Abstract

Late-stage sandstone reservoirs often exhibit flow behavior markedly different from early performance, reducing recovery. This study quantifies two-phase flow in Jilin Oilfield sandstone cores to support production optimization. An oil–water displacement apparatus was built and unsteady-state relative-permeability tests were performed on core plugs from multiple well blocks. Permeability, pressure gradient, water saturation, and displacement efficiency were tracked over a range of injection multiples. Water-phase relative-permeability curves classify three seepage types: concave-down (12 cores, 2.10–46.17 mD), linear (7 cores, 1.58–12.23 mD), and concave-up (3 cores, 8.74–30.73 mD). Permeability is strongly negatively correlated with irreducible water saturation (R2 = 0.84) and positively correlated with residual oil saturation (R2 = 0.58), two-phase flow interval (R2 = 0.51), and movable oil saturation (R2 = 0.89); other relationships are weak. An increasing pressure gradient markedly improves displacement efficiency in low-permeability cores. Higher injection multiples further raise displacement efficiency across all permeability classes, but gains diminish with increasing permeability. Displacement efficiency also increases with water cut when used as a flooding-stage indicator in these unsteady-state tests.

1. Introduction

Relative permeability curves play a crucial role in oil and gas reservoir development. These curves describe the flow behavior of oil and water as a function of water saturation, reflecting the combined effects of reservoir pore structure, fluid properties, and operating conditions [1,2,3]. Current methods for measuring oil–water relative permeability are generally categorized as steady-state or unsteady-state approaches. The steady-state method does not capture transient variations in saturation. In contrast, the unsteady-state method is based on the Buckley–Leverett theory for one-dimensional, two-phase displacement. It simulates the advance of the waterflood front, providing insight into displacement dynamics and enabling more accurate predictions of oil production and residual oil distribution during water injection processes [4,5,6,7,8]. Numerous studies have utilized this theory to develop mathematical models for polymer flooding in heterogeneous reservoirs and to derive analytical expressions for displacement performance in one-dimensional systems [9,10,11,12,13]. Consequently, the Buckley–Leverett-based unsteady-state method has become a fundamental approach for estimating relative permeability curves and is widely used in reservoir engineering research.

Relative permeability curves are influenced by reservoir permeability, pore connectivity, clay mineral content, wettability, and operational conditions (e.g., pressure gradient and injected pore volume). Here, the water injection multiple (PV) is defined as the cumulative injected water volume normalized by the core pore volume: PV = Vw,inj/Vp. In field practice, water cut is a macroscopic production indicator reflecting the evolution of saturation and flow pathways during waterflooding, rather than a direct microscopic control variable. During reservoir development, operational adjustments affect displacement efficiency and the distribution of remaining oil, thereby altering the evolution of relative permeability curves [14,15]. Deng et al. [16] proposed a Type-C waterflood-curve fitting method based on relative permeability curves, using linear regression to relate cumulative water injection to oil production. This approach indirectly estimates oil saturation and relative permeability but neglects threshold pressure gradients. Wang et al. [17] developed an empirical formula by fitting the relationship between relative permeability and water saturation; however, its applicability under high water cut or complex fluid conditions has not been validated. Ma et al. [18] introduced a method for calculating relative permeability in low-permeability, low-viscosity reservoirs using Type-D waterflood curves and validated its feasibility via regression analysis. Nonetheless, they did not address the long-term impact of reservoir heterogeneity on relative permeability evolution. Overall, most studies have used regression analysis involving relative permeability curves to explore correlations between oil saturation, water saturation, and associated parameters. However, these studies typically focus on isolated variables, leaving the coupled effects of multiple interacting factors insufficiently investigated.

The JBN method is widely employed to estimate oil–water relative permeability. Although computationally intensive, it uses finite-difference or graphical methods to process discrete data, enabling the estimation of relative permeability and effluent water saturation [19,20]. A key advantage of the JBN method is its ability to accurately characterize trends in oil–water flow behavior, even under heterogeneous and complex core conditions. Peng et al. [21] applied the JBN algorithm to smooth and correct experimental relative permeability curves, enhancing their representation of flow dynamics. Zhao et al. [22] incorporated an apparent threshold pressure gradient into the JBN method, yielding curves that more accurately reflect flow characteristics in low-permeability reservoirs. Xu et al. [23] modified the JBN method to improve gas–water relative permeability curves in tight sandstone gas reservoirs, achieving higher accuracy and better applicability to field-scale development. These examples highlight the JBN method’s advantages in estimating accurate and reliable relative permeability curves compared with conventional approaches.

In this study, an oil–water core displacement system was designed and constructed, and two-phase dynamic displacement experiments were conducted on reservoir cores from the Jilin Oilfield. Unsteady-state relative permeability testing was applied to systematically investigate reservoir types with varying flow characteristics and the associated controlling factors. Core samples were taken from both early production wells and infill wells drilled during the later stages of field development. To ensure that the infill-well cores represent late-stage waterflooded conditions rather than an undisturbed early state, the cored intervals were selected from zones interpreted as waterflooded or water-washed based on integrated field evidence (e.g., logging-based waterflood interpretation and the injection–production history of the corresponding well blocks). To ensure depositional comparability, the early-stage and late-stage cores were constrained to the same reservoir interval and to the same or stratigraphically correlated layers (Table 1 and Table 2). The former reflected initial fluid dynamics, whereas the latter captured the impact of high-pressure water injection and time-dependent reservoir evolution. Experiments on these representative samples revealed the influence of permeability on the shape and behavior of oil–water relative permeability curves across different development stages. In addition, the effects of permeability, pressure gradient, and other operational and reservoir parameters on displacement efficiency were analyzed. The findings provide theoretical insights and technical support for optimizing injection–production strategies and improving reservoir performance.

Table 1.

Unsteady-state oil–water two-phase relative permeability curve experimental core basic physical property table (early stage of development).

Table 2.

Oil–water two-phase relative permeability curve experimental core basic physical property table of the unsteady state method (later encryption).

