Abstract

The extraction of high-quality DNA is essential for molecular analyses in grapevine, yet differences among commonly used protocols remain underexplored. This study compared two cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-based methods, with and without polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and three commercial kits (peqGOLD Plant DNA Mini Kit, Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit, and SPINeasy DNA Kit for Plant MP) using grapevine leaves and other tissues and further validated the CTAB protocol across 34 cultivars. DNA yield, purity, and integrity were assessed spectrophotometrically and by electrophoresis, while PCR suitability was confirmed for all methods. CTAB provided the highest yields and purity at low cost, with densitometry showing approximately 70–85% high-molecular-weight DNA (>20 kb). The Qiagen kit yielded reproducible results with moderate integrity (about 40–60% HMW fraction), making it suitable for high-throughput applications. The MP kit produced high concentrations but severe fragmentation (<10% HMW fraction) due to bead-beating, while the VWR kit performed worst in yield and purity. The addition of PVP improved DNA purity in polyphenol-rich tissues but reduced yield. All protocols generated DNA sufficient for PCR amplification. Overall, CTAB was robust and cost-effective across cultivars and tissues, Qiagen offered speed and reproducibility, and MP provided high concentration at the expense of integrity.

1. Introduction

The grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is one of the world’s most important perennial crops, central to viticulture and winemaking and cultivated across diverse environments. Beyond its economic significance, grapevine also serves as a model species for research on perennial crops, breeding, and molecular physiology. Molecular techniques applied to grapevine are used for a wide range of purposes, including breeding studies, marker-assisted selection, gene source determination, origin identification, parent assignment, pedigree analysis, genome mapping, and pest and disease diagnostics [1,2,3]. A critical prerequisite for all these molecular applications is the extraction of genomic DNA with sufficient yield, purity, and integrity. Ideally, a DNA isolation method should consistently produce intact and functional DNA free of inhibitors, ensure high yield, be rapid and reproducible, remain cost-effective, and be adaptable to various tissues and experimental contexts [4,5].

Isolating DNA from grapevine tissues remains challenging due to their biochemical complexity. Grapevine leaves and other organs contain high levels of polysaccharides, polyphenols, and secondary metabolites that interfere with downstream enzymatic reactions. During tissue disruption, cytoplasmic compounds are released and interact with nuclear contents, creating significant obstacles to efficient DNA extraction. Polysaccharides co-precipitate with DNA, producing viscous solutions that inhibit polymerases, ligases, and restriction endonucleases, and complicate DNA quantification [6,7]. Polyphenolic compounds oxidize rapidly and form irreversible complexes with nucleic acids and proteins, leading to DNA degradation or the formation of insoluble high-molecular-weight aggregates unsuitable for molecular analyses [8,9]. Additionally, detergents, proteins, lipids, and salts introduced during extraction can inhibit PCR amplification and sequencing [10]. These biochemical challenges require that protocols be carefully optimized for grapevine to produce DNA of sufficient quality for routine molecular applications.

Over the past decades, CTAB-based methods have been the most widely used for grapevine DNA isolation. The early methods of Dellaporta et al. [1] and Doyle and Doyle [2] established the foundation for plant DNA extraction but required adaptation to address grapevine’s high polysaccharide and polyphenol content. Lodhi et al. [3] introduced one of the most influential grapevine-specific modifications by adding polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to bind polyphenols and β-mercaptoethanol as an antioxidant, improving DNA suitability for PCR and RFLP analyses. Labra et al. [11] refined CTAB methods to enhance reproducibility, while Piccolo et al. [9] introduced buffer modifications that minimized polysaccharide contamination and increased DNA integrity for AFLP and SSR marker applications. Collectively, these CTAB-based protocols remain reliable and cost-effective, especially in breeding and genetic studies requiring large sample throughput. However, they involve multiple precipitation and washing steps, rely on hazardous reagents such as chloroform and β-mercaptoethanol, and often require laborious optimization depending on tissue type, age, and physiological state. In contrast, commercial DNA extraction kits, most often based on silica spin column purification or magnetic bead separation, offer faster and more user-friendly workflows. These kits eliminate the need for organic solvents, reduce technical variation, and provide DNA within an hour, making them attractive for diagnostics and projects requiring rapid turnaround. They are also compatible with automation, facilitating high-throughput genotyping. However, their performance with grapevine tissues is variable. While young, tender leaves often yield satisfactory DNA, mature leaves, stems, and seeds rich in polyphenols and polysaccharides frequently produce DNA of insufficient purity for PCR or sequencing. Kits are also significantly more expensive per sample, which limits their utility in large-scale breeding programs and population genetics studies [10,12].

Comparative studies in other plant systems have repeatedly shown that method selection is crucial for obtaining DNA of sufficient yield and quality. In Eurycoma longifolia, a medicinal plant rich in polyphenols, a modified CTAB protocol outperformed commercial kits by producing amplifiable DNA [13]. In Tamarix species, which contain high levels of tannins and flavonoids, the Nalini et al. method generated superior yields and purity compared with classical CTAB or kit-based approaches [14]. In maize, Abdel-Latif and Osman [15] demonstrated that a modified Mericon protocol delivered higher DNA quality and yield from grains than CTAB or Qiagen kits, highlighting the need for method adaptation in starch-rich tissues. More recently, Liu et al. [16] simplified CTAB extraction in Chimonanthus praecox, reducing processing time and costs while still producing PCR-quality DNA. These examples confirm that no single method is universally applicable and that comparative testing is essential to identify optimal protocols for each species and tissue type.

Within grapevine, several optimization studies illustrate the same principle. Marsal et al. [17] developed a DTAB + CTAB method suitable for leaves, stems, and seeds that avoided RNase treatment, reduced costs, and delivered high-quality DNA suitable for SSR genotyping. In a subsequent study, Marsal et al. [18] compared nine classical protocols, two commercial kits, and a direct-PCR kit across grapevine tissues, demonstrating that only DTAB + CTAB approaches consistently produced amplifiable DNA from both recalcitrant and non-recalcitrant tissues. They also proposed a simplified protocol optimized for young leaves, reducing extraction time to 90 min, lowering costs to approximately €17 per eight samples, and enabling throughput of up to 96 samples per day. These optimization studies highlight that protocol performance is highly tissue-dependent and that balancing DNA quality, processing time, and cost is essential in grapevine molecular research.

