Abstract

Chicken egg is included among the main components of the human diet as an important source of nutrients, such as proteins, lipids, vitamins, minerals and carotenoids. The latter are terpenoid pigments present in egg yolks, providing their color and playing a vital role because of their significant bioactivities. The carotenoid content of egg yolk varies considerably since it is strongly influenced by the respective laying hens’ farming and feeding procedures, and there is therefore a need to establish an efficient method for their assessment. The absence of such a method prompted us to develop a novel procedure consisting of the extraction, saponification and quantitative assessment of contained carotenoids. For this purpose, the optimal conditions for the extraction of carotenoids from egg yolks were defined, along with the optimal saponification conditions of carotenoids, with respect to reaction duration and pH influence on the extract’s contents of lutein and zeaxanthin. The carotenoid content of extracts was determined using a novel, developed herein LC-MS/MS method that allows the accurate, fast and simultaneous quantitation of the 11 most abundant carotenoids in egg yolks. The method accuracy and reliability were validated for six different parameters determined for each analyte. The novel procedure was applied for the assessment of the carotenoid content of ten egg yolks of diverse origin, indicating the bioactive carotenoids lutein and retinol as the most abundant, while lesser amounts of the remaining natural and synthetic carotenoids were found and there was no trace of fucoxanthin or astaxanthin molecules. The results herein revealed a variation in the carotenoid content of chicken eggs that depended on the diet and farming method of egg-laying hens.

1. Introduction

Carotenoids comprise a group of naturally occurring lipid pigments involved in various biological functions, exhibiting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and immunomodulator effects on human health [1,2,3]. Although most carotenoids are readily available in a broad variety of foods, two naturally occurring xanthophyll carotenoids, namely lutein and zeaxanthin, must be ingested in significant quantities because of their crucial role in maintaining eye health for the protection of retina from damages caused by blue light and oxidative stress [4]. These compounds are present in vegetables (e.g., maize, papaya, etc.), leafy greens (kale, spinach, etc.) and fruits [5,6] or in animal origin foods such as marine-sourced foods (salmon, trout, sardines, etc.) and chicken eggs [5]. The latter in particular constitute a well-established source of highly bioavailable lutein and zeaxanthin [4,7], in concentrations comparable to those of leafy greens [5,8]. Their bioavailability is linked with the simultaneous presence of large amounts of lipids and phospholipids in egg yolks [7], which contribute towards the enhancement of carotenoids’ intestinal micellization, facilitating their efficient absorption [7,9]. Consequently, chicken eggs comprise a widely available, popular food inherently included in human diets as a nutritious component, serving as source of both macronutrients (proteins, fats, carbohydrates) and micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, dietary cholesterol and carotenoid pigments) that support muscle growth, brain health and overall well-being of mankind.

Chicken eggs consist of two parts: the white albumen and the egg yolk. The latter is the yellow or orange spherical part of the egg, composed of lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals and serves as the nourishing center for the developing embryo. Additionally, egg yolks are rich in carotenoid pigments which define their color, the main parameter of yolk quality that ranks third among egg quality parameters, after freshness and eggshell quality [10].

Since the presence of carotenoids in egg yolks is crucial for the definition of their color and quality, their incorporation in egg-laying hens’ rations has become the subject of numerous research endeavors concerning the exploitation of numerous red, orange and yellow pigments for the achievement of a brighter orange egg yolk color [11]. Additionally, the incorporation of various carotenoids into chickens’ diets has also been studied extensively, aiming to boost the quality of their eggs through the improvement of their yolk color and upscaling their health beneficial effects. It must be noted, however, that the pigmenting efficiency of carotenoids depends on several factors such as digestibility, metabolism, transfer, color hue and deposition ability of carotenoids in the target tissues [10]. On the other hand, the presence of highly bioavailable carotenoids in yolk highlights eggs as a valuable source of bioactive pigments, classifying them among the basic human nutrients [12]. This concept has already been applied to produce eggs enriched via feeding with nutrients such as vitamin E, omega-3 fatty acids, selenium and bioactive carotenoids [13]. Finally, egg yolk is considered to be a rich source of provitamin A, the precursor of retinol that plays a vital role in eye function, immunity, brain function, tissue repair and protein digestion [14].

Currently, the following eight carotenoids have already been approved by the European Union (EU) as poultry feed additives: capsanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin and canthaxanthin (consisting of 40 carbons); citranaxanthin (with 33 carbons); and β-apo-8-carotenal and β-apo-8-carotenoic acid ethyl ester (containing 30 carbons). These compounds are of natural origin, except the ethyl ester of β-apo-8′-carotenoic acid and canthaxanthin, widely known by the commercial names Carophyll Yellow and Carophyll Red, which are of synthetic origin [10]. The utilization of synthetic carotenoids is regulated by EU legislation that limits their presence to 80 mg/kg of feed, except for canthaxanthin, which is limited to 8 mg/kg of feed [11].

