Abstract

The COREX smelting-reduction route is a representative non-blast furnace technology, but its scale-up is hindered by insufficient gas and liquid permeability in the melter gasifier. To improve the gas and liquid permeability of the melter gasifier, coke is charged together with an iron-bearing material to partly replace lump coal to increase the burden voidage. The charged coke undergoes successive physical and chemical attacks that progressively weaken its strength, finally reducing the coke particle size and impairing overall burden permeability. Drilling “in situ” coke samples from the tuyere zone is an effective method to study coke behaviors inside a working melter gasifier. This work obtained tuyere coke samples by direct coke sample drilling during a melter gasifier blow-out and then systematically investigated the coke deterioration behaviors in the melter gasifier. The results show that the mean particle size decreased from an initial 50.3 mm to 31.6 mm at the tuyere, evidencing the severe fragmentation of coke. Basic oxides and alkali metals in the coke ash increased, indicating alkali recycling and enrichment occurred in the melter gasifier. Microcrystalline structure analysis of coke revealed a high degree of graphitization. Furthermore, coke degradation was further accelerated by both alkalis trapped in the coke pores and slag infiltration into the pores. This study clarifies the properties of the coke in the tuyere of the COREX melter gasifier and provides a theoretical basis for its operational optimization.

1. Introduction

COREX is a typical smelting-reduction ironmaking process that has achieved commercial operation for the first time [1,2]. In 2007, Baosteel introduced the largest-capacity COREX unit, COREX-3000. Later, in 2011, it was relocated to Xinjiang, where coal resources are more abundant [3]. To improve COREX performance, Bayi Steel in Xinjiang has implemented a series of technical modifications, including top gas recycling and injection [1,4], dome coal injection for gas generation [5,6], central gas injection via the CGD system in the shaft furnace [7,8], and raw-material structure optimization [9,10]. These measures have reduced the fuel rate and enhanced the hot metal quality of COREX.

COREX was originally conceived as a non-blast furnace (BF) ironmaking route that requires no metallurgical coke or a small amount of coke during the ironmaking process. However, as furnace volume increases, promoting gas development—particularly the enhancement of gas and liquid permeability in the melter gasifier—remains a persistent challenge. At Bayi Steel in Xinjiang, semi-coke and undersized coke screened from blast furnace stocks were charged into the melter gasifier to partly replace lump coal. This increases the void fraction of the burden and markedly improves its permeability, thereby securing the stable, high-efficiency operation of the furnace [11]. Coke charged at the top of the furnace falls roughly 10 m before it lands on the burden surface [12]. It is then subjected to a gasification reaction, thermal shock, mechanical abrasion, and dissolution by molten slag and metal as it moves down within the burden. This causes the decline in the particle size and mechanical strength of coke. Sampling coke through drilling the tuyere during a scheduled blow out of the furnace is currently the main method to assess coke degradation within the furnace directly. A systematic investigation of the size distribution, composition, microstructure, and microcrystalline structure of such tuyere coke samples is therefore essential to elucidate the coke deterioration mechanisms inside the COREX melter gasifier.