Taken together, these findings show that DNA isolation from grapevine is both an art and a science. CTAB-based methods and commercial kits each have strengths and limitations, and even within grapevine tissues, no single protocol is universally optimal. The objective of this study is to directly compare two laboratory CTAB-based protocols with three commercially available spin column-based kits for extracting DNA from young grapevine leaves. DNA yield, purity, and PCR sensitivity were evaluated to identify the most efficient, reliable, and cost-effective method for grapevine molecular applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Fresh young and mature grapevine leaves (blade and steam) and wood were collected from Muscaris grape variety at the Experimental station Jazbina of the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture. For the validation of the robustness and applicability of the method, young leaves from 34 grapevine cultivars, namely Bačka, Cabernet Volos, Johanniter, Panonija, Kozmopolita, Bianca, Merzling, Lisa, Orion, Sirius, Phoenix, Regent, Staufer, Sauvignier gris, Allegro, Accent, Bolero, Cabernet Cortis, Floreal, Fleurtai, Voltis, Vidoc, Sauvignon Kretos, Cabernet Cantor, Merlot Kanthus, Caladris blanc, Sauvignon Rytos, Merlot Khorus, Hibernal, Soreli, Solaris, Artaban, Graševina, Diseca Ranina were employed. The isolations were performed immediately upon collecting the fresh leaves.

2.2. DNA Extraction

DNA extraction was performed using five different approaches: two CTAB-based methods and three commercial kits. Each method was replicated three times. The tested methods were as follows: (1) the CTAB-based method, (2) the CTAB-based method supplemented with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in the lysis buffer (CTAB + PVP method), (3) peqGOLD Plant DNA Mini Kit, VWR kit (VWR International, Darmstadt, Germany; Cat. No. 13-3486-02), (4) DNeasy Plant Mini Kit, Qiagen kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany; Cat. No. 69104), and (5) SPINeasy DNA Kit for Plant, MP kit (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA; Cat. No. 117022150). Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of all tested methods.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of tested methods.

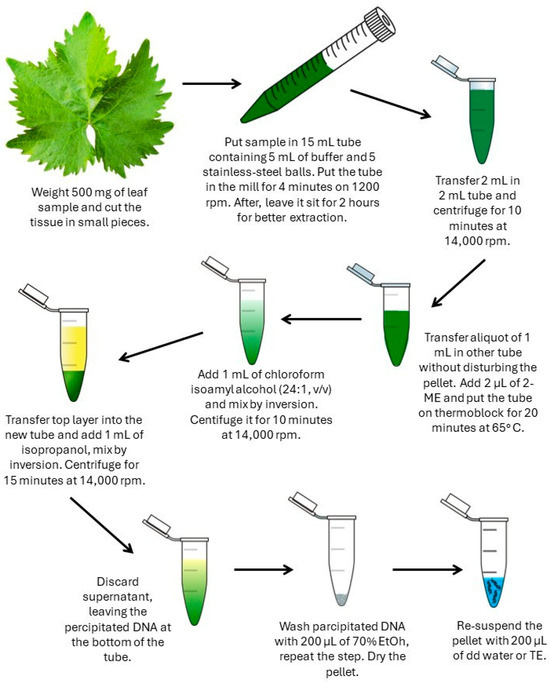

The CTAB-based methods were adapted from the protocol described by Lodhi et al. [3] with several modifications. The reagents used included a lysis buffer containing 3% CTAB, 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1.4 M NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA; 2-mercaptoethanol; chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1, vol/vol); and isopropanol. The CTAB + PVP method differed only by the addition of 3% PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone) to the lysis buffer. All reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Figure 1 details the steps involved in the DNA isolation procedure. The DNA isolation methods for the three commercial kits were conducted according to each manufacturer’s protocol. The full protocols can be accessed through the provided links: for the VWR kit: https://uk.vwr.com/assetsvc/asset/en_GB/id/27794326/contents/quick-guide-dna-isolation-plant-dna-mini-kit-peqgold.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025); for the Qiagen kit: https://www.qiagen.com/cn/resources/download.aspx?id=6b9bcd96-d7d4-48a1-9838-58dbfb0e57d0&lang=en (accessed on 4 February 2025); and for the MP kit: https://www.mpbio.com/media/document/file/manual/dest/s/p/i/n/e/SPINeasy_DNA_kit_for_Plant.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOopAMhEWssM74o2CNVAz0KIZ05ZtmBzZA-yKmOrufZtZUVnN-6wG (accessed on 4 February 2025). The tissue disruption step for the Qiagen and VWR kits was tested by grinding fresh leaf tissue in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle and by grinding both fresh and lyophilized tissue in a mill with stainless steel beads. Initial weights for fresh tissue were 100 mg for the Qiagen kit and 50 mg for the VWR kit, while 20 mg of lyophilized tissue was used for both kits. For grinding tissue in a mill, five sterile stainless steel balls (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ, USA) were placed in 2 mL tubes containing cut grapevine tissue or lyophilized tissue. These were processed in a 1600 MiniG homogenizer (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ, USA) at 4000 rpm for 4 min. The bead grinding method with fresh tissue yielded the highest results for both DNA extraction methods, and thus those data were considered in this paper. For the MP kit, 100 mg of fresh tissue was homogenized in the FastPrep-24™ 5G (MP Biomedical, Santa Ana, CA, USA) according to the provided protocol for tomato leaves (speed 6 m/s, time 30 s, number of cycles 4, rest time 300 s). All extractions were performed by the same trained researcher using identical procedures to ensure reproducibility and eliminate operator-related variability.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the CTAB-based DNA isolation method. The schematic illustrates the main steps of the protocol, including tissue homogenization, cell lysis, phase separation, DNA precipitation, washing, and resuspension.

