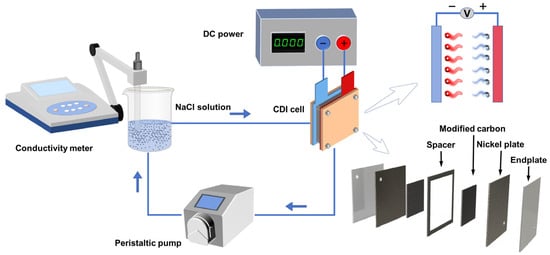

The CDI desalination process of the experiment is shown in Figure 1. The CDI module serves as a crucial component of the experimental system, and the electrode preparation method is described in Section 2.2, with an electrode plate size of 6 × 8 cm. Experimental data was measured every 30 s using a conductivity meter. The experiment began with a calibration of conductivity against the salt-solution concentration, revealing a good linear relationship between solution conductivity and concentration (y = 1.99095x + 4.1271, where y represents conductivity, and x represents concentration, R2 = 0.9997). This work investigated the desalination performance of different materials in salt solutions, examining the influences of voltage (0.8, 1.0, 1.2, and 1.4 V), solution concentration (300, 400, 500, and 600 mg·L−1), and electrode spacing (1.5, 2.0, 2.5, and 3.0 mm) on the desalination capacity. Finally, the electrode’s regeneration performance was investigated after 20 adsorption/desorption cycles.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of desalination process.

The desalination capacity q (mg·g−1) and desalination rate r (mg·g−1·min−1) can be obtained from Equations (2) and (3) [29,30].

where C0 denotes the initial salt-solution concentration (mg·L−1), Ct represents the concentration at time t (mg·L−1), V refers the solution volume (L), and m defines the mass of MWC coated on the electrode plate (g), while t represents the adsorption time (min).

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Material Characterization

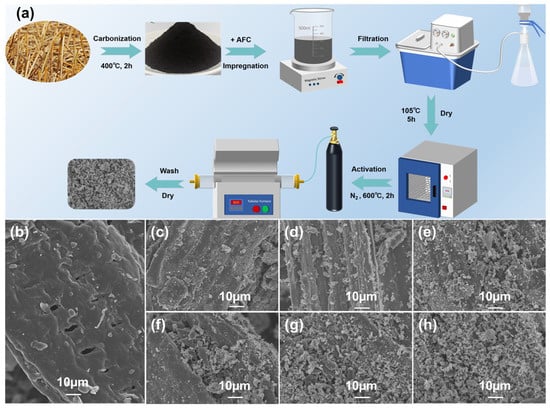

Figure 2 shows the preparation process and surface appearance of AFC-modified biochar. The results suggested that the overall structure was retained with the multilayer bundle structure of cellulose with lamellar pores and slit-type inhomogeneous pore channels. Before modification, a smooth surface of biochar was exhibited. As the concentration of AFC increased, its surface of biochar became increasingly rough, and more white particles appeared, which were partially embedded in the layered gap of the biochar. The shape of loaded materials was developed from punctate and needle-like to cluster-like, which indicated a successful loading of AFC pyrolysis products (iron oxides) onto the biochar surface. These loadings provided additional adsorption sites for electrochemical processes. For MWC-0 to MWC-1.0 (Figure 2b–g), the gradual increase in interlayer pores and the intensification of fragmentation in the biochar were observed, suggesting that AFC acted as an effective pore-forming agent during the activation process. The surface loading distribution of MWC-1.0 showed a greater uniformity. When the impregnation concentration exceeded 1 mol·L−1, a significant agglomeration of surface-loaded materials occurred on the biochar. At this point, the loaded materials may have blocked the pore structure, hindering the ion transport between pores.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic diagram of MWC preparation process; SEM images of MWC samples (b) MWC-0, (c) MWC-0.6, (d) MWC-0.7, (e) MWC-0.8, (f) MWC-0.9, (g) MWC-1.0, and (h) MWC-1.1.

