Abstract

Ionic liquids (ILs) have attracted considerable attention for light olefin separation owing to their negligible vapor pressure, excellent thermal stability, and tunable molecular structures. However, their intrinsically high viscosity severely restricts gas diffusion, leading to poor mass-transfer efficiency and limited separation performance in bulk form. Herein, we report the develop a high-performance adsorbent by immobilizing a silver-functionalized ionic liquid within ordered mesoporous MCM-41 to overcome the diffusion limitations of bulk ILs. The IL@MCM-41 composites were prepared via an impregnation–evaporation strategy, and their mesostructural integrity and textural evolution were confirmed by XRD and N2 sorption analyses. Their C2H4/C2H6 separation performance was subsequently evaluated. The composite with a 70 wt% IL loading achieves a high C2H4 uptake of 25.68 mg/g and a C2H4/C2H6 selectivity of 15.59 in breakthrough experiments (298 K, 100 kPa). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy results are consistent with the presence of reversible Ag+–π interactions, which governs the selective adsorption of C2H4. Additionally, the composite exhibits excellent thermal stability (up to 570 K) and maintains stable separation performance over 10 adsorption–desorption cycles. These IL@MCM-41 composites have significant potential for designing sorbent materials for efficient olefin/paraffin separation applications.

1. Introduction

The separation of C2H4 and C2H6 is critically important in the petrochemical industry. C2H4 serves as a key feedstock for producing polyethylene, ethanol, ethylbenzene, dichloroethane, and ethylene oxide, and various other essential industrial chemicals [1,2]. C2H6, in addition to being a crucial precursor for ethylene cracking, is also used in the synthesis of acetic acid, halogenated hydrocarbons, and other high-value chemicals, thereby playing a pivotal role in modern petrochemical value chains [3,4]. However, separating C2H4 from C2H6 remains inherently challenging due to their remarkably similar molecular sizes, polarities, and boiling points [5]. Conventional separation techniques, including cryogenic distillation, membrane separation, and adsorption, each present significant limitations [6,7,8,9]. Cryogenic distillation is highly energy-intensive and requires substantial capital investment, which considerably restricts its industrial applicability [10,11]. Membrane-based methods often suffer from insufficient selectivity, a trade-off between flux and purity, and stability issues, making it difficult to obtain high-purity C2H4.

Compared with distillation and membrane-based processes, adsorption provides several distinct advantages for C2H4/C2H6 separation, including mild operating conditions, lower energy consumption, and tunable host–guest interactions. These features make adsorption a promising alternative for efficiently separating molecules with similar physical properties. As a result, the development of high-performance adsorbent materials capable of selectively distinguishing between C2H4 and C2H6 has become an active research focus in recent years. Wang et al. constructed a series of π-conjugated microporous polyaminal networks (PAN-P, PAN-NA and PAN-AN), where strengthened C–H···π interactions with C2H6 in ultramicropores (∼0.55–1.1 nm) led to a C2H6 uptake of 2.38 mmol/g and a C2H6/C2H4 IAST selectivity of 1.68 at 298 K and 1 bar, as well as a breakthrough selectivity of 2.70 for a C2H6/C2H4 = 5/95 mixture at 298 K [12]. Min et al. developed Ag-exchanged ZK-5 zeolites [Ag-ZK-5(II), Si/Al = 3.7], in which Ag+–π complexation with C2H4 inside KFI cages yielded an equilibrium C2H4/C2H6 selectivity of 2.54 at 298 K under vacuum-swing adsorption conditions and effective separation of a C2H4/C2H6/Ar (25:25:50 v/v/v) stream in breakthrough experiments at 298 K [13]. Chen et al. reported an Fe-based MOF MIL-142A, where stronger van der Waals interactions and higher adsorption heat for C2H6 over C2H4 enabled a C2H6 uptake of 3.8 mmol/g and a C2H6/C2H4 IAST selectivity of 1.5 at 298 K and 100 kPa, together with a dynamic selectivity of 1.8 for an equimolar C2H6/C2H4 mixture at 298 K and 1 atm [14]. Wang et al. synthesized a Ag-decorated Hf MOF NUS-6(Hf)-Ag, where Ag+ sites anchored by sulfonic acid groups form π*–d complexes with C2H4, giving a C2H4 uptake of 2.02 mmol/g at 298 K and 105.8 kPa and an IAST C2H4/C2H6 selectivity of 6.0 at 298 K and 100 kPa (106 at 1 kPa), as well as a co-adsorption selectivity of 4.4 for an equimolar C2H4/C2H6 mixture in breakthrough tests at 298 K and 1 atm with excellent cycling stability [15]. However, despite substantial progress in adsorbent design, the majority of reported materials continue to exhibit insufficient C2H4/C2H6 selectivity.

Ionic liquids (ILs) have attracted substantial attention for light olefin separations owing to their near-zero vapor pressure, excellent thermal stability, and highly tunable cation–anion structures [16,17,18]. ILs exhibit high gas solubility, and their affinity toward C2H4 can be finely tuned through the rational selection of cations and anions [19,20]. Silver-ion-mediated olefin/paraffin separation has also been demonstrated in liquid-phase-facilitated transport configurations. For example, aqueous AgNO3 solutions were employed in gas–liquid membrane contactors for C2H4/C2H6 separation, where the separation performance was strongly dependent on the Ag+ concentration and operating flow conditions, highlighting the effectiveness of reversible Ag+–olefin complexation [21]. Several IL-based systems have demonstrated substantial potential for C2H4/C2H6 separation. Ren et al. synthesized a silver salt-containing IL, where synergistic interactions between Ag+–π coordination and strong hydrogen bonding between ethylene glycol and BF4− significantly enhanced C2H4 uptake and selectivity, achieving a C2H4 solubility of 6.0 mol L−1 and a selectivity of 8.57 at 298.15 K and 1.0 bar [22]. Cheng et al. developed an Er3+-containing IL mixture ([Bmim][TFO]/Er(TFO)3 + DMF), where selective coordination between C2H4 and the 4f/5d vacant orbitals of Er3+ resulted in a selectivity of 10 and excellent cycling stability [23]. Xing et al. introduced dual-nitrile groups symmetrically on an imidazolium cation to obtain a dual-CN-functionalized IL, [(CP)2im][NTf2], where dipole–quadrupole interactions suppressed C2H6 solubility. Upon the addition of AgNTf2, the C2H4 selectivity increased to 10.7 [24]. Wu et al. prepared a protic imidazolium IL containing Ag+, [Bim]1.5[Ag(NTf2)2.5], where reversible π-complexation between Ag+ and C2H4 contributed to exceptional selectivity (41.2 at 303 K and 0.2 MPa) and high C2H4 solubility (1.86 mol C2H4 mol−1 Ag+) [25]. Despite these advantages, bulk ILs inherently suffer from high viscosity, which leads to the formation of thick liquid films, reduced gas–liquid interfacial area, and restricted molecular diffusion [26]. These factors collectively suppress mass-transfer efficiency and severely limit the practical separation performance of IL-based systems [27,28].

To overcome the mass-transfer limitations inherent to bulk ILs, researchers have increasingly explored immobilizing ILs onto porous solid matrices. Such porous supports—with high surface areas and well-defined pore architectures—can effectively disperse ILs, enlarge the gas–liquid interfacial area, and facilitate molecular diffusion. Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-modified mesoporous materials can generate highly polar microenvironments that significantly enhance gas adsorption capacity and selectivity [29]. Ionogel systems with low IL loadings have also shown rapid adsorption kinetics and excellent cyclic stability [30]. Recent computational and experimental studies have demonstrated that incorporating ionic liquids into porous frameworks (e.g., IL@MOFs) can effectively tune gas affinities and separation performance by combining the selective interactions of ILs with the transport advantages of porous materials [31]. From a theoretical standpoint, first-principles calculations have been extensively employed to elucidate gas–surface interactions in silica-based materials and to clarify how variations in local coordination environments and heteroatom incorporation influence adsorption energetics and electronic structures. For instance, density functional theory investigations on undoped and doped silica surfaces have demonstrated that gas adsorption and dopant incorporation can markedly modify adsorption strengths and the electronic density of states, thereby providing fundamental molecular-level insight into host–guest interactions [32]. Despite these promising advances, most reported systems remain focused on CO2 capture, whereas systematic investigations of IL-modified porous adsorbents for C2H4/C2H6 separation have not yet been reported. Moreover, direct mechanistic evidence—particularly regarding Ag+–π interactions under confined mesoporous environments—has yet to be comprehensively elucidated. MCM-41, a well-established mesoporous molecular sieve with a highly ordered two-dimensional hexagonal channel system and a large surface area [33,34], serves as an ideal host for IL immobilization.

Herein, we design and synthesize a series of silver-functionalized ionic liquid composites by immobilizing [Emim][BF4]/AgBF4 within the ordered mesoporous channels of MCM-41. The structural integrity, pore evolution, thermal stability, and chemical environments of the resulting IL@MCM-41 materials were systematically characterized using XRD, FTIR, N2 sorption, TGA, SEM/EDS, elemental analysis, and XPS. Furthermore, the influences of IL loading, temperature, pressure, and cycling on C2H4 and C2H6 adsorption were comprehensively investigated to elucidate the confined Ag+–π interaction mechanisms governing selectivity. This work demonstrates how mesoporous confinement and Ag+–π complexation synergistically improve ethylene capture, offering design principles for advanced ionic-liquid-based adsorbents for efficient C2H4/C2H6 separation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

MCM-41 molecular sieves were purchased from Tianjin Yuanli Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate ([Emim][BF4], 99%) was obtained from the Lanzhou Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Lanzhou, China). Silver tetrafluoroborate (AgBF4, 99%) and acetonitrile (analytical grade) were supplied by Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All gas samples were provided by Huizhou Southern Huayan Chemical Products Co., Ltd. (Huizhou, China).

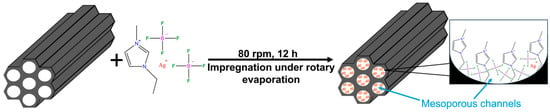

2.2. Preparation of IL@MCM-41 Composites

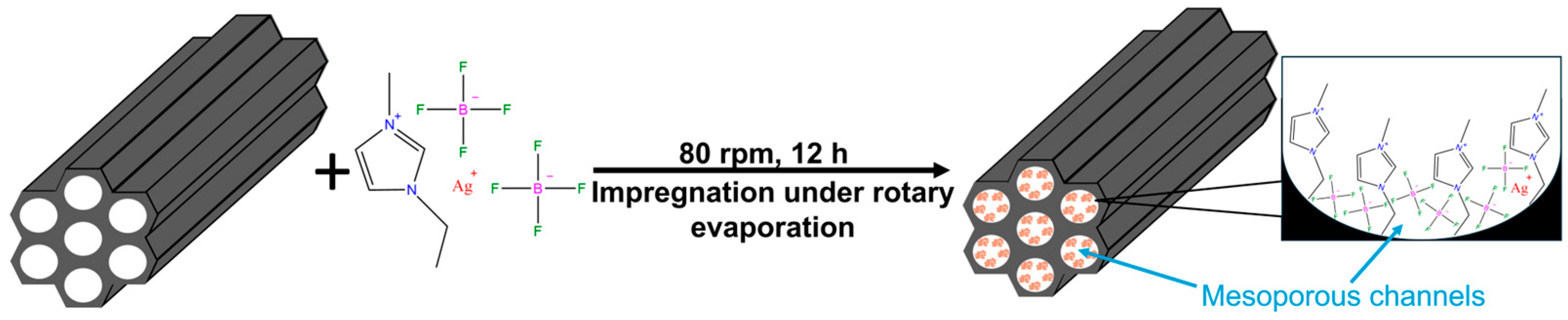

Silver-functionalized ionic liquid-loaded MCM-41 composites were prepared using an impregnation–evaporation method, as schematically illustrated in Figure 1. [Emim][BF4] was first dried under vacuum at 333.15 K for 12 h. The dried ionic liquid was then mixed with AgBF4 at a molar ratio of 4:1 and stirred at 298.15 K for 12 h to obtain the Ag+-containing ionic liquid [22,25]. The resulting ionic liquid was dissolved in 200 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile and magnetically stirred until a homogeneous solution was formed.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the impregnation–evaporation principle for IL@MCM-41 composites.

Separately, MCM-41 was dried at 120 °C to constant weight and subsequently added to the ionic-liquid solution to achieve IL loadings of 30–70 wt%. The suspension was stirred using a rotary evaporator (Zhengzhou Greatwall Scientific Industrial and Trade Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China) at 80 rpm for 12 h to facilitate infiltration of the ionic liquid into the mesoporous channels. After impregnation, acetonitrile was removed under reduced pressure at 358.15 K, followed by vacuum drying at 378.15 K for 24 h. The resulting samples were denoted as x wt% IL@MCM-41 (x = 30, 40, 50, 60, 70).