To clarify how this work advances prior studies, the main contributions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Stage-resolved and stratigraphically comparable dataset: Early-stage cores and late-stage infill cores were collected from the same reservoir interval and overlapping or stratigraphically correlated layers, and the infill cored intervals were screened as waterflood-affected zones using integrated field evidence (logging-based interpretation and injection–production history), thereby improving representativeness for stage-wise comparisons.

- (2)

- Unified unsteady-state JBN workflow with quantitative descriptors: Unsteady-state tests were processed using a consistent JBN procedure, and key characteristic parameters (e.g, Swir,Sw(Sor), two-phase flow interval, movable-oil saturation, and krw(Sor)) were quantified to enable systematic cross-core comparisons.

- (3)

- Curve-type classification linked to mechanisms: Water-phase curve geometries were classified into concave-up, linear, or concave-down seepage types, and their differences were interpreted within a pore-scale connectivity–heterogeneity framework.

- (4)

- Operational sensitivity analysis with clarified causality: The impacts of pressure gradient and injected pore volume on displacement efficiency were evaluated; additionally, water cut was treated as a flooding-stage indicator rather than a direct microscopic control factor to avoid causal misinterpretation.

- (5)

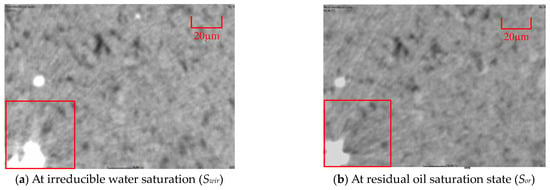

- Micro-CT used as qualitative structural support: Raw grayscale micro-CT slices (without phase segmentation) were incorporated as qualitative evidence of pore connectivity and preferential flow pathways, supporting the proposed mechanistic interpretations.

2. Experimental Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Material

Core samples for the experiments were collected from the Jilin Oilfield in China at depths of approximately 1180–1330 m. The reservoir permeability ranged from 0.8 to 49.9 mD, while porosity varied between 7.34% and 20.73%. The reservoir is classified as a low-permeability sandstone with a high proportion of high-quality sand. The cores exhibit contact–pore cementation and contain 16.9% clay cement and 4.4% carbonate cement. To meet the research objectives, core samples were selected from six wells drilled during the early development phase and from three infill wells drilled during later stages. In addition, to minimize the influence of depositional microfacies differences, the early-stage and late-stage cores were selected from the same reservoir interval and from overlapping or stratigraphically correlated layers. Specifically, Layers 8 and 26 are included in both datasets, and the Layer 13–14 interval is matched between the early-stage combined “13 + 14” layer and late-stage Layers 13 and 14 (Table 1 and Table 2). The representativeness of the late-stage (infill) cores was verified by screening the cored intervals for waterflooded or water-washed characteristics. Specifically, the target intervals in the infill wells are located within mature injection–production patterns and have experienced long-term water injection in the corresponding blocks. The waterflooded state of the cored intervals was evaluated using conventional logging interpretation (e.g., an apparent reduction in resistivity and increased interpreted water saturation relative to the early-stage baseline) together with dynamic field information (e.g., sustained high water cut or strong injection support in surrounding wells). Therefore, the infill-well cores used in this study are considered to represent late-stage waterflood-affected reservoir conditions for comparative analysis. A total of 11 core samples from each phase were tested. Detailed physical properties of the core samples are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. Prior to testing, all core samples underwent standardized pre-treatment procedures, including the following steps:

- (1)

- Cores were cleaned for 48 h using Soxhlet extraction with a toluene–ethanol mixture (3:1 by volume) to remove residual oil and organic matter.

- (2)

- The cleaned cores were oven-dried at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved (mass variation < 0.1%).

- (3)

- Porosity was re-measured using a helium porosimeter, with deviations from the original data controlled within 2%.

- (4)

- Cores were placed in a vacuum saturation device, evacuated to −0.1 MPa for 4 h, and then fully saturated with simulated formation water.

2.2. Experimental Principles and Algorithm Procedures

In this study, oil–water relative permeability was measured using an unsteady-state method following the procedure proposed by He Yue [24]. The technique is based on Buckley–Leverett one-dimensional two-phase flow theory and employs waterflooding tests conducted at either a constant pressure differential or a constant flow rate. The JBN unsteady-state method is suitable here because it derives effective oil–water relative permeability from measured production history and differential pressure under controlled waterflooding, enabling consistent comparisons among cores. In low-permeability rocks, a threshold (start-up/non-Darcy) pressure gradient may occur at very low flow velocities; therefore, the displacement conditions (constant ΔP or constant rate; Table 2, Remark A) were selected to maintain stable, measurable flow. The resulting curves are interpreted as effective relative permeability representative of injection-driven pressure gradients, whereas ultra-low-gradient start-up effects are deferred to future low-velocity tests. Fluid production and the corresponding outlet pressure differential were recorded simultaneously. After each test, the data were processed with the JBN method to construct relative permeability curves and to examine the relationship between the flow rate and pressure response. In addition, to quantify macroscopic sweep (flushing) performance during displacement, the flushing efficiency was calculated as follows:

where is the cumulative produced water volume; and is the cumulative injected water volume.

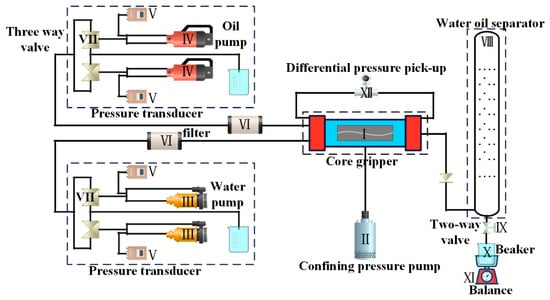

The main apparatus and workflow are shown in Figure 1. The experimental system comprised a core holder, an injection pump (constant-rate or constant-ΔP mode), a confining-pressure pump, a differential-pressure transducer, an electronic balance, inline filters, and an oil–water separator; key instrument ranges and accuracies are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1.