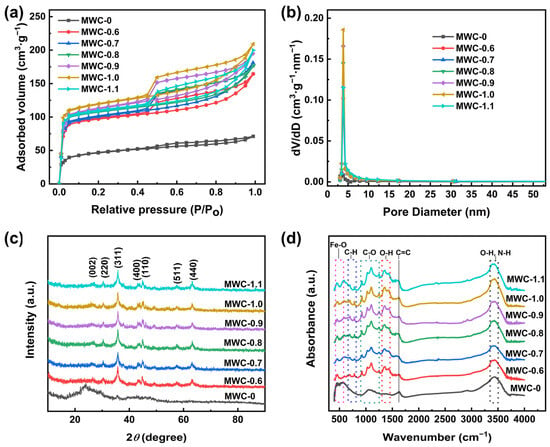

The adsorption–desorption isotherms of N2 are shown in Figure 3a. The samples exhibited combined characteristics of Type I and Type IV isotherms, indicating that all of these MWC materials possessed a multi-level pore structure [31]. The adsorption–desorption isotherm of unmodified biochar was relatively flat, whereas those of modified biochar showed a significant improvement. In the relatively high-pressure region, the curve continued to rise. It indicated that the modified biochar had a richer mesoporous structure, which led to the phenomenon of multi-layer adsorption [1,32]. Compared to unmodified biochar, the modified samples exhibited larger hysteresis loops, which were classified as the “H4” type, indicating the existence of abundant mesopores in the modified carbon. These results are substantiated by the pore size distribution diagram in Figure 3b. Among the modified samples, the highest N2 adsorption volume was detected for MWC-1.0, with the adsorption–desorption curve outperforming those of other samples. It indicated that the peak was reached for the physical adsorption ability of the MWC at an AFC concentration of 1.0 mol·L−1. After modification treatment, the specific surface area and pore volume of the modified biochar were increased markedly (Table 1). This may be attributed to the products generated via AFC during the pyrolysis process, which promoted the formation of biochar pores. Among them, MWC-1.0 achieved the best performance (321.27 m2·g−1 and 0.186 cm3·g−1). When the AFC concentration exceeded 1 mol·L−1, a decline in the data was observed. This decline might have been caused by the agglomeration of loaded material, which led to pore clogging.

Figure 3.

(a) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, (b) pore size distribution, (c) XRD patterns, and (d) FTIR patterns of different MWC materials.

Table 1.

The specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size of different MWC materials.

In order to reveal the crystal structure of biochar materials upon modification, an XRD analysis was performed to determine their phase composition and atomic arrangement. As shown in Figure 3c, the significant differences between the pristine and modified biochar are revealed via XRD patterns. Before modification, a classic broad diffraction peak of around 2θ = 22° was observed for pristine biochar, indicating an amorphous state. The sharp diffraction peaks of the modified biochar indicated enhanced crystallinity and physicochemical stability. The diffraction peak at 2θ = 26.4° corresponded to the (002) crystal plane of graphite [33], indicating successful modification. This result demonstrated that the modification process promoted the graphitization of biochar, yielding a graphitization degree of 79.07%. The electrical conductivity of biochar was significantly enhanced due to the formation of the graphitized structure, which was crucial for applications in electrode materials. The diffraction peaks of the modified biochar at around 2θ = 30.24°, 35.63°, 43.28°, 57.27°, and 62.93° corresponded to the (220), (311), (400), (511), and (440) crystal planes of Fe3O4 (PDF#19-0629), respectively [27,34,35]. This proved that Fe3O4 was successfully loaded onto biochar. The peak at 44.67° corresponded to the (110) crystal plane of Fe (PDF#06-0696) [36]; this might be due to the partial reduction in Fe3O4 during the pyrolysis process.

Functional groups are essential groups for electron gain and loss with significant effects on biochar electrochemical characteristics [37]. Figure 3d shows the FTIR patterns of biochar, indicating that the modified biochar featured a wider range of functional groups than the unmodified biochar. Peaks between 3350 and 3450 cm−1 represented O-H stretching vibration (hydroxyl) and N-H stretching vibration (amine) [38]. Compared with the blank sample, the broader shapes were detected for the peaks of the modified ones, indicating that N-H stretching vibrations were superimposed onto the original peaks. The peak at 1625 cm−1 represented C=C stretching vibration of the benzene ring [39]. Peaks at 1350 and 1430 cm−1 corresponded to the O-H bending vibration of the carboxyl group [40]. Peaks in the range of 900 and 1300 cm−1 were attributed to C-O stretching vibrations [41]. Peaks at 783 and 695 cm−1 represented C-H bending vibrations in the benzene ring [42]. Peaks at 584 and 450 cm−1 were due to the vibrations of Fe-O [43], indicating successful loading of the iron oxide (Fe3O4) onto the biochar. The aromatic framework inherent to biochar was retained for the modified biochar, and it contained massive hydrophilic functional groups, which strengthened the affinity and reactivity of biochar. Meanwhile, the loading of Fe3O4 on a carbon framework can provide more active adsorption sites and catalytic activity. These characteristics confer potential advantages for the material in both adsorption and catalytic applications.