Extensive work has been conducted on coke samples obtained from blast furnace tuyeres. Gupta et al. [13,14] studied the coke size variation and its graphitization evolution by sampling coke from the tuyere. The main finding is that roughly half of the inorganic matter in tuyere coke existed as a glassy phase and that quartz and mullite contents dropped sharply or even disappeared compared with charged coke. Men et al. [15] reported a sharp increase in the ash content of the tuyere coke and large location-dependent variations in reactivity within a given size class. In addition, the degradation index was introduced in their work to quantify the permeability of coke in the tuyere zone. Sun et al. [16] used non-isothermal thermogravimetry to investigate the gasification of charged and tuyere coke with CO2. This work shows that the graphitization degree of coke was raised in the tuyere, and the SiC formed in the raceway increased the coke’s porosity, further accelerating coke gasification. Park et al. [17] studied the effect of the graphitization behavior of tuyere coke on its reaction kinetics and elucidated pathways for coke powder generation. Lü et al. [18] found that the reactivity, ash content, and graphitization degree of tuyere coke were higher than charged coke. Additionally, the structure deterioration mainly occurred on the coke surface, and therefore, the core retained most of its compressive strength. Li et al. [19] examined alkali enrichment in tuyere coke. These studies provide valuable insight into coke behaviors in BF, but the coke behaviors in a COREX melter gasifier differ markedly compared to the BF system, due to significant differences in bed height and operating conditions between COREX and blast furnace processes. The main differences are summarized below: the stock-line height of the melter gasifier is relatively high [20,21], significantly greater than the typical 1–2 m of BFs [22,23], so coke experiences a stronger impact during the charging process; mixed charging increases contact between the coke and the iron-bearing burden, altering both the gasification loss and dissolution (with iron and slag) behaviors of coke; and blasting pure oxygen causes a higher theoretical flame temperature in the melter gasifier, subjecting coke to a different thermal-shock regime. While there have been numerous reports on the properties of blast furnace tuyere coke samples, studies concerning the particle size distribution, microstructure, and crystallite structure of tuyere-extracted coke from COREX melter gasifiers are still lacking.

To clarify coke degradation behavior in the COREX melter gasifier, the tuyere coke samples were obtained directly from the tuyere during a scheduled blow-out. Slag and iron were removed from the samples; then, the coke particle size distribution and chemical composition were determined. The microstructural and microcrystalline structures of tuyere coke were also obtained by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). These analyses can elucidate coke evolution and degradation mechanisms in the melter gasifier and provide a theoretical basis for assessing the quality of charged coke and optimizing COREX operations.

2. Experiment

2.1. Sample Selection

Tuyere sampling can be conducted by an online or offline method. BFs now mainly use offline sampling after a blow-out. It is feasible to obtain a long sample using an offline sampling approach, and its operation is not complex. In the present study, coke samples were obtained from the COREX melter gasifier by the offline approach. The primary sampling equipment used is the advanced SG-XFQYJ-YL7000 (Shougang Group, Beijing, China) mobile blast furnace tuyere coke sampler. It is equipped with a detachable specialized sampling tube, sampling tube cover plate, support trolley, sample collection bucket, and other components. The tuyere coke sampler employs a self-propelled crawler vehicle design, operated by professionals to control vehicle movement, insertion, and retraction of the sampling tube. The sampling tube is constructed from high-strength heat-resistant steel and features a water-cooled cavity structure. The sample collection bucket is made of stainless steel.

The procedure of extracting the coke samples from one of the tuyeres is as follows. Firstly, the blowpipe and tuyere at the sampling position were removed after gas purging during the furnace blow-out period. Then, a sampling tube was inserted into the furnace from the tuyere position. The movable slide plate above the tube was opened, and the tube was vibrated to allow the tuyere coke to enter. Finally, the tube was withdrawn section-by-section, and the newly exposed coke samples were immediately sealed with a custom cover to prevent their combustion in air.

2.2. Sample Analysis

The coke deteriorated gradually in COREX under the environment of a high temperature, pressure, and various chemical reactions, especially in the most hostile zone of COREX, i.e., the raceway. Drilling and obtaining the coke samples from the tuyere of the practical COREX is one of the most useful ways to obtain the local coke deterioration information directly. In addition, the smelting condition in the raceway of COREX can also be estimated through the obtained coke samples. Thus, a series of analyses were conducted to study the coke degradation mechanism in the raceway of COREX.

The coke particle average diameter, d, can reflect the coke degradation degree directly. It was calculated by Equation (1):

where di is the average particle diameter of i-grade coke, mm; yi is the weight percentage of the i-grade coke. For each di, the midpoint of the range was taken as the representative average particle diameter. For example, for the 40–50 mm fraction, the average diameter d(1) = 45 mm.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Panalytical Empyrean, Almelo, The Netherlands) was applied to analyze the microcrystalline structure of the tuyere coke. To obtain coke ash of the coke sample, the coke sample was ground to below 200 meshes and then placed into a muffle furnace to calcinate for 1 h at 815 °C ± 10 °C. The ash compositions of the coke sample were analyzed by an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer (XRF-1800).

