Abstract

Unsteady flow-induced pressure fluctuations and the consequent dynamic stresses in pump-turbines are critical determinants of their operational reliability and fatigue resistance. This investigation systematically examines the spatiotemporal propagation of Rotor–Stator Interaction (RSI)-induced pressure pulsations and evaluates the corresponding dynamic stress mechanisms based on a phase-resolved fluid–structure interaction strategy. The results reveal a significant hydrodynamic duality: RSI pressure waves manifest as convective traveling waves on the pressure side but as modal standing waves on the suction side. Crucially, a severe spanwise phase mismatch is identified between the hub and shroud streamlines, which induces a periodic hydrodynamic torsional moment on the blade. Due to the rigid constraint at the blade–crown junction, this torsional tendency is restricted, resulting in high-amplitude constrained tensile stresses at the root. This explains why the stress concentration at the crown inlet is significantly higher than in other regions. Additionally, the stress spectrum shows strong load dependence, characterized by low-frequency modulations on the suction side under high-load conditions.

1. Introduction

The rapid global shift towards renewable energy integration presents unprecedented challenges to power grid operation, including peak shaving, frequency regulation, and stability maintenance [1]. As one of the most mature and large-capacity energy storage technologies, pumped storage power plants play a fundamental role in securing modern power systems [2]. In comparison, battery storage offers fast response but is limited by high cost and short lifespan; hydrogen storage enables seasonal flexibility but suffers from low round-trip efficiency (approximately 30–40%); and compressed air energy storage is geographically constrained and less efficient (around 50%) [3,4,5]. Considering efficiency, cost, and scalability, pumped-storage power plants remain the most viable option for large-scale grid regulation under current technological and economic conditions [6,7]. However, the increasingly complex and frequent transitions in operating conditions introduce significant technical challenges, particularly for high-head units [8,9].

Among these, hydrodynamic excitation-induced vibration and the resultant structural fatigue damage have become a major research focus [8,10]. In high-head pump-turbines, pressure fluctuations in the vaneless space are especially detrimental to unit stability and safety [11]. Extensive research has identified Rotor–Stator Interaction (RSI) as the primary source of such pressure pulsations, characterized by high-frequency components at the Blade Passing Frequency (BPF) and its harmonics [12]. The RSI mechanism is generally described as a combination of potential interaction, wake (jet-wake) effects, and the rotating runner pressure field [13], with its characteristic frequencies and superposition properties derivable mathematically using trigonometric theory [14,15]. Multiple factors influence the nature and intensity of these excitations. Minor guide vane oscillations can amplify Rotor–Stator Interaction (RSI) pulsations [16], and the BPF component amplitude is observed to be highest near the flow passages [14]. In addition to high-frequency RSI components, low-frequency, high-amplitude pressure pulsations—propagating differently from RSI—constitute another key instability factor [17]. Localized excitation sources have also been reported at the mid-section of the guide vane passage [18], and local reverse flow vortices at the runner inlet can intensify RSI, inducing asymmetric blade pressure distribution [19]. Unsteady flow in the clearance gap represents another significant excitation source, sometimes even dominating runner dynamic responses under specific conditions [20], with its strong unbalanced radial force fluctuations recognized as a core mechanism for high-cycle fatigue and lateral shaft vibrations [10]. The ultimate harm of these pressure fluctuations lies in their contribution to mechanical fatigue damage. Studies indicate that guide vane dynamic stress is significantly influenced by flow unsteadiness, particularly vortex motion, with the lowest fatigue life occurring at low loads due to high stress amplitudes, complex frequency content, and strong flow chaos [21]. Fatigue cracks in runners are closely related to stress concentration zones and hydraulic excitation [22], and maximum stress points on impellers are prone to rapid fatigue failure, where local microcracks initiate small-scale yielding and accelerate damage [23]. Various mitigation strategies have been explored. Increasing the vaneless space has been suggested to alleviate RSI effects [24], while increasing guide vane height may reduce RSI intensity and associated dynamic stresses [25]. In contrast, pre-opening guide vanes, though improving “S-shaped” characteristics, can exacerbate RSI [26]. The manifestation of RSI itself varies with operating conditions, appearing primarily as potential interaction at low blade loading and as a rotating pressure field at high loading [25]. Under phase-modulation conditions, the presence of air–water two-phase flow further complicates RSI mechanisms and structural responses [27]. From a modeling perspective, full-flow passage CFD models that include clearance flow yield more accurate simulations of hydraulic excitation forces [28].

Unlike previous studies, which have predominantly focused on characterizing the excitation sources or frequency spectra of RSI, their investigations often stop short of delineating the complex spatiotemporal loading mechanisms acting on the twisted blade surface. Furthermore, the physical link between the hydrodynamic wave propagation and the specific structural deformation modes remains inadequately explored. This study addresses these critical gaps by establishing a phase-resolved spatiotemporal analysis framework to shift the focus from simple source identification to hydrodynamic load decoupling. The novelty of this work lies in revealing the propagation duality of RSI-induced pressure waves (traveling vs. standing modes) and quantifying the asynchronous loading effect induced by spanwise phase mismatch. By integrating these fluid dynamics insights with structural constraint mechanisms, this paper provides a mechanistic understanding of how hydrodynamic torsion drives the dynamic stress formation, offering a basis for fatigue life prediction and operational safety enhancement in ultra-high-head conditions.

Following this introduction, the paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 details the numerical simulation and experimental validation, including the governing equations, simulation setup, and FSI coupling strategy. Section 3 outlines the methodology. Section 4 presents the dynamic fluid and structural analysis, specifically focusing on the decoupling of propagation mechanisms and stress characteristics. Section 5 provides the discussion, and Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Validation

2.1. Governing Equations

2.1.1. Governing Equations for the Fluid Domain

For the FSI problem in pump-turbine units, considering the actual size of the flow-passing components and the properties of the structural material, the deformation is minimal, and its influence on the flow field can be essentially ignored. Thus, on the FSI interface, only the transfer of hydraulic forces from the fluid domain to the structural domain was considered, without accounting for the equilibrium of displacement and traction force.

To simplify the analysis for most operating conditions, the fluid within the pump-turbine is typically assumed to be incompressible, with liquid water at normal temperature serving as the flow medium. Under the premise of neglecting heat exchange, the energy conservation equation can be omitted. Consequently, the fundamental governing equations describing the fluid behavior are primarily established based on the principles of mass and momentum conservation.