3.2. Electrochemical Characteristics’ Analysis

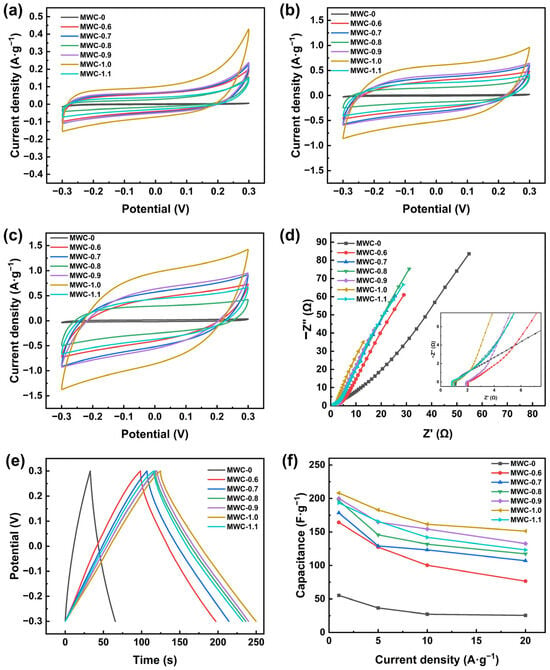

3.2.1. CV Test

Figure 4a–c show the CV curves of MWC electrodes at three scan rates (5, 50, and 100 mV·s−1). An approximately rectangular shape at three scan rates was maintained for the curves of electrodes, which demonstrated the typical double-layer capacitance characteristics [44]. Compared with MWC-0, the modified samples exhibited larger integral areas on CV curves, indicating superior capacitance performance. This phenomenon could be explained by the large surface area and well-structured multi-level pore distribution of the modified samples, which facilitated more adsorption sites. The Fe3O4 particles that adhered to the surface also contributed to the formation of these active sites. In addition, introducing functional groups onto the surface of MWC can significantly enhance its electrochemical performance. As the scan rate increases, a distortion phenomenon was observed for the CV curves. The main reason was that electrolyte ions were unable to diffuse rapidly enough into the micropores and mesopores of modified biochar materials, thereby preventing the formation of double-layer capacitance at high scan rates [45]. After modification, the CV curves maintained excellent symmetry, demonstrating the material’s superior adsorption–desorption performance. Among the three scan rates, the largest integral area was detected for the MWC-1.0 electrode compared to the other electrodes, demonstrating its superior capacitor performance.

Figure 4.

Electrochemical characterization of different MWC materials: (a) CV curves at 5 mV·s−1, (b) CV curves at 50 mV·s−1, (c) CV curves at 100 mV·s−1, (d) EIS curves, (e) GCD curves at 1 A·g−1, (f) specific capacitance at different current densities.

3.2.2. EIS Test

The EIS curves of the biochar electrodes are shown in Figure 4d. The slope in the low-frequency region and the radius of the arc in the high-frequency region of EIS curves represented the diffusion and charge transfer resistance of the electrodes, respectively [1]. The modified biochar exhibited a steeper slope compared to MWC-0, indicating that AFC acted as an activator to effectively reduce the diffusion resistance and enhance ion transport between the electrolyte and electrode surfaces. The arc radius was very small in the high-frequency region, suggesting that the modified biochar electrode material had low charge transfer resistance and strong ion exchange capacity with the electrolyte. These characteristics might be attributed to the high specific surface area and hydrophilic groups of MWC material. Among all electrodes, the MWC-1.0 electrode exhibits the steepest slope and lowest charge transfer resistance, indicating its optimal diffusion and ion transfer performance.

3.2.3. GCD Test

To evaluate the specific capacitance of biochar before and after modification with AFC, GCD tests were conducted on biochar electrodes at four current densities (1, 5, 10, and 20 A·g−1). Figure 4e shows the GCD curves at a current density of 1 A·g−1, and all biochar electrodes showed symmetrical triangle curves, demonstrating typical double-layer capacitance characteristics and excellent electrochemical charge–discharge reversibility [46]. The charge–discharge duration of AFC-modified biochar was significantly increased under the same condition, especially for the MWC-1.0 electrode, which had the longest duration at all four current densities. It demonstrated that the modified biochar had a higher specific capacitance.

Figure 4f shows the specific capacitance of MWC at different current densities by using Equation (1). A clear inverse correlation was revealed between the current density and specific capacitance of biochar. It resulted from the progressively higher resistance for ion migration into the biochar material as the current density increasing, leading to reduced surface charge storage on the biochar electrode and consequently lower specific capacitance of biochar [47]. With the impregnation concentration increasing (0–1.1 mol·L−1), the specific capacitance of AFC-modified biochar was increased first, reaching a maximum at an impregnation concentration of 1.0 mol·L−1. At current densities of 1, 5, 10, and 20 A·g−1, the specific capacitances were 208.2, 182.8, 161.5, and 151.3 F·g−1, respectively. It represented a 3- to 5-fold enhancement relative to unmodified biochar. The specific capacitance of modified biochar began to decrease as the AFC concentration exceeded 1 mol·L−1. These results aligned with the trends observed in the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms and CV tests described earlier. The specific capacitance of MWC-1.0 at 20 A·g−1 still remained 72.67% of that at 1 A·g−1, demonstrating exceptional retention and rate performance. MWC-1.0 exhibited the best electrochemical performance during electrochemical tests.

