Abstract

Surfactants are chemical compounds present in a large number of products that people use on a daily basis, starting with detergents for washing clothes, dishes, personal hygiene products, etc. Some products also contain certain heavy metals. Their uses cause heavy contamination of wastewater that must be purified before discharge into receivers. Given that some types of surfactants are very persistent and heavy metals are non-biodegradable and toxic even in small concentrations, the purification process requires a complex approach and a combination of different methods. Bioremediation, as an environmentally acceptable and economically clean technology, has great potential. It is based on the use of indigenous microorganisms that have developed different mechanisms for breaking down and removing or detoxifying a large number of pollutants and are excellent candidates for bioremediation of wastewater. Bacteria can degrade surfactants as sole carbon sources and exhibit tolerance to various heavy metals. This paper summarizes the most significant results, highlighting the potential of bacteria for the biodegradation of surfactants and heavy metals, with the aim of drawing attention to their insufficient practical application in wastewater treatment. Bioreactors and microbial fuel cells are described as currently relevant strategies for bioremediation.

1. Introduction

Surfactants (SFs) are synthetic or natural chemical compounds present in various products (shampoos, dishwashing and laundry detergents, toothpastes, etc.) that are part of daily use. The widespread use of these chemicals has also led to an increase in their production, showing a sharp increase in recent years. After use, these compounds end up in wastewater, sewage, and industrial effluents, which are further purified in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) where they are treated by physical, chemical, and biological methods [1]. However, although the largest quantity of SFs is removed in WWTPs, some toxic products may remain that have a harmful effect on living organisms and the environment when they reach the recipients (surface water, groundwater, and soil). It has been proven that even small concentrations of SFs cause toxic effects on living beings. When SFs reach the water surface, the surface tension decreases, foam appears, the amount of oxygen decreases, hypoxic conditions are created, and aquatic organisms die. The toxic effects of SFs depend on their chemical structure and ability to adsorb to cell membranes and penetrate into the cell interior, thereby disrupting the functionality and structure of the cell membrane. The toxicological properties of SFs depend not only on their structure or class but also on the applied concentration, the time period of exposure, and the type of organism [2].

Heavy metals (HMs) are inorganic elements ubiquitous in nature. Some of them (sodium, calcium, potassium, iron, copper, magnesium, zinc, and chromium) are necessary for the physiological and biochemical functions of cells at low concentrations but become toxic at high concentrations, while others (cadmium, mercury, nickel, lead, and the metalloid arsenic) are toxic even at low concentrations [3]. HMs find their way into wastewater via industrial effluents (including metal plating, mining, and production) as well as natural and urban sources (such as weathering, urban runoff, and residential waste). Wastewater from households, hotels, hospitals, laundries, the detergent industry, etc., contains HMs and differs in its qualitative and quantitative compositions. HMs do not decompose and have the property of accumulating and settling. Their presence in aquatic ecosystems exerts toxic effects on living beings and leads to changes in biodiversity. Wastewater from laundries contains a higher quantity of HMs because the laundry industry generates a large amount of wastewater, while graywater contains a lower quantity of HMs. However, direct discharge of graywater into aquatic ecosystems without adequate treatment further burdens the environment with pollutants because the presence of HMs, phosphates, SFs, and other components found in washing and cleaning agents reduces the biodegradability capacity of graywater [4]. As a result, there may be an accumulation of HMs and an increase in the level of toxicity in living beings (microorganisms, plants, animals, and humans).

In order to minimize the harmful effects of SFs and HMs, new methods and technologies are being developed that have the task of removing all SFs and HMs and obtaining recycled water that can be used again. However, removing SFs from wastewater represents a great challenge for scientists because some classes of SFs are quite stable chemically and structurally, which makes access to microorganisms difficult and causes a lower level of degradation, i.e., lower efficiency of SF removal during conventional purification processes. However, many microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, and microalgae) have adapted to the presence of SFs in their environment due to selective pressure and have developed an enzymatic system that can degrade these chemicals to some extent or completely [5,6]. This process is known as biodegradation and can occur under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Unlike SFs, HMs are not biodegradable; however, bacteria have developed various ways to remove or detoxifying them from the aquatic environment: bioadsorption (biosorption), bioaccumulation, bioleaching, and bioprecipitation [7].

In this work, the focus is on bacteria that are the only ones that can use SFs as the sole source of carbon and energy and are known to be good degraders. Previous studies have provided a wealth of information on bacterial isolates that degrade SFs either alone or in association with other intra- and interspecies organisms. In addition, numerous studies have proven and highlighted the importance of bacterial isolates in the elimination of HMs from aqueous solutions or wastewater [8]. However, regardless of the knowledge that exists, the practical application of bacteria in the removal of SFs and HMs is still limited and underutilized. Therefore, this paper aims to summarize the current knowledge about the potential of bacteria to remove the mentioned pollutants and current strategies for the bioremediation of pollutants (bioreactors and microbial fuel cells (MFCs)). Living and non-living cells, free, planktonic organisms, and biofilms can participate in bioremediation.

2. Bioremediation

Bioremediation is a biotechnological process that serves to eliminate, mineralize, degrade, and neutralize various pollutants of organic and inorganic origin, being used in the purification of wastewater and contaminated environments by the action of biological agents (bacteria, fungi, and algae) [9]. The success of bioremediation technology is influenced by numerous factors that can be divided into two groups: biotic and abiotic. Biotic factors include the chemical composition of the microorganism’s cell wall, the secretion of specific proteins (enzymes), the ability to form a biofilm, and its exopolysaccharides (EPSs). Of the abiotic factors that influence bioremediation, the following stand out: pH, temperature, moisture, the presence or absence of oxygen, chemical compositions of pollutants and their availability for microorganisms, and the ratio of nutrients [10]. Given that bacteria can degrade SFs in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, electron acceptors (oxygen in the first case and nitrates or sulfates in the second case) have a significant influence on the success of bioremediation.

Living and non-living cells, free planktonic organisms, biofilms, and free or immobilized enzymes can participate in bioremediation. The use of microbial biofilms in bioremediation has proven to be more effective in removing pollutants for several reasons: they are more tolerant to pollutants, have a high survival rate in extreme environmental conditions, and provide a safe environment for the community [11,12,13,14]. Biofilms have a properly regulated gene expression pattern mediated by quorum sensing; biofilm communities are very suitable for the sorption and metabolism of organic pollutants [15,16].

Biofilm bioreactors have a higher concentration of biomass than suspended biomass reactors, providing enhanced protection to the cells against chemical damage. Biofilms constitute an effective structural community for the breakdown of diverse toxic substances. The physicochemical composition of the biofilm matrix facilitates the optimization of compound availability and adsorption while simultaneously enabling the coexistence of both aerobic and anaerobic bacterial populations.

2.1. Surfactants

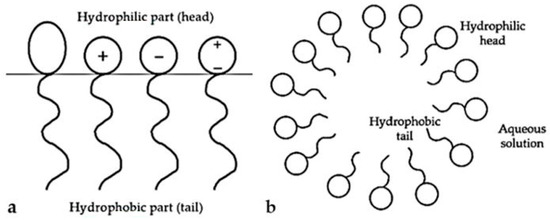

SFs are organic amphiphilic compounds whose molecules contain two parts, hydrophobic (lipophilic) and hydrophilic (Figure 1). The hydrophilic part (head) is soluble in water and consists of various porous chemical groups (hydroxyl, carboxyl, amine, etc.). The hydrophobic part of the molecule (tail) is insoluble in water but soluble in fats, and this part of the molecule is characterized by the presence of non-polar groups (alkyl, aryl, and others). Depending on the characteristics of the hydrophilic part, four classes of SFs are distinguished: anionic, cationic, non-ionic, and amphoteric [17]. The dissolution of SFs in an aqueous solvent leads to a decrease in surface tension and the appearance of wetting and foaming. Thanks to this, they can easily concentrate at the boundaries between bodies or droplets of water and hydrophobic substances such as oil or lipids and act as an emulsifier or foaming agent. Anionic SFs are characterized by the presence of a negative charge on the hydrophilic head in solution. They are widely used in various industrial branches: detergent, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, food, etc. Cationic SFs in aqueous solution dissociate into positively charged ions. They are most commonly used as softeners, antistatics, and fungicides. Non-ionic SFs are neutral molecules by nature; therefore, they cannot dissociate in aqueous solution but are very stable molecules. They are resistant to water hardness and the effects of acids and bases, which makes them particularly suitable for use in the textile, food, and medical industries. Amphoteric SFs carry a positive and negative charge on the hydrophilic part of the molecule, with a net charge of zero. They retain their properties in a wide range of pH values. This surfactant type includes amphoteric SFs (amphoterics) and amphoteric ionic SFs (zwitterionics). They are most commonly used in the cosmetic industry [18].

Figure 1.

Surfactants parts: (a) hydrophobic and hydrophilic (non-ionic, cationic, anionic, and amphoteric); (b) hydrophilic part (head) is soluble in water and the hydrophobic part of the molecule (tail) soluble in fats.