Assuming the working fluid inside the turbine is incompressible, the mass conservation equation and the momentum conservation equation can be expressed as follows:

where the terms are defined as: represents the fluid density; t is time; is the Reynolds-averaged velocity vector; represents the static pressure; is the molecular viscous stress tensor; and denotes the general source term of momentum, which includes the gravitational body force () and, for rotating subdomains, the Coriolis and centrifugal forces. The term is the Reynolds stress tensor; represents the molecular viscosity of the fluid; represents the turbulent eddy viscosity; represents the unit tensor; and is the turbulent kinetic energy.

To close the system of equations and accurately resolve the turbulent flow structures, the Shear Stress Transport (SST) - turbulence model proposed by Menter is adopted. The SST - model incorporates a damped cross-diffusion derivative term and modifies the definition of eddy viscosity to account for the transport of turbulent shear stress. This modification significantly improves the prediction accuracy of flow separation under strong adverse pressure gradients, which are prevalent in the runner channels during off-design operations. Furthermore, the model provides superior resolution of the boundary layer, ensuring high-fidelity calculation of the wall pressure fluctuations that serve as the excitation source for the subsequent structural dynamic analysis. The transport equations for the turbulent kinetic energy and the specific dissipation rate are defined as:

where represents the production of turbulence kinetic energy due to mean velocity gradients; is the turbulent eddy viscosity; is the invariant measure of the strain rate; and are the blending functions characteristic of the SST model, which ensure smooth transition between the boundary layer and the free shear flow; is a structure parameter; and , , , , and are the empirical model constants.

2.1.2. Rotor–Stator Interaction

The runner of a pump-turbine features a relatively small radial dimension, while the trailing edges of the guide vanes are designed with substantial thickness. This structural configuration leads to significantly enhanced wake shedding from the guide vanes. Consequently, a highly non-uniform flow field develops at the guide vane outlet. As the runner rotates through this disturbed flow, specific potential flow fluctuations are induced at the runner inlet due to the unsteady hydraulic excitation. The interaction between these fluctuations and the stationary components creates a pronounced periodic RSI within the vaneless space. This RSI caused periodic potential fluctuations generated at the runner inlet produce excitation forces at specific frequencies; when these frequencies align with structural natural frequencies, while their spatial distribution matches the system’s vibrational modes, dangerous resonance occurs, amplifying dynamic stresses beyond design limits. Simultaneously, the persistent RSI-driven pressure pulsations transfer high-frequency alternating stresses to both rotating and stationary components, initiating cumulative fatigue damage that may lead to high-cycle failure. Consequently, RSI not only dictates immediate vibration response but fundamentally determines the long-term structural integrity and operational reliability of hydraulic machinery. The final pressure field generated by dynamic-static interference can be expressed as the superposition of a rotating pressure field and a stationary pressure field. After modulation, the final pressure field can be represented in the stationary reference frame as:

where represents the rotational angular velocity of the runner; N represents the rotational speed of the runner; m represents the harmonic order of the rotating system, this integer (m = 1, 2, 3, …) describes which harmonic of the rotor’s blade-passing frequency is being considered; n represents the harmonic order of the stationary system, this integer (n = 1, 2, 3, …) describes the spatial harmonic of the stator itself; Amn is the combined amplitude represents angular position in the stationary coordinate system; is the phase of the m-th order harmonic of the rotating system; and is the phase of the m-th order harmonic of the stationary system.

This pressure field presents two radial pressure patterns, with the nodal diameter count d defined as:

In most instances, as the harmonic order increases, the amplitude diminishes progressively. So only d1 = d2 is taken into account here. Afterwards, in the rotating coordinate system and the stationary coordinate system, the angular velocities and excitation frequencies are formulated as:

where , represents the angular velocities in the rotating coordinate system and the stationary coordinate system, respectively; , signify the excitation frequencies in the rotating coordinate system and the stationary coordinate system, respectively; and is the rotational frequency of the runner.

2.1.3. Flow-Induced Structural Dynamic Equation

The weak-FSI method is applied to simulate the structural dynamic response.

Among them, , , and represent the system matrix, unknown variables, and external forces of the fluid domain, respectively; and , , and represent the system matrix, unknown variables, and external forces of the structural domain, respectively.

For a general linear elastic structure, its transient dynamic equilibrium equation can be represented as:

Among them, the structural quality matrix is represented by , the structural damping matrix by , and the structural stiffness matrix by . The vector of nodal displacements is represented by , and inertial forces, which include gravity and centrifugal force, are represented by . represents the hydraulic excitation force in the context of transient flow processes in hydraulic turbines. The complete finite element discrete equations for the fluid–solid coupling problem can be expressed as follows:

where the terms are defined as:

: the equivalent coupled mass matrix of the system.

: the equivalent coupled stiffness matrix of the system.

: the coupling matrix governing the interaction.

2.2. Simulation Setup and Validation

2.2.1. The Geometry Model

The ultra-high-head pump-turbine investigated in this study is a prototype unit of a pumped storage power station, with a total installed capacity of 1800 MW. The computational domain encompasses the spiral casing, stay vane, guide vane, runner, runner cone, crown chamber, band chamber, pressure balanced pipes, and draft tube. The computational CAD model adopted in this study corresponds to the prototype, which refers to a real full-scale unit, and its geometric model is shown in Figure 1 and the basic parameters are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Geometry of the ultra-high-head pump-turbine.

Table 1.

Basic parameters of the prototype pump-turbine.

2.2.2. Boundary Conditions and Settings

The analysis is fully transient and implemented in ANSYS Workbench 24R1, employing a unidirectional FSI coupling strategy. ANSYS CFX 24R1 is used for fluid simulation, while ANSYS Mechanical 24R1 handles structural analysis. For the fluid domain, the same numerical setups and models as those in References [29,30] were applied, which have been rigorously validated against experimental measurements. A one-way fluid–structure interaction (FSI) methodology was adopted to assess the runner’s structural response. The transient CFD simulation utilized the SST k-ω turbulence model and advanced with a time step corresponding to 1° of runner rotation. A constant mass flow rate was specified at the inlet boundary, while a fixed static pressure was applied at the outlet. The wall boundaries were set as no-slip walls. After ensuring flow periodicity over ten full runner revolutions, the pressure field from the final two revolutions was extracted and applied as the hydraulic load in the subsequent structural analysis.

2.2.3. FSI Coupling Strategy

A one-way FSI strategy is adopted based on the specific frequency characteristics of this study. The primary excitation frequency (22 ) is a non-resonant frequency well-separated from the runner’s natural modes in water. Under this high-frequency forced vibration regime, the structural displacement is negligible (<0.1% of the channel width), and the fluid–structure feedback is effectively decoupled. Thus, the one-way approach reliably captures the stress mechanisms without the need for two-way coupling. A critical challenge lies in the data transfer across the non-conforming meshes between the fluid (FVM) and structural (FEM) domains. To prevent aliasing or phase distortion of high-frequency RSI signals, a conservative interpolation algorithm is employed.