The microcrystalline structure analysis of coke was based on its X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern. The test was conducted with a test voltage of 45 kV and a current of 200 mA. The XRD spectra were collected with a scan range of 10° to 90° at a scanning speed of 5 (°)/min. To quantitatively analyze the microcrystalline structure of the coke sample, the average stacking height (Lc) of the carbon crystallites and layer spacing (d002) of coke were calculated by the Scherrer and Bragg equations, respectively,

where λ is the wavelength of the used X-ray, Å; K is the constant; θ002 presents the scanning angle of the (002) peak, rad; and β002 refers to the full width at the half-maximum of the (002) peak, rad.

Based on the average stacking height and layer spacing, the average stacking layer number of crystals can be further calculated by Equation (4).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Particle Size Distribution

The evolution of particle size distribution from the raw coke to the tuyere-extracted coke is the most direct macroscopic indicator of coke behavior within the melter gasifier. It reflects the cumulative effects of impact, abrasion, and chemical reactions (reduction, dissolution loss, and carburization reactions) inside the upper side of the melter gasifier. Analyzing this evolution provides quantitative insight into both the extent of coke degradation and the state of the raceway. Figure 1 shows a series of macroscopic images of the tuyere-sampled coke after screening. In this work, to obtain the particle size distribution of coke, sieving was performed using screens with different mesh sizes, yielding coke samples in ten distinct size fractions. The total mass of the tuyere coke sample was 4160.9 g, with slag and iron accounting for 352.0 g, corresponding to 7.8% of the total sample (i.e., a holdup rate of slag and iron of 7.8%). In comparison, the holdup rate at the tuyere of a typical BF is 34.35%. The significant difference indicates that the gas and liquid permeability near the COREX tuyere is superior to that of the BF.

Figure 1.

Photos of collected tuyere-extracted coke: (a) 40–50 mm, (b) 30–40 mm, (c) 25–30 mm, (d) 20–25 mm, (e) 15–20 mm, (f) 10–15 mm, (g) 5–10 mm, (h) 2.5–5 mm, (i) 1.7–2.5 mm, and (j) <1.6 mm.

Table 1 compares the particle size distributions of tuyere-extracted coke and raw coke. The fraction of coke sizes larger than 40 mm decreased from 70.1% in the raw coke to 26.3% in the tuyere sample. Conversely, the proportion smaller than 25 mm rose from 8.3% to 25.1%. After the coke entered COREX, the mean coke size decreased from 50.3 mm to 31.6 mm at the tuyere level, a reduction of approximately 37%. This marked decrease demonstrates that the coke was severely fractured and degraded when it reached the tuyere level of COREX. Consequently, the reduced coke size compromises both gas and liquid permeability within the reactor. It should be noted that compared to the blast furnace (BF), the coke particle size degradation degree in the COREX melter gasifier is less pronounced. In a large-scale BF, the average particle size of tuyere coke can decrease by approximately 80%. This difference is mainly attributed to the relatively shorter stock column and consequently shorter residence time of coke in the COREX melter gasifier. Therefore, the quality requirements for the coke used in COREX can be appropriately relaxed compared to those for BF operations.

Table 1.

Coke size distribution at the tuyere-level of COREX.

