1. Introduction

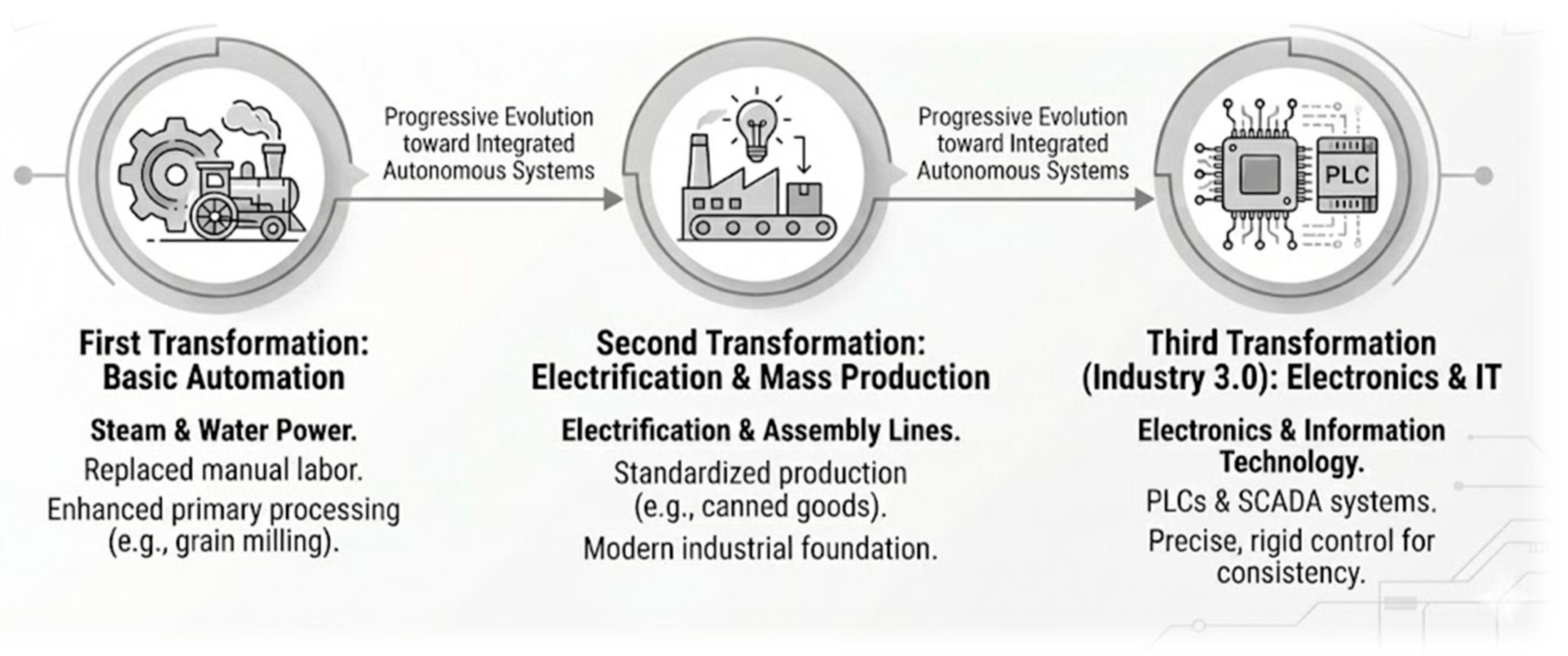

The food processing sector has progressed through distinct evolutionary phases that mirror the broader trajectory of industrial revolutions, transitioning from basic manual labor to highly integrated autonomous systems (

Figure 1). The First Transformation was defined by basic automation, where steam and waterpower replaced hand tools, significantly enhancing the efficiency of primary processing such as grain milling [

1].

This was followed by the Second Transformation, which introduced electrification and mass production [

2]. During the early 20th century, the implementation of assembly lines, pioneered by industry leaders such as Heinz, standardized the production of canned goods and established the foundations of the modern industrial food complex [

3].

The Third Transformation, or Industry 3.0, marked the entry of electronics and information technology into the factory floor [

4]. The adoption of Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems allowed precise control over processing parameters, ensuring consistency in high-speed operations such as automated bottling.

As of 2026, the industry is navigating the complex transition between Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0. While Industry 4.0 was characterized by the deployment of Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), IoT, and centralized Cloud Computing to achieve hyper-efficiency through full automation, Industry 5.0 introduces a fundamental shift in control architecture and operational philosophy [

5]. This transition is characterized by three distinct and measurable shifts. First, control architecture evolves from rigid, centralized automation toward decentralized, adaptive systems, wherein artificial intelligence operates as a cognitive layer rather than a simple rule-based controller. Second, the paradigm of human-AI interaction is moving beyond the replacement of human labor, as seen in Industry 4.0, toward collaborative frameworks. In these models, human expertise complements collaborative robots (cobots), enabling greater flexibility and ethical oversight. Third, the optimization objectives of food processing systems are expanding: rather than focusing solely on operational efficiency (such as speed and cost), there is an increasing emphasis on systemic resilience and sustainability, with long-term stability prioritized over short-term throughput.

Unlike traditional automation, which relies on rule-based logic, AI systems possess the capacity for probabilistic inference, iterative learning, and real-time adaptation. Between 2020 and 2025, AI adoption shifted from experimental pilots to scalable industrial deployments, a transition accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic [

6].

This global event exposed the inherent fragility of manual supply chains and underscored the necessity for contactless, remote-monitored processing technologies [

7]. By 2026, leading global organizations had incorporated artificial intelligence into more than half of their operational workflows, resulting in substantial reductions in operational costs and a strategic shift from energy-intensive thermal processes to AI-optimized non-thermal alternatives [

8]. Despite these advancements, peer-reviewed research reveals persistent challenges in scalability; AI models often underperform in real-world environments due to algorithmic bias and inadequate data standardization.