The experimental equipment and flow diagram for measuring the relative permeability of the oil–water two-phase by the unsteady state method.

Table 3.

Key instruments and specifications for the unsteady-state coreflood setup.

Experimental oil was prepared by mixing refined white oil and neutral kerosene at a 3:1 volume ratio, yielding a blend viscosity of 13.0 mPa·s at 22 °C, as listed in Table 4. The blend viscosity was measured using a rotational viscometer at 22 °C. This mixed oil was formulated to match the laboratory “dead-oil” viscosity of the target Jilin Oilfield reservoir, thereby providing a representative oil–water viscosity ratio for the oil–water displacement tests. All displacement experiments were conducted at a constant, well-controlled laboratory temperature (22 °C) to minimize viscosity fluctuations and ensure comparability across core tests. Although the formation temperature exceeds the laboratory temperature, the unsteady-state relative-permeability evaluation in this work focuses on relative two-phase flow behavior among cores under a consistent, viscosity-controlled condition, which remains appropriate for comparative analysis. Synthetic formation water was formulated according to the ionic composition of the Jilin Oilfield. Its salinity was 4700 mg/L, with Na+ and K+ 1520 mg/L, Ca2+ 680 mg/L, Mg2+ 240 mg/L, Cl− 2260 mg/L, and a pH of 7.2.

Table 4.

Properties of experimental fluids at 22 °C.

Prior to use, the oil and brine were passed through 0.22 µm microporous membranes to remove suspended solids. The brine was then settled for at least 24 h, filtered through a G5 sintered-glass funnel, and degassed to ensure sample purity and data reliability. In addition, micro-CT scanning was conducted on representative cores at two characteristic flooding stages to provide pore-scale evidence for interpreting relative-permeability curve types. Specifically, CT slices were acquired at the irreducible-water state (Swir) and at the late-time state approaching residual oil saturation (Sor). During scanning, the flooding was paused and the core was sealed to minimize fluid redistribution.

Bound water saturation was determined through simulated oil-displacement experiments. The experiment began with a low displacement rate of 0.05 mL/min. The flow rate was then adjusted based on the permeability class of each core sample. As the test progressed, the injection rate was gradually increased. Once the water cut exceeded 90%, the injection rate was increased from 0.5 to 1.0 mL/min to shorten the experimental duration and drive the displacement to a stable late-time condition approaching residual oil saturation (Sor). This rate adjustment was applied uniformly to all cores as an operational step; it was not intended to simulate late-stage reservoirs. The relative-permeability curves used for comparative analysis were obtained under the same displacement protocol, and the late-time high-rate flushing was used only to stabilize the endpoint. Water injection continued until no additional water was produced from the core. Bound water saturation was calculated using Equation (1):

Equation (2):

where is Irreducible (bound) water saturation, %; is Pore volume, cm3; and is Volume of water displaced from the core, cm3.

Equation (3):

where is Effective permeability to oil at irreducible water saturation, mD; is Oil flow rate, mL/s; is Oil viscosity at the test temperature, mPa·s; is Core length, cm; A is Cross-sectional area of the core, cm2; is Inlet pressure of the core, MPa; and is Outlet pressure of the core, MPa.

Equations (4)–(8):

where is Oil saturation at the outlet end of the core holder; is Dimensionless cumulative oil production; is Dimensionless cumulative water injection; is Oil relative permeability at the inlet under varying saturation levels; is Water relative permeability at the inlet under varying saturation levels; is Water viscosity; is Oil viscosity; is Water saturation at the outlet and bound water saturation of the core, respectively; is Mobility ratio at time t compared to the initial state; is Liquid production rate at the outlet at time t, in cm3/s; is Initial liquid production rate at the outlet, in cm3/s; is Initial pressure differential across the core, in MPa; and is Pressure differential across the core at time t, in MPa.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Experimental Results for Oil–Water Two-Phase Relative Permeability Curves

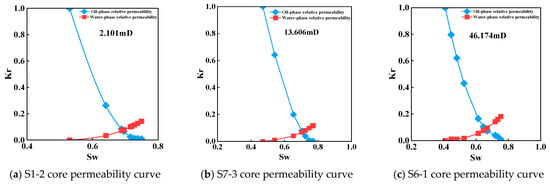

A total of 22 core samples spanning a wide permeability range were selected from both newly developed and mature blocks in the Jilin Oilfield. Oil–water relative permeability tests were performed on these cores using the unsteady-state method. Based on curve geometry, the results were classified into three types: concave-up water-phase curves, approximately linear curves, and concave-down water-phase curves. Among these, 12 cores exhibited concave-up water-phase behavior. Figure 2 presents three representative relative permeability curves for cores with permeabilities of 2.101, 13.606, and 46.174 mD. This curve type exhibits distinct features: at early times, increasing water saturation leads to a decrease in oil-phase relative permeability, accompanied by an increase in water-phase relative permeability. At later times, the decline in oil-phase relative permeability slows, whereas the increase in water-phase relative permeability becomes more pronounced.

Figure 2.

Core oil-water two-phase relative permeability curve.

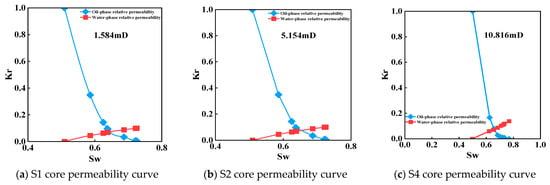

The second type is characterized by an approximately linear water-phase curve and comprises seven core samples, with permeabilities ranging from 1.584 to 12.225 mD. Figure 3 shows three representative cores of this type. A defining feature of this curve type is the steady increase in water-phase relative permeability as water saturation increases. The average clay mineral composition is as follows: 18.22% montmorillonite, 32.81% illite, 22.73% kaolinite, and 26.26% chlorite. These reservoirs typically contain substantial amounts of clay minerals, which swell upon contact with water, thereby significantly reducing core permeability. Swelling clay obstructs flow channels within pore spaces, thereby retarding the increase in water-phase relative permeability. Moreover, uneven clay swelling can lead to spatially heterogeneous permeability distributions, further reducing oil displacement efficiency.

