Abstract

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder with progressive impairment in patients worldwide, featuring manifestations of both motor dysfunction and various/list-specific non-motor symptoms. Early diagnosis and personalized treatment thus remain the biggest challenges in managing the disease. Artificial intelligence (AI), especially machine learning techniques, has shown immense potential for countering such challenges during the past years. This short review aims to summarize recent innovations in applying Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) to Parkinson’s disease, explicitly directed toward developing diagnostic tools, the prediction of progression, and personalized treatment strategies. We discuss several ML and DL approaches, including supervised and unsupervised learning models that have been applied to classify symptoms and identify biomarkers. In addition, integrating clinical and imaging data into disease models continues to advance. This indicates the emerging role of DL in bypassing the limitations of standard methods. This review of the future of AI in Parkinson’s disease research outlines its possible directions for enhancing patient care and clinical outcomes.

1. Introduction

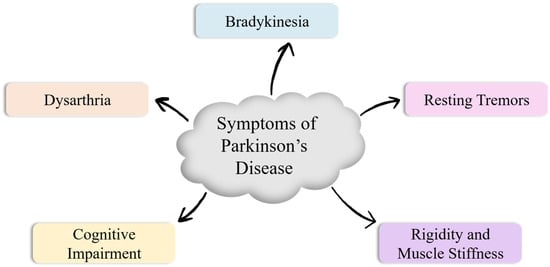

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common progressive (age-dependent) neurodegenerative condition that affects approximately 2–3% of people older than 65 years by affecting the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta [1]. This multisystemic disease is characterized by neuronal loss, which causes parkinsonism and non-motor symptoms, like hallucinations, hyposmia, dementia, and sleep disorders [2]. The loss of Dopamine in PD, along with low norepinephrine levels [3], causes multiple symptoms like bradykinesia (slow movements) [4], tremors [5], dysarthria (motor speech disorder) [6], rigidity [7], and cognitive impairments [8] in patients, as depicted in Figure 1. The clinical presentation varies substantially across individuals, and symptoms worsen gradually over time, although pharmacological and rehabilitative therapies can alleviate disease burden to some extent.

Figure 1.

Cardinal (primary) symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

PD is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder following Alzheimer’s, and its global prevalence has increased significantly in recent decades [9]. Its cases have doubled in 25 years, with 8.5 million people affected globally in 2019, causing significant disability and death [10].

It predominantly affects older individuals but can also impact younger people, with men at higher risk, and while its exact cause is unknown, factors like family history, age, and environmental toxins contribute to its development [10]. Certain lifestyle factors like traumatic brain injury, excessive dairy consumption, and unhealthy habits linked to cardiovascular disease and associated medical conditions, including type 2 diabetes, certain infections, and autoimmune disorders, can increase the risk of developing PD [11,12].

A significant loss (60–80%) of dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra occurs before PD symptoms appear [3,13]. Early detection helps clinicians in designing a neuroprotective disease-modifying therapeutic program, which can prevent or slow down its development and provide the patients (and their caregivers) with additional years of a higher quality of life [14]. Treatment in the initial stages can significantly improve quality of life, reduce socioeconomic impact, and extend life expectancy for patients, their families, and society [15].

PD diagnosis relies on clinical assessment of bradykinesia and presence of either resting tremor or rigidity, though tremor can be absent in up to 30% of confirmed cases [16]. Despite recent improvements in diagnostic criteria, accurately identifying PD can be difficult as symptoms often overlap with other neurological conditions, and there is currently no definitive test to confirm the diagnosis, especially in the early stages [17]. Clinical scales like the Hoehn and Yahr scale (1967), Unified PD Rating Scale (UPDRS) [18], and its modified version, Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified PD Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) [19], are also used for diagnosis.

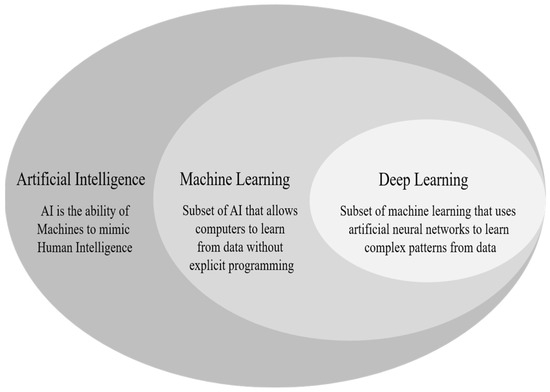

Deep learning (DL) is a subfield of Machine Learning (ML), as shown in Figure 2, which utilizes hierarchical artificial neural networks to unlock complex patterns within the data [20]. This capability makes it helpful in fields like natural language processing and computer vision. DL stands out from ML for its brain-like architecture and the ability to automatically extract patterns from data, unlike traditional methods that rely on human-defined features [21].

Figure 2.

AI as a broad field consisting of ML and DL.

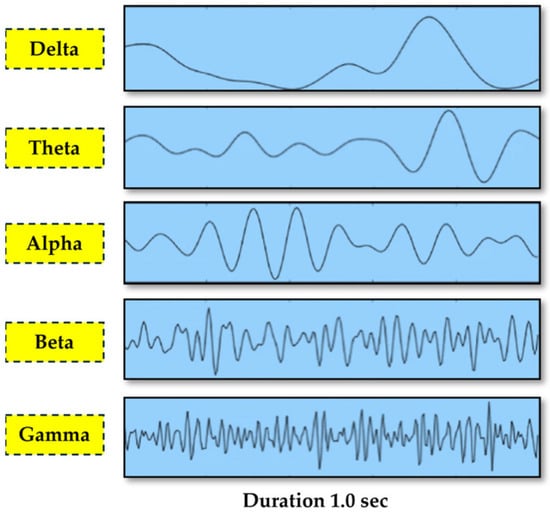

PD is associated with a slowing of brain activity (cortical activity), characterized by a shift from alpha to slower theta and delta brainwaves, even in early stages, along with a decrease in higher frequency activity [14]. Electroencephalography (EEG) signals effectively detect Parkinson’s disease despite their low amplitude, but their manual analysis is tedious and time-consuming. A visualization of different waves is presented in Figure 3 [22].