2.3. Spectrophotometric Analyses of DNA

The quantity and purity of DNA extracted using the various methods described were assessed with a Lambda XLS+ UV/VIS spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a microcell cuvette TrayCell 2.0 (Hellma Analytics, Müllheim, Germany). DNA concentration in each sample was quantified by measuring absorbance at 260 nm, and the absorbance ratios A260/A230 and A260/A280 were used to check for contamination. DNA was considered sufficiently pure when the A260/A280 ratio was between 1.8 and 2.0, indicating minimal protein contamination, and the A260/A230 ratio exceeded 2.0, reflecting low levels of polysaccharides or phenolic compounds.

2.4. PCR Amplification

To evaluate the sensitivity of DNA extracted using various techniques, PCR was performed on a ProFlex PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) with the Type-it Microsatellite PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The 25 µL reaction mixture contained 12.5 µL Master Mix, 2.5 µL Q-Solution, 4.5 µL RNase-Free Water, 2.5 µL primer, and 3 µL DNA sample. The SSR primer Indel-27 was used for this purpose (Table S1). The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 57 °C for 1 min and 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; followed by a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min.

2.5. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

DNA integrity was assessed using gel electrophoresis. DNA samples were separated on a 0.5% agarose gel (Cleaver Scientific Ltd., Rugby, UK), and PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel, both in 1X TBE buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For staining, 8 μL of each sample was mixed with 2 μL of CSL-RUNSAFE fluorescent reagent (Cleaver Scientific Ltd., Rugby, UK) and electrophoresed at a constant voltage for 60 min. Bands were visualized under UV light.

2.6. Capillary Electrophoresis

The PCR products, after amplification, were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis on the Qsep 100 BIO-Fragment Analyzer equipped with the S1 High Resolution Cartridge (BiOptic Inc., New Taipei City, Taiwan). This CE system uses highly sensitive LED-induced fluorescence. The DNA alignment markers (20 bp and 1000 bp) and the DNA size marker (20–1000 bp) were obtained from BiOptic. The run parameters were a sample injection at 4 kV for 10 s and separation at 6 kV for 300 s. Q-Analyzer software (BiOptic Inc.) was used to visualize the sample peaks.

2.7. Validation of DNA Quality Using Additional Genetic Markers

To further assess the quality and suitability of DNA extracted using the CTAB method, amplification was performed with three additional grapevine genetic markers (Table S1): Indel-20 (associated with the Ren3/Ren9 loci), GF-09-44, and GF-09-57 (both linked to the Rpv10 locus). Each PCR reaction was conducted individually using the Type-it Microsatellite PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) under the same cycling conditions described in Section 2.4, with primer-specific annealing temperatures optimized according to published protocols. The resulting PCR products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis as described in Section 2.6, using the same Qsep100 BIO-Fragment Analyzer (BiOptic Inc., New Taipei City, Taiwan). Fragment analysis and size determination were performed using Q-Analyzer software (BiOptic Inc.), confirming the specificity and integrity of all amplified products.

3. Results and Discussion

In recent decades, the use of new techniques in plant molecular biology has advanced significantly. Isolating high-quality DNA is essential for certain analyses, and to obtain accurate results, the DNA must be free from contaminants commonly found in plant cells. Many authors have described DNA isolation, each offering different methods to address challenges encountered during plant DNA extraction, particularly those posed by polyphenolic compounds, polysaccharides, and RNA [19]. For this reason, this research evaluated five DNA isolation techniques: the CTAB method, the CTAB + PVP method, the VWR kit, the Qiagen kit, and the MP kit.

The first step in all DNA isolation methods is disrupting the cell walls to release cellular components [20,21]. This can be done by grinding tissue in dry ice or liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle, or by using a mill with steel or glass rods or beads. In addition to physical methods, chemical disruption is also used, such as applying hydrolyzing enzymes like cellulases, pectinases, or cell wall macerases to dissolve the cell wall [14].

Grinding fresh leaf tissue in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle was compared to grinding both fresh and lyophilized tissue in a mill with stainless steel beads. DNA extracted from lyophilized tissue had concentrations of 33.91 ± 1.88 ng/µL with the Qiagen kit and 18.67 ± 2.13 ng/µL with the VWR kit, while DNA extracted from fresh tissue ground in liquid nitrogen yielded 8.75 ± 1.3 ng/µL with the Qiagen kit and 2.75 ± 1.39 ng/µL with the VWR kit. The bead grinding method with fresh tissue produced the highest yields for each DNA extraction method tested, and these results were prioritized for analysis. The yields are not directly comparable because lyophilization requires an additional step, which was avoided by using fresh tissue. The MP kit differed by providing a vial containing Lysing Matrix A and beads for tissue disruption.

3.1. Yield and Purity of DNA

To compare the performance of different extraction methods, DNA concentration, yield, and purity were evaluated in young leaves, mature leaves, stems, and wood tissues. The quantity and quality of DNA isolated from various grapevine tissues were assessed using spectrophotometry and electrophoresis. DNA concentration was measured by absorbance at 260 nm, while a 260/280 ratio of approximately 1.8 indicated high-purity DNA, free from contaminants such as proteins, RNA, or phenolic compounds. A260/230 ratios were also used as indicators of contamination with polysaccharides or polyphenols. Results for DNA concentration, yield, and purity are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

DNA concentration, yield, and purity (A260/280 and A260/230 ratios) obtained from different grapevine tissues (young leaves, mature leaves, wood, and stem) using five extraction methods (CTAB, CTAB + PVP, VWR kit, Qiagen kit, and MP kit).

All tested protocols enabled successful DNA extraction from young leaves, mature leaves, wood, and stem, but the quantity and quality varied considerably depending on both the method and tissue type. In young leaves, DNA concentration ranged from 59.92 ng/µL (VWR kit) to 250.83 ng/µL (MP kit). When recalculated as yield per mg of tissue, the CTAB method provided the highest DNA yield (479 ng/mg), followed by Qiagen (350 ng/mg), while the VWR kit produced the lowest yield (179.75 ng/mg). Purity values were generally acceptable, with ratios close to 1.8, although the VWR kit again showed the lowest A260/280 ratio (1.67), indicating protein contamination.