After the use of products containing SFs, they reach the sewage system or are directly discharged into the aquatic environment and are transformed by physical and chemical processes, which may cause their increased mobility and express a harmful effect on living beings and the environment [19]. The concentration of SFs depends on surfactant type, source of discharge, and world parts (geographic locality). Typically, industrial effluents exhibited higher levels of SFs compared to alternative sources. Exemptions to this rule were observed for anionic SFs. For illustration, the concentration of anionic SFs measured in industrial effluents from a detergent factory was lower compared to other artificial wastewater sources [20].

The negative effects of elevated concentrations of SFs and their degradation products are manifested in all living beings, from microorganisms to humans. They are reflected in the disruption of microbial dynamics and their biogeochemical processes, in the disruption of plant survival processes and their ecological niches, and in the slowing down of the function of organs and organ systems in humans [21].

The efficiency of different types of microorganisms, either individually or in consortia, isolated from wastewater polluted by detergents and SFs in the degradation of SFs has been the subject of numerous studies [5,6,22]. The results of bacterial efficiency are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Capacities of individual and mixed bacterial strains for biodegradation of anionic SFs.

Table 2.

Capacities of individual and mixed bacterial strains for biodegradation of non-ionic, cationic, and zwitterionic SFs.

2.1.1. Capacity of Free and Immobilized Bacterial Cells for SF Removal

The efficiency of individual strains in the biodegradation of SFs varies depending on the type of bacteria and their ecology, the type and chemical composition of pollutant, its concentration, and experimental conditions (pH, temperature, agitation, presence of additional nutrients, and incubation time). In general, individual species of bacteria have a limited degradation power that is defined by the specific enzyme system participating in the degradation of pollutants up to a certain step. Therefore, the complete degradation of complex pollutant molecules or their mixtures represents a challenge for a single strain. Most often, pollutants are degraded to intermediates that can have a toxic effect. This phenomenon affects the lower stability and resistance of individual strains when faced with changing environmental conditions compared to a diverse consortium.

The efficiency of the biodegradation of SFs is mainly determined by the hydrophobic groups. Sodium dodecyl sulfonate (SDS) is an anionic substance of the alkyl sulfonate type that is easily and efficiently degraded in a short time, and alkyl sulfatase plays a key role [82]. So far, various strains of bacteria have been identified that effectively remove SDS. The strains of the genus Pseudomonas (Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas jessenii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, etc.) are predominant in studies. P. putida SP3 (isolated from India) has been shown to be effective in the complete degradation of SDS at concentrations of 0.1 to 0.3%, with higher concentrations requiring longer incubation times (16–24 h). The specific activity of alkyl sulfatase in the exponential phase was 0.087 ± 0.004 µmol SDS/mg protein/min [83]. In another study [26], Chaturvedi and Kumar isolated several bacterial strains that degrade SDS from different detergent-contaminated lakes in India. These isolates also belonged to the genus Pseudomonas: P. aeruginosa, P. mendocina, P. stutzeri, P. alcaligenes, P. pseudoalcaligenes, P. putida, and P. otitidis. This biodegradation study showed that in the presence of SDS (0.1%), the isolates showed different degradation rates, ranging from 97.2% to 19.6% after 12 h of incubation under identical conditions. The degradation efficiency was correlated with alkyl sulfatase activity (0.168 ± 0.004 to 0.024 ± 0.005 μmol SDS/mg protein/min). The highest degradation rate was shown by P. aeruginosa, followed by P. otitidis and P. mendocina, and the lowest rate was recorded by JN3. Bacillus cereus (isolated from a lake polluted with wastewater from a detergent factory, India) recorded a growth of 43% in the presence of SDS at a concentration of 0.001%. This species actively degrades SDS in as little as 8 h, yielding dodecanol that continues to be metabolized in the absence of additional carbon sources [84]. The authors concluded that alkylsulfatase appears after 1 h of incubation and that it is an inducible enzyme.

Among the efficient SDS degraders, P. aeruginosa MTCC 10311, isolated from detergent-contaminated soil (India), should be noted, which degraded SDS at an initial concentration of 0.15% in only 2 days of incubation at 30 °C, with a degradation rate of 96% [24]. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain KIK-12 (isolated from contaminated soil, Nigeria) was able to grow and completely degrade 0.05% SDS following 7 days of incubation [38]. Recently, the capacity of Enterobacter cloacae sp. strain AaMa and the optimal conditions for SDS degradation were described in work [85]. The E. cloacae sp. strain AaMa was isolated from a detergent-contaminated soil sample (Malaysia). Examining the conditions favorable for biodegradation, the authors determined that the best results were obtained at pH 7.5, a temperature of 30 °C, and with the addition of sodium nitrate. The kinetic parameters Km (app) and Vmax (app) of the SDS-degrading enzyme (alkylsulfatase) were also calculated (0.1035 mM and 0.4851 µmol SDS per minute per mg protein, respectively). These studies indicated that detergent-contaminated soil is also a source of SDS-biodegrading microorganisms.

Klebsiella oxytoca DRY14 (isolated from detergent wastewater from a car wash in Malaysia) showed a high degree of degradation of 0.2% SDS after 4 days of incubation (80%), while after 10 days of incubation, all SDS was degraded [29]. The optimal conditions for SDS biodegradation were pH 7.5, 37 °C, and the addition of ammonium sulfate (0.2%). The growth of Klebsiella oxytoca was completely inhibited at 1% SDS.

Othman et al. [28] investigated the ability of a surfactant-degrading bacterium, Serratia marcescens strain DRY6, to remove SDS at different concentrations (0.05–0.25%) for 10 days and found that the bacteria had almost complete biodegradation capacity in 6, 8, and 10 days at concentrations of 0.05, 0.075, and 0.1%. After 10 days of incubation, the best biodegradation capacity was observed at 0.1% SDS, while with increasing SDS concentration, biodegradation decreased and was inhibited at concentrations higher than 0.25%.

Delftia acidovorans (isolated from a detergent-contaminated river water in Turkey) also showed success in degrading SDS, degrading 87% of 1% SDS after 11 days of incubation [32]. Bacillus, Enterobacter, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas bacteria were also isolated from river water and degraded SDS and detergents. Osadebe et al. [42] tested the biodegradability of domestic and imported brands of detergents and SDS using bacteria isolated from the New Calabar River (Nigeria), which receives household wastewater containing detergents. The bacteria were able to grow in the presence of detergents at a concentration of 0.0003%, regardless of their origin; however, domestic brands of detergents had a lower growth rate than SDS and imported brands. The concentration of undegraded anionic components in detergents was determined using the methylene blue active substance (MBAS) method after 28 days of incubation. The results showed that the bacteria degraded SDS in the highest concentration (97%), followed by imported detergents (92–95%), with domestic detergents the least (56–85%). They concluded that domestic brands of detergents contain poorly degradable anionic SFs, which pose a threat to the environment and human health, living beings, etc.

In another study [2], two bacterial isolates originating from the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean were tested for SDS degradation. The best SDS-degrading strains were Staphylococcus saprophyticus ASOI-01 and Bacillus pumilus ASOI-02, with degradation efficiencies of 88.9% and 93.4%, respectively (at an initial SDS concentration of 0.01%) at 20 °C and pH 7. However, testing of strains on wastewater samples showed lower biodegradation efficiency for strains ASOI-01 (76.83) and ASOI-02 (64.93%). This study demonstrated the potential use of extremophilic microbes in sustainable wastewater management.

The efficiency of linear alkylbenzene sulfonates (LASs) degradation is influenced by their molecular structure, i.e., the position of the benzene ring in the molecule. Molecules in which the benzene ring is further away from the central carbon atom are more easily degraded. Also, the degradation of the benzene ring is a factor that limits biodegradation. In prokaryotic cells, dioxygenases oxidize the benzene ring, after which it is degraded by the ortho- or meta-pathway. Ashok et al. [49] conducted a study to investigate the degradation efficiency of 1% LASs by free and immobilized bacterial cells, Pseudomonas nitroreducens (L9) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (L12). They determined that the efficiency of free cells in the decomposition of LASs was approximately equal—57.35% (L9) and 57.41% (L12)—but weaker compared to the efficiency of immobilized cells. The nature of the immobilizing material affects the efficiency of LAS degradation differently depending on the type of microorganism. The species L9 immobilized in alginate degraded a significantly higher amount of LASs (85.16%) compared to PVA (58.54%). Conversely, species L12 immobilized in PVA was more effective in degrading LASs (62.98%) compared to alginate (61.07%), but the differences were not significant.

The species B. licheniformis (isolated from car wash effluents, Iran) proved successful in biodegradation of LASs (86%), at a concentration of 0.01% after 8 days of incubation [46,62].