It must be noted, however, that the increasing demand of consumers for a reduction in the amounts of synthetic carotenoids incorporated into poultry feeding has initiated a campaign for their replacement with various carotenoids of natural origin, such as lutein obtained from either alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and corn (Zea mays) or extracts of marigold (Tagetes erecta) and red pepper (Capsicum annuum) [10]. In this respect, several analytical procedures have been developed to date to assess the dietary carotenoids content in egg yolks or the verification of the applied farming method (e.g., organic, free-range, etc.) [12,13,14]. These methods are combined with various extraction methods, employing a broad range of solvent polarities and alkaline conditions for the ester bond cleavage of carotenoids (saponification) [15,16,17,18,19]. The assessment of carotenoids content is implemented using the Liquid Chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) technique [16,20,21]. A common limitation of these methods is related to the chemical instability of carotenoids under the alkaline conditions used for the saponification of carotenoids that hinders the precise determination of the carotenoids profile. Thus, the driving force for this study was the necessity to overcome this obstacle to achieve a more precise characterization of the contained carotenoids. Consequently, the main objective of the present endeavor is the development of an efficient workflow for the accurate quantification of the most abundant carotenoids in egg yolks. For this purpose, a novel analytical procedure was developed, and its efficacy was tested for the assessment of carotenoid content in ten different egg yolks, produced by different methods of farming egg-laying hens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals, Solvents, and Standards

Lutein (≥95%), zeaxanthin (≥98%) β-carotene (≥98%) and β-cryptoxanthin (≥97%) standards were purchased from ExtraSynthese (Genay, France), canthaxanthin (≥93%) from Honeywell (Charlotte, NC, USA), astaxanthin (≥95%), retinol (≥95%), all-trans-lycopene (≥98%), trans-β-apo-8′-carotenal (≥96%) and fucoxanthin (≥95%) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, MA, USA) and α-carotene (≥95%) was obtained from CaroteNature (Münsingen, Switzerland). LC-MS-grade methanol was obtained from JT Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA) and ethanol from Fisher Chemicals (Hampton, NH, USA). Analytical grade methanol, dichloromethane and diethyl ether solvents were purchased from Fisher Chemical and petroleum ether (40–60 °C), chloroform and dimethyl sulfoxide from Carlo Erba (Val-de-Reuil, France), Fisher Chemicals and Sigma-Aldrich, respectively. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) was purchased from Honeywell and sodium chloride (NaCl) were purchased from Chem-Lab (Zedelgem, Belgium).

2.2. Samples Preparation

A total of 60 chicken eggs was investigated herein, consisting of 12 organic, 18 barn and 30 free-range egg samples all obtained from commercial sources and producers in Greece. Those labeled with SN 3, 4 and 7 to 10 were purchased from the local market, SN 5 and 6 were provided by the egg-laying unit of the Agricultural University of Athens (AUA) and two egg samples (SN 1,2) were obtained from small, private producers. The farming and feeding procedures of the commercially available eggs were obtained from their packaging labels, while the respective information for the remaining eggs were provided by the producers. Each analyzed sample consisted of six eggs from the same producer. Their detailed sampling data are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sampling details of chicken eggs.

Each sample, consisting of six eggs, was prepared as follows: after cracking the shell of each egg, its yolk was manually separated and the content was obtained by rupturing the membrane. The egg yolks were pooled together, homogenized with the aid of a spatula and freeze-dried to afford the respective egg yolk sample as a solid, which was stored at −20 °C until analysis.

2.3. Egg Yolk Extraction Procedure

An amount of 1.5 g from each dried egg yolk (DEY) was poured into a solution consisting of 15 mL of petroleum ether/methanol/ethyl acetate (1:1:1) and stirred for 15 min. The resulting mixture was centrifugated (centrifuge 5430, Eppendorf SE, Hamburg, Germany) at 7800 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was separated by decantation and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure, keeping temperature below 25 °C [Rotavapor R-210 apparatus, equipped with vacuum pump V-700, Vacuum controller V-850 (all from Büchi, Flawil, St Gallen, Switzerland) and a Julabo F12 (Seelbach, Germany) cooling unit]. The resulting solid residue was divided into three parts, which were processed as follows: the first was used for the direct determination of the contained carotenoids, applying the developed herein analytical method and utilizing the LC-MS/MS technique, the second was saponified before analysis and the third was used for the determination of the total carotenoid content (TCC).

All LC-MS/MS determinations of the presence of carotenoids in egg yolks were performed by dissolving the respective amount of dried yolk extract in 1 mL of a chloroform/methanol/hexane (10:10:1) mixture, membrane-filtration (0.45 µm, PTFE) and immediate introduction of the resulting mixture into the analytical instrument.