While global production of wheat, rice, and coarse grains is forecast to show steady upward trends through the 2025–2026 season, this growth is only marginally outpacing utilization levels (

Figure 2).

This narrow surplus is highly unwarranted, as the slow pace of production expansion leaves the global food supply chain vulnerable to environmental volatility and resource scarcity while attempting to scale 70% to meet the needs of 8.5 billion people by 2030 [

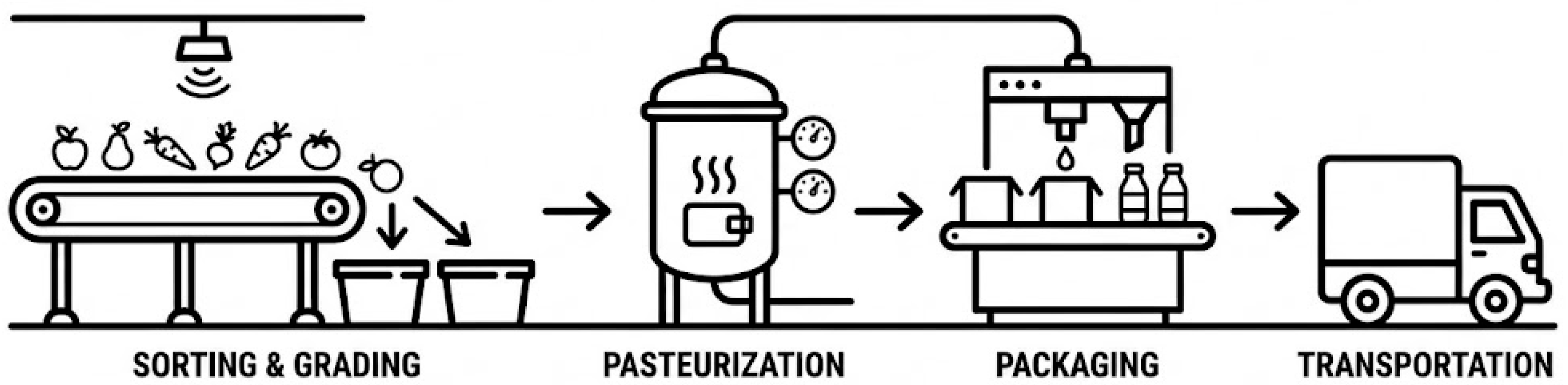

9]. In addition, the modern food processing facilities are high-complexity environments encompassing various unit operations from sorting and grading to pasteurization and packaging that have historically relied on empirical knowledge and manual sampling (

Figure 3).

However, such subjective monitoring is increasingly insufficient for modern lines that process several tons of products per hour. Regulatory frameworks have further catalyzed digital transformation. In both Europe and North America, regulatory frameworks such as the EU Farm to Fork Strategy and the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) demand the necessity for real-time traceability and complete hazard analysis [

10]. On the other hand, in Asia, which contributed half of the global growth in food processing between 2017 and 2021, rapid urbanization has driven the adoption of AI-enabled factories to manage a diverse range of products [

11]. Despite the high degree of automation in modern facilities, the industry remains concerned by systemic inefficiencies that compromise both profitability and sustainability.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that approximately 14% of the world’s food is lost between harvest and the retail level, with significant portions of this waste occurring during the processing phase [

12]. These losses are primarily driven by inaccurate sorting mechanisms where optical sorters often produce high rates of false rejections, discarding viable products alongside defective ones. Furthermore, energy waste remains a critical concern, particularly in thermal processes like drying and sterilization [

13]. In food processing, operational parameters are often set conservatively and remain static to ensure safety, resulting in elevated energy consumption and potential deterioration of nutritional and sensory qualities. While AI-driven optimizations have demonstrated potential for improving efficiency, contradictory findings indicate that such benefits are not universally realized. Studies have reported only marginal energy savings in variable or dynamic environments, frequently attributing these limitations to model overfitting and inconsistent data quality.

The risk profile of food processing is further complicated by microbial contamination and equipment failure. Pathogens such as

Salmonella spp. and

Listeria spp. persist as major threats, yet manual cleaning verification processes remain slow and susceptible to human error. A single contamination event in the current globalized trade environment can trigger recalls costing millions of dollars and damaging brand equity [

14].

Additionally, unplanned equipment downtime creates a flow of waste, as perishable raw materials wait in queues while production lines are discontinued for mechanical maintenance.

These challenges underscore the necessity for a paradigm shift from reactive to predictive and prescriptive operational models. Artificial intelligence offers transformative potential by leveraging real-time sensor data to optimize process parameters, reduce energy consumption, and implement predictive maintenance strategies that address mechanical stress before failures occur. Nevertheless, barriers such as high implementation costs and data privacy concerns have resulted in unsuccessful deployments, particularly among small-scale operations. This technological transition is especially critical in the context of global workforce shortages and elevated labor turnover, highlighting the importance of human-centric, AI-augmented labor to sustain operational continuity.

In this paper, we explore how AI benefits the entire value chain of food processing, starting with supply chain management, where AI optimizes logistics, inventory, and production planning through predictive models that forecast yields and demand with over 85% accuracy, reducing overproduction and enabling precision farming via IoT sensors. We then discuss quality control and safety inspection, where AI excels in non-destructive assessment using computer vision and deep learning to detect defects and contaminants with accuracies exceeding 98%, minimizing recalls and ensuring compliance. Following this, we delve into food engineering, examining AI’s role in optimizing key unit operations such as extrusion, spray drying, and drum drying, where neural networks and digital twins enable real-time adjustments, yielding energy savings of 20–40% and improved product consistency. Another key area covered is AI’s integration into the new food processing business of precision fermentation, which represents a fundamental shift in manufacturing novel proteins at the molecular level using biotechnology.