2.3. Characterization Methods of IL@MCM-41 Composites

All IL@MCM-41 samples were vacuum-dried at 333 K for 48 h prior to characterization. Small-angle X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed using a Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) over a 0.5–10° (2θ) range to evaluate pore ordering and mesostructural integrity. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured using an Autosorb-iQ-XR analyzer (Anton Paar QuantaTec Inc., Boynton Beach, FL, USA), and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method and density functional theory (DFT) were used to determine specific surface areas and pore-size distributions. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet iS50 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 to identify functional groups and confirm IL incorporation. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Mettler-Toledo AG, Greifensee, Zurich, Switzerland) was carried out under a N2 atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 K min−1 from room temperature to 1273 K to evaluate the thermal stability of the composites. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford Instruments plc, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK) were used to examine particle morphology and elemental distributions. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was performed to analyze chemical states and surface composition. Elemental analysis was conducted to determine the nitrogen content, enabling the calculation of actual IL loadings in the composites.

2.4. Determining Adsorption of Ethylene and Ethane on IL@MCM-41

Static adsorption isotherms of C2H4 and C2H6 were measured using an Autosorb-iQ-XR analyzer. Pure-component adsorption isotherms were measured volumetrically by stepwise dosing of gas to the desired pressure. The effect of temperature on C2H4 adsorption was investigated by varying the measurement temperature. High-pressure static adsorption measurements were performed using a quadrupole magnetic suspension balance over a pressure range of 1.0 × 102–1.9 × 103 kPa to investigate the pressure-dependent adsorption behavior.

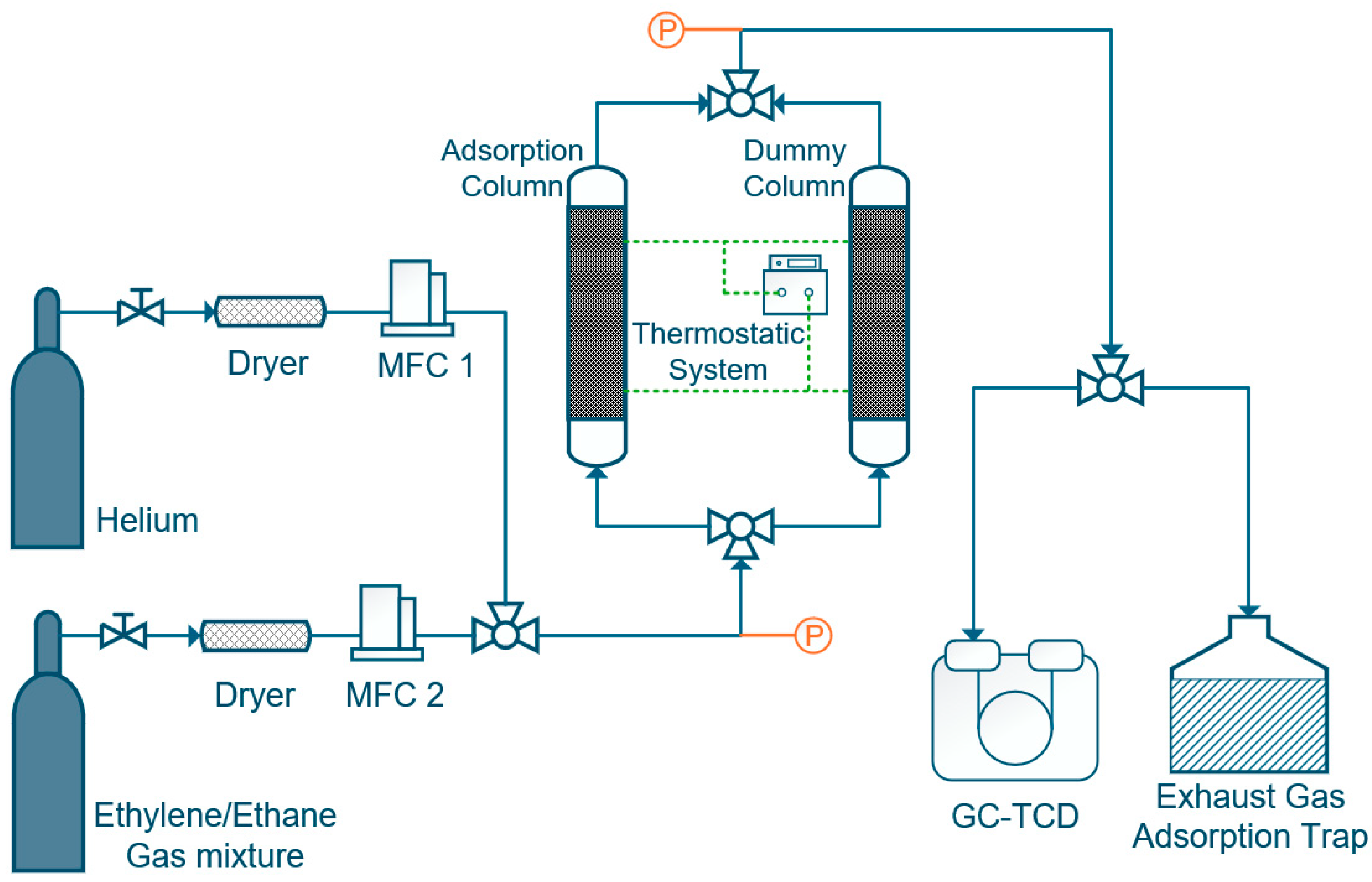

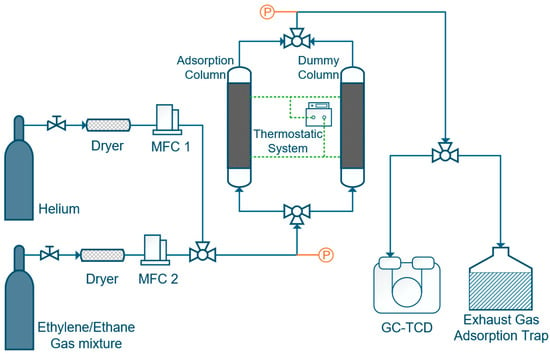

Dynamic breakthrough experiments were conducted using a custom-built fixed-bed setup (schematic shown in Figure 2). IL@MCM-41 samples were packed into a stainless-steel adsorption column with an inner diameter of 7 mm and a length of 200 mm, and tested at 298 K and ambient pressure. The feed gas mixture consisted of C2H4/C2H6 = 1.02/0.98 (v/v) and was introduced at a total flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. We first measured the system dead volume using blank breakthrough experiments with He as a non-adsorbing tracer (≈7.2–7.3 mL). We then used this value to correct the residence time in all breakthrough curves. This correction was applied before capacity calculations. The corresponding residence time was subtracted from all breakthrough curves prior to data analysis to ensure accurate evaluation of the adsorption capacity. Prior to each adsorption experiment, both the adsorption column and the dummy column were thoroughly purged with He until a stable baseline was obtained. Breakthrough curves were recorded upon switching the inlet gas from He to the C2H4/C2H6 mixture, and the outlet gas composition was continuously monitored using an Agilent 8890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a TCD detector.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the fixed-bed apparatus used for C2H4/C2H6 adsorption and separation. MFC denotes the mass flow controller. Dashed lines indicate the thermostatic system, and colors are used solely for schematic illustration.

The breakthrough time was defined as the point at which the outlet gas concentration reached 5% of the inlet concentration, while the saturation point was defined as 95% of the inlet concentration. After each run, the adsorbent was regenerated by purging with He. Five adsorption–desorption cycles were conducted for each sample to evaluate cyclic stability. In addition, the optimal 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 sample was further subjected to ten consecutive cycles. Adsorption capacities and selectivities were calculated from material balance relationships using the inlet and outlet gas compositions and flow rates, as expressed in Equations (1) and (2) [35]:

where ni is the equilibrium adsorption amount (mol); p1 and p2 are the inlet and outlet pressures (Pa); Vin and Vout are volumetric flow rates (m3/s); yi0 and yi are inlet and outlet volume fractions; V0 is the system dead volume (m3); R is the gas constant (8.314 J/mol/K−); and T is the temperature (K).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization and Properties of IL@MCM-41 Composites

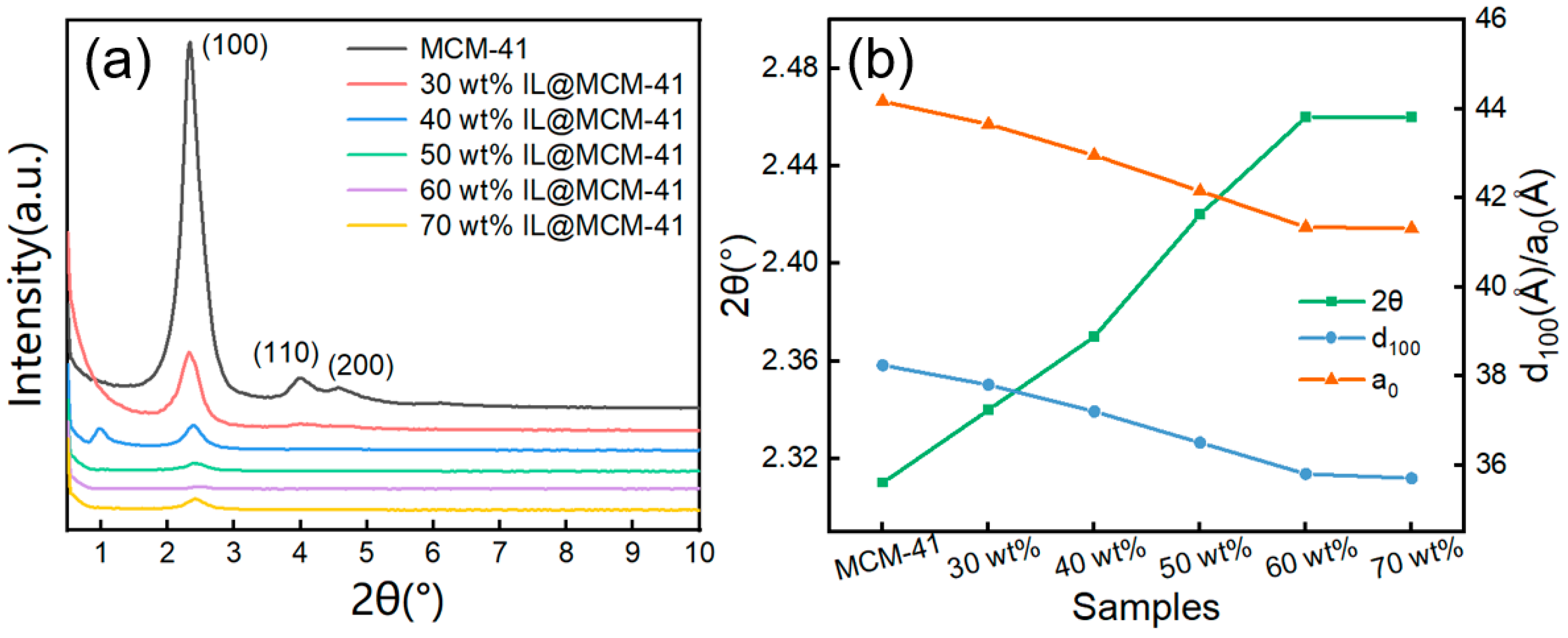

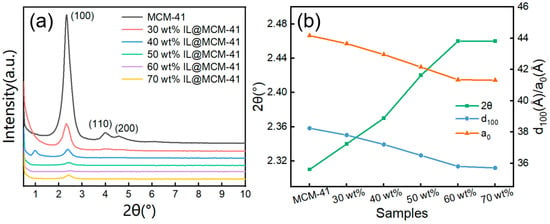

Small-angle XRD patterns of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites are shown in Figure 3. The parent MCM-41 exhibits a distinct (100) diffraction peak at 2θ ≈ 2.3°. This peak is a hallmark of a highly ordered 2D hexagonal mesostructure [33]. Upon incorporation of the ionic liquid, the intensity of the (100) reflection progressively decreases and the peak shifts slightly toward higher angles. Consequently, both the interplanar spacing (d100) and lattice parameter (a0) decrease with increasing IL loading. The shift in the (100) peak toward higher angles suggests partial penetration of the ionic liquid into the mesoporous channels, resulting in slight pore contraction. In the 40 wt% sample, a weak feature appears near 1°. We attribute it to a slight change in mesostructural ordering at intermediate IL loading. It is not due to crystalline impurities or phase separation [34,36,37]. Notably, the incorporation of ILs does not disrupt the periodicity of the mesoporous framework, indicating that the robust Si–O–Si network of MCM-41 effectively resists structural distortion even at high IL loadings [30,38].

Figure 3.

(a) Small-angle XRD patterns and (b) structural parameters of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites. Here, d100 refers to the interplanar spacing, and a0 denotes the lattice parameter.