Among non-ionic SFs, APEOs and NPEOs are the most complex and poorly biodegradable, while linear alcohol polyglycol ethers (AEs) are the best degraded. Prats et al. [86] showed that under temperature-controlled conditions, more than 90% of alcohol ethoxysulfates (AESs) were degraded in the presence of Pseudomonas sp. The biodegradation of APEOs is affected by the length and complexity of the alkyl chain, the number of elements in the benzene ring, and the polyoxyethylene chain. Some of the strains capable of degrading APEOs are Pseudomonas sp., Moraxella osloensis, Cupriavidus sp., and Brevibacterium sp. TX4. NPEOs are degraded by Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, K. pneumoniae (Yas1), and P. fluorescens (Yas2) (Table 2).

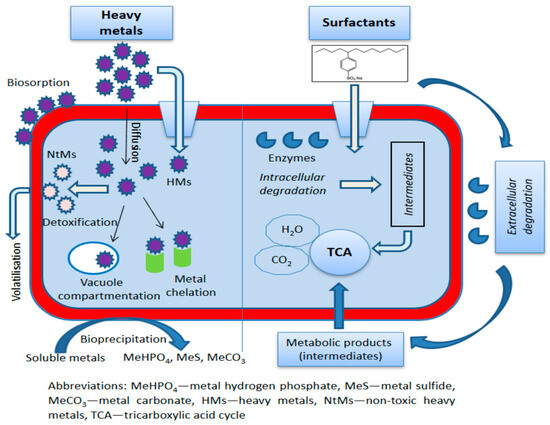

The presented results clearly show that certain genera of bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Bacillus, are very effective in the degradation of anionic (SDS and LAS) and non-ionic surfactants (AES). They have been exposed to a wide variety of pollutants over time, leading to the development of diverse enzymatic pathways. They possess a wide spectrum of enzymes (extracellular and intracellular) that can break down different types of SFs, allowing them to thrive in environments with mixed contaminants (Figure 2). Other bacterial genera are less versatile and are narrowly specialized to degrade only certain types of SFs. This specialization is often a result of adapting to specific long-term environmental conditions where only certain pollutants were present.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of some possible mechanisms of bioremediation of HMs and SFs.

2.1.2. Capacity of Metal-Tolerant Bacteria for SF Removal

Metal-tolerant bacteria can tolerate high concentrations of both SFs and HMs, allowing them to survive and function in environments where other microbes would be inhibited. These bacteria can break down SF molecules, reducing their concentration and potential toxicity in wastewater. The capacity of these bacteria to address both SFs and HMs in a single process makes them a promising tool for treating wastewater from sources like laundry environments, which often contain both types of pollutants. Utilizing bacteria with dual tolerance can lead to more efficient and cost-effective wastewater treatment compared to using separate methods for SF and HM removal. Unfortunately, this phenomenon is still not sufficiently researched.

Adekanmbi et al. [36] conducted a study based on determining the efficiency of metal-tolerant bacteria to degrade SDS in the presence of metals (Cu, Zn, and Cd). Two bacterial species isolated from laundry wastewater were tested: Paenibacillus amylolyticus BAL1 and Bacillus lentus BAL2. The experiment was conducted under aeration conditions (250 rpm) for 14 days, and the bacteria were tested individually and in community. The best degradation efficiency was achieved by B. lentus (54.9%), followed by P. amylolyticus (49.90%), while the combined culture degraded only 44.3% of SDS. In this case, combining the cultures did not improve SDS degradation, probably due to the antagonism between the mentioned cultures. Metabolism products of one species can inhibit the metabolism of another species in the community. It is also possible that the mentioned metals inhibit the key enzymatic reactions in the degradation of SDS. The last statement is supported by the results of Rusnam et al. [87], which examine the ability of a bacterial species isolated from rice field water (tentatively named Pseudomonas sp. strain Maninjau1) to degrade SDS as a function of its concentration and the presence of HMs. This study demonstrated the ability to completely degrade SDS at a concentration of 1 g/L in 10 days, while degradation was impossible at 2 g/L. It was determined that silver, copper, cadmium, chromium, lead, and mercury reduce the efficiency of biodegradation by 50%.

Future research should address the question of how the presence of HMs and SFs in a contaminated environment impacts overall bacterial removal effectiveness, given that one contaminant may interfere with the removal of another. Such research should help to improve our understanding of these interactions, with the goal of developing more effective combined bioremediation solutions for eliminating mixed pollutants.

2.1.3. Capacity of Free and Immobilized Bacterial Community in SF Removal

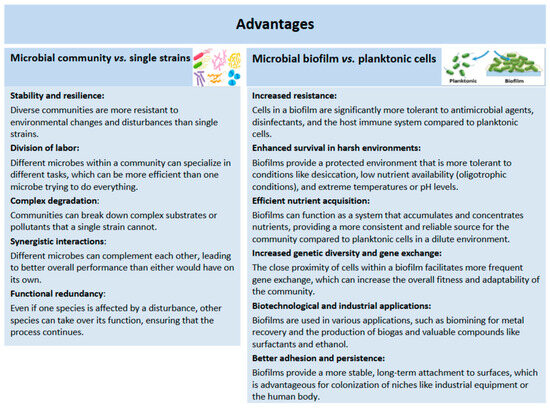

Microbial communities are generally more efficient at biodegrading pollutants than individual species, as confirmed by the results of numerous studies. Key factors that enable better community efficiency include metabolic cooperation between strains, cross-feeding, division of metabolic niches, reduced strain burden, and increased adaptability of the entire system [88]. Synergistic interactions are established between different strains that link their metabolic and biosynthetic pathways so that the intermediates produced by some members of the consortium can be food for others, which contributes to the rapid and more efficient degradation of pollutants [22]. In this way, the range of usable substrates is expanded and helps to remove inhibitory byproducts, increasing the efficiency of degradation. On the other hand, the metabolic burden of any one organism is reduced, which makes the entire community more stable and resistant to changes in the environment. Moreover, the sharing of niches among different strains allows for the simultaneous use of complex mixtures of substrates and the efficient degradation of compounds that would be challenging for a single strain [89]. The advantages of mixed communities versus single species, as well as biofilm versus planktonic species, are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A review of the advantages of mixed communities versus single species as well as biofilms versus planktonic species in bioremediation.

We presented several examples that clearly document the better efficiency of degradation of more complex SFs by the effect of mixed cultures in comparison with individual species. A study [41] confirmed the better efficiency of mixed bacterial cultures in the biodegradation of anionic SFs compared to individual cultures. A combined culture of bacterial isolates originating from wastewater, Serratia spp., Acinetobacter johnsonii, and Pseudomonas betelii, degraded 97.6% of SDS compared to individual species that degraded 91.3%, 94.2%, and 92.4%, respectively, of SDS after 10 days of cultivation. These results clearly indicate the possibility of using the isolates in the degradation of SDS in the treatment of domestic and industrial wastewaters (Table 1). In a study by [42], the effect of free and immobilized mixed bacterial cultures of Pseudomonas mendocina and Bacillus dominanti in the biodegradation of SDS dissolved in synthetic medium (SWW) and automotive workshop wastewater (AWW) and laundry wastewater (LWW) was investigated. Sodium alginate (SA) and a combination of sodium alginate–polyvinyl alcohol (SA–PVA) were used for cell immobilization. In SWW, these types of beads were equally effective in removing SDS at a percentage concentration of 10 mg/L (SA beads—99.63% and SA-PVA beads—99.63%); however, with an increase in the SDS concentration to 100 mg/L, SA beads had slightly better efficiency compared to SA–PVA (85.12% and 83.29%, respectively). A slight advantage of SA immobilization over SA–PVA was also demonstrated in the case of SDS removal in AWW (94.91% and 93.82%, respectively) and in LWW (94.39% and 92.04%, respectively). The efficiency of biodegradation by immobilized biomass was maintained up to five cycles in wastewater (Table 1). Fedeila et al. [44] investigated the efficiency of a consortium of Alcaligenes faecalis, Enterobacter cloacae, and Serratia marcescens, isolated from Algerian industrial wastewater, in removing three types of anionic SFs: sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate (SDBS), SDS, and sodium lauryl ether sulfate (SLES) at a concentration of 0.001%. After 144 h of incubation at optimum circumstances (pH 7.0 and 30 °C), the consortium destroyed 85.1% of SDBS, with a half-life of 20.8 h. E. cloacae and S. marcescens pure cultures performed 46% and 41% less efficiently, respectively. The consortium showed a high SDS degradation rate of 94.2% with a half-life of 9.8 h. Of the individual species, only 23.71% of SDS was degraded by A. faecalis. The consortium exhibited a reduced degradation rate of SLES at 47.53%, attributed to the toxic influence of ether oxide in the chemical composition of SLES (Table 1). In another study by Khleifat [57], the biodegradability of SLES was investigated using two bacterial consortia (Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Klebsiella oxytoca, and Serratia odorifera and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus) whose members were isolated from a WWTP. The bacteria were grown on SLES (0.1–0.7%) containing minimal medium (M9) as the sole carbon source. A faster growth rate (0.26/h) was noted for A. calcoaceticus and K. oxytoca compared to the S. odorifera and A. calcoaceticus co-culture (0.21/h). In the A. calcoaceticus and K. oxytoca co-culture, additional carbon sources in the form of glucose, sucrose, maltose, mannitol, and succinic acid resulted in a threefold higher amount of SLES degraded compared to the medium without added carbon sources. Quite the opposite effects were recorded in S. odorifera and A. calcoaceticus co-cultures, where, apart from maltose, all other carbon sources partially or completely inhibited SLES degradation (25–100%). Maltose in this co-culture increased the efficiency of SLES degradation 5-fold. The biodegradation rates of SLES for individual strains were as follows: K. oxytoca = 19%, S. odorifera = 11%, and A. calcoaceticus = 8%; for two-member communities: A. calcoaceticus + K. oxytoca = 100%, S. odorifera + A. calcoaceticus = 100%, and S. odorifera + K. oxytoca = 25%; and for the three-member community: A. calcoaceticus + S. odorifera + K. oxytoca = 100% (Table 1).