In mature leaves, overall yields were lower than in young leaves, likely due to higher levels of polyphenols and polysaccharides. The CTAB method was the most effective (309.75 ng/mg), while CTAB + PVP improved the A260/230 ratio (2.09), indicating reduced contamination but with lower yield (163.03 ng/mg). The MP and Qiagen kits produced intermediate results, and the VWR kit again yielded the lowest concentration and purity.

For woody tissue, DNA yields were significantly reduced across all methods, reflecting the structural complexity and inhibitory compound content of this tissue. The CTAB method produced the highest yield (116.42 ng/mg), while the VWR kit produced the lowest (38.16 ng/mg). Despite the reduced yields, A260/280 and A260/230 ratios remained within acceptable ranges, indicating that the isolated DNA, though limited in quantity, was still of sufficient quality for PCR.

In the stem, CTAB produced the highest yield (172.15 ng/mg), while the MP kit provided the highest DNA concentration (89.08 ng/µL). The Qiagen and CTAB + PVP methods generated moderate concentrations and yields, whereas the VWR kit consistently ranked lowest.

The addition of PVP to the CTAB protocol improved A260/230 ratios in mature leaves and woody tissues, consistent with its role in binding polyphenolics. However, in young leaves with lower polyphenol content, PVP supplementation did not significantly improve DNA purity, confirming earlier reports that its benefits are tissue dependent.

These results clearly demonstrate that tissue type strongly influences DNA extraction efficiency and quality. Young leaves yielded the highest amounts of DNA, reflecting their lower polyphenol and polysaccharide content, while mature leaves and woody tissues posed greater challenges due to the accumulation of inhibitory compounds. In these tissues, modifications such as the inclusion of PVP improved DNA purity, though often at the cost of yield [22]. Stems showed intermediate results, indicating that tissue lignification and secondary metabolite content affect extraction outcomes. Collectively, these findings highlight the necessity of tailoring extraction protocols to tissue type, particularly when working with mature or lignified plant material, to ensure sufficient DNA quality and quantity for downstream applications.

CTAB-based DNA extraction protocols are widely used for plant material because they effectively remove polysaccharides and polyphenols that interfere with downstream molecular analyses. The classical methods of Doyle and Doyle [2] and Lodhi et al. [3] form the basis of most subsequent modifications and are particularly effective for woody species such as grapevine. However, these approaches often require multiple chloroform extractions, RNase treatment, and extended incubations, which increase handling time and procedural variability. Later adaptations, such as those by Labra et al. [11] and Piccolo et al. [9], incorporated PVP or higher concentrations of β-mercaptoethanol to reduce phenolic oxidation, improving purity but also increasing the cost and complexity of the extraction. The CTAB method used in this study was adapted from Lodhi et al. [3] and optimized for grapevine tissues. The protocol uses a 3% CTAB buffer (pH 8) with high salt concentration, mechanical homogenization, and a two-step lysis procedure: a 2 h incubation of the ground tissue in extraction buffer followed by reduction with 2-mercaptoethanol at 65 °C for 20 min. A single chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extraction efficiently removes proteins and polysaccharides, and the DNA is precipitated with isopropanol and washed with 70% ethanol. This workflow eliminates the need for RNase or PVP, simplifying the protocol while maintaining DNA integrity. Compared with previously published CTAB modifications, the present approach yielded DNA with A260/230 ratios around 2.0, A260/280 ratios between 1.8 and 1.9, and low relative standard deviations for both concentration and purity (Table 2), demonstrating high reproducibility and efficiency. This method therefore combines the chemical robustness of classical CTAB extraction with procedural simplicity, providing a reliable, low-cost option for routine isolation of high-quality DNA from grapevine leaves.

These results provided a quantitative basis for assessing extraction efficiency and formed the foundation for subsequent analyses of DNA integrity and PCR suitability.

3.2. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

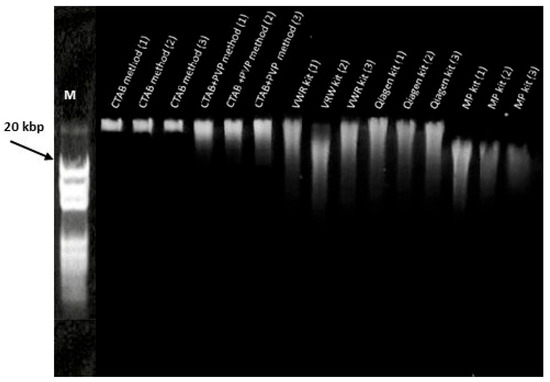

Beyond yield and purity, DNA integrity is a critical factor in the success of downstream molecular applications. Therefore, the extracted DNA samples were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis to assess fragmentation and overall quality. Genomic DNA integrity was evaluated using 0.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1× TBE buffer at 4 V/cm for 60 min, with 200 ng of DNA loaded per lane. High-molecular-weight (HMW) genomic DNA was defined as a compact band retained near the well (>~50 kb) with minimal trailing, while fragmentation was indicated by a continuous smear extending into lower-molecular-weight regions (~0.5–20 kb). The gels shown are representative of three independent extractions.

Figure 2 shows the electrophoretic patterns of DNA samples extracted using different isolation methods, highlighting distinct levels of fragmentation associated with the homogenization system used. The CTAB-based methods exhibited a predominant HMW band retained at the well with only faint smearing, indicating minimal shearing and strong integrity suitable for downstream applications. The addition of PVP slightly improved purity without affecting integrity. The Qiagen kit showed a clear HMW band with a moderate smear in the 10–30 kb range, reflecting mild shearing during column-based processing. The VWR kit produced a weaker HMW component and a broad smear spanning 2–20 kb, suggesting greater fragmentation and possible contaminants. The MP kit yielded the most diffuse smear, concentrated in the 0.5–10 kb range with little HMW DNA retained near the well, indicating pronounced fragmentation.

Figure 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis (0.5%) of genomic DNA extracted from grapevine leaves using CTAB, CTAB + PVP, VWR kit, Qiagen kit, and MP kit. Lane M represents the molecular weight marker (20 kbp ladder). Original unprocessed gel image is provided as Supplementary Figure S1.

