Abstract

Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) extend geothermal energy beyond conventional hydrothermal resources but face challenges in creating sustainable heat exchangers in low-permeability formations. This review synthesizes achievements from the Utah Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy (FORGE), a field laboratory advancing EGS readiness in 175–230 °C granitic basement. From 2017 to 2025, drilling, multi-stage hydraulic stimulation, and monitoring established feasibility and operating parameters for engineered reservoirs. Hydraulic connectivity was created between highly deviated wells with ~300 ft vertical separation via hydraulic and natural fracture networks, validated by sustained circulation tests achieving 10 bpm injection at 2–3 km depth. Advanced monitoring (DAS, DTS, and microseismic arrays) delivered fracture propagation diagnostics with ~1 m spatial resolution and temporal sampling up to 10 kHz. A data infrastructure of 300+ datasets (>133 TB) supports reproducible ML. Geomechanical analyses showed minimum horizontal stress gradients of 0.74–0.78 psi/ft and N–S to NNE–SSW fractures aligned with maximum horizontal stress. Near-wellbore tortuosity, driving treating pressures to 10,000 psi, underscores completion design optimization, improved proppant transport in high-temperature conditions, and coupled thermos-hydro-mechanical models for long-term prediction, supported by AI platforms including an offline Small Language Model trained on Utah FORGE datasets.

1. Introduction

The transition to sustainable energy systems requires the diversification of renewable resources beyond variable sources such as solar and wind power. Geothermal energy offers unique advantages as a baseload renewable resource capable of continuous operation independent of weather conditions. However, conventional hydrothermal systems are geographically constrained to regions with natural permeability, native fluid, and accessible heat sources [1,2]. EGS technology addresses these limitations by creating engineered subsurface heat exchangers in hot, low-permeability formations through hydraulic stimulation, thereby expanding the geographic potential for geothermal development by orders of magnitude [3,4].

The fundamental EGS concept involves drilling into high-temperature rock formations, creating or enhancing fracture networks through hydraulic stimulation, and establishing circulation pathways between injection and production wells to extract thermal energy. Despite decades of research and field demonstration projects worldwide, including pioneering efforts at Fenton Hill, Soultz-sous-Forêts, and the Cooper Basin, several critical technical challenges have limited commercial deployment. These challenges encompass reservoir creation and sustainability, thermal breakthrough prevention, induced seismicity management, and the economic optimization of drilling and completion operations in high-temperature environments.

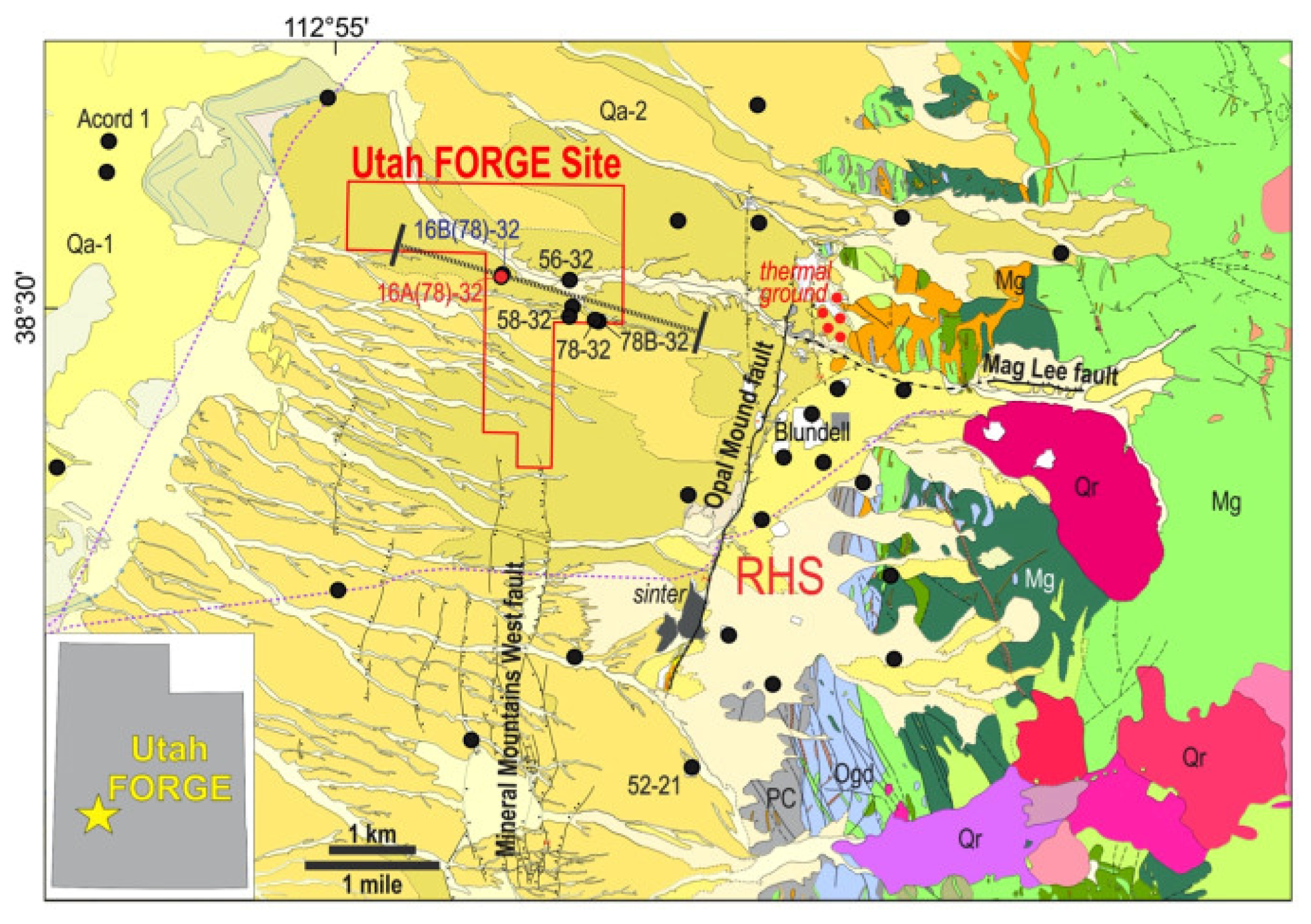

FORGE was developed as a dedicated field laboratory to address fundamental scientific and engineering questions limiting EGS deployment. The site selection criteria emphasized geological simplicity, thermal regime suitability, and operational accessibility, resulting in the designation of a location within the Mineral Mountains pluton near Milford, Utah, as shown in Figure 1. The geological setting features a composite Tertiary plutonic complex with multiple intrusive episodes spanning from the Oligocene to Miocene ages (25.4 Ma to 8 Ma), composed primarily of granite, quartz monzonite, and monzonite. The reservoir exhibits basement temperatures of 175 °C at 1990 m depth, reaching 197 °C at a 2296 m depth, matrix permeabilities less than 30 microdarcies (approximately 3 × 10−17 m2), and a well-characterized normal faulting stress regime with the maximum horizontal (principal) stress oriented NNE-SSW [5].

Figure 1.

Geologic map of the Utah FORGE site and vicinity [5].

The scientific objectives of Utah FORGE encompass multiple interconnected research domains: (1) the development and validation of drilling and completion technologies for high-temperature crystalline environments, (2) the optimization of hydraulic stimulation techniques for creating sustainable fracture networks, (3) the integration of real-time monitoring systems for fracture characterization and reservoir management, (4) the advancement of coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical modeling capabilities, and (5) the establishment of a comprehensive data management infrastructure to support reproducible research and technology transfer.

This review paper is intended as a field-scale, site-centered review that synthesizes the specific achievements and lessons learned from the Utah FORGE project. By examining the geological framework, drilling operations, hydraulic stimulation techniques, reservoir modeling approaches, monitoring systems, and thermal–hydraulic performance at this site, this review provides a comprehensive assessment of progress to date. The paper also identifies key research gaps and future directions for advancing EGS technology toward commercial viability. Through this systematic analysis of the Utah FORGE experience, insights emerge for the global development of Enhanced Geothermal Systems as a significant contributor to the renewable energy portfolio.

Scope of the Review Series: Given the extensive multidisciplinary dataset generated over the project’s decade-long history, this comprehensive review is divided into two parts. Part 1 (This Manuscript): This part focuses on the foundational and construction phases of the FORGE EGS reservoir. It synthesizes the geological characterization and the development of the monitoring/modeling ecosystem required to establish hydraulic connectivity. Part 2 (Future Work): This part will focus on the operational and sustainment phases. It will provide a detailed analysis of long-term circulation testing and thermal drawdown dynamics.

2. Utah FORGE Comprehensive Review

2.1. Geological and Structural Framework

The geological and structural framework of the Utah FORGE (Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy) site is a complex interplay of lithology, tectonic history, and contemporary stress regimes, which are critical for understanding and developing Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) [5]. Multidisciplinary investigations, including drill cuttings and core analyses, geophysical well logs, seismic surveys, and various geomechanical tests, have provided extensive data for a comprehensive geological understanding of the EGS reservoir [6].