Khleifat [51] conducted a study in which he examined the ability of a bacterial consortium and individual strains to degrade LAS under different conditions, including pH, temperature, aeration, and carbon and nitrogen sources. The consortium consisted of the bacteria Pantoea agglomerans and Serratia odorifera 2 isolated from a WWTP. The bacteria were grown in minimal medium (MM) with LAS (0.02%) as the sole carbon source and in nutrient broth (NB). Depending on the composition of the medium, the consortium degraded about 70% of LAS in NB and 36% of LAS in MM. This study showed that the efficiency of the consortium in degrading LAS is much higher than that of individual species as a result of their catabolic cooperation. Individual cultures degraded only 25–30% and 12–20% of LAS on NB and MM, respectively. Complete mineralization of LAS (0.02%) is possible at a temperature of 32 °C, a stirring speed of 250 rpm, and in the presence of various carbon and nitrogen sources, over a period of 48–72 h (Table 1). In the study of [89], it was confirmed that individual and combined cultures of the following bacterial species—Alcaligenes odorans, Citrobacter diversus, Micrococcus luteus, and P. putida—efficiently decompose LAS in the presence of a biostimulus (inorganic nitrogen: NKT fertilizer). Biodegradation expressed as half-life was ranked as follows: consortium of four species (t½ = 8–12 days), >three-member consortium (t½ = 8–13 days), >two-member consortium (t½ = 10–15 days), and >individuals (t½ = 9–16 days) (Table 1).

Merkova et al. [81] investigated the ability of bacteria from activated sludge of municipal wastewater to degrade a type of amphiphilic SF, cocamidopropyl betaine (CAPB), which is widely used in personal care products. The biodegradation study included two isolates: Pseudomonas sp. FV and Rhizobium sp. FM. The combined cultures of bacteria were grown in a mineral medium with or without a nitrogen source (ammonium salt) and with the addition of CAPB (0.03%). The results of this study showed almost complete mineralization of the SF in the presence of the above species after only 4 days, while in a medium without nitrogen, this process lasted much longer (more than 29 days). In this community, Pseudomonas sp. FV had an initial role in the biodegradation of CAPB and produced intermediates, while Rhizobium sp. FM continued the process of biodegradation of intermediates resulting from primary biodegradation and, in the absence of a nitrogen source, supplied nitrogen to its partner (Table 2).

Bergero and Lucchesi [77] investigated the adsorption and desorption of three quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) onto activated sludge collected from a tank of WWTP from the poultry industry (Argentina). The QACs used in this study were Br-tetradecyltrimethylammonium (TTAB), Cl-tetradecylbenzyldimethylammonium (C14BDMA), and Cl-hexadecylbenzyldimethylammonium (C16BDMA). They found that all three SFs adsorbed rapidly (after 2 h) onto activated sludge and that the adsorption capacity was determined by the hydrophobicity of the SF molecules (C16BDMA = 98%, C14BDMA = 90%, and TTAB = 81%), and that desorption was inversely proportional to the degree of adsorption. After adding QAC-degrading microorganisms, Pseudomonas putida ATCC 12633 and Aeromonas hydrophila MFB03 immobilized in Ca-alginate beads, to wastewater containing activated sludge and TTAB at a concentration of 0.02%, a significant decrease (about 90%) in the adsorption of SF onto activated sludge after 24 h was observed. This decrease in SF concentration after treatment of wastewater with immobilized cells confirms the ability of the consortium to biodegrade QACs (Table 2).

The reported results of bacteria/consortia degrading efficiencies can be used to build a synthetic microbial community that would improve surfactant bioremediation and increase the level of protection for the environment and living beings.

2.1.4. Removal of SFs in Bioreactors

Wastewater treatment using conventional activated sludge (CAS) is not efficient enough for all SFs, and therefore, it is necessary to improve and modernize the treatment process. An example is APEOs and their degradation products (nonylphenols, acid, and base ethoxylates), which are poorly degraded in CAS. In this part, some of the proposed technological solutions for purifying wastewater with SFs are presented, depending on the type of SFs, their concentration, and the type of wastewater. The effectiveness of different aerobic and anaerobic bioreactors in the removal of SFs is shown (Table 3) and discussed.

Table 3.

Efficiencies of individual and bacterial community biofilms for SF removal in different bioreactor types.

Dhouib et al. [54] isolated a strain of Citrobacter braakii (activated sludge, Tunisia) and tested it in bioaugmentation for the treatment of wastewater from the cosmetics industry. This bacterium was previously grown on an anionic SF as the sole carbon source and then tested in a reactor (20 L continuous-flow bioreactor) with different SLES dilutions. The temperature in the reactor was maintained at 30 °C, pH 7.0, and aeration at 250 rpm. C. braakii expressed a biodegradation rate of 0.065 g/lh, with a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of about 20 h. However, a much more efficient and economical solution was connecting the bioreactor with a mineral microfiltration membrane (TAMI Industries Alumine-membrane: 245 mm length, 10 mm diameter, and 0.2 µm pore size), which improved the SLES elimination efficiency from 0.065 to 0.15 g/l/h and reduced the HRT from 20 to 5 h (Table 3). The authors emphasize that this integrated system can purify wastewater from the cosmetic industry for reuse in industrial processes.

The aforementioned study prompted Karray et al. [91] to continue to investigate the performance of a Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) for the treatment of cosmetic wastewater that contained a large amount of difficult-to-degrade SLES. From the aerobic MBR inoculated with C. braakii and treating wastewater after a period of one year, bacterial cultures that played a dominant role in SLES removal (99.6%) were isolated: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (A4), Pseudomonas stutzeri (A10), Bacillus safensis (A13), and Staphylococcus arlettae (A14). A total of 0.1% of SLES was required for optimal growth of the isolate, while increasing the concentration affected the reduction of the growth of the isolate. While higher concentrations of the pollutant were toxic to individual strains, the consortium of these four species was more effective in reducing 0.3% SLES as the sole carbon source compared to C. braakii.

Mollaei et al. [90] evaluated the performance of a moving-bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) during the biodegradation of sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate (SDBS) at concentrations of 50, 100, 200, 300, and 400 mg/L in aeration conditions at room temperature. The MBBR was inoculated with activated sludge from the WWT of a detergent manufacturer company, and after inoculation, the reactor was operated in batch mode. The media used in the reactor had a specific surface of 535 m2/m3. The nutrient and SDBS were injected at 50 mg/L, and then the reactor was converted to continuous mode, in which the nutrient and pollutant were injected as gravity inlets, and permanent aeration was performed. For concentrations higher than 200 mg/L, this treatment did not give satisfactory results, so the authors recommend the application of this treatment for wastewater containing SDBS in the range of 50–200 mg/L. At an HRT of 24 h, a high quantity of SDBS was removed (99.2%) (Table 3). Compared to other treatments such as activated sludge and electro-Fenton, which are effective in reducing much lower concentrations of SF (5 mg/L and 50 mg/L, respectively), the MBBR gave much better results.

In the research conducted by [92], the possibility of improving the performance of an Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactor (AnMBR) in removing SFs present in graywater (SLS and SLES) by introducing microaeration was examined. This technological procedure was supposed to solve one of the problems observed in anaerobic treatment, which is the accumulation of SFs and other organic compounds. This technique gave good results in the activation and improvement of microbial activities, as a result of which large aggregates of SF molecules were disintegrated, and the concentration of SFs was reduced from 9000 mg/L to 2000 mg/L. Microaeration caused variations in the bacterial community, and the responsibility for the biodegradation of SFs was attributed to the genera Aquamicrobium, Flaviflexus, Pseudomonas, and Thiopseudomonas.

