Abstract

A method utilizing quaternion principal component analysis (QPCA) for three-dimensional fluorescence spectral (3D FS) feature extraction is employed to identify frying oil in edible oil. Particle swarm optimization partial least squares support vector machine (PSO-LSSVR) is utilized for detecting frying oil concentration. The study includes rapeseed oil, soybean oil, peanut oil, blending oil, and corn oil samples. Adulteration involves adding frying oil to these edible oils at concentrations of 0%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100%. Firstly, the F7000 fluorescence spectrometer is employed to measure the 3D FS of the adulterated edible oil samples, resulting in the generation of contour maps and 3D FS projections. The excitation wavelengths utilized in these measurements are 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm, while the emission wavelengths span from 220 nm to 900 nm. Secondly, leveraging the automatic peak-finding function of the spectrometer, a quaternion parallel representation model of the 3D FS data for frying oil in edible oil is established using the emission spectra data corresponding to the aforementioned excitation wavelengths. Subsequently, in conjunction with the K-nearest neighbor classification (KNN), three feature extraction methods—summation, modulus, and multiplication quaternion feature extraction—are compared to identify the optimal approach. Thirdly, the extracted features are input into KNN, particle swarm optimization support vector machine (PSO-SVM), and genetic algorithm support vector machine (GA-SVM) classifiers to ascertain the most effective discriminant model for adulterated edible oil. Ultimately, a quantitative model for adulterated edible oil is developed based on partial least squares regression, PSO-SVR and PSO-LSSVR. The results indicate that the classification accuracy of QPCA features combined with PSO-SVM achieved 100%. Furthermore, the PSO-LSSVR quantitative model exhibited the best performance.

1. Introduction

Edible oil is a crucial basic substance for maintaining normal physiological functions in the human body, and its quality and safety are directly linked to consumers’ health [1,2]. When used for frying, edible oil undergoes a series of complex chemical reactions at high temperatures, including oxidation, polymerization, and hydrolysis, with oxygen in the air, moisture in the food, and the food itself. These reactions lead to significant changes in the chemical composition and physical properties of the oil, generating substances like polar compounds, free fatty acids, and peroxides that are harmful to human health. As a result, the originally high-quality edible oil gradually deteriorates into low-quality frying oil [3]. This deteriorated frying oil not only severely destroys the original nutrients in the oil but has also been proven to be closely associated with cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity, and even some cancers [4]. Traditional methods for detecting frying oil, such as physical and chemical index determination and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, are highly accurate. However, they involve complex operations and require high-level professionalism, expensive equipment, and long detection cycles, making them difficult to meet the needs of rapid on-site screening [5]. Therefore, the development of fast, non-destructive, and sensitive detection technology for adulterated edible oil has become a research focus and an urgent requirement in the field of food safety.

Gas chromatography (GC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) are commonly used methods for detecting adulteration in edible oils [6,7,8]. These chromatographic techniques can analyze and compare the types and contents of major components like fatty acids and triglycerides, as well as characteristic components such as sterols and cholesterol, in adulterated and pure edible oils, enabling qualitative and quantitative analysis of adulteration. Although these methods offer high accuracy, their complex and time-consuming preprocessing makes them unsuitable for rapid large-scale sample analysis. In recent years, with the rapid development of spectroscopic technology, it has become a research hotspot due to its advantages of being fast, non-destructive, highly sensitive, and requiring no complex sample pretreatment [9,10]. Zhang Fengjuan conducted a quantitative study on hazelnut oil adulteration using laser Raman spectroscopy, employed principal component analysis for qualitative analysis, and established a partial least squares regression calibration model to quantitatively detect adulterated samples [11]. Among spectroscopic techniques, the three-dimensional excitation-emission matrix (EEM) can effectively distinguish the fluorescence characteristics of different substances or the same substance in different states by simultaneously recording the emission spectra of the sample at different excitation wavelengths. Compared with one-dimensional or two-dimensional spectra, it provides richer information for complex system analysis [12]. This technology has shown great potential in detecting edible oil adulteration and achieved a series of key results. For instance, Hu used three-dimensional fluorescence combined with partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DAs), k-nearest neighbor (KNN), support vector machine (SVM), and random forest (RF) to classify pure vegetable oil with an accuracy of 100% [13]. Jiang used FLS920 steady-state fluorescence spectrometer to collect 3D fluorescence spectrum data, combined with 2D-LDA feature extraction method to identify adulterated sesame oil, with a recognition accuracy of 100%, which is superior to PARAFAC-QDA (85%) and NPLS-DA (95%) methods [14]. Currently, portable fluorescence spectrometers are employed for the detection of algal phyla [15]. This paper utilizes three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy to analyze edible oil. In the future, it may be feasible to realize rapid and real-time detection, with the potential for mobile phone-based detection also being implemented.

Feature extraction is a crucial step in chemometric algorithms. Independent component analysis, wavelet transform, and convolutional neural networks have demonstrated excellent performance in eliminating background interference and extracting features [16,17,18]. However, these algorithms can only handle spectra presented as two-dimensional data and fail to accurately represent the multi-channel characteristics of three-dimensional fluorescence spectra. Quaternions, an extended complex system, can inherently represent and process data with multi-channel and structured features, like color images (RGB three-channel) [19]. The quaternion theory has been applied in image processing, signal analysis, and other fields, and it has shown unique advantages in dealing with multi-channel data [20,21]. Therefore, exploring the application of quaternion principal component analysis in the feature extraction of three-dimensional fluorescence spectra and the detection of frying oil content of edible oil holds significant theoretical and practical value.