3.3. CDI Desalination Analysis

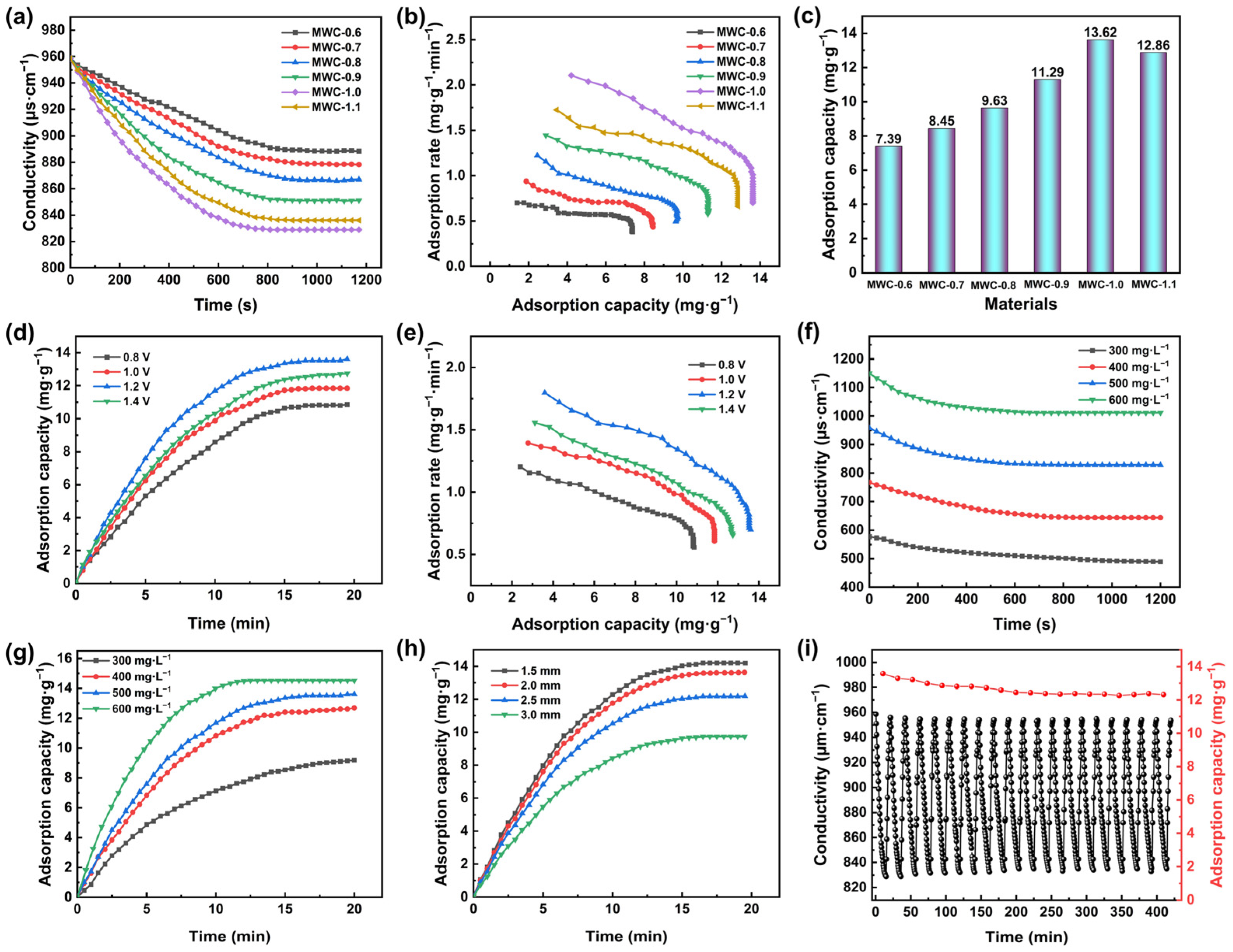

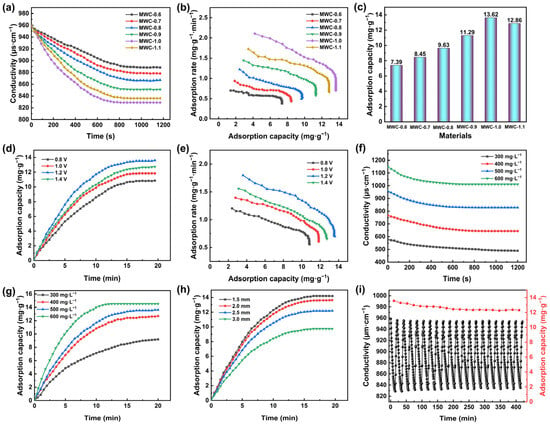

3.3.1. Effect of Different Electrodes on Desalination

Electrodes fabricated from different modified biochar materials were evaluated for desalination performance in a 500 mg·L−1 NaCl solution at 1.2 V with 2.0 mm electrode spacing. The solution conductivity is shown in Figure 5a. During the initial 10 min, the solution conductivity decreased rapidly, indicating the efficient removal of salt ions from the solution. The conductivity gradually plateaued, reaching an adsorption equilibrium state at 15 min. The highest salt adsorption capacity observed was 13.62 mg·g−1 for MWC-1.0 (Figure 5b,c). As the AFC concentration increased, the specific surface area and pore volume were enhanced, providing more access and active sites. However, when the AFC concentration reached 1.2 mol·L−1, the desalination performance of MWC-1.2 began to decline. This occurred because excessive Fe3O4 blocked the pore structure of biochar, reducing the specific surface area and consequently impairing its desalination performance. As shown in Figure 5b, the best adsorption capacity and rate are observed for MWC-1.0, corresponding to its most effective desalination performance.