3.2. Proximate and Compositional Analysis

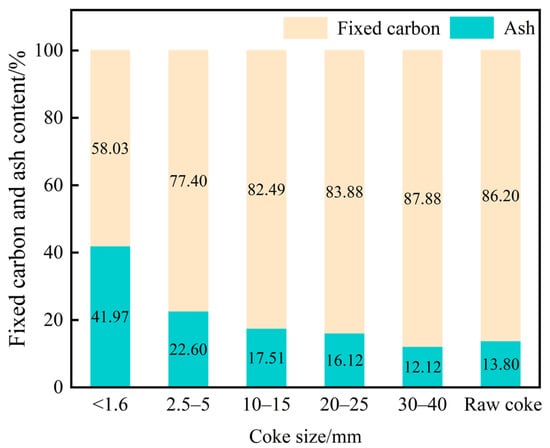

In the melter gasifier, the moisture and volatile matter in coke were almost eliminated when coke reached tuyere level. Proximate analysis of tuyere-extracted coke therefore focused on ash and fixed-carbon contents (Figure 2). Figure 2 illustrates that as the mean particle size of the coke sample decreased, its fixed carbon content also reduced. This is mainly attributed to the gradual consumption of fixed carbon during the coke degradation process. Consequently, the ash fraction increased.

Figure 2.

Proximate analysis of tuyere-extracted coke.

To further obtain more information about the composition of the tuyere-extracted coke (especially its ash composition), the ash of the coke samples was analyzed by X-ray fluorescence (XRF). Table 2 demonstrates that the acidic oxide content (SiO2 and Al2O3) of the ash generally showed an increasing trend with particle size, whereas the basic oxide content (CaO and MgO) showed an opposite trend. This may be caused by part of the coke ash entering the slag. In addition, the alkali metal content (K2O and Na2O) in the ash was markedly higher than in the raw coke. Specifically, the alkali metal content reached 16.15 wt.% for the coke sample with a size of 30–40 mm. This difference indicates pronounced alkali metal recycling and enrichment within COREX. In addition, the Fe2O3 content of tuyere-extracted coke was also generally higher than the raw coke. This demonstrates that the hot metal attack and infiltration can accelerate coke dissolution at the tuyere level within COREX. Consequently, alkali-catalyzed gasification and molten-iron (or slag) dissolution are two primary drivers of coke degradation in the COREX reactor.

Table 2.

Ash composition of tuyere-extracted coke and raw coke in COREX, wt.%.

Previous studies showed that K2O, Na2O, CaO, MgO, and Fe2O3 in coke ash can promote coke gasification, whereas SiO2 and Al2O3 have the opposite effect [24,25]. To quantify the catalytic effect of coke ash on coke gasification, the concept of a catalytic index (MCI) was introduced and is calculated as follows [25,26].

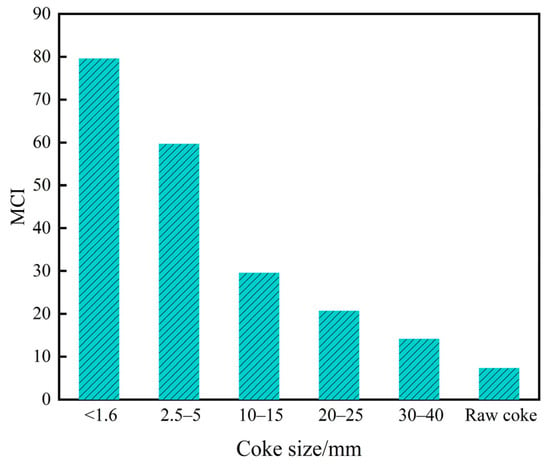

The MCI values for each coke sample are presented in Figure 3. It shows that the MCI values of tuyere-extracted coke samples distinctly increased compared to the raw coke and reached the maximum at <1.6 mm coke size. This is attributed to the accumulation of alkali metals within the melter gasifier. As solution loss proceeded, fixed carbon of coke was consumed and its ash content increased while the coke particles shrank. Moreover, the composition of the coke ash also varied as coke particle size decreased at the tuyere level (Table 2). These combined factors ultimately caused the MCI to rise as the coke particle size decreased.

Figure 3.

Catalytic indices of tuyere-extracted coke samples and raw coke.