SVR, PLSR, and various other prevalent regression analysis methods are employed for 3D FS [22,23,24,25,26]. PSO, a random search algorithm, is based on simulating the foraging behavior of birds. This algorithm is capable of identifying the optimal solution for the research parameters in a minimal timeframe [27]. In comparison to SVR and PLSR algorithms, PSO-LSSVR can identify the ideal key parameters adaptively, avoiding the limitations of artificial parameter selection [28]. The PSO-LSSVR approach combines the benefits of PSO with LSSVR. As a result, the quantitative analytic approach of three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy combined with PSO-LSSVR is used to monitor the concentration of frying oil in edible oil.

This article employs various quaternion feature extraction methods in conjunction with classifiers to develop a judgment model for detecting adulterated edible oil. Subsequently, it establishes a quantitative model for the concentration of frying oil in adulterated edible oils, utilizing partial least squares regression (PLSRs), PSO-SVR, and PSO-LSSVR. The study identifies the optimal judgment model for adulterated edible oil and the quantitative model for frying oil concentration. This research offers a green, rapid, and pollution-free approach for detecting frying oil in edible oils.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

All oil samples were procured from local supermarkets and school canteen, comprising rapeseed oil, soybean oil, peanut oil, blending oil, and corn oil. The frying oil utilized in this study is sourced from the school cafeteria. The food item examined is chicken cutlets, which are cooked at a consistent temperature of 175 degrees Celsius for a duration of 7 min. The oil undergoes approximately 150 cycles per day. Fresh edible oils were adulterated with different concentrations of frying oil, specifically at levels of 0%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100%. Detailed specifications of the edible oils and the frying oil utilized in this study are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Edible oil and frying oil information.

The experimental edible oil samples were systematically labeled to denote their composition. Rapeseed oil samples with varying concentrations of frying oil were labeled C0 to C6; soybean oil samples D0 to D6; peanut oil samples H0 to H6; blended oil samples T0 to T6; and corn oil samples Y0 to Y6. Each oil type included seven distinct concentration gradients (0%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% frying oil). For instance, representative sample configurations for rapeseed oil are detailed in Table 2. Eight replicate samples were prepared for every concentration gradient across all oil types. Prior to analysis, all samples underwent vortex mixing followed by a 24 h equilibration period.

Table 2.

Partial frying oil concentration configuration information (rapeseed oil).

This paper involves the determination of adulterated edible oil and the detection of frying oil content. A total of 360 samples were used for the determination of adulterated edible oil, including 120 samples of edible oil and 240 samples of adulterated edible oil mixed with frying oil of different concentrations. When constructing the frying oil content detection model, there were no pure edible oil samples involved in the model building. There was a total of 240 samples, including 40 samples of 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% frying oil. Prior to analysis, all samples were homogenized using a disposable syringe (20 mL) and subsequently transferred to colorimetric dishes.

2.2. Fluorescence Spectral Acquisition

Fluorescence spectra were acquired using an F-7000 spectrometer (Hitachi High-Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). Measurements employed a 10 mm path length non-fluorescent quartz cuvette. Instrumental parameters were configured as follows: excitation range 200–890 nm (20 nm increment, 5 nm slit), emission range 220–900 nm (10 nm increment, 5 nm slit), scan rate 30,000 nm/min, photomultiplier tube voltage 520 V, and 150 W xenon excitation source. In order to reduce the difference in fluorescence intensity caused by the time change in instrument and light source and ensure the accuracy of measurement, the spectrometer needs to be preheated for 20 min before each collection and the average of three measurements for each sample is taken as the final measurement result. All data analyses were performed in MATLAB (v. 2018a, MathWorks, Torrance, CA, USA), with visualizations generated using Origin2017 and Visio 2003 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

