Anxiety, Academic Performance, and Physical Activity in University Students: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Question

- What is the nature and extent of evidence regarding the triadic relationship between PA, anxiety, and academic performance in university students?

- What are the key characteristics (e.g., type, frequency, intensity, duration) of PA interventions or activities evaluated in these studies?

- What reported associations exist between PA and anxiety levels in university students?

- What reported associations exist between PA and academic performance outcomes in university students?

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.2.1. Search Strategy

2.2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria

- Population: The target population consists exclusively of university students (both undergraduate and graduate levels). This population was selected due to its well-documented vulnerability to psychological stress, anxiety disorders, and sedentary behaviors (Eisenberg et al., 2007; Ozen et al., 2010), along with the significant implications of these factors for academic functioning and success in higher education environments.

- Concept: Our central focus examines relationships between PA (including exercise and sport participation) and both anxiety levels and academic performance outcomes. The review considered various PA modalities, including aerobic exercise, resistance training, structured sport participation, and recreational physical activities, provided they reported measurable outcomes related to either anxiety (using validated instruments) or academic achievement (e.g., GPA, exam scores). This focus reflects growing evidence suggesting PA may serve as both a protective factor against anxiety/academic stress and a potential enhancer of cognitive performance (Rodriguez-Ayllon et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2023).

- Context: We included studies conducted in any university or college setting without restrictions based on academic discipline or geographical location. The review incorporated studies published in either English or Spanish to allow for broader cultural representation while maintaining practical limitations. This intentionally broad contextual scope facilitated identification of potential cross-cultural patterns and research gaps in the literature.