Figure 5.

(a) Solution conductivity changes, (b) CDI Ragone plots, and (c) adsorption capacity of different electrodes in a 500 mg·L−1 NaCl solution at 1.2 V with 2.0 mm electrode spacing; (d) adsorption capacity and (e) CDI Ragone plots of MWC-1.0 electrode in a 500 mg·L−1 NaCl solution with 2.0 mm electrode spacing at different voltages; (f) solution conductivity changes and (g) adsorption capacity of MWC-1.0 electrode at 1.2 V with 2.0 mm electrode spacing in NaCl solutions of different concentrations; (h) adsorption capacity of MWC-1.0 electrode in a 500 mg·L−1 NaCl solution at 1.2 V with different electrode spacing; (i) cyclic regeneration test of MWC-1.0 electrode in a 500 mg·L−1 NaCl solution at 1.2 V with 2.0 mm electrode spacing.

3.3.2. Effect of Voltages on Desalination

In desalination experiments, voltage was a key factor influencing desalination efficiency [48]. Therefore, the performance of the MWC-1.0 electrode was examined from 0.8 to 1.4 V in a 500 mg·L−1 NaCl solution with 2.0 mm electrode spacing. As the voltage increased, the adsorption capacity reached values of 10.85, 11.84, 13.62, and 12.73 mg·g−1, respectively (Figure 5d). The results indicated that the desalination capacity of electrodes increased with rising voltage. However, the desalination capacity of the MWC-1.0 electrode declined under excessive voltage. This decline might be attributed to reduced adsorption efficiency caused by electrolysis reactions. Moreover, higher voltages could cause electrode material detachment, affecting its service life. Figure 5e shows that both the desalination capacity and rate of this electrode reach their maximum values at 1.2 V. Therefore, 1.2 V was determined as the optimal operating voltage for this experiment.

3.3.3. Effect of NaCl Concentrations on Desalination

Under 1.2 V applied potential and 2.0 mm electrode spacing, four different NaCl concentrations (300, 400, 500, and 600 mg·L−1) were employed for desalination tests. Figure 5f,g show the desalination process with adsorption capacities of 9.3, 12.94, 13.62, and 14.52 mg·g−1, respectively. As NaCl concentration rose, the salt adsorption capacity increased due to a higher ion density and strengthened electrostatic interactions. Additionally, elevated salt concentrations reduced the solution resistance, enhancing the current density under a constant voltage. This facilitated ion migration and capture, thereby accelerating adsorption kinetics. Although AFC-modified biochar exhibited an improved desalination capacity with rising salt concentrations, its charge transfer efficiency gradually decreased due to the influence of electrode saturation effects. To minimize the effects of variable interference, a standardized 500 mg·L−1 NaCl solution was maintained for subsequent experiments.

3.3.4. Effect of Electrode Spacing on Desalination

The distance between electrode plates directly influences the electric field strength, as the force is inversely proportional to the plate spacing. This electric field strength determines the electrostatic force acting on charged ions. Therefore, to investigate and optimize the electrode plate spacing, four different spacings from 1.5 to 3 mm were set in this work with all other conditions optimized. As the electrode spacing increased (Figure 5h), both the desalination capacity and rate decreased markedly, and the time to reach the adsorption equilibrium lengthened accordingly. This phenomenon occurred because, under the same voltage, increasing the electrode spacing reduced the electric field strength. This led to a weaker electric field, which hindered the migration of charged particles and thereby diminished the electrostatic adsorption capacity. When the electrode spacing was set to 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3 mm, the desalination capacities were 14.19, 13.62, 12.19, and 9.73 mg·g−1, respectively. However, excessively narrow spacing readily increased the risk of electrical shorts and blockages, which impaired the desalination process. To balance the desalination capacity with operational stability, the optimal electrode spacing for MWC in this classic capacitive deionization model was determined to be 2.0 mm.