3.3. Microcrystalline Structure Analysis

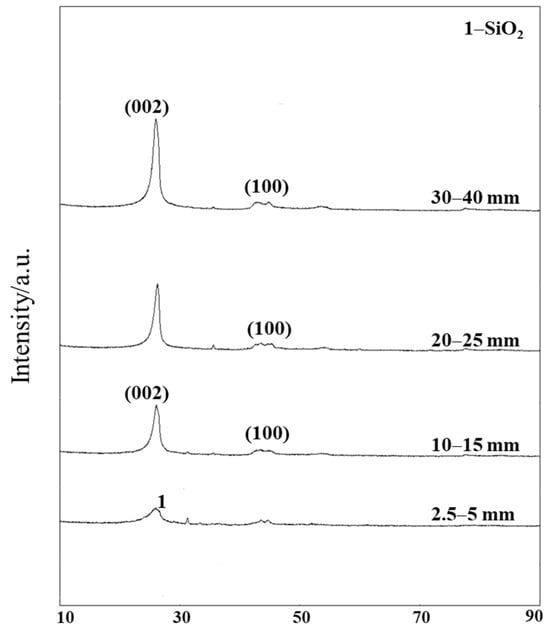

To examine the microcrystalline structure of tuyere-extracted coke with different sizes, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were first conducted (Figure 4). Based on their XRD patterns, the microcrystalline structure parameters of coke samples were further analyzed (Table 3).

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of tuyere-extracted coke of different sizes (2.5–5 mm, 10–15 mm, 20–25 mm, and 30–40 mm).

Table 3.

Microcrystalline parameters of tuyere-extracted coke.

Figure 4 shows that the dominant peak in all tuyere-extracted coke samples was graphite (002). Compared to the 002 peak, the quartz (100) peak was minor, especially for coke samples larger than 10 mm. For the coke with a size of 2.5–5 mm, the 002 peak was broader and shorter, indicating a lower graphitization degree.

The microcrystalline parameters for four group coke samples were calculated with Equations (2)–(4) and are listed in Table 3. The d002 value was similar across different samples. Both the Lc and N were large for the four group samples, implying a high overall graphitization degree of the tuyere-extracted coke. It is mainly attributed to the high-temperature environment at the tuyere level. Notably, the coke sample with a size of 2.5–5 mm exhibited the lower Lc and N, confirming its comparatively lower graphitization degree. The graphitization of coke is crucial for its mechanical strength and the formation of coke powder. Graphitization causes coke to crack due to the sliding of the graphite plane, leading to the formation of a significant amount of coke powder, which has a serious impact on coke particle size. In the COREX melter gasifier, since the tuyeres are operated with pure oxygen injection, the theoretical combustion temperature in the tuyere zone exceeds 3000 °C, which promotes the graphitization of coke in this region. Therefore, attention must be paid to the impact of coke graphitization near the tuyeres of the COREX melter gasifier on its strength.

3.4. Microstructure Analysis

To further characterize the micro-morphological features of tuyere-extracted coke, coke samples were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (FEI Quanta 250, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The coke samples were prepared by sectioning and polishing to achieve flat surfaces. Subsequently, loose particles were removed via ultrasonic cleaning in anhydrous ethanol (99.9%, 5 min), followed by drying in a nitrogen-purged desiccator (25 °C, 24 h) to prevent oxidation. The specimens were then mounted on aluminum stubs using conductive carbon tape and coated with a 10 nm Au/Pd layer via sputter coating (Leica EM ACE600, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) to ensure surface conductivity. This protocol preserves the structural integrity of coke pores while meeting the requirements for high-resolution SEM observation.

Figure 5 reveals that coke particles smaller than 1.6 mm were extremely fine and approached a powder-like morphology. In addition, these particles were interspersed with slag and iron inclusions, and the original pore structure was completely destroyed, with pores filled by bright white slag phases. They were mainly small debris exfoliated during coke degradation, so they were more susceptible to coke gasification and solution loss.

Figure 5.

Microscopic morphology of tuyere-extracted coke (<1.6 mm).