Finally, we address future trends, sustainability implications, limitations, and perspectives, including the move toward autonomous “dark factories” edge computing, projecting the AI market in food processing to reach nearly $90 billion by 2030.

Review Methodology

To comprehensively examine the transition from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 within the food sector, this study adopts a narrative review framework. Relevant literature was identified through structured searches in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, targeting peer-reviewed articles, conference proceedings, and technical reports published between 2017 and 2025. This period was selected to capture the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence technologies, particularly in response to digitalization trends of the late 2010s and the acceleration of autonomous systems following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Search strategies combined core terms such as “Artificial Intelligence,” “Machine Learning,” and “Deep Learning” with domain-specific keywords including “Food Processing,” “Supply Chain Management,” “Extrusion,” “Spray Drying,” and “Precision Fermentation.” Studies were included if they provided quantitative performance metrics, such as energy reduction or defect detection accuracy, demonstrated in industrial or pilot-scale environments, rather than theoretical simulations. Exclusion criteria eliminated works lacking experimental validation or those focused exclusively on agricultural production without direct relevance to processing. This methodological approach ensures that the review addresses both the theoretical potential and the practical realities of AI integration, bridging the gap between high-level claims and implementation challenges observed in the recent literature.

2. Supply Chain Management

Supply chain management (SCM) is a critical component of the agri-food processing industry, encompassing the coordination of activities from raw material sourcing and production to distribution and consumption [

15]. Its importance lies in ensuring the efficient flow of perishable goods, maintaining food safety, minimizing waste, and meeting consumer demands for quality and sustainability.

In today’s agri-food processing companies, SCM typically operates through a combination of traditional logistical systems, including manual inventory tracking, centralized planning software, and partnerships with suppliers and distributors. For instance, companies rely on enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems to manage orders, track shipments via GPS, and monitor storage conditions in warehouses (

Figure 4).

However, these systems are often linear and reactive, involving sequential stages where raw agricultural inputs like crops or livestock are procured, processed into products such as canned goods or dairy items, and then distributed to retailers [

16]. This setup is prevalent in regions like North America and Europe, where large-scale processors like Tyson Foods or Nestlé use integrated networks to handle high volumes, but it remains fragmented in developing areas due to reliance on smallholder farmers and limited infrastructure [

17].

Despite its foundational role, current SCM in agri-food processing faces significant gaps and challenges. The industry’s inherent complexities, such as seasonality of harvests, perishability of products, and vulnerability to external factors like environmental change, supply disruptions from events like the COVID-19 pandemic, and trade barriers, expose weaknesses in traditional models.

According to recent analyses, supply chain disruptions have led to substantial losses, with estimates from 2025 indicating that agri-food companies experience up to 20–30% inefficiency in inventory management due to inaccurate demand forecasting and poor visibility [

18]. Additional issues include high food waste during transit (contributing to the FAO’s 14% global loss figure), microbial contamination risks from inadequate traceability, and escalating costs from rising energy prices and labor shortages [

19].

In developing regions, broadband limitations and skill gaps further exacerbate these problems, creating an “AI divide” where advanced technologies are underutilized despite high vulnerability.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) addresses these gaps by transforming SCM into proactive, resilient, and data-driven systems, enabling real-time decision-making, predictive risk management, and enhanced transparency. By integrating AI, companies can fill inefficiencies through automated optimization, reducing waste by 20–50% and improving forecasting accuracy to over 85% [

20]. For example, AI-powered predictive analytics can anticipate disruptions from weather patterns or market shifts, allowing for dynamic adjustments in sourcing and routing. This transition not only mitigates economic losses but also advances sustainability by optimizing resource utilization and reducing emissions. Nevertheless, evidence from recent literature indicates that the effectiveness of AI is not universal; its success is highly dependent on contextual factors such as data quality, with certain implementations failing to deliver anticipated benefits in fragmented supply chains.

In the current food sector, Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM) has surpassed traditional logistical tracking to embrace highly autonomous, transparent, and resilient networks powered by AI. The integration of Distributed Artificial Intelligence (DAI) and Machine Learning (ML) transforms the food supply chain from a static linear sequence into a dynamic ecosystem capable of self-organization and real-time optimization.

This technological shift is critical for addressing the inherent complexities of food systems, which are characterized by seasonality and increasing consumer demand for safety and sustainability. The application of these technologies facilitates the rigorous tracking of food products through complex logistical networks, ensuring visibility during transit and allowing for proactive adjustments to supply chain operations.

A significant advancement in ensuring traceability and operational efficiency is the implementation of Multi-Agent Systems (MAS), a subset of DAI [

21]. Unlike traditional centralized control systems, MAS distributes intelligence across a network of autonomous agents, representing suppliers, warehouses, retailers, and brokers, that collaborate to achieve common goals. For instance, in a beef food supply chain model, specific agents collect relevant data and interact with a central Broker Agent to optimize scheduling and resource allocation. This decentralized approach enhances visibility, allowing the food supply chain to adapt to disruptions in real-time rather than waiting for centralized directives.