2.4. Saponification Procedure

The dried egg yolk extract was poured in 2 mL of a petroleum ether/diethyl ether (7:3) mixture and an equal volume of 10% (w/v) KOH solution in methanol was added. After stirring for 2 h at room temperature, the mixture was transferred into a centrifuge tube containing 6 mL of 5% (w/v) NH4Cl solution and centrifuged for 10 min. The aqueous-alcoholic phase was separated by decantation and backwashed twice with 2 × 2 mL of a petroleum ether/diethyl ether (7:3) mixture. The combined organic layers were washed with a saturated brine solution (3 × 10 mL) and centrifuged. The supernatant was transferred to another centrifugation tube and 1 mL of ethanol was added to yield a white solid precipitate. The mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant was separated and evaporated to dryness under vacuum, keeping the temperature below 25 °C. The residue was redissolved in 1 mL mixture of chloroform/methanol/hexane (10:10:1), filtered (0.45 µm, PTFE) and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis.

To avoid the degradation of carotenoids, all steps were carried out under the absence of sunlight and direct light sources. All carotenoids’ samples were maintained at −20 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere.

2.5. Determination of Total Carotenoid Content (TCC)

A third of the dried egg yolk extract, originating from 0.5 g dried egg yolk, was dissolved in 2 mL of dichloromethane and its total carotenoid content was determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm on a Human model X-MA 1000 spectrophotometer (Human Corporation, Seoul, Rep. Korea). The outcome was quantified against a calibration curve (y = 0.2696x + 0.0052, R2 = 0.9999) obtained by measuring the absorbance of β-carotene in dichloromethane for concentrations of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 2.5 and 3.0 μg/mL. The results are expressed as μg of β-carotene equivalents (β-CE) per g DEY. All measurements were performed in triplicate, and the respective results were recorded as the mean ± standard deviation of the three replicates.

2.6. LC-MS/MS Determinations

2.6.1. Preparation of Standard Stock Solutions

Stock solutions were prepared for all analytes in concentrations ranging from 500 to 1200 μg/mL. For this purpose, the appropriate amounts of zeaxanthin, lutein, β-cryptoxanthin, α-carotene and β-carotene standards were dissolved in chloroform, the astaxanthin and canthaxanthin standards were dissolved in dichloromethane and the fucoxanthin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. All stock solutions were maintained in the freezer at −20 °C, were diluted in methanol immediately prior to their use and provided the standard solutions utilized for the construction of the respective calibration curves.

2.6.2. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

The determination of carotenoids was performed using an Accela Ultra High-Performance Liquid Chromatography system, coupled with a TSQ Quantum Access triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The separation of carotenoids was carried out on a C30 column with an internal diameter 3 mm, length 150 mm and particle size 2.7 µm (HALO C30, Advanced Materials Technology, Wilmington, NC, USA). The gradient conditions for mobile phases A (methanol) and B (ethanol) were set as follows: 0.0–20.0 min, from 0% to 40% B; 20.0–22.0 min, 40% B; 22.0–25.0 min from 40% to 60% B; 25.0–26.0 min, 60% B; and 26.1–28.0 min 0% B for re-equilibration of the column. The flow rate during all determinations was set at 0.5 mL/min. The injection volume of each sample was 10 μL, while the tray and column temperatures were, respectively, adjusted to 10 and 12 °C.

For the MS/MS determination, the Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) technique was used in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode.

The molecular ion transition and the collision energies of analytes were determined by direct infusion in full scan at a mass range from 100 to 1400 m/z. The nitrogen gas was generated from a nitrogen generator (Peak Scientific Instruments Ltd., Inchinnan, Scotland, UK) and utilized as sheath and auxiliary gas with initial pressures set at 30 and 5 Arb, respectively. The discharge current was set at 4.0 µA, the capillary and the vaporizer temperature were regulated at 270 °C and 450 °C, respectively, and the collision pressure of Argon gas was adjusted at 0.2 Pa.

The following signals of the selected ion transitions of the deprotonated molecules of m/z were used: Fucoxanthin (658.821 > 598.080 (21 eV)/657.970 (18 eV)) and lutein (568.682 > 535.810 (29 eV)/550.654 (21 eV)). The following signals of the selected ion transitions of the protonated molecules of m/z were used: Astaxanthin (597.199 > 125.263 (31 eV)/153.070 (23 eV)), zeaxanthin (569.219 > 95.568 (33 eV)/123.255 (34 eV)), canthaxanthin (564.547 > 157.233 (25 eV)/174.005 (27 eV)), all-trans-β-cryptoxanthin (553.218 > 95.594 (48 eV)/138.223 (26 eV)), α-carotene (537.265 > 122.898 (30 eV)/413.359 (17 eV)), β-carotene (537.246 > 118.844 (30 eV)/177.270 (19 eV), all-trans-Lycopene (537.213 > 157.113 (26 eV)/282.014 (22 eV)), retinol (286.230 > 160.915 (20 eV)/161.938 (21 eV)) and trans-β-apo-8′-carotenal (417.001 > 104.866 (31 eV)/119.079 (32 eV)). Quantification was performed using resveratrol as the internal standard, monitored at m/z 228.109 > 143.897 (32 eV)/185.924 (21 eV) in negative polarity and RT 2.28 min.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The LCquan 2.7.0.20 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was used for the determination of analytes concentrations. The total carotenoid content and the respective standard deviations were calculated using the statistical functions of Microsoft Office 365. Finally, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test if there were significant differences between the mean values of different samples.