2.3. Technical Roadmap

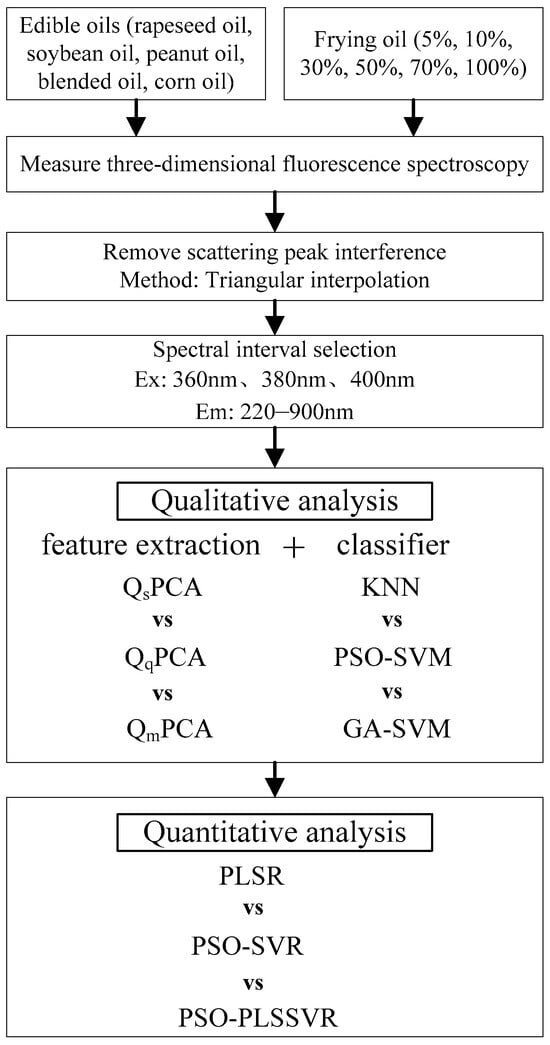

The overall technical workflow of this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Technical workflow.

Initially, three-dimensional fluorescence spectral data were acquired for pure edible oils and for edible oils adulterated with frying oil at varying concentrations. Subsequent to data collection, Rayleigh scattering regions were removed to eliminate artifacts that may interfere with spectral analysis. An automated peak-detection algorithm was then applied to extract key spectral features, including peak positions and fluorescence intensities. The preprocessed spectral data were subjected to qualitative analysis to determine the presence of frying oil adulteration. For this purpose, the following three feature extraction methods were employed: summation quaternion principal component analysis (QsPCA), modular quaternion principal component analysis (QqPCA), and multiplication quaternion principal component analysis (QmPCA). Classification was performed using the following three machine learning algorithms: KNN, PSO-SVM, and GA-SVM. For samples confirmed to contain frying oil, quantitative analysis was conducted to predict the adulteration level. This was achieved using regression models, including PLSR, PSO-SVR, and PSO-LSSVR.

3. Results

3.1. Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Experimental measurements were performed on the 3D FS of the following five edible oils: rapeseed oil, soybean oil, peanut oil, blended oil, and corn oil. Additionally, frying oils were analyzed, which were doped with varying concentrations of 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100%. A total of 24 samples were collected for each of the five edible oils, while 40 samples were obtained for the frying oils at each concentration level, resulting in a cumulative total of 360 samples. The three-dimensional fluorescence spectra were generated using Origin2017 drawing software.

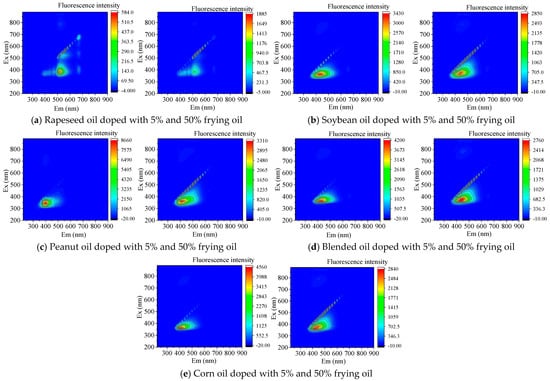

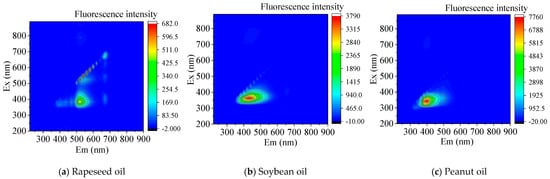

Due to the large sample size, only the contour map obtained by averaging the data of five different brands of edible oils mixed with 5% and 50% frying oil, namely rapeseed oil, soybean oil, peanut oil, blended oil, and corn oil, are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The contour spectrum and three−dimensional fluorescence spectra of 5% and 50% frying oil doped in edible oils.

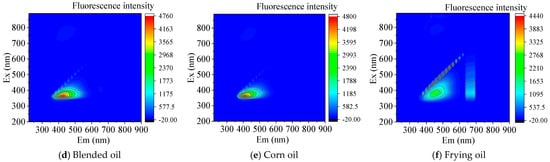

Figure 3 shows that the contour plots obtained by averaging the data of six oil samples (pure rapeseed oil, soybean oil, peanut oil, blended oil, corn oil, and frying oil).

Figure 3.

Contour maps of five types of pure edible oils and pure frying oil.

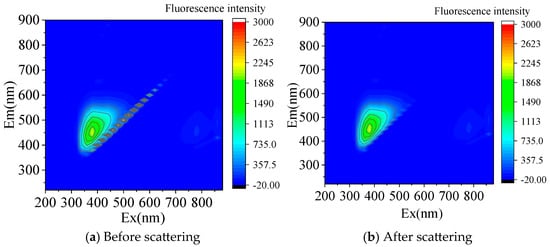

3.2. Removing the Rayleigh Scattering Peak

Based on the original 3D FS, it is known that the 3D FS of the five brands of edible oil and frying oil all have scattering peaks, which differ greatly from the fluorescence intensity values of the effective information in the 3D FS, and have strong interference, even covering the effective information. These scattering peaks belong to interference information unrelated to the measured substance and must be removed; otherwise, it will affect the accuracy of the model. This article uses the triangle interpolation method to eliminate scattering peaks [29]. The 3D FS of the fried oil samples before and after scattering are shown in Figure 4a,b.