The coordination between these agents is often facilitated by advanced algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), which are dynamically selected to solve resource-constrained scheduling problems [

22]. This capability allows the food supply chain to “learn” over time, reducing the total duration of scheduling tasks by significant margins compared to random algorithm selection. Parallel to the structural improvements offered by DAI, Machine Learning algorithms provide the analytical depth required for sustainable distribution and risk prediction. In the distribution phase, ML techniques such as deep learning and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) are utilized to predict consumer demand and optimize delivery routes synchronously by analyzing current traffic situations [

23].

This capability is vital for the “last mile” delivery of perishable goods, where delays can lead to significant food waste and economic loss. From a sustainability perspective, ML-driven route optimization and fleet management contribute directly to fuel economy and reduced greenhouse gas emissions, aligning economic performance with environmental stewardship. The application of ML extends deeply into the consumption and planning phases, utilizing distinct strategies for different production models. For “make-to-order” food companies, ML tools facilitate smart product strategies that reduce latency for components, whereas “make-to-stock” companies gain greater profits by implementing smart process strategies. In the consumption phase, Bayesian networks and deep learning models are deployed to forecast consumer buying behavior and perception, analyzing factors that influence purchasing decisions for imported or ready-to-eat foods [

24]. This granular insight allows retailers to manage inventory more effectively, reducing the likelihood of stockouts or spoilage. Furthermore, the integration of these systems promotes social sustainability by improving food safety and creating adequate working environments through better resource planning.

Despite the technological potential, research indicates a significant “AI divide” regarding the vulnerability of supply chains and their receptiveness to these technologies. As illustrated in

Figure 5, on the ease of AI adoption and deployment across supply chain phases, developed regions consistently show higher receptivity to AI, often rated as “very receptive” or “moderately receptive”, particularly in phases like processing and manufacturing, retail management, and international transportation and storage, where expert assessments yield high scores supported by robust infrastructure and skilled workforces [

25]. In contrast, developing regions exhibit lower receptivity, frequently falling into “slightly receptive” or “not at all receptive” categories across the same phases, with notable standard deviations indicating variability due to constraints such as insufficient broadband infrastructure and a lack of skilled human capital.

The phase of “National and International Transport and Storage,” for instance, is identified as highly vulnerable to risks but shows a stark contrast in AI readiness between regions. This disparity highlights that while AI offers high potential for improving traceability and mitigating risks, its deployment is currently constrained in regions that require it most to ensure food security. Consequently, the successful deployment of these intelligent systems requires navigating significant hurdles, including data privacy concerns, the need for substantial infrastructure investment, and the standardization of protocols between disparate AI systems.

To provide clarity on how AI supports various segments of the supply chain, the following table (

Table 1) summarizes key applications, AI subsegments, and concrete examples from companies, agriculture firms, and startups. This serves as guidance and reference for understanding AI’s role across phases.

3. Quality Control and Safety Inspection

Quality control (QC) serves as the cornerstone of the modern food industry, ensuring consumer satisfaction and safety while navigating the complexities of global supply chains. Traditionally, quality assurance has relied heavily on manual inspection and visual signs by human operators. However, these conventional methods are increasingly viewed as time-consuming, inconsistent, and tiresome, necessitating a shift toward automated solutions. A product’s quality is fundamentally defined by the totality of characteristics that satisfy client needs, making the consistent delivery of defect-free goods paramount [

26]. Consequently, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into food processing has revolutionized the field [

27]. By utilizing computer vision and image processing technologies, industrial stakeholders can eliminate subjective QC processes and achieve significant advancements in areas where the human eye lacks sensitivity. This section synthesizes the transformative impact of ML on food QC, examining methodological frameworks, specific classification algorithms, and performance metrics.

The transition from manual to automated inspection requires a robust pipeline capable of handling the biological variability inherent in agricultural products. Fruits and vegetables exhibit a wide range of exterior qualities, such as color, size, and form, even when harvested from the same tree. Furthermore, external factors like fungal infections, temperature, and storage duration can alter product appearance, making consistent grading difficult. To address this, recent research proposes a structured methodology comprising image preprocessing, enhancement, segmentation, and classification [

28].

The initial stage of automated food quality inspection involves image preprocessing to mitigate noise, ensuring robust segmentation. Gaussian filtering smooths images by averaging pixel intensities weighted by a cumulative standard deviation, preserving edges while eliminating artifacts. Subsequent image enhancement via histogram equilibrium contributes to improved contrast, enhancing local details and classifier performance. Image segmentation follows, commonly using K-means clustering to group pixels by shared intensity or traits. This method computes squared Euclidean distances to assign pixels to clusters, isolating regions of interest (ROIs) such as defects or disease spots from backgrounds, paving the way for feature extraction and classification (

Figure 6).

In safety-critical applications, the integration of artificial intelligence with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has enabled real-time detection of pesticides, such as thiram, on apples. Industrial implementations include Nestlé’s visual inspection systems for contaminant detection and the UK Health Security Agency’s use of natural language processing (NLP) to analyze restaurant reviews for signals of foodborne illness. These technological advancements reduce the need for manual oversight, minimize product recalls, and support regulatory compliance [

29,

30].

Despite promising commercial claims, such as Nestlé’s reported 99% detection accuracy, peer-reviewed studies indicate that actual performance may be lower, with validation studies reporting accuracies between 92% and 95% under variable conditions, often due to inconsistencies in lighting. Furthermore, some research highlights the limitations of AI in detecting subtle contaminants, with false positive rates reaching up to 15% in noisy environments. The characteristics of agricultural datasets are particularly influential; high variability in color gradients, occlusions, and environmental noise necessitate the use of large, well-annotated datasets, such as the January Food Benchmark (JFB), comprising 1000 images, for robust benchmarking. Standard evaluation metrics include precision, recall, and F1-score, with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) achieving up to 96% accuracy on standardized datasets, though performance often declines in real-time operational settings.