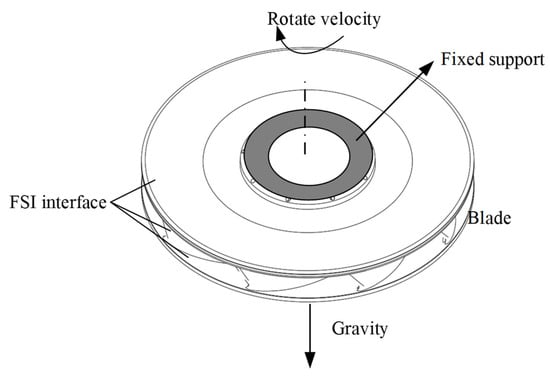

For the structure domain, the interface between the runner structural domain and the fluid domain is defined as an FSI boundary, through which the hydraulic loads generated by the fluid are transmitted. A fixed constraint is applied at the connection between the runner and the turbine shaft. The analysis considers the effects of both centrifugal and gravitational forces, as illustrated in Figure 2. The Newmark- implicit time integration scheme is utilized with a time step of 1° of runner rotation.

Figure 2.

FSI model setting of the ultra-high-head pump-turbine.

2.2.4. Validation of the FSI Model Against Site Measurements

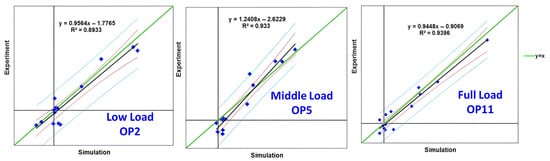

To strictly verify the accuracy of the proposed FSI coupling strategy in predicting dynamic stresses, a quantitative validation was conducted using site measurement data from a prototype high-head Francis runner, as reported by Huang et al. [13]. The numerical model setup and boundary conditions were aligned with the prototype specifications to ensure comparability. We conducted a comprehensive comparison between the numerically predicted dynamic strains () and the experimentally measured values () obtained from strain gauges on the runner blades across 12 different operating points. Figure 3 visualizes this correlation using linear regression analysis, where each data point represents a pair of simulated and measured dynamic strain values. The statistical results demonstrate a high degree of fidelity. The data points are tightly clustered around the regression line, indicating that the simulation correctly captures the trend of dynamic response variations under changing operating loads. Crucially, the slopes of the linear regression functions for all operating points are consistently close to 1 (). This strong linear agreement indicates that the magnitude of the simulated RSI-induced stress fluctuations matches the physical reality with high precision. This validation confirms that the FSI approach adopted in this study effectively captures the essential fluid–structure coupling mechanisms.

Figure 3.

Comparison of static stresses at different loads [13].

2.3. Mesh Division and Independence Check

For fluid computational domains, mesh independence was assessed using Richardson extrapolation, as shown in Table 2. Three systematically refined meshes containing 8,035,314, 3,658,663, and 1,675,718 elements, respectively, were generated using a constant refinement ratio r ≈ 1.3 were generated, and simulations were performed on each mesh. The unit efficiency and representative pressure coefficients in the unvaned region were selected as monitored quantities. For each quantity, the apparent order of accuracy, the Richardson-extrapolated value and the corresponding mesh convergence index were evaluated following the standard Richardson extrapolation procedure. The results show monotonic convergence towards the extrapolated solution, and the relative difference between the two finest meshes, as well as the estimated numerical uncertainty, remains below 1% for all monitored quantities. Therefore, to strike a balance between computational efficiency and solution accuracy, the coarse mesh is considered sufficiently mesh-independent and is adopted for all subsequent simulations. The average orthogonality is 0.82 and the average skewness is 0.038.

Table 2.

Estimated results of mesh error.

In Table 2. η denotes the unit efficiency; normalized P denotes the pressure at the measuring point in the unvaned region relative to the half-rated head. For each quantity, , and denote the solutions on the coarse, medium and fine meshes, respectively. is the Richardson-extrapolated value based on these two meshes. The mesh convergence index for the fine–medium mesh pair, , is computed following Roache’s method and represents an estimate of the relative discretization error of the fine-mesh solution.

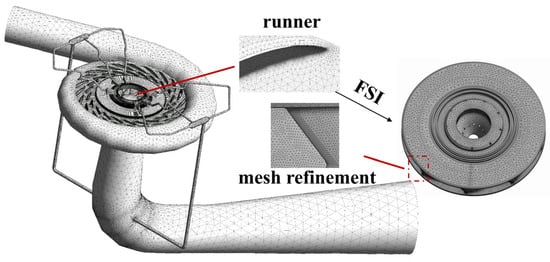

The structural computational domain was discretized using an unstructured mesh primarily composed of tetrahedral elements. A local refinement was applied to the runner blades to accurately capture the flow and stress gradients. A mesh independence study was conducted, with the maximum principal stress point on a blade serving as the monitoring parameter. As shown in Figure 4, a mesh independence study was conducted using grid sizes ranging from 0.24 million to 8.00 million elements. The results demonstrated that the predicted dynamic stress levels at critical blade locations stabilized significantly; specifically, the variations were less than 0.4% when the mesh size exceeded 1.24 million elements. Therefore, considering both computational efficiency and numerical accuracy, the mesh with 1.24 million elements was selected for all subsequent simulations, featuring a local element size of 10 mm on the runner blades (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Structural domain mesh independent verification of the ultra-high-head pump-turbine.

Figure 5.

Mesh distribution of fluid domain and runner structure field.