Figure 4.

Three−dimensional fluorescence spectra of frying oil before scattering and after scattering.

3.3. Determination of Adulteration of Edible Oil

3.3.1. Selection of 3D FS Range

In the establishment of the adulterated edible oil judgment model, 120 pure edible oil samples and 120 adulterated edible oil samples measured experimentally were used, totaling 240 samples. The 3D FS of 240 samples was measured. The 3D FS of frying oil samples in edible oil was obtained through Origin2017 software. Due to the large quantity, Figure 1 only shows that contour plots and three-dimensional fluorescence spectra of 5% and 50% frying oil samples mixed with rapeseed oil, soybean oil, peanut oil, blended oil, and corn oil, based on the automatic peak-finding function of the spectrometer, as well as the ability to obtain the optimal excitation wavelength, fluorescence emission wavelength range, emission spectrum peak position, and fluorescence intensity from contour spectra and 3D FS. The fluorescence spectral information of different frying oil concentrations in five types of edible oils is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fluorescence spectrum information of fried oils with different concentrations in five kinds of edible oils.

Table 3 and Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that the optimal excitation wavelength for almost all five types of edible oils and edible oils doped with different concentrations of frying oil is 360 nm, and the emission wavelength range is 220–900 nm. The fluorescence intensity of the emission lines at the excitation wavelengths of 380 nm and 400 nm is also high. The fluorescence peak positions of the five types of edible oils and edible oils doped with different concentrations of frying oil are relatively close at the three excitation wavelengths. Therefore, some chemometric methods need to be applied for analysis.

3.3.2. Quaternion Parallel Representation Model

According to Table 3 and Figure 2 and Figure 3, the fluorescence spectrometer automatically searches for peaks. Since the quaternion has only three imaginary parts, three excitation wavelengths of 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm were selected for model establishment. The specific formula steps used in the method can refer to Formulas (S1)–(S10) in the Supplementary Materials.

By means of quaternion matrix, the emission spectra of three randomly selected excitation wavelengths can be characterized in parallel. As a form of complex number, a quaternion consists of one real part and three imaginary parts. A quaternion parallel representation model for three-dimensional fluorescence spectra was constructed, where the three imaginary parts of the quaternion are used to describe the fluorescence intensity of each emission spectrum under three excitation wavelengths, respectively. The emission wavelength range is set from 220 nm to 900 nm with a step size of 10 nm, and each sample is composed of seven quaternion fluorescence intensity information to form a quaternion vector.

The expression of the quaternion matrix is as follows [30,31]:

In the formula, is the number of samples, is the number of emission wavelengths, and represents the fluorescence intensity data corresponding to different emission spectra of the sample under three excitation wavelengths.

The expression of is defined as [32]:

where are three excitation wavelengths and is the emission wavelength.

3.3.3. Feature Extraction of Quaternion Principal Component

Quaternion principal component feature extraction was performed on the quaternion parallel representation matrix of the three-dimensional fluorescence spectrum of algae and the expression is:

The real part and three imaginary parts of each quaternion principal component were fused, and the fused features are obtained as follows:

In the formulas, denotes multiplicative feature fusion, denotes modulus feature fusion, and denotes summation feature fusion.

Based on the basic principles of QPCA, a total of 240 samples, including 120 samples of pure edible oil and 120 samples of edible oil mixed with frying oil, were subjected to quaternion parallel expression, and their data matrices were subjected to quaternion principal component feature extraction.

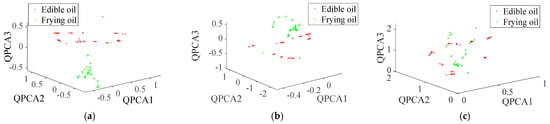

When using quaternion summation, modulus, and multiplication feature extraction and when the number of quaternion principal components is 6, 16, and 11, respectively, the cumulative contribution rate of quaternion principal components can reach 99.99%, which can almost reflect all the information of the 3D FS of edible oil and mixed frying oil. The principal component analysis graphs of summation, modulus, and multiplication quaternions are shown in Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

Summation, modulus, and multiplication quaternion principal component analysis diagram. (a) Summation quaternion feature extraction; (b) modulus quaternion feature extraction; and (c) multiplication quaternion feature extraction.

Figure 5 shows that the summation quaternion feature extraction and modulus quaternion feature extraction can effectively distinguish between edible oil and frying oil. The multiplication quaternion feature extraction can basically distinguish between edible oil and frying oil. Between them, the extraction of quaternion features through summation can be achieved by using fewer quaternion principal components for differentiation. Therefore, the method of extracting quaternion features through summation is more suitable for identifying adulteration in edible oils.

3.3.4. Comparison of Results from Different Feature Extraction Methods

The laboratory obtained 120 samples of pure edible oil and 120 samples of edible oil mixed with frying oil, for a total of 240 samples. Select fluorescence spectral data with excitation wavelengths of 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm, and use multiplication, modulus, and summation quaternion feature extraction as inputs for K-nearest neighbor classifiers. Select 180 samples as the training set and the remaining 60 samples as the test set. Label pure edible oil samples as 1 and edible oil samples doped with frying oil as 2 and establish a judgment model for adulterated edible oil. The classification accuracy results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Recognition results of different feature extraction methods.