Figure 3.

Oil–water two-phase relative permeability curve of water-phase linear core.

The third type is characterized by a concave-down water-phase curve and includes three core samples with permeabilities of 8.735, 21.391, and 30.733 mD, as shown in Figure 4. Unlike the linear type, this curve exhibits a decreasing rate of increase in water-phase relative permeability as water saturation rises. The average clay mineral composition is 26.97% montmorillonite, 33.26% illite, 19.56% kaolinite, and 20.21% chlorite. These reservoirs typically contain higher clay contents, which can cause clay-sensitivity damage upon contact with water, leading to reduced rock permeability during waterflooding. Clay swelling or the release of soluble components may cause mud plugging, thereby reducing effective pore connectivity and significantly hindering the development of water-phase relative permeability. Clay sensitivity impairs reservoir flow capacity, exacerbates uneven fluid distribution and pore blockage during oil displacement, and ultimately reduces waterflooding efficiency.

Figure 4.

Oil–water two-phase relative permeability curve of concave water phase core.

In summary, linear and concave-down water-phase curves are relatively rare and mainly arise from reservoir heterogeneity and complex fluid behavior during waterflooding. The Jilin reservoir displays marked heterogeneity, which leads to highly nonuniform flow patterns during water injection. Note that the CT images in this study are raw grayscale micro-CT slices acquired without contrast-enhanced fluids or phase segmentation; therefore, oil and water phases cannot be reliably distinguished from grayscale intensity alone. Here, micro-CT is used as qualitative structural evidence to characterize pore heterogeneity and connectivity (e.g., preferential pathways and potential trapping features), supporting the mechanistic interpretation of the observed relative-permeability curve types. The CT images presented in Figure 5 are raw grayscale slices (scale bar: 20 μm) and are used primarily to qualitatively assess pore-structure heterogeneity and pore-space connectivity (e.g., preferential pathways and local high-conductivity features).Figure 5 presents representative raw grayscale micro-CT slices acquired at two characteristic stages: (a) the irreducible-water state (Swir) after oil flooding and (b) the late-time state approaching residual oil saturation (Sor) after water-flooding. Because contrast-enhanced fluids were not used and phase segmentation was not performed, the oil and water phases cannot be distinguished directly from grayscale intensity; accordingly, the overall pore framework appears similar in both panels. The purpose of Figure 5 is to provide qualitative structural evidence of connectivity and heterogeneity to support the interpretation of the observed relative-permeability behaviors. Specifically, the red region of interest (ROI) highlights a connected pore-throat network that is expected to serve as a preferential flow pathway during flooding, whereas the surrounding finer and more tortuous regions are prone to bypassing and late-time trapping. Thus, the apparent difference between (a) and (b) should be understood as a change in phase occupancy (water progressively establishing a spanning pathway while oil becomes increasingly disconnected and trapped in smaller pores/throats), rather than a change in pore geometry. This qualitative interpretation is consistent with the observed evolution of kro and kwir in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 and the stage-wise endpoint contrasts summarized in Table 5 and Table 6. In the early stage, the injected water first invades larger pore channels because of their higher permeability, causing a rapid rise in water-phase relative permeability and relatively smooth flow. As the injected pore volume increases, water starts to penetrate progressively smaller pores. The lower permeability of these pores increases flow resistance and the pressure drop across the core. In later stages, the injected water fills most pore channels and displaces the oil phase, which becomes increasingly restricted and eventually breaks into small droplets. While flowing, these droplets experience increasing resistance, especially at pore throats, where they are susceptible to the Jamin effect. The Jamin effect arises when the droplet size approaches the throat diameter, preventing passage through narrow constrictions and impeding flow. Under these conditions, oil–water flow becomes increasingly difficult, and the recovery factor may decline sharply. The combined action of these processes slows the increase in water-phase relative permeability at late times and, in some cases, produces a concave-down curve.

Figure 5.

Representative raw grayscale micro-CT slices at two flooding stages (red box: ROI; scale bar: 20 μm), illustrating pore connectivity and heterogeneity relevant to preferential flow and trapping. Note: Oil and water phases are not explicitly segmented in these grayscale slices; differences are interpreted mainly in terms of phase occupancy at Swir and near Sor.

Table 5.

Characteristic parameters of core relative permeability curve in the early stage of development.

Table 6.

Late infill well core relative permeability curve characteristic parameters.

A stage-wise comparison of relative-permeability characteristics is provided below. Although the curve geometries can be grouped into three seepage types, the early-stage and late-stage (infill) cores show systematic differences in endpoint values and interval metrics. As summarized in Table 3 and Table 4, the late-stage cores exhibit a slightly lower irreducible water saturation (mean Swir = 46.72%) than the early-stage cores (mean Swir = 47.45%), indicating a modest reduction in bound-water dominance under late-stage conditions. Meanwhile, the water-phase relative permeability at the late-time endpoint is higher for the late-stage cores (mean krw(Sor) = 0.1436) than for the early-stage cores (mean krw(Sor) = 0.1341), suggesting more effective water-phase connectivity and a greater tendency for water to become the dominant flowing phase at high water saturation. In addition, the late-stage cores show a lower Sw(Sor) (mean 75.31%) than the early-stage cores (mean 77.58%), implying a slightly higher residual oil level at a later time, which is consistent with the coexistence of preferential flow paths and bypassed or poorly connected pore regions in mature waterflood blocks. These stage-wise contrasts motivate the comparative analysis presented in Section 3.2 and the factor analysis in Section 4.