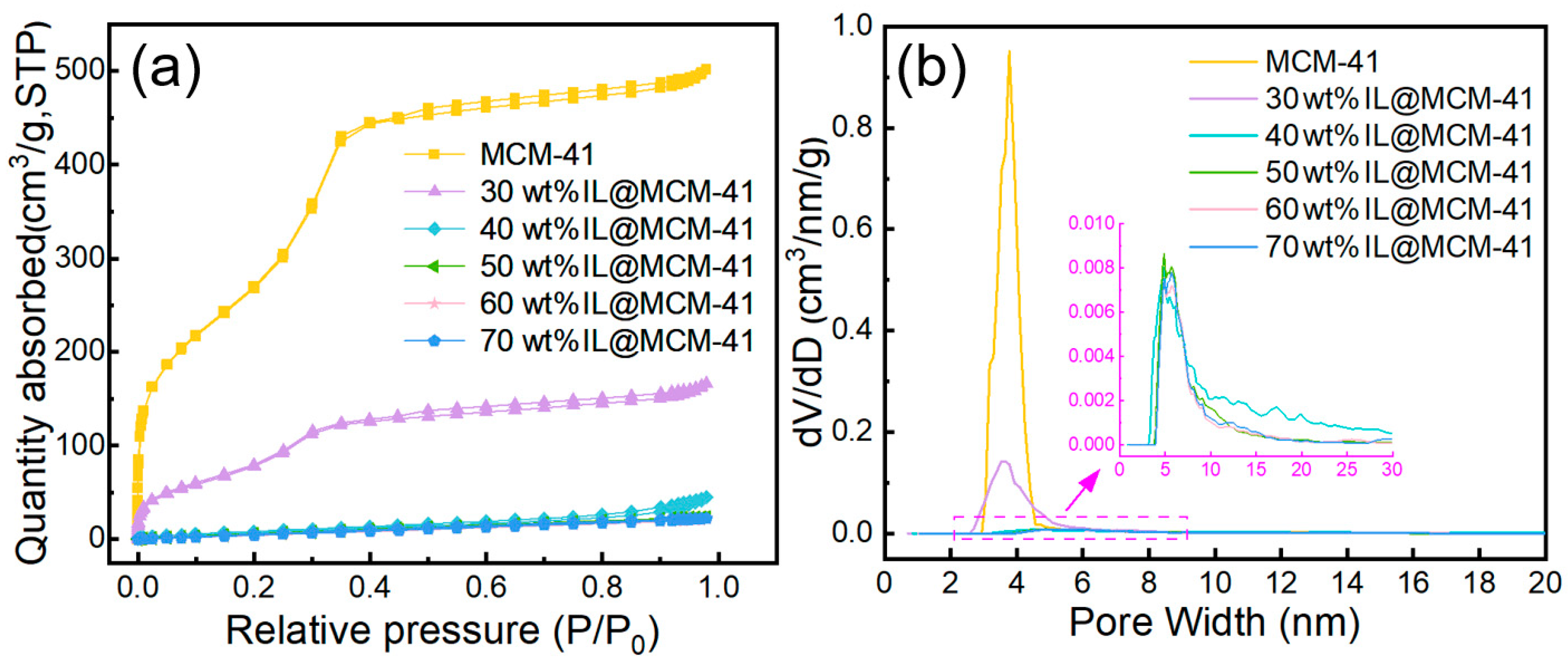

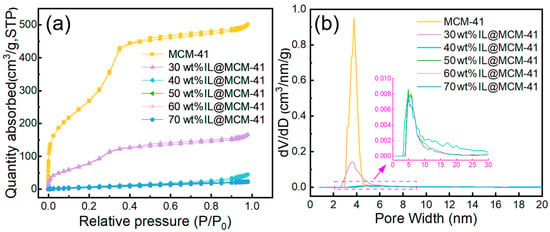

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore-size distributions (Figure 4) reveal substantial changes in the textural properties of the materials upon IL loading, with the corresponding quantitative parameters summarized in Table 1. Pristine MCM-41 exhibits a high BET surface area (1027.43 m2/g) and a large pore volume (0.78 cm3/g), consistent with typical mesoporous MCM-41 [39]. Its adsorption isotherm displays combined type I/IV features with a pronounced H1 hysteresis loop, indicative of a uniform mesoporous structure [40]. As the IL loading increases, both the BET surface area and pore volume decrease sharply—dropping to 299.15 m2/g at 30 wt% IL loading and further to approximately 33 m2/g at loadings ≥ 70 wt%. Correspondingly, the hysteresis loop nearly disappears and the pore-size distributions become significantly flattened, indicating that the IL progressively occupies the mesoporous channels. The BET surface area and pore volume decrease sharply with increasing IL loading. This trend suggests that the IL progressively occupies the mesopores and limits N2 access. The absence of a separate phase also implies good IL dispersion within the framework [41]. The progressive reduction in accessible pore volume indicates that a larger fraction of Ag+ sites becomes confined within narrower pore spaces, thereby increasing their effective accessibility to C2H4 molecules and contributing to the enhanced adsorption capacity.

Figure 4.

(a) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and (b) pore-size distributions of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites.

Table 1.

BET surface area and pore volume of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites.

Elemental analysis was employed to quantify the actual IL loadings in the IL@MCM-41 composites. Since pristine MCM-41 contains no nitrogen, whereas [Emim][BF4] contains nitrogen within the imidazolium cation, the nitrogen content detected in each composite directly reflects the amount of ionic liquid incorporated. Based on the measured nitrogen contents, the mass fractions of IL in the IL@MCM-41 composites were calculated, and the results are summarized in Table 2. For all samples, the experimentally determined IL loadings agreed well with the theoretical values, with deviations within 15%. This discrepancy is mainly attributed to a portion of the ionic liquid remaining adhered to the container walls.

Table 2.

Elemental analysis results of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites.

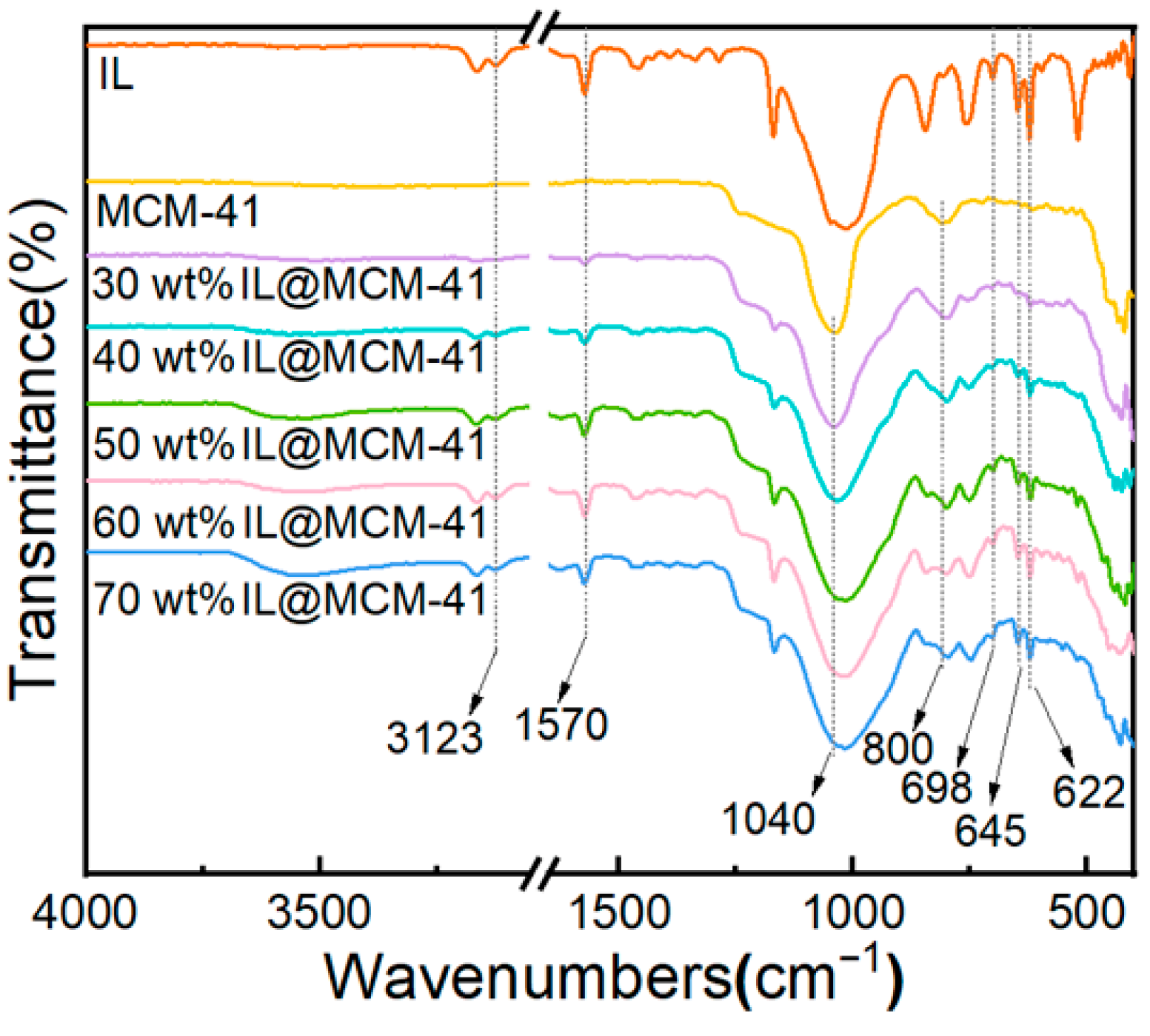

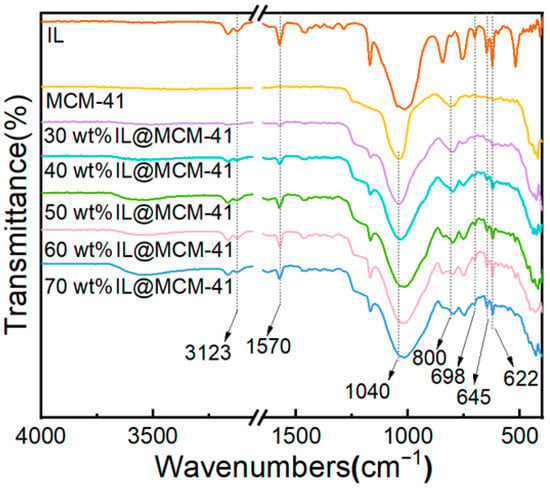

Figure 5 shows the FTIR spectra of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites. The IL@MCM-41 samples exhibit several characteristic absorption bands that are absent in pristine MCM-41, including B–F stretching vibrations at 698, 645, and 622 cm−1, as well as imidazolium ring C–H and C=N vibrations at 3123 and 1570 cm−1. Meanwhile, the Si–O–Si asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations at approximately 1040 and 800 cm−1 remain essentially unchanged, indicating that IL incorporation does not disrupt the silica framework [42]. No new peaks or significant peak shifts are observed, suggesting the absence of new chemical bonds between the ionic liquid and MCM-41; thus, the ionic liquid is primarily immobilized through physical loading rather than chemical interaction.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites.