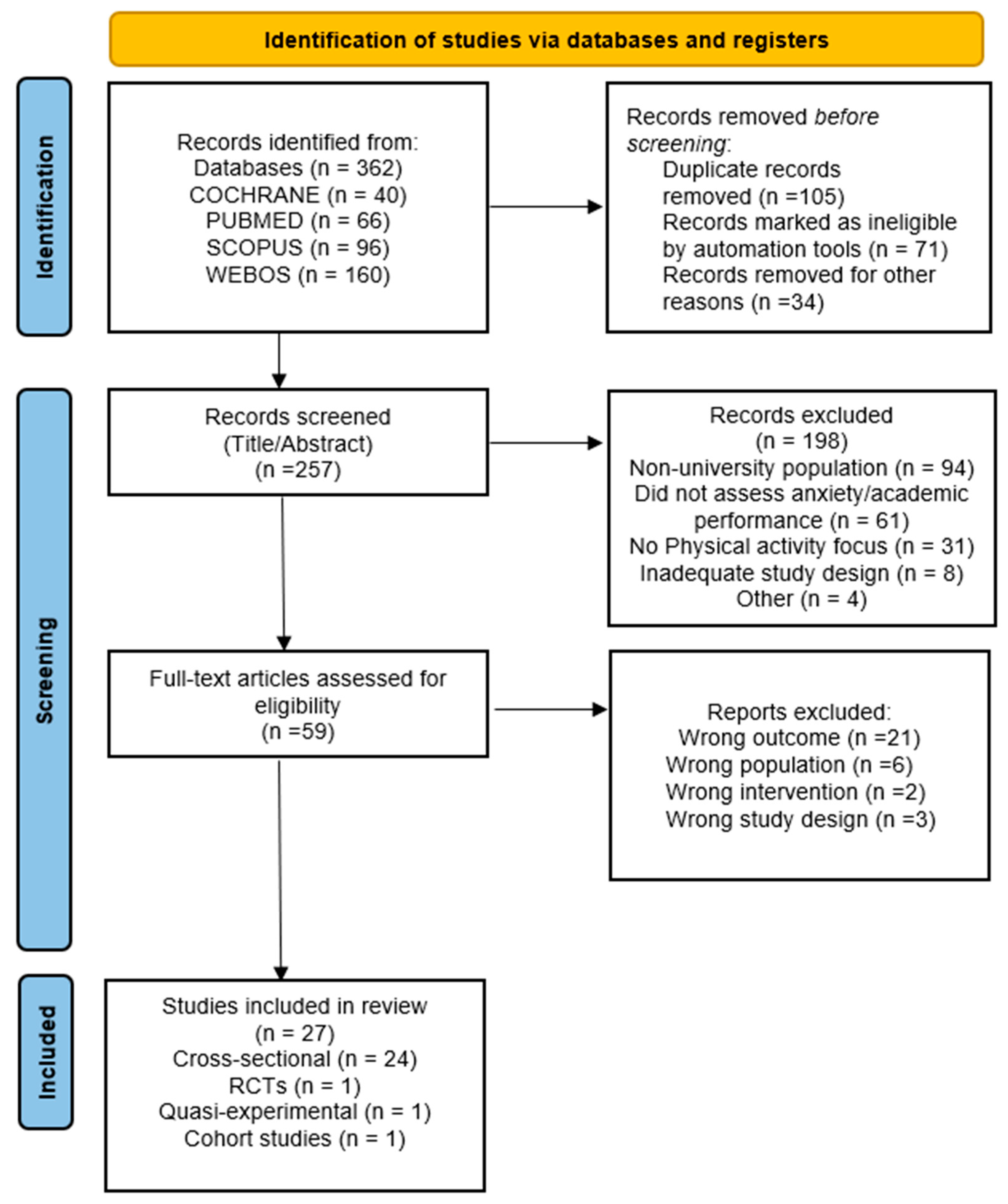

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.5. Consideration of Heterogeneity and Moderators