2.1.1. Basement Rock Lithology

The deeper wells at the Utah FORGE site intersect a succession of sedimentary basin fill strata overlying crystalline basement rocks [5]. The basement rocks, which host the EGS reservoir, are broadly categorized into four groups: (1) sheared rhyolite; (2) sheared granitoid; (3) granitoid; and (4) interfingered metamorphic and granitoid rocks [5]. These crystalline rocks are part of the Mineral Mountains batholith, a composite pluton that extends westward beneath the alluvial cover from its outcrops in the Mineral Mountains [5].

The igneous constituents within the granitoid-dominated intervals range from granite to diorite. The principal minerals in these plutonic rocks include plagioclase, K-feldspar, and quartz, accompanied by minor biotite, hornblende, clinopyroxene, apatite, titanite, zircon, and magnetite–ilmenite [5]. The dominant lithologies encountered in well 58-32, for instance, are granite, quartz monzonite, and monzonite. Deep within the drilled basement, felsic granitoids are interleaved with metamorphic rocks, primarily orthogneisses [5]. These orthogneisses are mineralogically and compositionally similar to felsic granitoids, complicating their distinction using standard log responses or macroscopic textures in cuttings [5]. Less common, but more readily recognizable due to their distinctive mineralogies, are metasedimentary rocks like marble, quartzite, and schist, which are found engulfed by granitoids [5].

The crystalline basement rocks at FORGE exhibit very low porosity (e.g., <1% in well 58-32) and very low matrix permeability (e.g., 0.3 mD or low microdarcy range). This low native permeability necessitates the creation of an EGS reservoir through hydraulic stimulation to establish conductive pathways for fluid circulation [7,8]. Secondary minerals, such as clay minerals (kaolinite, smectite, illite, and chlorite), Mg- and Fe-carbonates, epidote, actinolite, albite, quartz, and trace anhydrite and halite, are commonly found [5]. These minerals are typically concentrated in fracture zones, reflecting open-space fillings and the replacement of precursor phases, with paragenetic relationships indicating a cooling trend over time [5].

2.1.2. Geologic History

The geological evolution of the Utah FORGE site is a consequence of several significant tectonic and magmatic events. The oldest rocks in the region are Proterozoic gneisses, with a metamorphic age of ~1.7 Ga (or ~1720 Ma), which form isolated rafts intruded by the younger batholith [9].

The Mineral Mountains batholith was emplaced incrementally, with U-Pb zircon dating indicating plutonic activity starting around 25.4 Ma with hornblende diorite intrusion, followed by younger plutonic rocks at ~18 Ma and 11 to 8 Ma [9,10,11]. Igneous activity also included the emplacement of coeval rhyolite and basalt dikes at ~11–12 Ma and later rhyolite domes along the crest of the Mineral Mountains at ~0.5–0.8 Ma [11].

The broader structural setting of FORGE reflects two distinct tectonic events: late Mesozoic to early Cenozoic compression during the Sevier orogeny, and middle Tertiary to recent extension associated with the Basin and Range province [12,13]. The latter is characterized by active extension, crustal thinning, sporadic seismicity, and localized bimodal volcanism. The Basin and Range extension dates back at least ~17 Ma, producing predominantly north–south trending fault zones [12].

A key event for the FORGE reservoir was the uplift and exhumation of the Mineral Mountains batholith [5]. This process induced early plastic deformation, observed as subtle foliation in granitoids, the development of penetrative fabrics typical of metamorphic lithologies, and the formation of narrow mylonite zones up to 30 cm thick. This plastic deformation was subsequently overprinted by later brittle deformation, including shearing, alteration, and veining, which is most intense at the top of the basement and diminishes with increasing depth [5]. The contact between the basin fill and the crystalline basement represents an inactive, gently westward-dipping (~20–35°) Basin and Range bounding normal fault that was rotated eastward during accelerated uplift and exhumation between 10 and 8 Ma [14].

The region also hosts the Roosevelt Hot Springs hydrothermal system, which is associated with young extensional faults, centers of Quaternary basalt–rhyolite magmatism, and high regional heat flow [15]. Geophysical evidence suggests a bimodal felsic–mafic magmatic heat source and a melt body at mid-crustal depths beneath Roosevelt Hot Springs [7,15]. Hydrothermal circulation in this system is inferred to extend to a 7–10 km depth, with activity spanning at least ~2000 years, and possibly more than 100,000 years [15]. Fluid–mineral equilibria and isotopic compositions indicate the deep circulation of meteoric water, acquisition of heat and magmatic volatiles, and protracted high-temperature water–rock interaction [15]. Open-space-filling minerals show paragenetic relationships that record decreasing temperatures over time, from >300 °C to <225 °C, potentially correlating with cooling during exhumation [5].

2.1.3. Faults and Fractures

Fractures are critical components of the FORGE EGS reservoir, acting as the potential pathways for fluid circulation when stimulated. The distribution of fractures in the EGS reservoir is notably heterogeneous, with localized intervals of intense fracturing [5]. Fracturing is generally more common in the upper basement and decreases with depth [5].

- ✓

- Outcrop Fracture Patterns (Mineral Mountains): Field observations in the Mineral Mountains reveal widespread fracturing in basement rocks with three predominant orientations: (1) strike ~090–110° and dip 70–90°; (2) strike ~010–040° and dip 70–90°; and (3) strike ~180° ± 30° and dip 30° ± 30° towards the west [7]. These fracture sets are believed to have formed either before or early during Basin–Range faulting, with the maximum compressive stress being vertical, consistent with a normal fault regime, followed by ~40° of eastward tilt [7].

- ✓

- Wellbore Fracture Patterns (FMI logs, cores): Geophysical logs, particularly Formation MicroImager (FMI) logs, are extensively used to characterize fracture types and orientations in the basement rocks. Approximately 2000 natural fractures were identified in well 58-32, primarily within the basement rocks, with spacing ranging from <1 to 20 per 10 ft interval [16]. These show a predominance of north–south, east–west, and northeast–southwest orientations. Shallower fractures generally dip to the west at ~30°, similar to the basin fill–basement contact, while deeper fractures (below ~1300 m) show steeply dipping E-W and NE-SW trending sets [5]. Well 16A(78)-32, a highly deviated injection well, showed fewer fractures compared to the vertical wells (58-32, 56-32, 78B-32) [5]. However, conductive fractures in 16A(78)-32 occur in localized clusters in two depth ranges (2362–2529 m and 3209–3218 m), often coinciding with lithologic contacts between granitoid and metamorphic domains [5].

Fractures identified from FMI logs are classified into three categories: (1) conductive/open; (2) partially conductive/partially sealed by mineralization; and (3) resistive/sealed by mineralization [7]. Conductive fractures are interpreted as preferred fluid flow paths and often occur in localized clusters at depth, with variable orientations [7]. Core samples provide fine-scale insights into these features. Planar, semi-planar, and unbroken mineralized fractures are observed, with orientations often aligning with the regional stress field. These planar features are more abundant in the finer-grained, darker-colored, banded gneiss than in the coarser-grained granitoid [17].

Major Faults: Several significant faults and fault systems influence the FORGE site, as follows:

- ✓

- Basin Fill–Crystalline Basement Contact: This gently westward-dipping (~20–35°) interface is interpreted as a rotated and eroded basin-bounding normal fault that accommodated significant local tectonic extension between 10 and 8 Ma [14]. Geophysical surveys image this as a strong seismic reflector with modest topography [7,18].

- ✓

- Opal Mound Fault: This is a major north–south trending, ~7 km long fault that forms the western boundary of the Roosevelt Hot Springs hydrothermal system [7]. It has an inferred steep eastward dip with less than 15 m of down-dip vertical offset [15].

- ✓

- Mag Lee Fault: This east–west striking structure can be traced for ~1 km on the surface. It is believed to intersect the Opal Mound fault to the west [5,15].

- ✓

- Mineral Mountains West Fault System: This is a young system composed of multiple normal fault strands, forming a >20 km long N-S corridor of cuspate scarps [5,7,16]. These are not believed to penetrate the basement.

2.1.4. In Situ Stress Conditions

Understanding the in situ stress field, encompassing the magnitudes and orientations of the principal stresses, is paramount for hydraulic fracturing design, wellbore stability, and mitigating induced seismicity in EGS development [19,20].

Stress Orientation and Magnitude Results

- ✓

- Vertical Stress (Sv or σV): The vertical stress is typically derived by integrating density logs from depth to the surface [12,21]. At the FORGE site, the vertical stress gradient (σV) is consistently estimated at approximately 1.13 psi/ft (equivalent to 25.6 kPa/m or 0.0256 MPa/m) [12,22]. This translates to magnitudes of around 58.6 MPa at 2350 m depth [23], 60.77 MPa [24], or 62.80 MPa [25].