These patterns correspond to the homogenization methods. The FastPrep-24™ 5G system used in the MP kit applies bead beating at 6 m/s in repeated cycles, causing high-energy impacts that effectively lyse cells but also induce substantial DNA shearing. In contrast, the 1600 MiniG homogenizer (used with CTAB and Qiagen protocols), operating at 4000 rpm with reciprocal horizontal motion, generates less mechanical stress, preserving DNA integrity while still ensuring effective lysis. These findings are consistent with previous reports that bead beating increases DNA fragmentation compared to liquid nitrogen grinding in CTAB workflows [1], and that CTAB-based extractions are effective in preserving high-molecular-weight DNA required for long-read sequencing [23,24,25].

Densitometry was performed on gel images using CLIQS (TotalLab Ltd., Gosforth. UK). Lane profiles were analyzed, and the area under the curve was divided into high-molecular-weight DNA (>~20 kb, signal retained near the well) and lower-molecular-weight fragments (<~20 kb). After background correction, the HMW fraction accounted for approximately 70–85% of the signal in CTAB lanes, 40–60% in Qiagen, 15–25% in VWR, and less than 10% in MP.

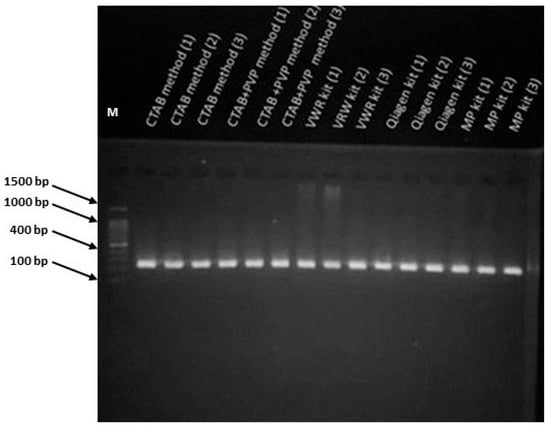

PCR analysis was performed on DNA from all samples to assess the amplification capability of the extracted genomic DNA and to detect any potential inhibitors that could interfere with the reactions. Additionally, the analysis aimed to determine the most suitable method for applying Marker Assisted Selection (MAS). For this purpose, a specific primer, Indel-27, was used as a marker for the Ren9 locus conferring resistance to Powdery Mildew. The resistance locus Ren9 has already been confirmed in the Muscaris variety [26,27]. PCR suitability was confirmed by successful amplification of the target fragment, with the presence of a single amplicon of the expected size and the absence of nonspecific products on the gel regarded as the criterion for success.

Overall, the results show that while all methods produced DNA suitable for PCR amplification (Figure 3), only CTAB and, to a lesser extent, Qiagen consistently yielded high-molecular-weight DNA of sufficient quality for long-read sequencing or other applications requiring intact fragments. In contrast, the VWR and especially MP kits resulted in greater DNA fragmentation, highlighting the trade-off between homogenization efficiency and preservation of genomic integrity.

Figure 3.

PCR amplification of the SSR marker Indel-27 (Ren9 locus) from DNA isolated with the five tested methods. Lane M indicates the molecular weight marker (1500–100 bp ladder). Original unprocessed gel image is available as Supplementary Figure S2.

Figure 3 shows the 2% agarose gel electrophoresis results of PCR products obtained with the primer Indel-27. Each sample showed positive amplification and strong band intensities, confirming that the DNA quality from all extraction protocols was adequate for PCR amplification. Additionally, low levels of impurities in some samples did not hinder polymerase activity.

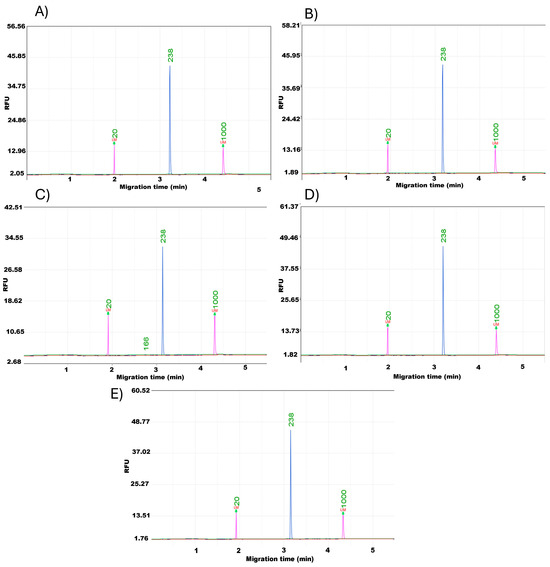

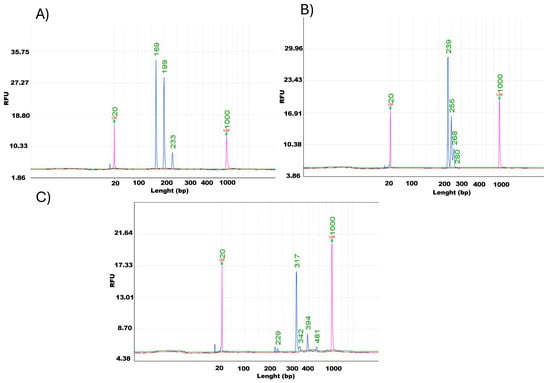

3.3. Capillary Electrophoresis

To confirm the functional quality of the extracted DNA, PCR amplification was performed using the SSR marker Indel-27. This step validated whether DNA from each extraction method could serve as a reliable template for downstream analyses. To determine the optimal DNA isolation method for Marker Assisted Selection (MAS) in grapevines, PCR products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis for precise separation and comparison. The results showed uniform band patterns for all samples, regardless of the DNA extraction method used (Figure 4). This uniformity indicates that each method successfully produced DNA suitable for amplification and detection, suggesting that any of the tested DNA isolation methods can be effectively used for MAS applications.

Figure 4.

Capillary electrophoresis of PCR products generated with primer Indel-27 using DNA isolated by five methods: (A) CTAB, (B) CTAB + PVP, (C) VWR kit, (D) Qiagen kit, and (E) MP kit.