One of the techniques recommended for the successful treatment of graywater containing LAS is the aerobic membrane biofilm reactor (O2-MBfR). A recent study [95] investigated the efficiency of activated sludge in the removal of LAS, the chemical oxygen demand, and nitrogen. The results confirmed the high proportion of living microbial cells in the activated sludge and their metabolic activity in the removal of organic matter and nitrogen. LAS was adsorbed, accumulated, and degraded in the microbial biofilm, which led to a drastic reduction in the LAS concentration in the reactor. In a short period of time (24 h), the active action of the microbial biofilm removed more than 98% of LAS (the ratio of biodegradation to accumulation of LAS in EPSs was 94%: 4%), and the remainder was soluble LAS (less than 1%) (Table 3).

Recently, [71] investigated the removal capacity of three types of SFs commonly found in household cleaning products: anionic, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS); cationic, hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium (CTAB); and zwitterionic, 3-(decyldimethylammonio)-propane sulfonate inner salt (DAPS). The experiment was conducted in an O2-based membrane biofilm reactor (O2-MBfR), with an oxygen supply (1.17 atm) and a liquid flow rate of 150 mL/min. The reactor was inoculated with activated sludge and contained SFs, with a concentration of 1 mM. After inoculation, it was operated in batch mode for 24 h and then in continuous flow mode with an HRT of 12 h. The results confirmed the high removal efficiency of all three SFs in a percentage of at least 98%. Microbial community analysis showed that the presence and biodegradation of each SF affected the composition of the microbial community of the biofilm and the presence of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). This research showed the existence of correlations between the biodegradation of QASs and the proliferation of ARG, especially in the case of CTAB, which indicates a danger to human health. The composition of the biofilms degraded by CTAB was dominated by the species P. aeruginosa, P. saponiphila, and Acidovorax spp., as well as S. maltophilia (genera Pseudomonas and Stenotrophomonas). The SDS-degraded biofilms contained P. nitroreducens, P. knackmussi, and Diella ginsengisoli, while the DAPS-degraded biofilms contained Phenylobacterium sp. and P. sichuanensis (Table 3).

The efficiency of removal of the cationic SF, cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC), in initial concentrations of 50 and 500 μg/L, was tested using activated sludge bacterial communities in continuous reactors. In the short term, these concentrations affected the heterotrophic growth of activated sludge, but long-term exposure to these concentrations had no effect on the growth of activated sludge. The differences in initial concentrations did not affect the removal of CPC in the reactor in the first 3 days, when more than 95% of CPC was removed. With the passage of time from 13 to 42 days, the removal of CPC from the initial concentration of 50 decreased to 89%, and in the case of CPC with a higher initial concentration, the removal was reduced by 66%. Thus, the reactor removed more than 60% of the SF at the tested concentrations by adsorption and biodegradation. Two bacterial genera (Rhodobacter and Asticcacaulis) were identified as potentially important in the biodegradation of high concentrations of CPC [93].

Paun et al. [94] conducted an experiment in which they examined the efficiency of a microbial community isolated from activated sludge in the degradation of anionic (SDS) and cationic (dodecyl benzyl dimethyl ammonium chloride) SFs in glass reactors (1.5 L), under aerobic conditions, for a period of 5 days. SFs were tested in different concentrations: anionic in concentrations of 10 mg/L and 25 mg/L and cationic in concentrations of 5 mg/L and 10 mg/L. In the first 30 min of incubation, 22% of the anionic SFs were degraded, and already after 48 h, the degradation efficiency was 100%, regardless of the initial concentration. The efficiency of the biodegradation of cationic SFs in the first 30 min depended on the initial concentration, so that during that time, 40% of the SF with a higher concentration was degraded compared to 16% of the SF with a lower concentration. However, with the length of incubation, biodegradation had the same tendency as in the case of SDS, regardless of concentration. Analysis of the microbial community showed that the main role in the degradation of anionic and cationic SFs was played by coliform bacteria and their subgroups E. coli and fecal coliform bacteria (Table 3).

Generally, Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs) have good performance and are a good alternative to CAS. The quality of MBR wastewater remains more consistent and less dependent on influent variations compared to CAS. MBRs can operate at higher volumetric loading rates and require less space, which leads to shorter HRTs and ease of automation. Disadvantages are higher energy consumption due to membrane filtration, higher operating and maintenance costs, and susceptibility to membrane fouling. The use of MBRs is limited to SFs that cannot be successfully removed by CAS. An MBBR is less efficient at removing specific contaminants such as SFs compared to an MBR. This type of reactor has a larger volume and is bulkier than an MBR. The advantages of using an MBBR are lower capital and operating costs, easier operation, and less susceptibility to sudden changes in load. The disadvantages are lower performance in removing specific contaminants such as some surfactants compared to an MBR. AnMBRs can be very efficient at removing SFs and COD (e.g., COD removal 90–97%), as well as for biogas generation, but may require additional steps for nutrient removal. The advantages of AnMBRs are excellent efficiency for treating wastewater containing high concentrations of organic matter and energy recovery in the form of biogas. Disadvantages of applying AnMBRs are the possible requirements for post-processing to meet strict nutrient restrictions.

2.1.5. Microbial Fuel Cell in Bioremediation of SFs

Membrane filtration is an effective procedure for removing SFs, but it is economically unprofitable, requires a lot of energy, and emits CO2. MFCs, on the other hand, generate energy and represent an environmentally significant method for removing SFs. MFCs use oxidation mechanisms enabled by microorganisms to transform chemical energy into electrical energy. Several SF bioremediation investigations utilized an MFC-based technique. By reviewing the literature, one can find works that clearly confirm the effectiveness of bio-electrochemical systems in the purification of wastewater with SFs at concentrations of 10–120 mg/L. The removal efficiency depends on the chemical structure of the SF, the exposure time, the composition of the microbial community, the internal resistance, and the distance between the anode and the cathode. The average efficiency of removing SFs is about 90%, and the time period is 12–96 h [96].

One possible solution for the removal of SFs from wastewater is a hybrid treatment system consisting of a rising MFC with titanium dioxide (TiO2) as a photocathodic catalyst. Sathe et al. [97] tested this model for wastewater treatment with SDS at a concentration of 10 mg/L. This system is based on passing the effluent from the anode chamber of the MFC through a filter made of raw laterite soil and then through a photocathode chamber with a TiO2-coated cathode, irradiated with the UV spectrum and operated under different HRTs in the anode chamber of the MFC. Under these conditions, a high SDS removal rate of over 96% was achieved, while organic matter was removed at a slightly lower percentage (more than 71%). The MFC with a TiO2-coated cathode successfully generated a maximum power density of 0.73 W/m3 and 0.46 W/m3 at an HRT of 12 h and 8 h, respectively, demonstrating the negative effect of an increased SDS charging rate on the electrical performance of the MFC [97].

Chakraborty et al. [98] investigated the removal of SDS from wastewater using MFCs and the composition of the anode biofilm compared to the control (MFC without SDS) as well as the effects of MFCs on energy generation and organic matter removal. Septic tank sludge, which was collected from a residential area on the campus of IIT Kharagpur, was used to inoculate the anode chamber. Synthetic wastewater, which had a COD of 230 mg/L and was supplemented with L-cysteine as a carbon source, was used to feed the MFC. Then, one of the MFCs (MFC-SDS) was subjected to different concentrations of SDS of 10, 20, 30, and 40 mg/L in four operational phases (P1, P2, P3, and P4), respectively. The resulting inlet COD concentration, taking into account the COD contribution from SDS, was analyzed to be 240 ± 7 mg/L, 256 ± 13 mg/L, 270 ± 7 mg/L, and 291 ± 11 mg/L for the operational phases P1, P2, P3, and P4, respectively. The second MFC (MFC-X) was fed with synthetic wastewater of similar composition (COD of 228 ± 22 mg/L) without the addition of SDS and served as a control to determine the toxic effect of increasing the SDS loading rate. The dominant species were Acinetobacter sp. (12.7%) as well as Pseudomonas sp. (2.96%), Citrobacter sp. (4.23%), and Treponema sp. (4.0%), and others were confirmed by NGS analysis in the anode biofilm of MFC-SDS. Their active action on SDS removed about 70% of SDS, even at higher SDS concentrations of 40 mg/L, within 12 h. The anodic removal of SDS in the MFC operating mode was shown to be far superior to the anaerobic degradation that occurred during open-loop MFC operation and had lower operating costs than aerobic processes, which are energy intensive. The energy performance of the MFC-SDS compared to the control MFC was reduced by 66%, as a result of the inhibitory effect of SDS on the cell membrane and on biofilm growth. However, despite the biofilm inhibition and the preferential selection of L-cysteine over SDS, consistent SDS removal of 70% and above was achieved [98].