Figure 3.

EEG signal categorization by frequency sub-bands [22] [copyright permission is not required as per the journal policy: open access journal].

ML models have also been applied to various data modalities for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD), including handwritten patterns, movement, neuroimaging, voice, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), cardiac scintigraphy, serum, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) [23]. Hence, ML offers a wide range of techniques for PD diagnosis, including traditional methods like linear regression, logistic regression, decision trees, and support vector machines, as well as more advanced DL approaches such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [24]. The most popular class of DL is the Convolutional neural network (CNN), which focuses on image classification tasks [25].

These algorithms analyze diverse data types to identify patterns associated with the disease, thereby aiming to improve diagnostic accuracy and allow earlier detection.

Despite several recent reviews on AI applications in Parkinson’s disease, most prior work either focuses on a single data modality, provides broad conceptual summaries, or predates the surge of multimodal and deep learning approaches published between 2022 and 2025. The present review differs by offering an updated, modality-organized synthesis of the most recent ML and DL studies, spanning imaging, EEG, voice, gait, handwriting, emotion, and biomarker data. In addition to summarizing findings, this review provides cross-study comparisons, identifies recurring methodological limitations, and highlights trends such as multimodal fusion, explainable AI, and the growing use of large public datasets. By integrating evidence across diverse data sources and emphasizing diagnostic and predictive tasks, this review aims to provide a more comprehensive, clinically relevant perspective on current advances and remaining gaps in AI-based PD research.

Review Methodology

The review was conducted using a structured, narrative approach to identify recent ML and DL studies focused on the diagnosis of PD. A comprehensive literature search was performed across four major databases—PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore.

The search included combinations of the following keywords and Boolean operators:

- “Parkinson’s disease”;

- “Machine learning”;

- “Deep learning”;

- “Artificial intelligence”;

- “Parkinson’s diagnosis”;

- “Parkinson’s voice-based diagnosis”;

- “Parkinson’s handwriting”;

- “Parkinson’s biomarkers”;

- “Parkinson’s multimodal analysis”;

- “Parkinson’s early diagnosis”.

The studies were included if they met the following conditions:

- Published between 2020 and 2025;

- Focused on ML or DL models applied to PD diagnosis, classification, prediction, or symptom assessment;

- Reported original research (not reviews or editorials);

- Used human subject data across any modality (imaging, EEG, voice, gait, handwriting, biomarkers, or multimodal datasets);

- Published in English.

Studies were excluded if they met the following conditions:

- Were purely theoretical or did not evaluate a model on real data;

- Focused solely on treatment response or medication effects without diagnostic relevance;

- Did not involve ML/DL techniques;

- Were duplicate reports or incomplete abstracts.

The initial search yielded approximately 60 articles. After title and abstract screening, eligible full texts were reviewed and organized by modality (Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3, Section 2.4, Section 2.5, Section 2.6, Section 2.7 and Section 2.8). Reference lists were also screened for additional studies. Key information including data modality, feature extraction, ML/DL methods, dataset characteristics, objectives, and performance metrics was extracted into summary Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9. Comparative analysis and cross-modality synthesis were conducted to identify overarching trends, methodological limitations, and future research needs. Table 1 summarizes data collection methods, objectives, and limitations in PD research.

Table 1.

Overview of data collection methods, dataset issues, study objectives, and reported limitations in PD research.

Table 2.

Summary of classification and prediction techniques for Parkinson’s disease diagnosis using imaging data.

Table 3.

Summary of studies which use recent advances in ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis using EEG signals and brainwave analysis.

Table 4.

Summary of studies which use recent advances in ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis using voice, speech, and acoustic features.

Table 5.

Summary of studies which use recent advances in ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis through motion and gait analysis from wearable sensors or video data.

Table 6.

Summary of studies which use recent advances in ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis using handwriting, drawing, or sketch-based features.

Table 7.

Summary of studies which use recent advances in ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis based on emotional, behavioral, or environmental interaction data.

Table 8.

Summary of studies which use recent advances in ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis through fusion of multiple data modalities.

Table 9.

Summary of studies which use recent advances in ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis based on genomic, genetic, or biomarker data.

2. Literature Review

By leveraging ML techniques, we can identify relevant attributes that are not traditionally used in the medical diagnosis of PD, enabling the diagnosis of PD in its preclinical stages using alternative indicators.

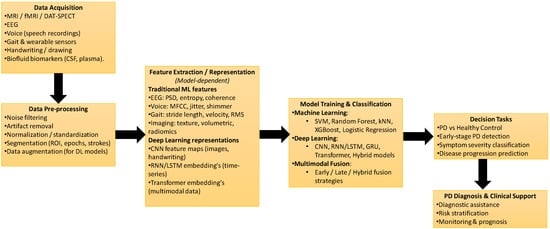

Generally, the diagnosis process involves three phases: data pre-processing, feature extraction, and the application of classification techniques [28], as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

General machine learning and deep learning workflow for Parkinson’s disease diagnosis using multimodal data.

Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3, Section 2.4, Section 2.5, Section 2.6, Section 2.7 and Section 2.8 present recent advancements in 2025 on the application of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models for the detection of Parkinson’s disease (PD).

2.1. Imaging-Based Approaches (MRI, fMRI, SPECT, Etc.)

MRI scans reveal significant structural and functional brain differences in individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD), particularly in the frontal and temporal lobes. These regions often show signs of cortical thinning, reduced gray matter volume, and disrupted connectivity, which are linked to the neurodegenerative processes responsible for both motor and cognitive symptoms in PD [72]. Moreover, the early-phase symptoms can be subtle and often overlap with other neurological conditions such as essential tremor, PSP, DLB, MSA, and SWEDD, making accurate diagnosis especially challenging even for experienced clinicians [29].

Imaging-based classification and prediction techniques for PD are summarized in Table 2.

2.2. EEG-Based Approaches

Electroencephalography (EEG) is increasingly used to investigate neural alterations in Parkinson’s disease (PD) due to its ability to capture real-time brain activity with high temporal resolution. While traditional EEG analyses focus on oscillatory power, connectivity patterns, or signal complexity, they often fall short in interpreting the transient neural dynamics essential for understanding PD-related functional disruptions [73]. Recent ML/DL-based EEG approaches for PD diagnosis are summarized in Table 3.

2.3. Voice and Speech-Based Analysis

Voice impairment, particularly dysphonia, is a common symptom in individuals with PD, with conditions like dysarthria and hypophonia affecting speech clarity and volume due to central nervous system damage [74]. Since nearly 90% of speech or voice data can aid in diagnosis, voice analysis has become a valuable tool for assessing disease progression, and AI is increasingly being integrated to support clinicians in interpreting these patterns and enhancing patient care.

Voice- and speech-based ML/DL approaches for PD diagnosis are summarized in Table 4.

2.4. Motion and Gait Analysis

Gait analysis is a powerful tool for quantifying movement deficits in PD, as gait abnormalities (along with bradykinesia, tremors, and posture issues) are core motor symptoms of the condition. Since early neuroimaging may not always reveal distinguishing signs, analyzing gait patterns provides valuable diagnostic insights, and with the aid of AI and machine learning, clinicians can better detect early-stage PD and monitor progression through subtle changes in mobility [75]. Motion- and gait-based ML/DL approaches for PD diagnosis are summarized in Table 5.

2.5. Handwriting and Drawing Analysis

Variations in handwriting, such as tremor frequency, amplitude, and direction, are valuable indicators in diagnosing Parkinson’s disease (PD), with writing tasks serving as clinical tools since the 19th century [55]. Quick handwriting assessments allow clinicians to observe fine motor disturbances and track tremor progression or treatment response through dynamic motion analysis. Table 6 summarizes studies applying recent ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis using handwriting, drawing, and sketch-based features.

2.6. Emotion and Behavioral Data

AI is increasingly being used to detect subtle emotional and behavioral changes in individuals with Parkinson’s disease, such as mood swings, anxiety, and apathy, which are all symptoms that often precede or accompany motor decline. By analyzing speech patterns, facial expressions, and behavioral data from wearable sensors, AI models can identify psychological fluctuations early, enabling timely intervention and personalized care for the patients. Table 7 summarizes studies applying recent ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis based on emotional, behavioral, and environmental data.

2.7. Multimodal and Fusion-Based Studies

Multimodal and fusion-based studies combine data from diverse sources such as neuroimaging, genetics, voice, gait, and wearable sensors to enhance early detection of prodromal PD. These integrative approaches leverage machine learning and deep learning models to extract complementary information, improving diagnostic accuracy beyond what single-modality systems can achieve [26]. Table 8 summarizes studies applying recent ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis through multimodal data fusion.

2.8. Genomic and Biological Markers

Genomic and biological markers, such as SNCA, LRRK2, and α-synuclein levels, play a crucial role in identifying individuals at risk for Parkinson’s disease (PD) before motor symptoms appear. Integrating these biomarkers with AI-driven models enables more precise risk prediction and early diagnosis by uncovering hidden patterns across large-scale omics datasets.

AI, particularly ML algorithms, can assist healthcare professionals in developing early diagnostic tools for patients with various neurodegenerative disorders. This is achieved by predicting long-term brain changes and measuring the effectiveness of treatments [27,76]. Thus, the integration of AI into clinical practice holds significant promise for improving patient outcomes through timely intervention and personalized treatment strategies. Table 9 summarizes studies applying recent ML/DL techniques for PD diagnosis based on genomic, genetic, and biomarker data.

3. Challenges and Future Directions

Although the application of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) in Parkinson’s disease (PD) research shows considerable promise, several key challenges must be addressed before these technologies can be effectively implemented in clinical practice.

3.1. Cross-Modal Comparative Discussion

Artificial intelligence (AI) methods have been applied across a wide range of data modalities in Parkinson’s disease (PD) research, each offering unique strengths along with inherent limitations. Understanding these cross-modal complementarities is essential for designing clinically meaningful diagnostic and predictive systems.

3.1.1. Imaging Modalities (MRI, fMRI, SPECT, DTI)

Imaging-based AI approaches benefit from rich structural and functional information, enabling the characterization of cortical thinning, altered connectivity networks, and dopaminergic deficits that are strongly associated with PD pathology [29,72]. Deep learning (DL) architectures, particularly CNNs and hybrid models, have achieved high diagnostic accuracy in identifying subtle anatomical changes. However, imaging data often require expensive scanners, standardized acquisition protocols, and highly trained personnel—factors that limit widespread clinical adoption. Additionally, imaging datasets are typically small, exhibit multicentre variability, and lack pathology-confirmed labels, resulting in limited model generalizability [24,29].