3. Methodology

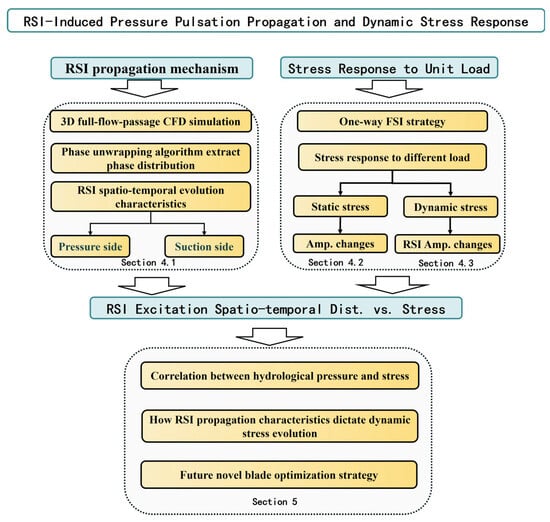

The research framework follows a systematic progression from fundamental mechanism identification to comparative stress evaluation (Figure 6). First, the primary objective of applying the phase unwrapping algorithm in Section 4.1 is to reconstruct the continuous spatiotemporal evolution of RSI pressure waves, which enables the identification of specific propagation paths. Subsequently, the intent of utilizing the one-way FSI strategy in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3 is to quantify the structural vulnerability under different operating regimes. By contrasting full load and 50% load conditions, we aim to characterize the runner’s load-sensitivity and pinpoint critical stress zones. Ultimately, based on the findings of Section 4, the goal of Section 5 is to establish a deterministic physical link beyond numerical reporting, revealing how specific propagation characteristics physically dictate the dynamic stress evolution.

Figure 6.

Research framework diagram.

4. Dynamic Fluid and Structural Analysis

4.1. Decoupling of Pressure and Suction Surface Propagation Mechanisms

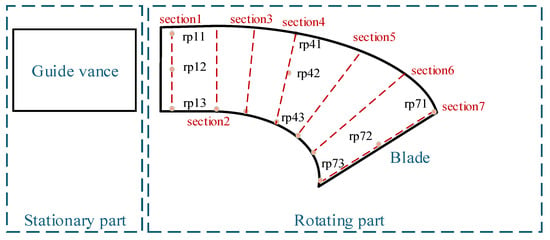

This part aims to characterize the unsteady hydraulic excitation sources, with a focus on identifying the frequency content and spatial distribution of RSI induced pressures within the runner flow passages. The simulation results under the rated operating condition were selected for spectral analysis using the Fast Fourier-Transform (FFT). When performing FFT analysis, the sampling frequency employed corresponds to the reciprocal of the fluid computation time step. The locations of all monitoring points are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of pressure pulsation measurement points.

In Figure 7, rp denotes the pressure side of the blade and rs denotes the suction side of the blade.

To intuitively quantify the spatiotemporal distribution law of pressure fluctuations on the surface of complex three-dimensionally twisted blades, the unsteady pressure data are first non-dimensionalized and spatially mapped according to Equations (19) and (20), prior to the in-depth analysis of flow field characteristics.

where denotes the instantaneous pressure at time t, Pa; denotes the time-averaged pressure at time t, Pa; denotes the density of the fluid, kg m−3; g denotes the acceleration of gravity, m s−2; and Hr denotes the head of rated condition, m.

Considering the spatial location and the significant twisted geometric characteristics of Francis runner blades, the Cartesian coordinate system cannot effectively characterize the propagation behavior of pressure waves along the streamlines. To this end, this paper constructs a normalized streamwise coordinate system and maps the three-dimensional blade surface to the dimensionless streamwise domain :

where denotes the arc length along the streamline from the leading edge to point i, is the total chord length of the streamline. Specifically, corresponds to the blade inlet, while corresponds to the blade outlet. On this basis, the blade surface is further decomposed into three characteristic flow surfaces, namely the crown-adjacent side, the middle region, and the band-adjacent side.

Furthermore, since the raw phase angle obtained from the standard FFT is strictly confined within the principal interval , resulting in non-physical discontinuities, a phase unwrapping algorithm is introduced to reconstruct the spatial continuity. The unwrapped cumulative phase is defined as:

where is the continuous cumulative phase at the normalized location ; is the principal phase value computed by FFT, bounded in ; and is an integer sequence determined by the continuity condition, ensuring that the absolute phase difference between adjacent spatial points is less than .

To ensure the reliability of the phase-resolved analysis, a spectral amplitude masking strategy was applied, restricting the phase extraction strictly to the dominant RSI harmonics (22) with high signal-to-noise ratios. Furthermore, the temporal sampling step of 1° corresponds to approximately 16.4 sampling points per wave cycle for the highest frequency of interest (22). This density is more than eight times the theoretical Nyquist limit, providing a reasonable balance that ensures high phase fidelity and negligible discretization errors.

4.1.1. Spatiotemporal Propagation Characteristics of RSI

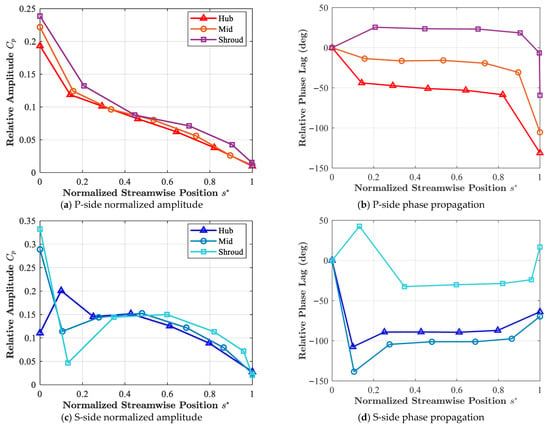

As shown in Figure 8, it reveals that the pressure fluctuations induced by RSI exhibit a significant in-plane asymmetric propagation mechanism on the surface of runner blades.

Figure 8.

Phase-Resolved Spatiotemporal Thermodynamic Heatmap. (a) P-side space-time evolution, (b) S-side space-time evolution.

On the pressure surface (P-side), the spatiotemporal map presents clear, streamwise-inclined banded stripe structures. This characteristic indicates that although the RSI excitation source is located externally, its response on the pressure surface behaves as a typical convective traveling wave. The normalized amplitude curve (Figure 8a) shows that high-amplitude pressure peaks first act on the leading edge (), and then migrate toward the trailing edge along the streamline at a finite phase velocity. This traveling wave mechanism confirms that the pressure surface is the primary bearing surface for the impact energy of guide vane wake. In contrast, the dynamic response of the suction surface (S-side) is dominated by standing wave or bulk mode oscillation. Except for the local impact characteristics observed in the region within the first 10% chord length of the leading edge, the phase distribution in the middle and rear regions tends to be flat (Figure 8b).

4.1.2. Phase Evolution Laws and Characteristics Along the Blade Span

Figure 9 further quantifies the asynchronous characteristics of pressure wave propagation along the blade spanwise direction (crown-adjacent side, middle region, band-adjacent side). By comparing the phase curves of the three characteristic streamlines, a significant spanwise phase gradient is found to exist on the pressure surface.

Figure 9.

Spanwise phase gradient and relative amplitude of pressure surface pressure waves.