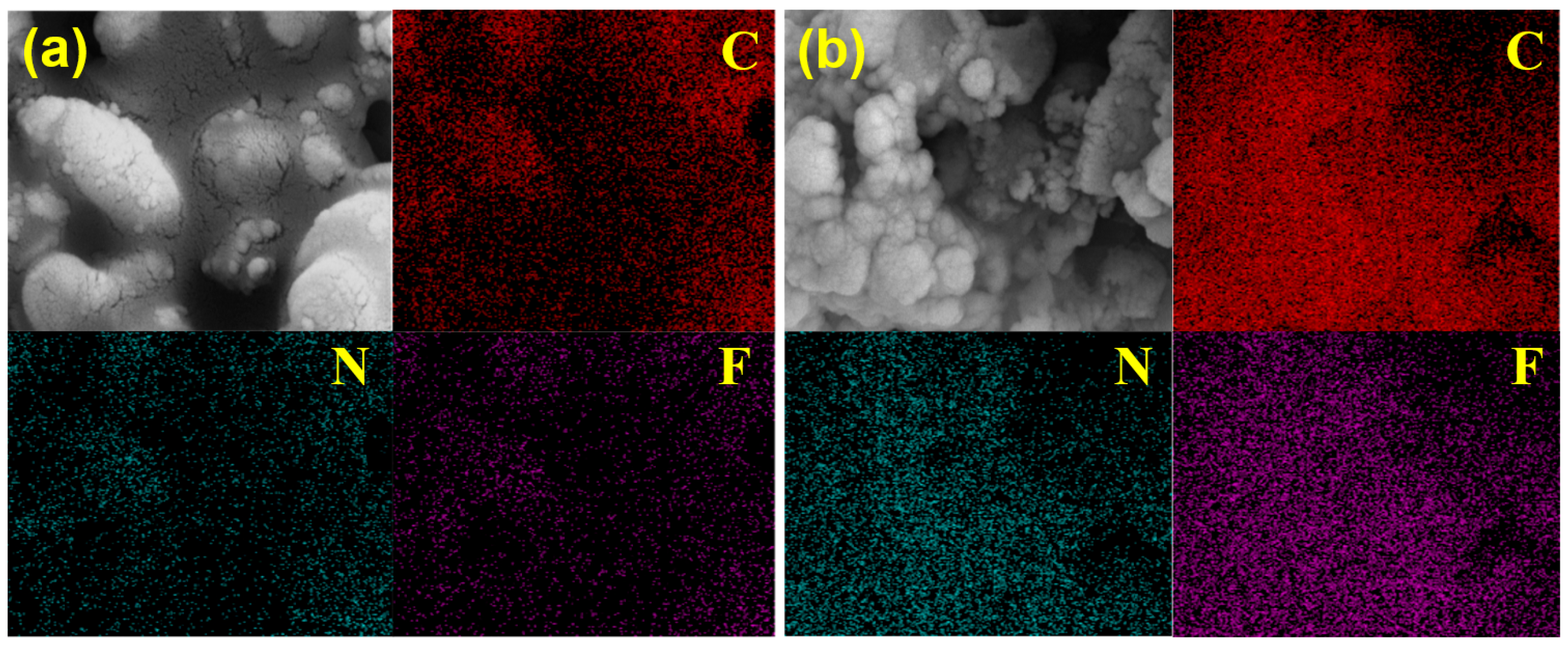

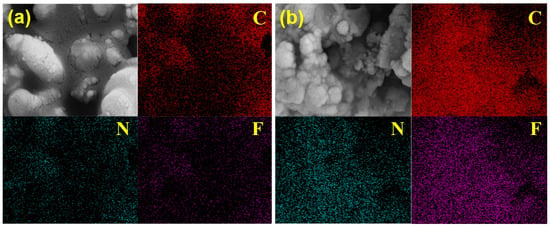

SEM images and EDS elemental mapping (Figure 6) reveal a homogeneous distribution of C, N, and F throughout the IL@MCM-41 composite. Compared with pristine MCM-41, the intensities of these elements are significantly enhanced after IL incorporation. The weak C, N, and F signals observed in pristine MCM-41 are mainly attributed to background contamination and instrumental noise inherent to EDS analysis of light elements. The uniform elemental distribution suggests that the ionic liquid is well dispersed within the mesoporous framework without obvious aggregation, which is beneficial for maintaining open diffusion pathways and enabling rapid access of C2H4 molecules to the active sites.

Figure 6.

EDS elemental mapping of (a) pristine MCM-41 and (b) the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite.

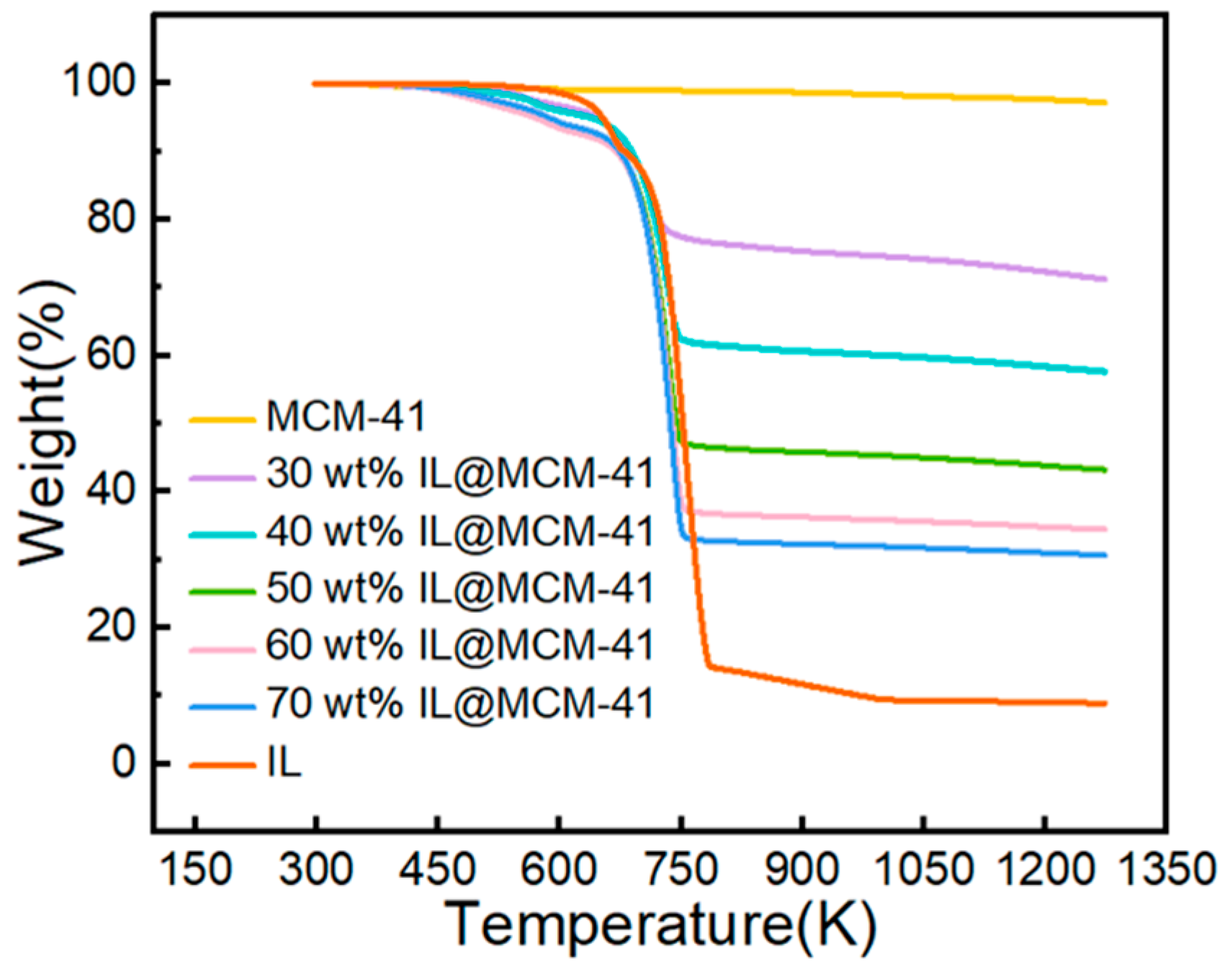

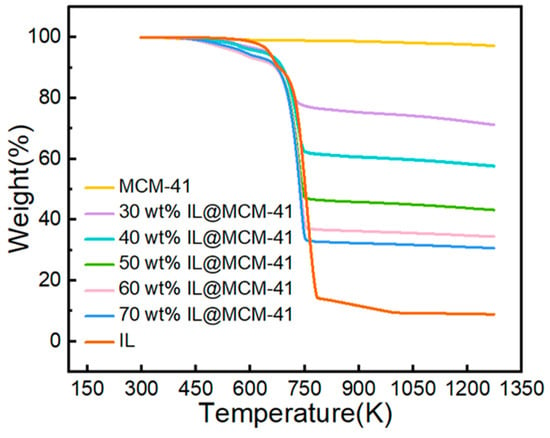

TGA curves (Figure 7) show that pristine MCM-41 undergoes minimal mass loss (~2.82%) from room temperature to 1273 K, which is primarily attributed to the desorption of physisorbed moisture. The IL@MCM-41 composites exhibit no significant mass loss below approximately 570 K, indicating that the silver-based ionic liquid is thermally stable within this temperature range and does not undergo noticeable decomposition or volatilization. Therefore, the composites meet the thermal requirements for adsorption–desorption cycling and are suitable for regenerable operation in practical gas-separation processes.

Figure 7.

TGA curves of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites.

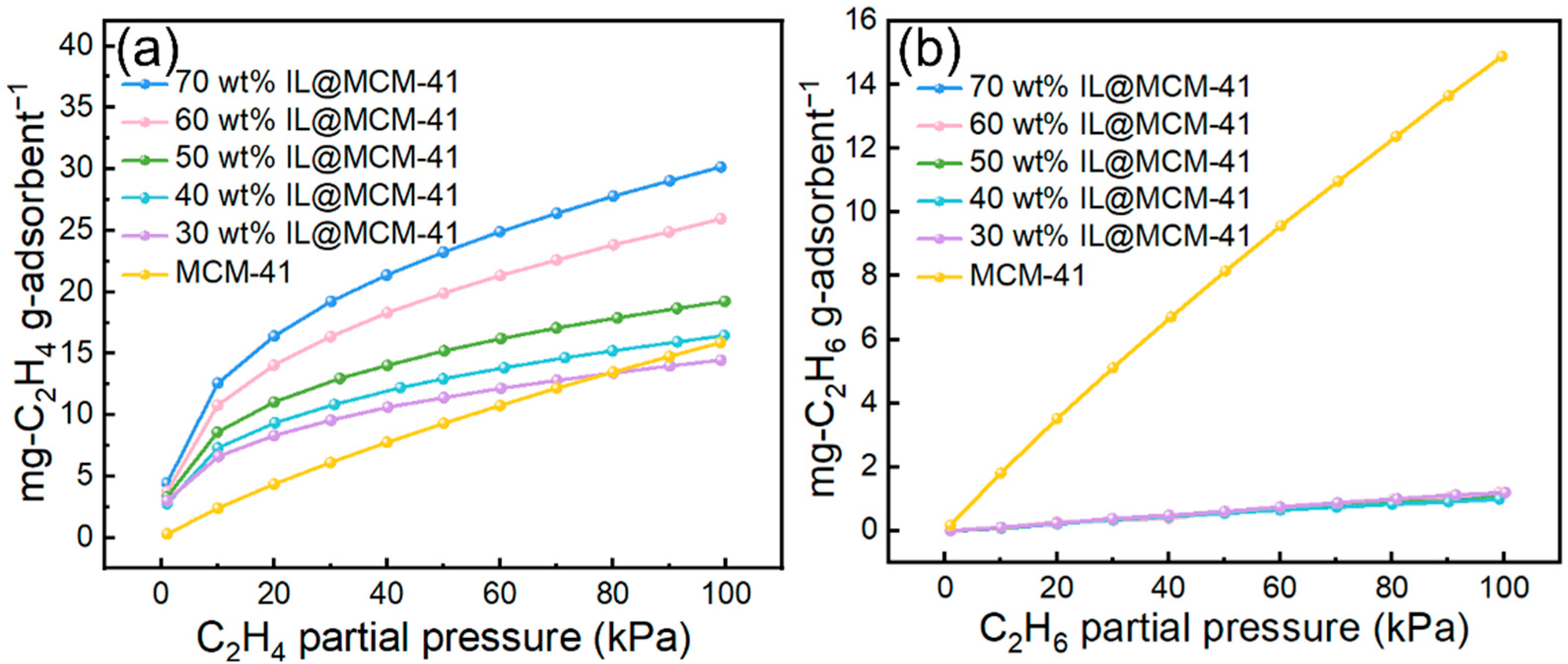

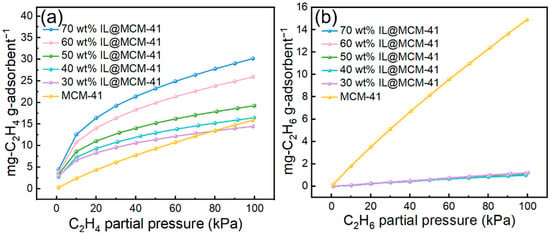

3.2. Effect of IL Loading and Partial Pressure on Adsorption Performance

Adsorption performance of C2H4 and C2H6 on pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites is shown in Figure 8. The C2H4 uptake increases substantially with increasing IL loading. At 100 kPa, the C2H4 adsorption capacity rises from 14.45 mg/g at 30.16 wt% IL loading to 30 mg/g at 70 wt%. In sharp contrast, C2H6 adsorption remains extremely low (1–2 mg/g), showing minimal dependence on IL loading and even falling below that of pristine MCM-41. This pronounced uptake disparity confirms a strong preferential adsorption of C2H4 relative to C2H6 in the IL-modified composites.

Figure 8.

Adsorption performance of C2H4 and C2H6 on pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites measured at 298 K under different gas partial pressures (0–100 kPa): (a) C2H4; (b) C2H6.