To further assess the suitability of DNA extracted using the CTAB method for PCR-based analyses, three additional grapevine genetic markers were tested individually: Indel-20 (associated with the Ren3/Ren9 loci), GF-09-44, and GF-09-57 (both linked to the Rpv10 locus). Each marker was successfully amplified in single PCR reactions, and the resulting products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis. Clear and specific peaks corresponding to the expected allele sizes were observed for all markers, with no signs of non-specific amplification or DNA degradation. These results confirm that DNA obtained with the CTAB extraction method has high integrity and is suitable for reliable amplification of diverse grapevine loci (Figure 5). Successful amplification across all methods confirmed that the extracted DNA was free from major PCR inhibitors, although differences in band intensity reflected variations in template purity and concentration.

Figure 5.

Capillary electrophoresis profiles of single PCR products obtained using DNA extracted with the CTAB method and three additional genetic markers: (A) Indel-20 (Ren3/Ren9 loci), (B) GF-09-44 (Rpv10 locus), and (C) GF-09-57 (Rpv10 locus).

3.4. Time and Cost-Effectiveness of DNA Isolation Methods

In addition to analytical performance, the practicality of each method was evaluated in terms of time and cost, as these factors strongly influence method selection for routine laboratory or high-throughput applications. The cost analysis included expenses for reagents, consumables, labor, and equipment depreciation, providing a comprehensive assessment of the cost-effectiveness of each extraction method. Labor cost was estimated at USD 15 per hour, based on the average handling time required for each protocol. Consumables such as tubes, pipette tips, gloves, and disposable filters contributed approximately USD 0.50 per extraction, while equipment depreciation was estimated at USD 0.25 per extraction, assuming a five-year instrument lifespan with about 500 uses per year. The total cost per extraction ranged from approximately USD 1.50 for the CTAB method to USD 8.00 for the Qiagen kit. Overall, all three commercial kits were significantly more expensive than the CTAB-based methods, mainly due to the higher cost of proprietary reagents and columns.

In terms of time efficiency, the Qiagen kit was the fastest, completing DNA extraction in approximately 1 h, followed by the VWR and MP kits (1.15 h and 1.25 h, respectively). The CTAB-based methods required about 3.5 h in total, including 2 h of incubation at the beginning of the procedure. Despite their longer duration, CTAB-based protocols consistently produced DNA of higher purity and yield, offering the most favorable balance among cost, efficiency, and DNA quality. Detailed cost and time data for each method are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cost and time for DNA isolation through different methods.

Considering the balance between reagent cost, processing time, and DNA quality, the CTAB method is the most cost-effective option for small- to medium-scale applications, while commercial kits are suitable for rapid or automated workflows.

3.5. Method Selection and Practical Implications

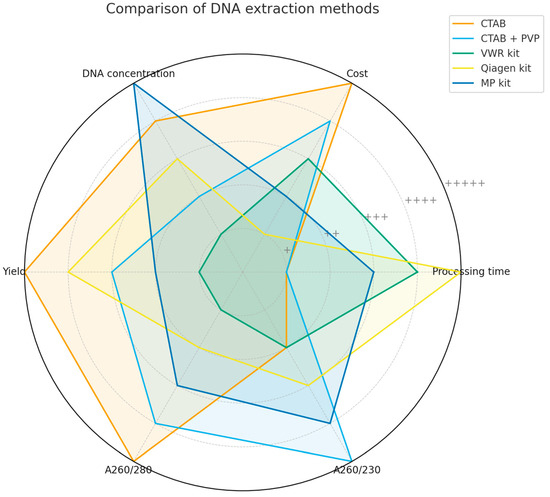

Table 4 summarizes the comparative performance of five DNA extraction methods (CTAB, CTAB + PVP, VWR kit, Qiagen kit, and MP kit) across eight parameters: processing time, cost, DNA concentration, yield, A260/280 and A260/230 purity ratios, PCR performance, and DNA integrity. Rankings are expressed from + (lowest performance) to +++++ (highest performance) to provide a uniform assessment of the methods.

Table 4.

Ranking of five DNA extraction methods (CTAB, CTAB + PVP, VWR kit, Qiagen kit, and MP kit) according to processing time, cost, DNA concentration, yield, purity ratios (A260/280 and A260/230), PCR performance, and DNA integrity.

The CTAB method achieved the highest overall ranking by combining excellent DNA yield, high purity (with both A260/280 and A260/230 within acceptable ranges), outstanding PCR performance, and DNA integrity, while also being the most cost-effective. Its main limitation was the long processing time, but this drawback was outweighed by the superior DNA quality and yield, making it the most reliable and balanced option among the tested methods. The CTAB + PVP method also performed well, particularly in terms of A260/230 ratios and PCR success, but its lower DNA yield and concentration placed it in an intermediate rank. The addition of PVP likely reduced polyphenolic contaminants and improved purity, but this came at the expense of overall recovery. The Qiagen kit was the fastest protocol, achieving DNA extraction in just one hour, and showed strong yield and PCR performance. However, its high cost and suboptimal A260/280 values reduced its overall ranking. In contrast, the MP kit excelled in DNA concentration and A260/230 ratios, but the low integrity of extracted DNA significantly compromised its overall performance, highlighting the importance of assessing DNA quality beyond yield and purity.

The VWR kit consistently ranked lowest, producing the poorest results for DNA concentration, yield, and purity. Although PCR amplification was successful and processing time was shorter than with CTAB-based protocols, the generally poor DNA quality and integrity make this method unsuitable for applications requiring reliable downstream performance.

The radar chart (Figure 6) offers a graphical overview of these rankings, clearly illustrating the overall superiority of the CTAB method, the complementary strengths of the MP and Qiagen kits, and the significant weaknesses of the VWR kit. The consistent PCR success across all protocols indicates that each method can produce DNA suitable for amplification. However, for long-term applications such as sequencing, genotyping, or large-scale molecular studies, DNA integrity and purity become critical factors.

Figure 6.

Radar chart comparing five DNA extraction methods across eight parameters: processing time, cost, DNA concentration, yield, A260/280, A260/230, PCR performance, and DNA integrity. The scale ranges from + (lowest performance) to +++++ (highest performance).