The KNN algorithm operates as a classifier based on vector similarity. Initially, it identifies three data points (k = 3) nearest to the target sample through Euclidean distance calculations. This distance metric quantifies the similarity between samples, followed by the application of a weighted voting system to determine the final class label.

Table 4 shows that modulus quaternion feature extraction and summation quaternion feature extraction as inputs to the K-nearest neighbor classifier can both achieve 100% classification accuracy. The classification accuracy of multiplication quaternion feature extraction combined with K-nearest neighbors reached 92.5%. When extracting quaternion summation features, only selecting the first four quaternion principal components can achieve the determination of adulterated edible oil. In order to obtain a better judgment model for adulterated edible oil, the following is a comparative analysis of classification methods.

3.3.5. Comparison of Results from Different Classification Methods

In order to obtain a better judgment model for adulterated edible oil, the following is a comparative analysis of classification methods.

The laboratory obtained 120 samples of pure edible oil and 120 samples of edible oil mixed with frying oil, for a total of 240 samples. Select fluorescence spectral data at excitation wavelengths of 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm, and use the data extracted by summation quaternion features as inputs for KNN, PSO-SVM, and GA-SVM. Select 180 samples as the training set and the remaining 60 samples as the testing set. Label pure edible oil samples as 1 and edible oil samples doped with frying oil as 2 and establish a judgment model for adulterated edible oil.

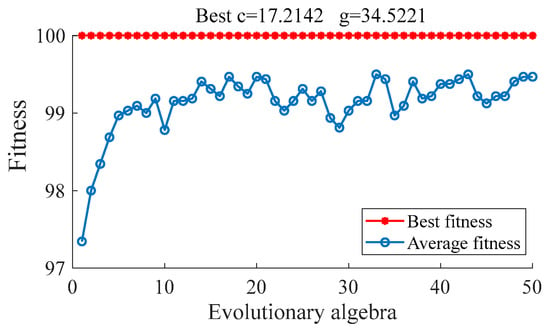

The PSO algorithm can improve the classification accuracy of the SVM classification model. Two important parameters (penalty coefficient and kernel function parameters ) in the SVM model were improved and optimized, and the results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Particle swarm optimization fitness curve for PSO-SVM model.

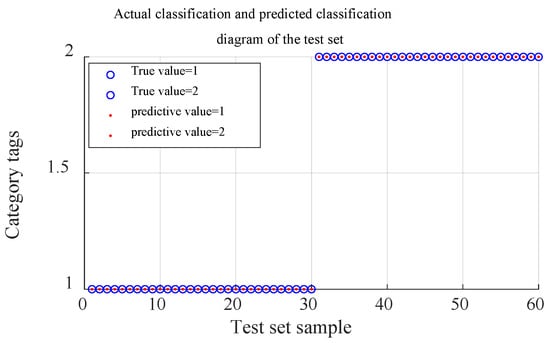

As shown in Figure 6, the particle swarm can quickly search for the optimal solution of the model parameters within 100 iterations. The optimal penalty parameter and kernel function parameter are 17.2142 and 34.5221, respectively. By inputting the values of and into the SVM simulation model, the classification accuracy is 100%. The actual and predicted classification graphs of the test set are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Actual and predicted classification maps of the test set.

Genetic optimization algorithm also improves and optimizes the penalty coefficient and kernel function parameters. The classification results of three algorithms, namely KNN, PSO-SVM, and GA-SVM, are compared and shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Recognition results of different classification methods.

Table 5 illustrates that when fluorescence spectrum data are selected at excitation wavelengths of 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm, the data derived from summation quaternion feature extraction can serve as inputs for the K-nearest neighbor classifier, particle swarm optimization support vector machine, and genetic optimization support vector machine, all of which attain an accuracy of 100%. Among these, the algorithm employing the least quaternion principal component is the PSO-SVM algorithm.

In summary, the laboratory obtained 120 samples of pure edible oil and 120 samples of edible oil mixed with frying oil, for a total of 240 samples. Selecting fluorescence spectral data at excitation wavelengths of 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm, and extracting data using summation quaternion features, only the first three quaternion principal component features need to be selected as inputs for PSO-SVM to establish a detection model for adulterated edible oil. The classification accuracy of the model can reach 100%.

3.4. Establishment of Quantitative Model for Frying Oil

This paper adopts the principle of qualitative analysis followed by quantitative analysis to establish a judgment model for the proportion of frying oil in adulterated edible oil.

The experiment obtained 40 edible oil samples doped with 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% frying oil, for a total of 240 samples. Select fluorescence spectral data at excitation wavelengths of 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm as inputs for PLSR, PSO-SVR, and PSO-LSSVR, respectively, to establish a quantitative model for the proportion of frying oil in adulterated edible oil. The results obtained from the three quantitative analysis methods are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

The results obtained from the three quantitative analysis methods.