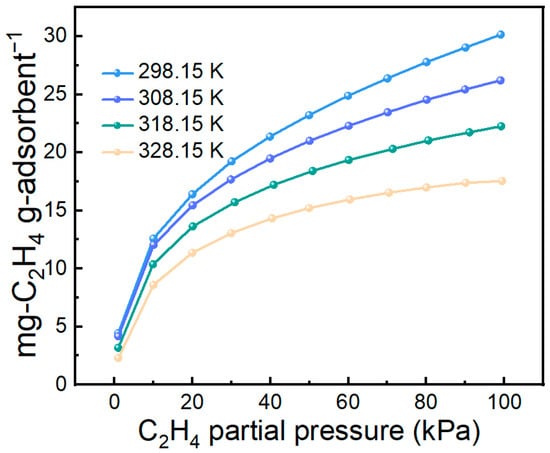

3.3. Effect of Temperature on Adsorption

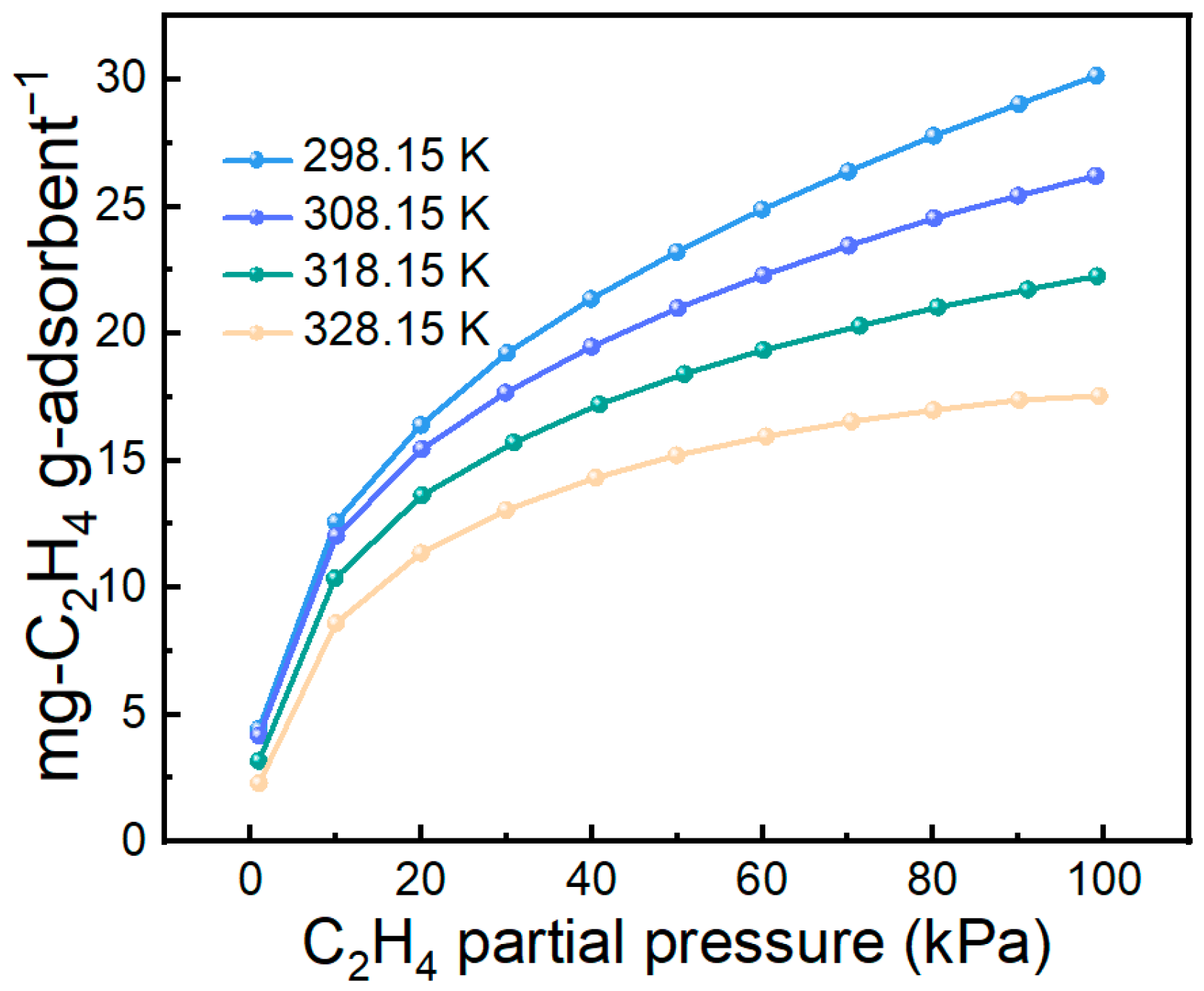

Adsorption temperature strongly influences practical separation performance. Therefore, the C2H4 adsorption performance of the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite was evaluated at different temperatures, as shown in Figure 9. The adsorption capacity increases as the temperature decreases; when the temperature is reduced from 328.15 K to 298.15 K, the C2H4 uptake rises from 17.55 mg/g to 30.16 mg/g. This trend indicates that lower temperatures are more favorable for ethylene adsorption, consistent with the typical behavior of exothermic adsorption processes.

Figure 9.

C2H4 adsorption on 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 at different temperatures under different gas partial pressures (0–100 kPa).

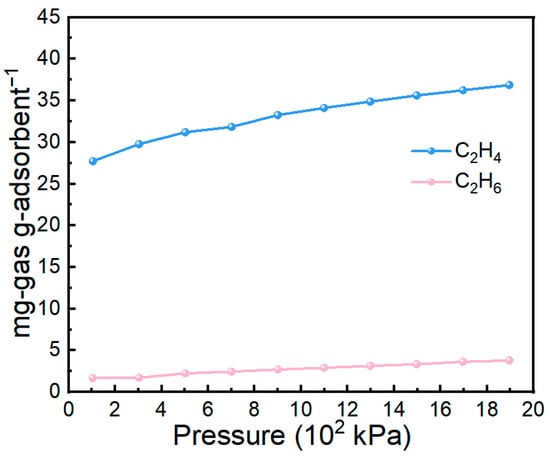

3.4. Effect of Pressure on Adsorption

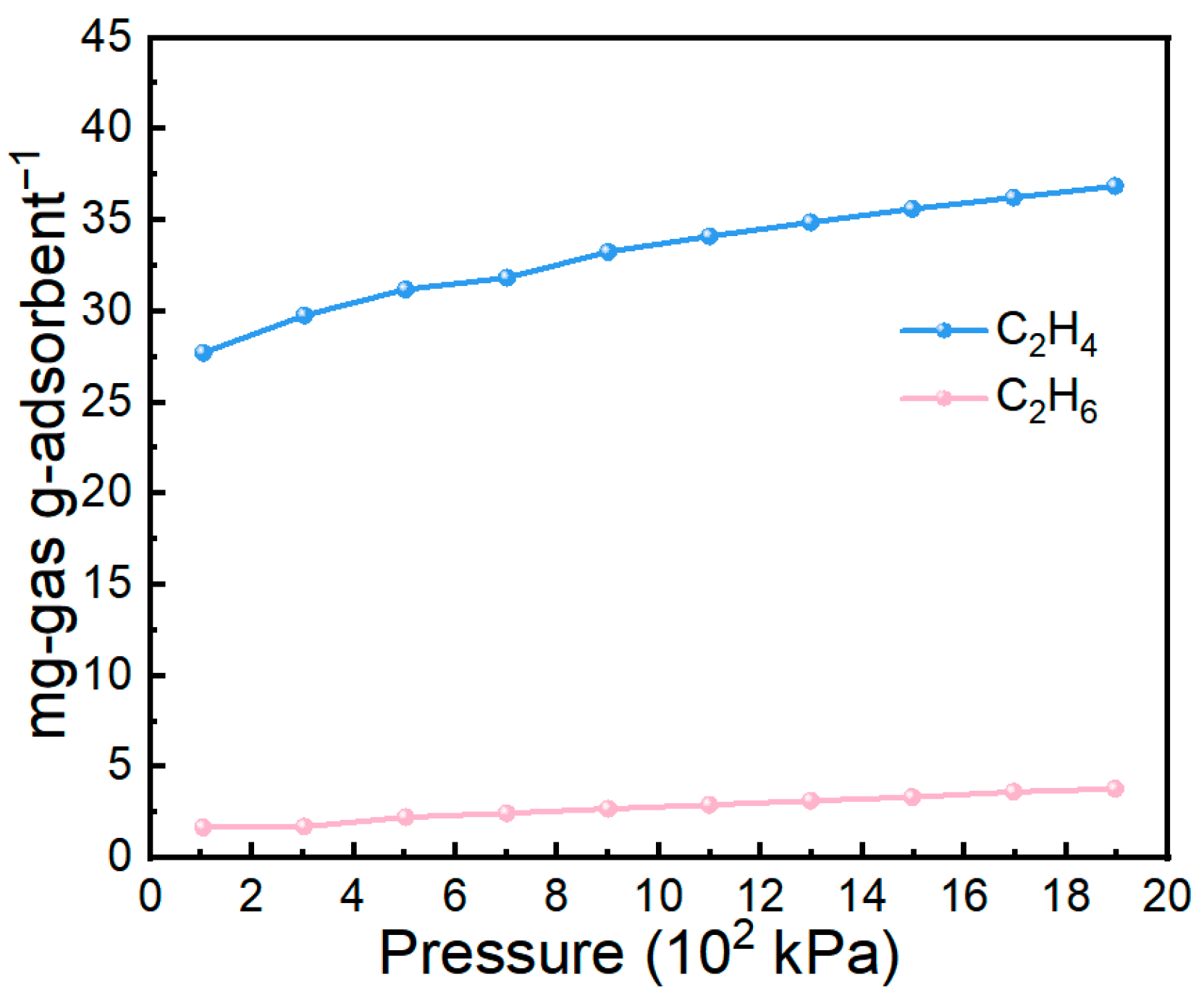

Pressure is another important parameter governing gas adsorption behavior. As shown in Figure 10, the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite was examined for C2H4 and C2H6 adsorption over a pressure range of 1–19 bar. The C2H4 uptake increases progressively with rising pressure, from 27.72 mg/g at 100 kPa to 36.87 mg/g at 1.9 × 103 kPa, without reaching a clear saturation limit. This monotonic increase indicates that additional adsorption sites remain available under elevated pressures. In contrast, C2H6 uptake remains consistently low across the entire pressure range, reflecting its weak interaction with the composite. Consequently, the disparity between C2H4 and C2H6 uptakes widens with increasing pressure, clearly showing that higher pressures further reinforce the preferential adsorption of C2H4.

Figure 10.

Comparison of C2H4 and C2H6 adsorption on 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 at different pressures at 298 K.

3.5. Adsorption Mechanism of IL@MCM-41 Composites

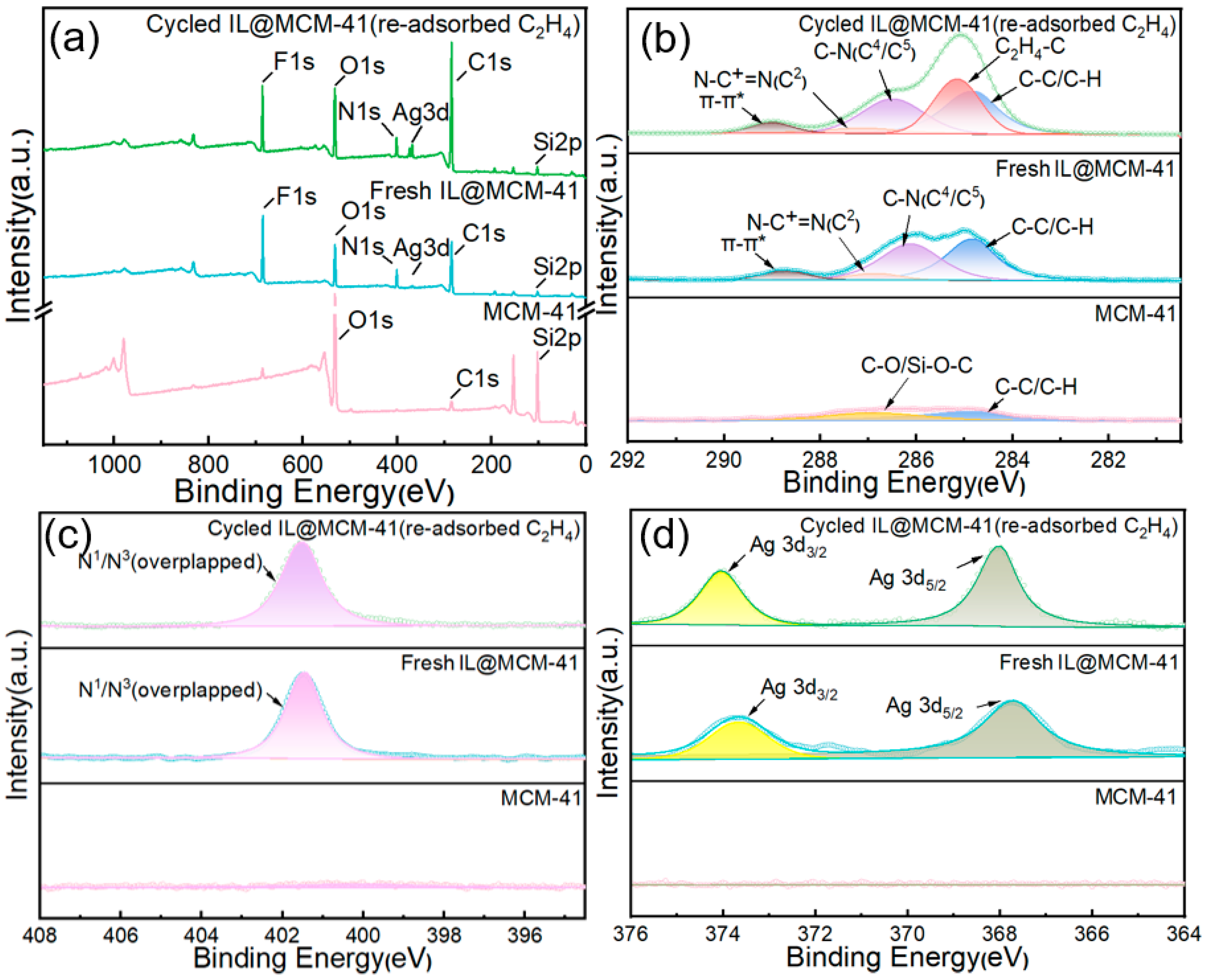

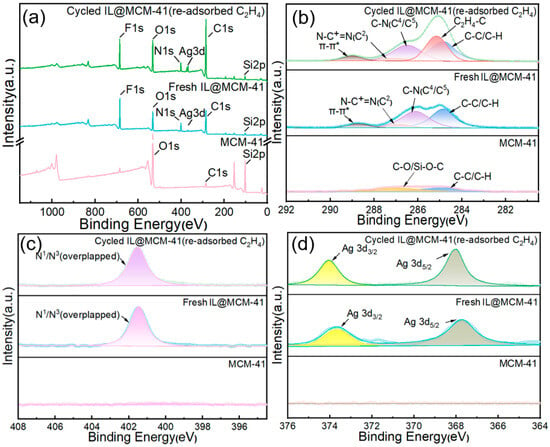

The XPS spectra were employed to probe the chemical states of the adsorbent and to evaluate whether the Ag+–π interaction with C2H4 remains operative after repeated adsorption–desorption cycling.