A recent article [47] examined the anaerobic breakdown of LAS by a microbial biofilm utilizing a single-chamber MFC, the capacity for bioelectricity generation, and cellular manipulation, with the objective of creating a biosensor. This sensor functions not only in the quantitative assessment of LAS concentration in wastewater but also as an energy generator and purifier. The generated MFC was supplied with LAS at a concentration of 60 mg/L until a viable biofilm formed. It was formed after 34 days, and then the maximum values of open-circuit potential (425 mV), power density, and current density (75 mV/m3 and 663 mA/m3, respectively) were recorded. The internal resistance of the MFC-based biosensor was about 1 kΩ. The clearance of LAS increased over time, and by 96 h, about 90% of the LAS had been eliminated with a Coulomb efficiency of approximately 65%. At concentrations of 10–120 mg/L, the relationship between the SF and current density was linear. The mentioned authors used a modeling package as an auxiliary tool to understand the cell electrical output signal and track the biochemical processes during anaerobic degradation of LAS. They demonstrated competition between electrogenes and methanogens in biofilms as well as the effect of external resistance on electrogene conditions [47].

The presented results indicate that MFCs’ efficiency is restricted by high concentrations of SFs and their harmful byproducts, which hinder the growth of microorganisms; hence, this technology cannot totally eliminate SFs. To increase the efficiency of SF removal, hybrid systems or post-treatment for complete purification are required.

2.2. Heavy Metals

HMs are inorganic, non-biodegradable chemical elements that dissolve well in water and can form stable compounds, which circulate in the aquatic environment and can accumulate over time. The basic chemical properties of HMs are a relatively high molecular weight and density (>4 g/cm3), which is up to 5-fold higher than water. They are an integral part of the environment, including soil, rocks, and water. They enter the environment from various sources: mining, industrial wastewater, urban sewage, traffic, etc. [99]. Some of the HMs, including Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn, are necessary for biological processes in trace amounts and are therefore called essential. For example, Fe plays a key role in the respiratory system as part of the heme protein. Similarly, Cu, as part of hemocyanin, plays a role in the transport of electrons and O2 in some invertebrates (mollusks and arthropods). Mn is a cofactor of multiple enzymes and regulates metabolism and digestion and protects antioxidant and neuronal health in the human body. In plants, Mn is involved in photosynthesis, respiration, protection against free radicals, pathogens, and hormone signaling. Despite their important biological functions, these metals can be toxic if present in concentrations above the permissible limit. Among the non-essential HMs that cause toxicity are Cd, Pb, Hg, and the metalloid As. They have a toxic effect on all living beings, from microorganisms to humans, even at low concentrations. If they enter the human body, HMs can poison various organs, including the brain, heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, etc. The main problem is that they cannot be degraded but accumulate and represent very persistent pollutants that have harmful effects on living organisms and ecosystems [3].

In this paper, the focus of interest is on HMs present in graywater and household wastewater. In laundry wastewater (also known as graywater), HMs originating from detergents used for washing and cleaning have been detected, complicating the WWT process. The most commonly identified HMs in the above-mentioned wastewaters are copper, manganese, zinc, cadmium, lead, nickel, and mercury. In household wastewater, the most commonly identified HMs are Zn, Pb, Hg, Cu, and Ni, which mainly originate from detergents for washing dishes and cleaning kitchen surfaces and bathrooms, for washing laundry and dishes, as well as for maintaining personal hygiene. In order to eliminate the harmful impact of HMs on human health and the environment, numerous studies are devoted to the development of new advanced technologies for the efficient purification of wastewater [100]. Indigenous microorganisms living in places polluted by HMs have developed several protective mechanisms over time as an adaptive response to stressful living conditions. These are mechanisms of HM chelation, biotransformation, and metal excretion from cells. Since microorganisms live in communities and form biofilms composed of EPSs, these structures can absorb, trap, or immobilize HMs in the environment.

It has been shown that one of the effective mechanisms for removing HMs from aqueous solutions is biosorption, which includes various microorganisms (bacteria, yeasts, fungi, and algae). This modern, economically profitable, and environmentally acceptable biotechnological process can also remove very dangerous HMs such as cadmium, mercury, lead, chromium, and arsenic [3]. Many indigenous microorganisms show resistance to a large number of HMs, and their identification is extremely important for their practical application in bioremediation. Species that have developed resistance to a greater number of HMs are particularly significant, as is the case with the recently discovered bacterial strain Bacillus tropicus MCCC 1A01406, which is resistant to as many as eight heavy metals, including lead, chromium, cadmium, copper, iron, zinc, nickel, and cobalt [101].

To date, various studies have investigated the potential of indigenous single and combined cultures of microorganisms, either in planktonic or biofilm form, for the removal of HMs. The results showed that in general, communities of microorganisms are more effective than single species [11,12,13] and that the biofilm form has a superior ability to remove HMs [11,12,13,14]. In this paper, individual and combined cultures of bacteria are shown that are most effective in removing HMs from wastewater with detergents, which could be potentially applied in wastewater treatment.

2.2.1. Single-Species Bacterial Biofilms in Removal of HMs

A review of the literature has shown that biofilms of individual bacterial species exhibit selective capacity for HM removal, depending on the type of bacteria, the type of metal, and its concentration (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bacterial isolate’s ability for HM removal.

A biofilm is a complex community of microorganisms that is held together by cells secreting mucus or an extracellular polymer substrate that serves as a matrix and connective tissue. The biofilm matrix is made up of biopolymers and may contain exopolysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (or eDNA). This matrix acts as a physical barrier that protects microorganisms within the biofilm from stressful external factors (antibiotics, toxins, UV radiation, etc.). Additionally, it participates in the adsorption and transport of pollutants, enabling close contact with cells and facilitating their decomposition, as well as in the hydration and concentration of nutrients, which is manifested by an increase in metabolic activity. Quorum sensing enables mutual communication among biofilm members using signal molecules, coordinating gene expression and metabolic processes. The result of this coordination is the optimal effect of the microbial community within the biofilm in the breakdown of pollutants and detoxification related to individual cells.

Bacteria resistant to HMs have developed different mechanisms for the detoxification of HMs and their accumulation in cells, including bioaccumulation, biosorption, and biotransformation. These mechanisms are based on various processes: intracellular uptake of HMs and their binding to proteins or siderophores, compartmentalization of HMs within vacuoles, bioprecipitation, reduction, extracellular chelation, ion-exchange interactions with extracellular polymeric substances, and methylation of HMs into gaseous form [126]. Some of these HM bioremediation mechanisms are shown in Figure 2.

Table 4 presents the species with high HM removal capacities. As many as six bacterial species remove Cu with an efficiency of over 90% [102,103,104]. The most efficient were Vitreoscilla sp. ENSG301 (97.1%) and B. thuringiensis ENSW401 (96.8%), while Bacillus sp. was the least efficient (75.75%). In the removal of Pb, 11 species were identified, of which 5 species removed Pb with an efficiency of over 90%: Klebsiella sp. USL2D, Oceanobacillus profundus, Vitreoscilla sp. ENSG301, B. thuringiensis ENSW401, and E. cloacae [103,104,105,109,110,111,112]. Eight species have a high ability to remove Mn, of which three plants remove over 90% (Ochrobactrum sp. NDMn-6, then Pseudomonas sagittaria MOB-181 and Brevibacillus parabrevis MO2) [119,120,121,122]. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans was 100% effective in removing Zn [106]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa FZ-2, at 99.7%, was the most effective in removing Hg species, while the other species, including Enterobacter cloacae, Bacillus thuringiensis, and Vibrio fluvialis, were less effective [113,114,115,116]. In the removal of Cd, Pseudomonas azotoformans JAW1 [122] and Pseudoalteromonas sp. SCSE709-6 [124], with over 90% efficiencies, and Vitreoscilla sp. ENSG301, at 94.2% stand out in Ni removal [103].

A study conducted by [103] investigated the biosorption capacity of biofilm-forming isolates (from wastewaters of Bangladesh): Enterobacter asburiae ENSD102, Enterobacter ludwigii ENSH201, Vitreoscilla sp. ENSG301, Acinetobacter lwoffii ENSG302, and Bacillus thuringiensis ENSW401 for copper, nickel, and lead under different environmental conditions. At a concentration of 100 mg/L, the biosorption capacity for copper was as follows: Vitreoscilla sp. ENSG301 (97.1%), B. thuringiensis ENSW401 (96.8%), E. asburiae ENSD102 (92.7%), E. ludwigii ENSH201 (90.2%), and A. lwoffii ENSG302 (92.5%). At the same nickel concentration, the biosorption capacity of the isolate was Vitreoscilla sp. ENSG301 (94.2%), and similar values were shown by E. asburiae ENSD102, A. lwoffii ENSG302, and B. thuringiensis ENSW401. In the case of lead of the same concentration, the biosorption capacity was in the following range: B. thuringiensis ENSW401 (93.5%), Vitreoscilla sp. ENSG301 (91.5%), E. asburiae ENSD102 (89.8%), A. lwoffii ENSG302 (87.6%), and E. ludwigii ENSH201 (84.2%). Increasing the metal concentration to 200 mg/L decreased the biosorption efficiency: Cu (80.7 to 91.2%), Ni (69.8 to 89.6%), and Pb (78.1 to 88.5%) (Table 4).