3.2. Analysis of Fluid Flow Characteristics and Patterns in Core Samples with Different Permeabilities

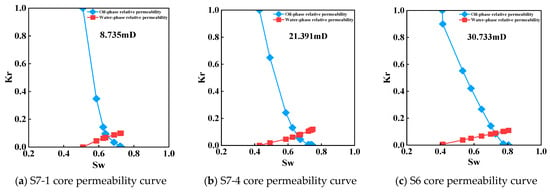

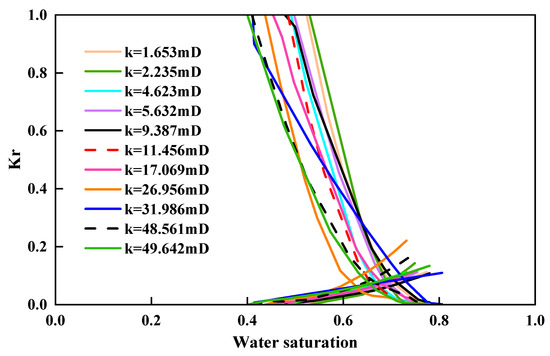

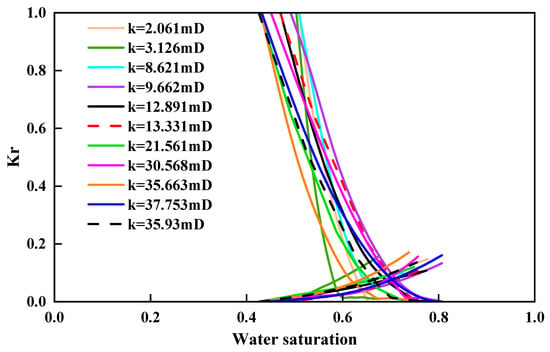

Representative core samples spanning a range of permeabilities were selected from early-stage wells and from late-stage infill wells whose cored intervals were screened as waterflood-affected zones (Section 2.1) for relative-permeability testing. The subsequent analysis focuses on comparing the oil–water relative-permeability behaviors of cores from the early and late stages under comparable experimental boundary conditions. Based on the experimental results, comparative relative permeability curves for the early development and infill-well stages were constructed, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 6.

The curve of relative permeability of the core with saturation at the initial stage of development.

Figure 7.

The curve of relative permeability of infilled core with saturation in the later stage.

The stage-wise differences in relative-permeability behavior have direct implications for production and waterflood management. For early-stage cores, the relatively higher oil mobility at moderate water saturation and the weaker water-phase dominance at the endpoint indicate that improving sweep efficiency (e.g., maintaining a sufficient pressure gradient above the effective threshold in tight cores) can yield meaningful incremental recovery. For late-stage infill cores, the higher krw(Sor) and the stronger sensitivity of endpoints to permeability suggest that water tends to preferentially occupy high-conductivity pathways, leaving bypassed oil in tighter pore systems. Therefore, late-stage development should place greater emphasis on conformance control and selective injection/production adjustments (e.g., profile modification, zonal injection optimization, and water shutoff or plugging of dominant channels) rather than simply increasing injected volume. These insights provide more actionable guidance beyond curve-type classification.

Figure 6 shows that the oil–water relative permeability curves for early-stage cores depend strongly on permeability. As permeability increases, the oil-phase curves shift markedly leftward. Their shapes and slopes remain nearly unchanged, implying a primarily horizontal translation. Thus, higher-permeability cores impose less internal resistance to oil flow. At low water saturation, the oil phase attains high relative permeability more readily than the water phase. Conversely, the endpoints of the water-phase curves vary little in water saturation, indicating that permeability has limited influence on water flow at high saturation. At high saturation, the water phase occupies the main flow channels, reducing the role of permeability in water transport and stabilizing the curve endpoints. Nevertheless, permeability differences still exert a minor effect on water flow at high saturation, producing small shifts in endpoint saturation. Overall, increased permeability enhances oil-phase flow mainly during early displacement, whereas its impact on two-phase dynamics weakens as water saturation rises.

Figure 7 shows that the relative permeability curves from late-stage infill wells exhibit a stronger dependence on permeability. As permeability increases, the slope of the oil-phase curve progressively decreases, especially at high water saturation. This trend indicates that high-permeability cores offer lower resistance to oil flow in late displacement, thereby preserving oil mobility. Conversely, water-phase curves display more complex behavior as permeability increases. Although initial water saturation points vary slightly, endpoint saturation values shift noticeably as permeability increases. In high-permeability cores, water increasingly occupies the main flow channels at high saturation, displacing residual oil into smaller pores or trapping it, thereby affecting final water saturation.

Compared with the early-stage cores (Figure 6), the late-stage infill cores (Figure 7) show stronger permeability sensitivity not only in the oil-phase curve shape (progressive slope reduction at high water saturation) but also in the water-phase endpoints (more evident shifts in endpoint saturation). Consistent with Table 3 and Table 4, late-stage cores exhibit a slightly lower mean Swir (46.72% vs. 47.45%) but a higher mean krw(Sor) (0.1436 vs. 0.1341) and a lower mean Sw(Sor) (75.31% vs. 77.58%) than the early-stage cores, indicating that water more readily becomes the dominant connected phase at a late time while residual oil remains trapped in tighter or poorly connected pore regions. Therefore, the stage-dependent differences are not limited to curve-type appearance; they reflect a maturity-enhanced tendency toward preferential flow and bypassing, which helps explain why late-stage development should prioritize conformance control and selective injection/production adjustments rather than relying solely on increased injected volume.