3.1.2. EEG-Based Methods

EEG offers excellent temporal resolution and is cost-effective compared to structural and functional imaging. AI models have successfully identified PD-related alterations in oscillatory power, connectivity, and time–frequency dynamics [35,36]. Nonetheless, EEG signals are highly susceptible to noise, inter-subject variability, and medication effects. The generalizability of EEG-based AI models decreases sharply when evaluated in cross-subject or cross-dataset settings, mainly due to inconsistent electrode settings and small sample sizes [35].

3.1.3. Voice and Speech Analysis

Voice-based AI systems leverage the fact that nearly 90% of PD patients exhibit dysphonia or speech impairment [74]. ML/DL models trained on MFCCs, jitter, shimmer, FrFT-based time–frequency features, and spectrogram representations show promising accuracy across various languages and recording conditions [39,40,41,42,43,44]. The primary limitations include dataset imbalance, overfitting to language-specific properties, and poor generalization across recording devices. Moreover, many publicly available datasets involve sustained vowel phonation, which may not always reflect real-world speech patterns [46].

3.1.4. Gait and Motion Analysis

Wearable sensors, accelerometers, and video-based pose estimation techniques offer unobtrusive and continuous monitoring of gait abnormalities—one of the hallmark symptoms of PD [49,75]. AI models have demonstrated strong performance in detecting freezing of gait (FoG), stride irregularities, and movement instability [51,52,53]. However, motion datasets are typically small and collected under controlled laboratory environments. Cross-dataset performance declines sharply due to variations in sensor placement, sampling frequencies, and movement protocols. Additionally, gait patterns may vary widely based on disease stage, comorbidities, and age.

3.1.5. Limitations in Handwriting and Drawing–Based Analysis

Handwriting analysis is particularly useful because tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and micrographia manifest clearly during writing tasks. DL models applied to spirals, meanders, and pressure-sensitive trajectories can discriminate PD from controls with high accuracy [55,56,57,58,59]. Still, handwriting datasets are limited in size and diversity, and most studies rely on static images rather than dynamic kinematic sequences. This reduces the capacity of models to capture real-time tremor fluctuations and movement smoothness.

3.1.6. Genomic, Proteomic, and Biomarker-Based Approaches

Molecular and biospecimen-based AI approaches have become increasingly important for detecting prodromal PD. Models trained on SNPs, CSF α-synuclein, tau, NfL, proteomics, or metabolomics data can reveal early biological signatures before motor symptoms appear [23,24,26,27].

The main challenges include population heterogeneity, batch effects, expensive assays, and missing modalities across cohorts. Biomarker datasets also tend to be small and require careful normalization and harmonization for reproducible AI models.

3.1.7. Synthesis Across Modalities

Across all modalities, a recurring theme emerges: single-source data provides valuable but incomplete information. Imaging captures structural changes, EEG reflects functional dynamics, speech captures articulatory deficits, and gait reveals motor control impairments. Biomarkers provide mechanistic insight.

AI systems that integrate these complementary signals show the highest potential for early-stage and prodromal PD detection, especially through multimodal fusion and hybrid ML–clinical frameworks [26,66].

3.2. Clinical Translation Challenges

Although AI demonstrates strong technical performance, several practical challenges hinder its integration into routine PD diagnosis and monitoring.

3.2.1. Regulatory Requirements

Clinical deployment of AI models must adhere to stringent regulatory frameworks, including standards for software as a medical device (SaMD), algorithm transparency, and post-marketing surveillance. Regulatory bodies increasingly require the following:

- ➢

- Explainability and interpretability,

- ➢

- Demonstration of algorithm robustness across populations,

- ➢

- Monitoring for performance drift in real-world settings.

These requirements pose challenges for deep learning models that operate as “black boxes”.

3.2.2. Dataset Harmonization and Standardization

Across PD research, data collection protocols vary widely by center, device, operator, and demographic characteristics. Differences in MRI scanner field strengths, EEG electrode configurations, voice recording environments, and bio specimen handling result in non-uniform datasets.

Without harmonization, AI models suffer from dataset shift and fail to generalize beyond their training domain. Multi-center, standardized acquisition pipelines are critical for ensuring reproducibility.

3.2.3. Model Interpretability

Clinical practitioners require transparent and interpretable AI decisions. While explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as SHAP, LIME, Grad-CAM, and feature attribution mapping are increasingly used, many PD models still provide limited insight into their internal reasoning.

Lack of interpretability reduces physician trust and slows regulatory approval.

3.2.4. Integration into Clinical Workflow

Even high-performing AI models may fail in practice if they are not aligned with existing clinical workflows. Challenges include the following:

- ➢

- Compatibility with EMR/EHR systems,

- ➢

- Time burden of data acquisition,

- ➢

- Need for technical support and training,

- ➢

- Model updates and maintenance,

- ➢

- Integration requires co-design with neurologists, movement disorder specialists, and hospital IT teams.

3.2.5. Cost and Infrastructure Limitations

Access to advanced imaging hardware, cloud-based storage, GPU-powered computation, and bio specimen testing varies widely across regions. These disparities are particularly evident in low- and middle-income countries. For real-world implementation, AI systems must be designed to operate efficiently on low-resource hardware or edge devices.

3.3. Limited Generalizability and Data Constraints

One of the primary concerns is the limited generalizability of current ML and DL models. Many studies are based on relatively small datasets that are often collected from single institutions or specific patient groups. This restricts the diversity and may not accurately reflect the broader PD population, especially those from minority or underrepresented groups. Such limitations can result in biased model performance and reduced accuracy when applied to real-world, diverse clinical settings. Expanding datasets to include multiple centers and varied demographic profiles is essential to develop more reliable and broadly applicable diagnostic tools [77,78,79].