As for the pressure side, for the crown-adjacent streamline (Hub), the phase exhibits the maximum streamwise decreasing rate, dropping from 0° to 130°, indicating that this region is subject to flow passage geometric constraints and secondary flow effects, resulting in a relatively slow pressure wave propagation velocity and a significant phase lag. For the band-adjacent streamline (Shroud), the phase variation is gentle and approximately a horizontal straight line, which demonstrates that the pressure fluctuation in this region shows a quasi-synchronous response. The suction surface exhibits a significant characteristic of global standing wave. Beyond the leading-edge impact region, both the crown-adjacent (Hub) and band-adjacent (Shroud) streamlines show a plateau characteristic with a near-zero slope in their phase curves. This confirms that the pressure field on this side is mainly controlled by the flow passage system mode.

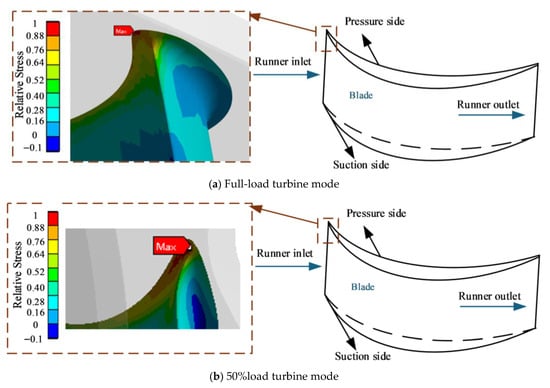

4.2. Analysis of Static Stress

The stress concentration zone of the rated working condition blades is located at the junction of the pressure surface inlet and the upper crown, as well as at the junction of the middle of the pressure surface and the upper crown, and the middle of the suction surface and the lower ring (Figure 10). The maximum principal stress extreme value is found at the junction of the pressure surface inlet and the upper crown. The junction between the suction surface and the upper crown exhibits significant tensile stress. Under the minimum head condition, the position of the blade’s maximum stress extreme value is the same as in the rated condition. The stress extreme value differs by 33.47% from the rated condition, while the range of the stress concentration zone at the pressure surface inlet and upper crown junction is considerably larger.

Figure 10.

Principal Stress Distribution Diagram. (a) Distribution of static stress in the runner and local stress extreme values of Full-load turbine mode; (b) Distribution of static stress in the rotor and local stress extreme values of 50% load turbine mode. Note: the stress value is the ratio of local stress to the maximum principal stress in each case.

4.3. Analysis of Dynamic Stress

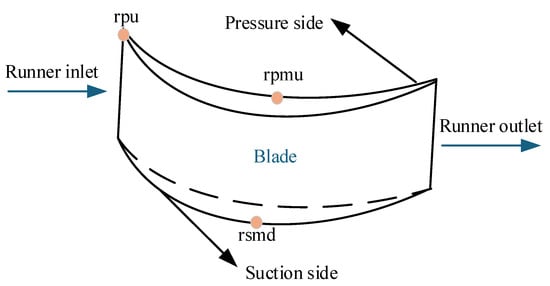

The final and core part of the analysis is designed to quantify the dynamic stress response resulting from the unsteady pressure loads. It specifically targets evaluating the distinct contributions of RSI excitations across different operational loads and at the pre-identified stress concentration zones. To analyze the characteristics of dynamic stress variation, this study investigates two operating conditions: full-load operation in turbine mode and low-load operation in turbine mode.

The locations of measurement points are selected at the positions where the maximum stress values occur in the three main stress concentration areas. The schematic diagram of the monitoring points is shown in Figure 11, which includes rpu (the first principal concentration area), rpmu (the second principal concentration area), and rsmd (the third principal concentration area). To facilitate a comparative analysis of the stress levels and their pulsation characteristics under different operating conditions, the stress values and stress pulsation values are normalized, defined as the ratio of the stress to the maximum stress of the two conditions and the ratio of the stress pulsation amplitude to the maximum stress pulsation amplitude of the two conditions, respectively. fn represents the fundamental rotational frequency, 9fn represents the blade passing frequency, and 22fn represents the Rotor–Stator Interaction frequency.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of stress monitoring point locations.

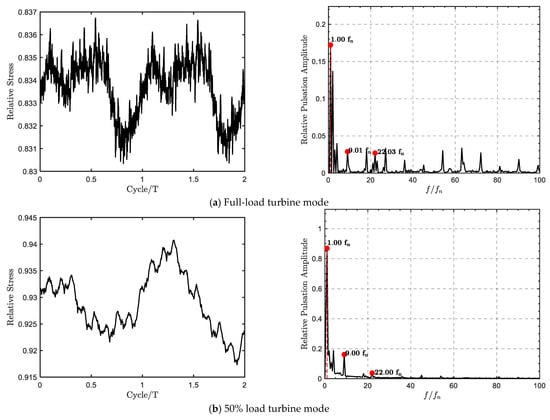

As shown in Figure 12 at the monitoring point rpu under full-load turbine conditions, the dominant pressure pulsation frequency is the 2nd harmonic, with a relative amplitude of 0.6. The amplitudes of the 9th and 22nd harmonics are 0.35 and 0.22, respectively. Under 50% load turbine conditions, compared to the rated condition, the low-frequency noise components are significantly reduced. The number of pulsation harmonic frequencies below the 9th harmonic is reduced by about 29%. The dominant pulsation frequency shifts to the 4th harmonic, with an amplitude of 0.86, while the 9th and 22nd harmonic amplitudes are 0.48 and 0.24, respectively.

Figure 12.

rpu measurement point dynamic stress variation chart.

As shown in Figure 13 under full-load turbine conditions, the dominant dynamic stress frequency is the 1st harmonic, with an amplitude of 0.17. The amplitudes of the 9th and 22nd harmonics are 0.028 and 0.026, respectively, with numerous high-frequency noise components present. Under 50% load turbine conditions, the dynamic stress spectrum becomes more concentrated: the number of pulsation harmonic frequencies below the 9th harmonic is reduced by 50%, while the 1st harmonic remains dominant with a normalized amplitude of 0.86. The amplitudes of the 9th and 22nd harmonics under this condition are 0.16 and 0.037, respectively. These characteristics collectively indicate a low-frequency, high-amplitude pulsation pattern.

Figure 13.

rpmu measurement point dynamic stress variation chart.