4. Controlling Factors of Relative-Permeability Behavior and Displacement Efficiency

4.1. Impact of Permeability on Oil Displacement Efficiency

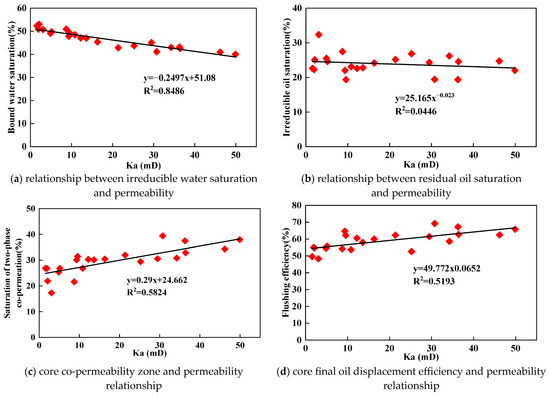

After the experiments, the characteristic parameters in Table 5 and Table 6 were analyzed. The results reveal a strong linear correlation between permeability and irreducible water saturation; lower permeability corresponds to higher irreducible water saturation. Irreducible water saturation typically ranges from 40% to 55%, with a mean of 47.09%. Notably, early-stage cores generally exhibit slightly higher irreducible water saturation than late-stage infill cores. Residual oil saturation tends to increase as permeability decreases, although this correlation is relatively weak. Water saturation at residual oil conditions typically ranges from 67% to 82%, with a mean of 76.44%. Moreover, residual oil saturation is usually higher in early-stage cores than in late-stage infill cores. Experimental results show that the width of the two-phase flow region is strongly correlated with permeability, with a narrower region observed at lower permeability. At lower permeabilities, the two-phase flow region narrows further, with saturation values between 16% and 40%, with a mean of approximately 30%. Comparatively, early-stage cores exhibit a slightly wider saturation range in the two-phase flow region than late-stage infill cores. Final oil recovery efficiency is generally high and strongly linked to permeability, ranging from 48% to 69%, with a mean of 59.26%. The displacement efficiency of early-stage cores is slightly lower than that of late-stage infill cores within this dataset. This difference should be interpreted with caution because it may reflect the combined effects of sampling representativeness and reservoir heterogeneity. From a pore-scale perspective, long-term waterflooding can modify the effective pore-throat network through processes such as clay mineral swelling/dispersion and fine-particle migration, which may change irreducible water saturation and phase connectivity and thereby alter relative permeability behavior. Therefore, in the following discussion, we emphasize the robust correlations between permeability-related parameters and displacement efficiency, whereas the early–infill comparison is used as a qualitative indication rather than a standalone causal conclusion.

4.1.1. Pore-Scale Interpretation of Curve-Type Differences and Development-Stage Effects

Permeability is fundamentally controlled by the pore–throat size distribution and connectivity (i.e., pore-network coordination). Cores with lower permeability generally have smaller dominant throat radii and poorer connectivity, leading to higher capillary entry resistance and a larger proportion of bound water, which is consistent with the observed negative correlation between permeability and irreducible water saturation. In such systems, water invasion during early displacement tends to be restricted to limited connected pathways (or corner/film flow), and the effective water-phase network expands gradually; once a spanning water network is formed, water-phase conductivity increases more rapidly, which can manifest as a concave-up water-phase relative-permeability trend.

In contrast, cores characterized by strong heterogeneity in pore connectivity (e.g., a small number of high-conductivity channels coexisting with abundant tight pores) are prone to early-time preferential channeling. In this case, water rapidly establishes continuous flow along the dominant channels, giving a rapid initial rise in water-phase relative permeability; however, subsequent invasion into tight throats contributes less to effective conductivity and can be hindered by pore-throat snap-off, intermittent droplet blockage (Jamin effect), and fine-particle plugging, leading to diminishing increments in water-phase conductivity and a concave-down trend. Linear-type curves are consistent with intermediate pore–throat contrasts, where the growth of connected water pathways is approximately proportional to increases in saturation.

Regarding development-stage differences (early vs. infill), long-term water injection may alter the effective pore–throat system through microscopic processes such as clay mineral swelling/dispersion and particle migration, which can modify bound-water volume and throat accessibility and thus shift relative-permeability characteristics. In the present work, micro-CT observations (Figure 5) provide qualitative evidence of pore-structure heterogeneity and preferential features; nevertheless, quantitative pore–throat statistics and clay-mineral occurrence characterization (e.g., SEM and XRD) are not included in the current dataset and will be incorporated in future work to further strengthen the mechanistic linkage.

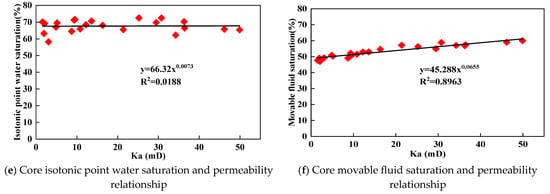

4.1.2. Quantitative Correlations Between Permeability and Relative-Permeability Characteristic Parameters

Figure 8 illustrates the relationships between experimentally determined relative-permeability parameters and permeability. The fitted exponent in the power-law forms used in Figure 8b,d is close to 1, indicating approximately linear scaling within the tested permeability range. The results show that movable oil saturation, two-phase flow region saturation, and irreducible water saturation strongly correlate with permeability, with correlation coefficients of 0.89, 0.58, and 0.84, respectively. In contrast, residual oil saturation and water saturation at the crossover point have weaker correlations with permeability. Given the low correlation (Figure 8e), this relationship is not used for prediction; instead, it indicates the absence of a robust permeability-dependent trend under the tested conditions. These correlations can be interpreted in terms of pore-scale controls. Permeability is governed by the effective pore–throat size distribution and connectivity. In tighter cores with narrower dominant throats and poorer connectivity, capillary entry resistance is higher and a larger fraction of water tends to remain bound, which is consistent with higher Swir and a delayed growth of krw. Conversely, in cores with stronger connectivity contrast (i.e., a few high-conductivity pathways coexisting with abundant tight pores), water can establish preferential flow paths earlier, leading to a faster initial rise in krw. However, further invasion into tighter throats contributes less to effective conductivity and may be accompanied by snap-off, Jamin-type local blockage, and bypassing, yielding diminishing incremental gains at a later time. Mineralogy- and clay-related processes may further modify the effective pore–throat system during long-term waterflooding. Given the non-negligible clay cement fraction in the studied cores (Table 1 and Table 2), clay swelling/dispersion and fine-particle migration at pore throats can plausibly reduce throat accessibility and alter phase connectivity, thereby affecting endpoint saturations and curve curvature. Wettability is another key control because it governs phase distribution in pore corners and throats, thereby shifting endpoints and crossover saturation. Although direct wettability and mineralogical measurements (e.g., contact-angle tests, SEM, and XRD) are not included in the present dataset, the mechanisms above provide a physically consistent explanation for the stage-dependent relative-permeability behaviors observed in this work; quantitative validation will be pursued in future work.