- ✓

- Minimum Horizontal Stress (Shmin or σhmin or σ3): Shmin is a critical parameter for hydraulic fracturing design [19,20]. It is primarily assessed through Diagnostic Fracture Injection Testing (DFIT), leak-off tests, microfrac tests, and G-function analysis [20,26]. Multiple interpretations from various tests provide a range of values:

- Initial estimates from G-function analyses yielded gradients of 0.58–0.63 psi/ft, with 0.62 psi/ft being the most likely value [6,12]. These were subsequently judged to be too low—possibly because of wellbore cooldown and the small volumes injected during stress measurement protocols.

- More recent and comprehensive analyses from well 58-32 stimulations suggest a range of 0.74–0.78 psi/ft (16.7–17.6 kPa/m or ~0.017 MPa/m) as the best estimates for Shmin [22,27]. Some analyses in well 16A(78)-32 inferred values from 0.71 to 0.79 psi/ft.

- Magnitude estimates for Shmin include ~31.0 MPa [23] and ~32.5 MPa at 2350 m TVD [28].

- Geomechanical testing in the vertical pilot well 58-32 demonstrated a critical heterogeneity in reservoir stress properties, characterized by a differential in the inferred minimum horizontal stress (σhmin) gradients between two hydraulically isolated intervals. The deepest interval, designated as Zone 1, consists of an approximate 46 m (147 ft) openhole section below the casing shoe, extending from 2248 m measured depth (MD) to 2294 m MD, with gradient calculations typically referenced to a 2262 m true vertical depth (TVD) [20]. The stress interpretations for Zone 1 yielded gradients ranging from 15.2 to 18.8 MPa/km. In sharp contrast, Zone 2, a cased and perforated section situated uphole (perforated over 3 m from 2123 m to 2126 m MD, and referenced at 2122 m TVD), exhibited “apparent” stress gradients that were consistently higher, ranging from 17.2 to 21.5 MPa/km. This differential in closure pressure magnitudes is attributed to several complex geomechanical and hydraulic factors intrinsic to the reservoir and completion method [29,30]. The primary causative mechanisms include near-wellbore tortuosity and associated frictional losses, which are significantly exacerbated when injecting through perforations and casing compared to the openhole section [30,31], and the activation and dilation of natural fractures in Zone 2—intentionally selected for its abundance of pre-existing, near-critically stressed fractures-that were not oriented perpendicular to σhmin [30], and pronounced poroelastic effects, where fluid dissipation into the abundant natural fracture network generates self-induced “back stress” that increases the local total minimum principal stress, especially noticeable in subsequent injection cycles [30,31].

- ✓

- Maximum Horizontal Stress (SHmax or σHmax or σ2): Determining the magnitude of SHmax is more challenging than Sv or Shmin and is a subject of many investigations. Its orientation, however, is reliably inferred from drilling-induced tensile fractures (DIFs) and borehole breakouts observed in image logs.

- ✓

- Orientation: The azimuth of SHmax is consistently NNE-SSW across the region [12,32]. Specific measurements include ~N35°E from well 58-32 DIFs [33], N10°E to N40°E from well 16A(78)-32 DIFs [33], and an average azimuth of 219° (N39E) from natural fractures and 206° (N26E) from DIFs in well 58-32 [7].

- ✓

- Gradients/Magnitudes:

- Initial G-function analyses suggested 0.68–0.82 psi/ft, with 0.77 psi/ft as the most likely value [12].

- Laboratory experiments simulating reservoir conditions for the maximum principal stress (σ1) at the nominal 2350 m (TVD) site are approximately 63.4 MPa, corresponding to a gradient of 27.0 MPa/km. This estimated stress magnitude was utilized in triaxial direct shear (TDS) experiments conducted on cores retrieved from Utah FORGE wells, notably 16A(78)-32 and 58-32, to quantify rock behavior under in situ conditions [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

- Numerical modeling for well 16A(78)-32 indicated gradients of 0.0218 MPa/m, equivalent to 21.8 kPa/m [36,37] or 0.0199 MPa/m (0.88 psi/ft) [38].

- The breakout analysis in well 16A(78)-32 yielded SHmax gradients ranging from 0.84 to 1.39 psi/ft, heavily dependent on the assumed compressive strength of the granite and whether principal stress rotation occurred [27,39].

- The characterization of the maximum horizontal principal stress (σHmax) in the highly deviated well 16A(78)-32 relied upon the analysis of drilling-induced tensile fractures (DIFs) derived from borehole image logs, utilizing two distinct geomechanical methodologies. Method 1 employed a simplified, direct approach where the governing equation for tensile failure (based on DIFs) was solved, treating the σHmax magnitude as the sole unknown parameter [40]. This technique required the pre-determination of all the other parameters, including the minimum horizontal stress (σhmin) magnitude and an assumed orientation for σHmax (e.g., N25°E). The dependence on a single equation led to scattered results, with inferred σHmax gradients ranging from 0.88 to 1.37 psi/ft, a variability which suggested the potential existence of a strike–slip faulting regime in the deeper formations [40]. In contrast, Method 2 implemented a more rigorous, advanced stress inversion technique that simultaneously constrained three unknown parameters: the magnitude of σHmax, the orientation (azimuth) of σHmax, and the fracture trace angle (ω). By solving three non-linear equations concurrently, Method 2 overcame the input uncertainties inherent in the single-parameter method. This inversion approach provided a more consistent and constrained σHmax estimate of 0.87–1.06 psi/ft, reinforcing an interpretation consistent with a normal to transitional normal–strike–slip faulting regime [40].

- The rigorous constraint of the maximum horizontal principal stress (σHmax) gradient range of 0.83–0.98 psi/ft was achieved by integrating borehole failure analyses from the vertical monitoring well, well 78B-32, with independent minimum horizontal stress (σhmin) measurements from injection tests in well 16A(78)-32. This methodology relied on anchoring the geomechanical model with established parameters, including the vertical stress gradient (σV) of 1.13 psi/ft and pore pressure gradient of 0.433 psi/ft, and importing the σhmin range of 0.71–0.75 psi/ft derived from DFITs in 16A(78)-32. The lower bound of σHmax (0.83 psi/ft) was primarily defined by analyzing drilling-induced tensile fractures (DIFs) observed in the well 78B-32 image logs, where the fracture mechanics approach determined the minimum σHmax required to induce these failures. Conversely, the upper bound (0.98 psi/ft) was constrained by reconciling the presence of borehole breakouts (compressive failures) with the DIFs. Because the intact rock compressive strength yielded unrealistically high σHmax values (up to 1.39 psi/ft), the constrained range of 0.83–0.98 psi/ft implicitly defined the effective compressive strength of the borehole rock, suggesting that failure occurred in weaker, pre-existing fracture zones, consistent with the expected normal faulting regime (σV ≥ σHmax ≥ σhmin) [26,27].

Principal Stress Rotation and Critical Angle Analysis

Principal Stress Rotation: The complex geomechanical analysis required for the Utah FORGE site, particularly in the highly deviated well 16A(78)-32, must fundamentally distinguish and integrate two distinct physical and operational realities: the non-vertical trajectory of the wellbore, which was engineered for practical field operations, and the geophysical possibility of a naturally rotated stress field inherent to the reservoir [39,40]. The wellbore trajectory was intentionally designed to deviate 65° from the vertical, extending laterally at an azimuth of ∼105°. This 65° angle was selected as it represented the approximate limit for moving conventional wireline tools into the well by gravity alone. Although specialized conveyance methods, such as wireline tractors (Petromac), and Thru-Bit logging technology were ultimately required for reliability at this angle, the inclination selection was a direct response to operational constraints, ensuring wireline access for critical log acquisition (e.g., FMI and sonic logs) necessary for reservoir characterization, fracture identification, and subsequent stress determination. Furthermore, the azimuth of ∼105° was chosen to be approximately perpendicular to the anticipated σHmax direction (NNE-SSW), aligning the wellbore along the minimum horizontal stress (σhmin) direction to promote the creation of multiple, borehole-transverse hydraulic fractures, optimizing the well for EGS development [39,40].

The second, independent factor is the geophysical phenomenon of principal stress rotation, where the true principal stress axes (σV, σHmax, and σhmin) may not be perfectly aligned with the customary vertical and horizontal directions. This potential rotation is acknowledged based on geological evidence, specifically the inferred block rotation of the Mineral Mountains, though the region is primarily characterized by Basin and Range extension. The rotation can occur either in the plane of the vertical stress (σV) and σhmin or in the plane of σV and σHmax, leading to principal stresses that are not strictly vertical and horizontal. This non-alignment necessitates a complex, multi-step stress transformation process, shifting the measured in situ principal stress state to the geographical coordinate system and then to the wellbore coordinates. For instance, in well 16A(78)-32, observed borehole breakouts exhibited an angle of 30° with respect to the top bottom line, an anomaly that could be caused either by a 10° deviation between the wellbore azimuth (N105°E) and the anticipated σhmin azimuth (N115°E), or by a 25° rotation of the principal stresses. The requirement to mathematically account for this potential rotation highlights the necessary analytical distinction between the drilling path geometry and the true reservoir stress orientation [39,40].