All experiments were performed in triplicate and the respective results have been presented as mean value ± standard deviation. For all calculations the Durbin–Watson statistical tests were performed for the residuals and the respective ANOVA table indicated that the p-value was always less than 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extraction and Saponification Procedures

The appropriate solvent selection comprises a crucial step for the extraction procedure, since the optimal recovery of contained substances depends greatly on the solvent’s properties. An additional limitation for the extraction of carotenoids from egg yolks relates to their high protein and lipid content, parameters affecting the solvent’s efficiency. Thus, an efficient extraction procedure must simultaneously achieve both the recovery of lipid-soluble compounds with a nonpolar solvent and the denaturation of proteins that require the presence of an alcohol. To date, many published methods for the extraction of carotenoids from egg yolks utilize an organic solvent capable of dissolving the contained free carotenoids. In particular, among the diverse methods reported in the literature, the most efficient extraction procedure for the unprocessed egg yolks refers to their dissolution into water and subsequent extraction with a mixture of hexane/isopropanol (3:2) for 15 min [18]. For the dried egg yolks, the best results were obtained using as an extraction solvent either a mixture of methanol/methyl-tert-butyl ether/diethyl ether (1:1:1) or a mixture of petroleum ether/ethyl acetate/methanol (1:1:1) [16]. The latter has proved to be more efficient providing that carotenoid recovery values exceeded 99% [16].

On the other hand, to achieve an accurate and simultaneous quantitation of all carotenoids contained in various samples, it is necessary to include an additional step concerning the performance of the saponification reaction. For this purpose, a solution of potassium hydroxide (KOH) in methanol at concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 10%, is the most commonly used saponifying agent [22] to cleave the ester bonds of conjugated carotenoids or contained triglycerides. Although the inclusion of this step contributes greatly to the accuracy of carotenoid content determination, the strong alkaline environment promotes the isomerization and/or the partial degradation of carotenoids [11,23], since according to literature data, saponification degrades and/or modifies the structure of many plant origin carotenoids [24]. Especially in egg yolks, the application of the saponification reaction is more complicated, since the contained proteins and lipids precipitate in an alkaline environment.

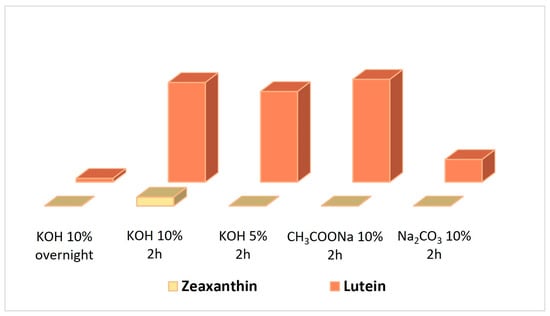

To overcome this problem, we have investigated herein and evaluated a variety of saponification procedures with respect to the reaction duration and alkalinity. For this purpose, the saponification efficacy was evaluated through the determination of obtained lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations, the two most important carotenoids contained in egg yolks. In particular, our study started by applying a procedure previously published by our team [25] utilizing a solution of 10% w/v potassium hydroxide in methanol and stirring overnight at room temperature and in darkness. The observed low concentrations for both lutein and zeaxanthin (Figure 1) prompted us to investigate in detail the reaction parameters, aiming to optimize the saponification outcome. First, we investigated the reaction duration and revealed that 2 h stirring provides the best results, with respect to the concentration of target compounds. Then, considering that a less alkaline environment is also capable of cleaving the ester bond of lutein [22], we prompted to study the gradual decrease of the reaction pH. For this purpose, we either reduced the concentration of potassium hydroxide to 5% w/v or utilized less alkaline environments, such as 10% w/v solutions of sodium acetate or sodium bicarbonate. The respective results are presented in Figure 1, and indicate that although the utilization of sodium acetate provides the best results with respect to the concentration of lutein, the respective amount of zeaxanthin notably decreased. Thus, the best conditions for saponification, in order to provide the highest concentration of both carotenoids, are the utilization of a 10% w/v potassium hydroxide solution in methanol and 2 h stirring.

Figure 1.

The concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin measured after the implementation of the following five saponification procedures: 10% KOH, overnight; 10% KOH, 2 h; 5% KOH, 2 h; 10% CH3COONa, 2 h; 10% Na2CO3, 2 h.