3.4. Ethical and Legal Issues

The adoption of AI-based approaches in healthcare also raises important ethical and legal considerations. One critical issue is the potential for algorithmic bias, where models trained on unbalanced data could yield unfair or inconsistent outcomes across different patient populations. Additionally, concerns regarding patient privacy and data security are becoming increasingly significant, particularly when handling sensitive health information. Current regulatory and ethical guidelines are still evolving to address these complex challenges. Ensuring fairness, maintaining transparency, and protecting patient rights are fundamental to the responsible development and deployment of AI in clinical environments [80].

3.5. Obstacles to Clinical Adoption

Bringing AI models into routine clinical use faces practical barriers. There is currently no universal standard for how data should be collected, processed, or evaluated in this domain, which makes it difficult to compare results across studies and validate models consistently. Furthermore, many of the advanced models, especially those using deep learning, operate as “black boxes,” providing limited explanations for their decisions. This lack of interpretability can reduce confidence among healthcare professionals and hinder clinical integration. To overcome this, it is necessary to prioritize the development of models that are not only accurate but also explainable and clinically transparent. The translation of machine learning approaches into routine medical practice depends heavily on economic and infrastructural realities that differ widely across healthcare systems. Beyond algorithmic accuracy, the feasibility of deploying ML tools is shaped by the availability and cost of diagnostic equipment, the affordability of clinical services, and the presence of reliable digital infrastructure to support data processing and storage. In many low- and middle-income settings, limitations in imaging hardware, computational capacity, and standardized data acquisition pipelines pose significant barriers to adopting advanced ML-driven workflows. These practical concerns are consistent with broader discussions in the literature on the challenges of integrating AI technologies into real-world medicine, particularly the disparities in infrastructure, regulatory readiness, and resource availability across regions. At the same time, recent progress in portable imaging devices, cloud-based analytical systems, and cost-efficient diagnostic platforms suggests that ML applications may become increasingly accessible, even in resource-constrained environments. Acknowledging these factors provides a realistic outlook on the future applicability of ML in clinical practice and highlights the need for solutions designed to be scalable, affordable, and adaptable across varying healthcare ecosystems.

3.6. Future Directions

Based on the above synthesis, several high-priority research directions emerge for advancing AI-based PD diagnosis and monitoring.

3.6.1. Large-Scale, Multimodal Datasets with Harmonized Acquisition Standards

Future research should focus on building longitudinal, multi-center PD datasets that combine imaging, EEG, speech, gait, handwriting, genetic, and clinical data using unified protocols. This will reduce dataset shift and improve the robustness of machine learning models.

3.6.2. Explainable AI (XAI) to Enhance Clinician Trust

AI systems must provide interpretable explanations for their predictions. Examples include the following:

- ➢

- Saliency maps for imaging,

- ➢

- Frequency band contributions for EEG,

- ➢

- Formant and MFCC influence for speech models,

- ➢

- Gait cycle markers for motion analysis.

Developing modality-specific XAI frameworks will help clinicians understand and trust model outputs.

3.6.3. Multicenter External Validation and Benchmarking

Future studies must evaluate AI models across the following:

- ➢

- Different hospitals,

- ➢

- Populations,

- ➢

- Recording devices,

- ➢

- Geographical regions,

- ➢

- Disease stages.

Such external validation is a prerequisite for regulatory approval and clinical adoption.

3.6.4. Early-Stage and Prodromal PD Prediction Models

Most existing studies focus on differentiating established PD from healthy controls. A major future goal is to detect PD before motor symptoms appear, using the following:

- ➢

- REM sleep behavior disorder datasets,

- ➢

- Genetic risk profiles,

- ➢

- Autonomic dysfunction signals,

- ➢

- Subtle voice, gait, and handwriting biomarkers,

- ➢

- CSF and plasma signatures.

This early detection could dramatically improve neuroprotective treatment strategies.

3.6.5. Hybrid ML–Clinical Scoring Systems

Combining AI predictions with clinical scales such as MDS-UPDRS, MoCA, and H&Y staging can enhance diagnostic precision. Hybrid systems allow the following:

- ➢

- Clinician oversight,

- ➢

- Improved interpretability,

- ➢

- Better patient stratification.

3.6.6. Integration with Wearable and Home-Monitoring Technologies

Wearables, smartphones, and IoT devices allow continuous monitoring of gait, tremor, sleep, and voice. AI-enabled home-monitoring systems can perform the following:

- ➢

- Detect early deterioration,

- ➢

- Personalize treatment,

- ➢

- Reduce hospital visits,

- ➢

- Support telemedicine applications.

3.6.7. Generative AI for Data Augmentation and Missing-Modality Compensation

Generative models (GANs, diffusion models, variational autoencoders) can be used to carry out the following:

- ➢

- Augment small datasets,

- ➢

- Simulate rare gait or handwriting patterns,

- ➢

- Reconstruct missing imaging or bio specimen modalities,

- ➢

- Harmonize datasets across acquisition settings.

GAN-based augmentation has shown promise in reducing class imbalance and improving generalization in multiple PD modalities.

By addressing these pressing challenges, the field can move toward more effective, equitable, and clinically accepted AI solutions for Parkinson’s disease management.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the application of artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning and deep learning, represents a promising advancement in the early diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease. By aiding in the development of predictive tools and personalized treatment strategies, AI holds the potential to transform current clinical practices, offering more precise and effective options for patients. However, realizing this potential in a clinical setting requires addressing significant challenges, such as standardizing data, resolving ethical concerns, and creating uniform protocols. As these issues are tackled, AI is likely to play an increasingly vital role in enhancing patient care, ultimately improving outcomes for those affected by Parkinson’s disease.