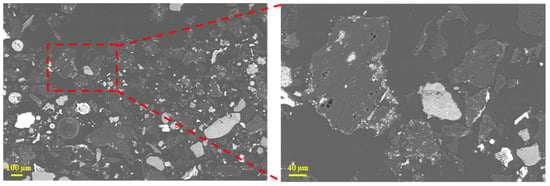

Figure 6 reveals that the coke sample with a size of 2.5–5 mm contained numerous pores; the local zone exhibited high pore density characterized by thin pore walls. In addition, deep pores were observed both within and outside these dense pore regions. The existing deep pores can accelerate gas diffusion and slag–iron infiltration within the coke, thereby aggravating coke degradation.

Figure 6.

Microscopic morphology of tuyere-extracted coke (2.5–5 mm).

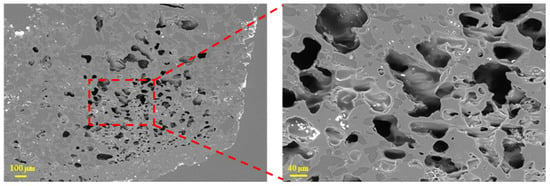

Figure 7 shows that the coke sample with a size of 10–15 mm also had a high porosity, but the pores were distributed relatively uniformly. Compared with the smaller coke (2.5–5 mm), the pores in this size class were generally larger, and some pores were filled with white solids (coke ash or molten slag).

Figure 7.

Microscopic morphology of tuyere-extracted coke (10–15 mm).

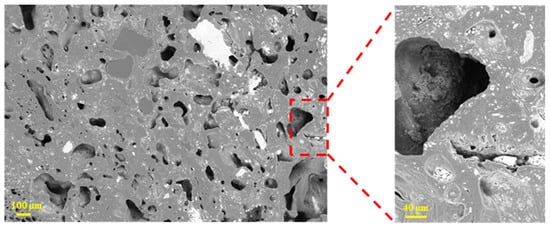

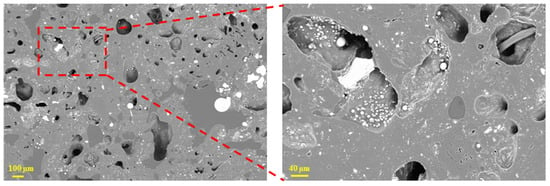

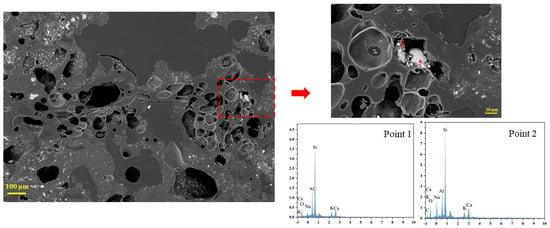

Figure 8 shows that the coke with a size of 20–25 mm had a relatively sparse pore distribution. White substances also appeared in some pores, as in the coke with size of 10–15 mm. The bigger coke sample (30–40 mm) contained pronounced pore clusters with numerous interconnected voids (Figure 9). Few big pores were present, and some white particles were retained inside the pores. To further analyze these white substances, the coke sample with a size of 30–40 mm as a representative was characterized by energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Figure 9 also reveals that spherical, granular, and amorphous coke ash (or slag) existed within the pores. EDS analysis indicates that these white substances were rich in CaO, SiO2, Al2O3, and alkali metals. Their presence accelerated the solution loss reaction and intensified coke degradation.

Figure 8.

Microscopic morphology of tuyere-extracted coke (20–25 mm).

Figure 9.

Microscopic morphology of tuyere-extracted coke (30–40 mm).

Overall, the coke samples bigger than 10 mm had similar pore structures, and the coke ash or slag clearly existed in some pores. This indicates that the degradation of large tuyere-extracted coke (>10 mm) is mainly caused by its gasification. The existence of alkali metals in the coke can further promote its gasification. In addition, some slag may infiltrate the coke pores and further accelerate its degradation.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically characterized tuyere-extracted coke from a COREX melter gasifier and provided insight into sustaining gas and liquid permeability in the melter gasifier by mitigating charged coke degradation. The main findings are summarized as follows:

(1) After undergoing a series of degradation processes in the melter gasifier of COREX, the mean particle size of coke decreased from 50.3 mm to 31.6 mm, corresponding to a reduction of 37.2%. The proportion of coke larger than 40 mm declined from 70.1% in the raw coke to 26.3% in the tuyere sample, whereas the fraction smaller than 25 mm increased from 8.3% to 25.1%. This indicates that the coke is severely fractured when it reaches the tuyere level of the melter gasifier.