3.2. Total Carotenoid Content (TCC)

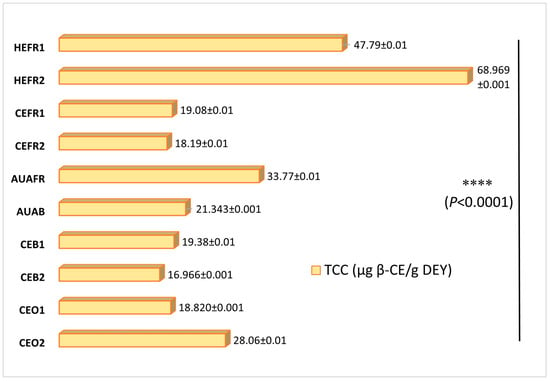

Since the total carotenoid content (TCC) values of egg yolks depend greatly on feed content used for the rearing of the respective egg-laying hens and the applied farming procedure, we have determined herein the fluctuation of their TCC values with respect to these two parameters (Figure 2). Thus, we determined the highest TCC value for egg yolks produced by household farming (47.79 ± 0.01 to 68.97 ± 0.00 μg β-CE/g DEY), a result consistent with a previous report of Bovšková et al., which measured the TCC of household egg yolk as 72.5 μg/g yolk [26]. Free-range farming eggs (AUAFR) from hens reared with rations similar to household hens also exhibited a high TCC value (33.77 ± 0.01 μg β-CE/g DEY). On the contrary, the TCC values determined for yolks obtained from commercial eggs showed a variability, with values ranging from 18.82 ± 0.00 to 28.06 ± 0.01 μg β-CE/g DEY. This variation can be rationalized considering that the respective egg-laying hens have been reared with rations containing diverse plant ingredients. Among the organic samples, the highest TCC value was determined for the CEO2 organic farming eggs, while the corresponding CEO1 eggs from hens reared with herbs with low carotenoid contents (e.g., oregano, lemon balm, savory and thyme) displayed the lowest TCC value. Finally, the remaining samples displayed TCC values ranging from 16.97 ± 0.00 to 19.38 ± 0.01 μg β-CE/g DEY (Figure 2). The observed differences between groups were statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Total carotenoid content (TCC) of the yolk egg samples (mean ± standard deviation) expressed as μg of β-Carotene Equivalents (β-CE)/g dried egg yolk (DEY); **** represents significant differences for different groups (p < 0.0001).

3.3. Quantitation of Individual Carotenoids Presence with LC-MS/MS Analysis

All chromatographic separations were performed using a RP-C30 column. The retention times for all analytes, along with the validation parameters values ensuring the accreditation of the newly developed analytical method, such as linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ) and repeatability, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Validation parameters for each analyte: Retention time (min); Equation; Coefficient of determination (R2); Limit of detection (LOD); Limit of quantification (LOQ); RSD% for intra-day and inter-day.

Determination of Linearity, LOD, LOQ and RSD

For the development of a reliable LC-MS/MS method, a reference solution of 100 μg/mL containing all investigated carotenoids was prepared and diluted at concentrations ranging from 50 to 1500 ng/mL to provide the solutions of analytes used for the construction of calibration curves. The method linearity was tested by injecting the respective solution in triplicate at each concentration level. For each standard, a calibration curve was constructed, and the respective coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated. The data obtained, included in Table 2, indicate the good linearity achieved for all analytes, since all calculated R2 values ranged between 0.9970 and 0.9999. The limits of detection and quantification were determined according to method described by Myrtsi et al. [27]. The respective results verified the good sensitivity of the method, since all LOD values ranged from 33 to 171 ng/mL, while the respective LOQ values ranged from 116 to 519 ng/mL (Table 2). The analytical method repeatability was tested by injecting three replicate samples of 500 ng/mL concentration for each standard during either the same day (intra-day repeatability or run-to-run precision), or over a three-day course (inter-day repeatability or day-to-day precision). The intra- and inter-day repeatability was expressed as the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD), which ranged from 1.3 to 7.8% for run-to-run precision and from 2.9 to 11.4% for day-to-day precision. Day-to-day precision values did not exceed 20%, revealing very good repeatability for almost all cases.

3.4. Quantitation of Carotenoids Presence

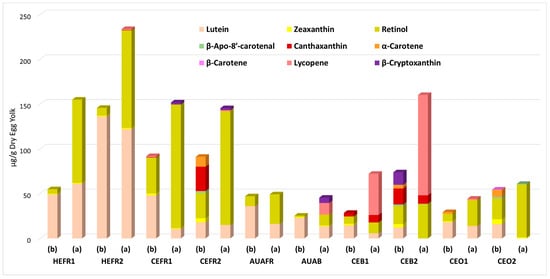

The identification and quantitation of carotenoids contained in the studied egg yolks were performed against the previously used calibration curves of standard compounds using the previously escribed LC-MS/MS analytical procedure. The results are presented in Figure 3, while the precise concentrations (mean ± Standard Deviation) of contained carotenoids, expressed as μg/g DEY and p-values, are provided in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 3.

Quantitation of carotenoid compound contents in the egg yolk samples before (b) and after (a) saponification in μg/g Dry Egg Yolk. p-values are less than 0.05.