Bacterial species that tolerate mercury and lead include Bacillus pumilus [127], E. coli [11,12], Pseudomonas sp. [128], Azotobacter sp. [129], etc. Tolerance to the presence of divalent copper and zinc is exhibited by Acinetobacter lvoffii ENSG302 [130], Acinetobacter sp. IrC1 and IrC2, Cupriavidus sp. IrC4 [131], E. coli [13], Enterobacter asburiae ENSD102, Vitreoscilla sp. ENSG301, and Halobacterium salinarum R1 [132]. Tolerance to the presence of divalent cadmium and nickel was shown by the species E. asburiae [133], E. faecium [134], and E. cloacae MC9 [135]. S. epidermidis showed excellent capacity for Pb (100%), Ni (100%), Cd (90.29%), Zn (84.95%), and Fe (54.82%) removal.

Enterobacter kobei FACU6 showed tolerance to 3000 mg/L of lead and expressed pronounced efficiency for its removal (83.4%) at a concentration of 571.9 mg/g [136]. Pseudoxanthomonas mexicana GTZY demonstrated tolerance to mercury and expressed transforming ability at a level of 84.3% [137]. Recently, it was discovered that bacterial isolates of Pseudomonas alloputida and Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus, originating from the Himalayas, showed remarkable success in removing divalent copper (over 50%) and that non-living bacterial cells showed a better absorption capacity than living cells [138]. The authors of this study highlighted the possibility of applying a passive bioremediation strategy to remove copper from wastewater. The same phenomenon was early observed in a biosorption study using Bacillus salmalaya strain 1369SI for chromium (VI) removal from water solution, since the bacterial dead biomass expressed about 57% better adsorption capacity than living cells [139].

A study by [140] revealed that the planktonic form of Klebsiella oxytoca had a high degree of resistance to mercury, but the biofilm of K. oxytoca was tenfold more resistant. The biofilm of Enterobacter cloacae has an exceptional ability to remove mercury (97.81% over 10 days). The study of [141] presented the results of the efficiency of planktonic cells and biofilms of Pseudomonas chengduensis PPSS-4 (an isolate from a sediment sample, India), a multi-metal resistant strain, to remove Pb, Cr, and Cd under different environmental conditions. The isolate showed tolerance to high metal concentrations—2200 mg/L Pb(II), 1900 mg/L Cr(VI), and 1200 mg/L Cd(II)—and higher absorption efficiency in the form of biofilm than in the form of planktonic cells, both in solutions with individual metals and in solutions with a mixture of metals. Under optimal conditions, bacterial biomass removed Cd in the highest percentage (52.63%) and, at a lower percentage, Cr (28.23%) and Pb (12.53%).

The efficiency of removing metals from solutions containing a mixture of metals has been investigated in various studies. Recently, a multi-metal resistant strain, Bacillus sp. GH-s29, was discovered that developed biofilm in the presence of arsenic, cadmium, and chromium and removed them from solutions with single and mixed HMs. The strain showed maximum removal of As(V), Cd(II), and Cr(VI) from solutions with single metals at the percentages 73.65%, 57.37%, and 61.62% respectively, while it showed lower efficiency in removing the mentioned metals in solutions with mixed metals: 48.92%, 28.7%, and 35.46%, respectively [142]. Biofilm of Virgibacillus halodenitrificans Z4D1 possessed the capacity to immobilize the HMs Cd2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ from contaminated soils and wastewater and influenced the biomineralization processes [143]. A study [144] confirmed the ability of Bacillus zhejiangensis CEIB S4-3 to remove high amounts of Pb2+ (91%) and Cd2+ (90%) at an initial concentration of 50 mg/L. In the case of the HM mixture (Cd–Pb), the efficiency of removal was lower (Pb (75%) and Cd (59%)), as well as using a different mechanism of removal (Cd was primarily removed via extracellular biosorption and Pb via intracellular bioaccumulation). Villegas et al. [145] identified eight biofilm-forming bacterial isolates (obtained from excavated soil in Mogpog, Marinduque) that were tolerant to the following HMs: Cu, Pb, Zn, and Cd. Of all the isolates, Rhodococcus equi NV1A showed the highest degree of tolerance to the mentioned metals. All isolates exhibited the ability to remove copper in a solution at a concentration of 100 mg/L (single-metallic solution), with varying degrees of efficiency (15–68%) after six hours. When copper was present in the metal mixture, isolates Bacillus sp. NV17 and Bacillus megaterium R11 removed a larger amount of copper (79.20% and 57.40%, respectively), while Enterococcus faecium NV211 maintained the same efficiency (16.40%) as in the case of the single-metallic solution. Bacillus megaterium R11 removed Pb, Zn, and Cd in a metal mixture solution with efficiencies of 90.60%, 84.60%, and 82.72%. Bacillus sp. NV17 was highly efficient in the removing of Pb (96.60%), Zn (90.80%), and Cd (78.33%). Rhodococcus equi NV1A expressed excellent removal ability for Pb (96.60%), Cd (90.83%), and Zn (89.90%).

Heidari et al. [146] investigated the bioremediation capacity of Sphingomonas melonis and Enterobacter hormaechei for the removal of metals (Pb, Cd, Cu, and Ni) from a solution with a mixture of metals (50 mg/L of each metal). This study showed that S. melonis and E. hormaechei removed significant quantities of Cd (96 and 87%, respectively) from a solution with a mixture of metals.

2.2.2. Multispecies Bacterial Biofilms in Removal of HMs

Biofilms are often composed of diverse microbial communities that act synergistically to degrade a wide range of contaminants, increasing the resilience of the system and better adapting to changing environmental conditions. The complex architecture of biofilms can provide a large surface area for contaminant adsorption, increasing the efficiency of the bioremediation process. The structure of the biofilm creates a stable and controlled microenvironment that supports robust microbial activity and survival. The main factors that favor a consortium over individual species are the variability of metabolic pathways and protective mechanisms and the ability to simultaneously remove different HMs. The advantages of biofilms compared to planktonic cells are shown in Figure 3. Numerous studies confirmed that consortium biofilms are generally more tolerant and efficient in removing HMs than single-species biofilms [7,8]. Examples of biofilms of a consortium of natural isolates from wastewater that successfully remove HMs such as lead, mercury, zinc, copper, cadmium, and nickel have been documented in scientific papers. The biofilm of a two-species microbial community, E. coli LM1 and R. mucilaginosa, was four times more resistant to lead than biofilms of individual species [11]. Biofilms of three-species consortia were the most effective in removing mercury [7]. A biofilm composed of bacteria and fungi had a higher capacity for removing hexavalent chromium, which removed 90% of the chromium in 10 days [147]. Literature data on the efficiency of the bacterial consortium in the removal of HMs showed that a co-culture composed of Acinetobacter sp. and Arthrobacter sp. can remove 78% of Cr, whereas a co-culture of P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis removes as much as 99.6% of Cr [148]. A mixed bacterial community composed of indigenous species, Aeromonas caviae, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Shewanella putrefaciens, showed better resistance and removal capacity for Zn (61.93%), Ni (61.49%), and Cu (47.02%) than its monocultures [149].

A bacterial consortium composed of Proteobacteria (50.8%), Bacteroidetes (18.9%), Ascomycota (60.8%), and Ciliophora (12.6%) displayed 94–100% efficiency for Cd and Pb sequestration and 70% efficiency for Ni and As sequestration [150]. A bacterial community (Viridibacillus arenosi B-21, Sporosarcina soli B-22, Enterobacter cloacae KJ-46, and E. cloacae KJ-47) displayed good ability in the immobilization of Pb (98.3%) and Cd (85.4%) [151]. A consortium of four bacteria (Staphylococcus epidermidis, Serratia marcescens, Proteus mirabilis, and Escherichia coli) had the capacity to completely remove Pb, Cd, Zn, and Ni [152].

Three-membered consortium biofilms have been shown to be effective in removing mercury (96.64% to 99.03% over 10 days). The biosorption study in [8] observed which species among several indigenous species (isolated from the Central Effluent Treatment Plant’s wastewater) possess the best ability of biosorption for some HMs (zinc, copper, lead, nickel, and cadmium). The species involved in this study were E. cloacae, K. oxytoca, Serratia odorifera, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The consortia composed of K. oxytoca/S. odorifera/S. cerevisiae and E. cloacae/K. oxytoca/S. odorifera were almost absolutely efficient in removing Cu (99.18% by KSC), Pd, and Ni (99.14% and 99.03%, respectively, by EKS). Individual biofilms of K. oxytoca and E. cloacae were more efficient than the combined cultures in removing Ni (98.47%) and Zn (98.06%), respectively.

2.2.3. Removal of HMs in Bioreactors

To date, several studies have been performed in order to evaluate the efficiency of bacterial biofilms in HM removal in different types of bioreactors under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Table 5).

Table 5.

Efficiencies of individual and bacterial community biofilms for HM removal in different bioreactor types.