Figure 8.

Scatter plot of core oil–water two-phase relative permeability characteristic parameters and permeability change.

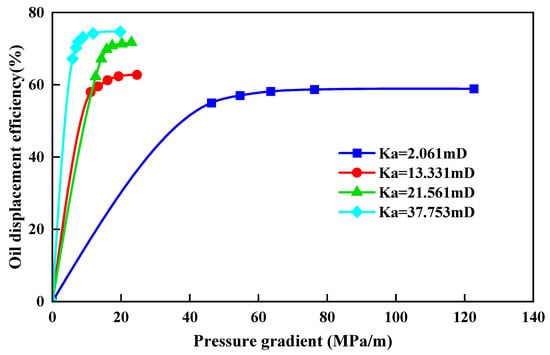

4.2. Impact of Pressure Gradient on Oil Displacement Efficiency

Figure 9 depicts how oil recovery efficiency varies with pressure gradient at different permeability levels. The critical pressures for the four core samples are 46.2, 11.1, 12.6, and 5.8 MPa, yielding oil recoveries of 55.0%, 57.9%, 62.3%, and 67.2%, respectively. During early displacement, low-permeability cores respond more sensitively to changes in the pressure gradient. A moderate increase in differential pressure markedly boosts oil recovery. As permeability rises, the incremental benefit of pressure diminishes. In high-permeability cores, additional pressure provides only marginal gains in oil recovery. Thus, applying a higher-pressure gradient is effective in low-permeability reservoirs, whereas merely increasing pressure has little impact on displacement efficiency in high-permeability reservoirs.

Figure 9.

The relationship between oil displacement efficiency and pressure gradient.

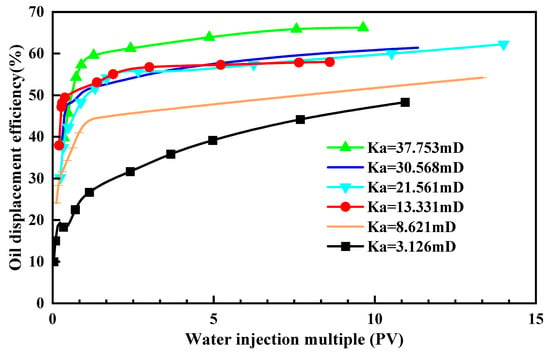

4.3. Impact of Injection Multiple on Oil Displacement Efficiency

Figure 10 shows that oil-recovery efficiency rises with injected pore volume (PV) but follows different trajectories as a function of permeability. At an injection level of 1 PV, all cores exhibit a sharp increase in recovery. When the injected volume reaches 3–4 PV, recovery in high-permeability cores slows or plateaus, whereas low-permeability cores continue to gain at a faster rate. At any given injection volume, higher-permeability cores still attain greater recovery than lower-permeability cores. The efficiency of water utilization also changes with the displacement stage: in the early stage, roughly 80% of the ultimate oil is produced within the first 1 PV, whereas by the high water-cut stage, additional injection yields little incremental recovery.

Figure 10.

The relationship between oil displacement efficiency and injection multiple.

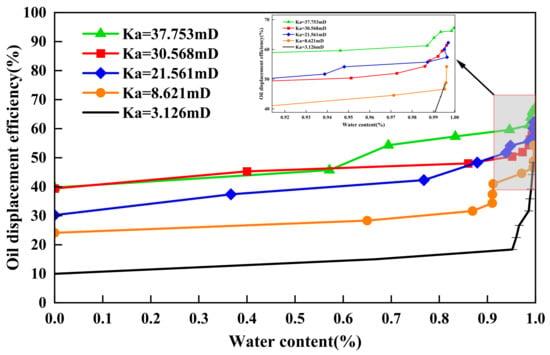

4.4. Relationship Between Water Cut (As a Flooding-Stage Indicator) and Displacement Efficiency

Figure 11 presents the relationship between oil displacement efficiency and water cut as displacement progresses. It should be noted that water cut is not a direct microscopic control factor for displacement efficiency; instead, it is a macroscopic indicator reflecting the evolution of saturation and preferential flow pathways during waterflooding. The observed increase in displacement efficiency with rising water cut therefore represents an integrated outcome of pore–throat connectivity, heterogeneity, and rock–fluid interactions discussed in Section 4.1.1 and Section 4.1.2. In this dataset, most incremental recovery is obtained as the system approaches the high water-cut stage, indicating that a large fraction of remaining oil is mobilized only after continuous water pathways become established and the displacement front has swept the dominant flow channels.

Figure 11.

The relationship between oil displacement efficiency and water cut (%).

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on unsteady-state coreflood experiments on Jilin Oilfield sandstones, oil–water relative-permeability curves were classified into three types according to the geometry of the water-phase curve. The convex-upward water-phase curve commonly exhibits a two-stage pattern: at first, increasing water saturation raises water relative permeability while oil relative permeability drops sharply; later, oil relative permeability declines more gradually as water relative permeability increases more steeply. The linear and concave-down types occur less frequently and are mainly associated with reservoir heterogeneity and complex flow behavior during waterflooding.

- (2)

- Analysis of cores from different development stages shows strong linear correlations between permeability and movable oil saturation (R2 = 0.89), as well as between permeability and irreducible water saturation (R2 = 0.84). By contrast, residual oil saturation tends to increase as permeability decreases, but the relationship is relatively weak.

- (3)

- A single-factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the impacts of individual parameters on oil-displacement efficiency. For low-permeability cores, increasing the pressure gradient at the early flooding stage significantly enhances recovery; however, once permeability exceeds 10 mD, the effect of the pressure differential becomes much less pronounced. Increasing the injected water volume generally improves recovery across permeability classes, but the incremental benefit diminishes and eventually approaches a plateau beyond a threshold injection level.