The most frequently detected carotenoids in egg yolks are the molecules of lutein and zeaxanthin because of their high content in corn, the most common ingredient of egg-laying hens’ diets. Consequently, the definition of corn hybrid incorporated into hens’ feeding rations constitutes one of the main factors influencing the presence and content of carotenoids in egg yolks [28]. Thus, the literature abounds with reports concerning the comparative profiling of carotenoid content in yolks from eggs originating from different rearing systems. The respective results indicate that the lutein levels are significantly higher compared to those of zeaxanthin, since the lutein presence in yolks of eggs produced by diverse nutrition and farming practices ranges from 7 to 20 μg/g of yolk, while the respective levels of zeaxanthin are considerably lower, ranging between 0.2 and 13 μg/g of yolk [17]. Our measurements were consistent with these findings, since the determined lutein content values in the studied egg samples before saponification ranged from 12.21 ± 0.87 to 136.33 ± 4.13 μg/g of DEY (p < 0.05) and after saponification from 5.82 ± 0.20 to 122.22 ± 9.98 μg/g of DEY (p < 0.05). On the other hand, zeaxanthin was detected only in trace amounts. The observed decrease in lutein concentration after saponification is attributed to the chemical instability and degradation of free lutein under alkaline conditions [29]. It should also be noted that the highest amounts of lutein were found in yolks obtained from household eggs HEFR1 and HEFR2: 49.12 ± 3.21 and 136.33 ± 4.13 μg/g of DEY (p < 0.05) before saponification, and 61.31 ± 7.12 and 122.22 ± 9.98 μg/g of DEY (p < 0.01) after saponification.

With respect to the ability of several carotenoids, such as α-carotene, β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin, to act as precursors of retinol (Vitamin A), the molecule of β-carotene is the most efficient since displays the ability to bio-convert to retinal, which is further reduced to retinol [30]. Thus, these carotenoids are readily converted to retinol within egg-laying hens, thereby increasing the amount of retinol to almost 10 mg of retinol/g of chicken egg yolk [15]. Previous studies have shown that β-carotene is usually detected in egg yolks only in trace amounts, because of its ability to act as a pro-vitamin A molecule that reduces its deposition in yolk [31]. Herein, we have also detected small amounts of β-carotene ranging from 0.12 ± 0.07 to 0.27 ± 0.09 μg/g of DEY (p < 0.05), only in commercial samples of organic and barn farming eggs. Concomitantly, the detected amounts of α-carotene were considerably higher, ranging from 2.1 ± 0.3 to 11 ± 1 μg/g of DEY (p < 0.05), presumably due to the considerably lower ability of α-carotene of bio-conversion to provitamin A [15]. Finally, the molecule of β-cryptoxanthin, another provitamin A-producing compound, was detected only after saponification in free-range farming egg yolks (CEFR1: 2.30 ± 0.19 μg/g DEY, CEFR2: 2.25 ± 0.68 μg/g DEY, p < 0.001). The highest β-cryptoxanthin concentration (13.92 ± 1.12 μg/g DEY, p < 0.0001) was observed in yolks obtained from barn farming eggs. The detection of cryptoxanthin in eggs from the AUAB barn farming reflects the hens’ diet, which includes juicing residues [32]. On the contrary, although previous studies have reported the presence of β-cryptoxanthin in organic farming eggs [12], this was not reveled herein.

Regarding the detected amounts of retinol (Vitamin A), its direct determination in the investigated egg yolks revealed a concentration ranging from 1.51 ± 0.37 to 40.33 ± 2.21 mg of retinol/g of DEY (p < 0.001). These amounts increased considerably with the performance of the saponification step (from 11.73 ± 0.91 to 138 ± 19 g of retinol/g DEY, p < 0.001). This significant increase in retinol content is attributed to the initiated cleavage of retinyl ester bonds, which provided retinol in alkaline environments.

The all trans-lycopene is another natural pigment belonging to the carotenoid family and widely used as colorant of egg yolks. Since lycopene extraction without the preceding saponification step is applicable only for low lipid content samples (<1%), for egg yolks consisting of lipids at approximately 15%, the inclusion of a saponification step is necessary for the removal of the contained lipids and other interfering compounds [33]. Consequently, lycopene was detected only in samples obtained after performing the saponification step, revealing the presence of large amounts of lycopene ranging from 45.93 ± 5.67 to 112.01 ± 1.32 μg /g of DEY (p < 0.01) in yolk samples from barn-raised eggs (CEB1, CEB2). The remaining samples were found to contain only limited amounts of lycopene ranging from 1.11 ± 0.20 to 12.81 ± 4.83 μg /g of DEY (p < 0.01).

Finally, the method developed herein also includes the assessment of several natural carotenoids, such as astaxanthin and fucoxanthin, which were not detected in the investigated egg yolks herein.