Uncertainty Quantification and Model Validation

While artificial intelligence models in food processing exhibit high theoretical accuracy, their reliable industrial deployment necessitates rigorous uncertainty quantification, especially in safety-critical applications such as pathogen detection and thermal sterilization. Unlike deterministic control systems, deep learning models are inherently stochastic; therefore, a single prediction regarding food safety is insufficient without an associated confidence interval.

In unit operations of food processing, sensors are frequently exposed to challenging conditions, including high humidity and variable viscosity, which introduce measurement noise into the input data. To maintain robust process control, it is essential to quantify how this sensor error

propagates into the uncertainty of the final AI prediction

. For a process function

that depends on multiple sensor variables

(such as temperature, moisture content, and pressure), the accumulated uncertainty in the output can be approximated using a Taylor series expansion:

where:

is the process function (for example, the AI model’s output), representing the mathematical relationship between the set of input sensor variables and the output of interest. In the context of food processing, typically denotes the output of an AI model or control algorithm that predicts or regulates a process parameter (such as product quality, yield, or safety) based on sensor inputs.

are the input sensor variables, such as temperature, moisture content, or pressure, which are measured during the process and serve as inputs to the function .

is the variance (uncertainty) associated with each input variable . This quantifies the expected fluctuation or measurement error inherent to each sensor.

is the partial derivative of with respect to , which quantifies the sensitivity of the output to changes in the input variable . A higher value indicates that small changes in have a larger effect on the output prediction.

This formulation highlights that even minor sensor variances , such as fluctuations in NIR readings due to steam, can propagate non-linearly to affect the reliability of the AI output.

Furthermore, standard accuracy metrics often mask performance deficits in datasets with high class imbalance, such as detecting rare contaminants or foreign bodies. A model reporting 99% accuracy may fail to detect 100% of contaminants if the contaminant prevalence is below 1%. Therefore, validation protocols must prioritize the F1-score and Recall (Sensitivity) over simple accuracy:

Addressing these statistical limitations is essential to mitigate the “black box” nature of models and prevent false negatives that could lead to costly recalls or public health crises.

4. Process Optimization in Food Engineering

Process optimization in food engineering features the refinement of unit operations to enhance efficiency, product quality, and sustainability, often through the integration of advanced computational tools. The introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized these activities, enabling dynamic, data-driven adjustments that surpass the limitations of traditional control systems. AI’s application to specific technologies such as extrusion, spray drying, drum drying, and agglomeration transforms these processes from empirical, rule-based operations into adaptive, predictive systems capable of real-time decision-making. This section outlines AI’s role in optimizing this key food processing technologies, drawing on recent scholarly advancements to elucidate mechanisms, methodologies, and outcomes. By leveraging machine learning (ML) algorithms, neural networks, and digital twins, AI facilitates granular control over multi-variate parameters, mitigating variability, reducing energy consumption, and improving yield predictability. The section herein is grounded in empirical evidence from peer-reviewed literature, highlighting both established implementations and emerging frontiers, while addressing challenges such as data integration and scalability in industrial contexts.

Throughout the literature, improvements in energy efficiency are typically quantified relative to conventional steady-state operations. To standardize these claims, the efficiency improvement factor,

, is defined as:

where

represents the specific energy consumption (SEC) of the unit operation under traditional PID control with static setpoints. These baselines generally incorporate conservative safety margins, such as prolonged heating durations or elevated-pump pressures, to account for unmodeled disturbances.

In contrast, denotes the SEC under adaptive AI control, where dynamic setpoint modulation enables the system to operate closer to theoretical constraints without compromising safety or product quality. The efficiency gains of 20–40% cited in subsequent sections are derived from this comparative framework, specifically attributing savings to the reduction in thermal overshoot and the minimization of non-productive idle time during changeovers

4.1. AI in Food Extrusion

Food extrusion, a high-shear thermomechanical process integral to the production of cereals, snacks, pet foods, and texturized plant-based proteins, involves complex interactions among moisture content, barrel temperature, screw speed, and feed composition. These variables influence rheological behavior, phase transitions, and final product attributes, rendering traditional proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers inadequate for handling non-linear dynamics and stochastic disturbances [

31]. AI integration addresses these complexities by enabling predictive modeling and autonomous optimization, thereby minimizing waste and enhancing consistency (

Table 2).

Real-time process control exemplifies AI’s utility in extrusion (

Figure 7). Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), particularly multi-layer perceptions, model the required relationships between input parameters and output quality metrics. For instance, ANNs trained on historical extrusion data can predict expansion ratio and textural hardness with R

2 values exceeding 0.95, allowing for immediate parameter adjustments via feedback loops [

32]. Unlike static models, these networks incorporate time-series data from sensors monitoring torque and pressure, facilitating adaptive responses to feedstock variability. In plant-based meat analogs, where fibrous texture emulation is paramount, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) analyze in-line imaging to optimize cooling die configurations, achieving up to 25% improvement in fibril alignment compared to manual tuning [

33].

To rigorously define the optimization task performed by the AI cognitive layer in extrusion, the process is modeled as a multi-objective optimization problem. The control system aims to minimize a cost function, ,which balances deviations in product quality against energy consumption.

Let

n the control input vector at time

, comprising variables such as screw speed

, barrel temperature

, and feed rate

. Similarly, let

n represent the output quality vector, including metrics like expansion ratio

and textural hardness

. The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) serves as a non-linear system estimator,

, which approximates the plant dynamics:

where

is the system delay. The optimization objective over a prediction horizon

is formulated as:

subject to:

Here, ytarget denotes the desired product specifications (e.g., a specific expansion ratio), and represents the weighted Euclidean norm penalizing deviations from target quality. The term SME (Specific Mechanical Energy) quantifies the energy cost, weighted by the regularization parameter λ.