Critical Angle Analysis: Critical stress analysis has been employed to predict which natural fractures are most likely to reactivate or open first during hydraulic stimulation [7]. This involves evaluating the state of stress on existing fractures relative to their shear strength. Studies suggest that NE-SW striking fractures have the highest likelihood of re-opening first [7]. Critically stressed fractures are those that are stimulated at pore pressures between the hydrostatic level and the minimum principal stress [7]. The interaction of hydraulic fractures with pre-existing natural fractures is a complex process, where natural fractures can be destabilized or stabilized depending on their orientation and location relative to the main hydraulic fracture [23,41].

Poroelastic Effects: Observations from injection tests indicate a rate/volume dependency and phenomena such as “self-shadowing,” “back stress,” or “pseudo poroelasticity” [30,31]. These effects imply that the inferred closure stress can increase with pumping rate/volume and in later injection cycles [30,31]. This “back stress” is attributed to poroelasticity in the equivalent porous medium of the natural fracture network, where the dilation and slippage of natural fractures increase the local total stress in the injection region [30,31]. This highlights the significant role of natural fractures in modulating the geomechanical response of the reservoir during stimulation.

Fault Regime Implications and Regional Context

Fault Regime: The overwhelming evidence from stress analyses at Utah FORGE indicates that the in situ stress state is consistent with a normal faulting regime, where the vertical stress (Sv) is the maximum principal stress (Sv > SHmax > Shmin) [12,22,25]. This aligns with the regional extensional tectonics of the Basin and Range province [5,10,12]. However, some analyses, particularly from certain stress inversion methods or anelastic strain recovery (ASR) measurements, have suggested alternative possibilities. ASR is a core-based methodology utilized to measure the time-dependent recovered strain after core samples, typically granitoid material retrieved from well 16B(78)-32 at depths around 4865 ft (∼1483 m TVD), are extracted and relieved of in situ stress. By monitoring the non-isotropic relaxation of the recovered strain over approximately one month, the method aims to reconstruct the principal stresses experienced by the rock. The results from the ASR analysis suggested alternative possibilities:

Strike-Slip Faulting: Method 1 for SHmax estimation in well 16A(78)-32 yielded scattered results (0.88–1.37 psi/ft), suggesting potential strike–slip faulting in deeper formations [40].

Reverse Faulting/Strike-Slip-Normal: ASR experiments on cores from well 16B indicated a stress regime that could be interpreted as reverse faulting (σ3 = 5940 psi, σ2 = 6820 psi) or strike–slip–normal, with principal stresses slightly off-vertical [27]. These variations might reflect local heterogeneities, transitional regimes, or the challenges in interpreting data from complex environments.

Regional Context: The Utah FORGE site is situated on the eastern side of a broad, asymmetric rift basin within the southeast part of the Basin and Range province [5,15]. This region is characterized by ongoing east–west extension, crustal thinning, and localized bimodal volcanism [5,12]. The adjacent Roosevelt Hot Springs hydrothermal system, which contributes to the regional understanding of geothermal activity, also lies within this extensional setting. Geophysical investigations indicate distinct pressure regimes separated by the Opal Mound fault and a low-velocity zone beneath the western Mineral Mountains, suggesting higher basement temperatures and possibly partial melt in the upper crust [7,12]. These regional geological and structural features provide an overarching context for the local conditions observed at the FORGE site.

2.2. Geophysical Monitoring and Seismicity

Geophysical monitoring, particularly seismic monitoring, is a cornerstone of Enhanced Geothermal System (EGS) development at the Utah Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy (FORGE) site. This comprehensive monitoring serves dual purposes: assessing seismic risk and characterizing reservoir development [42]. For seismic risk mitigation, the emphasis is placed on accurate magnitude and ground motion observations, managed through a traffic light system (TLS). Reservoir development monitoring prioritizes microseismic event detection and high-precision location to map and characterize the evolving fracture network [42]. The naturally low-permeability environment at Utah FORGE necessitates hydraulic stimulation to create and enhance fracture systems, making microseismic monitoring crucial for understanding the subsurface response [43,44,45].

2.2.1. Passive and Active Seismic Systems

A multi-scaled seismic monitoring approach has been implemented at Utah FORGE, incorporating diverse seismic network designs and advanced waveform processing techniques to enhance event detection and characterization [42,46].

Surface Monitoring Network

The surface monitoring network at Utah FORGE consists of both permanent and temporary deployments, designed to provide comprehensive coverage and varying levels of resolution [47]. The backbone of this network is the permanent local-scale seismic network operated by the University of Utah Seismograph Stations (UUSS), which includes seismometers and accelerometers located at the surface and in shallow “postholes” (30–40 m deep) [42,47]. A central shallow borehole station, UU. FORK, located directly above the geothermal reservoir, is particularly valuable for detecting seismic activity within the reservoir due to its effective noise reduction [42,47]. This permanent network, integrated into the Utah Regional Seismic Network, is authoritative for the seismic traffic light system, setting magnitude thresholds for induced seismic events to guide injection operations [42,47]. While primarily designed for reliable characterization of M > 1 seismic events, advanced full waveform techniques and calibrated relative locations enable it to provide microseismic event locations for circulation experiments, overcoming its reduced resolution compared to downhole systems.

Temporary deployments have augmented the permanent network, including a nodal array of 150 seismic sensors, which was deployed on the surface during the 2019 stimulation [10]. Another dense nodal geophone deployment in 2022 consisted of 13 patches, each with 16 nodes [48]. These dense arrays provide a mechanism to address specific research questions and temporarily increase focal sphere coverage, though they typically do not allow for real-time monitoring as processing occurs after instrument retrieval [42]. The advantage of deploying clusters of instruments in patches and burying them for noise reduction has been demonstrated [42].

Downhole Monitoring Systems

Downhole monitoring systems are crucial for detecting and accurately mapping low-magnitude microseismicity associated with fracture creation, stimulation, and growth in EGS reservoirs, offering superior signal-to-noise ratios and improved depth resolution compared to surface arrays [43,49]. Various instruments have been deployed in deep boreholes at Utah FORGE:

- ✓

- Geophone Strings: Multi-level geophone strings, typically three-component (3C) digital or analog, have been deployed in monitoring wells such as 56-32, 58-32, 78-32, and 78B-32 [50]. These provide high-precision seismic event catalogs and are considered the most sensitive systems for microseismic monitoring [42]. However, geophone strings face challenges with elevated temperatures, making their long-term operation difficult in the ~200 °C reservoir environment [43]. Their placement typically needs to be shallower than the injection intervals due to temperature limitations, which can impact location accuracy [51]. The use of downhole geophone strings for microseismic monitoring at the Utah FORGE site is fundamentally constrained by the high-temperature environment, thereby imposing significant limitations on both instrument longevity and location accuracy. While initial technological evaluations included tools with temperature ratings up to 195 °C and 225 °C, and analog receivers up to 260 °C [42,50], operational experience revealed that these digital geophone electronics struggled significantly when exposed to ambient borehole temperatures exceeding 180 °C, leading to tool shutdown when internal temperatures reached 160 °C. Critically, to ensure the reliability and longevity of EGS monitoring projects, the current operational policy at Utah FORGE now mandates limiting the temperature exposure for geophone deployment to 150 °C. This enforced temperature ceiling directly dictates the deployment geometry: geophone strings must be placed at the maximum allowable depths based on this temperature restriction, which typically results in the receivers being positioned substantially shallower than the deeper injection intervals (e.g., 1500 to 2000 ft above the 16A(78)-32 injection depths) [42,50]. This suboptimal source–receiver configuration, characterized by receivers being positioned high above the microseismic source area with near-vertical ray paths, severely compromises the azimuthal coverage and aperture of the array, consequently leading to very poor location accuracy, substantial errors in seismic locations, and high uncertainty, especially in the depth coordinate, despite the inherent advantage of lower noise floors compared to surface instruments [42,50].

- ✓

- Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) Cables: Fiber optic cables, acting as Distributed Acoustic Sensors (DAS), have been permanently cemented behind the casing in wells like 78-32, 78B-32, and 16B(78)-32, covering significant lengths of the wellbore [52]. DAS systems measure strain or strain rate with high spatial resolution (e.g., 1 m spatial sampling; 10 m gauge length) and can survive extreme temperatures (up to 265 °C or 500 °C in some cases), making them attractive for long-term monitoring [53]. While DAS is generally less sensitive than 3C geophones and currently cannot directly calculate magnitudes, it provides dense spatial coverage, continuous real-time data, and is effective for event detection and location when integrated with other data [54].

- ✓

- Accelerometers: Accelerometers have been deployed in shallow wells like 68-32, often alongside geophones, to provide additional seismic monitoring data [10].