- (4)

- Micro-CT images provide qualitative structural evidence supporting the proposed mechanisms. Nevertheless, quantitative pore–throat statistics and clay-mineral characterization (e.g., SEM and XRD) are not included in the present dataset. Future work will integrate these microstructural and mineralogical measurements to further validate the linkage between microscopic processes (e.g., clay swelling and particle migration) and relative-permeability curve types.

Author Contributions

Methodology, L.D.; software, J.C.; validation, D.D.; data curation, L.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.; writing—review and editing, W.L.; visualization, D.D.; supervision, D.D.; funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Depeng Dong was employed by the Downhole Technology Service Branch, CNPC Bohai Drilling Engineering Company Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lei, Z.D.; Li, J.C.; Chen, Z.W.; Dai, X.; Ji, D.Q.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, Y.S. Characterization of multiphase flow in shale oil reservoirs considering multiscale porous media by high-resolution numerical simulation. SPE J. 2023, 28, 3101–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.; Klemetsdal, Ø.; Raynaud, X.; Meyner, O.; Nisen, H.M. Adaptive timestepping, linearization, and a posteriori error control for multiphase flow of immiscible fluids in porous media with wells. SPE J. 2023, 28, 554–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravljov, A.; Lanetć, Z. Relevance of Analytical Buckley-Leverett Solution for Immiscible Oil Displacement by Various Gases. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2019, 9, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafri, A.Y.A.; Mackay, E.; Stephen, K. The Relevance of the Linear Stability Theory to the Simulation of Unstable Immiscible Viscous-Dominated Displacements in Porous Media. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.Y.; Liao, X.W.; Chen, Z.M.; Zou, J.D.; Chu, H.Y.; Li, R.T. Analytical solution of Buckley-Leverett equation for gas flooding including the effect of miscibility with constant-pressure boundary. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2019, 37, 960–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Y.; Mandal, A. Improvement of Buckley-Leverett equation and its solution for gas displacement with viscous fingering and gravity effects at constant pressure for inclined stratified heterogeneous reservoir. Fuel 2021, 285, 119172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.D.O.; Silveira, G.P. Numerical Solutions of the Classical and Modified Buckley-Leverett Equations Applied to Two-Phase Fluid Flow. Open J. Fluid Dyn. 2024, 14, 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spayd, K.; Shearer, M. The Buckley-Leverett equation with dynamic capillary pressure. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2011, 71, 1088–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tartakovsky, D.M.; Jarman, K.D., Jr.; Tartakovsky, A.M. CDF solutions of Buckley-Leverett equation with uncertain parameters. Multiscale Model. Simul. 2013, 11, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabzai, A.; Honma, S. Numerical simulation of the Buckley-Leverett problem. Proc. Sch. Eng. Tokai Univ. 2013, 38, 9–14. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/83063291/Numerical_Simulation_of_the_Buckley_Leverett_Problem (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Rangel-German, E.R.; Kovscek, A.R. Matrix-fracture shape factors and multiphase-flow properties of fractured porous media. In Proceedings of the SPE 95105-MS Presented at the SPE Latin American and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 20–23 June 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.C.; Fu, Y.Q.; Liu, X.W.; Li, D.P.; Jia, Y.P.; Shao, L.F.; Yang, L.L.; Zhao, Y.D.; Zhao, T.; Yin, Q.W. A comprehensive evaluation of shale oil reservoir quality. Processes 2024, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.P.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, L.L. Analysis of Waterflooding Oil Recovery Efficiency and Influencing Factors in the Tight Oil Reservoirs of Jilin Oilfield. Processes 2025, 13, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.L.; Yu, H.M.; Wang, Y.Q.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, L.F. A Study on Characteristics of Oil-Water Relative Permeability Curves and Seepage Mechanisms in Low-Permeability Reservoirs. Processes 2025, 13, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.T.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.X.; Ma, K.Q.; Luo, X.B. Effect of Displacement Pressure Gradient on Oil-Water Relative Permeability: Experiment, Correction Method, and Numerical Simulation. Processes 2024, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Lin, Z. A Method for Calculating Oil Saturation in Unsteady-State Experiments of High-Permeability Reservoirs. Pet. Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing 2020, 39, 50–55. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.19597/J.ISSN.1000-3754.201812037 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Wang, D.Q.; Yin, D.Y. Study on Empirical Formula of Relative Permeability Curve in Water-Drive Reservoirs. Lithol. Reserv. 2017, 29, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.L.; Zhao, S.J.; Zhang, Z.H.; Wang, L.L.; Si, Y.P. Calculation Method of Relative Permeability Curve for Low-Permeability and Low-Viscosity Reservoirs—T-Type Water Drive Characteristic Curve Method. Pet. Eval. Dev. 2012, 2, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.Z.; Qiao, X.; Chen, W.C.; Xu, J.C.; Sun, Z.B.; Xie, L.S. The Influence of Reservoir Property Time Variation on Reservoir Waterflooding Development. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2016, 23, 768–771. Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=a9974d06345f1fa424f2b52398e3d8e8 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Zhang, X.X.; Du, L.; Bai, L.; Hu, W. A New Method for Optimizing and Correcting Oil-Water Relative Permeability Curves by Unsteady-State Method. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2016, 23, 185–188. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=668432124 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Peng, C.Z.; Xue, X.N.; Wang, F.L.; Shi, J.P. Experimental Data Processing Method for Oil-Water Relative Permeability by Unsteady-State Method. Pet. Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing 2018, 37, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.Z.; Dong, D.P.; Xiao, L.C. Two-Phase Low-Velocity Non-Darcy Flow Model and Relative Permeability Curve Acquisition Method. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2022, 29, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.J.; Wang, C.Q.; Cao, S.J. Improvement of Calculation Method for Gas-Water Relative Permeability in Tight Sandstone Gas Reservoirs. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2023, 38, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Experimental Research on the Characteristics of Relative Permeability Curves of Fractured Carbonate Oil Reservoirs. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.