This formulation demonstrates how AI algorithms, such as Hybrid ANN-GA frameworks, explicitly solve the optimal trade-off between energy efficiency and product consistency, achieving reported SME reductions of up to 20% while adhering to operational constraints.

Predictive maintenance further augments extrusion efficiency. Vibration and acoustic sensors, coupled with long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, a recurrent neural network variant, detect anomalies indicative of screw wear or blockages. LSTM models process sequential data to forecast failures with 92% accuracy, scheduling interventions that reduce unplanned downtime by 40% [

34]. Reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms, such as deep Q-networks, extend this by optimizing anti-blocking strategies, learning from simulated extrusion scenarios to adjust screw geometry dynamically [

35]. These advancements not only curtail operational costs but also align with sustainability goals, as optimized extrusion minimizes energy expenditure, typically 30–50% of total process costs [

36].

In a case involving high-moisture extrusion for soy-based meats, a hybrid ANN-genetic algorithm (GA) framework optimized screw speed and temperature, yielding a 35% increase in product yield while reducing specific mechanical energy by 20% [

37]. Challenges persist, however, including data scarcity for rare failure modes and the computational overhead of real-time RL deployment in legacy extruders.

Future research may focus on collaborative learning approaches, enabling multiple facilities to share data and refine AI models without compromising proprietary information. However, contradictory evidence indicates that AI solutions may underperform in small-batch operations, with some studies reporting only 10–15% energy savings compared to commercial claims of up to 40%, often due to model overfitting. Additionally, commercial claims by firms such as Buhler frequently exceed results validated in peer-reviewed benchmarks, which highlight limitations arising from heterogeneous datasets. Typically, datasets for extrusion AI comprise time-series sensor data (e.g., torque, temperature), and benchmarking protocols employ R2 > 0.92 and cross-validation techniques to address noise and variability.

4.2. AI in Spray Drying

Spray drying, an energy-intensive dehydration process employed for powders like milk, instant coffee, and flavors, is susceptible to variations in ambient humidity, atomization pressure, and inlet temperature, which affect particle morphology, solubility, and stability. AI mitigates these sensitivities by enabling precise control over droplet formation and drying kinetics, optimizing energy use while preserving nutritional integrity (

Figure 8).

Morphology and moisture prediction constitute core AI applications. CNNs process high-speed camera feeds to classify particle shapes in real-time, distinguishing desirable spherical agglomerates from irregular, hollow forms that compromise flowability. Coupled with soft sensors, virtual instruments estimating unmeasurable variables like residual moisture, CNNs achieve prediction accuracies of 96%, adjusting airflow rates to maintain optimal particle size distributions [

38]. Generative models, such as variational autoencoders (VAEs), simulate droplet trajectories under varying conditions, forecasting agglomeration tendencies with minimal experimental trials [

39].

Digital twins represent an elevation of AI integration in spray drying. These virtual models, powered by physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), simulate the entire chamber environment, incorporating computational fluid dynamics (CFD) data to predict heat transfer and evaporation rates. Operators can work with scenarios, such as altering nozzle designs, to minimize fouling and energy loss, with reported reductions of 25% in operational costs [

40].

Smart sensors amplify AI’s efficacy, for example, Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy integrated with random forest ensembles monitors powder composition continuously, detecting deviations in protein denaturation or lipid oxidation with 98% precision [

41]. In a dairy powder study, an AI-optimized spray dryer reduced specific energy consumption from 4.5 MJ/kg to 3.2 MJ/kg by dynamically modulating inlet temperatures based on ambient humidity forecasts [

42]. Recent advancements in AI-driven spray drying are summarized in

Table 3, highlighting the synergistic integration of computer vision, digital twins, and smart sensors for powder quality and energy optimization.

However, several limitations persist. Model failures are frequently observed under humid conditions, with contradictory studies reporting that accuracy can decline to approximately 80%. Commercial claims, such as the 98% precision reported by GEA systems, are typically validated only in controlled laboratory environments and do not always translate to industrial-scale operations. Datasets used for these applications often consist of high-dimensional spectral data, which are particularly susceptible to noise introduced by humidity. As a result, benchmarking relies on metrics such as the F1-score and utilizes publicly available datasets to ensure robust and transparent evaluation.

4.3. AI in Drum Drying

Drum drying, suited for viscous slurries like purees and flakes, exhibits non-linear heat transfer and film adhesion dynamics, complicating control. AI introduces hybrid systems with predictive analytics to manage these complexities, ensuring uniform drying without baking or incomplete moisture removal [

43].

Hybrid control systems are paramount. Proportional-integral-fuzzy (PI-fuzzy) controllers augment PID loops with linguistic rules mimicking expert operators, adjusting steam pressure in response to imprecise inputs like “

slightly over-dry”. These systems achieve 15% better moisture uniformity than conventional controls, as evidenced in potato flake production [

44]. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) further refines this by simulating drum rotations, learning optimal speed profiles to minimize energy while maximizing throughput [

45].

Handling non-linearity involves ML models predicting boundary layer effects. Support vector regression (SVR) forecasts drying rates from viscosity and solids content data, with R

2 > 0.92, enabling proactive adjustments to scraper blade angles [

46]. In fruit puree drying, AI-optimized drums reduced burn-on incidents by 50%, extending equipment lifespan [

47].