2.6. Critical Evaluation of Individual Sources of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

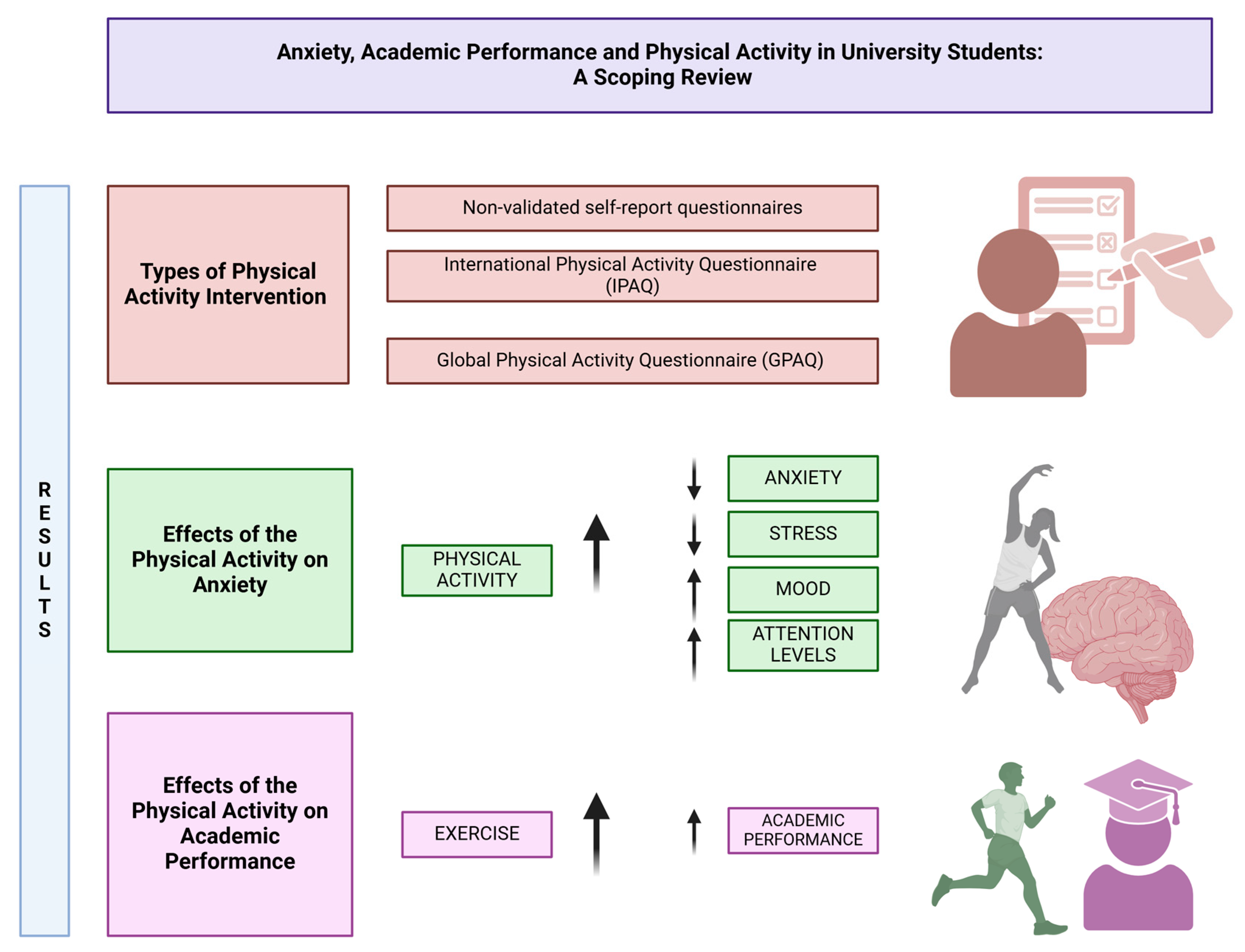

3.2. Primary Results: Types of Physical Activity Interventions

3.3. Secondary Results: Effects of Physical Activity on Anxiety

3.4. Additional Analyses: Effects of Physical Activity on Academic Performance

3.5. Relationship Between Anxiety and Academic Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Characteristics and Methodological Considerations

4.2. Theoretical Interpretation of Findings

4.3. Impact of Physical Activity on Anxiety

4.4. Impact of Physical Activity on Academic Performance

4.5. Interactions Between Anxiety and Academic Performance

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

4.7. Practice, Research, and Policy Implications

4.7.1. Practice Implications

4.7.2. Research Implications

4.7.3. Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical Activity |

| AP | Academic Performance |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| SADS | Social Avoidance and Distress Scale |

| WTAI | Westside Test Anxiety Inventory |

| MLSQ-SF | Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (Short Form) |

| SISCO | SISCO Academic Stress Inventory |

| EVEA | Escala de Valoración del Estado de Ánimo |

| SAS | Self-rating Anxiety Scale |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) |

| PEP | Perceived Educational Progress |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| GPA | Grade Point Average |