Taken together, the results demonstrate that while all tested methods can produce PCR-compatible DNA, the CTAB method provides the best balance of cost, yield, purity, and DNA integrity, making it the most suitable choice for routine laboratory use. The Qiagen and MP kits may be chosen when speed or concentration is prioritized, whereas the VWR kit appears to be the least favorable option.

3.6. Validation of the CTAB Method Across Different Grapevine Cultivars

To evaluate the robustness and reproducibility of the CTAB method, DNA was extracted from young leaves of 34 grapevine cultivars, including Muscaris, which served as the reference cultivar in earlier experiments (Table 5). Including multiple cultivars, both resistant hybrids and traditional varieties, allowed validation of the protocol across a genetically diverse panel representing different breeding backgrounds.

Table 5.

Validation of the CTAB method across different grapevine cultivars: DNA concentration, yield, and purity ratios (A260/280 and A260/230) obtained from young leaves.

The results confirmed that the CTAB method consistently produced high DNA concentration and yield across all cultivars. DNA concentrations ranged from 185.00 ng/µL in Sirius to 257.00 ng/µL in Sauvignon Kretos, while yields ranged from 370.00 ng/mg to 514.00 ng/mg, with the reference cultivar Muscaris close to the mean (239.50 ng/µL; 479.00 ng/mg). The relatively narrow range of variation across cultivars demonstrates that the method is not sensitive to differences in genotype, leaf morphology, or leaf physiology, confirming its reproducibility. Purity ratios were consistently within the expected range for high-quality DNA. The A260/280 ratio ranged from 1.81 to 1.99, with most values clustering around the ideal of ~1.85–1.95. Lower values (e.g., Sirius and Regent) indicated trace protein contamination, while higher ratios (e.g., Cabernet Volos, Phoenix, Orion) may reflect small amounts of RNA or phenolic carry-over. However, none of these deviations were substantial enough to compromise DNA usability. The A260/230 ratios ranged from 1.95 to 2.09, aligning with the expected purity range for polysaccharide- and polyphenol-free DNA. These results indicate that the CTAB method effectively removes major contaminants across cultivars, yielding DNA suitable for sensitive downstream applications. The robustness of the CTAB method is further demonstrated by the fact that cultivars with diverse metabolic profiles—from resistant hybrids such as Bianca, Merzling, and Solaris to traditional wine cultivars like Graševina—all yielded DNA of comparable quality. Even in cultivars known for higher phenolic content, purity ratios remained consistent, confirming that the protocol can be applied without major modifications. This broad applicability is critical for molecular breeding programs that require reliable DNA extraction across hundreds of genotypes. The validation results also show that CTAB can serve as a standardized extraction protocol for grapevine, ensuring comparability across experiments, research groups, and laboratories. Its ability to deliver reproducible DNA yields and purity from a wide range of cultivars makes it particularly well-suited for large-scale studies, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS), genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS), marker-assisted selection, and population genetics. In summary, validation across 34 grapevine cultivars confirmed that the CTAB method provides robust, reproducible, and high-quality DNA extractions independent of genotype. This establishes CTAB as a reliable reference method for grapevine molecular biology, suitable for controlled laboratory experiments, breeding programs, and large-scale genetic analyses where consistency across diverse germplasm is essential.

Although this study did not include validation on fully automated or robotic extraction platforms, the comparative evaluation was conducted under conditions representative of a high-throughput workflow. DNA was isolated from 34 grapevine genotypes, each processed in three replicates, with up to 48 samples extracted in a single day using the optimized CTAB protocol. To increase efficiency and consistency, a multichannel pipette was used for simultaneous reagent dispensing and transfer steps, introducing a semi-automated element to the workflow. The consistent DNA yield and purity across all samples demonstrate that the method performs reliably under increased sample throughput and can be readily adapted for further automation or larger-scale applications in future studies.

4. Conclusions

This study comprehensively evaluated five DNA extraction methods—CTAB, CTAB + PVP, VWR kit, the Qiagen kit, and the MP kit—across different grapevine tissues and cultivars. The results showed that although all methods produced DNA suitable for PCR amplification, their performance varied significantly in yield, concentration, purity, integrity, time, and cost.

Under the experimental conditions of this study, the CTAB method generally provided the best overall performance, combining high DNA yield, excellent purity, robust integrity, and the lowest cost. Although it required a longer processing time, this was outweighed by the superior DNA quality obtained, making it the most reliable option for routine laboratory use and demanding downstream applications. The Qiagen kit was the fastest method, offering high yield and reproducibility, making it suitable for high-throughput workflows, although its higher cost and moderate purity limited its overall ranking. The MP kit produced the highest concentrations but was penalized for lower DNA integrity due to the aggressive homogenization system. The CTAB + PVP method improved DNA purity in tissues rich in polyphenols, such as mature leaves and wood, though at the expense of yield. In contrast, the VWR kit consistently ranked lowest, producing lower yields and purity values, and is therefore not recommended for applications requiring high-quality DNA.

Validation across 34 grapevine cultivars further confirmed the robustness and reproducibility of the CTAB method, with consistent DNA yields and purity observed regardless of genetic background or metabolic diversity. This demonstrates that, within the scope of this work, the CTAB protocol is broadly applicable and reliable across a wide range of grapevine germplasms, supporting its use in molecular breeding, marker-assisted selection, and genome-wide studies.

Taken together, these findings highlight that while all tested methods were adequate for PCR-based applications, the CTAB method performed best for most evaluated metrics under the tested conditions, offering the most advantageous balance of cost, yield, purity, and reproducibility. For laboratories prioritizing throughput or speed, the Qiagen kit is a viable alternative, whereas the MP kit may be considered when high concentrations are required, though caution is needed regarding DNA fragmentation.