The deployment geometry of downhole sensors is designed to optimize detection sensitivity and location accuracy, particularly for mapping stimulated fracture volumes and guiding production well placement [43]. Comparisons between DAS and geophones at FORGE have validated DAS’s effectiveness for geothermal monitoring, revealing clearer patterns and greater detail in microseismic event evolution [42].

Active Seismic Surveys

Active seismic surveys complement passive monitoring by providing detailed subsurface structural and velocity information [55].

2.2.2. Microseismic Event Detection and Processing

The detection and processing of microseismic events are critical for understanding the subsurface response to EGS operations.

Detection Algorithms

A variety of detection algorithms have been employed by analysts evaluating Utah FORGE to compile comprehensive microseismic catalogs:

- ✓

- STA/LTA (Short-Term Average/Long-Term Average): This standard detector, sensitive to impulsive phase arrivals, is widely used for event detection in microseismic data [47]. It can be combined with energy-based characteristic functions for more emergent phase arrivals [47].

- ✓

- Subspace Detection Analysis: This method uses singular value decomposition (SVD) to decompose clusters of similar waveforms into basis vectors, which are then scanned against continuous data to find new events belonging to the same family [7,46]. This approach improves the completeness of earthquake catalogs, particularly for periods without additional seismic stations [46].

- ✓

- Matched-Filter Detector: Widely used to develop comprehensive earthquake catalogs by identifying small, previously undetected events (Mw < 0), matched filter detectors are applied to continuous data from borehole stations like FORK to enhance b-value estimations and characterize seismic activity duration [56].

- ✓

- Lassie Detector (pyrocko eco-system): This coherence-based detector exploits the coherence of full-waveform features across the monitoring network and performs well in the high-noise environments that are typical of injection experiments [47]. It combines STA/LTA and energy-based characteristic functions, with the first weighted higher due to generally lower SNRs for P arrivals [47].

- ✓

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN): Machine-learning-based approaches, particularly CNNs, are being developed for automatic, real-time event detection and arrival picking in continuous DAS recordings [57]. These networks can be trained on both registered microseismic events and synthetic data to best incorporate local conditions, demonstrating reliable picking of microseismic arrivals even in challenging wavefields [47,57].

Location Techniques

Accurate event location is paramount for mapping fracture networks. Challenges include velocity model biases, particularly from dipping basement boundaries, and reduced resolution from surface networks [47].

- ✓

- Preliminary Locations (Grid Search): Detectors like Lassie provide preliminary event locations through a migration approach using characteristic functions and coherence analysis on a pre-calculated spatiotemporal grid [47]. However, these locations have high uncertainties due to the tuning of the characteristic function for detection rather than precise location [47].

- ✓

- Relative Relocations: Techniques such as double-difference relocations or hierarchical-clustering-based relocations (e.g., GrowClust.jl) exploit common ray paths for closely located events to refine locations by minimizing differences in phase travel times [42,47]. This approach improves precision, especially when calibrating surface network results with high-quality downhole locations [47].

- ✓

- Source Scanning Algorithm: This algorithm considers a grid of candidate source locations, shifts traces by travel time, and stacks them across the array. The maximum stacked amplitude provides an estimate of the hypocenter location and time. This method leverages large numbers of receivers when the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is low and allows for the visualization of location uncertainty volumes [58].

- ✓

- Machine Learning-based Direct Location: Deep learning methods, such as those based on the DEtection TRansformer (DETR) network, are being developed to directly locate microseismic events in 3D using simultaneous recordings from both surface and borehole sensors [59]. This approach aims to leverage the strengths of both array types while mitigating their individual limitations [59].

An accurate velocity model is fundamental for microseismic monitoring, often built and calibrated using perforation shots and sonic logs [43]. Improvements can also be obtained through tomography with observed microseismic events [58].

Magnitude Calculation

Microseismic event magnitudes are crucial for assessing seismic risk and reservoir characterization.

- ✓

- Local Magnitude (ML) or Coda Magnitude (MC): These are commonly estimated for earthquakes detected by the local broadband seismic network [46].

- ✓

- Moment Magnitude (Mw): This is often determined for microseismic events, with values ranging from Mw −2.3 to +0.5 during stimulations [48]. The seismic moment (M0) is related to Mw and is also used in calculations [60].

- ✓

- Magnitude of Completeness (Mcomp): Establishing a baseline Mcomp is a requirement for the FORGE project [12,46]. With the local broadband and geophone arrays, the Mcomp for the FORGE area has been reduced to around 0.0, significantly lower than the regional network’s Mcomp of 1.5–1.7 [7,12]. This improvement allows for the detection of much smaller events, crucial for detailed reservoir monitoring [7].

DAS Limitation: A current weakness of DAS systems is their inability to directly calculate magnitude, necessitating magnitude estimations from other seismic monitoring instruments [42].

2.2.3. Induced Seismicity Trends

Understanding induced seismicity trends is vital for both operational safety and reservoir understanding.

The spatial distributions of microseismic events at Utah FORGE exhibit distinct spatial distributions, shedding Light on fracture network development and fluid pathways;

- ✓

- Clustering in Source Zones: Earthquakes proximal to the Utah FORGE site tend to cluster in three main areas: near an active quarry (anthropogenic) near the Milford airport (larger events), and in the Mineral Mountains (tectonic, sometimes influenced by the Blundell Power Plant) [7].

- ✓

- Relationship to Injection and Natural Fractures: During stimulations, microseismic events are primarily localized around the Stimulated Reservoir Volume (SRV) or fracture planes, such as the Stage 3 SRV [41]. However, some larger events can occur at the far edges of the seismic cloud, suggesting farther growth of hydraulic fractures or slip on pre-stressed zones [47]. Events during Stage 1 stimulation migrated upward close to the projected location of well 16B(78)-32 and then back along the 16A(78)-32 well course, interpreted as fluid movement along a natural fracture [9]. Stage 2 and 3 events tended to move away from the wellbore as stimulations progressed, with Stage 3 events following two distinct trends at their upper end, indicating the influence of pre-existing fracture zones [9]. The orientation of the circulation-induced seismic cloud aligns with the expected orientation of a hydraulic fracture [42].

- ✓

- Complex Fracture Networks: The microseismic signatures observed do not always suggest purely planar hydraulic fractures, but rather complex fracture networks interacting with natural weaknesses [61]. Source mechanisms indicate that natural fractures play a role in the stimulated rock volumes [49].

- ✓

- Aseismic Zones: Interestingly, the rock volumes corresponding to Stimulation Stages 1 (S1) and 2 (S2) show an aseismic response despite significant fluid flow, indicating that a lack of microseismic activity does not necessarily imply a lack of conductive stimulated fractures [47]. Conversely, the presence of microseismic activity may not always guarantee the presence of stimulated fractures that enable efficient fluid flow. For instance, a quiescence zone within the S3 stimulation area suggests an aseismic reinflation of a previously opened hydraulic fracture [42].

- ✓

- Decoupling of Seismicity and Conductive Flow in S3: Conversely, the S3 zone, which was mapped by a large-scale microseismic cloud during the 2022 stimulation, was seismically highly productive during the circulation stages C2–C4 [47]. However, the presence of this high seismic activity in S3 did not guarantee efficient fluid flow between the injection well (16A(78)-32) and the production well (16B(78)-32) [47]. The circulation tests showed that overall flow was relatively low despite the successful connection via the fracture network. The seismic response of the reservoir during circulation was unexpectedly high, with magnitudes up to M0.45 [47]. This suggests that due to the complexity and intermittent low conductivity of the fracture network within the granitoid rock, simply targeting the seismic cloud (as was performed when drilling 16B) does not guarantee an adequate connection. Numerical simulations further indicated the insufficient connectivity between the highly seismogenic S3 zone and the producer. The observation of a localized quiescent zone within the highly seismically active S3 stimulated rock volume (SRV) provides direct evidence for aseismic mechanical processes occurring within a macroscopically stimulated region. This specific observation reinforces the complexity of linking microseismicity to reservoir engineering metrics.

During circulation, rock volumes within the S3 zone that had exhibited high microseismicity during the initial stimulation treatments became seismically inactive. This specific “quiescence zone” is interpreted as the result of the aseismic reinflation of a previously opened hydraulic fracture. This zone is physically identifiable by the clear spatial separation between the microseismic activity observed during circulation and the original stimulation activity [47]. In maps of relocated microseismicity, this quiescent area appears as a region filled with white circles, representing the location of the previously opened, but now aseismically refilled, fracture. This phenomenon, while initially unexpected given the abundant seismicity nearby, adheres to mechanical principles where the reopening of an already established hydraulic fracture does not necessarily generate the new seismic slip events required for microseismic detection. The resulting microseismic events during circulation clustered predominantly at the far edges of the S3 seismic cloud, suggesting that fluid injection was propagating the fracture beyond the volume previously stimulated, or activating nearby critically stressed features (Segall and Lu, or Albright and Pearson models) rather than re-slipping the main fracture body.