References

- Abbasi, G. A., Jagaveeran, M., Goh, Y.-N., & Tariq, B. (2021). The impact of type of content use on smartphone addiction and academic performance: Physical activity as moderator. Technology In Society, 64, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaaddin, R. N., Ibrahim, N. K., & Kadi, M. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety and stress among pharmacy students from Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabi. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International, 33(57B), 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnofaiey, Y. H., Atallah, H. M., Alrawqi, M. K., Alghamdi, H., Almalki, M. G., Almaleky, J. S., & Almalki, K. F. (2023). Correlation of physical activity to mental health state and grade point average among medical students in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Cureus, 15(6), e40253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariani, D. W. (2017). Relationship model of personality, motivation, and student engagement. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(6), 832–849. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Velasco, A. I., Donoso-González, M., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2021). Analysis of perceptual, psychological, and behavioral factors that affect the academic performance of education university students. Physiology Behavior, 238, 113497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Sánchez, M. J., Ubago-Jiménez, J. L., Melguizo-Ibáñez, E., & Alonso-Vargas, J. M. (2024). Influencia de la actividad física y la dieta en el estrés y la ansiedad de la enseñanza superior. SPORT TK-Revista EuroAmericana de Ciencias Del Deporte, 3(3), 3. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=10020520 (accessed on 7 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Binning, K. R., Cook, J. E., Greenaway, V. P., Garcia, J., Apfel, N., Sherman, D. K., & Cohen, G. L. (2021). Securing self-integrity over time: Self-affirmation disrupts a negative cycle between psychological threat and academic performance. Journal of Social Issues, 77(3), 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambila-Tapia, A. J. L., Miranda-Lavastida, A. J., Vázquez-Sánchez, N. A., Franco-López, N. L., Pérez-González, M. C., Nava-Bustos, G., Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, F. J., & Mora-Moreno, F. F. (2022). Association of health and psychological factors with academic achievement and non-verbal intelligence in university students with low academic performance: The influence of sex. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Villa, M. A., Díaz-Marín, I. J., Paredes Prada, E. T., De la Rosa, A., & Niño-Cruz, G. I. (2023). Cross-sectional analysis of Colombian University students’ perceptions of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Repercussions on academic achievement. Healthcare, 11(14), 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon-Cuberos, R., Zurita-Ortega, F., Maria Olmedo-Moreno, E., & Castro-Sanchez, M. (2019). Relationship between academic stress, physical activity and diet in university students of education. Behavioral Sciences, 9(6), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapell, M. S., Benjamin Blanding, Z., Takahashi, M., Silverstein, M. E., Newman, B., Gubi, A., & McCann, N. (2005). Test anxiety and academic performance in undergraduate and graduate students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, E., Al Ghadeer, H., Mitsu, R., Almutary, N., & Alenezi, B. (2016). Relationship between test anxiety and academic achievement among undergraduate nursing students. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(2), 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Deisz, M., Papproth, C., Ambler, E., Glick, M., & Eno, C. (2024). Correlates and barriers of exercise, stress, and wellness in medical students. Medical Science Educator, 34(6), 1433–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, N., Chetty, S., Handayani, L., Sahabudin, N. A., Ali, Z., Hamzah, N., Shamsiah, N., Rahman, A., & Kasim, S. (2019). Learning styles and teaching styles determine students’ academic performances. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 8(3), 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman, R. K., Sallis, J. F., & Orenstein, D. R. (1985). The determinants of physical activity and exercise. Public Health Reports, 100(2), 158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Dosalwar, S., Kinkar, K., Baheti, A., & Sonawani, S. (2023). The perceived impact of correlative relationship between depression, anxiety, and stress among university students. In Advanced computing (pp. 173–182). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuc, M.-M., Aubertin-Leheudre, M., & Karelis, A. D. (2020). Gender differences in academic performance of high school students: The relationship with cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle endurance, and test anxiety. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 11(1), 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran-Galdo, R., & Mamani-Urrutia, V. (2021). Eating habits, physical activity and its association with academic stress in first year health science university students. Revista Chilena De Nutricion, 48(3), 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D., Gollust, S. E., Golberstein, E., & Hefner, J. L. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(4), 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B., Griffiths, M. D., Iranmanesh, M., & Salamzadeh, Y. (2022). Associations between Instagram addiction, academic performance, social anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction among university students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(4), 2221–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallasch, D., Conlon-Leard, A., Hardy, M., Phillips, A., Van Kessel, G., & Stiller, K. (2022). Variable levels of stress and anxiety reported by physiotherapy students during clinical placements: A cohort study. Physiotherapy, 114, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosadi, I. M. (2024). Predictors of anxiety and academic burnout in Saudi undergraduates: The role of physical activity. BMC Public Health, 24, 1089. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann, A. (2012). From ritual to record: The nature of modern sports. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M. D., Gibson, A. M., Wagerman, S. A., Flores, E. D., & Kelly, L. A. (2019). The effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on state anxiety and cognitive function. Science and Sports, 34(4), 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J., Chalmers, I., Lind, J., Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., Thornton, H., Goddard, O., & Hodgkinson, M. (2011). Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine 2011 levels of evidence. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Huenergarde, A., Thompson, E., & Reyes, A. (2018). Barriers to access: Food insecurity, mental health, and academic outcomes among university students. Health Education Research, 33(5), 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S., Akter, R., Sikder, T., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). Prevalence and factors associated with depression and anxiety among first-year university students in bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(3), 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, H., Alakkari, M., Al-Mahini, M. S., Alsayid, M., & Al Jandali, O. (2022). The impact of anxiety and depression on academic performance: A cross-sectional study among medical students in Syria. Avicenna Journal of Medicine, 12(3), 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarso, M. H., Tariku, M., Mamo, A., Tsegaye, T., & Gezimu, W. (2023). Test anxiety and its determinants among health sciences students at Mattu University: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1241940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M., Hossain, A., Islam, M. A., Ahmed, M., Kabir, E., & Khan, M. N. (2024). Exploring the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among university students in Bangladesh and their determinants. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 28, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, S., Kiyani, T., Kayani, S., Tony, M., Biasutti, M., & Wang, J. (2021). Physical activity and anxiety of Chinese university students: Mediation of self-system. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayani, S., Kiyani, T., Wang, J., Sanchez, M. L. Z., Kayani, S., & Qurban, H. (2018). Physical activity and academic performance: The mediating effect of self-esteem and depression. Sustainability, 10(10), 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, S., Wang, J., Biasutti, M., Sánchez, M. L. Z., Kiyani, T., & Kayani, S. (2020). Mechanism between physical activity and academic anxiety: Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability, 12(9), 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharroubi, S. A., Al-Akl, N., Chamate, S.-J., Abou Omar, T., & Ballout, R. (2024). Assessing the relationship between physical health, mental health and students’ success among universities in Lebanon: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(5), 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobach, Y., Romero-Ramos, O., Ceballos, C. E. L., Romero-Ramos, N., Suarez, A. J. G., & Niznikowski, T. (2024). Brain breaks through dance: An experience with university students. Retos-Nuevas Tendencias En Educacion Fisica Deporte Y Recreacion, 51, 683–689. [Google Scholar]