Compared with pristine MCM-41, the fresh IL@MCM-41 composite (before cycling) exhibits clear N 1s, F 1s, and Ag 3d signals, along with an intensified C 1s peak originating from the ionic liquid [43]. After adsorption–desorption cycles, the regenerated IL@MCM-41 sample was intentionally re-exposed to C2H4 prior to XPS analysis in order to examine whether the Ag+–π interaction remains active after cycling. As shown in Figure 11, the C 1s spectrum of the cycled and re-adsorbed sample exhibits a distinct shoulder at 285.14 eV, which can be assigned to C=C (sp2) species, confirming that C2H4 can still be effectively adsorbed after prolonged cyclic operation [44]. Meanwhile, the C–N-related peaks shift positively by approximately +0.3 eV, indicating a reduction in local electron density due to interaction with Ag+ centers; the N+ feature at 401.4 eV also exhibits a slight positive shift of +0.07 eV, consistent with cation–π interactions. In addition, the Ag 3d5/2 peak shifts from 368.52 eV (fresh IL@MCM-41) to 368.81 eV after re-adsorption of C2H4 on the cycled sample, providing direct evidence that Ag+–π coordination remains reversible and chemically stable even after repeated cycling. No signal attributable to metallic Ag0 is detected, demonstrating that Ag+ remains unreduced throughout both the synthesis and adsorption processes [45].

Figure 11.

XPS spectra of pristine MCM-41, fresh 70 wt% IL@MCM-41, and cycled 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 after re-adsorption of C2H4 following multiple adsorption–desorption cycles: (a) survey spectra; (b) high-resolution C 1s spectra; (c) high-resolution N 1s spectra; and (d) high-resolution Ag 3d spectra.

These XPS results conclusively confirm that reversible π-complexation between Ag+ and C2H4 is the dominant interaction governing the high C2H4/C2H6 selectivity of the IL@MCM-41 composites, while also verifying the chemical stability of Ag+ under adsorption–desorption cycling conditions. The strengthened Ag+–π interaction can be partly attributed to the confinement of the ionic liquid within the mesoporous channels of MCM-41, which promotes IL dispersion, enhances the accessibility of Ag+ sites, and brings ethylene molecules into closer proximity with the active centers. Such confinement-induced enhancement of metal–guest interactions has been widely observed in porous host–ionic liquid systems, supporting the view that the ordered mesopores cooperatively contribute to the improved ethylene affinity [46,47]. The presence of C=C-related signals in the cycled sample arises from deliberate re-adsorption of C2H4 prior to XPS measurement, rather than from incomplete regeneration, indicating preserved adsorption functionality and excellent reversibility of the Ag+ sites.

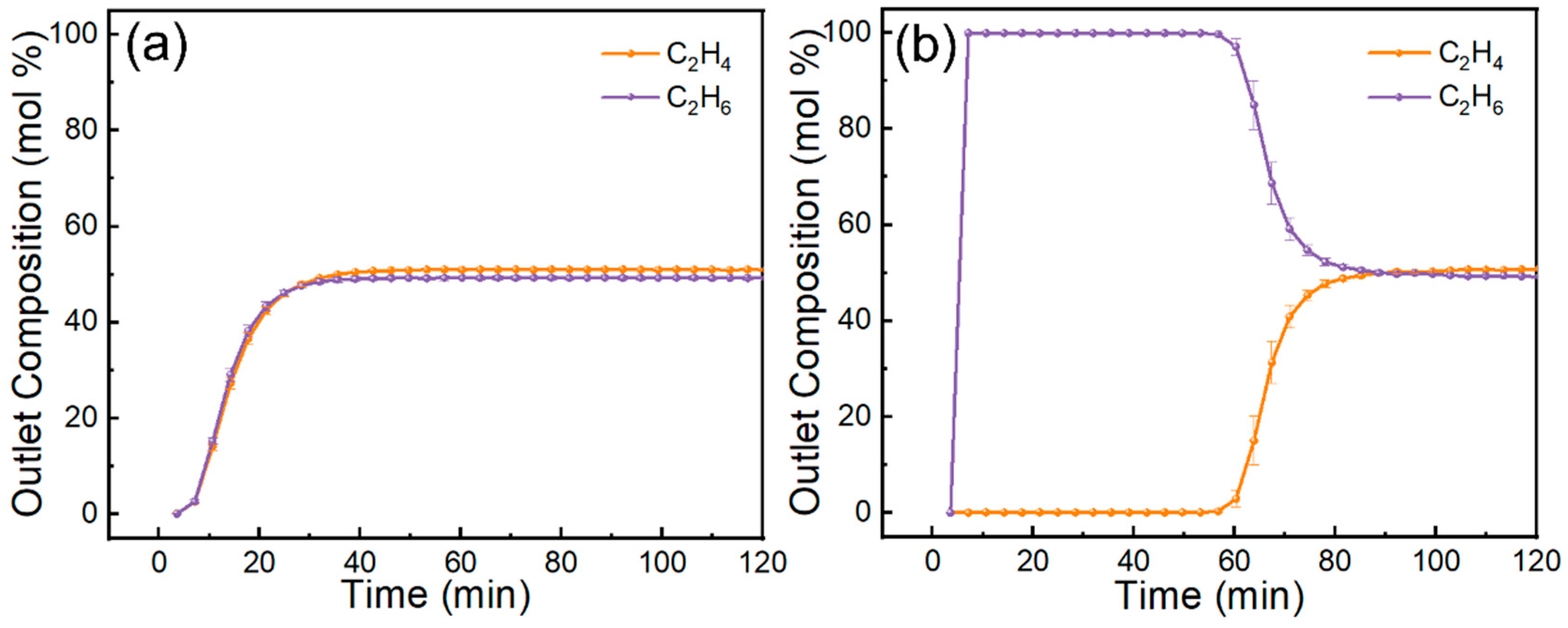

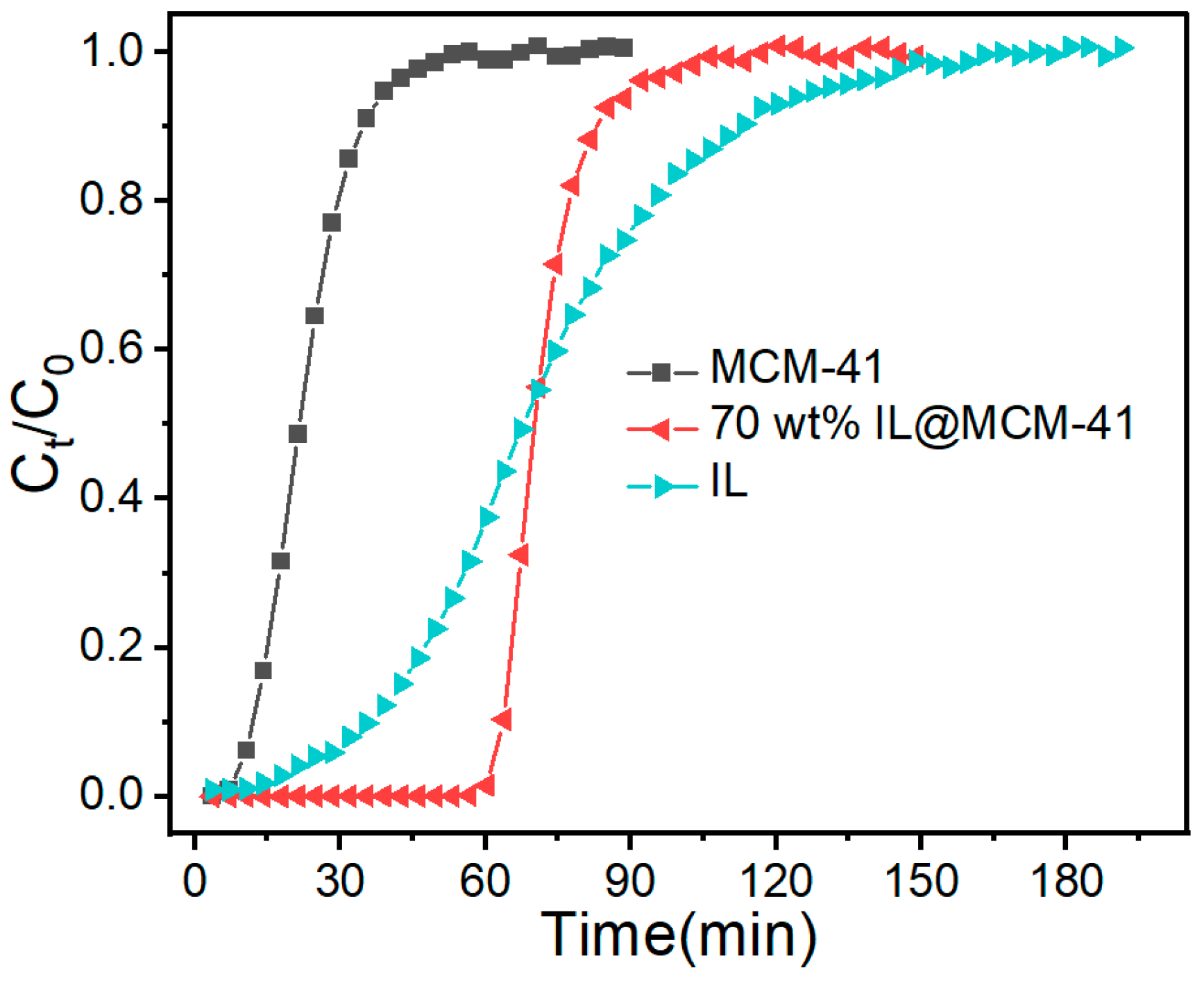

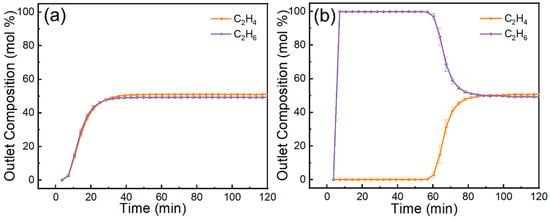

3.6. Breakthrough Dynamics and Mass-Transfer Characteristics

Dynamic breakthrough curves (Figure 12) clearly highlight the stark contrast between pristine MCM-41 and the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite. Pristine MCM-41 shows nearly overlapping breakthrough profiles for C2H4 and C2H6, indicating negligible separation capability. In contrast, the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite exhibits a pronounced C2H4 breakthrough delay exceeding 60 min, whereas C2H6 breaks through rapidly. We attribute this behavior to three factors. First, Ag+ forms π-complexes with C2H4. Second, the composite shows minimal affinity for C2H6. Third, confining the IL in mesopores improves mass transfer and reduces diffusion resistance [25].

Figure 12.

Breakthrough curves of C2H4/C2H6 mixtures on (a) pristine MCM-41 and (b) 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 at 298 K and 100 kPa (feed molar ratio C2H4/C2H6 = 1.02/0.98).

The breakthrough behaviors of C2H4 over pristine MCM-41, the bulk ionic liquid, and the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite are presented in Figure 13. Pristine MCM-41 shows an early breakthrough and a very sharp adsorption front, indicative of rapid intraparticle diffusion but weak physisorption interactions, which together result in a low equilibrium uptake. In contrast, the column packed with the bulk [Emim][BF4]/AgBF4 ionic liquid exhibits a markedly broader mass-transfer zone and a gradual increase in Ct/C0. This broadening reflects the strong Ag+–π interactions toward C2H4 as well as the substantial diffusional resistance imposed by the high viscosity of the liquid phase and the limited gas–liquid interfacial area.