3.3.5. Cyclic Regeneration Tests of CDI

The advantage of CDI technology lies in its ability to regenerate electrodes through cyclic regeneration by reversing the anode and the cathode of the DC power once the electrodes reach adsorption saturation. The cyclic regeneration tests of the MWC-1.0 electrode were conducted in a 500 mg·L−1 NaCl solution at 1.2 V with 2.0 mm electrode spacing (Figure 5i). At the start of the first test, the salt-solution conductivity was the highest. After each subsequent cycle, the conductivity consistently fell below the initial value, indicating that not all adsorbed charged particles were desorbed. This occurred because the initial adsorption process involved some physical adsorption. When desorption happened, some of the physically adsorbed charged particles remained trapped in electrode pores [32]. In subsequent cycles, the electrode primarily relied on double-layer effects for salt removal. After 10 complete adsorption/desorption cycles, the desalination capacity of the MWC-1.0 electrode was decreased from 13.62 to 12.45 mg·g−1, retaining 91.4% of the initial capacity. When the number of regeneration cycles reached 20, its desalination capacity was 12.32 mg·g−1. The retention capacity showed a slight decrease and tended toward stability, still maintaining 90.5% of its initial capacity. This demonstrated that the MWC-1.0 electrode possessed excellent desalination capacity and cyclic regeneration performance. Additionally, the desalination performance of MWC-1.0 was assessed in comparison to various reference materials (Table 2). The results indicated that the MWC-1.0 electrode exhibited an outstanding desalination capability, comparable to that of carbon nanofibers [49] and carbon nanotubes [50]. Although its adsorption capacity was slightly lower than that of some MOF-derived and MXene-derived materials, it still exhibited distinct advantages over other carbon-based materials.

Table 2.