- Lun, K. W. C., Chan, C. K., Ip, P. K. Y., Ma, S. Y. K., Tsai, W. W., Wong, C. S., Wong, C. H. T., Wong, T. W., & Yan, D. (2018). Depression and anxiety among university students in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 24(5), 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, H. A., Alhazmi, N. F., Almatrafi, M. K., Almehmadi, S. S., Alharbi, J. K., Qadi, L. R., & Tawakul, A. (2024). The influence of lifestyle on academic performance among health profession students at umm al-qura university. Cureus, 16(3), e56759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M. F., Lord, C., Andrews, J., Juster, R. P., Sindi, S., Arsenault-Lapierre, G., Fiocco, A. J., & Lupien, S. J. (2011). Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 96(4), 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mctiernan, A., Friedenreich, C. M., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Powell, K. E., Macko, R., Buchner, D., Pescatello, L. S., Bloodgood, B., Tennant, B., Vaux-Bjerke, A., George, S. M., Troiano, R. P., & Piercy, K. L. (2019). Physical activity in cancer prevention and survival: A systematic review. Medicine Science in Sports Exercise, 51(6), 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monserrat-Hernandez, M., Checa-Olmos, J. C., Arjona-Garrido, A., Lopez-Liria, R., & Rocamora-Perez, P. (2023). Academic stress in university students: The role of physical exercise and nutrition. Healthcare, 11(17), 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H. T. H., Zhang, C. Q., Phipps, D., Zhang, R., & Hamilton, K. (2021). Effects of anxiety and sleep on academic engagement among university students. Australian Psychologist, 57(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar Kadhim, M., & Rashid, A. (2024). Physical activity and academic stress: Mediating effects on university student anxiety. Heliyon, 10(1), e09876. [Google Scholar]

- Ozen, N. S., Ercan, I., Irgil, E., & Sigirli, D. (2010). Anxiety prevalence and affecting factors among university students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 22(1), 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paricahua Peralta, J. N., Estrada Araoz, E. G., León Hancco, L. B., Avilés Puma, B., Roque Guizada, C., Zevallos Pollito, P. A., Velasquez Giersch, L., Herrera Osorio, A. J., & Isuiza Perez, D. D. (2024). Assessment the mental health of university students in the Peruvian Amazon: A cross-sectional study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología, 4, 7. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9480996&info=resumen&idioma=ENG (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Pesántez-Avilés, F., Cárdenas-Tapia, J., Torres-Toukoumidis, A., & Vintimilla, S. (2024). Understanding academic anxiety in the digital age: An exploratory analysis among university students and the influence of new technologies. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 933, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Khalil, H., Larsen, P., Marnie, C., Pollock, D., Tricco, A. C., & Munn, Z. (2022). Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 20(4), 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J., Sandoval, R. M. O., Torales, J., & Barrios, I. (2024). Mental health in kinesiology and physiotherapy undergraduate students at the Universidad Nacional de Asunción | Salud mental en estudiantes de la carrera de kinesiología y fisioterapia de la Universidad Nacional de Asunción. Revista Del Nacional (Itaugua), 16(2), 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscoya-Tenorio, J. L., Heredia-Rioja, W. V., Morocho-Alburqueque, N., Zeña-Ñañez, S., Hernández-Yépez, P. J., Díaz-Vélez, C., Failoc-Rojas, V. E., & Valladares-Garrido, M. J. (2023). Prevalence and factors associated with anxiety and depression in peruvian medical students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M. L., Gaesser, G. A., Butcher, J. D., Després, J. P., Dishman, R. K., Franklin, B. A., & Garber, C. E. (1998). American college of sports medicine position stand. the recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 30(6), 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X. (2024). The role of social support in mitigating academic stress and anxiety: A cross-sectional study among Chinese college students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(3), 1245. [Google Scholar]