With respect to the exploitation of the presence of synthetic carotenoids, their incorporation as supplements in the diets of hens is prohibited according to EU regulation. Consequently, the detection and quantification of synthetic carotenoids, such as canthaxanthin and β-apo-8′-carotenal, in egg yolks may serve as a marker to distinguish between organic and conventional eggs [12]. In this context, the presence of canthaxanthin was revealed only in egg yolks produced by free-range and barn farming systems, while in the respective organic egg samples this molecule was not detected. It must also be noted that since the molecule of canthaxanthin is incorporated in hens’ diets it must be measured without performing the saponification reaction, since this molecule is readily degraded in the alkaline environment of the saponification reaction. On the other hand, the presence of the apocarotenoid compound β-apo-8′-carotenal, used as an additive in poultry feed, was revealed only in commercial egg samples and usually in coexistence with various amounts of canthaxanthin (e.g., CEFR2, CEB2) indicating their probable co-administration in hens’ diets.

4. Conclusions

A novel procedure for the extraction and quantitation of the presence of the 11 most abundant natural and synthetic carotenoids in chicken egg yolks was developed and applied herein. For this purpose, the optimum conditions for the extraction of carotenoids from egg yolks were defined, and subsequently their saponification reaction was exploited with respect to the extract’s contents of lutein and zeaxanthin, the two most abundant carotenoids in eggs. Finally, a novel LC-MS/MS method was developed for the determination of carotenoids content in egg yolks and its accuracy and reliability were validated for six different parameters for each analyte. The procedure developed herein was successfully applied on ten chicken egg samples of diverse origin, revealing the molecules of lutein and retinol to be the most abundant and highlighting the functional role of egg yolk. On the other hand, lesser amounts of the remaining natural and synthetic carotenoids were found, while no traces of fucoxanthin or astaxanthin were detected.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations12110317/s1, Table S1: Carotenoids content in the egg yolk samples before saponification. Results are expressed as μg/g Dry Egg Yolk.; Table S2: Carotenoids content in the egg yolk samples after saponification. Results are expressed as μg/g Dry Egg Yolk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.K.; methodology, S.D.K. and E.D.M.; validation, E.D.M.; formal analysis, E.D.M.; investigation, S.D.K., E.D.M., D.T.P. and V.I.; data curation, E.D.M., D.T.P. and V.I.; writing—original draft preparation, E.D.M. and S.D.K.; writing—review and editing, S.D.K. and S.A.H.; supervision, S.D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate Advanced Materials Technology, Inc. for the donation of the HALO C30 column used for carotenoids determinations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bhatt, T.; Patel, K. Carotenoids: Potent to Prevent Diseases Review. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2020, 10, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.T.; Rahman, M.H.; Shah, M.; Jamiruddin, M.R.; Basak, D.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Bhatia, S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Najda, A.; El-kott, A.F.; et al. Therapeutic Promise of Carotenoids as Antioxidants and Anti-Inflammatory Agents in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.; Basirnejad, M.; Shahbazi, S.; Bolhassani, A. Carotenoids: Biochemistry, Pharmacology and Treatment. Br. J. Pharmac. 2017, 174, 1290–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, K. Hen Egg Carotenoids (Lutein and Zeaxanthin) and Nutritional Impacts on Human Health: A Review. CyTA J. Food 2017, 15, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Meagher, K.A.; Howard, A.N.; Moran, R.; Thurnham, D.I.; Beatty, S. Lutein, Zeaxanthin and Meso-Zeaxanthin Content of Eggs Laid by Hens Supplemented with Free and Esterified Xanthophylls. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiggert, R.M.; Kopec, R.E.; Villalobos-Gutierrez, M.G.; Högel, J.; Quesada, S.; Esquivel, P.; Schwartz, S.J.; Carle, R. Carotenoids Are More Bioavailable from Papaya than from Tomato and Carrot in Humans: A Randomised Cross-over Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Gordon, S.L.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Campbell, W.W. Effects of Egg Consumption on Carotenoid Absorption from Co-Consumed, Raw Vegetables. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, E.-S.; Akhtar, H.; Zaheer, K.; Ali, R. Dietary Sources of Lutein and Zeaxanthin Carotenoids and Their Role in Eye Health. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayana, R.; Raju, M.; Keshava Prakash, M.N.; Baskaran, V. Phospholipid, Oleic Acid Micelles and Dietary Olive Oil Influence the Lutein Absorption and Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in Rats. Lipids 2009, 44, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englmaierová, M.; Bubancová, I.; Skřivan, M. Carotenoids and Egg Quality. Acta Fytotech. Zootech. 2014, 17, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimalaratne, C.; Wu, J.; Schieber, A. Egg Yolk Carotenoids: Composition, Analysis, and Effects of Processing on Their Stability. In ACS Symposium Series; Winterhalter, P., Ebeler, S.E., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 1134, pp. 219–225. ISBN 978-0-8412-2778-1. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ruth, S.; Alewijn, M.; Rogers, K.; Newton-Smith, E.; Tena, N.; Bollen, M.; Koot, A. Authentication of Organic and Conventional Eggs by Carotenoid Profiling. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahachairungrueng, W.; Thompson, A.K.; Terdwongworakul, A.; Teerachaichayut, S. Non-Destructive Classification of Organic and Conventional Hens’ Eggs Using Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging. Foods 2023, 12, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, J.; Molkentin, J.; Döring, M.; Haase, I. Egg Authentication under Seasonal Variation Using Stable Isotope Analysis Combined with Machine Learning Classification. Food Control 2025, 168, 110898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Du, L.; Tang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Li, F.; Yao, X.; Meng, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, J. Development and Application of a SFC–DAD–MS/MS Method to Determine Carotenoids and Vitamin A in Egg Yolks from Laying Hens Supplemented with β-Carotene. Food Chem. 2023, 414, 135376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlatterer, J.; Breithaupt, D.E. Xanthophylls in Commercial Egg Yolks: Quantification and Identification by HPLC and LC-(APCI)MS Using a C30 Phase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2267–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammershøj, M.; Kidmose, U.; Steenfeldt, S. Deposition of Carotenoids in Egg Yolk by Short-Term Supplement of Coloured Carrot (Daucus carota) Varieties as Forage Material for Egg-Laying Hens. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.M.S.; Schweigert, F.J. Comparison of Three Spectrophotometric Methods for Analysis of Egg Yolk Carotenoids. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, A.; Copaciu, F.M.; Paşcalău, S.; Dulf, F.; Rugină, D.; Chira, R.; Pintea, A. Chromatographic Analysis of Lypophilic Compounds in Eggs from Organically Fed Hens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2017, 26, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids: Distribution, Function in Nature, and Analysis Using LC-Photodiode Array Detector (DAD)-MS and MS/MS System. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 12, A0133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M.A.; Aktaş, H.; Pokorski, P.; Pogorzelska-Nowicka, E.; Custodio-Mendoza, J.A. A Comprehensive Review of Analytical Approaches for Carotenoids Assessment in Plant-Based Foods: Advances, Applications, and Future Directions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, E.M.; Webb, M.Z.; Simpson, C.M.; Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Riedl, K.; Moran, N.E.; Clinton, S.K. Assessment of Dietary Carotenoid Intake and Biologic Measurement of Exposure in Humans. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 674, pp. 255–295. ISBN 978-0-323-91351-5. [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Mandić, A.I.; Bantis, F.; Böhm, V.; Borge, G.I.A.; Brnčić, M.; Bysted, A.; Cano, M.P.; Dias, M.G.; Elgersma, A.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on Carotenoids in Foods and Feeds: Status Quo, Applications, Patents, and Research Needs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Dini, S.; Esmaeili, Y.; Roshanak, S.; Redha, A.A.; Wani, S.A. Uses of Carotenoid-Rich Ingredients to Design Functional Foods: A Review. J. Food Bioact. 2023, 21, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrtsi, E.D.; Koulocheri, S.D.; Evergetis, E.; Haroutounian, S.A. Pigments’ Analysis of Citrus Juicing Making By-products by LC-MS/MS and LC-DAD. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovšková, H.; Míková, K.; Panovská, Z. Evaluation of Egg Yolk Colour. Czech J. Food Sci. 2014, 32, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrtsi, E.D.; Koulocheri, S.D.; Iliopoulos, V.; Haroutounian, S.A. High-Throughput Quantification of 32 Bioactive Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds in Grapes, Wines and Vinification Byproducts by LC–MS/MS. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurak, D.; Svečnjak, Z.; Gunjević, V.; Kiš, G.; Janječić, Z.; Pirgozliev, V.; Grbeša, D.; Kljak, K. Carotenoid Content and Deposition Efficiency in Yolks of Laying Hens Fed with Dent Corn Hybrids Differing in Grain Hardness and Processing. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, I.; Jose, N.M.; Mamatha, B.S. Oxidative Stability of Lutein on Exposure to Varied Extrinsic Factors. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamantidi, T.; Lafara, M.-P.; Venetikidou, M.; Likartsi, E.; Toganidou, I.; Tsoupras, A. Utilization and Bio-Efficacy of Carotenoids, Vitamin A and Its Vitaminoids in Nutricosmetics, Cosmeceuticals, and Cosmetics’ Applications with Skin-Health Promoting Properties. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljak, K.; Carović-Stanko, K.; Kos, I.; Janječić, Z.; Kiš, G.; Duvnjak, M.; Safner, T.; Bedeković, D. Plant Carotenoids as Pigment Sources in Laying Hen Diets: Effect on Yolk Color, Carotenoid Content, Oxidative Stability and Sensory Properties of Eggs. Foods 2021, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; He, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, S.; He, Z.; Ye, J.; Xu, J. Lycopene Accumulation in Cara Cara Red-Flesh Navel Orange Is Correlated with Weak Abscisic Acid Catabolism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 8236–8246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu, T.; Huvaere, K.; Van Den Bergh, M.-A.; Vinkx, C.; Van Loco, J. A Simple and Fast HPLC Method to Determine Lycopene in Foods. Food Anal. Methods 2012, 5, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).