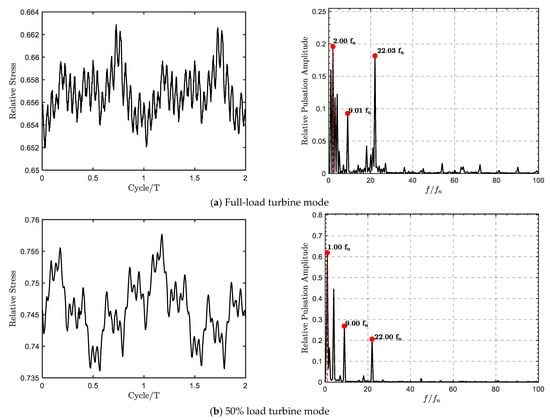

The dynamic stress behavior at monitoring point rsmd, summarized in Figure 14, exhibits distinct spectral characteristics under different operating conditions. Under full-load turbine conditions, the dominant frequency is the 2nd harmonic with an amplitude of 0.19, accompanied by significant low-frequency broadband noise. The amplitudes of the 9th and 22nd harmonics are 0.09 and 0.18. At 50% load turbine operation, the spectrum becomes more concentrated: only four frequency components are present, and the first harmonic has the largest normalized amplitude of 0.61. The amplitudes of the 9th and 22nd harmonics are 0.26 and 0.21.

Figure 14.

rsmd measurement point dynamic stress variation chart.

As shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, under the low-load turbine operating condition, the number of pulsation harmonic frequencies below the 9th harmonic decreases, and the spectrum becomes more concentrated: the number of significant harmonics at point rpu decreases from 7 to 5, at point rpmu from 4 to 2, and at point rsmd from 5 to 2. Under the high-load operating condition of the turbine, there are more pulsation harmonic frequencies, which are mainly concentrated in the low-frequency region. However, for the second stress concentration area, the pulsation harmonic frequencies are mostly concentrated in the high-frequency region, with 7 out of 16 significant components located above 40.

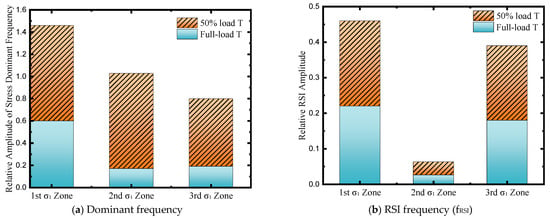

As shown in Figure 15, under the low-load operating condition, the normalized stress pulsation amplitude is higher than that under the high-load operating condition at all three stress concentration regions. The peak amplitude increases by about 0.69 in the second region, with the increment in the second region being approximately 2.7 times that in the first region and about 1.6 times that in the third region. In the turbine mode, the load exerts a significant influence on the stress pulsation amplitude corresponding to the runner blade passing frequency, while it has a relatively minor impact on the stress pulsation amplitude of the rotor–stator interaction frequency. The RSI peak amplitude increases by about 0.03 in the third region, with the increment in the third region being approximately 1.5 times that in the first region and about 2.7 times that in the second region. Furthermore, regarding the stress pulsation amplitude at the blade passing frequency, the third stress concentration area is more sensitive to the unit load.

Figure 15.

Relative amplitude of different frequencies. (a) the relative amplitude of stress pulsation dominant frequency under different conditions; (b) the relative amplitude of stress pulsation RSI under different conditions. T for turbine mode; fRSI for RSI frequency. σ1 represent the maximum principal stress.

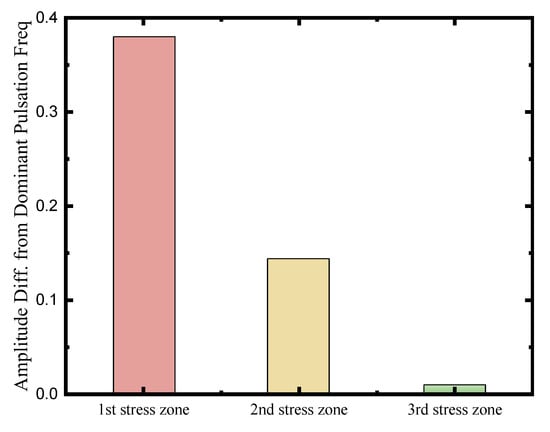

As illustrated in Figure 16, RSI exerts absolute dominance within the third stress concentration zone, demonstrating the strongest excitation authority. The amplitude deviation of the RSI component in this region is merely 0.01. This negligible deviation substantiates that the dynamic stress response in the lower shroud region is almost entirely locked to the fundamental RSI fluctuations within the flow field. This finding corroborates the conclusions drawn from the preceding fluid dynamics analysis—specifically, that the streamlines on the lower shroud side exhibit flat phases and maintain high coherence. It further indicates that this region primarily responds to global bending modes driven by RSI traveling waves. In contrast, the amplitude deviation of the RSI component in the first stress concentration zone increases significantly to 0.38.

Figure 16.

Comparison of amplitude difference from dominant pulsation frequency (DPF) of the RSI frequency in turbine mode. σ1 represent the maximum principal stress.

5. Discussion

By constructing a phase-resolved spatiotemporal evolution analysis framework, this study quantitatively characterizes the asymmetric propagation of Rotor–Stator Interaction (RSI) pressure pulsations within the runner. This section elucidates how the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of fluid excitation translates into specific structural loading patterns and reveals the physical origins governing the frequency dominance mechanism across different stress concentration zones.

The spatiotemporal evolution analysis reveals a distinct “duality” in the fluid excitation mechanism within the runner: the Pressure side (P-side) is dominated by guide vane wake convection, exhibiting traveling wave characteristics, whereas the Suction side (S-side) is governed by modal response, exhibiting standing wave characteristics. This fundamental disparity in propagation mechanisms results in a severe phase mismatch between the two sides of the blade at identical streamwise locations. The RSI pressure peak on the pressure surface spatially overlaps with the response trough on the suction surface, inducing a massive instantaneous net pressure load across the blade section. This pressure differential drives a global bending deformation. According to the maximum principal stress criterion, this bending induces high-amplitude tensile principal stress on the convex surface—the direct mechanical driver of fatigue crack initiation and propagation.

Beyond in-plane asymmetry, the spanwise phase analysis further uncovers the deep hydrodynamic roots of stress concentration in the crown region. Streamlines at the hub (crown) side exhibit a significant phase lag relative to the shroud (band) side, implying that RSI pressure waves do not sweep across the blade span simultaneously but instead form a highly distorted wavefront. This spanwise phase mismatch introduces a strong non-synchronous loading effect. The resulting hydrodynamic load attempts to force a twisting deformation of the blade. However, because the blade is subjected to a rigid fixed boundary at the crown connection, this phase-driven warping is strongly constrained. According to elasticity theory, such constrained torsion induces extremely high normal stresses at the section edges. This coupling of fluid twisting and structural constraint manifests as a sharp rise in maximum principal stress at the root connection. This explains why RSI, despite the extremely high stiffness of the runner, can induce high-amplitude tension sufficient to cause crack opening in the crown region.