Desalination performance of different materials.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a straightforward and low-cost method was employed in this work to prepare an MWC electrode modified via AFC. The Fe3O4 and a large number of hydrophilic functional groups were successfully introduced onto the biochar, improving the material’s physical and electrochemical behavior. Among these materials, MWC-1.0 exhibited the most outstanding performance, with a specific surface area of 321.27 m2·g−1 and a pore volume of 0.186 cm3·g−1. Its abundant mesopores provided pathways for ion transport. Furthermore, MWC-1.0 was demonstrated to possess excellent capacitive properties. Its specific capacitance reached 208.19 F·g−1 at 1 A·g−1. In desalination experiments, the MWC-1.0 electrode achieved a desalination capacity of 13.62 mg·g−1 (500 mg·L−1, 1.2 V, 2.0 mm). After 20 regeneration cycles, 90.5% of the adsorption capacity was still retained, fully demonstrating the excellent stability and regenerative performance. This work provides an economical, green, and highly efficient method for preparing capacitive deionization materials, offering valuable insights for future electrode material development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and P.W.; methodology, J.L. and J.W.; software, P.Z.; validation, J.L., P.W. and J.W.; formal analysis, C.Q.; investigation, H.T.; resources, S.L. and Y.W.; data curation, J.L., P.W. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L., S.M. and B.C.; visualization, J.L. and P.W.; supervision, S.L., S.M. and B.C.; project administration, S.L. and B.C.; funding acquisition, S.L. and B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Henan Province Key University-Enterprise Joint R&D Center for Renewable Energy Low-Carbon Conversion and Utilization (Grant No. 30804408), the Hundreds of Thousands Science and Education Service Action Fund Project of Henan Agricultural University (Grant No. 30804357), the Special Fund for Agro-Scientific Research in the Public Interest (Grant No. 201503135-10), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22408088), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023M741053), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (Grant No. GZC20230713).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial supports from the Henan Province Key University-Enterprise Joint R&D Center for Renewable Energy Low-Carbon Conversion and Utilization (Grant No. 30804408), the Hundreds of Thousands Science and Education Service Action Fund Project of Henan Agricultural University (Grant No. 30804357), the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (Grant No. 201503135-10), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22408088), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023M741053), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (Grant No. GZC20230713).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yifeng Wu was employed by the company Energy Research Institute Co., Ltd., Henan Academy of Sciences. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yao, C.; Hussain, T.; Hu, B.; Yang, J.; Liu, J. Mg-MOF-Derived hierarchical porous carbon fiber electrodes for efficient capacitive deionization. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2024, 967, 118495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J. Application of capacitive deionization in drinking water purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Liang, J.; Tang, W.; He, D.; Yan, M.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Tang, N.; Huang, M. Versatile applications of capacitive deionization (CDI)-based technologies. Desalination 2020, 482, 114390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wu, J.; Shi, S.Q.; Li, J.; Kim, K.-H. Advances in desalination technology and its environmental and economic assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 397, 136498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moossa, B.; Trivedi, P.; Saleem, H.; Zaidi, S.J. Desalination in the GCC countries—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khondoker, M.; Mandal, S.; Gurav, R.; Hwang, S. Freshwater Shortage, Salinity Increase, and Global Food Production: A Need for Sustainable Irrigation Water Desalination—A Scoping Review. Earth 2023, 4, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amshawee, S.; Yunus, M.Y.B.M.; Azoddein, A.A.M.; Hassell, D.G.; Dakhil, I.H.; Hasan, H.A. Electrodialysis desalination for water and wastewater: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.E.; Khalil, A.; Hilal, N. Emerging desalination technologies: Current status, challenges and future trends. Desalination 2021, 517, 115183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wang, Z.; Kim, M.; Yamauchi, Y.; Eichhorn, S.J.; Titirici, M.-M.; Deng, L. Unleashing the power of capacitive deionization: Advancing ion removal with biomass-derived porous carbonaceous electrodes. Nano Energy 2023, 117, 108914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, T.-H.; Yang, K.; Luo, L.; Hou, C.-H.; Ma, J. Stop-flow discharge operation aggravates spacer scaling in CDI treating brackish hard water. Desalination 2023, 552, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Boretti, A.; Castelletto, S. Mxene pseudocapacitive electrode material for capacitive deionization. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 134959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therese Angeles, A.; Park, J.; Ham, K.; Bong, S.; Lee, J. High-performance capacitive deionization electrodes through regulated electrodeposition of manganese oxide and nickel-manganese oxide/hydroxide onto activated carbon. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 280, 119873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, G.; Sun, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H. Biomass-derived N-doped porous carbon as electrode materials for Zn-air battery powered capacitive deionization. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Kong, F.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Jin, C. Carbon spheres derived from biomass residue via ultrasonic spray pyrolysis for supercapacitors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 219, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Luhasile, M.K.; Li, H.; Pan, Q.; Zheng, F.; Wang, Y. A novel layered activated carbon with rapid ion transport through chemical activation of chestnut inner shell for capacitive deionization. Desalination 2022, 531, 115685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Zhu, L. Nitrite desorption from activated carbon fiber during capacitive deionization (CDI) and membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI). Colloids Surf. A 2018, 559, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Meshot, E.R.; Taylor, A.D.; Hu, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Elimelech, M.; Plata, D.L. High-Performance Capacitive Deionization via Manganese Oxide-Coated, Vertically Aligned Carbon Nanotubes. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2018, 5, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.; Wang, F.; Miao, Z.; Che, N. Hydrophilic porous activated biochar with high specific surface area for efficient capacitive deionization. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, F.; Shao, Z. Biomass applied in supercapacitor energy storage devices. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 1943–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Wei, W.; Xie, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, R.; Chen, J.; Du, C. Nitrogen, sulfur co-doped hierarchically porous carbon from rape pollen as high-performance supercapacitor electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 311, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Song, P.; Liu, J.; Chen, D.