Temporal Evolution

The temporal evolution of seismicity provides insights into reservoir dynamics and fluid–rock interactions.

- ✓

- During and After Pumping: Microseismic signals are recorded both during pumping and, commonly, immediately after pumping during shut-in, with some sporadic signals continuing for some period [61,62]. A significant portion (at least 75%) of the cumulative seismic moment induced during circulation experiments occurs after shut-in [47].

- ✓

- Delayed/Trailing Seismicity: Most circulation-induced events, particularly at the far margins of previously activated seismic clouds, are induced after shut-in, sometimes hours or even days later [41,47]. This delayed seismicity can be attributed to aseismic slip, pore pressure diffusion through a complex fracture network in tight granitoid rocks, or pore pressure redistributions. The delay reflects the time needed for fluid to refill the reservoir or percolate through it to reach critically stressed pre-existing fractures [47].

- ✓

- Reactivation of Clusters: Waveform-based clustering reveals that most clusters are exclusively active within either stimulation or circulation experiments, but some clusters show cross-experiment reactivations during or shortly after injections, particularly at the far edges of the stimulation S3 seismic cloud [41].

- ✓

- No Activity in C1: For the very first circulation stage C1 (the first of four circulation experiments (C1–C4) conducted in July 2023; C1 occurred after the production well (16B(78)-32) was drilled but before its casing was cemented), no induced microseismic activity in the magnitude range > −0.75 was observed, despite fluid injection [47]. This is attributed to low injection pressures and possibly the presence of already naturally fractured zones that accept fluid without significant shear displacement or seismicity [41].

Magnitude Distributions

The distribution of microseismic magnitudes offers further characterization of the induced events.

- ✓

- Low Magnitudes: Most events detected at Utah FORGE are of small magnitude, with many less than M 1.5, and specifically, for the 2019 stimulation, ranging from Mw −2.0 to −0.5 [50]. For the 2022 stimulations, magnitudes ranged from Mw −2.0 to 0.6, with a maximum magnitude of 0.52 recorded during Stage 3 [48].

- ✓

- b-value Estimation: Matched filter detectors are used to enhance catalogs and produce robust b-value estimations, which are valuable for site-specific seismic mitigation strategies [56]. The b-value is a valuable tool in characterizing the seismic regime, as a higher value indicates a greater proportion of small, low-magnitude events relative to large events, often suggesting greater stress heterogeneity. Conversely, a lower b-value may suggest a higher probability of larger, potentially damaging events. For Stage 1, a numerical model yielded a b-value of 2.4, which is close to the field data [63].

- ✓

- Stimulation Stage Differences: The surface network was not sensitive enough to detect much microseismic activity during Stimulation Stages S1 and S2, detecting only a few of the largest events, whereas most events detected occurred during Stage S3 [47]. This is consistent with downhole catalogs showing significantly fewer and smaller events for S1 and S2 compared to S3 [47].

2.2.4. Waveform Analysis and Advanced Processing

Advanced processing of seismic waveforms enhances the understanding of subsurface processes.

Spectral Analysis

Spectral analysis is used for characterizing noise and identifying signals in seismic data.

- ✓

- Frequency Range: Microseismic events typically have a recorded energy of between 3 kHz and 40 kHz [55]. The dominant frequency range recorded by the closest UUSS network stations (FORK, FSB1, FSB2, FSB3, and FOR2) is between 20 and 40 Hz [47]. Noise from well 16A activities during daylight hours is primarily observed in the 10–30 Hz band, with additional noise in the 50–70 Hz range and a persistent 2–10 Hz noise [56]. This higher-frequency, time-dependent noise is predominantly sourced from anthropogenic activities at the well pad, specifically attributed to pump truck noise associated with circulation or stimulation operations during daylight hours. Noise in the 10–30 Hz band, along with activity in the 50–70 Hz range, correlates directly with these operational activities [64].

- ✓

- Power Spectral Density (PSD): PSD analysis is used to characterize noise characteristics and identify frequency bands associated with operational activities [64].

- ✓

- Frequency Domain Detection: Frequency-domain-based algorithms are employed for detecting microseismicity using dense surface seismic arrays, although applying regional-scale methodologies to very local, small-magnitude events can be challenging due to operational noise [56].

Shear Wave Splitting Analysis

Shear wave splitting (SWS) analysis provides critical insights into rock anisotropy and fracture characteristics.

- ✓

- Anisotropic Properties: SWS of three-component borehole microseismic data reveals the anisotropic properties in both sedimentary and granite rocks at the Utah FORGE site [65].

- ✓

- Natural Fracture Density: Averaged Shear Splitting Rate (SSR) values indicate a higher natural fracture density in sedimentary rock (0.91% ± 0.06%) compared to granite rock (0.72% ± 0.09%). This implies that natural fractures play a significant role in fluid flow and mechanical response [65].

- ✓

- Time-lapse Monitoring: Records of micro-earthquakes induced by fracturing allow for the monitoring of Shear-Wave Splitting Rate (SSR) variations in a time-lapse manner, which can track changes in the fracture network over time [65].

Event Clustering and Similarity Analysis

Waveform-based event clustering helps to identify similar events, potential repeaters, and active features in the subsurface.

- ✓

- Waveform Similarity: The similarity of waveforms from microseismic events, as recorded by a seismometer, is a measure of their similarity in terms of location and mechanisms [47].

- ✓

- Clusty Toolbox: The open-source Python 3.11 toolbox Clusty is used for waveform-based event clustering, covering the entire workflow from preprocessing to cross-correlation calculation and clustering. Tuning parameters like frequency range, cross-correlation thresholds, and clustering parameters are crucial, considering local noise levels and network geometry [47].

- ✓

- Identifying Active Features: Low frequencies and lower thresholds are suitable for mapping active features in the subsurface, allowing for gradual waveform changes within a cluster as events migrate [47].

- ✓

- Cross-Experiment Reactivations: Clustering helps visualize interactions between stimulation and circulation experiments, identifying clusters active in both phases, often at the edges of the seismic cloud from prior stimulations. This points to the limited reactivation of multiple patches along pre-existing fractures [47].

Focal Mechanisms

Focal mechanism solutions provide insights into the type of deformation (e.g., tensile vs. shear slip) generating microseismic signals.

- ✓

- Shear Displacements: Detected microseismic signals are predominantly associated with shear displacements, interpreted as either heterogeneities along hydraulic fractures or the critical release of native shear stresses on natural fractures [49].

- ✓

- Tensile vs. Shear Stimulation: The analysis of microseismic records illustrates the geomechanical features of the reservoir rock mass response to stimulation, depicting contributions from both hydraulic fracturing (tensile opening) and shear stimulation mechanisms [41].

- ✓

- Normal Faulting Events: Preliminary studies on microseismic source mechanisms from the 2022 stimulations at FORGE show a dominance of strike–slip events, with some normal fault displacement events occurring deeper within the microseismic cloud [49].

2.2.5. Integrated Interpretation and Modeling

Integrated interpretation and modeling combine diverse datasets to build a holistic understanding of the EGS reservoir.

Integration with Hydraulic Data

Microseismic data ARE correlated with hydraulic parameters to understand fluid flow and fracture behavior.

- ✓

- Pressure–Seismicity Relationship: The onset of microseismicity often corresponds to zones experiencing pressure increases rather than fluid flow alone. Delayed seismicity can be diffusion dominated, reflecting pressure diffusion through the rock mass after shut-in [41]. The FORGE experiments demonstrate a clear decoupling of hydraulic transport and seismic response, confirming that pressure perturbation, not bulk fluid volume movement, is the primary driver of microseismicity [41]. The circulation and stimulation experiments provided compelling evidence that supports the decoupling of fluid transport and seismic energy release. Aseismic Fluid Flow (S1 and S2): During circulation tests (C1–C4), the rock volumes associated with Stimulation Stages 1 (S1) and 2 (S2) exhibited aseismic behavior despite absorbing approximately 70% (170 m3) of the injected fluid volume during C4. This phenomenon demonstrates that substantial, conductive fluid flow, likely through high-permeability, pre-existing natural fractures (DFN), does not necessarily result in detectable microseismicity. The inferred lack of seismicity in S1 and S2 is often attributed to unfavorable fracture orientation, the high cohesive strength of natural fractures, or pressures not exceeding the previous maximum stresses (Kaiser effect) [41]. Seismicity Linked to Pressure Increase (S3): Conversely, the majority of the microseismic events detected during the circulation tests (C2–C4) were concentrated within the stimulated rock volume (SRV) of Stage 3 (S3), which was the most seismically productive zone. Numerical simulations and field data analysis confirm that MEQ activity in S3 correlates predominantly with zones experiencing pressure increases. Numerical modeling suggests that the onset of microseismicity on the periphery of the S3 SRV requires a critical pore pressure increase (Δp) of roughly 2–3 MPa. This observation underscores that pressure perturbation, which reduces the effective normal stress and promotes shear slip, is the primary driver for seismicity in the tight granitoid rock, rather than the bulk volumetric flow [41,47]. Diffusion-Dominated Delayed Seismicity (Trailing Seismicity): The seismic response at FORGE was markedly dominated by events occurring after the pump was shut in (shut-in/trailing seismicity). At least 75% of the cumulative seismic moment induced during the circulation tests (C2–C4) occurred after the injection ceased. This pronounced delay, which included the maximum magnitude events (M ≤ 0.45), is highly characteristic of a diffusion-dominated process within the low-permeability granitoid reservoir. The delay reflects the time required for fluid pressure to percolate through the complex fracture network or rock mass, eventually reaching critically stressed pre-existing fractures at distal locations, leading to slip. This is also linked to aseismic slip and poroelastic coupling, where stress redistribution during shut-in can increase induced seismicity rates in distal locations [41,47].