Future research should focus on developing tissue-specific DNA extraction strategies, as biochemical and structural variability among grapevine tissues (such as young leaves, mature leaves, stems, and wood) can influence extraction efficiency and DNA quality. Targeted optimization could further improve reproducibility and expand the applicability of standardized extraction workflows.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations12110316/s1, Figure S1: Original unprocessed gel image of agarose gel electrophoresis (0.5%) of genomic DNA extracted from grapevine leaves using CTAB, CTAB + PVP, VWR kit, Qiagen kit, and MP kit. Lane M represents the molecular weight marker (20 kbp ladder); Figure S2: Original unprocessed gel image of PCR amplification of the SSR marker Indel-27 (Ren9 locus) from DNA isolated with the five tested methods. Lane M indicates the molecular weight marker (1500–100 bp ladder); Table S1: SSR primer sequences, associated loci, and amplification parameters used for PCR validation.

Author Contributions

I.T. and D.P. conceived and planned the study. N.B. and I.Š. conducted the analysis. N.B. and I.Š. interpreted the results and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. I.T. and D.P. edited and finalized the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Croatian Science Foundation, grant number IP-2022-10-9428 project “Application of metabolomics, high-throughput phenotyping and molecular markers in early selection for disease resistance in the development of new grape varieties—VitiResist” and by Research and Development of Plant Genetic Resources for Sustainable Agriculture, Center of Excellence for Biodiversity and Molecular Plant Breeding (CoE CroP-Bio-Div), Zagreb, Croatia (PK.1.1.10.0008).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dellaporta, S.L.; Wood, J.; Hicks, J.B. A plant DNA minipreparation: Version II. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 1983, 1, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 1990, 12, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi, M.A.; Ye, G.-N.; Weeden, N.F.; Reisch, B.I. A simple and efficient method for DNA extraction from grapevine cultivars and vitis species. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 1994, 12, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Padh, H.; Shrivastava, N. Plant genomic DNA isolation: An art or a science. Biotechnol. J. Healthc. Nutr. Technol. 2007, 2, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Ram, C.; Singh, S.; Rana, M. Plant genomic DNA isolation—The past and the present, a review. Indian J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2018, 31, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Hammar, S.; Grumet, R. A quick and inexpensive method for removing polysaccharides from plant genomic DNA. Biotechniques 1992, 13, 52–54+56. [Google Scholar]

- Porebski, S.; Bailey, L.G.; Baum, B.R. Modification of a ctab DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 1997, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lee, C.; Shin, J.; Chung, Y.; Hyung, N. A simple and rapid method for isolation of high quality genomic DNA from fruit trees and conifers using pvp. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 1085–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, S.L.; Alfonzo, A.; Conigliaro, G.; Moschetti, G.; Burruano, S.; Barone, A. A simple and rapid DNA extraction method from leaves of grapevine suitable for polymerase chain reaction analysis. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeke, T.; Jenkins, G.R. Influence of DNA extraction methods, pcr inhibitors and quantification methods on real-time pcr assay of biotechnology-derived traits. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 396, 1977–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labra, M.; Carreno-Sanchez, E.; Bardini, M.; Basso, B.; Sala, F.; Scienza, A. Extraction and purification of DNA from grapevine leaves. Vitis 2001, 40, 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.K.; Lavanya, M.; Anjaiah, V. A method for isolation and purification of peanut genomic DNA suitable for analytical applications. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2000, 18, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, B.M.; Salleh, F.M.; Wagiran, A.; Abba, M. Comparative evaluation of different DNA extraction methods from E. Longifolia herbal medicinal product. EFood 2021, 2, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Hong, X.; Khayatnezhad, M.; Ullah, F. Genetic diversity and comparative study of genomic DNA extraction protocols in Tamarix L. Species. Caryologia 2021, 74, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, A.; Osman, G. Comparison of three genomic DNA extraction methods to obtain high DNA quality from maize. Plant Methods 2017, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, H.; Cao, Y.; Ma, G.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, H.; Song, X.; Sui, S. Reducing costs and shortening the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (ctab) method to improve DNA extraction efficiency from wintersweet and some other plants. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsal, G.; Baiges, I.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F.; Fort, F. A fast, efficient method for extracting DNA from leaves, stems, and seeds of Vitis vinifera L. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2011, 62, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsal, G.; Boronat, N.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F.; Fort, F. Comparison of the efficiency of some of the most usual DNA extraction methods for woody plants in different tissues of Vitis vinifera L. OENO One 2013, 47, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minas, K.; McEwan, N.R.; Newbold, C.J.; Scott, K.P. Optimization of a high-throughput ctab-based protocol for the extraction of qpcr-grade DNA from rumen fluid, plant and bacterial pure cultures. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 325, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenk, J.J.; Becklund, L.E.; Carey, S.J.; Fabre, P.P. What is the “modified” ctab protocol? Characterizing modifications to the ctab DNA extraction protocol. Appl. Plant Sci. 2023, 11, e11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiya Thodiyil, J.; Edathumthazhe Kuni, S.; Nediyaparambu Sukumaran, P. A modified ctab method for extracting high-quality genomic DNA from aquatic plants. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedrina-Okutan, O.; Novello, V.; Hoffmann, T.; Hadersdorfer, J.; Occhipinti, A.; Schwab, W.; Ferrandino, A. Constitutive polyphenols in blades and veins of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) healthy leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 10977–10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboul-Maaty, N.A.-F.; Oraby, H.A.-S. Extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from different plant orders applying a modified ctab-based method. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, A.; Furtado, A.; Cooper, T.; Henry, R.J. Protocol: A simple method for extracting next-generation sequencing quality genomic DNA from recalcitrant plant species. Plant Methods 2014, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Chen, J. A high throughput DNA extraction method with high yield and quality. Plant Methods 2012, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova-Gascón, J.; Ferrer-Martín, C.; Bernad-Eustaquio, A.; Elbaile-Mur, A.; Ayuso-Rodríguez, J.M.; Torres-Sánchez, S.; Jarne-Casasús, A.; Martín-Ramos, P. Behavior of vine varieties resistant to fungal diseases in the somontano region. Agronomy 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, E.; Dolzani, C.; Stefanini, M.; Gratl, V.; Bettinelli, P.; Nicolini, D.; Betta, G.; Dorigatti, C.; Velasco, R.; Letschka, T. R-loci arrangement versus downy and powdery mildew resistance level: A vitis hybrid survey. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).