- Rico-González, M., Martín-Moya, R., Giles-Girela, F. J., Ardigò, L. P., & González-Fernández, F. T. (2025). The effects of cardiopulmonary fitness on executive functioning or academic performance in students from early childhood to adolescence? A systematic review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(3), 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocke, K., & Roopchand, X. (2021). Predictors for depression and perceived stress among a small island developing state university population. Psychology Health & Medicine, 26(9), 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M., Cadenas-Sánchez, C., Estévez-López, F., Muñoz, N. E., Mora-Gonzalez, J., Migueles, J. H., Molina-García, P., Henriksson, H., Mena-Molina, A., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., Catena, A., Löf, M., Erickson, K. I., Lubans, D. R., Ortega, F. B., & Esteban-Cornejo, I. (2019). Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 49(9), 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomauro, D. F., Mantilla Herrera, A. M., Shadid, J., Zheng, P., Ashbaugh, C., Pigott, D. M., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Amlag, J. O., Aravkin, A. Y., Bang-Jensen, B. L., Bertolacci, G. J., Bloom, S. S., Castellano, R., Castro, E., Chakrabarti, S., Chattopadhyay, J., Cogen, R. M., Collins, J. K., … Ferrari, A. J. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398(10312), 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B., Olds, T., Curtis, R., Dumuid, D., Virgara, R., Watson, A., Szeto, K., O’Connor, E., Ferguson, T., Eglitis, E., Miatke, A., Simpson, C. E. M., & Maher, C. (2023). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siscovick, D. S., Laporte, R. E., Newman, J., Iverson, D. C. H., & Fielding, J. E. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Reports, 100(2), 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Stonerock, G. L., Hoffman, B. M., Smith, P. J., & Blumenthal, J. A. (2015). Exercise as treatment for anxiety: Systematic review and analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(4), 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y., & He, W. (2023). Meta-analysis of the relationship between university students’ anxiety and academic performance during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1018558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, J. (2024). Mental health and lifestyle habits in Latin American university students after COVID-19. Journal of American College Health, 72(1), 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, A., Tran, L., Geghre, N., Darmon, D., Rampal, M., Brandone, D., Gozzo, J. M., Haas, H., Rebouillat-Savy, K., Caci, H., & Avillach, P. (2017). Health assessment of French university students and risk factors associated with mental health disorders. PLoS ONE, 12(11), e188187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, M., Kentzer, N., Horne, J., Langdown, B., & Smith, L. (2024). Associations between total physical activity levels and academic performance in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 13(1), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully, M. A., Cupples, M. E., Hart, N. D., McEneny, J., McGlade, K. J., Chan, W. S., & Young, I. S. (2007). Randomised controlled trial of home-based walking programmes at and below current recommended levels of exercise in sedentary adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 61(9), 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, A. P. (1998). The Delphi list: A criteria list for quality assessment of randomised clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(12), 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vij, S. (2024). Academic self-concept and anxiety in medical students: Mediating role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1176542. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzschee, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2008). Artículo Especial Declaración de la Iniciativa STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology): Directrices para la comunicación de estudios observacionales (The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology [STROBE] statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies). Gaceta Sanitaria, 22. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0213-91112008000200011 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Wang, Q., Abidin, N. E. Z., Aman, M. S., Wang, N., Ma, L., & Liu, P. (2024). Cultural moderation in sports impact: Exploring sports-induced effects on educational progress, cognitive focus, and social development in Chinese higher education. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Ge, W., Wang, L., Jia, N., Li, S., & Li, D. (2024). Impact of campus closure during COVID-19 on lifestyle, educational performance, and anxiety levels of college students in China. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar, T. M., Williamson, W., Johansen-Berg, H., Dawes, H., Roberts, N., Foster, C., & Sexton, C. E. (2020). A critical evaluation of systematic reviews assessing the effect of chronic physical activity on academic achievement, cognition and the brain in children and adolescents: A systematic review. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R. R., Vaughn, N. A., Hendricks, S. P., McPherson-Myers, P. E., Jia, Q., Willis, S. L., & Rescigno, K. P. (2020). University student food insecurity and academic performance. Journal of American College Health, 68(7), 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunsch, K. (2021). Physical activity, anxiety, and cognitive function in higher education students: A narrative review. Health Psychology Review, 15(2), 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wunsch, K., Fiedler, J., Bachert, P., & Woll, A. (2021). The tridirectional relationship among physical activity, stress, and academic performance in university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarar, F. (2021). Self-efficacy and academic anxiety: A study among Turkish university students. European Journal of Educational Research, 10(1), 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yarar, F., & Telci, E. (2020). Investigation of the effects of physical activity level on academic self-efficacy, anxiety and stress in university students. Pamukkale Medical Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, Y., Chan, C. C., Hillaluddin, A. H., Ahmad Ramli, F. Z., & Mat Saad, Z. (2020). Improving inclusion of students with disabilities in Malaysian higher education. Disability and Society, 35(7), 1145–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, Y., & Borjac, A. (2023). Physical activity and sports performance among Ethiopianuniversity students: The moderating role of self-esteem and the mediating effect of stress. Revista De Psicologia Del Deporte, 32(3), 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zainol, N. A., & Hashim, H. A. (2015). Does exercise habit strength moderate the relationship between emotional distress and short-term memory in Malaysian primary school children? Psychology, Health and Medicine, 20(4), 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamri, F., & Raman, M. (2020). A study on relationship between physical activity, mental health and academic performance among University of Cyberjaya students. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 12(3), 2046–2053. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., Qin, Y., Khalid, S., Tadesse, E., & Gao, C. (2023). A systematic review of the impact of physical activity on cognitive and noncognitive development in Chinese university students. Sustainability, 15(3), 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. (2022). The effect of physical exercise on alleviating the anxiety of minority college students function research. Psychiatria Danubina, 34, S204–S205. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-02668764/full (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Zhu, X., Haegele, J. A., Liu, H., & Yu, F. (2021). Academic stress, physical activity, sleep, and mental health among chinese adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, S. L., Tang, A. R., Richard, K. E., Grisham, C. J., Kuhn, A. W., Bonfield, C. M., & Yengo-Kahn, A. M. (2021). The behavioral, psychological, and social impacts of team sports: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physician and Sportsmedicine, 49(3), 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Terminology | Definition |