Figure 2 and Table 3 show that the optimal excitation wavelength for mixing frying oil with different concentrations in the five edible oils is almost all 360 nm, and the emission wavelength range is 220–900 nm. The fluorescence intensity of the emission lines at the excitation wavelengths of 380 nm and 400 nm is also relatively high. The fluorescence peak positions of frying oil with different concentrations in the five edible oils are relatively close at the three excitation wavelengths. Therefore, chemometric methods need to be applied for analysis. Figure 2 shows that the scattering peak changes with the concentration of the mixed frying oil, so the scattering peak is not removed.

3.4.1. PLSR Model

Based on partial least squares regression algorithm, 69 × 3 independent variables were selected to form a regression relationship with the dependent variable of frying oil concentration, and the optimal latent variable LV value was determined. The PLSR regression model and its model parameters corresponding to the optimal LV were statistically tested. The independent variable matrix X and the dependent variable matrix Y were input into PLSR, and the results of obtaining the independent and dependent variable information are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Information on independent and dependent variables.

Table 7 shows that 20 PLS latent variables were selected based on leave-one cross-validation and these 20 PLS latent variable components reflect 42.049% of the independent variable information and 88.2625% of the dependent variable information.

Input the number of latent variables into the MATLAB software, and the regression model provides a training set correlation coefficient of 0.8684, a testing set correlation coefficient of 0.5076, a training set root mean square error of 0.1638, and a testing set root mean square error of 0.6524. From this, it can be seen that using partial least squares regression method to establish a quantitative model of frying oil concentration in adulterated edible oil cannot achieve good regression accuracy.

3.4.2. PSO-SVR Model

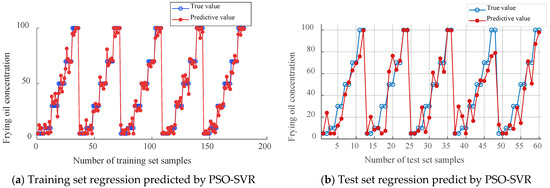

Based on the 3D FS data of 240 frying oil samples, 180 samples were randomly selected as the training set, and the remaining 60 samples were used as the testing set. Then, 69 × 3 features of each sample were used as inputs for the PSO-SVR quantitative model to establish a quantitative detection model for frying oil concentration in adulterated edible oil. The relationship between frying oil concentration and the true values of the training and testing sets is shown in Figure 8. The specific formula steps used in the method can refer to Formulas (S11)–(S24) in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 8.

Relation diagram of deep-frying oil concentration and truth value of training set and test set.

Table 6 and Figure 8 show the quantitative analysis model for frying oil concentration established using the PSO-SVR algorithm. The correlation coefficient of the training set is 0.9532 and the root mean square error is 0.5412. The correlation coefficient of the test set is 0.9118 and the error of the test set is 0.6325. The difference between the predicted and actual values of frying oil concentration is small, and the model has high prediction accuracy, which can reflect the true situation of frying oil concentration.

3.4.3. PSO-LSSVR Model

The PSO-LSSVR algorithm simultaneously utilizes the fast convergence and strong global search ability of PSO, as well as the small-sample learning ability and simple calculation of LS-SVR algorithm, to improve the learning and generalization ability of the model [33,34,35].

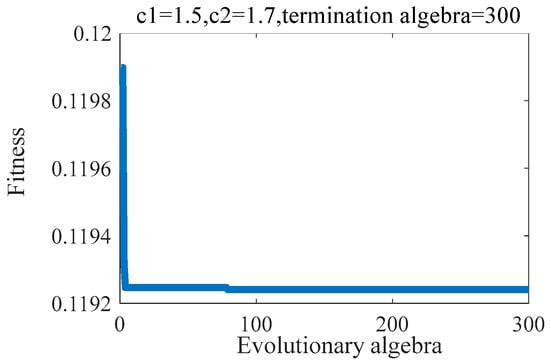

Based on the three-dimensional fluorescence spectrum data of 240 frying oil samples, 180 samples were randomly selected as the training set and the remaining 60 samples were used as the testing set. Then, 69 × 3 features of each sample were used as inputs for the PSO-LSSVR model. During particle swarm optimization, the fitness curve is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Particle swarm optimization fitness curve for PSO-LSSVR model.

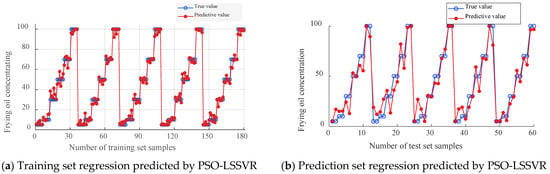

The fitness shows a state of decreasing first and then stabilizing, indicating that the process of optimizing penalty coefficient and kernel function parameters is normal. The relationship between the concentration of frying oil and the true values of the training set and testing set is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Relation diagram of deep-frying oil concentration and truth value of training set and test set.