Despite progress, data noise from steam fluctuations poses hurdles, necessitating robust filtering algorithms. Future avenues include multi-agent systems for synchronized multi-drum line and optimizing collective efficiency in large-scale operations (

Table 4). Performance limitations are frequently observed in processes involving variable viscosities, with studies reporting outcomes that contradict the high energy savings claimed in commercial literature. Datasets used for benchmarking typically include rheological parameters, such as viscosity and solids content, and employ metrics like R

2 and error rates to rigorously evaluate model accuracy.

4.4. AI in Precision Fermentation

The rise in biotechnology has introduced novel proteins through precision and biomass fermentation, representing a fundamental shift in how food is “manufactured” at the molecular level. Precision fermentation utilizes microbes in bioreactors to create bioidentical whey or collagen, effectively reducing land use and supply chain vulnerability [

48]. AI plays a pivotal role in this emerging food processing business by optimizing fermentation processes through advanced modeling and control systems (

Figure 9). Machine learning algorithms analyze vast datasets from sensors monitoring pH, temperature, oxygen levels, and nutrient concentrations, predicting microbial growth kinetics and metabolite production with high accuracy [

49]. For example, deep learning models can forecast yield variations in real-time, allowing for adaptive adjustments that increase efficiency by 25–35% compared to empirical methods. Digital twins simulate bioreactor environments, enabling virtual testing of genetic modifications or media formulations without physical trials, accelerating R&D cycles from months to weeks [

50].

In practice, companies like Perfect Day and Clara Foods leverage AI to produce dairy proteins without animals, using reinforcement to learn fine-tune fermentation parameters for optimal protein expression [

51]. This not only minimizes waste by reducing failed batches but also enhances sustainability by lowering water and energy usage per unit of product. Challenges include scaling models to industrial bioreactors, where fluid dynamics and microbial heterogeneity introduce complexities; however, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) integrate domain knowledge to improve predictions [

52]. Integration with genomics data allows AI to design custom strains, further personalizing outputs for nutritional profiles [

53]. As precision fermentation grows, AI’s role will expand to supply chain integration, forecasting demand for fermented ingredients in alternative meats or functional foods, ensuring this technology addresses global protein demands sustainably (

Table 5).

5. Future Trends, Sustainability, Limitations and Perspectives

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in food processing technologies is posed to redefine the industry’s operational paradigms, fostering a transition toward resilient, efficient and sustainable systems. As we approach 2030, AI’s evolution from experimental applications to core infrastructural components underscores a scholarly imperative to examine its prospective trajectories, environmental imperatives, inherent constraints and forward-looking strategies.

The year 2030 is particularly significant because it aligns with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a global framework adopted by all UN Member States in 2015, which sets ambitious targets to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all. In the context of food processing technologies, the integration of AI is seen as a critical driver for achieving these sustainability goals, including innovation, responsible production, reduced waste, and improved resource efficiency (

Figure 10).

Thus, 2030 serves not only as a milestone for technological advancement but also as a benchmark for measuring progress toward a more sustainable and equitable food system. This section synthesizes recent projections, drawing on interdisciplinary insights from engineering, economics, ethics, and policy domains to provide a rigorous framework for understanding AI’s transformative potential in the food sector.

5.1. Emerging Paradigms and Future Projections

The trajectory of artificial intelligence in food processing indicates a shift from isolated pilot studies toward centralized operational intelligence. A central prospective concept is the “dark factory”, a fully autonomous facility characterized by “lights-out” manufacturing, where human intervention is minimal. Projections suggest that by 2030, such systems could theoretically orchestrate robotics, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and automated guided vehicles (AGVs) to manage repetitive tasks such as sorting and high-speed packaging. While models predict that these autonomous systems could reduce operational costs by 20–40% through minimized downtime, their widespread adoption is currently constrained by significant economic barriers. The capital expenditure (CAPEX) required for the necessary infrastructure, including advanced edge computing and sensor networks, often exceeds $5 million per facility, rendering this model financially prohibitive for most small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs).

Parallel to automation, bio-computing and synthetic biology represent emerging frontiers in food engineering. Tools such as AlphaFold are expanding the capabilities of precision fermentation, potentially enabling the design of specialized “cell factories” (e.g., yeast or fungi) for molecular manufacturing. Generative AI models are being explored for their ability to simulate molecular interactions, which could compress innovation cycles for novel product formulations. However, these applications remain largely within the research and development phase, limited by the computational intensity of molecular simulations and the “black box” nature of deep learning models, which complicates regulatory approval for new food ingredients (

Figure 10).

Market analysts forecast that the AI sector in food manufacturing could expand to approximately $90 billion by 2030, driven by advances in automation and molecular innovation. Nevertheless, this growth is contingent upon resolving persistent challenges related to data heterogeneity, algorithmic transparency, and the high cost of retrofitting legacy “brownfield” sites.

5.2. Sustainability

Sustainability emerges as a core benefit of AI integration, aligning with global imperatives such as the United Nations’ goal of a 70% increase in food production by 2050 while minimizing waste and emissions. AI facilitates optimized processes that reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 15–25% through dynamic energy management and route optimization, while enabling nutrient recycling via upcycling of agricultural by-products (e.g., fruit peels, whey, and wheat middling) into high-value ingredients like natural emulsifiers and texturants. AI-driven waste conversion can transform side-streams into viable products, cutting food waste by millions of pounds annually.

In sustainable packaging, AI revolutionizes eco-friendly solutions by leveraging generative models to design plant-based alternatives, such as mushroom-based compostable boxes or seaweed wraps, reducing material waste by 15–40% and enhancing recyclability. Robotics systems like AMP Robotics’ Cortex employ machine learning for efficient sorting of recyclables, improving global recycling rates from the current 16% baseline. Shelf-life prediction using infrared scanners and predictive analytics further minimizes spoilage, supporting circular economies in waste management and compliance with regulations like California’s SB 1383. Advanced analytics provide real-time tracking of carbon and water footprints per stock-keeping unit (SKU), promoting environmental stewardship. However, a notable challenge is the “Water Paradox”, the substantial water consumption required to cool AI data centers, which necessitates a shift toward energy-efficient edge-computing architectures to mitigate this irony in resource-intensive industries.