To increase the efficacy of HM removal and the duration of biofilm activity, the influence of various materials on which biofilms are typically deposited was researched. Kiran et al. [153] investigated the possibility of removing HMs in the presence of Desulfovibrio sp. (sulfate-reducing bacteria, SRB) immobilized on sodium alginate in a bioreactor with batch and continuous operation. In a batch bioreactor, more than 95% of the HMs were removed, with an HRT of 48 h. Optimal HM loading rates of up to 2.20 mg/L∙h for Fe(III), Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Ni(II) and up to 4.29 mg/L∙h for Cu(II) resulted in maximal HM removal from the mixture in a continuous downstream flow reactor filled with immobilized SRB beads: Cu(II) = 99% and Zn(II) = 95.8%. These results indicate good adsorption properties of sodium alginate, which leads to efficient HM removal. In the study by [154], the efficiency of removing various HM ions (Cd(II), Fe(III), Cu(II), Mn(II), Co(II), Zn(II), Ni(II) and Pb(II)) was tested using a natural isolate of P. aeruginosa (Lake Maryut, Egypt) in a specially constructed fixed-bed glass bioreactor filled with a solid support (luffa pulp). The reactor was operated under optimal conditions of pH (7.5) and bacterial biomass (750 mg/L) and was tested on 13 wastewater samples containing the aforementioned metals. The results showed 100% efficiency of the bioreactor in removing Cu(II), Zn(II), and Cd(II) and lower percentage of removal for Pb(II) and Fe(III) (47% and 62%), respectively, over a period of 24 h. Recently, a study [159] evaluated the feasibility of removing Ni(II) from real industrial wastewater using a rising anaerobic bioreactor with zeolite in the presence of a heterotrophic consortium. The dominant bacterial genera were Kosmotogae, followed by Firmicutes, Ruminococcus, and Clostridium. Fervidobacterium and Geobacter genera were not detected at the end of the bioreactor, which implies their role in the initial anaerobic treatment of nickel removal. At the tested nickel concentrations of 250–500 ppm, an exceptional nickel removal efficiency (99%) was reached. This study showed that the use of zeolite affects the remarkable efficiency of nickel removal.

Extremophilic bacteria’s potential for bioremediation of HMs has recently received more attention. The efficiency of sulfate and iron removal from saline wastewater was investigated in the presence of halophilic SRB (Desulfovibrio halophilus) in a fluidized bed reactor under anaerobic conditions [157]. The wastewater contained Fe in the concentration range of 50–400 ppm. The removal efficiency of sulfate (78.4%) and iron (85.3%) was maximal after 24 h. Under optimal conditions, maximum H2S production (228 mL/L) was achieved. By using the anaerobic bioreactor defined in this way, significant amounts of sulfate and iron in wastewater were reduced. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that using extremophilic bacteria provides a novel strategy to HM bioremediation. The removal of elemental mercury and nitrogen monoxide was investigated in the presence of a thermophilic microbial community and a membrane biofilm reactor (TMBR) [158]. The bacterial population consisted of mercury-resistant species: Comamonas, Pseudomonas, Desulfomicrobium, Burkholderia, and Halomonas. The following nitrifying/denitrifying bacterial genera were identified: Brucella, Paracoccus, Tepidiphilus, Proteobacteria, Pseudomonas, and Symbiobacterium. The bioreactor was supplied with 6% oxygen and operated at a temperature of 60 °C for 210 days. Under these conditions, the microbial population removed 88.9% Hg0 and 85.3% NO. Analysis of the biofilm determined the presence of divalent mercury (Hg(II)). This investigation discovered that thermophilic microorganisms/communities had advantageous properties for mercury removal.

Giordani et al. [155] evaluated the efficiency of the microbial community in an anaerobic sequential reactor (ASBR) in the treatment of mine drainage water with synthetic acid. The reactor was operated in six phases: phases 1 and 2 included treatment at low pH, phases 3–5 included treatment after addition of metals (Fe(II), Zn(II), and Cu(II)), and in phase 6, treatment was carried out under conditions of increasing sulfate concentration (from 500 to 1500 mg/L) and in the absence of nutrients. Using genetic and molecular analyses, it was determined that after the addition of HMs, the structure of the microbial population retained 62% similarity to the initial inoculum and 87% similarity after a change in pH value (from 5 to 4). The dominant species in the reactor were Syntrophobacter (SRB) and Methanosaeta (acetoclastic methanogen, AM). Metal-reducing species (MRSs) that dominated in phases 5 and 6 were Geobacter, Anaerolinea, and Longilinea spp. The relative representation of SRB, AM, and MRSs in percentages in the fifth and sixth phases was 8:8:11 and 7:14:15, respectively. The ASBR offers various advantages, including easy and simple handling, effective operation control, long solid retention duration, and preservation of the microbiome.

Chen et al. [160] executed a pilot study analyzing the microbial community composition of the efficacy of its in situ application for acid mine drainage (AMD) treatment and discovered that the microbial community composition was influenced by pH, total sulfur, and iron content. The most abundant species involved in Fe removal were Ferrovum, Delftia, Acinetobacter, Metallibacterium, Acidibacter, and Acidiphilium. The results of this study showed that this method can remove the highest amount of 93.7% of total soluble Fe and 99% of soluble Fe(II).

Nogueira et al. [163] studied the efficiency of SRB in a down-flow structured bed bioreactor (DFSBR) for the treatment of mine drainage water with synthetic acid (AMD) with the aim of reducing sulfate, increasing pH, and precipitating metals in solution (Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, and Zn). Vinasse acted as an electron donor for SRBE. It was found that Geobacter and Desulfovibrio played a leading role in sulfate and metal reduction, while Parabacteroides and Sulfurovum served for fermentation. This type of reactor reduced the quantities of sulfates (55 and 91%) and HMs in wastewater (60–80%). It had the highest efficiency in the removal of Co, Ni, and Zn (80%), followed by the removal of Cu (73%), Fe (70%), and Mn (60%). The main mechanism for HM removal is based on the precipitation of metal sulfides.

HMs and nitrogen are present in coke oven wastewater. Research [161] showed that the presence of Pseudogulbenkiania sp. NH8B, a nitrate-dependent iron-oxidizing species, can simultaneously remove nitrate, Fe, and Zn in a continuous flow reactor containing 10 mM nitrate, 5 mM Fe(II), 4 mM acetate, and 10 mg/L Zn dissolved in basal medium. However, the efficiency of the bioreactor was slightly lower when it was fed with coke oven wastewater with 10 mM nitrate, 5 mM Fe(II), 4 mM acetate, and 10 mg/L ZnCl2. As a possible cause, the authors cited inhibition of bacterial growth by thiocyanate or some organic pollutants present in wastewater. As a possible solution to this problem, the authors suggest the use of a mixed community of NDFOs and denitrifiers that would degrade the mentioned inhibitors.

The potential for removing a mixture of HMs from mine wastewater was tested using a sulfate reduction bioreactor inoculated with a sulfide microbial community [162]. The reactor was operated continuously for 172 days, containing ethanol added as an electron donor and a tailings leachate solution. The addition of leachate resulted in more efficient sulfate removal (84.7%), oxygen consumption, and an increase in pH value. These conditions were conducive to 100% metal removal with the exception of Mn (80%), Ca (50%), and Mg (38%). The composition of the bacterial community changed from the moment of inoculation, and eventually SRB, especially Desulfovibrionaceae, dominated. In addition, the addition of tailings leachate led to the adaptation of methanogens.

Another type of reactor that has been shown to be effective in the removal of HMs (Cu and Cd) from wastewater is the periphytic biofilm reactor (PBfR) [156]. By mathematically modeling the results of kinetic studies, a new three-stage PBF model was constructed to simulate the kinetics of Cu and Cd removal from wastewater. The results confirmed the high removal efficiency of Cu (99%) and Cd (99.7%) in PBfR. The authors of this study pointed out that the eukaryotic organism had a key role in HM removal, while the prokaryote had a negative effect on metal removal, with the possibility of independent adaptation of the microbial communities in PBfR to the toxic effects of metals. This study provides insight into an innovative approach to the treatment of wastewater with Cu and Cd, with a high efficiency of their removal.

Despite their great efficiency for continuous treatment of huge quantities of wastewater and potential for HM recovery, bioreactors have certain disadvantages, including biomass leaching, liquid–solid separation issues, and membrane fouling in particular systems.

2.2.4. Microbial Fuel Cells in HM Removal

One of the attractive techniques for bioremediation of wastewater containing lower metal concentrations with energy production is MFCs.

Miran et al. [164] conducted a study in which they examined the effect of different Cu(II) concentrations on the performance of a two-chamber MFC in which the anode was cultivated with SRB, among which the biofilm of the genus Desulfovibrio (38.1%) dominated. They found that Cu(II) concentrations up to 20 mg/L stimulated the metabolic reactions of SRB. SRB produces sulfide that reacts with Cu(II) and precipitates it in the form of metal sulfide. The MFC maintained good performance after 20 cycles. More than 98% of Cu(II) was removed in the anode chamber, and an electrical power of 224.1 mW/m2 was generated.