- ✓

- Pumping Rate and Pressure: Microseismic event rates are observed in conjunction with pumping rates and surface/bottomhole pressures [41]. For instance, seismicity rates may drop during an intentional sudden shut-in during Stage 2 in 2022. After the pumping is resumed, it is difficult to discern if the degree of seismic activity returns to its original level.

- ✓

- Fracture Opening and Slip: Hydraulic stimulation can lead to shear slip and permeability enhancement in granite fractures. The availability of new volume for water to flow into, due to fracture opening, is a key factor, though it may not always be accompanied by seismicity [32].

Integration with Geomechanical Models

Microseismic data is crucial for constraining geomechanical models and understanding reservoir responses.

- ✓

- Discrete Fracture Network (DFN) Models: Microearthquake (MEQ) catalogs are used to create post-stimulation DFN models that potentially capture significant flow pathways [66]. Some DFN fractures are generated to match observed microseismic event locations, while others are stochastic [25]. These models help describe complex fracture patterns resulting from hydraulic fracturing in naturally fractured granites [60].

- ✓

- Numerical Simulations: Lattice-based codes like XSite, which implement synthetic rock mass (SRM) models using the Distinct Element Method (DEM) and lattice method, are used to simulate hydraulic stimulation and circulation tests [63]. These models can simulate microseismic events and compare them with field data to validate the created fracture network geometry and b-value [60].

- ✓

- Reservoir Characterization: Microseismicity is used to characterize fracture density, size distribution, and orientation, which are crucial for determining effective permeability and fluid flow pathways [67]. Numerical history matching, utilizing mapped microseismicity, evaluates the role of natural fractures and their virgin hydraulic conductivity and mechanical properties in constraining slippage, dilation, and hydraulic opening [32].

- ✓

- Mixed-Mode Stimulation: The strong correlation between seismic activity and SRV development suggests a mixed-mode stimulation mechanism involving both hydraulic fracture propagation and interaction with natural fractures, leading to their reactivation [41].

Integration with Fiber Optic Data

The integration of microseismic data with fiber optic distributed sensing (DAS, DSS, and DTS) provides a powerful, high-resolution approach to EGS monitoring.

- ✓

- Complementary Strengths: DAS and geophones have complementary strengths and weaknesses for microseismic monitoring; their integration helps overcome individual limitations [58]. DAS, with its high spatial resolution, can identify large strain changes as potential fracture intersections [68]. The integration can resolve the circular location ambiguities of DAS and decrease the depth uncertainty of surface arrays [58] because a single straight DAS fiber only measures the axial component of strain, which fails to provide the polarization information necessary to constrain the azimuthal angle of the source around the well, resulting in a ring-shaped uncertainty region in the horizontal plane. The large aperture of the surface geophone array is highly effective at constraining the event’s epicenter (horizontal location), thereby collapsing the circular uncertainty ring inherent to the DAS data and selecting the unique preferred location [58].

- ✓

- Strain Measurements (DAS/DSS): DAS measures strain or strain rate, which can be directly related to rock deformation and fracture opening/closing [69]. Low-frequency strain measurements can constrain fracture geometry [69]. During fluid circulation tests, fiber optic cables provide real-time, induced strain and temperature measurements with high spatial resolution and sensitivity [54]. Modeling simulates fluid circulation and computes fiber optic response by plotting strain rates along the producer over time, which can be compared to field measurements [54].

- ✓

- Temperature Measurements (DTS): Distributed Temperature Sensing (DTS) measures temperature along the fiber optic cable, which can indicate fracture intersections or fluid pathways [68].

- ✓

- Real-time Monitoring: The combination of DAS microseismic monitoring and strain sensing allows for the real-time observation of fracture networks, providing insights into fracture dynamics and connectivity [53]. This can revolutionize fracture monitoring by providing high temporal sampling snapshots of fracture evolution, supporting the optimization of stimulation strategies [70].

- ✓

- Fracture Imaging: DAS microseismic reflections can be used for high-resolution hydraulic fracture imaging, revealing internal structures within the granitoid bedrock and delineating hydraulic fractures induced by circulation tests [71]. These internal structures can be correlated with well log data and core analyses, potentially reflecting mineralogical changes and natural fractures [71].

2.3. Petrophysical Measurement Techniques and Data Acquisition

Utah FORGE, with its extensive dataset from numerous wells, core analyses, geophysical surveys, and injection tests, serves as a benchmark for advancing EGS [5]. The objective is to provide data for robust Earth, continuum, and Discrete Fracture Network (DFN) models, which are essential for predicting reservoir behavior, optimizing hydraulic stimulation, and mitigating risks [72].

2.3.1. Lithology and Mineralogy

The EGS reservoir at Utah FORGE is primarily hosted within crystalline basement rocks beneath an alluvial fan and basin fill strata. The intact basement rock is described as a hard, granitic formation [47].

- ✓

- Crystalline Basement (Granitoid, Rhyolite, Orthogneiss, Schist, and Quartzite): The basement is broadly categorized into four groups: (1) sheared rhyolite; (2) sheared granitoid; (3) granitoid; and (4) interfingered metamorphic and granitoid rocks [5]. Igneous rock compositions within granitoid intervals range from granite to diorite, with changes occurring over variable length scales (<1 to >300 m) [5]. Below approximately 2300 m (TVD), metamorphic rocks are primarily orthogneisses, with minor marble, quartzite, and schist engulfed by granitoid. Metasedimentary rocks make up a small proportion (~10 to <100 m thick) of the reservoir rocks [5].

- ✓

- Mineral Composition: The typical mineralogy of this granitoid includes quartz, plagioclase, K-feldspar, biotite, titanite, and hornblende. Orthogneisses are mineralogically and compositionally similar to felsic granitoids [5]. The other minerals present are clinopyroxene, apatite, zircon, and magnetite–ilmenite [73]. The clay minerals, illite and chlorite, constitute <5% of the rock [74]. Diagnostic detection of orthogneiss can rely on sillimanite and garnet, though these occur in low abundances (<1 wt%) [5].

- ✓

- Secondary Mineralization: Secondary minerals, including clay minerals, Mg- and Fe-carbonates, minor epidote, actinolite, albite, quartz, trace anhydrite, and halite, are concentrated in fracture zones [5]. This open space filling and replacement reflects cooling over time [5]. Notably, an unusual carbonate rhomb and fine-grained quartz vein filling occurs sporadically in the basement interval. Secondary minerals can range from <1 to >90 wt% in concentration, correlating strongly with fracture subsets [5]. Impermeable features in core samples are interpreted as closely spaced, curviplanar mineralized fractures [17].

- ✓

- Geochemical Reactivity: Silica sand proppant is unsuitable for future stimulation activities due to dissolution at reservoir temperatures, with bauxite showing laboratory success [28]. The presence of secondary mineralization, particularly carbonates, implies a potential for dissolution/precipitation reactions under EGS operating conditions, contributing to scaling risks [17].

2.3.2. Thermal Properties

The Utah FORGE site is characterized by a high-temperature, thermally conductive regime, indicative of its EGS potential, contrasting with the convective heat transfer of the nearby Roosevelt Hot Springs [5,7,13].

- ✓

- Reservoir Temperature

At the depths drilled, target reservoir temperatures are generally greater than 175 °C [47]. The specific well measurements at FORGE include the following:

- ✓

- Well 58-32: Wireline logs recorded a maximum temperature of 197 °C (387 °F) at a bottomhole measured depth of 2296 m (7536 ft), while subsequent analyses accounting for thermal equilibrium determined a static formation temperature of 199 °C (390 °F) at total depth. Regarding the modeling bound definition, while the top of the reservoir (175 °C isotherm) was measured at 1990 m relative to the Kelly bushing, this boundary is reported as 1983 m (6507 ft) when corrected to Ground Level (GL) [7,10,12,67].