|---|---|

| Exercise (Siscovick et al., 1985) | A subset of physical activity that is planned, structured, and repetitive, and has as a final or intermediate objective the improvement or maintenance of physical fitness |

| Physical Activity (PA) (Siscovick et al., 1985) | Defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure. |

| Sport (Guttmann, 2012) | All forms of physical activity which, through casual or organized participation, aim at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental well-being, forming social relationships, or obtaining results in competition at all levels. |

| Author and Year | Method | CEBM | STROBE/PEDro |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Abbasi et al., 2021) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 16 |

| (Alnofaiey et al., 2023) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 22 |

| (Alaaddin et al., 2021) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 21 |

| (Brambila-Tapia et al., 2022) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Chacon-Cuberos et al., 2019) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Duran-Galdo & Mamani-Urrutia, 2021) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 21 |

| (Deisz et al., 2024) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 18 |

| (Foroughi et al., 2022) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 19 |

| (Gallasch et al., 2022) | Cohort | Level 2 | 20 |

| (Islam et al., 2022) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Jarso et al., 2023) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Jamil et al., 2022) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Kayani et al., 2018) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 22 |

| (Kayani et al., 2020) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Kayani et al., 2021) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Kharroubi et al., 2024) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Lobach et al., 2024) | Quasi-exp. | Level 4 | 19 |

| (Lun et al., 2018) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Mahfouz et al., 2024) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 21 |

| (Monserrat-Hernandez et al., 2023) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Piscoya-Tenorio et al., 2023) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 21 |

| (Pérez et al., 2024) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 21 |

| (Tran et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Q. Wang et al., 2024) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 20 |

| (Yusuf & Borjac, 2023) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 17 |