Figure 13.

Breakthrough curves of C2H4 over MCM-41, 70 wt% IL@MCM-41, and bulk IL measured at 298 K and 100 kPa.

Notably, the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite displays a delayed breakthrough compared with pristine MCM-41 but a significantly steeper breakthrough front than the bulk ionic liquid. This behavior demonstrates that confining the Ag+-functionalized ionic liquid within the mesoporous channels appreciably enhances overall mass-transfer efficiency while preserving high-affinity adsorption sites for C2H4. The much narrower mass-transfer zone relative to the bulk IL confirms that the mesoporous framework provides shortened diffusion pathways and an enlarged accessible interfacial area, thereby enabling faster transport of C2H4 molecules toward Ag+ active centers.

To further clarify the mass-transfer behavior observed in the breakthrough experiments, the normalized breakthrough curves of bulk ionic liquid, pristine MCM-41, and IL@MCM-41 composites with different ionic-liquid loadings were analyzed using the Clark model (Figure S1). The corresponding kinetic parameters are summarized in Table S1. This normalized analysis reduces the influence of absolute uptake capacity and allows a clearer comparison of mass-transfer efficiency. The results show that the mass-transfer efficiency of IL@MCM-41 composites first increases and then decreases as the ionic-liquid loading increases. This trend reflects enhanced gas–sorbent interactions at low loadings and increased diffusion resistance caused by partial pore blocking at higher loadings. It should be noted that the Clark model is mainly applicable to adsorption-dominated systems. Therefore, the comparison involving bulk ionic liquid is discussed only in a qualitative manner.

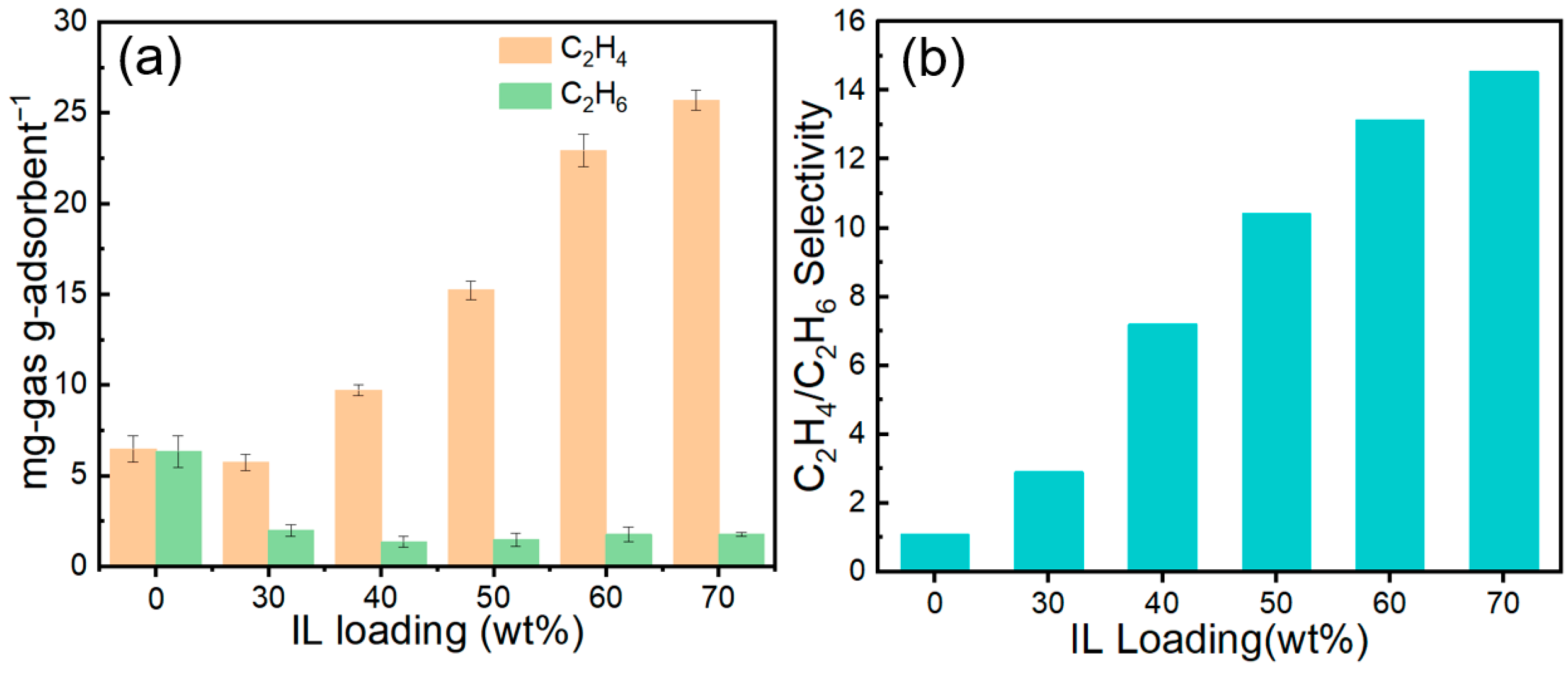

3.7. Effect of IL Loading on Mixed-Gas Adsorption Performance

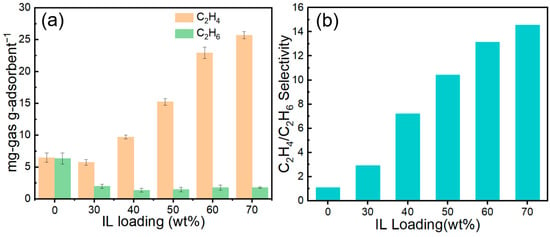

Figure 14 shows the C2H4 and C2H6 capacities, together with the corresponding selectivities, of the adsorbents at various IL loadings. As illustrated, increasing the IL content markedly enhances the C2H4 uptake—from 6.47 mg/g at 0 wt% to 25.68 mg/g at 70 wt%—whereas the C2H6 uptake decreases slightly. As a result, the C2H4/C2H6 selectivity rises sharply from 1.10 to 15.59. Notably, the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite exhibits a markedly enhanced dynamic separation performance compared with the bulk ionic liquid, as evidenced by its steeper breakthrough front, narrower mass-transfer zone, and substantially higher C2H4/C2H6 selectivity under identical breakthrough conditions. This result highlights the critical role of mesoporous confinement in improving mass-transfer efficiency while preserving strong Ag+–C2H4 interactions [22].

Figure 14.

(a) Adsorption capacities and (b) C2H4/C2H6 selectivities of pristine MCM-41 and IL@MCM-41 composites at 298 K and 100 kPa (feed molar ratio = 1.02/0.98).

3.8. Comparison of Adsorption Performance

Comparison with previously reported adsorbents (Table 3) further highlights the superior separation performance of the IL@MCM-41 composites. Most conventional adsorbents exhibit selectivities below 7.6 under comparable conditions, whereas the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite achieves a substantially higher selectivity of 15.59. This performance advantage demonstrates the effectiveness of integrating Ag+-functionalized ionic liquids with ordered mesoporous supports, providing a more efficient separation strategy than conventional physisorbents.

Table 3.

Comparison of the C2H4/C2H6 separation performance of the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite with previously reported adsorbents.

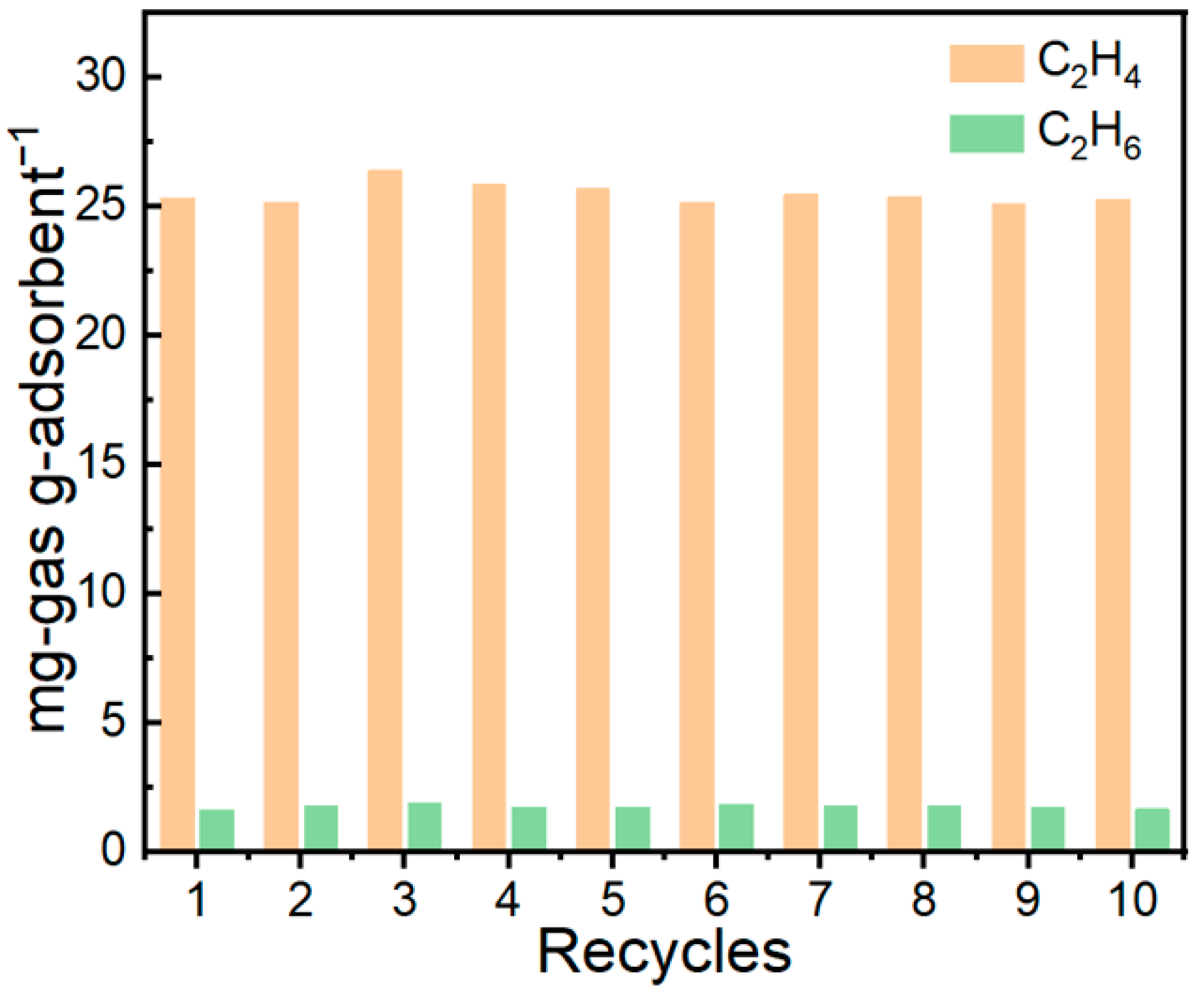

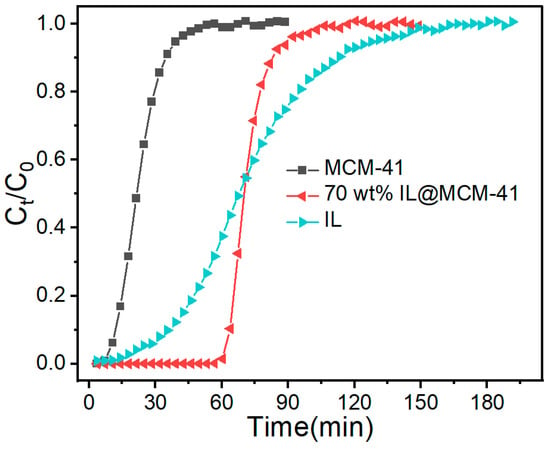

3.9. Cyclic Stability

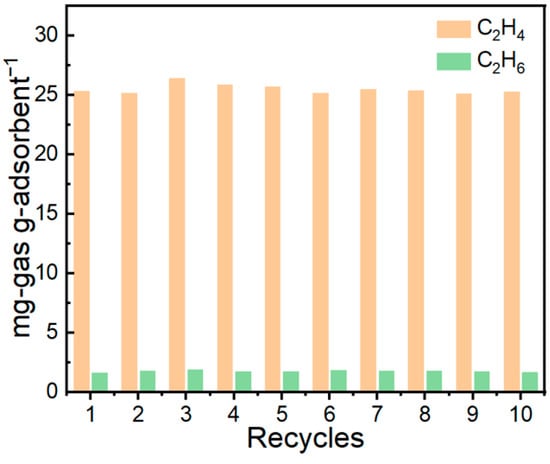

Cyclic adsorption–desorption measurements (Figure 15) demonstrate that the IL@MCM-41 composite possesses excellent operational stability. After ten consecutive cycles, the material retains essentially unchanged adsorption performance, maintaining a C2H4 uptake of 25.47 mg/g, a C2H6 uptake of 1.77 mg/g, and a C2H4/C2H6 selectivity of approximately 15.43. The negligible variation across cycles confirms the robustness of the Ag+ active sites, the stable distribution of the ionic liquid within the mesoporous channels, and the outstanding regenerability of the composite under repeated adsorption–desorption operation.