- ✓

- Well 16A(78)-32: The interpreted static shows a formation temperature of 220 °C (428 °F) at a true vertical depth (TVD) of approximately 8560 ft (10,987 ft measured depth. The direct wireline measurement (log data) shows a maximum temperature of 219 °C (426 °F) at a measured depth of 3274 m (10,741 ft); this value represents a specific data point captured by the logging tool at that depth, likely prior to full thermal equilibration or at a depth slightly shallower than the total depth. For the purpose of numerical simulations and general reservoir characterization, the bottomhole temperature is frequently rounded up or estimated to be on the order of 230 °C (446 °F). This value is often adopted in models to represent the thermal regime of the deep granitic reservoir or the “near-toe” conditions for heat extraction simulations. Early preliminary measurements also indicated temperatures at the toe would exceed 228 °C (442 °F) [9,32,51,61].

- ✓

- Well 56-32 and Well 78B-32: The interpreted estimate shows that the temperature profiles for these deep monitoring wells are consistent with the field-wide thermal gradient of approximately 70 °C/km, with the static bottomhole temperatures estimated between 215 °C and 225 °C depending on total vertical depth [7,71,73,75,76].

- ✓

- Thermal Gradients

Wells drilled into the basement rocks at Utah FORGE display linear temperature gradients, averaging 70 °C/km [5,7,13,16,73]. This gradient closely matched the predicted FORGE reservoir gradient [16]. The temperatures in the model region are predicted to range between 60 °C and 250 °C [6]. The gradient in well 58-32 specifically varied between 60° and 90 °C/km depending on bedrock thermal conductivity [7].

- ✓

- Thermal Conductivity

The matrix thermal conductivity for this granitoid is reported as 4.0 W/m-K. For the grain material, a thermal conductivity of 3.15 W/m K has been used in modeling [6]. Cuttings analysis, however, yields 2.0 W m−1 K−1 for sedimentary materials [6]. The measured thermal conductivity values for the granitoid rock in well 58-32 ranged from 2.0 W/m°C in quartz-poor dioritic rock to 3.9 W/m°C in more quartz-rich granite, measured at room temperature [7]. The overall range of thermal conductivity has also been reported to range from 2.27 to 3.58 W/m K [35]. Thermal conductivity is largely controlled by the quartz content of the rock, with higher quartz content correlating with higher thermal conductivity [7]. It also decreases with increasing temperature, necessitating a 10–15% reduction from room temperature measurements for reservoir conditions [7].

- ✓

- Thermal Diffusivity

The thermal diffusivity was found to be 9.71 × 10−7 m2/s for the reservoir rock [77]. Laboratory core tests indicate 1.4 × 10−6 m2/s (0.00218 in2/s) [35].

- ✓

- Specific Heat Capacity

Mass-Based Specific Heat Capacity (J/kg K or J/kg °C)

The variability in reported mass-based specific heat values stems from whether they represent direct laboratory measurements, average matrix properties, or input parameters for large-scale numerical simulations:

- ✓

- Laboratory-Derived Values: Direct measurements on selected cuttings and core samples retrieved from well 58-32 demonstrated specific heats, ranging between 0.7 and 1.0 kJ/kg. °C (700 to 1000 J/kg. °C) [7]. This value range is substantiated as being site-specific by the fact that the measurements were performed on FORGE rock samples (granitoid) and were shown to typically increase with temperature across the reservoir temperature range (25 °C to 200 °C).

- ✓

- Reference Matrix Values: A commonly cited reference value for the granitoid matrix in constitutive and native state models is approximately 790 J/kg. °K (~8.0 × 102 J kg−1 K−1). This value is based on cuttings analysis, the literature reports, and subsequent model calibration for the FORGE granitoid material [6].

- ✓

- Numerical Modeling Inputs: The value of 2063 J/kg. °K is specifically cited in numerical modeling validation exercises as a property value for the FORGE granitoid rock grain density used within the FALCON code to simulate the thermal, hydraulic, and mechanical behavior of the geothermal reservoir [67]. The value of 1200 J/kg. °K is another matrix heat capacity value utilized in specific fluid circulation simulations for Utah FORGE wells.

- ✓

- Total System Value: The total specific heat capacity calculated for stress analysis modeling in well 58-32, accounting for both formation (99%) and fluid (1%) components, was 830 J/(kg. °K), emphasizing the site-specific fluid–rock interaction [20].

- ✓

- Sedimentary Overburden: The value for the overlying sedimentary materials, 8.30 × 102 J Kg−1. °K−1 was used as an input parameter for the FORGE native state model [6].

Volumetric Specific Heat Capacity (kJ/m3 C or kJ/m3 K)

Volumetric heat capacity (ρCp) measures the amount of heat stored per unit volume of rock. The reported values reflect the calculated properties for the bulk reservoir volume, based on measured density and matrix specific heat.

- ✓

- Reservoir Calculation: The reported reservoir volumetric specific heat of 2517.5 kJ/m3⋅°C is a parameter used in volumetric heat-in-place calculations specifically for the FORGE EGS fracture network [75].

- ✓

- Simulation Inputs: The reported range of 1900–2200 kJ/m3 is consistent with calculations using the reference mass-based values and measured bulk density (ρ ≈ 2670 to 2750 kg/m3). For instance, one numerical simulation specifies the volumetric heat capacity of the rock (Cs) as 1950 kJ/K/m3 [19].

- ✓

- Thermal Expansion Coefficient

The thermal expansion coefficients () used for the initial steady-state (native state) modeling efforts at the FORGE site were explicitly defined based on lithology, drawing from the calibrated literature values.

Thermal Expansion Coefficients Used in Steady-State Modeling

The following specific, non-uniform, temperature-invariant thermal expansion coefficients for the two primary lithological units in the native state model were used:

- ✓

- Granitoid Reservoir Rock: . This value was applied to the low-permeability crystalline basement rock which hosts the EGS reservoir [6,67].

- ✓

- Sedimentary Overburden: . This lower value was assigned to the overlying basin fill sedimentary units [6].

These values were adopted from the literature for initial modeling.

Scientific Necessity for Temperature-Dependent Coefficients

The acknowledgment that temperature-dependent thermal expansion coefficients are critical for long-term operational modeling is a statement of crucial scientific and engineering necessity, driven by the profound role of thermoelastic coupling in the physics of EGS.

- Mechanism of Thermoelastic Coupling:

- ✓

- Thermal Contraction and Stress Alteration: During long-term fluid circulation, cold injection fluid (e.g., K or ) enters the high-temperature reservoir rock (up to ). This sustained cooling induces significant thermal contraction in the granitoid matrix. The contraction imposes substantial thermoelastic tensile stresses on the surrounding rock and fractures.

- ✓

- Fracture Dilation and Enhanced Conductivity: This thermally induced tensile stress reduces the effective normal stress acting across existing fractures, causing them to reopen and dilate. Simulations incorporating thermoelasticity for FORGE predict that cooling-induced stresses, potentially reaching thousands of psi, can lead to maximum fracture apertures exceeding 1.5 inches, dramatically increasing fracture conductivity and injectivity [54].

- ✓

- Dynamic Reservoir Evolution: The mechanical stability and geometry of the fracture network are therefore not static but are highly dynamic functions of the thermal field. Accurate, site-specific, temperature-dependent values are necessary because the magnitude of the resulting thermal stress is proportional to and the temperature change (). Implementing temperature-dependent coefficients allows models to accurately forecast critical phenomena such as sharply rising injectivity over the first few months of circulation and potential long-term fracture growth (both upward and downward) driven by thermoelastic effects [26,36].

In essence, using simple, static coefficients is appropriate only for initial steady-state assessments; accurate forecasting of the operational performance, longevity, and fracture evolution of the FORGE reservoir requires the precise quantification of the thermal sensitivity of the rock’s mechanical properties. While the reported temperatures vary between 197 °C and 240 °C, this variance is primarily driven by depth discrepancies between the vertical pilot well (58-32) and the deeper deviated injection wells, and earlier transient log temperatures (<210 °C) should be discarded for reservoir capacity estimation as they reflect drilling-induced cooling. The most robust parameter for the numerical modeling of the EGS doublet is the static reservoir temperature of 225–229 °C, which represents the thermally equilibrated state at the injection depth (~2.5 km TVD).

2.3.3. Hydraulic Properties

The EGS reservoir at the Utah FORGE is characterized by very low natural porosity and permeability, making hydraulic stimulation essential for creating adequate fluid pathways [5,53,78]

Porosity

- ✓

- Matrix Porosity

Intact basement lithologies exhibit very low porosities, generally less than 0.5% [5,6,7,62,76,79]. Laboratory measurements on core samples confirm porosities of less than 0.5% [79]. The granite, quartz monzonite, and monzonite that are dominant within the plutonic rocks form a strong, low-porosity reservoir [12]. Values as low as 0.1% (0.001) are reported for matrix porosity in modeling parameters [80]. This low matrix porosity is characteristic of igneous systems without significant fracturing [62].

- ✓

- Fracture Porosity (Discrete Fracture Network—DFN):