Quantitative evidence confirms that the dominance of RSI exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity, with the band mid-chord region acting as a domain of absolute dominance where the amplitude deviation index between the maximum principal stress and the fundamental RSI pressure component is merely 0.01, indicating near-perfect coherence. The quasi-synchronous or standing-wave phase trajectories observed along the band streamline ensure a coherent and stable bending load, free from dynamic phase mismatch. Combined with the relatively lower constraint stiffness at the band compared to the rigid crown, this allows the blade to couple efficiently with the fluid load into a coherent global bending mode, effectively making the principal stress in this region a linear transfer function that faithfully reflects the RSI source intensity without non-linear constraint distortions. Conversely, at the crown inlet, the amplitude deviation of the RSI component increases to 0.38, indicating that the direct contribution of RSI to the peak tension is significantly reduced. This aligns with the mechanism described above: although RSI exerts a twisting tendency via spanwise phase difference, the complex geometric curvature and extremely high stiffness of the Crown region prevent the structural response from following the fluid linearly. Instead, the response is characterized by complex constrained stress concentrations.

In summary, to mitigate dynamic stress issues induced by RSI in ultra-high-head pump-turbines, the design strategy must shift from traditional passive reinforcement, e.g., increasing blade thickness, to active flow field phase control. During the hydraulic design phase, it is recommended to adjust the blade stacking law, e.g., adopting a specific lean distribution, to actively compensate for the spanwise phase lag caused by channel geometry. This aims to synchronize the arrival time of pressure waves across the span, thereby eliminating the hydrodynamic twisting component and reducing the peak tensile principal stress at the crown connection at the source. Additionally, for operation and maintenance, the mid-chord root region should be utilized as the optimal “structural probe” for monitoring RSI intensity.

Compared with previous studies that quantitatively evaluated the fatigue response of guide vanes, runners, and shaft systems under specific operating conditions [25,26], the present work places greater emphasis on the spatiotemporal duality of RSI propagation and the novel stress concentration mechanism induced by spanwise phase mismatch. Unlike traditional approaches that attribute high stresses primarily to geometric discontinuities, this study reveals deeper hydrodynamic roots: how asynchronous hydrodynamic loading generates periodic torsional moments that interact with the rigid structural constraint at the blade crown. On this basis, the mechanistic link between fluid phase distortion and the resulting constrained structural response is defined. An engineering guidance framework is established that advocates shifting from passive strength verification to active flow phase control in blade design, and suggests differentiated monitoring configurations based on the spatial heterogeneity of RSI dominance. This mechanistic perspective complements earlier component-level assessments and provides a more unified understanding of how the low-frequency RSI pressure field fundamentally shapes the dynamic stress behavior and fatigue performance of ultra-high-head pump-turbine runners through complex fluid–structure coupling pathways. The findings presented herein are characterized by the hydrodynamic duality and constrained torsion, which are particularly prominent in ultra-high-head pump-turbines due to their high rigidity and narrow channels. For medium- to low-head Francis turbines, while the fundamental RSI mechanism persists, the structural response may differ. Therefore, these results serve as a rigorous reference for high-head machines and a qualitative guideline for other types. Based on the identified spanwise phase mismatch mechanism, the proposed design strategies, such as the stacking law and phase control, are presented as conceptual inferences. While they offer a physics-based roadmap for optimization, future research will focus on systematic parametric analyses to establish rigorous scaling laws and quantitatively validate these concepts.

6. Conclusions

The following conclusions are drawn from the systematic examination of Rotor–Stator Interaction (RSI) phenomena and their effects on structural behavior under various operating conditions.

- RSI propagation exhibits a distinct duality: convective traveling waves on the pressure side versus modal standing waves on the suction side. The resulting spanwise phase mismatch induces asynchronous loading and hydrodynamic torsional moments on the blade. Consequently, monitoring strategies must be differentiated: pressure-side arrays are recommended for tracking wave propagation, while suction-side sensors should be prioritized for detecting low-frequency flow instabilities.

- Three primary stress concentration zones are identified in the pump-turbine runner: (a) the junction of the pressure side inlet and the crown; (b) the mid-span region of the pressure side adjacent to the crown; (c) the mid-span region of the suction side adjacent to the band. Under turbine operating conditions, zone (a) exhibits the most critical stress concentration, where priority should be given to structural reinforcement and monitoring in both design and maintenance phases.

- During turbine operation, low-load conditions result in fewer pulsation harmonic frequencies with concentrated distribution. In contrast, high-load conditions lead to more pulsation harmonic frequencies—these are mostly concentrated in the low-frequency region overall, except in the second stress concentration area, where harmonic frequencies are predominantly in the high-frequency region.

- Quantitative analysis confirms spatial heterogeneity in RSI dominance: the band region acts as a far-field response zone strictly governed by RSI (amplitude deviation 0.01), whereas the crown inlet exhibits nonlinear constrained responses (deviation 0.38). These findings advocate a design paradigm shift from passive strength verification to active flow phase control, specifically via stacking line optimization to synchronize spanwise pressure arrival and mitigate hydrodynamic torsion at the source.

Despite the rigorous quantitative characterization of RSI propagation and stress response, this study acknowledges certain limitations. The current investigation focuses on discrete stationary operating points (full load and 50% load); the continuous dynamic evolution during transient processes, such as load rejection or pump startup, remains to be explored. Crucially, regarding the numerical validity, it must be explicitly stated that while the one-way FSI approach is sufficient for the high-stiffness runner analyzed herein, a two-way FSI coupling strategy may be necessary near resonance, in runner geometries with significantly lower stiffness, or during strong transient conditions where hydroelastic feedback becomes critical. The proposed ‘active phase control’ strategy for optimizing blade stacking laws currently remains a conceptual qualitative discussion derived from the phase mechanism analysis, lacking direct quantitative verification through parametric geometric variations. Consequently, future work will aim to extend the proposed active phase control strategy to optimize blade stacking laws, thereby verifying its effectiveness across a broader range of transient operational scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. and X.H.; methodology, L.G. and X.H.; software, F.J. and L.G.; validation, F.J. and D.Z.; investigation, F.J., L.G., D.Z., X.H. and Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J., L.G., and X.H.; writing—review and editing, F.J., L.G., D.Z., X.H., Z.L., and M.L.; project administration, J.L.; supervision, Z.W. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the project: Fujian Yunxiao Pumped Storage Power Station Pump-Turbine Unit Steady-State and Transient Operation Fluid–Structure Interaction Dynamic Characteristics Analysis and Evaluation Service, China National Nuclear Power Co., Ltd., Zhangzhou Energy Co., Ltd.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Feng Jin, Dawei Zeng and Zebin Lai were employed by the company Fujian Yunxiao Pumped Stroge Co., Ltd., State Grid Corporation of China. Author Xingxing Huangwas employed by S.C.I. Energy, Future Energy Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from China National Nuclear Power Co., Ltd. and Zhangzhou Energy Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAES | Compressed air energy storage |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| DPF | Dominant Pulsation Frequency |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| MCI | Mesh convergence index |