(2) As the tuyere-extracted coke became finer, acidic oxides in the coke ash decreased and basic oxides increased. The alkali metal (K2O + Na2O) content in the raw coke ash was significantly lower than that of tuyere-extracted coke, indicating strong alkali metal enrichment inside the melter gasifier. Progressive dissolution consumed fixed carbon and accumulated ash, which caused coke shrinkage. Simultaneously, the composition of the coke ash also shifted. These combined effects raised the MCI as particle size decreased. In actual operation, the alkali load charged into the COREX process should be controlled to mitigate coke degradation.

(3) The d002 was similar across the four groups of coke samples, whereas both the Lc and N were relatively high, implying an overall high graphitization degree. The coke sample with a size of 2.5–5 mm exhibited the lowest Lc and N, corresponding to the least graphitization among the four size classes (2.5–5 mm, 10–15 mm, 20–25 mm, and 30–40 mm).

(4) The pore structures of tuyere-extracted coke larger than 10 mm are comparable, and spherical, granular, and irregular white substances were present within some pores. These phases consisted mainly of CaO, SiO2, Al2O3, and alkali metals, identified as slag or coke ash. Slag infiltration could also cause further dissolution and accelerated coke degradation inside the melter gasifier.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and W.L.; methodology, H.L. and W.L.; investigation, W.H., X.L. and Z.D.; resources, H.L. and W.L.; data curation, Z.D.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L.; writing—review and editing, W.H. and X.L.; supervision, H.L.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), grant number 52174300 and 52404340; the Science and Technology Innovation Key R&D Program of Chongqing, China, grant number CSTB2024TIAD-STX0009; the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, grant number KJQN202401507; the Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Advanced Metallurgy of University of Science and Technology Beijing, grant number KF24-02; the Research Foundation of Chongqing University of Science and Technology, grant number ckrc20240612.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hao Liu was employed by the CISDI Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Pang, Z.G.; Bu, J.J.; Yuan, Y.Q.; Zheng, J.L.; Xue, Q.G.; Wang, J.S.; Guo, H.; Zuo, H.B. The low-carbon production of iron and steel industry transition process in China. Steel Res. Int. 2024, 95, 2300500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xu, K.; Tian, X.; Kou, M.Y.; Wu, S.L.; Shen, Y.S. Influence of burden profile on gas-solid distribution in COREX shaft furnace with center gas supply by CFD-DEM model. Powder Technol. 2021, 392, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.F.; Chen, R.P. Optimization of Production Process Control in COREX of Bayi Steel. Ironmaking 2017, 36, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Wu, S.L.; Wang, S.Y.; Tang, Z.Y.; Yang, J.H.; Zhou, H.; Song, B.; Kou, M.Y. A mathematical model of COREX process with top gas recycling. Steel Res. Int. 2020, 92, 2000292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.L.; Liang, Q.F.; Chen, R.P.; Tian, B.S.; Zou, Q.F.; Yuan, W.N.; Liu, H.F. Study of smelting reduction iron coupled with pulverized coal gasification to produce high-concentration syngas. Sci. Sin. Technol. 2021, 51, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Long, W.; Hu, Y.F.; Tang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Kou, M.Y.; Wu, S.L. Computational fluid dynamics study of the effects of coal properties on pulverized coal gasification in the dome zone of COREX melter gasifier. Powder Technol. 2024, 436, 119492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.S.; Luo, Z.G.; Zou, Z.S. Performance simulation and optimization of COREX shaft furnace with central gas distribution. Metall. Res. Technol. 2019, 116, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xu, K.; Huang, J.; Kou, M.Y.; Wu, S.L.; Zhang, Z.L.; Zhao, B.J.; Ma, X.D. Numerical simulation of inner characteristics in COREX shaft furnace with center gas distribution: Influence of bed structure. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2022, 20, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.J.; Zhu, D.Q.; Pan, J.; Hu, B.; Wang, Z.C. Reducing process of sinter in COREX shaft furnace and influence of sinter proportion on reduction properties of composite burden. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 690−698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhang, S.F.; Gan, W.; Yuan, W.N.; Wen, L.Y.; Bai, C.G. Differences of softening and melting behavior for vanadium- titanium burden under blast furnace and OY furnace conditions. Iron Steel 2023, 58, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.H.; Wu, K.; Du, R.L. Discussion of lump coal/char properties with its disintegration in COREX process. Iron Steel 2016, 51, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.G.; You, Y.; Li, H.F.; Zhou, H.; Zou, Z.S. Experimental study on charging process in the COREX melter gasifier. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2018, 49, 1740–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ye, Z.; Kanniala, R.; Kerkkonen, O.; Sahajwalla, V. Coke graphitization and degradation across the tuyere regions in a blast furnace. Fuel 2013, 113, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ye, Z.; Kim, B.-C.; Kerkkonen, O.; Kanniala, R.; Sahajwalla, V. Mineralogy and reactivity of cokes in a working blast furnace. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 117, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, C.Z.; Wu, K.; Zhang, J.Z.; Zhe, Y.; Liu, Q.H.; Zhan, W.L. Degradation degree of tuyere coke in BF and its improvement measures. Energy Metall. Ind. 2015, 34, 6. Available online: https://yjly.cbpt.cnki.net/WKE/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=0444dd4d-308b-45e6-9ee1-11862c6e3bec (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, K.; Guo, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, C. Influence of structure and mineral association of tuyere-level coke on gasification process. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2018, 49, 2611–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Ko, K.; Lee, J.; Gupta, S.; Sahajwalla, V.; Kim, B.C. Coke size degradation and its reactivity across the tuyere regions in a large-scale blast furnace of Hyundai steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2020, 51, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, Q.Q.; Zhou, J.L.; Wang, G.H.; Du, P.; Tian, Y.S. Morphology and metallurgical behavior of coke at tuyere of blast furnace. Iron Steel 2021, 56, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.J.; Zhang, J.L.; Liu, Z.J.; Wang, T.; Ning, X.; Zhong, J.; Xu, R.; Wang, G.; Ren, S. Zinc accumulation and behavior in tuyere coke. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2014, 45, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.F.; You, Y.; Zou, Z.Z.; Cai, J.J. Numerical simulation on the charging process of new DRI-Flap distributor. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2016, 37, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Luo, Z.Z.; Zou, Z.Z.; Yang, R.Y. Numerical study on mixed charging process and gas-solid flow in COREX melter gasifier. Powder Technol. 2020, 361, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, H.; Komatsuki, S.; Akashi, M.; Shimosaka, A.; Shirakawa, Y.; Hidaka, J.; Kadowaki, M.; Matsuzaki, S.; Kunitomo, K. Validation of particle size segregation of sintered ore during flowing through laboratory-scale chute by discrete element method. ISIJ Int. 2008, 48, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Zuo, H.B.; Xue, Q.G.; Wang, J.S. A review of burden distribution models of blast furnace. Powder Technol. 2022, 398, 117055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.J.; Zhang, J.L.; Barati, M.; Khanna, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, J.; Ning, X.; Ren, S.; Yang, T.; Sahajwalla, V. Influence of alkaline (Na, K) vapors on carbon and mineral behavior in blast furnace cokes. Fuel 2015, 145, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Long, W.; Si, Y.P.; Ji, P.; Zhou, H.; Kou, M. “In situ” studies on cokes drilled from tuyere to deadman in a large-scale working blast furnace. Fuel 2024, 361, 130722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Feng, A.; Du, H. Relation between mineral catalytic index and reactivity of coke. Iron Steel 2001, 36, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.