Table 6 and Figure 10 show the quantitative analysis model for frying oil concentration established using the PSO-LSSVR algorithm. The correlation coefficient of the training set is 0.9886 and the root mean square error is 0.4315. The correlation coefficient of the test set is 0.9663 and the error of the test set is 0.3685. The prediction model for the proportion of frying oil shows a strong prediction trend, with a prediction error of 0.3685. The range of variation for the target variable is 0–100, with an average value of 50. Compared to 50, 0.3685 accounts for a relatively small proportion; therefore, the root mean square error of 0.3685 is relatively low. The difference between the predicted and actual values of frying oil concentration is small, and the model has high prediction accuracy, which can reflect the true situation of frying oil concentration.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Identification of Adulterated Edible Oil

In the establishment of the adulterated edible oil judgment model, 120 pure edible oil samples and 120 adulterated edible oil samples measured experimentally were used, totaling 240 samples. The 3D FS of 240 samples were measured. Perform QsPCA, QqPCA, and QmPCA on 240 samples to obtain a QPCA graph. The results show that QsPCA and QqPCA can effectively distinguish between edible oil and frying oil. The QmPCA can basically distinguish between edible oil and frying oil. The extraction of quaternion features through summation can be achieved by using fewer quaternion principal components for differentiation.

When selecting fluorescence spectrum data at excitation wavelengths of 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm, the data obtained by summation quaternion feature extraction can be used as inputs for KNN, PSO-SVM, and GA-SVM, all of which can achieve 100% accuracy. The algorithm that uses the least quaternion principal component is the PSO-SVM algorithm. Only the first three quaternion principal component features need to be selected as inputs for PSO-SVM to establish a detection model for adulterated edible oil. The classification accuracy of the model can reach 100%.

4.2. Quantitative Model for Frying Oil

The experiment obtained 40 edible oil samples doped with 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% frying oil, for a total of 240 samples. Select fluorescence spectral data at excitation wavelengths of 360 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm as inputs for PLSR, PSO-SVR, and PSO-LSSVR, respectively, to establish a quantitative model for the proportion of frying oil in adulterated edible oil. The results show that the detection effect of frying oil concentration in adulterated edible oil based on PSO-LSSVR was the best, and the correlation coefficient of the test set reached 0.9663, proving that the correlation coefficient between the predicted value and the true value of the model reached 0.9663, and the root mean square error is 0.3685.