| RSI | Rotor–Stator Interaction |

| T | Turbine Mode |

| Rotation Frequency |

References

- Rehman, S.; Al-Hadhrami, L.M.; Alam, M.M. Pumped Hydro Energy Storage System: A Technological Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 44, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Z.; Kun, Z.; Daoxin, L. Overall Review of Pumped-Hydro Energy Storage in China: Status Quo, Operation Mechanism and Policy Barriers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 17, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, X. Techno-Economic Comparison of Long Duration Energy Storage. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 8th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Shenyang, China, 29 November–2 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-González, F.; Sumper, A.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O.; Villafáfila-Robles, R. A Review of Energy Storage Technologies for Wind Power Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2154–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cong, T.N.; Yang, W.; Tan, C.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. Progress in Electrical Energy Storage System: A Critical Review. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2009, 19, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, B.; Syri, S. Electrical Energy Storage Systems: A Comparative Life Cycle Cost Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 569–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, G.; Ji, W.; Zhu, D.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, F.; Guo, W. Experimental Study of a Mesoscale Combustor-Powered Thermoelectric Generator. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobilo, M.; Salehi, S.; Nilsson, H. Lifetime Analysis of Hydro Turbines with Focus on Fatigue Damage in a Renewable Energy System—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 228, 116578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, H.; Qin, Y.; Wei, X.; Qin, D. Numerical Simulation of Hysteresis Characteristic in the Hump Region of a Pump-Turbine Model. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, K.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ye, C. Numerical Investigation of Multiscale Flow-Induced Vibration and Fatigue Life Prediction of a Large Francis Turbine. Energy 2025, 335, 138334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y. Pressure Fluctuations in the Vaneless Space of High-Head Pump-Turbines—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-Z.; Su, W.-T.; Li, X.-B.; Zhang, Y.-N. Dynamic Characteristics of Load Rejection Process in a Reversible Pump-Turbine. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1922–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; He, Q.; Huang, X.; Yang, M.; Bi, H.; Wang, Z. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Rotor–Stator Interaction in a Large Prototype Pump–Turbine in Turbine Mode. Energies 2022, 15, 5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, C. Compressible Large Eddy Simulation of a Francis Turbine During Speed-No-Load: Rotor Stator Interaction and Inception of a Vortical Flow. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2018, 140, 112601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutnik, J. Contribution to the Improved Understanding of the Dynamic Behaviour of Pump Turbines and Use Thereof in Th Edynamic Design. In Proceedings of the 22nd IAHR Symposium on Hydraulic Machinery and Systems, Stockholm, Sweden, 29 June–2 July 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Gong, R.; Wang, H.; Xiang, G.; Wei, X.; Liu, Z. Dynamic Analysis on Pressure Fluctuation in Vaneless Region of a Pump Turbine. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2015, 58, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasmatuchi, V.; Farhat, M.; Roth, S.; Botero, F.; Avellan, F. Experimental Evidence of Rotating Stall in a Pump-Turbine at Off-Design Conditions in Generating Mode. J. Fluids Eng. 2011, 133, 051104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Qin, D.; Wei, X. Pressure Fluctuation Propagation of a Pump Turbine at Pump Mode under Low Head Condition. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2014, 57, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, Z.; You, J.; Yang, J.; Qian, Z. Evolutions of Pressure Fluctuations and Runner Loads During Runaway Processes of a Pump-Turbine. J. Fluids Eng. 2017, 139, 091101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Shu, Z.; Liu, D.; Tong, S. Investigating Flow-Induced Vibration in Pump-Turbines Using a Multi-Scale Fluid-Structure Interaction Approach Considering Clearance Flow Effects. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 82, 104487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Liang, Q.; Xiao, R.; Tao, R. Mechanistic Insights into Fatigue Behavior of Pump-Turbine at Different Guide Vanes Opening: A Study of Dynamic Stress Response and Chaos Phenomena. Energy 2025, 320, 135229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, K.; Zorn, M.; Ségoufin, C.; André, F.; Kerner, J.; Riedelbauch, S. Dynamic Stress Prediction for a Pump-Turbine in Low-Load Conditions: Experimental Validation and Phenomenological Analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 162, 108428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Shi, W.; Tian, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Tan, L. Fatigue Life Assessment and Damage Investigation of Centrifugal Pump Runner. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 124, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Lowys, P.-Y.; Houdeline, J.; Guo, X.; Hong, P.; Laurant, Y. Pump-Turbine Rotor-Stator Interaction Induced Vibration: Problem Resolution and Experience. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 774, 012124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnalt, E.; Iliev, I.; Solemslie, B.W.; Dahlhaug, O.G. On the Rotor Stator Interaction Effects of Low Specific Speed Francis Turbines. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2019, 2019, 5375149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xiao, R.; Liu, W.; Wang, F. Analysis of S Characteristics and Pressure Pulsations in a Pump-Turbine With Misaligned Guide Vanes. J. Fluids Eng. 2013, 135, 511011–511016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagnoni, E.; Andolfatto, L.; Guillaume, R.; Leroy, P.; Avellan, F. Rotor-Stator Interaction in a Pump-Turbine Operating in Synchronous Condenser Mode. In Proceedings of the 29th IAHR Symposium on Hydraulic Machinery and Systems, Kyoto, Japan, 17–21 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.M.; Devinar, L.; Abbas, A. Influence of Labyrinth Clearance on the Hydrodynamic Performance of a High Head Francis Turbine. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1411, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza Umar, B.; Huang, X.; Wang, Z. Experimental Flow Performance Investigation of Francis Turbines from Model to Prototype. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Hu, K.; Li, C.; Qiu, L. Stress Characteristic Analysis of Pump-Turbine Head Cover Bolts during Load Rejection Based on Measurement and Simulation. Energies 2022, 15, 9496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.