Future research should prioritize expanding datasets with diverse patient populations to improve model generalizability and conducting longitudinal studies that track PD progression biomarkers. Advanced explainable AI (XAI) techniques, tailored for multimodal imaging analysis, can also help clarify model decision-making. Additionally, incorporating further data, such as genetic and clinical assessments, may enhance the accuracy and interpretability of early PD detection, ultimately bringing AI closer to practical, impactful clinical applications in PD care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., A.A., M.K.W.K. and V.G.; methodology, A.A. and V.G.; software, A.S., A.A., V.G. and V.S.; validation, V.G. and V.S.; formal analysis, A.S. and V.S.; investigation, A.S., A.A. and M.K.W.K.; resources, A.S. and V.S.; data curation, V.G. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., A.A., M.K.W.K., V.G., and V.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S., A.A., M.K.W.K., V.G. and V.S.; visualization, V.G. and V.S.; supervision, A.A. and V.G.; project administration, A.A., M.K.W.K., V.G. and V.S.; funding acquisition, A.A. and M.K.W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Johannesburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data and results are presented within this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Polverino, P.; Cocco, A.; Albanese, A. Post-COVID parkinsonism: A scoping review. Park. Relat. Disord. 2024, 123, 106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, A.; Cochen De Cock, V.; Fantini, M.L.; Pérez-Carbonell, L.; Trotti, L.M. Sleep and sleep disorders in people with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kispotta, S.; Das, D.; Prusty, S.K. A recent update on drugs and alternative approaches for parkinsonism. Neuropeptides 2024, 104, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graaf, D.; Araújo, R.; Derksen, M.; Zwinderman, K.; de Vries, N.M.; IntHout, J.; Bloem, B.R. The sound of Parkinson’s disease: A model of audible bradykinesia. Park. Relat. Disord. 2024, 120, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hathaliya, J.J.; Modi, H.; Gupta, R.; Tanwar, S.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, R. Parkinson and essential tremor classification to identify the patient’s risk based on tremor severity. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 101, 107946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, B.; Sahu, S.S.; Orozco-Arroyave, J.R. An investigation about the relationship between dysarthria level of speech and the neurological state of Parkinson’s patients. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 42, 710–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn-Evans, M.E.; Petrucci, M.N.; Huffmaster, S.L.A.; Chung, J.W.; Tuite, P.J.; Howell, M.J.; MacKinnon, C.D. REM sleep without atonia is associated with increased rigidity in patients with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 2008–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, B.E.; Twedt, H.P.; Bruss, J.; Schultz, J.; Narayanan, N.S. Cortical and subcortical functional connectivity and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2024, 42, 103610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmed, Z.; Zhu, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; Su, D.; Zhao, D.; Feng, T. Temporal trends in the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease from 1980 to 2023: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, e464–e479. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Parkinson Disease. Available online: www.who.int (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Grotewold, N.; Albin, R.L. Update: Protective and risk factors for Parkinson disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2024, 125, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, D.; Iyer, M.; Wilson, R.; Vellingiri, B. The association between multiple risk factors, clinical correlations and molecular insights in Parkinson’s disease patients from Tamil Nadu population, India. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 755, 135903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, M. Deep learning for Parkinson’s disease diagnosis: A short survey. Computers 2023, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Aparisi, G.; Guijarro-Estelles, E.; Chornet-Lurbe, A.; Ballesta-Martinez, S.; Pardo-Hernandez, M.; Ye-Lin, Y. Early detection of Parkinson’s disease: Systematic analysis of the influence of the eyes on quantitative biomarkers in resting state electroencephalography. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fezeu, F.; Jbara, O.F.; Jbarah, A.; Choucha, A.; De Maria, L.; Ciaglia, E.; Samnick, S. PET imaging for a very early detection of rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder and Parkinson’s disease—A model-based cost-effectiveness analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2024, 243, 108404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylecki, C. Update on the diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Med. 2020, 20, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, S.; Scholz, W.; Tolosa, E.; Garrido, A.; Scholz, S.W.; Poewe, W. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahuja, G.; Nagabhushan, T.N. A comparative study of existing machine learning approaches for Parkinson’s disease detection. IETE J. Res. 2021, 67, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, N.; Macleod, A.D.; Alves, G.; Camacho, M.; Forsgren, L.; Lawson, R.A.; Khoo, T.K. Validation of a UPDRS-/MDS-UPDRS-based definition of functional dependency for Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 76, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananth, K.R.; Khan, S.F.; Agarwal, A.; Bhatt, M.W.; Alvi, A.M.; Degadwala, S. IoT and Developed Deep Learning-Based Road Accident Detection System and Societal Knowledge Management. In Next Generation Computing and Information Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debus, B.; Parastar, H.; Harrington, P.; Kirsanov, D. Deep learning in analytical chemistry. Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 148, 116459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delis, A.; Tsavdaridis, G.; Tsanakas, P. A Novel Battery-Supplied AFE EEG Circuit Capable of Muscle Movement Artifact Suppression. Processes 2024, 14, 6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaranjini, S.; Sujatha, C.M. Deep learning-based diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease using convolutional neural network. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2020, 79, 15467–15479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.G.P.; Strafella, A.P. The role of AI and machine learning in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonisms. Park. Relat. Disord. 