| (Zamri & Raman, 2020) | Cross-sectional | Level 4 | 18 |

| (S. Zhang, 2022) | RCT | Level 1 | 3/10 |

| Author and Year | Subjects | Interv | Anx. Inst. | Anx. Results | Acad. Perf. Inst. | Acad. Perf. Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Abbasi et al., 2021) | 250 | PA | - | not studied | GPA | acad. ↑ |

| (Alaaddin et al., 2021) | 400 | PA | DASS-21 | no effect | GPA | not studied |

| (Alnofaiey et al., 2023) | 2819 | PA | HADS | anx. ↓ | GPA | acad. ↑ |

| (Brambila-Tapia et al., 2022) | 124 | PA | GAD-7 | no effect | GPA | no effect |

| (Chacon-Cuberos et al., 2019) | 225 | PA | MLSQ-SF | anx. ↓ | GPA | no effect |

| (Deisz et al., 2024) | 393 | Exe. | Ques. | anx. ↓ | Ques. | acad. ↑ |

| (Duran-Galdo & Mamani-Urrutia, 2021) | 180 | PA | SISCO | anx. ↓ | - | not studied |

| (Foroughi et al., 2022) | 364 | PA | SADS | anx. ↓ | GPA | acad. ↑ |

| (Gallasch et al., 2022) | 109 | PA | STAI | anx. ↓ | GPA | not studied |

| (Islam et al., 2022) | 482 | PA | Goldb. Scale | anx. ↑ | - | not studied |

| (Jamil et al., 2022) | 130 | PA | GAD-7 | no effect | GPA | not studied |

| (Jarso et al., 2023) | 416 | PA | WTAI | anx. ↓ | GPA | not studied |

| (Kayani et al., 2018) | 358 | PA | Univ. Stress | not studied | GPA | acad. ↑ |

| (Kayani et al., 2020) | 418 | PA | STAI Y-6 | anx. ↓ | - | not studied |

| (Kayani et al., 2021) | 305 | PA | STAI Y-6 | anx. ↓ | Ed. Level | not studied |

| (Kharroubi et al., 2024) | 261 | PA | GAD-7 | anx. ↓ | GPA | acad. ↑ |

| (Lobach et al., 2024) | 76 | PA | EVEA | anx. ↓ | GPA | not studied |

| (Lun et al., 2018) | 1119 | Exe. | GAD-7 | anx. ↓ | Ques. | acad. ↑ |

| (Mahfouz et al., 2024) | 652 | PA | - | not studied | GPA | acad. ↑ |

| (Monserrat-Hernandez et al., 2023) | 742 | PA | SSI | anx. ↓ | - | acad. ↑ |

| (Pérez et al., 2024) | 150 | PA | DASS-21 | no effect | GPA | not studied |

| (Piscoya-Tenorio et al., 2023) | 482 | PA | Goldb. Scale | anx. ↑ | - | not studied |

| (Tran et al., 2017) | 4184 | Exe. | DSM-IV | no effect | - | not studied |

| (Q. Wang et al., 2024) | 413 | Sport | Ques. | not studied | GPA, PEP | acad. ↑ |

| (Yusuf & Borjac, 2023) | 300 | PA | Univ. Stress | anx. ↓ | Acad. Perf. Scale | acad. ↑ |

| (Zamri & Raman, 2020) | 316 | PA | DASS-21 | anx. ↓ | GPA | no effect |

| (S. Zhang, 2022) | 80 | Exe. | SAS | anx. ↓ | GPA | acad. ↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vinueza-Fernández, I.; Esparza, W.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Sánchez-Cajas, E. Anxiety, Academic Performance, and Physical Activity in University Students: A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110231

Vinueza-Fernández I, Esparza W, Martín-Rodríguez A, Sánchez-Cajas E. Anxiety, Academic Performance, and Physical Activity in University Students: A Scoping Review. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(11):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110231

Chicago/Turabian StyleVinueza-Fernández, Israel, Wilmer Esparza, Alexandra Martín-Rodríguez, and Evelyn Sánchez-Cajas. 2025. "Anxiety, Academic Performance, and Physical Activity in University Students: A Scoping Review" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 11: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110231

APA StyleVinueza-Fernández, I., Esparza, W., Martín-Rodríguez, A., & Sánchez-Cajas, E. (2025). Anxiety, Academic Performance, and Physical Activity in University Students: A Scoping Review. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(11), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110231