4.3. Prospect

This article presents a novel identification and quantitative detection framework for detecting adulterated edible oils and frying oils efficiently. Nonetheless, the efficacy of the quantitative detection model for frying oil is suboptimal. Future efforts should explore alternative quantitative analysis approaches or data selection from diverse spectral ranges to develop a more robust quantitative detection model for frying oil, aiming to attain a correlation coefficient of 0.99 or above in the test set, alongside minimizing the root mean square error. Subsequent research should focus on mitigating the risk of model overfitting and bolstering model stability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14020390/s1, Formulas (S1)–(S10): Quaternion Principal Component Analysis; Formulas (S11)–(S22): LSSVR; Formulas (S23) and (S24): PSO.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-Y.W. and A.-L.T.; methodology, S.-Y.W. and A.-L.T.; software, S.-Y.W. and Q.-Y.L.; validation, S.-Y.W. and Q.-Y.L.; formal analysis, S.-Y.W.; investigation, S.-Y.W.; resources, S.-Y.W. and A.-L.T.; data curation, S.-Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-Y.W.; writing—review and editing, S.-Y.W.; visualization, S.-Y.W.; supervision, L.L. and A.-L.T.; project administration, S.-Y.W.; funding acquisition, S.-Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Qinhuangdao Science and Technology Research and Development Plan Project [grant number: 202501A220]; Hebei University of Environmental Engineering [grant number: XJXM-YB-2024002].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, H.; Ren, R.; Jin, Q.; Gong, L.; Zhang, L.; Xue, M.; Fan, J.; Wang, S. Occurrence of EU-priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in edible oils and associated with human health risks in Hangzhou city of China. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 145, 107834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Jin, Z.; Amorati, R.; Shi, L. Effect of fatty acid composition on rosemary antioxidants in stabilizing woody edible oils: A kinetic and machine learning analysis of volatiles under accelerated oxidation. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lian, Y.; Xu, Q.; Li, J.; Xu, Z. A new ecological underground group tank with inner steel plate lining for edible oil: Full-scale test and numerical simulation. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2025, 19, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Gani, A.; Muzaifa, M.; Heriansyah, M.B.; Desvita, H.; Kamaruzzaman, S.; Sauqi, A.; Ardiansa, D. Edible Coating Combining Liquid Smoke from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches and Turmeric Extract to Prolong the Shelf Life of Mackerel. Foods 2025, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Jia, D.; Zhan, S.; Huang, S.; Jin, Y.; Duan, H. Tribological performance and lubrication mechanism of phosphate nanoflowers as oil-based additives. Friction 2025, 13, 9440924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L.C.; Neves, K.O.; Monaretto, T.; Costa, L.A.M.A.; Colnago, L.A.; Santos, A.D.C.; Machado, M.B. Determination of adulterants in copaiba Oil-Resin using 1H NMR. Microchem. J. 2025, 213, 113732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Han, Y.Z.; Li, Y.X.; Wang, S.Z.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, J.Y. Triglyceride fingerprint construction and adulteration identification of Qinghai flaxseed oil. China Oil Fats 2022, 47, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghili, N.S.; Rasekh, M.; Karami, H.; Edriss, O.; Wilson, A.D.; Ramos, J. Aromatic Fingerprints: VOC Analysis with E-Nose and GC-MS for Rapid Detection of Adulteration in Sesame Oil. Sensors 2023, 23, 6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shang, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Combined with AWRCQLD to Measure Three Additives in Cosmetics. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2020, 40, 501–505. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Yuan, J.; Wu, Q.; Liu, X.; Cui, J.; Xuan, H. Rapid Identification of Corn Sugar Syrup Adulteration in Wolfberry Honey Based on Fluorescence Spectroscopy Coupled with Chemometrics. Foods 2023, 12, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Huang, M. Quantitative Research on Hazelnut Oil Adulteration Based on Laser Raman Spectroscopy. Prog. Laser Optoelectron. 2024, 61, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Y.L.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Yang, X.T.; Zeng-li, W.; Liu, H. Potentiality of Synchronous Fluorescence Technology for Identification of Pork Adulteration in Beef. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2024, 44, 2968–2972. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Wei, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Jiao, Y. Using three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy and machine learning for rapid detection of adulteration in camellia oil. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 329, 125524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.Y.; Cui, Y.Y.; Jia, Y.G.; Chen, Z.P. Identification of Adulterated Edible Oils Based on 3D Fluorescence Spectroscopy Combined with 2D-LDA. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2024, 44, 3179–3185. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N.J.; Cheng, Z.; Yin, G.F. Rapid measurement of phytoplankton community structure by discrete three dimensional fluorescence spectrscopy. J. Atmos. Environ. Opt. 2020, 15, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Masson, H. Dynamic functional adaptations during touch observation in autism: Connectivity strength is linked to attitudes towards social touch and social responsiveness. Mol. Autism 2025, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Tan, Z.; Chen, Q.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J. Unified Frequency-Assisted Transformer Framework for Detecting and Grounding Multi-modal Manipulation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2025, 133, 1392–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Deng, R.; Xu, B.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, C.; Fan, L.; Lv, X.; et al. Deep Learning-Based Surrogate-Assisted Intelligent Optimization Framework for Reservoir Production Schemes. Nat. Resour. Res. 2025, 34, 1701–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S. Quaternion Information Filters with Inaccurate Measurement Noise Covariance: A Variational Bayesian Method. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2025, 73, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, P.; Chen, L.; Mou, J. Collaborative Collision Avoidance Approach for USVs Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 4780–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, G.Z.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, L.; Yin, Z.P. The quaternion beam model for hard-magnetic flexible cantilevers. Appl. Math. Mech. 2023, 44, 787–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviz, L.; Ghorbanpour, M. Assimilation of PSO and SVR into an improved ARIMA model for monthly precipitation forecasting. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, W.; Lee, D.K. VIS-NIR spectroscopy and environmental factors coupled with PLSR models to predict soil organic carbon and nitrogen. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, Z.; Pan, C.; Xue, H. Detection of Al, Mg, Ca, and Zn in copper slag by LIBS combined with calibration curve and PLSR methods. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2024, 26, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spišáková, D.; Kožárová, I.; Hriciková, S.; Marcinčák, S. Comprehensive Screening of Salinomycin in Feed and Its Residues in Poultry Tissues Using Microbial Inhibition Tests Coupled to Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). Foods 2024, 13, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.; Zhao, Y.; Sivashanmugan, K.; Squire, K.; Wang, A.X. Quantitative TLC-SERS detection of histamine in seafood with supportvector machine analysis. Food Control 2019, 103, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennai, M.Y.; Tedjini, H.; Nasri, A. Comparative Assessment of P&O, PSO Sliding Mode, and PSO-ANFIS Controller MPPT for Microgrid Dynamics. Elektron. Elektrotechnika 2024, 30, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Tian, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, W. Detection of Internal Wire Broken in Mining Wire Ropes Based on WOA-VMD and PSO-LSSVM Algorithms. Axioms 2023, 12, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepp, R.G.; Sheldon, W.M.; Moran, M.A. Dissolved organic fluorophores in southeastern US coastal waters: Correction method for eliminating Rayleigh and Raman scattering peaks in excitation-emission matrices. Mar. Chem. 2004, 89, 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, L.H.; Sirakov, N.M.; Luong, M.; Viennet, E.; Le-Tien, T. Image Classification Based on Sparse Representation in the Quaternion Wavelet Domain. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 31548–31560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-R.; Li, W.-J.; Huang, S.-M. Quaternion-based machine learning on topological quantum systems. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2023, 4, 015032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Qiu, Y. Color Occlusion Face Recognition Method Based on Quaternion Non-Convex Sparse Constraint Mechanism. Sensors 2022, 22, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Hosseini, S.; Gordan, B.; Zhou, J.; Ullah, S. Dimensionless Machine Learning: Dimensional Analysis to Improve LSSVM and ANN models and predict bearing capacity of circular foundations. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-L.; Zhang, B.-X.; Xu, J.-H.; Chen, Z.-L.; Zheng, X.-Y.; Zhu, K.-Q.; Xie, H.; Bo, Z.; Yang, Y.-R.; Wang, X.-D. Fault diagnosis and removal for hybrid power generation systems based on an ensemble deep learning diagnostic method with self-healing strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafti, A.A.; Rezaei, M. Advancing renewable energy scenarios with graph theory and ensemble meta-optimized approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 218, 115806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.