2024, 128, 107118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Park, C. A deep learning paradigm for medical imaging data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 55, 124052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serag, I.; Azzam, A.Y.; Hassan, A.K.; Diab, R.A.; Diab, M.; Hefnawy, M.T.; Ali, M.A.; Negida, A. Multimodal Diagnostic Tools and Advanced Data Models for Detection of Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease: A Scoping Review. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, A.; Peña-Castillo, L.; Usefi, H. Assessing the Reproducibility of Machine-Learning-Based Biomarker Discovery in Parkinson’s Disease. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 174, 108407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Dumka, A.; Singh, R.; Panda, M.K.; Priyadarshi, N.; Twala, B. Imperative role of machine learning algorithm for detection of Parkinson’s disease: Review, challenges and recommendations. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.; Saini, B.S.; Gupta, S. Role of artificial intelligence techniques and neuroimaging modalities in detection of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Cogn. Comput. 2023, 16, 2078–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, H.; Höglinger, G.U.; Grön, G.; Bârlescu, L.A.; DESCRIBE-PSP Study Group; Müller, H.P.; Kassubek, J. MRI classification of progressive supranuclear palsy, Parkinson disease and controls using deep learning and machine learning algorithms for the identification of regions and tracts of interest as potential biomarkers. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 185, 109518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Turza, M.S.A.; Fahim, S.I.; Rahman, R.M. Advanced Parkinson’s disease detection: A comprehensive artificial intelligence approach utilizing clinical assessment and neuroimaging samples. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2024, 5, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; He, Y. Adoption of deep learning-based magnetic resonance image information diagnosis in brain function network analysis of Parkinson’s disease patients with end-of-dose wearing-off. J. Neurosci. Methods 2024, 409, 110184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maged, A.; Zhu, M.; Gao, W.; Hosny, M. Lightweight deep learning model for automated STN localization using MER in Parkinson’s disease. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 96, 106640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahuja, G.; Prasad, B. Deep learning architectures for Parkinson’s disease detection by using multi-modal features. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Geem, Z.W.; Cho, Y.I.; Singh, P.K. A comparative study of machine learning and deep learning models for automatic Parkinson’s disease detection from electroencephalogram signals. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Jia, J.; Zhang, R. EEG analysis of Parkinson’s disease using time–frequency analysis and deep learning. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 78, 103883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezazi, Y.; Ghaderyan, P. Textural feature of EEG signals as a new biomarker of reward processing in Parkinson’s disease detection. J. Appl. Biomed. 2022, 42, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Huang, D.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Olmo, G.; Chan, P. High-accuracy wearable detection of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease based on pseudo-multimodal features. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Srivastav, S.; Shaffer, J.G.; Abraham, K.E.; Naandam, S.M.; Kakraba, S. Optimizing Parkinson’s disease prediction: A comparative analysis of data aggregation methods using multiple voice recordings via an automated artificial intelligence pipeline. Data 2025, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Tarique, M. Escalate Prognosis of Parkinson’s Disease Employing Wavelet Features and Artificial Intelligence from Vowel Phonation. BioMedInformatics 2025, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, H.; Al-Rousan, N.; Al-Najjar, D. Hybrid Grey Wolf and Whale Optimization for Enhanced Parkinson’s Prediction Based on Machine Learning Models Using Biomedical Sound. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2024, 48, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Tripathi, P. An Ensemble Technique to Predict Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Speech Commun. 2024, 159, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lin, L.; Xue, Z. A Voice Feature Extraction Method Based on Fractional Attribute Topology for Parkinson’s Disease Detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 219, 119650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guatelli, R.; Aubin, V.; Mora, M.; Naranjo-Torres, J.; Mora-Olivari, A. Detection of Parkinson’s Disease Based on Spectrograms of Voice Recordings and Extreme Learning Machine Random Weight Neural Networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 125, 106700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hireš, M.; Drotár, P.; Pah, N.D.; Ngo, Q.C.; Kumar, D.K. On the Inter-Dataset Generalization of Machine Learning Approaches to Parkinson’s Disease Detection from Voice. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 179, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibińska, J.; Hosek, J. Computerized Analysis of Hypomimia and Hypokinetic Dysarthria for Improved Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawi, S.; Alhozami, J.; AlQahtani, R.; AlSafran, D.; Alqarni, M.; Sahmarany, L.E. Automatic Parkinson’s Disease Detection Based on the Combination of Long-Term Acoustic Features and Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC). Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2022, 78, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hireš, M.; Gazda, M.; Drotár, P.; Pah, N.D.; Motin, M.A.; Kumar, D.K. Convolutional Neural Network Ensemble for Parkinson’s Disease Detection from Voice Recordings. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 141, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Chang, R.; Wang, J.; Narayanan, A.; Qian, P.; Leong, M.C.; Kundu, P.P.; Senthilkumar, S.; Garlapati, S.C.; Yong, E.C.K.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced 3D Gait Analysis with a Single Consumer-Grade Camera. J. Biomech. 2025, 187, 112738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Fernández, L.P.; Sánchez Pérez, L.A.; Martínez Hernández, J.M. Computer Model for Gait Assessments in Parkinson’s Patients Using a Fuzzy Inference Model and Inertial Sensors. Artif. Intell. Med. 2025, 160, 103059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigcha, L.; Borzì, L.; Olmo, G. Deep Learning Algorithms for Detecting Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease: A Cross-Dataset Study. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Williams, S.; Hogg, D.C.; Alty, J.E.; Relton, S.D. Deep Learning of Parkinson’s Movement from Video, without Human-Defined Measures. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 463, 123089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzì, L.; Sigcha, L.; Rodríguez-Martín, D.; Olmo, G. Real-Time Detection of Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease Using Multi-Head Convolutional Neural Networks and a Single Inertial Sensor. Artif. Intell. Med. 2023, 135, 102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, N.; Veer, K.; Pahuja, S. Gender-Based Assessment of Gait Rhythms during Dual-Task in Parkinson’s Disease and Its Early Detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 72, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yu, H.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. A New Network Structure for Parkinson’s Handwriting Image Recognition. Med. Eng. Phys. 2025, 139, 104333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastry, K.A. Deep Learning-Based Diagnostic Model for Parkinson’s Disease Using Handwritten Spiral and Wave Images. Curr. Med. Sci. 2025, 45, 206–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Xie, X.; Peng, P.; Chen, T.; Zhao, Z.; Wen, Y.; Hong, W. A Novel Approach for Handwriting Recognition in Parkinson’s Disease by Combining Flexible Sensing with Deep Learning Technologies. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 385, 116287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragadeeswaran, S.; Kannimuthu, S. Cosine Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Parkinson’s Disease Detection and Severity Level Classification Using Hand Drawing Spiral Image in IoT Platform. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 94, 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varalakshmi, P.; Priya, B.T.; Rithiga, B.A.; Bhuvaneaswari, R.; Sundar, R.S.J. Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease from Hand Drawing Utilizing Hybrid Models. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 105, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deharab, E.D.; Ghaderyan, P. Graphical Representation and Variability Quantification of Handwriting Signals: New Tools for Parkinson’s Disease Detection. J. Appl. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 42, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepa, L.; Spalazzi, L.; Ceravolo, M.G.; Capecci, M. Supervised Learning for Automatic Emotion Recognition in Parkinson’s Disease through Smartwatch Signals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.R.; Santos, C.P. Deep Learning Model for Doors Detection: A Contribution for Context-Awareness Recognition of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 212, 118712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.C.; Ngo, Q.C.; Passos, L.A.; Papa, J.P.; Jodas, D.S.; Kumar, D. Tabular Data Augmentation for Video-Based Detection of Hypomimia in Parkinson’s Disease. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 240, 107713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayvat, H.; Awais, M.; Geddam, R.; Quasim, M.T.; Khowaja, S.A.; Dev, K. AiCareGaitRehabilitation: Multi-Modalities Sensor Data Fusion for AI IoT Enabled Real-Time Electrical Stimulation Device for Pre-Fog and Post-Fog in Parkinson’s Disease. Inf. Fusion 2025, 122, 103155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsavai, D.; Iyer, A.; Nair, A.A. A Quantum Inspired Machine Learning Approach for Multimodal Parkinson’s Disease Screening. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Huo, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, S. Multi-Modal Biological Feature Selection for Parkinson’s Disease Staging Based on Binary PSO with Broad Learning. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 94, 106234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Fan, L.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Jiang, W.; Ma, X. Leveraging Multimodal Deep Learning Framework and a Comprehensive Audio-Visual Dataset to Advance Parkinson’s Detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 95, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, R.T.J.; Tsurkalenko, O.; Klucken, J.; Mangone, G.; Khoury, F.; Vidailhet, M.; Zelimkhanov, G. Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesia in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights from Cross-Cohort Prognostic Analysis Using Machine Learning. Park. Relat. Disord. 2024, 126, 107054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, T.R.; Bhardwaj, R.; Khan, S.B.; Alkhaldi, N.A.; Victor, N.; Verma, A. An Artificial Intelligence-Based Decision Support System for Early and Accurate Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 10, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Ali, S.; Eid, F.; El-Sappagh, S.; Abuhmed, T. Explainable Machine Learning Models Based on Multimodal Time-Series Data for the Early Detection of Parkinson’s Disease. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 234, 107495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shastry, K.A. An Ensemble Nearest Neighbor Boosting Technique for Prediction of Parkinson’s Disease. Healthc. Anal. 2023, 3, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Giri, D.; Patel, R. Artificial intelligence diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease from MRI scans. Cureus 2024, 16, e58841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyfantakis, G.; Manouvelou, S.; Koutoulidis, V.; Velonakis, G.; Scarmeas, N.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Can progressive supranuclear palsy be accurately identified via MRI with the use of visual rating scales and signs? Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakry, S.A.; Mahmoud, N.M. Automated early prediction of Parkinson’s disease based on artificial intelligent techniques. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhwani, P.L.; Harjpal, P. A Review of Artificial Intelligence-Based Gait Evaluation and Rehabilitation in Parkinson’s Disease. Cureus 2023, 15, e47118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, I.; Sone, D.; Yao, Z.; Maikusa, N. Editorial: State-of-the-Art Artificial Intelligence Methods in Neurodegeneration. Front. Neurol. 2023, 13, 1112639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, S.; Minssen, T.; Cohen, G. Ethical and Legal Challenges of Artificial Intelligence-Driven Healthcare. In Elsevier eBooks; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termine, A.; Fabrizio, C.; Strafella, C.; Caputo, V.; Petrosini, L.; Caltagirone, C.; Cascella, R. Multi-Layer Picture of Neurodegenerative Diseases: Lessons from the Use of Big Data through Artificial Intelligence. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbas, H.A.; Aladwan, I.M.; Agarwal, A.; Ilunga, M.; Badran, O.; Ikhries, I.I. Comparative investigation of mechanical characteristics and microstructure in maraging steel fabricated via DMLS and CNC techniques. Int. J. Comput. Methods Exp. Meas. 2025, 13, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Rana, A.; Singh, R.; Dumka, A.; Priyadarshi, N.; Twala, B. Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Parkinson’s Disease: Recent Advancements, Ethical Concerns, and Future Directions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 158, 105568. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.