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Xie, M.; Du, C. Facile synthesis of nitrogen self-doped hierarchical porous carbon derived from pine pollen via MgCO3 activation for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2019, 438, 227013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Allah, A.E.; Wang, C.; Tan, H.; Farghali, A.A.; Khedr, M.H.; Malgras, V.; Yang, T.; Yamauchi, Y. Capacitive deionization using nitrogen-doped mesostructured carbons for highly efficient brackish water desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 362, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Duan, W.; Peng, H.; Pan, B.; Xing, B. Functional Biochar and Its Balanced Design. ACS Environ. Au 2022, 2, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lv, F.; Yang, R.; Zhang, L.; Tao, W.; Liu, G.; Gao, H.; Guan, Y. N-Doped Biochar from Lignocellulosic Biomass for Preparation of Adsorbent: Characterization, Kinetics and Application. Polymers 2022, 14, 3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisadiki, J.; Jande, Y.A.C.; Machunda, R.L.; Kibona, T.E. Porous carbon derived from Artocarpus heterophyllus peels for capacitive deionization electrodes. Carbon 2019, 147, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui Tang, S.; Zaini Muhammad Abbas, A. Potassium hydroxide activation of activated carbon: A commentary. Carbon Lett. 2015, 16, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, W.; Tan, F.; Yu, B.; Cheng, G.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Z. Fe3O4@C-500 anode derived by commercial ammonium ferric citrate for advanced lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2023, 574, 233146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ji, X.; He, Z. Ti3C2Tx MXene@carbon dots hybrid microflowers as a binder-free electrode material toward high capacity capacitive deionization. Desalination 2023, 548, 116267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fang, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Maximized ion accessibility in the binder-free layer-by-layer MXene/CNT film prepared by the electrophoretic deposition for rapid hybrid capacitive deionization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 292, 121019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Xie, F.; Zhao, G.; Han, L.; Zhang, L.; Lu, T.; Amin, M.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Xu, X.; et al. Polyaniline coated MOF-derived Mn2O3 nanorods for efficient hybrid capacitive deionization. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Xu, R.; Bie, L.; Fahlman, B.D. Nitrogen-Deficient Graphitic Carbon Nitride with Enhanced Performance for Lithium Ion Battery Anodes. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 12650–12657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.; Lu, J.; Tian, L.; Liu, S.; Tahir, N.; Qing, C.; Tao, H. Environmental-friendly modification of porous biochar via K2FeO4 as a capacitive deionization electrode material. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, M.; Carotenuto, G.; De Nicola, S.; Camerlingo, C.; Ambrogi, V.; Carfagna, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Highly Intercalated Graphite Bisulfate. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.-L.; Zhang, X.; Miao, Y.-X.; Wen, M.-X.; Yan, W.-J.; Lu, P.; Wang, Z.-R.; Sun, Q. In-situ plantation of Fe3O4@C nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide nanosheet as high-performance anode for lithium/sodium-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 546, 149163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Gan, D. Effect of ligands of functional magnetic MOF-199 composite on thiophene removal from model oil. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 2979–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Qu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Sun, C.; Gao, P.; Zhu, C. Growth of Hollow Transition Metal (Fe, Co, Ni) Oxide Nanoparticles on Graphene Sheets through Kirkendall Effect as Anodes for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chem. A Eur. J. 2016, 22, 1638–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Cao, L.; Ok, Y.S.; Cao, X. Characterization and quantification of electron donating capacity and its structure dependence in biochar derived from three waste biomasses. Chemosphere 2018, 211, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindu Bhavani, D.; Manjunatha Kumara, K.S.; Padaki, M.; Nagaraju, D.H. Tuning the membrane surface charge: Zwitterionic functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles for molecular separation and their superior antifouling property. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.T.N.; Nguyen, H.A.; Pham, H.V.; Tran, T.N.; Ho, T.T.N.; Doan, T.L.H.; Le, V.H.; Nguyen, T.H. Electrosorption of Cu(II) and Zn(II) in Capacitive Deionization by KOH Activation Coconut-Shell Activated Carbon. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, L.; Xu, Q.; Tian, W.; Li, Z.; Kobayashi, N. Adsorption kinetics and mechanisms of copper ions on activated carbons derived from pinewood sawdust by fast H3PO4 activation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 7907–7915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; You, S.-J.; Chao, H.-P. Fast and efficient adsorption of methylene green 5 on activated carbon prepared from new chemical activation method. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, R.; Pant, D.; Malaviya, P. Engineered algal biochar for contaminant remediation and electrochemical applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, S.; Karimzadeh, M.; Kafshboran, H.R. Magnetically recoverable gold catalyst supported on PVim-Grafted Fe3O4@CQD composite for efficient nitroarene reduction in water. J. Organomet. Chem. 2026, 1044, 123941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; El-Kady, M.F.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, M.; Wang, H.; Dunn, B.; Kaner, R.B. Design and Mechanisms of Asymmetric Supercapacitors. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 9233–9280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephanie, H.; Mlsna, T.E.; Wipf, D.O. Functionalized biochar electrodes for asymmetrical capacitive deionization. Desalination 2021, 516, 115240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Yang, H.; Hou, H.; He, S.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Nitrogen, sulfur co-doped hierarchical carbon encapsulated in graphene with “sphere-in-layer” interconnection for high-performance supercapacitor. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 599, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Jin, C.; Choe, U.; Sheng, K. Green Synthesis of Nitrogen-doped Porous Carbon Derived from Rice Straw for High-performance Supercapacitor Application. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 8966–8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.K.; Abuelhamd, M.; Allam, N.K.; Shahat, A.; Ramadan, M.; Hassan, H.M.A. Eco-friendly facile synthesis of glucose–derived microporous carbon spheres electrodes with enhanced performance for water capacitive deionization. Desalination 2020, 477, 114278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, X.; Lu, T.; Sun, C.Q.; Pan, L. Phosphorus-doped 3D carbon nanofiber aerogels derived from bacterial-cellulose for highly-efficient capacitive deionization. Carbon 2018, 130, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Gao, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Lin, T. Highly efficient capacitive deionization electrodes from electro spun carbon nanofiber membrane containing reduced graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 135, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, S.; Luo, W.; Guo, N.; Wang, L.; Jia, D.; Zhao, Z.; Feng, S.; Jia, L. Enabling a Large Accessible Surface Area of a Pore-Designed Hydrophilic Carbon Nanofiber Fabric for Ultrahigh Capacitive Deionization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 49586–49595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Liao, J.; Lu, M.; Pan, H.; An, L. ZnCl2 activated electrospun carbon nanofiber for capacitive desalination. Desalination 2014, 344, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-P.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Gao, L.-X.; Zhang, D.-Q.; An, Z.-X. Lignin-derived carbon nanofibers with the micro-cracking structure for high-performance capacitive deionization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, J.; Khan, M.U. Grafting the Charged Functional Groups on Carbon Nanotubes for Improving the Efficiency and Stability of Capacitive Deionization Process. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 17617–17628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Ding, Z.; Meng, F.; Lu, T.; Pan, L. Ultra-durable and highly-efficient hybrid capacitive deionization by MXene confined MoS2 heterostructure. Desalination 2022, 528, 115616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ding, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, T.; Pan, L. Three-dimensional charge transfer pathway in close-packed nickel hexacyanoferrate−on−MXene nano-stacking for high-performance capacitive deionization. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.