Figure 15.

C2H4/C2H6 adsorption–desorption cycling performance of the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 composite. Experimental conditions: 298 K, 100 kPa; feed molar ratio C2H4/C2H6 = 1.02/0.98.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a series of silver-based ionic liquid-modified MCM-41 composites were synthesized using [Emim][BF4]/AgBF4 as the functional phase, and their structural evolution, adsorption properties, and C2H4/C2H6 separation performance were systematically investigated. At an IL loading of 70 wt%, the composite exhibited outstanding performance at 298 K and 100 kPa, achieving a C2H4 uptake of 25.68 mg/g and a C2H4/C2H6 selectivity of 15.59, significantly surpassing most reported adsorbents. Compared with the bulk ionic liquid, the IL@MCM-41 composites exhibit markedly higher mass-transfer efficiency and separation selectivity. This high selectivity arises from the synergistic contributions of strong Ag+–π complexation and the confined mesoporous environment of MCM-41, which together promote preferential C2H4 binding while effectively suppressing C2H6 adsorption. Comprehensive characterizations confirmed that the ordered mesoporous structure of MCM-41 remained intact after IL incorporation, with the ionic liquid uniformly dispersed throughout the pore channels. The composites exhibited thermal stability up to 570 K and showed excellent regenerability, with the 70 wt% IL@MCM-41 retaining nearly all of its initial adsorption capacity and selectivity over ten adsorption–desorption cycles.

Overall, these silver-based IL-modified MCM-41 composites combine high selectivity, high uptake capacity, and strong cycling durability, offering promising potential for low-energy, high-efficiency C2H4/C2H6 separation under mild conditions. These results provide meaningful guidance for the design of next-generation ionic liquid-based adsorbents for olefin/paraffin separations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations13010028/s1, Figure S1: Kinetic model analysis of breakthrough curves using the Clark model; Table S1: Kinetic parameters obtained from Clark model fitting of the breakthrough curves.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D.; methodology, Y.Y. and M.R.; investigation, D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, H.D. and D.L.; supervision, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDA0390503); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22278408); and the Science and Technology Research Project of Advanced Energy Science and Technology Guangdong Laboratory (No. DJL2025A005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Defu Chen was employed by the company Shandong Shuntian Chemical Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, Y.T.; Tsang, Y.F.; Lee, J. Sustainable Ethylene Production: Recovery from Plastic Waste via Thermochemical Processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, B.; Cheng, Y. State-of-the-Art Review of Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Ethane to Ethylene over MoVNbTeOx Catalysts. Catalysts 2023, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Peng, M.; Li, A.; Deng, Y.; Jia, Z.; Huang, F.; Ling, Y.; Yang, F.; Fu, H.; Xie, J.; et al. Low Temperature Oxidation of Ethane to Oxygenates by Oxygen over Iridium-Cluster Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18921–18925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qi, H.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, X.; Dummer, N.F.; Taylor, S.H.; Ma, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, Q.; Hutchings, G.J.; et al. Dynamic Active Site Evolution in Lanthanum-Based Catalysts Dictates Ethane Chlorination Pathways. Angew. Chem. 2025, 137, e202505846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kwon, Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Park, Y.-I. Tailoring the Stabilization and Pyrolysis Processes of Carbon Molecular Sieve Membrane Derived from Polyacrylonitrile for Ethylene/Ethane Separation. Membranes 2022, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Li, J. Energy Efficient Ethylene Purification in a Commercially Viable Ethane-Selective MOF. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 282, 120126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrieva, E.; Grushevenko, E.; Razlataya, D.; Golubev, G.; Rokhmanka, T.; Anokhina, T.; Bazhenov, S. Alginate Ag for Composite Hollow Fiber Membrane: Formation and Ethylene/Ethane Gas Mixture Separation. Membranes 2022, 12, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungta, M.; Zhang, C.; Koros, W.J.; Xu, L. Membrane-based Ethylene/Ethane Separation: The Upper Bound and Beyond. AIChE J. 2013, 59, 3475–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tang, Y.; He, C.; Shu, Y.; Chen, Q.L.; Zhang, B.J. Internal Coupling Process of Membrane/Distillation Column Hybrid Configuration for Ethylene/Ethane Separation. Chem. Eng. Process. 2022, 177, 108982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedram, S.; Kaghazchi, T.; Ravanchi, M.T. Performance and Energy Consumption of Membrane-Distillation Hybrid Systems for Olefin-Paraffin Separation. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2014, 37, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Shi, R.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, H.; Xi, H.; Xia, Q.; Li, Z. Selective Adsorption of Ethane over Ethylene in PCN-245: Impacts of Interpenetrated Adsorbent. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 8366–8373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yan, J.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z. Highly Efficient Separation of Ethylene/Ethane in Microenvironment-Modulated Microporous Polymers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 287, 120580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.G.; Kemp, K.C.; Hong, S.B. Silver ZK-5 Zeolites for Selective Ethylene/Ethane Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 250, 117146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Lv, D.; Shi, R.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Q.; Li, Z. Highly Adsorptive Separation of Ethane/Ethylene by An Ethane-Selective MOF MIL-142A. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 4063–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, D. Silver-Decorated Hafnium Metal-Organic Framework for Ethylene/Ethane Separation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 4508–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dong, H.; Zeng, S.; Hu, Z.; Hussain, S.; Zhang, X. An Overview of Ammonia Separation by Ionic Liquids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 6908–6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Ji, X. Ionic Liquids/Deep Eutectic Solvents for CO2 Capture: Reviewing and Evaluating. Green Energy Environ. 2021, 6, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; He, B.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, R.; Gan, C.; Ji, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, R. Ionic Liquids: A Pitocin for next-Generation Electronic Information Materials? Ind. Chem. Mater. 2025, 3, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Mahurin, S.M.; Dai, S.; Jiang, D. Ionic Liquids for Carbon Capture. MRS Bull. 2022, 47, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, J.E.; Santiago, R.; Redondo, A.E.; Avila, J.; Lepre, L.F.; Gomes, M.C.; Araújo, J.M.M.; Palomar, J.; Pereiro, A.B. Design of Ionic Liquids for Fluorinated Gas Absorption: COSMO-RS Selection and Solubility Experiments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 5898–5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasem, N.; Al-Marzouqi, M.; Ismail, Z. Gas–Liquid Membrane Contactor for Ethylene/Ethane Separation by Aqueous Silver Nitrate Solution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 127, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Liu, W.; Li, D.; Wang, B.; Dong, H.; Yang, Y.; Pan, C.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, Y. Synergistic Effect of Silver-Based Ionic Liquid for Ethylene/Ethane Separation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 8893–8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, F.; Wu, Q.; Peng, K.; Fan, B.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X. Efficient Ethylene/Ethane Separation by Rare Earth Metal-Containing Ionic Liquids in N,N-Dimethylformamide. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 310, 123094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, R.; Yang, Q.; Su, B.; Bao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ren, Q. Improved Efficiency of Ethylene/Ethane Separation Using a Symmetrical Dual Nitrile-Functionalized Ionic Liquid. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, G.; Cheng, Y.; Fan, B.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S. Efficient Separation of Ethylene/Ethane by Incorporation of Silver Salts into Protic Imidazole Ionic Liquids. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 141942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki, S. Factors Controlling the Diffusion of Ions in Ionic Liquids. ChemPhysChem 2012, 13, 1664–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bao, D.; Huang, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S. Gas–Liquid Mass-transfer Properties in CO2 Absorption System with Ionic Liquids. AIChE J. 2014, 60, 2929–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnev, A.V.; Fu, Y.; Gjuroski, I.; Stricker, F.; Furrer, J.; Kovács, N.; Vesztergom, S.; Broekmann, P. Transport Matters: Boosting CO2 Electroreduction in Mixtures of [BMIm][BF4]/Water by Enhanced Diffusion. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 3153–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, A. Enhanced CO2 Adsorption and Separation in Ionic-Liquid-Impregnated Mesoporous Silica MCM-41: A Molecular Simulation Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 8216–8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zhu, H.; Du, X.; An, X.; Wang, E.; Duan, D.; Shi, L.; Hao, X.; Xiao, B.; Peng, C. Unique Allosteric Effect-Driven Rapid Adsorption of Carbon Dioxide in a Newly Designed Ionogel [P4444][2-Op]@MCM-41 with Excellent Cyclic Stability and Loading-Dependent Capacity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 6504–6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, H.; Song, Z.; Qi, Z. Multi-Criteria Computational Screening of [BMIM][DCA]@MOF Composites for CO2 Capture. Green Chem. Eng. 2025, 6, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibisov, A.N.; Chibisova, M.A. Effect of Ammonia and Methane Adsorption on the Electronic Structure of Undoped and Fe-Doped 2D Silica: A First-Principles Calculation. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 056304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, B.; Yan, D. Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Performance of Well-Ordered Crystalline Heteroatom Mesoporous MCM-41. Crystals 2017, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, R.K.; Wahba, M.A.; Badry, M.D.; Zawrah, M.F.; Heikal, E.A. Highly Ordered Pure and Indium-Incorporated MCM-41 Mesoporous Adsorbents: Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation for Dye Removal. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 4504–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, N.S.; Sawada, J.A.; Rajendran, A. Quantitative Microscale Dynamic Column Breakthrough Apparatus for Measurement of Unary and Binary Adsorption Equilibria on Milligram Quantities of Adsorbents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 7032–7051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakov, A.Y.; Zholobenko, V.L.; Bechara, R.; Durand, D. Impact of Aqueous Impregnation on the Long-Range Ordering and Mesoporous Structure of Cobalt Containing MCM-41 and SBA-15 Materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 79, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickler, G.A.; Jähnert, S.; Funari, S.S.; Findenegg, G.H.; Paris, O. Pore Lattice Deformation in Ordered Mesoporous Silica Studied by in Situ Small-Angle X-Ray Diffraction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40, s522–s526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadav, D.; Pandey, M.; Bhojani, A.K.; Amen, T.W.M.; Tsunoji, N.; Singh, D.K.; Bandyopadhyay, M. Mesoporous Silica Supported Ionic Liquid Materials with High Efficacy for CO2 Adsorption Studies. J. Ion. Liq. 2024, 4, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.D.; Harlick, P.J.E.; Sayari, A. Applications of Pore-Expanded MCM-41 Silica: 4. Synthesis of a Highly Active Base Catalyst. Catal. Commun. 2007, 8, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Xu, Q.; Zeng, S.; Li, G.; Jiang, H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, X. Porous Multi-Site Ionic Liquid Composites for Superior Selective and Reversible Adsorption of Ammonia. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 310, 123161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamedali, M.; Ibrahim, H.; Henni, A. Imidazolium Based Ionic Liquids Confined into Mesoporous Silica MCM-41 and SBA-15 for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 294, 109916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Luo, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, C. A Novel Gemini Sulfonic Ionic Liquid Immobilized MCM-41 as Efficient Catalyst for Doebner-Von Miller Reaction to Quinoline. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 3772–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryczkowski, J.; Goworek, J.; Gac, W.; Pasieczna, S.; Borowiecki, T. Temperature Removal of Templating Agent from MCM-41 Silica Materials. Thermochim. Acta 2005, 434, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahk, J.M.; Lischner, J. Core Electron Binding Energies of Adsorbates on Cu(111) from First-Principles Calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 30403–30411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szytuła, A.; Fus, D.; Penc, B.; Jezierski, A. Electronic Structure of RTX (R = Pr, Nd; T = Cu, Ag, Au; X = Ge, Sn) Compounds. J. Alloys Compd. 2001, 317–318, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujie, K.; Yamada, T.; Ikeda, R.; Kitagawa, H. Introduction of an Ionic Liquid into the Micropores of a Metal–Organic Framework and Its Anomalous Phase Behavior. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11302–11305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinik, F.P.; Altintas, C.; Balci, V.; Koyuturk, B.; Uzun, A.; Keskin, S. [BMIM][PF6] Incorporation Doubles CO2 Selectivity of ZIF-8: Elucidation of Interactions and Their Consequences on Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 30992–31005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Feng, M.; Niu, H.; Song, Y.; Li, C.; Zhong, D. Adsorptive Recovery of Ethylene by CuCl2 Loaded Activated Carbon via π-Complexation. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2016, 34, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Varghese, A.M.; Kuppireddy, S.; Gotzias, A.; Khaleel, M.; Wang, K.; Karanikolos, G.N. High-Purity Ethylene Production from Ethane/Ethylene Mixtures at Ambient Conditions by Ethane-Selective Fluorine-Doped Activated Carbon Adsorbents. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 8619–8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.