5.3. Limitations

Despite its promise, AI adoption in food processing confronts multifaceted limitations that warrant rigorous scholarly analysis. Technically, the “black box” nature of deep learning models poses a significant barrier, particularly in safety-critical applications like microbial contamination detection, where non-transparent decision-making erodes trust and complicates regulatory compliance under frameworks like the EU AI Act. Data heterogeneity, arising from noisy biological inputs influenced by soil variability or weather could intensify future challenges. As an example, and while AI attains 98–99% accuracy in defect detection, the residual 1% risk can precipitate public health crises, underscoring the need for hybrid human-AI systems.

Economically, the Capital expenditure (CAPEX) for AI infrastructure, encompassing sensors, edge computing, and robotics, often exceeds $5 million per facility, deterring small and medium enterprises which comprise 79% of processors delaying initiatives due to cost uncertainties. Converting legacy brownfield sites for autonomous operations entails higher capital expenditure (CAPEX) and technical debt compared to the greenfield construction. The necessity of reconciling modern automated protocols with existing constraints creates substantial integration friction.

Ethically, workforce displacement in “dark factories” threatens low-skilled roles in sorting and packaging, raising dilemmas around job loss and algorithmic bias in procurement or hiring. Data privacy concerns, stemming from incomplete datasets, can lead to inaccurate models, while regulatory gaps hinder global standardization (

Table 6)

5.4. Cybersecurity in Food Digitalization

The rapid digitalization of food processing, driven by AI, IoT sensors, cloud-based analytics, and interconnected Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), which has significantly expanded the attack surface, elevating cybersecurity from a peripheral concern to a critical vulnerability for food safety, supply chain resilience, and public health [

54]. While these technologies enable predictive maintenance, real-time quality monitoring, and optimized operations, they also introduce sophisticated risks such as ransomware, data manipulation, and adversarial AI attacks [

55]. Notably, cyberattacks in the food and agriculture sector surged by 101% from August 2024 to August 2025, with ransomware incidents rising sharply in early 2025. Projections for 2026 highlight IoT as a major attack vector, alongside emerging AI-enhanced threats like automated phishing and reconnaissance [

56].

Key cybersecurity risks include:

Ransomware and Operational Disruption: Attackers target operational technology (OT) systems to halt production lines, resulting in spoilage, waste, and financial losses. High-profile incidents, such as the 2025 attack on United Natural Foods Inc. and the 2024 ransomware event affecting Ahold Delhaize, demonstrate how these disruptions can cascade into food shortages and price spikes.

Process Manipulation and AI-Specific Vulnerabilities: Adversaries may alter sensor data or model inputs, compromising product safety through “digital sabotage” of critical processes like pasteurization or cooling. The “black box” nature of deep learning models exposes systems to adversarial attacks, where subtle data perturbations can mislead defect detection or predictive models, leading to false negatives in quality control. Additionally, interconnected supply chains are increasingly susceptible to cascading failures, especially when legacy systems are exploited.

These risks are compounded by the “digitization paradox”: technologies that enhance efficiency also heighten exposure, particularly for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) with limited resources for robust defenses. Although AI-driven anomaly detection can proactively identify threats, studies show persistent challenges in countering zero-day exploits and insider threats, with residual risks remaining high in heterogeneous environments.

Mitigation strategies, as recommended by frameworks such as CISA’s Food and Agriculture Sector resources, emphasize multi-layered defenses (network segmentation, regular patching, zero-trust architecture) and the adoption of AI/ML for defensive purposes (anomaly detection, automated threat hunting, predictive risk scoring). Additional measures include regular audits, employee training, incident response planning tailored to food perishability, and leveraging voluntary checklists for steps like multi-factor authentication and sector-specific information sharing. Policy initiatives, such as the Farm and Food Cybersecurity Act (2025), aim to mandate baseline protections and enhance information sharing across the sector.

Despite these efforts, significant challenges persist, including high implementation costs that deter adoption among smaller processors, legacy equipment often lacks modern security features, and global regulatory fragmentation hinders standardization. Future research should prioritize resilient, explainable AI cybersecurity frameworks and farmer/processor-centered designs to bridge the “security divide” in vulnerable regions. Without proactive investment, cyber incidents could undermine the very sustainability and safety gains promised by AI integration in food processing.

5.5. Perspectives

Strategic AI integration in food processing necessitates an interdisciplinary governance framework that transitions human capital toward high-level oversight and ethical auditing while delegating “4D” (dark, dirty, dull, dangerous) operations to autonomous systems. Technical transparency is achieved through Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as SHAP and LIME, which facilitate regulatory compliance by attributing model outputs to specific environmental variables. To overcome data fragmentation, Federated Learning (FL) enables decentralized, privacy-preserving model scaling across diverse enterprises.

Economically, the adoption of AI-as-a-Service (AIaaS) and sustainability-linked financing mechanisms effectively bridges CAPEX gaps, particularly for SMEs. These fiscal architectures support the capture of 5–10% “premiums” in export markets by ensuring carbon-transparent production. Ultimately, the synthesis of policy incentives, such as Asia-Pacific “smart-factory” subsidies, and bio-computing integration aligns industrial output with UN sustainability goals, ensuring a scalable and equitable circular economy (

Table 7).